ISSUE 24: JANUARY 2026

AI in housing: ‘It’s here and all around us’

HQM investigates: The rise of for-profit providers

Housing predictions for 2026

AI in housing: ‘It’s here and all around us’

HQM investigates: The rise of for-profit providers

Housing predictions for 2026

The Crisis CEO on the move to become a social landlord

3 - 26 March

Comms Fest is back –and it’s bigger, bolder and more relevant than ever!

Comms Fest 2026 is your opportunity to step off the treadmill and recharge. Across March, we’ll be hosting a programme of inspiring, practical sessions designed to help you learn, reflect and refresh. Invest a few hours each week and leave with ideas that could transform the way you work.

Visit hqnetwork.co.uk/comms-fest-2026 to find out more.

January 2026

6 AI in housing

Neil Merrick explores how AI can be rolled out in a way that’s safe, accurate and ethical

10 HQM investigates: The rise of for-profit providers

Keith Cooper investigates the rapid rise of for-profit housing providers

14 Matt Downie interview

Jon Land talks to the Crisis CEO

20 Housing predictions for 2026

Housing’s leading lights predict what’s in store for the sector in the next 12 months

The latest research and analysis – in plain English

In this special edition, we highlight recent research by HQN into how social landlords are faring with gaining access to residents’ homes and how they’re preparing for Awaab’s Law.

Editorial:

Design:

Published four times a year. All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part without written permission is strictly prohibited.

This month’s HQM interview with Matt Downie shines a light on the difficulties the government faces when it comes to doing anything meaningful to address the country’s entrenched housing problems.

The Crisis CEO is very much on the frontline of the housing crisis and sees every day the reallife impact of decades of failed policies. But he’s increasingly frustrated at the government’s apparent inability to properly get to grips with some incredibly complex issues and he’s tired of money being thrown at sticking-plaster solutions instead of joined-up, long-term plans.

There’s no doubt that when Labour came into power back in July 2024, housing was one of its top priorities. A policy area where it had the potential to do great things after 14 years of Tory neglect. But 18 months on, despite many noble pledges and dozens of hyperbolic press releases, the pace of change has been glacial, and any positive impact has been miniscule at best.

The headline plan to build 1.5 million new homes by the end of the current parliament is miles off track but that may always have been a touch optimistic given the fact that private developers will only build what suits them. Meanwhile, local authorities and housing associations are nowhere near equipped to fill the void – with the new money for affordable homes only becoming available this year. You can add to this the fact the construction industry faces a major skills shortage that hasn’t yet been adequately addressed.

Equally worrying is the fact that housing policy is starting to move down the pecking order in terms of government priorities. Yes, global issues are dominating the agenda and maybe the momentum has waned following the departure of Angela Rayner but what we’re seeing currently is a series of delayed housing announcements while those that do see the light of day are distinctly underwhelming or watered down from their original intentions.

There’s also an element of confusion in the government’s approach. The Renters’ Rights Act has been hailed by Generation Rent and others as a piece of landmark legislation, but it will do nothing to address affordability issues in the private rented sector while the freeze on Local Housing Allowance continues.

The long-awaited Leasehold and Commonhold Reform Bill was finally published after months of delay but it’s likely to be years before any of the measures are ever properly implemented. Meanwhile, the new homelessness strategy has left Crisis, and others, feeling let down because it continues to focus on short-term solutions, in much the same way as the government’s response to the temporary accommodation crisis.

The concern for the housing sector and the millions of people who rely on it, is that if a Labour government is unable to make headway in addressing these complex problems, what hope do we have when they are kicked out in three years’ time?

Jon Land Editor, HQM

After work last Friday, I went to the Pier Head Tavern. Upon arrival I ordered two pints in the style of Jack and Victor from Still Game. That’s because there were only two of us in the, normally bustling, bar. Why was it so quiet? Yet again the ferries to Arran were off. Waiting for the boat is like waiting for Keir Starmer’s new homes. The powers that be want to do good things but something always trips them up.

The Tories sold off the ports to companies that haven’t looked after them properly. So, it can be tough for the boats to get in and out. In much the same way the Right to Buy ploughs on in England. So, we have fewer homes.

On top of that Mrs Thatcher shut shipyards. The Scottish government has made a heroic attempt to get the industry started again. Many of you will be familiar with the delays and spiralling costs of new ferries. No doubt some of that’s incompetence. But you try starting an industry from scratch all over again. It won’t be plain sailing.

There’s also lots of moaning about the speed of housebuilding in England. Yes, I’m frustrated too. But you can’t just flick a switch. And there are risks with being too gung-ho. You can spend many unhappy hours on TikTok watching videos of dismal new build homes, and we see the rotten satisfaction figures for shared owners in new flats. The adage about walking before you can run springs to mind.

At one time factory homes were the answer. But the production lines seem to be shutting down left, right and centre. Ironically, I stay in a 1970s factory home in Scotland. Trust me, if they can withstand the wind and rain here, they can survive anywhere.

force we united behind. We might need to return to that mindset. Of course, foreign policy will be front of mind for the government. It’s got to be. But don’t ignore the home front. That’s where opponents will pounce. And we know that changing leaders or parties brings one thing – more delay.

Young people can’t get homes. Families are stuck in temporary accommodation for years, miles from where they are from. So much for the new world we were going to get after Covid! You can’t pull the nation together with a ‘homes for heroes afterwards’ line.

Yet, as Ms Rachel says to my grandson about 20 times a day – you can do hard things. Look at the Thames Tideway. We built a 25km sewage tunnel under London more or less on time and to budget. Only a defeatist would say we cannot build more homes.

I may be the person that wanders around the most social housing in the UK. It’s depressing. I’m looking at estates that needed refurbishment 30 years ago and they still do. As the RSH forces landlords to do surveys, we know more about these homes than ever. But identifying an issue isn’t the same thing as solving it. Similarly, strategies sound grand but do not butter any parsnips.

“I may be the person that wanders around the most social housing in the UK. It’s depressing. I’m looking at estates that needed refurbishment 30 years ago and they still do”

A latter-day Beaverbrook must quickly pore over the data to identify the cash required to fix estates. Then the government should cough-up. Yes, the density will need to intensify. That means we must sort out the cost and quality problems of complex flats. And find ways to gain the trust of residents.

Sooner or later the right people with the right techniques will sort out the ferries and homes shortage. That’s the lesson of history. Lord Beaverbrook transformed Spitfire production. As Austin Gray puts it, Beaverbrook’s trademark was: “Find a mess, smash through the polite obstacles, and will results into being. To bureaucrats he was reckless; to production workers he was a saviour. And to the RAF pilots he was…the difference between life and death.”

Beaverbrook himself diced with death. Only a last-minute change of plan kept him off a flight that crashed on Arran in 1941 killing all on board. Back then, war was the galvanising

A Beaverbrook-type would have to pick winners. How would you go about that? Inspectors can tell you what management teams are up to scratch. Start with them and help the others to get better. Inspectors have interpreted the world; the point is to change it. Housing is key to bringing the country together. We must fix it or face the consequences.

Alistair McIntosh,

Chief Executive,

HQN

The use of AI in housing has reached a tipping point during the last 12 months. From a niche tool used primarily by the sector for machine learning and predictive analytics, it’s now become a part of everyday life for thousands of housing professionals. But how can we ensure the technology is rolled out in a way that’s safe, accurate and ethical at a time when regulation of AI in the UK is virtually nonexistent? Neil Merrick investigates.

In some ways, housing associations stumbled across AI by accident. For the past few years, a small number have used predictive analytics to flag up tenants on the brink of serious rent arrears and prioritise where they offer support.

The results are impressive, with landlords that successfully help tenants overcome financial problems reporting fewer tenancy failures and less money lost through properties sitting vacant.

But when it comes to AI, predictive analytics is only scratching the surface and, in some people’s eyes, no more than advanced machine learning.

Those more serious about artificial intelligence are inviting bots or AI tools to check policy documents, compose letters and even analyse complaints. This can include assessing how angry tenants are when they contact a customer services centre.

For the past two years, Thirteen Group has used an AI bot developed by its own employees to verify rent rises for tenants on the national universal credit landlord portal. Its use of Robotic Process Automation (RPA), a Microsoft tool, was backed by the Department for Work and Pensions, which invited other landlords to follow suit.

The bot saves thousands of working hours while allowing staff to focus on supporting customers, says Hassan Bahrani, Thirteen’s director of IT, cyber and data security.

More recently, the association began using Voicescape, an AI-empowered caseload manager, to contact tenants about rent issues. Since 2023, Thirteen’s year-end debt has fallen from 3.24% to 2.55%. “We’re shifting away from tactical adoption of AI to becoming more strategic,” says Bahrani.

‘Guardrails’

Nearly one third of Magenta Living’s office-based staff are trained to use Copilot, Microsoft’s best known AI tool or large language model (LLM). This includes 55 employees who studied at the Wirral AI Academy, set up by Wirral Chamber of Commerce to upskill local businesses and help ensure AI is used ethically.

The important thing, says Ian Cresswell, Magenta’s director of technology, is that housing providers understand and grasp the potential of AI while recognising its limitations and risks. “AI is here and all around us,” says Cresswell. “We’re embracing it while acknowledging the need for guardrails.”

Nowadays, most excitement surrounds the use of generative AI, which can check policy documents comply with government legislation, and ‘agentic AI’, which is able to draft letters and produce other materials.

Among those embracing AI is Hayley Ward,

Magenta Living’s marketing and brand director. The association’s Words Open Doors Agent (WODA) helps staff, she says, to create messages that reflect Magenta’s tone of voice and values, saving time and reducing complexity in the process.

