Metal Additive Manufacturing: Processes, Applications in Aerospace, and Anticipated Hurdles - A Comprehensive Review

A.K. Madan1, Parth Singh2, Aman Mishra2, Naman Tanwar21Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Delhi Technological University, India

2 Student, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Delhi Technological University, India ***

Abstract - Additive manufacturing has emerged as a game-changing technology in the manufacturing industry, particularly in the aerospace sector. Metal additive manufacturing, in particular, has garnered considerable attention due to its unique ability to produce complex geometries with high precision and accuracy. This review paperfocusestoprovideacomprehensiveoverviewofthe common metal additive manufacturing processes, their applicationsin theaerospaceindustry, and the challenges that lie ahead. The study begins with a brief introduction to metal additive manufacturing, followed by a detailed analysis of the most commonly used processes, such as laser bed melting, powder bed fusion, directed energy deposition,andbinderjetting.Next,thepaperexploresthe various aerospace applications of metal additive manufacturing, including engine components, structural parts, and tooling. Finally, the review concludes by discussingthecurrentlimitationsandfuturechallengesof metal additive manufacturing, such as the need for improved material properties, cost reduction, and standardisation. Overall, this paper provides valuable insights for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers interestedinthepotentialofmetaladditivemanufacturing inaerospaceandbeyond.

Key Words: Additive Manufacturing, Ti-6Al-4V, EBM, LBM,PostProcessing,Aerospace,Microstructure,etc.

1.INTRODUCTION

Additive manufacturing methods: -

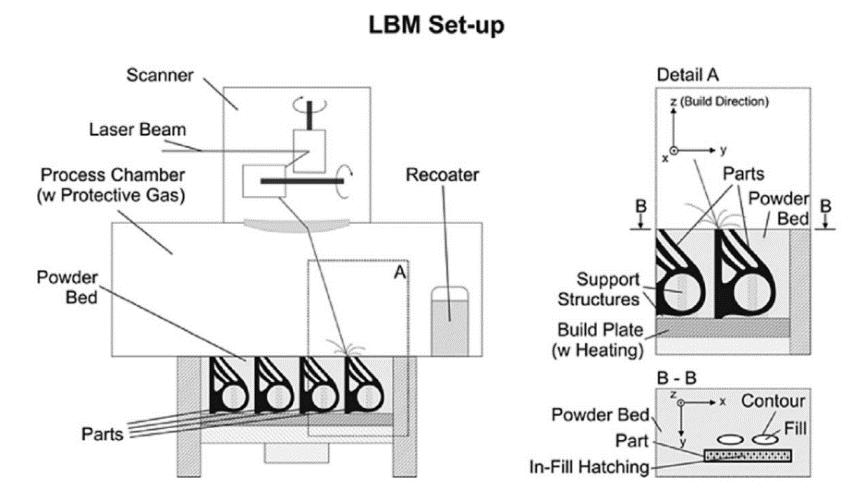

1.1. Laser beam melting (LBM)-

Metal laser beam melting (LBM) is a widely used additive manufacturingtechniquethatemploysahigh-powerlaser to selectively melt metal powder layers to create threedimensional (3D) components. The process typically involves the deposition of metal powder in thin layers onto a build platform, followed by the melting of the powder layer using a laser beam. The melted metal solidifies rapidly upon cooling to form a solid layer. The buildplatformis thenloweredto allowforthedeposition of the next layer of powder, which is selectively melted usingthelaser.Thislayer-by-layerprocesscontinuesuntil the3Dcomponentiscomplete.

One of the main advantages of metal LBM is its ability to produce complex geometries that are difficult or impossible to achieve with traditional manufacturing techniques. This process enables the creation of intricate designs with internal structures, such as lattices and honeycombs, that can improve the mechanical properties ofthefinalcomponent.Furthermore,metalLBMallowsfor the fabrication of custom components with minimal material waste, which makes it a more cost-effective and sustainable manufacturing process compared to traditionalmethods.However,metalLBMdoeshavesome limitations, such as the need for post-processing to achieve the desired surface finish and the relatively slow buildtimeforlargercomponents.Additionally,thequality of the final product can be affected by factors such as powder quality, laser power, and process parameters, which require careful monitoring and optimization to ensureconsistentandhigh-qualityparts.

In summary, metal LBM is a powerful additive manufacturing technique that enables the production of complex geometries with improved mechanical properties. The ability to make custom components along with minimal waste makes it an attractive option for various industrial applications. Despite its limitations, metal LBM continues to be an area of active research and development,withongoingeffortstoimprovetheprocess efficiency,scalability,andreliabilitytoexpanditspotential applications in various fields, including the aerospace, medical,andautomotiveindustries.

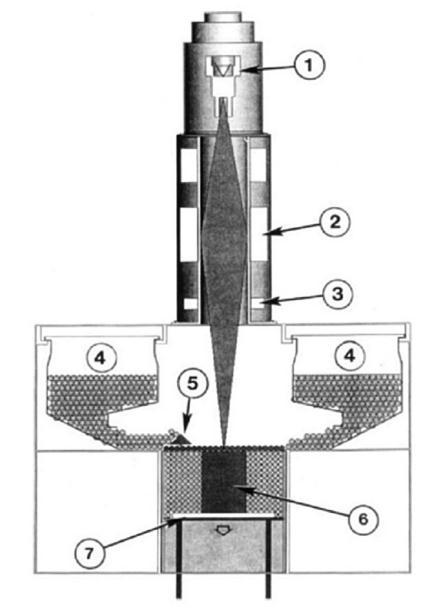

1.2 Electron beam melting (EBM)

Additive manufacturing of metal has revolutionised the manner in which we create and manufacture intricate metal parts. One of the metal additive manufacturing techniques gaining attention in recent years is electron beam melting (EBM). EBM is a powder bed fusion technology that employs an electron beam as the heat source to selectively melt metal powder. It operates in a vacuumtoavoidinterferencewiththeelectronbeam,and the melting process is precisely controlled by manipulatingtheelectronbeam'sspeed,power,andfocus.

