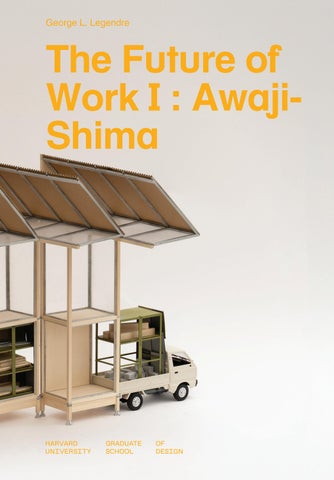

George L. Legendre

George L. Legendre

George L. Legendre

Awaji-Shima

This studio inaugurates a multi-year design research program into the future of work made possible by the generous support of the Nambu Family Design Studio Fund. At stake are the broad societal issues of employment, education, and work-life balance, as they relate to architecture, urbanism, and the environment.

The inaugural semester of the program focuses on the spaces of work and is sited on Awaji, an island located in Seto Inland Sea in central Japan. In the past few years, Awaji has benefited from generous outside investment in affordable housing, primary schooling, small-holding agriculture, and hospitality, catering to visitors and professionals in search of a better life beyond the city.

The projects presented in this report explore ways in which innovative factorymade spaces could support the island’s regeneration though a unique combination of hospitality, agriculture, skills training and social enterprise.

Studio Instructor

George L. Legendre

Teaching Assistant

Rishita Sen

Students

Keane Chua, Soroush Ehsani-Yeganeh, Elise Hsu, Ella Larkin, Regina Pricillia, Nicky Rhodes, Zachary Slonsky, Ann Tanaka, Esteban Vanegas Jr., Jeya Wilson, Lou Xiao, Ziyang Xiong

Final Review Critics James Dallman, Iman Fayyad, Jenny French, Jon Gregurick, Grace La, Mohsen Mostafavi, Keiko Okabayashi, Riho Sato, Allen Sayegh, Michael Voligny, Sarah Whiting, Adrian Wong