“AI doesn’t replace people. It supports them,” says Ward. “WODA helps us to write letters that feel clear, warm and human, but the real magic comes from colleagues. It means we see the person, not the property.”

Across the sector, most social landlords have adopted a more cautious approach, dipping their toes in the water and seeing what others are doing as the clamour to become more AI-savvy becomes difficult to ignore.

According to Guy Marshall, an AI consultant and board member at One Manchester Housing, AI has only appeared on most landlords’ radar during the past year.

“AI has it uses but, whatever the tech bros may say, there are things that I don’t see it doing in the future”

Mark Shephard, head of data, Yorkshire Housing

The idea of automating decisions is superficially appealing, says Marshall, especially if it cuts costs. But if you’re going to throw data at an LLM, you must be sure all the data is accurate and fit for purpose.

The danger is seeing AI as a ‘magic bullet’ without preparing properly, making the sector vulnerable to pressure from suppliers and vendors of AI. “A lot of providers would love a quick win,” says Marshall, director at data and technology consultants Fuza. “If you automate decisions based on rubbish data, you will simply get bad outcomes faster.”

‘Wild west’

Another problem is that, just as people are getting to grips with AI, the technology changes and throws up new challenges. “It’s like the wild west,” says Ian Wright, founder and chief executive of the Disruptive Innovators Network.

Wright doubts whether, at present, most of the sector knows how to make the most of AI without handing power over to chatbots and other automated tools. “People fundamentally misunderstand what AI is there to do,” he says. “Leaders don’t know the questions to ask,” he adds.

There’s also the problem of AI fakes, exemplified by a barrister who last year relied on

fictitious case histories generated by AI to make his clients’ case during a court hearing. “Most of your role is going to be that of an auditor,” says Wright. “You’re going to have to check AI because it lies.”

Regulation of AI in the UK is almost nonexistent, increasing pressure on housing association boards and local authority landlords while at the same time giving them more freedom to explore and test the potential of AI.

In November, as part of its latest risk profile of the sector, the Regulator of Social Housing said: “It’s important that landlords manage their data in accordance with all relevant laws and regulations and understand the implications for data protection of adoption of new technologies such as AI.”

For the past six years, a predicting tenancy failure model created by Together Housing has been 84% successful in forecasting when tenants are in danger of losing their home due to rent arrears.

Since 2023/24, the housing group calculates that it’s saved more than £3m by correctly identifying tenancies that are at risk, making targeted interventions, and providing residents with wraparound support rather than needing to relet homes.

Together owns more than 38,000 properties, mostly in northern England, and employs 1,600 staff. Eight years ago, Stephen Batley, its assistant director of business development, was appointed to improve the way the group compiles and uses data, and subsequently ensure AI did not “run amok”.

Eight years on, Batley says the success of the tenancy failure model shows how a combination of effective data science and personalised skills shown by Together’s staff can help tenants to remain in their homes.

In addition to achieving 84% accuracy in forecasting tenancy failure, the model is 81% successful in identifying preventable terminations and classifying reasons for a tenancy being terminated.

Data scientists experimented with various models and techniques to come up with the model, while consulting frontline staff who understand residents as individuals, adds Batley. “This project is the perfect example of marrying the technical with the human to make a positive difference to people’s lives,” he says.

The savings made since 2023/24 coincide with turnover of properties falling from 15% to 6%. Among the factors taken into account are the age of tenants and the type of property they live in, with staff focusing on the most vulnerable households.

According to Batley, it’s important not to become too dependent on AI and recognise how predictive models are complemented by human endeavour. “We’re trying to take a balanced approach and use AI in a pragmatic way while ensuring there are checks and guard rails,” he adds.

This isn’t the case in wider Europe. From next month [Feb], housing providers in the EU must comply with the AI Act. Staff will need at least a basic level of AI literacy if they use AI for allocations, risk assessment (including rent arrears and antisocial behaviour), fraud detection or customer contact (such as chatbots).

“Employees who work with AI must understand what the system does, what the risks are, and how human oversight is exercised,” says Henk Korevaar, ambassador at CorpoNet, a Netherlands-based network for housing associations.

“Having a minimum level of AI competency doesn’t mean that everyone needs to become a data scientist or programmer,” he adds. “It means that organisations must ensure that employees who work with AI understand what they are doing and where their responsibilities lie.”

While the UK largely relies on self-regulation, social landlords have it within their powers to ensure things don’t go badly awry. AI may be crying out for data, but it can also help organisations to improve its quality.

At Magenta Living, Ian Cresswell points to their data platform Microsoft Fabric as an effective way to rationalise data. The association also uses Microsoft Purview, a governance and compliance platform, to monitor exactly how far AI reaches into the organisation and ensure AI is kept in check. “There’s always a human in the loop,” he says. “AI should support decisions, not make them alone.”

There are also signs of social landlords working in tandem. Thirteen was keen not to commercialise its use of the RPA tool for verifying UC claims and recommended it to Platform Housing Group.

“It’s important that we’re sharing as a sector,” says Hassan Bahrani. “Ultimately, the customer is going to win.”

Bahrani stresses that staff continuously check the accuracy and validity of decisions made by the bot, while an AI ethics committee is under consideration. “If you use AI with colleagues or customers then you should be transparent

“People fundamentally misunderstand what AI is there to do. Leaders don’t know the questions to ask”

Ian Wright, chief executive, Disruptive Innovators Networks

about how AI is part of that process,” he says.

In addition to using RPA for universal credit claims, Platform introduced the ‘silent tenant’, a tool for checking on the welfare of elderly and more vulnerable tenants who haven’t been in contact with the association for long periods.

Each tenant receives an automated call and, if they fail to respond via their phone keypad, an officer visits their home. “The machine is thinking for you to provide a better outcome,” says Jon Cocker, Platform’s chief information officer.

Since early December, residents calling Bromford Housing Association’s customer service centre in Wolverhampton have initially been welcomed by an AI-supported interactive voice response (IVR) system. The call is then put through to a member of the customer services team, who’s aware of the caller and why they contacted the association.

Colin Goodbody, head of customer operations at Bromford, says the association isn’t only providing a better service but can collect data revealing typical problems, as well as ‘customer sentiment’. This is used to support training and improvements to services.

Later this year the service will be expanded so, rather than callers being put on hold, AI provides staff with articles and other information that can be quickly relayed to callers. “It’s not about creating agents that are robots and taking away personality,” says Goodbody. “It’s about enabling our colleagues to help customers more efficiently.”

Yorkshire Housing is in the throes of testing how AI can analyse notes made by call centre staff during discussions with tenants who make complaints, including the sentiment expressed by complainants.

Mark Shephard, the association’s head of data, performance and information security, stresses that it’s early days, but believes AI has the potential to help staff understand the root causes of complaints faster and prioritise improvements.

AI, explains Shephard, can examine large volumes of text in ways people find tricky, if only due to the time involved. But there’s also a level of bias in judgements made by an AI tool or app that staff and organisations must take into account.

Ultimately, AI is here to stay. As

AI dos and don’ts DO

• Ensure staff using AI are fully trained and understand what they’re trying to achieve

• Require staff to check decisions made by AI, including negative judgements that affect tenants

• Check data used to generate decisions via AI is accurate and fit for purpose.

• Be afraid to explore the full potential of AI for housing

• Use AI for communication or making major decisions without informing tenants and other customers

• Allow AI to run wild and take over operations or decisionmaking.

“If you automate decisions based on rubbish data, you will simply get bad outcomes faster”

Guy Marshall, director, Fuza

LLMs build up case histories, they should become more knowledgeable and hopefully proficient. AI also has the potential to take the drudgery out of day-to-day tasks, including checking guidance or reports.

All this doesn’t mean social landlords need fear AI or should allow it to call the tune. “AI has its uses but, whatever the tech bros may say, there are things that I don’t see it doing in the future,” adds Shephard. “While it may help us identify efficiencies in our business processes, I don’t think AI is going to be removing people’s day jobs.”

Since 2017, the number of homes owned by forprofit registered housing providers has shot up more than 50-fold. But can they be considered a force for good in the sector or something to be feared? Either way, as Keith Cooper discovers, they are here to stay – and likely to get bigger.

There are some big claims circulating about so-called forprofit registered providers and their multi-billion-pound investors.

For-profits will triple in size from around 43,000 homes to 150,000 by 2030, the consultancy Savills claimed in its report, A Growing and Diversifying Sector, last year. “There’s a clear ambition from investors to scale up their portfolios,” it adds.

The investors themselves have offered “to unlock” £100bn of affordable housing funding by taking housing associations’ homes off their hands, wholesale. So says Sir John Kingman, the former Treasury minister and Legal & General Group chair, in an advice column to government, entitled “We’re going to need a bigger Bazooka”. “Insurers and pension funds would lap these [homes] up,” he says. “This would leave housing associations with huge new cash reserves…[and] unlock a large increase in social housebuilding,” he adds.

Even the US president appears to have given the growing band of for-profits in England a bump. Donald Trump’s planned ban on big US corporate investors buying up single family homes across the pond could prompt an acceleration of interest from investors, HQM has been told.

So, what exactly are for-profit providers? Where have they come from and where are they going? And are their plans for expansion something to be celebrated or feared?

To find out HQM, has spoken to the three largest forprofit providers, scoured official figures, and spoken to their advisers as well as the Regulator of Social Housing (RSH) which oversees both the centuries-old housing association sector and these for-profit newcomers.

For-profit registered providers were introduced by the Housing and Regeneration Act in 2008 with the first registrations allowed two years later. RSH figures show registrations dribbled in initially by two or so a year and that many of these first for-profit providers grew slowly, if at all. Most of the early adopters had fewer than 100 homes, according to an RSH stock take in 2020.

