Emilia

Assistant Supervisor Production Bible

Fay Wilde

-5. Contact Sheet

6 -11. Cast List

12 – 16. Fitting Schedules

17 - 18. Tech Schedule

19 – 25. Script Breakdown

26. Primary Research

27 -28. Fabric Identification

29 -33. National Portrait Gallery

34 -35. Othello

36. Secondary Research

37 – 40. Womenswear from 1590 - 1610

41. Dyes from 1590 - 1610

42 -43. Midwives During the 17th Century

44. Characters

45 – 67. Amber Tormey

68 – 88 Evie Prasse

89 – 110. Lottie Surman

111 – 128 Sarah Astbury

129 – 148. Yasemin Koc

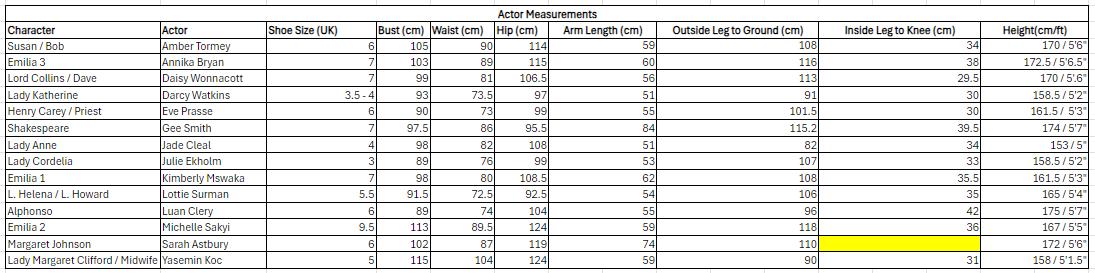

149 – 150. Measurement Cheat Sheet

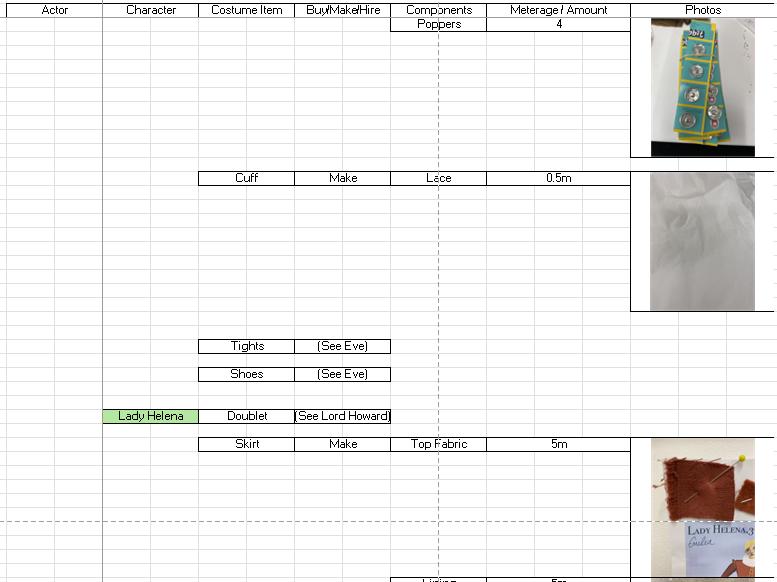

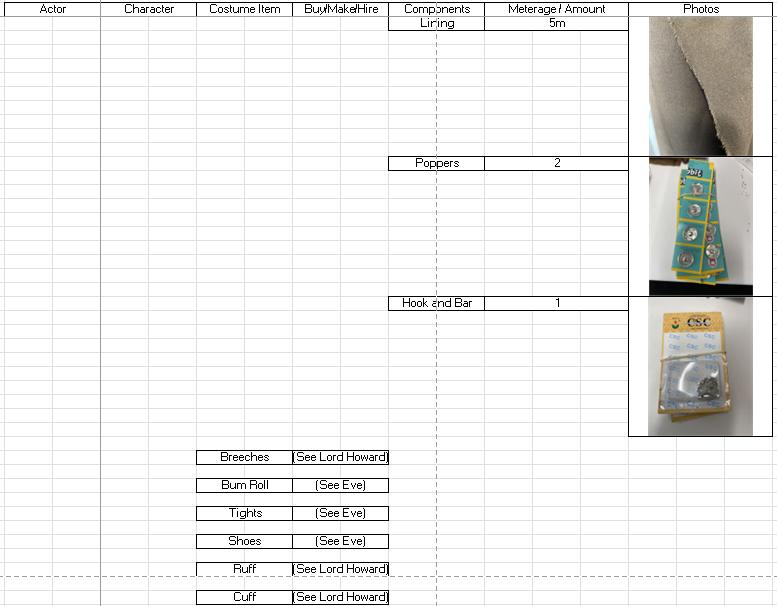

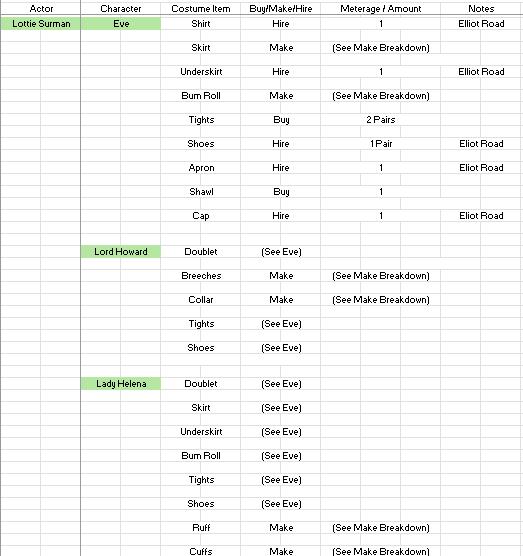

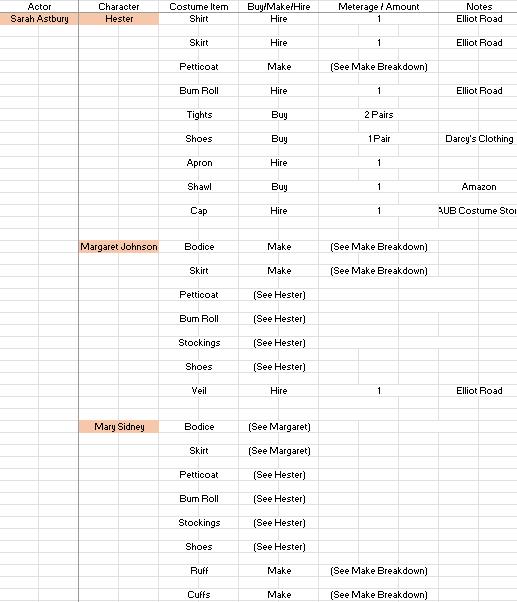

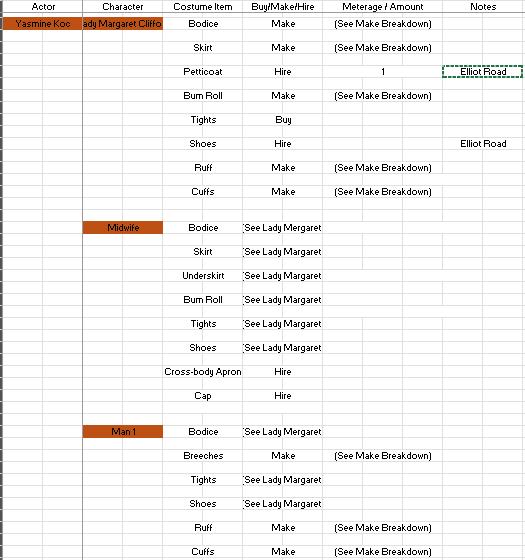

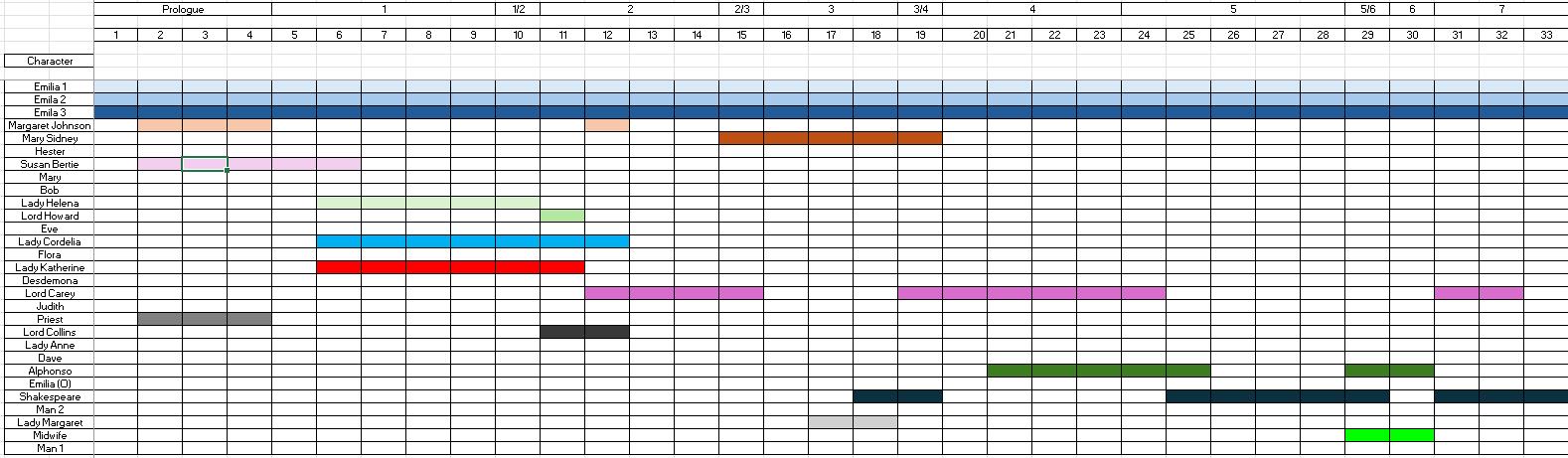

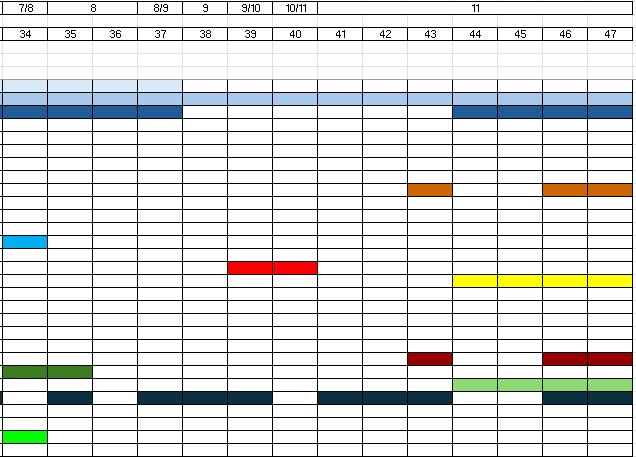

151 – 153. Costume Plot

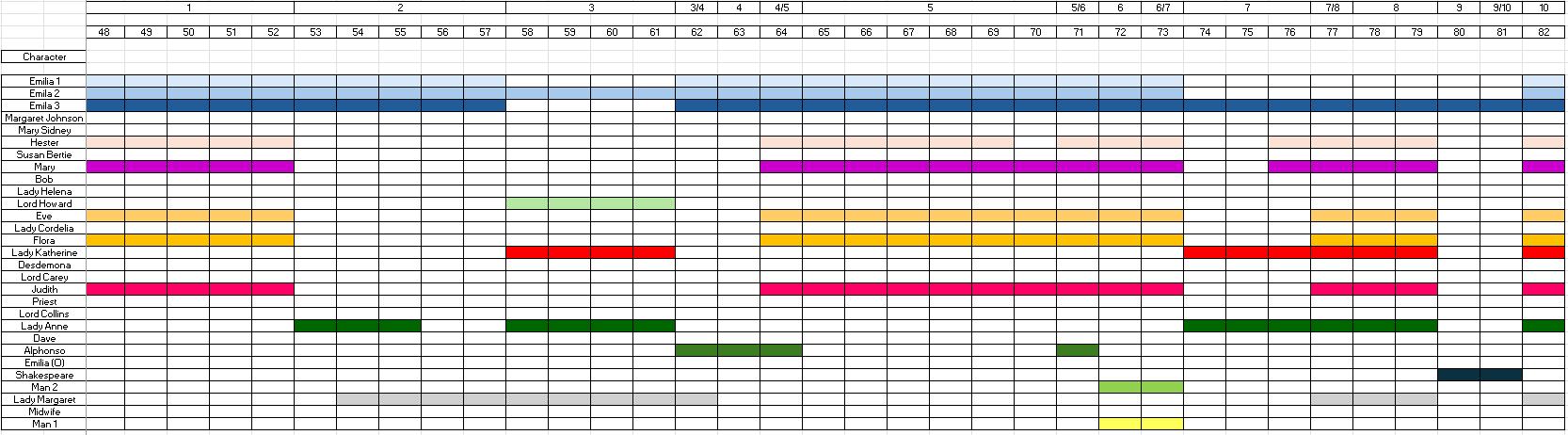

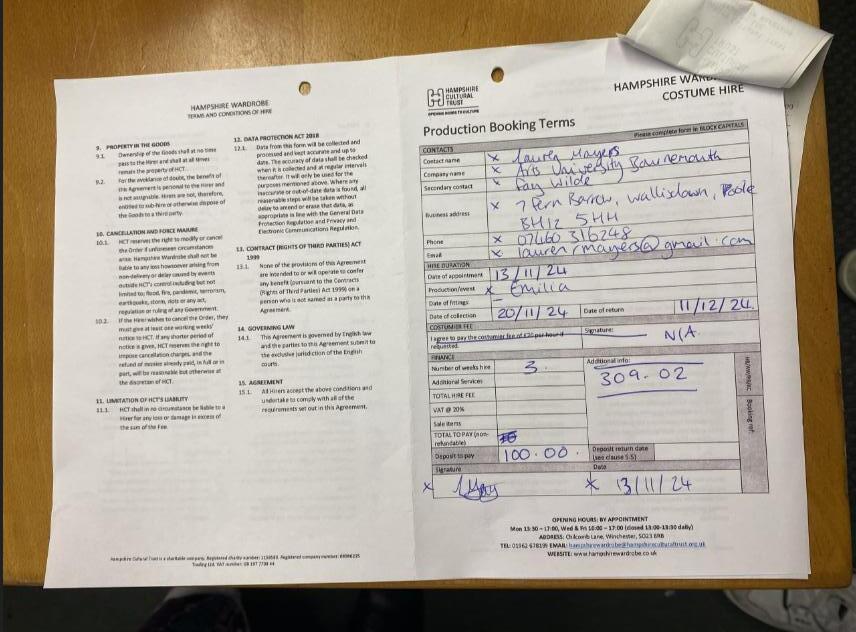

154 – 155. Hire Forms

156 – 158. Bibliography

159 – 161. Fig List 162. Appendix 163. CPD 164 Laundry

165. Rehearsal and Tech Notes

Contact Sheet

Role Name Pronouns Email Receive Reports? STAFF & FREELANCERS

ACTING

Production Manager Ben Goodridge bgoodridge@aub.ac.uk Y

Production Officer

Technical Manager Scott Eveleigh seveleigh@aub.ac.uk Y

Lighting Designer Dan Parker He/Him dparker@aub.ac.uk Y

Production Technician Shae Carroll scarroll@aub.ac.uk Y

Company Stage Manager Brianna Barwell bbarwell@aub.ac.uk Y

Production Photographer Andy Beeson – Red Manhatten Photography

COSTUME & DESIGN

Design Tutor Will Hargreaves whargreaves@aub.ac.uk Y

Scenic Design Coordinator Alex White awhite@aub.ac.uk Y

Costume Academic Jen Ridge jridge@aub.ac.uk Y

Making Tutor Katerina Lawton Klawton@aub.ac.uk

Senior Technician Alison Hart ahart@aub.ac.uk Y

Costume/ DCP Technician Erin Batten ebatten@aub.ac.uk Y

MAKE UP

Academic Supervisor

Gaby Main Gmain@aub.ac.uk

Senior Technician Sophie Monro smonro@aub.ac.uk Y

Technical Supervisor

STUDENTS

ACTING

Stage Manager Esther Kalala 2204489@my.aub.ac.uk Y

Deputy Stage Manager Bri Barwell (staff) Bbarwell@aub.ac.uk Y

Acting Assistant Stage Manager Jade Cleal 2203728@my.aub.ac.uk Y

Acting Assistant Stage Manager Daisy Fairy She/They 2207652@my.aub.ac.uk Y

Acting Assistant Stage Manager Gee Smith 2102266@my.aub.ac.uk Y

Assistant Director Will Rosander 2205019@my.aub.ac.uk Y

Publicity / FOH

Ethan Clark

Publicity / FOH Fleur Manning

Publicity / FOH Harry Bell

Publicity / FOH Oscar Vas

Bar Manager Dan Hancock

Sound Assistant Peter Graham He/they 2206642@my.aub.ac.uk

Lighting Assistant Lou Edwards 2203748@my.aub.ac.uk

COSTUME & DESIGN

Scenic

Props Supervisor Molly Barber

Breakdown Artists Megan Daniels

Costume Makers (making for......)

Helena Tuff (Lord Henry Carey, Priest)

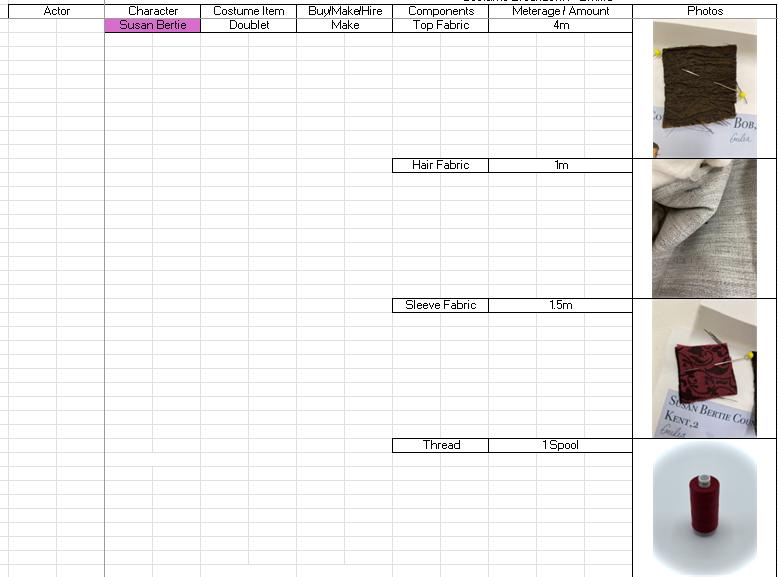

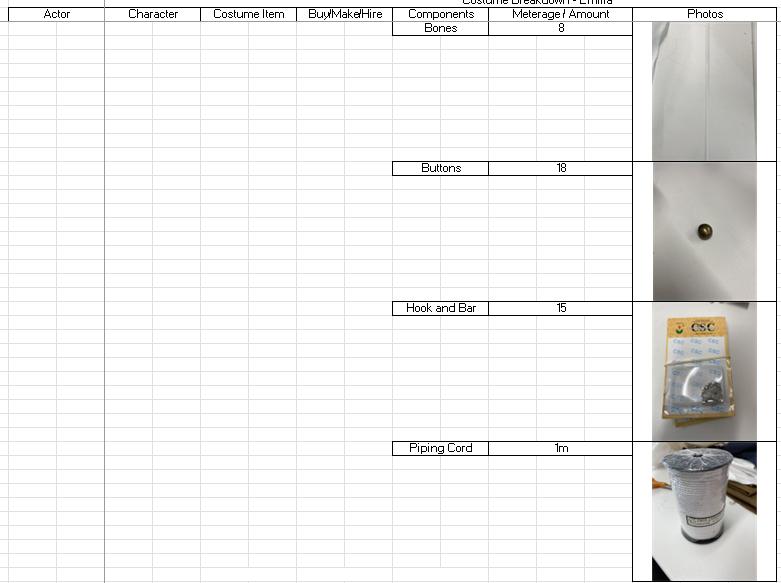

Amber Thornton (Susan Bertie, Bob)

Sam Kitton (Emilia3)

Jess Davies (Mary Sidney, Margaret Johnsons)

Jessica Little (Margaret Clifford, Man 1, Midwife)

Issy Crouch (Lady Cordelia)

Dressers

Costume Assistants

Scenic Artists

Make Up Supervisor and Designer

Make Up Assistants

Emilia 1

Sophie Sheard (Alphonso, Eve)

