Business - eBook PDF

Visit to download the full and correct content document:

https://ebooksecure.com/download/business-ebook-pdf/

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Fig. 21), the vine (Fig. 47), and the tall reeds and grasses of the marsh (Fig. 119) are also imitated.[249]

F�� 119 Marsh vegetation; from Layard

We feel that the sculptor wished to reproduce all those subordinate features of nature by which his eye was amused on the Assyrian plains; he seems almost to have taken photographs from nature, and then to have transferred them to the palace walls by the aid of his patient chisel. Look, for instance, at the reliefs in which the process of building Sennacherib’s palace is narrated. The sculptor is not content with retracing, in a spirit of uncompromising reality, all the operations implied by so great an undertaking; he gives backgrounds to his pictures in which he introduces, on a smaller scale, many details that have nothing to do with the main subject of the relief. Thus we find a passage in which men are shown carting timber, and another in which they are dragging a winged bull, both surmounted by a grove of cypresses, while still higher on the slab, and, therefore, in the intention of the sculptor, on a more distant horizon, we see a river, upon which boatmen propel their clumsy vessels, and fishermen, astride on inflated skins, drift with the stream, while fishes nibble at their baited lines.[250]

Neither boatmen nor fishermen have anything to do with the building of the great edifice that occupies so many minds and arms within a stone’s throw of where they labour. They are introduced

merely to amuse the eye of the spectator by the faithful representation of life; a passage of what we call genre has crept into an historical picture. Elsewhere it is landscape proper that is thus introduced. One of the slabs of this same series ends in a row of precipitous heights covered with cypresses, vines, fig and pomegranate trees, and a sort of dwarf palm or chamærops. [251]

They thought no doubt that the spectators of such pictures would be delighted to have the shadowy freshness of the orchards that bordered the Tigris, the variety of their foliage and the abundant fruit under which their branches bent to the ground, thus recalled to their minds. The group of houses that we have figured for the sake of their domed roofs, forms a part of one of these landscape backgrounds (Vol. I. Fig. 43).[252]

We might multiply examples if we chose. There is hardly a relief from Sennacherib’s palace in which some of those details which excite curiosity by their anecdotic and picturesque character are not introduced.[253] We find evidence of the same propensity in the decoration of the long, inclined passage that led from the summit of the mound down to the banks of the Tigris. There the sculptor has represented what must have actually taken place in the passage every day; on the one hand grooms leading their horses to water, on the other servants carrying up meat, fruit, and drink for the service of the royal table and for the army of officers and dependants of every kind that found lodging in the palace.[254]

This active desire to imitate reality as faithfully as possible had another consequence. It led to the multiplication of figures, and therefore to the diminution of their scale. No figures like those that occupy the whole heights of the slabs at Nimroud and Khorsabad have been found in the palace of Sennacherib. In the latter a slab is sometimes cut up into seven or eight horizontal divisions.[255] The same landscape, the same people, the same action is continued from one division to another over the whole side of a room. The subjects were not apportioned by slabs, but by horizontal bands; whence we may conclude that the limestone or alabaster was chiselled in place and not in the sculptor’s studio.

We have not engraved one of these reliefs in its entirety; with its half-dozen compartments one above another and its hundred or hundred and fifty figures, it would have been necessary to reduce the latter to such a degree that they could only be seen properly with a magnifying glass. The originals themselves, or the large plates given by Layard in his Monuments, must be consulted before the dangers of this mode of proceeding can be appreciated. The confusion to which we have pointed as one of the cardinal defects of Assyrian sculpture, is nowhere more conspicuous than in the battle pictures from Sennacherib’s palace. It is, however, only to be found in the historical subjects. When the sculptor has to deal with religious scenes he returns to the simplicity of composition and the dignity of pose that we noticed in the reliefs of Assurnazirpal.

