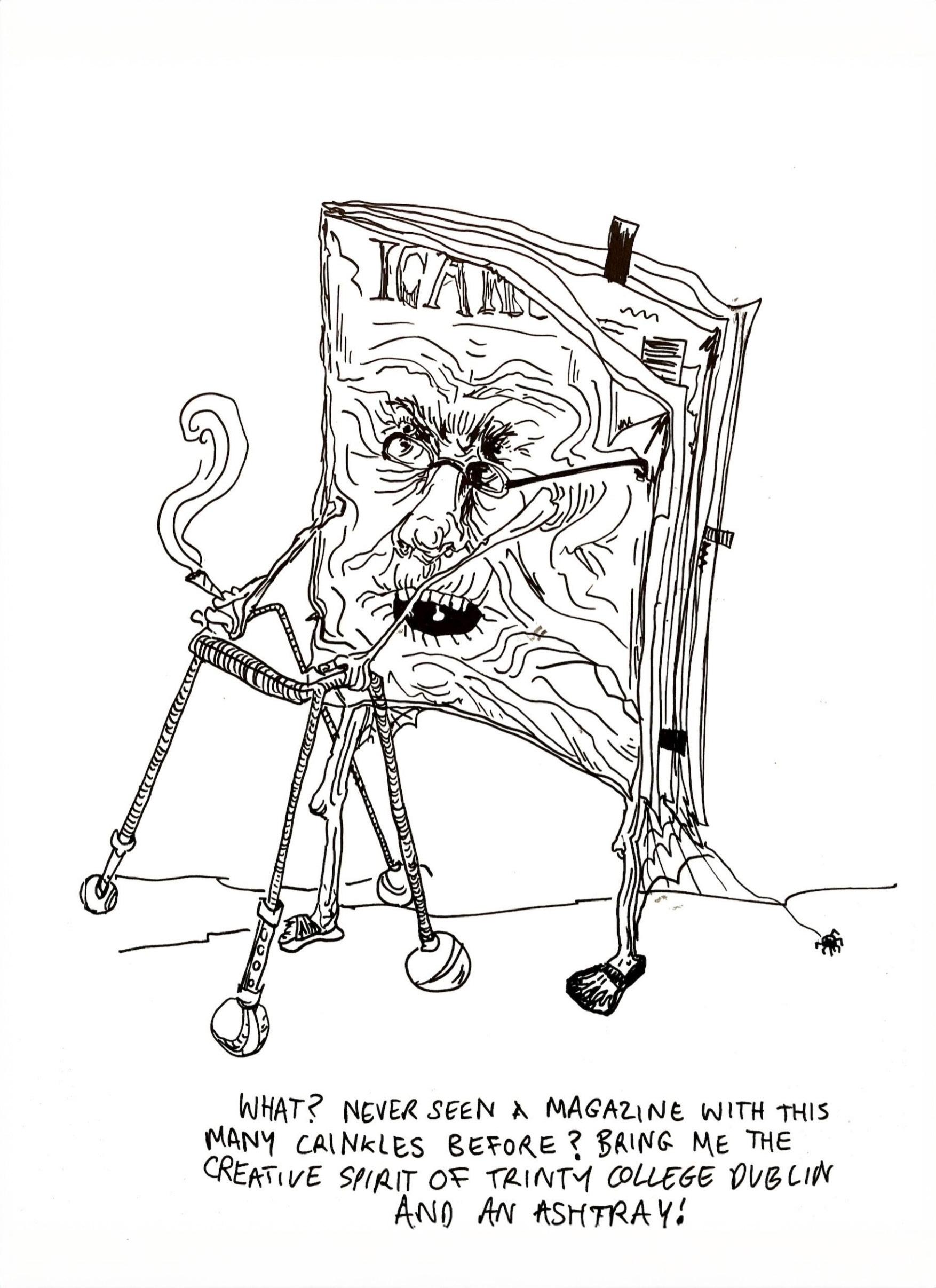

ICARUS VOL LXXVI

I C A R U S MAGAZINE

Trinity Publications 2025

FOREWORD

Question: Why does Icarus exist?

If you are reading this, there is a strong chance you may have muttered this phrase before. You may even be thinking it now; we know we sure am.

Answer: To nourish and showcase the creative excellence of the students, staff, and alumni of Trinity College Dublin.

But what is excellence, anyway? Here at Trinity we seem to be obsessed with ‘excellence’ of the most boring kind. There are prizes for those who enter this College with the best high school grades, who agree to sit optional exams - during their Christmas holidays! - in order to see who can claim the highest score on them, who maintain the strongest grade average in their discipline by any means necessary. Until very recently, we were called to graduate in precise order of what we scored on our degree - Gwen can remember the day they finally decided to take mercy upon us, and she’s still a teenager (basically). You also may have noticed that seemingly every last publication at Trinity is the oldest [insert publication type here] in Ireland. But we wouldn’t know anything about that.

This kind of excellence, though, – the kind that sits pretty on a CV, or mesmerises the simple cognitive function of the American tourist – is not the only form of excellence. Nor is it the truest.

To be excellent – as in, to be one who excels – means nothing more than to go further than everyone else. After all, people seem to forget that Icarus is named for the child who flew both higher and lower than anyone ever had before, who seemed much less concerned with the direction of travel so much as the extremity of single-minded distance.

Within the depths of this first issue you will find artworks that go as far as they can, and then some. Artworks which question whether there even is such a thing as ‘going too far’; artworks that rise up to the sky until their paint peels like sunburnt skin, or sink to insurmountable depths until their heads explode, that leap backwards from 50 storey buildings whilst burning alive; artworks that go and go and go and go until their feet crack and their back splits in two and even then they keep crawling; artworks beset upon by brigands in the alleyways of the late Dublin night, that fight until their very last drop of blood spills onto the pavement rather than forfeit their meagre possessions; artworks that will keep chasing you, maintaining an exact and consistent distance all the while – too near to forget, but too far to confront - until you are on your deathbed and they seize their moment to strike.

Our time is short. The window that connects you and us is closing. But if we could leave you with a final message as you journey onward to the rest of the issue, it would be this:

There are many paths to excellence. Up is not the only direction.

Plus Ultra!

Gwen & Eileen

'Ireland's Oldest Arts Magazine'

Palimpsest

This

Ouroboros

Unrobing

A Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

There's a Wolf at your Door that you Choose to Ignore

Death of a Motel Acolyte

In Sublimation

In memory of you

Mary Jane (el)

Clockwork Orange

The Diffiteor

Tara

Íde Simpson

Flora Leask

Louis Malaurie Wan

Claire Hennessy

Masha Lyutova

Alannah McElligott Ryan

Maja Hamidovic

Isabel Hernandez

Darragh Murray

Alice Weatherley

Julian Lovelace

Nina Isles

Elias Doering

Benny Zapruder

Lorena Martins

Isabel Norman

Conor Hogan

Jessica Sharkey

Luke Opalack

Elias Doering

Anne Grundy

Genevieve Dineen

Jennifer Greene

Saoirse Dunlea

Saffron Ralph

Mackerel Fishing in Kenmare remembering.

Pas De Deux

Mimesis

Dart Train from the water.

I Saw a Woman Dancing in the Street Today

Sacred Heart Statue on Cathal Brugha St.

The Dust of This Land Which Kills Poisonous Reptiles

Amy Kennedy

Maggie Kelly

Laura O'Grady

Sophia Allen

Masha Lyutova

Elias Doering

Oscar Downes-Banda

Nina Isles

Cat Grayson

James Grace

Giulia Vittore

Rebecca Gutteridge

Rachel Hughes

Masha Lyutova

Harry

Verdiana Karol Di Maria

Mwan

Loretta Farrell

Gavin Jennings

Ryan McLean Davis

Spells Doom

Doireann Ní Ghríofa

Josie Giles from Once from ceud beinn / a

Josie Giles

Chen Chen

Chen Chen

Chen Chen just in case

Wild Things Like These by Íde

Simpson

Divorced from chasing you down the sun-beaten track, we need nothing from each other now. Instead, wade through eelgrass, rockpools clouded by shadows of seafoam, bays clustered with toppers capsized, potbellies to heaven. Lough’s spit over your toes, black-headed gulls grope for land, the severed head of Stella Maris lies cracked across your driveway, punctured by tyre, and stone-faced to the tarmac.

I could never imagine you making a bed, but tonight, you make mine for the next stranger to darken your door.

Even the foxgloves have waited for you this year, folded against the garden wall, reaching for your mouth. They are moonstruck like me, howling to the void, drooping in the evening light before you take scissors to their necks as a warning that no good can come from wanting. On the round drive home, I forget my name. Instead, picture you at the water’s edge, kneeling to the infinite tide, stooped at its mercy.

Fingers to your lips and then to mine, pools of it dammed in your hands; you drink.

Bottoms up, and the devil laughs.

Tail white in surrender, sea eagle flies over an undecided landscape still laughing lopsided on the wing.

The professor, a prophet of doom, says that salmon used to live here, see their ghosts slapping the stone, their shapes absent from the foam? Now missing the rhythm they imposed, the water moves confused, alone.

Acharn Farmhouse by Flora Leask

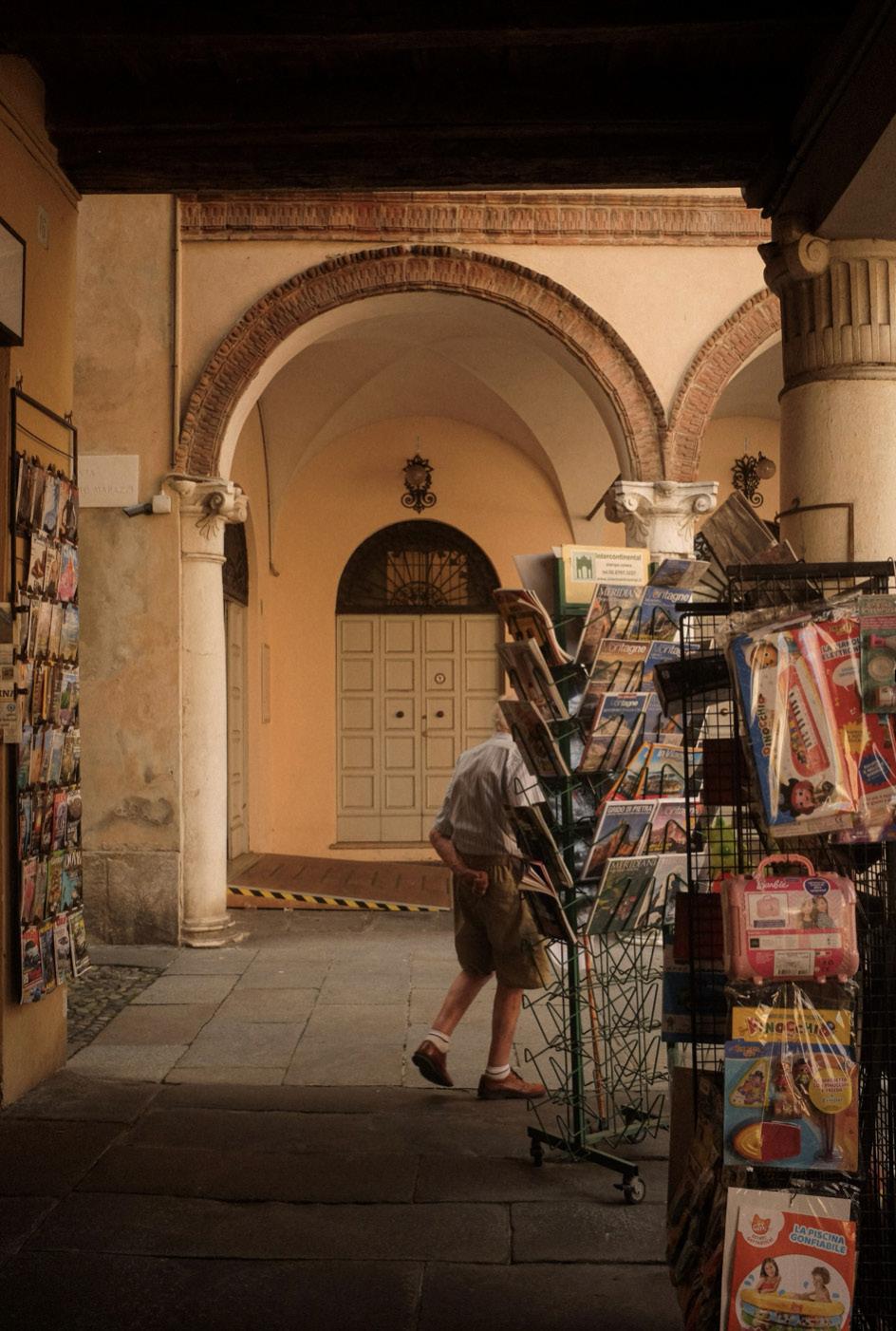

Colico by Louis Malaurie Wan

dots, joining the by Claire Hennessy

‘Rejoined’ (Star Trek: Deep Space Nine season 4, episode 5), aired Oct 1995 in the US; May 1997 in the UK/Ireland.

