SOFT POWER

The allure of understated elegance

D-MARIN MARSA AL ARAB MARINA

Where the World’s Finest Yachts Dock

in Dubai

Set at the tip of Dubai’s exclusive golden peninsula, D-Marin Marsa Al Arab Marina is the city’s definitive superyacht address, offering 82 exclusive berths for yachts up to 61 metres, framed by the iconic Jumeirah Burj Al Arab and Marsa Al Arab.

Here, the superyacht experience extends far beyond the dock. More than a marina, it is an ultra-luxury lifestyle destination, offering exclusive member privileges and access to beach, pool, leisure, wellness, and dining experiences across Jumeirah’s beachfront hotel portfolio in Dubai.

FEATURES

Thirty Four Female Intuition

Imogen Poots on seeing through fakery, attitude problems, rites of passage, and acting in Kristen Stewart’s directorial debut.

Forty Grasse Roots

The story of Chanel’s perfumes stretches to a century, and the fragrant fields of Grasse on the Côte d’Azur are where each chapter begins.

Forty Six The Conversation

Over home-cooked chicken cacciatore, Francis Ford Coppola reflects on marriage, family, 1960s London and returning to his roots at his palazzo hotel.

In the heart of the Dubai Desert Conservation Reserve, Al Maha rises quietly from the dunes — a retreat shaped by space, silence and connection to the land. Tented villas, private pools and instinctive service create a sense of ease rather than excess. Days unfold in harmony with nature, from dawn light on the sand to evenings beneath star-filled skies. This is quiet luxury, guided by heritage, where the desert leads and everything else follows.

EXPLORE THE DESTINATION AT AL-MAHA.COM

REGULARS

Sixteen

RADAR

Maybach hits the high seas with a pioneering membership club and brand new superyacht.

Eighteen

OBJETCS OF DESIRE

The latest luxury items we’re currently coveting.

Twenty

ART & DESIGN

An original, self-taught talent, renowned designer Tom Dixon on the benefit of being your own brand.

Twenty Four

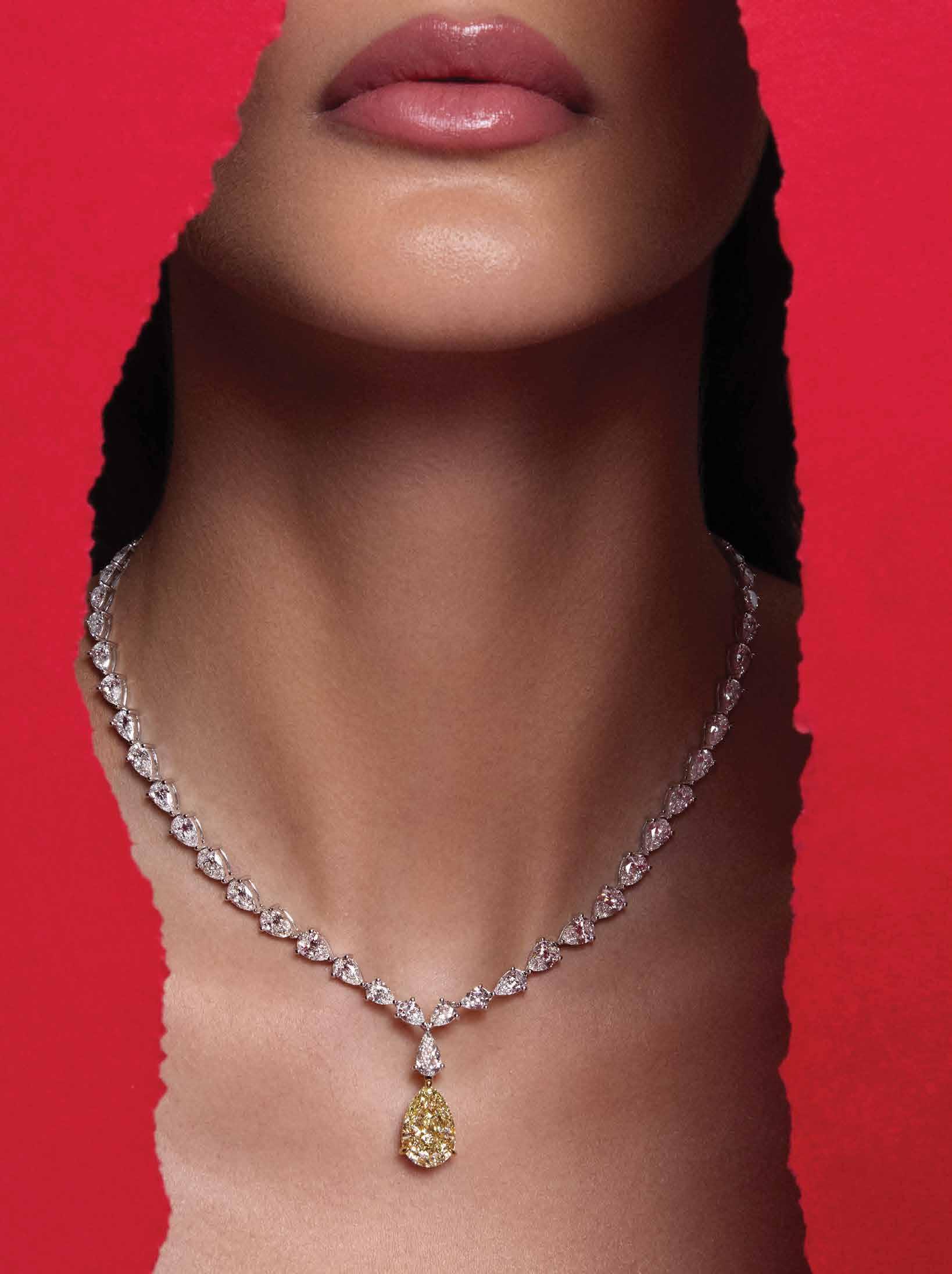

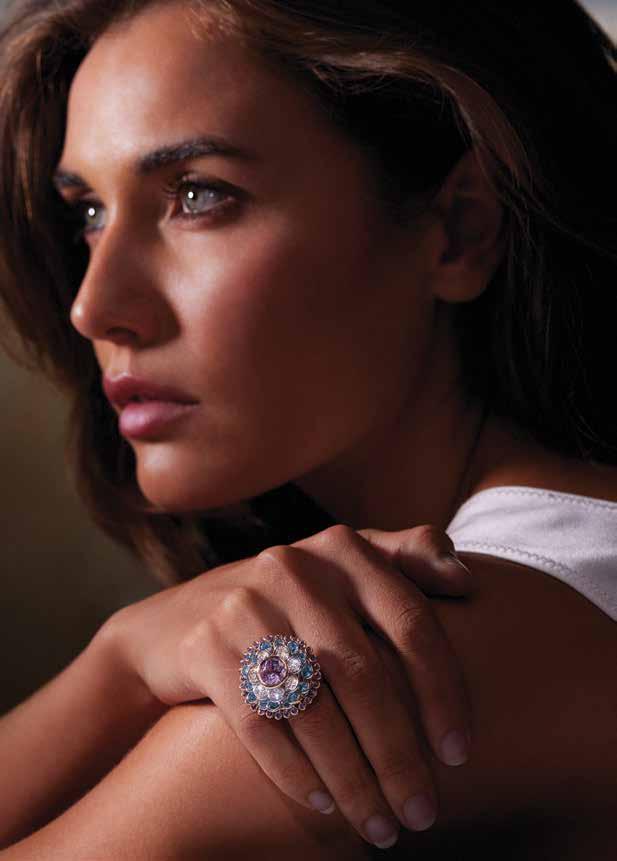

JEWELLERY

How an unsettled debt set Ming Lampson on course to craft her unique jewels.

Twenty Eight

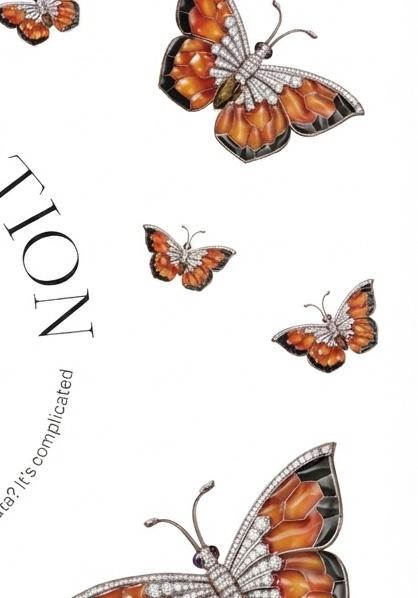

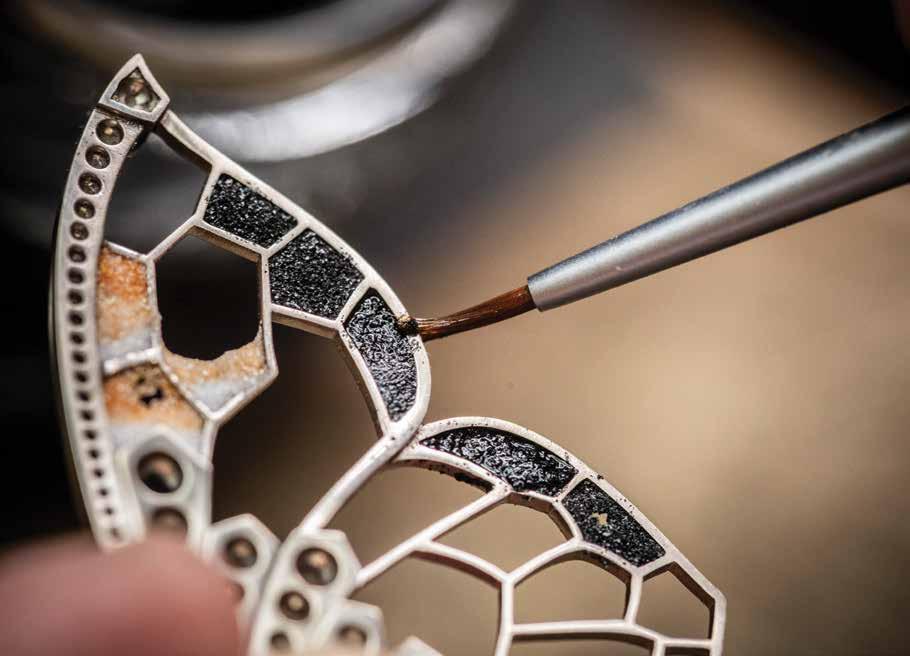

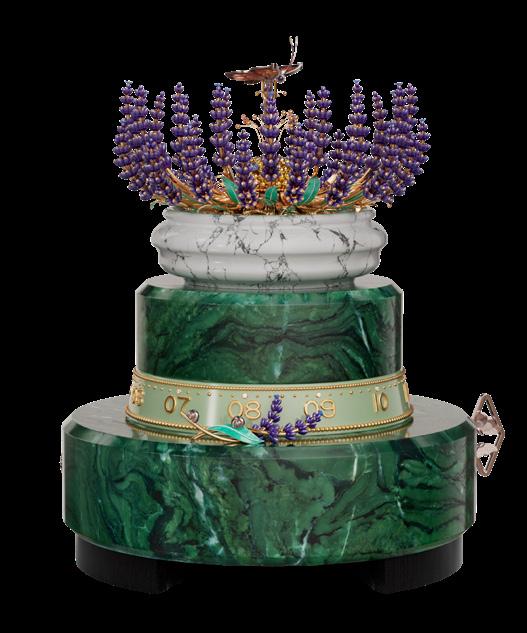

TIMEPIECES

How has Van Cleef & Arpels created its exquisite collection of automata? It’s complicated.

Fifty Four

MOTORING

Limited to only five, fully customisable examples worldwide, the TALOS XXT is a race-inspired grand tourer with power to burn.

Fifty Eight

GASTRONOMY

John Williams MBE on how he brought the glamour – and Michelin stars –back to The Ritz restaurant.

Sixty Two

TRAVEL

Liverpool has long embraced visitors like one of its own. We discover a city with much to be proud of. Over in the City of Light, The Peninsula Paris proves to be a modern legend.

Sixty Eight

WHAT I KNOW NOW

Hublot CEO Julien Tornare on the knowledge he has gleaned from life.