One of the unique benefits of EBM technology is the potential to manufacture parts with high accuracy and excellent mechanical properties. The process can produce parts with a density close to theoretical density, thereby reducing the need for post-processing. Additionally, EBM allows the production of parts with intricate geometries, including internal features and overhangs,thataredifficultorimpossibletoachieveusing conventional machining techniques. As a result, EBM is used in a wide range of applications, including aerospace, biomedical, and automotive industries, where the components' high complexity and excellent mechanical propertiesarecrucial.

electronbeamastheheatsourcetoselectivelymeltmetal powder.

It operates in a vacuum to avoid interference with the electron beam, and the melting process is precisely controlled by manipulating the electron beam's speed, power,andfocus.

One unique benefit of EBM technology is the potential to manufacture parts with high accuracy and excellent mechanical properties. The process is capable of producing parts with a density close to the theoretical density, thereby reducing the need for post-processing. Additionally, EBM allows for the manufacturing of parts with intricate geometries, including internal features and overhangsthataredifficultorimpossibletoachieveusing conventional machining techniques. As a result, EBM is used in a wide range of applications, including aerospace, and automotive industries, biomedical where the components' high complexity and excellent mechanical propertiesarecrucial.

Fig2:EBMmachineschematic

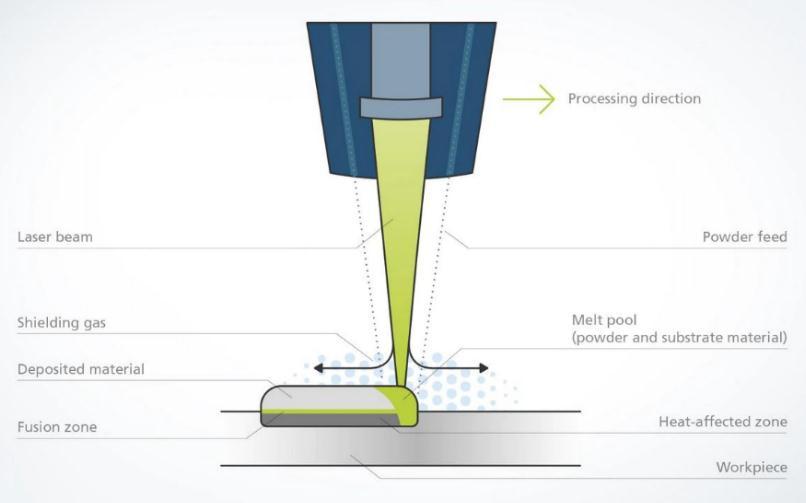

1.3 Laser metal deposition (LMD)

Metaladditivemanufacturinghastransformedthewaywe designandfabricatecomplexmetallic components.Oneof the metal additive manufacturing techniques gaining attention in recent years is electron beam melting (EBM). EBM is a powder bed fusion technology that employs an

2. Feedstock for AM

2.1 Powder Production

Additive manufacturing (AM) is an advanced technique that involves the layer-by-layer addition of materials to produce three-dimensional objects. Metal powders are the most commonly used feedstock material in AM processes. The properties of the powder material determine the quality of the final AM part. Therefore, it is essential to use high-quality powders for AM to achieve optimalresults.

Spheroidization and atomization are two commonly used techniques for powder production. Spheroidization involves melting and solidifying a metal in a manner that produces spherical particles of uniform size and shape. This process can be achieved through various methods, including induction plasma spheroidization, which

involves melting and atomizing metal using inductively coupledplasma.Theresultingpowderparticleshavegood flowability and apparent density, making them ideal for AM.

Atomization is another widely used technique for producing metal powders. This process involves the production of small droplets of molten metal, which are rapidly cooled and solidified to form powder particles. Water, gas, or plasma are commonly used as atomization media. Gasatomization ispreferred for reactive materials like titanium, where oxidation can be a problem. Gas atomizationisachievedbyusinganinertgaslikeargonor nitrogentopreventoxidationduringpowderproduction.

Feedstock refers to the raw materials used to produce parts using additive manufacturing (AM) processes. For metals, feedstock typically comes in the form of metal powders, which are used as the starting material to build upthedesiredpartlayerbylayer.InAM,thequalityofthe feedstock material plays a crucial role in the final product'squality,strength,anddurability.

2.2 Steel

Steel is a widely used material in AM due to its excellent mechanical properties, durability, and affordability. Different types of steel alloys are used in AM, each with distinctcharacteristicsandapplications.

One popular type of steel used in AM is stainless steel, whichisknownforitscorrosionresistance,highstrength, and durability. Austenitic stainless steels, such as 304L and 316L, are commonly used in AM applications that require high corrosion resistance and good ductility. Anothercommonlyusedsteel inAMistoolsteel,which is used for applications that require high wear resistance, toughness,andhardness.Toolsteels,suchasH13andD2, are typically used in the production of moulds, dies, and tooling components. Low carbon steels are also used in AM applications that require high strength and good ductility. Low carbon steels, such as AISI 1020, are commonly used in the production of structural components,automotiveparts,andconsumerproducts.

2.3 Aluminium Alloys

One crucial factor that determines the quality and propertiesofAMpartsisthechoiceoffeedstock material. In the case of aluminium alloys, the feedstock material must have certain characteristics, including excellent flowability,highsphericity,andlowoxygencontent.

Aluminiumalloysarewidelyusedinvariousindustries duetotheirdesirablepropertiessuchashighstrength-toweight ratio, good corrosion resistance, and excellent thermal conductivity. The choice of aluminium alloy feedstock material for AM processes depends on several

factors, including the intended application, the required mechanical properties, and the processing method. Some of the commonly used aluminium alloys for AM include AlSi10Mg,AlSi12,andAl7075.

TheAlSi10MgalloyisapopularchoiceforAMapplications duetoitsgoodmechanicalproperties,suchashigh tensile strength and good ductility. It is also easy to process and has good corrosion resistance. The AlSi12 alloy, on the other hand, is known for its high thermal conductivity, making it suitable for applications that require good heat dissipation. Al7075, which is a high-strength aluminium alloy, is preferred for applications that require excellent fatiguepropertiesandhighstrength.