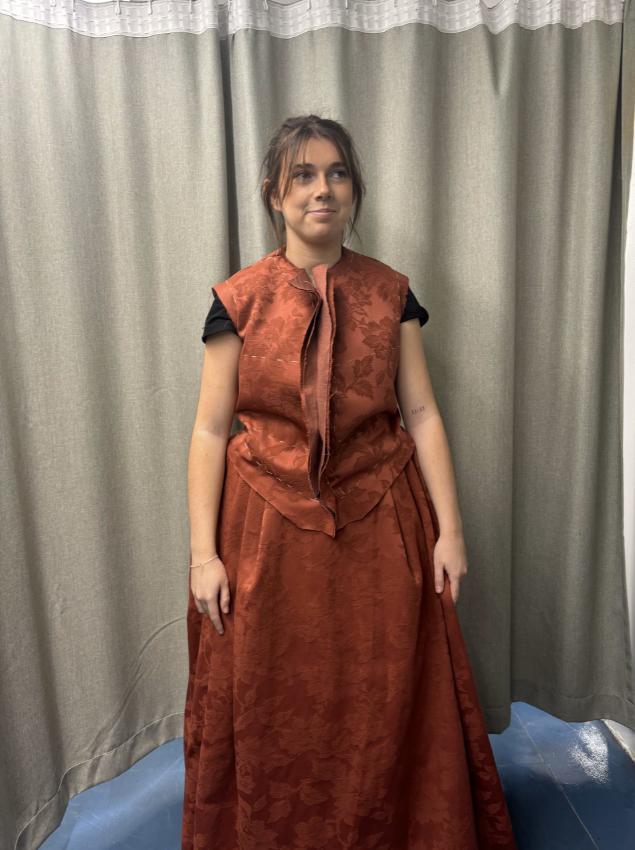

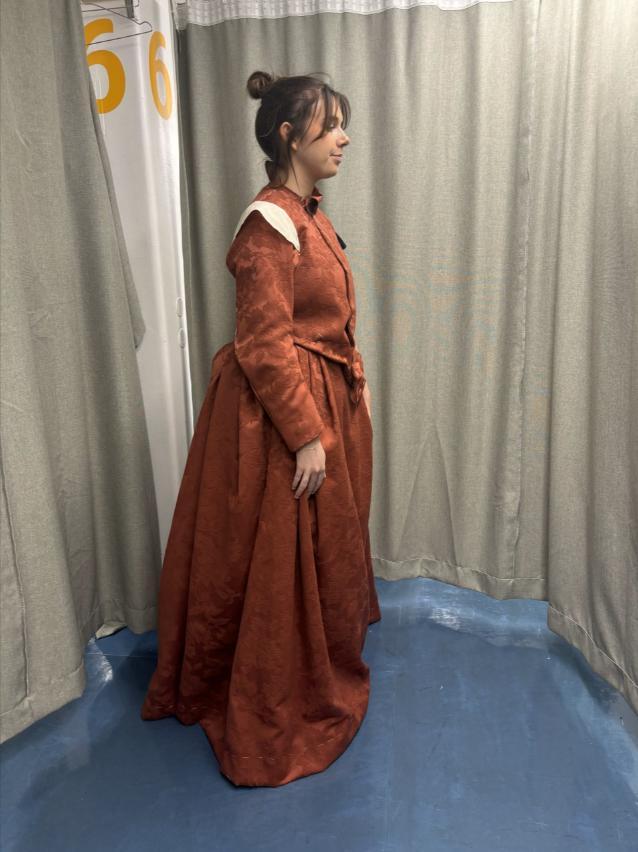

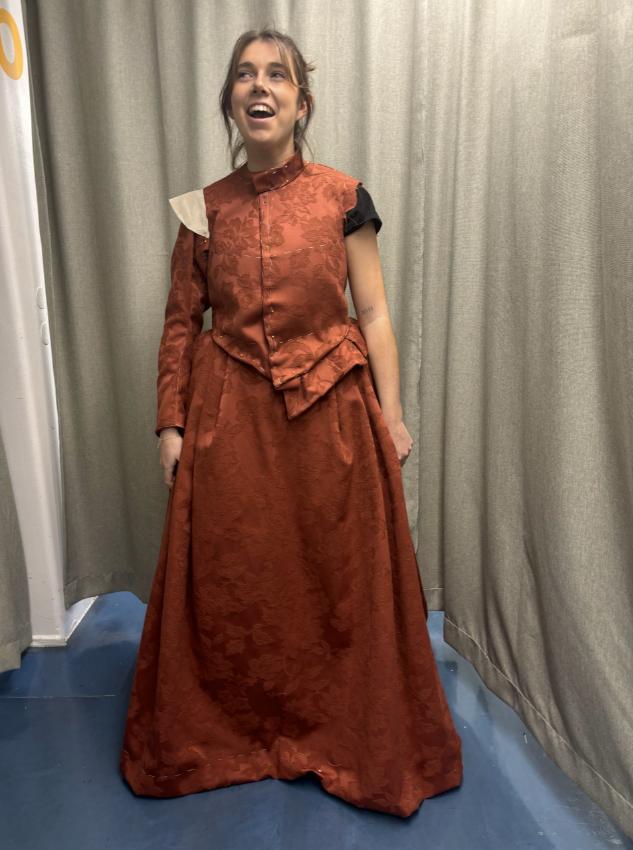

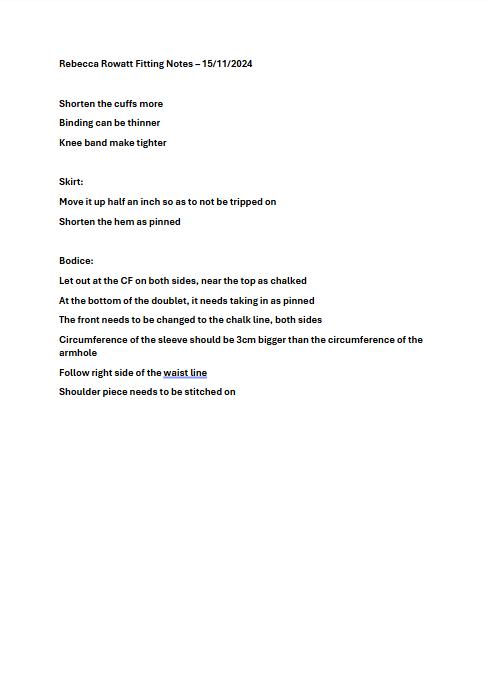

Rebecca Rowatt (Lady Helena, Lord Howard)

Anya Cheesborough (Emilia2)

Lily Stratford (Shakespeare, Desdemona)

Elanor Parkinson (Lady Katherine)

Megan Caley (Emilia1)

Megan Parker (Midwife Apron)

Sam Kitton Helena Tuff Amber Thornton They/them she/her she/her

MAKE UP

Lydia Harris

Mary Aniseh, Karolina Biskup, Hannah Cheeseman, Sofia Cooper, Ffion Davies, Amy Donnelly, Harmony Evans, Louis Loc, Khushi Mehta, Shantaye Miles, Mallika O’Brien CAST

2204266@my.aub.ac.uk Y

Kimberly Mswaka N

Emilia 2

Emilia 3

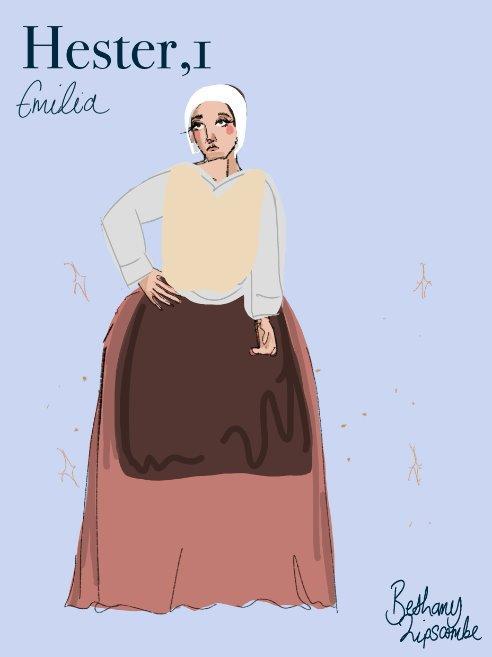

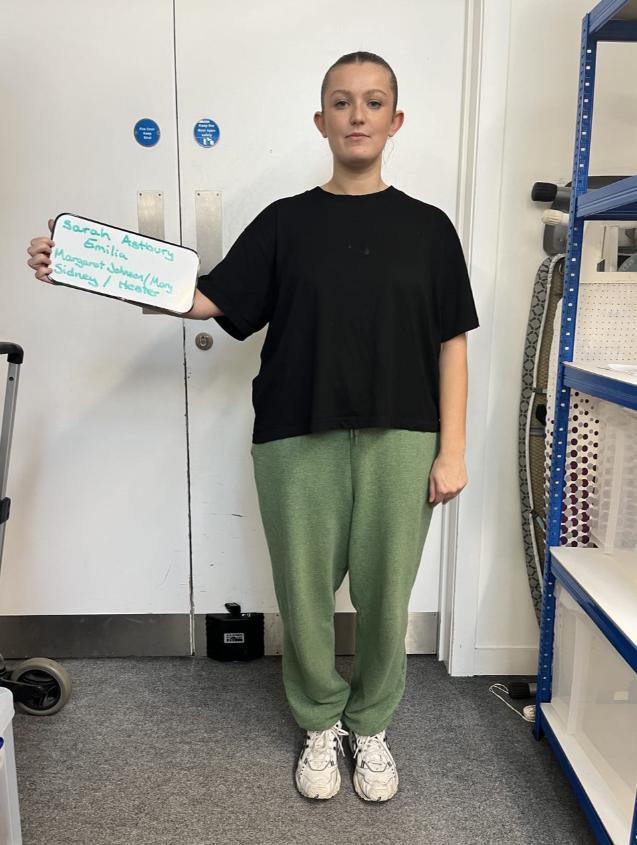

Margaret Johnson / Mary Sidney / Hester

Susan Bertie / Mary / Bob

Lady Helena / Lord Howard / Eve

Lady Cordelia / Flora

Lady Katherine / Desdemona (In Othello)

Michelle Sakyi

Annika Bryan

Sarah Astbury

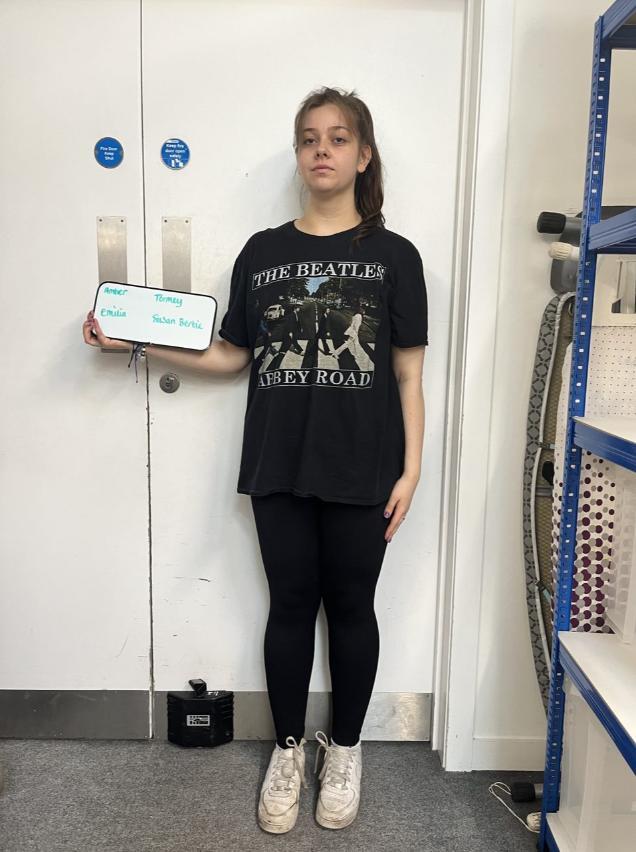

Amber Tormey 2202311@my.aub.ac.uk

Lottie Surman

Julie Ekholm she/her 2202953@my.aub.ac.uk

Darcy Watkins 2200809@my.aub.ac.uk

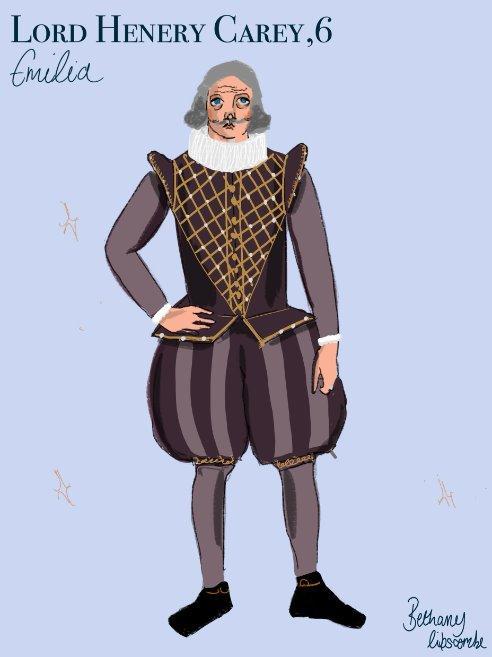

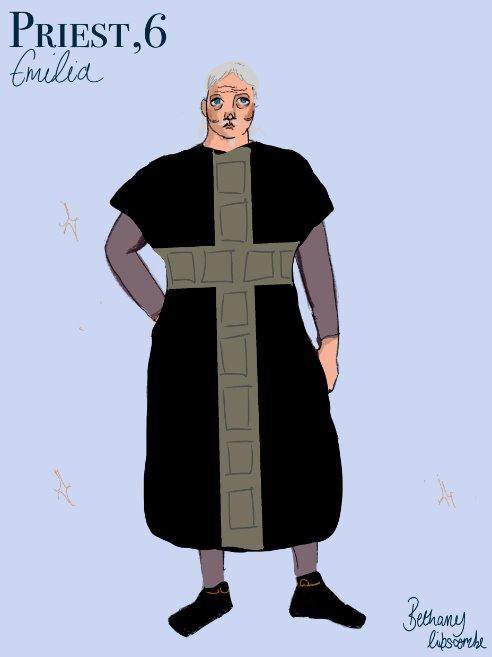

Lord Henry Carey / Judith / Priest Evie Prasse

Lord Collins / Dave

Lord Alphonso Lanier / Emilia (in Othello)

Daisy Fairy She/they 2207652@my.aub.ac.uk

Luan Clery

William Shakespeare / Man 2 Gee Smith

Lady Margaret Cliford / Midwife / Man 1

Yasmine Koc she/her 2006125@my.aub.ac.uk

Lady Anne Jade Cleal

Cast List

Emilia 1

Kimberly Mswaka

Emilia 2

Michelle Sakyi

Emilia 3

Annika Bryan

Margaret Johnson / Mary Sidney / Hester

Sarah Astbury

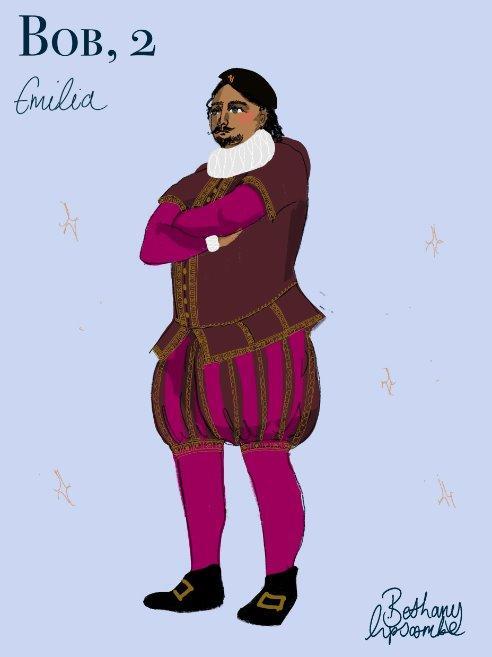

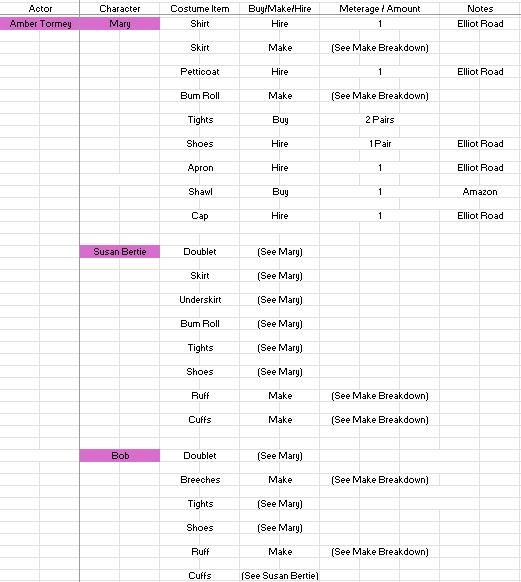

Susan Bertie / Mary / Bob

Amber Tormey

Lady Helena / Lord Howard / Eve

Lottie Surman

Lady Cordelia / Flora

Julie Ekholm

Lady Katherine / Desdemona (Othello)

Darcy Watkins

Lord Henry Carey / Judith / Priest

Evie Prasse

Lord Collins / Dave Daisy Wonnacott (Acting ASM)

Lord Alphonso / Emilia (Othello)

Luan Clery

William Shakespeare / Man 2 Gee Smith (Acting ASM)

Lady Margaret Clifford / Midwife / Man 1

Yasemin Koc

Lady Anne Jade Cleal (Acting ASM)

