LEARN. DISCOVER.

EDITORS-IN-CHIEF:

Kristen Ashworth

Kyla Demkiv

Nayaab Punjani

EXECUTIVE EDITORS:

Beatrice Acheson

Jasmine Amini

Alyona Ivanova

Lizabeth Teshler

DESIGN EDITORS:

Ravneet Jaura (Co-Director)

Jinny Moon (Co-Director)

Qingyue Guo

Athena Li

Vicky Lin

Josip Petrusa

Raymond Zhang

SOCIAL MEDIA TEAM:

Lizabeth Teshler (Director)

Lielle Ronen

Abigail Wolfensohn

JOURNALISTS & EDITORS:

Aria Afsharian

Vicky Lin,

Mya Chronopoulos

Sara Corvinelli

Anthaea-Grace Patricia Dennis

Clarize Donato

Ysabel Fine

Grace Gibson

Katherine Guo

Rachel Lebovic

Jino Lim

Eryn Lonnee

Josephine Machado

Sabeeka Malik

Caroline Marr

Eliza McCann

Areej Mir

Anna Mouzenian

Gharaza Nasir

Kinjal Parekh

Karan Patel

Ana Piric

Anita Rajkumar

Gisany Ravichandran

Ankit Ray

Angenelle Eve Rosal

Steven Shen

Rebecca Smythe

Omer Syed

Alicia Tran

Tesam Ahmed

Regina Annirood

Gabriela Blaszczyk

Yalda Champiri

Carmen Chan

Michellie Choi

Serena Trang

Priya van Oosterhout

Shreya Vasudeva

Emily Wiljer

Abigail Wolfensohn

Saleena Zedan

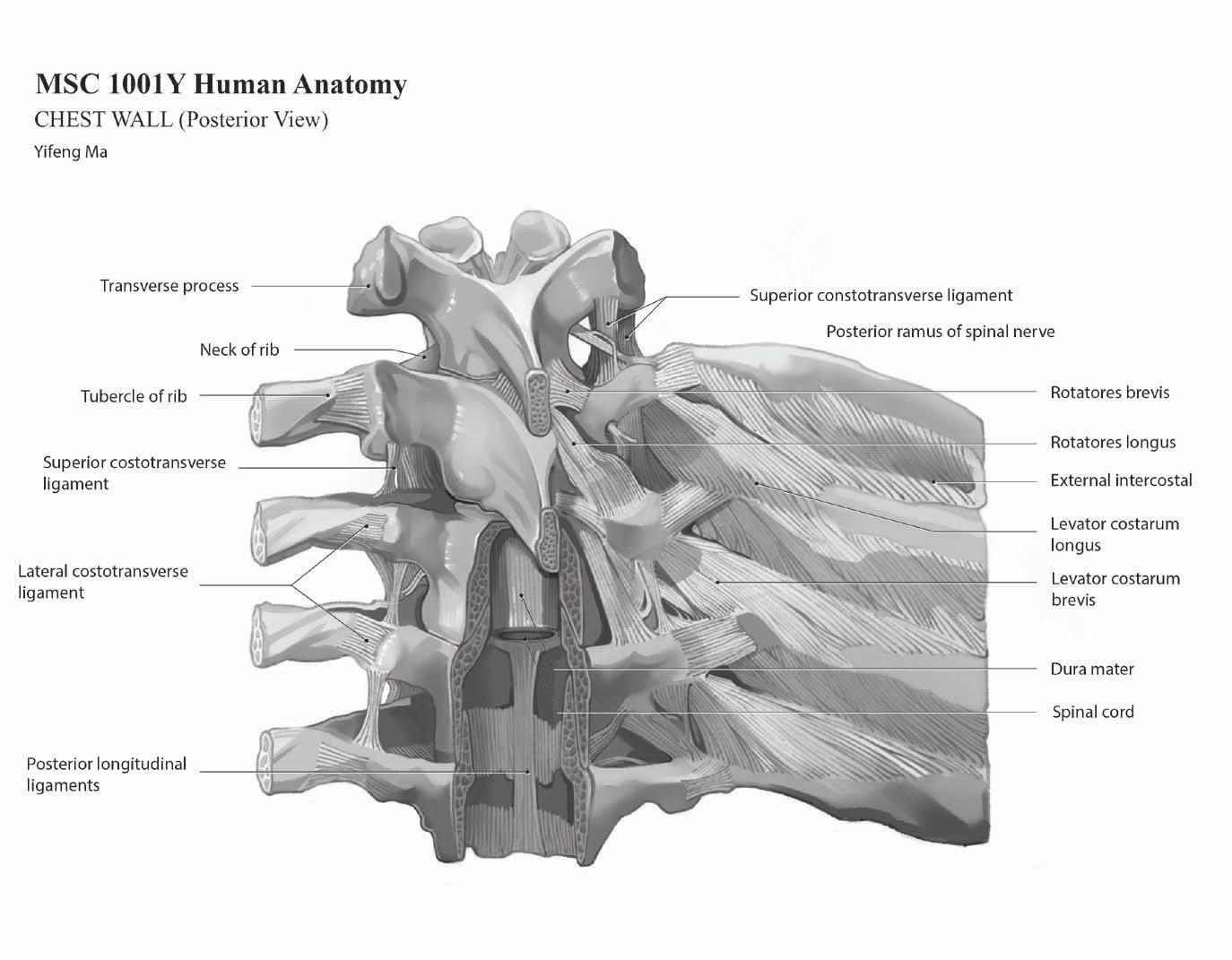

By Qingyue Guo, MScBMC

Happy 2026, IMS!

As we settle in for the winter months and gather momentum for the new year ahead, our Winter Issue of the magazine is doing the same, turning its focus toward a field that never slows down: Emergency Medicine.

