ABSTRACT

Despite its central location in Prishtina, the Palace of Youth and Sports—like many Yugoslav-era structures—commands a striking physical presence yet struggles to fulfill its purpose today. For younger generations, the building feels disconnected, its function unclear, making it difficult to form a meaningful attachment to it.

As a child, my parents would often park our car in the abandoned section of the building complex. Each time we stepped out, my mother would reminisce about ice skating in that very space. The contrast was unsettling for me—even then, I found it difficult to reconcile the vibrant past they spoke of with the empty, oversized parking in front of me. This reflection on the building’s transformation leads me to question the nature of urban change. The people who remember the building’s former vitality speak of it with nostalgia, but who, then, which ‘Youth’ is this building then functional for now?

When public spaces lose their historical and social significance, communities experience detachment, their sense of place gradually eroding. Collective memory, though intangible, plays a vital role in shaping social cohesion, and its absence is often felt most when it begins to fade. The loss of engagement and the neglect of once-thriving spaces can fracture urban identity, leaving behind mere shells of their former selves. The Palace of Youth and Sports exemplifies this

phenomenon—a once-important structure now struggling for relevance amid rapid urban growth and shifting social and economic landscapes. Its story underscores the need to preserve such buildings as cultural anchors, ensuring they continue to foster identity, connection, and social sustainability.

The urgency to act upon this building is enhanced by a decision to renovate the complex in order to host the Mediterranean Games 2030. While acknowledging such an event as a good opportunity to activate life in this building, there stands the risk of the building not living its potential again if not rooted in the needs and responses of the people in the city. Due to its central location, both in the city and in the memories within the city for many people in Prishtina, careful consideration of the complex-ity is necessary.

To my family, friends, and everyone who has supported, encouraged, and inspired me throughout this journey—thank you for your belief in me. Your presence, in both quiet and loud ways, has made all the difference.

A special note of gratitude to Professor Daniel Hülseweg and Professor Adela Bravo Sauras. Your guidance, insight, and thoughtful critique have been invaluable to the development of this thesis. Thank you for your generosity, patience, and belief in the ideas I have explored.

This work is shaped by all those who have walked alongside me, and I am deeply and truly grateful.

“The act of looking is in itself an act of creation.”

— Peter Brook, The Empty Space

“The quest for memory is the search for one’s history”

— Pierre Nora, Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire

PROLOGUE

Portfolio of the Existing

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

PART 1: OBSERVER THE SITE AS THEATER

METHODOLOGY

The Immediate Theatre as Analytical Lens

SETTING

The Urban Context of the Site

STAGE(S)

Architectural and Spatial Qualities

ACTORS

Users and Their Roles

ACTS

Historical and Contemporary Events

IMPROVISED ACTS

Informal/Spontaneous Use

PART 2: ACTOR ENGAGING WITH THE SITE

EMBODIED RESPONSE

Personal Sensory and Emotional Encounter

DIALOGUES

Interviews and Their Insights

COLLECTIVE MEMORY

Participatory Memory-Gathering

QUESTION DIRECTION

Who Directs the Scene?

PART 3: RELATING DOCUMENTING THE EXISTING

DESIGN AND APPROACH REFERENCES Towards a Spatial Response

DOCUMENTING THE EXISTING Towards a Spatial Understanding

116-167

PART 4: THE PROPOSAL REWRITING THE SCENE

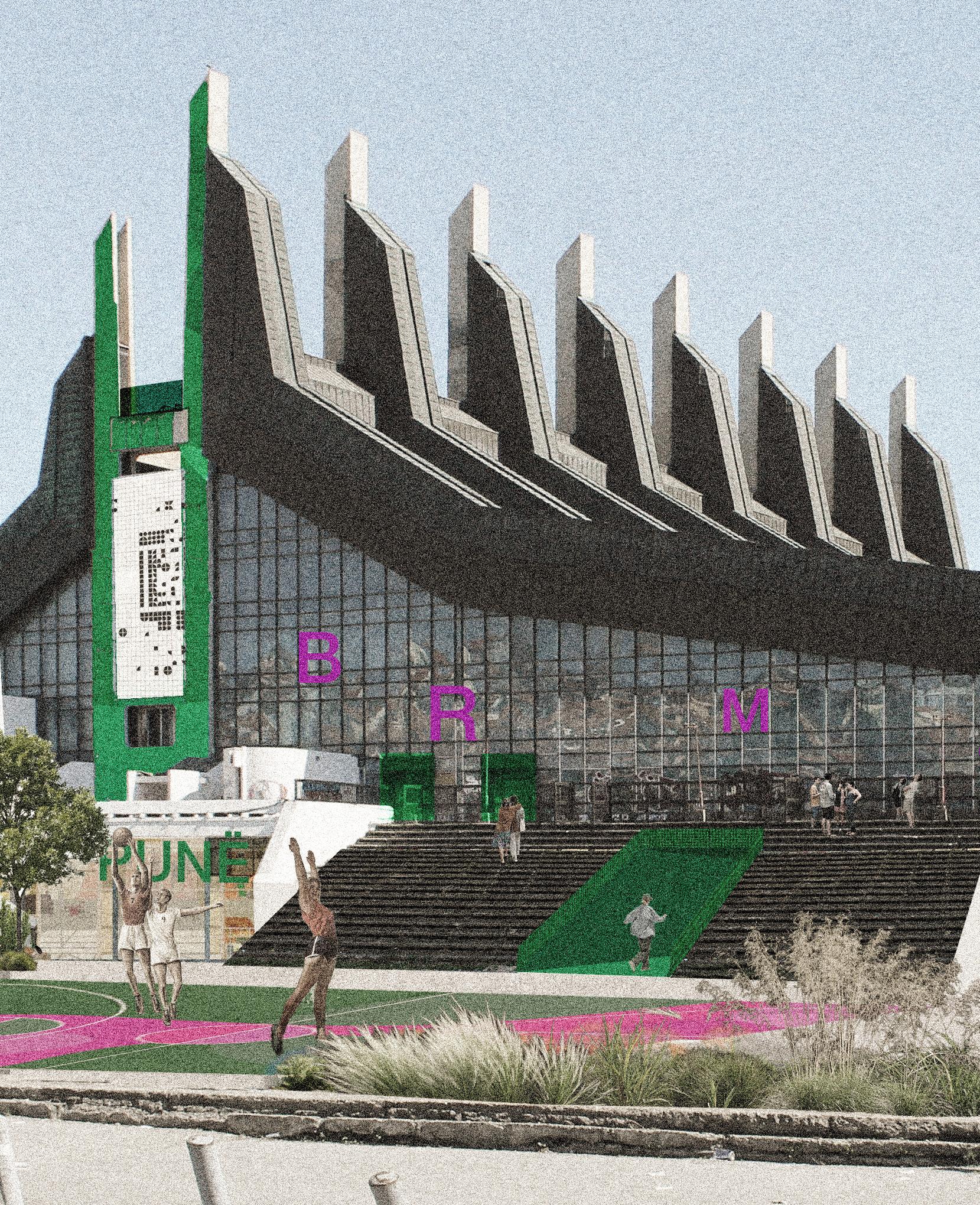

BRMZ A Transformational Cultural Venue

EPILOGUE (Concluding)

List of References

List of Drawings

List of Figures

In Kosovo, and particularly in its capital, Prishtina, the Palace of Youth and Sports stands as a monumental relic of the Yugoslav era— massive, central, and historically charged. Yet today, it feels adrift in time. For many people in Kosovo, its presence is more symbolic than functional, its significance more remembered than lived. Although it is large and prominent, the building has lost its sense of purpose, becoming a location that many pass by, some use, but only a few genuinely engage with.

This disconnect is profoundly personal. Growing up, the building held a complex and shifting significance for me. I recall my mother reminiscing about ice skating in its now-abandoned sections, a stark contrast to the vast, empty parking lot I saw as a child. Throughout my life, I saw the Palace adapting to various roles—an events space, a shopping center, a hiding place, a rave venue, and even a high school—each revealing a different facet of its informal existence and my evolving relationship with it.

Still, the structure holds collective memories. People speak of concerts, events, and moments that once filled its halls. The building lives on, but it seems to do so across multiple temporal dimensions, echoing its vibrant past while confronting its ambiguous present. This dissonance between physical presence, lack of functional clarity, and persistence in collective memory exemplifies a broader phenomenon common to post-socialist cities: the gradual neglect of iconic spaces that once anchored public life. (Czepczyński, 2008). When such buildings lose their role in the present, cities risk losing essential pieces of their identity. In this context, the Palace of Youth and Sports becomes more than a partially abandoned site— it becomes a magnifying lens through which to examine how urban identity can fracture

when its architectural anchors are left behind. Given this condition, the need to rethink and revitalize existing buildings emerges as both a sustainable strategy and a means of fostering awareness of what already exists. In Kosovo, where sustainability remains an emerging discourse within architecture, the question is not only how to build responsibly but also how to live with what is already there. This thesis supports the idea that architecture can play a role in fostering such awareness: by re-engaging with heritage— its complexities, its voids, its atmospheres—we create spaces that inform, transform, and connect.