EDITORIAL

Editor-in-Chief & Co-owner

John Thatcher john@hotmedia.me

COMMERCIAL

Managing Director & Co-owner

Victoria Thatcher victoria@hotmedia.me

PRODUCTION

Digital

Manager Muthu Kumar muthu@hotmedia.me

Start with 50,000 Welcome Points*, $250 Welcome Credit, and $300 Annual Travel Credit.

WELCOME ONBOARD

Being named the World’s Leading FBO Brand for the fifth consecutive year is both an honour and a moment for reflection. As we celebrate this recognition at the 32nd World Travel Awards, it is impossible not to think of the journeys that brought us here – yours, our customers’, and the countless experiences shared across our global network.

2025 also marked Jetex’s 20th anniversary, a milestone made meaningful by your trust, loyalty, and curiosity. From expanding our private terminal networks to enhancing digital capabilities and reimagining our service offerings, every investment we make is guided by a single goal: to ensure that your journey is seamless, effortless, and uniquely yours.

Excellence in private aviation is not measured by awards alone, but by the moments of comfort, care, and precision that make travel feel effortless. Each flight you take with Jetex inspires us to refine the details, innovate, and raise the bar for what luxury travel can be.

As we look ahead, our commitment remains unwavering: to create travel experiences that are not only world-class but also deeply personal, combining safety, efficiency, and thoughtful hospitality at every step.

As always, thank you for choosing Jetex for your global private jet travels. All of us look forward to taking you higher in utmost comfort and luxury – and with complete peace of mind.

Adel Mardini Founder & Chief Executive Officer

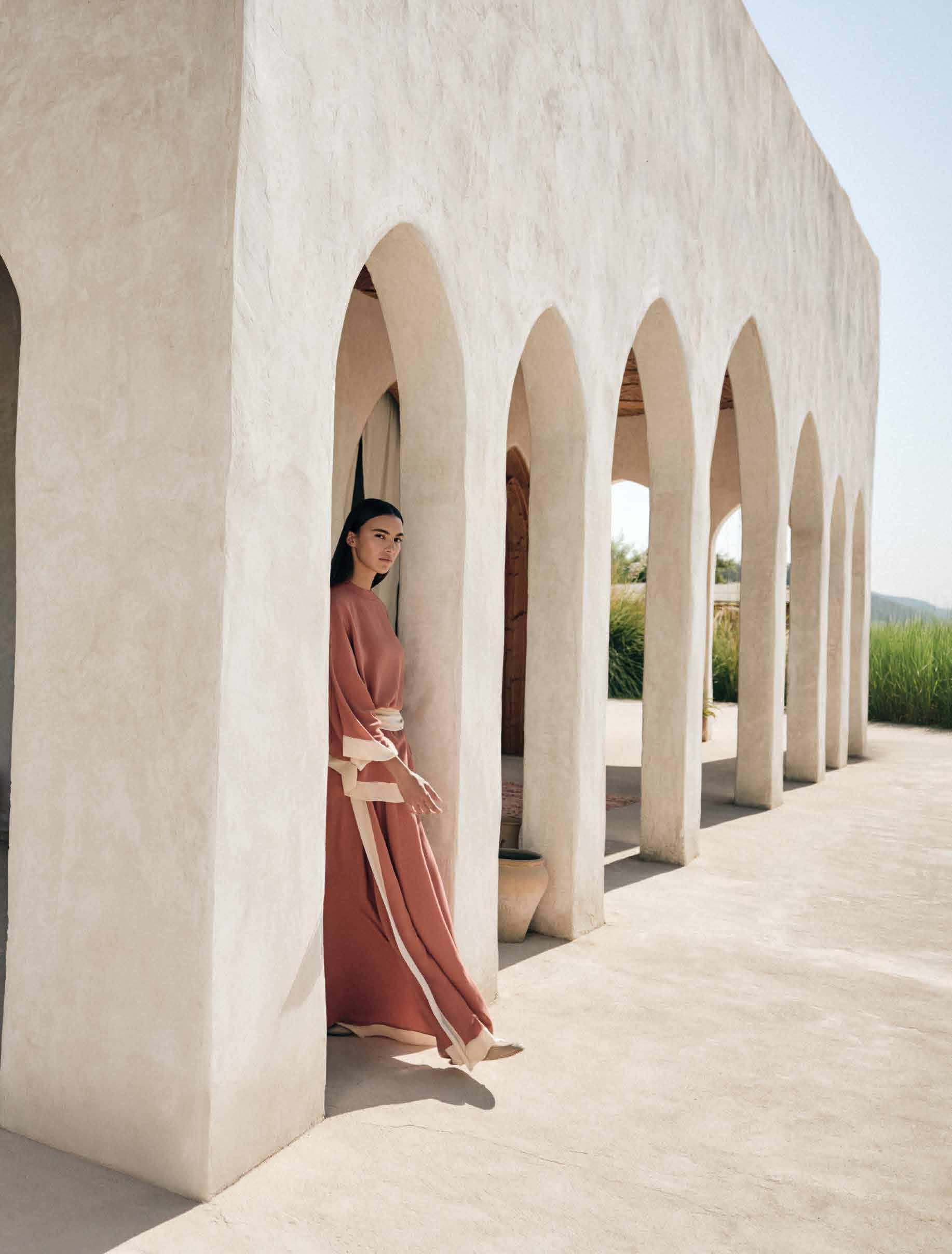

Cover: Amira al Zuhair wears Patrica shirt and Ronny embroidered coat from Loro Piana Ramadan 2026 Capsule Collection. Shot by Amina Zaher

JETEX TAKES OFF IN MILAN

Jetex Milan will open at the city’s Linate Prime Airport

Jetex is set to elevate the travel experience in Milan with the opening of Jetex Milan at Linate Prime Airport early this year. Known for its excellence in business jet and helicopter services, Linate Prime is the ideal stage for Jetex to strengthen Milan’s position as Europe’s premier business aviation hub.

Less than seven kilometres from the city centre Jetex Milan will offer travellers effortless access to Milan’s cultural and commercial heartbeat. The terminal promises luxurious lounges, award-winning hospitality and carefully designed facilities, ensuring every journey is seamless and personalised – a perfect complement to one of Europe’s most dynamic cities.

“We are proud to add Milan to the Jetex list of destinations. Milan is a key business and leisure destination in Europe, and we are entering the destination at a historical moment in anticipation of the traffic peak foreseen during the Milan-Cortina 2026 Olympics,” said Adel Mardini, Founder & CEO of Jetex.

International events like the F1 Grand Prix and Milan Fashion Week consistently draw record aviation traffic, with peaks exceeding 300 daily movements.

“Thanks to its growing international prominence, Milan has become one of the leading destinations for business aviation, as confirmed by recent traffic data at the Milano Prime facilities, with over 27,600 business aviation movements recorded up to September 2025. The upcoming Linate Prime terminal expansion, scheduled ahead of the 2026 Winter Olympic Games, will add approximately 2,400 square metres of new lounges and passenger service areas, further enhancing comfort and operational efficiency. We are therefore delighted with Jetex’s decision to expand its presence in Milan, joining other prestigious companies that have chosen to operate permanently from Milano Prime Airports,” commented Chiara Dorigotti, CEO of SEA Prime. Sustainability is also at the forefront. Following Linate’s 2023 milestone as Italy’s first SAF business aviation airport, Jetex Milan will extend its sustainable aviation fuel network, offering private jet travellers a greener, more conscious way to fly without compromising the luxury, efficiency, or style that defines the Jetex experience.

Ages 8 - 16 Coastal

Where adventure meets education

At the turn of the twentieth century, many of the most elegant boats that sailed the seas were powered by Maybach engines. Now the Maybach brand is set to sail again, this time as the driving force behind a pioneering superyacht membership club. When it launches in 2029, the Maybach Ocean Club will grant its members exclusive use, for four weeks per year, of one of only thirty suites onboard a brand-new, service-focused superyacht designed in close collaboration with the Mercedes-Benz Design Team. “Yachts have always been the ultimate expression of prestige, power and luxury,” says Gorden Wagener, Chief Design Officer, Mercedes-Benz AG. “Designing a superyacht that stands out as a true iconic piece of design was our intention. The result is something truly majestic that carries the signature of the Mercedes-Maybach brand into every detail.” maybach-ocean-club.com

Credit: Dölker + Voges Design

objects of desire

Set the tone as a true tastemaker with these coveted items

When, all the way back in 1879, Thomas Burberry developed gabardine, a weather-resistant fabric, to help shield people from Britain’s persistent rain, it’s fair to assume he wouldn’t have expected that fabric to still be at the forefront of the brand’s outerwear two centuries on –

most famously in the form of the trench coat. This capsule collection honours gabardine with a mix of products crafted from – or detailed with – the timeless fabric, alongside complementary knitwear that reinforces Burberry’s connection to the great outdoors.

BURBERRY GABARDINE CAPSULE

2004’s launch of the bold, distinctive, and sophisticated Cubitus – twentyfive years on from Patek’s last new collection – was obviously a big deal in the watch world and, at 45mm, a big watch too. The latest additions are sized smaller (40mm) and aimed at gracing the wrists of both males and females. They include this rose gold model, its dial coloured a sunlit brown and visually enhanced by the contrast between vertical satin and polished finishes, a pattern repeated on the calibre’s central 21k gold rotor.

PATEK PHILIPPE

CUBITUS REF. 7128

A coveted bag that’s designed to be carried through from day to night (it has a detachable shoulder strap), this soft, elongated version of the Extra Bag is constructed from a mixture of materials that produce its tactile suppleness: satin, woven leather, soft fine-grained leather,

smooth butter calf and a handcrafted fabric. Its decorative hardware is gold in tone, including the brand’s Ghiera charm, a subtle but distinctive touch. Available in two sizes, it also comes in a choice of four colours, including a rich dark chocolate liquorice.

LORO PIANA EXTRA SOFTY BAG

RM SOTHEBY’S

2021 MERCEDES-AMG GT BLACK SERIES PROJECT ONE EDITION

Limited to 40 examples globally when it was issued, the Mercedes-AMG GT Black Series Project One Edition was only offered to a select group of buyers – those who had reserved a Mercedes-AMG One hypercar. Powered by a 730-hp, flatplane crank V8 and fitted with elite track

hardware, including lightweight carbon body panels, the Project One took design cues from Mercedes-AMG’s Formula 1 cars, with a paint scheme that fades from silver to black. Highly collectable, it will be auctioned on February 27, when it’s expected to achieve $500-600k.

“I loved the idea of dressing the way you garden,” says Carolina Herrera’s creative director, Wes Gordon, who likely hasn’t seen what my gardener has done to my bougainvillea, but I digress.

“There’s instinct, intention, and a kind of freedom in the way you bring things

together.” The botanical references are multiple and rewarding: soft dresses, flower prints and leaf embroideries, and colours that range from summer’s vibrant lawn greens, rosewater pink and cranberry into autumn’s deeper tones.

CAROLINA HERRERA PRE-FALL 2026

This year marks 130 years since Georges Vuitton, son of founder Louis, created the brand’s monogram, now arguably the most recognisable luxury symbol in the world. As you’d expect, the brand has gone big on celebrations, producing three capsule

collections, the pick of which, Time Trunk, takes design inspiration from the iconic hard-sided trunks. The look of this Alma GM was achieved by photographing a trunk from all angles and reproducing its look on canvas, via high-definition printing.

LOUIS VUITTON TIME TRUNK

Having first collaborated in 2020, Hublot and Yohji Yamamoto head back to black for what is the fourth time, merging their skills for a Classic Fusion All Black Camo that’s limited to 300 pieces. “For Yohji Yamamoto, black reveals what truly matters; it purifies

form, letting silhouette and texture speak. At Hublot, we treat black as a living material, sculpted, layered, folded, where each surface interacts differently with light,” said Hublot CEO Julien Tornare. A design highlight is the dial’s monochrome camouflage pattern.