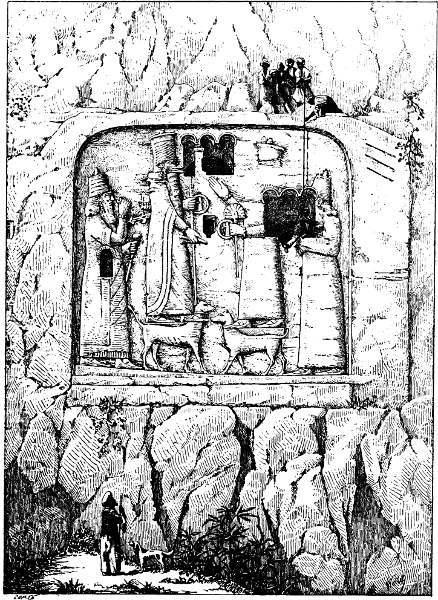

This may be seen in the figures carved on the rock of Bavian by the orders of Sennacherib. The village which has given its name to this monument lies about five and thirty miles north-north-east of Mossoul, at the foot of the first Kurdistan hills and at the mouth of a narrow and picturesque valley, through which flows the rapid and noisy Gomel on its way to the ancient Bumados, the modern Ghazir, which in its turn flows southwards into the Zab.

The sculptures consist of several separate groups cut on one of the lofty walls of the ravine. Some are accompanied by inscriptions, but the latter speak of canals cut by the king for the irrigation of his country and of military expeditions, and do not explain why such elaborate sculptures should have been carried out in a solitary gorge, through which no important road can ever have passed.[256]

The valley, which is very narrow, is a cul-de-sac. May we suppose that during the summer heats the king set up his tent in it and passed his time in hunting? According to Layard’s description the scene is charming and picturesque. “The place, from its picturesque beauty and its cool refreshing shade even in the hottest day of summer, is a grateful retreat, well suited to devotion and to holy rites. The brawling stream almost fills the bed of the narrow ravine with its clear and limpid waters. The beetling cliffs rise abruptly on each side and above them tower the wooded declivities of the Kurdish hills. As the valley opens into the plain the sides of the

limestone mountains are broken into a series of distinct strata, and resemble a vast flight of steps leading up to the high lands of central Asia. The banks of the torrent are clothed with shrubs and dwarf trees, among which are the green myrtle and the gay oleander bending under the weight of its rosy blossoms.”[257] Such a gorge left no room for a palace and its mound,[258] but a subterranean temple may have been cut in the limestone rock for one of the great Assyrian deities, and its entrance may now be hidden, or even its chambers filled up and obliterated, by landslips and falling rocks, and two huge masses of stone that now obstruct the flow of the torrent may be fragments from its decoration. They bear the figures of two winged bulls, standing back to back and separated by the genius who is called the lion-strangler.[259]

The principal relief fills up a frame 30 feet 4 inches wide and 29 feet high (see Fig. 120). The bed has been cut away by the chisel to a depth of about 8 inches. Sheltered by the raised edge thus left standing the figures would have been in excellent condition but for the unhappy idea that struck some one in later years, of opening chambers in the rock at the back and cutting entrances to them actually through the figures. These hypogea do not seem to have been tombs. They contain no receptacles for bodies, but only

F�� 120 The great bas-relief at Bavian; from Layardbenches. They were, in all probability, cells for Christian hermits, cut at the time when monastic life was first developed and placed where we see them with the idea of at once desecrating pagan idols and sanctifying a site which they had polluted. In Phrygia and Cappadocia we found many rock-cut chambers in which evidence of the presence of these pious hermits was still to be gathered. In some, for instance, we found the remains of religious paintings. As examples we may mention the royal tombs of Amasia, which were thus converted into oratories.[260]

The composition contains four figures. Two in the middle face each other and seem to be supported by animals resembling dogs in their general outlines. They are crowned with tiaras, cylindrical in shape and surrounded with horns. One of these figures has its right hand raised and its left lowered; his companion’s gesture is the same, but reversed. The general attitudes, too, are similar, but the head of one figure has disappeared, so that we can not tell whether it was bearded like its companion or not. They each carry a sceptre ending in a palmette and with a ring attached to it at about the middle of the staff. In the centre of this ring a small standing figure may be distinguished. Behind each of these two chief personages, and near the frame of the relief, two subordinate figures appear. In attitude and costume they are the repetition of each other. Their right hands are raised in worship, while in their left they hold short, ballheaded sceptres.

