Review of Steady-state Building Heat Transfer Algorithms Developed for Climate Zones of India

Abdullah Nisar Siddiqui11 Research Scholar, Department of Architecture, Faculty of Architecture and Ekistics, Jamia Millia Islamia (A Central University), New Delhi, India ***

Abstract –

India is nation of over 1.4 billion people, constituting more than 17% of the global population. The building sector in India accounts for a third of electricity consumption and carbon emissions. To achieve sustainable development, the country needs to prioritize energy-efficient building designs that cater to local climatic conditions. In India, the Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) prescribes the use of Envelope Performance Factor (EPF) based on Overall Thermal Transmittance Value (OTTV) for building envelope design to minimize the energy consumption of buildings. The OTTV is a measure of the overall thermal transfer through the building envelope, and it is influenced by various parameters such as building orientation, façade area, shading devices and thermal properties of envelope components.

This paper delves into the various OTTV-based steady-state heat transfer algorithms developed for Indian climatic zones. The study provides an overview of the different approaches used for developing these algorithms, including energy simulation, parametric studies, and regression analysis. The review also discusses the key input parameters required for the development of these steady-state heat transfer algorithms. The algorithms are compared based on their scope of applicability and development methodology. The review also discusses the limitations associated with the use of these algorithms in accurately predicting the performance of Building Envelope This paper highlights the importance of steady-state heat transfer algorithms in energy-efficient building design in developing countries like India. It emphasizes on the importance of continued research to refine these algorithms and develop reliable OTTV-based algorithms for Indian climatic zones.

Key Words: OTTV, Buildings, Energy Efficiency, Building EnergyCodes,BuildingEnvelope

1 INTRODUCTION

Steady-state building physics-based models are simplified mathematical models that are based on the fundamental laws of thermodynamics and heat transfer. These steadystate models are used to predict the thermal performance of building envelopes and to optimize the thermal performance of building envelopes. The equation-based

algorithms can be classified into three broad categories basedontheapproach[1]:

Analytical approach (includes both dynamic and steady-state models for detailed heat transfer calculations with well-defined boundary conditions)

Approximation approach (steady-state models for heatloadcalculationsusingHDD/CDD)

Correlational approach (steady-state models for location specific values/curves developed using hourlysimulations)

1.1 Development of OTTV algorithm

The ASHRAE Standard 90-1975 “Energy Conservation in New Building Design” was the first standard to include OverallThermalTransmittanceValue(OTTV)requirement forupcomingair-conditionedlargebuildings[2].TheOTTV algorithmproposedbyASHRAErepresentsthepeakrateof heat transmission from the external ambient environment into the building through the exposed envelope components Itrepresentstherateofheattransferthrough thebuildingenvelopeperunitarea,betweentheinsideand outside of the building. It considers the following three heat transfer components to quantify the overall thermal performanceofthebuildingenvelope:

Conductiveheattransmissionviaexternalwall (Qwall.C)

Conductiveheattransmissionviaexternal fenestration(Qfenestration.C)

Radiative(solar)heattransmissionviaexternal fenestration(Qfenestration.R)

The simplified OTTV equation developed by ASHRAE is showninEquation1

Equation 1

The OTTV approach was further enhanced by incorporating a similar algorithm for heat transmission through roofs and skylights in the revised version of ASHRAEStandard90A1980“EnergyConservationinNew Building Design” [3]. The simplified OTTV (roof) equation developedbyASHRAEisillustratedinEquation2.

Equation 2

Where,

isconductiveheattransmissionviaroof is conductive heat transmission via skylight is radiative (solar) heat transmission via skylight

TheOverallThermalTransmittanceValue(OTTV)hasbeen an important concept in the building industry for over 40 years. Its main objective is to serve as an indicator of the impact of a building's envelope on the energy used for providing thermal comfort predominantly in airconditioned buildings. To use OTTV as a measure of thermal performance, it is crucial to have accurate coefficients for each envelope component. The accuracyof these coefficients depends upon how well they are ableto representtheinteractionofbuildingenvelopecomponents with local climate conditions. Recent studies have highlighted the assumptions made by various researchers when computing OTTV coefficients and have emphasized thatthecalculationofOTTVshouldbebasedonheatgains evaluated using fixed thermostat setpoints and airconditioningoperationschedules[4][5][6]

J. Vijayalaxmi (2010) suggests that certain design modificationsatanearlystagecansignificantlyreducethe OTTVvalue[9].ItalsosuggeststhattheOTTVvalueatthe time of maximum solar radiation intensity is a good benchmark for evaluating the thermal performance of building envelopes in hot-humid and hot-dry countries. However, this benchmark may not be suitable for cold climates, where the focus should be on reducing heating loads. Additionally, the author suggests that early design stageoptionsforvaryingwallingmaterialandglazingtype for wall orientation where the OTTV is high should be considered as preventive measures for reducing heat gain andloadonairconditioners[9]