Investors showed more interest in for-profit providers in 2017 after the RSH lost its power to block them from selling their social homes as part of a deregulation drive by the

“We feel that what we do as a business is of great social value. There’s a significant housing crisis in this country, and we’re proud that we’re able to play a small part in providing much-needed homes”

Heylo

then Conservative government. “This meant for-profits could trade more freely in social housing assets”, RSH deputy chief executive Jonathan Walters told HQM.

“Registered providers do have to tell us when they are selling homes and we can launch a regulatory investigation or follow up if we need to. But we don’t have any formal blocking power,” Mr Walters adds.

The RSH soon showed it would act on social housing trades which fell short of its remaining regulatory rules. In 2018, it downgraded the governance rating of non-profit association Moat Homes for “insufficiently robust” due diligence in its sale of 26 occupied homes for older people to a small for-profit provider.

Board approval for the sale had been considered “solely on financial criteria” the RSH judgement states. “Due diligence of the proposed purchaser was insufficiently robust to demonstrate accountability to tenants and obligations to protect social housing assets,” it adds. Moat Homes was approached for comment.

This early baring of what regulatory teeth it had left didn’t deter investors from backing for-profit providers. Instead, the number of for-profit registrations began to rise. Legal & General had its first for-profit provider granted registered provider status in late 2018 and has registered several more since then.

Around this same time, a small trade began to develop in the for-profits organisations which had already registered. These could now be bought off the shelf by investors instead of them registering their own organisations, a lengthier process involving more stringent checks by the RSH. This trade has recently become highly lucrative with registered for-profits changing hands for six-figure sums, despite some being no more than shell companies with no homes and no staff, HQM understands.

Heylo and Sage

Two of the biggest for-profit providers today, Helyo and Sage Housing, began by purchasing existing providers.

Heylo, was established in 2017 by purchasing Three Conditions, a for-profit which had registered with the RSH five years beforehand. The company’s 2017 accounts described Three Conditions as an “intending provider of affordable housing but hadn’t acquired any properties”.

Heylo says it has since attracted more than £2bn of “global capital” to invest in affordable homes through this previously redundant organisation. It’s gone from zero to 10,000 shared ownership homes in nine years and has plans to expand over the coming years. “We feel that what we do as a business is of great social value,” a spokeswoman told HQM. “There’s a significant housing crisis in this country, and we’re proud that we’re able to play a small part in providing much-needed homes,” she added.

“Regardless of how a provider is acquired, they must meet all our standards and we’ll use a range of tools to check they’re doing so”

Jonathan Walters, deputy chief executive, Regulator of Social Housing

Sage Housing also joined the for-profit sector by purchasing a provider formerly known as ‘180 Housing’ in 2017, according to Companies House records. By the end of that calendar year, this entity owned just four homes. But backed by billions of pounds from investment industry titans Regis and Blackstone, it claims to have delivered 20,000 homes over the past five years and is now England’s “largest provider of new affordable homes”. Sage Housing has the RSH’s highest rating for governance (G1) and ranks highly in tenant satisfaction measures with 86% of its rental customers satisfied in 2024/25, it says.

‘Real problem’

Mr Walters says the ability of for-profits to buy and insert a registered provider in a wider company structure was a “real problem”. “If they’re coming through the normal registration process we’ll ensure that what ends up on our register is something we regard as a proper organisation that’s able to manage its stock,” he adds. “Otherwise, the registered body can end up in a very odd structure where the RP is essentially a pass-through vehicle. But regardless of how a provider is acquired, they must meet all our standards and we’ll use a range of tools to check they’re

doing so.”

While Mr Walters doesn’t name Heylo the RSH linked “serious regulatory concerns” about its financial viability and governance to its business model, in its first regulator judgement of the for-profit in 2022.

Under Heylo’s business model, the judgement alleges its registered provider has “nominal ownership” of its properties, derives “no economic interest” from them, and has “effectively ceded control of its social housing assets” to a series of companies connected to the provider, called ‘investment pods’. “All income is passed through to the investment pods via a managing agent, also connected to the Heylo group,” it adds. Heylo told HQM: “Work continues to restructure the business, and we meet regularly with the regulator to review progress.”

After the early sluggish growth in for-profit portfolios, the number of homes that they own has shot up more than 50fold since 2017, from 873 to 46,555 in 2025. Sage Housing, L&G, and Heylo hold most of the for-profit stock, according to Savills.

‘Big

Consultants and advisers to for-profits say they expect this sub-sector to expand further this year as investors “with big pockets” enter market, interest from those in the US is likely to “accelerate”, and housing associations put “large portfolios” of homes on the market which only for-profits can afford. L&G has reaffirmed its “unashamed” offer to free up capital “trapped” on housing associations’ balance sheets by buying them up.

“‘We’re still getting interest from both investors and housebuilders in establishing new for-profit registered providers,” says Rob Beiley, a partner at law firm Trowers

“They [for-profit providers] are looking at different ways of raising capital such as through local government pension schemes and US hedge funds; there are some people with really big pockets looking to enter the market”

Steve Partridge, director, Savills

& Hamlins. “Even before Trump’s pronouncement, a number of north American investors have been speaking to us and this is likely to accelerate,” he adds. “‘The for-profit sector is one which is still growing.”

Steve Partridge, director of housing consultancy Savills, says he expects to see several key trends for for-profits this year and beyond. “They’re more likely to do more social rent. They’re looking at different ways of raising capital such as through local government pension schemes and US hedge funds; there are some people with really big pockets looking to enter the market,” he adds. “We’re also going to see more housing associations set up their own for-profits or enter into joint ventures with them or equity investors.”

Mr Partridge says he also expects to see housing associations seek to raise capital funding by selling off their occupied homes. “There are a number of large portfolios of homes coming onto the market and realistically it’s only going to be for-profits or investors which can buy them.” He points to housing associations’ latest financial health check, the RSH’s Global Accounts, which shows a further deterioration in their financial health on several key measures, including their capacity to service their own debt.

L&G Group managing director of public investment Pete Gladwell reiterates Sir John’s suggestion that housing association sell-offs could “unlock” huge amounts of housing supply while helping them pay down their debt. He stresses that L&G does a “huge amount of its new delivery” but says there’s a “fundamental point” that should be considered by the sector.

“There’s a lot of capital value and grant that’s trapped within housing associations at the moment,” Mr Gladwell adds.” If they [associations] move their existing homes to the right type of equity they can unlock huge amounts of additional supply, additional subsidy and economic growth and reuse those proceeds to pay down debt and deliver new homes,” he told HQM. “We’re totally unashamed that we think that more of this should be going on because there isn’t enough grant to go around and there’s huge amounts of trapped subsidy and capital within the existing registered provider sector.”

But is this all for the good?

Alan Green, a former development director for several major housing associations, is concerned that the level of

“We’re totally unashamed that we think that more of this should be going on because there isn’t enough grant to go around and there’s huge amounts of trapped subsidy and capital within the existing registered provider sector”

Pete Gladwell, managing director of public investment, L&G Group

indebtedness now borne by non-profits leaves them open to being “eviscerated as an investment opportunity”.

“Private sector investors make very positive noises about getting involved in low-cost housing but ultimately for them it comes down to value extraction as a simple investment asset” he adds. “Affordable housing is an essential service and so comparisons can be drawn to past privatisations of public services/utilities – what they promised, what they look like now and how happy are people with them.”

But Mr Beiley says the thinking “in some parts of the sector” that not-for-profits are good and for-profits are bad was “hugely damaging”. “The reality is, there are good and bad landlords in all parts of the sector.”

And Mr Partridge points out that the government plans to invest just £4bn of the £19bn needed annually to build the 90,000 social-rented homes a year England requires. “And people still ask why we need them,” he adds.

The question of whether for-profits and their deeppocketed investors are a force for good or bad for tenants is unlikely to be settled anytime soon. Meanwhile, they look set to become a much-needed source of funding and a permanent fixture on the affordable housing landscape.

“WE’RE NOW IN A SITUATION

POOR FOR SOCIAL HOUSING”

Matt Downie has been at Crisis for over a decade and its CEO since 2022. In that time the homelessness crisis has got worse, despite successive governments throwing millions of pounds at it.

With unwanted records being broken with every statistical release, Crisis has had enough of stickingplaster, short-term solutions and the failure of housing associations to play their part in addressing homelessness. It feels direct action is needed so it’s becoming a landlord in its own right.

In this wide-ranging interview, Downie discusses the charity’s long-term plan to become a registered provider, his disappointment at the government’s new strategy to end homelessness, and why allocations schemes and affordability checks mean social housing is no longer available to the poorest in society. HQM editor Jon Land asks the questions.

Jon Land: You’ve been providing hotel accommodation for homeless people in London as part of the latest Crisis at Christmas campaign. How’s that been going? How do you decide who gets to stay in the hotels?

Matt Downie: Yes. So, the Crisis at Christmas operation these days is quite unrecognisable to when I first started. It’s a mixture of things, not just in London but around the country, but the hotel bit is London-centric. What we do is take over as many hotels as we can get hold of, which is a difficult business. But what happens is that we’re effectively booking space for people who are on a referral list from the local councils and the GLA. We’re looking for specific cohorts of rough sleepers particularly those with high needs, but not so high that we can’t safely accommodate them. We’re not talking about people who are new to the streets. It’s people who are longer-term homeless but not necessarily engaging with other services.

We provide a volunteer-led, hugely welcoming service which is all about generosity and the fact that people (when they’re with us, we refer to them as guests) have a pampered experience as well as the housing casework that goes along with it. It’s all to do with having good relationships with the local councils, particularly Westminster and others who have high rough sleeping populations.

