UPPER RIO GRANDE

BY BRIAN LA RUE

BY BRIAN LA RUE

BY LANDON MAYER

HEALING RIVERS AFTER FIRE

TROUT IN THE CLASSROOM-

FINDING NEW HOMES FOR NATIVE TROUT

Thousands of anglers, guides, lodges, and shops served since 1999.

Colorado Family and Veteran owned and operated.

Pescador on the Fly is a small, family-owned business. We keep our overhead low to pass on big savings to anglers all over the world.

The El Rey G6 series is a top of the line, 6-section rod, available in 3, 4, 5, 7, & 9 weight.

Direct to the Angler Pricing Save up to 50% on your fly-fishing gear

Jack Tallon & Frank Martin

Landon Mayer

EDITORIAL

Frank Martin, Managing Editor frank@hcamagazine.com

Landon Mayer, Editorial Consultant Ruthie Martin, Editor

ADVERTISING

Brian La Rue, Sales & Marketing brian@hcamagazine.com Direct: ( 720) 202-9600

Mark Shulman, Ad Sales Cell: (303) 668-2591 mark@hcamagazine.com

David Martin, Creative Director & Graphic Designer

Frank Martin, Landon Mayer, Brian LaRue, Angus Drummond

STAFF WRITERS

Frank Martin, Landon Mayer, Brian LaRue, Joel Evans, David Nickum, John Nickum, Peter Stitcher

Copyright 2017, High Country Angler, a division of High Country Publications, LLC. All rights reserved. Reprinting of any content or photos without expressed written consent of publisher is prohibited. Published four (4) times per year.

To add your shop or business to our distribution list, contact Frank Martin at frank@hcamagazine.com.

Distributed by High Country Publications, LLC 730 Popes Valley Drive Colorado Springs, Colorado 80919 FAX 719-593-0040

Published in cooperation with Colorado Trout Unlimited 1536 Wynkoop Street, Suite 320 Denver, CO 80202 www.coloradotu.org

It started as a dream 10 years ago when my cofounder, Brandon Kramer, and I decided we saw too much trash on the dream stream and wanted to make a difference. In 2015, we took the day and cleaned the South Platte River at Charlie Myers SWA. This was the start of what we call the “Dream Team.” A key group of volunteers who work hard before, during, and after the event. That number has now blossomed into over 250 volunteers, allowing us to collect trash, not only from the “dream stream”, but all of South Park's fisheries. Antero, Spinney,

and 11-mile reservoirs. Badger basin, Tomahawk, Spinny, SWA, and the Charlie Meyers SWA South Platte River drainages. Over the past decade, we have collected over 7 tons of trash from these fisheries. Seeing anglers realize that one person and one piece of trash matter is incredible. Not to mention the families and all the children that will now know that cleaning the resource is a celebration and a part of our lives.

Thanks to all those who participated in this year’s Clean the Dream project!

ONE OF THE MOST INSPIRING THINGS THAT CLEAN THE DREAM, NEXT TO PROTECTING THE RESOURCE, ARE TEACHING OUR YOUTH, THE STRENGTH IN A COMMUNITY, AND HOW IT CAN MAKE SUCH A SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE. LITTLE KAYCEE, GRANDDAUGHTER OF JULIE AND JJ VEST SHOWS OFF HER CLEANING GUNS!

THIS IS A CONSTRUCTION SIZE 30 YARD DUMPSTER FULL OF TRASH THAT WAS COLLECTED FROM ALL OF SOUTH PARK. WE DO NOT JUST CLEAN THE DRAIN STREAM, WE CLEAN ALL THE MAJOR FISHERIES WITHIN 200 MILES. THIS YEAR’S TOTAL WAS 2040 POUNDS OF TRASH!

TO CELEBRATE THIS 10 YEAR ANNIVERSARY, AND THE PAST CLEAN THE DREAM EVENTS WE HAVE A GIANT RAFFLE THAT IS MADE POSSIBLE BY THE WONDERFUL COMPANIES, FLY SHOPS, AND PRIVATE DONATIONS FOR VOLUNTEERS TO WIN. WITH OVER $27,000 AND GIVEAWAYS, THIS YEAR YOU COULD EVEN GO HOME WITH A BOAT! THANK YOU FOR BELIEVING IN US AND OUR CAUSE, YETI COOLERS, SCIENTIFIC ANGLERS, RL, WINSTON FLY RODS, BAUER FLY REELS, WINSTON SUNGLASSES, SIMMS, FISHPOND, RIVER SMITH USA, BLACK BEAR DINER, RICHARDSON HATS. THE PEAK FLY SHOP, ANGLERS COVEY FLY SHOP, TUMBLING TROUT FLY SHOP, CHARLENE, EDDY DIBNER, NEW BELGIUM BREWING COMPANY, AND BOONZAAIJER'S DUTCH BAKERY.