Preface George L. Legendre 2 Studio Overview George L. Legendre

42 Sake Workshop

Ziyang Xiyong

42 Asanokonda Residency

Zachary Slonsky

42 Moku San

Regina Pricillia

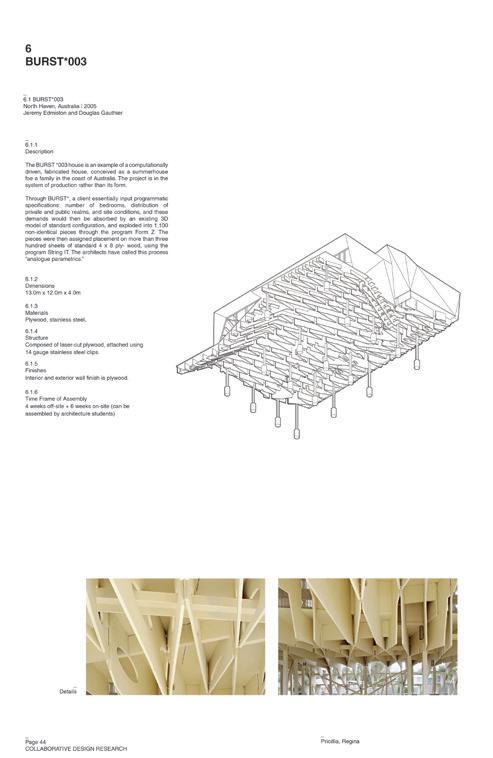

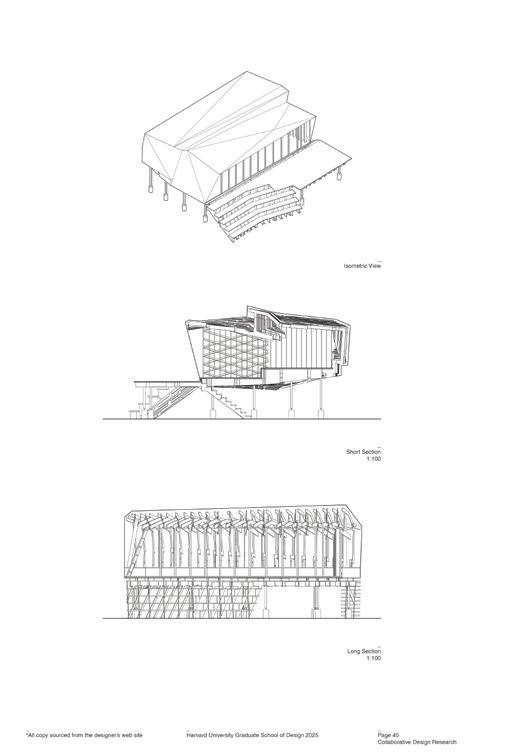

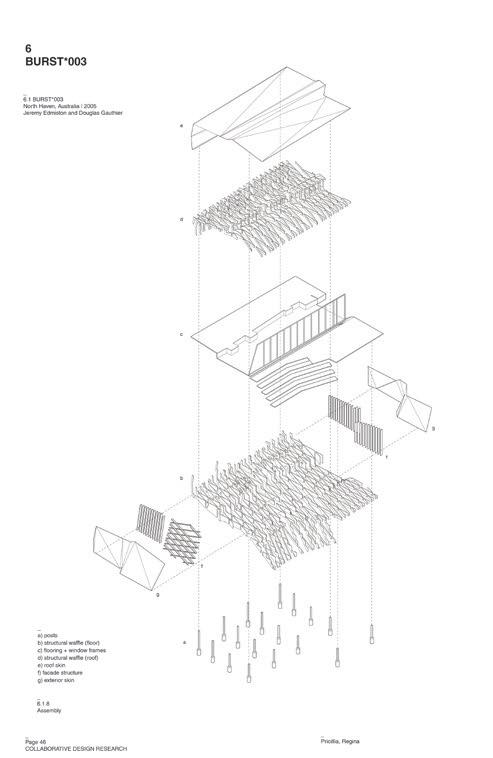

