Magazine of Haverford College

Magazine of Haverford College

How Haverford’s extraordinary strength in astronomy is powering an unprecedented survey of the cosmos

• The Fords Making Transit Make Sense • The Kim Institute Brings the Heat

Editorial Director

Dominic Mercier

Editor

Brian Howard

Class News Editor

Mara Miller Johnson ’10

Copy Editor

Colleen Heavens

Photographic Director

Patrick Montero

Graphic Design

Anne Bigler

Vice President for Marketing and Communications

Melissa Shaffmaster

Associate Vice President for College Communications

Chris Mills ’82

Vice President for Institutional Advancement

Kim Spang

Contributing Writers

Shaunice Ajiwe

Eric Butterman

Emma Copley Eisenberg ’09

Charles Curtis ’04

Sari Harrar

Lini S. Kadaba

Patrick Rapa

Ben Seal

David Silverberg

Contributing Photographers

Holden Blanco ’17

Steve Magnotta

Paola Nogueras

Mac Sanders ’24

Contributing Illustrator

Melissa McFeeters

Haverford magazine is published three times a year by Marketing and Communications, Haverford College, 379 Lancaster Avenue, Haverford, PA 19041, 610-896-1000, hc-editor@ haverford.edu © 2025 Haverford College

SEND ADDRESS

Advancement Services

Haverford College 370 Lancaster Avenue Haverford, PA 19041 or devrec@haverford.edu

26 Tell Us More

Jason Patlis ’85: The Life Aquatic By

Eric Butterman

28 From Haverford to the Stars

Fords have long played an outsized role in studying the cosmos. Now, that includes contributions to the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time—the world’s most ambitious survey of the universe. By Sari

Harrar

As artificial intelligence permeates society, many in the Haverford community are working to figure out what role—if any—it should play in higher ed. By

Lini S. Kadaba

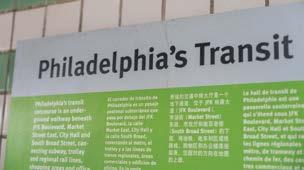

42 Easy Riders

Philadelphia’s public transportation system has long had a reputation for being confusing and difficult to navigate. Two Fords are on a mission to change that. By Ben Seal

42 Detail of a new, Ford-powered wayfinding system for Philadelphia transit

during 2025

As another Ford living with Parkinson’s disease, I was particularly pleased by the last cover story, “Building a New Brain Trust: How one alum’s journey with Parkinson’s disease is fueling ethical inquiry in Haverford’s blossoming neuroscience program” (Spring/Summer 2025). The alum in question, Shamir Khan ’96, has funded a fellowship in neuroscience at the College, a marvelous new program that will lead to increased knowledge of the way Parkinson’s develops, its causes, and, hopefully, better and more effective treatments. The article, by Dominic Mercier, struck just the right balance between the depressing and seemingly intractable nature of Parkinson’s and hope for the future in terms of ending this miserable, demoralizing illness. Congratulations to the magazine for focusing on the promise of the end of Parkinson’s, and a hearty thanks to Shamir Khan for turning his own personal tragedy into a positive development at Haverford.

—Ed Sikov ’78

Thanks for Dominic Mercier’s article “Building a New Brain Trust.” I don’t ever remember seeing anything about Parkinson’s disease before in the alumni magazine. Kudos to Shamir Khan and all Fords navigating and studying PD. I was diagnosed at age 50 and am grateful to know of the College’s work in this field. I am particularly curious about one of the lesser-known symptoms, dystonia, which I have.

—Shannon Slater ’91

I enjoyed reading the latest edition of the alumni magazine but was disappointed to see that the Sneetches were not included in “Fords for the Win” (Curran McCauley, Spring/Summer 2025), the highlight reel for sports accomplishments for the 2024–2025 academic year.

in Division III who are selected by their peers. This award is the highest honor in ultimate for a D-III college player, and Zoe is the first recipient from the Sneetches.

—Christina Herold ’97

Ask a question or offer a comment on one of our stories. Tell us about what you like in the magazine, or what you take issue with. If your letter is selected for publication, we’ll send you a spiffy Haverford College coffee mug.

Email: hc-editor@haverford.edu

Or send letters to: Haverford magazine

Marketing & Communications Haverford College

370 Lancaster Ave.

Haverford, PA 19041

The Sneetches are Haverford and Bryn Mawr’s Bi-Co ultimate frisbee team. They play in the women’s division, but it is noteworthy that the team is open to all marginalized genders, including women, nonbinary people, and trans men.

In the spring, the Sneetches competed in the Women’s Division III College Championship and they came in second, falling to Wesleyan’s Vicious Circles. This was not their first appearance at the D-III College Championship tournament, but I believe that it was the first time that they advanced to the final game.

Also of note is that team captain and senior Zoe Costanza BMC ’25 won the Donovan Award for 2025. The Donovan Award is awarded annually to one women’s and one men’s player

The editor responds: You’re absolutely right. The Sneetches had an incredible season, and Zoe’s recognition is a big moment for the team. Because of space limitations and our production timeline, we made the difficult choice to feature only varsity sports in that particular piece. But the Sneetches’ achievement is undoubtedly worthy of recognition. See the inside back cover for more.

In the Spring/Summer 2025 issue, a note about the incoming Class of 2029 stated that Haverford was welcoming students from Ecuador for the first time. That was incorrect, as pointed out by Christopher Dunne ’70, who notes that his classmate Johnny Czarninski ’70 arrived at Haverford from Ecuador in 1966.

This year’s Design + Make Fellowship encouraged participants to explore our deep relationship with textiles.

BY SHAUNICE AJIWE

Design + Make Fellowship co-leads Manasi Eswarapu and Kent Watson (center) with, from left, fellows Eliza Duff-Wender BMC ’27, Maia Roark ’25, Zora Kuehne ’28, and Mary-Grace Culbertson BMC ’25.

Many of us don’t consider the role that fabric plays in our daily lives beyond, perhaps, laundry day or the latest landfill-clogging fast-fashion trend. But an increasing number of younger people are seeking a more hands-on, inquisitive experience with the world of textiles. This summer, four students who participated in the Design + Make Fellowship through Haverford’s Visual Culture, Arts, and Media (VCAM) facility got one.

The annual eight-week program at VCAM’s Maker Arts Space focused this year on textile art, and immersed the fellows in a variety of techniques, from popular crafts like crochet and sewing to intensive practices like dyeing and felting.

“What’s exciting about Maker Arts Space is that it’s this space where creativity and utility

exist next to each other,” says Kent Watson, co-lead of the fellowship and VCAM’s maker arts, education, and programs manager. “We are playing and making art, and at the same time, engineering and designing and prototyping things. It’s so valuable to do that thing that art does, where it has these bursts of creativity, of making, while we’re learning these skillsets that are really used in industries.”

This year’s fellowship came together, Watson explains, with the help of co-lead and Hurford Center for the Arts and Humanities Post-Baccalaureate Fellow Manasi Eswarapu. A regular face at the Maker Arts Space, Eswarapu began leading a weekly workshop called Weaving Wednesdays last spring. Based on students’ interest in not only that, but in thrifting, upcy-

cling, and environmentalism as well, the subject of this round of the program quickly took shape.

“I think there’s this notion that hobby is a very unserious thing,” Eswarapu says. “I wanted to push them to see how much engaging in crafts could connect them with other people around the world and also with our past. These are really old techniques that have existed for centuries, and they become part of a larger history by engaging with them.”

The fellowship has tended to revolve around tangible subjects, such as chairs or toys. Watson emphasizes the opportunity for students to think deeply about the “built and designed world” and how it can be improved upon. The fellows heard from visiting lecturers on knitting patterns and designing for disability, took a trip to Thomas Jefferson University’s archive to study historical garments, and visited an alpaca farm to learn about sustainable production using their wool.

“I often don’t have time to do creative things, so this was nice to be able to do that and kind of expand my life out in terms of creativity and actual physical work,” says fellow Eliza DuffWender BMC ’27, a political science major.

It all led up to a Friday in late July, when the Maker Arts Space was transformed into a gallery displaying the fellows’ final projects—four new textile creations with a practical element, each involving skills learned throughout the summer.

For Duff-Wender’s project, over the course of two and a half weeks she crafted a protest banner incorporating a traditional Palestinian embroidery technique called tatreez. Another project—a knit cape designed by Maia Roark ’25, a history major—was inspired by foliage in the Haverford area. The others were a dinosaur-themed weighted blanket by Zora Kuehne ’28, a prospective English and psychology double major, and a set of woven placemats colored with natural dyes by MaryGrace Culbertson BMC ’25, a history of art major.

“What is so special to me about textiles is that anyone can do it,” Culbertson says. “Whatever you want to call it, outsider art, amateur art, folk art—it is a powerful form of art.”

The July gathering was a lively and tactile one, with all four projects and their materials laid out to touch and lift to see closer. Many interactive elements were incorporated, such as a yarn winder, a loom, and an indigo dyeing station.