JL: Crisis is very much on the frontline when it comes to tackling homelessness. Just how bad is it out there currently?

“I remember meeting a guy in Liverpool who had been in the same hostel for 10 years. And I said to him, what was the issue when he first got here? And he said rent arrears. He just needed some help paying off his rent. Ten years later, the state had spent

a fortune institutionalising him”

MD: Homelessness is very bad everywhere and pretty much every record is broken every time there’s a new statistical return. We’re in a situation where all of the different causes are converging at once, so you’ve got a situation where it’s not just an increase in rough sleeping, it’s an increase in temporary accommodation, in different forms of hidden homelessness, in different demographics. So, at any one time you could put out a report about the rise of homelessness in young people or older people or people who are disabled or people who are neurodivergent or whatever it might be. Care leavers, prison leavers. It’s a sort of everything moment, really. All our services are seeing an increase in demand year-on-year. We’re also seeing the withdrawal of the safety net. I remember years ago doing mystery shopping of housing option services that now don’t even exist. The whole situation has changed. I could give you some horror stories from recent years. It’s really quite grim.

This year we had our first women’s service for female rough sleepers and that itself is a kind of a new venture where we’re working with female rough sleepers who will quite often be some of the most terrified, abused and disgraceful cases of institutional and social neglect you’ll ever see. So, we’re proud to have done that too.

For the people who are the most difficult cases, where we haven’t found housing options for them, we’re taking longer to do it by extending the service to the end of January. We have a case management team for that, and we also work in partnership with Saint Mungo’s. It’s about throwing everything at the situation to make sure that people don’t go back to the streets. Last year, 60% of those people didn’t, which for a fairly short-term intervention is pretty remarkable.

JL: We know that the homelessness sector has been frustrated by the lack of action and funding from successive governments. Do you see this changing under the new National Plan to End Homelessness? What more do you think the government should be doing?

MD: In terms of ongoing frustrations with government, it’s not really to do with spending on homelessness. It’s to do with the right spending to prevent it or to stop it. Actually, I think successive governments have spent a huge amount on servicing the problem. I think it’s over £3 billion now that’s been spent on temporary accommodation. You’ve probably heard all these statistics before, but £5 million a day is spent on temporary accommodation in London alone.

This is to do with both a complete inability or lack of willingness to tackle the genuine causes of homelessness and throwing money at short-term management solutions rather than

“I did say to the senior civil servants, when they got in touch to say that the homelessness strategy was out, how gutted I was by it. We saw it as a failure of not persuading them that a different approach was needed”

sustainable solutions. I think the strategy that’s been published is a valiant effort to continue that sort of frame of thought and does include some good things. But it really isn’t getting at the long-term solution or changing the dialogue of how we approach this issue, beyond just sticking plasters.

The document is fascinating because it’s far more honest about where homelessness comes from than any government document I’ve ever seen. It’s really clear that there are structural and welfare and immigration and housing supply policy-based causes. But the actual measures in the strategy to tackle the problem don’t include those things.

If this was a prime minister-led thing, like the New Labour targets on homelessness in the late ‘90s, you would see other departments being told to lift their weight on local housing allowance, the move-on period for newly granted refugees, the throughput of care leavers or prison leavers. There are some green shoots in some of those things, but it’s not enough. We’ve been waiting for years for this. I’m more gutted than I’d normally be because I think a lot of the aspirations were raised and, particularly when Angela Rayner was around, we were expecting something a bit bigger than what we got.

I don’t know what happened within the machinery of government, but if you think back to the weeks leading up to the general election and the manifesto pledges around homelessness, about a cross government approach and having a deputy prime minister that was leading on ending homelessness and not just the housing secretary, all of those things pointed to finally having enough political capital within government for the sustainable solutions to be on the table.

Fast forward and what we’ve got is a version of the political capital that homelessness has always had, which is “the numbers are high and we’ve got to do something”. In every government press release, they will say “we’re spending £2 million or X billion on this” and can rightly claim that there are good things happening. But what they can’t credibly claim is that every lever has been pulled to stop the causes of homelessness.

JL: There’s no doubt that the temporary accommodation crisis has snowballed in recent years, putting pressure on homeless services and local authority finances, while at

the same time forcing some families to live in really poor conditions. Do you have thoughts on what can be done to address the situation beyond what’s currently being mooted by government?

MD: The macro picture of this is that, as a country, we’ve become addicted to spending all of the available money on temporary solutions. When you look at the sheer scale of [the temporary accommodation crisis] and the fact that it threatens local authority finances, what you realise is that we need to switch to a housing-led solution where there’s sufficient stock for everyone to live in a proper home and a future where there’s enough new delivery coming through.

What I’d love to see is a focus on how truly affordable and social housing is the way to get off the hamster wheel of temporary accommodation, both for the costs that it accrues and the sorts of conditions people are being forced to live in. We need to stop grinding down our expectations for what standards we deem acceptable for people to live in.

Until there’s enough social stock to go round, the critical thing is to allow affordability back into the private rented sector. But [the government]

is not doing that. And they’ve expressly said they won’t. I think that’s just a critical mistake. Of course, the Treasury will always say it’s just money down the drain, giving money to landlords, portfolio landlords and all the rest of it, but until you do that, what you’re actually doing is increasing the number of people who are going to need some form of subsidised housing, so council waiting lists are going to get longer.

JL: That brings me on to the recent research Crisis commissioned that shone a light on social housing allocations. It demonstrated that those in most housing need, such as homeless people, aren’t necessarily at the top of the priority list. Are you able to share your thoughts on some of those findings?

MD: The first thing to say is that we’re in a situation in England where, particularly compared to Scotland, the ability to use the

social rented sector via housing associations for resolving homelessness is far smaller and the powers to make that happen are far weaker. That sort of deregulation has meant it’s really hard for an organisation like ours, which is trying to get access to social housing. It all has to be done based on local relationships. And that’s not just for charities. It’s often the same for local authorities.

The research shows that we’re in a situation where, according to a number of housing providers, you can be too poor for social housing. I’m not sure anyone expected to see that coming. I suppose it’s just symptomatic if you build everything around affordability checks.

There’s a reason why we’ve fought for and got what’s called the Homelessness and Social Housing Allocations Bill in Wales. There’s a reason why we’ve fought for and got something in the homelessness strategy, about increasing social housing and allocations to homeless households. There’s a reason why Crisis is having to think about starting to deliver its own stock. And it’s simply because the housing stock that’s meant to be for people who have nowhere to live is no longer available.

JL: Can we be specific about this? We’re talking about housing associations essentially opting out of local waiting lists and not having a statutory duty to do anything about homelessness. So, they can pick and choose who they house.

MD: Yes, totally that. It’s really hard to label a whole sector. And I must say, we work with lots of very good housing associations, particularly through the Homes for Cathy group that’s specifically dedicated to tackling homelessness. But it’s now so commonplace to say either they can simply opt out or that if these are households with support needs, where’s the money coming from to pay for that support? So, they are opting out of ever providing housing to those people.

We then enter a sort of death spiral where the

“There’s a reason why Crisis is having to think about starting to deliver its own stock. And it’s simply because the housing stock that’s meant to be for people who have nowhere to live is no longer available”

percentage of homeless households goes up with nowhere to go. I remember talking to the [social housing] regulator a couple of years ago about whether they could do some monitoring of the percentage of allocations to homeless households by registered providers and the percentage of households who are evicted into homelessness so we can start bringing into the light what the reality of this is. They absolutely refused that and didn’t want to go anywhere near it. That’s why we ended up doing the research because we were seeing it on the frontline every day.

JL: I suppose the mitigation is that with the affordable rent regime becoming the only game in town for any sort of grant funding, social rented housing has been off the table for a long time. Would you accept that?

MD: Absolutely. And I think it’s completely naive to just say we need the housing association sector to suddenly rediscover its 1960s roots. The changes made by the coalition government to what affordability is, and the changes to section 106s, that’s definitely all in there. But I totally refute the idea organisations, particularly big organisations, can do nothing to help. I won’t name them, but I could tell you about some large organisations who won’t even give us two or three units to tackle homelessness.

Some of these organisations will have foundations they have set up to deal with social issues and I’m thinking to myself – hang on a second, just put a little bit into the subsidy you need to make this tenancy work or for it not to break down. I think it’s sometimes about large organisations rediscovering the reasons why they were set up in the first place and what their purpose really is.

I think there’s a genuine opportunity for a partnership going forward where we can join forces to get people’s situations improved. Everyone is facing pressure. Whether you’re a private landlord, social landlord or a council trying to build or retain its own stock, all of that stuff is hard. But we can make a collective case for a better grant regime or for sorting out local housing allowance or whatever it might be.

JL: You’ve already alluded to it, but is this one of the driving factors for Crisis going down the housing landlord route? Can you tell us about that and where things are currently?

MD: There are two reasons for doing this. First and foremost, we’re helping 10,000 people in our year-round services and at the moment we get about 40% of those people sustainably out of homelessness a year. That’s not enough. The number one thing standing in the way is access to homes. The second reason is that the revolution that’s happened elsewhere in the way in which homelessness is dealt with, and that it requires a housing-led solution – rather than just something that should be managed – hasn’t reached these shores.

If you go to a vast array of countries, across Europe and the wider western world, you see now that the modern approach to homelessness is nothing to do with providing temporary accommodation and tinkering with short-term solutions. It’s saying we’re going to systematically close down our old institutions – our big hostels, our big shelters – because they don’t work anywhere near as well as giving people a home of their own and the support if they need it. We need a housing first principle that runs through the whole system.