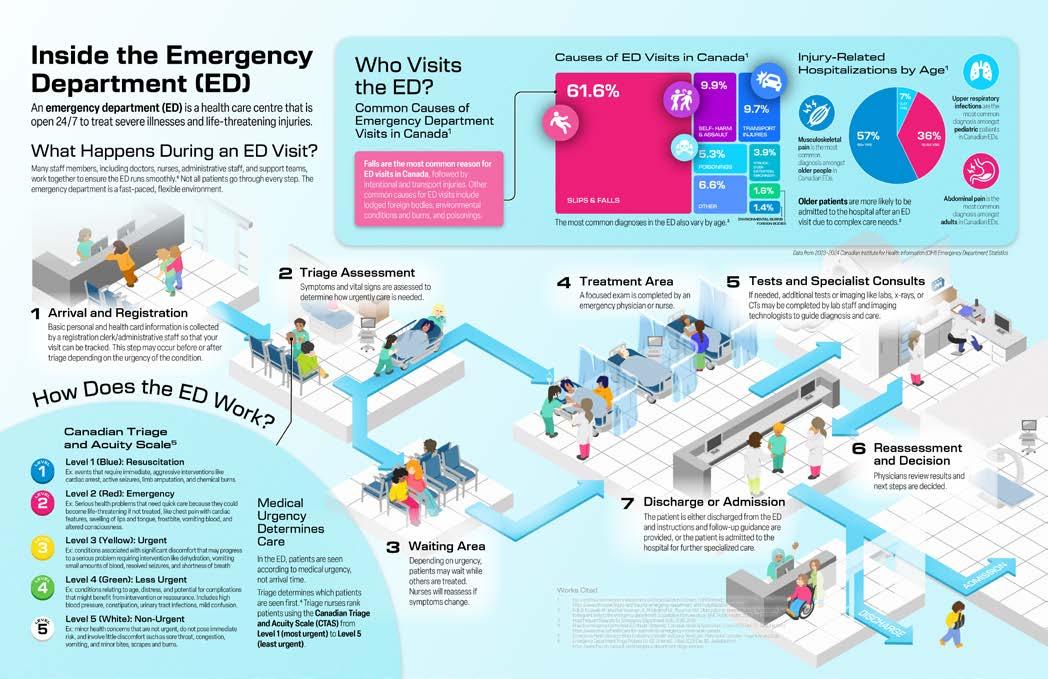

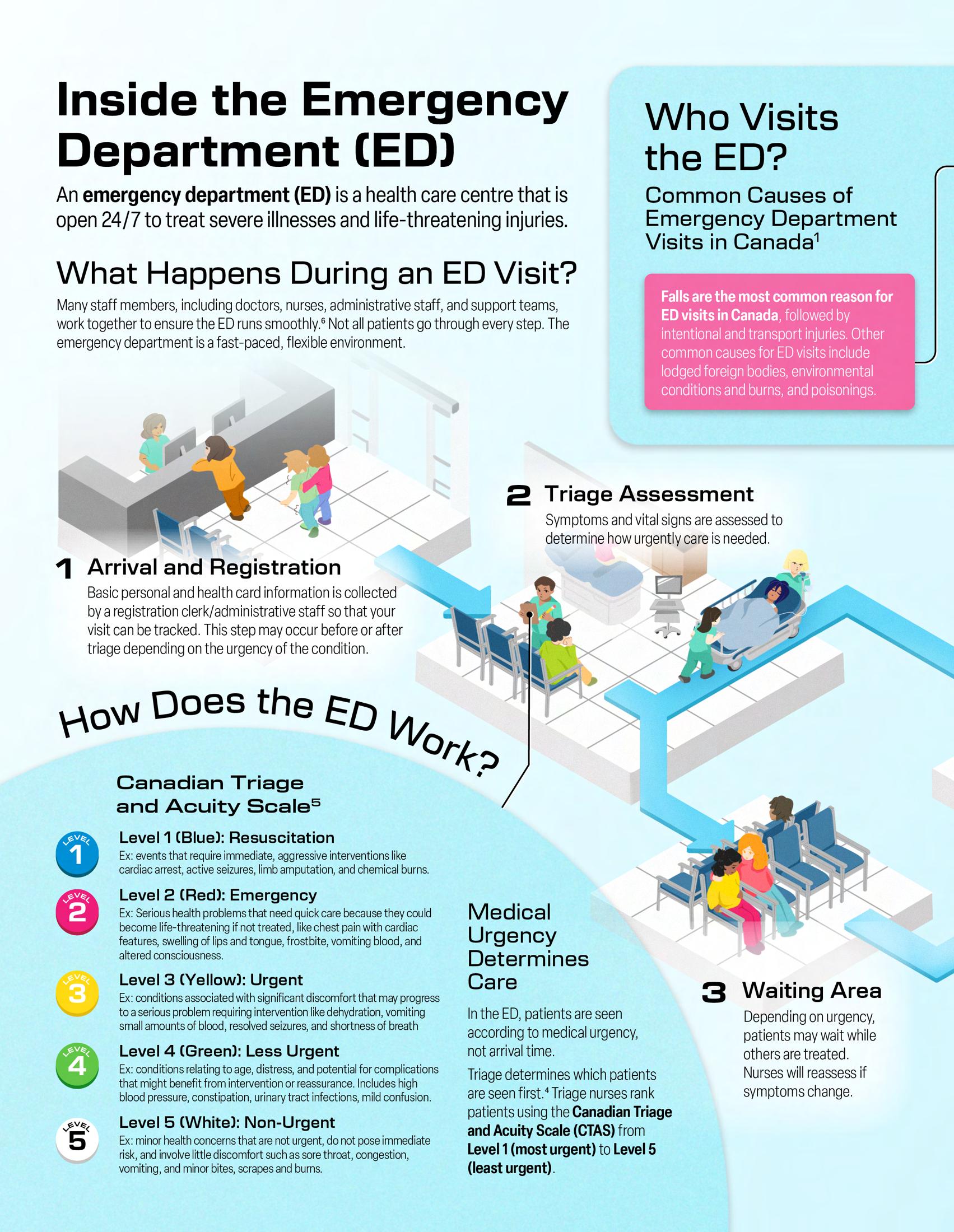

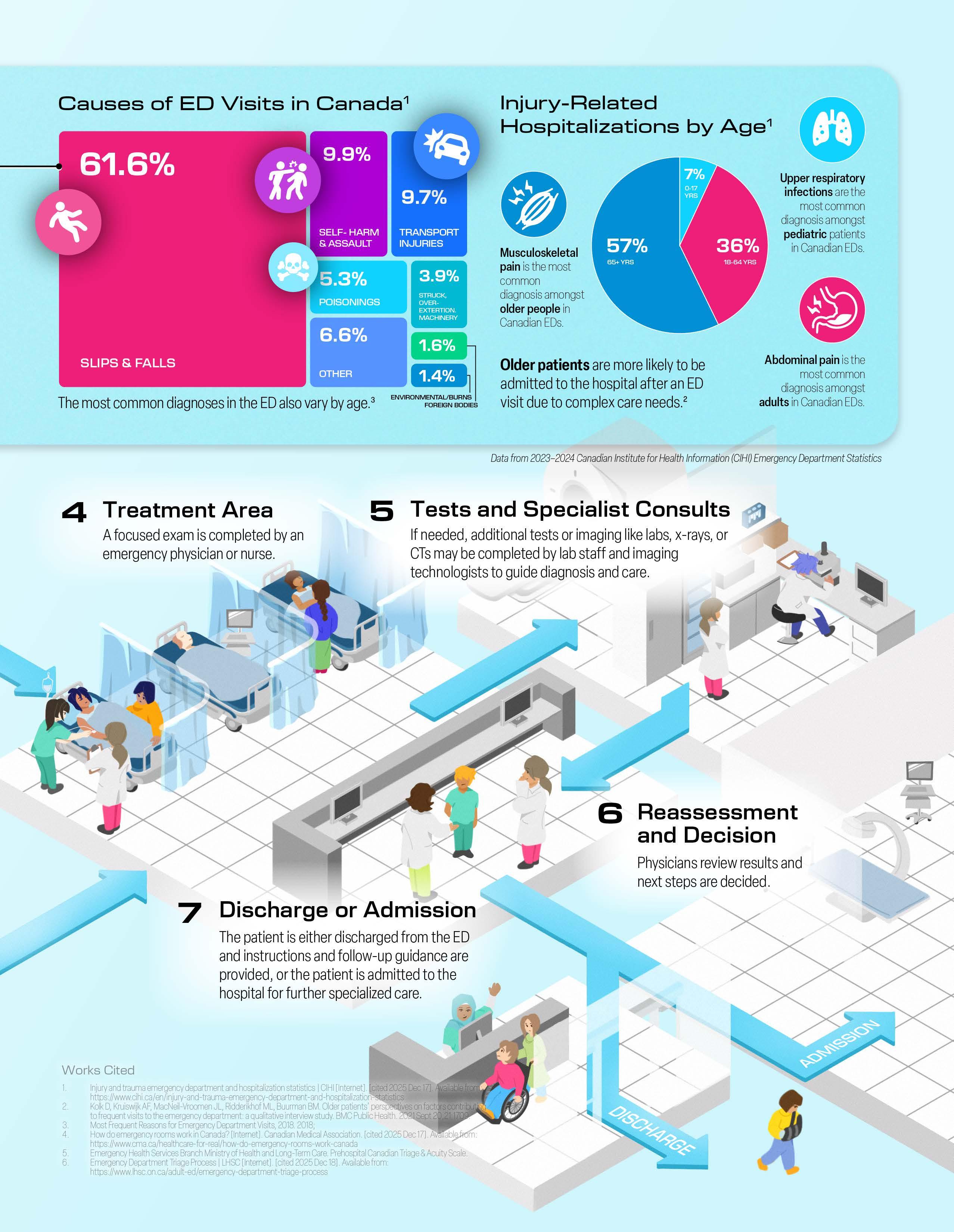

Emergency Medicine spans a remarkable breadth of clinical fields and, in tandem, a remarkable breadth of challenges. These challenges–some of which we are all too familiar with here in Canada–include accessibility to an emergency department (ED), efficient patient triage, prolonged wait times, accurate acute diagnostics, and the delivery of precise care under pressure.

Within the IMS, many of our faculty, whether in research, in clinical practice, or both, are navigating these complexities every day to improve evidence-based outcomes for patients of all backgrounds coming through the ED.

In this issue, we feature faculty whose work spans many different avenues of Emergency Medicine research. Dr. Jacques Lee is investigating the impacts of delirium and loneliness on the geriatric population in the ED; Dr. Muhammad Mamdani is harnessing the power of AI to improve wait times and system-wide efficiency in the ED; and, Dr. Brodie Nolan is studying the use of prehospital and transfusion protocols to improve trauma survival.

Our viewpoint articles broaden the conversation even further, covering important and diverse topics that are relevant and growing in the field of Emergency Medicine today: pain management in the ED; the use of synthetic platelets for trauma healing; the rural emergency care crisis across Canada; the impact of the youth mental health crisis on EDs; worsening emergency wait times; the ethical integration of AI in the ED; and even featuring a new ED peer-support program right here at Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto.

In addition, this issue’s spotlight pieces highlight the achievements of some outstanding members of the IMS community–including faculty member Dr. Liisa Galea; students Mariam Elsaway and Shannen Kyte; alumnus Dr. Aravin Sukumar; and staff member Caroline Ruvio.

As always, we are grateful for our journalists, editors, and designers for bringing this issue, like every issue, to life. We hope this Winter Issue inspires deeper curiosity and reflection with the pressing questions and fast-moving world that define Emergency Medicine today.

Sincerely,

Kristen is a PhD student studying the use of a human-based retinal organoid model to investigate cell therapies for genetic eye disease under the supervision of Dr. Brian Ballios at the Krembil Research Institute.

@K_Ashworth01

Kyla Demkiv

Kyla is a PhD student studying the mechanism of action of novel therapies for lymphoma under the supervision of Dr. Armand Keating, Dr. John Kuruvilla, and Dr. Rob Laister.

@kylatrkulja

Nayaab Punjani

Nayaab is a PhD student examining a neuroprotective drug therapy for cervical-level traumatic spinal cord injury at the Krembil Research Institute under the supervision of Dr. Michael Fehlings.

@nayaab_punjani

Dear IMS Community,

I hope you were all able to have a restful holiday. On behalf of all the core staff at IMS, I would like to warmly welcome you to 2026! This IMS Magazine issue on Emergency Medicine pays tribute to the physicians and scientists who are working tirelessly to improve front-line access to care across various patient populations and research areas.

This issue features three faculty examining various facets of emergency care delivery to enhance patient-centred care. Dr. Jacques Lee is moving beyond the stigma to enhance care within the field of geriatric emergency medicine through better screening for delirium and loneliness. Dr. Muhammad Mamdani is navigating ethical and practical implications for implementing artificial intelligence within the emergency department— developing tools that include improving triage, nurse scheduling, and vital signs monitoring. Finally, Dr. Brodie Nolan is optimizing early-access transfusion protocols to improve trauma survival.

In addition to faculty, this issue places a spotlight on multiple IMS community members. The faculty spotlight is Dr. Liisa Galea who speaks about her journey as a researcher and her advocacy work within the field of women’s health. Mariam Elsawy and Shannen Kyte, co-recipients of the Jay Keystone Award, share the student spotlight for their initiative MedComics Con which will occur in Spring 2026, and Dr. Aravin Sukumar, alumnus of IMS, explains his transition to the field of scientific communications from academia. This issue also places a special staff spotlight on Caroline Ruivo, Executive Assistant to the Director and Faculty Affairs Administrator, speaking about the intersection of art and science and showcasing her own artwork. Finally, this issue highlights the 2025 Ori Rotstein Lecture in Translational Research by Dr. Karen Reue, which focused on how sex chromosomes and hormones shape health and disease in different ways.

I am extremely proud of the tremendous work the IMS Magazine team of journalists, editors, photographers, and designers contribute to prepare each iteration of the IMS Magazine. I would like to particularly commend the Editors-in-Chief Kristen, Kyla, and Nayaab, as well as Design Team Co-Directors Jinny and Ravneet for their collaborative guidance and leadership in putting this issue together.

Wishing everyone the very best in the New Year, and I hope that the articles in this issue will serve as inspiration as we work towards improving patient care within translational emergency medicine.

Sincerely,

Dr. Lucy Osborne Interim Director, Institute of Medical Science

Beatrice Acheson is a second-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Peter St George-Hyslop at the Tanz Centre for Research in Neurodegenerative Disease, where she investigates the genetic and molecular mechanisms underlying microglial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. In addition to her research, Beatrice enjoys trivia and solving the New York Times Crossword Puzzle.

@bea.acheson

Jasmine Amini is a second-year MSc student working under the supervision of Drs. Daphne Korczak and Samantha Anthony at the Hospital for Sick Children. Her research interests lie in social media use and family functioning among youth with an acute self-harm or suicide-related concern. Outside of academia, Jasmine enjoys reading, volunteering, and exploring Toronto.

@Jasmine_amini9

Regina Annirood is a PhD student working under the supervision of Dr. Robert Chen at Toronto Western Hospital. Her research focuses on how transcranial ultrasound stimulation can modulate brain circuits to improve symptoms in people with Parkinson’s disease, contributing to advances in the understanding and treatment of movement disorders. Outside the lab, she enjoys travelling, pilates, reading, and spending time with family and friends.

Michellie Choi is a firstyear MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Kazuhiro Yasufuku at the Latner Thoracic Research Laboratories and Toronto General Hospital (UHN). Her research focuses on AI applications for minimally invasive thoracic surgery and surgical guidance.

Mya Chronopoulos is a first-year MSc student supervised by Dr. Caleb Browne at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health where she is exploring how serotonin and dopamine coordinate in the mesolimbic dopamine system to shape motivation/rewardseeking behaviour. Outside of the lab, she enjoys early morning pilates classes, spending time with family, and traveling.

@myachronopoulos

Sara Corvinelli is a PhD student supervised by Dr. Jacques Lee at the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute. Her thesis is exploring innovative ways to improve delirium recognition for older people who seek emergency care. When she’s not researching, Sara enjoys ballet, nature walks, and spending time with loved ones.

Grace Gibson is a second-year MSc student in the Biomedical Communications program studying to become a medical illustrator. She aims to work in patientfacing media and outreach focused on the LGBTQ community. In her free time, Grace enjoys reading books and painting.

Alyona Ivanova is a PhD student investigating the molecular signature of glioblastoma using spatial -omics technologies at the Hospital for Sick Children under the supervision of Dr. Sunit Das. Alyona is a professional figure skater and a model. Alyona is a Creative Director of Panoramics - A Vision Inc. She enjoys traveling, cooking, and reading.

@_alyonaivanova_

Rachel Lebovic is a second-year PhD student at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre under the supervision of Dr. Mark Sinyor. She is studying suicide prevention through popular media as a tool to teach mental health literacy to youth. Outside of research, Rachel enjoys cooking, going for walks, and building Lego.

@rachel.lebovic

Josephine Machado is a second-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Andrea Knight at The Hospital for Sick Children. Her research is focused on examining the neuropsychiatric impacts of childhoodonset systemic lupus erythematosus (cSLE) through the study of brain-aging in children with the condition. Outside of research, Josephine enjoys reading, playing the piano, nature walks, and volunteering.