As for the future of their pieces, the fellows plan on keeping them and, ideally, incorporating them into their daily lives. The same goes for the abilities and new perspectives on textiles that they gained during the fellowship. “I know that this creation is going to remain a big part of my life,” says Kuehne. “I still haven’t really decided what I want to do [professionally], but I do know that as I get older, I’ll probably find a way to use these skills and contribute to a community.”

CURBING FOOD WASTE Through a self-designed summer experience supported by Haverford’s Center for Peace and Global Citizenship, environmental studies major Darren Belanger ’26 worked with Philadelphia nonprofit Sharing Excess to divert tons of edible but cosmetically imperfect food from the landfill to families in need. For Belanger, this connects directly to issues of sustainability while also reinforcing his professional aspirations: “I want to do good work. If I stay late, it’s because my work will be positively affecting the community, not just the company.”

Small but Mighty A new study published by the Association of Independent Colleges and Universities of Pennsylvania confirms what Fords already know: the College punches well above its weight economically. In 2023, Haverford contributed an estimated $233.6 million to the state’s economy, an outsized imprint for a college with fewer than 1,500 students. That impact—factoring direct spending and demand for goods and services—supported 1,556 jobs across sectors from dining and retail to healthcare, and generated $18.7 million in state and local tax revenue.

Jory Lee ’26 and close friend Hudson Rha, a junior at Case Western Reserve University, are tackling what many of us feel but don’t name: post-travel depression. Their answer is Traverse, a scrapbooking app that helps users relive their journeys. Born from a project in Visiting Assistant Professor of Visual Studies Ronah Harris’ “Design for All” course and shaped at the Haverford Innovations Program’s Summer Incubator, Traverse lets you upload photos and journal entries and pin them to an interactive map.

Political science major Holly Vincent ’26 is turning her curiosity about civics into action as Haverford’s newest Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress Fellow. The national program brings undergrads to Washington, D.C. to study leadership and policy. Vincent's project will explore how the media influences public perception of presidential debates. On campus, she’s put civic engagement into practice, having founded the 2024 Tri-Co Voting Challenge, which inspired some 700 consortium students to pledge to vote.

Suzanne Amador Kane’s biomechanics lab, spiders are helping Fords uncover the secrets of movement and resilience. Using high-speed cameras and machine learning, Kane and her team of student researchers are studying how spiders adapt when faced with injury or complex terrain. Their findings show that even after losing a leg, which can result from a poor molt, predator attack, or becoming stuck in a crevice, spiders adjust their gait to stay quick and steady. This feat could inspire advances in robotics and prosthetics design.

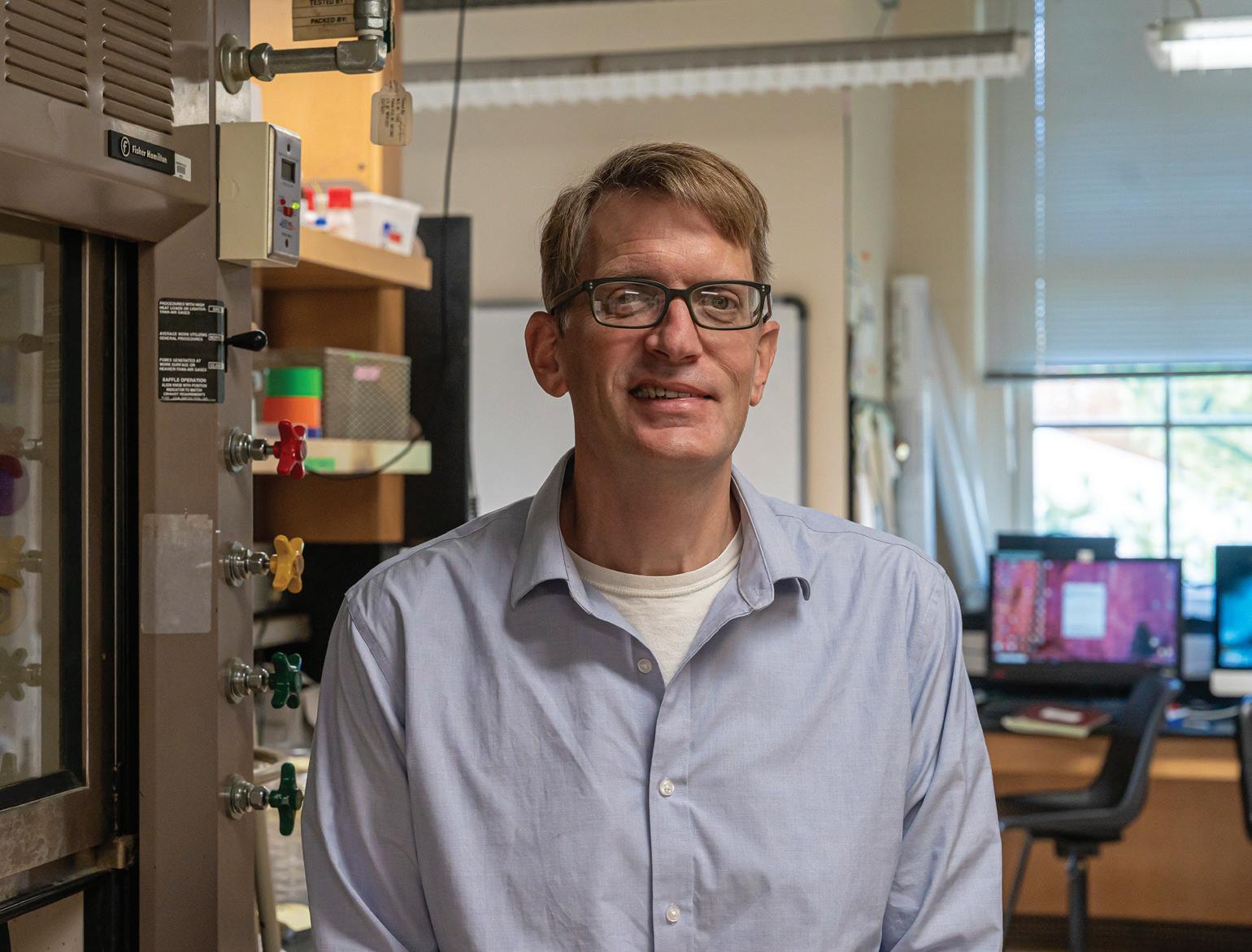

From the Ocean to Your Medicine Cabinet The search for better human health has led researchers to unlikely places, but few are as unexpected—or as promising—as the microscopic world that surrounds phytoplankton in the ocean. That’s where Associate Professor and Chair of Biology Kristen Whalen (below, left) and Post Doctoral Investigator Amanda Platt are focusing their efforts, thanks to a three-year, $442,710 grant from the National Institutes of Health. In the search for therapeutics to aid in the fight against drug-resistant bacteria, Whalen, Platt, and the Haverford students they work with are focused on a marine bacterium called Pseudoalteromonas sp. A757

Associate Provost for Faculty Development and Professor of Political Science Craig Borowiak is using data to enact grassroots change. With Beyond Land Precarity, a project backed by the William Penn Foundation, he’s mapping, documenting, and protecting Philadelphia’s vast network of community gardens. The project, which he is co-leading with Villanova University Associate Professor of Geography and the Environment Peleg Kremer, will build an interactive database that tracks land ownership and highlights at-risk sites, arming gardeners with the tools they need to advocate for long-term stability for their pockets of green space.

Fords in Fiction Keen-eyed viewers may have spotted Mark Ruffalo’s character, Tom Brandis, sporting a Haverford College T-shirt while gardening during the closing moments of HBO’s prestige drama Task in mid-October. The series comes from Philadelphia-area writer and producer Brad Ingelsby, whose Mare of Easttown famously brought the joy that is the Delco accent to the wider world. We’re still waiting to hear whether Tom is a Haverford admirer or an official Ford. If he is, he’ll join the pantheon of fictional Haverford alums that includes Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan, Twin Peaks), Cal McAffrey (Russell Crowe, State of Play), Astrid Farnsworth (Jasika Nicole, Fringe), and Brian Callahan (Jonathan Franzen’s 2001 novel The Corrections).

Haverford has planted the seed for a holistic culture of well-being on campus thanks to a generous gift from Carolyn Risoli P’24 and Joe Silvestri P’24. Their earlier support funded the GameTime THRIVE 900 outdoor fitness installation (aka the “adult playground”) between the Gardner Integrated Athletic Center (GIAC) and Whitehead Campus Center. Now, the newly established Risoli-Silvestri Holistic Student Wellness Endowment Fund will sustain mental and physical health initiatives in an ongoing way. Risoli and Silvestri’s vision isn’t to prescribe onesize-fits-all fixes, but to empower Haverford’s experts to respond to student needs dynamically.

A Heavy Hitter With a .428 batting average, 23 home runs, 77 RBIs, and a 1.034 slugging percentage, Harry Genth ’25 dominated Division III baseball last year. After his record- shattering senior season earned him four NCAA statistical titles, Genth signed as an undrafted free agent with the Minnesota Twins organization, where fellow Ford Jeremy Zoll ’12 is general manager. Genth’s rise from small-college stand out to professional ballplayer was anything but easy, but he’s become the seventh Haverford alum to ink an MLB contract.