SCOTT ROBERTSON, RON ROBERTSON, PEGGY STEVINSON, JIM BROWNING, DIANE BROWNING, COLIN DUNN, JACK SHAW, CODY KOLLIKER, LARRY MEYER, BILL STEWART, JON EASDON, AVA EASDON, MADDIE EASDON, RIVER MAYER, LANDON MAYER, TONY DYBECK, STEVE MALDANADO, TAMMY MALDANADO

FROM AGE 5 TO 15 THIS HANDSOME YOUNG MAN RIVER MAYER HAS GROWN INTO A WONDERFUL PERSON. IN FACT, 6 INCHES IN THE LAST YEAR TO MAKE HIM ALMOST AS TALL AS DAD.

JACK SHAW DELIVERS SOME OF THE BEST GRUB IN THE WEST. HE PREPARES THE FOOD EVERY YEAR TO FUEL UP TO 300 VOLUNTEERS!

LUCAS FARNHAM HAS BEEN THE FINANCIAL SUPPORT MAKING THE CLEAN THE DREAM POSSIBLE SINCE DAY ONE. THANK YOU LUCAS! HERE IS A GOOD EXAMPLE OF WHY HE LOVES THE “DREAM.”

THIS MIGHT BE THE ONLY TIME IN MY LIFE I AM EXCITED TO SEE A TRUCK BED FULL OF TRASH. VOLUNTEERS GO ALL OUT AND GATHER TRASH, METAL, AND TIRES TO KEEP THE LANDSCAPE, RESERVOIRS, AND RIVERS CLEAN.

IT WAS A PLEASURE TO WORK ALONG SIDE DAN SPRYS MANAGING RANGER AT 11 MILE STATE PARKS. HE AND HIS WONDERFUL STAFF PROVIDED PASSES, ROAD ACCESS, RIVER SIDE PARKING, EVENT PERMITS, TRASH BAGS, AND WORKED ALONGSIDE VOLUNTEERS CLEANING THE DREAM. WITHOUT HIS BELIEF IN OUR CAUSE THE EVENT WOULD NOT BE POSSIBLE.

THE DREAM LOOKING CLEAN AND PRISTINE!

THIS IS WHAT IT’S ALL ABOUT! SHOWING OUR YOUTH BY EXAMPLE THAT YOU CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE, EVERY PERSON AND PIECE OF TRASH YOU COLLECT MATTERS. ASHLEY, VANNY, AND BRECK ENJOYED A FAMILY DAY IN THE WATER.

IT’S NOT A PARTY WITHOUT THE HATS! FRED MILLER, PEGGY STEVINSON, RIVER MAYER, AND

DRIVE FURTHER, FIND

by Brian La Rue

I’ve been writing the destinations column for High Country Angler for 16 years, so that equates to 64 fisheries. With that said, I’ve never spotlighted a hot bite, let alone wrote about a fragile fishery (and yes- I’ve been accused of ruining the Snake River after a story on Henry’s Fork, believe it or not). With that said, the Upper Rio Grande proved to be a tough nut to crack.

I’ve covered waters in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Wyoming, New Mexico and Utah (having lived in 5/7 of those states), with the occasional outof-region opportunity thrown in like Texas redfish, SoCal largemouth and Belize bonefish. But to many of us in Colorado, the Upper Rio Grande River is still somewhat unknown. Why? Because the river is centrally located, far away from any major cities.

The Rio Grande is America’s fifth longest river overall, but most don’t want to drive or hike any further than they must to wet a line. So, as Colorado’s population grows, it’s going to get more crowded. It already has (no single article is going to change that, but maybe a barrage of huge fish on social—for sure) But with so many options along the way from all directions, sometimes a destination requires extra drive time and a little homework. That’s the Upper Rio Grande, my destination here. I hope you enjoy it!

On the Upper Rio Grande you’ll find Gold Medal waters, where the Colorado Department of Parks and Wildlife says you’ll have one of the best opportunities to catch a trophy fish in the state. Rainbows, Browns and Cutties average 14-18 inches, but we all know there is always something special lurking.

The small town of Creede would be a sweet spot to set up camp. I’m going to talk about the water around Creede and down to Del Norte, and of course, not highlight any spots, just a few obvious access points. There are a few fly shops and guide services, but getting a call back or help was the toughest part of this article.

With that said, there is a ton of information on the Rio Grande online, via books, tap a friend’s knowledge or fall back on your own experience like I did here.

I’ve heard this stretch of river called “Madison like” by several friends. That translates into a typical Colorado fishery with the added bonus of a bigger bug menu to add to the sizeable river. Salmonflies, mayflies and terrestrials add to the fray, giving anglers a chance at a Madison or Montana like day.