Books don’t turn kids queer. Don’t be ridiculous. For that you need television – discount lesbians on a space station orbiting a wormhole that swirls deep as a Georgia O’Keeffe painting. You need to be eleven years old, with your favourite character a little more flustered than usual as her ex-wife turns up to do science or something (no one cares about this bit of the plot).

In past lives and different, straighter bodies, they loved, lost, but now the laws of their alien society forbid them to reunite (it’s a whole thing with immortal slugs, don’t ask) and no one says, wait, but they’re both women –

You’re too young to wonder if they should, to even notice it. All you can think is they’re going to kiss oh my god they’re going to kiss they’re going to kiss (and they do).

On this show, the wormhole cuts through space. In a matter of minutes, a ship can glide inside and arrive on the other side of the galaxy. Ninety thousand light years, a journey of decades unless you discover this opening, this safe passage.

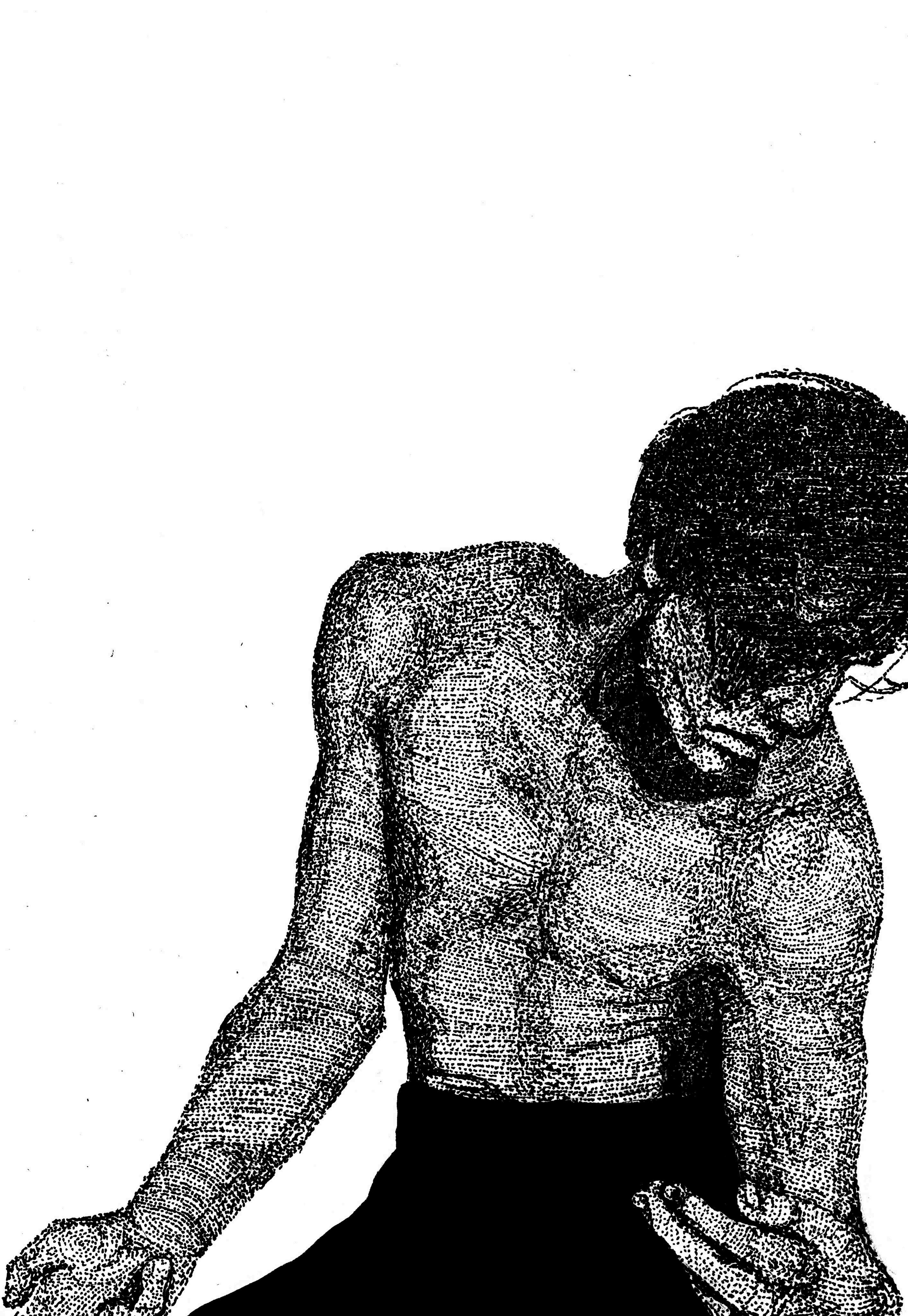

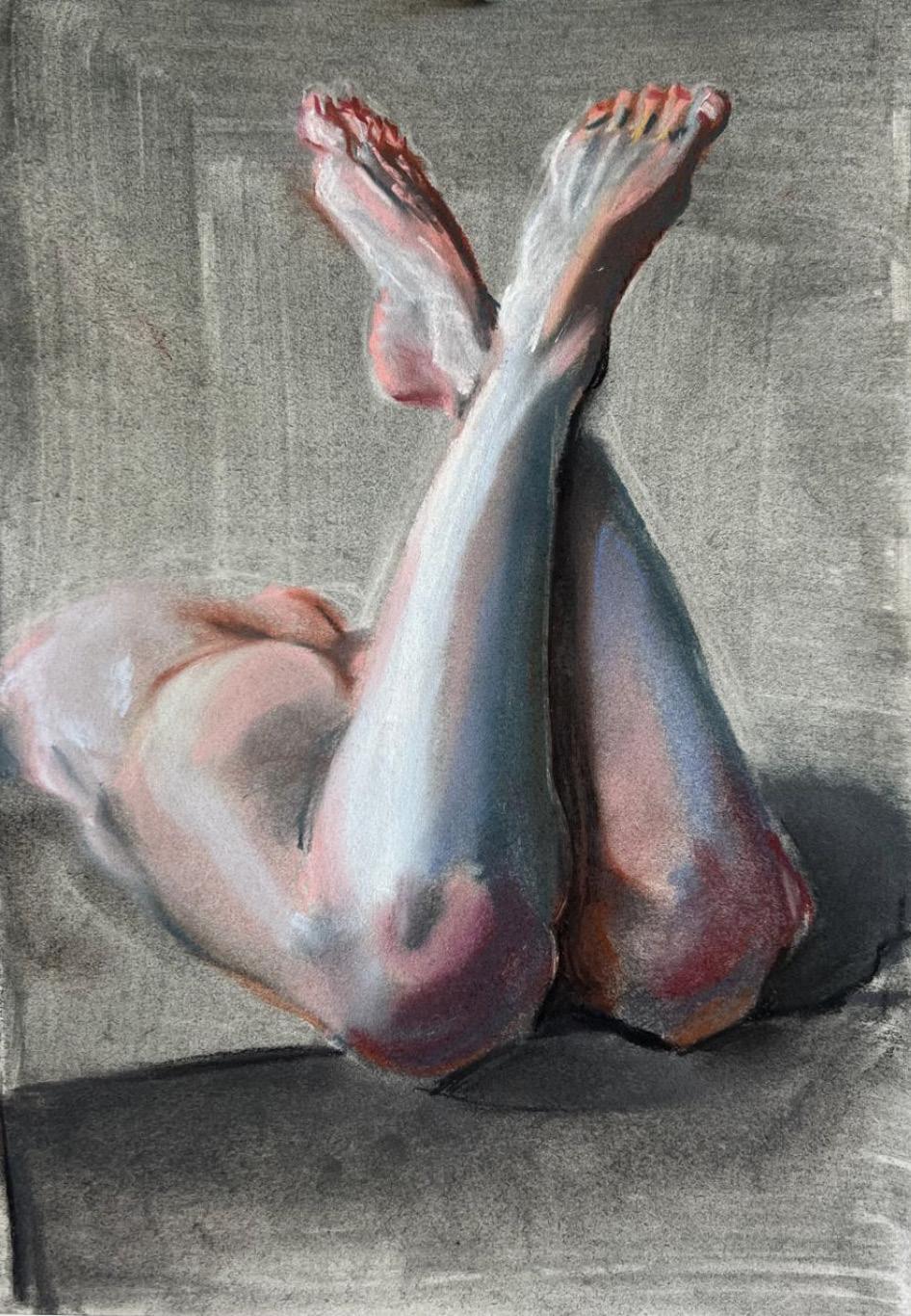

Legs by Masha Lyutova

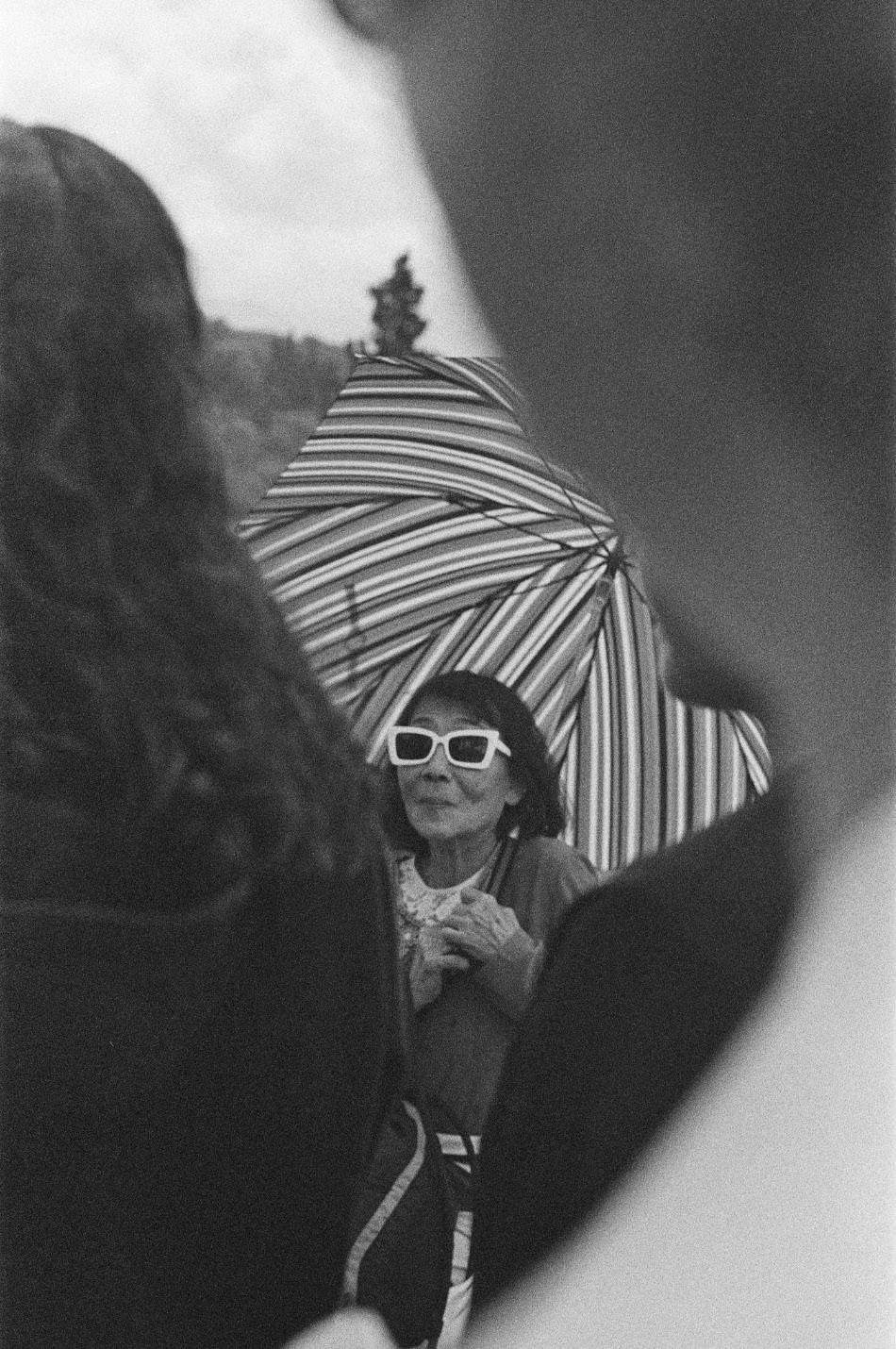

Heatwave in Stephen's Green

by Alannah McElligott Ryan

Oh it’s warm out…

So warm that all the World sighslanguishes her hands in the air, and gives up the hard-lad act; she resigns to being a resting place.