HUBLOT X YOHJI YAMAMOTO CLASSIC FUSION ALL BLACK CAMO

An original, self-taught talent, renowned designer Tom Dixon on the benefit of being your own brand

JOHN THATCHER

WORDS:

It’s fair to say that Tom Dixon’s career path, which in 2024 included a diversion via Buckingham Palace to collect a CBE from King Charles III for his services to design, has been anything but conventional. He’d initially planned to make it as a musician, but a lucky break (to his arm) meant he was unable to play his beloved bass guitar for an extended period. Instead, Dixon used his recovery time to teach himself to weld, going on to use his skills to create chairs from materials discarded around London while working his regular day job as a nightclub promoter. He’s since turned his hand to everything from hotels to teapots, but it was one of those improvised chairs that arguably launched his career.

The prototype of Dixon’s sculptural S-Chair fused hand-welded steel frames with recycled rubber, punk in character. It caught the eye of Italian giant Cappellini, for whom Dixon then collaborated with to refine the design into an object that sits somewhere between furniture, industrial design and art, and certainly among the late-20th-century chairs that achieved instant classic status. It’s now part of permanent collections at MoMA in New York and London’s V&A. Dixon is rightly proud of the S-Chair; less so his very first design. “Aged 15 I used to make hash pipes in my pottery class and sell them to my classmates. I was proud of that at the time – possibly less now.” He has previously discussed the

benefits of being self-taught, likening it to being in a band. You learn your own instruments, write your own songs, book your own gigs and promote them, thereby creating and running your own little business. “I was able to shape a personal aesthetic and attitude mainly based on my experiences in music, love of sculpture and interest in craft and industrial processes before I discovered the wonderful world of design,” says Dixon. “I was interested in all aspects involved in the creation and journey from idea to customer before I even thought of myself as a designer.”

Was it a challenge to define his aesthetic? “Not at all – I didn't even consider this as a thing! I just made things until a style emerged. It was never a conscious choice. I have also

Previous page: Tom Dixon

These pages, from left to right: Tom Dixon SS26

gone through a series of aesthetics and come out on the other side.

Now, as I have a specific aesthetic that people recognise associated with the brand, it actually gets harder to redefine my aesthetic.”

His eponymous brand launched in 2002 and specialises in furniture, lighting and accessories. It has hubs in London, New York and Shanghai and distribution partners elsewhere across the globe, including the Middle East. As well as the S-Chair, Dixon has created a catalogue of instantly recognisable designs, including Melt, Beat and Fat. “I don’t do favourites. I love the diversity of products and the fact that they all need different knowledge and skills to get the best out of them.

“I think here is the advantage of having your own brand – we surround

our objects with other products from the same family with a complimentary attitude, and we are able to control the aesthetics of the communication and some of the places where our stuff is shown. It’s important to create a whole world in keeping with your ideas.”

If not a favourite, is there a design that best encapsulates his design ethos? “The JACK lamp that we are just re-issuing for SS26, but this time upgraded with a rechargeable battery. It’s my first industrially self-produced object and has an instantly recognisable shape. It’s also multifunctional, meaning you can sit on it, stack it and, of course, it illuminates.”

Having lit up the design world for several decades, Dixon remains excited. “We are in an interesting time in design with the miniaturisation and

digitalisation and robotisation of the manufacturing industry, and with the advent of AI to speed up ideation, prototyping and communication.” Is he equally enthused by the use of new materials in design? “Honestly, most of the fabulous nanomaterials and sustainable materials are yet to get to the stage of being comparable in price and functionality to existing materials.

I get excited by timeless materials that can be used in a new way.”

Which brings us back to how the S-Chair came to be and to what Dixon considers to be his greatest achievement in a career full of them.

“I’ve taught a lot of people how to weld and possibly demonstrated to them that they can absolutely make their own businesses and output their own ideas, so that’s nice.”

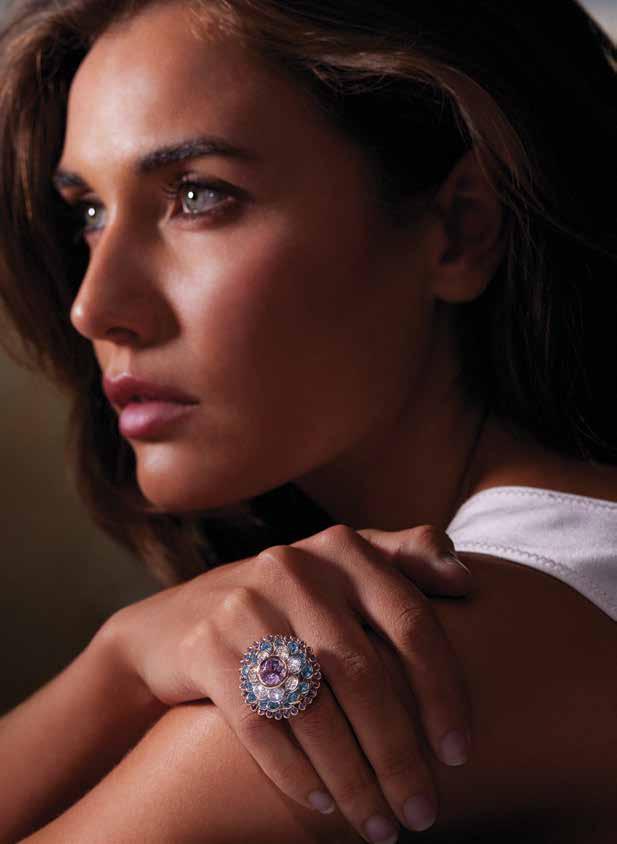

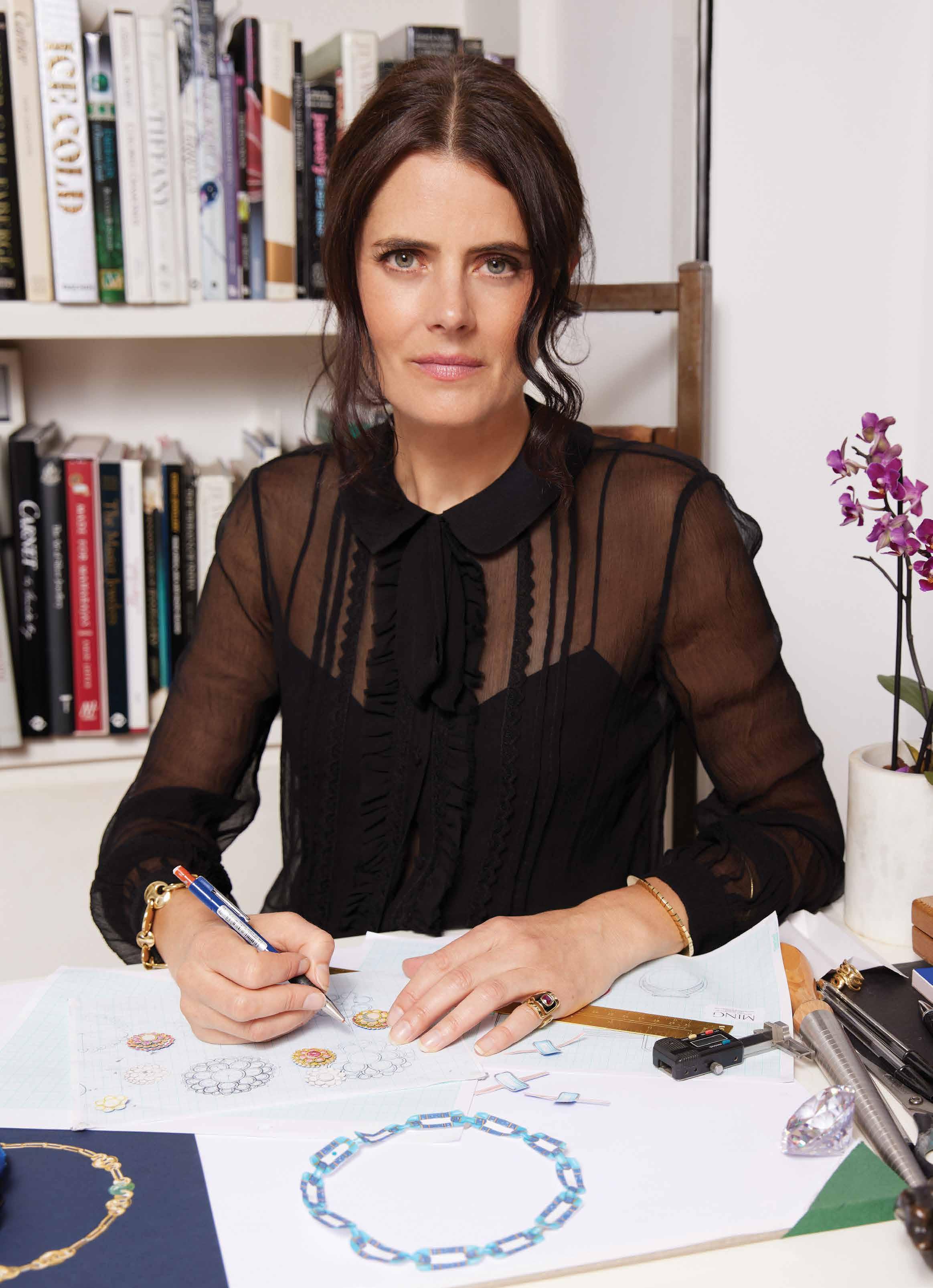

MING THE MASTERFUL

How an unsettled debt set Ming Lampson on course to craft her unique jewels

WORDS: JOHN THATCHER

TThe true worth of something isn’t always apparent. In the case of jeweller Ming Lampson, it was a bag of gemstone beads, given to her by a friend in lieu of money owed that, as a 17-year-old, was very much needed. However, Lampson would not lose out financially for long, weaving those beads into charming necklaces that she sold from a market stall in Galway, Ireland. A quarter of a century on, Lampson designs, makes and sells bold, beautiful and often one-of-a-kind pieces from her atelier in London’s Notting Hill and is widely celebrated as one of the industry’s finest contemporary jewellers.

“I have always loved bold, striking jewels that make you want to look twice. Over the years I have become more selective about the gemstones I use – I really only want to use really special beautiful stones in my work,” says Lampson. “I have learnt that if the gemstone is fantastic quality, the jewel it is in will always look amazing.”

While that original bag of gemstones ignited a passion for stones and jewellery, it was in India where that love fully blossomed. “I travelled to India initially in search of gemstone beads, but as soon as I arrived in Jaipur I realised that beads were only a tiny part of an enormous, fascinating world of gems and jewellery. In Jaipur I completely fell in love with, and began to understand, gemstones: what rough looks like; how crystal shapes lend themselves to being cut in certain ways; how cutting brings out colour and sparkle and creates desire; the nuances of colour and the importance of hardness. At that time, Jaipur was really the centre of the coloured stone trade, with more than three thousand cutters in the city.

“I lived in Jaipur for over two years from the age of nineteen. My youth, enthusiasm and single-minded determination to learn as much as I could enabled me to meet many dealers. I would walk into any shop or office to ask questions about gems and request to see rough stones or cutting workshops.

Dealers in the trade love their stones and most are keen to share their passion – I was very lucky that they opened their doors to me and shared their knowledge, allowing me to grade stones, letting me look through huge piles of rough and showing me such a wide variety of different material. I have a natural ability to detect and remember nuances of colour, and once they could see that, they put me to work. Later, I would travel to gem fairs and meet dealers and make connections – I was there to see as many stones as possible and talk to as many people in the trade as possible. The huge variety of special gemstones in my work is due to the relationships I have built with my network of gemstone dealers over the last thirty years.”

Lampson’s time in India wasn’t only about making contacts; it was also where she learnt to make jewellery, apprenticed to a traditional goldsmith who helped her explore the many ways in which metal can be worked. “The most important lesson I learnt is that gold and gemstones are treasures to be revered and cherished.”