Yet this proposition raises essential questions: How do we interact with our heritage when it is layered and conflicted? Do we have spaces that allow us to reflect on our past consciously? What can the state of a building reveal about the people who surround it—those who inhabit it and those who don’t? Furthermore, how can we learn from its original use, its abandoned state, and the multiple unplanned uses that have emerged in between, all while adapting to the constantly changing needs of the city? Can the inherent complexity of the building itself offer a pathway to addressing the complexity of the urban fabric it inhabits, or are they inextricably linked?

Fig 1

The project focuses on the Palace of Youth and Sports, a building emblematic of memory and disuse, located at the heart of Prishtina. Rather than erasing its past or replacing its form, the thesis aims to develop strategies that allow its existing complexity to unfold. Through spatial analysis, participatory engagement, and an architectural intervention proposal, the project explores how a building like the Palace can evolve—not by simplifying its story but by embracing it. Engaging with former users, gathering memories, and initiating new conversations, the work positions the building as a site of continuity rather than rupture. This approach acknowledges the various ways people have found to inhabit and make spaces usable, recognizing that the sustainability of a program — the continued meaningful use of the building over time —can be as vital as the sustainability of the construction itself. In this sense, it also engages with the “temporality of the works of architecture, an aspect that is all too often forgotten when we talk about architecture’s presence in the world.” In this context, the project draws from methods inspired by Peter Brook’s concept of “Immediate Theatre,” analyzing the Palace as a living stage where multiple acts—past and present— collide. The aim is to identify spatial cues, social dynamics, and architectural potentials that can guide a respectful yet transformative intervention. The ultimate goal is not to restore the building to its former glory but to allow it to speak again and find a way to bring people back to reflect on its state while offering an alternative use. Specifically, the thesis aims to identify which parts of the building can be renewed, which aspects of the complex we can learn from, and what elements of its original program can remain, need to be changed, or be added.

This Master’s thesis provides a comprehensive study of an architectural site, structured into four distinct chapters: two analytical and two propositional. The initial analytical chapters, Part 1: Observer – The Site as Theatre and Part 2: Actor – Engaging with the Site, meticulously deconstruct the chosen location from different vantage points. The first chapter treats the Site as a theatrical production, using the concept of the immediate theatre as an analytical lens. It explores the urban context, architectural and spatial characteristics, the roles and behaviors of users, and the historical as well as contemporary events that have shaped the Site—including informal and spontaneous uses that fall outside planned or institutionalized functions. Building on this observational foundation, the second chapter shifts toward a more direct,

participatory engagement with the Site. It begins with my personal, sensory, and emotional response to the space and expands through conversations and interviews that offer multiple perspectives. This chapter also investigates methods of gathering shared memory and ends with a reflection on questions of spatial agency and authorship: who interprets, occupies, and ultimately directs the future of the space?

The subsequent two chapters translate these insights into design. Part 3: Relating –Documenting the Existing defines first the design approach and its precedents and then presents documentation of the existing conditions, and considers how previously overlooked spatial fragments might be reinterpreted or activated. Finally, Part 4: The Proposal presents a new vision for the Site, rewriting its future through a design intervention that projects new roles, uses, and relationships within its evolving urban context.

With this project, the intention is to contribute to the ongoing dialogue about sustainability in architecture—particularly in regions like Kosovo— where the reuse of existing structures is both a necessity and a cultural act. Through memory, participation, and design, the thesis advocates for an architecture that does not erase but listens and learns from what already exists.

Part 1: Observer – The Site as Theatre employs the concept of the “Immediate Theatre” as a methodological lens to analyze the site as a performative space.

This section unfolds in six chapters: it begins by establishing the methodology (1.1), followed by an examination of the urban context (1.2), the spatial and architectural characteristics of the site (1.3), the roles of its users (1.4), and the site’s historical and contemporary events (1.5), concluding with an exploration of informal and spontaneous uses (1.6).

METHODOLOGY

The Immediate Theatre as Analytical Lens

“Anyone interested in processes in the natural world would be greatly rewarded by a study of theatre conditions. Their discoveries would be far more applicable to general society than the study of bees and ants. Under the magnifying glass one would see a group of people living all the time according to precise, shared, but unnamed standards.”

Peter Brook, The Empty Space

This thesis adopts a metaphorical and interpretive methodology, using Peter Brook’s concept of the Immediate Theatre to analyze the project site. Rather than applying a conventional urban or architectural analytical framework, the site is approached as a stage, and its spatial, social, and atmospheric conditions are read performatively. Brook’s notion of Immediate Theatre—stripped down, direct, and rooted in the dynamic interplay between actor, space, and audience—offers a compelling metaphor for understanding the site’s potential for interaction, transformation, and meaning-making. By translating theatrical principles into spatial analysis, this method facilitates a layered, experiential reading of the site, highlighting presence, absence, memory, and performative potential. It aligns with qualitative, interpretive research traditions, especially those grounded in hermeneutics and arts-based inquiry, offering a creative yet rigorous framework for engaging with the complexity of place. The foundation for this approach emerged during the final two semesters of my Master’s studies in Architecture, where I worked on a semester project focused on Temporary Theatre, which provided me with the opportunity to read the works of Peter Brook. In the final chapter of The Empty Space, Brook’s tone shifts—it becomes, as he describes, “ashamedly personal” (Brook, 2008,

p. 133). This change of tone was pivotal for me. His writing in this section is less about defining a genre of theatre and more about embodying a methodology—one that unfolds in the moment, is shaped by the experience of the performer and the audience, and resists rigid categorization. He writes, “This is a picture of the author at the moment of writing—searching with a decaying and evolving theatre” (Brook, 2008, p. 135). This acknowledgment of the ephemeral and subjective nature of understanding resonated deeply with my relationship with the project site.

Having grown up with this building in my daily life, I carried with me a long-standing, personal connection to the site. My intention was not only to design for it but also to listen to it—to observe, interpret, and honor its layers of meaning without imposing a fixed narrative. This deeper understanding and observation required a methodology that could accommodate both distance and intimacy. Inspired by Brook’s practice of holding space for subjective experience within creative inquiry, I allowed myself to engage with the site both as an observer and as someone personally entangled in its story. This dual positioning became the backbone of my interpretive method. Brook’s description of theatre as a “stage moving

picture” rather than a static “stage picture” was especially significant in shaping my approach (Brook, 2008, p. 144). Just as he speaks of the theatre designer who creates an “incomplete design… one that has clarity without rigidity; one that could be called ‘open’ against ‘shut’” (Brook, 2008, p. 143), I sought to engage the building not as a fixed object, but as a living, breathing spatial narrative—one that evolves with time, use, and memory. The site, like a stage, is in constant transformation. Some of its parts may be deteriorated or abandoned, yet they remain integral to an active urban script, continually shaped by people’s interactions and adaptations.

The idea that “a wrong set makes many scenes impossible to play” (Brook, 2008, p. 141) also informed my thinking: it reminded me to pay attention not only to the physical conditions of the site but to its latent affordances and constraints— its ability to enable or inhibit specific patterns of behavior and interaction. Observing how people have informally used the site over time, often in ways never intended by the original design, revealed an unscripted form of architecture that echoes the spirit of Immediate Theatre.

Through this theatrical lens, I was also able to uncover hidden relational dynamics—between built and unbuilt spaces, between the site and

its urban context, and between permanence and impermanence. Brook’s notion that “a part, instead of being built, can be born” (Brook, 2008, p. 146) inspired me to see the design process not as the imposition of form, but as the unfolding of something already present—something waiting to be acknowledged through attentive presence.

Ultimately, this methodology allowed me to read the site not only as architecture but as a performance—one that reveals itself in layers, through time, through memory, through movement and stasis, absence and presence. Just as Brook suggests that “open passageways must allow an easy transition from outside life to meeting place” (Brook, 2008, p. 147), I aimed to keep the conceptual doorways open between personal experience and architectural interpretation, between theatre and space, between analysis and design.

SETTING

The Urban Context of the Site

The Palace of Youth and Sports (Albanian: Pallati i Rinisë dhe Sporteve), formerly known as “Boro and Ramiz,” is a prominent multi-purpose complex located in the heart of Prishtina, Kosovo. It was built in 1974 and designed by the Bosnian architect Zivorad Jankovic, Halid Muhasilovic and Sretko Espek.

The Palace of Youth and Sports in Prishtina was built during the late 1970s and early 1980s, a time when the city was rapidly transforming from a modest Ottoman-era settlement into a modern socialist capital within Yugoslavia. Situated strategically near the emerging city center, between what is now Mother Teresa Street and the Grand Hotel Prishtina, the Palace was conceived as a monumental, multifunctional complex that would serve cultural, recreational, and symbolic roles. Its large-scale and bold late-modernist architecture marked a significant departure from the older urban fabric, reinforcing a new civic axis and encouraging the city’s westward expansion. This project also aligned with a broader Yugoslav trend during the 1970s, when “commemorative programs became increasingly ambitious and inherently more architectural, conceived as fullfledged community centers, frequently in smaller provincial towns” (Kuli , 2018, p. 34), suggesting that the Palace was both a local and regional manifestation of this shift toward monumental yet socially engaged public architecture.

