IMMpress Magazine

Magazine of the Department of Immunology, University of Toronto

Innovation in every reagent

For over two decades, our scientists have focused on creating unique products for the scientific community—empowering you with antibodies and reagents to find answers for your immunology research. We are constantly innovating to ensure you have the tools needed to make legendary discoveries.

Discover how our 35,000 reagents can make a difference in your lab:

• Fluorophore-antibody conjugates: dyes for conventional and spectral cytometry, including Spark PLUS and StarBright™ UV dyes.

• TotalSeq™: reagents that add protein detection to single-cell RNA or DNA sequencing in single-cell multiomic assays.

• LEGENDplex™: bead-based immunoassays for detection of up to 14 cytokines simultaneously.

• MojoSort™: column and handheld magnet-based magnetic separation systems for cell isolation and enrichment.

• Ultra-LEAF™ and GoInVivo™ antibodies: ideal for functional assays like blocking or stimulation assays.

• Cell-Vive™ GMP reagents: proteins, antibodies, and media for cell culturing.

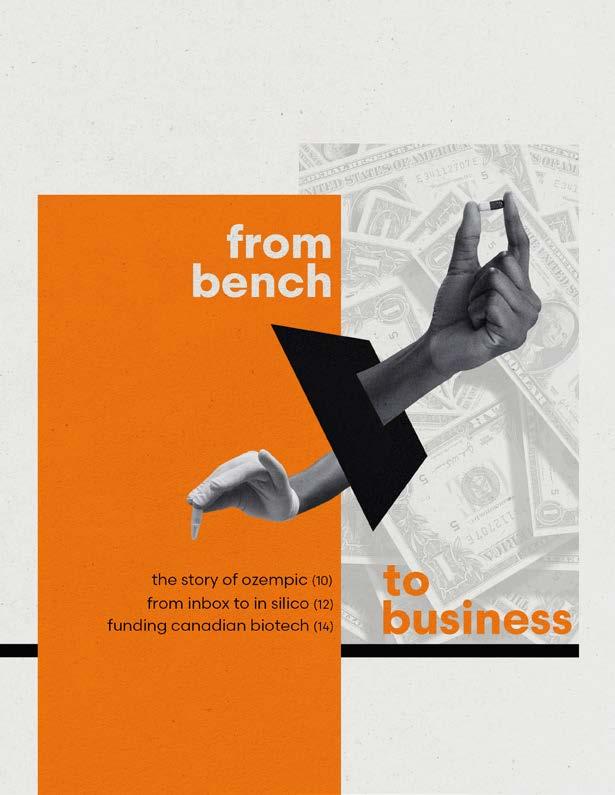

THIS ISSUE’S COVER

“Bench” to “Business”. “Academia” versus “Industry”. These terms are often written sideby-side as an act of juxtaposition, with an intention to highlight differences over similarities. Yet “Bench” and “Business” are co-dependent entities, with one thriving due to the success of the other. Without the rigorous experiments conducted at the bench, ideation and subsequent commercialization of life-saving therapies would be impossible. Without the commercial and therapeutic success of scientific innovation, public interest and funding which are required for continued research would diminish. For this issue’s cover, I chose to visually represent both the dichotomy and mutuality of “Bench” and “Business”. The cover is clearly divided into two parts. There are two hands facing opposite directions – one is gloved and holding a tube while the other presents a pill in front of a cash-pile backdrop. Nevertheless, the two hands are inevitably a pair, as if they share a joining body and are simply protruding out of two sides of a small, black portal. Ultimately, I hope this abstract illustration provokes the readers’ deeper curiosity for how two seemingly contrasting fields, “Bench” and “Business”, not only coexist but synergize with one another.

Jennifer Ahn Design Director

EDITORS-IN-CHIEF

Meggie Kuypers

Manjula Kamath

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Jennifer Ahn

SOCIAL MEDIA COORDINATOR

Tianning Yu

SENIOR EDITORS

Jennifer Ahn

Zi Yan Chen

Baweleta Isho

Manjula Kamath

Meggie Kuypers

Vera Lynn

Siu Ling Tai

Christopher Ryan Tan

Boyan Tsankov

Nicolas Wilson

Tianning Yu

DESIGN ASSISTANTS

Larissa Abdallah

Zoeen Carter

Yashar Aghazadeh Habashi

Baweleta Isho

Meggie Kuypers

Angelica Lau

Rachel Lin

Alina Mehra

Ria Menon

Annie Mitchell

Mariam Parashos

Preya Patel

Victoria Sephton

Sophie Sun

Tianning Yu

WRITERS

Yasmin Anning

Zi Yan Chen

Milea DiPonzio

Yashar Aghazadeh Habashi

Baweleta Isho

Manjula Kamath

Meggie Kuypers

Vera Lynn

Alina Mehra

Ana Sofia Mendoza Viruega

Annie Mitchell

Mariam Parashos

Anthony Piro

Siu Ling Tai

Boyan Tsankov

Tianning Yu

FOUNDING EDITORS

Yuriy Baglaenko

Charles Tran

C ontributors

Copyright © 2013 IMMpress Magazine. All rights reserved. Reproduction without permission is prohibited. IMMpress Magazine is a student-run initiative. Any opinions expressed by the author(s) do not necessarily reflect the opinions, views or policies of the Department of Immunology or the University of Toronto.

Join our mentorship Join our mentorship team team

WE’RE RECRUITING MOTIVATED MENTORS AND MENTEES

THE GRADUATE PEER SUPPORT NE T WORK IS A FACULT Y OF MEDICINE INITI ATIVE TH AT AIMS TO IMPROVE WELLBEING OF GRADUATE STUDENTS.

OUR MENTORSHIP PROGRAM PAIRS TRAINED STUDENTS WITH MENTEES TO PROVIDE SUPPORT WITH CH ALLENGES TH AT STEM BEYOND THE SPHERE OF ACADEMIC AND CAREER GOALS.

SIGN UP USING THE QR CODES BELOW:

MENTOR: MENTEE:

The high cost of being one-in-a-million: Pharmaceutical industry makes billions from therapies to treat rare diseases

CAR-T Therapy: When medical breakthroughs bear steep price tags

Spinning Out: highlighting companies that bridge the translation gap from academic discovery to biotechnology innovation

From Coast to Coast: Canada’s Growing Immunology and Biotechnology Landscape

Biotech success story: where collaboration meets competition

MITACS: From Academia to Innovation

Thinking

Juan Mauricio Umaña: the path from a Master’s degree to Principal Research Associate at BlueRock Therapeutics

The Story of Ozempic

From Inbox to In Silico: The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Drug Development

Funding Canadian Biotech: How Venture Capital, Private Equity, and Public Programs Shape Our Innovation Ecosystem

Congratulations you’ve graduated… now what??

Building your curriculum vitae: what can you do now to improve your future job prospects?

Surviving as a PhD student in a shaky economy

FROM THE

CHAIR L etter

This newest IMMpress Magazine issue, “From Bench to Business”, focuses on scientific entrepreneurship, recent discoveries, and job opportunities within our field. This was a very comprehensive issue that should be required reading for anybody engaged in research. I think I’ll drop off a copy at the Rotman School of Management so they can have an inside view of what it is to do discovery research in Immunology that ultimately leads to therapies.

I was inspired by the scan across our department at burgeoning spin-offs, and the scan across Canada at burgeoning companies. But what inspired me the most was the story of Novo Nordisk. Of course, we know of this company as the maker of Ozempic, but its history is very relevant to a country like Canada. Novo Nordisk was born out of what used to be a fierce competition between two Danish companies that buried the hatchet and came together to become more than the sum of their parts. Not only did this actualize on some important therapeutics, but the philanthropic work of Novo Nordisk to fund the discovery sector has been an

important part of Denmark’s economy.

Despite our land mass, Canada is a small country like Denmark. We cannot afford to duplicate efforts, yet too often we are parochial and provincial. In light of our recent economic separation from the United States, we must grow out of our adolescence and become better at working together, putting on our “Canada Hats” as I like to say. A balanced diet of lab-directed and mission-directed science driven by shared goals and values is the culture we must strive to achieve. A bit of competition and a bit of collaboration in good measure have the potential to bake a better Canadian biotech cake.