From below the Rio Grande Reservoir to Del Norte can be amazing. I like wild areas myself, so the Weminuche Wilderness’ roughly eight miles of water can be rewarding. Think flat water, a few braided channels and willows with eager trout. June and July are my favorite times to hit this water. There are some deep runs holding sizable trout, so larger nymphs like Bitch Creeks and Kaufmann’s stones; like I said, think Montana bugs and then switch to a salmonfly when those slow-flying morsels begin to hatch. Also carry PMDs, parachute Adams and green Drakes. But that’s for 2026!

For current fall and then winter fishing, maybe

try Box Canyon. It’s quite a hike to get in here. It will take at least a 2-miles hike to get in, and you might need a machete, but a few do it. Go with a buddy and be safe. As I always say, if it takes extra effort and a little blood and sweat, fishing is probably going to be wild. Only do this trip September/October, not on a July or early August day with heavy thunderstorms predicted.

If I were headed out to fish the Upper Rio Grande today through late November, it would depend on the weather. Since it’s a sizable drive to get to the area, I’d stay a couple days to get the full experience.

To continue our exploration downriver, the next stretch is home to Rio Grande and Marshall Park campgrounds after a private water stretch. This stretch offers a diverse river setting with all kinds of water and a lot of brown trout. Here you’ll find a

wide river with float options. Many like this stretch down to Wagon Wheel Gap and beyond, but much of it is private.

To give you an idea of flows, the river peaks about 2,000 cfs in spring/early Summer, but averages 1,200 to 1,600 cfs and is often wide and flat, some rapids— much like the Madison again. Flows reduce to about 500 cfs this time of year, so floating options go out the window. For a fall run, think dries, streamers and wade fishing.

And like the Madison and other Montana rivers, The Upper Rio Grande also can fish well on caddis, red quills and rusty spinners. For wading anglers, the Coller State Wildlife Area is ideal with lots of strewn boulders, slots and structure. There you’ll find plenty of access points and parking areas.

As it gets cold into October and November, the

BWOs, midges and streamers are most prominent. When snow starts flying, midges and streamers will be the best bet, like any typical Colorado fishery. Don’t be afraid to bang a streamer off and around boulders or along the willow-lined banks.

If all that Gold Medal water on the Upper Rio Grande River didn’t pique your interest, the surrounding area is also loaded with tributaries and small lakes for even more opportunities to wet a line, particularly one with a dry fly attached. Open a Google map, I won’t help you there.

Well, there you have it. Everything you need to know to plan a late 2025 trip or 2026 salmonfly run to fish the Upper Rio Grande in 2026. I hope you have better luck with the shops in the area.

As I mentioned earlier, I’ve experienced a lot of cool fisheries and written about them for the magazine a long time. For HCA, you can see our back issue section online to read 51 of my destination columns.

Our team archives older issues there, so read up

on how-tos with Landon or see what other fisheries I’ve highlighted and plan a trip for 2026. You are also always welcome to e-mail me at Brian@HCAMagazine.com and ask questions. Happy to help, take care—Brian.

High Country Angler contributor Brian La Rue enjoys giving fly fishers ideas of where to go for an adventure. Feel free to reach out to Brian at Brian@hcamagazine. com if you want your lodge or guide service featured in an upcoming promotional marketing plan.

The walls of the gorge temporarily widened, permitting a shaft of late afternoon sunlight upon the pool. I slipped off my pack, set my rod against a fallen aspen and sat on the grassy bank to watch. From its narrow origin at the tail of a riffle, the pool fanned wide, a scattering of boulders creating several current seams with glassy slicks in between. Being reasonably sure he was downstream of me, I decided to wait for my fishing buddy to catch up and then decide who would get the first cast. I’d last seen him a couple of hours ago, standing in the river working the current seams of a busy riffle. To give him time and space I’d taken to the trees along the river bank and hiked a quarter mile ahead before dropping down again into the river at a place where the current co-joined at the tail of a small island that split the flow.

It was possible he’d passed ahead of me unseen while I’d been engrossed fishing one of the several runs I’d stopped at, nymphing the drop offs and feed lanes, but I didn’t think so. I was sure he’d have stopped to ask how the fish were treating me, or I’d otherwise have felt his presence as he passed.

So I sat on the grass along the edge of the pool and savored the last beer and ate the last cheese stick from my pack. I knew there’d be fish in the pool. I’d wait til he

got here. I wondered how many he’d caught so far. I’d enough to satisfy me for the day, but I tend to be a somewhat lazy angler, whereas he is always thinking, changing approach, changing flies, changing weight and depth.

Besides, here seemed a good place to call it a day. From where I sat I marked a relatively clear route up the side of the gorge to the road above. Further up river, the walls became steeper, the rock looser. Prudence seemed to dictate this would be the best exit point. He’d be along in a few minutes. I’d watch him catch a couple of fish, then we’d hike up to the road and back to camp.

I finished the beer and lay back in the grass and power-napped for a few minutes. When I came to I sat up and looked around. No sign of him. I looked at the sun, lower now to the mountains. The shadows were a little longer across the water, the air taking on a late October chill.