2 OTTV IN BUILDING ENERGY CODES

Singapore became the first country to include OTTV requirements in their building regulations in 1979 for airconditioned buildings. Subsequently in 2004, it was supersededbyarevisedalgorithm“RoofThermalTransfer Value” (RTTV) and “Envelope Thermal Transfer Value” (ETTV) in favour of an improved representation of fenestration solar gains [10]. A similar OTTV based algorithm (RETV) was incorporated in 2008 by Building and Construction Authority, Singapore to include residentialbuildingsaswell[11]

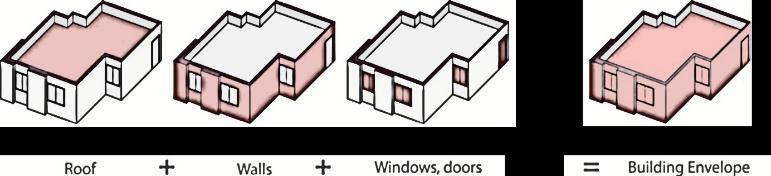

Fig. 1: ComponentsofBuildingEnvelopeforOTTV [7]

Hui (1997) argues that an OTTV based performance standard should be the first step toward the development of a national building energy code [6]. W. K. Chow & K. T. Chan (1995) have discussed the application of the Overall Thermal Transfer Value (OTTV) equation to evaluate the cooling load of buildings [8]. The study found that the Window-to-Wall Ratio (WWR) and Solar Heat Gain Coefficient (SHGC) are significant factors in determining the thermal performance of building envelopes. The sensitivity of these parameters can provide guidance to building designers on how to optimize the thermal performance of building envelopes and make trade-offs among parameters to meet desired heat transfer limits. However,thestudyalsofoundthattheOTTVequationdoes not fully reflect the effects of wall absorptance and heat capacity. To account for this, the authors propose modifyingtheOTTVequationbyaddingacorrectionfactor tothetermTDeq [8]

ResidentialEnvelopeTransmittanceValue(RETV)isbased on the concept of Overall Thermal Transfer Value (OTTV) developed by ASHRAEas it represents the average rate of heat transmission from the external ambient environment into the building through the exposed envelope components. Higher heat gain taking place through the building envelope would translate into a higher RETV value. A number of countries such as India, Singapore, ThailandandHongKonghaveusedRETVintheirbuilding codes [6]. Unfortunately, there isn't much information in the literature on the precise methods employed by these nations to develop the algorithm and compute the coefficients. The OTTV based algorithms have been developed for integration in nation building energy codes of Singapore (2008), Hong Kong (2019), Thailand (2017), Malaysia (2007), Indonesia (2011), Jamaica (1994), Vietnam,SriLanka(2009),Mauritius,Pakistan(1990)and Egypt(2005)amongothers.

Acomparisonofalgorithmsdevelopedbycountrieshaving comparableclimaticconditionsislistedinTable1.

International Research

Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Country Code Equation Limit forBuildings [11] +4.8(SKR)Us+ 485(SRR)(CF)(SC) W/m2

RETV=3.4(1WWR)Uw + 1.3(WWR)Uf + 58.6(WWR)(CF)(SC)

Country Code Equation Limit

Us×ΔT×(SRR)

Where,

Malaysia

Codeof Practiceon Energy Efficiency andUseof Renewable Energyfor NonResidential Buildings [12]

OTTV=15×α×(1WWR)Uw +6× (WWR)×Uf + (194×CF×WWR×SC)

50 W/m2

SriLanka

Codeof practicefor energy efficient buildingsin SriLanka [16]

TDEQr variesdepending upondensityofroof construction;andΔTis differencebetween indoorandoutdoor temperatures

OTTV=19.3×α×Uw × (1-WWR)+3.6×Uf× (WWR)+186× (SC×CF×WWR)

Where,

OTTVwall =Uw ×TDEQw ×α(1-WWR)+ (SF×SC×WWR)

Hong Kong

Codeof Practicefor Overall Thermal Transfer Valuein Buildings [13]&[14]

OTTVroof =α×Ur × TDEQr (1-SRR)+(264× SC×SRR)

Where, TDEQw variesbetween 7.9to18.6depending upondensityofroof construction

OTTVwall =Uw ×TDEQw ×(1-WWR)+ (SF×SC×WWR)+ Ug×ΔT×(WWR)