Originally named “Boro and Ramiz,” after two partisan heroes representing Albanian-Serb unity, the building reflected the socialist ideals of progress, inclusivity, and modernization. The Youth Center Building, “Boro and Ramizi”, was constructed to embody the Yugoslav ideals

of brotherhood and unity. This structure was given the name of the legendary partisan duo Boro Vukmirovic and Ramiz Sadiku, who were celebrated for their joint resistance against fascism during the Second World War. Their symbolic presence conveniently served to promote an optimistic façade of interethnic unity in Tito’s Yugoslavia, leaving an enduring impression in the collective memory of the SFRJ.

To fully understand the Palace of Youth and Sports, one must examine its historical, ideological, and geographical context within the broader framework of Yugoslav architecture and urban development. Constructed in the late 1970s, the building emerged during a period when Yugoslavia was undergoing a massive transformation—shifting from a predominantly rural society to an urbanized and industrialized federation. Architecture played a central role in this shift, empowered by the unique model of self-managing socialism that granted architects and planners expanded agency. This period saw the emergence of a coherent and ambitious architectural culture, deeply intertwined with stateled social goals, especially the modernization and emancipation of society through education and cultural participation (Kulic, 2018). Cultural centers, particularly in peripheral and less developed regions, became emblematic of this effort, serving not only as public gathering places but as instruments of ideological dissemination and civic transformation. Like the Revolution Center in Nikši —an over-scaled project left incomplete due to political and economic rupture—the Palace of Youth and Sports was similarly envisioned as a multifunctional complex reflecting civic unity and progress. Although it was built with collective contributions and intended as a symbol of social integration, its full realization was interrupted by the onset of political instability in the 1990s. The trajectory of this building reflects both the ambitions and contradictions of Yugoslav socialism, serving as a monument to a political system that facilitated architectural experimentation while often outpacing the practical and economic capacities of its environment (Kulic, 2018).

From Site to City

Why the Urban Context Matters

A Brief History of Pristina’s Urban Development

Understanding why this specific location in Pristina was chosen requires examining the city’s evolving urban fabric—particularly during the Yugoslav modernization period. As the administrative center of the Autonomous Province of Kosovo and Metohija within Socialist Yugoslavia (1946–1989), Prishtina underwent a profound architectural and ideological transformation. Before this era, the city had very few modern buildings (Gjinolli, 2015).

After World War II, urban planning across Yugoslavia became a key instrument of ideological transformation, aimed not only at rebuilding infrastructure but at cultivating the “new socialist individual.” Some cities adopted a syncretic approach, integrating old and new elements. For example, in Zadar, Croatia, architect Bruno Mili ’s 1953 plan preserved the historic Mediterranean urban structure—characterized by narrow streets, stone paving, and medieval monuments— while introducing modern architecture that still resonated with the local character (Stierli & Kuli , 2018). Conversely, Titovo Užice in Serbia replaced Ottoman-style markets with the monumental Partisan Square, designed by Stanko Mandi , commemorating its role as the first liberated territory in World War II (Stierli & Kuli , 2018). Pristina followed the latter model. Much of its Ottoman-era core, characterized by bazaars, mosques, and mahallas (Acun, 2002; Gjinolli, 2015; Hoxha, 2008), was demolished. The 1953 General Urban Plan, created by Dragutin Partonic, introduced functional zoning and cleared space for symbolic socialist structures, including municipal buildings, assembly halls, and civic squares (Gjinolli, 2015; Jerliu & Navakazi, 2018). This transformation was not only architectural but ideological, reflecting the socialist values of modernization, secularization, and “brotherhood and unity” (Sadiki, 2019).

This period saw rapid population growth, widespread construction of residential blocks, and the development of landmark modernist structures such as the Palace of Youth and Sports, the National Library, the Grand Hotel, and the Rilindja Tower—all reinforcing the state’s socialist identity (Hoxha, 2008; Stierli & Kuli , 2018; Vöckler, 2007). During the socialist modernization of Prishtina, particularly between the late 1960s and the late 1980s, the city underwent a profound spatial and architectural transformation that redefined its identity. This period is often regarded as the “golden

Drw 2-4 Maps by the author showing the location of the building, Continent to Country to Municipality

age” of Prishtina’s urban development within the Yugoslav Federation, when architecture was both an expression of political ideology and a tool for social engineering (Gjinolli, 2015; Hoxha, 2008). The transformation was characterized by a deliberate erasure of vernacular and oriental urban elements—such as irregular streets, mahallas, and Ottoman-era structures—and the introduction of monumentality, geometric order, and modern materials such as concrete. These changes were not merely aesthetic; they were deeply ideological, reflecting Yugoslavia’s broader agenda to construct a new socialist society (Sadiki, 2019; Vöckler, 2007). Monumental public buildings played a central role in this process. Structures such as the Palace of Youth and Sports, the National Library, the Grand Hotel, and the Rilindja Tower were designed to embody socialist ideals and serve as focal points of civic life. These buildings did not merely house state functions or cultural events—they symbolized the progressive, modern identity that the state sought to cultivate. For example, the Palace of Youth and Sports integrated commercial functions to help subsidize cultural and athletic spaces, reflecting a multifunctional and pragmatic approach typical of Yugoslav socialism (Stierli & Kulic, 2018). These monumental projects were embedded within a broader restructuring of the city’s spatial organization. From the late 1960s to the early 1980s, Prishtina expanded through the development of polyfunctional neighborhoods designed to address the city’s rapidly growing population, which rose from 19,631 in 1948 to 108,083 in 1981 (Gjinolli, 2015). These neighborhoods included not only diverse housing typologies but also integrated spaces for commerce, education, culture, and social services, facilitating the creation of a selfsustaining socialist urban fabric.

The construction of a new east-west urban axis and the city’s development toward the south signaled a new directionality in its spatial politics—literally and ideologically distancing the capital from its Ottoman and pre-socialist past (Hoxha, 2008). Public space, in this context, was no longer organic or traditional; it was re-engineered to reflect the state’s values of collectivity, order, and modernity. Although this phase of socialist modernization was relatively brief, its impact on Prishtina’s urban identity remains profound. After Kosovo’s autonomy was revoked in 1989, urban development stagnated under centralized Serbian control, and planning became a tool of ethnic exclusion (Gjinolli, 2015). During the 1990s, construction was limited and tightly controlled by

the government in Belgrade. Notably, religious institutions, such as the case of the Orthodox Church of Christ the Saviour, were constructed in 1992 in violation of urban plans, reflecting an assertion of political dominance rather than addressing urban needs (Sadiki, 2019).

In addition, following the 1999 war, Pristina experienced unregulated and rapid expansion. Although much of the city’s physical structure survived the conflict, approximately 75% of the urban fabric was rebuilt, primarily through informal and illegal construction (Rossi, 2019; IKS & ESI, 2006). This era saw the destruction of remaining vernacular buildings, the rise of illegal highrises, and widespread architectural degradation. “Parasite architecture” became common— such as single-family homes atop communal structures—and many socialist-era buildings were “renovated” with cladding that obscured or erased their original compositions (Rossi, 2019). Today, many of these monumental public buildings continue to function as administrative and cultural centers, serving as both physical and symbolic anchors in a city still grappling with the tensions between heritage preservation and neoliberal development (Jerliu & Navakazi, 2018; Vöckler, 2007). Prishtina continues to grapple with the tension between preserving its layered historical and architectural legacy and embracing rapid modernization (Gjinolli, 2015).

Drw 5

Map redrawn by author based on Arbër Sadiki’s “Public Buildings in Prishtina: 1945-1990, Social and Shaping Factors”