Also in this issue are some positive vibes for learners wondering what is next in their careers. The Department of Immunology prides itself in training scientists that can use their powers of problem solving, persistence and critical thinking to achieve great things, whether at the bench or elsewhere. We have a tremendous track record of launching successful scientists into multiple sectors. And there’s no “mistakes” in one’s next step – I myself toggled be-

tween academic, industry and back to academia again. I learned a great deal in these different environments.

I sit and write this in late December 2025, at the end of a tumultuous year. I don’t know if you feel it, but I sense optimism in the air and a collective desire to do hard things that will make Canada a more prosperous and humane place to live. I hope you all begin 2026 with a sense of optimism – together we can do a great deal.

Jen Gommerman, PhD

Canada Research Chair in Tissue

Specific Immunity

Professor and Chair, Department of Immunology

“Will I be able to get a job in the future?”

This is a question that every grad student asks themselves as they move closer to the date of graduation. In the current global economy, employment prospects are looking more dire than ever before. And yet, as immunologists, we are fortunate to be a part of a fascinating, dynamic area of study in which discoveries at the bench are increasingly shaping real-world solutions, driving innovation across fields such as biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and medical diagnostics. In this issue of IMMpress Magazine, we seek to highlight the pathways, challenges, and opportunities involved in turning fundamental science into life-changing technologies, ultimately preparing our fellow students for a life beyond academia.

As a background refresher, we begin with an overview on the life cycle of

L etter

FROM THE

EDITORS

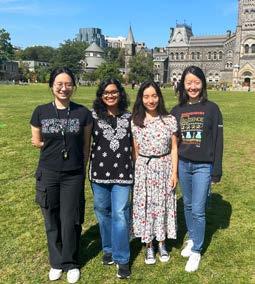

In order of left to right: Tianning Yu (Social Media Coordinator), Manjula Kamath (Co-Editor-in-Chief), Jennifer Ahn (Design Director) & Meggie Kuypers (Co-Editor-in-Chief)

a biotech startup (pg.8). Our featured articles cover the modern-day success of Ozempic (pg.10), technological advancements in drug development and regulation (pg.12), and the different funding sources available to get a startup off the ground (pg.14).

It’s not easy bringing a drug to market, and we delve into some of the challenges of commercialization in areas such as rare disease treatment (pg.16) and CAR-T cell therapy (pg.18). We’ve invited Juan Mauricio Umaña, an M.Sc. alumnus who is now a Principal Research Associate at BlueRock Therapeutics, to share his story of professional success (pg.20), and we further explore the success of biotech companies in the greater Toronto area (pg.22), across Canada (pg.24), and beyond (pg.26). It may be daunting to step into the private sector for the first time, so we highlight national initiatives (pg.28) and some general tips (pg.29) to help bridge students from academia to industry. And while there is value in our degrees (pg.30), there is also a lot we can do to build up our marketable skills (pg.32) to survive in this current economy (pg.34), as well as other

career avenues to investigate (pg.36). Lastly, we wrap up this issue with a book review on Doctored by Charles Piller (pg.38), a sobering reminder of the importance of our work and how bench-side discoveries can translate into altering the course of people’s lives.

While it’s impossible to guarantee a job right after graduation, at the very least we should try to graduate with no regrets. We hope this issue can help inspire our peers to move forward with confidence in each of their own professional journeys. As always, we thank the fantastic writers, editors, and designers who contributed to this issue. As a student-run publication, this magazine truly wouldn’t be possible without you.

Co-Editors-in-Chief

Meggie Kuypers

HaveThe Life Cycle of a Biotech Startup

you ever wondered how a discovery in the lab becomes a real-world therapeutic? We all know it takes a lot more than a genius idea to build a successful start-up. In the highly-regulated biotech and pharmaceuticals space, it is an expensive and time-consuming process. After all, biology can’t be rushed. Let’s look at the different stages in the life cycle of a biotech startup.

Stage 1 – Discovery

The discovery stage starts with a novel scientific observation that has the potential to translate into a therapeutic product to address unmet clinical needs. This phase typically occurs in academic laboratories and involves identifying novel drug targets, elucidating disease mechanisms, or discovering new biologicals with therapeutic potential. Success at this stage requires not only deep scientific rigor but also an understanding of the current clinical landscape and translational potential of the discov ery.Take the example of ‘Mounjaro’, a prescription drug called tirzepatide, primarily approved for managing blood sugar levels in adults with type 2 diabetes. More recently, it has also been approved as ‘Zepbound’ for its ability to promote weight-loss. These drugs are GLP-1 receptor agonists and function by increasing insulin secretion after eating, helping to move sugar into cells, slowing digestion, and promoting feelings of fullness. This leads to reduced calorie intake and weight loss.

This discovery started in the early 1980s with research on the proglucagon gene. Proglucagon is a precursor protein that the body cuts into smaller pieces to create several different hormones, including glucagon (which raises blood sugar) and GLP-1 (which lowers it).

Key Scientific Discoveries

GLP-1 Discovery at the University of Toronto (1982 - 1996)

1. Proglucagon Processing in the Gut (1983-1984)

Dr. Daniel Drucker during his postdoc in the Habener lab in 1984 demonstrated that Proglucagon is broken down into Glicentin, GLP-1 and GLP-2 in the gut. This was distinct from the pancreas, where it did not give rise to GLP-1 or GLP-2. This tissue-specific processing was revolutionary as it showed that the same gene could produce hormones with opposite effects depending on which enzymes cut it apart.

2. GLP-1 Stimulates Glucose-Dependent Insulin Secretion (1985-1987)

Further investigation showed that a shortened form of GLP-1 directly stimulated glucose-dependent insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells. Importantly, this only occurred under conditions of elevated glucose, providing an inherent safety mechanism against unwanted drop in blood sugar.

3. The Anorexigenic Discovery (1996)

The transformative moment came in 1996 when Stephen Bloom’s group at Hammersmith Hospital in London, along with Tang-Christensen and colleagues in Denmark, independently discovered through animal studies that GLP-1 administration reduces food intake.This discovery expanded the therapeutic potential of GLP-1 from just diabetes to obesity and metabolic syndrome, conditions affecting over 2 billion people globally.

Stage 2 – Pre-clinical Development

Pre-clinical development transforms a biological target or lead compound into a clinical candidate suitable for human testing. This stage involves iterative testing and refinement of the product. Three key areas of focus for developing typical drugs are: how the drug works in the body (pharmacology), whether it’s safe (toxicology), and whether it can be produced at scale (manufacturing). The goal is to generate sufficient data with pre-clinical models, including animal models, or cells, to prove safety and efficacy of the drug. The researchers can then file applications to investigate their identified biological as a new drug, which varies from country to country. For example, in the United States, researchers would file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which permits human clinical trials.

Most researchers can also apply for a patent in Stages 1 or 2 to safeguard their novel product from being commercialized by others. Interestingly, the GLP-1 story followed a different model. The foundational discoveries were published openly without restrictive patents on the basic biology. This allowed multiple companies (e.g., Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Amgen, AstraZeneca) to develop different GLP-1-based therapeutics.

Written by Manjula Kamath

Designed by Rachel Lin

Stage 3 – Clinical Trials

Clinical trials represent the most critical and expensive phase of drug development. The FDA requires a phased approach: Phase 1 (safety in healthy volunteers or patients), Phase 2 (proof-ofconcept in patients), and Phase 3 (pivotal efficacy and safety trials) before approval. Each phase has distinct objec tives and endpoints, and given high failure rates, for many potential therapeutics this is where their story ends.

Timeline of Tirzepatide Clinical Trials:

Phase 1: First-in-Human Studies (2016-2018)

Phase 1 trials for tirzepatide were conducted in healthy volunteers and patients with type 2 diabetes leading to dose selection for Phase 2/3 and establishing speed of action, persistence in the body, safety and tolerability.

Phase 2: Proof-of-Concept (2018)

316 patients with type 2 diabetes participated in the phase 2 trial for a 26-week period conducted by Frias et al. leading to proof of concept and approval for Phase 3.

Phase 3: SURPASS Program (2018-2022) - Type 2 Diabetes

Eli Lilly conducted five global Phase 3 trials (SURPASS-1 through -5) and two regional trials in Japan, collectively enrolling over 10,000 participants, which strengthened their case for regulatory approval. This trial demonstrated statistical superiority over the leading competitor, a critical finding for market positioning.