In the intensity of the Flaherty Seminar, Haverford students grapple with questions of truth, ethics, and the power of film.

BY BEN SEAL

hen Aby Isakov ’24 arrived at the Flaherty Film Seminar in New York in June 2023, she was ready to be surprised. The weeklong gathering of artists, scholars, programmers, and film enthusiasts has developed a reputation over its 70 years as an intense and illuminating exploration of documentary film in all its forms.

WJohn Muse leads a sound recording workshop with students in his “Capstone for Visual Studies Minors” class in the Visual Culture, Arts, and Media facility.

For the past decade, John Muse, assistant professor and director of the visual studies program at Haverford, has been involved in bringing two students each year to the seminar, where they participate in screenings and discussions that probe the deepest corners of documentary film. Haverford’s participation was initiated by Vicky Funari, Muse’s wife and a fellow visual studies instructor at the time. The students are typically accompanied by Muse and a Haverford faculty and staff member.

“Everything that’s compelling and weird about telling true stories—whatever that might

mean—is on display there,” Muse says.

Isakov, a filmmaker who graduated with an independent major in visual studies, found herself surrounded by 150 equally curious minds, all eager to engage with the work and with one another in conversations about the form, function, theory, and practice of documentary filmmaking. Isakov was brimming with questions and practically jumping out of her seat to ask them. And although the Haverford students at Flaherty are typically its youngest participants, she joined in the discussions, alongside directors and other industry veterans. Given the connection she felt to the films being shown, from Barbara Hammer’s pioneering forays in queer cinema to Theo Jean Cuthand’s explorations of the effects of resource extraction on Indigenous cultures, she had little choice.

“The films at Flaherty physically, viscerally, mentally, and emotionally move you,” Isakov says. For Muse, seeing students participate in an experience often reserved for their elders is the great appeal of the Flaherty. After he and Funari were each invited to attend as artists years ago, they began returning annually with Haverford students and staff. He describes the Flaherty as “mind-expanding, world-expanding, and profession-expanding,” an opportunity for students to fully immerse themselves in nonfiction film culture for a week. The theme of the seminar changes each year—2023 was focused on “Queer

World-Mending,” and this year’s one-word title, “Onward!” oriented the seminar both to its legacy and to its future—but every iteration features dozens of screenings of unannounced films.

When students return to campus, they’re asked to curate a fall screening open to Haverford and the broader community, which Swagnita Das ’28, who attended this summer’s seminar, calls a “mini Flaherty.” Das was inspired to apply to the seminar after taking a spring course focused on documentary cinema, which gave her a taste of the deeper discussions that happen at Flaherty. By watching films about environmental, social, and gender injustice, she learned to tangle with the complex feelings documentary cinema can stir up.

“Going into Flaherty, I was equipped. If I’m feeling uncomfortable with something I’m watching, it’s not enough to just say I’m uncomfortable,” Das says. “You have to sit with that and explore what made you so uncomfortable.”

Considering the “pressure-cooker” atmosphere Muse describes at the Flaherty, he’s deliberate about the kinds of students he brings, ideally those who can sustain their curiosity and inspiration over the course of a rigorous week. It helps, he says, that Haverford students tend to be well prepared by on-campus explorations of the issues that arise at the seminar, including “what it means to make a better world.” The overlap between the two institutions’ missions is nearly one-to-one, he says. “The Venn diagram is just a unity.”

For Isakov, the seminar turned out to be just as surprising as she expected. It taught her to grapple with documentary film and the context in which it’s created, as well as how to synthesize her varied responses in search of a deeper understanding. In many ways, she says, it felt like a continuation of the work she’d been doing at Haverford all along.

“We’re always thinking about who we are, our place and situation,” Isakov says. “We’re constantly trying to contextualize ourselves in the larger world, understanding we’re in a bubble, but we have to reach outside of that. It’s a good foundation for experiencing something like the Flaherty.”

As Muse sees it, the seminar is a reminder that critical thinking about how to live and work ethically carries on outside of academia, particularly among those who believe in the power of persuasive media and the beauty of image-making.

“There’s a place where what we’re striving to do here at Haverford goes on and doesn’t stop when you graduate,” he says.

“Site Work: The Art of the Table Read”

This practicum-style English course invites students to analyze and perform screenplays, revealing how film storytelling takes shape through collaboration, performance, and interpretation.

In Visiting Assistant Professor of English J. Felix Gallion’s hands-on course, students explore the table read as a site of creative experimentation and literary analysis. Blending elements of screenwriting, directing, and acting, the class invites students to dissect and perform scenes from popular films.

Tell us about your class. What do you hope students will take from it?

A table read is the moment a film cast and crew get together and read the entire film script from front to back. We focus on the table read as a specific site where story, dialogue, and performance are workshopped and refined, and where everyone in a film’s production does some form of literary and performance analysis in order to do their job on set.

The class is structured as a practicum, or a class focused on gaining specific skills based on observation and practice. Students learn the fundamentals of screenwriting, acting on screen, and directing through studying and performing scenes from three films: Jordan Peele’s horror magnum opus Get Out, John August and Daniel Wallace’s fantasy Big Fish, and Rachel Sennott and Emma Seligman’s hit high-school comedy, Bottoms.

My hope is that students will take away an understanding of how films are made, the importance of narrative theory to the film production process, and practical skills for a career in the industry.

Why did you want to teach this class? What drove you to create it?

The first line of the syllabus says, “This course is what happens when a theater kid gets a Ph.D. in English.” I went to film school as an undergrad, and my interest in English was always about finding unique ways to tell stories.

As a scholar, filmmaker, and performer, I wanted to create a class where students could learn about storytelling, TV and film production, and performance simultaneously. For me, all of these things come together at the moment of a production’s table read, the moment when everyone involved in telling a movie’s story gets together to work out the details.

What makes your course unique to the English Department?

The class is unique in approaching screenplays themselves as literary texts for analysis. Literary studies love to analyze theatrical plays and experimental literature, but the screenplay as a piece of literature is left to the wayside. This class tries to change that perspective by showing that the form of a screenplay is the most literary of works by allowing many different kinds of people with different artistic and technical jobs to collaborate through individual and collective interpretation. I think it’s also unique in that the class is very much about embodiment and actively exploring a written story through performance. There is a lot of doing and a lot of play, as all of our analysis gets translated into the final table read performances. —DM Cool Classes is a recurring Haverblog series. More at: hav.to/coolclasses.

The College welcomes four new tenure-track faculty members whose teaching and research strengthen Haverford’s commitment to interdisciplinary scholarship and global perspectives.

Assistant Professor of Political Science

Vatsal Naresh specializes in democratic theory, political violence, and constitutionalism. His current book project develops a new theory of majoritarian domination by interpreting the writings of Alexis de Tocqueville, W. E. B. Du Bois, and B. R. Ambedkar.

Naresh’s scholarship includes a recent article in the American Political Science Review and co-edited volumes such as Negotiating Democracy and Religious Pluralism: India, Pakistan, and Turkey (Oxford University Press, 2021) and Constituent Assemblies (Cambridge University Press, 2018). Before joining Haverford, he taught in Harvard University’s Social Studies program from 2022 to 2025. He earned his Ph.D. in political science at Yale University, studied political science at Columbia University, and completed his undergraduate degree in history at Delhi University.

SWETHA REGUNATHAN

Assistant Professor of Visual Studies

A Philadelphia-based filmmaker and writer, Swetha Regunathan creates character-driven fiction films that explore themes of nostalgia, longing, and shifting identities. Her work frequently engages hybrid docuforms and mixed-media techniques to expand the on-screen representation of South Asian Americans. Regunathan holds a B.A. in English from Columbia University, an M.A. and Ph.D. in English from Brown University, and an M.F.A. in film production from New York University (NYU).

Her feature film Burnout was selected for both the 2023 NYU Purple List and the NYU Production Lab Development Studio, while her screenplay Sundarbans was developed in the Cine Qua Non Storylines Lab and the inaugural 1497 South Asian Writers Lab. She produced Between Earth and Sky, which was shortlisted for a 2023 Academy Award for best documentary short subject, and her short films have screened at Tribeca, Aspen Shortsfest, True/False, and other prestigious venues. Regunathan has also been recognized with awards from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Peter S. Reed Foundation, and the BlueCat Screenplay Competition.

YIMING WANG

Assistant Professor of Chemistry

Yiming Wang discovered a passion for nanoscience while completing her Ph.D. at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Captivated by the beauty of nanocrystals under the electron microscope and their unique properties at the nanoscale, she has since built a career at the forefront of materials chemistry.

Wang previously held postdoctoral appointments at Harvard University and at Boston University. Her teaching experience includes labs in analytical chemistry. At Haverford, she is currently teaching Superlab, an inquiry-based lab course for junior science majors, and will engage students in projects at the intersection of nanomaterials, catalysis, and biomedical innovation.