Should I wait any longer, head downstream to find him, or hike out? I don’t wear a watch when fishing -for starters it’s a ready made spousal excuse - but I guessed I’d already been waiting a half hour at least. I thought through the multiple possible scenarios - he was up ahead of me, downstream with a broken ankle or some kind of medical event, eaten by a bear, tak-

ing a nap himself ….The most likely option is usually the obvious one. In this case, I surmised he’d already found an alternative way out of the gorge. I decided to climb out myself, take the road back down to camp, and if he wasn’t there, then consider the next step.

The way out was steep, two or three hundred feet of vertical. near straight up the fall line. Head down, I’d count fifty paces then stop for a breather, heart hammering against my chest, pulse pounding in my ears, marveling at the power of the innocuous, ever-present ball and chain we call gravity. Finally, brow and pits drenched in sweat, I made it to the gravel road and turned downhill, camp twenty minutes walk away.

Just then a familiar truck approached from that direction. He pulled up next to me. I gratefully set my rod and pack in the back and climbed in.

“I decided it was easier to take the downstream way out,” he said. “Figured I’d come looking for you.”

“Good call. Glad you did.”

He took a sip from his travel mug as we continued on up the road, in search of a place to turn around. I looked at his mug, then looked about the cab, then back at him, keeping my silence.

“You’re right,” he said, feeling my stare. “A good mate would have brought another beer.”

Hayden Mellsop is an expat New Zealander living in the mountain town of Salida, Colorado, on the banks of the Arkansas River. As well as being a semi-retired fly fishing guide, he juggles helping his wife raise two teenage daughters, along with a career in real estate.

Fly fishing guide. Real Estate guide.

Recreation,

s a fte R f i R e

Ash and sediment from burned hillsides can choke rivers. Restoration projects slow water, trap sediment, and rebuild natural floodplains.

When flames sweep across a forest, the destruction is plain to see. Blackened trees, scarred ridges, and miles of ash tell a story of loss. Yet some of the deepest wounds unfold in the months and years after the fire is gone. Sediment clouds the rivers. Hillsides give way under heavy rains. Roads collapse and drinking water becomes more vulnerable. For trout and other fish, streams can become unlivable.

Colorado knows this story too well. In 2020, the Cameron Peak and East Troublesome Fires tore across more than 400,000 acres of northern Colorado. Nearly five years later, scars remain etched into the land. Rivers still carry heavy loads of sediment. Communities continue to face the downstream risks of water system failures and unstable slopes.

“This is not just about burned trees,” said David Nickum, Executive Director of Colorado Trout Unlimited. “It is about the health of our rivers, our communities, and the fish and wildlife that depend on them.”

In response, the U.S. Forest Service and Trout Unlimited created a long-term partnership to repair what fire has damaged and to prepare watersheds for the future. Backed by $10 million over eight years, the effort focuses on the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests, where the Cameron Peak, East Troublesome, and Williams Fork fires created the greatest need.

Half of the funding is devoted to habitat restoration. The other half supports infrastructure improvements such as culverts, road crossings, and repairs that keep roads safe and water systems reliable. Together, these projects reduce future risks while restoring balance to streams.

“This work is about more than replacing what was lost,” Drew

Peternell, Colorado State Director of Trout Unlimited said. “It is about making rivers stronger so they can withstand the next big storm or fire.”

Rather than forcing rivers into engineered channels, Trout Unlimited’s restoration approach relies on natural processes. Native willows are planted to anchor streambanks. Carefully designed structures slow water, capture sediment, and rebuild natural floodplains. Reconstructed streambanks are shaped with soil and wood rather than concrete. These techniques create shaded, cool-water habitat where trout can thrive once again.

The benefits ripple outward. Cleaner water reaches downstream communities. Flooding risks are reduced. Wildlife gains back the habitat it lost.

Recent fires across the West, including Colorado’s

A burned landscape shows how wildfire impacts rivers and forests. Restoration work helps stabilize streambanks, reduce erosion, and support recovery.

South Rim Fire near Black Canyon of the Gunnison, are reminders of how frequently large fires occur today and of the growing threat they pose. What happens after a fire can be just as destructive as the flames themselves.

Without restoration, sediment will continue to smother rivers, trout populations will decline, and infrastructure failures will multiply. These problems do not heal on their own.

But recovery is possible. On-theground work is already underway, guided by science, collaboration, and a commitment to resilience.

Within the Arapaho and Roosevelt National Forests, the Forest Service and Trout Unlimited are prioritizing the areas most in need. The work will continue for years to come, steadily rebuilding ecosystems and protecting communities. Colorado Trout Unlimited is also helping ensure that volunteers, local leaders, and chapters remain engaged in the effort.

“Fire-impacted rivers cannot recover on their own, but with the right people, resources, and commitment, they can come back stronger than before,” said Stephen Klobucar, Trout Unlimited Upper Colorado River Project Manager.