Phase 3: SURMOUNT Program (2019-2024) – Obesity

To gain approval for weight management in non-diabetic individuals, Eli Lilly conducted the SURMOUNT program. This trial demonstrated that tirzepatide maintains and extends weight loss achieved through lifestyle modification, compared to placebo, addressing a major challenge in obesity treatment.

Stage 4 – Regulatory Approval

Regulatory approval is the gatekeeping step between clinical development and commercialization. In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) reviews New Drug Applications (NDAs) for small molecules and Biologics License Applications (BLAs) for biological products. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) performs analogous functions in the European Union, and Health Canada for Canadian approval. The review process is rigorous, with regulatory body reviewers independently analyzing all clinical trial data, manufacturing processes, and proposed labeling. Approximately 90% of drugs entering clinical trials never receive FDA approval!

Eli Lilly engaged in extensive pre-submission interactions with the FDA through formal meetings since 2019. After the NDA was submitted in May 2021, it took a whole year until FDA approved it in May 2022. It was later approved by the EMA in July 2022, followed by Health Canada in November 2022, Australia in December 2022, and finally in Japan in April 2023. Eli Lilly made the strategic decision to brand tirzepatide differently for obesity (Zepbound) versus diabetes (Mounjaro). This helped them differentiate indications of the drugs for marketing and allowed separate pricing strategies.

Stage 5 – Commercialization

Commercialization represents the culmination of 1015 years of development efforts. This stage involves scaling up production to make millions of doses, building a sales team to reach doctors and patients, negotiating with insurance companies to get the drug covered, and managing the product strategically to maximize its impact and value over time. For most biotechnology startups, commercialization is handled by partners or acquirers, as building commercial infrastructure requires hundreds of millions in capital and medical commerce expertise.

Launch

Strategy for Mounjaro:

Prior to FDA approval, Eli Lilly invested heavily in manufacturing capacity, spending US$2.5B+ in capacity expansion from 2020-2023. Despite this preparation, demand exceeded supply. Demand coupled with Eli Lily’s strategic pricing in different countries, patient support programs, partnerships with Medicare/Medicaid programs, and consumer marketing has yielded astounding results. From a revenue of 274M in 2022, to an estimated revenue of 13B in 2024, Eli Lily’s two tirzepatide drugs are among the fastest growing drug launches in pharmaceutical history! Tirzepatide’s journey from a Toronto laborato ry to global medicine cabinets reflects Eli Lilly’s inspiring journey from a biotech startup to a pharm giant.

DThe Story of Ozempic

rug discovery is a game of long odds: only one in ten thousand lab discoveries survives the gauntlet from benchtop to prescription pad. Stranger still is the fate of a hormone discovered in a deep-sea creature and lizard venom, now reborn in the age of social media as a global weight loss icon – something it was never intended to be. This is the story of Ozempic, written in part by Dr. Daniel Drucker, a Toronto scientist whose work helped bring the drug to life. Before we delve in, we must pay tribute to University of Toronto scientists Frederick Banking and Charles Best, who began the first few pages of this story, with a note on diabetes.

“In science, you have a one in 10,000 chance of your research going from lab to drug.”

DIABETES, THE INCRETIN EFFECT, AND GLUCAGON

Diabetes comes in two forms, both characterized by elevated blood sugar (glucose) levels but differing in etiology. Both varieties revolve around the insulin hormone, a chemical messenger secreted into the bloodstream that regulates glucose uptake by cells. In type 1 diabetes, insulin-producing pancreatic -cells are destroyed by the body’s immune system. In type 2 diabetes (T2D), the pancreas still makes insulin, but the body resists the hormone’s command to absorb glucose, forcing the pancreas to produce more and more until it, too, begins to fail.

By the 1960s, physicians faced an epidemic of patients with T2D and few tools to help them. Researchers began searching for ways to coax the pancreas into properly absorbing glucose. Whilst doing so, they stumbled upon a curious fact: when patients ingested glucose, their bodies released more insulin and lowered blood sugar levels more effectively than when the same amount of glucose was infused directly into their veins. This suggested that the gut was communicating with the pancreas to stimulate insulin secretion in response to food. Today, this is known as the incretin effect. Scientists began testing hormones to see if they could reproduce this effect. One pancreatic hormone stood out. Glucagon, long

cast as insulin’s nemesis for its role in raising blood sugar, behaved strangely. Counterintuitively, injecting glucagon triggered a spike in insulin before blood glucose levels even rose. This paradox, that a hormone famed for undoing insulin’s work might also help summon it, transformed glucagon from villain to muse. Despite stimulating insulin release, the ultimate increase in blood glucose following glucagon administration meant it was not a suitable therapy. This, however, begged the question: is there something like glucagon that triggers insulin secretion without raising blood sugars? To answer this, researchers had to first embark on a deep dive to understand glucagon.

ANGLER FISH AND THE DISCOVERY OF GLUCAGON-LIKE PEPTIDE 1

In the early 1980s, isolating pancreatic hormones from mammals remained a challenge, posing a bottleneck for investigative studies. Scientist Joel Habener turned to the abyssal anglerfish as an alternative model organism, whose distinct pancreatic structure made it easier to isolate its hormones. Upon successfully isolating glucagon from the anglerfish, Habener’s team discovered that glucagon is derived from a larger precursor protein called preproglucagon, which can be cut into peptides. When scientists later examined the mammalian version of the preproglucagon gene, they found

a peptide called glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1).

At first, GLP-1 alone did not stimulate insulin release. However, a member of Habener’s team, Svetlana Mojsov, noticed that when pancreatic GLP-1 is shortened in its length, it looks more like glucagon and acts as a powerful trigger for insulin secretion in mammals. Building on this discovery, Daniel Drucker showed that the shortened version of pancreatic GLP-1 naturally exists at high levels in the small intestine. This observation by Drucker cemented the role of shortened GLP-1 as an incretin hormone. Importantly, GLP1 only worked when blood glucose levels were high, reducing the risk of hypoglycemia – a condition characterized dangerously low blood sugar levels which is a common complication of other diabetes medication. This made the peptide ideal for patients with type 2 diabetes. Intravenous infusions of GLP-1confirmed its effect in humans, but its half-life – the amount of time it takes for the body to eliminate half of the original dose – was only about two minutes, too short to be useful as a drug.

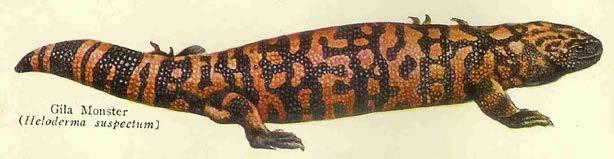

THE GILA MONSTER AND EXENDIN-4

A potential solution was to find an alternative that was stable enough to stay longer in the body. Endocrinologist John Eng turned to an unlikely source: the venom of the Gila monster, a desert-dwelling lizard whose bite was known to overstimulate the pancreas. From this reptile, Eng isolated a peptide called exendin-4, which bore striking resemblance to shortened form of GLP-1. When administered to dogs, exendin-4 boosted insulin secretion and normalized blood glucose levels. Importantly, exendin-4 stayed in the bloodstream for hours instead of minutes, making it a viable drug candidate.

PHARMA AND SERENDIPITY

Following his successful experiments, Eng filed a patent for exendin-4 and licensed it to Amylin Pharmaceuticals, which launched clinical trials in patients with type 2 diabetes. These trials showed that patients treated with exendin-4 had significantly lowered blood glucose levels compared to those on placebo controls. Building on this success, a research team led by Lotte Bjerre Knudsen at Novo Nordisk experimented with modifying the structure of GLP-1. This modification increased the peptide’s stability and longevity, making once-daily injections of this drug feasible. At the highest doses of this modified GLP-1, patients lost around 3% of their body weight, a serendipitous discovery prompting efforts to

further optimize the molecule. Through a series of tweaks, scientists eventually created semaglutide, a next-generation GLP-1 that strikingly led to 15-20% weight loss in patients during clinical trials. This breakthrough compound is now known by its globally recognized trade name: Ozempic.