Spend the day on ground; on earth, The sun is intoxicating, cauterizing the flow of inhibitions, bursts the dam to Elysium, hot air simmers social cues: decorum brûlée recline on the streets; on shoulders so pliant. In brain-boiling skin-kiss haziness, even the seagulls are laughing at this funny business.

Untitled by Maja Hamidovic

Men in Prague by Isabel Hernandez

I wait,

Unbound as I may be because I spoke with the tin foil hat. And with the artist who is half-hung by some jury. And with the lack of teeth that breaks the silence in a train carriage.

And I think: I should like to live like that.

Like the wail of the man in a roundabout, Which the night manager shows - not tells.

And later, over crossed arms, We will wax on about when we had time to watch. And wave.

Before a splinter from America’s dying ebb, Spoke separately – at me and at him –

About the maddened cry of a village idiot with names we can’t comprehend.

And I’ll think that I should like to live like that too.

Unbound as I am because the artist wants to speak with me. And the tin foil hat too! They tell me the lack of teeth has new ones now, And is wanted in two days’ time, In a place left two days behind. And I like that because it makes more sense than the roundabout sounds.

But still their chatter wakes me, As Frank’s words – half-remembered – thump against my ears.

With a head awash, paralysed by pillows, Awaiting a never-coming cause, As another, Steps into the street, And rails against the dusty dawn.

by Darragh Murray

Zephyr

Fresh Fish

by Alice Weatherley

A fortnight, and the bulk of our unrealised Desire has smothered Europe. In the last hours on fertile

Tuscan ground, you emerge, bearing the gift Of a mid-morning nod. I lounge consciously, making myself fresco

For the final time, dazzling like the spoils Of war, sweating more than yesterday’s ham standing tall

On the table I’d set unprompted As you – red, lieutenant-like, slanted and slurring – drained

Linguine ribbons. Poolside, you sit And unfold yourself. At once I hear feet disturb surface and realise

I must swallow your sea, so I dive, Smash flesh down into no man’s land, but clear blue washes certainty

Over me. I smirk at the sight of blood Curling round leathered calves: pink bandages dressing your wounds.

A Rock is Growing by

Julian Lovelace

A rock is growing inside my room. It has a black mouth that cries darkly. The sound is a square with sharp corners. Every minute adds a grey-brown mottle to its surface. Mossy walls move aside to let it grow like a tree toward the ceiling. Inadvertently the rock stretches its knotty arms to pluck the flame from my chest. When it gets thirsty it draws water from the well of insomnia fed on by sleepwalkers. The rock is growing. Thin is the spring. I am a mismatched metronome devising the pace of its expansion. An actual tick a fictional breath a slashed mountain of hostile colors. Inside my room outside the world beyond the vault of red blue and green. Shedding its shuck and defense against those overgrown colonies of arthropods. A rock is growing. The room is dwarfed. I am involved.

Shell by Nina Isles

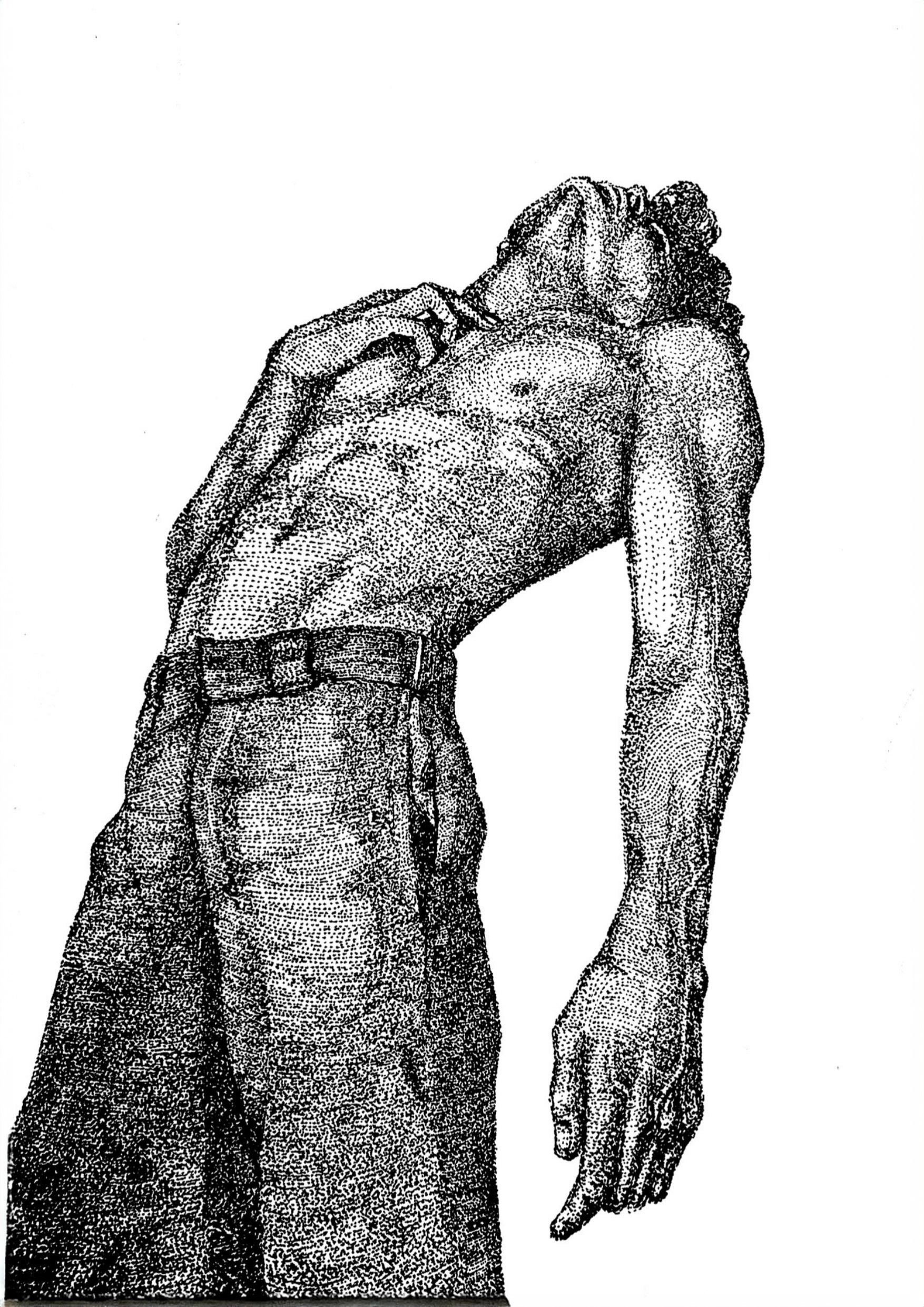

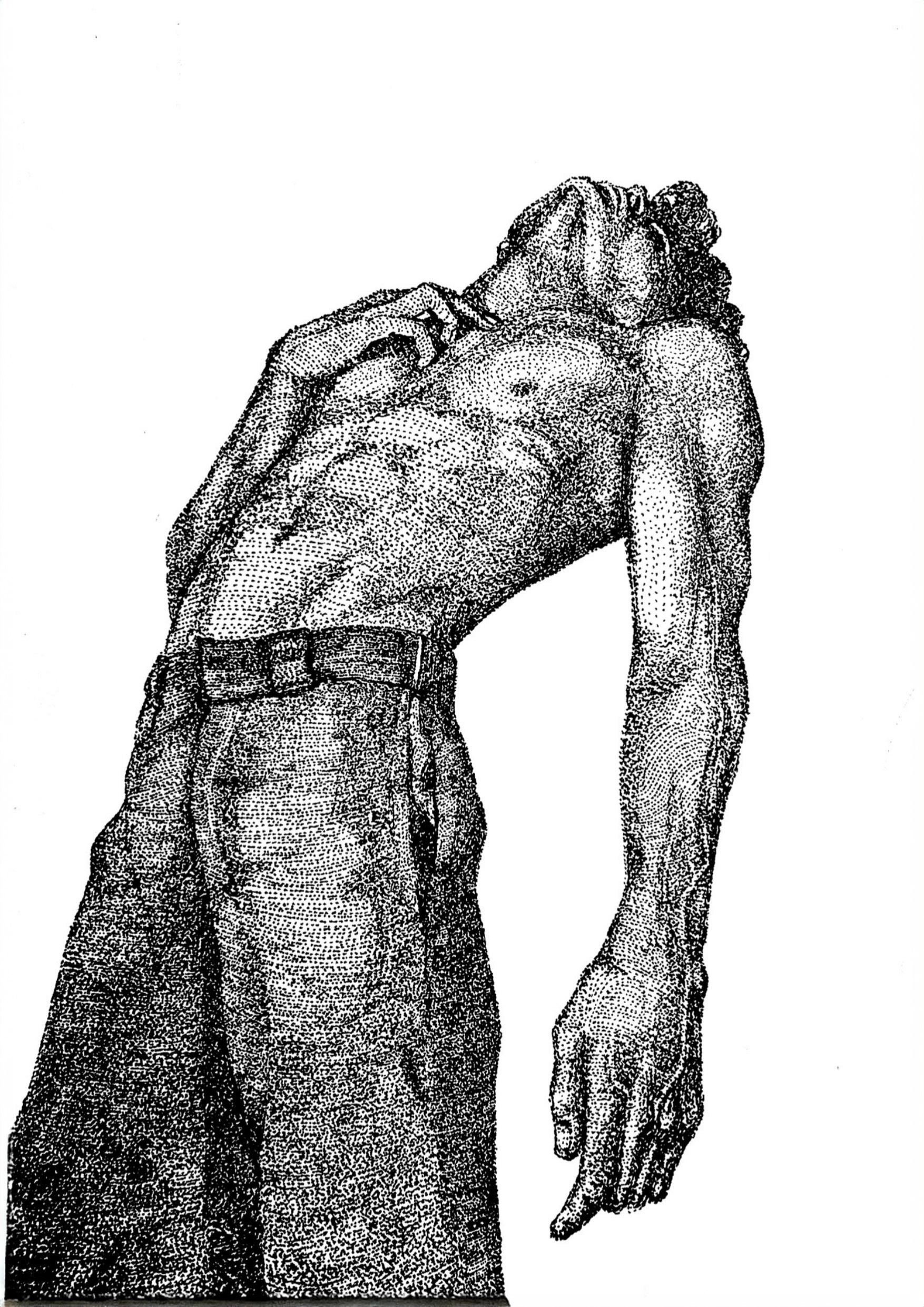

Palimpsest by Elias Doering

A quivering drip

This morning I awoke with a hole in my skull

by Benny Zapruder

Cut three sheets from its hole my brain warbs behind me.