Trout Unlimited’s projects align with U.S. Forest Service priorities by restoring streams, protecting clean water, and strengthening wildfire resilience.

By repairing stream crossings, replanting riparian areas, and stabilizing streambanks with natural materials, TU helps watersheds recover while also reducing flood risks and trapping post-fire sediment. These projects create local jobs, support rural economies, and expand the Forest Service’s capacity to meet its management goals.

• Walking distance to the gold-medal waters of the Gunnison River • Near Blue Mesa Reservoir • Vintage charm and ambiance

• Great outdoor space

• Multiple room layouts

• Fully stocked kitchens • Spacious boat parking, including free long-term for multiple stays

by Colorado TU Staff

Habitat for Colorado’s native cutthroat trout has declined to only a small fragment of the coldwater streams and lakes they once occupied throughout the state. Our native trout heritage includes three different lineages of Colorado River cutthroat – San Juan, Uncompahgre, Green River –as well as Rio Grande cutthroat and the official state fish of Colorado, the Greenback cutthroat. Yellowfin cutthroat were an additional subspecies (native to the Arkansas basin) that is now believed to be extinct.

Multiple factors contributed to the decline of Colorado’s native cutthroats – habitat loss and fragmentation, pollution, overharvest – but the greatest single cause was competition and hybridization with introduced species. For those working to recover native trout, this means that one of the key steps is to remove those other introduced species in preparing habitats for native trout restoration. Typically, this is done using a fish toxicant called Rotenone, which in turn is detoxified at the bottom of the area being reclaimed, so as to avoid impacts to downstream fisheries. Rotenone targets fish and species with gills - it does not threaten birds and mammals, or impact downstream drinking water supplies.

Fish removal efforts are led by professional biologists with Colorado Parks and Wildlife, coordinating with federal agency biologists and other partners. Colorado TU has been pleased to help support the agencies on this necessary work as they open stronghold habitats that can help provide a secure future for Colorado’s native cutthroats. This summer, work has advanced on two notable stronghold projects – for Colorado River cutthroat trout in the Clear Fork East Muddy Creek, and for Greenback cutthroat trout in the Poudre headwaters.

With leadership from the US Forest Service and seed funding from the Long Draw Reservoir Mitigation

Trust, this project will be a more than 10-year effort to restore Greenback cutthroat trout into some 37 connected miles of their native stream habitat, as well as Long Draw Reservoir. The project is located in the headwaters of the Cache la Poudre within the Roosevelt National Forest and Rocky Mountain National Park. When complete, it will be the largest native trout restoration project in Colorado history. Colorado TU members, and especially the Rocky Mountain Flycasters Chapter, have provided funds and manpower for this project from helping with citizen science data collection to raising dollars that support the restoration efforts. By securing this new stronghold for Greenbacks, we’re both protecting fish and ensuring the opportunity for future generations of anglers and families to experience Colorado’s native trout in their home waters.

This August, agency partners including Colorado Parks and Wildlife, US Forest Service, National Park Service, US Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Land Management all teamed up on a large fish removal project from the Grand Ditch and its tributaries, in the headwaters of the Colorado River. While the ultimate native trout restoration work will take place on the east slope in the Poudre Headwaters, the west-slope Grand Ditch intercepts streams and delivers water – and potentially fish – across the Continental Divide. It was therefore identified as a first area that needed to be reclaimed to prepare for Greenback restoration below the ditch outlet. Few fish occupy these very high-elevation habitats, with the primary population being in Baker Gulch. Originally fish from Baker Gulch were planned for a salvage project and to be transplanted to habitat in northwest Colorado. Unfortunately, the fish had bacterial kidney disease and so could not be stocked elsewhere.

The reclamation project was a complicated effort taking place across four days throughout the Grand Ditch system, with careful planning and tim-

ing required to ensure effectiveness in removing the non-native fish. In 2026, using environmental DNA sampling, biologists will evaluate if the project was fully successful, or if a second treatment may be required. Subsequent phases of work will then remove non-native fish, making way for reintroduction of Greenback cutthroat, in the Corral Creek watershed and in Long Draw Reservoir and the streams flowing into it.

In the high country above Paonia, Colorado’s native trout are returning home. Over the next several years, more than 13 miles of habitat in the Clear Fork of Muddy Creek will be restored for Uncompahgre lineage Colorado River cutthroat trout.

The project began in 2023 with a concrete fish barrier that prevents non-native trout from moving upstream. This summer, Colorado Parks and Wildlife started removing brook trout from above the barrier using fish toxicants and other targeted techniques, preparing the watershed for reintroduction of native cutthroat. Monitoring will continue to track progress and ensure success.

The goal is not just to bring cutthroat back to Clear Fork, but to reconnect nearby tributaries and secure a

rare genetic lineage that still persists in isolated headwater streams. Other native fish such as mottled sculpin will benefit as well.