THE WORLD OF OZEMPIC

Few drugs have leapt from medical journals to late-night television quite like Ozempic. What began as a treatment for T2D has become a global phenomenon: hailed, debated, and meme-ified in equal measure. Demand outpaced supply as people sought prescriptions for cosmetic weight loss, sparking shortages for diabetic patients and ethical debates about who these drugs are truly for. Physicians were left balancing excitement with caution, reminding the public that while GLP-1 variants are powerful tools, they are not magic. They work best when treating disease, not vanity.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Meanwhile, science continues to evolve. Variations of GLP-1 have shown promise far beyond treating diabetes and obesity, with studies suggesting therapeutic benefits for heart failure and chronic kidney disease. Many of these insights are rooted in the work from Dr. Daniel Drucker’s group at the University of Toronto, whose research continues to illuminate how these hormones act across multiple organ systems. Today, his lab is exploring how GLP-1–based therapies might modulate substance use disorders and neurodegenerative diseases, which could once again expand the boundaries of what this remarkable class of molecules can do.

From angler fish to lizard venom to once-weekly injection that reshaped modern medicine, the story of Ozempic is as unlikely as it is profound. A century after Banting and Best discovered insulin in Toronto, another hormone has emerged from this city’s labs and is redefining how we think about metabolism, appetite, and chronic disease. What began as a search to help people with diabetes now sits at the intersection of biology, business, and culture. This serves as a reminder that scientific discovery often takes the most unexpected paths.

& Designed by

Yashar Aghazadeh Habashi Written

> From Inbox to In Silico: > The Role of Artificial Intelligence in

Drug Development

Ask anything

Monday morning begins: you open Outlook, fix a sentence in Word, skim a new paper, and accidentally drift onto social media where yet another “personal assistant” pops up. The recent surge of generative and natural language processing models has created the sense that artificial intelligence (AI) is capable of addressing every problem we face. Naturally, this assumption extends to drug discovery and development, a scientific endeavor long regarded as a slow, expensive, and uncertain process prone to failure. However, AI’s relationship with drug discovery predates today’s chatbots. Proteinstructure and ligand-binding predicting models established the groundwork on which modern deep learning now builds upon. From identifying novel drug targets and designing potential therapeutic molecules to predicting clinical trial outcomes, recent advances in AI offer a new paradigm for pharmaceutical research by accelerating and improving the efficiency of key processes involved in drug development.

Rather than listing AI’s strengths and pitfalls in drug development, the most meaningful way to understand its role in this multi-stage scientific process is to examine its application throughout the drug discovery pipeline. Highlighting its strengths, multiple biotech companies and startups are implementing AI to rethink long-standing workflows from hypothesis generation, candidate development, to commercialization stages.

Hello! What can I do for you today?

Identify a target, hit or lead?

Artificial intelligence in target identification and drug validation

Despite the rapid progress in understanding thousands of diseases, choosing the correct drug target can be a never-ending task. Human biology is deeply interconnected, meaning that a modification in a single element of a pathway can trigger unintended and undesirable effects. Even when a gene or protein appears promising, researchers must assess whether it can be modulated safely and effectively using reductive experimental setups that have a limited representation of human physiology. AI addresses such challenges in two major ways. Initially, it screens massive amounts of biological data that would otherwise take a long time to process. This allows the identification of relevant pathways and molecules contributing to disease and suggests potential gene-protein-drug relationships of clinical interest with high accuracy and speed. Innovations such as AlphaFold accelerate specialized drug design by providing high fidelity 3D protein structures and potential drug interaction binding models, which helps the development of companies focusing on specific areas. Genialis, for example, analyzes gene data to map tumor biology and elucidate cues that reveal key features of the cancer (biomarkers), as well as predict patient responses. Likewise, the biotech startup Ternary Therapeutics focuses on immunological disorders developing drugs that act like a “molecular glue”. Instead of blocking a protein’s activity, these drugs force two proteins to stick together, triggering the cell’s natural machinery to destroy the target protein associated with the disease.

Personal Assistant 1

Once a target is identified, the next challenge is to uncover drug candidates with promising biological or chemical activity: hits. Traditional brute-force and high-throughput screening approaches are increasingly evolving into virtual screening, where millions of compounds are evaluated in silico to predict how well they will attach to the target molecule (binding affinity) and not to unwanted ones (selectivity), whether they will cause harm (toxicity), and how practical they are to manufacture. A leading example is Numerion Labs, formerly Atomwise, founded by University of Toronto (U of T) alumni Dr. Heifets, Dr. Wallach, and Dr. Levy. This U of T Entrepeneurship startup developed AtomNet, the first deep neural network driven molecular screening platform, which transformed the paradigm of hit identification by predicting a compound’s biological effects from its structure. This approach has generated hits for antiviral targets, including Ebola, neurogenerative pathways, and dampening the immune system’s inflammatory signals, several of which have advanced into preclinical development stages. Following a similar approach, Insilico Medicine produced one of the first AI- discovered and -designed small-molecule drug for fibrosis to enter Phase 1. Achieving this milestone in only two and a half years underscores the radical time-to-market optimization facilitated by AI.

Notable AI tools are continuously evolving to decrease the high failure rate of promising drug candidates by re-evaluating hits and guiding iterative designs to maximize therapeutic potential. Canadian companies have become emerging leaders in biologic optimization. Based in Vancouver, AbCellera exploits information naturally encoded in the immune system by using large-scale AI to evaluate antibodies naturally produced against infection at a single cell resolution and selecting those with optimal properties for a particular disease or condition. Their ability to integrate tailored protein-prediction tools of transmembrane proteins, which span the cell membrane and act as communicators with the environment, has been key for their success as these proteins are notoriously difficult to study. Multiple antibodies have already advanced into Phase 1 clinical trials in fields such as endocrinology, inflammation, and soon autoimmunity. Together, these efforts emphasize that AI-driven discovery is not done by a solitary omnipotent entity. Proper guidance of human curiosity and intuition endorses a powerful partnership capable of transforming nature’s molecular repertoire into clinically meaningful therapeutics.

In conclusion, AI is reforming every stage of drug development. The discourse of AI as a replacement of human expertise must shift into a collaborative tool, where researchers must nurture tailored computational fluency to guide these models responsibly. Human curiosity alongside computational power will accelerate the delivery of meaningful therapies to patients in a time sensitive manner.

Do you need help transitioning this drug to market?

Artificial intelligence in clinical research and commercialization

AI’s influence is not limited to research and development, it also has the potential to reduce bottlenecks present across preclinical, clinical, and even commercial stages. The predictive modelling behaviour is a major advantage in the clinical landscape. Despite displaying favorable biological activity, most candidate drugs often fail because they lack the necessary properties for moving through the body and being safely cleared. AI simulations help filtering out compounds that are unlikely to succeed in vivo prior to animal testing. Additional models exploring imaging and multimodal data can detect subtle patterns and flag either positive outlooks or safety concerns that often escape human evaluation. Interestingly, AI’s support in clinical trials relies on identifying biomarkers linking treatment response outcomes and refining patient recruitment. Some systems may suggest a combination of treatments based on a patients’ characteristics. While traditional experimentation must not be replaced, AI enables informed decisions that may ultimately increase trial success and identify healthcare gaps that are often breached due to the overwhelming volume of biomedical data. Pharmaceutical companies believe AI could facilitate automated marketing channels in which patients with unmet needs are rapidly identified and drug differentiation strategies developed.

Although regulatory agencies like the FDA implement AI to assist in pharmacovigilance, by processing large volumes of reports, no AI-developed drug has received FDA approval. Major criticism relies on the quality of the data in which the models were trained on: “you are what you eat”. Since AI performance will be inherently reliant on the data characteristics, any biases and unrepresentative cohorts, among others, may distort predictions without being acknowledged. More importantly, many deep and machine learning models act as “black boxes”, where accurate outputs are generated without providing the mechanistic reasoning behind the scenes. The inability to trace testable motivations makes regulatory evaluation difficult and limits scientific trust.