The William H. and Johanna A. Harris Professor of Environmental Studies and Entrepreneurial Studies

A longtime member of Haverford’s community, Talia Young previously served as a visiting assistant professor of environmental studies before stepping into her new role. Young’s scholarship has traced aquatic food webs from New Jersey to Mexico to Mongolia, examined adaptation and resilience among northeastern U.S. fishing communities confronting climate change, and explored the broader implications of alternative seafood supply chains, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Young is also the founder and director of Fishadelphia, a Philadelphia-based community seafood program that connects diverse families with regional seafood producers. Young’s co-authored publications with Haverford students and alumni highlight the impact of inclusive practices in alternative food programs and shifts in seafood consumption habits. Her teaching covers cultural foodways, fisheries modeling, and community impacts of seafood. Young earned her B.A. at Swarthmore College, her teaching certification at the University of Pennsylvania, and her Ph.D. in ecology and evolution from Rutgers University.

Trash to Treasure: A new composting system near the Haverfarm is transforming up to 2 cubic yards of organic waste collected at the Haverford College Apartments into batches of nutrient-rich soil for the farm and Arboretum. Proposed by Claire DuBois ’22, Ally Edwards ’22, and Ellie Kerns ’22 as part of their environmental studies capstone, the project is supported by a gift from Douglas Johnson ’71.

Spotlighting the holdings of Quaker and Special Collections

A humble funerary urn recalls an elaborate and controversial late-19th-century campus ritual.

In the College’s Quaker and Special Collections sits a curious funerary artifact: a small, dark cremation urn that holds the remains not of a person, but of a book. The vessel is the final resting place for a copy of William Paley’s A View of the Evidences of Christianity , a dense two-volume treatise on the foundation of Christianity first published in 1794. For many Fords in the late 19th century, it was a book synonymous with academic tedium.

IFrom the 1860s through the late 1880s, sophomores ended each academic year with a somber tradition: the ceremonial cremation of their least favorite textbook. Paley’s Evidences received the dubious honor of “most hated” text for many years until, as one chronicler notes, “it was difficult to defend a Quaker College burning the book which was supposed to safeguard the faith.” Eventually, Paley’s theological writings gave way to more practical victims, and mathematics textbooks by Henry Nathan Wheeler and George Wentworth were later sent to their ashen rest.

But the cremation ceremony was neither crude bonfire nor cen-

sorial book burning. It allowed students to channel scholastic misery through an elaborate ritual complete with professionally engraved invitations, costumes, and choreographed proceedings akin to a state funeral. After a procession into the woods, the students would condemn and defend the text—typically in Latin—before sentencing it. As the flames consumed the tome, classmates would sing exaggerated hymns of mourning. The practice became so popular that it was relocated from the woods to the front of Barclay Hall, allowing a larger audience, many of whom dressed in costume, to witness the spectacle.

Haverford and its community, of course, have long revered books, so this playful tradition wasn’t amusing to all. Worried that the rite sent the wrong message about scholarship and the College itself, President Isaac Sharpless banned the practice, and the last recorded ceremony was held in June 1889. This urn, however, remains as final witness to the end-of-the-century tradition and serves as a reminder that the voice of students—however subversive or satirical—has always been integral to the College’s history.

—DM

Throughout the academic year, the Michael B. Kim Institute for Ethical Inquiry and Leadership confronts the human cost of a warming world. BY

DOMINIC MERCIER

When temperatures soared above 100 degrees and broke historical records in Philadelphia this summer, Shalae Clemens BMC ’27 couldn’t help but think about home. The Tempe, Ariz., native has seen firsthand how relentless heat shapes daily life. It’s not uncommon, for instance, for their father to return home from his job cleaning swimming pools with hands blistered from handling hot metal tools.

Now, as a Bi-Co environmental studies major, they are determined to make heat the focus of their career. “It’s not an opinion anymore because the science is there,” Clemens says of climate change. “What has been lacking is the ability to apply the science and make real change based on it. That’s really what I’m passionate about.”

Their growing interest in the ethics of climate change found a natural home at Haverford’s newest academic hub, the Michael B. Kim Institute for Ethical Inquiry and Leadership, where the inaugural programming theme for

the 2025–26 academic year is extreme heat. Established in 2024 through a transformative $25 million gift from Board Chair Michael B. Kim ’85 P’17, the institute is a central component of Haverford 2030, the College’s strategic plan.

For Associate Professor of Anthropology and Environmental Studies and faculty fellow Josh Moses, who co-leads this year’s institute programming with Assistant Professor of Health Studies Anna West, heat offers a unique venue to explore individual and systemic ethics. “It’s one lens to view many other social and environmental problems that we’re facing,” Moses says. “And it’s one that I think most of us feel viscerally.”

Jill Stauffer, associate professor of Peace, Justice, and Human Rights, who serves as one of the institute’s two faculty advisors alongside Professor of Computer Science Sorelle Friedler, sees the ethical potential in heat’s immediacy. Everyone is impacted by human-caused climate change and the instabilities it causes, especially students, whose futures will be irrevocably shaped by it.

“It also connects to so many other areas of ethical import: inequality, migration, conflict, health, resource management, and so on,” Stauffer says. “Heat seemed like a great way to show that ethical concerns are not abstract.”

The stakes of climate change are undeniable. According to the World Health Organization, extreme heat was responsible for the deaths of approximately 489,000 people worldwide between 2000 and 2019. A 2023 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report found more than 2,300 Americans died that year from heat-related causes, the highest number ever recorded. The effects of heat often land unequally: tree cover, infrastructure, and access to cooling frequently align directly with race and income.

For environmental studies major Makayla Coleman ’26, those disparities hit close to home. Coleman’s mother, a longtime U.S. Postal Service worker in rural North Carolina, has been hospitalized for heat stroke while delivering mail. “We need to protect our workers,” Coleman says. “The USPS has a motto of delivering the mail no

Continued on p. 14

After spending nearly 15 years advancing U.S. international development goals around the world, Maura O’Brien ’05 has returned to Haverford to serve as coordinator for the Michael B. Kim Institute for Ethical Inquiry and Leadership. A former foreign service officer with U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), O’Brien brings a global perspective on ethics, resilience, and collaboration. Here, she reflects on lessons learned from development and diplomacy work around the globe and how she hopes to inspire Haverford students to confront the ethical and environmental challenges of a rapidly warming world.

Welcome back to Haverford, Maura. How do you think your impressive background with USAID will influence your approach to building the Kim ethics institute’s programs and partnerships? Working closely with individuals and institutions with significant political power has driven home for me the importance of maintaining a strong commitment to my values. I see the Kim ethics institute supporting Haverford students as they grow in their commitment to their own values and learn to rely on them as they navigate the world.

9/11 happened at the very start of my first year here. That horror, the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and the assault on civil liberties and human rights all fundamentally shaped my worldview. Long before I could have articulated my personal belief in the importance of ethical leadership, I felt its absence and understood the resulting catastrophic consequences.

Why is it important for Haverford’s students to engage with the concept of heat, the institute’s inaugural theme, through an environmental and ethical lens?

As a country, we’re abandoning our global leadership role in creating a safer, greener, more sustainable future. The world is desperate for a new generation of leaders, and that vacuum presents space for any Haverford student looking for meaningful ways to engage with some of the planet’s most urgent problems. Heat is a particularly compelling way to think about climate change because it highlights one of the ways the climate crisis ex-

acerbates inequality: The most vulnerable people and communities are the hardest and first hit by rising temperatures and sea levels.

How have your work with USAID and your Haverford experience shaped your understanding of ethics and leadership?

Working in a wide variety of contexts has taught me that what most people want from their leaders in a practical way is pretty universal. When I first started supervising team leaders, it was almost two decades ago, working with and for people experiencing homelessness in Philadelphia. I had no idea what I was doing, but I started from the basis of explaining that teams need their leaders to be principled, predictable, and pleasant. I was relying on the alliteration as much as I was on any real professional expertise.

During my last overseas post with USAID in Pakistan, I found myself using the same concepts. One of the women I worked with made the excellent suggestion of adding accessible to the list. As elementary as “principled, predictable, pleasant, and accessible” may sound, that list has served me well because, as a leader, you always want to foster an environment where people feel safe, respected, and engaged so that they can grow in their work and their own leadership.

What lessons do you hope to pass on to students?

When I interviewed for a job with Project HOME in Philadelphia, I had been working at another nonprofit for less than a year. I worried that leaving a job I’d had for less than a year would break some kind of professional norm. The two people from Project HOME who I would report to were my interviewers, and after spending just a couple of minutes together, I realized that getting to work with them was more important to me than anything else because of how much just watching them in action could teach me. That was about 19 years ago, and they are now both among my closest friends.