The two figures in the centre must represent gods. The king is never placed on the backs of living animals in this singular fashion; but we can understand how, by an easily-followed sequence of ideas, such a method of suggesting the omnipotence of the deity was arrived at. Neither did the kings of the period we are considering wear this cylindrical tiara. In the palaces of the Sargonids it is reserved for the winged bulls. It is larger than the royal tiara, from which it is also distinguished by its embracing horns. Finally, the ringed sceptre is identical with the one held by Samas, in the Sippara tablet (Vol. I. Fig. 71). No one will hesitate as to the real character of these two personages; the only point doubtful is as to whether the one on the left is a god or a goddess. The mantle worn

by the right hand figure is wanting; but the question cannot be decided, because the head has been completely destroyed. In any case, the difference of costume proves that two separate deities, between whom there was some relation that escapes our grasp, were here represented.

As for the two figures placed behind the gods, they would have been quite similar had they been in equally good condition. They represent Sennacherib himself, with the head-dress and robes that he wears in the sculptures of his palace at Nineveh. He caused his image to be carved on both sides of the relief, not for the sake of symmetry, but in order to show that his worship was addressed no less to one than the other of the two deities.

This rock-cut picture is not the only evidence of Sennacherib’s desire to leave a tangible witness of his piety and glory in this narrow valley. In another frame we find some more colossal figures, only one of which is fairly well preserved; it is that of a cavalier who, with his lance at rest, seems to be in act to charge an enemy. His attitude and movement recall those of a mediæval knight at a tournament. [261]

Layard counted eleven smaller reliefs sprinkled over the face of the rock. Some are easily accessible, while others are situated so high up that they can hardly be distinguished from below. Each of these has an arched top like that of the royal steles (see Fig. 116) and incloses a figure of the king about five feet six inches high. Above his head symbols like those on the Babylonian landmarks (see Figs. 43 and 111) and the Assyrian steles (Fig. 116) are introduced.[262] Three of these reliefs had inscriptions, and to copy them Layard caused himself to be let down by ropes from the top of the cliff, the ropes being held by Kurds who could hardly have had much experience of such employment. The illustration we have borrowed from his pages shows the adventurous explorer swinging between sky and earth (Fig. 120).

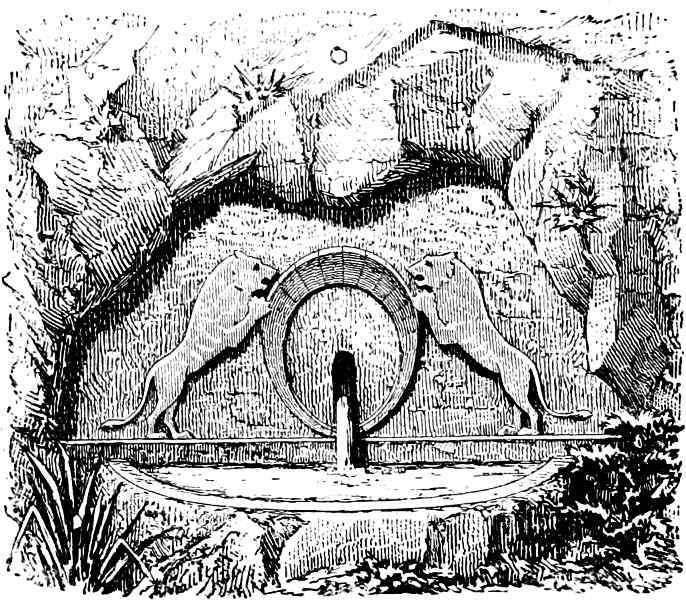

As a last example of these works cut in the rock, we may here mention a fountain that was cleared and for the moment restored to its original state by Mr. Layard (Fig. 121). By means of conduits cut