Things are just getting more and more urgent. So, from a standing start, the plan is to directly raise the money as a charity for the acquisition of our first hundred homes, and then to look at the different finance options once we’ve developed a credible track record in tenancy

support and housing management. We’ve got to this conclusion because we’ve run out of other options. We also think we can prove a point by doing it.

The ultimate ambition is that we can provide a housing option for all the 10,000 people that we see. We also want to provide the evidence base to show that you can completely cut out the need for temporary and emergency accommodation.

JL: Do you have any homes currently? If so, where are they and what’s the plan?

MD: So, the first phase is us becoming a landlord and we’ll do that in London and Newcastle to start with. That’ll just see us buying one or twobedroom flats on the open market. But we have it in mind to act from day one as if we’re preparing to become a registered provider.

We expect to exceed all of the quality standards and all the rest of it, but we’ll have to have in mind where we want to go in the future. That second phase of [ramping up] the amount of stock will have to involve financing of a nature that we can’t access now because we’re not a registered provider. I’m currently recruiting the person that’s going to lead this housing company. So, the company’s set up, we’ll start the purchasing in April and May.

In London, we’re also setting up our own lettings agency, which will do a lot of the housing management side of this as well.

“I [talked] to the [social housing] regulator a couple of years ago about whether they could do some monitoring of the percentage of allocations to homeless households by registered providers and the percentage of households who are evicted into homelessness. They absolutely refused that and didn’t want to go anywhere near it”

replicate housing for people who would get it otherwise. We’re going to be providing housing to people who get nothing, who are routinely told they’re not a priority or who would never get access to social housing.

What I really want to do above all else is demonstrate that, even in the hardest cases of homelessness, we shouldn’t be consigning people to a life of temporary accommodation or emergency housing.

JL: Am I right in saying that you’re aiming for 1,000 homes within the next decade?

MD: Yes, that’s what’s written down. But I have to say, Jon, I would be gutted if it’s just 1,000.

JL: I want to finish by asking you about Matt Downie the person. What motivates you to do the job you do? And what do you do to unwind?

MD: In terms of motivation, I often think that if you’ve become cynical and fatalistic about homelessness, you need to get out of the way and let somebody else take over who’s got the fire in their belly for long-term solutions.

I’m constantly motivated by wonderful organisations in this country and other places, but I did say to the senior civil servants, when they got in touch to say that the homelessness strategy was out, how gutted I was by it. We saw it as a failure of not persuading them that a different approach was needed. That’s how I felt about it personally.

I don’t think they’d ever heard a sentence like that. I’ll try and organise a meeting to have a genuine conversation because I think that the evidence is so compelling.

I guess tied to that is the fact that I do have the privilege of seeing cases where the most extreme kind of entrenched or complex homelessness has been overcome.

JL: And presumably there will be a support element to the housing you provide?

MD: Yes, exactly that. The absolute gift to the local authorities that’ll work alongside us, as well as all the other support services, is that crisis –through its own charitable funds, which we raise from the generous British public – will provide the tenancy support offer to people What we’re not doing here is seeking to

I remember meeting a guy in Liverpool who had been in the same hostel for 10 years. And I said to him, what was the issue when he first got here? And he said rent arrears. He just needed some help paying off his rent. Ten years later, the state had spent a fortune institutionalising him. That’s the sort of thing I find so frustrating but motivating at the same time.

To get away from work, I try and do things that force a bit of mindfulness. I’ve taken up some fairly extreme challenges, like going cycling from London to Edinburgh and walking across the Sahara and stuff. Things like that force you to totally forget everything else. But the honest answer is that I don’t switch off enough and I probably need to sort that out.

As 2026 gets underway, we have invited some of housing’s leading lights to predict what’s in store for the sector over the next 12 months (and beyond). AI (obviously), cybersecurity, geopolitics, housing delivery and homelessness are just a few of the issues on the radar.

Amanda Newton, Chief Executive of Rochdale Boroughwide Housing

Housing is one of the clearest ways for government to demonstrate that the decisions it’s making are tangibly improving people’s lives and strengthening communities. That means landlords will need to show not only that we can build, but that we can lead long-term, place-based renewal that creates pride, opportunity and growth.

Hassan Bahrani, Director of IT, Cyber and Data Security, Thirteen Group

Looking ahead to 2026, we can expect the social housing sector to shift into a delivery phase and most providers are shoring up for that now, alongside partners including mayoral combined authorities and Homes England.

The pressing issue of the need to regenerate homes that are at end of life to create places where today’s and future generations can thrive will remain front and centre for many providers. Having an open dialogue about how this goes way beyond retrofit will need to be a conversation that’s given serious focus.

The drive for service reform will continue. Artificial intelligence and better use of data and new technology will play an important role in improving efficiency, predicting risk and helping us target resources where they can have the greatest impact. However, we must learn from the past. Innovation cannot come at the expense of genuine customer engagement with the voices of the people we serve heard loud and clear in the business and the boardroom. Housing is a people business and this means we simply cannot lose the human connection between landlords and the people who live behind our doors.

The challenge for 2026 will be balancing technological progress with trust, transparency and strong relationships, ensuring transformation ultimately delivers better outcomes for residents.

By 2026, social housing should be defined by smarter and more automated operations with stronger compliance. Artificial intelligence will become a practical tool rather than a buzzword by helping landlords predict repairs, automate routine tasks and improve customer service without adding cost. Combined with cloud platforms and integrated data, this will enable real-time insights for asset management and tenancy support to name a few.

Governance and regulation will tighten as technology adoption accelerates. I expect clearer regulation and legislation on data ethics and data quality, cybersecurity and transparency. Digital tools will support a range of business operations, but success will depend on robust controls and skilled people – good brakes make you go faster!!

Ultimately, the ones who gain the most will be those who balance innovation with trust and security, using automation and analytics responsibly while keeping the ‘human-in-the-loop’. Technology will help us deliver better homes and experiences, but governance and culture will ensure we do it the right way.

Helen Barnard, Director of Policy and Research, Trussell

My prediction for 2026: maintaining the Local Housing Allowance freeze will become untenable. Unaffordable private sector rents force people into impossible situations – having to go without food and other essentials, building up debt and into homelessness. After being frozen for several years, in 2024 the government relinked LHA to the bottom 30% of rents, but then froze it again. The Resolution Foundation estimates that since then the gap between rents and LHA has grown to 14%, a shortfall of around £104 a month. That gap is predicted to reach 25%, £180 a month, by 2028/29. This will drive up hardship and undermine positive action to tackle poverty and ease the cost of living. It’ll also continue to increase the cost for councils of paying for temporary accommodation, which has more than doubled over 10 years, reaching £2.8 billion in 2024/5. The government is banking on being able to raise living standards over the next few years, but with LHA frozen, rents will keep dragging real incomes down. Surely 2026 will be the year they bite the bullet – relink LHA to rents and adjust the public finances so that this becomes the default position in future years?

Nick Atkin, Chief Executive of Yorkshire Housing

As we move into 2026, the big question is whether this will be the year ambition finally turns into delivery. A huge amount depends on the economic climate. If the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee reduces interest rates further and faster, this should boost confidence in the housing market, which is currently flatlined – helping to restart stalled schemes and allowing development programmes to pick up pace. Without these reductions, our ambitions for the year will be much harder to deliver.

“Will this be the year we see the first AI board member? On a human level will this be the year of the first housing provider to appoint a chief AI officer”

Ian Wright, Disruptive Innovators Network

Political frailty will remain part of the operating environment. The local elections in May are predicted to bring changes in control across many councils. We’ll need to stay focused on our core aims and purpose, adapting to shifting political priorities to ensure housing stays high on the agenda. Where devolution is working well and partnerships are strong, we’re already seeing more joined-up approaches making a tangible difference.

Regeneration will become even more important, as we know building new homes alone isn’t enough to address the challenges many communities face. But there are genuine reasons to be optimistic about 2026. Long-term commitments like the Social and Affordable Homes Programme and the 10-year rent settlement are giving the sector much-needed stability and confidence. At the same time, digital transformation and AI-led change are starting to translate into real-world improvements for customers and communities. If 2025 was about laying the foundations, then 2026 has the potential to be the year we start seeing those plans delivered.

Samantha Grix, Partner, Regulation and Governance, Devonshires

In the autumn budget the chancellor didn’t announce the much anticipated decision on rent convergence. The official word was that it would be announced in January 2026 before the Affordable Homes Programme guidance. By this time, RPs will be well into their preparations for implementing April increases which may mean that even if rent convergence is approved to commence from April 2026, RPs won’t actually be able to implement it due to the short timeframe to work in. I wonder if this is a way of delaying implementation without having to officially say that convergence is going to be delayed a year. Whether formally or due to operation challenges, my prediction is that rent convergence will be delayed until 2027.

“Maintaining the Local Housing Allowance freeze will become untenable”

Helen Barnard, Trussell

Rob Gershon, Associate, HQN

Sheron Carter, Chief Executive, Hexagon Housing Association

2026 looks set to be dominated by geopolitics with profound effects on financial markets.

A topic that I’ve been following on social media is global decoupling from the dollar, which looks likely to gather momentum in the year ahead. Since 1944 the dollar has been the international currency for cross border trade, investment and foreign reserves.

A growing number of countries are looking at alternative currencies to reduce their dependency on the dollar for international trade and financial transactions.

So, why is this important? Well, apart from increasing global tensions, these changes can impact market confidence, investor confidence, exchange rates and inflation.

Rent convergence, the Planning and Infrastructure Bill and the Warm Homes Plan are all positive measures to boost housebuilding and the housing market that the government will roll out in 2026. But delivery relies on an economy that’s stable and growing and geopolitical players with cool heads and common sense.

The UK government will need to be bold to strengthen sterling as an alternative currency and seek parity in economic partnerships that work for mutual good.