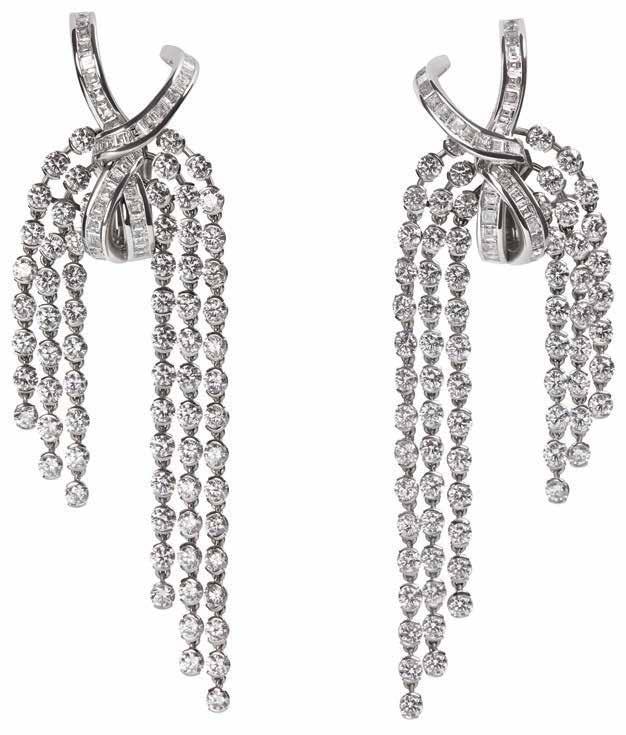

Previous page: Ming Lampson This page, from top to bottom: Double Knot earrings; Ruby Petal ring; Ruby Knot necklace; Cascading Knot earrings

Opposite page, from top to bottom: Dahlia ring; Westside necklace; Aquamarine West ring; Firethorn earrings; Opal Masquerade earrings; Skateboard ring; Snuff ring

Lampson’s clients certainly treasure the bespoke creations they commission from her. “I would say that all my commissions are memorable because I spend so much time thinking about the person for whom I am creating the jewel,” says Lampson when I ask if there’s a standout commission from the past twenty-five years. “Trying to work out how I capture something of the essence of them in the work means that I am constantly refining ideas to make the jewel unusual and unique but still simple and wearable. A recent commission was to create a ring inspired by the sea that surrounds the Aeolian Islands, where my client was married. Another ring was inspired by the flights of swallows. A commission doesn’t need a story; sometimes the story is the person.”

It’s for Lampson’s collection pieces that storytelling plays a more prominent role. “It’s a big part of my design process. I love researching themes and concepts and, from my studies, distilling down the essence of an idea and illustrating it through metal and gemstones. In the final jewel, the story is actually not so important, as the piece becomes its own sculpture separate from the inspiration, but during my design process it is vital. I not only love the research, but I believe it helps me to create more unique and interesting jewellery.”

Lampson’s latest collection, 25, was created to celebrate the anniversary of her eponymous brand and features twenty-five one-of-akind designs. It’s also a celebration of her artistic innovation and where she lives and works in West London. “The different communities and how they connect to each other and the wider world. Jewellery brings people together; it also binds us to a particular time or place,” she says.

“In wanting to honour Notting Hill and West London, I couldn’t not reference the incredible gardens that are found here: the hidden communal gardens and the huge parks. The Dahlia Ring appears to be a simple flower ring, but the petals, which are individual stones, are loose and designed to tremble. To make each of these gems able to move but not fall out of place, and to be sure they didn’t tip to the side or show the connectors behind, was a challenge. It took a lot of attempts to get the size of

the wires right and have the structure behind completely hidden. When you first look at the ring it appears so simple – it is only when you turn it over that the engineering becomes apparent. The Firethorn earrings are similar, in that at first glance they are large hoops of fire opal. It is only on closer inspection that you can see the drama comes from having such bright stones held with hardly any metal showing, so that all you see is the vibrant orange of the material.

“I will fall in love with a gemstone because there is something extraordinary or rare about it that will inspire a design. It is not always instantaneous. Often, I will buy the stone and have it in my safe or on my desk for a couple of years before making it into a jewel. Other times I am wanting to convey something through a design and will look for the gemstone that fits the idea.”

‘ I AM CONSTANTLY REFINING IDEAS TO MAKE THE JEWEL UNUSUAL AND UNIQUE BUT STILL SIMPLE AND WEARABLE’

The ideas of her clients have changed over time. “Twenty-five years ago, bespoke requests were all about diamonds in platinum, and then taste shifted to gold and diamonds. Now my clients are much more interested in coloured stones and are far more adventurous with the designs they are willing to wear. Part of this is changing fashions, and part of it is my confidence to design and create more unusual jewels. At present, we are in a moment where people are interested in having a one-of-a-kind jewel, made with care and integrity by master craftspeople, that no one else will own.”

It proved fortunate that Ming's friend didn’t have enough cash to settle her debt the normal way, as there’s certainly no one else quite like Lampson when it comes to crafting the unique.

P OETRY IN MOTIO N

WORDS: JAMES GURNEY

AAs with everything at Van Cleef & Arpels, it starts with a story. The early 2000s saw a boom in creative watchmaking with all sorts of new and reimagined complications and display systems being thrown together, resulting all too often in the announcement of the ‘world’s first quadruple axis, retrograde carillon’, or suchlike. In 2006, Van Cleef & Arpels took the opportunity to channel some of this energy into its universe to create something special. And so was born its series of Poetic Complications. These watches put modules such as retrograde indications, 24-hour rotating dials and minute repeater mechanisms to work, debuting timepieces that showed dancing lovers, shifting skies, celestial bodies and fluttering butterflies.

Almost inevitably, the development of these pieces crossed the line into automata making, at which point Van Cleef & Arpels began a collaboration with the master of that art, François Junod, a partnership that resulted in the incredible 2017 Fée Ondine, a table-top automaton in which a sleeping fairy emerges from a lily pad to dance as the leaves ripple around her. Since then, the ambition levels have risen, with the brand producing both wristwatch and table-top wonders, the latest of which is the Brassée de Lavande, a table-top automaton on the same scale as the Fée Ondine.

Here the centrepiece is a lavender bouquet that opens up to reveal a butterfly with fluttering wings made from orange plique-à-jour enamel set against diamonds and opaque black enamel that line the contours. The body is made of tiger’s eye with amethyst cabochon eyes and antennae tipped with diamonds, a richness of detail that’s followed through everything from the lacquered lavender buds to the carillon mechanism that’s linked to the automaton.

While Van Cleef’s technical horizons (whether alone or with Junod) have kept expanding, the storytelling remains the starting point as Rainer Bernard, head of the maison’s R&D, explains: “We love to start with a story and it can come from anywhere. Someone might tell me they saw a bird feeding its chicks, and that tiny moment could become the start of a new automaton. We think about the movements that would tell the story; only afterwards do we take care of the technique.”

Because Van Cleef & Arpels now integrates more and more of that engineering and manufacturing, it can follow that approach all the way through – the narrative leads and the mechanics follow.

“Take the watch with the butterflies flying above a garden [Lady Arpels Brise d’Été],” says Bernard. “We wanted them to hover naturally, with the flowers moving in the wind. With existing mechanisms, that was impossible with the [limited] energy available: the animation would start strong and fade. We had to invent a system to equalise the power throughout the

movement, but we would never have developed it if the story hadn’t demanded it: that forced the innovation.”

If that sounds like the standard watch development, what followed definitely wasn’t. Most watch development is carefully planned out, with parameters established and progress mapped out in advance – not so at Van Cleef & Arpels.

“Now that we master the entire process ourselves, we’re completely free,” says Bernard. “We’re not limited by partners who say, ‘No, that can’t be done.’ We can really do what we want and if the story calls for something impossible, we find a way to make it possible.”

Part of that process entails spending a long time in what Van Cleef & Arpels calls the “architectural phase”, the early part of the creative process when nothing is fixed. “It can be unnerving for outsiders because for months it looks like nothing’s happening,” says Bernard. “But during that time, we’re exploring possibilities, sketching, leaving room for systems that don’t even exist yet. Only when everyone – designers, craftsmen,

‘ IF THE STORY CALLS FOR SOMETHING IMPOSSIBLE, WE FIND A WAY TO MAKE IT POSSIBLE’

engineers – feels that the story and direction are right do we move forward.”

Add to that the different craft métiers that contribute to each piece, some of which are external, and the involvement of teams in Paris, Geneva and at the Mécanique d’Art workshop in Sainte-Croix, and isn’t there the risk of a misunderstanding? (Imagine if the jewellers decide to make the flowers in gold – that impacts on the mechanics underneath, as their weight changes how the movement works.) But Bernard isn’t concerned.

“To create an automaton you need many métiers: jewellers, enamel artists, engineers, watchmakers,” he says.

“From the start, all these craftsmen are involved, and those conversations start before a technical drawing exists. That’s essential because craftsmanship isn’t something you add later; it’s built in from the first idea. The most important thing is we all ‘sing the same song in the same rhythm’. We stay in phase, we listen to one another, and that keeps the project coherent.”

Precious stone appliqués, golden threads, the finest pure fabrics and exceptional craftsmanship define Loro Piana’s elegant Ramadan 2026 Capsule Collection

PHOTOGRAPHER: AMINA ZAHER MODEL: AMIRA AL ZUHAIR

Crewneck Sweater

Female Intuition

Imogen Poots on seeing through fakery, attitude problems, rites of passage and acting in Kristen Stewart’s directorial debut

WORDS: PATRICK SMITH

AA few years back, a director told Imogen Poots she had an “attitude problem”. “I thought [his] idea was silly,” she tells me. “But he said that to me in front of a whole crowd of people, which was lame. He was a nice man, but we weren’t creatively right for one another at all, and it’s funny in hindsight how me not feeling comfortable, or not understanding something, warranted that comment. He was treating me like a kid. But at this point I see it as a compliment. Yay for attitude problems.”

We’re in a bar in Soho the day after the London Film Festival premiere of Hedda, a rambunctious rejig of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler that demands no niceties of its combative leading lady. The blonde hair, half up, half down, tumbles disorderly.

late actor Anton Yelchin. Her hands often clench and unclench. She’s sharp and solicitous, our conversation ricocheting so much that I lose track of my prepared questions. She is also very funny in that particularly English way – bone-dry one moment, nerdishly self-mocking the next. Growing up in west London, she loved cinema, obsessing over indie filmmaking titans from Terrence Malick to Peter Bogdanovich. But today there is no air of actorly pretension. “This is an industry of absolute Looney Tunes parading as if they’re normal,” she says at one point. “And then these people make movies about the real world and the human experience. Anyway...”

This is typical of Poots, thoughts and digressions spilling out. She’s supposed

‘THIS IS AN INDUSTRY OF ABSOLUTE LOONEY TUNES PARADING AS IF THEY’RE NORMAL’

“My tolerance for bulls*** has always been pretty primed,” the 36-year-old star of 28 Weeks Later (2007) and the Oscarwinning dementia drama The Father (2020) continues. “People have often assumed I’m not aware of the trickery, but I’ve got big eyes. I see all the stuff.” Those Disney-proportioned, bulls***detecting blue eyes blink and widen like a cat spotting its own reflection. Poots is wearing high-waisted jeans, Nike Classics and a white T-shirt Emily Mortimer bought her at the Film Forum in New York; her nail polish is a chipped black. Inscribed across two fingers are the initials AY, in honour of a friend, the

to be here to talk about two films, her latest, The Chronology of Water, and most recent, Hedda. I mention a line of dialogue in Hedda that refers to Poots’s character as a muse. As a word, viewed through a modern lens, it’s considered problematic. “I just think these days there are a lot of terms and ideas that people want to sully, turning something that was once very beautiful and inspiring into something that falls under the term ‘victim’,” says Poots, waving her hands as if conducting invisible symphonies. “I mean, if you think about Edie Sedgwick and Andy Warhol, he wasn’t just projecting onto

her. She brought something to him. It was kind of a two-way street.”

Poots also points to the late, great Diane Keaton. “You could argue she was very much a muse for Woody Allen,” she says, “but that’s because he was lucky enough and smart enough to bottle this miraculous person in front of him. I have so many muses, and whenever I feel really down, those are the things and people I return to.”

A couple of days after our interview, Poots messages me to say she has been reflecting “a lot” on the muse conundrum. “With social media, it’s interesting to consider how everyone has become their own muse,” she writes. “That’s where it starts to get troubling, because you’re not looking back at history, or around you, and you’re not figuring out who you are by what moves you; you’re just staying put and putting filters on your face, to try and mean something to someone, or to yourself. Then everything starts to feel chillingly homogenous.”