Written by Ana Sofia Mendoza Viruega

Designed by Sophie Sun

Funding Canadian Biotech: How Venture Capital, Private Equity,

and Public Programs

Shape Our Innovation Ecosystem

1. VC vs. PE: What’s the Difference?

Every biotech company begins its journey with an idea, long before it earns a single dollar. To survive those early years, it needs quite a lot of capital and relies on outside investors. Two groups provide most of that financial support: venture capital and private equity. Although they are often mentioned together, they play very different roles in the life of a biotech company.

Venture capital focuses on the earliest and riskiest stages. These investors back young teams that are still generating preliminary data, refining their science, or entering early clinical work. The companies may have no revenue at all, yet strong technology and good biology make them worth the risk. Private equity enters much later, once a company has real products, revenue, and manufacturing capacity. Their money helps companies scale production, expand into new markets, or prepare for an initial public offering (IPO). , which is the first time a private company sells shares of its stock to the general public, transitioning from private to public ownership and listing on a stock exchange like Nasdaq, primarily to raise capital for growth, pay off debt, or provide an exit for

early investors. Venture capital sparks discovery. Private equity accelerates commercial growth. Understanding the difference is important, because Canada shines in early research, while it needs more strength in later stage capital and infrastructure.

2. The Canadian Funding Landscape: A Sector

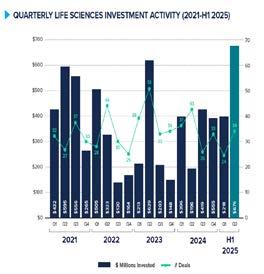

Source: Canadian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association

Growing

Despite the

Headwinds

Global financial conditions have made investment tougher in recent years, yet the Canadian life sciences sector continues to stand out. According to the Canadian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association, life sciences companies raised close to 894 million dollars in the first half of 2025 across only 58 deals. Even as overall venture activity in Canada slowed, biotech deals became larger, reflecting growing confidence in the quality of Canadian science.

This builds on strong performance in 2024, when the sector raised 1.38 billion dollars across 128 deals, surpassing the previous year despite widespread uncertainty. Investors appear willing to commit larger amounts of capital, especially to companies with compelling preclinical or clinical data.

However, the ecosystem faces important challenges. Seed and pre-seed funding, which supports the earliest academic discoveries, has been declining. Founders frequently report that laboratory space is difficult to secure, and limited access to research facilities slows the generation of the early data needed for investment. Many companies also feel pressure to move to the United States to secure larger follow-on rounds or specialized resources. Although Canada excels in basic science, gaps in early infrastructure and later stage capital make the overall path to commercialization difficult.

Even so, global firms continue to take notice. Investors from Versant Ventures and others have publicly stated that some of their most successful companies come from Canada. The science is here. The innovation is here. The question is whether Canada can build an environment strong enough to support these innovations through every stage of their growth.

3. Case Study: Lumira Ventures, Building Companies and an Ecosystem

Lumira Ventures demonstrates what a successful Canadian life sciences investment firm can look like. With offices in Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, and Boston, Lumira invests in companies at different points along the biotech journey, from early academic spinouts to ventures approaching commercial launch.

Over more than twenty years, Lumira has funded more than one hundred companies and supported over fifty approved health products. Its portfolio companies have raised more than six billion US dollars in financing and generated more than seventy billion dollars in total revenue. These include well known Canadian successes such as Aurinia Pharmaceuticals in Edmonton and Zymeworks in Vancouver, as well as major exits such as OpSens Medical in Quebec City. Each example shows how Lumira helps transform Canadian science into real therapeutic and commercial impact.

A key strength of Lumira is its multistage investment approach. Instead of focusing only on seed stage companies or only on mature ventures, it supports companies across the full development pathway. This helps founders avoid the common funding gaps that can stall progress at critical points. Lumira also invests in talent through its Venture Innovation Program (VIP), which gives PhD, MBA, and MD trainees direct experience with scientific due diligence and investment decision making. Programs like this help grow the next generation of scientifically trained venture professionals, a resource Canada needs in order to sustain a competitive biotech sector.

4. Government Funding Programs, Incubators and Accelerators

Government programs are central to Canada’s innovation strategy. Early-stage science is expensive and risky, and public support could help companies survive long enough to attract private investment. The Scientific Research and Experimental Development tax credit is one of the most important tools for young companies, offering financial relief for costly laboratory work. The Venture Capital Catalyst Initiative, created by Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada, expands the amount of venture funding available by investing in funds-of-funds managers and encouraging private sector participation. A dedicated life sciences stream has brought additional capital into the sector at a time when it is urgently needed.

Alongside these programs is a vibrant network of incubators and accelerators. MaRS Discovery District in Toronto provides advisory support, industry connections, and access to investors. Accelerators such as Techstars, the University of Toronto Entrepreneurship Hatchery, and the national Lab2Market program offer structured training and mentorship. Lab2Market is especially valuable for academic teams, helping researchers assess whether their discoveries can become real companies.

5. Conclusion

Canada’s biotechnology ecosystem is full of talent, innovative ideas, and scientific excellence. Venture capital supports discovery. Private equity enables growth. Government programs help bridge the gap between academic research and commercial readiness. Incubators and accelerators provide founders with space, community, and expert guidance. Yet the system still faces pressure, particularly in early-stage funding, laboratory infrastructure, and competition from larger markets. Strengthening every part of the pipeline is crucial in helping Canada turn its world class science into long-lasting real-world impact.

Written & Designed by

Tianning Yu

THE HIGH COST OF BEING ONE-IN-A

M I L L I O N

Pharmaceutical industry makes billions from therapies to treat rare diseases

Apatient living with a rare disease – defined as one that affects 1 in every 2,000 people – may understandably feel isolated. The number of patients that share their symptoms and struggles is inherently small. However, with around 7,000 different rare diseases identified to date, the rare disease community as a collective is surprisingly quite large.

Dr. Gregory Costain, a medical geneticist and rare disease expert at SickKids, said that “rare diseases are collectively common.” He elaborated that “when we say rare, people immediately think it’s something that wouldn’t apply to them or their family members or their community, [but] a significant fraction of the Canadian population is impacted directly or indirectly by a rare disease.”

Indeed, the Canadian government estimates that 1 in 12 Canadians live with a rare disease.1 In the past few years, the government has launched multiple funding initiatives for rare disease research, indicating a growing awareness of this patient population at the federal level.

For example, Health Canada announced the National Strategy for Drugs for Rare Diseases in 2023, promising $1.4 billion over three years to streamline the research and treatment of rare diseases. The CIHR also began a Rare Disease Research Initiative in 2024 to award grants to researchers including Dr. Costain, whose ongoing clinical trial evaluates genome sequencing as a potential tool for diagnosing rare diseases.

Costain is energized by these recent initiatives, and believes Canada fosters a productive environment for rare disease research. “Our public health care system […] gives [researchers] many advantages when we’re thinking about partnering with industry for clinical trials and for ultimately having drugs approved by our regulatory bodies,” Costain said.

In Canada, there are a few key agencies that help bring a drug to the market. First, Health Canada assesses the safety and efficacy of the drug. Next, groups like the Pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance settle on the drug cost. Finally, the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) monitors the drug cost to ensure that it is not excessive. Despite regulatory precautions, most rare disease therapies remain extremely expensive. Remarking on rare disease

drug costs, PMPRB Executive Director Douglas Clark told the House of Commons in 2019 that “the best drug in the world won’t bring value to society if no one can afford it.”

One such unaffordable drug is the infamous Soliris, an antibody-based drug that treats the rare and life-threatening blood disease paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). PNH causes extreme fatigue, anemia, and blood clots and affects only 6 in every million people a year. Back in 2009, the Canadian government approved Soliris as a PNH treatment, but this drug costs a staggering $700,000 per year.

Alexion, the pharmaceutical company that developed Soliris, faced widespread criticism for the excessive price of their drug. The regulatory agency in New Zealand refused to cover the cost of Soliris in 2013, since the price was “out of line with other comparable innovative new medicines supplied by other companies.”

After an extensive investigation in Canada, the PMPRB capped the price of Soliris and ordered Alexion to refund $11.6 million to the Canadian government in 2022. The company had generated $6 billion in revenue from Soliris sales in just 8 years since the drug’s introduction.

The Soliris case demonstrates that the rare disease research industry is highly lucrative, despite needing to market toward a small patient population. Fewer than 10% of all rare diseases have any available treatment, so each new drug treating a rare disease will likely have a monopoly. Indeed, Soliris is the only drug that can treat PNH, allowing Alexion to avoid competitive pricing.