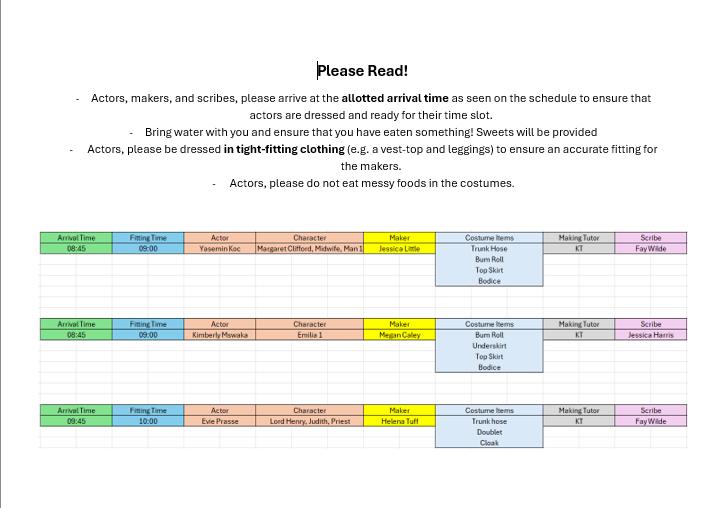

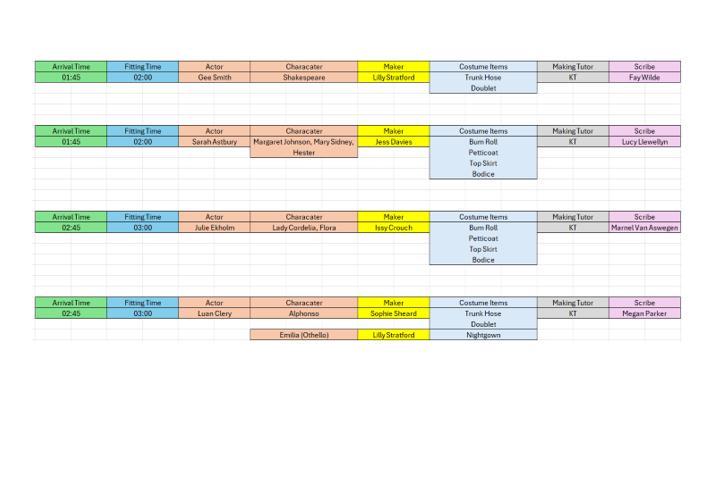

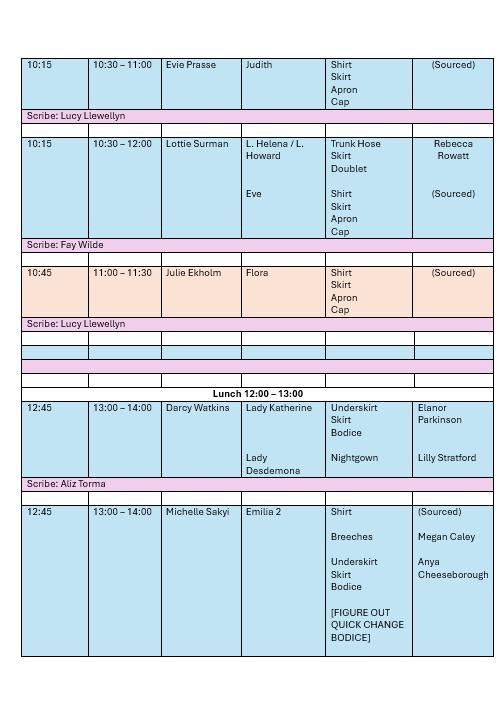

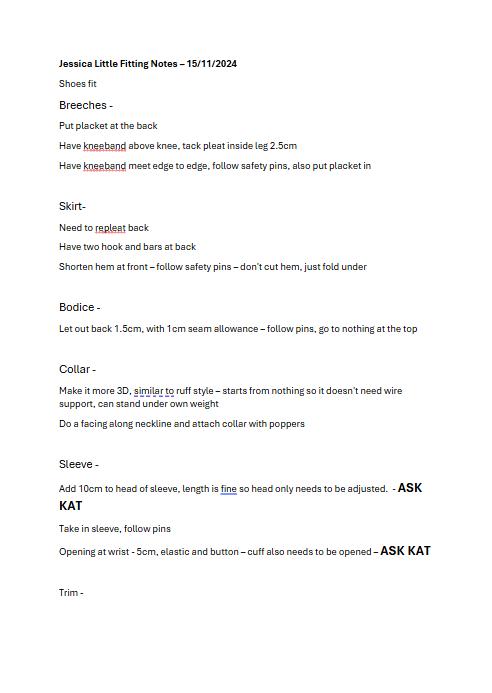

Fitting Schedules

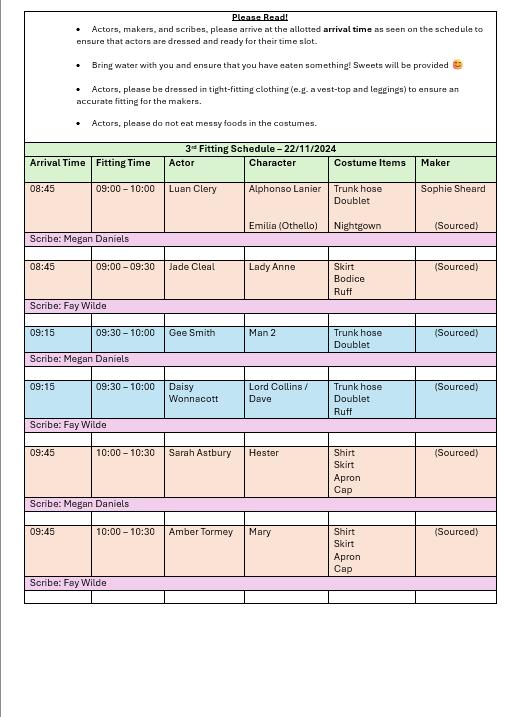

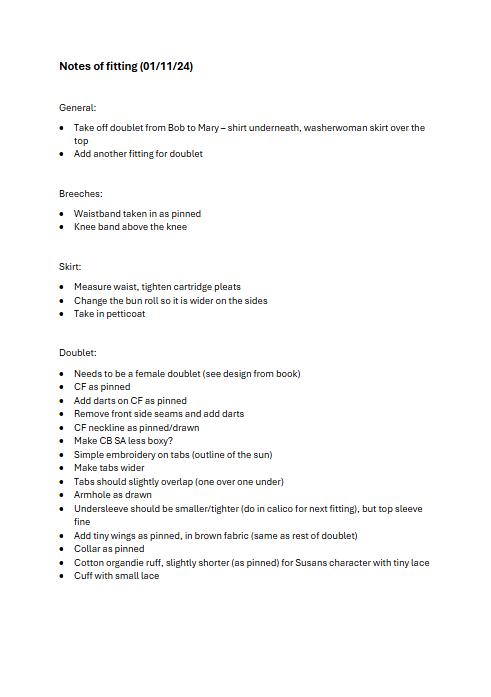

3rd Fitting – 22.11.24

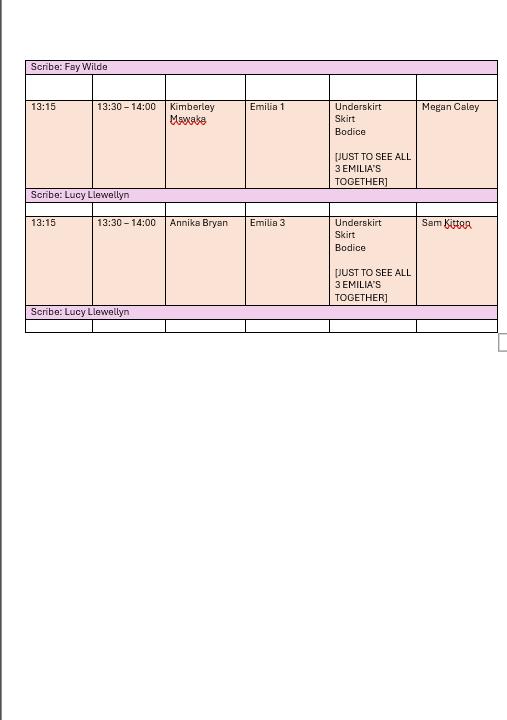

Tech Week Schedule

Script Breakdown

Prologue

Auditorium Internal

1 1 Susan Bertie’s House

2 Susan Bertie’s House

Internal

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Margaret Johnson, Priest, Susan Bertie Countess of Kent

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Susan Bertie, Lady Helena, Lady Katherine, Lady Cordelia, Male Ensemble

Internal Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Lady Katherine, Lady Cordelia, Lord Howard, Lord Collins, Margaret Johnson, Lord Carey, Male Ensemble

3 Wilton House Interior

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Mary Sidney, Lady Margaret Clifford, William Shakespeare

Emilia 3 introduces the play. The scene transitions into the funeral of Emilia’s father. Emilia is then placed with Susan Bertie, against her will.

Emilia 1 is introduced to Lady Helena, Lady Katherine, and Lady Cordelia. They are taught the ways of court life and are introduced to men.

The court happens. Lady Katherine and Lady Cordelia are taken offstage by Lord Howard and Lord Collins. Time passes and Margaret Johnsons dies. Emilia 1 meets Lord Henry, and she becomes his mistress

Emilia 1 goes to Mary Sidney’s house. They talk about poetry. Lady Margaret Clifford shows up and offers Emilia 1 a job tutoring her daughter, Emilia 1 declines. Emilia 1 is also introduced to William Shakespeare

Emilia hangs off Margaret’s skirt

Lady Cordelia lifts skirts and adjusts underclothes

Susan Bertie drops a handkerchief

Emilia 3 comes onto stage with a copy of ‘Sex and Society in Shakespeare’s Age – Simon Foreman The Astrologer’ by AL Rowse

Emilia 1 walks around with a book on her head

Lord Henry passes Emilia 1 a note

4 Lord Carey’s House Interior

5 The Wedding

6

7

8

9

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Lord Carey, Lord Alphonso, Handmaids (?)

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Lord Carey, Alphonso, Shakespeare, Male Ensemble

Emilia 1 reveals she is pregnant to Lord Carey. He has her married to Lord Alphonso Email 1 is dressed in a wedding dress

Emilia 1 is pregnant in this scene

Emilia 1 and Alphonso are married. Alphonso leaves and Emilia 1 and Shakespeare flirt. At the end of this scene Emilia 1 goes into labour

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3 Midwife, Alphonso, Emilia 1 gives birth, she names her son Henry. Alphonso goes off to war

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Shakespeare, Lord Carey, Midwife, Lady Cordelia,

Emilia 1 and Shakespeare continue to flirt. The Lord Chamberlain’s Men is founded. Emilia becomes pregnant with Shakespeare’s baby. Lord Carey dies. Emilia goes into labour.

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Alphonso, Shakespeare, Ensemble Emilia 1 argues with Shakespeare about him using her words and he leaves. Emilia’s baby dies. Emilia 1 is replaced by Emilia 2

Emilia 2, Shakespeare Emilia 2 and Shakespeare argue, and Emilia 2 sends him away.

Emilia1 is dressed in a wedding dress

Emilia 1 is pregnant in this scene

Lord Alphonzo carries a recorder

Alphonso preens in a mirror

Male Ensemble raise glasses

Shakespeare gives Emilia a rose

Emilia 1 holds a baby

Emilia is put into pregnancy bump

Emilia 1 and midwife hold baby

Shakespeare holds a quill and pen

Emilia 1, 2, and 3 hold baby

Emilia 1 holds notepad

10

Emilia 2, Lady Katherine, Lady Katherine tries to convince Emilia 2 to be “sensible”, Emilia 2 refuses

11 The Globe Interior Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Ensemble, Shakespeare, Bob, Dave, Lady Desdemona, Emilia (Othello),

2 1 Bankside to Bath House

Exterior to Interior

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Hester, Judith, Eve, Mary, Flora, Female Ensemble, Lady Margaret Clifford, Lady Anne Clifford

Emilia 2 visits the Globe and finds that Shakespeare has been using her words in his play, Othello, she rushes the stage, and gets the play cut off

Emilia 2 wanders Bankside after getting kicked out from the Globe. She spots a seed pod in the ocean and goes to get it. The washerwomen nearby think she is trying to drown herself. They drag her out, dry her off and get her some dry clothes. They convince her to go stay with some friends.

Emilia 2 is stripped of her old clothes –Bodice, skirt, underskirt, corset, and is dressed in some old clothes. She leaves in these old clothes, however, in the next scene is fully dressed again.

2 Lady Margaret’s House

Interior Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Lady Anne, Lady Margaret

Emilia 2 has been welcomed into Lady Margaret’s home and is a tutor to Lady Anne. Lady Margaret and Emilia 2 talk about Lady Margaret’s husband and how he had mistresses. Lady Margaret convinces Emilia 2 to

When Emilia 2 enters this scene, she is redressed after her disrobing in the scene prior Lady Anne reads from ‘Metamorphosis’ by Ovid

3 Lady Margaret’s house Interior Emilia 2, Lord Howard, Lady Katherine, Lady Margaret, Lady Anne,

4 Emilia’s home Interior Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Alphonso

write warnings about men.

Lord Howard comes over to Lady Margaret’s house upset about Emilia’s poetry. Lady Margaret and Lord Howard argue. Lord Howard leaves after threatening the women with the charge of witchcraft

Alphonso has spent the couple’s money and the two talk about how they will earn back more. Emilia 2 tells him she’s going to teach the washerwomen across the bridge. Alphonso is outraged.

5 Emilia’s home Interior Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Mary, Judith, Flora, Eve, Hester,

Emilia 2 has been teaching the women whilst also writing her own poetry. The men still don’t agree with it. Eve reads a poem she wrote herself. Emilia 2 finds out Shakespeare released the sonnets written about her

6 Outside Emilia’s home Exterior Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Alphonso, Mary, Judith, Eve,

Alphonso and Emilia 2 talk about how they were born in the wrong time. Alphonso then commits

Lord Howard reads from Emilia’s poem

Eve reads a poem

Flora hands

Emilia 2 a book of sonnets

7

8 Emilia’s Scriptorium

9

Flora, Hester, Man 1, Man 2,

Emilia 3, Eve, Lady Katherine, Lady Anne, Flora, Hester, Mary, Judith

suicide. The washerwomen go to Emilia 2, telling her of the suicide and offering sympathies. The women are then approached by two men who harass them. Emilia 2 then attacks the men. Emilia 2 is then replaced by Emilia 3

Lady Katherine goes to Emilia 3, convincing her to continue writing her poems. Email 3 and the washerwomen decide to hide the poems in religious text and decide to write and copy out pamphlets on a mass scale

Emilia 3, Eve, Flora, Hester, Mary, Judith, Lady Katherine, Female Ensemble

The women begin to make pamphlets on mas and the women begin to hand them out. Eve reads out her poem and it’s put on the back of the pamphlet. Eve leaves, is tried for witchcraft and is burnt at the stake

Emilia 3, Shakespeare, Shakespeare appears before Emilia 3 and they talk about the impact their work Emilia curtsies

Lady Katherine is bruised and bloody in this scene

The women pass out pamphlets

Eve hands a poem to Emilia 3 Eve is burnt on the stake, and “goes up in flames”

10

Emilia 1, Emilia 2, Emilia 3, Female Ensemble

made onto people

Emilia 3 adresses the audience one last time. The play ends and there is a dance, presumably amongst the female characters

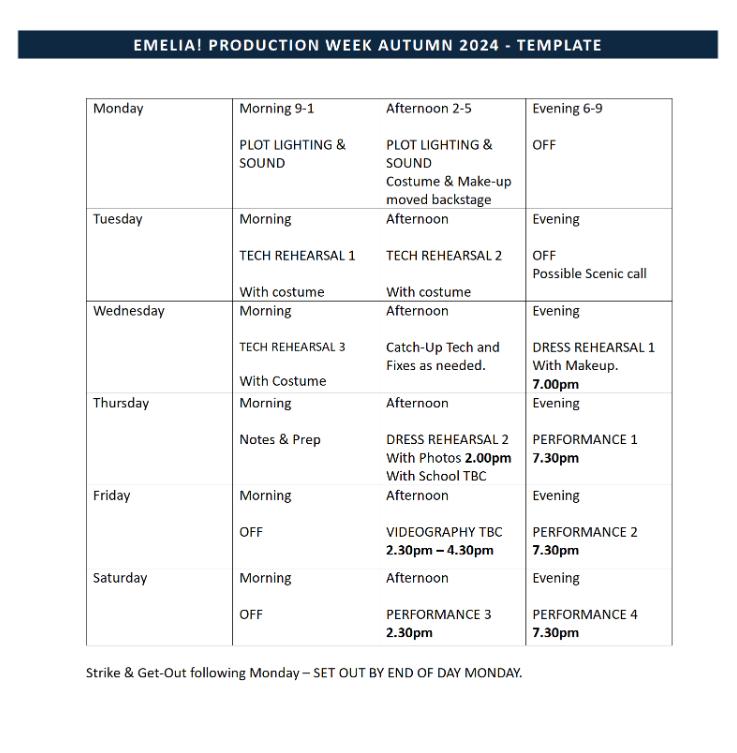

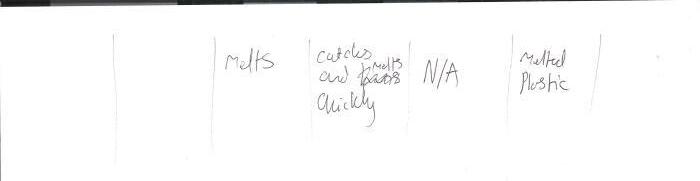

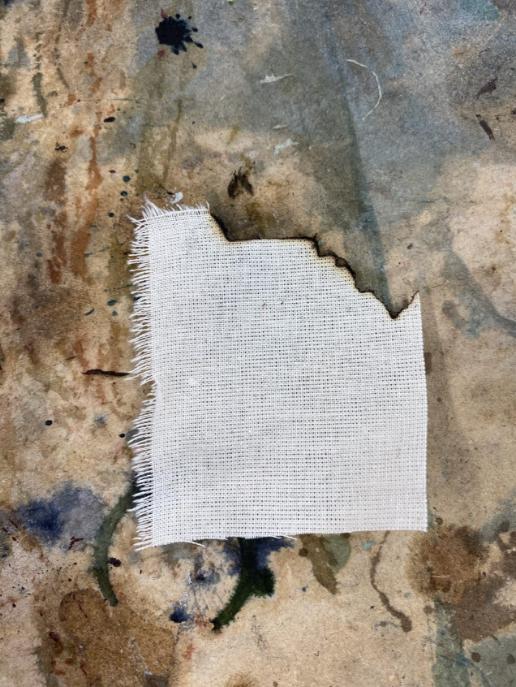

Fabric Identification

During a recent tutorial, we went over fabric identification and its merits.

Knowing your fabric type and its properties can help build a costume, making it historically and culturally accurate. It also helps when working with the actor, making sure they’re comfortable and happy while modelling or acting. As well as this, knowing the properties allows us to make decisions on maintenance, washing and taking care of costumes, dyeing, synthetic or natural dyes, or allergenics, ensuring we are keeping our actors safe.

There are 3 main ways of identifying fabrics: if you are buying online or in person, most fabrics are labelled, and from there, you can figure out their properties; physically touching and observing the fabric; and finally, a burn test.

A burn test involves taking a sample of fabric, lighting a corner of it and seeing how it reacts to flame, and recording its smell and the byproduct, ash, it leaves behind.

I performed a burn test with multiple different fabrics that are being used in costumes for Emilia. I was able to ascertain their properties and whether they were synthetic or natural.

From the burn test, I was able to tell that natural fabrics burned and smelled of burning wood, synthetic fabrics melted and smelled of melted plastic, and animal fibre, wool, singes and shrinks and smells of the animal they were sourced from

My fabrics were Cotton Velvet, which burnt and smelled of burning wood, which tells me it is natural.

Then a Brocade, which burnt and curled in on itself, and smelled of burnt wood; which tells me it is natural.

Next a wool, which took a while to catch and burnt in on itself, it smelled of burnt hair and sheep; woollen fabric is partly fire resistant which causes its slow catching. The smell of animal left behind tells us that it’s natural.

After, was Calico, which burnt quickly and smelled of burnt wood; this tells me its natural.

My final fabric was another Brocade, this fabric melted in on itself; this tells me that it is a synthetic. This shows that there can be different blends of Brocade.

Figs 1-5: Top Row, Left to Right: Cotton Velvet, Brocade 1, Wool Bottom Row, Left to Right: Calico, Brocade 2

National Portrait Gallery

During the summer, I visited the National Portrait Gallery in preparation for this upcoming show project. I looked at and collected pictures of portraiture and the trends they display.

Queen Elizabeth I herself started the most popular trends during the Elizabethan era

Queen Elizabeth’s bodice, sleeves and skirt are embellished with pearls; this was used to represent the wealth and power that the queen held. It also represents purity and chastity, as well as this, it had a link to Christianity and godliness, linking to the fact she was chosen by God to rule. It also symbolised her as the virgin queen. As this was so popular during the era, many of our makers will use pearls as decoration.

Another trend that can be seen in this portrait is the colour of Elizabeth’s dress. Black dye was expensive to get, requiring multiple components to get the colour right. As well as this getting a true black was extremely time consuming, requiring multiple dyes to get fully right. This is why the colour black is only normally seen on royalty, because of this none of our characters will be seen wearing a costume in full black. Some black wool elements will be seen as black wool was much cheaper to buy as it grew naturally on a sheep.

Black will be seen in some aspects of Shakespeare’s costume.

As well as this, paned cap sleeves are seen. These are panels of fabric, normally matching the rest of the bodice, covering gathered or puffed fabric. These caps are then normally decorated to accentuate the slashed style; these decorations are commonly pearls, embroidery or braid.

This style of sleeve will be used by multiple of our makers.

Fig 6: Queen Elizabeth I by Nicholas Hillard - 1575

In this portrait, Queen Elizabeth I wears a doublet made out of a silvery brocade, however it is suggested that the pigment has faded over time and that the portrait was originally reddish brown.

The use of the doublet makes Queen Elizabeth appear more masculine; this used to show that she is able to fulfil the role of a monarch, one of which had only been filled by men. She is showing that her being female doesn’t hold her back or make her unfit to rule.

This trend then bled into her courts, and women wore doublets to emulate her style. Multiple female characters in our production will be wearing doublets rather than bodices to make changing to their male counterparts easier, but this also allows for the designer to reflect trends of the time.

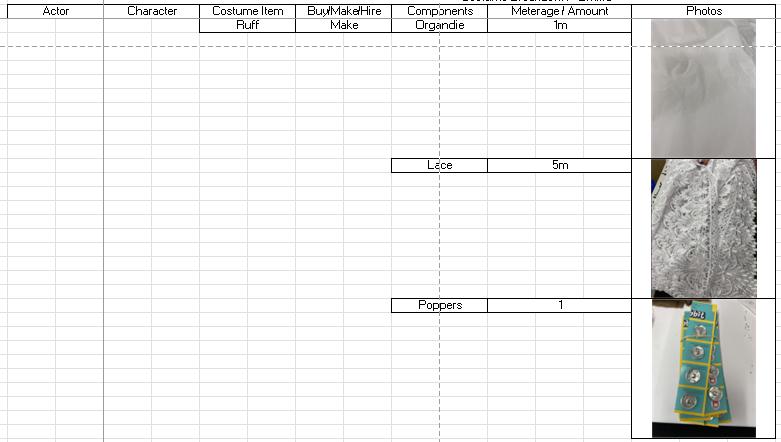

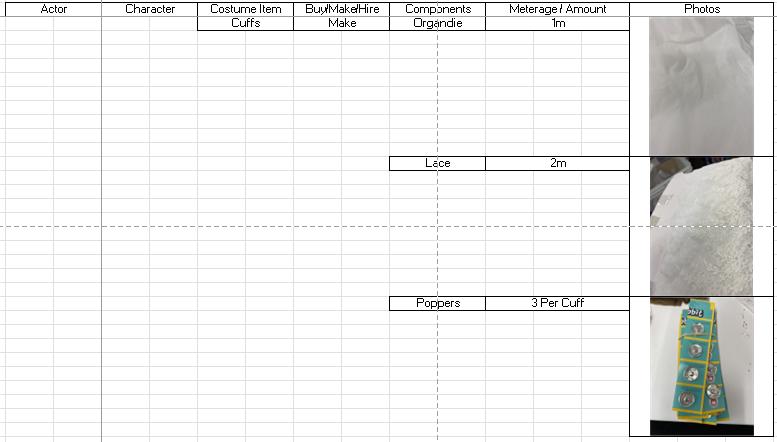

Another trend seen, in most portraiture, was that ruffs and cuffs decorated with lace, and sometimes pearls, which were popular during the Elizabethan era as their stiff nature made them inconvenient for labourintensive tasks, and as such, they were used to represent the upper class as they didn’t need to do such tasks. As well as this they protected the collar from wear and tear, and were much easier to detach and wash from the doublet or bodice, protecting against stains.