2.4 Titanium and its Alloys

Inthecaseoftitaniumanditsalloys,titaniumpowdersare commonly used as feedstock due to their desirable mechanical properties, such as a high strength-to-weight ratio,excellentcorrosionresistance,andbiocompatibility.

Titanium powders for AM can be produced using various methods, including gas atomization, plasma atomization, andinductionplasmaspheroidization. Gasatomization, in particular, is a preferred method for producing highquality titanium powders with low oxygen content, which is essential for achieving optimum mechanical properties in the final product. Argon or nitrogen gas is used to preventoxidationduringatomization.

Anothercritical factorinselecting feedstock for AMis the particle size distribution, which influences the microstructure and mechanical properties of the final product. The ideal particle size for titanium powder is in the range of 10-45 micrometres, with a spherical shape, highflowability,anddensity.Thisisbecausethepowder's flowabilityandpackingdensityaffectthebuildqualityand mechanicalstrengthoftheprintedparts.

3. Microstructure of Additively Manufactured Parts

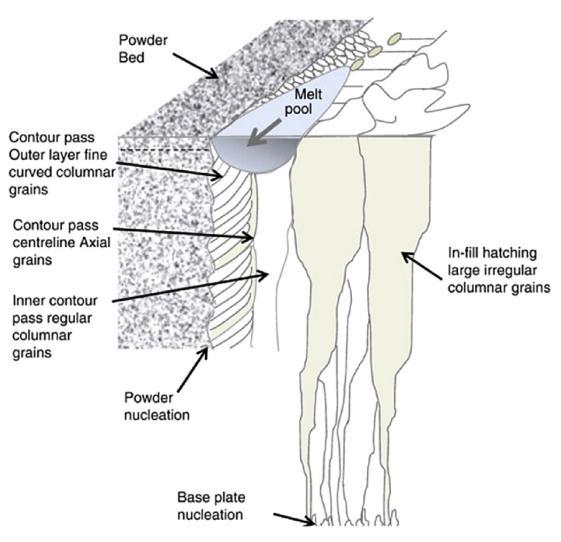

In additive manufacturing, the material undergoes a complex thermal cycle that includes rapid heating above the melting temperature, followed by solidification after the heat source has moved on. This process involves numerous re-heating and re-cooling stages when subsequent layers are deposited, resulting in nonequilibriumcompositionsandmetastablemicrostructures of the resulting phases. Consequently, additive manufacturing fabricated parts exhibit complex microstructuresandcomposition.

3.1 LBM of Pure Ti

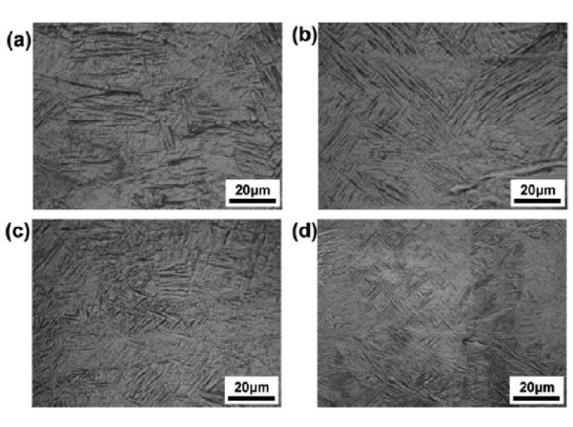

The LBM process involves the selective melting and solidification of successive layers of titanium powder

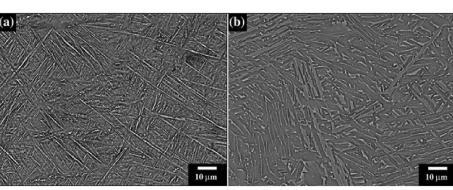

using a high-powered laser. The resulting microstructure is highly dependent on various factors, such as laser power, scanning speed, layer thickness, and powder size distribution. Microstructural analysis of pure titanium produced through LBM has revealed a complex, multiscale structure characterised by a fine cellular dendritic structurewithultrafineβ-grainregions.

Furthermore, the microstructure of pure titanium producedthroughLBMishighlydependentonthecooling rate during solidification. Rapid cooling rates lead to the formation of a finer microstructure, while slower coolingratesresultinacoarsermicrostructurewithlarger β-grains. Understanding the microstructure of pure titanium producedthrough LBMiscritical tooptimisethe processing parameters and improving the mechanical propertiesofthefinalproduct.

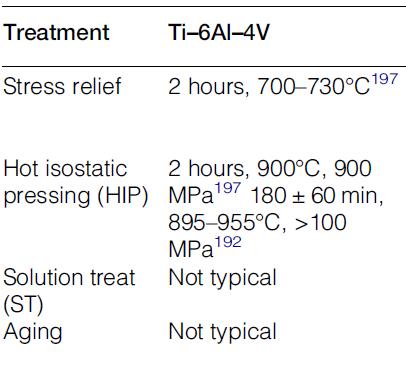

microstructure of Ti-6Al-4V produced through LBM. Thin layers can result in a more homogenous and refinedmicrostructure,whilethickerlayerscanleadtoan increase in porosity and non-uniformity in the microstructure.Inaddition,partsproducedusingAMmay undergo hot isostatic pressing (HIP) treatment to reduce stresses and minimise remaining porosity. The author discoveredthatHIPtreatmentat850°Cforfourhoursand a pressure of 102 MPa transformed the as-fabricated martensiticmicrostructurewhilealsoreducingporosity.

Ti-6Al-4V is a challenging material to process due to its high melting temperature, thermal conductivity, and reactivity with atmospheric gases. One of the key advantages of LBM for processing Ti-6Al-4V is the ability to achieve a fine and homogeneous microstructure with a refined α/β grain size distribution, which contributes to the high strength, low weight, and superior corrosion resistancepropertiesofthematerial.Several studieshave investigatedtheeffectofLBMprocessingparameters,such aslaserpower,scanningspeed,andlayerthickness,onthe microstructureandmechanicalpropertiesofTi-6Al-4V.