21 W/m

for building tower; and50 W/m

for podium

Jamaica

Jamaica National Building CodeVolume2: Energy Efficiency Building Code, Requirement sand Guidelines [17]

CFvariesbetween0.79 to1.34depending upontheorientation; andSCvaries dependinguponthe projectionfactorand typeofshadingdevice

OTTVw =(TDeq–DT)× CF×α×Uw ×(l-WWR) +DT×Uw ×(1-WWR) +(372×CF×SC× WWR)+(DT×Uf × WWR)

Where,

TDEQw variesbetween 10.6–24.4depending upondensityofwall construction;DT variesbetween6.1–9.4dependingupon climaticzone;andCF variesbetween0.58to 1.36dependingupon theorientation

50 W/m2

Pakistan Building EnergyCode ofPakistan [15]

–

91

Where,

TDEQw variesbetween 16.1–38.9depending upondensityandUvalueofroof construction;andDT variesbetween6.1–9.4dependingupon climaticzone

55.1–

67.7 W/m2

20 W/m2

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 10 Issue: 02 | Feb 2023 www.irjet.net

Budgetmethodandmoreadvancedwholebuildingenergy simulation. Nevertheless, many countries (predominantly Asiancountries)continuedwiththedevelopmentofnation specific OTTV algorithms and incorporated them in their respectivebuildingcodeswithvaryinglevelsofstringency and enforcement (voluntary or mandatory) [7] Interestingly,thereareseveraladvantagesofusingsteadystateheattransfermodelsforoptimizingbuildingenvelope performance over advanced building energy simulation software:

1. Simplicity: Steady-state heat transfer models are relatively simple to understand and use, and they do not require specialized knowledge or skills to implement.Thiscanmakethemmoreaccessibleto building designers and engineers in developing countries, who may not have the resources or expertise to use advanced building energy simulationsoftware.

2. Low Computational Requirements: Steady-state heat transfer models require less computational resources compared to advanced building energy simulationsoftware,whichmeanstheycanberun onlower-endcomputersandcanbeusedinareas wherecomputationalresourcesarelimited.

3. Low Cost: Steady-state heat transfer models are typically less expensive than advanced building energysimulationsoftware,whichcanmakethem more accessible to organizations and individuals indevelopingcountries.

4. Easy to Validate: The results of steady-state heat transfer models are relatively easy to validate usingsimplespreadsheetbasedtools.

5. EasytoUse:Steady-stateheattransfermodelsare easytouseanddonotrequireadvancedtechnical knowledge, they can be implemented by building designersandengineerswithbasicunderstanding ofheattransferprinciples.

6. Easy to Modify: Steady-state heat transfer models are relatively easy to modify to reflect changes in building design, construction materials, and externalclimateconditions.

7. GoodforBenchmarking:Becausesteady-stateheat transfer models are relatively simple, they can be used to establish a benchmark for building envelope thermal performance. This can help to identify areas where improvements are needed and to evaluate the effectiveness of different designoptions.

ThemajorlimitationofOTTVbasedapproachisitsreliance on steady-state heat transfer calculations, which don’t accurately represent the dynamic thermal behaviour of building envelope components. This can also lead to

oversimplification of building envelope thermal performance, as it does not account for the impact of variance in internal loads, operation schedules and ventilation gains on energy consumption of airconditioningsystemsforprovidingthermal comforttothe occupants. Hence, few developed nations along with ASHRAE shifted toward more advanced methods in their building codes, such as building energy simulations, that provide a more accurate representation of the dynamic thermal performance of buildings. These advanced building energy simulation tools also enable trade-offs between all building services including lighting systems and air-conditioning systems in addition to building envelope components. However, it is noteworthy that OTTV based algorithms are still used by many developing nations, particularly Asian countries in their building energy codes. The major reasons behind these developing countries still depending upon steady-state algorithms in theirnationalbuildingenergycodesarelistedbelow:

1. Technicalconstraints:manydevelopingnationsdo not necessarily have enough professionals possessing the required technical capacity or resources across the geographical territory to implement advanced methods such as building energy simulations. Therefore, the use of simpler steady-state algorithms for code compliance is better suited and more feasible for ensuring effectiveimplementationofthesenationalbuilding energycodes.

2. Historicalfactor:mostofthesedevelopingnations had adopted steady-state algorithm approach for codecomplianceinearlyversionsoftheirbuilding energy codes, and since then have decided to retainitintheupdatedversionsofbuildingenergy codes.

3. Cost: performing building energy simulations can be expensive and time-consuming, while it may notnecessarilyprovidemeaningfulvalue-addition to comparatively smaller projects or the projects which are already at final stages of design or construction. The cost includes both the cost of simulation software and the professional fee of experts. Hence, implementing these advanced simulationmethodscanbeprohibitiveforprojects withlimitedbudgetsandtime.