Master and vassal

It speaks to history as I wander the streets: seeped in yesterday’s wash that ossified eyes no longer see. The yawning chasm a presentiment of past sensations.

Dripping my time across the soaked concrete to be washed away

adrift among the bloat.

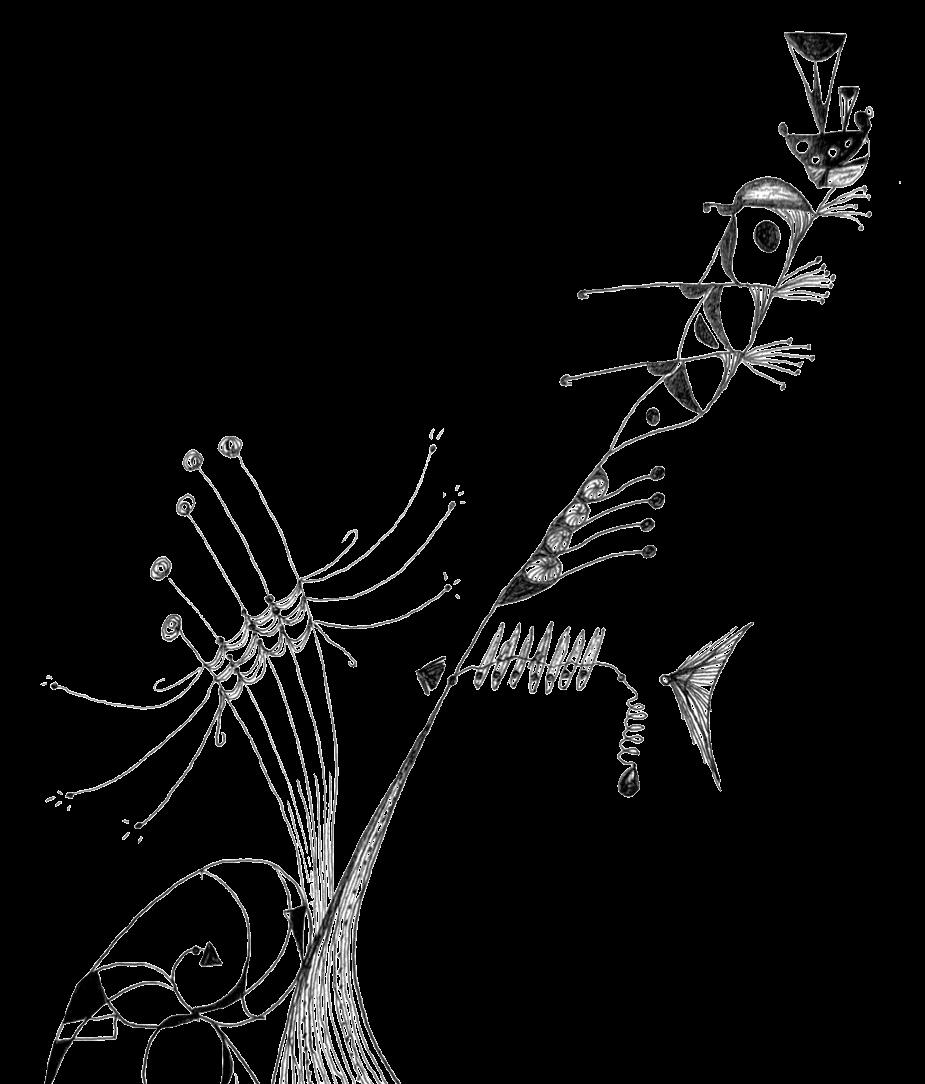

Ouroboros by Lorena Carrilho

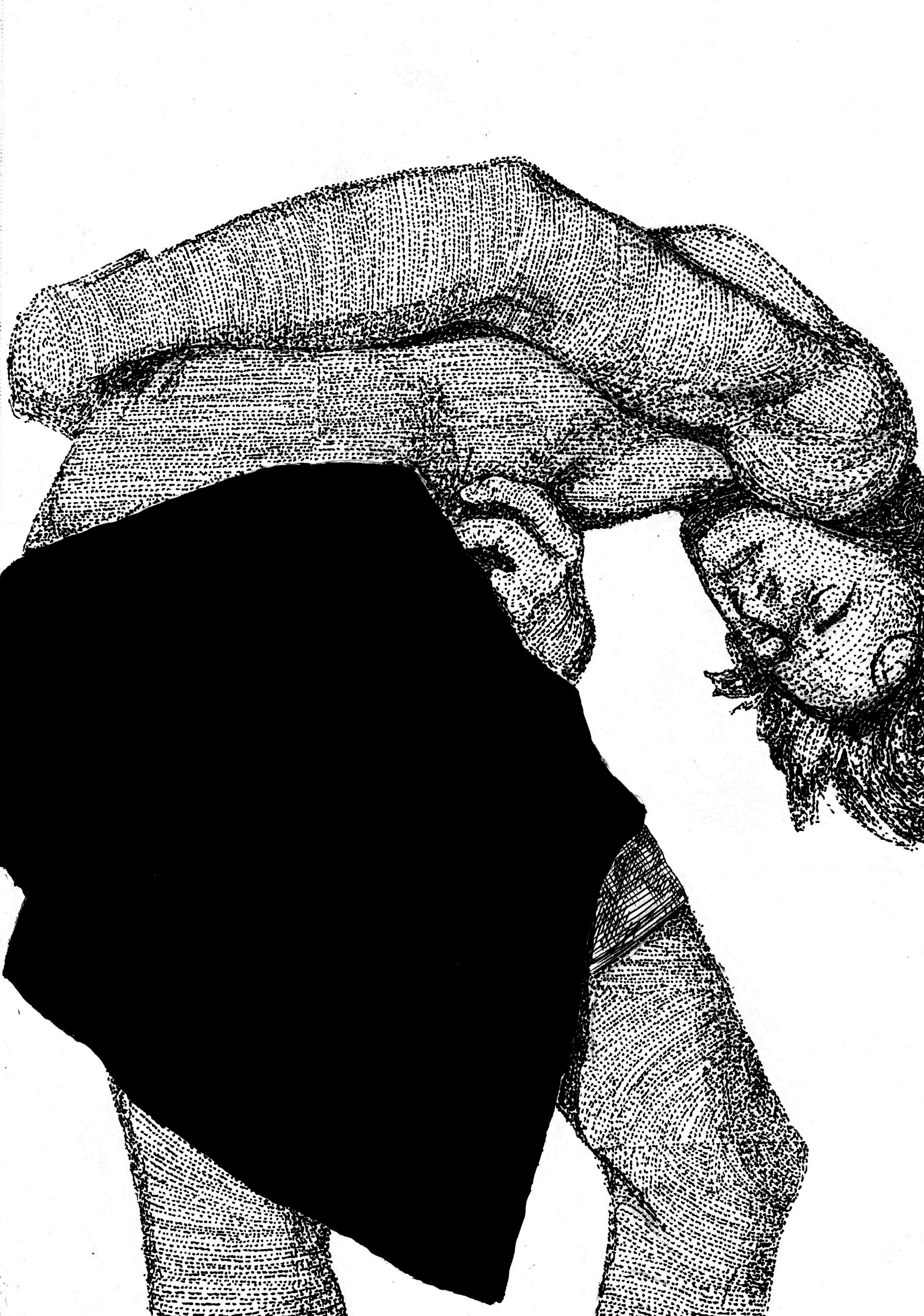

Unrobing

by Isabel Norman

There is some ache in entering this still, dove, gray. Some ache in stepping away from the land and all its fastenings, the clumsy color of a life.

To shed my scarves, my scattered papers and slipped sayings, my quippy rhymes and crushed receipts; No use for it here.

For when I lower myself in this great hush of silver sea I am, this is all:

a speck of salt

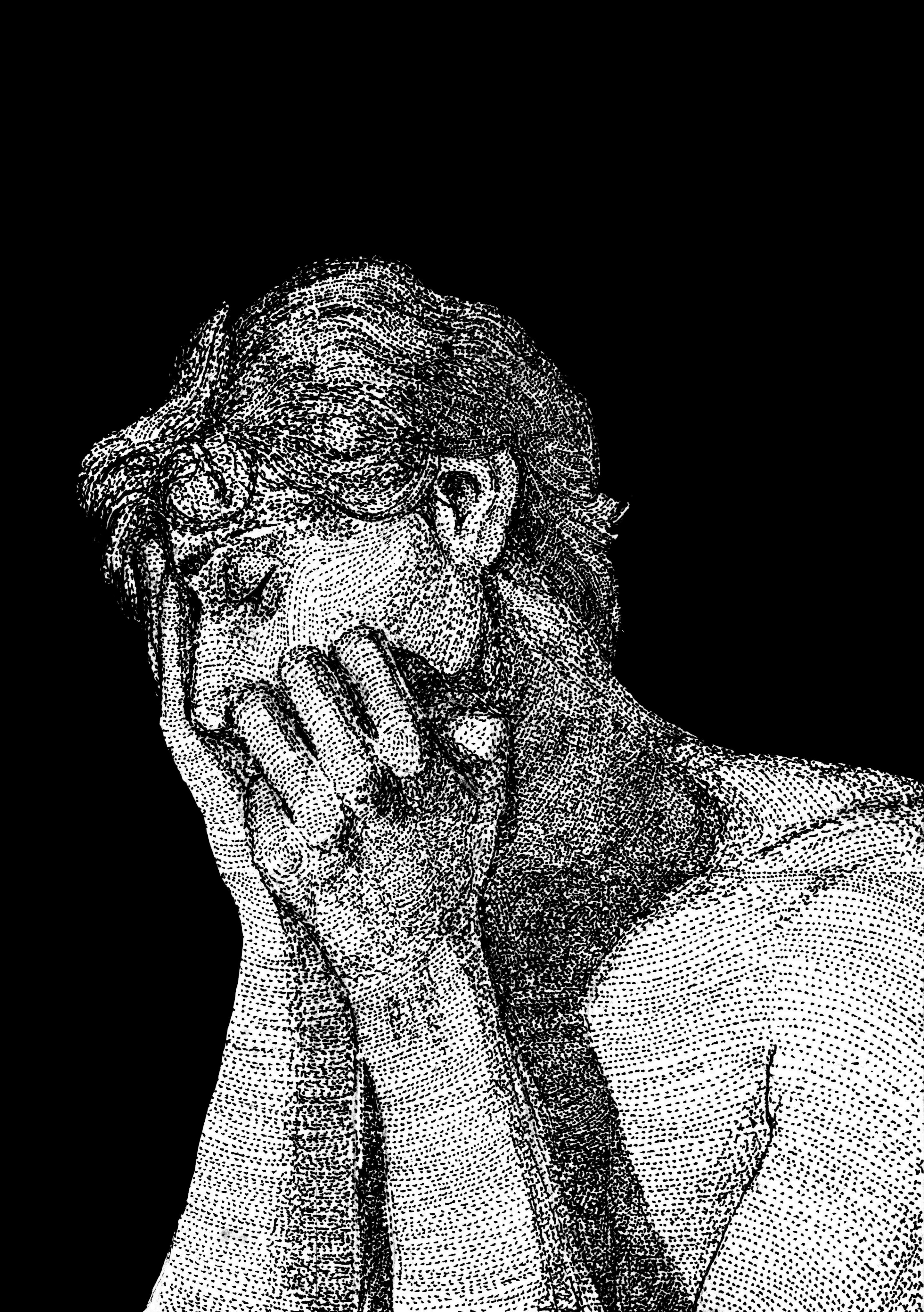

A Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man by Conor Hogan

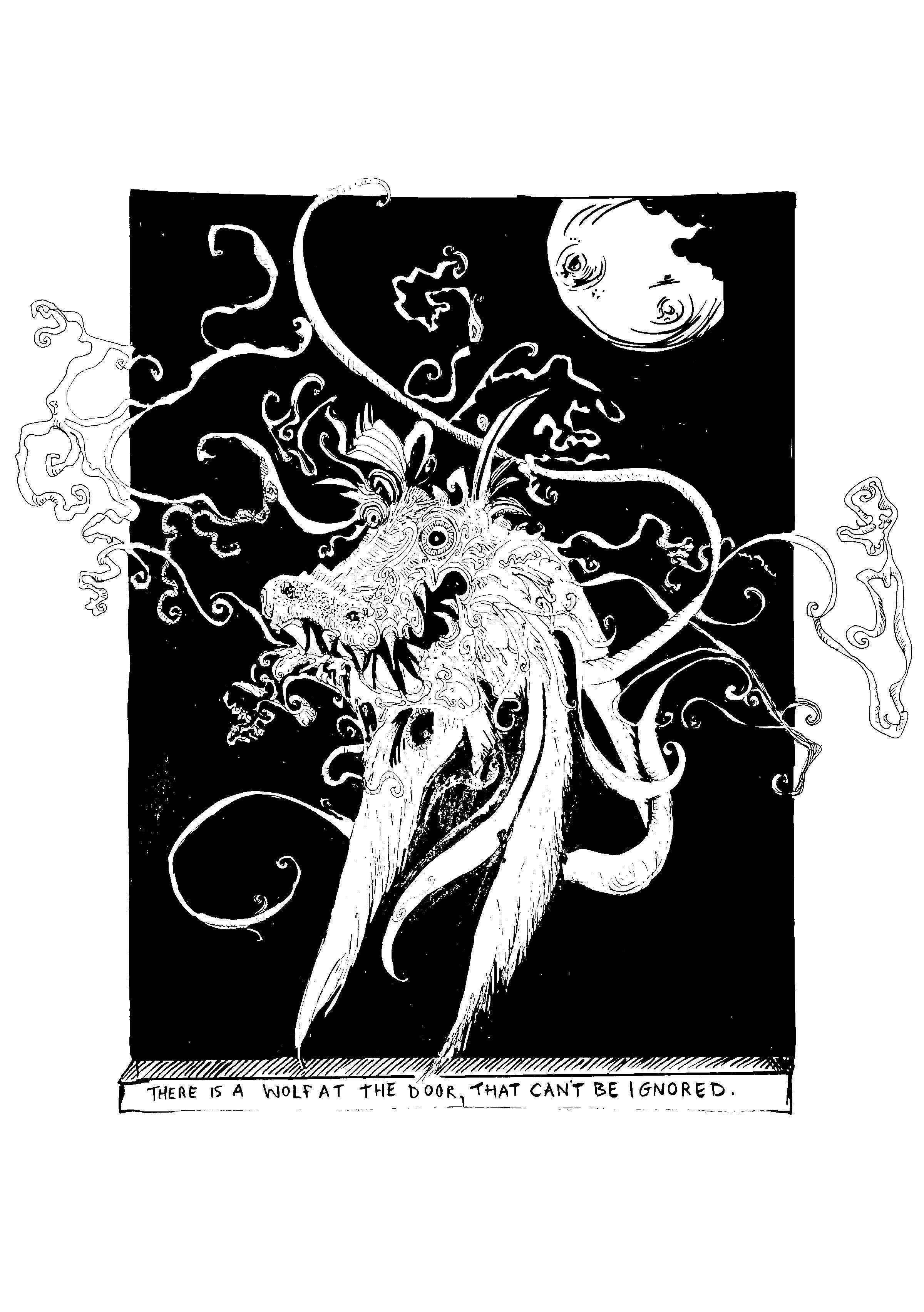

There's a Wolf at your Door that you Choose to Ignore by Jessica

Sharkey

Death of a Motel Acolyte

by Luke Opalack

Swindled by Highway 66 sirens, I found myself at a drive-through Delphi. Madam Marie herself looked twice at my leather beaten hands, And assured me that I’d die in a Peeling and naked one-lightbulb room.

Donning my best rosebud tuxedo, I’m destined to be drowned in Military man morphine and Joshua Tree tequila. Apollo that fuck, He just laughed, put his hand on my shoulder, and said: ‘Son, first round’s on me.’

Waiting for the Alighierien bellhop

In the second circle lobby, I heard Persephone telling Isaac About the sins of the father. Isaac just sighed, and asked if she could use another round, Just to see where this defiled night goes.

‘I’m staying with Mr. Mark,’ he says, ‘Just down the hall in room 7:20.’

I should have been a swarm of seagulls, Soaring across seersucker skies, Silently dancing with Ocean’s blue. Maybe in the next.

In the cups at my ultimate haunt, I peered into the barrel of my swan-song, And saw only the flashing white irises of angels. I heard their Moksha motorbikes, Sticking my thumb out as they came down.

Hoping, hoping, hoping, they’d let me join them, Taking me somewhere, anywhere, that resembled home.

In Sublimation by Elias Doering

They whisper of you to the first years and grin to see small eyes ripple wide, twelve year olds shivering in delighted horror as they picture a black-robed, boxed-in, gimlet-eyed nun striding over billowing waters. At night they shiver when they creep barefoot, in too long nightdresses, to the windows and fancy they see - there! beyond the trees!a figure darker than night; then, according to type, they shriek or run noiselessly to bed, fragile feet pattering along the floor where you walked that night, 1875, the Feast of the Epiphany; cape (black) over nightdress (white), hair (unbound), bare feet treading slow deliberate steps across gouged wooden floorboards, and down. Down from sleeping sisters and abandoned headdresses, towards dead and dipping branches, frozen strands of crisp green grass, and hungry, yearning silence. The waters parted for you, hair swirled, tumbling and loose, the cape slipped from your shoulders, and in the morning, searching, they caught hold of its black folds first. They laid you down by the lake, one of theirs, they would not take that from you even as children whispered in dark corners of the nun who - and the lake whereand they whispered back of the nun who sleepwalked, bare feet gliding across the water’s surface, until awoken - and then the falluntil the children saw her walk (closed eyes, stretching hands) into the impermeable silence of dark waters, and so they whisper anew of the sleepwalking nun, the nun who walked on water, the ghost on the lake, until one day they will forget to whisper at all, for who believes in ghosts nowadays?

Anne Grundy

In Memory of You by

Mary Jane (el) by Genevieve Dineen

After the altar, Love and Disgust bred Lust, a ghoulish creature of rabid appearance. Red and ripe as a licked organ that spurts its arterial whites. Animated, appealing and in love with all disgusting things. Crepuscular; Lust lives in a transitionary space until the amber thread of dawn separates itself from the black. Stalks the jagged city like the spirits of hot wind that whine down the subway, fingering the skirts of faceless women on platforms. Glides the grey rug of the river Clyde past ships passing in the night - those looming ghosts that used to bring in the creels and cakes of salt to the forsaken city. Lust mutters slurred, salty curses in Glaswegian tongue and drinks itself to death on a stream of shivering white wine. Lust has liquid wicked wings. Cherishes the sepulchral sky from lying in the pine-needle ground of the graveyard. Necropolis, sinking under. The only place in Glasgow where Lust hears the leaves fall. A monster hunted down, speared by the iron stakes of those skittish cemetery gates. The oddshaped moon sheds lurid light, shows a stone sunken with moss. Reads the name, the dreadful epitaph of the dearly departed. Here lies Lust, epigone of love, apostle of disgust.

Clockwork Orange

by Jennifer Greene

The

Diffiteor by Saoirse Dunlea

I confess to the almighty void and to you, strangers and strange men, that I am not the same, that I have changed in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done, and in what I have failed to do; it’s my fault, it’s my fault, it’s my most grievous fault; therefore I ask the iconaclast, Mary ever-voyeristic, all the lovers and fuckers, and you, you’re still strangers, to pray for me to the moonless night.

Vespers before bed - always jarring, metabolic, fanatical. Come afternoon light I am embarrassed. There’s few good whispers I can spread in the city still leaden with poison. I’ll only prance after two hours preening, the pretty things litter and gawk, and I won’t be caught without bijouteried clavicle. In the cradle of the canal there is nothing to squawk about and I wish they would be quiet. She waddles me by with a fertilising freedom. Fickle me, soon drawn away by unfettered flaneur walking with fear, his midday shadow speeds ahead of him. Far from at ease and home, he does not find the smoke stifling or claustrophobic. He doesn’t understand. He is only playing city, aping radical. He stops a stranger, says ‘A million cigarettes, wispy snakes crawling skyward towards the frigid Creator, you and I in the shit, in the stokehold, keep this smoke billowing.’ An awful observer, he seeks to leave an imprint on the dirty air, the whole plume astir. He’s humiliated himself too today in tiny concrete rooms, pretending he knows how to pronounce [cynic-dough-shay]*. He’s not long for these cobblestones. Freshly carved arches, institutions artificially perpetuate themselves into oblivion, time irretractable. He understands. Some bell tolls for him but he prefers the patchy girl who seems so sanguine laying down on the grass. Impish, he should say, were he not more educated, no supernatural seduction, all facade, after all she’s just the femme du jour. Sitting beside her, they say the same things, only scraggly patches of weeds to consume. They are lying, weight on each other, everything is soft and red and blotchy and swelling, their long hair tangling and lips only tingling a little - corrupt, he’s uninterested in observation. I flee the flaneur.

I return to her, ever-faithful, ever-feverish to perform bereft. Suited salarymen alight from half lives and look so strangely at me, standing above the feathered coterie floating on the southern canal. Every second in the city is the most exciting of my life, but overrubbed by glass, steel, smoke, they’re numb to the pleasure of death. To brabbling ducks I am a god, but in the underwhelming, eminently knowable, animistic way. Blakes’ uniformed, iridescent heads lurch in troupes tailing unkempt, speckled brown ducks. She wags her tail, a leaf hangs from her beak, and the boys sit in tremors emanating from her, concentric circles on the water's surface. I am confident in her coquetry, I am afraid for her. If she is a tease I am only a priest. Three Hail Mary’s for every mallard tail left high and dry. Five Our Fathers for faithless squawks from strange water specimens. Child, read some Corinthians if you catch yourself on the verge of ardour. Free sexual immortality, six sans eighteen. Follow the May Lord through the curtain of spring. I cannot stare at them unselfconsciously, it’s not possible in the city. I scurry home in the dark, little more than instinct, and I’m still afraid of getting gorged or grasped. Silly.

I confess to my empty room, and to you, lonely watcher, that I am without a soul, which, of course, I’ve always known, but I feel it in now, physically, in my thoughts and in my words, in what I have done, what I have failed to do; through my lack, through my lack, through my most grievous lack; therefore I ask the empty image, Mary ever-diverting, and all the intertwining limbs that have forfeited individuality, and you, I would not go home with you tonight, but think of me, coiled, praying now to the waning crescent moon night.

*synechdoche, pronounced [sin-neck-ducky]

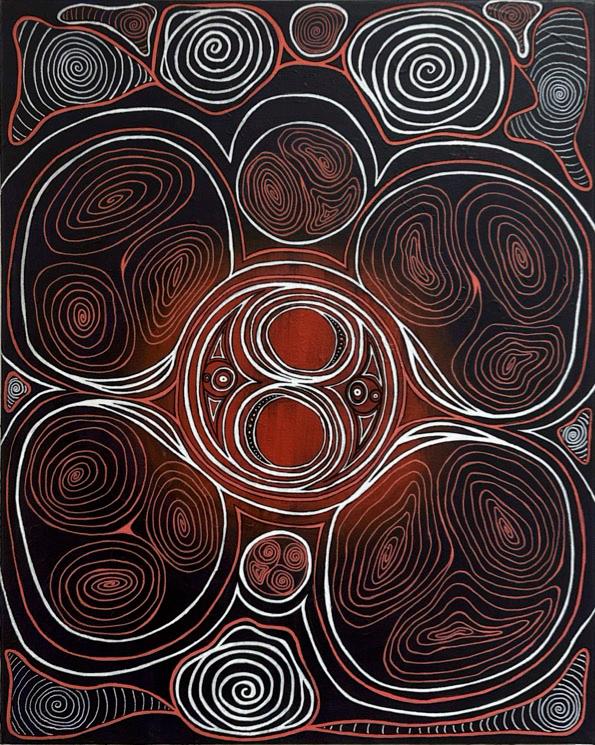

Tara by Saffron Ralph

THREE-HUNDRED-AND-SIXTY-FOUR

by Amy Kennedy

Hanging anemometer,

February fifteenth and I am seriously considering becoming a hijacker, grabbing the bus driver, saying I love him and pushing him out the door so I can turn this metal box back – rattle the other passengers around like coins in my piggy bank. I have four

Spanish euros in my pocket, two tattooshop coffees; burning American traditional into your hand, lover sucked into your collarbone. Frank’s partly because pushes the needle in a circle; trading the false start of springtime for another six weeks of sleep. In a Punxsutawney

cave: handpoke wall painting, bus-fare-box like savings jar, your spiral eyes measuring the wind.