Similarly, I left a comfortable overseas post to follow the USAID mission director I was working for first to Iraq, then to our West Bank and Gaza mission—nearly entirely because I loved the way she treated other people. So if I have one piece of advice, it would be to make space in your life for the best people you meet. —DM

WHAT: The Haverford Climbing Club is a student-run organization perfect for Fords looking to give indoor rock climbing a try, experienced gym rats wanting to scratch the climbing itch, and anyone in between. Climbing can be cost-prohibitive, but thanks to funding from Student Life , the club covers gym passes, equipment rentals, and even transportation. No carabiners or specialized knowledge are required. The club has created a welcoming, low-pressure environment for students to test out a new sport, gain a bit of confidence, and, for many, discover a lasting hobby. “We emphasize that you don’t need any experience, you don’t need to pay for any of your equipment or for the day pass for the gym,” says club co-leader Harrison West ’26. “Just show up with your friends and try out a new fun activity.”

WHERE: Club outings are held in nearby Radnor at the Gravity Vault, a gym known for inclusivity and attracting supportive climbers. “The Gravity Vault, in particular, has a really special community,” West says of the gym’s focused programming, which features options like LGBTQIA+ meetups and weekly climbing events for those with Parkinson’s disease. “That’s a

Continued from p. 12

big part of why this club’s able to promote community the way it does. The gym really fosters that.” The 16,000-square-foot facility offers climbers nearly 100 different roped routes that reach heights as high as 40 feet, as well as options for bouldering, a less gravity-intensive form of climbing that doesn’t require safety gear.

WHEN: During the academic year, the club runs three trips for up to 12 students to the Gravity Vault every week, though the club takes breaks for holidays and finals. “Our purpose is very simple,” says co-leader Nora Salem ’26, who discovered her own interest in climbing through the club. “We have one goal, and that’s to get people to climb.”

matter the weather. I think that might be an outdated motto.”

With support from the institute, Coleman spent this summer researching occupational heat exposure, focusing on delivery drivers. “When my mom gets sick, it’s all, ‘You should have been drinking more water,’” she says. “But the organization never responds with effective acclimation programs or appropriate breaks.”

Work like Coleman’s, Moses says, demonstrates how students are translating their ethical reflections into real-world action. “Students are learning how to do research in partnership with people who are experiencing the effects of heat directly, and how to see that as part of their ethical responsibility,” he says.

Throughout the academic year, the institute will extend those conversations campuswide. The 2025 Campus Read selection, marine biologist and policy expert Ayana Elizabeth Johnson’s What If We Get It Right? Visions of Climate Futures, set the tone for the year by inviting the community to imagine climate solutions rooted in hope. Upcoming events include lectures by environmental justice leaders, community workshops,

WHY: At its core, the club is all about connection. “Climbing is the medium through which we socialize,” says Salem. It’s not uncommon for participants to celebrate classmates’ achievements, like finally completing a challenging route, while forging new friendships. “The people that you meet on a climbing trip can become regular friends you see around campus,” he says. “That’s probably the most tangible benefit of the club beyond just the fact that it’s good for your fitness.” —DM

and creative projects developed through Moses and West’s Heat and Health Design Action Lab, a Tri-Co Philly course focused on social practice art in response to the health impacts of extreme heat.

Clemens, who is enrolled in the class, is particularly excited about the course’s collaboration with multidisciplinary artist Li Sumpter and the North Philadelphia Peace Park, a community-managed urban farm. The class will work with Sumpter to create heat-related informational materials, including a podcast. “I think some of the most powerful efforts are the ones that come from the community and are horizontal in that way: mutual aid efforts, sharing air conditioning, or just checking in on one another,” Clemens says.

Stauffer believes this multidisciplinary approach makes the Kim ethics institute’s mission distinct. “The urgent and intractable problems that we face as human beings are not likely to be solved by one methodology or discipline,” she says. “Our greatest hope for new possibilities comes from collaboration—people working together, cooperating, challenging each other, disagreeing or seeing things differently, building new structures out of those productive differences.”

Following President Wendy Raymond’s call to “unleash intellectual curiosity” at Haverford’s Convocation ceremony Sept. 2, members of the Class of 2029 exit Marshall Auditorium. The event, a new tradition for the College, capped off Customs and officially marked the start of the academic year for the newest Fords.

Scholarship support from THE JOANNE V. CREIGHTON SCHOLARSHIP

FUND has allowed Kayona Campbell ’28, an English major on a pre-law track, to immerse herself in Haverford’s energetic community and enthusiastic academic culture.

“ Because of your support, I have the opportunity to grow academically, engage in meaningful experiences, and work toward my goals with confidence. Thank you for investing in our futures and making Haverford’s transformative education accessible to all! ”

SUNSET BEHIND SWAN FIELD, PHOTOGRAPHED AT 6:50 P.M., SEPT. 30, 2025.

BY PATRICK MONTERO

CAMERA: SONY A9

LENS: FE 24-70MM F2.8 GM II

ISO: 400

APERTURE: F/3.5

SHUTTER: 1/200

As the new executive director of the Leeway Foundation, Pia Agrawal ’05 does what she’s always done: stand up for artists in overlooked communities. BY EMMA COPLEY EISENBERG ’09

Agrawal (above and opposite) in her Leeway Foundation office, where Leeway-supported artist Betsy Z. Casañas’s 2007 painting “Behind Those Eyes” hangs by the door.

Pia Agrawal ’05 spent many college nights taking the train into Philadelphia to see punk and indie music shows. “I know what it feels like to find yourself through some sort of artistic expression,” she says. But rather than become a musician, Agrawal became a tireless champion for artists, most recently as the executive director of the influential Philadelphia arts organization the Leeway Foundation. The foundation distributed grants worth about a half million dollars to 120 recipients in the Greater Philadel-

phia area in 2024, and is on track to match this number in 2025. “This advocacy,” she says, “is my creative practice.”

Agrawal grew up in Staten Island as the daughter of immigrants from India. “The path really did start at Haverford for me,” she says, noting that Philly’s music scene was how she found friends, a community, and a deepened sense of self. After graduating, she took a job at performing arts nonprofit Fringe Arts, where she rose from being an assistant to the head of her department in under two years. “I really

identified Philly as a place where I could get my hands dirty,” she says. She soon moved on to Austin—because of her obsession with the TV show Friday Night Lights, she jokes—and then to the University of Houston, where she curated the school’s site-specific interdisciplinary arts festival, CounterCurrent.

As Philadelphia is to New York City, so Houston is to Austin: a city that can sometimes be overlooked in the national arts conversation in favor of its neighbor. When Agrawal moved home to work for the arts council of Staten Island during the pandemic, this underdog mentally crystallized. “I have lived in a lot of communities that live in the shadow of another place,” she says. “Staten Island is the forgotten borough. I can’t escape this narrative. I advocate for artists in overlooked communities.”

When Denise Brown, Leeway’s executive director of 20 years, announced she’d be stepping down from that role, Agrawal applied for this “dream job.” The Leeway Foundation began in 1993 with a gift from artist and philanthropist Linda Lee Alter as an advocacy organization for women artists. It has since expanded its purview to also support trans- and gender-nonconforming artists working at the intersection of art and social change—which means Leeway’s communities are often overlooked by the arts funding model. “Leeway is a hyperlocal organization with a mission to fund Philly art for social change. Art for social change is about building community. It’s not just about supporting beautiful art, but supporting art that has a broader impact on the place where it’s being made.”

It’s also been personally impactful for Agrawal to plug into an organization that has always fought against the oppressive ways that marginalized artists have been excluded from exposure and resources. “As the child of immigrants, I was looking for work that fights against systemic racism. It truly feels like an honor to build upon the work

the organization has already done, and has really changed my ability to imagine what is possible.”

In a national moment where, Agrawal says, immigrant artists, transgender artists, artists of color, and disabled artists are under profound attack, she feels the urgency, and that this moment is unlike any other she’s ever seen. But, she says, the marginalized artists being targeted under “Trump 2.0” are not new to the Leeway community. What’s new is that they are being forced to take unprecedented risks to continue to make their art. Agrawal sees her job as helping to provide a sense of community and safety for artists whose quests for self-expression and community impact have become all the more vital during these fraught times.

“Leeway isn’t going anywhere,” Agrawal says, confident in a mission-focused funding stream that is not reliant on federal dollars. “We are not going to get pushed to the side, we are not changing our funding model, we are going to keep taking up space. … We’ve been preparing for this fight for decades.” She laughs. “Come at me, let’s go.”

‘‘ Art for social change is not just about supporting beautiful art, but supporting art that has a broader impact on the place where it’s being made. ’’

The author of two novels that play with our sense of chronology, Hilary Leichter ’07, in her new role as a Columbia University professor, is helping the next generation navigate a challenging timeline. BY PATRICK

RAPA

“ The decision to become an artist in this particular moment feels fraught. I did not know that these were the questions we were going to be asking, like: Does it matter if art is made by humans? ”

“I don’t sit down and think, ‘I’m gonna mess with the time-space continuum today,’” says author Hilary Leichter ’07. “It’s just something about the time that we’re living in—it’s something about writing while having to do other things, and live a life.”

Most people who read Leichter’s witty, intimate, slyly dystopian novels seem to love them, but they don’t always agree on how to talk about them. Her first book, Temporary (Coffee House Press/Emily Books, 2020), bends the laws of time and space, with its protagonist ping-ponging through a multiverse interpretation of the gig economy. In her second, the multi-point-of-view novel Terrace Story (Ecco, 2023), a young mother discovers that the closet door in her tiny apartment opens up to a bucolic but disconcerting outdoor space—but only sometimes.