Studies have shown that using high laser powers and scanning speeds can result in a refined microstructure withauniformα/βgrainsizedistribution.Incontrast,low laserpowersandscanningspeedscanleadtocoarserα/β grains and an increased presence of β-phase, which can negativelyaffectthemechanicalpropertiesofthematerial. Layer thickness also plays a critical role in the

3.3 EBM of Ti-6Al-4V

Thisresearch paperinvestigatesthemicrostructure of Ti6Al-4V parts produced using Electron Beam Melting (EBM).Theresearchindicatesthatthestructureonasmall scaleofthecomponentstypicallyconsistsoflargeinitialβgrains that change into a finely layered α configuration with a low amount of remaining β. EBM involves the selectivemeltingofsuccessivelayersofTi-6Al-4Vpowder using a high-energy electron beam in a vacuum environment. The electron beam's energy melts the powderparticles,whichsolidifytoformthefinalpart.The microstructure of Ti-6Al-4V produced through EBM is characterised by a columnar α-grain structure with a fine acicular martensitic β-phase distributed within the αgrains.

SeveralfactorscaninfluencethemicrostructureofTi-6Al4V produced through EBM, including the beam energy, beam current, scan speed, layer thickness, and powder size distribution. For instance, higher beam energy and current result in a higher melting rate and faster cooling rate, which lead to a finer microstructure. Studies have shown that the microstructure of Ti-6Al-4V produced through EBM is highly anisotropic, with a directional dependenceonmechanicalproperties.

4. Tensile Properties of AM Fabricated Titanium and Titanium Alloys

Tensiletestingisastandardmethodforcharacterisingthe mechanical properties of materials, including the tensile strength, yield strength, and elongation. Several studies have investigated the tensile properties of AM-fabricated titaniumusingvariousAMprocesses.Forinstance,Murret al. (2012) investigated the tensile properties of SLMfabricated Ti-6Al-4V alloy and compared them with conventionally produced Ti-6Al-4V alloy. The study found that the SLM-fabricated alloy exhibited similar or slightly higher yield strength, tensile strength, and elongation compared to the conventionally produced alloy.

Similarly, Zhao et al. (2018) investigated the tensile propertiesofEBM-fabricatedTi-6Al-4Vandpuretitanium. The study found that the EBM-fabricated Ti-6Al-4V alloy exhibited similar yield strength and tensile strength compared to the conventional Ti-6Al-4V alloy, but with lower elongation. The EBM-fabricated pure titanium showed a higher yield strength and lower elongation comparedtotheconventionalmaterial.Inadditiontopure titanium, several studies have investigated the tensile properties of AM-fabricated titanium alloys. For instance, Gong et al. (2016) investigated the tensile properties of SLM-fabricated Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-5Al-2.5Fe alloys. The study found that both alloys exhibited similar or slightly higheryieldstrengthandtensilestrengthcomparedtothe conventionallyproducedalloys,butwithlowerelongation.

5. Post-processing and Defect Management

Post-processing and defect management are critical aspects of metal additive manufacturing (AM) that affect the quality, reliability, and performance of the final product.Inthissection,wewill discussthecommonpostprocessing techniques used in metal AM, as well as the various types of defects that can arise during the process andtheircorrespondingmanagementstrategies.

5.1 Support, Powder & Substrate removal

Support, powder, and substrate removal are important aspects of metal additive manufacturing (AM) that affect the surface finish and dimensional accuracy of the final product. In this section, we will discuss the common techniques used for support, powder, and substrate removalinmetalAM.

Support structures are used in metal AM to provide support for overhanging features during printing. After printing, the support structures must be removed carefully to avoid damaging the printed part. Powder removal is necessary in metal AM to remove excess powder that has not been fused during printing. Excess powder can affect the surface finish and dimensional accuracy of the printed part. Substrate removal is necessary in metal AM to separate the printed part from the build platform. Substrate removal can be challenging,especiallywhentheprintedparthascomplex geometriesorfeaturesthataredifficulttoaccess.

5.2 Post-processing

Post-processing is an essential step in additive manufacturing (AM) to improve the mechanical properties,surfacefinish,anddimensionalaccuracyofthe finalproduct. Ti6Al4Visapopulartitaniumalloyused inAMduetoitsexcellentmechanicalproperties,corrosion

resistance, and biocompatibility. In this section, we will discuss the various post-processing techniques used in Ti6Al4V AM and their impact on the final product's properties.

Heat treatment is a commonly used post-processing technique in Ti6Al4V AM to improve the alloy's mechanical properties. The most common heat treatment process used is the solution treatment, which involves heating the printed part to a specific temperature (typically between 900-950°C) for a set period, followed by quenching in water or oil. The solution treatment improves the alloy's mechanical properties by dissolving the alpha phase, resulting in a more homogeneous microstructure.

5.4 Surface finishing

5.3 Stress relief

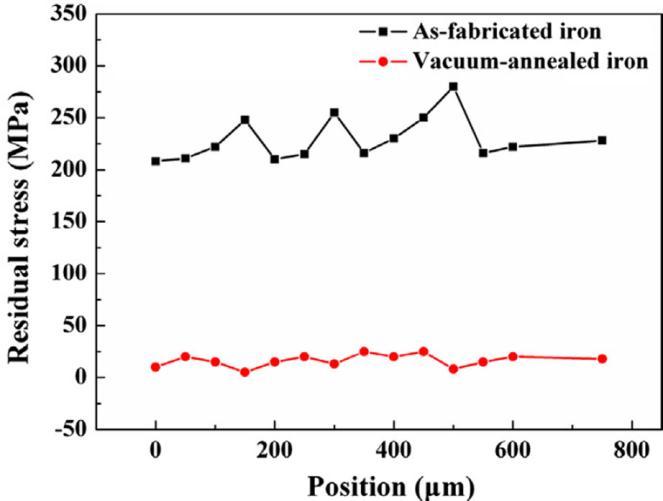

To alleviate stress in materials, elevated temperatures accelerateatomicdiffusion,causingatomstomigratefrom high-stressareastolow-stressregions,whichleadstothe release of internal strain energy. Prior to the removal of SLM and DED parts from the substrate, annealing is typically performed to eliminate any residual stress (as illustrated in Figure 8). Stress-relief treatments should be performedata temperature thatpermitsatomicmobility, butforadurationthatpreventsgrainrecrystallizationand growth(unlessintentionallydesired),asthisoftenresults in reduced strength. In metal AM processes, recrystallization can be advantageous to facilitate the formation of equiaxed microstructures instead of columnarmicrostructures.Iniron,thermalresidualstress isthoughtto bethedriving force behindrecrystallization, although this occurs without cold working. Similarly, similarphenomenahavebeenobservedinwire-fedDED.