Suffocation by Maggie Kelly

Mackerel Fishing in Kenmare by

I.

Damp brews as dusk is summoning mackerel to feed and boats to prowl. An inky sky glitches with too many queued moons- everything patiently bobbing. Little can be heard but the propeller spurting its concentric threats into the thick parish of fish til the old man cuts the motor, sh-sh-hushing.

II.

Hanging over the hull, the small girl skips her stashed pebbles across the sea’s slicked film but the ripples flare and fail, an incandescent promise. Little streaks of silver blossom from beneath the partition as some siren’s dud brocade.

Still now, the girl’s waxing dreams twitch with the thought of the fish cradled at the keel her father pulling a whetted blade through the upturned envelopes of their starry bellies- exhausting work, and the tin stench of that demented stack

III.

Edging back, cinders flitting from camp, women waiting. On our backs, waves chomp at the last of the horizon everything around us ravenous before collapsing.

Laura O'Grady

by Sophia Allen

Plucked fresh and raw, spinning as surfaced

Bends bubbling beyond blood, goosefooted in warmth

Twanging mind — languid fullness tailbitten by rotting haze

Skin Horse real, spilling seams to be rended and meant

Soft touch through time, holding memory’s fingerprint

Vibrating doubled self, octave below and above — green and curious

Bone-steadied and love-muscled, water-sealed and earth-bound: my small-shelled vessel setting out to seek remembering

Helen of Troy by Masha Lyutova

Verlan by Elias Doering

An Energy Drink Sits.

by Oscar Downes-Banda

An energy drink sits—half on my desk, half in my stomach. Incisors wear marks of erosion; I am newly disturbed by the tongue And its detailed reports of a derelict home, just as soon as I’m free from the call I find my foot bouncing: It’s mumbling something absurd.

Harmony’s not been lost; now that ignorance has taken root And I sit—half a mind to escape, and a snivelling gut

Giving reasons to digest itself like before when I slept

And I rose and I hadn’t the strength to describe it.

Riff by Nina Isles

The Intersection by Cat Grayson

Digressions

by James Grace

When I was nine years old, I discovered a dead body in the park by our house. This is a line I have opened dozens of personal essays with. It has done me well, this line. I even won a regional essay writing competition with it, earning a one hundred euro gift card for Dubray Books and getting posted on my secondary-school’s Instagram page, although I only came third at the damn nationals. Luck of the draw, I guess.

That is not to say that this event never occurred. I remember it quite well. It happened on my ninth birthday, although I usually don’t mention that in the essays. It muddies the water, a bit, and I don’t want to take away from the main focus of the story: the gut punch of finding the man’s body in the park, tangled in the bush, blood speckling the white hydrangeas. It is the blood on the white flowers that really gets the English teachers, I think. They call it symbolism.

That part of it is completely truthful. The body, the blue paleness of the skin, stab wounds peeking out between rips in his shirt. What is less true are the words like ‘deep sense of tragedy’ and ‘fatalistic air’ and ‘loss of innocence’ that I pepper throughout the text. These are the words that English teachers and professors tend to put lines under and write ‘excellent’ or ‘superb’ beside, like they are giving me a cookie for adequately expressing an aversion to dead bodies.

These words are not lies in the strict sense. I like to call them creative truths. I don’t really remember exactly how I felt at that age when I happened upon the body of Mr. Hogan, a local real estate agent. There is every possibility that I had deep thoughts about mankind returning to dust, and soliloquized in iambic pentameter about mortality. But it is unlikely. I do remember feeling a sense of shock and dread. These were not thoughts. They were almost physical reactions, probably the same that anyone would have upon finding a tangle of limbs and thorns and the horrible twist to his lifeless white face.

I felt as though the beat of my heart stopped, or receded into a deeper, more quiet part of myself. Goosebumps hardened the skin of my arms and legs. I stood still, trembling slightly on the spot, as I gazed terrified into the bush at the dark corner of the park, the overhanging trees casting brooding patches of shadow on that sunny day. This is all also true. I remember it verbatim because I have written it for every personal reflection since I was fourteen.

This used to be the bulk of the essay. Finding poor Mr. Hogan (who helped my parents buy their first house), then describing the immediate shock of the discovery, running back home with tears in my eyes to my mother, who could not understand a word that I mumbled hysterically through the cotton of her dress. My arms were clung tightly around her. This was the year after my father died, so tears were not an extraordinary occurrence in the house. I assume that is why Mom thought I was crying, because this was the first year that Dad would not be there for my birthday. We had had an argument the day before, when Mom had offered to drive me to the beach for a swim. This had been a tradition with Dad every year the day before my birthday. We would get in the freezing October water for as long as we could before wrapping ourselves in towels and drinking hot chocolate from our flask. We always had a competition to see who could last longest in the water (which I miraculously won year-on-year).

I think I probably saw Mom’s offer to bring me to the beach as a kind of erasure. Like we were pretending that Dad never existed. Although I hardly thought about it in such sophisticated terms at the time. At eight years and three-hundred-and-fifty-five days old, I was too young to realize that going to the beach and having a fun time with my mother would probably have been as good for her as it would have been for me.

I tried to include something resembling this in one of my earlier essays. I got marked down for making too many digressions. Focus on the main event, my teacher had said, with red biro through the paragraphs he didn’t like. He had left an all caps REFLECTION? underneath my last line. This is what led to the high-minded musing on the nature of mortality that later made the piece such a hit.

I also excluded all details about how the rest of my birthday was spent. This was another digression. I was in such shock that my friends were called off. Only close relatives arrived, although for most of the evening I was sequestered in the living room, by the fire, eating chocolate-biscuit cake like a Victorian child. My mother stood behind me with her hand on my shoulder, while a rather out-ofhis-depth looking garda asked me questions. (I did not mention to him anything about ‘fatalistic air’ or ‘tragic ironies of life’). He was young and lank, and seemed dazed by the bizarre nature of questioning a boy in a paper birthday hat about a possible murder. My aunt offered him a slice of cake. When he left he wished me a happy birthday.

Mom kissed the back of my head and gave me a big squeeze around my chest while congratulating me for being so brave (this was the first hug I had allowed the poor woman since my father’s funeral). I looked up at her to see that her oval face was teary and red beside the light of the fire. She said she was sorry that I had to see what I saw in park, and the day was ruined, but tomorrow we would go for a drive somewhere special, okay?

We wound up going to the beach. My resolve had been softened by the events of the day before. I have been to that beach several times in the years since. There is something comforting in the sands there when the place is not too crowded. On the way there, Mom seemed excited in the driver’s seat. I think that she felt privileged that I had decided to let her into this sacred tradition. Before we got there, however, rain started drizzling in spurts from the grey sky, and by the time we were in the carpark of the beach, it was like heaven was pouring down upon us. The sand was flooded and dark. We looked at each other and laughed. Maybe another time, Mom said, and we drove on home, although I sensed a deep disappointment lying in the thinness of her voice.

None of that stuff made it in to the essays. Not that it should have, either. You can’t spend too much time on irrelevant family history when you have only fifty minutes to work with. Not if you want a H1 anyway. But I would be lying if I said that I had any authentic deep musings on the nature of Mr. Hogan's death, even though it is probably one of the most significant things that has happened in my life. Sometimes it comes up at the firm I work at, oh, you’re the lad that found the body from that case a few years ago, crazy. I even get a pat on the back, and a wow sometimes. It is my greatest achievement, wandering into that dark corner of the park when I was nine. In one-hundred years’ time, the only record of my existence may be a footnote in a bizarre unsolved murder case. But in my mind it is an isolated event, of no significance, divorced from anything to do with the rest of my life. It is one of my cardinal flaws. I have never been able to attain a sense of meaning in these seemingly major things.

Here is an example. Last year, as I sat by my mother’s bed in the hospice, I barely thought about my father at all. And Mr. Hogan never once crossed my mind. I saw no connecting tissue across the three deaths that I had witnessed. I still don’t see any today. I wanted there to be one unifying theme, something I could take from my experiences to form a sense of self. I wanted to be Hamlet at the graveyard with Yorick’s skull in his hand. But my emotions overcrowded the workings of my mind. I had been in a daze since her diagnosis.

One day, Mom whispered something from beyond the cloud of sleep the drugs had induced. I could not hear the words but I went to her side. For whatever reason, I thought she was talking about Dad. I leaned in close with my ear, saying what’s that Mom? She struggled to make any sound. I felt as though a wave of importance was going to crash down on top of me. I put my hand on her arm. She was frail under her hospital gown. What did you say, Mom? Are you all right? For the first time in days I saw recognition in her eyes. Her cracked lips moved, trying to form the words that laid soundless in her mind, and when she could find the air to give them form, she uttered a fragmented sentence of random words, half-remembered phrases, signifying nothing.

If I were to rewrite my personal essay today, here is how it would go:

When I was nine, I discovered the lifeless body of Mr. John Hogan in a bush at the corner of the park. I was shocked for the rest of the day, and was still horrified for the first few weeks after until the shock wore off and I managed to stop thinking about it.

Vita Lenta by Giulia Vittore

It is the type of sticky afternoon where infrastructure falters and pheromones run loose. The lines have expanded; we are running at half speed. No seats. The usual scents of manspreading and cheap musk pool beside my self-conscious cleavage the desperation to be lesser, to slide between rows of books and hide. Futile is female rage boarding the 5.05 to Weymouth.

I am met with a monolith as I progress to carriage five. Paternal omniscience in horned glasses booms out “No seats, I wouldn’t bother” His breath is sweet, a pip lies in stasis between his two front teeth; I could pick it out.

I have been sold a lie. Our bodies fuse, for a moment before the flustered unpeel. I am a reptile, dislocating and rearranging, blurting out sorries against the sudden hard of neatly ironed linen trousers, the type you’d find in Whitechapel, or Wimbledon on a respectably sunny Sunday, cupping a bowl of strawberries and cream while his children grin gappily back at him like a brood of baby birds awaiting a mouthful.

Strawberries and Cream by Rebecca Gutteridge

Tell me, is it strange, that I can picture his offspring but not his face? Only creamy fruit crammed into hungry mouths before the pour of excited chatter onto Centre Court.

Wings that Desire

by Rachel Hughes

A Woman with Pillows by Masha Lyutova

Pas

De Deux by Harry

My mother thinks religion keeps a lot of people from killing themselves. My sister hung herself, my sister was an atheist. It’s warm for September.

Our rubbish is overflowing with boxes and it won’t get picked up until Tuesday. The window is open as she liked it and when I breathe in deep, I get whiffs of heat and trash that remind me I now live in the city. I’m too old to live with my mother. I took time off/loosely quit/got fired from my bartending job for sleeping with the health inspector on the bar top. So I keep the window open and decide the garbage and heat is good consequence.

I tell my mother I am thinking of going back to college, that this time I could figure it out. She glances up through her glasses and doesn’t have to speak. My mother calls me the smartest boy in the world when we both know I’m wrong.

She suggests we go to the ballet together, instead, mostly so we do not have to think of things to say. She’s smart that way. We sit in Row E, me on her left side.

We take turns passing the program between us, look who is playing Titania, she is beautiful, don’t you think?

I think of what my sister would say to my mother at this ballet if she did not hang herself. She took ballet when she was little. My sister. She hated the tights but she didn’t mind. She had it after school, Monday afternoons. Four o’clock, maybe, but I am guessing at time. I do not remember her being good at ballet, but she was tall, and thin, as ballerinas are supposed to be. The teacher said she had a certain grace that one could only attribute to a fast metabolism. My mother tells me before the show that when she quit, her ballet teacher called and begged my mother to force her to keep dancing.

She could be something great.