Poots has been in the public eye ever since she played a small part, aged 15, as the younger self of a political prisoner in 2005’s V for Vendetta. She landed her first significant role in 28 Weeks Later (2007), the post-apocalyptic horror sequel. Deciding against drama school, Poots learnt on the job. It’s paid off. For two decades, Poots has homed in on the hairline fractures in composed characters, adding a complexity that might otherwise be left concealed. In

her West End debut in 2017, she held her own opposite Imelda Staunton, lending a real depth to Honey, the sozzled, condescended-to young woman in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

There have been parts in the films of her early heroes, Bogdanovich’s screwball comedy She’s Funny That Way (2014) and Malick’s Knight of Cups (2015). Her sense of free-flowing naturalism was there too in Lorcan Finnegan’s psychological thriller Vivarium (2019), and she made a winningly fragile Jean Ross, the model for Christopher Isherwood’s Sally Bowles, in BBC’s 2011 drama Christopher and His Kind But it was as the cocaine-addicted daughter of Paul Raymond in Michael Winterbottom’s The Look of Love (2013) that Poots really left her mark, her performance one of flayed vulnerability. Now, in Kristen Stewart’s bold directorial debut The Chronology of Water, Poots has never been more fearless or bracingly real. She portrays Lidia Yuknavitch, the San Francisco native upon whose 2011 memoir the film is based, as she tries to escape her abusive childhood by developing an obsession with swimming. It is not easy to watch – a maelstrom of grief, resilience and self-destructive desire. The film’s lyrical, non-linear narrative shows how Yuknavitch tried to numb the lasting psychological impacts. Poots was “blown away” by the film’s writerdirector. “I’m very proud of her,” she says. “The stakes were so high to go

and make a film when you’re already a certified, very well-known movie star, so it’s a really brave thing to decide to do.”

During the filming, their shared perfectionism meant shoots ran long. Both were equally meticulous about getting scenes exactly right, says Poots, who trained so hard for the role that she gave herself a hernia. “What should take three hours would take eight.”

She pauses, smiles. “People like [Kristen] don’t really exist any more. A real individual, a very authentic and courageous and kind person.”

She contrasts this with the hollow networking at industry events, where conversations feel performative and distracted. “And then you’re with someone like Kristen, and she is just incredibly present. Her eyes are boring through, seeing your bones.”

Poots notes with approval that she’s seeing “a lot more directors who are women. Maybe one day, once we’ve got enough, we can just call them ‘directors’... we don’t talk about ‘male directors’.”

Structural shifts like these are having an effect, yet Poots, who has spoken in the past about the pressure she’s felt to look a certain way, says that other changes are more internalised.

“I did feel that pressure when I was younger, but not so much any more. There will always be idealising; it’s just what you do in reaction to it. Because tomorrow someone gets spooked, and suddenly there’s a new ideal. It’s dumb to try and chase that.

“At the same time,” she continues, “if you want to smoke cigarettes and not eat, and feel thin and sultry while you’re figuring it out, that’s OK. It’s a rite of passage, and everyone should get to have that. But it’s valuable, too, when that passage ultimately ends and you see how tedious that preoccupation is, and how boring it makes you.”

Poots says she’s never felt more sure of who she is. “That speaks to ageing,” she explains. “There are quite a few years where you’re oblivious to it at the time, but you’re trying things on, and you’re figuring it out, and you’re in the wrong relationships, and you’re in the wrong friendships, and there is a doubt there, but you don’t act on it.” These days, she’s learnt to trust her gut almost immediately. “I’m very happy at the moment.”

By her own admission, when she was younger, Poots sometimes felt unenthused by certain projects. In previous interviews, she couldn’t even bring herself to call the 2014 video-game adaptation Need for Speed by its name, instead referring to it as “the racecar film”. “I don’t have a bad attitude about that movie any more,” she says. “I didn’t want to be there. I was still under the impression that there was a high art, low art divide. Now I don’t think there is.”

Like that old Hollywood maxim “one for them, one for me”?

“Yeah, that’s bulls***,” she says. “There are all these rules that are supposed to be like, frame your future. I don’t

‘PEOPLE HAVE OFTEN ASSUMED I’M NOT AWARE OF THE TRICKERY, BUT I’VE GOT BIG EYES. I SEE ALL THE STUFF’

think that’s real, but I think work is work. You have to start somewhere. I really don’t like people judging young actors for taking certain roles. I think people forget that young actors have to earn money.”

Having moved to the US when she was 19, Poots, who lives in Brooklyn, has recently felt the pull of the UK again. She blames Oasis. “It’s been such a thrill to have them back,” she says. “I’m really happy about their resurgence, because I think the best music in the world... Well, it’s a grand statement, but I do think the English have delivered incredible bands. I’ve seen some people walking around Brooklyn in What’s the Story (Morning Glory)? T-shirts and I’m like, ‘But did you know the album? Did you know it?’

“I’m a huge fan, but the nostalgia of it is interesting,” she adds. “It can be a real sickness.” She cites the fact that she and Brett Goldstein, her costar in the recent romantic drama All of You (2024), talked about getting “pre-nostalgia, which is when we’re so excited about something that we miss it even before it’s happened”.

Fitting, then, that the great British emblems of bad attitude have become Poots’s North Star, tractor-beaming her back to England. She pulls out her phone to read a quote from an Edward Albee play: “Sometimes it’s necessary to go a long distance out of the way in order to come back a short distance correctly.” Her eyes bounce up from the screen. “Isn’t that great?”

These pages, from left to right: Hedda (2025); Vivarium (2020); The Look of Love (2013); Baltimore (2023)

Grasse Roots

The story of Chanel’s perfumes stretches to a century, and the fragrant fields of Grasse are where each chapter begins

WORDS: JOHN THATCHER

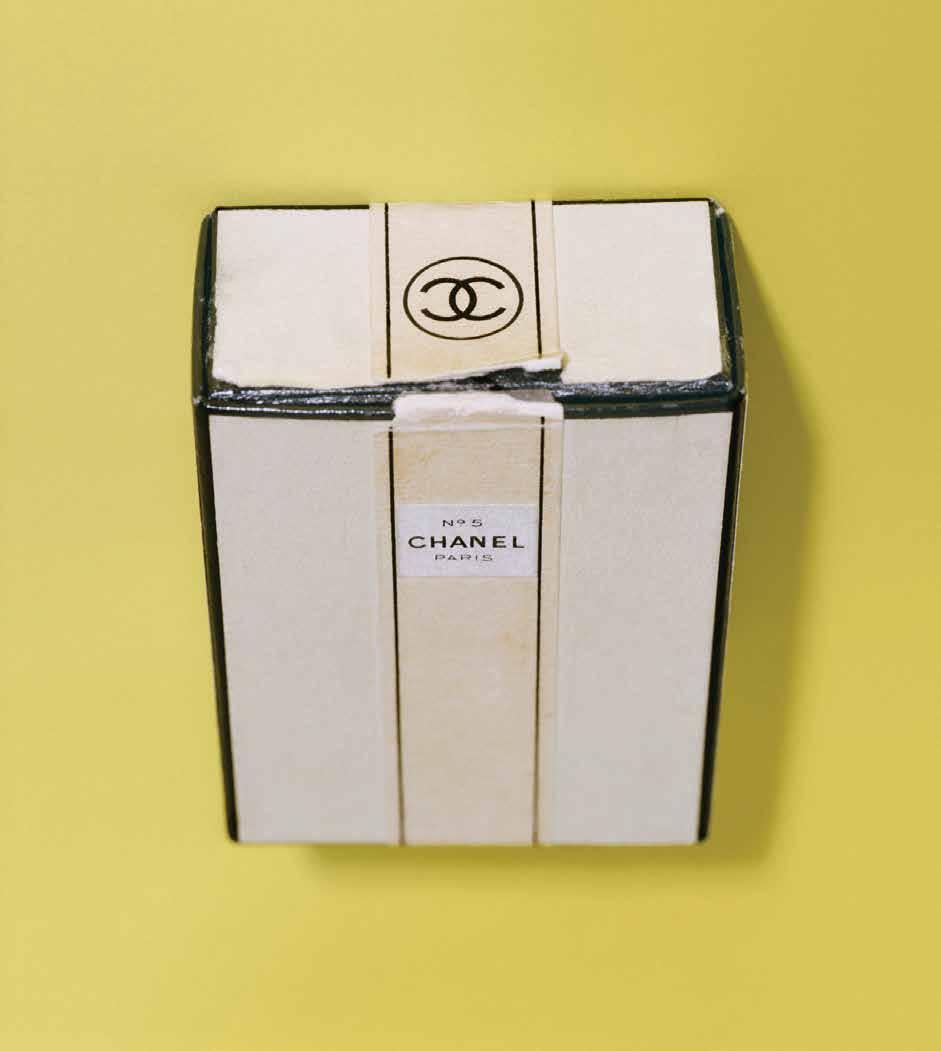

No story of Chanel’s fragrances should begin at any point other than 1921, the year Chanel N°5 was created.

The word ‘iconic’ is bandied about in modern parlance, but it’s one that is apposite for a fragrance that, over a century on since its creation, remains Chanel’s most popular. As author and cultural historian Tilar Mazzeo states in her book, The Secret of Chanel N°5, “N°5 is as much a cultural artefact as it is a scent – a distillation of 20th-century femininity.”

Famously, the name N°5 derives from Coco Chanel choosing sample fragrance number five from those presented to her by celebrated perfumer Ernest Beaux. But its origins begin in the fields of Grasse, a hilly town north of Cannes whose flower-filled landscape has earned it the nickname ‘the cradle of perfumery.’

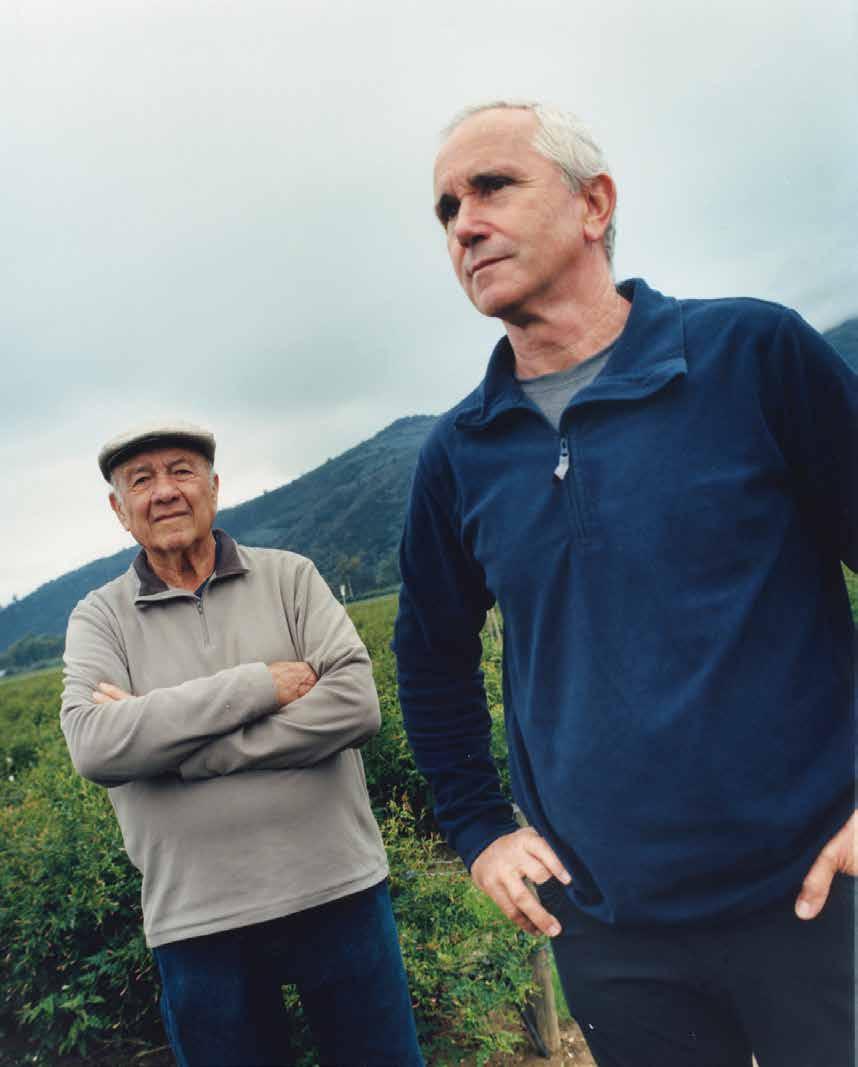

It’s here that the jasmine flower is grown, 1,000 of which are used to produce a 30ml bottle of N°5 extrait, with 560,000 required to obtain 100g of absolute. And it was here in 1987 that Chanel launched a partnership with the region’s largest flower producer, the Mui family, which sees them manage Chanelowned land – which spans some 30 hectares – in a way that not only employs traditional methods and safeguards them, but also ensures the preservation of a way of life on this land that spans centuries.