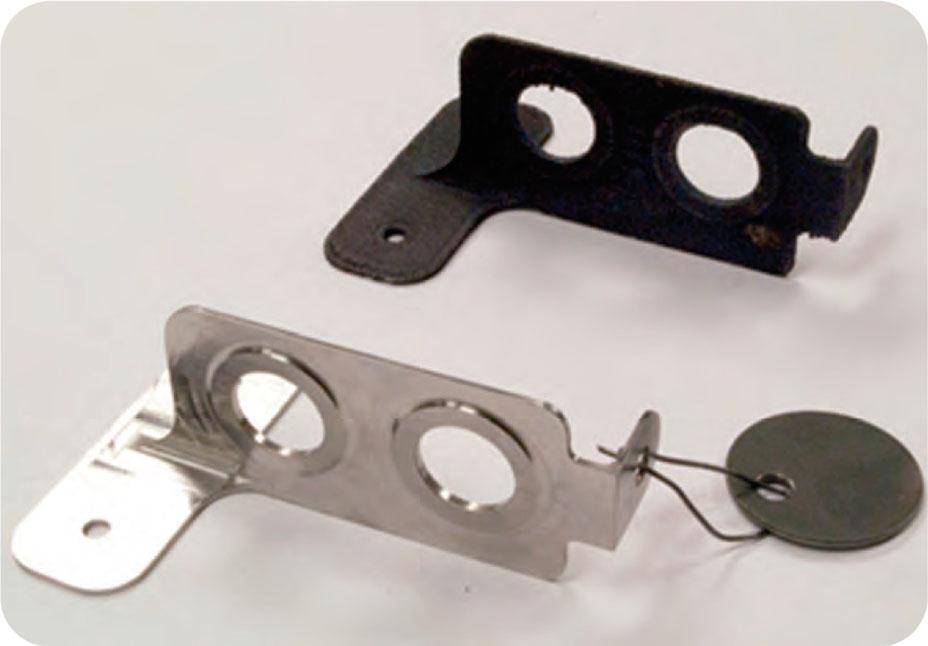

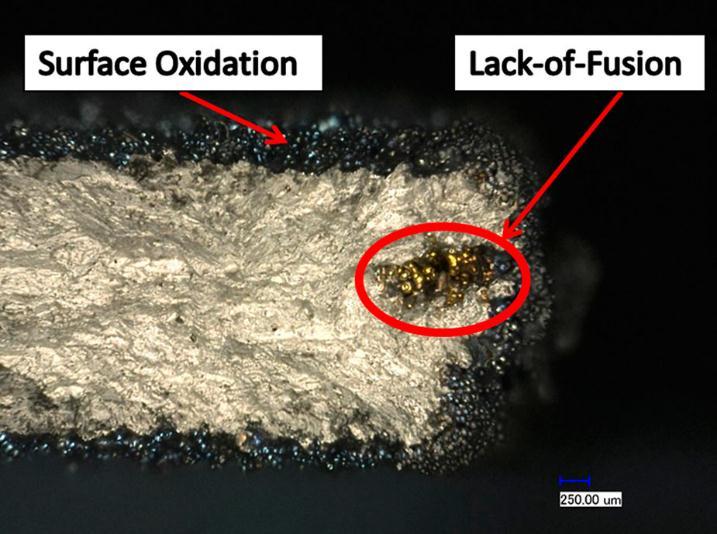

Surface finishing is another important post-processing technique in Ti6Al4V AM that can improve the surface texture and reduce surface roughness. Surface finishing techniques include mechanical polishing, chemical polishing, and electropolishing. Mechanical polishing involves using abrasive media to remove surface defects and roughness. Chemical polishing involves immersing the printed part in an acid solution to remove surface roughness. Electropolishing involves applying an electric current to the printed part while immersed in an electrolyte solution to remove surface defects and improve the surface finish. Parts intended for use in service are usually subjected to post-processing heat treatment,whichcancausesurfaceoxidationofthemetal. Figure 9 shows examples of post-HIP items before and after surface machining. For thin-wall EBM samples withopenpores,oxidation canpenetrateintotheinterior ofthepart,asshowninFigure10.

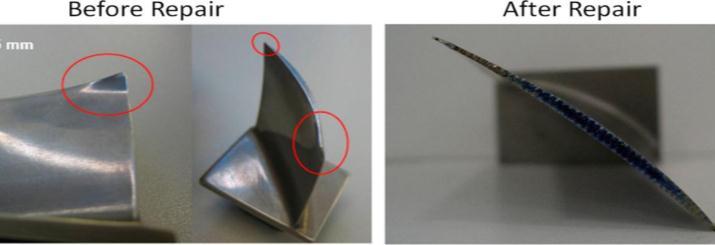

However, surface machining may not be sufficient to remove defects, which must be avoided. Tool path selection,toolorientation,andtoolgeometryhaveallbeen extensively studied in relation to CNC machining of freeform surfaces. AM and CNC have been investigated in combination, resulting in "hybrid manufacturing" or "hybridAM."Hybridsystemsofteninvolvea deadprocess with CNC, with the CNC tools mounted in the same location as the dead process. This hybrid approach is currently used to repair compressor blades and other complexservicepartsinaerospacecomponents.Figure11 depicts the restoration of turbine blades using this method. In Japan, Matsuura has developed LUMEX, a hybridtechnologythatcombinesSLMandCNC,whichcuts specific features after each layer. Unlike part repair, the LUMEX technique has found applications in tool and die fabrication.

6. Applications of Additive Manufacturing

6.1 Topological optimization

The process of topology optimization involves identifying the optimal structural configuration that satisfies a set of objectives, constraints, loads, and boundary conditions within a defined design space. The primary aim of topologicaloptimizationistoreducetheweightorvolume of a component while ensuring that it meets the operationalrequirementswithoutfailureoryielding.