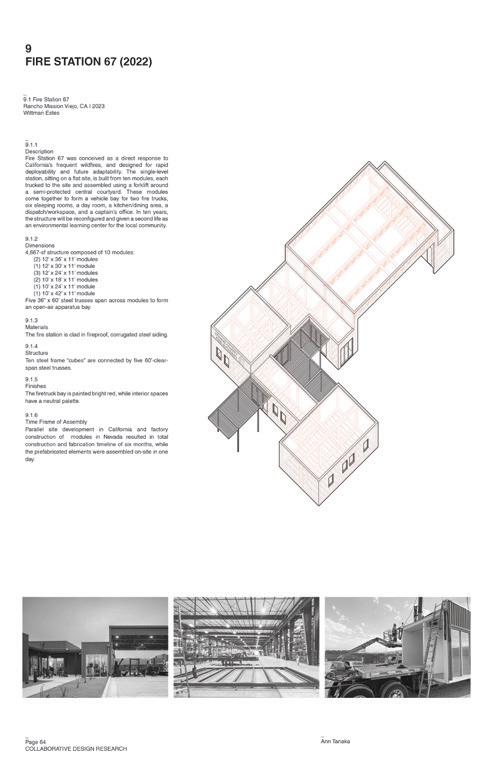

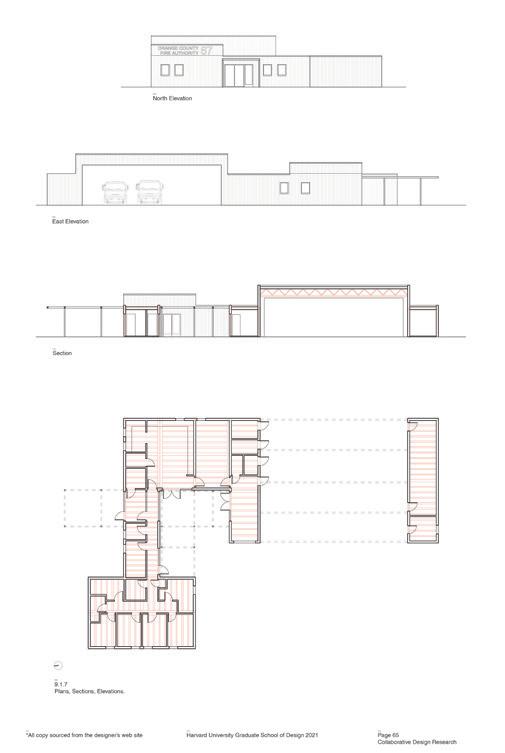

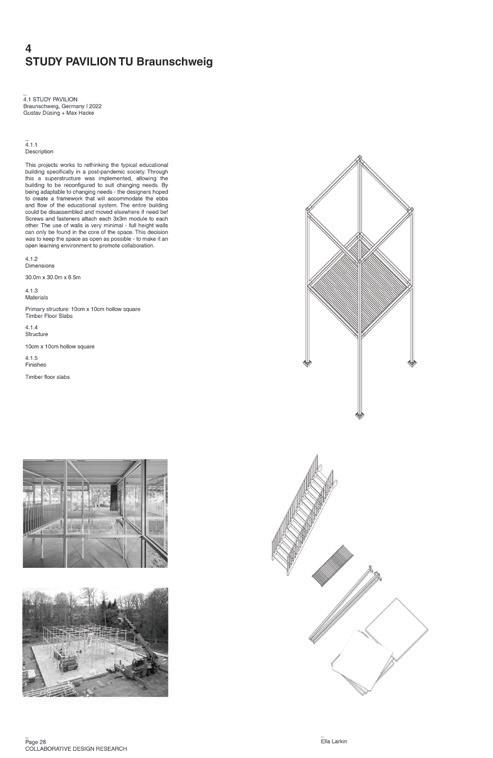

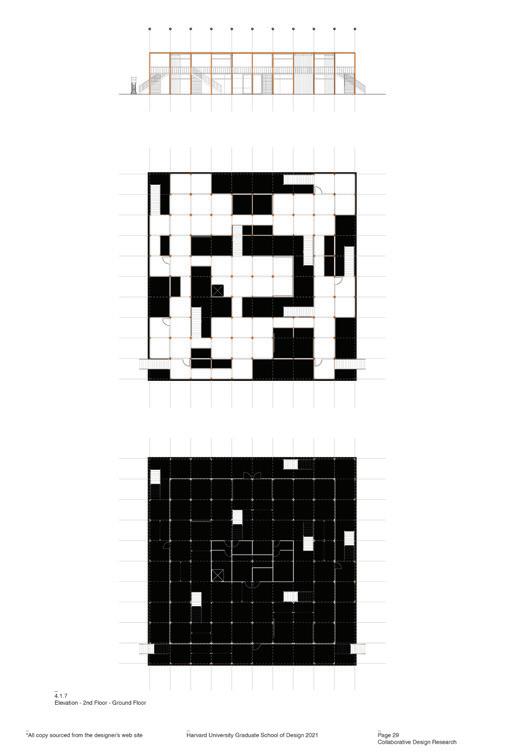