Palace of Youth and Sports

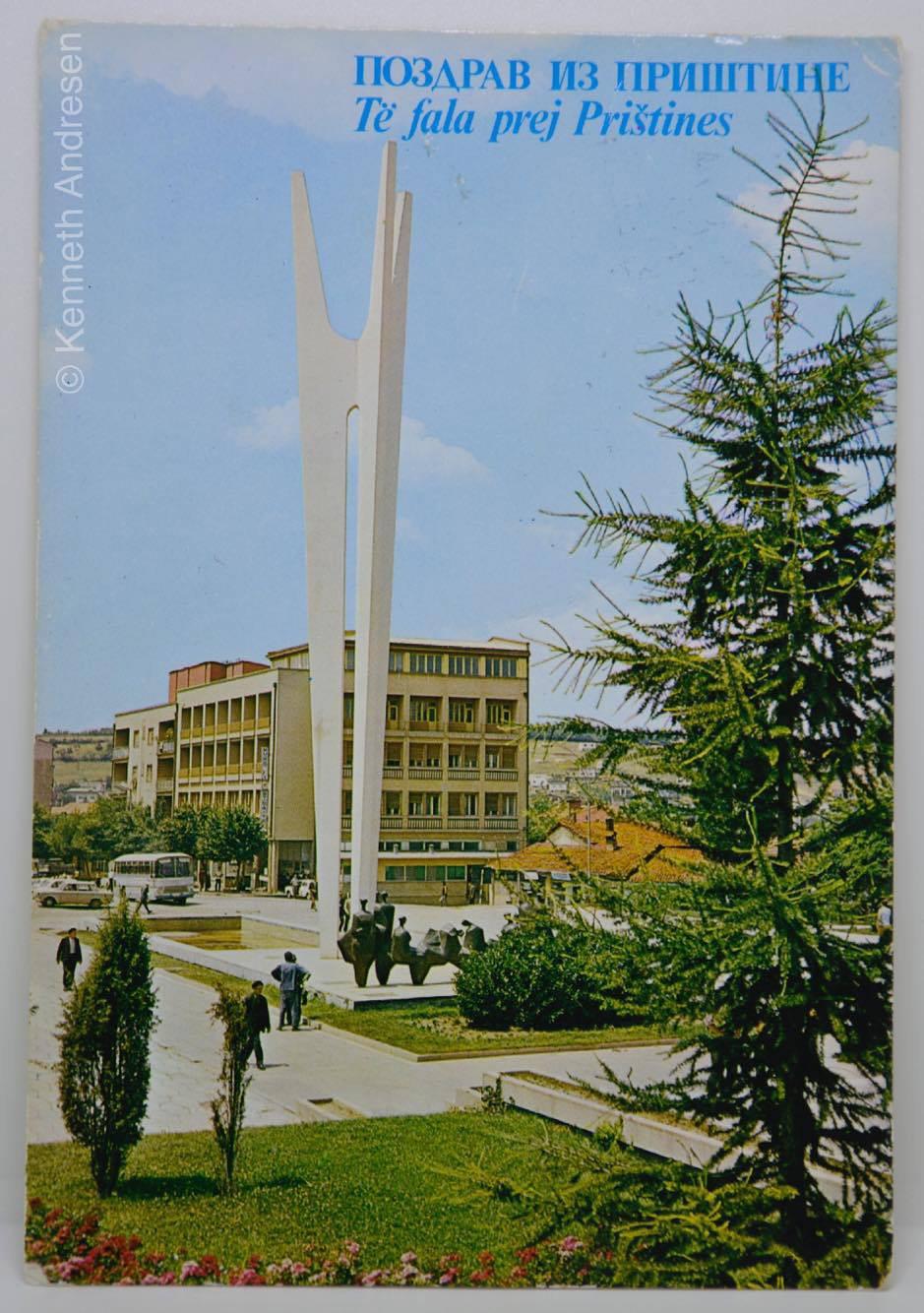

Fig 2

Fig 3

Fig 4

Fig 2-7 The beginning of the transition of Prishtina from a town with Ottoman architectural elements to a modern city of Yugoslavia

Fig 2 Residential Area (Mahalla), Prishtina ime

Fig 3 Demolishing the Ottoman bazaar, Prishtina Public Archipelago

Fig 4 Postcard from Prishtina, Kenneth Andersen

Fig 5 Taking down the bazaar, Prishtina Public Archipelago

Fig 6 SkyscraperCity. (2013, January 29). Foto të vjetra të Prishtinës | Prishtina Retro [Online forum post]

Fig 7 Postcard from Prishtina, Kenneth Andersen

Fig 5 Fig 6

Fig 7

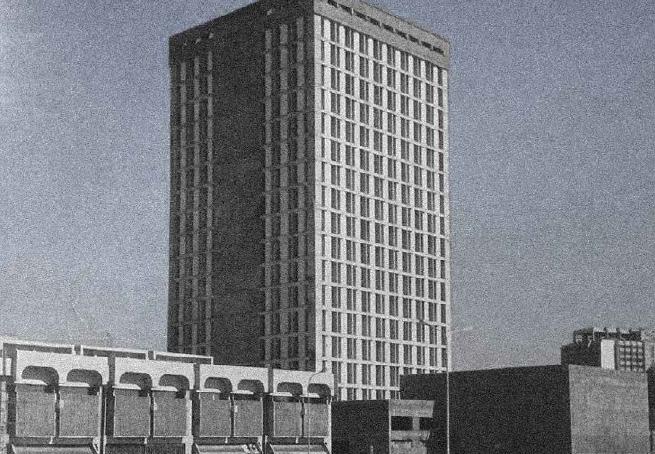

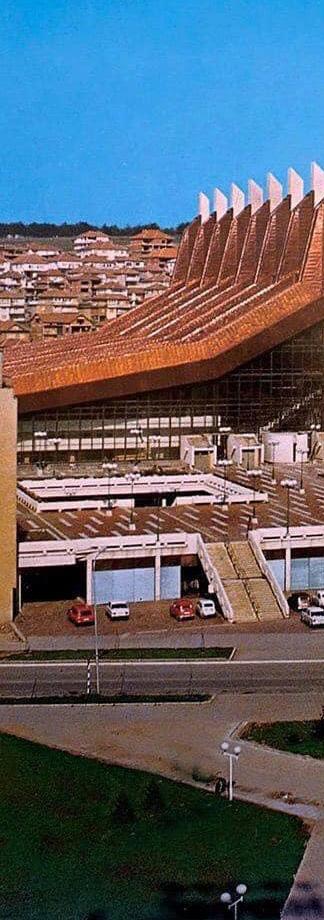

Fig 8, Fig 9

Fig 10, Fig 11

Fig 12, Fig 13

Fig 8-13 New structures built during the Yugoslavian period including the Central Bank, Grand Hotel, Germia Department Store and the National Library

Fig 14, Fig 15

Fig 16

Fig 14-16

The construction of the Palace of the Youth and Sports

Fig 17

Fig 18

Fig 19

Fig 17-23 Images showing the aftermath of the war and the chaos of unplanned construction

Fig 20

Fig 21 Fig 22

Fig 23

The Palace of Youth and Sports stands as a mirror to Prishtina’s evolving urban identity—at times shaping it, at times fragmenting it, and more recently, attempting to reconcile with it. As urban development unfolded in waves of ideological imposition, exclusion, post-conflict ambiguity, and grassroots reclamation, the Palace operated as a physical and symbolic node within each shift. My intention through this project and analysis was to understand how much a single building can reveal about the broader urban narrative of a city. That is why I’ve chosen to trace the Palace’s transformations in such detail—because in doing so, we uncover not just architectural changes but social, political, and civic shifts embedded in concrete and space. Across these phases, the Palace of Youth and Sports operated alternately as a tool for socialist integration and modern civic identity (1977–1990), a symbol of exclusion and suppression during Serbian control (1990s), a fragmented, contested public space during postwar reconstruction (2000–2018); and a site of public memory and civic activism, with attempts to reclaim and restore its role as a central institution in Prishtina’s urban identity (2018–ongoing).

In its socialist inception (1977–1990), the Palace was conceived not merely as a civic structure but as a monumental anchor for a modern, integrated urban life. Strategically placed in the heart of Prishtina, it embodied the Yugoslav urban ideal of polyfunctionality: combining sports, culture, education, and youth engagement in a singular architectural gesture. It served as a civic center in both form and function, fusing public space with ideological ambition. The building’s design and openness aligned with broader socialist urban planning narratives—aiming to socialize citizens, foster collectivity, and spatially manifest the identity of a multi-ethnic Yugoslavia.

This trajectory was violently disrupted in the 1990s. With the onset of Serbian repression, the Palace’s function was reterritorialized— it became a tool of ethnic exclusion, where Albanians were denied access to most of the space. From a civic monument to a site of imposed segregation, it now embodied an urban rupture: a structure that had once symbolized civic belonging was turned into an architecture of erasure. It no longer participated in the life of the city as a unifying civic platform but stood as a daily reminder of imposed disintegration. In the post-war period (2000–2018), the Palace

entered a liminal urban role: physically present yet functionally degraded, symbolically potent yet ignored. Urban narratives during this time were characterized by transitional governance, attempts at privatization, and a lack of coherent planning, which reflected in the building’s deteriorated condition and unclear ownership. Rather than reintegrating into a post-war civic identity, it became a monument in crisis, one that disrupted the possibility of urban cohesion by standing as a ghost of past ideals and a victim of bureaucratic fragmentation. Its decline was symptomatic of broader urban dysfunction—poor infrastructure, contested public ownership, and lack of long-term vision.

However, since 2018, the Palace has once again entered the civic conversation, this time not through top-down imposition but through bottom-up activism. Civil society’s opposition to privatization and the Municipality’s acquisition of the building marked a moment of public reclamation. At the same time, new plans tied to the 2030 Mediterranean Games gesture toward reintegration into urban planning narratives, concerns about transparency and inclusivity reveal unresolved tensions. The Palace continues to embody the struggle between development and erasure, memory and modernization, people and politics.

Thus, tracing the Palace’s transformations reveals not only architectural adaptation but also urban biography. It teaches us that buildings are not static objects in the city—they are protagonists in its story. The Palace of Youth and Sports has, at various times, aligned with, interrupted, and redefined the urban narrative of Prishtina. It remains both a barometer and a battleground for the city’s past and its aspirations.