All of the costumes used on this show, sourced or made, will have ruffs and cuffs.

Unlike the portrait previously, Queen Elizabeth isn’t painted wearing cap sleeves, instead she wears farthingale sleeves. Similar to the skirts of the same name, these sleeves are structured, made up of multiple rings of whalebone to keep the shape. This takes the weight of the fabric off the arm and keeps movement unrestricted. These sleeves would then develop into the leg of mutton sleeves seen in the Victorian era. While our makers won’t make their sleeves farthingale, a similar sleeve style will be seen in some of their makes.

Fig 7: Darnley Portrait by Unknown - 1575

This portrait shows Queen Elizabeth I’s coronation in 1559, this portrait was produced for the annual celebration of such event, replicating the original portrait lost soon after 1559.

Elizabeth’s clothing is made up of gold Brocade and fur, both decorated by various jewels, giving a very regal put together look. Gold at the time was a colour that only royalty and nobles were allowed to wear, as stated by the English Sumptuary Laws. Th colour gold also represents majesty and wealth, it was also used to represent the divine light of God.

It was mainly paired with white, as it is done here, as white represented purity and was once again linked to Christianity. These colours are chosen to not only make Queen Elizabeth look regal but also confirm her place as chosen by God. The white and black fur of her cloak is made up of Ermine fur, of which could only be hunted by and for royalty. The white fur would be taken from the main body of the Ermine and the black fur from their tail.

The florals were a very popular decoration throughout the Elizabethan era, as Elizabeth liked such styles, and through that, it became a trend. The florals seen here are Tudor roses, these were used to represent the continuation of the Tudor line through Elizabeth and that she would uphold their ideals throughout her reign.

Fig 8: The Coronation Portrait by Unknown - 1600

Sir Henry Lee commissioned this portrait to ask for Queen Elizabeth’s forgiveness when he retired and went to live with his mistress, Anne Vavasour, Elizabeth’s maid of honour in previous years.

Queen Elizabeth’s outfit is made up a white silk, once again using pure white to represent her purity and virginity, as well as this, silk was an expensive fabric and was used to represent her higher class.

See clearly in this portrait is Elizabeth’s farthingale skirt, like the farthingale sleeve, this skirt is made up of a structure made of whalebone rings, holding up the skirt and allowing for movement. To soften the harsh extension of the bodice to the wide hips of the skirt, there is also drum ruffle, which is a pleated section of fabric that goes over the top skirt but sits under the bodice. The farthingale was popular amongst the ladies of the court and while our makers are not including farthingale skirts in their costumes, they will be using a bum roll to create a similar silhouette.

As accessory, Queen Elizabeth is using strings of pearls, these pearls were expensive, which show Elizabeth’s wealth. As well as this, pearls were used to represent purity and virginity, which once again supported the idea of the virgin queen. Pearls were also popular inside the court as other women used it to show their wealth and purity.

Pearls are widely used in the designs for this show.

Fig 9: The Ditchley Portrait by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger- 1592

This portrait was produced during her imprisonment and marked 10 years at Tuxbury Castle after she had been incriminated by letters that suggested she had arranged the murder of her husband.

At Tuxbury Castle, Mary was still treated well; this can be seen in her expensive clothing. Black was an expensive dye to produce, requiring multiple rounds of dyeing to get the rich colour. This shows that even during her imprisonment she was an important noble figure.

Further aspects of her nobility can be seen in her collar and ruff, a stand collar as seen in this portrait would require careful pleating and starching to achieve its shape, as well as this both the collar and cuffs have been decorated with lace.

In comparison to Queen Elizabeth, Mary’s jewellery is quite modest, mostly being supplied by Elizabeth or by those under Elizabeth’s employ, this keeps Mary less extravagant than the queen. As well as this, Mary’s jewellery is functional rather than symbolic; it plainly states her catholic faith and would have been used in her day-to-day life, especially the rosary on her hip.

Fig 10: Mary, Queen of Scots by Nicholas Hillard - 1578

Othello

While reading the Emilia script, I came across a passage of Othello; it is midway through Act 4, Scene 3, where Emilia and Desdemona are discussing cheating and abusing their husbands.

Previously in the year I had been to see Frantic Assembly’s performance of Othello, they had reimagined it to take place in an English pub during the 21st century rather than the 1570s. With this change to the 21st century, the costume choices have changed to reflect this, switching out Elizabethan fashions for more modern styles.

Through this change in set and costume, it helps recontextualise it for a more modern audience and makes it more accessible for everyone. Not only does it make the play seem more believable, as if such a situation could be happening down the street, the costumes also allow for more dynamic movement from the actors which makes for a more interesting watch for the audience.

The more available options of dynamic movement is fully taken advantage of with there being dance breaks and dramatic fight scenes.

Fig 12: Screenshot from rehearsals of Frantic Assembly’s ‘Othello’

Fig 11: Screenshot from Frantic Assembly’s ‘Othello’

Frantic stages the scene, as mentioned previously, in a bathroom, a situation that many women can draw from, from a night out and going to the toilets together which once again helps make the play more relatable. Emilia and Desdemona are both dressed in t-shirts, joggers and trainers, Desdemona also carries a denim jacket.

While Frantic’s version of Othello concentrates less on the roles of servants being show through their clothing, Desdemona is dressed in a neater way, with her tighter-fitting clothes and has a jacket to deal with colder temperatures, while Emilia is dressed in a slouchier more casual way. This shows the personal choice of aesthetics as well as the clothing items available to each character without the audience being told of such things.

When it comes to our production of Emilia, our designer has decided to keep costumes historically accurate so will not be taking inspiration from this version of Othello but I still enjoyed watching and taking note of the costume choices of Frantic’s production. As well as this due to the multi-role nature of Emilia the costumes of Desdemona and Emilia will be kept simple and will most likely need to cover up costumes for other characters that the actors are playing.

Fig 13: Screenshot from Frantic Assembly’s ‘Othello’

Secondary Research

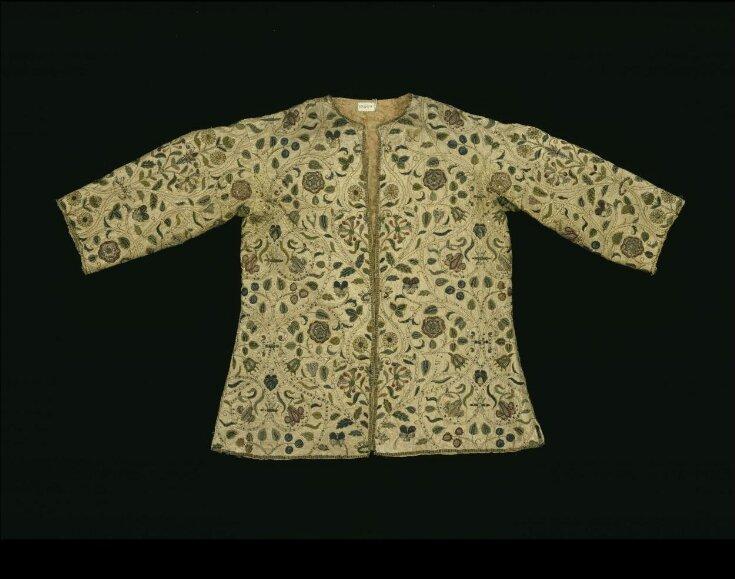

Womenswear from 1590 to 1610

For this show I am looking at women’s fashion from 1590 to 1610. For men’s fashion see bible by Lauren Mayers, and for accessories see bible by Never O’Brien.

Fashion during the last decade of the 16th century stayed quite similar to the decade before it. Women’s outfits were made up of a boned bodice with a square neckline, wide sleeves with whalebone in them to keep their shape, a stomacher, kirtle, petticoat, a large skirt, a ruff or collar, and lace cuffs. Ruffs, collars, and cuffs were attached with linen laces.

Like earlier eras, most fashion trends were taken from other countries and exaggerated. The pointed centre of the stomacher, inspired by French fashions, was made longer and narrower. This paired with an everextended farthingale, once again inspired by French fashions, made for an extremely unbalanced silhouette. This only happened with female silhouettes, if anything male silhouettes were reduced, in deference of the queen, and her style. As whalebone became more accessible, the size of farthingales grew, and the skirts draped over them, became larger and larger. So much so, that pockets began to be able to be sewn into skirts. Over the use of bags.

Ruffs were also larger, held up by an underpropper, or Supportasse,, included detailed lace patterns and sometimes beading or jewels.

Trends that originated in England were mainly set by women trying to emulate Queen Elizabeth I, following her silhouette, ruff style and size, colour of dress, black and white, use of florals, and increased lavishness of decoration and embroidery. The aim was to look expensive, as black dyes, pearls and extensive embroidery showed that.

As stated above, florals and nature became the main point for embroidery. Pattern books were read by the masses and embroiders, amateur and professional, copied designs of flowers, insects and animals.

Embroidery became one of the more attainable types of decoration, from ready to wear accessories, which became available through the Royal Exchange. The most well-known types of embroidered accessories were headdresses, handkerchiefs, small bags, and gloves. At the time gloves were used as romantic tokens and could carry a wide range of romantic symbolism on them through their embroidery.

Symbolism was important when I came to decorations. Flowers and nature held religious themes, representing God’s abundance and gift to humanity, white roses specifically were used to represent purity and virginity and referenced the Virgin Mary and her innocence.

Tudor roses were also popular, as it supported the queen and showed the abundance of the Tudor lineage and how far it had grown.

Fig 14: Catherine Carey, Countess of Nottingham - 1597

Robert Peake the Elder

Even after Elizabeth I’s death, in 1603, trends from influenced by her and the past era persisted into the present one, the Jacobean Era. Heavy floral and nature embroidery remained a popular decoration to bodices, doublets and waistcoats.

While some trends persisted, as the decade went on old trends were changed and built upon. Ruffs were slowly replaced by standing collars, which framed the face, they still rivalled the size and extravagance of ruffs.

Necklines also began to be brought down to reveal the bust, rather than the higher necks that came with ruffs. Sleeves were slowly brought in from the previous ‘mutton leg’ sleeves, and were instead were closely fitted with the sleeve hem ending several inches above the wrist

The French farthingale’s hard edge was softened by a large ruffle, with the skirt’s hem was brought up to reveal newly heeled shoes.

Most of these changed trends were brough to England from France by a woman of the court, Anne Vavasour, who came from Yorkshire to become a gentlewoman of the bedchamber, who then later became mistress to the 17th Earl of Oxford and then, even after, mistress and de facto wife to Sir Henry Lee of Ditchley.

Outfits were mainly made up of the same components, except now bodices went without bones and the body was instead supported by a pair of stays that went under the bodice but over the chemise.

Fig 16: Anne Vavasour - 1605 John De Critz

Fig 15: Pair of Gloves - 1600 V&A

Womenswear 1590-1600

reference pictures

Fig 21: Dress Border– 1590-1600 V&A

Fig 17: Queen Elizabeth I of England –1592

Nicholas Hillard

Fig 18: Embroidered Jacket – 15901600 V&A

Fig 19: Miniature of Queen Elizabeth I – 1595-1600

Nicholas Hillard

Fig 20: Double Portrait of Sir John Harington of Kelston and Lady Harrington – 1593 Unknown

Womenswear 1600 - 1610

reference pictures

Fig 26: Katherine Villiers, Dutchess of Buckingham – 1600-1610 Magdelena de Passe

Fig 22: Embroidered Coif – 1600-1610 V&A

Fig 23: Embroidered Bodice – 1600 Kyoto Costume Institute

Fig 24: Ruff – 1600-1610 V&A

Fig 25: Supportasse – 1600-1610 V&A

Dyes during 1590 to 1610

The use of dyes was quite popular during the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras. Plants were used to achieve various colours, such as: Weld, to make a yellow dye, Woad, to make blue dye, and Madder root, to make red dye. All of these weeds are colloquially known as dyer’s weed.

Other items were added to the dyes to affect the colour, such as: rust, which would turn a red dye to a purple dye, or oak galls, to make a rich brown.

More expensive dyes and fabrics were brighter, more vibrant, and sometimes imported from Europe. Rich purples and blues were normally dyed using ground-up insects, known as grain, and rich reds were made from ground-up seashells.

To achieve Queen Elizabeth I’s titular black, the fabric was first dyed with Woad, to give it a blue undertone. Then, after the fabric was dry, dyed with in Madder.

Fig 30: Modern dyeing of stockings using Tudor techniques

Paula Hohti

Fig 27: Weld Plant

Fig 28: Woad Plant

Fig 29: Madder Root

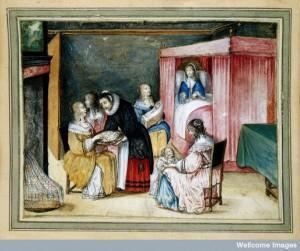

Midwives During the 17th Century

During the 17th century midwives, and midwifery, was under the responsibility of the Church of England. When they were licensed, they swore oaths, these oaths often swore that they would:

Serve both the rich and poor, of which they served for free if they were unable to pay.

Report information to the father, along with any children born out of wedlock.

Baptising babies that were unlikely to survive, alongside making the church aware of said baptisms.

Keeping with patient confidentiality.

Burying stillborn babies properly.

Aiding other midwives and teaching their apprentices.

Reporting their peers if they did not upkeep their oaths.

Such oaths paid important attention to community and helping others, furthering midwifery throughout generations.

Most midwives started under the apprenticeship of a more senior midwife, where they attended and aided in deliveries and then moved on to working on deliveries on their own; such apprenticeships lasted from 4 to 10 years.

Due to these apprenticeships, by the time midwives applied for their licenses, they already had years of experience, even decades, due to the high price of said licenses.

As well as gaining experience through tutelage, lots of midwives had experience of childbirth through being mothers themselves.

Midwives also had to be ‘good of character’ and practising Christianity, actives members in their parishes.

Through this, midwives were highly respected and were sometimes called to attest in courts, such as when a woman ‘pleaded the belly’ where they claimed to be pregnant to avoid execution, as well as cases of wedlock and cases of rape.

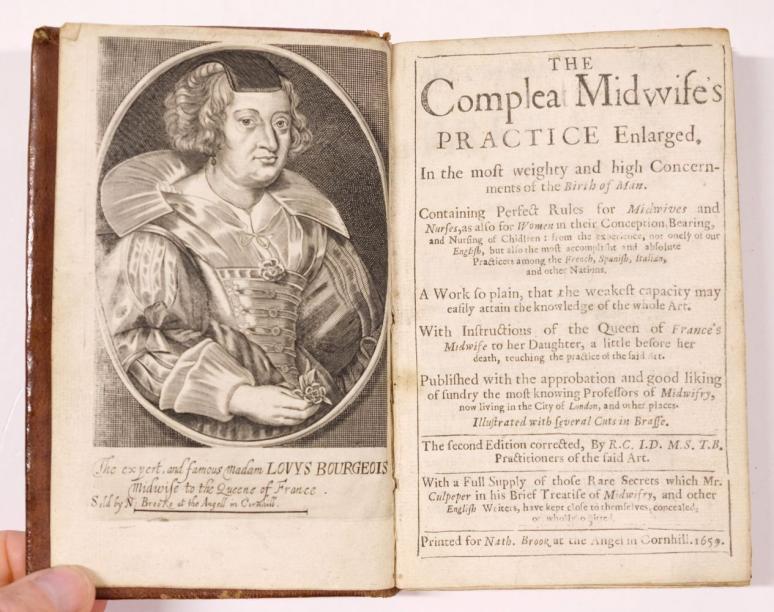

As time went on midwives even began to publish manuals, attempting to assert themselves as the leading authority on pregnancy and childbirth, this was due to feeling threatened as male midwives began to emerge in the 17th century and it became a more stable profession a person could make good money from.

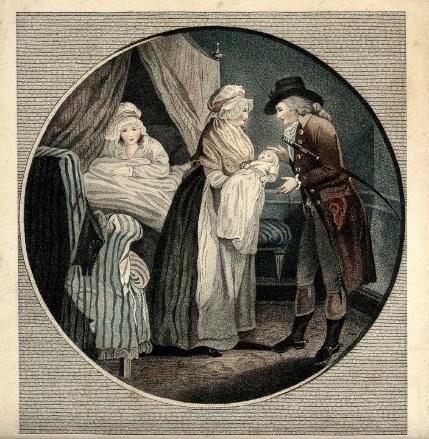

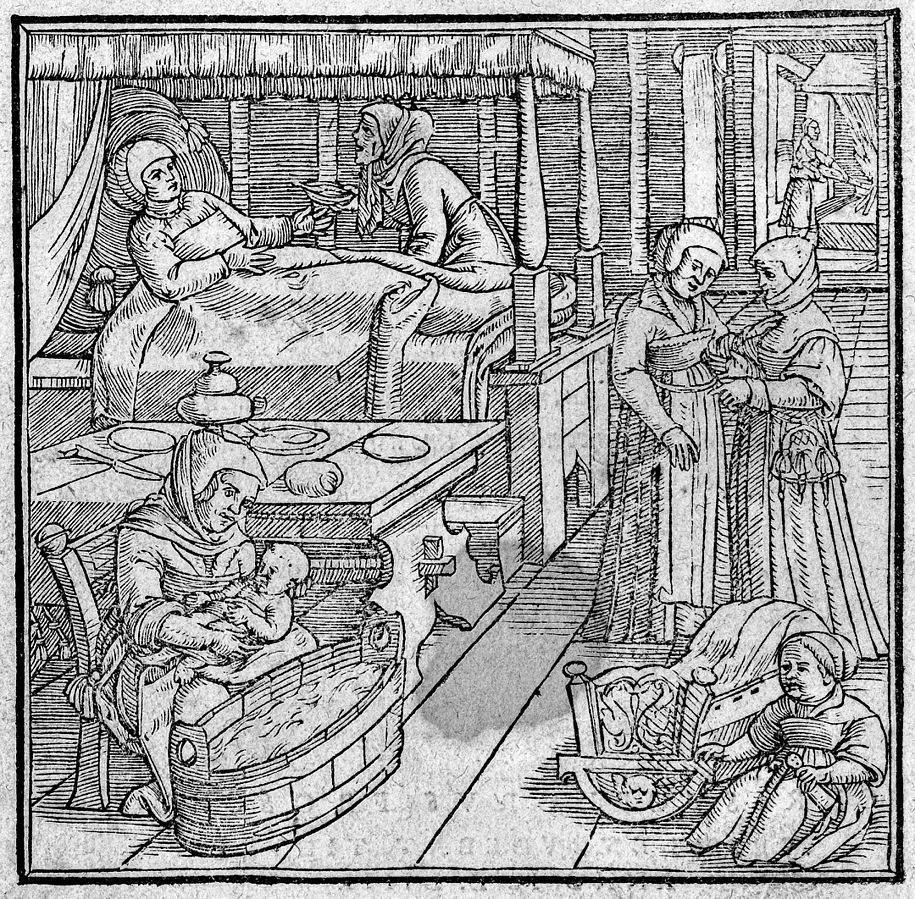

Fig 31: Etching of Birth

Fig 32: Etching of Birth

Photos for Reference

Fig 33: A Drawing Comparing Male and Female Midwives

Fig 34: Drawing of Midwife Presenting Baby to Father

Fig 35: Drawing of Birth

Fig 36: Etching of Midwives Caring for Mother After Birth

Fig 37: Scan of ‘The Complete Midwife’s Practice’