This work is possible because of a wide coalition of partners, from state and federal agencies to nonprofits, local TU chapters, and Ross Reels, which supported the effort through its Native Series campaign. Together, we are creating a lasting stronghold for Colorado River cutthroat trout.

Across Colorado, from the Clear Fork to the Poudre Headwaters, restoration projects share a common purpose: removing non-native fish, protecting watersheds, and giving native cutthroat a secure future. Each effort represents progress against the very challenges that once drove these trout to the edge of extinction. With strong partnerships and the support of our members, Colorado TU is helping ensure that native trout once again thrive in the waters where they belong.

To learn more about this story and Colorado Trout Unlimited, visit coloradotu.org.

As biologists began returning to camp each evening, a debrief was held to review what went right or wrong that day, lessons learned, and initial plans for the following day’s work. Colorado TU provided for catered meals and port-a-potties to help support the work camp for the crews working on the project – up to 60 people on the busiest days.

The finished fish barrier on the Clear Fork creates a secure zone for Uncompahgre lineage Colorado River cutthroat trout.

The Grand Ditch – dating back to 1890 – intercepts multiple small streams draining from the Never Summer Mountains and delivers it across the Continental Divide. Non-native fish removal took place for the ditch itself and the tributaries that can hold fish.

Fly tying. In the earliest beginnings of fly fishing, and I’m literally speaking of ancient history day one whenever that was, certainly if one wanted to fish with some concocted artificial lure/fly, then one had to make their own fly. Then somewhere along the way, two fly fishers came together and traded a fly each of their own making. Then again, somewhere along the way, one fly fisher figured out he could make some flies in quantity to trade other fly fishers for food and staples. The first commercial fly tyer if you will. And then to be more efficient, commercial tiers perfected tying steps and patterns.

Certainly much has changed - fishing evolved from sustenance to sport, fly tying evolved from necessity to hobby, and today’s fly fisherman has the choice to easily purchase flies, or to tie their own, or to tie commercially. But what has not changed, is the interest tyers have in efficiency and precision.

I’m a self-taught tyer from printed books. 44 years ago, living in a small and remote rural Colorado town, that was the only way to learn. No videos or internet or distance communication, not even a local fly shop offering classes. But along the way I met other tyers and travelled to big city outdoor shows.

Over the decades, I learned a lot and my tying improved. I have never had a desire to tie commercially, but nonetheless I have the same interest as a hobbyist tyer in tying efficiently with consistent quality. And as an instructor, to instill the same precision in students.

There was a specific time and place many years ago when efficiency and consistency came to the forefront for me. I had the opportunity to take a class with fly tying legend A.K. Best. His pass-

ing earlier this year has caused me to reflect on his influence on my tying and our hobby in general. The first thing I did was to revisit his books. I have autographed copies by A.K. of “Production Fly Tying”, first edition 1989, and “Advanced Fly Tying”, first edition 2001. While numerous other fly tying books, videos, and in-person demonstrations are ever new with patterns and materials, these two books remain the authority on efficiency and consistency. Yes, showing patterns, but the patterns are secondary to his instruction on the art of tying itself.

After my class with A.K., I realized just how crude my tying was. Oh, the flies looked ok. They caught fish. But when I looked at a lineup of several identical flies in my box, it was apparent I could do much better. Especially as the years have passed, there are certain fishing locations, for example tailwaters for trout, where to catch fish due to high fisherman pressure

and to changing insect life, flies have become smaller and more exacting.

My point is this: Whether you are tying flies for easy fish in remote locations, technical patterns for pressured waters, or tying commercially, A.K.’s advice is pertinent. To remember and honor A.K., I picked two of his many specific tying points, one from each book, that directly address efficiency and consistency. Obviously I can’t repeat here the entire text of his book, not even a few paragraphs, so I’ll point you to them and leave it to you to discover his detailed discussion.

From Production Fly Tying, Chapter 6, Hackling and Materials, Dry Flies: “Don’t trim away all the web from the butt of your hackle feather”, and “Tie the hackle butts down in front of the wings”.

From Advanced Fly Tying, Chapter 10, Delicate Flies: “The biggest problem in tying small flies is proportion. The proportions are the same as larger flies. Proportion applies to more than just wing height and

tail length. It also dictates body diameter and hackle length. If you use fewer turns of thread to tie down material, you’ll have a chance at becoming a very good small-fly tyer.”

Practice and play, and go fishing in any case, but always pay attention to details.