“Jasmine production in Grasse was on a steady decline and we feared we would no longer have enough for our formulas,” recalls perfumer Jacques Polge, who worked for Chanel for over three decades until 2015, before passing on the baton to his son, Olivier. “At the time, no one was concerned with replanting jasmine, so we conducted a scientific study to find a viable rootstock and bypassed the industry by controlling all of the links in the production chain, from growing the plant right through to its extraction.”

The work resulted in not only the flowering of jasmine, but of May rose,

rosa geranium, tuberose and iris pallida, flowers cultivated for exclusive use in Chanel’s other fragrances.

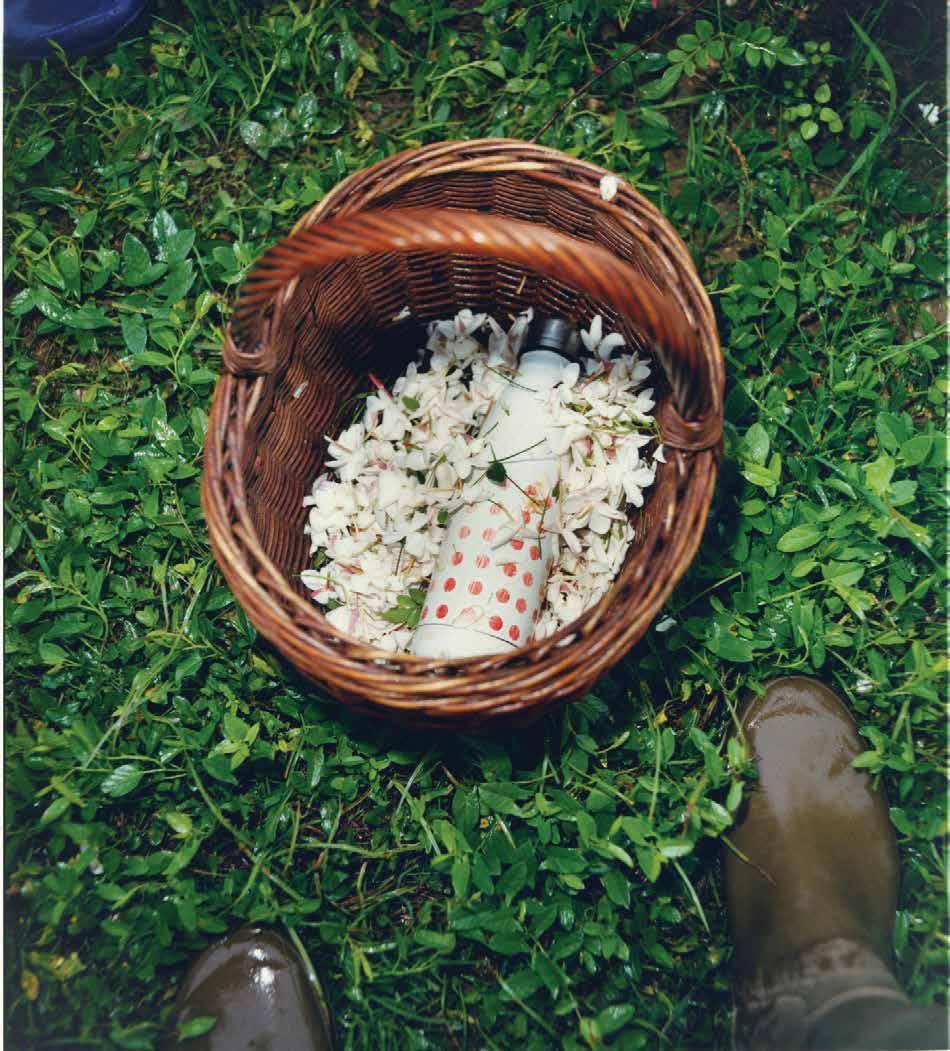

“We are the guardians of Chanel formulas, and we must make every effort to maintain absolute control over our ingredients,” says Olivier Polge, who as Chanel’s In-House Perfumer heads up its Laboratory of Fragrance Creation and Development. The star ingredient in Grasse is undoubtedly jasmine. From August to October, it is harvested each morning from 7am, the fragrant flowers placed in wicker baskets and covered with a damp cloth to maintain their freshness. Every day in the field, each gatherer picks 2kg of flowers. “My favourite moment is when I weigh everything at the end, to see how well we did,” says Julien Buscada, a seasonal jasmine picker. “It’s tough at first, but there’s a rhythm to it. Between the thumb and index finger, we pinch the base and snap!”

From picking, the flowers are sent directly to an on-site factory, where at a processing platform they are placed in a volatile solvent that will soak up their fragrance during extraction.

Once that solvent has evaporated, what’s left is a thick, waxy, aromatic substance termed ‘concrete’, from which – following the instructions received from the Chanel perfumers – a pure, concentrated aromatic liquid is derived. This is the jasmine absolute, one of the most prized materials in perfumery.

“Our flowers are like children whom we raise into adulthood,” admits Fabrice Bianchi, Estate Director in Grasse, where no chemical fertilisers are used to grow the flowers. “We are continually improving our techniques to lead our plants to the highest possible level of quality, without ever taking the risk of depleting the soil. We let the fields lie

Opposite page, clockwise from top: Olivier Polge, Chanel’s In-House Perfumer; jasmine flowers; case for N°5 perfume 1921, Patrimoine de Chanel, Paris © Chanel

‘OUR FLOWERS ARE LIKE CHILDREN WHOM WE RAISE INTO ADULTHOOD’

fallow between crops and we perform in-depth analyses to understand their language. Our aim is to produce the most fragrant flowers and to guarantee the same quality, today and tomorrow.”

There are numerous steps and many people involved before a bottle of fragrance makes it to market, from farmers like Luciana Romano, who has worked the fields in Grasse for 30 years, to Serge Holderith, Director of Floral Extraction Research – “I am the guardian of the very high quality of our extracts. Distillation is less technical; it’s very emotional. We obtain a product that immediately triggers something.” – and Sylvie Legastelois, Chanel’s Director of Packaging Design and Graphic Identity. “Every creation starts with a drawing,” she says. “I need to have the finished object in my hands because of all its subtleties. I have to understand it physically.”

‘A GOOD PERFUME IS ONE YOU REMEMBER’

Olivier Polge is tasked with ensuring that Chanel’s fragrances honour their lineage while he also develops the classics of tomorrow, a considered process that is slow and experimental and one, as a keen musician, he likens to making music. “A good perfume is one you remember,” he says. “A successful fragrance should also provoke an emotion. I think perfume is a cultural object and the perfume we choose to wear says something about us. It’s something we communicate about ourselves that words cannot express.” To date, Polge has developed around twenty fragrances since taking over from his father. “At Chanel, we work with raw materials like a painter would work with his palette of colours.” And like a painter, the end result is always a work of art.

This page, clockwise from top: Joseph Mui, owner of the operation in Grasse, and Fabrice Bianchi, Estate Director in Grasse; Sylvie Legastelois, Chanel’s Director of Packaging Design and Graphic Identity; Serge Holderith, Director of Floral Extraction Research

Chanel

The Conversation

Over his own home-cooked chicken cacciatore, the legendary director Francis Ford Coppola reflects on marriage, family, London in the 1960s and going back to his roots in his personal palazzo hotel

WORDS: HERMIONE EYRE

“I was married 62 years, and I lost her a year ago,” says Francis Ford Coppola. “All my life, there was someone to check in with, emotionally – so now, I… don’t know where I am.” He is telling me about his late wife, Eleanor. “I just learned so much from talking to her every day. She told me about conceptual art, how anything could be art – someone peeling a potato could be art. I thought it was the dumbest thing I ever heard, but it was interesting, even if I didn’t understand or agree with it.” By this point, towards the end of my 24-hour stay at Coppola’s Italian hotel, I’m starting to feel quite close to the great film director. It’s morning, and we are sitting together in a sunny spot in the beautiful garden. Birds call; a fountain burbles. “My favourite time with her [Eleanor] was always in the mornings. Now I have a new routine,” he says. “Every morning I write a list of 10 positive words” – he shows me his laptop – “that I turn into a poem. And I learn a new word.” Today’s word is ‘rescind.’ Coppola is, at 86, a living legend of cinema, and at first I was intimidated to meet him. I flew to Bari, southern Italy, where a hotel driver picked me up, and we drove 64 miles past the Appian Way, the cave-city of Matera, and huge vistas of the Ionian sea, to Bernalda, the ancestral hometown of the Coppolas. The director greeted me stiffly and didn’t take off his dark glasses. But he soon relaxed and his charm flowed, along with torrents of ideas. I can see why his cast and crew followed him to hell and back making Apocalypse Now, why they trusted him going into experimental territory on The Conversation, his Palme d’Or-wining 1974 thriller about taped surveillance, eerily prescient of Watergate. I get why his regular collaborators become like family. When I sheepishly get out a copy of my novel I’ve brought for him, he acts genuinely excited. He baulks at the dedication: “Cross out ‘for Mr Coppola’! Put ‘for Uncle Frankie.’ ”

“I

In 2024, Coppola released a major film, Megalopolis, a lavish, mind-bending Roman epic set in a futuristic New York, starring Adam Driver. To call it ‘long-awaited’ is an understatement: the film had been in gestation since 1983. Reactions were mixed (more on this later), but he is already on to the next film and guarding it closely. He also has a sideline as a hotelier. There are six properties in the Coppola Family Hideaway portfolio, including a jungle estate in Belize, and this neoclassical Italian haven, Palazzo Margherita, here in Bernalda, where generations of Coppolas lived, loved and intermarried. “Twice they needed a papal dispensation for a Coppola to marry a Coppola,” he says, wryly. But this was the most impoverished region of Italy, and, like the fictitious Corleones, they were drawn to America. Coppola’s grandfather, Agostino, a mechanic, emigrated to New York in 1904.

“No one ever went back,” he says, “though we heard all these stories filtering up to us since childhood, about Basilicata, where Pythagoras had his school, and Calabria, where some people still speak Ancient Greek, so it’s like all of a sudden you’re having a conversation with Sophocles… Also, we had to eat all this Italian food. We were kids, we hated it. Do you know what lampascioni are?” Fried hyacinth bulbs, I squeak. He smiles. I’ve done my research. “You know what capuzzelle is? Half a lamb’s head. I used to eat the brains, ’cos I wanted to be smart.” It wasn’t until 1962 that Coppola, aged 22, realised he was within striking distance of the old place. “I was working on a film in Dubrovnik and I looked at the map and I saw it was near. I took the ferry to Bernalda.” Though he couldn’t speak the language, people recognised his family name. There were no hotels, but he was found a bed for the night. “A newlywed couple took me in, I slept in the bed with the husband, I think the wife must have slept in the barn. Think of that!” He had a different homecoming again in the 1970s. “When I came back

after I made The Godfather, it was such a huge success it put me on the map in a way I never expected. I had a lot more cousins than I ever realised…” Palazzo Margherita was built in 1892 on the proceeds of olive oil. Coppola bought it in 2004, from the fourth generation of the Margherita family. He wanted it for a home, but knew he’d be away a lot, so it made sense to run it as a nine-room hotel. The decor was done by the celebrated French interior designer Jacques Grange. “The idea was to keep a patina of age,” Coppola says, gesturing to the romantically decayed masonry in the courtyard. “That’s twice as hard as a restoration.”

The hotel’s ‘Cinecittà’ bar is a shrine to Italian cinema. “I made a film at Cinecittà studios in Rome, and frankly I didn’t like the way it was run,” says Coppola. “There were police everywhere, you had to have the Italian flag… the best thing about it was the bar.” The grande salone on the first floor is transformed into a home cinema at the touch of a button, as the projector comes down and the chandelier, juddering slightly, goes up. A watch-list of 200 or so films, chosen by Coppola, emphasises Italian neorealism, as well as works by family and friends, plus a few Pixars for little ones. The uniformed staff are discreetly brilliant. If you’re thinking this sounds like Wes Anderson’s dream hotel, you’re correct – he is a regular. The swimming pool is half-chlorine, half-saline, wholly inviting.