Sabeeka Malik is a second-year MSc student at the SickKids Research Institute, working under the supervision of Dr. Andreas Schulze. Her research aims to determine effective substrate reduction therapy drug candidates for Mucopolysaccharidosis III (Sanfilippo Syndrome), a lysosomal storage disease. Outside of the lab, Sabeeka enjoys reading and playing card games with her friends.

Areej Mir is a first-year MSc student at Women’s College Hospital. Her research focuses on studying disparities in breast cancer treatment and care among immigrants in Ontario. She has a strong passion for health-equity focused research. She is thrilled to be a part of the IMS Magazine, helping to share stories that make health research more accessible and engaging for all audiences. Outside of academics, she enjoys volunteering in her community, exploring Toronto’s food scene, and curating creative content online.

Anna Mouzenian is a second-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Victor Tang and Dr. Daniel Felsky at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. Anna is investigating the use of wearable devices to predict outcomes for substance use disorders. In her free time, she enjoys dancing, hiking and pilates.

Gharaza Nasir is a second-year MSc student at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute, working under the supervision of Dr. Arndt Vogel. Her research utilizes patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models to investigate tumour dynamics and evaluate potential therapeutic strategies for Cholangiocarcinoma. In her free time, Gharaza enjoys working out, playing video games, and spending time with friends and family.

@g.harazanasir

Kinjal Parekh is a firstyear MSc student at St. Michael’s Hospital, working under the supervision of Dr. Andras Kapus. Her research is focused on uncovering the mechanism of a novel inhibitor targeting the YAP/TAZ transcription factors, central regulators whose overactivation drive cancer and fibrosis. Outside of research, she enjoys cooking, playing badminton, and nature walks.

@kinjalparekh09

Ana Piric is a secondyear MSc student at the Princess Margaret Cancer Research Tower working under the supervision of Dr. Aaron Schimmer. Her research is focused on the molecular targeting of the mitochondrial protease LONP1 in cellular and mouse models of acute myeloid leukemia (AML). In her free time Ana enjoys yoga, reading, and exploring the food scene in Toronto!

@anapiric18

Anita Rajkumar is a second-year MSc student at Women’s College Hospital, working under the supervision of Dr. Joanne Kotsopoulos. Her research aims to understand hormonal contraceptive use and breast cancer risk among BRCA carriers. In her free time, Anita enjoys reading, running, and trying new restaurants.

@anita.raj_

Rebecca Smythe is a first-year MSc student at Women’s College Hospital working under the supervision of Dr. David Lim. Her research aims to better understand the lived experiences of transgender and gender diverse (TGD) individuals navigating breast cancer care, across the entire care continuum from screening to survivorship. Outside of her work Rebecca enjoys reading, travelling, and spending time with loved ones.

@beckyysmythe

Alicia Tran is a first-year MSc student working under the supervision of Dr. Lihi Eder at Women’s College Hospital. Her research explores sex differences in response to advanced therapies in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Outside of the lab, she enjoys exploring Toronto with her sister, vintage shopping, and baking new recipes for the holiday season.

@aliciaxtran

Shreya Vasudeva is a first-year MSc student at the Poul Hansen Family Centre for Depression under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Rosenblat. Her research focuses on investigating the abuse liability of ketamine when prescribed for treatment-resistant mood disorders. Outside of research, Shreya loves movies, spending time with family and friends, trying new cafes around the city!

Saleena Zedan is a second-year MSc student at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, being supervised by Dr. George Foussias. Her research is focused on investigating the role of gender-identity and socioenvironmental variables in predicting recovery outcomes for individuals with psychosis. Saleena enjoys spending time with her family, friends, and dog outside of her work.

Aria Afsharian

Tesam Ahmed

Gabriela Blaszczyk

Yalda Champiri

Carmen Chan

Anthaea-Grace Patricia Dennis

Clarize Donato

Ysabel Fine

Katherine Guo

Jino Lim

Eryn Lonnee

Caroline Marr

Eliza McCann

Karan Patel

Gisany Ravichandran

Ankit Ray

Angenelle Eve Rosal

Steven Shen

Omer Syed

Serena Trang

Priya van Oosterhout

Emily Wiljer

Abigail Wolfensohn

Lizabeth Teshler (Lead) is a PhD student supervised by Dr. Brian Feldman at The Hospital for Sick Children. Her research investigates how to improve the clinical examination of musculoskeletal health for people with Hemophilia. Outside of research, she loves biking, spending time outdoors, and exploring new cities.

Lielle Ronen is a secondyear MSc student in Dr. Andrew Sage’s Lab at the Latner Thoracic Surgery Research Labs in PMCRT. Her research investigates smoking damage in donor lungs to improve post-transplant outcomes using Ex-Vivo Lung Perfusion (EVLP). Aside from research, she loves painting, baking, running and trying local restaurants in Toronto.

Abigail Wolfensohn is a second-year MSc student in Dr. Mojgan Hodaie’s lab at Toronto Western Hospital. She is researching how the brain’s waste-clearance system functions in people with trigeminal neuralgia, a chronic facial pain condition. In her free time, she enjoys outdoor activities, puzzles, trying new restaurants, and playing the piano.

@abbywolfen

The IMS Design Team is a group of 2nd-year MSc students in the Biomedical Communications (BMC) program. Turning scientific research into compelling visualizations is their shared passion, and they are thrilled to contribute to the IMS Magazine.

Ravneet Jaura (Co-Director) ravneetjaura.com

Jinny Moon (Co-Director) jinnymoon.ca

@artby_reetu @jmoon.vis

@athna.stomosis @qiy_o_0 liathena101.wixsite.com/portfolio

@viyxlin @jpetrusavisuals

Josip Petrusa josippetrusa.com

Raymond Zhang helloimraymond.github.io

@rayz_the_roof

By Sara Corvinelli

“Unless you’re a paediatrician or an obstetrician, you’re a geriatrician,” says Dr. Jacques Lee, an emergency physician at Mount Sinai Hospital and Research Chair in Geriatric Emergency Medicine (GEM) at Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute (SREMI). The field of GEM aims to address the unique and unmet needs of older people who seek emergency care.1 With a growing aging population, patients 65 years and older account for over 25% of all Emergency Department (ED) visits in Canada as of 2014.2 The future of emergency medicine demands attention to how well we care for this older population.

Older people are especially vulnerable to complex care challenges, including falls, delirium, and loneliness, but they are often overlooked in a fast-paced ED. While our population continues to age, the significant demographic shift termed the “Silver Tsunami” is imminent in emergency care. To address this, leaders in GEM are working towards novel solutions and advocacy for age-friendly practices in the ED. Dr. Lee’s research program encourages slowing down and recognizing the person behind the patient.

Dr. Lee’s path to improving emergency care for older people was shaped by clinical insight and research training. He pursued his medical education at the University of Alberta and completed a residency in emergency medicine at McGill University. Following this, Dr. Lee

began his scientific career at Sunnybrook Hospital, where he conducted research in management and measurement of acute pain. In his clinical practice, he noticed the shifting demographics in the ED—a rising number of seniors—and recognized a growing need to further optimize the merging of emergency and geriatric care. In 2018, he joined Sinai Health and was named the Inaugural Research Chair in GEM at SREMI.

Dr. Lee’s research stands on two key pillars, both of which are rooted in the context of caring for aging adults in the ED. The first explores delirium, a serious and common condition characterized by a sudden change in mental state. Delirium is underrecognized by ED staff despite its association with a three-fold increased risk of death.3 The second examines social isolation and loneliness, a crisis that impacts both mental and physical health of older adults, as loneliness is “just as bad for you as smoking a pack of cigarettes a day,” Dr. Lee says.4 Delirium and loneliness can be lethal, but are often overlooked as they present with less obvious, more insidious symptoms than other afflictions in the ED.

Delirium affects around 12% of older people who seek care at Canadian EDs.3 It is associated with prolonged hospitalization, loss of independence, and increased risk of cognitive decline and mortality.3 However, delirium remains poorly understood by researchers and

clinicians. “After 400 years, no one knows what’s actually going on in the brain when you have delirium,” Dr. Lee says. The real breakthrough lies in understanding what causes delirium, and finding a test that provides an objective diagnosis, thereby increasing recognition rates.

In pursuit of this breakthrough, Dr. Lee is investigating biomarkers and measurable changes in the body that provide insights into a person’s health. To do so, Dr. Lee and his team are analyzing urine samples of older adults with hip fractures who are at risk of delirium. Urine samples were collected in the ED at baseline, then twice daily to track delirium development. Dr. Lee aims to identify changes in metabolites associated with the onset of delirium in hopes of enhancing our current understanding of the underlying pathophysiology. Discovery of biomarkers associated with delirium onset may enable the development of diagnostic tools for earlier recognition of delirium in the ED.

In parallel to understanding what causes delirium, there is a dire need to improve its prompt recognition. “The best delirium recognition rate in the emergency department is 50%. If your child brings that report card home, you don’t put it up on the fridge,” says Dr. Lee. To address this, his research team is conducting a multi-centre prospective cohort study, called Better ED Delirium Recognition (BEDDeR), which will compare innovative

Dr. Jacques Lee MD, MSc, FRCPC Emergency Physician, Mount Sinai Hospital Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine (SREMI) Research Chair, Geriatric Emergency Medicine Associate Professor, University of Toronto

strategies to recognize delirium in the ED, including the use of tablet games and hospital volunteers administering a simple screening tool. The findings will support the creation of solutions to improve delirium recognition rates. “We must move past, ‘delirium recognition is terrible,’ to, ‘let’s start improving it’,” Dr. Lee emphasizes.

In addition to Dr. Lee’s research on delirium, while at the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic, he witnessed the emerging crisis of loneliness in elderly patients. Dr. Lee recounts the story of

We know how to measure blood pressure and pain, but not loneliness. “ “

an older patient who was brought to the ED by ambulance from an assisted living home. He vividly recalls the patient’s stark words: “He looked at me and said, ‘Don’t send me back, doctor. I’m dying of loneliness.’” Dr. Lee realized that social isolation and loneliness are profoundly underappreciated social determinants of health. This inspired the formation of his “How-RU” program of research. Patients recently discharged from the ED that experience social isolation in their current living situation are connected with hospital volunteers for weekly conversations on the phone or via video call. The program addresses loneliness among older patients, and through sub-studies Dr. Lee hopes to advance the development of evidencebased, practical tools to identify social isolation and loneliness.

Whether screening for delirium or loneliness, it is crucial to recognize that older patients are people with stories, not just medical conditions. The ED is prone to the “blue gown effect”, where “[…] an older person shows up, they’re wearing a blue gown, and they all look the same. You don’t know this person is a retired CEO and still active on their board of directors. You lose all that context. That’s what leads to mistakes,” Dr. Lee says. He looks forward to ushering in a new era of person-centred care for older people in the ED.

Dr. Lee is working toward a future where loneliness screening is routine and

delirium recognition rates improve with the use of new tools and cultural change. He hopes, “In the future, asking about loneliness in the ED will be as normal as asking [older patients] if they smoke.” The possibilities are in reach, and Dr. Lee believes that someday, we will “reach a point where we can just dip a urine test strip and know a patient has delirium or is about to get it. That would be a huge step forward.”