Joel Evans lives in Montrose in western Colorado. He combines decades of fly fishing, guiding, and fly tying with photography and outdoor writing. He is a pro team member with several companies, is active in Trout Unlimited and Fly Fishers International, including the FFI Fly Tying Group.

by Colorado TU Staff

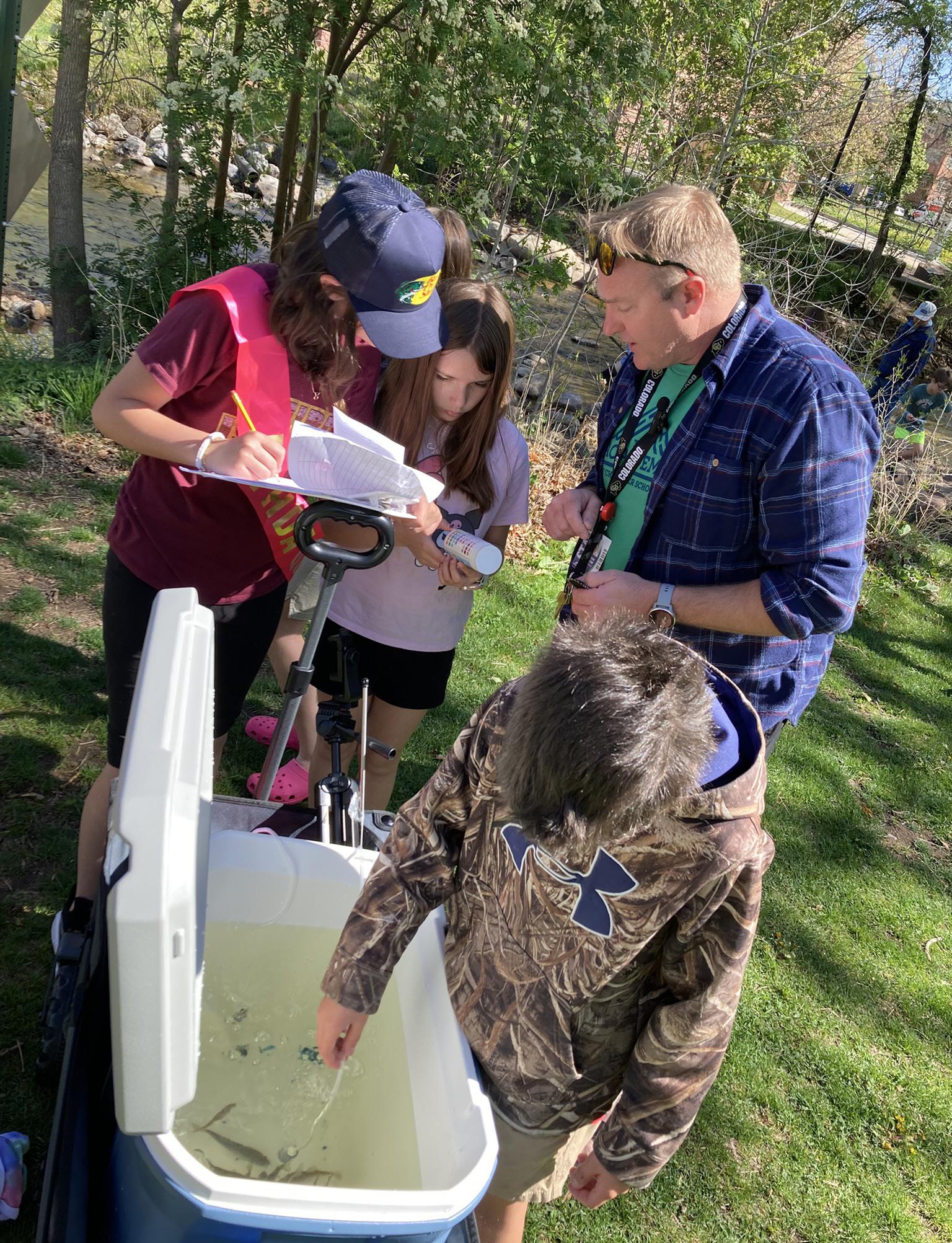

In an age when screens dominate student life, Trout in the Classroom (TIC) brings a refreshing dose of the outdoors into schools across the state—one fish tank at a time.

This hands-on, conservation-oriented environmental education program is captivating students from preschool through 12th grade and beyond, transforming classrooms into living laboratories where trout are raised from egg to fry. Along the way, students learn more than just biology—they learn stewardship, responsibility, and a deep respect for the natural world.

“Trout in the Classroom is not just about fish,” says Natalie Flowers, the program’s dynamic Colorado TU’s Education Director. ”It's about creating future conservationists. We give students a direct connection to their local ecosystems and empower them to become active caretakers of our water resources.”

TIC spans a full academic year and offers schools a unique interdisciplinary approach. Teachers tailor the experience to align with their curriculum, blending science, math, social studies, language arts, and even art and physical education into one unforgettable experience.

Students monitor tank water quality, study stream habitats, and engage in real-world problem-solving as they raise their trout. Most programs conclude with a release day, where students introduce their trout into a state-approved stream, symbolizing their commitment to conservation.

“It’s the kind of learning that sticks with them,” says

Haley Collinsworth, the Western TIC Coordinator. “You can see the pride in their eyes when they release those trout—they know they made a difference.”