What are we looking at here? Sci-fi? Magical realism? Romance? When a Reddit user asked for book recommendations that pulled readers into “otherworldly places” and “liminal spaces,” the decidedly gore-free Terrace Story popped among a sea of horror titles.

“I love that reading of it,” laughs Leichter. “If you sort of release control over what you’ve written, it can allow for a hot take like that, which I find so exciting. I didn’t write it as a horror novel, but who am I to say it isn’t?”

The way she looks at it, Temporary and Terrace Story are now beyond her control. “I’ve been lucky enough to have critics and other writers I respect really respond to my work in ways that echoed my intentions, and that’s a wonderful feeling,” she says. “But that’s really the most you can hope for.”

Leichter was an English major at Haverford, but involved in the a cappella group Outskirts and the theater. “I was in all of the productions on campus, and it was just a magical place to grow up,” she says. “It really felt like summer camp for nerds. It was just idyllic.”

After graduating, she moved to the Big Apple and produced a play for the New York International Fringe Festival. She had Broadway dreams and went on a few auditions competing with conservatory kids, but soon realized she wanted to create her own work.

“I started writing fiction, and it felt so different from everything I had done before. There was so much freedom and power to do anything, and to make anything happen.” Leichter earned her M.F.A. at Columbia University, where she recently joined the tenure-track faculty. Now she teaches undergrads and grad students in that same program, helping a new generation hone their writing skills.

“The decision to become an artist in this particular moment feels fraught in ways that I did not anticipate when I was their age,” she says. “Maybe that’s naive of me, but I did not know that these were the questions we were going to be asking, like: Does it matter if art is made by humans?”

It’s already hard enough to be a writer in this competitive environment, she says, without throwing robots into the mix. Which is partly why she’s been blown away by the way her students treat each other. “I don’t remember thinking of my generation as unkind,” she says, but these kids are especially good listeners and quick to forgive. “They’re so just cognizant of the fact that this is a room of people who have experienced all different things, and having a kind of awe and respect for that.”

At Columbia, Leichter is known for her undergrad seminar called “Time Moves Both Ways.” It explores the concept of “time travel,” but of course it’s not precisely a sci-fi thing. They’re just as likely to read Muriel Spark as Ursula K. Le Guin while they investigate the way time can be manipulated and rearranged in storytelling. “I wanted the students to leave the class not being able to read any book without thinking about time travel.”

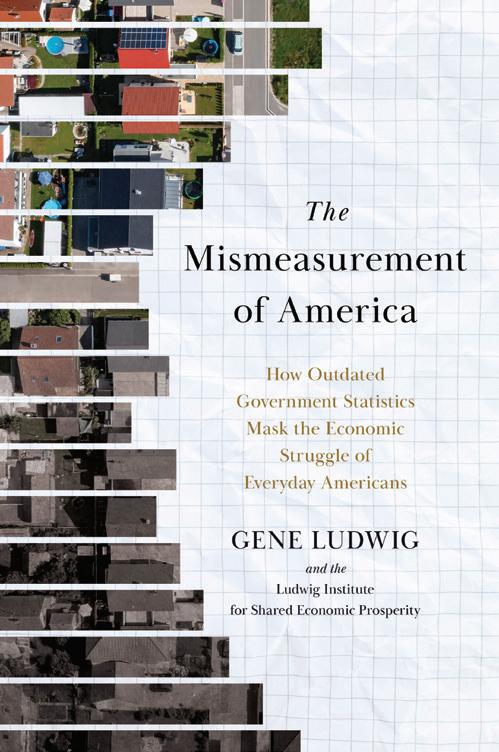

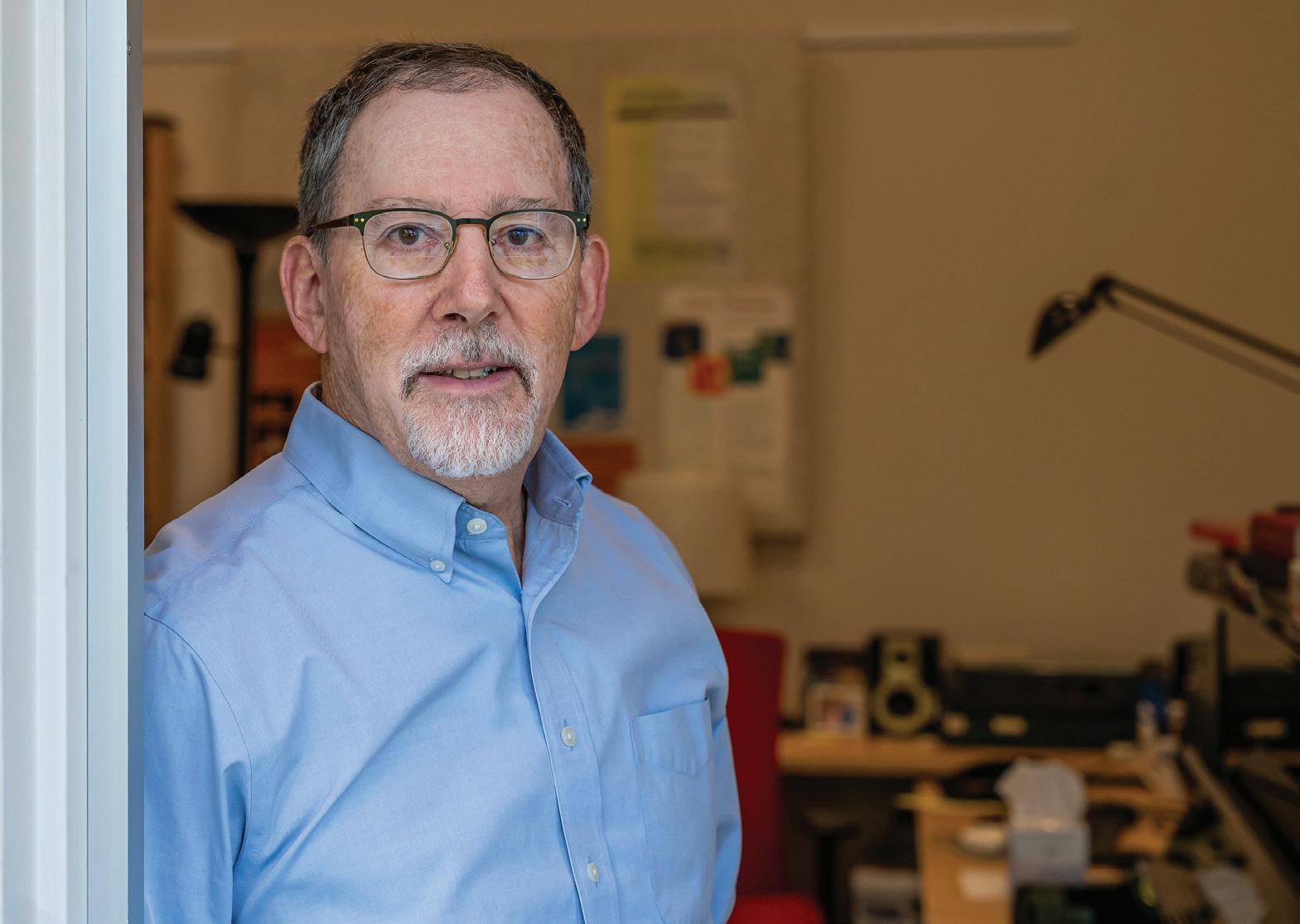

On the economist’s quest to develop financial data that paints a clearer picture of Americans’ prosperity.

BY DAVID SILVERBERG

From the halls of the Clinton White House to a namesake nonprofit dedicated to financial research, Gene Ludwig ’68 has spent much of his life working to advance the economic prosperity of millions of Americans.

As the Comptroller of the Currency under President Bill Clinton, Ludwig encouraged banks to increase lending to marginalized communities that had been historically obstructed from securing loans—or charged more than white customers when they did. His work led to hundreds of billions of dollars of bank money over time flowing into lower-income communities. His office brought 27 fairlending cases that led to tens of millions of dollars in fines against violators, the nation’s first major assault on lending discrimination.

As the founder of the nonprofit Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity (LISEP), he’s worked to improve the economic well-being of low- and middle-income Americans. LISEP, for instance, developed a new calculation: True Weekly Earnings, which offers a more comprehensive overview of the nation’s job market quality by including in its computation unemployed workers seeking employment and part-time workers.

Today, his quest finds him delving into government statistics that he claims are antiquated and that often lead politicians and the media to paint misleading pictures of American prosperity. Figures like unemployment rate, gross domestic product (GDP), and the consumer price index (CPI) are put under the microscope in Ludwig’s new book, The Mismeasurement of America: How Outdated Government Statistics Mask the Economic Struggle of Everyday Americans (Disruption Books).

Ludwig’s book compiles both grievances and possible solutions in an attempt to connect dots that previously floated alone in space.