To ensure lasting progress, Dr. Lee is passing the torch to the next generation and encouraging more physicians to participate in GEM research. His mission is to make compassionate, evidence-based care for older adults the norm, not the exception. He envisions people saying, “Of course we needed to improve care for older people. It was horrible what we did before.” There may be resistance to change, but the evidence is clear. Dr. Lee hopes for a turning point when screening for delirium, asking about loneliness, and recognizing the person behind the patient become “so obvious that nobody even thinks twice— like washing your hands.”

References

1. Melady D, Schumacher JG. Developing a Geriatric Emergency Department: People, Processes, and Place. Clin Geriatr Med. 2023;39(4):647-58.

2. Latham LP, Ackroyd-Stolarz S. Emergency department utilization by older adults: a descriptive study. Can Geriatr J. 2014;17(4):118-25.

3. Kakuma R, du Fort GG, Arsenault L, et al. Delirium in older emergency department patients discharged home: effect on survival. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):443-50.

4. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):227-37.

By Anna Mouzenian

When Dr. Muhammad Mamdani reflects on what first drew him to artificial intelligence, he recalls a simple but powerful thought: Wouldn’t it be great if a computer could look at 100,000 patients and based on learnings from these patients, tell me what to do for the one patient sitting in front of me? It’s a question that resonates strongly in the emergency department (ED), where real-time decision-making is essential.

A pharmacist by training with degrees in econometric theory and statistics, Dr. Mamdani has built a career around turning this thought into reality. As Director of the Temerty Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research and Education in Medicine (T-CAIREM) and Clinical Lead – AI for Ontario Health, he is helping to redefine evidence-based medicine for the era of big data and bringing artificial intelligence (AI) out of the lab and into clinical spaces like the ED.

Dr. Mamdani’s journey in AI began when he realized that the evidence supporting conventional clinical decision making often reflects an idealized patient sample rather than the people physicians actually treat, leaving doctors to apply sample-level averages to unique individuals. With the rise of AI, the possibility to draw on largescale clinical data to support individualised decision-making is within reach.

Few places illustrate the potential of AI more clearly than the fast-paced and complex world of emergency medicine,

where even small gains in speed or accuracy can save lives. The pace of the ED, he says, demands systems that operate in real time. “In trauma care, you can’t have an algorithm that runs every hour. It has to run every second,” Dr. Mamdani says. Previously, Dr. Mamdani was the Vice President of Data Science and Advanced Analytics at Unity Health Toronto. St. Michael’s Hospital, part of Unity Health Toronto, provides an ideal setting for these AI solutions, given its commitment to advancing artificial intelligence in healthcare and its status as one of only two Level I trauma centres in Toronto.

Several AI technologies are already reshaping the clinical space. Dr. Mamdani and his multidisciplinary team have developed over 50 AI-driven tools designed to make hospitals safer and more efficient. One of the best-known is CHARTWatch, an AI tool at St. Michael’s Hospital which continuously monitors patient data such as vital signs, lab results, and nursing notes, assessing between 150 and 170 parameters every hour to flag those at risk of unexpected death or transfer to an intensive care unit (ICU).1 Though currently used in the General Internal Medicine Ward as well as the General Surgery unit, tools like CHARTWatch hold great promise for the ED, where delayed transfer of critically injured patients to the ICU results in higher hospital length of stay and increased mortality.2

Additionally, AI scribes, now being tested in Canada and abroad, generate automated medical notes by listening

to clinician–patient conversations. At Michael Garron Hospital, for example, the introduction of an AI transcribing tool enabled emergency physicians to see 10 to 13 percent more patients per shift and spend up to two fewer hours per shift on documentation, contributing to shorter wait times and reduced administrative burden.3 Tools like these could solve massive problems facing Canadian EDs, which are plagued by overcrowding, long wait times, and physician burnout.4,5

The impact of these tools is also evident in a nurse-assignment system developed at St. Michael’s Hospital. The system reduced the time from 3 hours per day to under 15 minutes, while cutting error rates from over 20 percent to under 5 percent. Another project, ASIST-TBI6, which is currently deployed in the St. Michael’s ED, is an AI algorithm that analyzes CT scans in under 2 minutes to identify whether there is need for immediate surgical intervention as opposed to medical management, with accuracy comparable to that of neurosurgeons. In suspected stroke or traumatic brain injury, delays in identifying brain bleeds may mean the difference between recovery and death.7 Such rapid and reliable tools represent a transformational shift in care.

Though in the early phases of deployment, technologies like these could elevate emergency care by enabling AI-assisted triage, flagging urgent cases, or ordering imaging before a physician even arrives. These innovations succeed, he says, because

clinicians help build them. Instead of delivering ready-made software, his group begins by asking front-line teams, like ED physicians, what problems they most want solved. “Everybody buys in because we built the solution together,” he says.

As AI tools become increasingly prevalent in clinical care, they introduce ethical tensions that are especially acute in the ED, where decisions must be made quickly, and often without complete information. The reach and ability of these tools necessitate responsibility, and Dr. Mamdani is candid about the gray zones that accompany medical AI. One algorithm designed by his team, which identifies structurally vulnerable people who use intravenous drugs and are at high risk of death, has never been deployed despite achieving over 80 percent accuracy. Patient interviews revealed discomfort with being flagged without consent and concerns

about the stigma associated with addiction, underscoring the importance of trust and patient autonomy in AI-supported care.

Bias in AI decision-making presents another major challenge. Race data is rarely collected in Canadian hospitals, but omitting it limits the ability to meaningfully address bias. “When we ask for race information, some find it offensive,” Dr. Mamdani explains, adding that “when we don’t [ask for that information], others say it’s unethical. You can’t have it both ways.”

Clinical AI presents a difficult tradeoff between ethical idealism and lives saved. CHARTWatch, which does not include race data and has faced criticism for this limitation has nevertheless been associated with a 26% reduction in unexpected in-hospital mortality.1 He asks, “If a tool saves lives, is it ethical not to use it while we wait for perfect data?” At Unity Health, ensuring the responsible use of AI is a central priority. Projects undergo ethics review and bias assessment, and then enter a “silent testing” phase, during which models run without influencing patient care. CHARTWatch underwent nine months of silent testing before its official rollout. Rigorous evaluation and ongoing performance monitoring are essential to minimizing bias and ensuring responsible AI use in clinical practice. These frameworks reflect a serious commitment to ethical use of AI in clinical care and enable the safe, responsible integration

of AI tools into high-stakes clinical environments like the ED.

Dr. Mamdani emphasizes that training the next generation of AI researchers is critical for its continued success. For students eager to enter the field, Dr. Mamdani offers practical advice: identify what you enjoy and what you excel at and let that guide your path. “If you love math and you’re good at it, learn to code. If you’re more interested in people and processes, focus on change management or ethics. There’s a role for everyone in AI.” Dr. Mamdani’s vision is both ambitious and humanistic. His work reflects a future where AI strengthens, rather than replaces, the human connection at the heart of medicine. It’s a vision that holds promise for the ED, reshaping care by equipping clinicians with real-time insights when they matter most.

1. Verma AA, Stukel TA, Colacci M, et al. Clinical evaluation of a machine learning–based early warning system for patient deterioration. CMAJ. 2024 Sept 16;196(30):E1027–37.

2. Gregory CJ, Marcin JP. Golden hours wasted: The human cost of intensive care unit and emergency department inefficiency*. Crit Care Med. 2007 June;35(6):1614.

3. Michael Garron Hospital. MGH’s Stavro Emergency Department adopts AI transcribing tool to reduce patient wait times and address physician burnout [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Michael Garron Hospital; 2024 Nov 6 [cited 2025 Dec 16]. Available from: https://www.tehn.ca/about-us/newsroom/mghs-stavro-emergency-department-adopts-ai-transcribing-tool-reduce-patient-wait

4. de Wit K, Tran A, Clayton N, et al. A Longitudinal Survey on Canadian Emergency Physician Burnout. Ann Emerg Med. 2024 June;83(6):576–84.

5. Emergency Department Overcrowding in Canada: CADTH Health Technology Review Recommendation [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 16]. (CADTH Health Technology Review). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK599980/

6. Smith CW, Malhotra AK, Hammill C, et al. Vision Transformer-based Decision Support for Neurosurgical Intervention in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: Automated Surgical Intervention Support Tool. Radiol Artif Intell. 2024 Mar;6(2):e230088.

7. Kwon H, Kim YJ, Lee JH, et al. Incidence and outcomes of delayed intracranial hemorrhage: a population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2024 Aug 22;14(1):19502.

By Mya Chronopoulos and Michellie Choi

Sirens fade as the doors to the hospital swing open. Before the wheels of the stretcher even lock, a physician is already at work—glancing at monitors, issuing orders, and making split-second decisions that leave no room for hesitation. In these moments, one minute may be the difference between life and death. This is the image that comes to mind when one imagines emergency medicine. The moments preceding what happens in the trauma bay are critical—but often overlooked. These moments are the ones that Dr. Brodie Nolan aims to optimize to promote better outcomes in trauma care.

Dr. Nolan is an emergency and trauma team leader at St. Michael’s Hospital, as well as a transport physician with Ornge, Ontario’s air ambulance service. Initially uncertain of his career path, Dr. Nolan enrolled at Wilfred Laurier University for his undergraduate studies. During orientation, he witnessed a student collapse a few rows in front of him, and the coordinated response of first responders immediately drew his attention. Inspired, he began volunteering across campus, assisting first responders by supplying oxygen and medical equipment—an experience that provided early exposure to the intensity of emergency care. Dr. Nolan later attended medical school at the University of Toronto, where he gravitated towards emergency and trauma medicine. “In trauma, you’re dealing with some of the sickest patients in the country, but this allows more time to get to know one patient and their family,” Dr. Nolan says.

As a researcher, Dr. Nolan focuses on optimizing care in the first hour after traumatic injury–what trauma physicians call “the golden hour”. For trauma patients, such as those experiencing massive bleeding, timely care within this small window of time is critical for ensuring good outcomes. “In studies looking at patients with massive bleeding, for every one-minute delay in getting a blood transfusion, their odds of death go up by five percent,” Dr. Nolan says.

Speed and efficiency in trauma care depend largely on the location of the incident. As Dr. Nolan explains, “If you can’t change where people live, then you need to be able to bring the hospital to them—a challenge known as the “tyranny of distance.” While downtown Toronto is minutes away from two level I trauma facilities, many rural regions of Ontario are hours from specialized care. Through his work, Dr. Nolan hopes to eliminate this barrier to timely care.

Bridging this gap in access to timely trauma cases is the mission of Ornge, Ontario’s air ambulance service. Ornge provides rapid air and land medical transport for critically ill or injured patients across the province. Working with Ornge gave Dr. Nolan firsthand insight into how delays in trauma care occur. In one instance, Ornge was dispatched to transport an unconscious motorcyclist on the side of the highway who was struggling to breathe. After takeoff to retrieve the patient, on-site paramedics cancelled the helicopter, deeming it unnecessary. Hours later, Ornge was called again for the same patient as a transfer from a community hospital. The patient was now

unstable and severely injured. “By then, you’re well outside of that first hour,” he said. Unfortunately, the patient arrived at the trauma centre too late and died. This case highlights how miscommunication and decentralized decision-making can contribute to preventable delays in trauma care.

Such experiences encouraged him to investigate and optimize the logistics of transport medicine. Although delays in prehospital trauma care are widely acknowledged, there is limited systematic data documenting how often they occur and their consequences. Dr. Nolan and colleagues conducted an analysis of air ambulance transports to identify common sources of delay—including inclement weather, waiting for documentation, delay to intubate, among others.1 His ongoing work aims to document these patterns and help systems better identify patients that require expedited transportation to trauma centres.