in the living rock, they had managed to lead the water of the stream to a series of basins cut one below the other. The sketch we reproduce shows the lowest basin, which is close to the path. The face of the rock above it is smoothed and carved into a not inelegant relief. The water seems to pour from the neck of a large vase, seen in greatly foreshortened perspective. Two lions, symmetrically arranged, lean with their fore-feet upon the edge of the vase.[263]

The work is interesting, as it is the only thing left to show how the Assyrians decorated a fountain.

F�� 121 —Fountain; from Layard

F�� 121 —Fountain; from Layard

The Assyrians thus found, in the very neighbourhood of their capital, great surfaces of rock almost smooth and irresistibly inviting to the chisel. Their unceasing expeditions led them into countries where, on every hand, they were tempted by similar facilities for wedding the likenesses of their princes to the very substance of the soil, for confiding the record of their victories to those walls of living rock that would seem, to them, unassailable by time or weather. Their confidence was often misplaced. In some places the water has poured down the face of the rock and worn away the figures; in others, landslips have carried the cliff and its sculptures bodily into the valley. In some instances, no doubt, the accumulations cover figures still in excellent condition, but several of these fallen sculptures have already been cleared.

F��. 122.

We have already spoken of the bas-relief of Korkhar;[264] it is about three hundred miles from Nineveh, but the Assyrian conquerors left traces of their passage even farther from the capital than that, in the famous pass of the Lycos, for instance, near modern Beyrout, and now called Nahr-el-Kelb, or river of the dog. A rock-cut road passes through it, which has been followed from the remotest times by armies advancing from the north upon Egypt, or from the latter country towards Damascus and the fords of the Euphrates. Following the Pharaohs of the nineteenth dynasty, Esarhaddon caused his own image and royal titles to be cut in this defile; they

Assyrian bas-relief in the Nahr-el-Kelb. Drawn by P. Sellier.may still be seen there, on rocks whose feet stand in the bed of the torrent (Fig. 122).[265]