The curtains rise on the stage and all I do is weep. The ballerinas look like swans. I want to hold the mutilated feet behind their pink slippers. I curl my toes inside my shoes until I can’t take it and hold it for a moment more to prove the pain. I picture my skin peeling off, it’s gorgeous, fresh and raw and red underneath, my toes becoming less and less intact. The ballerina onstage stumbles and my toes unravel and her face drops so quickly you’d miss it if you weren’t looking. Everyone is looking. My sister’s performance was just brilliant, she only let it drop at the rope.

The ballerina onstage spins and spins and spins and spins and spins and I will be a good son and I will be a good son and I will be a good son. She bows. I ache to bite into her applause. I am starving. Baptise me in it. My mother asks me why I am crying and I tell her it’s all so beautiful.

Mimesis by Verdiana Karol Di Maria

Dart Train from the water. by

Mwan

Silver fish take the Form of light quicker Than me over a Surface — tension

Broken only by the Punctuation marks of Lifted limbs — of a tree

Long ago hewn, laid Down, and on them a Heavier load than I Could bear — it, the Tepid water, the movement Of the soul, trapped (again)

In a poolside moment — Captured in the mind’s eye

Under shifting light — now Dark; clouds and sun beyond And above, the rumble Of the long green caterpillars

Whose destination I share Inside here: water, primordial, All at once mine, but somehow, Still so unfamiliar.

I Saw a Woman Dancing in the Street Today

by Loretta Farrell

And oh was she moving, bedecked, redscarved

down O’Connell, across the bridge flailing arms strewn every which way commanding brilliant AM sunlight,

diffracting somehow she was four places at once, up/down down/up and spinning through cars busses bicycles in between the suits at every intersection a yarnbright blur, arabesquen bluesky splendor her head high high higher, she, balustrade Balanchine, Icarian ballerina in concrete gyre, untethered & endless.

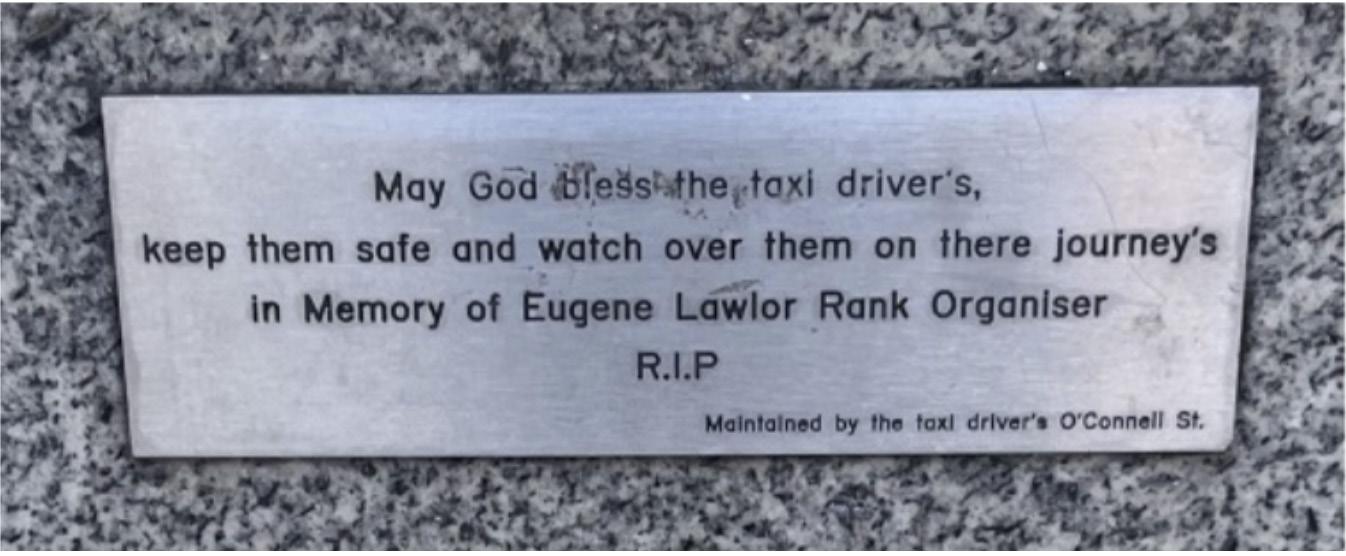

Sacred Heart Statue on Cathal Brugha St. by

Gavin Jennings

Dear God,

At least, let them negotiate tracks

off Cathal Brugha St.

Let the car confluence with tram as beads of rain on windows bleed together on their way down the curved glass face.

See it all as they seeCathal Brugha bled

On Thomas Ln. Off Thomas St. near where Robert Emmet went to Dirty Ln. to Robert Emmet Walk.

Off Thomas Ln. On Thomas St. The Abbey of St. Thomas the Martyr. Thomas Becket of Canterbury -

God, let taxi drivers tell their tales, as Chaucer’s walkers, no matter the audience.

Let them bring each fare to a site of holy murder, or sette soper.

If you can make them know their safety comes from things like you and not from chance and other gods then, there’ll be another rise and another night for them to ferry the city’s dead around.

The Dust of This Land Which Kills Poisonous Reptiles by

Ryan McLean Davis

(In response to Gerald of Wales and the colonial text: The History and Topography of Ireland.)

An abandoned home in or around Blanchfieldsland; the crows which croak like frogs; how Hollywood is a green pasture of cows; how Hollywood is still a white sign on a hill; the dense forests of spruce trees in Glendalough; Farmer Richie who says he is governed only by the seasons, climate, and mountains; Richie who, after the workday, throws a fleece on over his shoulders and joins the flock in the pasture; the dog that was bred to run quick across the land; the breed that is the Border Collie; two swans in the river, remembered by their path left in the water and their glorious, stark whiteness against the green; the grey sky with the same stark light shining through; the Heavens casting itself onto this life; the robin which is a ghost of a loved one; in the cemetery, the robin is perched upon the Celtic cross.

Doireann Ní Ghríofa

You want to leave, then leave.

Footsteps grow green and steep

through dew, a path worn by all those who’ve gone before you. Maybe I like my strife purple, loose, my glass all shards, grass-strewn. Purple, too, the gloves

strung by foxes on tall green hooks,

Belladonna’s knotted roots might still the milk, but milk still seeps through, and such ink or inklings always spell doom.

Oh Ariel, what became of you? Skull under floorboards,

hooves gone to glue, sands swept clean of serpentine loops.

Her horses all galloped loose and now you, you want to leave too?

Then do. No one will believe you.

Spells Doom

by Doireann Ní Ghríofa (First published in

The Stinging Fly)

Josie Giles

from Once

by Josie Giles

Lies

Once there was a woman whose every word was a lie. She clung to untruth like a limpet to a skerry, and all the tides washed past her. If she said “Fine day” you could be sure that it was raining, and if she said “Very well” you could be certain that something was amiss. Her lies had no malice to them. It was only that she saw the world as other than it was. So long as you knew that she would keep no promise, she could be a very fine friend, for the lies were only in her mouth. If, when you were suffering, she would have the wickedness to say, “It will be alright”, your hand would still lie in hers. And if, having lent you money in a time of need, she would say, “You’re welcome”, the money would still lie in your purse.

She fell in love, as many do, and though it was not possible for her to marry, for fear that her lover would hear her say “I do”, the pair lived together happily enough without such words. When the children were born, the liar would tell them long, impossible stories deep into the night, and if those stories ended with evil vanquished and good rewarded, the children would already be asleep and in dreams of their own. And if she never once said “I love you”, her family would also know not to believe the sharper words she spoke.

At only two score years the strength left her limbs. It was a growth in her belly, the doctor said, and nothing to be done. “It’ll work itself out,” said the liar, and so her beloved called the children home.

It was night and the pain was scored on her face. All her family and friends were gathered. She asked for a little water to wet her lips and looked around at the worried faces.

“Better companions no-one could hope for,” she said. “I deserved no richer life than this.” And then she died without another word.

Work

Once there was a sculptor who could not stop working. As soon as there was light to see by, she would walk to her workshop and take her chisel in hand, and in her hand her tools would stay until light left the day once more. She prepared her morning porridge and her evening stew with the same efficiency with which she extracted faces from marble, and when she lay on her thin mattress it never took longer than eight minutes of counting before she entered seven dreamless hours of sleep. Though her work was neither the most beautiful nor the most inspiring in that country, she was the quickest and most reliable of all the sculptors, and so her straightforward likenesses of queens rose in city squares and her ordinary monsters lined the drainpipes. She worked through the holy days, she had no appetite for travel, and were her mother or sister to ask, not a little nervously, whether she would consider resting, she would say, “I’ll rest when I’m dead.”

It is not that the sculptor was without feeling or pleasure. One day, walking home from her workshop, she saw a beautiful young woman carrying a basket of roses and was struck through the heart with love. The sculptor courted with the same single-minded focus with which she carved and ate and slept. She learned the flower-seller’s routes through the city and contrived to meet her once each day; she learned the flower-seller’s pleasures and made gifts of them – chocolates and sunsets and a firm grip on her arm just shy of causing pain; she learned how the flower-seller wanted to be kissed and made a study of the soft curve of her lips. After three months they were engaged; six months later they were married; and nine months after that the sculptor held the first of her children in her arms. She made such adjustments to her schedule as were necessary to ensure that her wife and her children received care and attention; she did not leave for her workshop until her share of the morning chores was completed, nor sleep until the children were tucked safe in their beds; and if seven hours of sleep were to become six, and if she had to work all the harder while the chisel was in her hand, so be it. And were her wife to ask, not for any lack of love or want of time, but only from fear for her lover’s heart, whether the sculptor would ever rest, she would say, “I’ll rest when I’m dead.”

There were troubles in that country as there are in all countries, and the guild of sculptors struggled as all struggle. The nobles, though the wealth of their palaces only seemed to increase, conspired to drive down rates, and the quarries, though the holes in the mountains only seemed to grow larger, conspired to raise prices. The sculptor was not one to shirk her responsibilities. She served as secretary of the guild’s council, and then treasurer, and then first chair. She attended court with speeches built of granite logic, and her will when confronting city commissioners was unshakeable. She increased her family’s budget for candles, and once her children were asleep and her wife had been kissed, she would sit up late preparing her papers. If six hours of sleep were to become five, and if she must work all the harder while the chisel was in her hand, so be it. Were her colleagues to ask, after a long and fruitless meeting with the guild of quarrywomen, whether the sculptor would ever rest, she would say, “I’ll rest when I’m dead.”

She was neither strangely old nor strangely young when she did die. Her wife woke and saw the sun streaming through the windows and marvelled that for the first time in their lives together the sculptor had slept past sunrise. Then she understood what that meant, and with tears on her cheeks she reached for her beloved’s strong hands. They were cold as stone. It was as if the sculptor’s heart had reached the appropriate age and decided that this was the most practical time to stop. The flower-seller went to the desk drawer from which she took a neat bundle of papers, and she followed the instructions there with all the love that still filled her chest. The burial took place in four days, and their three grown children were there, along with all the members of the guild council, the first chair of the quarrywomen, and even a pair of nobles. The workshop was passed to the sculptor’s hardest-working apprentice, as all expected. The sculptor’s chest of savings, into which she had placed exactly two coins each week for the last thirty years, would keep the flower-seller well until her own death, ensuring that she herself never need work again.

The next morning, rather early, the flower-seller woke. Something was moving in her room. She could not make it out in the half-light, but she followed it down the stairs to the kitchen. The shape moved between the stove and the grain-bin and the table. She followed it into the streets, wrapping her shawl around her arms against the cold and keeping a few paces behind. She followed it into the workshop, where the shape, clearer now, but insubstantial, like a swirl of marble-dust in the light from the high windows, or like a few scraps of paper tossing in the wind, or like nothing so transparent or so heavy as love, moved back and forth, back and forth, between the tool-bench and the block of stone, never stopping, and never able to grasp what it sought.

A Joke

Once a child was born laughing. From her first breath she found the world absurd. When the cord was cut she gave, instead of a wail, a peal of bubbling joy that echoed across the green island. When her mother held her to her breast, the child struggled to feed, for so strange was the feel of skin that she could not help but laugh.