Fig 24

Fig 24 Photograph taken by author

Golden era concerts, sports, exhibitions, youth activities, multi-generational activities

partial function, complex under Serbian administration multiple uses

1977 1981 1990 1999 2000

18 November, 1977 Palace of Youth opened to the public

cultural and artistic activities educational and instructional activities

the foundation for the multi-purpose Hall

opening of the multipurpose halls

exclusion process begins

albanians from Kosovo are not allowed to use most of the building complex anymore, only the stores due to the suppression of Kosovo’s autonomy

End of War in Kosovo: building partly damaged

exclusion process ends, institutions begin to become rebuild the complex becomes under the administration of UNMIK

25 February, 2000

half of the building catches fire and burns for around 5 consecutive days in the city centre the large multipurpose hall heavily damaged

fueledbypersonal interestmostly

attempts to reconsider and bring back the “glory” of the institution some honest reflective of the stateofthebuilding mostly ignorant of the complex history of the building

a few investments to renovate damaged parts of the building, so that more damage is not caused

stag(nation) ?

reconstruction of the roof, facade, glass blocks, domes, but the multi-purpose hall remains untouched

the building is taken under the management of the Kosovo Trust Agency (KTA), later by Kosovo Privatization Agency (KPA), one of most known corrupt agencies

2018 2024

due to the reaction of the people to privatization attempts, the building is finally taken under the management of the Municipality of Prishtina

payment of debts owed by the enterprise

together with the Ministry of Culture

the decision to host the Mediterranean Games 2030 in Prishtina

the decision to renovate the multipurpose hall

2025

Feasibility Study has been undertaken with the contribution of the European Bank

the call for a conceptual project follows but no other transparency of the process for now

When considering the primary “stages” within this building site, one is immediately drawn to its diverse and layered functions.

These include the Abandoned Hall (currently repurposed as a parking lot), the Sports Hall and associated facilities, the commercial area with shops, cafes, and restaurants, administrative offices, the Youth Center, the public platform on the first floor, and the external spaces — the front plaza with the Newborn monument, the rear parking lot, the adjacent stadium to the north, and the main street to the south, bordered by the former Rilindja building and the current Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Innovation. Each of these functions generates distinct patterns of movement and occupation. Yet, despite their activities, much of the complex exhibits signs of physical deterioration. This decay, however, is not necessarily a negative phenomenon. Instead, it reveals a powerful sense of temporality — the visible passage of time embedded in the architecture — which contrasts sharply with the newer developments surrounding the site, such as the Dragodan neighborhood and the Pejton area, often referred to as Prishtina’s new financial district. One of the site’s greatest assets is its location. Situated in the center of Prishtina, it has long served as an iconic urban landmark. Its distinctive roofline is visible from multiple vantage points, acting as a constant visual anchor in the city.

As such, this architectural “stage” is in continuous view of passersby, reinforcing its symbolic presence in the urban fabric. However, the rapidly changing context around the site presents challenges. The fast-paced development diminished the building’s relevance.

While it remains architecturally significant, the influx of new structures and functions around it has reduced its former uniqueness. From a volumetric analysis, the building still dominates the surrounding area. Its massing is large compared to nearby structures yet the former Rilindja building is somewhat of the same scale, as it was built during the same period as well. The site is accessible by cars on all sides and it shares proximity with the stadium. Historically, an underground river runs behind the building, which was covered during the Yugoslav era, reportedly for hygienic reasons. The site’s central location has attracted various public institutions over time. Surrounding land use includes educational, commercial, residential, mixed-use, and religious functions — further highlighting the complex, multifunctional nature of this urban stage.

While its central location, multiple access points, and proximity to key city landmarks such as the main square and university campus enhance its connectivity and relevance, these assets are offset by several challenges. The overwhelming presence of cars—especially in the rear parking lot—and ongoing surrounding construction contribute to a fragmented and often inaccessible experience. The lack of elevators and poor accessibility for people with disabilities further limit inclusivity, while minimal green space reduces opportunities for ecological and social engagement. Still, the site offers moments of relief, such as a quiet elevated platform, and supports a rich coexistence of functions within a single complex.

Fig 25

Fig 26

Fig 25-26 Photographs taken by author

Fig 27

Fig 27 Photograph taken by author

Fig 28, 29

Fig 30,31

Fig 32,33

Fig 34,35

Fig 28-35 Photographs taken by author

Fig 37

Fig 36-39 Photographs taken by author

Fig 40-43 Photograph taken by author

Fig 40, 42

Fig 40, 43

Fig 44 Photograph taken by author

The Abandoned Hall tells a dramatic and visible story of decline. Damaged by fire, the remains are stark — with a gaping hole still present to this day. Despite some makeshift repairs to render parts usable, the sheer extent of destruction remains shocking, especially in such a central city location. The hall now functions as a parking lot,

with open public access. While upper floors are locked and inaccessible, the main area around the hall remains freely accessible. The original ground floor, destroyed by the fire, now serves as a de facto basement level where cars are parked — ironically restoring part of its original function.

The Sports Hall is characterized by labyrinthine corridors, with athlete access points either through the ground-floor commercial zone or from the public platform. Although the spatial layout remains largely unchanged, recent investments have revitalized the sports facilities themselves. These upgrades were crucial, considering the heavy use of the space by athletes and sports organizations.

Fig 47, 48

The Commercial Area of the complex is in a noticeably deteriorated condition. Lower rents are used to attract businesses, but several units remain empty due to the site’s declining importance. Despite this, the area still acts as an

important urban connector — an “urban corridor” — allowing for pedestrian flow across parts of the city, even when the internal functions themselves are not actively in use.

Drw 22

Fig 49, 50

These Administrative Offices share the same complex access routes as the Sports Hall. While still functional, they suffer from a lack of

maintenance, contributing to the general sense of neglect within certain parts of the complex.

Drw 23

Fig 51, 52

The Youth Center is one of the most active and adaptable stages within the complex. Its more manageable scale has allowed it to host a variety of functions over time. Today, while not fully in use, several spaces remain active — the amphitheater is currently used temporarily by

the National Theater, while multipurpose halls accommodate conferences, performances, and fairs. The flexible design of the first floor allows for diverse configurations, making it suitable for a wide range of events and activities.

Drw 25

Fig 53,54

The first-floor Public Platform, somewhat shielded from surrounding vehicular noise, offers a quiet, elevated urban space. It serves multiple, sometimes conflicting roles: a retreat for some, and a hidden stage for others who engage in more illicit or private activities such as drinking or drug use. The pervasive graffiti adds layers of texture and temporality to the building’s surfaces. Though the platform is accessible via three stairways, it is mainly the front entrance that is actively used, particularly during public events or by individuals seeking solitude.

Drw 26

Fig 45-56 Photographs taken by author

Fig 55,56

Fig 57, 58

Fig 59, 60

Fig 61, 62

Fig 63, 64

ACTORS

The primary users—or actors—of the site are those who engage with its functions on a daily basis. These actors are shaped by the diverse range of activities that occur within the building complex, making it a multifunctional urban node.

A significant portion of the site is dedicated to sports and physical activity. In addition to the main sports hall—which accommodates basketball, volleyball, handball, and other exercises—there are specialized areas for gymnastics, boxing, ping pong, martial arts, taekwondo, and general fitness. These are supported by essential facilities such as changing rooms, doping control stations, and a sports medicine unit.

The complex also houses various administrative offices and club headquarters, including those of the astronomy and golf clubs, as well as specialized institutions like the Chess Federation and the Association of Architects of Kosovo.

Commercial activity is supported through the presence of shops, cafés, and restaurants. Educational functions are represented by an English language school and a guitar school. Furthermore, the site currently serves a temporary cultural role by hosting the National Theatre, which uses several interior spaces for rehearsals and administrative functions while its primary building is under renovation.

A public library within the complex is currently being renewed, while the dance and ballet school remains actively attended. Multi-purpose halls located in the youth center serve as adaptable spaces for a variety of events, such as conferences, classical music performances, and fairs. Meanwhile, the site also includes

informal functions: the abandoned sports hall and the unfinished rear section of the complex are currently repurposed as parking lots, predominantly used by employees working in the vicinity.

These diverse functions give rise to a varied group of users. Core daily actors include athletes, administrative staff, commercial employees, club participants, and students of the educational programs. More recently, theatre professionals have become prominent users due to their ongoing activities within the complex. On weekdays, parking activity indicates the presence of nearby office workers, while casual users—those who pass through the building as an urban corridor— add another layer of transient occupation. Occasional users include those attending specific events such as theatre performances, sports competitions, or public gatherings. This wide spectrum of actors reflects the site’s complex programmatic structure and underscores its importance as a dynamic, multi-use urban space.

Fig 57-62 Photographs taken by Blerta Kambo, received personally Fig 63-64 Photographs taken by author

This site is layered with memory — from its inception in 1974 to the many events and transformations it has witnessed over time. In researching the site’s evolution, I approached each space by investigating its past condition and current state. This comparison helped me understand how certain areas changed over time, whether in function, accessibility, or symbolism. My primary resources included old newspapers and historical photographs, which provided insight into how the space was envisioned and used during different eras.

Across all six spaces, the acts of the past and present unfold in different ways: some remain tightly connected (like the Sports Hall or Youth Center), while others are marked by disruption, decline, or transformation (like the Abandoned Hall or Shops). The site, layered in events and symbolic meanings, offers not just architectural history but a stage of collective memory, trauma, resilience, and adaptability.

The Palace of Youth and Sports is not a static monument — it is a living archive of urban evolution. Its multiple “acts” are not only scenes from a past performance but active elements shaping how the city continues to use, interpret, and negotiate its spaces today.