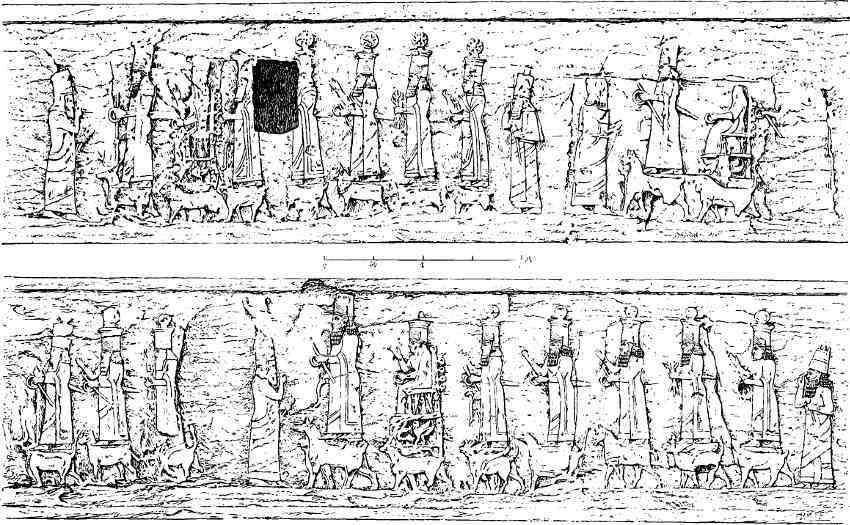

Without going so far as northern Syria we might find, if we may believe the natives of the country, plenty of sculptures in the valleys that open upon the Assyrian plain if they were carefully explored. Near Ghunduk, a village about forty-five miles north-west of Mossoul, Layard noticed two reliefs of the kind, one representing a hunt, the other a religious sacrifice.[266] But after Bavian the most important of all these remains yet discovered is that at Malthaï. This village is about seventy-five miles north of Mossoul, in a valley forming one of the natural gateways of Kurdistan. The road by which the traveller reaches Armenia and Lake Van runs through the valley. [267] There, in the fertile stretch of country that lies between two spurs standing out from the main chain, stands a tell, or mound, which seems to have been raised by the hand of man. Place opened trenches in it without result, but he himself confesses that his explorations were not carried far enough, and, the beauty of the site and other things being considered, he persists in believing that the kings of Assyria must have had a palace, or at least a country lodge, in the valley. However this may be, the bas-reliefs, of which Place was the first to make an exact copy, suffice to prove that this site attracted particular attention from the Assyrians (see Fig. 123). They are to be found on the mountain side, at about two-thirds of its total height, or some thousand feet above the level of the valley. In former days they must have been inaccessible without artificial aids. It is only by successive falls of rock that the rough zig-zag path by which we can now approach them has been formed. The figures, larger than nature, are arranged in a long row and in a single plane. Place was obliged, by the size and shape of his page, to give them in two instalments in the plate of which our Fig. 123 is a copy. In the absence of a protecting edge they have suffered more than the figures at Bavian. They have, indeed, a slight projection or cornice above, but its salience is hardly greater than that of the figures themselves.

The composition contains three groups, or rather one group repeated three times without sensible differences. The middle group, which is divided between the upper and lower parts in our woodcut, has been more seriously injured by the weather than those on each side of it; three of its figures have almost disappeared. The first group to the right in the upper division has part of its surface cut away by a door giving access to a rock-cut chamber behind the relief, like those at Bavian. It is, then, in the left-hand group that the subject and treatment can now be most clearly grasped.

In the first place, we may see at a glance that the theme is practically the same as at Bavian; it is a king adoring the great national gods. But the latter are now seven in number instead of two; instead of being face to face they are all turned in one direction, towards the king; but the latter is none the less repeated behind each group. There are some other differences. Among the animals who serve to raise the gods above the level of mere humanity we

F�� 123 The bas-reliefs of Malthaï; from Place About one forty-fifth of actual sizemay distinguish the dog, the lion, the horse, and the winged bull. The gods are in the same attitude as at Bavian; their insignia are the same, those sceptres with a ring in the middle, which we never find except in the hands of deities. The sixth in the row also grasps the triple-pointed object that we have already recognised as the prototype of the Greek thunderbolt.[268] Finally, each god has the short Assyrian sword upon his thigh. To this there is one exception, in the second figure of each group. This figure is seated upon a richly-decorated throne, and has no beard, so that we may look upon it as representing a goddess. The last of the seven deities is also beardless, and, in spite of the sword and the standing attitude, may also be taken to represent a goddess. The tiaras, which are like those of Bavian in shape, each bear a star, the Assyrian ideogram for God. [269]

There is no inscription, but both Place and Layard agree that the proportions of the figures, and their execution, and the costume of the king, declare the work to have been carried out in the time of the Sargonids, probably under Sennacherib, but if not, during the reign either of his father, his son, or his grandson.

We have been led to give a reproduction and detailed description of these reliefs, chiefly because they acted as a school for the people about them. We find this habit of cutting great sculpturesque compositions on cliff-faces followed, on the one hand by the natives of Iran, on the other by those of Cappadocia, and in the works they produced there are points of likeness to the Assyrian reliefs that can by no means be accidental. When the proper time comes we shall, we believe, be able to show that there was direct and deliberate imitation.

It was not only on these rock-cut sculptures that the gods appeared thus perched on the backs of animals; the motive was carried far afield by small and easily-portable objects, on which it very often occurs. It is to be found on many of the cylinders; we