“It’s unusual because the lining of the pool is black,” says the manager, Rossella De Filippo. “This was Mr Coppola’s idea.” His daughter, film director Sofia Coppola, married a French musician, Thomas Pablo Croquet, known professionally as Thomas Mars, here in 2011. “It was a great night,” he says, remembering waiters running food in from local restaurants. “Which room are you staying in?” he asks. I describe the vaulted ceiling, the white frescoes – “Ah, you’re in George Lucas. That’s where he stayed when he came for Sofia’s wedding.”

Dinner is served. Coppola has cooked chicken cacciatore. I saw him earlier, in the hotel’s open-plan kitchen-dining room, chopping and chatting, wearing an apron. He is dissatisfied with his dish but it’s good, with a peppery, brown jus. No wine is taken. But the conversation still turns to politics. “There’s so much beauty in the world, so much wonder,” he says. “Why can’t we jump over the present situation?’ He believes that soon, we will have no countries. “They’re no longer logical. There’s a reason countries are asserting who they are at the moment. Because it’s at risk. I see a world that has all the cultures of the different nations, but without the nations. It’s going to happen. You know, before 1914 no one even had passports. We’re a human family. It’s our Earth.” If he sounds a little like John Lennon, they are direct contemporaries. He wrote to him in 1977: ‘Dear John, We’ve never met, but of course I’ve always enjoyed your work… I am presently in the Philippines making Apocalypse Now. I’ve been here eight months… I live inside a volcano which is a jungle paradise… if you are ever in the Far East… Please, I would love to cook dinner for you and just talk, listen to music and talk about movies…’ But, sadly, there was not much time left for Lennon (he was shot and killed in 1980), and they never met.

Coppola was always alternative, striving to outwit the studios and the system. He goes quiet when I mention his Academy Awards. “I don’t even know where my Oscars are, I think they’re at a wine company I owned…” He sold part of his winery estate to help fund Megalopolis. “What I regard as more important is young filmmakers telling me they got into the film business because they saw one of my films. The guy who made the new All Quiet on the Western Front,” – Edward Berger – “and Alfonso Cuarón, I met him in Mexico when he was a young man, he liked The Rain People, we talked for, like, four hours.”

Creative communities are everything to him. In 1980 he wanted to found a Creative States of America in Belize. He still believes this sort of model will be the way forward. “There will be pockets where good stuff is going on and people will hear about it and go to New Zealand, or Brazil.” He also thinks UBI – Universal Basic Income – is a cert. “There’s no doubt in my mind.”

“You know what else I hope survives the future? Marriage. There’s a lot more to marriage than fidelity… When I went away filming for more than a week, I always took the whole family, took the kids out of school, they loved the adventure. But Eleanor had things going on in her life. She said: ‘What am I going

to do?’ Why not make a documentary about the film, I told her, and I bought her a motion picture handheld camera. She was one of the best I ever saw. She held it in such a way, I could never do.”

Her documentary about Apocalypse Now was the acclaimed Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, released in 1991. Eleanor was not around to attend the premiere of Megalopolis, but she died knowing he had finally achieved it. “She did,” he nods. “She saw it, in its final version.”

‘ I SEE A WORLD THAT HAS ALL THE CULTURES OF THE DIFFERENT NATIONS, BUT WITHOUT THE NATIONS’

Boyhood memories surface. He was schooled in the trombone by his father, so he could get a scholarship to the New York Military Academy. A great idea, except he hated it, and decided immediately to quit. Did he meet Trump, who studied there too? “No, he was younger than me. He was a rich kid, I was the opposite.

Oppsite page: Frances Ford Coppola and Robert De Niro on the set of The Godfather Part II (1974)

All other pages: Palazzo Margherita

I sold my uniform for the wonderful sum of $200. I was afraid to go home, so I hung around in New York, completely alone, sleeping in flophouses, spending my money on professional women who would dance with you for a few bucks.” Luckily, he had the perfect book for that time: JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Now, he’s just read George Eliot’s Middlemarch, Rudyard Kipling’s Kim, and a biography of Spencer Perceval, the only British Prime Minister to be assassinated. Clues, perhaps, that his next film will be set in England. He liked Katherine Rundell’s book, Super-Infinite, about the English poet John Donne. He’s obsessed with Christopher Marlowe. “Without him, no Shakespeare!”

I ask if Botox is OK for actresses. “Well, that’s scary. The bloom of youth is 27. But at every decade women are beautiful. There’s no age of woman that isn’t beautiful. I always enjoyed inviting 90-year-old ladies, of whom I was fortunate to know a few, to lunch. They’re fascinating, they’ll tell you stories about their lives.” Indeed, throughout our interview he has mentioned admiringly grande dames such as Lady Antonia Fraser (“could you do what she did? Run off with Harold Pinter after you met him at a party?”) and US socialite Lee Radziwill. “Just don’t try and look like a blossom when you’re a flower. It starts just with a little bit here, and then that sags, and you do more, and by the time you’re done, you don’t even look like a person anymore!”

movie called The Garden of the FinziContinis? A movie about a wealthy Italian family, they live in paradise but they know the anti-whoevers are coming, and it’s all going to be over – that’s what the world is like now. Even people who are living well are worried, like there’s going to be hordes of hungry immigrants saying ‘we want food’, and if you don’t give it to us, we’ll take it. That’s the anxiety.”

Still, he’s optimistic. “Human beings are incredible geniuses. We can solve hunger, we can solve war. You hear again and again, oh, these bad people… But humans can do incredible things. We created this world, so we can change it. Time, for instance – the week, it’s just a convention. You just have to be willing to go beyond. There’s a line. If you leap into the unknown, you prove you are free. Mostly people are not free, they are not free to make up their own minds, they are led.”

What can be done to counter this? “Well, I tried to make a film [Megalopolis] that would bring people together to talk,” says Coppola. “What is the real job of art? It’s to illuminate contemporary life, so people can see what’s going on. But studios spend millions to get you addicted to a

company Complicité, was underused as a Roman matriarch. “I saw her in Joel Coen’s Scottish play [The Tragedy of Macbeth]. She can do anything, she’s a chameleon. Incredible.”

Recently, Coppola has been living in Putney, south-west London, reigniting memories of the last time he hung out there, in the 1960s. “There are some bohemian girls in Putney who want to take care of me, and take me to plays. We’ve had a great time. I’ve been staying with an old girlfriend of my friend, the writer David Benedictus.”

Coppola met Benedictus in 1964. Benedictus had already made a splash with his first novel, The Fourth of June, and he was recovering from a liaison with the actress Sarah Miles. He would later be known for continuing AA Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh, but that was to come.

“David was a really cool guy in what was then-known as Swinging London. I took an option on his novel You’re a Big Boy Now and it was my first film. There were a lot of cute chicks at his place, and we both loved looking at movies – he had a 60mm projector. I watched Buster Keaton’s The General for the first time with him.”

‘THERE’S SO MUCH BEAUTY IN THE WORLD, SO MUCH WONDER’

habit-forming formula, like a Marvel film. Then you see a film that doesn’t conform, which is different, oh, it must be bad.”

Film titbits abound. “You know what Olivia de Havilland liked? Champagne. Sofia and I sent her a bottle when she turned 100… You can get better at acting if you work at it. Look at Kevin Spacey… Sofia came to me, she was 13, and said, ‘Am I a dilettante? I like writing but I also like drawing and fashion and photography.’ I said, just do what you love, don’t worry about a profession.”

He adds: “I have a regret. I was offered to write the film of Midnight Cowboy, but I was young, I had no reference for what a male hustler was, then of course I saw the movie and loved it. [Its director] John Schlesinger was so supportive, a wonderful man.”

He has always believed his gift is intuiting the future. “Did you ever see a

When I suggest that mobile phones may have ruined people’s attention span, he replies: “It’s not about that, it’s about what they have been trained to consider attractive. People don’t really like new things. It takes them a while. The same thing happened with Apocalypse Now.” It took a while for people to realise its brilliance? “Well, for it to recoup,” says Coppola. “I had given a big percentage of the gross to Marlon Brando [11.5 per cent]. I thought, I am never going to get my money back, but it’s still making money, more than 40 years later. They call it in the industry a ‘long tail.’ ”

There will be a director’s cut of Megalopolis, he reveals. “I’m going to call it Megalopolis Unbound. That’s the wild version. For when people are ready. There are some amazing scenes with Kathryn Hunter.” The British actress, known for her work with theatre

The friendship endured. “I was just this nutty guy and then I became the guy that directed The Godfather, and even David got a buzz off that. My latest film, Megalopolis, I had been sending him different drafts. Then I got a sad note from his daughter Jessica saying, he’s died.” He pauses. “I love people, and I’ve lived a life of love. Friends are a religion to me… My family used to say of the three kids, my brother August is the brilliant one, my sister Talia is the beautiful one, but Francis, he’s the affectionate one.” He laughs, but he really did spread the love: his father, Carmine Coppola, for many years a frustrated working musician, won an Oscar for Best Original Score for The Godfather Part II; his sister Talia Shire was Oscar-nominated for her performance as Connie Corleone in the same film.

The embers of the evening are low, and he starts to sing. Coppola is a great singer, known for it among his friends. Sitting beside him at the dinner table, I join in, and we sing together – Cole Porter, Noel Coward, Gilbert and Sullivan. “How,” he says, “can people be sad when there are such riches to enjoy?”

BRING THE NOISE

Limited to only five fully customisable examples worldwide, the TALOS XXT is a race-inspired grand tourer with power to burn

WORDS: JOHN THATCHER

A lifelong obsession with motorsport often ends up with a few high-performance road cars parked on your driveway. Rarely does it end up with actually building one. Yet for Jamie Thwaites, managing director at Talos Vehicles, who followed in the slipstream of his successful racing driver father to claim his own wins in the 2020 Ferrari Challenge Coppa Shell Championship and 2022 Land Rover Bowler Challenge Championship, the decision to build the TALOS XXT, a race-inspired grand tourer, was born, in part, of frustration. “As a racing driver, I think racing cars look so cool but are incredibly bad to drive away from the track,” he says. “The idea was to bring the essence of motorsport to the road, which we believe we’ve successfully achieved with the TALOS XXT.”

A donor Ferrari 599XX at its core, the TALOS XXT, which is available in both left- and right-hand drive variants, has been designed to deliver awesome power in tandem with the refinement of a grand tourer. As such, while it

retains the 599’s 6-litre F140 V12, Talos’ engineers have squeezed out more power than the standard car’s 612bhp – now 674bhp – and a touch more torque. It has a top speed of 330 km/h and shifts from 0-100 km/h in 3.5 seconds.

Having started out as a 599XX, were there any elements of the original that simply had to survive the restyling?

“The silhouette and the sound! Both these boxes have been ticked. It retains the classic aggression of the Ferrari 599XX and its unmistakable soundtrack,” says Jamie, proudly. The car’s body panels have been formed from carbon fibre, which was no easy task. “While eyes are instantly drawn to this, and we’re incredibly proud of the finish, it was perfecting this carbon fibre bodywork that was the biggest challenge.”

TALOS Vehicles likes a challenge. The British company, headquartered in the north of England, has its roots in defencefocused special operations vehicles but in recent years has turned its attention to producing a range of modified classic

cars, road cars and limited-run supercars, appealing to collectors and enthusiasts who want exclusivity and performance.

“Creating a truly unique vehicle, such as the TALOS XXT, requires combining good taste with originality. Indeed, our mix of racing experience and engineering discipline defines the way Talos Vehicles builds cars, with a focus on balance, usability, and mechanical connection.”

With the TALOS XXT, the focus is also very much on rarity. “I wanted it to be ultra exclusive, which is guaranteed, as the carbon fibre panel moulds can only produce five units. This means the exclusivity of the TALOS XXT can only appreciate with time,” outlines Jamie. Those five cars will all be unique, given that each is fully customisable, with the details down to the owner to define.