4. Ease of compliance: many developing countries are still in the nascent stages of implementing building energy codes. Hence, the adoption of the steady-statealgorithmapproachisamorefeasible first step toward enhancing energy efficiency of the building sector. The compliance using steadystate algorithm approach can be demonstrated usingmuchsimplerspreadsheetsandiseasierfor implementingagencytoverifyaswell.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 10 Issue: 02 | Feb 2023 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

5. Lack of awareness: the majority of primary stakeholders including real-estate developers in these developing countries are still not aware of the benefits of using more advanced building energy simulation methods. Until the integrated design processes for building projects are mainstreamed through enhanced awareness, the incorporation of building energy simulation methodswouldremainachallenge.

WhileASHRAEalong with other developedcountrieshave transitionedawayfromusingsteady-statealgorithmbased approach in their building energy codes [18], many developing countries including India are still using it in theirbuildingenergycodes[19].

3 STEADY-STATE BUILDING HEAT TRANSFER ALGORITHMS FOR INDIA

India is predominantly a cooling-dominated country [20] Therefore, to restrict the heat transfer through building envelope,theENS(Part-I)limitstheRETVtoamaximumof 15W/m2 forallclimaticzonesexceptcold.TheENS(PartI) is the first national code that evaluated thermal performance of building envelope in terms of RETV. The major advantage of RETV is that it provides flexibility to the designer to trade-off between the efficiencies of envelope components (walls, fenestration, and shading) whileensuringoverallenvelopeefficiency[9]

Devgan, et al. (2010) have proposed and verified a set of overallthermaltransfervalue(OTTV)coefficientsforthree Indian climatic zones [4]. The proposed algorithm and coefficients can be used to compute the OTTV value for day-time use air-conditioned office buildings located in selected climatic zones. The study found that OTTV corresponds effectively with annual space cooling and heatingenergyconsumption.

Acomparableapproachhasbeenfollowedinthe“Building Envelope Trade-off Method” provided in ECBC that uses the Envelope Performance Factor (EPF) to quantify the thermal performance ofthebuilding envelope [21][22].A higher value of EPF would signify higher rates of heat transfer through the building envelope and imply lower levels of thermal efficiency [23]. However, unlike EcoNiwas Samhita 2018 (Part-1) and other international building energy codes, ECBC doesn’t provide a fixed value for EPF to restrict heat transfer through the building envelope.Rather,ECBCutilizesacomparativeapproachto demonstrate compliance with the code. To achieve compliance, the EPF of the proposed design calculated using the spatial design parameters and thermo-physical properties of actual envelope assemblies shall be equal to or less thanthe EPFof reference casecalculated usingthe thermo-physical specifications mentioned in the prescriptiveprovisionsforrespectiveenvelopecomponent [22]

3.1 Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC)

ECBC 2007 uses the following equation for calculating EnvelopePerformanceFactor(EPF)[21]:

Equation 3 EPF

Where,

An isnetareaofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

Un isU-factorofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

SHGCn isSHGCofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

Croof varies between 5.46 and 11.93 depending upon buildingoperationandclimatezone

Cwall varies between 2.017 and 15.72 depending upon climatezoneandmass

CwindowU varies between -11.95 and 1.55 depending upon building operation, climate zone and orientation (north&non-north)

CwindowSHGC varies between 9.13 and 86.57 depending upon building operation, climate zone and orientation (north&non-north)

CskylightU varies between -295.81 and -93.44 depending uponbuildingoperationandclimatezone

CskylightSHGC varies between 283.18 and 923.01 depending uponbuildingoperationandclimatezone

Mwindow is the multiplication factor for equivalent SHGC and varies depending upon latitude (≥15 N & <15 N), orientation, type and projection factor of shadingdevice

Similarly, ECBC 2017 with slight modifications uses the following equation for calculating Envelope Performance Factor[22]:

Equation 4

EPF = Croof × Uroof × Aroof + Cwall × Uwall × Awall + CwindowU × Uwindow × Awindow + CwindowSHGC × SHGCwindow × Awindow ÷ SEFwindow

Where,

An isnetareaofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

Un isU-factorofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

SHGCn isSHGCofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 10 Issue: 02 | Feb 2023 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Croof varies between 32.3 and 80.7 depending upon buildingoperationandclimatezone

Cwall varies between 17.2 and 55.9 depending upon climatezone

CwindowU varies between 10.9 and 49.2 depending upon building operation, climate zone and orientation (north,south,east&west)

CwindowSHGC variesbetween114.3and607.4dependingupon building operation, climate zone and orientation (north,south,east&west)