Another company that has monopolized a specific rare disease treatment is PTC Therapeutics. In 2024, the company received FDA approval for Kebilidi, a gene therapy to treat an ultra-rare disease, aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. AADC deficiency results from a genetic mu-

tation that prevents the production of serotonin and dopamine, chemicals in the brain essential for controlling critical bodily functions such as breathing and moving. This disease currently affects fewer than 125 people worldwide, manifesting usually during the patient’s first year of life, through symptoms like seizures and an inability to hold up their head. As the only cure available for AADC deficiency, Kebilidi clearly dominates the market, costing over $3 million per treatment in the U.S.

ment of more common neurological diseases.

Costain points to Kebilidi’s success as an example of how rare disease research can advance common disease research. “Because that disease [AADC deficiency] involves a specific neurotransmitter pathway in the brain, it’s now giving us the opportunity to explore re-applying or repurposing that gene therapy to treat Parkinson’s,” Costain said. “Again and again, we are seeing these examples of rare diseases allowing us to make the large problem more tractable.”

Though expensive drugs like Soliris and Kebilidi demonstrate the danger of monopolies in the rare disease industry, they also represent considerable scientific breakthroughs. As a gene-modifying treatment, Kebilidi delivers a functional copy of the AADC gene to the patient’s brain and drastically improves motor control. It is the first gene therapy approved to be injected directly into the brain, setting an example for treat-

The scientific insights that rare disease research can uncover may outweigh the risk of burdening health care systems with expensive drugs. “I don’t think we will get all the insights we need to get in the more common diseases from studying rare diseases, but in our opinion, that’s been one economic and scientific justification for the investment that we are making,” Costain said.

Written by Annie Mitchell

Designed by Larissa Abdallah

CAR-T Therapy: When medical breakthroughs bear steep price tags

In 2010, five-year-old Emily Whitehead was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), a type of cancer that affects white blood cells. After years of intense chemotherapy, bone marrow transplants, and repeated relapses that seemed to defeat all hopes for remission, Emily’s parents brought her to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia in a final effort to find a successful treatment. There, a clinical trial was underway to test chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T therapy, a novel cancer treatment that was largely unheard of at the time. In 2012, Emily became the first pediatric patient to receive this therapy – and thirteen years later, she remains cancer-free and lives a normal teenage life.

Emily’s recovery sparked global interest in CAR-T therapy and demonstrated its potential to treat otherwise incurable cancers. Since then, thousands have benefitted from this treatment. As of 2019, five CAR-T therapies have been authorized in Canada for the treatment of various blood cancers, including certain types of leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

However, implementation of CAR-T therapy remains challenging from logistical and financial perspectives, especially when considering, a single infusion for a patient can cost roughly $400,000 to $500,000 CAD. This article explores the science behind CAR-T therapy, the extensive manufacturing process that contributes to its high cost, and potential strategies that may render CAR-T therapy more accessible and affordable for all.

What are CAR-T cells and how are they made?

As its name suggests, CAR-T therapy is based on a type of immune cell known as the T cell. These cells play an important role in detecting abnormal or unhealthy cells, including cancer cells, in our body. CAR-T therapy harnesses this natural function of T cells but provides them with an extra “boost,” allowing them to become more potent and effective cancer cell killers.

The development of CAR-T therapy begins with isolating T cells from the blood of a cancer patient: a process called apheresis. These cells are then genetically engineered to express chimeric antigen

receptors (CARs): synthetic proteins located on the surface of T cells that enable them to specifically recognize cancer cells. The modified cells are further expanded in the lab to produce millions of CAR-T cells, which are reinfused back into the patient. Once infused, CAR-T cells can circulate throughout the body and attack the tumour cells present. CAR-T cells can also persist for years after the initial infusions, remaining armed for attack if the cancer attempts to re-emerge.

Challenges of current manufacturing practices

CAR-T therapy is unique because it must be manufactured on a patient-specific basis. Each patient’s T cells must be individually harvested and modified in specialized facilities, which requires highly skilled labor and quality control to ensure safe manufacturing processes. In Ontario, four healthcare centers currently offer CAR-T treatment. Once apheresis is completed at one of these centers, the cells are shipped to the United States for CAR manufacturing– a process that can take weeks to months before the final CAR-T product is ready to be infused back into the patient. Following the treatment, patients must be closely monitored for serious side effects such cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (iCANS). These complications can occur when the

immune system goes into overdrive, causing the release of an overload of inflammatory proteins called cytokines. CRS may present symptoms including fever, fatigue, and shortness of breath. iCANS occurs when these cytokines cross the blood–brain barrier and enter the cerebrospinal fluid, causing neurologic symptoms such as tremors, confusion, and in severe cases, seizures. Both CRS and iCANS can be fatal if not managed appropriately.

Altogether, not only is CAR-T cell manufacturing time-intensive, expensive, and resource-heavy, but the frequent follow-up appointments required to monitor these side effects further add to the overall burden on both patients and the healthcare system.

The path forward

As CAR-T therapy gains traction in the oncology field, the next challenge is expanding its reach and accessibility. Currently, CAR-T manufacturing follows a centralized model, in which pharmaceutical companies operate one major production facility in North America and another in the European Union. While centralized manufacturing helps maintain consistent product quality, it increases production time, reduces customer capacity, and drives up overall costs. An alternate strategy is a decentralized, “point-of-care” model, which involves producing CAR-T cells at or near the location where patients receive treatment. Once established, this approach could dramatically reduce wait times, simplify logistics, and lower expenses. In Canada, the Canadian-Led Immunotherapies in Cancer program is actively investigating ways to build a domestic manufacturing capacity, paving the way for “made-in-Canada” CAR-T therapies that are both faster and more affordable.

Developing “off-the-shelf” cell therapies may be another viable solution. This involves engineering T cells isolated from a single donor, using them to treat multiple patients at a time. Traditional CAR-T therapy is currently limited by the need to use the patient’s own T cells, which is essential to avoid the dangerous immune reactions that can arise from

introducing foreign donor cells. Thus, an ongoing area of research focuses on modifying CAR-T cells to make them safe for transfer between unrelated individuals. Scientists are also exploring the option of developing CAR therapies with other immune cell types, such as Natural Killer (NK) cells and invariant Natural Killer T (iNKT) cells. Similar to T cells, NK and iNKT cells have the capacity to kill cancer cells but with lower risk of triggering adverse effects. If successful, offthe-shelf approaches could transform CAR-T therapy from a highly individualized treatment into a scalable, ready-to-use product that is accessible for patients around the world.

For Emily Whitehead, CAR-T therapy meant the difference between exhausted treatment options and a cancer free life. When striving to create more success stories like this , it’s important to ask ourselves not only how we can push the scientific frontier to develop novel treatments, but how we can ensure these treatments are accessible to patients across the globe.

Written by Milea DiPonzio

Designed by Zoeen Carter

Today we’re joined by Juan Mauricio Umaña, a Master’s Immunology Program and Mallevaey lab alumnus. Juan has worked at BlueRock Therapeutics for over six years, first beginning as an Associate and later growing into his current role as Principal Research Associate. His work is split between wet lab - where he leads experimental design - and a managerial role, where he drives projects from conception to execution.

Juan Maricio Umaña: the path from a Master’s Degree to Principal Research Associate at BlueRock

Therapeutics

Can you tell me about your role and what your day-to-day routine looks like?

“It’s a very collaborative environment,” Juan explains. “As a Principal RA, I help design experiments alongside my team, define what questions we want to answer, and drive the projects forward. It’s not just about doing one experiment at a time- it can be about managing an entire research process!” His schedule balances both hands-on lab work and planning. Roughly half of his week is spent conducting experiments, analyzing data, and writing experimental workflows; the other half involves meetings and discussions to guide research direction. “It’s about asking the right questions, planning the next steps, and making sure what we do fits within the bigger project timelines,” he adds.

Sounds like what you’re doing now is like what you did during your graduate degree... what kind of differences are there being in a more business-adjacent setting?