Bespoke options include everything from paint to a manual gearbox, while optional upgrades are available for engine modifications, the drivetrain, the exhaust, roll cage and in-car entertainment. “If you want the bodywork slightly different,

or different wheels, for example, then we can do that.” It’s a similar story for the interior. “The materials are completely up to the customer. We have gone with a more modern race feel, but we can do anything with any materials. Our goal is to create a space that feels uniquely personal.

“Individuality is very important with the TALOS XXT and we’d be delighted to discuss these bespoke options with prospective owners to create their dream car. After more than two years in the making, our passionate and highly skilled team has taken the soul of the racing car and combined that aesthetic with added performance and everyday practicality.

The result is a grand tourer for those who demand nothing but the best and who want their vehicle to reflect their individuality.”

‘ IT’S A CAR FOR THOSE WHO DEMAND NOTHING BUT THE BEST AND WANT TO REFLECT THEIR INDIVIDUALITY’

In its desire to showcase British engineering and craftsmanship from best-in-class experts, TALOS hopes to carve out a niche. “We’re a coachbuilder, and our transition into coach-built road cars grew from our technical expertise in vehicle reengineering. It’s fair to say that the high-end engineering that goes into these creations must be seen to be believed.”

Next up for the brand is a reworked version of one of the most track-focused supercars on the market. “The TALOS XXT is our model number one,” states Jamie. “However, we have three more models in development, of which the second, a Porsche 911 RT, will be released next month. It’s a very exciting time, and it’s a privilege to showcase British engineering at its best.”

A Modern Classic

John Williams MBE on how he brought the glamour –and Michelin stars – back to The Ritz restaurant

WORDS: JOHN THATCHER

JJohn Williams MBE is holding court in his compact office that looks out to the kitchen at The Ritz London, a keen eye occasionally turned towards his team as they prep for lunch service. This space, deep within the bowels of one of the world’s most iconic hotels, is where Williams has spent much of the past twenty-odd years, turning what was once a respected but very much ‘occasion’ restaurant into one that has won two Michelin stars and a reputation as the finest in Britain. Many ingredients make up the successful recipe of The Ritz Restaurant, but the most important is undoubtedly Williams, an engaging, charismatic and energetic character who remains driven to deliver perfection five decades on from when his culinary career began. And it’s what made him embark on that career that Williams fondly recalls as we settle down to talk.

One of six children born in the Northeast of England to a mother who was the family’s matriarch and a fisherman father whose work meant he was often away, Williams was always fond of food, helping his mum in the kitchen so he could claim his edible reward. “The first job she gave me was scraping Jersey Royal potatoes, and after that I had to make mint sauce from scratch. On that particular day, because I’d been such a good lad helping out, about twenty minutes before the lunch was served my mum took three large Jerseys from the pot, put some butter over the top, and said, ‘There you go. That’s for helping us.’ Even to this day, Jersies are my favourite food. Wonderful.”

So wonderful that, to stop them being eaten in The Ritz kitchen, the staff are instructed to hide them from Williams. “I’m not kidding you,” he says, laughing. Starting out in 1974 as a commis chef at the Percy Arms, a small country hotel

on the route between Newcastle and Edinburgh, Williams was keen to learn, always asking questions and lending a hand where one was needed. This passion endeared him to the general manager’s wife, who would often visit France and bring back delicacies for Williams to try, including his first taste of foie gras. It was also at the Percy Arms that he first encountered the likes of grouse, venison and wild salmon, ingredients that “tickled” his curiosity as much as his taste buds. “In terms of what I wanted to do, these things were massive, as I knew then that I wanted to cook ‘posh’ food.” London was calling.

In the decades that followed, Williams held coveted positions within the Savoy Group of Hotels, then owners of The Berkeley and Claridge’s, for whom Williams was appointed Maître Chefs des Cuisines in 1995. The Ritz wanted him; Williams declined, twice. But when they returned for his services in 2004 their offer was well timed. Did he feel pressure from taking on a role at one of the world’s most iconic hotels? “No, in a nutshell,” explaining that, in Claridge’s, he had already worked for one of the world’s best hotels and was therefore more confident than intimidated. “I felt I could improve it.”

‘ THE DINING ROOM STEMS FROM CAESAR RITZ, AND IF YOU MESS WITH THAT, IT SLAPS YOU IN THE FACE’

Williams told his new boss what was required: stay classic to the core but make it relevant for the modern diner. Central to his vision was the dining room – elegantly dressed in Belle Époque-era opulence, it’s the most jaw-droppingly extravagant in London. “That room is the most important thing, food and beverage wise, in the hotel. It stems from Caesar Ritz, and if you mess with that, it slaps you in the face. That’s the truth.” And so Williams, a disciple of Escoffier, set

about ensuring that the food he cooked – and how it was served – matched the room. The ingredients are the best money can buy, the dishes, though rooted in tradition, are executed with a modern touch, and the service is as engaging as it is exceptional. “When I arrived we had waiters – and still do – dressed in tails, but they were just bringing the dishes and walking away. When your waiters are dressed like that, and you have a room in that grand style, you need so much more.”

Now there is much more. Service, says Williams, who was awarded his MBE by Queen Elizabeth II in 2008 for his services to hospitality, is what turns great cooking into a great experience. Waiters perform carving, saucing, and finishing at the table, which Williams describes as craft, not just theatre. It’s technically exacting and visually elegant. “I will never serve anything where the waiter is finishing it, unless it is going to be to the same standard as what I’d serve on a plate.”

This is best observed by ordering Anjou Pigeon à la Presse. “I have some special pigeons which are fed on chestnut flakes, which gives this very, very particular taste,” says Williams. It’s brought to the table by three waiters, the first of whom carves the breasts. The second waiter then passes the carcass through a silver press to release all its juices, which the third waiter then uses as part of a richly flavoured sauce, flambéed tableside. “It’s the harmony of tableside service and the cooking of the kitchen, which is the complete ethos of what we should be serving,” hails Williams.

“And it’s a beautiful dish. You’ve got a little bit of theatre, you’ve got what I believe is a great flavour, and you’ve got something that’s a little bit unique, which it should be in the Ritz.”

It’s the kind of dish that helps turn a two-star restaurant into a three. Is that the goal? “Of course. Michelin is everything. It’s the measuring stick throughout the world now, and it’s the right one.” To gain that coveted third star, Williams talks of the constant need for refinement, execution and personality.

“Do I think we can achieve it? 100%.”

Do so, and you suspect a plate of buttered Jersey Royals will be served in celebration.

THIS CITY THIS CITY

CITY IS OURS CITY IS OURS

CITY IS OURS

WORDS: JOHN THATCHER

Liverpool has long embraced visitors like one of its own, a city with a distinct character – and dialect – shaped by the people who take great pride in calling it home and the cultural and sporting icons who made its name famous across the world

It’s the warmth of the people that you feel first. A warmth that belies Liverpool’s location on the fringe of the Irish Sea, from which a cutting wind whips the historic city. Yet it’s from this turbulent sea that the warm welcome derives.

A port city for centuries, Liverpool has long welcomed people from all over the world, many of them having settled there, making for a truly diverse population. It’s home to the oldest Black African community in the UK and the oldest Chinese community in all of Europe. And when British rule and a potato blight brought famine to neighbouring Ireland in the middle of the nineteenth century, over 2 million Irish migrated to the city in a single decade. Prior to that, a sizable chunk of Liverpool’s population was Welsh. To that melting pot you can now add the likes of Indian, Latin American, Malaysian, Ghanaian, Somali and Yemeni populations.

The fact that so many in Liverpool’s population were once visitors is why they are so welcoming to others. But there’s also a great deal of pride, a philosophy of city first, nation second, which has often seen Liverpool stand apart from the rest of England, culturally and politically.

And well may they stand proud. For if it’s the city’s imports that have moulded its much-cherished independent streak – along with its unique dialect – it is its exports that have put it on the map. Head to the farthest reaches of the globe and the names of The Beatles and Liverpool Football Club will resonate.

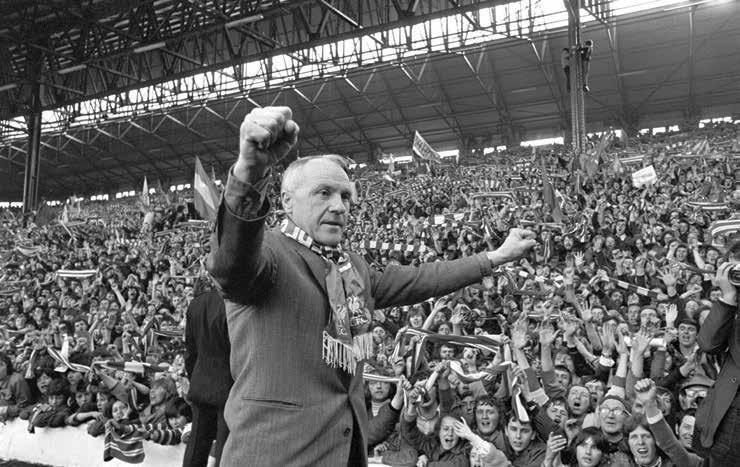

Long considered the most popular – and enduringly influential – band in history, The Beatles were formed in Liverpool in the early 1960s, a time when the city’s leading football club was being turned into a “bastion of invincibility” by its inimitable manager, Bill Shankly. He took the club from second-tier also-rans to successive First Division titles (now the

Premier League), laying the groundwork for decades of dominance that now sees Liverpool crowned as the most decorated club in the history of English football.

Fans of both global institutions now flock to the city to pay homage.

For a time in the 1960s, The Cavern Club would, for many, have felt like the centre of the known universe, an intimate, atmospheric, brick-walled space in a cellar that became known as the birthplace of The Beatles. The Fab Four played 292 times at the venue, screaming girls and all, from 1961-1963, sharpening their sound before it serenaded the world.

‘THE BEATLES WERE FORMED IN LIVERPOOL AT THE SAME TIME ITS FOOTBALL CLUB WAS BEING TURNED INTO A POWERHOUSE’

The club was demolished in the 1970s but rebuilt just four years later, when a second stage was added to increase its footprint and accommodate artists that in recent times have included the likes of Oasis and Adele. But The Cavern will forever be intrinsically linked with The Beatles, and every weekend a brilliant, sound-alike tribute band, The Cavern Club Beatles, performs here, the queue to see them snaking from the venue’s door down Mathew Street, just as it did in the Sixties.

You’ll find a faithful recreation of The Cavern Club, right down to exact measurements, at the city’s award-winning The Beatles Story, a fantastic museum located at The Royal Albert Dock that

takes visitors on a journey through key stages and places from the band’s career. It’s an immersive experience that also brings to life the culture and societal changes The Beatles passed through (and in many ways influenced), an experience bolstered by the sheer passion of the staff, who will point out everything from John Lennon’s last piano and his famous circular glasses, to handwritten lyrics to ‘Let It Be’ and the original 45rpm demo of ‘Love Me Do’, which The Beatles enthusiastically mailed out to radio stations in the hope of kickstarting their career.

Original memorabilia is also a big draw at Anfield, home of Liverpool FC. On the days when Liverpool are not putting visiting teams to the sword on Anfield’s hallowed turf, visitors come in their thousands to the LFC Museum to see the gleaming trophies the club has won throughout its history, including an original European Cup, given to a team if they have won it five times, which only Liverpool, AC Milan, Bayern Munich, Barcelona and Real Madrid have done.

Entrance to the museum is part of the Anfield Stadium Tour, which also includes a Q&A with former players and a behind-the-scenes peek at what is one of football’s most storied grounds. It takes in the players’ changing room; the iconic ‘This Is Anfield’ sign, placed at the behest of Bill Shankly above the entrance to the tunnel that leads to the pitch to instil pride in his own players and fear into the opposition’s; and a walk around the pitch towards The Kop end, otherwise known as Liverpool’s twelfth man for the strength of its vocal support, particularly during must-win Champions League fixtures – just ask Messi and Barcelona. Though whatever fear Messi and Co. experienced the night Liverpool overturned a three-goal deficit on their way to winning a sixth European Cup/

Opening pages: Royal Liver Building

This page, clockwise from top: The Cavern Club; Bill Shankly enjoys the adulation of The Kop at Anfield; spa at Titanic Hotel Liverpool