Dr. Nolan is also working to improve trauma care on the ground, not just in the air. The Trauma Black Box is an educational quality improvement tool that allows for the capturing of every aspect of trauma resuscitation, including patient data and the procedural environment, allowing teams to review what flowed well, where delays happened, and how future performance can improve.2 Dr. Nolan describes this technology as “reviewing game footage after a big sports game. It’s not for blame, but rather for learning.”

Beyond improving logistics and team performance, Dr. Nolan’s research also centres around how and when blood is given to trauma

Institute of Medical Science, Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation

patients experiencing severe bleeding. Prior to World War I, bleeding patients were given intravenous saline. While this temporarily restored blood pressure, saline is insufficient given its lack of oxygen and clotting factors. During the war, battlefield surgeons realized that delivery of whole blood—containing red blood cells, plasma, and platelets—is more effective, as it has crucial features that saline lacks.3 By the 1960s and 1970s, however, trauma care shifted to component therapy, in which donated blood is separated into its individual parts—red blood cells, plasma, and platelets. With this method, a single donation could help multiple patients—for example, someone with chronic anemia (low red blood cell count) could use a transfusion of just red blood cells, without the other components. This approach improved safety, efficiency,

and resource management, reducing adverse reactions by moving away from the one-sizefits-all model of whole blood transfusion.3

Although component therapy has become the most popular method of blood transfusion, a 2015 study suggested that trauma patients did better when given blood products in a 1:1:1 ratio (plasma:platelets:red blood cells), effectively recreating whole blood.4 More recent advances, like leukoreduction filters that safely remove white blood cells—which are responsible for many transfusion adverse reactions, including fevers, inflammation and immune complications—have made whole blood transfusion safer. It still remains uncertain which approach, component therapy or the new methods of whole blood transfusion, offers the best outcomes in trauma care.

These uncertainties prompted the development of the Study of Whole Blood in Frontline Trauma Canada (SWiFT), a national prehospital transfusion trial, co-led by Dr. Nolan, that investigates the efficacy of whole blood transfusion for patients experiencing severe bleeding.5 The study is currently recruiting patients and is still ongoing to develop conclusive results, but Dr. Nolan notes that while component therapy may be advantageous in classical care settings, whole blood transfusion has many potential advantages in high-pressure settings. “In a helicopter, you have two paramedics, a critically injured patient, and a lot going on,” he says. “Being able to administer a single bag [of whole blood], as opposed to two or three bags [separated into components], simplifies a lot.”

In a trauma bay with 30 people and endless resources, these logistics aren’t as daunting, but in the air, where space, time, and hands are limited, simplicity matters.

Dr. Nolan is pursuing multiple avenues to make great strides in trauma care. He is sustained in large part by his gratitude and the opportunity to work three different jobs that he loves: emergency shifts, trauma team leadership, and transport medicine. Each demand something different but still reinforce the others. “Emergency medicine is such a team sport,” he says. “There’s not that hierarchy that sometimes exists within medicine, everyone’s kind of just moving and doing what they can for the best of patients.” Whether he is at the bedside, in the trauma bay, or guiding paramedics from hundreds of kilometres away, his philosophy is grounded in urgency: acting early, decisively, and doing everything possible to keep patients within the critical window of timely care is essential to ensuring better outcomes in trauma care.

1. Nolan B, Haas B, Tien H, et al. Causes of Delay During Interfacility Transports of Injured Patients Transported by Air Ambulance. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019;24(5):625-33. doi:10.1080/10903127.2 019.1683662

2. Nolan B, Hicks CM, Petrosoniak A, et al. Pushing boundaries of video review in trauma: using comprehensive data to improve the safety of trauma care. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open. 2020;5(1):e000510. doi: 10.1136/tsaco-2020-000510

3. Nolan B, Schellenberg M, Ball CG, et al. Evidence Based Reviews in Surgery: a critical appraisal of whole blood resuscitation in injured patients. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2025; 68(3):E271-3. doi: 10.1503/cjs.009924

4. Holcomb JB, Tilley BC, Baraniuk S, et al. Transfusion of Plasma, Platelets, and Red Blood Cells in a 1:1:1 vs a 1:1:2 Ratio and Mortality in Patients With Severe Trauma: The PROPPR Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2015;313(5):471-82. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12

5. Antonacci G, Williams A, Smith J, et al. Study of Whole blood in Frontline Trauma (SWiFT): implementation study protocol. BMJ open. 2023;14(2):e078953. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2023-078953

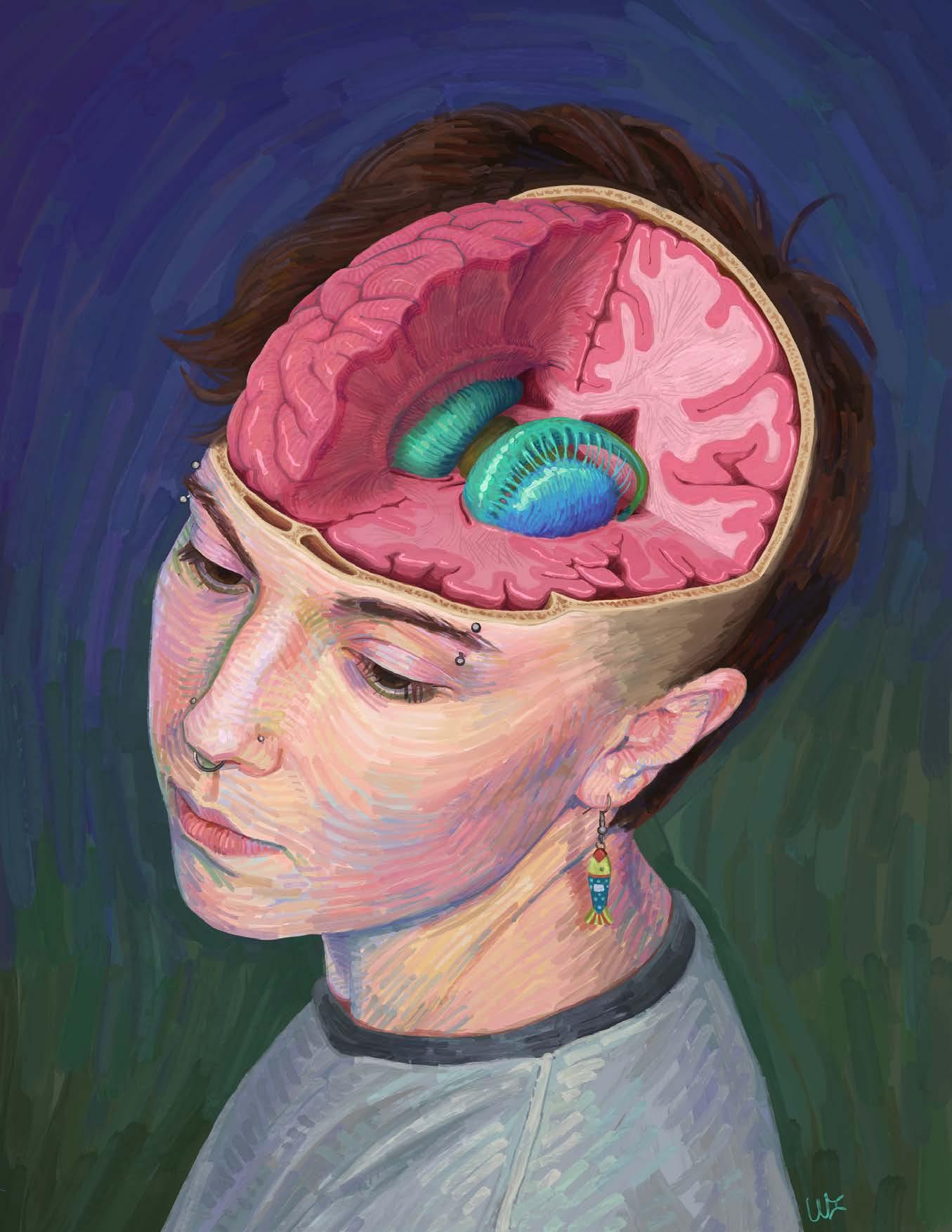

Winter is a medical illustrator with an interest in 2SLGBTQ+ health communication. He specializes in creating educational pieces for gender-affirming care. Style and aesthetics are just as important as accuracy in his work, as seen by his unique use of fine arts techniques in digital work.

Chloe Friesen is a first year MSc student in the biomedical communications program at the University of Toronto. She is passionate about the value of clear, high quality visuals for facilitating communication, especially in a healthcare setting.

Yvonne Ma is a first-year MSc student in the Biomedical Communications program, training to become a medical illustrator. With a strong background in art, she is passionate about integrating medical knowledge with visual storytelling. Yvonne aims to bridge art and science by making complex concepts accessible to diverse audiences through clear and engaging visuals.

Ravneet Jaura is a biomedical communicator in her 2nd year studies at the Master of Science in Biomedical Communications. Combining her unique experience as a scientist and researcher, she aims to communicate science with accuracy. Ravneet is particulary interested in storytelling through infographic visualization and animation. More of Ravneet’s work can be found at: www.ravneetjaura.com.

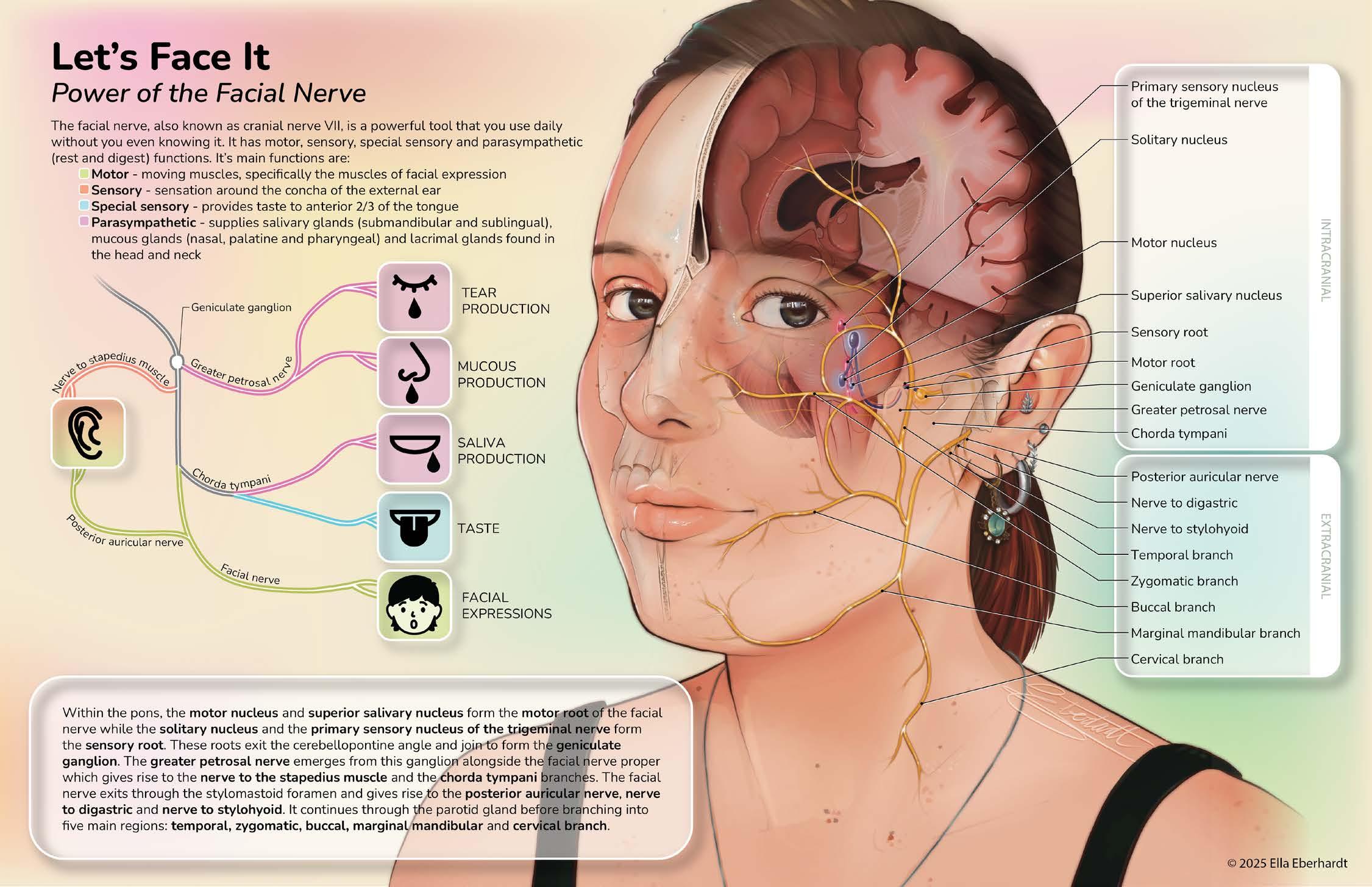

Ella is currently a second year MScBMC student at the University of Toronto. Her thesis is focused on creating patient education material for people experiencing facial palsy (paralysis) whether that be due to Bell’s palsy, congenital or otherwise. The goal is to create work that inspires people to understand more about their bodies.