Each region of the program brings its own flavor, coordinated by a team of passionate educators and conservationists. In the Front Range part of the state, Audrey Kenney, the Eastern TIC Coordinator, ensures that both rural and urban schools get the support and resources they need to thrive.

“Some of our students have never even seen a stream up close,” Kenney explains. “TIC gives them that experience—and often sparks a lifelong interest in nature and environmental science.”

Behind the scenes, Dr. Martin Harris, the Statewide TIC Coordinator, plays a vital role by connecting schools with trained volunteers who assist with tank maintenance, stream studies, and trout releases.

“Our volunteers are incredible,” Harris says. “They’re mentors, scientists, anglers, and conservationists who bring real-world insight into the classroom.”

TIC isn’t just about raising trout—it’s about raising awareness. Students explore water conservation, learn about job opportunities in the environmental sector, and build the skills and passion to become the next generation of conservation leaders.

As climate concerns and environmental degradation continue to rise, programs like TIC are more important than ever. By connecting students directly to

local ecosystems, TIC fosters a conservation ethic that can ripple outward, influencing families, communities, and future careers.

Whether you're an educator, parent, or nature enthusiast, there are many ways to get involved with Trout in the Classroom. Interested schools can apply

for participation, and volunteers are always welcome to share their expertise.

For more information, resources, and to find out how to bring TIC to your community, visit https:// coloradotu.org/trout-in-the-classroom.

From egg to fry, from classroom to creek, Trout in the Classroom is shaping the conservationists of tomorrow—one student, one trout, and one stream at a time.

To Learn More. To learn more about this story and Colorado Trout Unlimited, visit coloradotu.org.

Dear Friends,

In the previous issue, I explored the interwoven challenges and opportunities facing conservation nonprofits. This issue, I'd like to focus squarely on the opportunities—and the power of optimism that fuels us. More than ever, I see a need to be optimistic about the future of the modern environmental movement.

Now is the time to double down on outreach and community engagement. While environmental protections are under assault and climate-driven disasters accelerate, many young people are grappling with eco-anxiety. A grassroots organization like Trout Unlimited is perfectly positioned to offer them a direct path to action and hope. By warmly welcoming everyone who connects to our work, we amplify the voices speaking for our natural world. We each have a role to play in inviting others to join us in this vital effort.

Part of this work is putting people first. Trout Unlimited has done just that by modernizing our mission statement to bringing together diverse interests to care for and recover rivers and streams. This summer's Colorado Troutfest brought more than 2,000 people to Coors Field to celebrate our work. Nearly 200 of them be-

came members, representing about 2% of Colorado's membership—a significant step forward. Please join me in extending a warm welcome to all of these new members, and then, welcome more. Share our stories, action alerts, and volunteer opportunities. Make your voice echo all along our rivers.

Now is also the time to invest in focusing on the future. My husband and I have supported TU for nearly 20 years with our time, talent, and treasure because we do it for our grandchildren’s children. These are the generations that we will not know, but we savor the impact they will one day have.This same motivation is driving our work in education. TU is strategically growing and evolving programs to connect youth and families to our mission through our Chapters, Councils, and National organization.

For example, Trout in the Classroom has expanded to more than 80 tanks in Colorado schools and other sites. A new in-school Watershed Ambassador program is being piloted this year by the San Luis Valley Chapter. Our teen camp has expanded to grow campers into leaders. More and more Colorado students are stepping from an in-school or local program, to River Conservation and Fly Fishing Camp,

to the National Expeditions program, and onto a College club, internships and Chapter leadership. They are modeling a path for all those they influence. These are intentional efforts that, while not as visible as a stream restoration project, will prove to be the most important work we can do to sustain our impact. This work ensures that everything we advocate for and every river we restore will be stewarded by the next generation.

I’m pretty passionate about people and building relationships across our community. We also have to recognize the opportunities that lie on the operational side of nonprofit business using technology, strategic thinking, and execution. Funding is foundational to all of this work, by embracing integrated digital fundraising and communication, we will reach broader audiences, and build the public-private partnerships necessary for our work. This past spring, we welcomed Cheyenne Johnson as our Director of Philanthropy to help elevate this process. As I write this, the Council’s Executive Committee, volunteers that offer their organizational expertise, are hard at work looking forward and defining the roadmap for TU’s future in Colorado.

As anglers, we are naturally optimistic. How many times have you stood, nearing the end of the day, one last cast? Now is the time to turn our optimism to ensuring the future of water, rivers, trout, and conservation. Embracing and expanding our community and raising our voices together. Therein lies the beauty of being a grassroots organization.

Stay safe on the water, Barbara

Barbara Luneau is Colorado Trout Unlimited’s President, a retired geologist, avid angler, and long-time TU volunteer at both local chapter and statewide levels. She has a deep commitment to youth programming, including serving as the volunteer director of the annual CTU River Conservation and Fly Fishing youth camp.