Making predictions in such an uncertain world feels like a fool’s errand but we’re fortunate that in and around the housing bubble some of the things that need to happen are concrete. It feels predictable that pursuing major changes to planning will continue through 2026 and the government’s slightly authoritarian views on immigration and state surveillance will continue to make sourcing and employing a skilled workforce more difficult. With three different groups angling for a national tenant body – a union, an alliance and a federation – and finding listening ears in government, the way that power is unevenly distributed between landlords and tenants has the potential for some much-needed change. With the chief executive of the regulator standing down there’s scope – perhaps hope – for a slightly more proactive regime on consumer standards. For tenants and residents, 2026 is a critical year. With the Regulation of Social Housing Act still bedding in, TSMs still scoring below average, and lessons on consumer standards and maladministration seemingly not learned, there’s an opportunity to shape how this ecosystem works. Many of the promises of the act remain unfulfilled for tenants, promising a year that should prompt more changes in governance priorities.

Paula Heatley, Director of Development and Sales, Platform Housing Group

As the sector prepares bids for the Social and Affordable Homes Programme, organisations are refining their development strategies and long-term financial plans to support growth. With financial and regulatory pressures intensifying, providers are watching government announcements closely, particularly on rent convergence and the availability of low-cost, government-backed finance. Progress in these areas could give organisations the confidence to pursue more ambitious development plans and increase investment in their existing portfolios. Without such support, however, many will see their capital stretched as they work to meet the demands of a more robust regulatory environment.

Looking ahead to 2026, there’s hope that both local and national government will do more to remove barriers to delivering new homes. While improving the planning process has been a long-standing priority, the focus must now shift to enabling essential infrastructure, such as roads, power and drainage, and addressing inefficiencies within the statutory bodies responsible for it.

Ian Wright, Founder and CEO, Disruptive Innovators Network

Will this be the year we see the first AI board member?

It’s an interesting idea, one which I explored recently by asking AI to develop a business case and a strategy to build an AI board member. I have posted the 22 page report on my LinkedIn account if you want to read what it came up with. What I found interesting was less the concept of whether we should or could build an AI board member but the questions to ask of it that I’d never have thought of if I hadn’t run the experiment.

On a human level will this be the year of the first housing provider to appoint a chief AI officer? Someone to take the lead and manage the organisations full adoption and scaling of AI?

Finally, will someone pick up the genius idea of Louis Timpany, founder of Fix Radio, and set up social housing’s own radio station? Who would the sector wake up to as the equivalent of the Bald Builders Breakfast or dive deep into the world of all things plaster? Who wouldn’t want to drive home to the sounds of the housing solicitor? The possibilities are endless!

“Technology will help us deliver better homes and experiences, but governance and culture will ensure we do it the right way”

Hassan Bahrani, Thirteen Group

Fuad Mahamed, Founder and Chief Executive of refugee and migrant housing provider ACH

The year ahead is likely to be a challenging one for the refugee and asylum seeker housing sector. The policy and public discourse context remain difficult, with limited indication of a shift away from deterrence-led approaches towards long-term, sustainable accommodation solutions. Persistent negative media narratives continue to shape public debate, influencing both policy direction and local delivery. While the use of hotel accommodation for those in the asylum system is expected to reduce, this is unlikely to ease overall system pressures. Increased dispersal into the private rented sector will place greater regulatory and operational demands on landlords and local authorities, alongside heightened scrutiny of accommodation standards within an already constrained market.

At the same time, the risk of street homelessness is expected to increase as pressure intensifies on councils and voluntary sector provision. The reduction of the move-on period will significantly limit the time available for people granted status to settle. Looking ahead to 2026, structural challenges in the housing system are expected to deepen. The ongoing shortage of genuinely affordable homes, combined with the widening gap between Local Housing Allowance rates and market rents, will make independent living increasingly difficult, particularly for families and younger refugees.

Sponsored by

The pressure on social landlords to perform well is intense. Scrutinised by the regulator, government, the ombudsman, campaign groups, lenders and above all their own residents, organisations must step up to the challenge. But what if they can’t get into people’s homes to complete the necessary work?