While the scientific curiosity and structure of his work feel similar to graduate school, Juan notes several key differences in the industry setting. “In grad school, you’re often the entire team,” he says, “you do everything by yourself. In industry, everything is collaborative. You lean on other people’s expertise, and you don’t have to reinvent the wheel every time.”

He also highlights the importance of structure and planning. “In grad school, you can sometimes take more time to explore different approaches. But in industry, your work is often part of a bigger puzzle. Others depend on your results. Timelines matter. If you’re developing an assay, for

example, you need to plan when it’ll be ready so that you can hand it off to the next team.”

Being in grad school can be great for picking up soft and technical skills – which ones do you find have been helpful in your career now?

Juan credits his Master’s degree for shaping both his technical and soft skills. On the technical side, he mentions experimental design, flow cytometry, and meticulous documentation. These are skills that translate directly into his current role. “In grad school, I was a bit loose about documenting experiments,” he laughs. “But in industry, that’s crucial. Everything must berecorded in detail so that anyone can replicate your work.” He also emphasizes communication and adaptability. “Grad school teaches you how to present complex data to different audiences. In industry, that becomes even more important. When I present to my manager, I might go into detail. But if I’m talking to executives, I need to focus on the key outcomes that help them make decisions.” Another major takeaway from graduate school was mentorship. “I was a TA and had undergraduates in the lab, and that really helped me learn how to teach and lead,” Juan reflects. “Now, mentoring junior associates or co-op students is a big part of what I do. It’s rewarding to help others grow while also learning from them.”

An important question for those of us graduating soon… how did you find your position?

Juan’s path to BlueRock Therapeutics came naturally from his academic background in immunology. After finishing his MSc, he completed a six-month research position in transplant immunology at UHN before discovering the opportunity at BlueRock. “I think the stars aligned,” he recalls. “They were looking for someone with an immunology background, and I was fortunate to have the right combination of skills and experience. But I also believe in the idea that you create your own luck... you know what they say, opportunity is when luck meets preparation.”

Thank you for your time today! Any last advice for current graduate students?

Juan’s advice centers on humility, patience, and a willingness to keep learning. “Be receptive and patient,” he says. “Science is about realizing how much you don’t know. The more you learn, the more you understand how little you really know—and that’s okay.” He also stresses the importance of transparency and initiative, especially when working with supervisors or managers. “If you make a mistake, be upfront about it. That’s how trust is built. And when you bring a problem to your manager, come up with po -

tential solutions too. It shows initiative and maturity as a scientist.” Finally, he encourages graduates to stay open to growth. “Even now, I’m learning new technologies all the time. The field evolves fast, and you need to evolve with it. Stay curious and adaptable—that’s what will carry you forward.”

Juan Mauricio Umaña’s journey from MSc student to Principal Research Associate reflects how a foundation in curiosity and collaboration can lead to a thriving career in the industry. For students that wish to hear more about his experiences during his graduate studies or during his current position at BlueRock Therapeutics, Juan has consented to being contacted through his LinkedIn profile.

Written by Vera Lynn

Designed by Ria Menon

Spinning Out: highlighting companies that bridge the translation gap from academic discovery to biotechnology innovation

The field of biotechnology, or more commonly known as “biotech”, implements the use of living organisms to develop applications intended for improving human welfare. Medical biotech companies pursue or license in scientific discoveries to produce tangible benefits for healthcare such as therapeutics, diagnostics, and vaccines. In some cases, these companies emerged from a novel technology with the potential to improve human health, inspired by a discovery that has been “spun off” from an academic lab.

Laboratory trainees, like us, stand at the start of many of these breakthroughs by coming across findings that show great potential. This is the start, but it is not simple to commercialize a technology. There are numerous steps with complex legal jargon to follow once the process is started. Here, we will highlight some major components in this process: First, it’s important to determine whether commercialization is viable. The next steps that follow include building a founding team, negotiating with the technology transfer office, obtaining rights for intellectual property (IP), hiring advisors and employees, and acquiring funding. Luckily, many universities strongly support commercialization of scientific technologies with established programs to aid startups.

Start-Up Resources

At University of Toronto, we have an entrepreneurship community which consists of 12 innovation hubs called Accelerators, geared towards providing support, resources, and partnerships in various fields. University of Toronto Early-Stage Technology is an accelerator that focuses highly on partnership and funding, with ties to the surrounding hos pitals, MaRS Discovery District, and Toronto Innovation Acceleration Partners (TIAP). At UTM, SpinUp, termed a “wet lab incubator”, provides early-stage resources, such as subsidized lab and office space, to allow startups to focus on developing the IP. These programs are designed for building up entrepreneurship and bridging the translation gap from research to technology.

Biotech Metrics

When comparing these spin-off companies to the overall biotech sector, we can look at a few metrics. Approximately one-third of biotechnology firms originated as spin-offs, with the majority originating from academic research institutions. Spin-offs are typically smaller and have a greater focus on research and development compared to well-established biotechnology firms. While most spin-offs do not grow into large, public companies, the bulk of them have high survival rates at 5 years, and some even longer.

Radiant Biotherapeutics

Our very own Immunology department is home to labs that founded a major spin-off biotech, Radiant Biotherapeutics. The research conducted in the labs of Dr. Jean-Phillipe Julien and Dr. Bebhinn Treanor resulted in a patentable technology called Multabody. Multabody is an antibody platform with the “mult” in the name referring to its multi-valent and multi-specific properties. The basis behind this innovation utilizes apoferritin, a human scaffold protein that can self-multimerize, which when combined with antibody fragments can assemble into a multimeric structure. The technology is modular meaning that the antibody fragments can be swapped out depending on the target. Because of this, Multabody has a wide range of potential therapeutic targets. Radiant Biotherapeutics’ current pipeline includes targets in oncology, inflammation, and HIV. In their oncology portfolio, their lead clinical candidate is RBT-101, a 4-1BB agonist. Recently presented at the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer 2025, it was highlighted that RBT-101 could induce tumour regression without liver toxicity in a mouse tumour model. From this, Radiant Biotherapeutics will continue to develop their lead oncology program, as well as other Multabody platforms for therapeutics in disease.

Triumvira Immunologics

UofT is not the only place where academic research fuels industry. Triumvira Immunologics is a biotechnology company founded in 2015 by Dr. Jonathan Bramson at McMaster University. Their major focus is cancer therapeutics, with their main proprietary technology being the T cell Antigen Coupler (TAC) molecule. The TAC molecule is a chimeric molecule with 3 domains: the antigen binding domain which binds to the tumor cells, the CD3 binding domain that interacts with the T cell receptor (TCR), and the CD4 Co-Receptor Domain, which is the proprietary component of the Triumvera technology. The CD4 Co-Receptor Domain is what anchors the TAC molecule into the cell membrane and is responsible for activating the immune response. The company’s leading clinical candidate is TAC101-CLDN18.2, an autologous TAC program that uses a patient’s T cells genetically engineered with a TAC molecule to redirect T cells to target tumors expressing Claudin 18.2, a protein on solid tumors. Preliminary results from a phase I/II study were presented at 2025 ASCO Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium and Triumvira is continuing to develop this candidate as well as others to diversify the applicability of the technology in cancer treatment.

More Spin-offs...

A few other companies that have “spun-out” include Notch Therapeutics, a company using stem cell-based technology to develop cell therapies in cancer application, founded by Dr. Juan-Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker and Dr. Peter Zandstra, also formerly from UofT. Dr. Nathan Magarvery founded Adapsyn out of McMaster University to leverage bioinformatics to discover novel molecules with potential for benefits in various therapeutic areas, agriculture, and nutrition. Perturba Therapeutics was founded by combining the discoveries from Dr. Igor Stagljar’s lab at UofT with AI-augmented chemistry technology from a biotech company called Cyclica. Finally, within the past year Lunar Therapeutics was founded out of University of British Columbia, focused on cell therapies.

Overall, “spin-off” biotechnology companies are a small portion of the biotech world, but they represent the vast potential of academic research in scientific progress. The process to commercialize a discovery is a long process but has the potential to produce great benefits in healthcare. Ultimately, Canadian academic research labs spinning out into biotechnology companies are essential in bridging discovery to translational applications.