SEFwindow is the shading equivalent factor for SHGC and varies depending upon latitude (≥15 N & <15 N), orientation, type and projection factor of shading device

It is important to note that ECBC doesn’t provide a threshold EPF value for achieving compliance, rather it utilizesacomparativeapproach.IftheEPFoftheproposed designisequaltoorlessthantheEPFofthereferencecase developed using prescriptive provisions, the building envelopeisconsideredtobecode-compliant[22]

3.2 Eco-Niwas Samhita 2018 (Part-1)

TheRETVcomplianceprovisionincorporatedinEco-Niwas Samhita 2018 (Part-1), in principle is much closer to the standard OTTV concept. The threshold value to demonstratecompliancewiththecodehasbeenfixedat15 W/m2 [19]. Unlike ECBC 2017 which has provided EPF basedcomplianceprovisionforallfiveclimaticzones,ENS 2018 provides the steady-state RETV algorithm only for cooling-dominated climatic zones (Hot-Dry, Composite, Warm-Humid, and Temperate). The equation developed forcalculatingRETVisplacedbelow:

Equation 5

Where,

Un isU-factorofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

SHGCn is equivalent SHGC of respective envelope component

a varies between 3.38 and 6.06 depending upon climatezone

b varies between 0.37 and 1.85 depending upon climatezone

c varies between 63.69 and 68.99 depending upon climatezone

ω istheorientationfactorthatvariesbetween114.3 and 607.4 depending upon latitude (≥23.5 N & <23.5N) andorientation (north,south, east, west, north-east,north-west,south-east&south-west)

3.3 Predetermined OTTV coefficients for Composite, Hot-Dry and Warm-Humid climates

Apart from the national building energy codes developed by the Bureau of Energy Efficiency, the study “Predetermined overall thermal transfer value coefficients for Composite, Hot-Dry and Warm-Humid climates” by Devgan et al. (2010) is the only extensive work that has attempted to develop an OTTV based steady-state algorithm for three Indian climatic zones [4]. The study establishes an OTTV algorithm along with coefficients for Composite, Hot-Dry and Warm-Humid climatic zones. Compared to other OTTV based heat transfer steady-state modelsthealgorithmdevelopedbyDevganetal.(2010)is more complex, as it uses a combination of linear and second-degree polynomial correlation for conduction heat transfers through walls and windows. The algorithm developedforcalculatingOTTVisplacedbelow:

Where,

Un isU-factorofrespectiveenvelopecomponent

α issolarabsorptanceofwallsurface

LSU is solar transmittance coefficient that varies between 30.5 and 52.5 depending upon orientationandclimatezone

SSU is solar transmittance coefficient that varies between -4.45 and -5.75 depending upon climate zone

LGU is solar transmittance coefficient that varies between 10.5 and 15.5 depending upon climate zone

SGU is solar transmittance coefficient that varies between -0.69 and -1.04 depending upon climate zone

SF is solar factor that varies between 92 and 263 dependinguponorientationandclimatezone

SC isshadingcoefficientofwindow

ESM is external shading multiplier that varies depending upon projection factor, orientation, pitchangleofwallsandclimatezone

3.4 Comparison of Steady-state algorithms

There isn't much information available in the public domainontheprecisemethodsemployedbytheBureauof Energy Efficiency while developing the algorithm and computing the coefficients. Discussions with Dr. N. K. Bansal, Chair of the ECBC 2007 committee, and Mr. Saurabh Diddi, Director, BEE provided valuable insights which have been documented in Table 2 and Table 3. The equationsproposedforcalculatingrespectiveperformance indicators(EPFforECBC,RETVforENSandOTTV)forthe mentionedalgorithmshavebeendiscussedinthissection.

The methodologies employed for developing the steadystate thermal performance algorithm and the simulations performedforcomputingthecoefficientsarementionedin Table 3. Unfortunately, extremely limited information is available in the public domain regarding the methodology utilizedfordevelopingbuilding envelopetrade-offmethod fordemonstratingcompliancewithECBC2007[21]

Table 3: Comparisonofenergymodellingandanalysisfor developingalgorithms

1 Limited information available in public domain regarding the methodology utilizedfor computing EPFcoefficients.Discussions withDr.N.K.Bansal,ChairoftheECBC2007committeeprovided thementionedinsights.