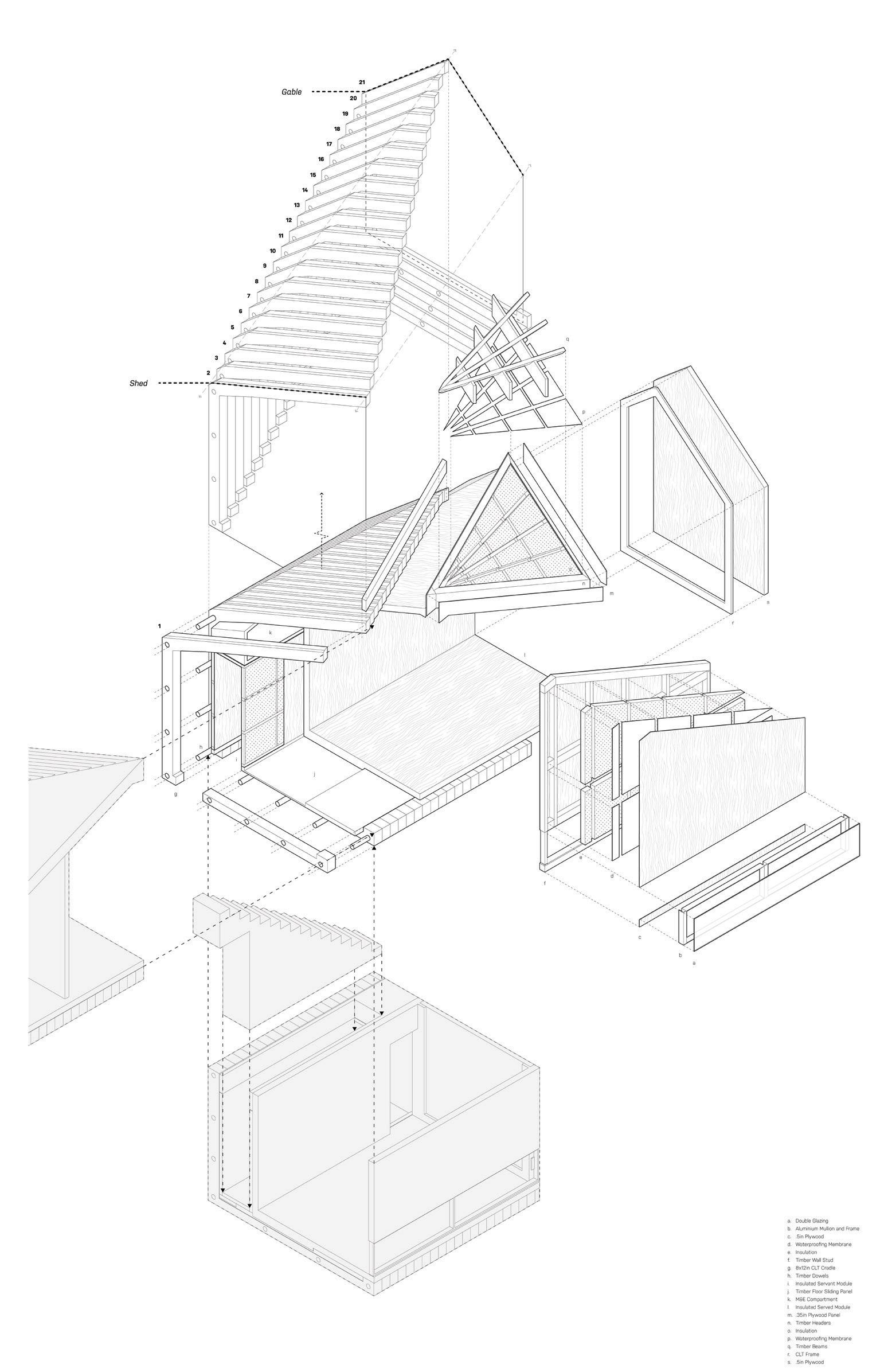

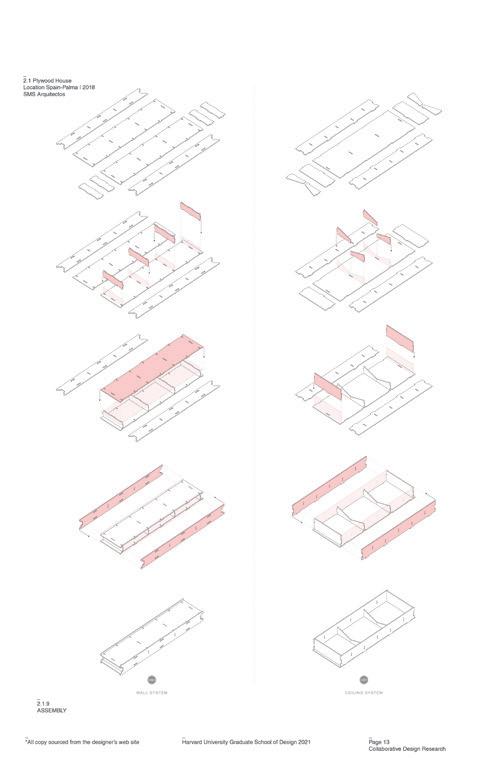

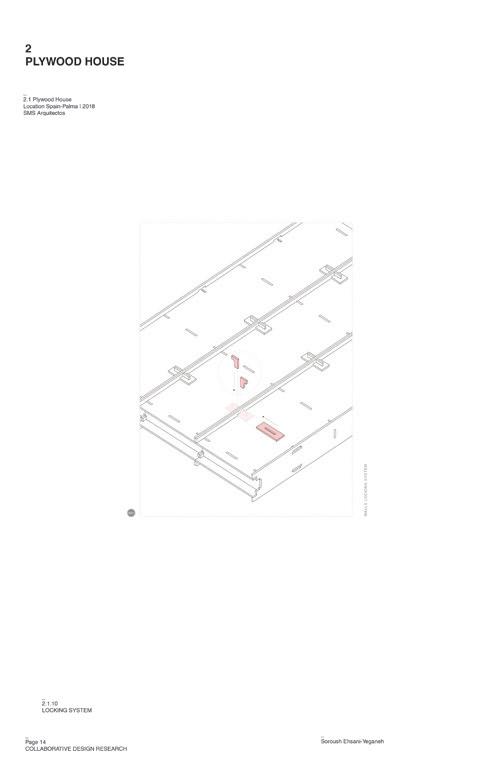

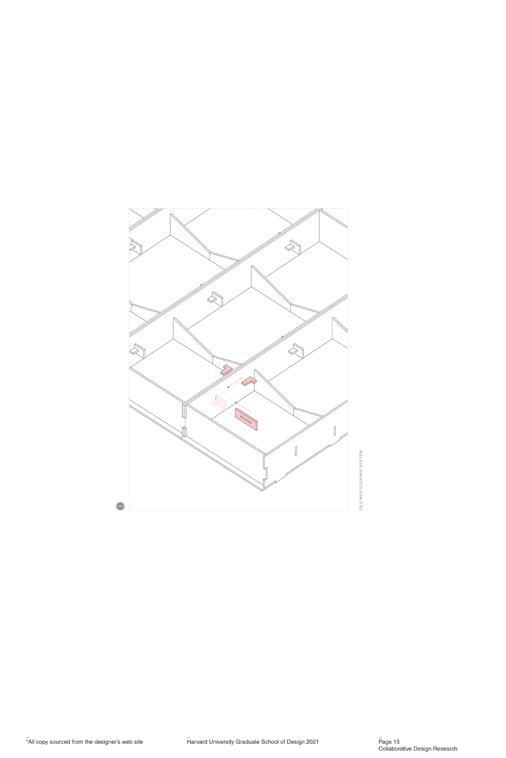