Written

& Designed by

Alina Mehra

From Coast to Coast: Canada’s Growing Immunology and Biotechnology Landscape

Canada is a country defined by its sheer size, which gives rise to diverse landscapes and distinct regional cultures. From the wet and temperate mountains of British Columbia, across the open plains, to the densely populated cities of Ontario and Quebec and the rugged seaboard of the Maritimes, Canadians have established communities within every region. Although each are distinct from one another, a common thread across these communities is a shared passion for science, discovery and biotechnology. This passion takes form not only in the nation’s vast network of universities, research centres, and large-scale foreign pharmaceutical company sites, but also in the creative and innovative biotech companies founded on Canadian soil.

It takes just one dedicated individual, or team, with a single idea to harness their creativity and scientific knowledge to bring an idea into reality. As novel discoveries are made and technologies are applied in new ways, the scientific foundation for new biotech companies constantly evolves. Of all the fields guiding these innovations, immunology stands out as one that has never been more relevant in the current landscape. Across Canada, this is reflected in the rise of biotech companies translating breakthroughs in immunological science into life-saving therapies and diagnostics - from West to East.

Vancouver, BC: Zymeworks

Starting far off in the West, Vancouver is home to one of Canada’s most successful biotechnology companies, Zymeworks. Zymeworks specializes in the design, development, and production of antibody therapeutics that treat cancers, autoimmune disorders, and inflammatory diseases. Zymeworks’ success lies in their ‘Azymetric’ antibody design platform, which enables the design and screening of highly customized antibodies capable of safely and effectively targeting specific tumour cells.

While this technology has led to the development of a diverse array of antibody shapes and forms, Zymeworks has achieved particular success with ‘bispecific’ antibodies which target a given protein in two distinct regions for increased specificity. This approach led to the development of zanidatamab, an antibody targeting the HER2 protein, commonly overexpressed in many metastatic breast cancers, which received accelerated approval in 2024.

Beyond zanidatamab, Zymeworks also specializes in the design and development of antibody drug conjugates, which involves binding antibodies to drugs for increased delivery specificity. By developing novel targeting and conjugation techniques, Zymeworks has effectively created a versatile “toolbox”

that allows scientists to mix and match antibody specificities with different drugs, leading to several new therapeutic candidates. With multiple drugs in clinical and preclinical development, and ongoing collaborations across the pharmaceutical industry, Zymeworks stands as a beacon of Canadian biotechnology driving global innovation.

Toronto, ON: Noa

Next, a prime example of Canadian innovation exists directly across the street from the University of Toronto campus. The MaRS Discovery District is North America’s largest urban innovation hub and home to many medical, engineering, and information technology start-ups. Among them, Noa Therapeutics exemplifies how Canadian researchers are tackling chronic, immunological diseases from new angles. Their mission is to develop long-term and effective treatments for chronic inflammatory diseases by harnessing the power of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), a protein involved in the regulation of immunity, metabolism, and barrier function genes. Inflammatory diseases are hallmarked by the dysregulation of these systems, and as such, through

fine-tuning of AhR activity by designing and developing targeting-drugs, the company aims to restore immune system and barrier balance.

Noa has developed a discovery engine to screen for safe and effective AhR targeting compounds, which has led to their current lead candidate, NOA-104, an atopic dermatitis therapeutic currently in pre-clinical testing. While still early in development, Noa’s work is already generating buzz; this is evidenced by the Catalyst Research Grant recently awarded by the National Eczema Association to Johns Hopkins’ University Department of Dermatology to fund in vivo studies of the compound.

As one of many promising ventures within MaRS, Noa highlights the opportunity for creative, early-stage experimentation in Canadian biotech sphere and exemplifies how Canadian

innovators are pushing the boundaries of translational science from the lab bench to the real-world.

A common use of computational methods is in early-stage discovery and design, and is a key component of Montreal-based Cura Therapeutics’ discovery platform. Cura Therapeutics is working to develop next generation cancer and age-associated disease immunotherapies through the design of single drug compounds capable of targeting disease from multiple angles. Notably, their platform integrates AI-driven predictive protein modeling with immune functional assays to bioengineer and optimize these therapeutic molecules. Their leading candidate, CT101, is shown to have immunostimulatory, anti-metastatic, and anti-angiogenic properties, making it potentially the first of its kind if approved. Cura is now expanding its AI-driven discovery platform to design drugs for additional diseases, showcasing how Montreal’s growing computational science ecosystem is accelerating the creation of innovative therapies that address diverse and complex diseases effectively.

Halifax, NS: MedMira

Finally, although often considered more remote and secluded, the Maritimes offer unique advantages for establishing biotech companies that represent Canada on the global stage. A lead example is MedMira, a company developing the next generation of rapid diagnostics for sexually transmitted and emerging diseases, including COVID-19.

Built upon the immunological antigen-antibody interaction, MedMira’s products uniquely detect multiple biomarkers of a given disease on a single test, allowing for highly specific, rapid, and accurate testing. MedMira was founded by graduates of Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia in

1993, and has remained headquartered in the province since. Its co-founder cites a steady stream of talented local graduates and proximity to both the U.S. and Europe markets as major advantages of their location. MedMira stands as a testament to how innovation and global impact can thrive even outside major urban centers, highlighting the depth and reach of Canada’s biotechnology ecosystem.

Moving slightly east and just a short train ride away to Montreal, another innovative technology hub is rapidly expanding. What’s unique about Montreal, however, is its emergence as Canada’s artificial intelligence and machine-learning centre. Given this, computational expertise is increasingly being integrated into biotechnology development in the city, including in emerging immunotherapies.

From Vancouver to Halifax, Canada’s biotechnology landscape reflects a nationwide spirit of innovation grounded in scientific excellence. Whether through antibody engineering, immunomodulatory drug discovery, AI-driven therapeutics, or rapid diagnostics, Canadian biotech continues to push boundaries and transform immunological research into real-world medical solutions.

Written by Anthony Piro

Designed by Victoria Sephton

When we observe the previous winners of the Nobel Prize, it becomes immediately apparent that open collaboration, and a drive to improve humanity’s fight against disease are important factors of conducting impactful science. Sharing her views on the future of CRISPR and gene editing, Dr. Jennifer Doudna states: “The research that I’ll talk about today wouldn’t have happened … if I had been working anywhere else. And that’s because we have a really collaborative environment on our campus”. Her collaborative approach to science is further reflected in her joint work with Dr. Emanuelle Charpentier for the engineering of the CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing system which won them the Nobel Prize in 2020. On the other hand, when thinking about establishing a successful company, founders and entrepreneurs alike typically think of ways to beat the surrounding competition. Unlike the language used to describe scientific discoveries, war-like terms are often incorporated in business-speak such as “disruptive”, “competitive”, and “strategic”. Contrasting perceptions of what drives successful science versus a profitable business might lead one to believe that a scientific mindset is incompatible with strong business acumen. In some cases, this may be true. However, the founding of Novo Nordisk – currently the world’s largest biotechnology company – shows us that competition and collaboration can paradoxically work together to foster business growth and propel the healthcare of humanity forward.

Following his Nobel Prize win for discovering the mechanism of blood perfusion through capillaries, the Danish scientist Dr. August Krogh went to give lectures at universities on the American east coast. Persuaded by his wife who had been struggling with type 2 diabetes, he made a special stop at the University of Toronto to meet Frederick Ban-

ting, Charles Best, and John Macleod – scientists who had successfully isolated insulin that could be used to treat diabetes. Motivated by his wife’s condition, Krogh managed to receive their permission to manufacture active insulin in Europe. Then in 1923, he partnered with a diabetes expert, Dr. H.C Hagedorn, and a pharmacist, August Kongsted to establish the Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium in Copenhagen. The goal of this company was humanitarian in nature: firstly, to produce insulin at scale to help patients with diabetes, and secondly to advance science through the creation of grants funded by the company’s profits.

As Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium expanded, internal conflicts began to occur. In 1924, Hagedorn fired a valued chemist at the company, Thorvald Pedersen, due to a disagreement, which also led to the resignation of his brother, Harald Pedersen. The Pederson brothers wanted to continue the Nordisk Insulinlaboratorium’s mission of making insulin and decided to compete with the incumbent. August Krogh famously told Harald “you’ll never manage [to make insulin]” – words that would inevitably come to back to bite him.