2 The author was member of the Working Group on Building Envelopeandcontributedtothedevelopmentprocess.

3 The author was member of the technical committee and contributedtothedevelopmentprocess.

4 Calculatedbyauthorbasedondocumentedmethodology.

3.5 Limitations of Steady-state Heat Transfer algorithms

The lack of reliable information on the methodology used for the computation of EPF coefficients provided in ECBC 2007 makes it difficult to comment on their accuracy and validity in different scenarios. It is noteworthy that even the tables listing these coefficients mention that these values are under review [21, pp. D.2-D.3]. However, the major concern regarding the provided coefficients is the presence of negative values for conduction heat transfer coefficients through windows and skylights. This is most likely a result of the incorrect application of net heat transfer through individual envelope components as the dependent variable. ECBC 2007 also provides separate coefficients for mass wall and curtain walls without definingthemassordensitythresholdforthesecategories. Another notable inaccuracy of ECBC 2007 is that it provides orientation-specific coefficients based on climate zones,whichisaresultofintermixingclimateclassification based on temperature and humidity (NBC) and latitudedependent solar radiation distribution across different orientations. However, for computing shading multipliers for effective SHGC of fenestrations with shading devices

ECBC 2007 uses 15 N latitude to classify India into two separategeographicregions.

The ECBC 2017, employs a component approach for computing EPF coefficients based on prototype models developedfordifferentbuildingtypologies.Thecodelimits the application of ‘Building Envelope Trade-off method’ to buildings having WWR up to 40 percent but doesn’t provide the basis for this limit. It can be assumed thatthe parametric runs performed for computing these coefficients used models with WWR ≤40 percent. The energy simulation and parametric runs were performed using eQuest v.3.64 [24]. Similar to ECBC 2007, the EPF coefficientshavebeenprovidedfortwogroupsofbuilding operations-daytimeand24-houroccupancies.Theskylight has not been included in the trade-off analysis, due to its limited occurrence observed in data collected for developing prototype models. Similar to ECBC 2007, the orientation-specificcoefficientsprovidedinECBC2017are once again a result of the intermixing of climate classification based on temperature and humidity (NBC) and latitude-dependent solar radiation distribution across differentorientations.The15N latitudehasbeenusedfor classifyingIndiaintotwoseparategeographicalregionsfor computingshadingequivalentfactors[22]

TheEco-NiwasSamhita2018(Part-1)providescoefficients to calculate the Residential Envelope Transmittance Value (RETV) of buildings located in four climate zones (except for cold zone) of India. It has merged the Hot-Dry and Compositezonesduetosimilarweatherconditionsduring the observed cooling period between March and October [25]. The coefficients for RETV were computed through simulation models created using DesignBuilder with EnergyPlus solver. The methodology is based on the averageofmultiplerepresentativecities,whichmeansthat the computed coefficients are an average of the selected representative cities. However, it isimportant to notethat unlike ECBC the roof of the building is not included in the RETV algorithm. Two separate prototype layouts were used for performing the parametric simulations and the orientation factor was calculated by considering the amount of solar radiation incident on eight façades of an octagonal building during the simulated cooling period [25]. Ideally, the amount of solar radiation transmitted through the eight façades ofthe octagonal building should bereferredtoinsteadoftheamountincident.Fortunately, the ECBC’s inaccuracy of intermixing climate zones with orientation specific coefficients has not been replicated in ENS 2018. The orientation factor is independent of the climate zone, but the same orientation factors are applied for both conductive and radiative heat gain components which can’t be the accurate representation based on buildingphysicsprinciples.Boththeorientationfactorand shadingmultiplierhavebeencomputedbasedonthe23.5° N latitude for classifying India into two separate geographic regions [19]. It is also important to note that

since the simulation for developing the RETV algorithm wascarriedoutonlyfortherespectivecoolingperiods,the envelope specifications selected based on this algorithm maynotnecessarilybeoptimizedforthebuilding'sannual operation.

The study titled “Predetermined overall thermal transfer value coefficients for Composite, Hot-Dry and WarmHumid climates” by S. Devgan et al. (2010) was also an attempt at addressing the limitations and errors of ECBC 2007.ItdevelopedOTTVbasedalgorithmforthreeclimate zones- Hot-Dry, Warm-Humid and Composite. The development of the prototype building model for the simulation and parametric runs is based on a limited dataset of four air-conditioned office buildings located in Delhi NCR. Therefore, the developed prototype building modelmaynotberepresentativeofotherregionsofIndia. The study used eQuest v.3.6 for building energy simulations, and was limited to a single 16-story office buildinghavinganoctagonalplanforparametricruns.The study performed calculations for the exterior shading multiplier for windows and then proceeds to apply it to shaded walls as well. Considering the different nature of heat transmission (conductive for opaque assemblies and radiative in the case of non-opaque assemblies) the application of the same exterior shading multipliers is bound to generate inaccurate results. Additionally, the orientationfactorsandshadingmultiplierswerecomputed for 8 orientations (N, S, E, W, NE, NW, SE & SW) by performing parametric runs, and the coefficients for inbetween 8 orientations (NNE, ENE, ESE, SSE, SSW, WSW, WNW & NNW) was derived via interpolation. The study considered 98 types of exterior wall constructions and 93 types of glass constructions were evaluated for each climate type. Regression analysis was performed to develop a new OTTV equation and computation of coefficients for the three climate zones. The ECBC’s erroneous method of developing orientation-specific coefficients based on climate zones has been followed in this study as well. This is a result of flawed intermixingof climate classification based on temperature and humidity and latitude-dependent solar radiation distribution across different orientations.The developed OTTValgorithm was validated by calculating OTTV for the four reference case study buildings, and the results exhibited a good linear correlation with the annual air-conditioning energy use in thethreeclimates.