Angela is a first year MScBMC student and a former high school biology/visual arts teacher. Her background in education and instructional design has shaped her commitment towards dismantling scientific illiteracy and student apathy.

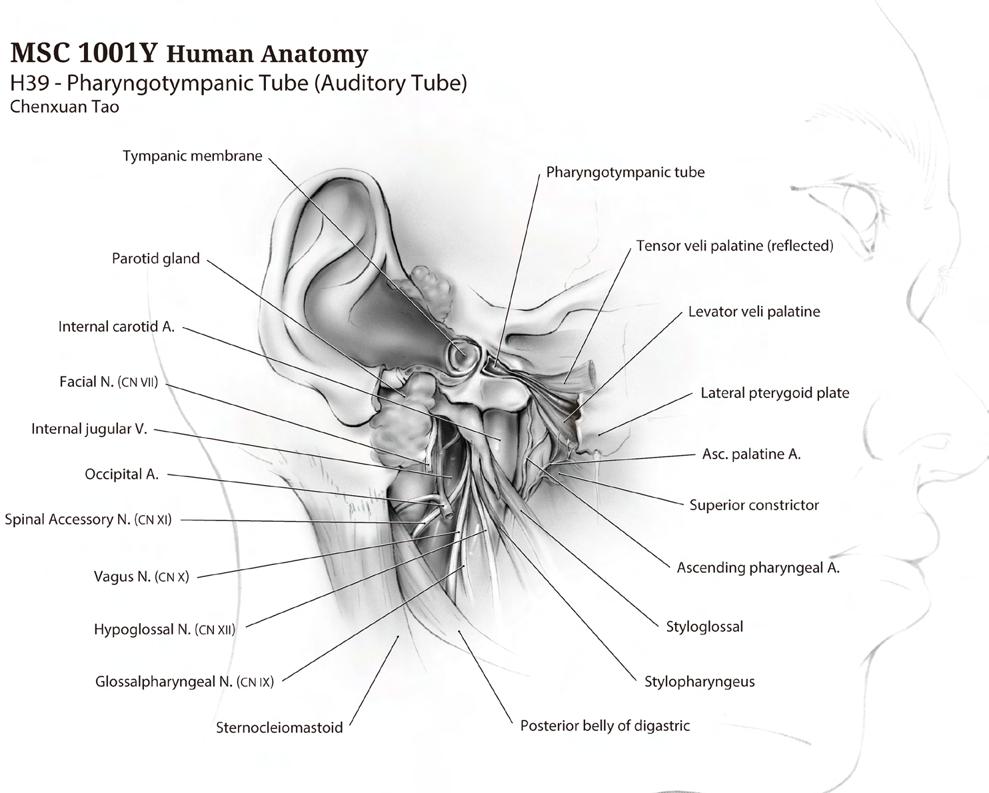

Chenxuan Tao is currently enrolled as a first year MScBMC student. His works aim to explore the balance of aesthetic attraction and scientific accuracy, making knowledge more accessible and interesting.

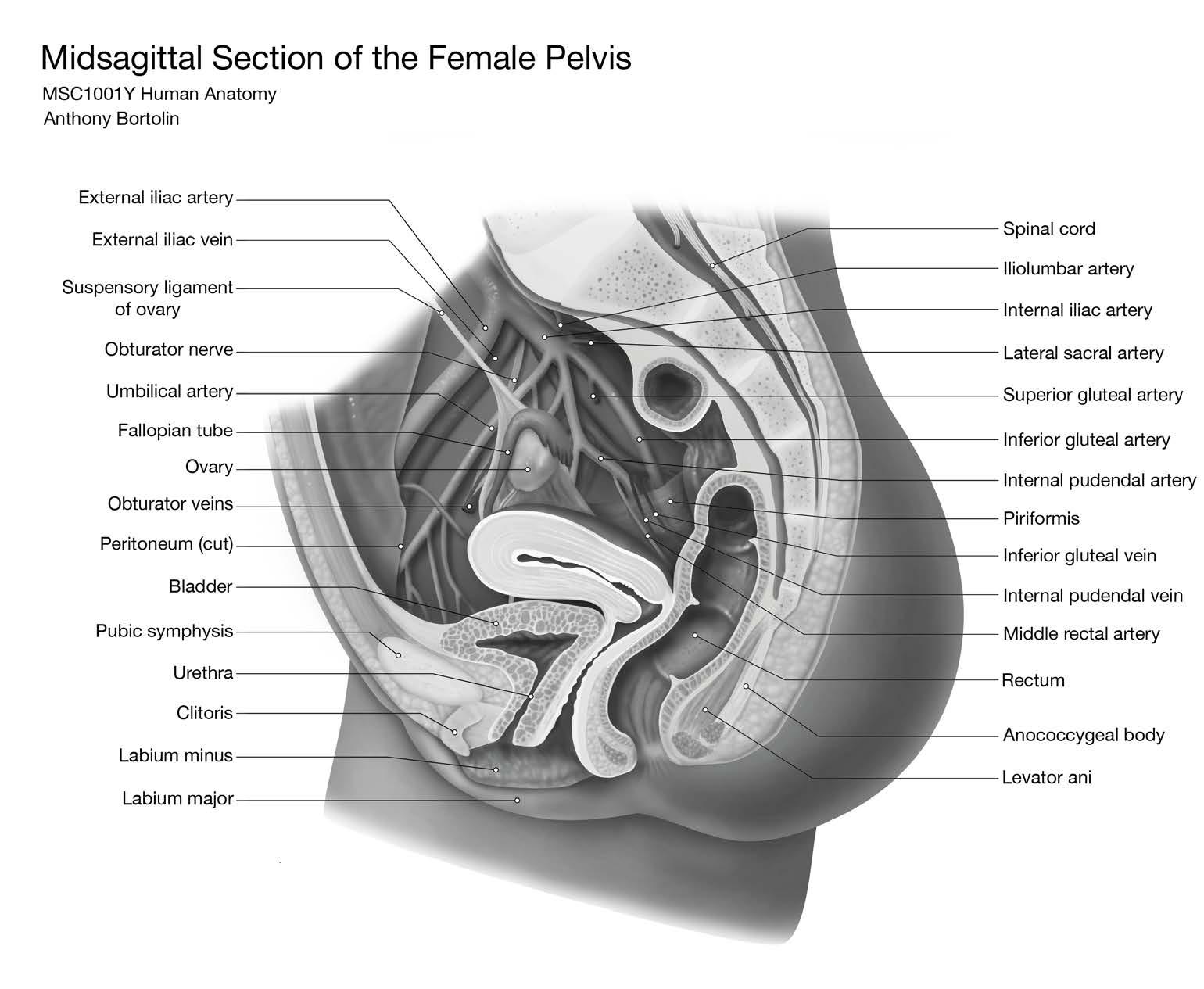

Anthony Bortolin is a first-year Biomedical Communications student at the University of Toronto with a passion for 3D scientific communication. He focuses on anatomydriven visuals that bridge accuracy and clarity.

By Saleena Zedan

“Can I please have more medication? I’m still in a lot of pain,” I asked my doctor in the emergency department (ED) after suffering excruciating pain from two slipped discs in my lower spine. I was denied an increased dose due to concerns about developing an opioid addiction from the ED—a prevalent issue across North America.1 Although I posed no risk for addiction, it did not matter; I had to persevere through the pain.

My experience is not unique—up to 94% of patients report feeling dismissed across all medical settings by their physicians.2 This feeling can be especially difficult in the ED, where patients often arrive in acute pain and distress. This demonstrates how easily pain can be minimized in emergency settings and highlights the need for change in the ED that places care at the forefront.

In Canada, pain management in the ED is suboptimal. Increasingly, patients are reporting longer wait times for pain relief, often exceeding two hours after initial contact.3,4 These prolonged delays may result in limited opportunities for physicians to conduct thorough assessments with their patients. This may contribute to decisions regarding prescription of pain medication being made quickly, without fully understanding patients’ pain or risk of addiction. As a result, pain management may become shaped by quick judgements based on

previous experiences with other patients rather than individualized care.

These are not the only concerns, as research shows inequity in pain management. Older adults often wait longer in the ED for pain-relieving medication compared to younger adults.4 While 70% of ED physicians report that patient age influences their prescribing practices, the extent to which this affects actual prescribing remains unclear.5 Race and ethnicity have also been found to negatively impact pain-management and wait times in the ED.6 Specifically, patients belonging to minority groups in the ED are less likely to receive adequate pain management and more likely to endure longer wait times before assessment or treatment. A scoping review found that in 11 (91%) out of 12 studies on ED wait times, minority groups waited longer than White patients to be seen.6 Meanwhile, in terms of pain treatment, six (35%) of 17 studies found that minority groups were less likely to receive any analgesics and 11 (85%) of 13 studies found that they were less likely to receive opioids.6 Another study using data from 2013–2017 found that Black and Hispanic patients had significantly longer wait times than White patients, waiting 47-50 minutes for pain medication compared to 36-40 minutes.7 This difference was seen even after controlling for triage level and hospital factors, once more raising concerns about delayed access to timely pain relief in the ED. Together, these findings demonstrate

that inequitable pain management in the ED may be shaped by unconscious assumptions that influence patient’s care.

Inequities in the pain management process are exacerbated by the history of opioid overprescription in the ED. Opioid overprescription in the ED began as a result of Purdue Pharma marketing the opioid oxycontin as safe and effective with little chance of developing an addiction in the 1990s.8 Consequently, between 2001-2010, prescribing opioids in the ED increased by approximately 10%.9 This history continues to influence practice today, creating a complex landscape in which physicians must balance the risk of undertreating pain with concerns about opioid-related harm. Although best practices recommend trying non-opioid options first,10 these alternatives are often limited and may be insufficient for severe pain. While new non-opioid medications such as Suzetrigine offer promise, they are not yet widely available and therefore do not meaningfully expand current ED treatment options.11,12 This lack of accessible, non-opioid treatments makes it challenging for physicians to balance two competing priorities of relieving patients’ pain while minimizing the potential for long-term opioid use.