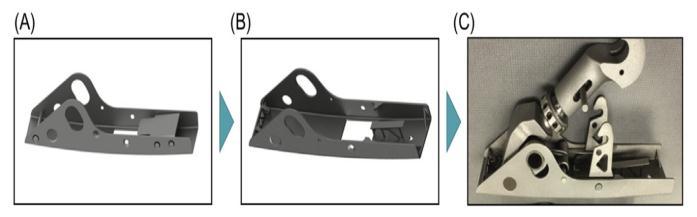

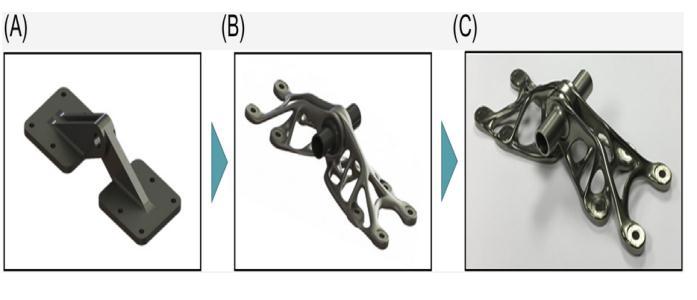

Inthisresearchpaper,wepresentanexampleoftopology optimization applied to an aircraft hinge product. The hinge's topology was altered to align with the current structural performance standards and optimised to minimiseitsoverallweight.Theresultingdesignwasthen manufacturedusinganAMlaserpowderbedtechnique,as illustrated in the accompanying photos. By changing the part's topology, the hinge's weight was significantly reduced, while ensuring it met the specified operational constraints.

This research paper explores how topology optimization can effectively utilise additive manufacturing to produce parts that were previously impossible to manufacture using traditional manufacturing methods. A prime example of this is illustrated in the hinge case study presented above. Furthermore, the industry has coined the phrase "Complexity is free" to emphasise the minimal cost difference in producing complex topologically optimisedpartscomparedtotheiroriginalcounterparts.

The process of optimization is a joint endeavour between finite element software packages and topology optimization.ThisalgorithmusesinformationfromtheFE model, which includes displacement, contact force, stress, and strain, to adjust a part's topology in an iterative manner until the desired goal is met within the application's limits. The current study examines topology optimization, its interaction with FE software packages, anditspossibilitiesinadditivemanufacturing.

6.2 Part Consolidation

The principle of consolidating parts involves decreasing the number of components in an assembly or structure composedofmultiplepartsintoaredesignedpartwiththe same operational capacity but fewer overall components. In this approach, additive manufacturing (AM) is used to simplify the assembly process by producing a single redesigned part. There are several advantages to using part consolidation in AM, including component simplification, possible performance improvement, and reduced tooling and fabrication time. Manufacturers can considerably decrease overhead costs associated with labour, tooling, part traceability, and inventory for that assembly by reducing the number of components. Furthermore, simplifying the components can make the product easier to operate and maintain from the user's standpoint.

6.3 Micro-Trusses

The unique capabilities of AM, such as the ability to produce complex geometries, have made it possible to design and fabricate micro-trusses with high strength-toweightratios,excellentenergyabsorptionproperties,and optimal stress distribution. These microtrusses can be used in various aerospace applications, such as aircraft wings, fuselage, and engine components, to improve performance, fuel efficiency, and reduce emissions. Furthermore, the use of AM microtrusses allows for customization and optimization of the design for specific performance requirements, making it an attractive option fortheaerospaceindustry.However,challengesremainin the design and optimization of micro-trusses, such as understanding the effect of different microstructure parameters on the mechanical properties and the development of reliable simulation models. Therefore, furtherresearchisrequiredtofullyrealisethepotentialof Amicro-trussesintheaerospaceindustry.

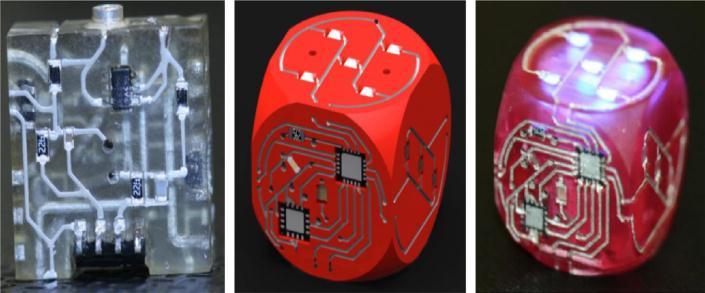

6.4 Circuits

The University of Texas has developed multifunctional components that incorporate integrated circuitry. To combineconductiveinkswithstructuralcomponents,they employed additive manufacturing techniques like fused deposition modelling and stereolithography. As shown in Fig. 14, they have created working prototypes of various components using this approach. This research places a high emphasis on incorporating electronics with other features, such as heat management, radiation shielding, strengthenhancement,andcontrolsystems.Themethod's potential uses for space applications, particularly in CubeSatsystems,arecurrentlyunderinvestigation.

pressures, as well as resist corrosion and wear. On the otherhand,dynamiccomponentsrefertopartsthatmove during engine operation, such as the turbine blades, compressor rotor, and bearings. These components must be designed to withstand high speeds, vibrations, and forceswhilemaintainingprecisetolerancesanddurability. The development of advanced materials and manufacturing techniques has led to significant improvements in the performance and durability of static and dynamic engine components, contributing to the increased safety and efficiency of modern aircraft in the aerospaceindustry.

One of the aerospace industry's most well-known AM applications is the LEAP engine fuel injector. The production of over 30,000 injectors began in 2015 and continued through 2018, with production still ongoing. Thefuelinjector,showninFig.16,wasfabricatedusingLPBFandiscurrentlyusedinmultipleenginesemployedin commercialaircraft.