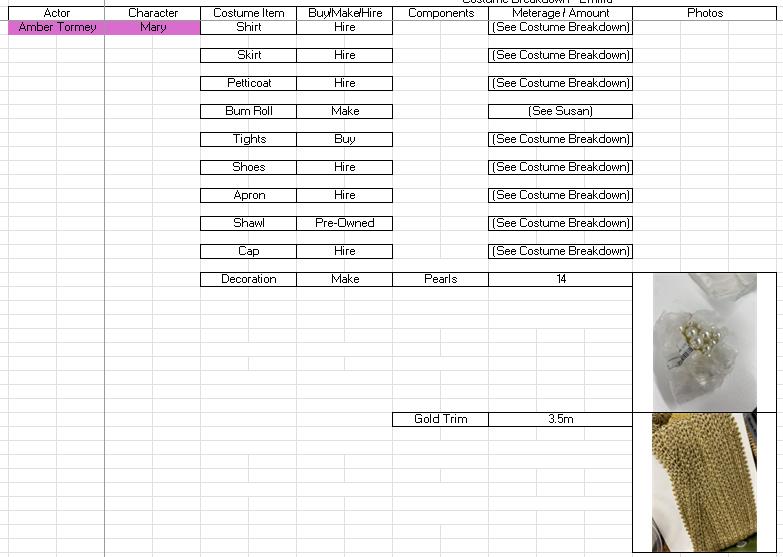

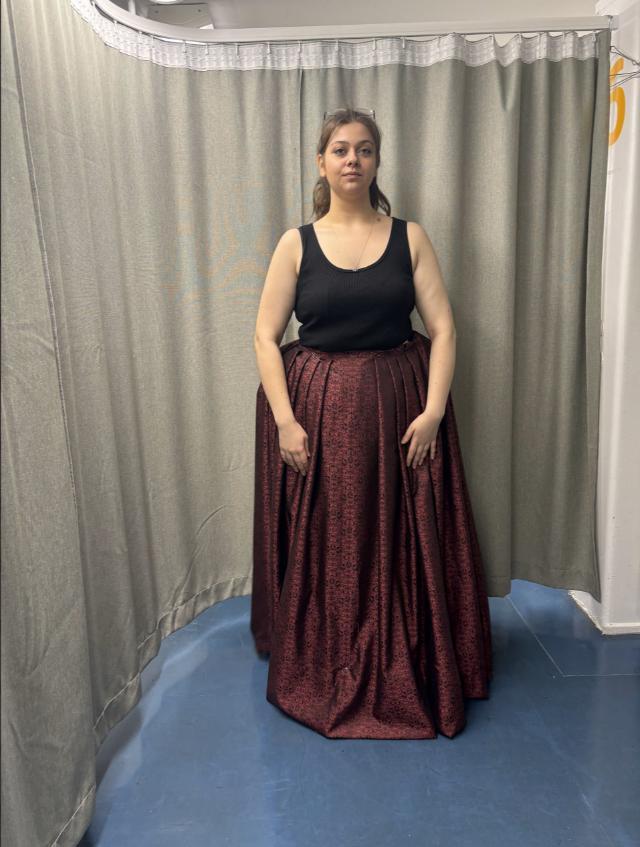

Amber Tormey

Susan Bertie / Bob / Mary

Designs Susan Bertie/Bob/Mary

Figs 38-40: Designs by Bethany Lipscombe

Measurement Sheet

Measurement Photos

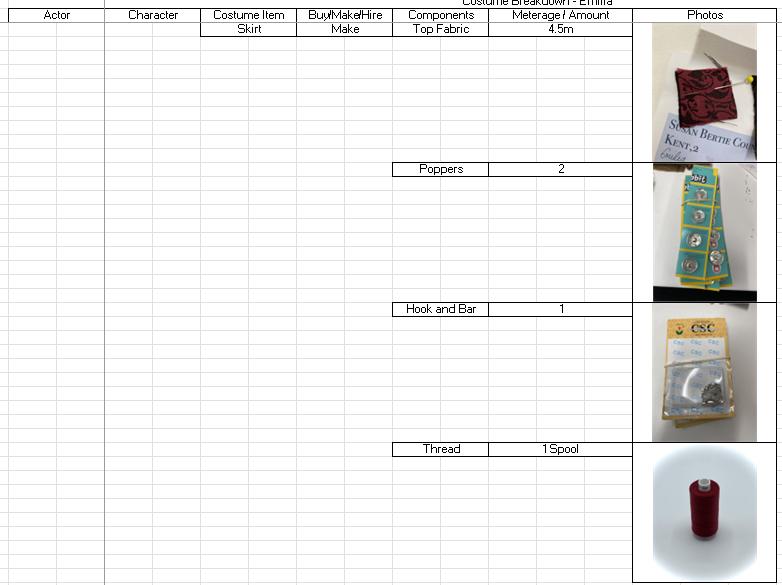

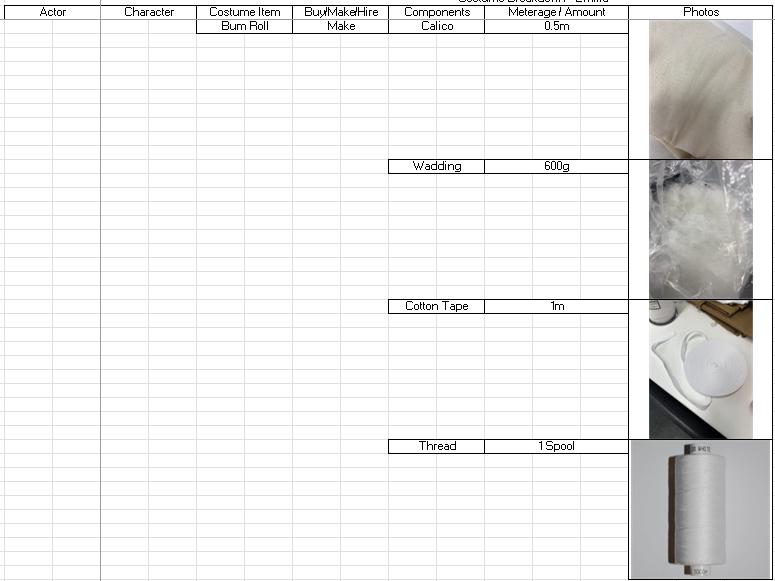

Make Breakdown

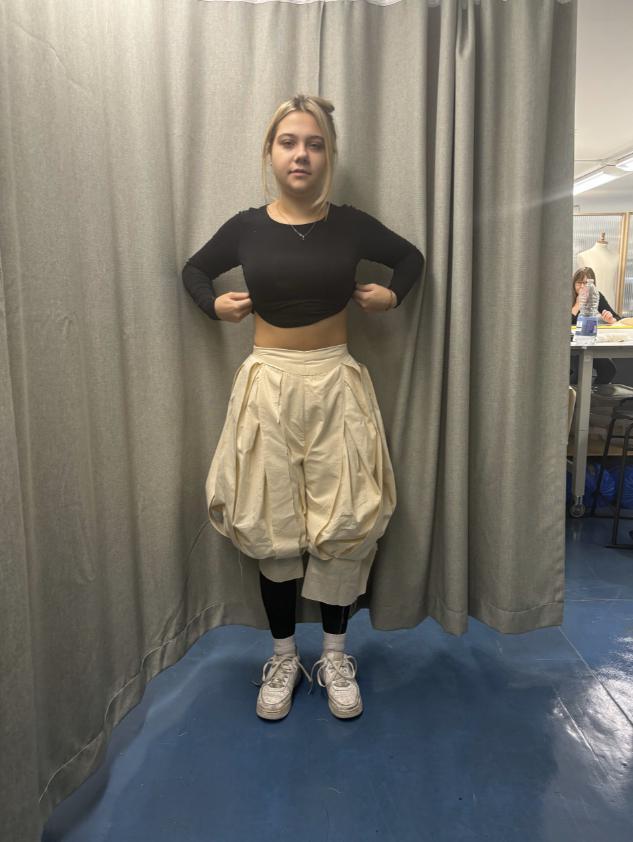

Fittings 1 Before Photos

Fittings 1 After Photos

Fittings 1 After Photos

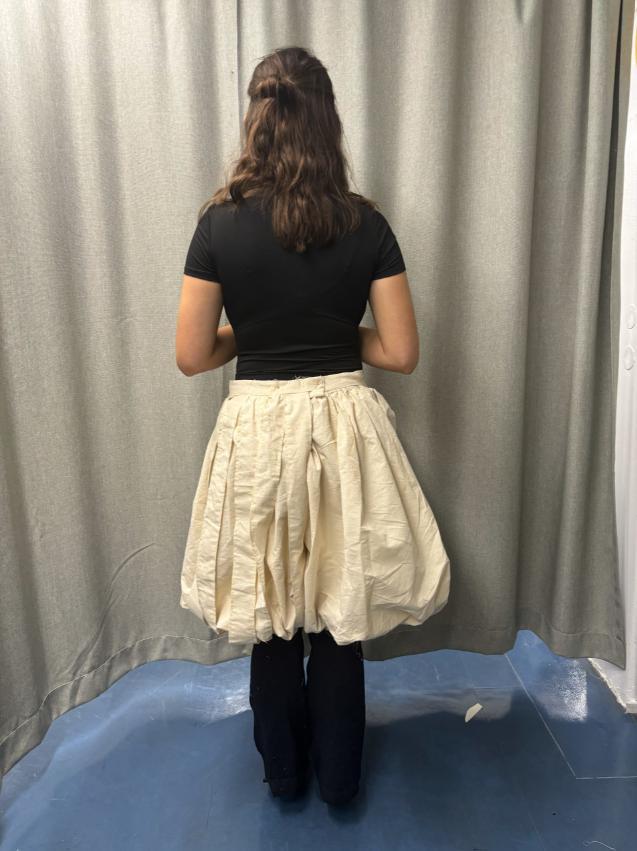

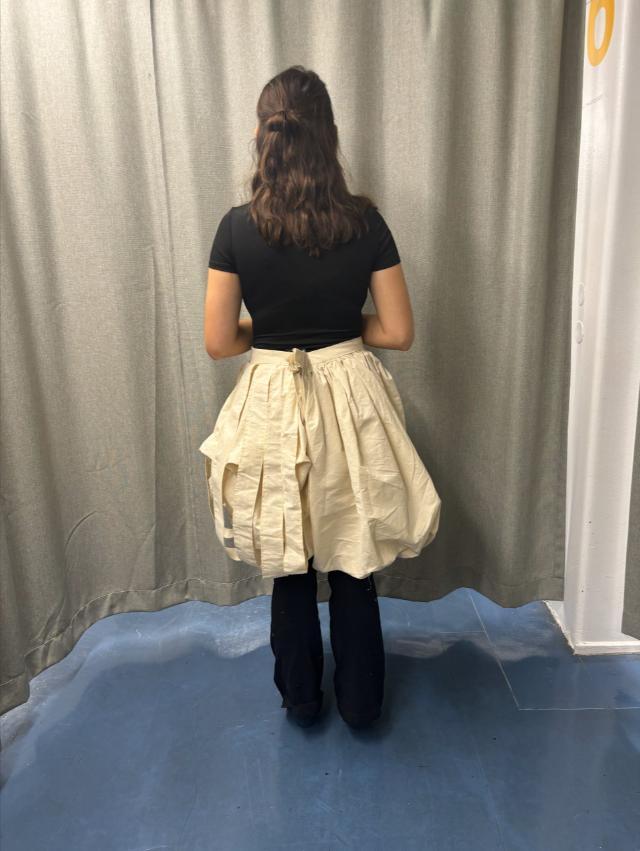

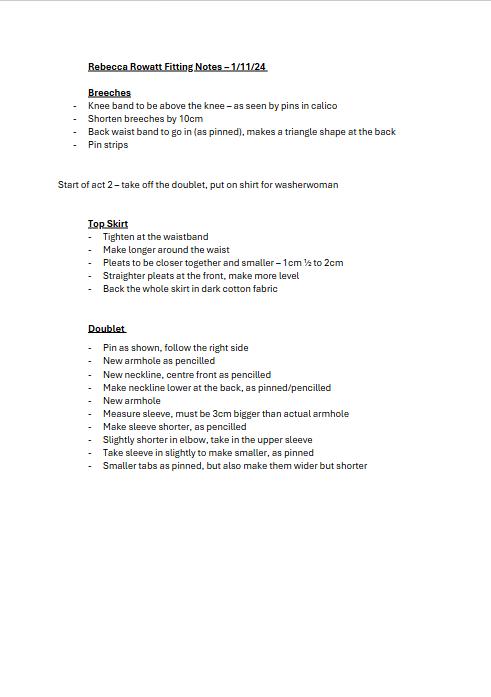

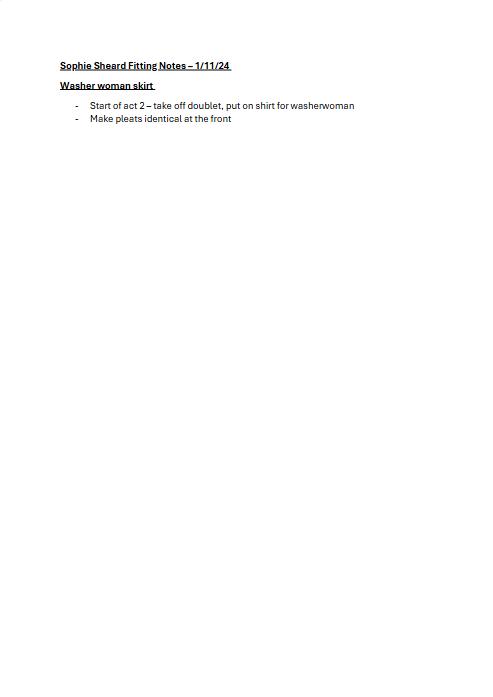

1st Fitting Notes

Fittings 2 Before Photos

Fittings 2 After Photos

2nd Fitting Notes

Pre-Assessment Photos

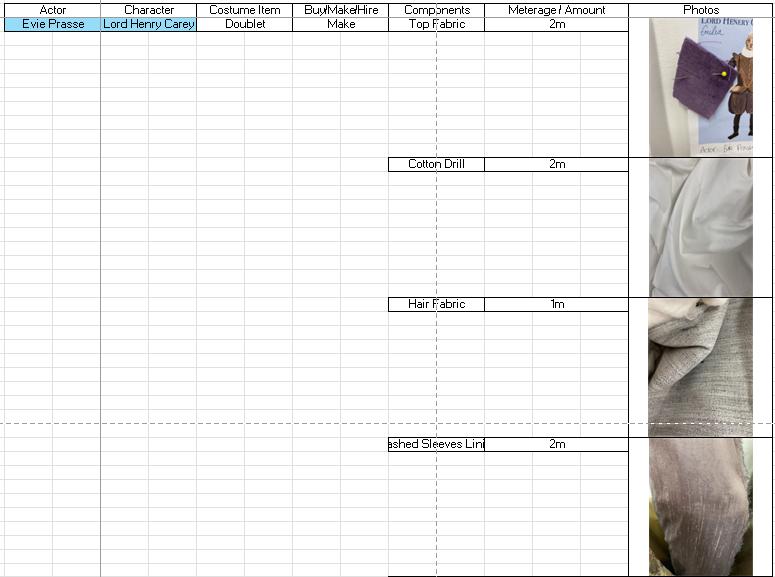

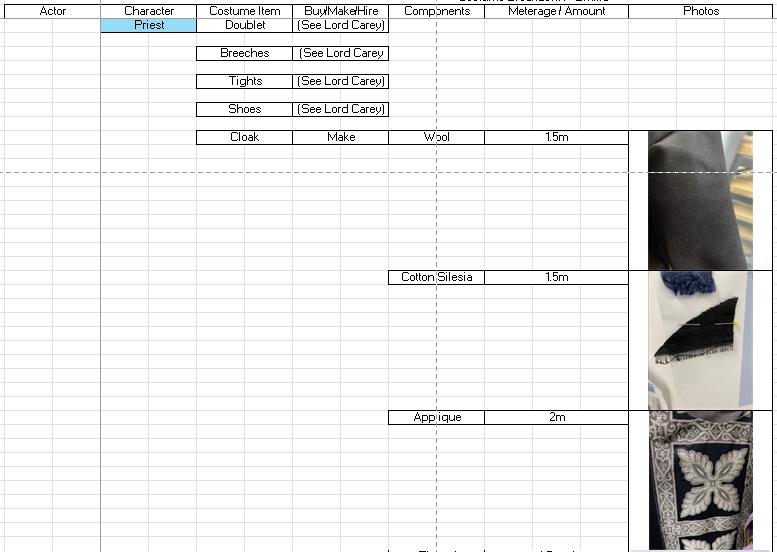

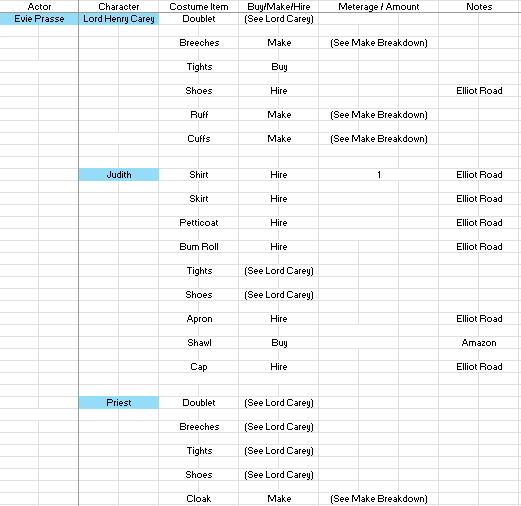

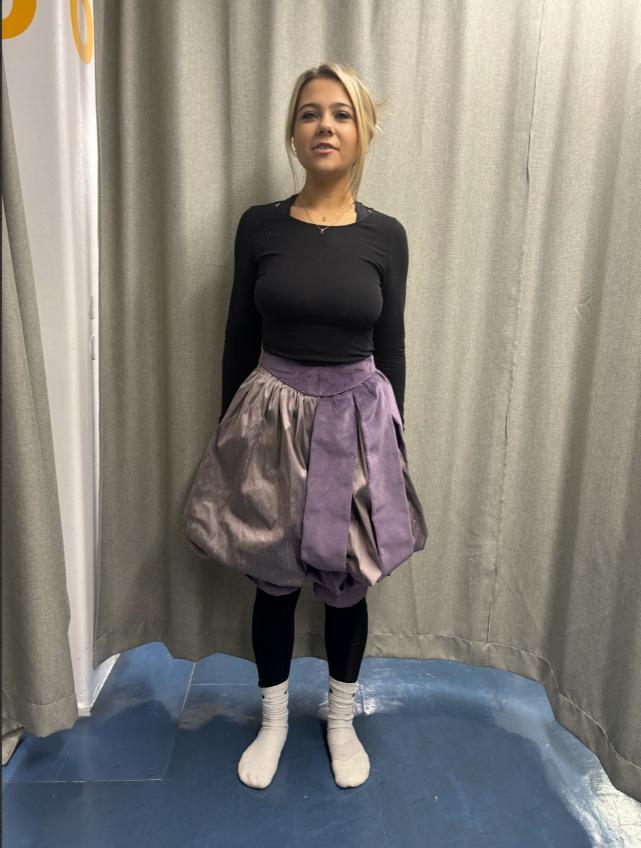

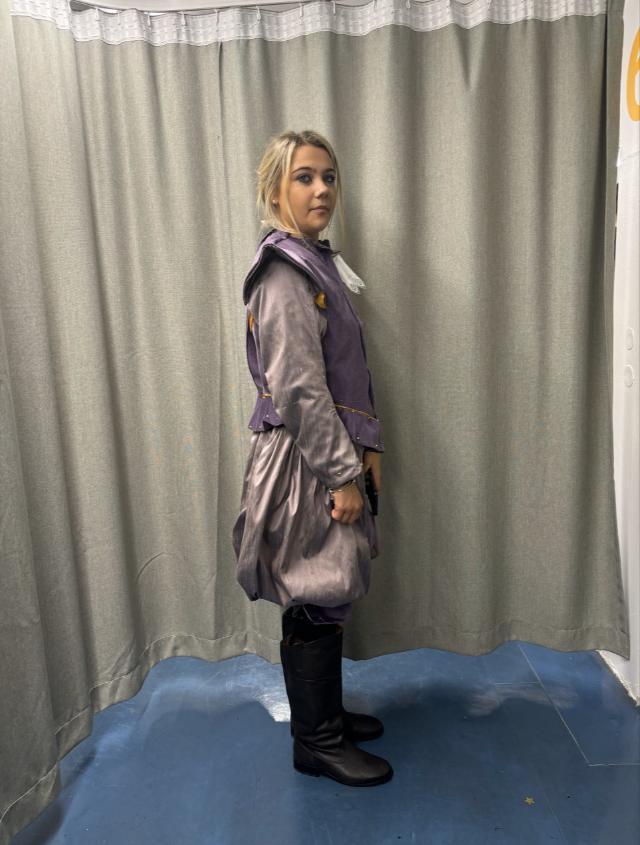

Evie Prasse

Lord Henry Carey / Judith / Priest

Designs

Lord Henry Carey / Judith / Priest

Figs 41-43: Designs by Bethany Lipscombe

Measurement Sheet

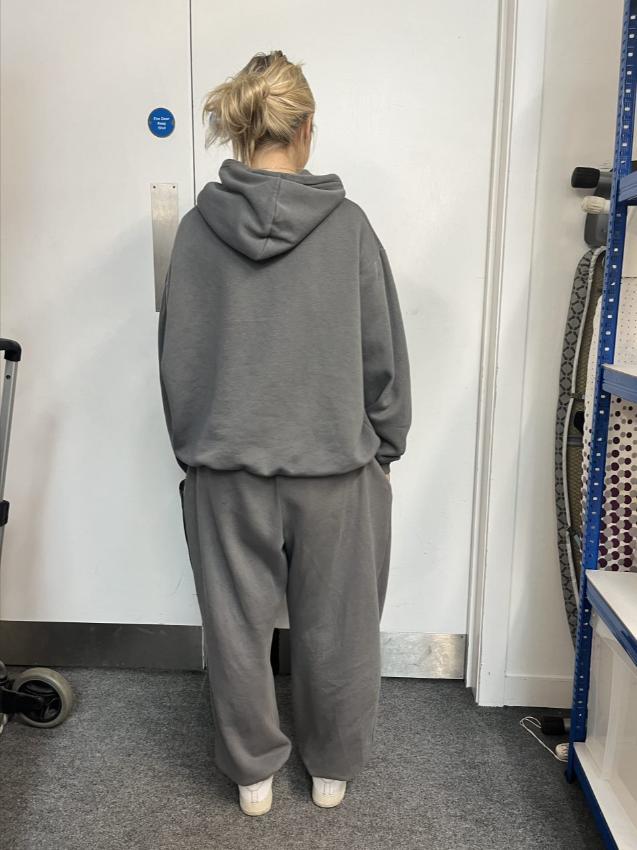

Measurement Photos

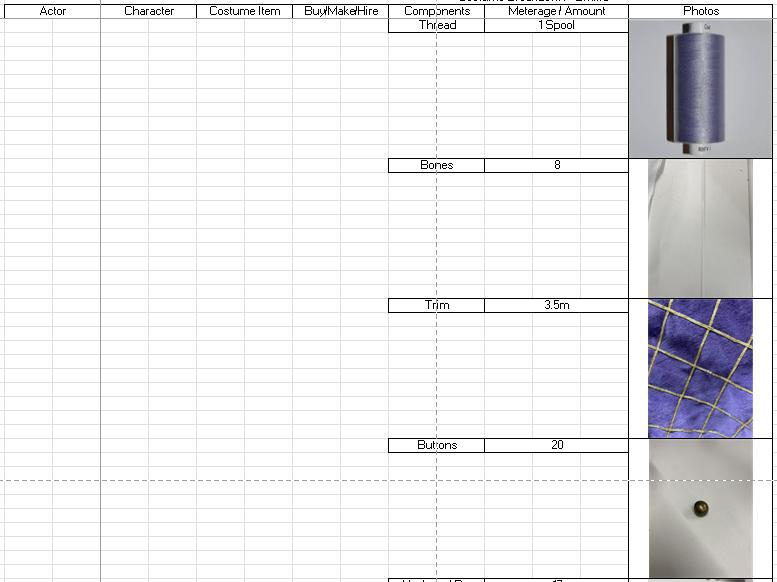

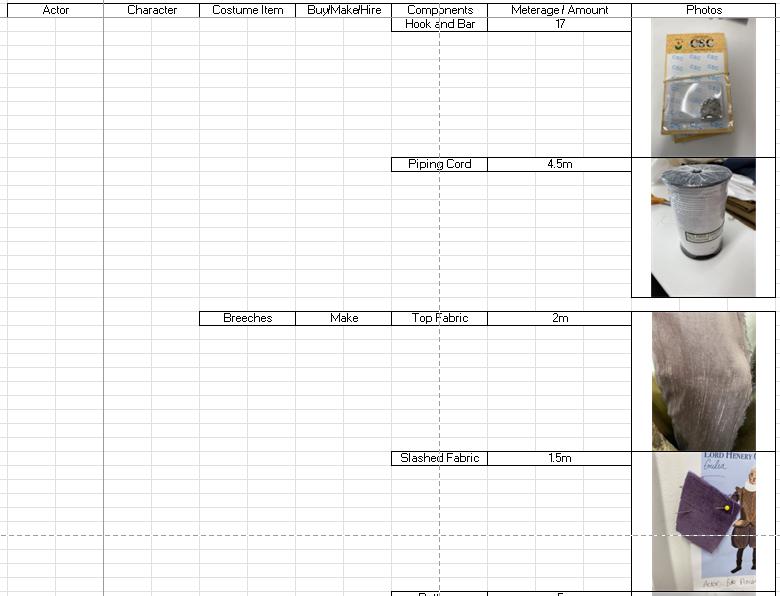

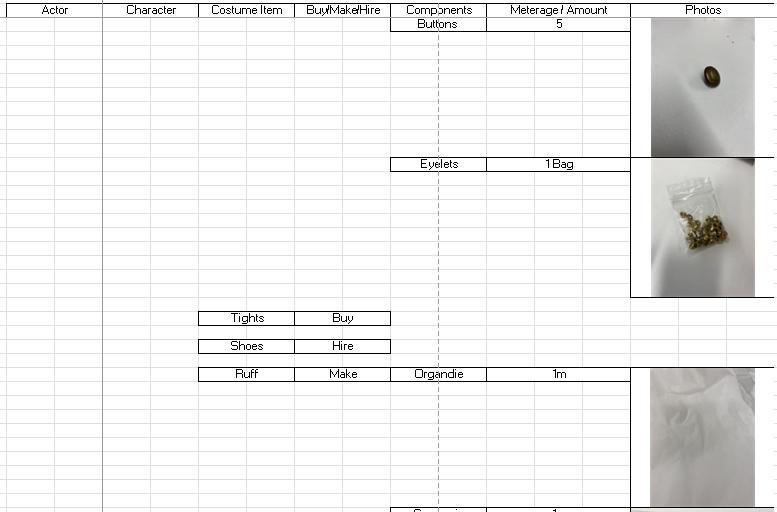

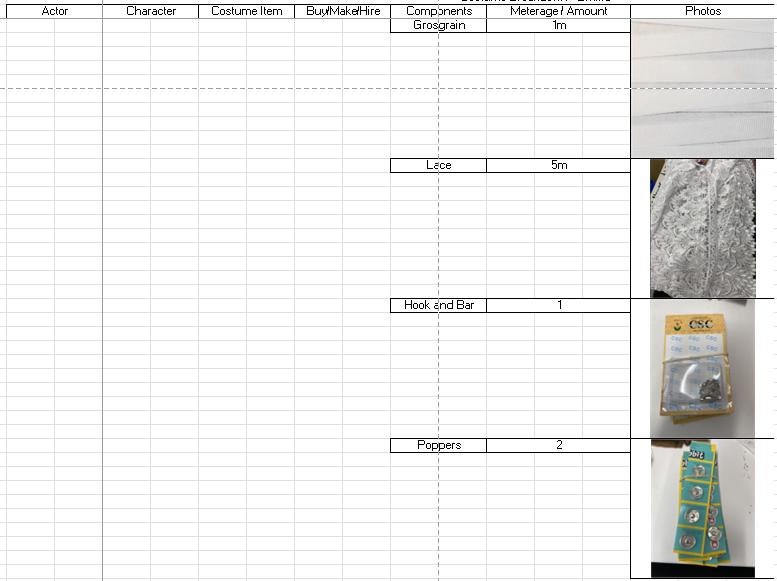

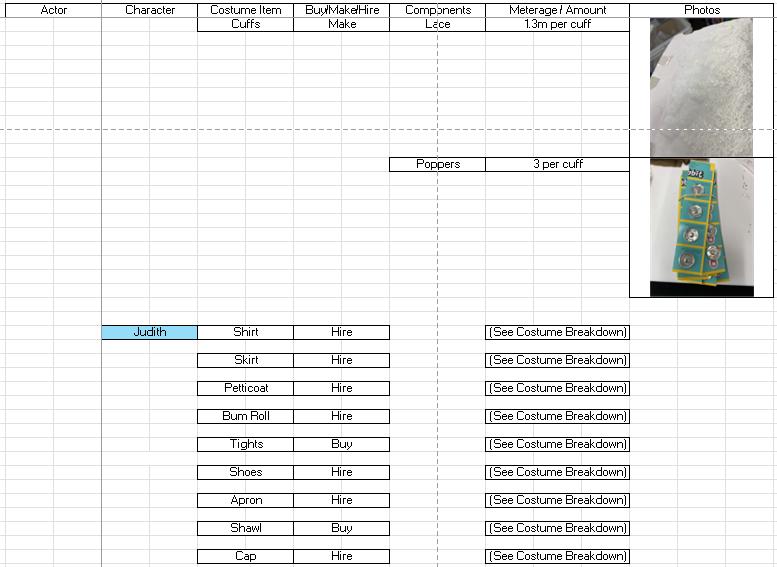

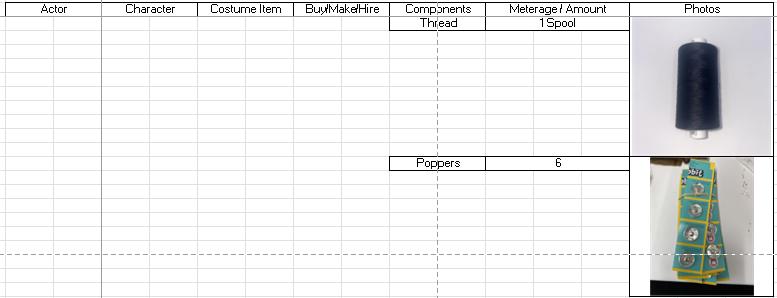

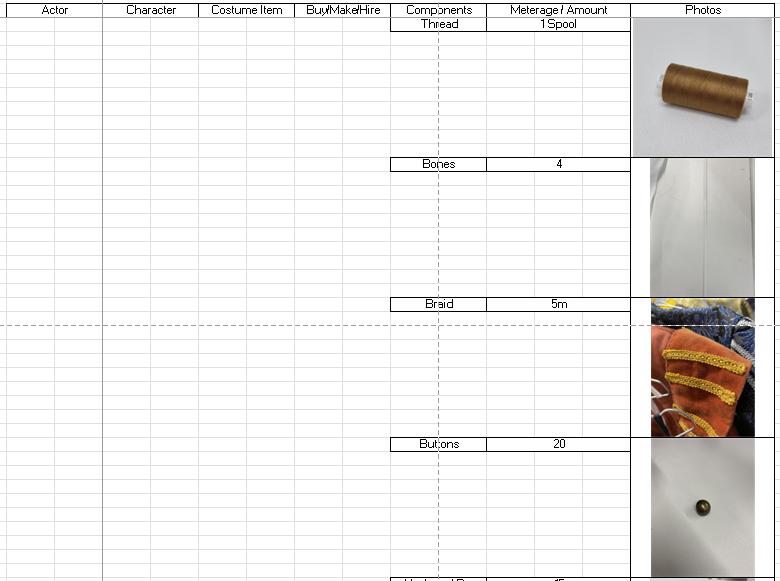

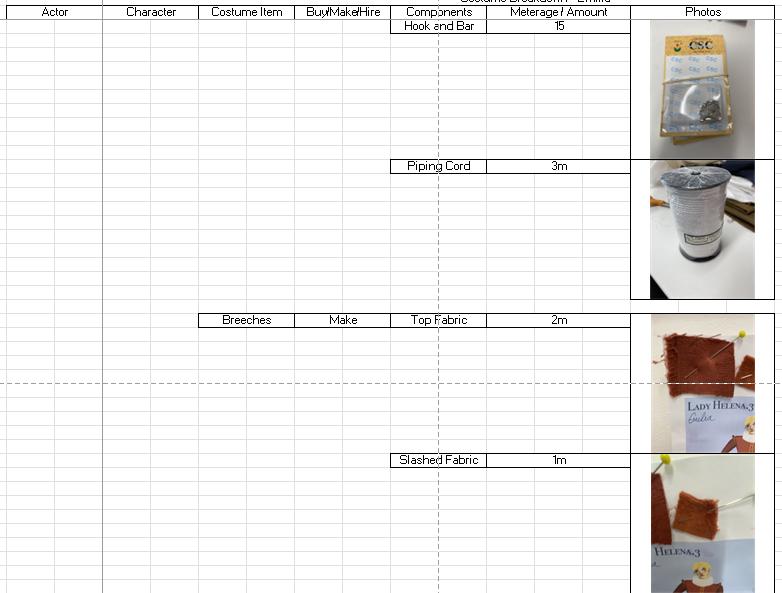

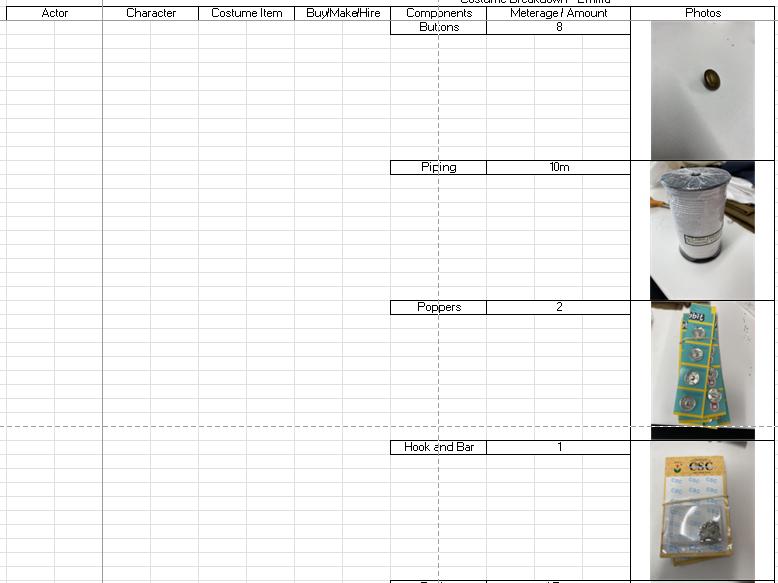

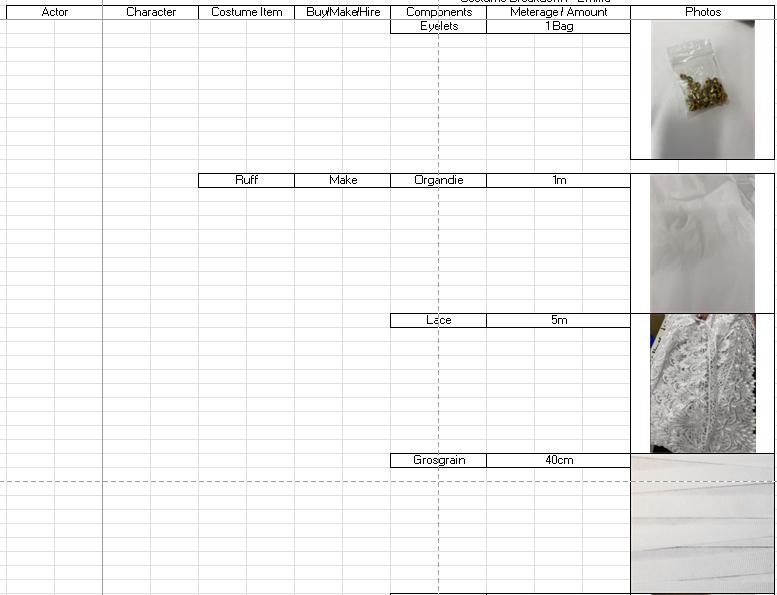

Costume Breakdown

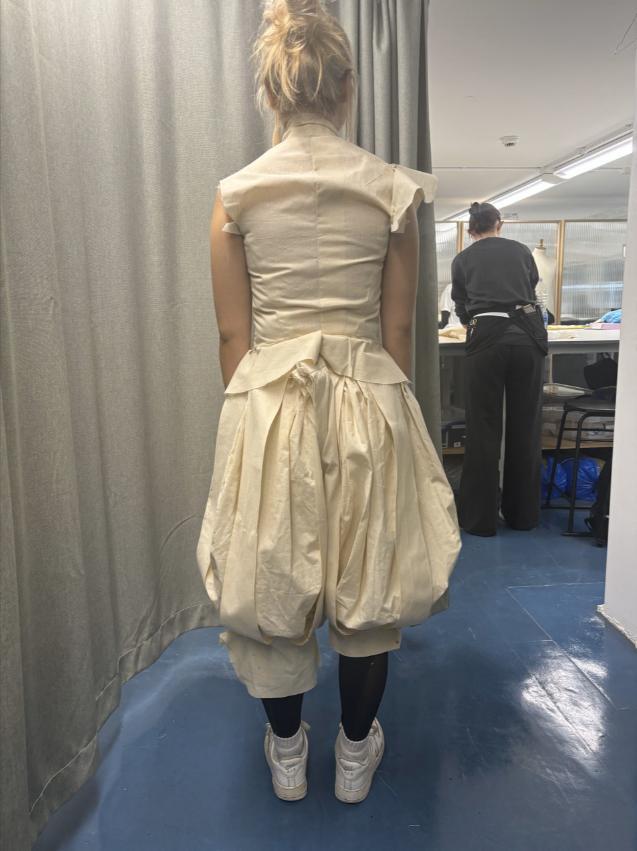

Fittings 1 Before Photos

Fittings 1 After Photos

Fitting Notes

Fittings 2 Before Photos

Fittings 2 After

Photos

2nd Fitting Notes

Pre-Assessment Photos

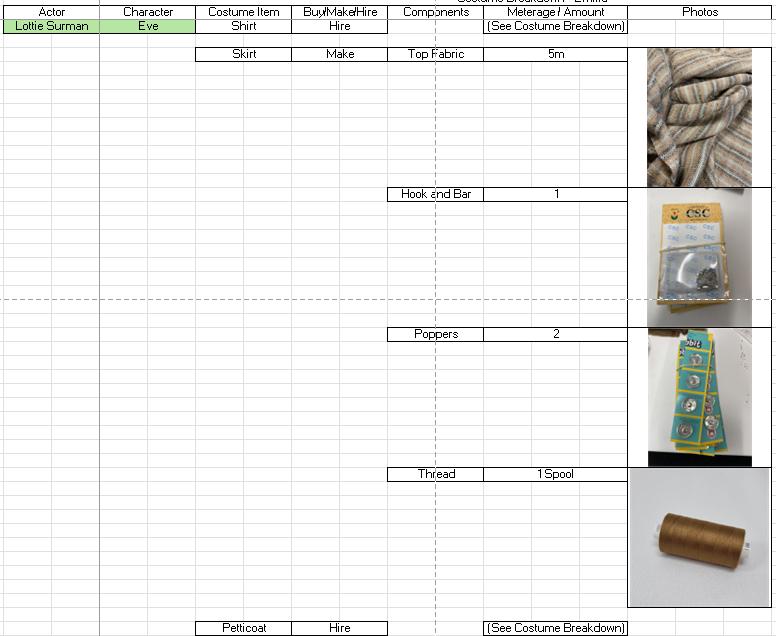

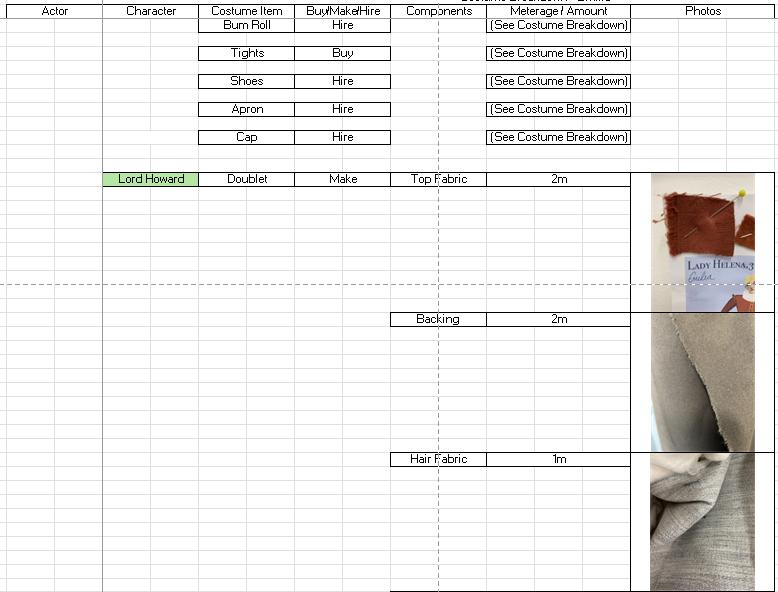

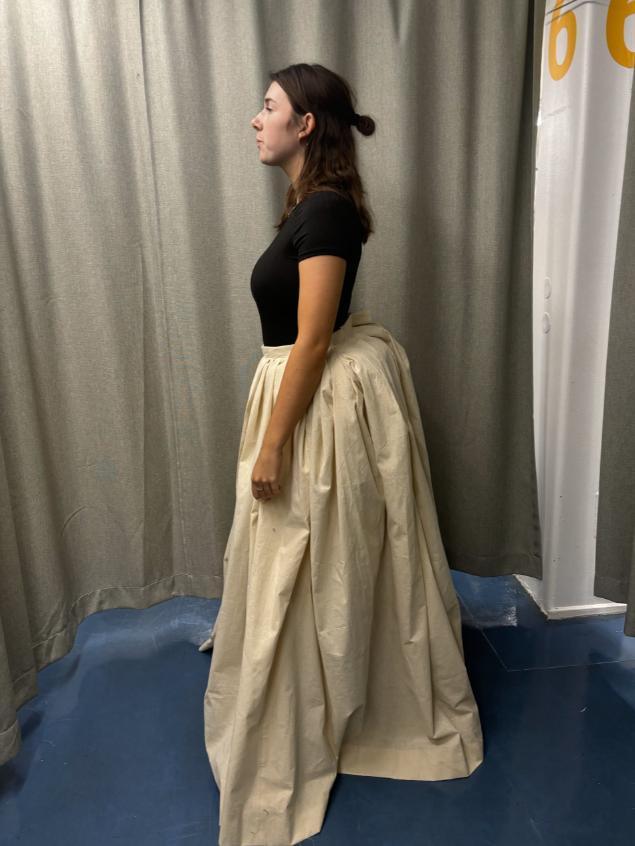

Lottie Surman

Eve / Lord Howard / Lady Helena

Designs

Eve

/ Lord Howard / Lady Helena

Fig 44-46: Designs by Bethany Lipscombe

Measurement Sheet

Measurement Photos

Make Breakdown

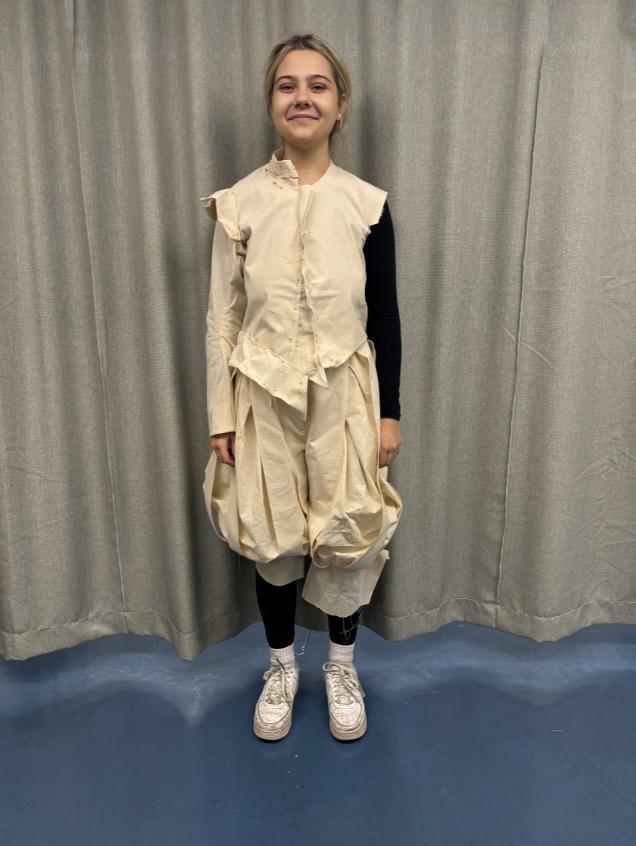

Fittings 1 Before Photos

Fittings 1 After Photos

Fitting Notes

Fittings 2 Before

Photos

Fittings 2 After Photos

2nd Fitting Notes

Pre-Assessment Photos

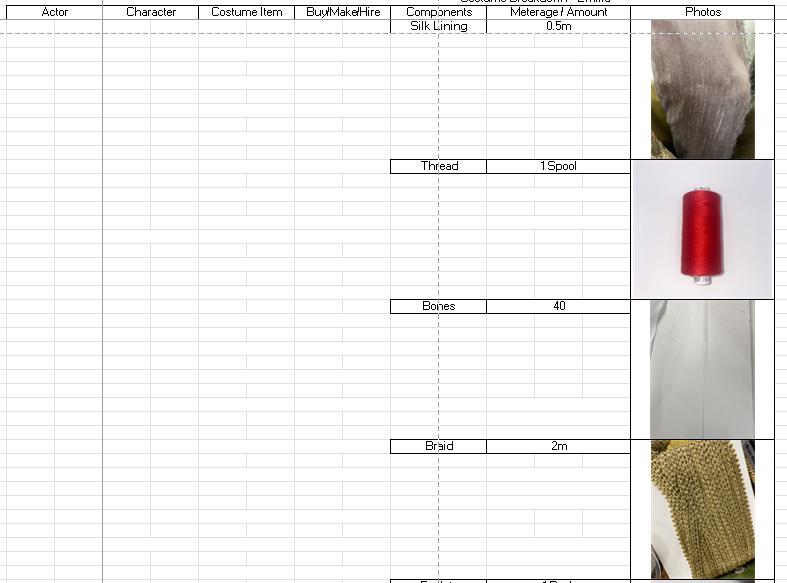

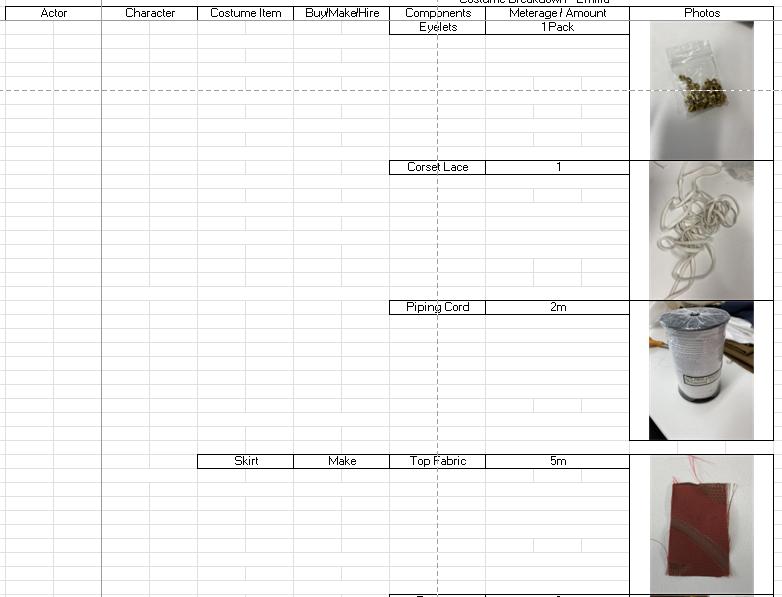

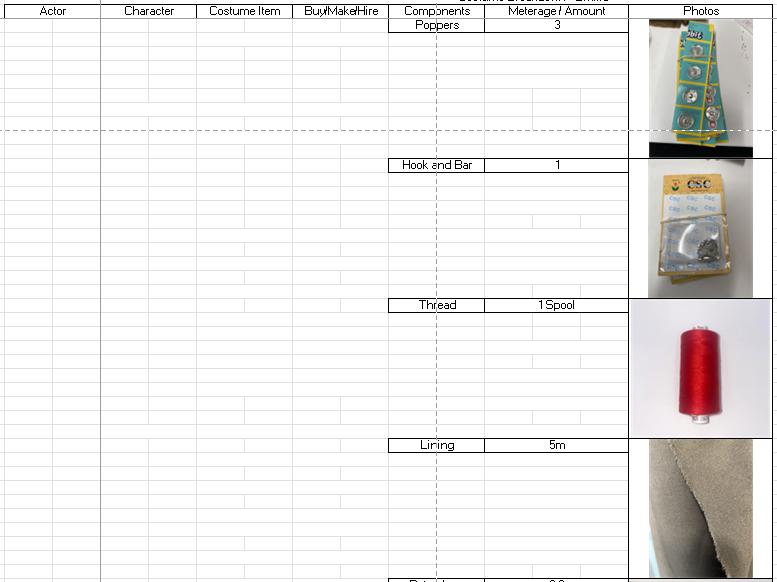

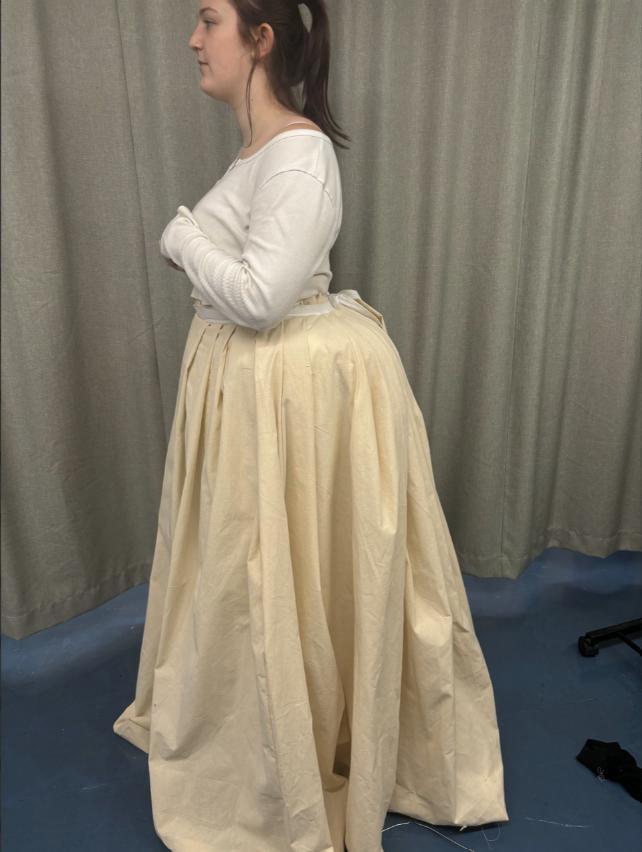

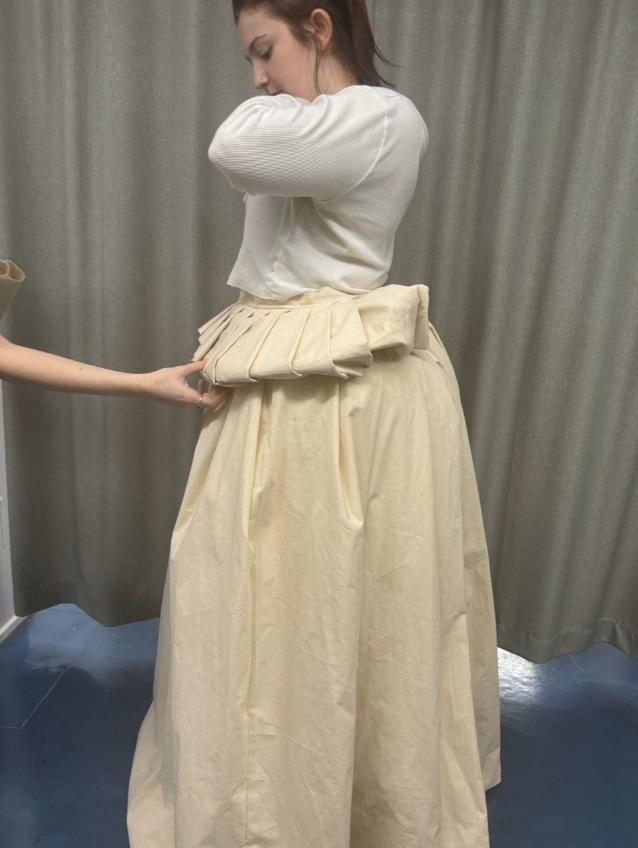

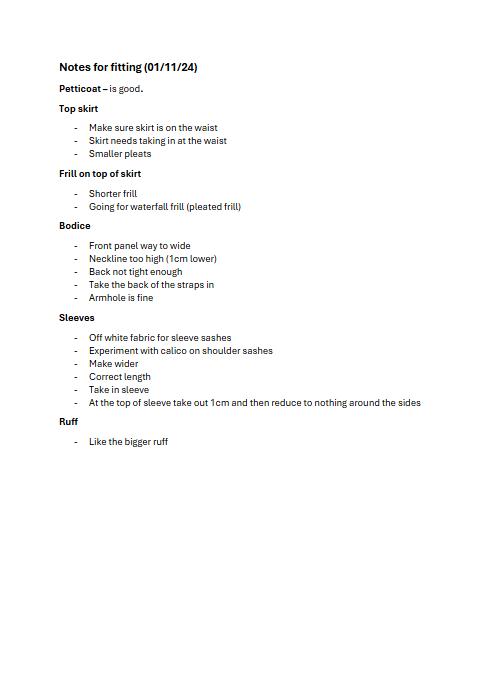

Sarah Astbury

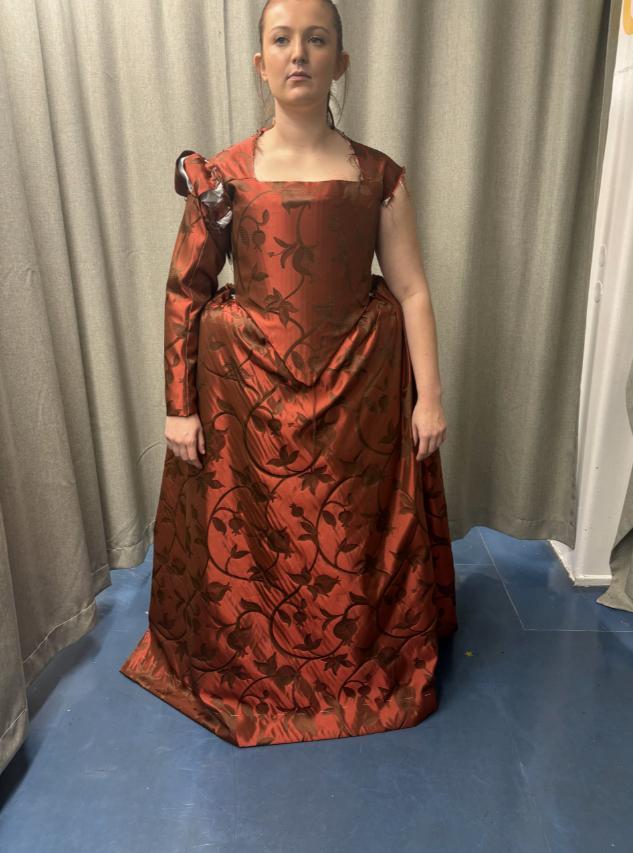

Hester / Margaret Johnson / Mary Sidney

Designs

Hester / Margaret Johnson / Mary Sidney

Figs 47-49: Designs by Bethany Lipscombe

Measurement Sheet

Measurement

Photos

Costume Breakdown

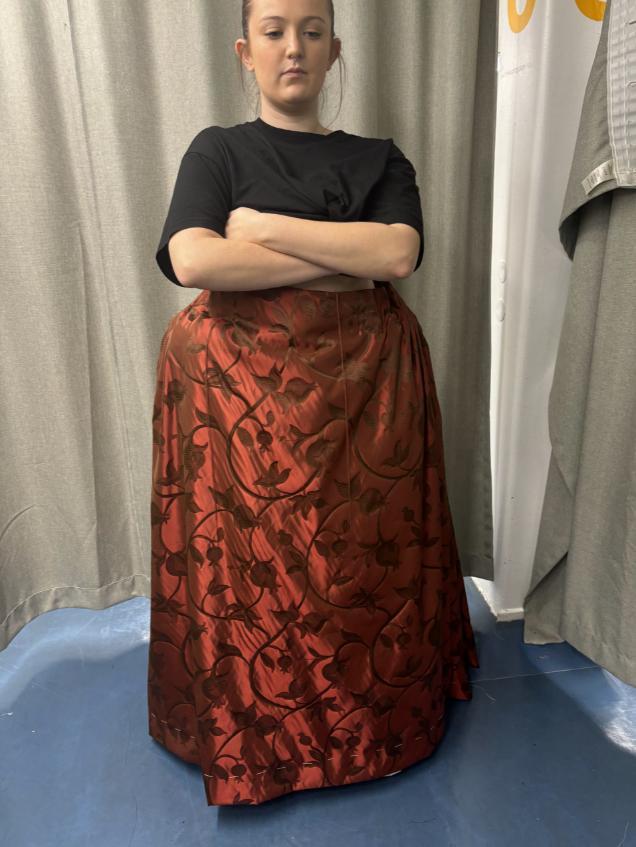

Fittings 1 Before Photos

Fittings 1 After Photos

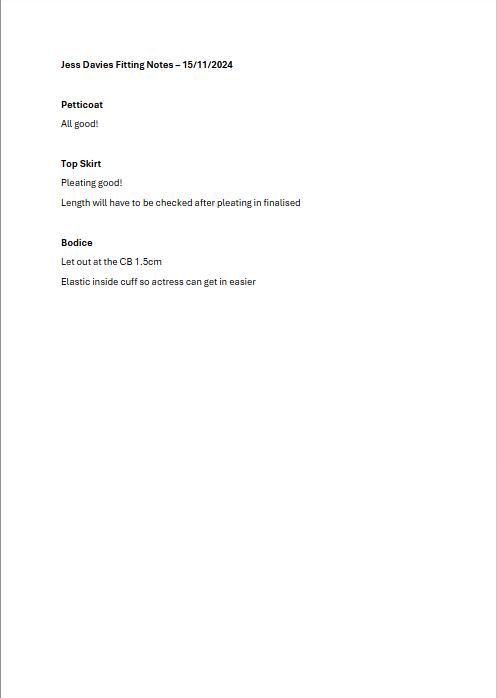

Fitting Notes

Fittings 2 Before Photos

Fittings 2 After Photos

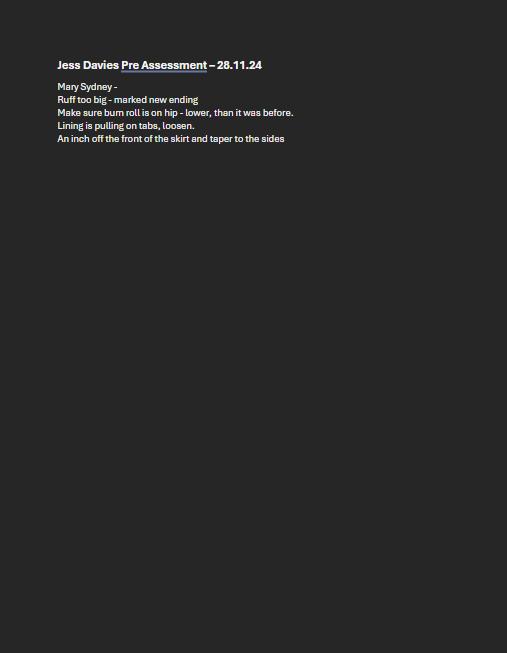

2nd Fitting Notes

Pre-Assessment Photos

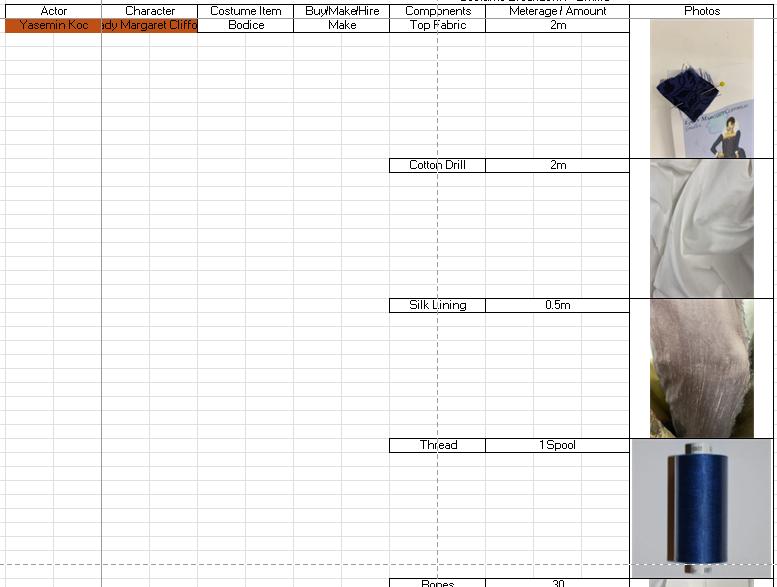

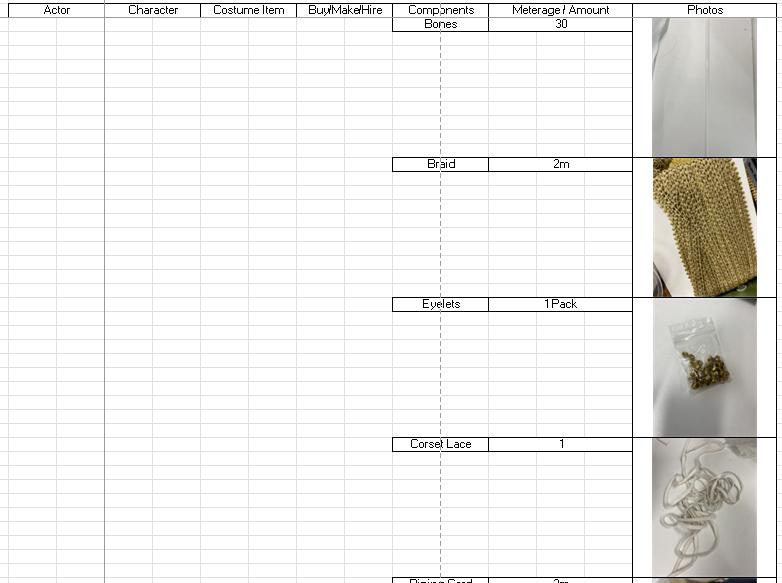

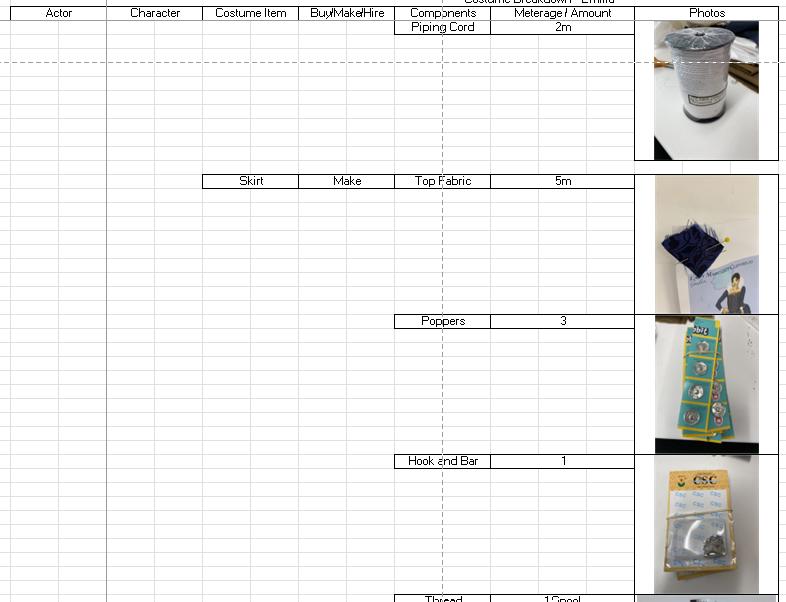

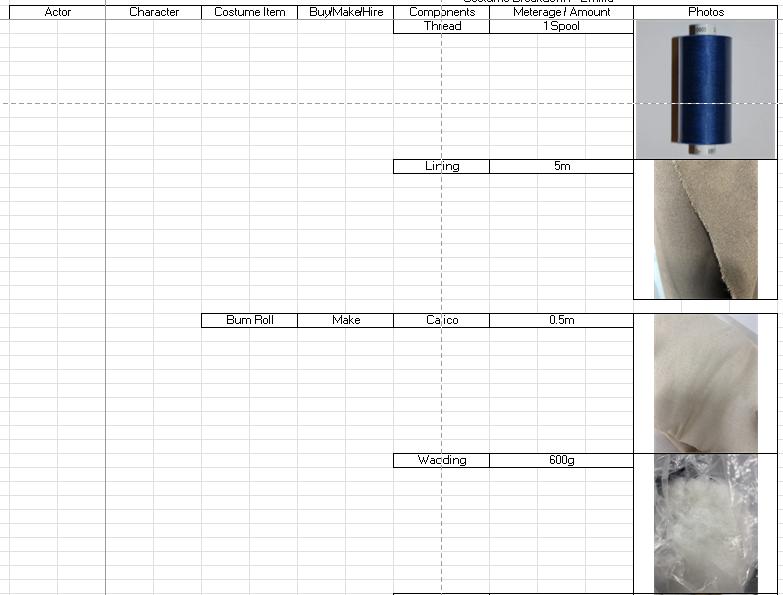

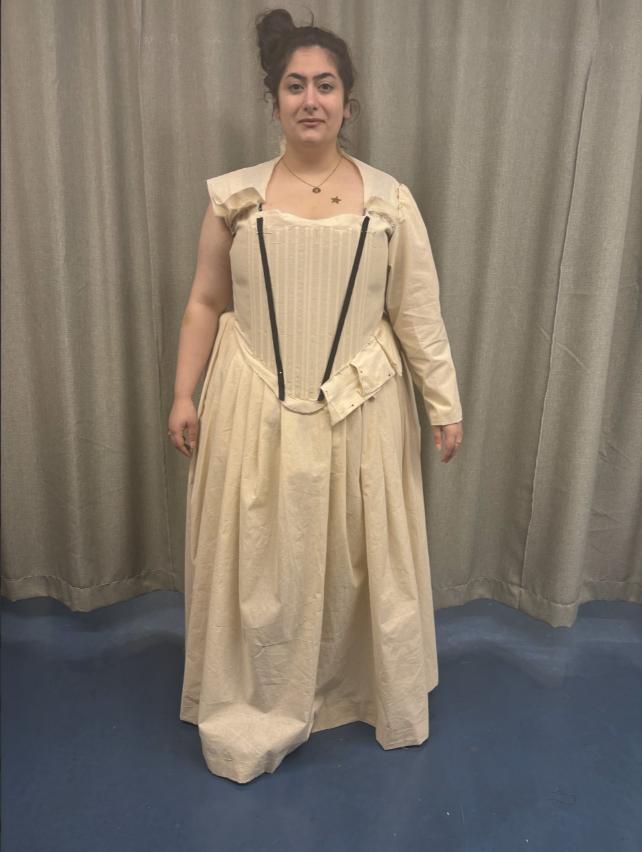