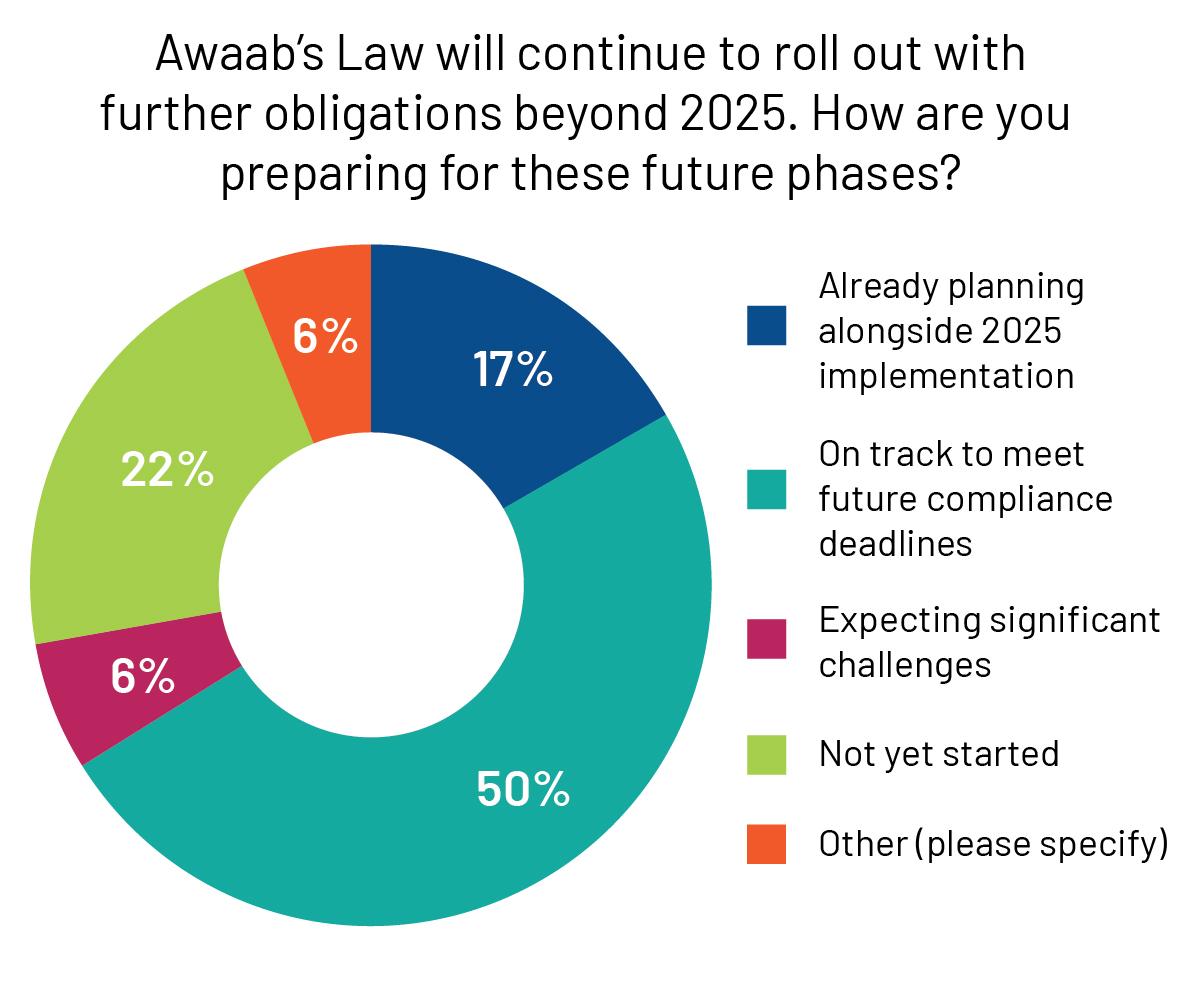

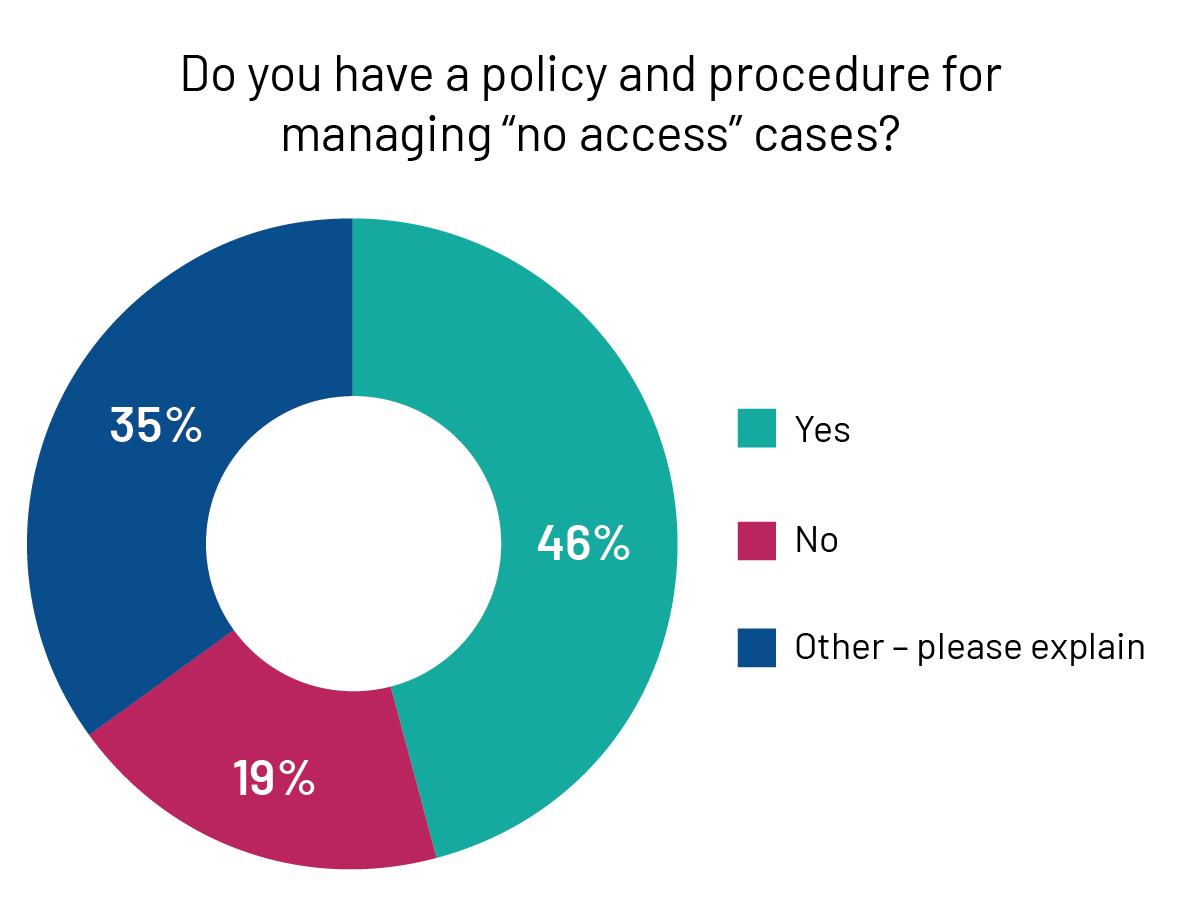

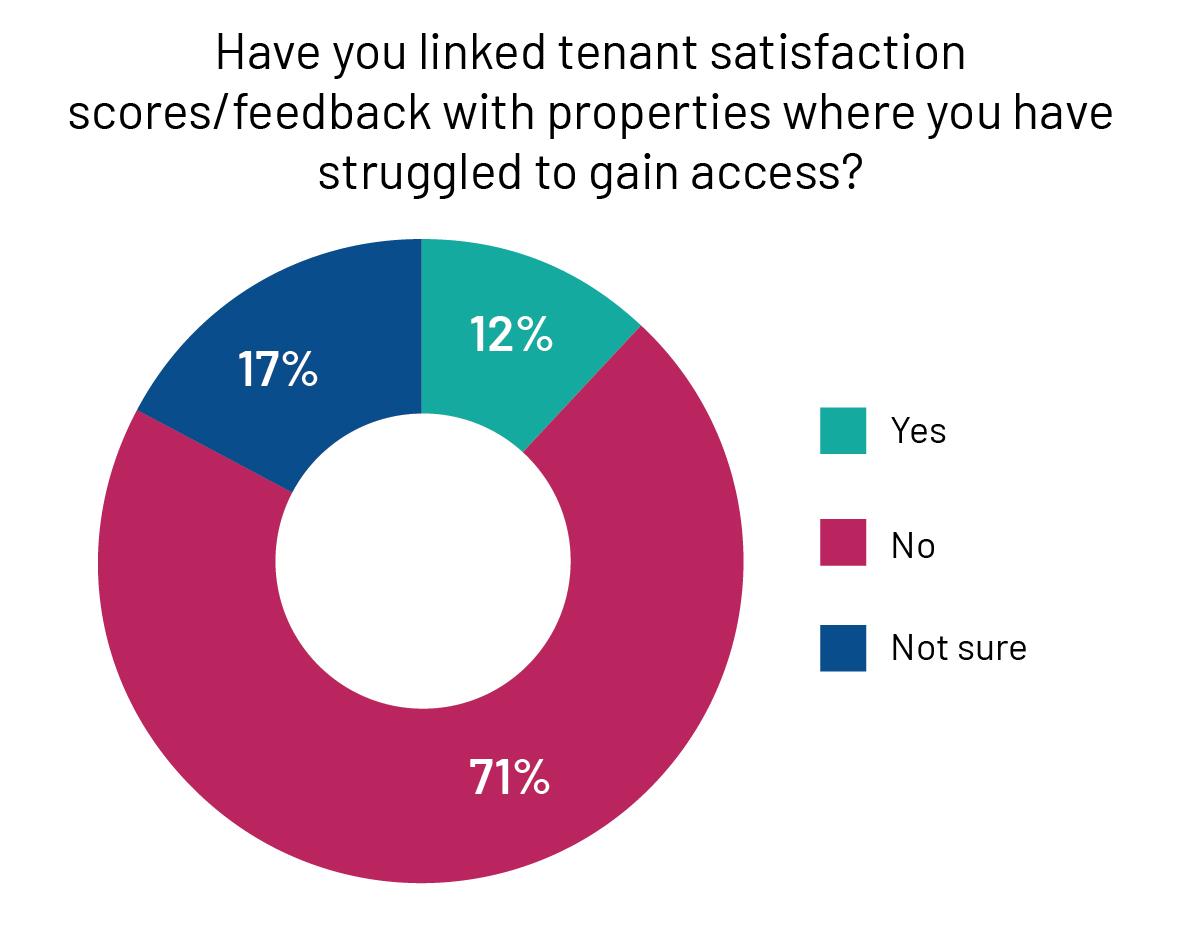

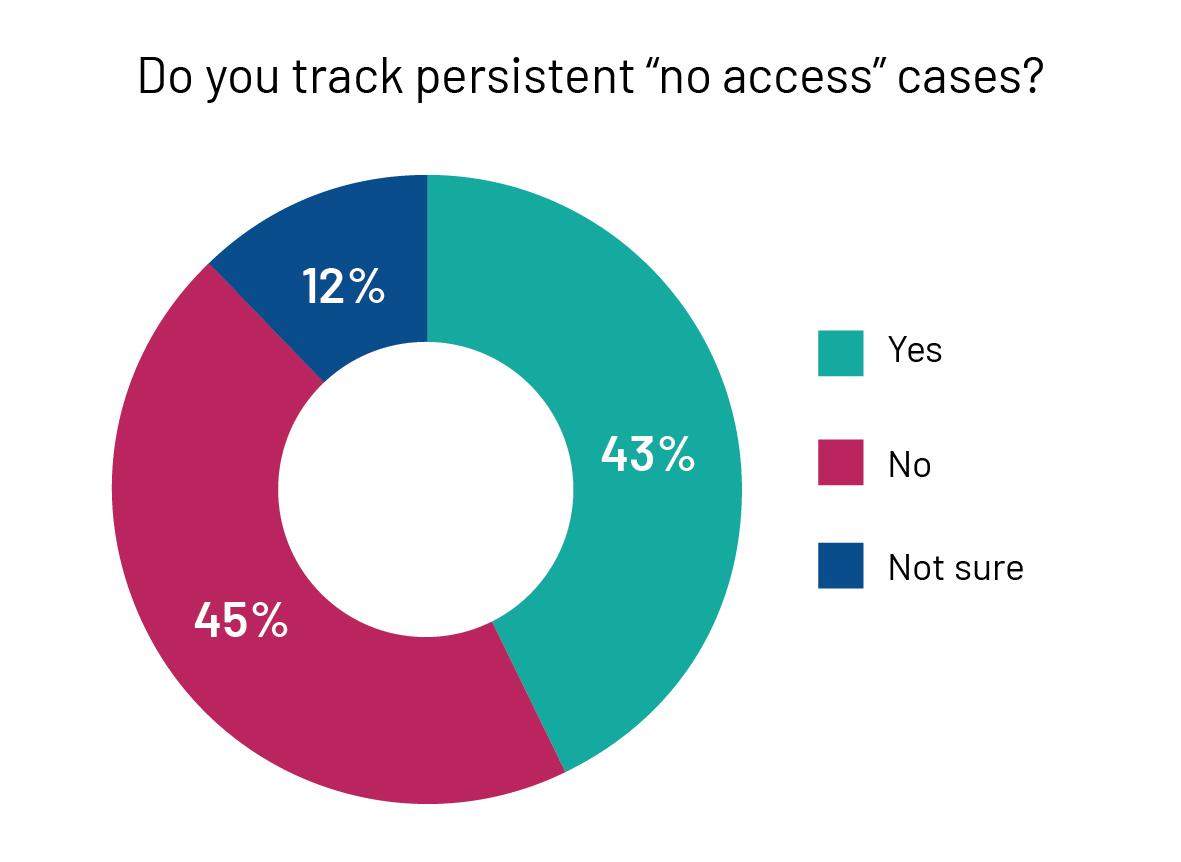

In this special edition we highlight recent research by HQN, commissioned by five leading housing bodies*. They wanted to know how social landlords are faring with gaining access to residents’ homes and how they are preparing for Awaab’s Law – which, of course, requires access as part of the task.

Our report Opening the Door: Changes to support necessary access to tenants’ homes finds landlords taking a range of actions to increase the likelihood that tenants will allow access when needed. In many cases it amounts to an imaginative rethink about what works.

Our other report, Preparing for Awaab’s Law: Progress by housing providers, took a snapshot from August to October last year of landlords’ preparations for the 27 October first phase implementation date. Again we found changed attitudes and, for many, new approaches to try to ensure

full compliance.

Here we summarise our findings, with the emphasis on good practice. We also showcase two case studies from the reports that offer more on the nitty gritty of how organisations are changing their systems and practices.