Fig 65, 66

The Palace of Youth and Sports photographed at different time periods

Fig 65 Prishtina OLD. “Pallati i Rinisë dhe Sporteve / Youth and Sports Palace.” Facebook,

Fig 66 The Nomad Magazine, Mayor of Prishtina article

Abandoned Hall

Currently repurposed as a parking lot due to severe fire damage in 2002, the Abandoned Hall was once a significant multi-purpose event space. This is evidenced by the still-standing concrete tribunes, which reveal the original design for hosting large audiences.

After the fire, the floor collapsed, exposing the basement — which, interestingly, was originally also intended for parking. Today, the basement partially resumes that role, but the now fully open vertical space redefines the entire volume of the hall.

The fire, which destroyed the wooden substructure holding the copper roof, left the steel skeleton completely exposed. The municipality later intervened, reconstructing the roof and enclosing the space externally. However, the interior devastation was never fully addressed, preserving the rawness and rupture caused by the fire. This duality — restored facade hiding a destroyed core — is telling of the building’s unresolved condition.

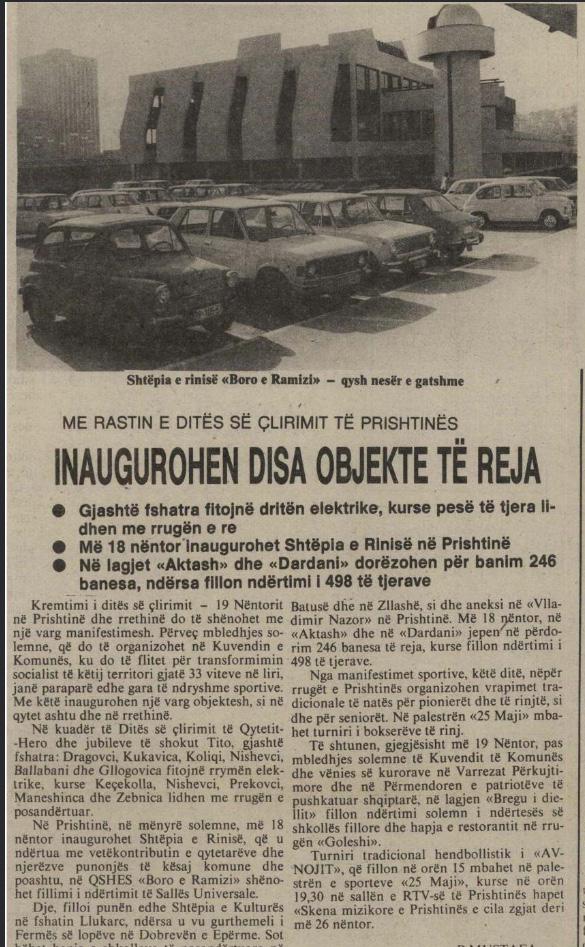

Historical newspapers from the time of the complex’s inauguration describe this hall as the premier venue for major sports and public events. The original architectural plans emphasize its multi-functional potential, designed to accommodate a wide range of activities.

The “act” of the past and the “act” of the present here feel disconnected. The damage, combined with the absence of a clear vision for its renewal, left the Abandoned Hall in a suspended state — a fragment of the past, caught in architectural limbo.

Fig 68 Photograph taken by author

Fig 67 Archival newspaper excerpt from the National Library in Prishtina, photographed by the author Drw

Fig 67

One of the possible use configurations of the Multi-Purpose Hall

Fig 69 Original floor plan from the Palace of Youth and Sports archive, photographed by the author during site research

Fig 70-71 Archival newspaper excerpt from the National Library in Prishtina, photographed by the author.

Fig 72 Archival newspaper excerpt from the National Library in Prishtina, photographed by the author Newspaper title translated “As the Palace burned, so did thousands of memories held by its citizens.”

Fig 70,71

Fig 73 Fig 74

Fig 73 Photo retrieved from Oral History of Kosovo website

Fig 74 Photograph retreived from Fadil Pacolli, employer at Palace of Youth and Sports.

Fig 75 Fig 76

Fig 75, 76 Photographs taken by author

Sports Hall

Unlike the abandoned section, the Sports Hall continues to fulfill its original function. Despite minor modifications, the hall and its facilities are still used by athletes and sports associations today. Articles from the building’s early years describe a similar range of sports activities, suggesting a strong continuity between past and present. In this case, the act of the past remains intact — carried forward in almost unaltered form into the present.

Fig 79

Fig 80

Fig 77,78 Photographs by Blerta Kambo, personally retrieved by the author

Fig 79 Archival newspaper excerpt from the National Library in Prishtina, photographed by the author.

Fig 80 KosovaPress. (2023, April 13)

Commercial

The commercial area on the ground floor is visibly deteriorated today. Comparing the current condition to past plans and newspaper descriptions, it’s clear that this space once held a more diverse program. In addition to shops, the past included an art gallery and a bowling alley, contributing to a livelier, more dynamic ground floor experience.

While the physical state has declined and some of its functions have disappeared, the role of the

space as a connector across city zones remains. Then and now, it links parts of the city — even though today it does so more out of habit and geography than active commercial engagement. The connection between past and present here remains, however with reduced vitality.

Fig 81

Fig 82

Fig 81 Original floor plan from the Palace of Youth and Sports archive, photographed by the author during site research

Fig 82-84 Photographs taken by author

Administrative Offices

The administrative offices occupy the same spaces as originally planned, though they are now accessed via complex, labyrinthine corridors. Today, fewer offices are in operation than in the past. This continuity is therefore partial — the original configuration is intact, but with diminished usage and altered administrative structure.

Drw 23

Fig 86

Fig 86 Original floor plan from the Palace of Youth and Sports archive, photographed by the author during site research

Fig 85 Photograph taken by author

Finding the offices in the original floor plan

Youth Center

The Youth Center exemplifies continuity through adaptability. Though the functions hosted here have changed over the decades, its core purpose as a multi-use space has remained intact. Historical plans deliberately leave its main halls undefined — open, adaptable, ready to accommodate various cultural and social activities.

This versatility continues today. Parts of the center — such as the amphitheater (currently used temporarily by the National Theater) and various multi-purpose rooms — are regularly used for conferences, performances, and fairs. While the specific clubs or organizations have changed, the essential act remains: a space constantly being reconfigured for new uses.

Its more manageable size likely made it easier to maintain and adapt over time, especially

compared to other parts of the complex with more rigid programs.

Through archival newspaper records, I got to learn that the Youth Center was also the first part of the complex to be completed and used — beginning operations three years before the rest of the building. This early activation, amid the construction of the larger project, likely created a lasting impression on the city’s residents. Given the rarity of projects of such scale in Kosovo at that time, its growth from blueprint to built form must have felt monumental — a collective memory deeply rooted in the city’s urban psyche.

Fig 87, 88 Photographs taken by author

Fig 87

Fig 88

Fig 89 (2023, April 7). Palace of Youth and Sports – Pristina, Kosovo, built in 1977, multipurpose building [Online forum post]. Reddit.

Fig 90-92 Archival newspaper excerpt from the National Library in Prishtina, photographed by the author.

Translated Titles:

Fig 90 “Let’s preserve Boro and Ramiz”

Fig 91 “The inauguration of Boro and Ramiz Youth Center”

Fig 92 “The inauguration of new buildings”

Fig 89

Fig 92

Fig 90, 91

Fig 93

Fig 94

Fig 93 Manifesta 14 Prishtina. Photograph of Astrit Ismaili performing LYNX at Manifesta 14, Palace of Youth and Sports, Pristina, 2022

Fig 94 Gazeta Express. (2024, April 8). Palace of Youth and the Public Housing Enterprise decide to renovate the “Red Hall”

Public Platform

The public platform continues to serve as a place of retreat and gathering. Whenever I visit, I find people quietly seated, enjoying a rare sense of calm above the noisy streets.

Over the years, I have witnessed several public events held here — including outdoor concerts, beer festivals, and Pride Parade celebrations. Historically, too, the platform was intended as a public gathering space, and that intention remains fulfilled today.

Yet, upon closer observation, this platform also reveals the “wound” of incompletion. On its

backside, traces of the unfinished parts of the Palace of Youth and Sports become visible — physical reminders that the full vision for this complex was never realized.

This wound is echoed across the street, visible from the platform of the Grand Hotel, which sits adjacent to the Palace. While the wound is partially hidden from within the Palace platform itself, it becomes fully visible from the side view — exposing the abrupt halt in construction and reminding us that this space, though heavily used, remains a fragment of a larger, unfulfilled idea.

Fig 95

Fig 96

Fig 97, 98

Fig 95 Opening event of Manifesta 14, Prishtina. Retrieved from Manifesta website

Fig 97, 98 Photographs taken by author

Fig 96 Original Project photographed from Arber Sadiki’s Public Buildings in Prishtina: 1945-1990, Social and Shaping Factors”.

Drw 27 Isometric Diagram by author | Public Platform as an Urban Wound

Fig 99

Fig 100

Fig 101

IMPROVISED ACTS

This section explores the temporary uses within the building—uses that diverged from its original purpose due to rented spaces being repurposed for different activities. While I don’t have full visibility into the leasing processes behind these changes—each case varied based on timing and spatial extent—I’ve attempted to trace how these alternate uses evolved over time.