6.5 Static and dynamic engine components

Static and dynamic engine components are crucial in the aerospace industry as they play a critical role in ensuring the safety and reliability of the aircraft. Static components refer to the parts that remain stationary during engine operation, such as the engine casing, exhaustsystem,andinletduct.Thesecomponentsmustbe designed to withstand extreme temperatures and

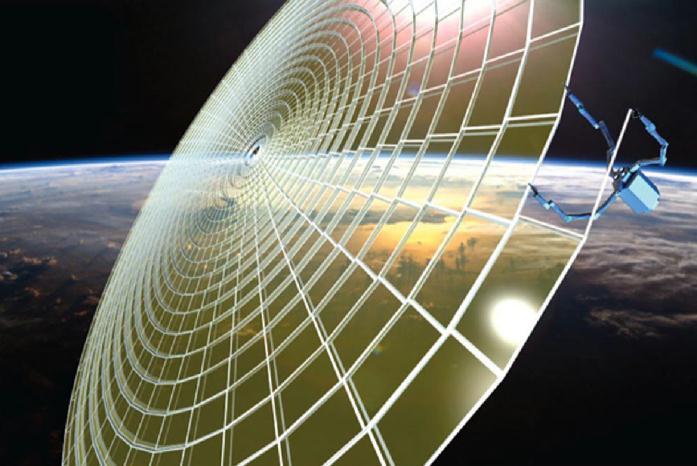

6.6 In Situ Fabrication and Assembly

The use of additive manufacturing technology in space flight presents an intriguing possibility for the on-site production of very large structures through robotics. Various design approaches can be utilised to construct kilometre-sized structures, which can be made with low strength since they will not be subjected to launch or gravity loads. This will considerably decrease the amount of raw material that needs to be transported into orbit. However, to fully realise the potential of these structures, they must be built and erected autonomously. For example, an antenna could be additively printed in space usingthisapproach.

Previous research has been conducted on the 3D printing of plastic components on the International Space Station to examine how microgravity impacts additive manufacturingprocesses.

6.7 In Situ Resource Construction

In situ resource construction is an emerging concept in additive manufacturing that has the potential to revolutionise the aerospace industry. The idea is to use AM technology to build structures and systems directly from materials that are available at the destination site, such as on a planetary surface or in space. This approach can greatly reduce the cost and complexity of space missions by eliminating the need to transport large amountsofmaterialfromEarth.Italsohasthepotentialto enable newcapabilities,suchastheconstruction oflargescale structures in space. Several research efforts are underwaytodevelopinsitu resourceconstructionforthe aerospace industry, including the advancement of AM systems that can work in low-gravity environments and theexplorationofnewmaterialsthatcanbeusedinspace. While there are still many technical challenges to be addressed, in situ resource construction represents a promising approach for enabling new frontiers in space explorationanddevelopment.

7.2 Upscaling methods

As the aerospace industry continues to adopt additive manufacturing (AM) for the production of complex components, there is a growing need to upscale the process for high-volume production. To achieve this, new methods are being developed to increase production rates and reduce costs while maintaining the high quality and reliability standards required by the industry. One promising approach is the use of multi-laser systems that can print multiple parts simultaneously, resulting in a significant increase in productivity. Additionally, advancements in material science are enabling the use of higher strength and temperature-resistant materials that can withstand the harsh environments encountered in aerospace applications. Another area of research involves the integration of AM with traditional manufacturing methods, such as casting and forging, to produce hybrid componentswiththebenefitsofbothprocesses. Asthe demand for AM in aerospace continues to grow, the developmentofthesefutureupscalingmethodswillplaya crucialroleinenablingtheindustrytomeetitsproduction needswhilemaintainingthehighstandardsofqualityand performancerequired.

8. Conclusion

Thisresearchpaperpresentsananalysisofvariouscritical domains of additive manufacturing, highlighting its potential to revolutionise the manufacturing industry. Additive manufacturing, however, comes with various difficulties, including distinct quality control demands, inadequate high-volume production speeds, restricted material accessibility, complications in post-processing, potential impairment of fatigue characteristics, high machinery expenses, and a requirement for specialised knowledgetofabricatefunctionalcomponents.

7. Future modelling and simulations

7.1 Uncertainty quantification and optimization

The authors emphasise the increasing significance of comprehendingandcomputingtheerrorpropagationrate during AM simulations. It is important to conduct comprehensive uncertainty quantification (UQ) of diverse physicalandprocessingcharacteristicstocomprehendthe fundamentalfactorsthatinfluencethequalityofpartsand accurately forecast their properties. This project is essential in optimising AM processes through in-silico approaches by reducing the number of trial-and-error experiments required to find optimal process parameters and conditions. This facilitates improvement in part qualitiesandcostreduction.

To establish additive manufacturing as a dominant player in the manufacturing industry, several improvements are necessaryinthefollowingareas:

1. Enhancingproductionrates.

2. Reducingcosts.

3. Developing new alloys suitable for additive manufacturingandaerospaceapplications.

4. Implementing in situ monitoring and accurate flawidentification

5. Usingbuiltsimulationtoidentifyrisks

6. Exploringadditivemanufacturingforin-spaceand non-terrestrialapplications.

7. Widening the use of architected cellular structures(lattices).

8. enabling the development of multifunctional components such as integrated electronics and sensorsinadditivemanufacturingprocesses.

Addressing these challenges can significantly improve the adoption of additive manufacturing and pave the way for itsintegrationinvariousindustrialapplications.

9. REFERENCES

1. D.Herzog,etal.,Additivemanufacturingofmetals, Acta Materialia (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.actamat.2016.07.019

2. M. Perrut, P. Caron, M. Thomas, and A. Couret, High temperature materials for aerospace applications: Ni-based superalloys and c-TiAl alloys, C.R. Phys. 19 (8) (2018) 657–671, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crhy.2018.10.002

3. G.J. Schiller, Additive Manufacturing for Aerospace, in: 2015 IEEE Aerospace Conference, 2015,pp.1–8.doi:10.1109/AERO.2015.7118958

4. D. Waller, A. Polizzi, J. Iten, Feasibility study of additively manufactured Al6061 RAM2 parts for aerospace applications, 2019.

https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2019-0409

5. J.C.Najmon,S.Raeisi,A.Tovar,Reviewofadditive manufacturing technologies and applications in the aerospace industry, in: Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 7–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-8140628.00002-9