Ludwig spoke to Haverford’s David Silverberg about what inspired the book, the root problem with how government statistics are calculated, and what he found most rewarding about his years at Haverford.

Was there a light-bulb moment when you decided to provide clarity on the economic figures we read about daily?

I slowly began to see the deterioration of the middle class. Everybody’s smiling in upper classes, but other folks are not

smiling. Political figures were whistling Dixie, saying how GDP was surging, but how can the numbers continually look so good? So, I analyzed the numbers more. Middle America was hanging on by its fingernails. That inspired me to do some deep research, hire some of the best young economists I could get my hands on, and come up with the real numbers that reflected a reality barely anyone was talking about.

Why don’t current government economic statistics accurately reflect the real experience of middle- and low-income Americans?

They are put through a filter, so I wouldn’t say they are inaccurate, exactly, but more misleading. The concepts for these statistical definitions were locked in since the 1930s but now, almost 100 years later, those definitions hadn’t changed even as the times did.

A headline statistic is CPI, which sounds rigorous and bipartisan, but it reflects a basket of goods and services of around 80,000 things. Now, if you’re earning a wage in middle America, you’re not paying for 80,000 goods and services, but a much narrower bunch of products that mean something to you, like your rent and transportation and food. I’d say around 200 items max.

We can prove that over the last 20 years—and we suspect that it’s been the case over the last 40—that smaller basket of things that are most meaningful for middle- and low-income Americans has been inflating faster than those 80,000 total items the CPI is based on. That’s what we call the True Cost of Living.

You wrote that, in essence, with improved stats, policymakers can better evaluate the bang-for-the-buck of

Continued from page 21

policies, and truly understand their impact. Do you think there’s a strong chance there will be any kind of shift? My next book will likely be called Pathways Out of the Swamp, which looks at how to improve our economic prosperity. This is hard, really hard.

We should measure with some rigor the programs that the federal government wants to put in place. We don’t measure over time whether they’re successful or not. We just measure grossly how we’re doing or not doing, and even that, as I’ve just indicated, has kind of been messed up.

Going back to your Haverford years, how did your time here impact or influence you?

What I really loved about Haverford was its rigorous academic environment and high-quality professors. The faculty, uniformly, were terrific and they really cared about their students. They were willing to listen to us no matter our views, whether they agreed with them or not.

I listened to a podcast where you recounted that at the time of your Clinton administration confirmation hearing, you were asked about lending discrimination, and you said, “I promise that I will pull it out by root and branch.” And you did. What did you find most gratifying about focusing on that issue when you were Comptroller?

Back then, my worry, principally, was for low-income Americans, and particularly Black Americans, who had been discriminated against in the lending sector.

Once I brought those cases of discriminatory lending to the court, and fined the perpetrators millions of dollars, I think the banking industry changed markedly after that.

Also, I remember one bank that got hit very hard by fines decided to hire its first senior Black officer in charge of the mortgage department because they decided it was time for a change. But I saw to it that the banking industry did more than just hire Black managers—they made sure that people were being treated equitably.

Is everything perfect? Nothing’s perfect. But things are much better than they used to be.

David Silverberg is a journalist and writing coach in Toronto who has been reviewing books and interviewing authors for more than 15 years.

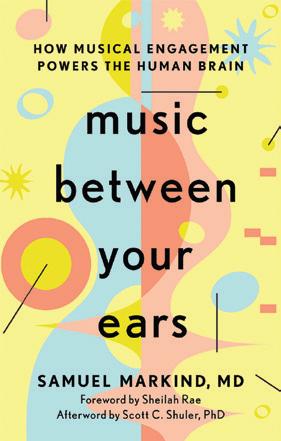

SAMUEL MARKIND ’79: Music Between Your Ears: How Musical Engagement Powers the Human Brain

(Johns Hopkins University Press)

Blending neuroscience, psychology, and narrative, Markind, a neurologist, explores how music can impact the brain at every level, from memory and motor function to emotion and identity. Drawing on his extensive clinical experience and research, Music Between Your Ears explains why melody and rhythm are integral parts of the human experience and what music reveals about our cognition and consciousness. Throughout, Markind’s straightforward approach invites readers to view active participation in music as much more than a source of entertainment, but rather a neural superpower that can improve well-being.

WILLEM DEVRIES ’72 (CO-EDITOR): Sellars and Davidson in Dialogue: Truths, Meanings, and Minds (Routledge)

In this edited volume, deVries gathers essays that probe the affinity and critical tensions between two of the most influential figures of 20th-century analytic philosophy: Wilfrid Sellars and Donald Davidson. Both thinkers challenged the mentalistic conception of meaning, advocating instead for holistic and socially rooted accounts of mind, action, and language. The contributions featured in the book analyze convergence and divergence across semantics, epistemology, ontology, and normativity, illustrating how Sellars and Davidson each erased the boundary between philosophy of language and philosophy of action. The book is ideal for scholars and advanced students interested in the history of analytic philosophy.

DENNE MICHELE NORRIS ’08: When the Harvest Comes (Penguin Random House)

In her debut novel, heralded by The Boston Globe as “achingly beautiful,” Norris tells the tale of Davis Freeman, a Black violinist set to marry his beloved Everett. As they prepare for the ceremony, Davis learns that his father—a Baptist minister—has

been killed in a car accident. Grief and trauma collide as Davis confronts the legacy of a father who never accepted his identity. With luminous prose that plumbs the emotional depth of her characters, Norris deftly intertwines themes of love, race, and the gravitational pull of family.

VIRGINIA ADAMS O’CONNELL ’86: Remission Quest: A Medical Sociologist Navigates Cancer (Temple University Press)

With Remission Quest, O’Connell brings her training as a medical sociologist to bear on her personal journey with primary bone lymphoma. Before her 2019 diagnosis, O’Connell had studied the healthcare system and those navigating serious illness, but during her diagnosis, treatment, and recovery, she confronted the theories she’d studied to make sense of her own experience. O’Connell examines the burden of responsibility often placed on cancer survivors and the anxiety of living with uncertainty, crafting a work that blends scholarship and memoir.

DAVID KOTEEN ’67: Gratitude & Compassion (self-published)

With this follow-up to his creative biography of dancer Nancy Stark Smith—a founder of contact improvisation, a movement-based dance form rooted in touch and spontaneous collaboration— Koteen shifts from documentation to reflection with co-author Christie Svane. With an ocean and much of the U.S. between them (Koteen lives in Oregon’s woods, Svane in Southern Spain), they connected via email after the 2020 death of their mutual friend, Stark Smith. Gratitude & Compassion compiles their correspondence, which explores Stark Smith’s influential presence in their lives, stories from their youth, and their current challenges, including Koteen’s mysterious head wound and the life-threatening surgeries he’s endured.

ELANA RESNICK ’05: Refusing Sustainability: Race and Environmentalism in a Changing Europe (Stanford University Press)

Resnick, an assistant professor of anthropology at University of California, Santa Barbara, presents a provocative rethink-

ing of what sustainable development looks like in Europe, especially along racial and economic lines. Drawing on her ethnographic research on Bulgaria’s Roma people, Resnick challenges narratives by asking who performs the labor powering green economies and development, and at what cost? Through stories that explore democratic failures, mutual aid, and the power of women’s friendships, Refusing Sustainability shows how people viewed as discardable resist the systems that both rely on and exclude them.

TOM BRETL ’68: Fractal Picturebook (self-published)

In this picture book, which the author has made freely available online, Bretl invites readers to explore a rich gallery of fractal images created with computer programs he developed. Visuals are accompanied by information on how each was created, presented without technical jargon. An accessible bridge between art and mathematics, Fractal Picturebook makes geometry both intelligible and beautiful for readers of all stripes.

KAREN KOHN ’00: Accessing Academic Library Collections for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (Bloomsbury)

With this timely and practical guide, Kohn offers academic librarians and scholars a clear framework to evaluate and enhance library collections. Accessible and backed by clear data, Accessing Academic Library Collections for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion arrives at a pivotal moment as institutions across the country turn a critical eye to their collections. Kohn provides four different methods to analyze collections by subject matter, along with their advantages and disadvantages. Three chapters by guest authors also provide insight from successful assessment projects.

FORD AUTHORS: Do you have a new book you’d like to see included in More Alumni Titles? Please send all relevant information to hc-editor@haverford.edu.

Mena Kazista ’28 lent her experience as a defender on the field hockey team to a sports movie shot by her filmmaker mother and aunt. She’ll bring lessons from the set back to the pitch.

BY CHARLES CURTIS

’04

Kazista (above and opposite, in gray) on the set of The Next Play

For Mena Kazista ’28, art, life, family, and sports all converged in one fortuitous summer. The Nazareth, Pa., native’s mother, Koula Kazista, and aunt, Katina Sossiadis, wrote a script— The Next Play—that focuses on a high school field hockey player struggling with mental health. Mena, who’s a defensive midfielder for Haverford field hockey, wore multiple hats during the Meritage Pictures production which wrapped in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley this past summer. From acting as an extra to consulting on the

sports side of the script to working with actors as a production assistant, she did a bit of everything. She spoke to Haverford magazine about how she enjoyed life on set and what experiences will transfer back to the field hockey pitch.