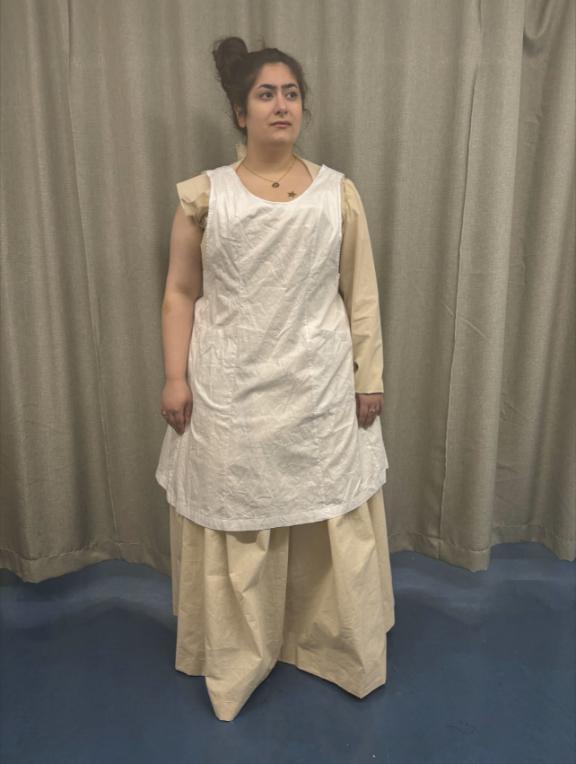

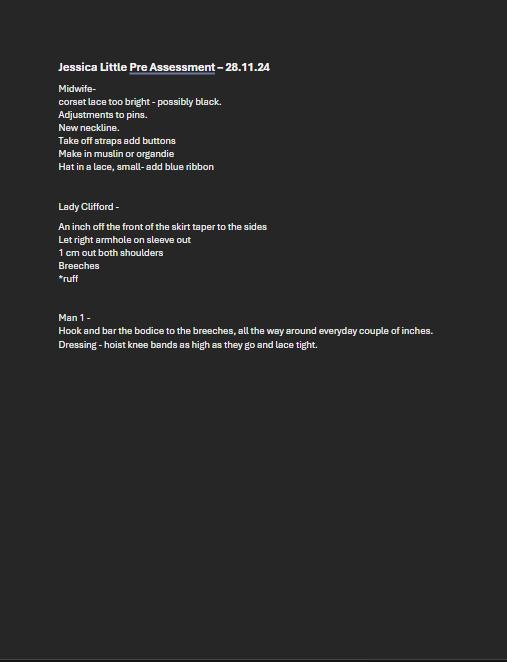

Yasemin Koc

Lady Margaret Clifford / Midwife / Man 1

Designs

Lady Margaret Clifford / Midwife / Man 1

Figs 50-52: Designs by Bethany Lipscombe

Measurement Sheet

Measurement Photos

Costume Breakdown

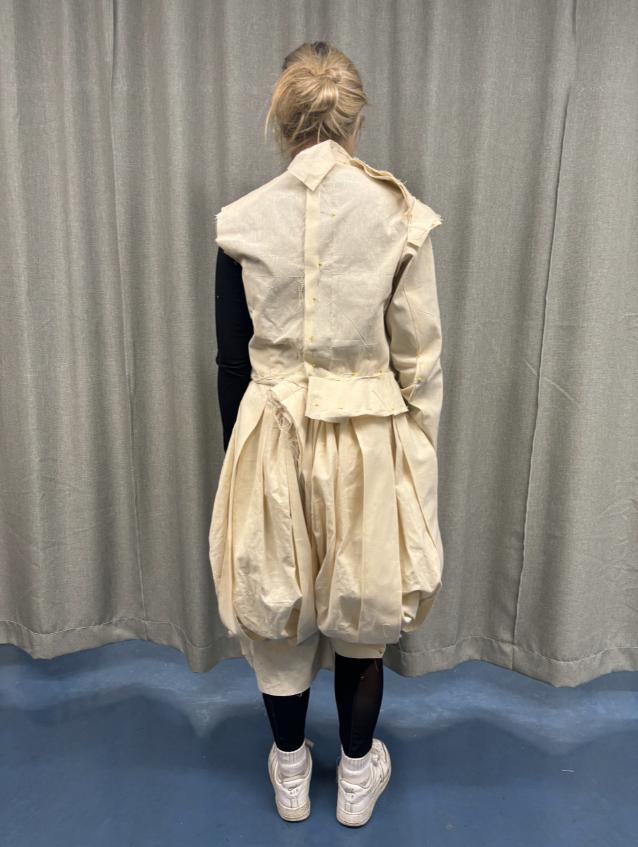

Fittings 1 Before Photos

Fittings 1 After Photos

Fitting Notes

Fittings 2 Before Photos

Fittings 2 After

Photos

2nd Fitting Notes

Pre-Assessment Photos

Costume Plot

Hampshire Wardrobe

Bibliography

Adventures of a Tudor Nerd. (2023). footwear – Adventures of a Tudor Nerd. [online] Available at: https://adventuresofatudornerd.com/tag/footwear/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

American Duchess Blog. (2014). A Quick Look At Late Elizabethan/Early Jacobean Shoes. [online] Available at: https://blog.americanduchess.com/2014/10/a-quick-look-at-late-elizabethanearly.html [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

Anon, (2022). Giving Birth in 17th-century England: A Tentative List - Secrets of Women. [online] Available at: https://juliamartins.co.uk/giving-birth-in-17th-century-england-a-tentative-list.

Balchin, D. (2017). Call the midwife?- pregnacy and childbirth in the 17th century. [online] Dorinda Balchin - Author. Available at: https://dorindabalchin.com/2017/03/07/call-the-midwife-pregnacyand-childbirth-in-the-17th-century/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

Cartwright, M. (2020). Clothes in the Elizabethan Era. [online] World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1577/clothes-in-the-elizabethan-era/.

Digitaltheatreplus.com. (2023). Available at: https://edu.digitaltheatreplus.com/content/productions/othello-frantic-assembly.

Everymanplayhouse.com. (2016). Othello [Frantic Assembly] // Rehearsal Photographs | Liverpool Everyman & Playhouse theatres. [online] Available at: https://www.everymanplayhouse.com/whatsmore/othello-frantic-assembly-rehearsal-photographs [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu. (n.d.). 17th century | Fashion History Timeline. [online] Available at: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/category/17th-century/.

Frantic Assembly. (2014). Othello | Frantic Assembly. [online] Available at: https://www.franticassembly.co.uk/productions/othello.

Gardner, L. (2023). Frantic Assembly’s Othello. [online] Stagedoor. Available at: https://stagedoor.com/theatre-guide/lyn-gardner/frantic-assembly-othello?ia=1339 [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

juliamartins99 (2023). What Made a 17th-Century Midwife Good at Her Job? [online] Living HistoryThe stories of everyday people, brought to life. Available at: https://juliamartins.co.uk/what-made-a17th-century-midwife-good-at-her-job [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

Lynn, E. (2017). Tudor fashion. New Haven: Yale University Press Malcom, M.L. (2021). Emilia. Metheun Drama, p.160.

Onthetudortrail.com. (2024). Available at: https://onthetudortrail.com/Blog/2015/11/28/stitches-intudor-time-a-three-part-series/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024]

Othello. (2023). [Play] Frantic Assembly.

Onthetudortrail.com. (2024). Available at: https://onthetudortrail.com/Blog/2015/11/28/stitches-in-tudor-time-a-three-part-series/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