Thelatitudeofthecitywheretheprojectislocatedplaysa significant role in determining the amount of solar radiation that is incident on the façade of the building facing different orientations. For example, the buildings that are located closer to the equator will receive uniform solar radiation on the north and south façades of the building, whereas buildings located farther from the equatorshallreceivesignificantlyhighersolarradiationon the façade oriented towards the equator. Therefore, the shading devices shall be optimized based on the

orientation of the building façade and considering the variations in solar path with changes in the latitude of projectlocation.However,theabove-developedalgorithms (except RETV of ENS 2018) have applied NBC climate classification for computing orientation specific factors insteadoflatitudebasedgeographicalclassification.

The OTTV approach is based on steady-state heattransfer calculations, that does not accurately represent the dynamic thermal behaviour of buildings. This can lead to oversimplification of building envelope performance and does not account for the impact of variations in internal loads and operation schedules on building energy consumption. Despitetheintrinsic limitations of the OTTV approach it is a useful tool for evaluating the thermal performanceofbuildingenvelopesatanearlydesignstage, where the application of advanced building energy simulation tools may not be viable. However, the OTTV approach requires accurate coefficients for the building envelope components, which are specific to the climate zones of India. The lack of accurate coefficients for the building envelope components for the cooling-dominated climate zones of India is a major limitation of the OTTV approach. This research shall build upon the previous worksandattempttoaddressthegapswhiledevelopinga building physics based steady-state algorithm to quantify the overall thermal performance of the building envelope forcooling-dominatedIndianclimates.

4 CONCLUSION

The design of the building envelope significantly impacts the thermal performance and overall energy efficiency of thebuilding.Buildingenvelopeoptimizationhasbecomea critical aspect of the design process, with the aim of reducing energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and ensuring thermal comfort for the occupants. The optimization of the building envelope can be achieved throughacombinationofpassiveandactivemeasures.The optimization of passive measures involves appropriate selection of parameters such as building orientation, shading, glazing, and insulation. The selection of the appropriatemeasuresandtheirimplementationrequiresa comprehensive understanding of building physics, climate classification,andthermalcomfortstandards.Thebuilding envelopeoptimizationprocessalsoinvolvestheintegration of building energy codes and standards, which provide a frameworkforthedesignofthermallycomfortableenergyefficient buildings. The implementation of building energy codes and standards in India is still in the nascent stage. However, with the increasing demand for energy-efficient buildings, there is a growing need for building envelope optimizationandtheadoptionofperformance-basedcodes andstandards.

ThispaperidentifiedOverallThermalTransmittanceValue (OTTV) as an effective tool not only for building envelope optimization, but also to demonstrate compliance with

buildingenergycodes.ThedevelopmentofanOTTVbased algorithm for the thermal performance optimization of building envelopes in India can be a significant step towards mainstreaming climate-responsive design of commercial buildings. This paper reviewed different algorithmsusedtoquantifythermalperformance,itsusein nationalbuildingenergycodes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author would like to acknowledge the support provided by the buildings team at Bureau of Energy Efficiency(BEE)undertheleadershipofMr.SaurabhDiddi. The author would like to thank Prof. N. K. Bansal for providing valuable information on the development of EnergyConservationBuildingCode(ECBC)ofIndia

This study is a part of author’s ongoing research work at Department of Architecture, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi,India.

REFERENCES

[1] M. S. Bhandari and N. K. Bansal, "Solar heat gain factors and heat loss coefficients for passive heating concepts," Solar Energy, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 199-208, 1994.

[2] ASHRAE, Standard 90-1975 Energy Conservation in New Building Design, American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE),1975.

[3] ASHRAE,Standard90A-1980:EnergyConservationin New Building Design, American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE),1980.