The child grew older and life grew ever more ridiculous. The neighbours remarked on her happiness and her sweet nature, but there was an edge to their words: when the child laughed, they nursed the fear that she was laughing at them. “No!” said the child, as the laughter shook her body and her armfuls of grain once again spilled on the ground. “It’s only that it’s all so funny!” But no-one could make out the words between her gasping breaths.

One way or another, although her mother despaired of her daughter ever being able to wash the windows without breaking them or dust the shelves without sending every book tumbling to the floor, the child grew up to become a happy, laughing woman. Her neighbours no longer smiled indulgently or forgave her faults, because now she was an adult and should know better than to laugh at every little thing – but weren’t their angry stares as hilarious as everything else?

Then, one fine spring day, the lady of the island came to visit her people and see that all was in order. All the neighbours warned the laughing woman to stay inside, but the sun was warm and teasing on her skin, and the eager birds laughed with her in the trees. She was sitting by the well and laughing to herself when the lady and her retinue came to shore and made their way up the pier. So fine were the lady’s clothes – with more wealth in the fabric than in all the houses of the village combined – and so proud was the lady’s expression that, try as she might, the laughing woman could not stop a snigger escaping her lips.

The lady stopped and her guards stared. The birds fell silent in the trees. “What,” said the chief of the guards, “are you laughing at?” The laughing woman could not speak. The guard’s voice was as heavy as the grave, but the situation was entirely ridiculous. Her snigger turned to a laugh. “Explain yourself!” shouted the guard. “Your lady demands your respect!” This was, of course, even funnier, and so the laugh turned into great guffaw. “You have one last chance,” said the guard, “to cease your laughter and bow to your betters.” The laughing woman fell to her knees and tried to lower her head in respect, but howls of laughter bucked her body back and forth. The guards put her in irons, her shoulders shaking all the while.

The stone walls of the grainstore where they kept her could not contain her laughter, which echoed through the night from pier to woods, from hilltop to lochan. And in the morning, when she was led to the newly-built stage in the centre of town, her laughter was still as high as the bright, hot sun. In the dry dust before the houses, her neighbours were silent: not a word, not a smile, not a tear. The executioner feared, with the laughing woman’s body rocking on the block, that she would not be able to land the axe as cleanly as anyone deserved. But in the end it only took one stroke, and when the laughing woman’s head fell to the ground her mouth was wide open and her eyes were filled with laughter.

from ceud beinn / a hunner o hills / a hundred mountains by Josie Giles

beinn ùdlamain am bithinn nam mhùgan agus sibhse fo bhròn buan bho chleamhnas nam pleitean is tearbadh nam beanntan?

drum hill

whit wey wad wae be mines whan thoo’re kent wanjoy fae the first loveseek pairtin o pangea?

dour mountain

how can I lay claim to sadness when you have been in your sorrows since one continental plate learned to love another?

sgàirneach mhòr

dà rud a’ ranail an abhainn

’s an a-naoi

muckle skirlan

big screeing

two roars the river and the road

twa bulders the big rodd an the burn

alltan san toll mathan san uamh strinnle i’ the pot dug i’ the kennel streamlet in the sinkhole cat in the cage sgùrr nan conbhairean the kip o kennellers the peak of kennelmen

shirin kip

sgùrr na banachdaich

a’m taen me shaem ap the brae an syne a’m taen me shaem

doun the brae but syne me shaem wis seen the scores o the warld

purification peak

i carried my shame up the mountain and then i carried my shame down the mountain but then my shame had seen the scars of the world

bheir mi mo nàire

suas a’ bheinn is an uair sin bheir mi mo nàire

sìos a’ bheinn ach an uair sin bha mo nàire air eàrran an t-saoghail fhaicinn

ciste dhubh

uismal kist

gleann a’ leigeil anail meuran a’ guidhe mhiotagan beinn a’ falach a h-aghaidh agus òr òr òr

dayfelly i’ the vailey dinlin in me fingers cranreuch i’ the corrie grim-day layan gowd

black coffin

white valley red fingers

black mountain gold morning

Chen Chen

A Less Pure Poetry by

I shouldn’t have told you I was having a tough time writing about your nonstop giggling from the other night. I shouldn’t have said, It’s already what people call “pure poetry,” your pure giggling the other night.

Because then you said, I know, it must be hard, going from that to a less pure poetry. Because well, I knew I’d have to write about this moment, too, in all my lesser ways, & the better bits would come from you, but actually I want it like this, I want to tell the world that the best phrase came from you, see, I made it the title, so you can shut up now with your nonstop complaints that I don’t give you enough credit,

except don’t shut up ever, & could you laugh like that again, like you’re some new slang for forever, & I could try to keep up.

everything ends, please bring all the ingredients for meatballs, italian or swedish, & a spatula your hugest or actually bitsyest.

join me! by this weird old willow tree.

Chen Chen

just in case by Chen Chen

we are going to feed the planet’s most powerful force of whimsy, which today has taken the form of these two tiny, masked pro wrestlers who are so busy climbing or more like crawling up this old willow tree. they are like two very muscular caterpillars. yes,

from your littlest spatula let’s feed them not meatballs but the handsomely chopped, diced, & minced ingredients for meatballs.

just in case the world ends tomorrow or nowish, please focus.

it is so easy to lose oneself to oneself & think, ah, that’s whimsy.

when no, not at all. whimsy is finding the world & sharing it—

see how one wrestler’s mask is bright, bright red & the other’s is deep, deep blue—

oh, did you remember to bring a ladder, too?

college nights spent begging & begging my japanese major of a white boyfriend to also learn mandarin, as though learning it would be the same as loving me.

good riddance, his reply that went, oh eventually i’m going to know every east asian language, i’m just starting with japanese.

adieu, not sticking with français when maybe i should’ve. when “reconnecting with my heritage” meant taking mandarin ii (am i ever not taking mandarin ii) & meeting ever more fetishists, only now they begged me for help with their accents.

sayonara, white boys in love with saying ni hao & oppa & sayonara.

toodle-oo, thinking i’ll be the one studying you, this time. toodles, every time i thought i could turn a noodle-fevered boba fiend into at least a friend. so long, longing & waiting to be more than pictogram, pretty picture. ciao & cheerio, believing

i’m charmingly healed, completely swimmingly swell. ta-ta, believing i can simply love my own damn face without continuing to learn precisely how.

bye bye, belief i’m anywhere near done bidding my college & post-college aches, mistakes farewell.

see you later, my own damn beautiful face.

goodbye by Chen Chen

CONTRIBUTORS

SOPHIA ALLEN is permanently traumatized from that one rat launching out of the toilet at her when she flushed.

VERDIANA KAROL DI MARIA is still wondering whether she is searching for poetry in life or trying to capture the poetry of life. She is eternally undecided.

OSCAR DOWNES-BANDA always salutes the magpies, but isn't always happy to.

SAOIRSE DUNLEA is a writer, a learner driver, a lapsed Catholic, a painter who only uses blue, a potential drop-out, and decidedly not a poet.

LORETTA FARRELL has got a lot of things to do, a lot of places to go, and hopefully a lot of good things coming her way.

JAMES GRACE is trying to appear cool and nonchalant about his inclusion in this volume. He is failing.

CAT GRAYSON believes life isn’t linear—it loops, curls, and occasionally tangles. She’s fine with being lost in the pattern.

JENNIFER GREENE is happy that you are reading her name right now.

ANNE GRUNDY has been lured from Monaghan by the promise of lots to read. So far she has not been disappointed.

REBECCA GUTTERIDGE is a writer and maker from Dorset UK, graduating an Mphil in Irish Writing at Trinity in 2023. Rebecca’s work often concerns identity, angry women and the impact of ill health on the female experience. The natural world and the joy of craft is often the antidote to it all - from domestic ennui to vampires on the far-right. She has been published in several Irish publications such as The Belfield Literary Review, Extended Wings & TN2.

MAJA HAMIDOVIC loves photographing people when they are unguarded and not posing.

HARRY is a contributing writer to Icarus.

CONTRIBUTORS

CLAIRE HENNESSY is writing her third person bio on public transport while pondering what Sartre had to say about Other People.

ISABEL HERNANDEZ-KEARNS struggles to call herself a photographer.

CONOR HOGAN draws stuff. Sometimes it resembles art.

RACHEL HUGHES knows that she knows nothing – and therefore has no idea how she ended up here.

NINA ISLES isn't convinced.

GAVIN JENNINGS is running to the shops, if you want anything?

RANYA KAUSHIK thinks that curating Spotify playlists is nothing short of a spiritual practice.

MAGGIE KELLY is a final year psych student—in her spare time you'll catch her running marathons, painting canvases or conducting neuroscience experiments! A jack of all trades, but a master in none... followed by a severe lack of personality and constant mid-life crises.

AMY KENNEDY grew up by the sea in Co. Wicklow. She is Junior Sophister studying English, and when she isn’t reading or writing she makes coffee for dancers, circus people, and other Trinity Students at Mind the Step.

FLORA LEASK-ARIZPE is coming out of her cage, and has been doing just fine.

JULIAN LOVELACE lives in Dublin. They're attracted to strange visions.

MASHA LYUTOVA went into STEM because she had no idea how to afford art supplies on art wages.

LOUIS MALAURIE WAN is studying engineering only to be able to afford his passions.

LORENA MARTINS is glad to live in a world where there are Octobers.

CONTRIBUTORS

ALANNAH MCELLIGOTT RYAN is the thing with feathers.

RYAN MCLEAN DAVIS is running late to the function; she is petting the cat on the street.

DARRAGH MURRAY is alive and well.

MWAN is a glass-half-full kind of gal. She can be found enjoying her life and trying to make sense of it through drawings and poems every now and again.

ISABEL NORMAN gives her deepest apologies for running late, again! She had to wait for her coffee to brew.

LAURA O'GRADY could have written a really great bio if only a kitten weren't attacking her keyboarddgjk

LUKE OPALACK is bedridden with storyline fever. Please turn the volume up.

SAFFRON RALPH is a part-time barista, a part-time florist, and a full-time English student.

JESSICA SHARKEY is an Irish artist and illustrator, international curator and art historian, currently researching and working on her PhD in the history of Irish art in the early 20th century at Trinity College Dublin.

ÍDE SIMPSON is a writer and actor from Belfast, and a proud graduate of the Lir’s MFA in Playwriting. She’d rather be too much than nothing at all. She’d like to thank Maria McManus for her insight and love. She is forever the writer Íde aspires to be.

GIULIA VITTORE is a fourth year student of Film and English from Italy. She loves taking photos of light filtering through lace curtains, hands, elderly people and chairs!

ALICE WEATHERLEY was born at sunset on a Sunday. Her favourite fish is the masked hamlet.

BENNY ZAPRUDER might have filmed the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Seems unlikely though.

FEATURED WRITERS

CHEN CHEN has written many poems, probably too many. He is always sort of exhausted. He would like to lie down now and quietly discuss his childhood crush on Tuxedo Mask, a very important character from the Sailor Moon franchise. Thanks.

JOSIE GILES has lived in six islands and hopes to live in more.

DOIREANN NÍ GHRÍOFA writes poems and strange books that hopscotch between genres and times. Her days are spent either in archives, trying to eavesdrop on the Dead, or writing in her car, where she attempts to turn each empty page into a trapdoor to the past.

FEATURED ARTISTS

ELIAS DOERING is a visual artist sometimes operating out of Montreal, Quebec. They are currently stranded on a desert island and their last pen is running out of Elias created this issue's front and back cover and other artwork interspersed throughout.

GENEVIEVE DINEEN is like really really really really ridiculously good looking.

Genevieve created the accompanying artwork for the featured writers and editors.

EDITORS

GWENHWYFAR FERCH RHYS is the subject of a prophecy far older than this land, or any other. Though lately she has begun to wonder whether she mightn’t have all along been amongst the cavernful of prophetesses dreaming this narrative into being: ther dormant mumblings the words of the story, ther drowsy tossing its twists and turns. Stay tuned for her findings @gwen.fr_writes.

GRANT is just getting the hang of things.

EILEEN

La Lune Kept Still by Ranya Kaushik