Penfield, C. (2022). On Being a Midwife in the 17th Century - Carole Penfield. [online] Carole Penfield. Available at: https://www.carolepenfield.com/2022/01/31/on-being-a-midwife-in-the-17th-century/ [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

raisedheels (2014). 1590s Shoes – Elizabeth I from Hardwick Hall | Chopine, Zoccolo, and Other Raised and High Heel Construction. [online] Raisedheels.com. Available at: https://www.raisedheels.com/blog/?p=963 [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

V&A (2024). V&A · From the Collections. [online] Victoria and Albert Museum. Available at: https://www.vam.ac.uk/collections?type=featured.

Victoria (2024). Shoe | Unknown | V&A Explore The Collections. [online] Victoria and Albert Museum: Explore the Collections. Available at: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O107718/shoeunknown/?carousel-image=2020ML2749 [Accessed 10 Dec. 2024].

Watt, M. (2019). English Embroidery of the Late Tudor and Stuart Eras. [online] Metmuseum.org. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/broi/hd_broi.htm.

Figs 1-5: Photographed by Fay Wilde

Figs 6-10: Housed in the National Portrait Gallery, Photographed by Fay Wilde

Fig 11: https://stagedoor.com/theatre-guide/lyn-gardner/franticassembly-othello?ia=1339

Fig 12: https://www.everymanplayhouse.com/whatsmore/othello-frantic-assembly-rehearsal-photographs

Fig 13: https://www.franticassembly.co.uk/productions/othello

Fig 14: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1590-1599/

Fig 15: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O84997/pair-of-glovesunknown/

Fig 16: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1600-1609/

Fig 17: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1590-1599/

Fig 18: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O115772/jacketunknown/

Fig 19: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O16578/queenelizabeth-i-miniature-hilliard-nicholas/

Fig 20: https://fashionhistory.fitnyc.edu/1590-1599/

Fig 21: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O286793/dresstrimming-unknown/

Fig 22: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1547604/coifunknown/

Fig 23: https://www.kci.or.jp/en/featured/

Fig 24: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O318885/ruff-edgingunknown/

Fig 25: https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O137834/supportasseunknown/

Fig 26: https://npgshop.org.uk/products/katherine-villiers-neemanners-later-macdonnell-duchess-of-buckingham-npg-d28084print

Fig 30: https://refashioningrenaissance.eu/exploring-historicalblacks-the-burgundian-black-collaboratory/

Fig 31: https://juliamartins.co.uk/what-made-a-17th-centurymidwife-good-at-her-job

Fig 32: https://juliamartins.co.uk/giving-birth-in-17th-centuryengland-a-tentative-list

Fig 33: https://juliamartins.co.uk/what-made-a-17th-centurymidwife-good-at-her-job

Fig 34: https://www.carolepenfield.com/2022/01/31/on-being-amidwife-in-the-17th-century/

Fig 35: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/lives/biography/the-preserveof-women

Fig 36: https://juliamartins.co.uk/giving-birth-in-17th-centuryengland-a-tentative-list

Fig 37: https://juliamartins.co.uk/what-made-a-17th-centurymidwife-good-at-her-job