I refer to these as Improvised Acts because they involved creatively adapting a space to support functions it was never designed for. In some cases, this improvisation meant physical modifications to the space. In others, it simply involved inserting new activities into the existing structure without altering it significantly.

I’ve categorized these improvisations into the following two categories:

Temporary Uses Ignorant of the Existing Space

These interventions prioritized function over context, focusing solely on enabling the new activity—often at the expense of acknowledging the site’s architectural or historical character. Examples include:

A high school (up to 2017) operating in the Youth Center of the complex

A current disco club in the northeastern corner

A sushi restaurant in part of the Youth Complex Various disco bars in the same block

A paintball zone in the abandoned section

Temporary Uses That Reflected on the Existing Spaces

These interventions were more intentional about engaging with the spatial and historical context, either because it enhanced the new function or was integral to the experience. Examples include: Prishtina Mon Amour (2012)

The Manifesta Biennial (2022)

Song festivals (2023,2024)

Raves (over the years)

Despite their differences, both categories leave behind traces—both physical and experiential— that inform how we understand the space and how it might evolve.

Fig 99-100 Raves in the Palace of Youth. Retrieved from Servis Facebook page

Fig 101 Abandoned section used for paintball. Image received from collection of Qendrim Gashi on Abandoned Spaces

What We Learn from the Isolated Uses

The first category teaches us that highly isolated uses can create a kind of spatial amnesia. For example, when visiting a disco club, the building only becomes apparent during the transitions— parking, entering, exiting, or taking breaks. Inside, the space is deliberately detached from its surroundings, forming a new, insular world. The same applied to my personal experience attending high school in this building: I rarely

understood where I was in relation to the whole. Dark corridors, blocked staircases, and sealed-off halls were simply part of the daily routine—never questioned, never contextualized. Even courses like ‘Interior Design’ failed to teach us to engage with our lived space. Still, this use brought life to the site—students flowing in and out—but it was life confined behind tuition fees and locked doors.

Fig 102

Fig 103

Fig 104

Fig 105

Drw 28-31

Fig 102 American School of Kosova. Image retrieved from ASK facebook page

Fig 105 Paintball Head to Head Prishtina. Image received from Paintball Head to Head Facebook page

Fig 103,104 Photographs taken by author

Drw 28-31 Isolated Temporary Uses

What We Learn from Reflective Uses

In contrast, the second category invites people to interact with and reflect on the building itself. Whether through intentional design (as with Manifesta or Prishtine Mon Amour) or incidental outcomes (as with the song festivals), these uses create moments of spatial awareness. The song festivals, for example, took place in an abandoned hall that couldn’t be ignored or overridden. The structure’s presence demanded interaction, and

in doing so, evoked a consciousness of place— even if that wasn’t the organizers’ original goal. These acts, whether isolated or reflective, offer lessons in how space can be reactivated, repurposed, or even reimagined—and how these processes shape our relationship to the built environment.

Fig

Drw 32-35

Fig 105, 106, 107 Raves in the Palace of Youth. Retrieved from Servis Facebook page

Fig 109 Willing to Be Vulnerable –Metalized Balloon V4, 2015_2020, © Lee Bul. Manifesta 14, Prishtina

Fig 108 Prishtinë – Mon Amour 2012. Image retrieved from Prishtine - Mon Amour Facebook page

Drw 32-35 Reflective Temporary Uses

Part 2: Actor – Engaging with the Site shifts from observation to interaction. Here, I explore my own embodied sensory and emotional response to the site (2.1), then integrate dialogues from interviews (2.2), and then investigate methods of participatory memory-gathering to reconstruct collective narratives (2.3). This part concludes with a critical inquiry into spatial authorship and agency—”Who directs the scene?” (2.4).

EMBODIED RESPONSE

Sensory and Emotional Encounter

“In this building I … ”

When thinking about this building—compared to many other places in the city I grew up in—there’s an entire thread of memories that pulls me back to it. The Palace of Youth and Sports has been a constant presence throughout my life, holding different meanings at different times. Many school programs and performances happened there during my childhood. Later, it became even more personal, as I attended high school in a private institution that occupied part of the Palace’s Youth Center.

Every morning, I’d walk ten minutes to school. My route passed by the National Library—a building I never entered to study, but often stared at with a quiet, unexplainable feeling. Then I’d pass the main entrance of the Palace and slip into the ground floor, entering a space that had been redefined for education. Looking back, it surprises me how little I thought about the building itself. Even after deciding to study architecture, I remained unaware of the significance of the space I moved through daily. The existing environment didn’t feel important then; it was just the backdrop to my everyday life.

This contrasts sharply with how my parents spoke about the building. For them, the Palace represented a different era—a time before the war and before the separation. They often spoke with admiration about what the building used to be: a vibrant hub with sports facilities, concerts, and communal activities. It felt like they were describing a different reality altogether. I couldn’t quite grasp how conditions could worsen with time, yet that seemed to be the case.

We often parked in the abandoned part of the complex, then walked through a narrow corridor with stairs to reach the commercial section, where

the shops were still operating. That strange route—passing from a neglected and crumbling area into a lively retail zone—always struck me. We’d often get ice cream there and either shop or wander into the city center before returning to our car. That physical passage—from destruction, through tightness, into openness—seemed to carry an emotional logic I couldn’t name at the time.

One of the most powerful memories tied to the building was the opening of Manifesta in Prishtina. It felt extraordinary to see the public platform activated again—this time filled with people of all ages, re-engaging with a space that had long been neglected. Unlike previous festivals held there, this one was free and accessible. The openness of the event was moving. All the beloved artists of that time were performing, and unexpectedly, I ran into my parents there. It was a rare moment of shared presence across generations in a public space that belonged to all of us. I remember thinking then about the potential of reflection in public spaces—how design and programming can create powerful encounters, and how healing it felt to occupy this space collectively and freely. And yet, the building always held something unsettling for me. Maybe it was the labyrinthine layout. Maybe it was the ghost of a reality I never fully experienced—the one my parents always described. Or maybe it was simply the deterioration, the visible layers of time that brought fear rather than curiosity. Whatever it was, even when the building called for reflection, I often chose to ignore it.

Years later, after completing my architecture

Drw

studies and returning to Prishtina, I found myself more attuned to the city’s rhythms—and overwhelmed by them. The pace, the chaos, the constant construction all made me crave silence. Ironically, it was the older, forgotten buildings— the ones from “a different time”—that offered this stillness. The National Library and the Palace of Youth and Sports shared this quality. Their decaying yet steady presence felt honest. In a city of rapid, sometimes disorienting change, these buildings didn’t lie. They exposed the truth of time and wear. And somehow, this rawness brought comfort.

But that truth I felt at the Palace lingered with me. It made me wonder—if this building meant so much to me, what did it mean to others?

This became the starting point of the next phase of my research. I began asking questions. I reached out to people who might have a more reflective connection to the site—architects, artists, renters, urban planners, performers, family members, friends. I spent two weeks on site, speaking with anyone willing to share their story. I also created a Google Form and shared it widely, hoping to gather collective memories and test how people respond when invited to reflect on a building they

may have long taken for granted. spaces—how design and programming can create powerful encounters, and how healing it felt to occupy this space collectively and freely. And yet, the building always held something unsettling for me. Maybe it was the labyrinthine layout. Maybe it was the ghost of a reality I never fully experienced—the one my parents always described. Or maybe it was simply the deterioration, the visible layers of time that brought fear rather than curiosity. Whatever it was, even when the building called for reflection, I often chose to ignore it.

Years later, after completing my architecture studies and returning to Prishtina, I found myself more attuned to the city’s rhythms—and overwhelmed by them. The pace, the chaos, the constant construction all made me crave silence. Ironically, it was the older, forgotten buildings— the ones from “a different time”—that offered this stillness. The National Library and the Palace of Youth and Sports shared this quality. Their decaying yet steady presence felt honest. In a city of rapid, sometimes disorienting change, these buildings didn’t lie. They exposed the truth of time and wear. And somehow, this rawness

Drw 37 ‘ My daily walk to school’, sketched by author

Though I lived in the city center for most of my life, it eventually became unbearable. The noise, density, and constant activity led my family to move to a quiet neighborhood on the outskirts— where everything is more organized and the intensity of the city feels far away.

But that truth I felt at the Palace lingered with me. It made me wonder—if this building meant so much to me, what did it mean to others?

This became the starting point of the next phase of my research. I began asking questions. I reached out to people who might have a more reflective connection to the site—architects, artists, renters, urban planners, performers, family members, friends. I spent two weeks on the site, speaking with anyone willing to share their story. I also created a Google Form and shared it widely, hoping to gather collective memories and test how people respond when invited to reflect on a building they may have long taken for granted.

hiding place

high school

ballet school

performance

sports

confusion

nostalgia for an unlived past

If the building is as many things to me, what could it be to others too?

Fig 110

Fig 110 Photograph taken by author during the conducted interviews

DIALOGUES

Interviews and Their Insights

Over the course of my two-week research trip in Prishtina, I had daily encounters that revealed new layers of meaning about the Palace of Youth and Sports. Being on-site every day allowed for spontaneous conversations—often sparked by curiosity from passersby who noticed me drawing or taking notes. These dialogues became a rich form of inquiry, connecting personal experiences with collective narratives and professional insights. Following are highlights from the people I interviewed —artists, planners, architects, cultural workers, and everyday citizens—each offering a unique lens into the building’s past, present, and possible futures.