Field hockey is in her blood. My mom played the sport in high school. When I was in second grade, she suggested I try it. I tried so many sports between then and now, and this one is my favorite. Softball was too slow, and field hockey is collaborative and continuous, where mistakes felt

like they were more accepted. I think part of it was that my mom was so into it—her excitement made me excited, too. We’d watch college and pro games together. I wasn’t sure I wanted to play in college, but when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, I practiced in my driveway and realized I couldn’t sit with the fact that I wasn’t playing games at all. That’s when I realized how much I liked the sport and got more serious, practicing more and working harder with my club team.

Her mom and aunt wrote what they knew—and asked about what they didn’t. They made their first feature, Epiphany, about a father-daughter relationship, in 2019. For their second script, their producers told them to try something different. So they focused on field hockey since I play and both my cousins do, too. The plot focuses on two girls at a boarding school. One takes the spotlight from the other who then struggles with mental health. When I read it, I could tell every character they had created was based on someone in our real life. They consulted me on the field hockey action. “We need something really high-stakes— what could be happening in a game?” Or “What should this character say on the field?”

The movie isn’t just about sports. My mom and aunt saw how sports can impact everybody mentally. Field hockey has taken a toll on me in some ways as I’ve battled anxiety and perfectionism. There hasn’t been much conversation about that side of sports until recently. The movie is called The Next Play because it’s something we always say on the field if someone messes up: “That’s OK! You’ll get them on the next play.”

The movie earned her multiple film credits. I’m a featured extra who plays a member of the boarding school team. I have a couple of lines, but I’m in the background of a lot of scenes. I also joined the film as a production assistant. I got moved up to what’s called “first team”—I promise my mom wasn’t responsible for it, it wasn’t nepotism!—which is working with the actors. When they would arrive in the morning, I was with them through hair and makeup and wardrobe. I was in charge of making sure they were where they should be if they were on

camera. It was a really good experience and I was honored to be trusted with that.

It was fun, but Hollywood isn’t in her future. Being on set made me want to be in the movie industry for about two days … and then not. There were some long days—we’d sometimes start at 6 p.m. and didn’t finish until 6 a.m. I hated not having a routine. I plan on being a political science major and to go to law school. I really do enjoy helping people, especially those who are unable to help themselves or are put at a disadvantage. I think I could make a great impact that way.

She found a way to connect her cinema experience to Haverford’s field hockey squad. I asked the assistant directors why they picked me for first team production assistant. They told me I was a doer, that I have leadership skills, and I’m a people person. That’s what Haverford stands for and what being on a team means. Through the filmmaking process, I saw team-oriented scenes and events. I kept asking myself, “Is this realistic?” So I’m able to bring that back with me, where I can look at what I saw in my “fake” field hockey team and apply it to my real team. I’ve also struggled with my confidence in field hockey, and that was definitely a part of the movie. I was talking to my mom about the upcoming season recently and she said, “You have to be confident. Didn’t we just make a whole movie about this?” The point of the film is: In the end, it’s all going to be OK.

Charles Curtis ’04 is managing editor for USA Today’s For the Win and an author of the Weirdo Academy series, published by Month9Books.

‘‘ They told me I was a doer, that I have leadership skills, and I’m a people person. That’s what Haverford stands for and what being on a team means.

”

When he took the helm of the Maritime Aquarium at Norwalk in November 2019, Jason Patlis ’85 joined a beloved Connecticut institution facing existential threats. A major federal construction project was impacting the aquarium’s buildings. Then, four months later, came a global pandemic. Upon emerging from those two threats in 2022, Patlis could then turn to more philosophical questions about what an aquarium could—and should—be in the 21st century.

For Patlis, navigating these challenges and opportunities interlaced many threads of his career. After a short stint on Wall Street upon graduating Haverford, Patlis turned to law and conservation, worked for the executive and legislative branches of the federal government, received a Fulbright scholarship to study governance and

conservation in Indonesia, and then six years later—after serving on a number of U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) and World Bank projects— returned to the U.S. for influential roles with the World Wildlife Fund and the Wildlife Conservation Society.

Now, as the president and CEO of one of Connecticut’s largest family attractions, Patlis has embarked on a new, 10-year strategic plan to create “an aquarium without walls,” expanding beyond traditional exhibits to new programming along the coast and on the water. For Patlis, the goal is to redefine the role an aquarium plays not only as a local attraction and conservation leader, but as an institution that enriches the lives of people in the community.

He points to the College as the place where he honed the communication skills that power his advocacy and built the scientific and ethical framework that shapes his

work today. Haverford spoke with Patlis about his role, the importance of aquariums, and how he finds joy.

What fills the day of the CEO of a beloved aquarium?

On a day-to-day basis, I define my job as making everyone else’s job easier. Whether that’s dealing with fundraising, operations, strategic thinking, or budgeting, I offer guidance to help my team navigate complications. It takes a cohesive, dedicated, talented team to make a place like this a success. Long term, I work with the team to craft and implement the vision, mission, and goals that shape our future direction, and create opportunities for that ambition.

Let’s talk about those complications and opportunities. What are the biggest challenges you’ve encountered? Complications existed before I started the job. A $1.3 billion federal railway project literally bisecting the aquarium’s facilities jeopardized our very survival. The state provided us funding to replace some of the major exhibits and the IMAX theater that we were forced to close, so we survived that, just in time to deal with the global pandemic. And the pandemic required us to close our doors for three months, furlough workers, address financial challenges—all the while caring for the 8,000 animals that needed food, husbandry and veterinary care, functioning habitats, and operating life-support systems. But, thanks to a great team and lots of support, we emerged even stronger.

In terms of opportunities, a lot of zoos and aquariums have conservation programs to complement their own living animal collections. The Maritime Aquarium didn’t have a formal conservation program when I started, but since then, we’ve grown from less than $100,000 to more than $2 million in funding. We’ve also expanded our educational program-

ming to now reach 60,000 students and children in the region. Last year, we developed our forward-thinking strategic plan to build “an aquarium without walls” that re-imagines what an aquarium can be.

What attractions are community members most drawn to?

Our focus is the local biodiversity of Long Island Sound, and our most popular species are the seven-foot sand tiger sharks and harbor seals native to local waters. All told, we have more than 8,000 animals— which is a lot for an aquarium— comprising more than 320 species. We specialize in jellies, and cultivate them for aquariums around the nation. Because we are housed in a building that dates back to 1867 and was originally a steel factory, our footprint is small, and we cannot have, like newer aquariums, large tanks with millions of gallons of water. So we seek to create more immersive, interactive, and intimate experiences with local marine animals, rather than overwhelm visitors with large exotic marine animals. We do it with touch tanks, feedings, animal encounters, and volunteer and educator engagement. We also have Connecticut’s only mob of meerkats.

How did your experience at Haverford inform your career path?

Haverford instilled a profound sense of responsibility for promoting the welfare of others and conducting oneself in an ethical way, both personally and professionally. The Honor Code played an enormous role in my thinking. Academically, I was an English major and my professors were tough, giving me writing and communication skills that were instrumental throughout my career. I was also very heavy into the sciences—I took organic chemistry and the Biology Department’s Superlab, which gave me an important scien-

tific understanding that helps in the path I’ve chosen.

What does the future hold for aquariums?

In the present day, they are fun family attractions, conservation leaders, education centers, and economic engines of local communities. But looking to the future, they can also serve as critical pillars of society, as a voice leader and community resource to bring people together and inspire a stronger connection to each other and to the natural world on which we depend.

What lessons from prior positions did you take into this one?

In working as a lawyer for the government, I saw the power of law, regulation, and public policy, but I also saw the limitations in that approach. In working for two of the largest conservation organizations in the world, I saw that the key to their success was not so much their global reach and scale, but rather their intense commitment to and presence in the local communities where they worked. It comes down to changing knowledge, attitude, and ultimately behavior. Both public policy and private action are needed to effectuate change for the better. And I see an institution like the Maritime Aquarium bridging both of those towards a more sustainable and more ethical future.

What do you do for fun when you’re not immersed in the aquarium world?

I love to be out in nature, primarily cycling and hiking. Years ago, I cycled across Europe and through the Andean, Himalayan, and Karakoram mountains. Not much marine life on those trips, but once, while solo hiking through the central mountains of West Papua in Indonesia, about 10,000 feet in altitude, I found a fossilized seashell. A reminder that the ocean is everywhere.

—Eric Butterman

Fords have long played an outsized role in studying the cosmos.

Now, that includes significant contributions to the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s Legacy Survey of Space and Time—the world’s most ambitious survey of the universe. B Y SARI HARRAR

From Haverford to the Stars

of Chile’s 8,800-foot Cerro Pachón, Peter Ferguson ’12 walked out of the Vera C. Rubin Observatory one winter night in 2023. Rocks crunched under his boots, a chilly wind blew, and compressors that heat and cool the facility’s groundbreaking super telescope, still under construction at the time, hummed. But he barely noticed.

Billions of stars were gleaming in the clear black sky.