[4] S. Devgan, A Jain and B Bhattacharjee, "Predetermined overall thermal transfer value coefficientsforComposite,Hot-DryandWarm-Humid climates," Energy and Buildings, vol 42, no 2010, pp 1841-1861,2010

[5] K. Chua and S Chou, "Energy performance of residentialbuildingsinSingapore," Energy, vol 35,no 2010,p.667

678,2009.

[6] S. C M Hui, "Overall thermal transfer value (OTTV): How to improve its control in Hong Kong," in Proceedings of the One-day Symposium on Building, Energy and Environment,Kowloon,HongKong,1997.

[7] R. Rawal, D. Kumar, H. Pandya and K. Airan, "Residential Characterization," Centre for Advance

Research in Building Science & Energy, CEPT University,Ahmedabad,2018.

[8] W.K.ChowandK.T.Chan,"Parameterizationstudyof the overall thermal-transfer value equation for buildings," Applied Energy, vol.50,no.3,pp.247-268, 1995.

[9] J. Vijayalaxmi, "Concept of Overall Thermal Transfer Value (OTTV) in Design of Building Envelope to Achieve Energy Efficiency," International Journal of Thermal and Environmental Engineering, vol. 1, no. 2, pp.75-80,2010.

[10] BCA, Guidelines on Envelope thermal transfer value for buildings, Building and Construction Authority, Singapore(BCA),2004.

[11] BCA,CODEONENVELOPETHERMALPERFORMANCE FORBUILDINGS,BuildingandConstructionAuthority, Singapore(BCA),2008.

[12] Malaysian Standards, MS 1525:2007 Code of Practice onEnergyEfficiencyandUseofRenewableEnergyfor Non-Residential Buildings, Department of Standards Malaysia,2007.

[13] BuildingsDepartment-HK,CodeofPracticeforOverall Thermal Transfer Value in Buildings, Buildings Department,HongKong,1995.

[14] Buildings Department-HK, Energy Efficiency of Buildings: Building (Energy Efficiency) Regulation, BuildingsDepartment,HongKong,2019.

[15] Ministry of Housing & Works, Pakistan, Building Energy Code of Pakistan, Ministry of Housing & Works,GovernmentofPakistan,1990.

[16] SLSEA, Code of practice for energy efficient buildings in Sri Lanka, Colombo: Sri Lanka Sustainable Energy Authority(SLSEA),2009.

[17] Jamaica Bureau of Standards, JS 217:1994 Jamaica National Building Code- Volume 2: Energy Efficiency Building Code, Requirements and Guidelines, Jamaica BureauofStandards,1994.

[18] ASHRAE,Standard90.1-1989:EnergyEfficientDesign of New Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings, American Society of Heating, Refrigerating andAir-ConditioningEngineers,1989.

[19] BEE, Eco-Niwas Samhita 2018 Part I: Building Envelope, New Delhi: Bureau of Energy Efficiency, GovernmentofIndia,2018.

[20]M Cook,Y Shukla,R Rawal,D.Loveday,L C d.Faria and C Angelopoulos, Low Energy Cooling and Ventilation for Indian Residences: Design Guide, LoughboroughUniversity,UKandCEPTResearchand DevelopmentFoundation(CRDF),India,2020.

[21]BEE, Energy Conservation Building Code 2007, New Delhi: Bureau of Energy Efficiency, Government of India,2007.

[22]BEE, Energy Conservation Building Code 2017 (with Amendments upto 2020), New Delhi: Bureau of EnergyEfficiency,GovernmentofIndia,2017a

[23]BEE, Energy Conservation Building Code User Guide, New Delhi: Bureau of Energy Efficiency, Government ofIndia,2011

[24]G. Somani and M. Bhatnagar, "Stringency Analysis of BuildingEnvelopeEnergyConservationMeasuresin5 Climatic Zones of India," in Proceedings of BS2015: 14th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association,Hyderabad,2015.

[25]P. K. Bhanware, P. Jaboyedoff, S. Maithel, A. Lall, S. Chetia, V. P. Kapoor, S. Rana, S. Mohan, S. Diddi, A. N. Siddiqui, A. Singh and A. Shukla, "Development of RETV (Residential Envelope Transmittance Value) Formula for Cooling Dominated Climates of India for the Eco-Niwas Samhita 2018," in Proceedings of Building Simulation 2019: 16th Conference of IBPSA, Rome,Italy,,2019

BIOGRAPHIES

Abdullah Nisar Siddiqui isa registered architect with the Council of Architecture (COA), India and ECBC Master Trainercertifiedby the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), Govt. of India He has extensive experience in developing building energy policies, standards, and rating systems for India He has served on technical committees and working groups for Energy Conservation Building Code 2017, Eco-Niwas Samhita (Part-1 & 2) and has supported multiple states in developing their Energy Conservation BuildingCodes.