These interviews, whether formal or just casual conversations over family dinners, always revealed different insights about the building. I began exploring it more deeply with my aunt, who used to be the Youth Chair in 1983-1984 and had organized many youth activities there along with the Palace of Youth and Sports staff. We started by looking through old plans together while having ice cream at Elida Patisserie, located in the commercial center of the complex.

As we walked around, entering each space would trigger a new memory for my aunt, which she shared as a story. Interestingly, while exploring, she also discovered parts of the complex she had never entered before, despite having been one of the main organizers of activities there.

“

Drw 38 Sketch created by author when reading through the submitted memories

The Boro and Ramiz complex represented innovation for its time. The sports hall in the early years after opening was transformed into an ice-skating rink during winter. I was a child then, but I clearly remember the joy

Another memory is the Eurovision-like contest

“In the early years after its opening, during winter, the sports hall was transformed into an ice-skating rink with a lifting system. Another memory is of the Eurovision contest, held for the first time in Kosovo. The basketball hall was transformed into a concert venue.”

“Later, my memories became connected to contemporary art and music, especially the first revitalization effort of the burned hall through the “Prishtina Mon Amour” initiative, which brought the hall back into the public’s attention. Then came the music events held in that very burnedout space — a fantastic backdrop during the time when techno and electronic music saw a boom in Prishtina.

The Boro and Ramiz complex represented innovation for its time. The sports hall in the early years after opening was transformed into an ice-skating rink during winter. I was a child then, but I clearly remember the joy we felt — unfortunately, that didn’t last long.

Inside the building, I was always struck by the atriums — rarely or never properly utilized or treated with the respect they deserved. As a typical example of 1970s Balkan architecture, it remains an iconic and irreplaceable part of Prishtina’s silhouette.”

Inside the building, I was always struck by the atriums — rarely or never properly utilized or treated with the respect they deserved. As a typical example of 1970s Balkan architecture, it remains an iconic and irreplaceable part of Prishtina’s silhouette.”

Then came the music events held in that very burnedout space — a fantastic backdrop during the time when techno and electronic music saw a boom in Prishtina.

“Later, my memories became connected to contemporary art and music, especially the first revitalization effort of the burned hall through the “Prishtina Mon Amour” initiative, which brought the hall back into the public’s attention.

“Boro and Ramiz was not just a building. It was a center of culture, sports, entertainment, and coexistence. It was part of my childhood and a source of joyful memories that I will always carry in my heart. Today, although it’s called the Palace of Youth, to me it will always be Boro and Ramiz — the place where dreams and the joys of an unforgettable childhood were born.”

“It was built through citizens’ contributions — 2% of their monthly wages. As architecture students, we used to visit the site during its construction along with our professors, including the project’s lead architect. The sports halls featured three-dimensional steel trusses — a marvel at the time.”

“It was built through citizens’ contributions — 2% of their monthly wages. As architecture students, we used to visit the site during its construction along with our professors, including the project’s lead architect. The sports halls featured three-dimensional steel trusses — a marvel at the time.”

“In the early years after its opening, during winter, the sports hall was transformed into an ice-skating rink with a lifting system. Another memory is of the Eurovision contest, held for the first time in Kosovo. The basketball hall was transformed into a concert venue.”

a center of culture, sports, entertainment, and coexistence. It was part of my childhood and a source of joyful memories that I will always carry in my heart. Today, although it’s called the Palace of Youth, to me it will always be Boro and Ramiz — the place where dreams and the joys of an unforgettable childhood were born.”

“As a child, I always saw the building as mysterious, even a little frightening, especially after hearing about a major fire. Still, my mother tried to create positive associations by telling me how many sports she used to practice there as a child — ice skating, karate, ping pong.”

cBoro and Ramiz was not just a building. It was

“The Boro and Ramiz complex represented innovation for its time. The sports hall in the early years after opening was transformed into an ice-skating rink during winter. I was a child then, but I clearly remember the joy we felt — unfortunately, that didn’t last long.”

“As a child, I always saw the little frightening, especially after Still, my mother tried to create me how many sports she used ice skating, karate, ping pong.”

“As a child, I always saw the little frightening, especially after Still, my mother tried to create me how many sports she used ice skating, karate, ping pong.”

“After the Kosovo war, it became could access the internet there groups also had the chance

“Bashkim Vëllazërimi” — my generation truly believed in this ideal.

“After the Kosovo war, it became a youth hub. Young people could access the internet there for a limited time. Many music groups also had the chance to rehearse in the building.”

Belief in Unity

“This complex, during my childhood, was not only a meeting point but also the centre of the city for us. Every weekend, my mother would send me there to take part in sports activities, as it was the only place that offered such opportunities. Later on, besides sports, dance classes were also added. That’s how my story with this place begins, covering the period when I was 7 to 12 years old. From the age of 12 to 16, I experienced my first concerts there, and afterwards, I started attending operas and basketball games. After turning 16, I became part of the events and activities organised there. It was a special feeling to spend time in a place that had once been a meeting point for my parents as well.”

“As a child, I always saw the building as mysterious, even a little frightening, especially after hearing about a major fire. Still, my mother tried to create positive associations by telling me how many sports she used to practice there as a child — ice skating, karate, ping pong.”

Elida Patisserie, my high school years spent in one of the corners of this complex, the sports halls, the (sad) locker rooms, rooftop parties, the concert halls (often neglected in terms of treatment toward artists), and the strange yet iconic architecture — both inside and out — with its yellow rectangular bricks and marble stairs. Sadly, I also remember the moldy smell and how the complex was often misused or neglected, never truly offered as a quality space for the youth. I wish I had more positive memories.”

“Bashkim Vëllazërimi” (Brotherhood and Unity) — my generation truly believed in this ideal.” was not just a building. It was culture, sports, entertainment, and was part of my childhood and a memories that I will always carry in although it’s called the Palace of always be Boro and Ramiz — the and the joys of an unforgettable born.” their monthly wages. during its construction project’s lead architect. trusses — a marvel at and Ramiz complex represented its time. The sports hall in the after opening was transformed ice-skating rink during winter. I was but I clearly remember the joy unfortunately, that didn’t last long. memory is the Eurovision-like contest Kosovo for the first time — the court was turned into a concert hall. now-burned spaces used to be the most for cultural events and concerts.

“When I first heard — and then researched — the history of the complex, I learned about Boro and Ramiz’s story. It’s a bit painful, very precious, and deeply thought-provoking.

“As a child, I always saw the building as mysterious, even a little frightening, especially after hearing about a major fire. Still, my mother tried to create positive associations by telling me how many sports she used to practice there as a child — ice skating, karate, ping pong.”

“I remember a masquerade party held on the rooftop for June 1st (possibly in 1995), walks with my parents through the toy shops, and the time part of the complex burned down. As I grew older, the strongest memories became NewBorn (for independence) and “Prishtina Mon Amour.” Peace between Albanians and Serbs, Boro-Ramiz, raves, and Elite ice cream — I’ve only been to one rave as a kid, but I remember the ice cream well.”

Still, my mother tried to create positive associations by telling me how many sports she used to practice there as a child — ice skating, karate, ping pong.”

“As a child, I always saw the building as mysterious, even a little frightening, especially after hearing about a major fire.

“When I first heard — and then researched — the history of the complex, I learned about Boro and Ramiz’s story. It’s a bit painful, very precious, and deeply thought-provoking.

Elida Patisserie, my high school years spent in one of the corners of this complex, the sports halls, the (sad) locker rooms, rooftop parties, the concert halls (often neglected in terms of treatment toward artists), and the strange yet iconic architecture — both inside and out — with its yellow rectangular bricks and marble stairs. Sadly, I also remember the moldy smell and how the complex was often misused or neglected, never truly offered as a quality space for the youth. I wish I had more positive memories.”

Peace between Albanians and Serbs, Boro-Ramiz, raves, Elite ice cream — I’ve only been to one rave as a kid, but remember the ice cream well.”

remember a masquerade party held on the rooftop for 1st (possibly in 1995), walks with my parents through toy shops, and the time part of the complex burned down. As I grew older, the strongest memories became NewBorn (for independence) and “Prishtina Mon Amour.”

THE QUESTION OF DIRECTION

Both parts of my analysis—first as an observer, then as an engaged actor—have raised more questions than answers. Yet, through the act of tracing, witnessing, listening, and inhabiting, I began to understand how I wished to continue interacting with the site. Embracing the complexity rather than resolving it, I started to see the building not just as an object to be fixed or reprogrammed, but as a living system of stories, contradictions, and possibilities. New dialogues and new modes of interaction revealed new potentials—quiet, emerging, and often hidden beneath the visible decay. Still, I must admit that at certain points, even as an architect-in-training, I struggled to imagine an alternative future for the building. Often, all I could see was an immense, empty shell. That realization felt heavy—not because it negated the emotional resonance I hold for the building, but because it suggested a kind of spatial paralysis. Caught between the weight of memory and the urgency of unmet needs in a young and fragmented country, I felt the impossibility of a singular, sufficient response. Any proposal risked either being too prescriptive or too abstract.