On a personal note, this is my final issue of Evidence as editor. After 13 years of bringing the latest housing research from the UK and around the world to our readers I’ll be passing on the baton for the next issue in April. Qualitative research in particular tries to reach the ‘why’ of events, offering valuable insights into the way people think. The quantitative side can pick up on trends, problems and change over time. We’ve tried to bring you a selection of each that should help inform decision making. It’s been an ever-fascinating journey for me and I hope you’ll continue to catch up on research in future editions.

Janis Bright Editor, Evidence

*National Federation of ALMOs (NFA), Councils with ALMOs Group (CWAG), Local Government Association (LGA), Chartered Institute of Housing (CIH) and Association of Retained Council Housing (ARCH).

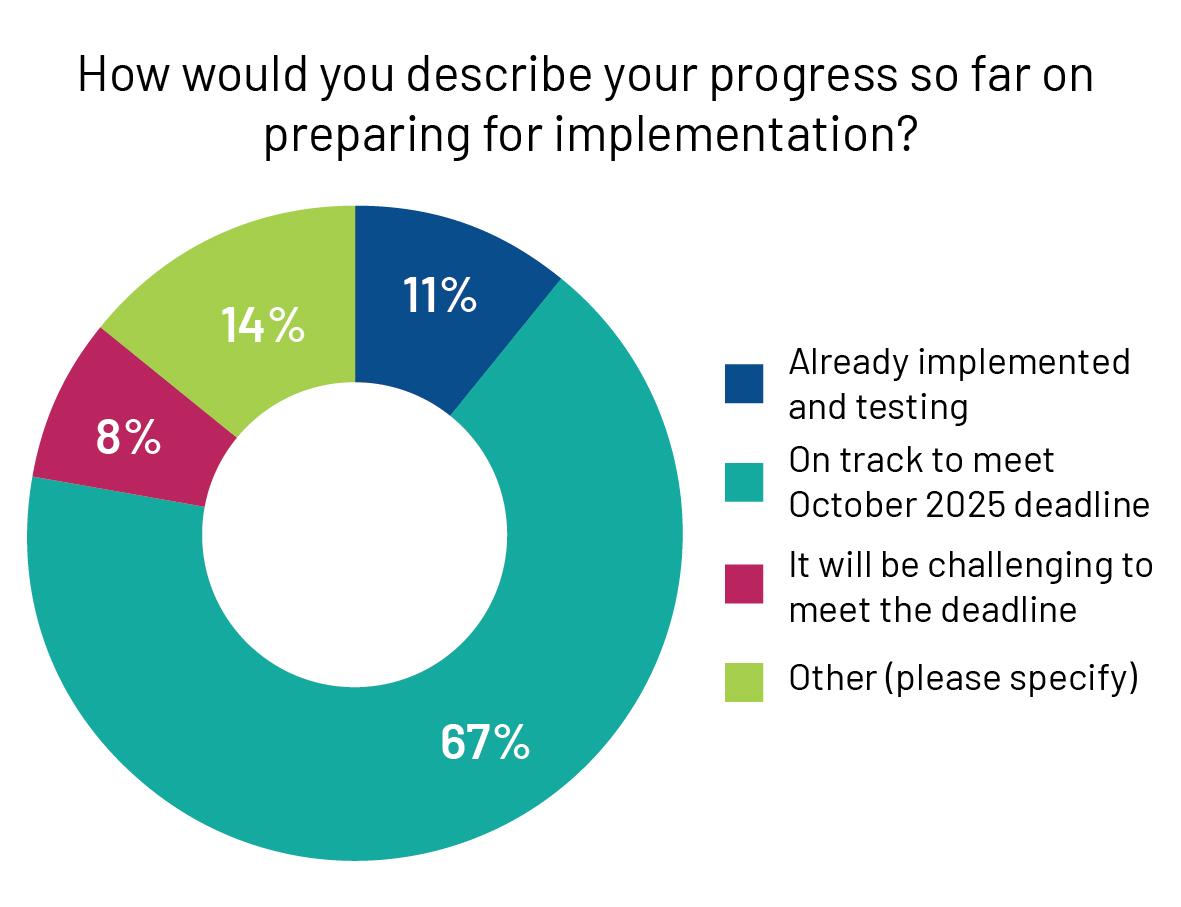

Awaab’s Law (Hazards in Social Housing (Prescribed Requirements) (England) Regulations 2025) came into effect on 27 October 2025, in the first of three phases. Our research report Preparing for Awaab’s Law: Progress by housing providers provides a snapshot of how landlords were preparing for the new law, just ahead of its implementation.

We found that most organisations have stepped up to meet the challenge and deadlines on Awaab’s Law for this first year of implementation, including revamped systems and response times. Some have been highly proactive on damp and mould and haven’t waited for national legislation and regulations to come into force. Many have involved residents in the planning and run awareness campaigns.

Two thirds of respondents in our survey were on track to

meet the 2025 deadline, while less than 10% reported that they would struggle to meet it. Problems remain, however. Among the difficulties are:

• Data systems, especially systems that connect across the organisation

• Resources are limited

• Staffing, particularly lack of qualified technical people such as surveyors

• Gaining access to survey or complete repairs (and see our linked report on this topic)

• Some aspects of the new law and guidance are unclear

• Achieving culture change across the organisation may be challenging

• Challenges around moving people out and finding suitable accommodation quickly.

On governance, we found organisations setting up specific reporting systems for Awaab’s Law compliance. This includes upward reporting and escalation to governing body level, complete with metrics and KPIs. Reporting to senior staff, governing bodies and in some cases tenant panels is designed to embed reporting into the existing structures of responsibility. Some organisations specifically mentioned integrating Awaab’s Law data reporting into existing systems on risk, damp and mould and health and safety.

Responding quickly and accurately to the first report of a potential hazard under Awaab’s Law was seen as crucial. Providers were upskilling call centre staff and encouraging residents to use photos/video to enable accurate assessment. In our research, around two thirds of tenants said they were willing to do this. Triage arrangements were in place at the majority of organisations.

Many organisations reported, however, that they were struggling to recruit enough trained specialists, such as building surveyors or contractors with HHSRS experience, who could establish the severity of cases.

Ensuring compliance across a local authority was seen as a major challenge. Most organisations had reviewed their policies and most were trying to bring together housing management, asset management and other teams for seamless working – something that’s long been both a goal and a challenge.

However, the complexities multiply with other council departments. All staff who might visit tenants need to be made aware of Awaab’s Law requirements, so they can help with spotting problems and potentially supporting housing staff to gain access to the homes of tenants with particular needs. These staff and local councillors also need to know where to report any issues and to do so promptly.

Measures taken specifically to meet the new Awaab’s Law duties included:

• Staff training – eg, on HHSRS and vulnerability

• Drawing in other departments and alerting their staff to the new requirements

• Toolbox talks

• Triage arrangements – using the existing call centre or a newly formed centralised team

• More use of photos and video

• Damp and mould first aid kits made available to clean small areas

• Summary proformas

• Summary emailed (where possible) or given to tenant whilst surveyor still on site

• Ability for surveyor to book appointments to complete the work while at the tenant’s home – allows mutually convenient appointments.

Our study suggests that providers are striving to bring about a culture of respect for residents and that many are investing in training to support an approach and behaviours that foster trust. We found a distinct shift toward an approach that’s based more in understanding individual residents’ needs and wishes. This was mainly around building relationships with people who are known to have a vulnerability or who have come to the provider’s attention

for a particular reason, such as complaints or not allowing access.

Most are using all their normal channels – tenant newsletters, leaflets, social media, rent accounts, etc – to alert and inform residents about Awaab’s Law. About two thirds of survey respondents had a full communications strategy. Some are taking the opportunity to do widespread consultation with residents, which can both inform them and seek their views. Some have involved resident scrutiny panels or resident groups to share progress and garner ideas. Some were engaging with tenants to develop plain English summaries of communications and advice.

Providers are moving toward a recognition that they must offer highly responsive systems that work for tenants, coupled with empathy and personal service. There’s a new willingness to seek views from residents who may not have previously reported problems, especially with DMC. Similarly, organisations were no longer assuming that problems were resolved if there was no further report: some are actively returning to ask tenants what’s happened since.

Technology was seen as crucial to delivering results, but also a key factor in problems with meeting the new demands. Many are struggling to integrate information technology (IT) systems across the whole organisation and to share appropriately with contractors. There are problems in keeping data on resident vulnerabilities up to date and appropriately shared. There were many calls for a dedicated IT system for reporting, tracking and monitoring both individual cases and the organisation’s overall compliance.

Quite a number of providers have made the link between Awaab’s Law compliance, stock condition and customer satisfaction for the longer term. Some are using the first year of implementation to embed new policies and practice, so that they will be better prepared for the next phases.

Some organisations noted the lack of clarity on aspects of the detail in the government’s draft guidance, particularly over the maximum timeframes, the meaning of certain terms and any exemptions. Two terms in particular with interpretable meaning were cited: ‘emergency’ versus ‘significant’ and ‘all best endeavours’. Participants felt that this added to an already complex and sometimes unclear legal framework.

There’s considerable uncertainty simply because the legislation is new and untested. Organisations had many concerns about a potential rise in disrepair cases and ‘claims farming’. However, some had taken positive action to deal with complaints and disrepair claims quickly and thoroughly, with new protocols and timescales1. Data recording was seen as crucial.

There was no hint of outdated attitudes around residents and ‘lifestyle’ in relation to DMC. Instead there’s a widespread concern that residents’ circumstances can exacerbate complex problems. There’s sensitivity around this, of course, but especially with damp, mould and condensation issues, providers report that people are suffering through the cost-of-living crisis, cannot afford to

turn their heating on or want to keep the windows shut to conserve warmth. Others are having to live in overcrowded conditions above the design tolerance of the building, that can worsen humidity.