Recent evidence illustrates this tension: a recent study found that most ED opioid prescriptions do not lead to persistent use, although small increases in use were observed in some patients, which helps explain why healthcare providers

remain careful when contemplating a prescription.13 However, at the same time, several patients in the ED still received opioid prescriptions even when they reported low pain ratings.14 Prescribing also varies widely across hospitals. A study that compared opioid prescriptions across three Canadian hospitals found that patients presenting to one ED were roughly 3.5 times more likely to be prescribed an opioid than patients at the other two, suggesting that the practices that are in place are not routinely followed across hospitals.10 These inconsistencies, paired with documented inequities in treatment, reveal how both caution and bias can shape management decisions in the ED.

It is unclear whether there is a relationship between opioid overprescription in the ED and the current opioid epidemic in Canada. To better understand whether ED opioid prescriptions play a role in Canada’s opioid crisis, future research could investigate long-term patient outcomes or examine how hospital-level prescribing practices may affect community-level harm. Regardless if there is a link between opioid prescription and the epidemic, overprescription of opioids remains an issue if individuals are being prescribed opioids unnecessarily and their core concerns are being overlooked.

In my case, as a young woman requesting additional medication, I may have been perceived as someone at a higher risk for opioid misuse, which resulted in the denial

of the treatment I needed. My experience reflects the broader patterns described, that pain management in the ED can be influenced by assumptions. These biases contribute to the documented inequities of longer wait times, undertreatment, and limited access to non-opioid medications in the ED. Addressing these issues requires greater awareness of how these assumptions shape clinical decisions and a commitment to providing equitable pain care across patients entering the ED.

1. Canada PHA of. Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada: Key findings [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025]. Available from: https:// health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-relatedharms/opioids-stimulants/

2. Kennedy LP, Quimby D. What you told us about medical gaslighting [Internet]. HealthCentral; 2023 [cited 2025 Dec 6]. Available from: https://www.healthcentral.com/chronic-health/what-you-told-usabout-medical-gaslighting

3. Woolner V, Ahluwalia R, Lum H, et al. Improving timely analgesia administration for musculoskeletal pain in the emergency department. BMJ open quality. 2020;9(1):e000797.

4. Mills AM, Edwards JM, Shofer FS, et al. Analgesia for older adults with abdominal or back pain in emergency department. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2011;12(1):43–50.

5. Varney SM, Bebarta VS, Mannina LM, et al. Emergency medicine providers’ opioid prescribing practices stratified by gender, age, and years in practice. World Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2016;7(2):106. doi:10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2016.02.004

6. Owens A, Holroyd BR, McLane P. Patient race, ethnicity, and care in the emergency department: A scoping review. Canadian journal of emergency medicine. 2020;22(2):245–53.

7. Lu FQ, Hanchate AD, Paasche-Orlow MK. Racial/ethnic disparities in emergency department wait times in the United States, 2013–2017. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021 Sept;47:138–44. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.051

8. Van Zee A. The promotion and marketing of oxycontin: commercial triumph, public health tragedy. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(2):221-227.

9. Mazer‐Amirshahi M, Mullins PM, Rasooly I, et al. Rising Opioid Prescribing in Adult U.S. Emergency Department Visits: 2001–2010. Academic emergency medicine. 2014;21(3):236–43.

10. Gomes T., Hamzat B, Holton A, et al. Trends in Opioid Prescribing in Canada, 2018 to 2022 [Analysis in brief on the Internet]. Canada’s Drug Agency; 2025 [cited 2025]. 15 p. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.cda-amc. ca/sites/default/files/hta-he/HC0071_Summary%20Report_EN.pdf

11. Mohiuddin AL, Ahmed Z. Suzetrigine – a novel fda‐approved analgesic – opportunities, challenges and future perspectives: A perspective review. Health Science Reports. 2025 Nov;8(11). doi:10.1002/hsr2.71545

12. Commissioner O of the. FDA approves novel non-opioid treatment for moderate to severe acute pain [Internet]. FDA; 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 29]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/ press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-non-opioid-treatmentmoderate-severe-acute-pain

13. Hayward J, Rosychuk RJ, McRae AD, Sinnarajah A, Dong K, Tanguay R, et al. Effect of emergency department opioid prescribing on Health Outcomes. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2025 Feb 9;197(5). doi:10.1503/cmaj.241542

14. McNeil CL, Habib A, Okut H, et al. Administration and Prescription of Opioids in Emergency Departments: A Retrospective Study. Kansas journal of medicine. 2021; 14:1–4.

By Kinjal Parekh

Imagine being a paramedic treating a trauma patient who’s bleeding uncontrollably. Every second feels like a countdown, yet your options are limited. The patient needs platelets to survive, but those lifesaving cells are stored within hospital blood banks, far from the scene of the crisis. Severe hemorrhage is the leading cause of death among trauma patients before they reach the hospital, and it accounts for up to 40% of in-hospital trauma fatalities.1 Given this reality, what if synthetic platelets were readily available to quickly reach the site of injury and stop bleeding?

Though this may sound like science fiction, it could soon become a reality, thanks to synthetic platelets which are designed to mimic the wound-healing functions of natural platelet and hold immense potential to transform trauma medicine.2 If proven safe and effective, they could one day become a routine treatment for first responders and clinicians to control blood loss and save countless lives.2 For now, however, further testing and careful clinical translation remain essential.

Platelets play a critical role in the body’s defense against blood loss. When a blood vessel is injured, they sense the damage, travel to the site, and trigger the coagulation cascade, a chain reaction that forms a stable clot and stops bleeding. Without them, even minor injuries could become fatal.3

The current standard of treatment for severe bleeding is the transfusion of blood products, such as platelets.2 While lifesaving, these donated platelets have notable limitations. They have a short shelf life of five days and must be stored at room temperature while constantly being shaken to prevent clumping, making them difficult to transport and maintain.2 They can also trigger immune reactions in recipients and carry a risk of bacterial contamination, making them the blood component most frequently associated with transfusion-related sepsis.4

These clinical challenges are compounded by supply shortages. In 2022, the American Red Cross declared its first-ever national blood crisis, reporting the worst shortage in over a decade. Hospitals were forced to delay vital transfusions, and platelet donations were in particularly short supply,5 underscoring the urgent need for sustainable, alternative ways to manage bleeding emergencies.

Efforts to improve bleeding management have led to several alternative approaches. Recombinant clotting factors, which are lab-produced versions of the body’s natural clotting proteins, can help restore coagulation in certain conditions, but their high cost limits widespread use, particularly in low-resource or emergency settings.6 Another option is topical sealants, often used in surgery, which can help control external bleeding by forming a physical barrier over wounds.7 However, they are ineffective against internal bleeding, which remains one of the leading

causes of preventable death in trauma.7 These limitations have driven scientists to explore a new frontier: artificial plateletmimetic materials that can work with the body’s own repair mechanisms. Such technologies could one day bridge the gap between current treatments and the urgent need for safe, shelf-stable, and rapidly deployable solutions.

A promising advance comes from the lab of Dr. Ashley Brown, an associate professor in the Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering at North Carolina State University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her team has developed platelet-like particles (PLPs), synthetic materials designed to replicate the key behaviours of natural platelets.2

These PLPs are made from ultrasoft hydrogels, which are soft, water-based polymers that can deform and respond dynamically to their environment. What makes them remarkable is their ability to recognize and bind to fibrin, a protein that naturally forms at injury sites to stabilize blood clots. This fibrin-targeting mechanism acts as a biological “homing signal,” guiding the synthetic platelets directly to the wound.7 Once attached, the PLPs change shape and contribute to clot retraction, a critical process that pulls the wound edges together and strengthens the clot, just as real platelets do. This helps seal the injury and may also accelerate tissue repair and recovery.7

In preclinical studies, these synthetic platelets have shown highly encouraging results. In mouse models of liver injury, PLPs rapidly localized to the site of bleeding and significantly reduced blood loss compared to natural platelet transfusions. Treated animals displayed smaller wounds, more stable clots, and faster recovery. Similar outcomes were observed in rat and pig models, where PLP treatment led to reduced bleeding and effective clot formation.7

Importantly, the particles did not accumulate in major organs like the liver, a common concern for nanoparticlebased therapies. Instead, they were safely filtered and cleared by the kidneys within hours. Even in healthy animals without injury, PLPs circulated harmlessly without triggering unwanted clotting elsewhere. This selective, injury-dependent activity is a major step forward in ensuring both safety and precision.7

In addition to their safety profile and efficient wound healing, synthetic platelets offer another key benefit: their availability. These platelets can be produced in laboratories, making them readily available to patients regardless of blood type, which is a major advantage in emergencies where time is critical. Because their production does not rely on blood donations, they could help overcome ongoing platelet shortages and ensure a consistent, highquality supply.8

Dr. Ronald Warren, a program director in the Division of Blood Diseases and

Resources at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, explains, “By developing a new generation of treatment options for emergency medicine, this research may help improve patient outcomes while potentially reducing healthcare costs.”2

Dr. Brown’s team is now exploring how best to store these particles. Early findings show they can be freeze-dried, making them ideal for ambulances, military settings, and remote areas, or kept in liquid form for hospital use. With continued refinement and testing, synthetic platelets could soon offer a safe, scalable, and lifesaving tool for controlling bleeding.2

While the results are exciting, innovation in medicine always requires careful testing. These synthetic platelets, though impressive, do not yet replicate all the complex functions of natural ones, including how real platelets work together to build and strengthen a clot. So far, they have only been tested in experimental settings, where they were given as a single treatment and not in combination with other therapies. In the future, researchers will need to evaluate how well they work alongside regular platelets or other bleeding treatments, and whether repeated doses are safe and effective.7 Most importantly, there have been no in-human clinical trials yet, which is critical for these synthetic platelets to become a reality.7

Nonetheless, even in these early stages, the potential of synthetic platelets is undeniable. Representing a new generation of trauma care, these engineered particles, with continued research, collaboration, and cautious optimism, could one day become a standard treatment in trauma settings, transforming how we save lives when every second counts.

1. Raykar NP, Makin J, Khajanchi M, et al. Assessing the global burden of hemorrhage: The global blood supply, deficits, and potential solutions. SAGE Open Medicine. 2021 Jan;9:205031212110549.

2. A potential game-changer for emergency medicine: synthetic platelets. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. 2024. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/news/2024/potential-game-changer-emergency-medicine-synthetic-platelets

3. Holinstat M. Normal Platelet Function. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2017 Jun;36(2):195–8. Available from: https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5709181/

4. Levy JH, Neal MD, Herman JH. Bacterial contamination of platelets for transfusion: strategies for prevention. Critical Care. 2018 Oct 27;22(1).

5. American Red Cross. Red Cross Declares First-ever Blood Crisis amid Omicron Surge. Redcross.org. 2022. Available from: https:// www.redcross.org/about-us/news-and-events/press-release/2022/ blood-donors-needed-now-as-omicron-intensifies.html

6. Blankenship C. To manage costs of hemophilia, patients need more than clotting factor. Biotechnology Healthcare. 2008 Nov 1;37–40.

7. Nellenbach K, Mihalko E, Nandi S, et al. Ultrasoft platelet-like particles stop bleeding in rodent and porcine models of trauma. Science translational medicine. 2024 Apr 10;16(742).

8. Synthetic platelets stanch bleeding, promote healing using advanced materials. National Science Foundation. 2024. Available from: https://www.nsf.gov/news/synthetic-platelets-stanch-bleeding-promote-healing.