6. R. Liu, Z. Wang, T. Sparks, F. Liou, J. Newkirk, Aerospace applications of laser additive manufacturing, in: Laser Additive Manufacturing: Materials,Design,Technologies,andApplications, Elsevier, 2017, pp. 351–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-1004333.00013-0

7. Zhu, JH., Zhang, WH. & Xia, L. Topology OptimizationinAircraftandAerospaceStructures Design. Arch Comput Methods Eng 23, 595–622 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11831-0159151-2

8. Additive Manufacturing for Aerospace Flight Applications. A. A. Shapiro, J. P. Borgonia, Q. N. Chen, R. P. Dillon, B. McEnerney, R. Polit-Casillas,

andL.Soloway.JournalofSpacecraftandRockets 2016 53:5, 952-959. https://doi.org/10.2514/1.A33544

9. Casalino, G., Campanelli, S. L., Contuzzi, N., and Ludovico, A. D.,“Experimental Investigation and Statistical Optimisation of the Selective Laser Melting Process of a Maraging Steel,” Optics and LaserTechnology,Vol.65,Jan.2015,pp.151–158.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optlastec.2014.07.021

10. Buchbinder, D., Schleifenbaum, H., Heidrich, S., Meiners, W., and Bültmann, J., “High Power Selective Laser Melting (HP SLM) of Aluminum Parts,” Physics Procedia, Vol. 12, Pt. A, 2011, pp. 271–278.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2011.03.035

11. Bertrand,P.,Bayle,F.,Combe,C.,Goeuriot,P.,and Smurov, I.,“Ceramic Components Manufacturing by Selective Laser Sintering,”Applied Surface Science, Vol. 254, No. 4, 2007, pp. 989–992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2007.08.085

12. Strondl, A., Lieckfeldt, O., Brodin, H., and Ackelid, U., “Characterization and Control of Powder PropertiesforAdditiveManufacturing,”Journalof the Minerals Metals and Materials Society, Vol. 67,No. 3, 2015, pp. 549–554. doi:10.1007/s11837-015-1304-0.

13. Slotwinski, J. A., Garboczi, E. J., Stutzman, P. E., Ferraris, C. F.,Watson, S. S., and Peltz, M. A., “Characterization of Metal Powders Used for Additive Manufacturing,” Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Vol. 119, Sept. 2014, pp. 460–493. http://dx.doi.org/10.6028/jres.119.018

14. Christiansen, A. N., Bærentzen, J. A., NobelJørgensen, M., Aage, N.,and Sigmund, O., “Combined Shape and Topology Optimization of 3D Structures,” Computers and Graphics, Vol. 46, Feb. 2015, pp. 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cag.2014.09.021

15. Espalin, D., Muse, D. W., MacDonald, E., and Wicker, R. B., “3D Printing Multifunctionality: StructureswithElectronics,”InternationalJournal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, Vol. 72, Nos. 5–8, 2014, pp. 963–978. doi: 10.1007/s00170-014-5717-7

16. S.C. Joshi, A.A. Sheikh, 3D printing in aerospace and its long-term sustainability, Virt. Phys. Prototyp. 10 (4) (2015) 175

185, https://doi.org/10.1080/17452759.2015.111151

17. R. Russell, et al., Qualification and certification of metal additive manufactured hardware for aerospace applications, in: Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry, Elsevier, 2019, pp. 33–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-8140628.00003-0

18. A. Fatemi, R. Molaei, S. Sharifimehr, N. Shamsaei, N. Phan, Torsional fatigue behaviour of wrought and additive manufactured Ti-6Al-4V by powder bed fusion including surface finish effect, Int. J. Fatigue 99 (2017) 187–201, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2017.03.002.

19. A. Uriondo, M. Esperon-Miguez, S. Perinpanayagam, The present and future of additive manufacturing in the aerospace sector: a review of important aspects, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng., Part G: J. Aerospace Eng. 229 (11) (2015) 2132–2147, https://doi.org/10.1177/0954410014568797

20. P. Rambabu, N. Eswara Prasad, V. v. Kutumbarao, R.J.H. Wanhill, Aluminium Alloys for Aerospace Applications,2017,pp.29–52.DOI:10.1007/978981-10-2134-3_2

21. J.C.Williams,R.R.Boyer,Opportunitiesandissues intheapplicationoftitaniumalloysforaerospace components, Metals 10 (6) (2020) 705, https://doi.org/10.3390/met10060705

22. K. Minet, A. Saharan, A. Loesser, N. Raitanen, Superalloys, powders, process monitoring in additive manufacturing, in: Additive Manufacturing for the Aerospace Industry, Elsevier Inc., 2019, pp. 163–185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-8140628.00009-1

23. W.J.Sames,F.A.List,S.Pannala,R.R.Dehoff&S. S. Babu (2016) The metallurgy and processing science of metal additive manufacturing, International Materials, 61:5, 315-360, DOI: 10.1080/09506608.2015.1116649

24. Byron Blakey-Milner, Paul Gradl, Glen Snedden, Michael Brooks, Jean Pitot, Elena Lopez, Martin Leary, Filippo Berto, Anton du Plessis, Metal additive manufacturing in aerospace, Materials & Design, Volume 209, 2021, 110008, ISSN 02641275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2021.110008

25. D. L. Bourell, H. L. Marcus, J. W. Barlow, and J. J. Beaman, "Selective laser sintering of metals and ceramics," International journal of powder metallurgy, vol.28,pp.369-381,1992.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2016.08.084

26. L. N. Carter, M. M. Attallah, and R. C. Reed, "Laser Powder Bed Fabrication of Nickel-Base Superalloys: Influence of Parameters; Characterisation, Quantification and Mitigation of Cracking," in Superalloys 2012, ed: John Wiley & Sons,Inc.,2012,pp.577-586.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2022.118307

27. L. N. Carter, C. Martin, P. J. Withers, and M. M. Attallah, "The influence of the laser scan strategy ongrainstructureandcrackingbehaviourinSLM powder-bedfabricatednickel superalloy," Journal of Alloys and Compounds, vol. 615, pp. 338-347, 12/5/ 2014

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2014.06.172