Fig 38: Written by Madame Louys Bourgeois

Fig 39-52: Designed by Bethany Lipscombe

CPD

For my CPD I was tasked with sorting buttons into colours and also matching button types. This took me around 10 hours.

I enjoyed sorting the buttons and matching them with their sets, I did however find it frustrating that there was sometimes only one type of button which meant I was forced to put it in a plastic bag on it’s own, which I felt was a waste as there were lots of single buttons.

In the future I’d like to put aside time to get involved with other shows and a wider variety of CPD, I would like to try out dressing for another show or work on alterations.

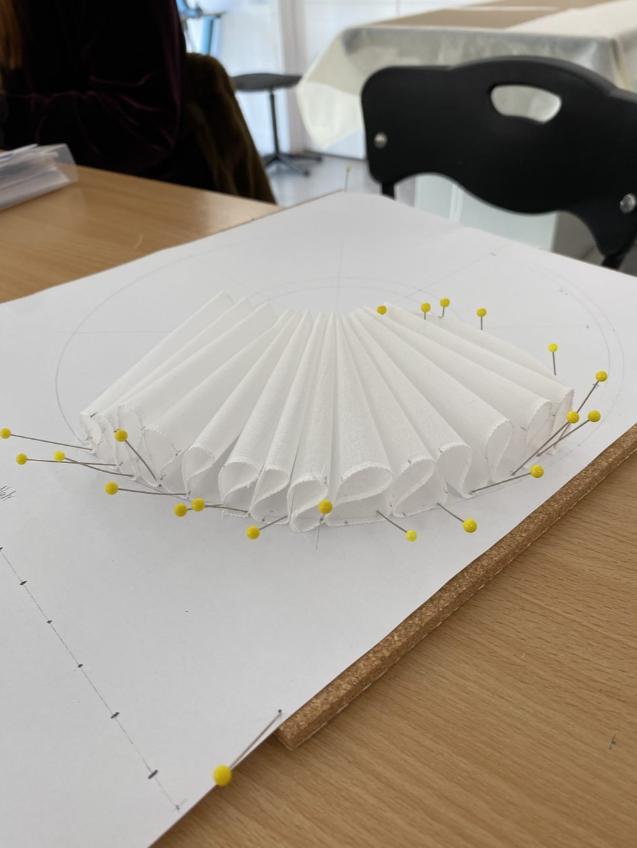

Ruff Workshop

During the term we went through a ruff tutorial with Marija Radojicic. She took us through the steps to make a quarter size sample

First you take Cotton Organdie and tear a 10cm strip, the strip is then ironed and sprayed with starch. The strip is then left to dry for at least 30 minutes.

The strip can then be pleated, either with box or knife pleats, these pleats are kept in place by pins on a cork board where they can be sewn together with a curved needle.

Once all the pleats are stitched together, they are then attached to a length of peplum on the inside of the ruff, this peplum is then covered in a softer material to make the wearer more comfortable.

If desired lace can be added to the ruff, before starching, for added decoration, as well as adding pearls or other jewellery.

For the production of Emilia our makers used lace and strings of pearls for the decoration of their ruffs, as well as this some of our makers used millenary wire to create bigger ruffs, that cant stand under their own weight, to make a bigger spectacle.

I didn’t enjoy the ruff workshop as I found the instructions hard to follow and the ruff making itself fiddly and frustrating. I hope to try making ruffs in the future, possibly with a larger timeframe and clearer instructions.

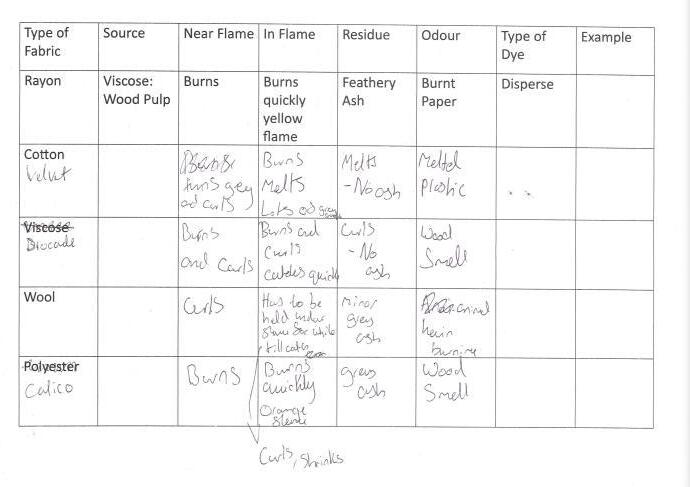

Laundering and Repairs

For the production of Emilia we had to wash and launder at least one pair of tights per actor and fix any issues in the costume, such as fastenings breaking or fabric ripping.

For the washing process we soaked red tights together, purple and blue tights together, and green tights on their own. The tights were then rinsed and put in the spinner, this rinsing and spinning process would be repeated 3 times. The tights would then be left to dry.

Vests and t-shirts that were worn under bodices and doublets are machine washed in lights and darks, they are then left to dry. The same is done for leggings, socks and dress shields, which are removed after every performance.

For the upkeep of bodices, doublets and breeches they were sprayed with a vodka solution and armpits and crotches are gone over with a Fresh-up to help their smell.

Shoes were also cleaned with a toothbrush and soap and water as they pick up the blue paint from the floor of the set.

When it came to repairs, we were mainly fixing fastenings and decorations. We were also tasked with putting in poppers for dress shields and hook and bars for attaching bodices and doublets to breeches and skirts. To stop the torso of the actor from showing during performance.