By Ana Piric

No one expected emergency departments’ 24/7 availability to come to an end. Many rural towns across Canada are experiencing reduced emergency department hours, operating only during daylight and with planned evening and weekend closures.1 In Chesley, a small community in Bruce County, Ontario, the emergency room (ER) has been open only on weekdays from 7a.m. to 5p.m. since 2022.2,3 In addition, countless unplanned closures have left patients stranded with no option besides travelling to the closest town with an open emergency department.1 Even according to Natalie Mehra, the Executive Director of the Ontario Health Coalition, ER closures have become so severe that “it’s at the point that if a hospital ER is closed in one place, there’s no guarantee the one at the next-closest hospital is open.”2 Similarly, The Globe and Mail reports that 34% of Canadian ERs have experienced a closure since 2019, collectively totalling 1.14 million hours or 47,500 days.1

While the pandemic deepened discrepancies in rural emergency care, unequal access to care is nothing new. In 2015, just 11.8% of Canadian nurses served rural or remote communities, despite these areas representing approximately 17.8% of the population. 4 Even recent data from 2024 demonstrated only 7% of physicians in Canada practiced in rural areas.5 Recruitment and retention of healthcare workers has long been imbalanced in rural compared to urban

communities across Canada due to challenges with attracting healthcare workers. 6,7 Contributing factors include limited hospital financial resources and infrastructure, the geographic isolation of communities resulting in reduced access to transit and schools, and increased burnout in overworked hospitals. 7,8 These recruitment challenges contribute to a snowball effect of reduced access to primary and emergency care, ER closures, and ultimately, poorer health outcomes for patients in rural areas.6 Furthermore, generations of residents are faced with the difficult choice of leaving their smaller hometowns due to limited healthcare access. 1,2 With over 350 physician vacancies in Northern Ontario alone, 7 it’s clear that this already concerning issue will worsen if effective solutions are not implemented.

The cycle of instability in emergency care systems causes further problems, as unpredictable closures deter new healthcare workers from accepting positions at rural ERs.2 One solution is hiring locum physicians and nurses who temporarily step in and fill desperatelyneeded positions that would otherwise be offered as permanent roles.6,7 While this approach bridges the staffing gap, several other issues have emerged. Locum physicians and nurses are compensated by the provincial government, but hospitals often provide incentives by topping up their salary and paying for expenses such as accommodations, flights, and car

rentals.7 These financial benefits hinder long-term solutions by de-incentivizing healthcare workers from accepting permanent positions.6 Top-up practices also lead to competition for emergency care between hospitals in neighbouring towns, further contributing to poor health care outcomes.7

The Ontario and municipal governments have additionally proposed that some ERs be reclassified as urgent care centers to redistribute resources and healthcare staff based on the level of care patients require. 1 In contrast to ERs, urgent care centers (UCCs) provide same-day care for pressing, yet non-life-threatening concerns; UCCs often operate later than walk-in clinics, but close nightly. It is possible that reclassifying ERs into UCCs could lead to shorter wait times and less crowding, ensuring more timely care and improved patient outcomes.1 Conversely, the issue with reclassifying ERs into UCCs lies in the fact that round-the-clock access is no longer the status quo. Without improvements in accessing emergency care in ERs, reclassification is not a long-term solution, and inequities in accessing emergency care will be deepened. 6,9

Systemic solutions aimed at achieving long-term impacts are being implemented. As of September 2024, there has been increased funding from the Ontario government to enhance physician compensation in ERs and standardise pay for physicians in rural

areas.10 In August 2025, the Ontario government aimed to address nursing shortages by expanding the number of nursing training and education seats at Ontario colleges and universities.11 To alleviate physician shortages, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine has established a social accountability mandate to promote medical school enrollment from students in rural, Francophone, and Aboriginal communities in Northern Ontario and to encourage graduating physicians to practice in their home communities.12 This program has successfully retained 50% of physicians in independent practice within Northern communities; however, more physicians continue to settle in larger centres across Northern Ontario rather than rural communities.12 As a parallel effort, initiatives like the Ontario government’s Learn and Stay grant and the Canadian government’s Canada Student Loan Forgiveness program aim to encourage healthcare program graduates to provide care in underserved rural or remote communities.13,14 Ontario’s Learn and Stay grant covers educational costs for students enrolled in priority programs such as nursing, paramedic, and laboratory technologist programs in underserved communities as long as they work a term in the same community after graduation.13 Similarly, through the Canada Student Loan Forgiveness program, family medicine physicians and residents are eligible for $60,000 in loan forgiveness while nurses are eligible for $30,000 in loan forgiveness

for five years of work in underserved or rural communities.14 It is only through continued targeted actions such as these, which address the underlying issues in attracting and retaining healthcare workers, that ERs can return to providing reliable 24/7 care.

Rural ERs are in crisis. Patients requiring immediate care are considered lucky if their local ERs are open and often have to travel to neighbouring ERs, which may or may not be open.2 Consequently, healthcare staff are discouraged from working in rural ERs, perpetuating a cycle of instability.2 Addressing discrepancies in emergency care in rural communities requires urgent, intentional decisionmaking that reflects the underlying issues in rural health care to ensure long-term impacts. While progress has been made in the right direction, continued efforts are needed to eliminate emergency care inequities in rural areas across Canada.

1. Raman-Wilims M, Thanh Ha T, Grant K. Canada’s emergency room crisis is worse than we thought. The Decibel: A Daily News podcast from the Globe and Mail [Internet podcast]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/podcasts/ the-decibel/

2. Kerr P. Ontario Health Coalition warns that Chesley Hospital most at risk of closure in the province. Ontario Health Coalition [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.ontariohealthcoalition.ca/index.php/ontario-health-coalition-warns-that-chesleyhospital-most-at-risk-of-closure-in-the-province-2/

3. Bhargava I. Rural Ontario residents offer solutions amid emergency room closures at local hospitals. CBC News [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ london/rural-ontario-residents-offer-solutions-amid-emergency-room-closures-at-local-hospitals-1.7383545

4. Macleod MLP, Stewart NJ, Kulig JC, et al. Nurses who work in rural and remote communities in Canada: a national survey. Human

Resources for Health [Internet] 2017;15(1). Available from: https:// dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12960-017-0209-0

5. A profile of physicians in Canada. Canada Institute for Health Sciences [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 November 5]. Available from: https:// www.cihi.ca/en/a-profile-of-physicians-in-canada

6. Ireton J, Ouellet V. 2024 Worst Year for Ontario ER closures, CBC analysis finds. CBC News [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/data-analysis-er-closures-three-years-2024-worst-year-for-scheduled-closures-1.7396789

7. Hassan S. Rural Ontario hospitals offering hefty incentives for traveling doctors amid shortage. Global News [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://globalnews.ca/news/11312973/ rural-ontario-hospitals-offering-hefty-incentives-for-traveling-doctors-amid-shortage/

8. Challenges and Opportunities in Recruiting Rural Healthcare Workers. Supplemental Health Centre [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Nov 10]. Available from: https://shccares.com/blog/workforce-solutions/ rural-healthcare-recruiting-challenges/

9. Ireton J. Should some rural ERs close permanently if better supports are in place? CBC News [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/rural-er-issuesshould-some-close-permanently-1.7402517

10. Ontario Government and Ontario Medical Association Confirm Funding Increase That Will Protect Provincial Health Care. Ontario Newsroom [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1005805/ontario-government-and-ontario-medical-association-confirm-funding-increase-that-will-protect-provincial-health-care

11. Ontario Government and Ontario Medical Association Confirm Funding Increase That Will Protect Provincial Health Care. Ontario Newsroom [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1006278/ontario-investing-568-million-to-expand-nursing-enrollment

12. Ross B, Newbery S, Cameron E, et al. Rurally focussed undergraduate medical education at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine University. Canadian Journal of Rural Medicine. [Internet] 2025;30(2):101-102. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/cjrm/ fulltext/2025/04000/rurally_focussed_undergraduate_medical_education.10.aspx

13. Ontario Expanding Learn and Stay Grant to Train More Health Care Workers. Ontario Newsroom [Internet]. 2023. [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1002652/ontarioexpanding-learn-and-stay-grant-to-train-more-health-care-workers

14. Drawing more doctors and nurses to rural and remote communities through Canada Student Loan forgiveness. Government of Canada [Internet]. 2025. [cited 2025 Oct 25]. Available from: https://www. canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/news/2025/03/drawing-more-doctors-and-nurses-to-rural-and-remote-communitiesthrough-canada-student-loan-forgiveness.html

By Rachel Lebovic

“Hi there. My name is Rachel, and I’m with the peer support team. We check in on anyone who comes into the department between the ages of 16 and 29 because we know the emergency department can be an overwhelming and uncomfortable environment, especially for young adults, so our job is to check in, see how you are doing, and see if there is anything we can do to make your time here a little easier”. As a peer support worker, this is how I introduce myself to patients at the Mount Sinai Hospital (MSH) emergency department (ED).

Soon after starting my PhD at the Institute of Medical Science (IMS) studying suicide prevention, I was looking for a hands-on opportunity to complement my research, allowing me to better understand the systems and serve the populations I hope to work with in my future. Given that my research and career aspirations are largely driven by my lived experience navigating mental health care, peer support felt like the perfect option.

The RBC Pathway to Peers (P2P) program1,2 launched at MSH in May 2020. In his work as an emergency medicine physician, Dr. Bjug Borgundvaag, Director of the Schwartz/Reisman Emergency Medicine Institute (SREMI), noticed an increasing number of young patients were presenting to the MSH ED with mental health and substance use concerns. Dr. Borgundvaag was likely not the only ED physician across the province who noticed this, as from 2006 to 2017,

there was an almost 90% increase in ED visits for mental health reasons in youth.3 Recognizing the limitations of what the ED could offer these patients, yet wanting to better meet their needs, the RBC P2P program was created. Dr. Borgundvaag and Dr. Shelley McLeod, both researchers at SREMI and faculty members in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto, have led the development, implementation,4 evaluation, and now expansion of the RBC P2P program to Michael Garron Hospital.

Peer Support Canada defines peer support as a “form of service provision, a philosophy, and a movement.”5 In simple terms, peer support refers to an individual with a lived experience providing support to another in a similar situation. Founded from the consumer/survivor and drug user activist movements, where those who were mistreated by the healthcare and criminal justice systems advocated for better mental health and substance use care, peer support is based on the core values of:

• Hope and recovery

• Self-determination

• Empathetic and equal relationships

• Dignity, respect, and social inclusion

• Integrity, authenticity, and trust

• Health and wellness

• Lifelong learning and personal growth

Through these values, peer support emphasizes person-centred, traumainformed, culturally sensitive, and harm reduction approaches informed by antiracism and anti-oppressive principles. In our interactions, we aim to reduce power imbalances and empower patients in a confusing, limited system, where trust is often lacking.

While peer support is not a new concept, it is believed that the RBC P2P program is the first of its kind in Canada in which peer support workers are fully embedded into the ED setting. As non-clinical members of clinical teams, peer support workers are uniquely positioned to enhance patient care. Due to the flexible nature of our role, we can spend extended periods of time with patients, providing them with much-needed emotional support. This can be as simple as getting them a sandwich and a blanket or engaging in a more in-depth conversation.

For patients presenting with a mental health or substance use health concern, support often centres around empathizing with a shared experience. For example, I had a patient who was a university student in the ED for stomach pains. From her chart, I could see she had a mental health history, but my experience guided me not to assume those were related. I introduced myself and asked if I could