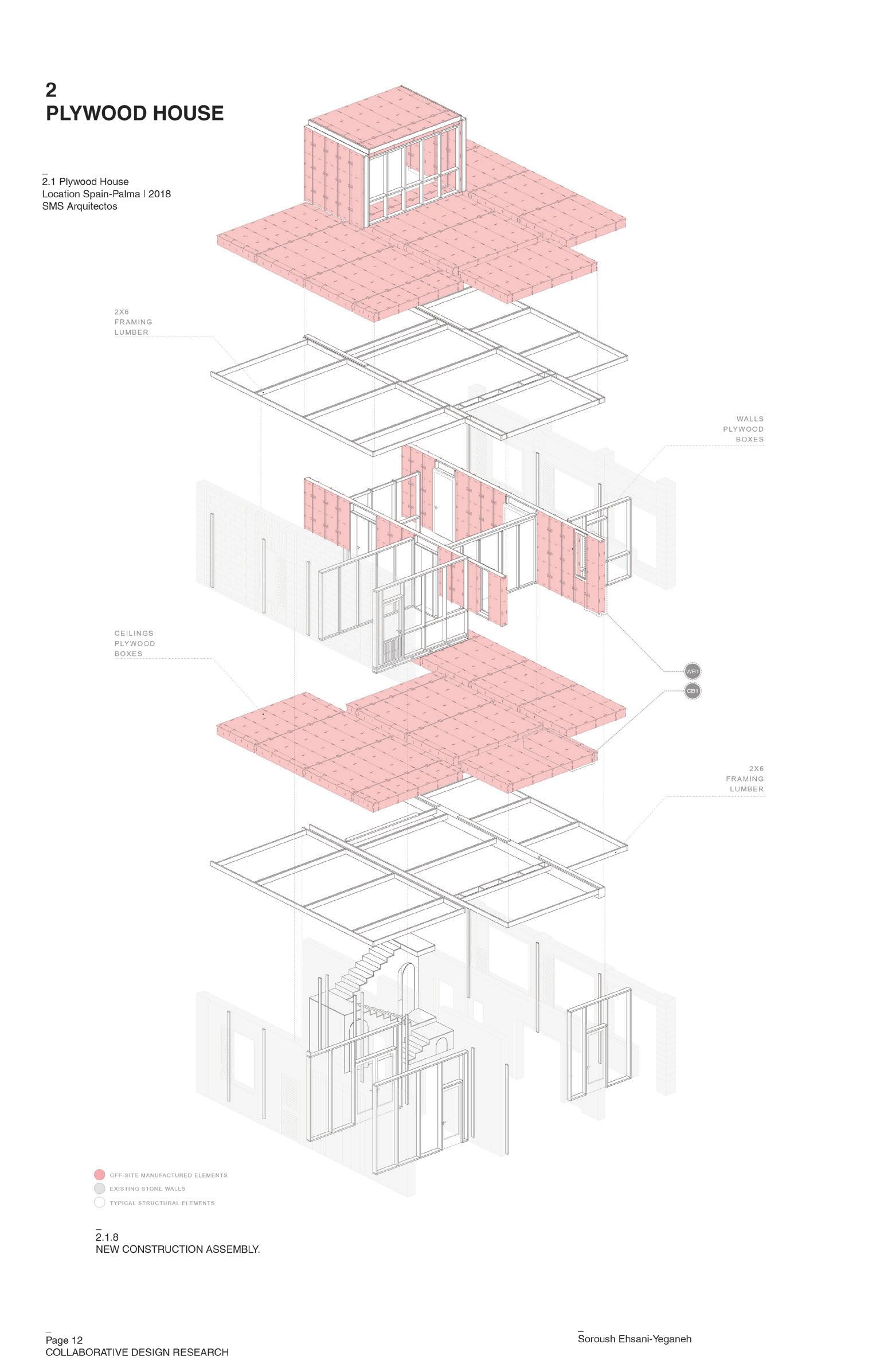

132 Case Study I

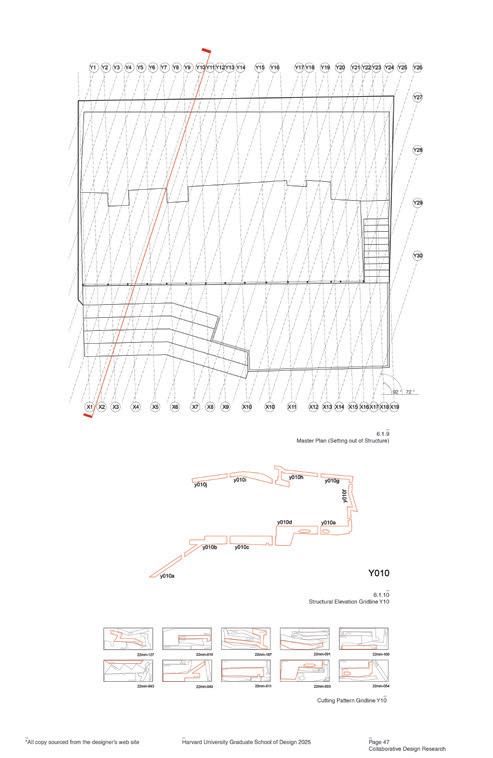

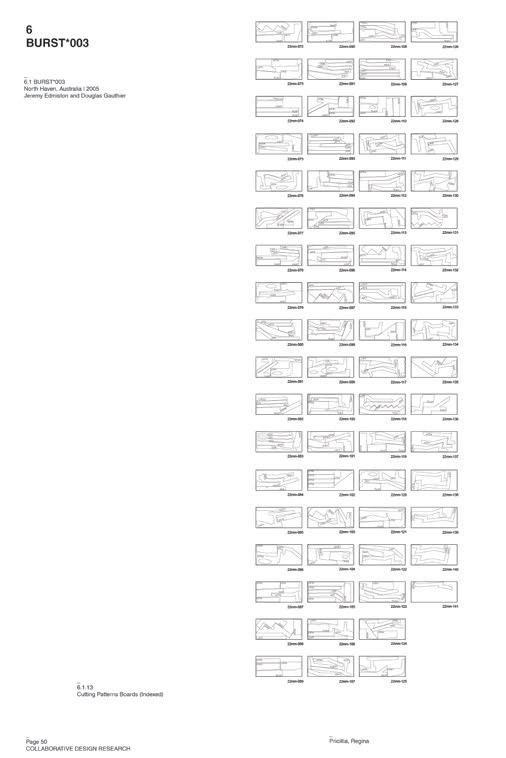

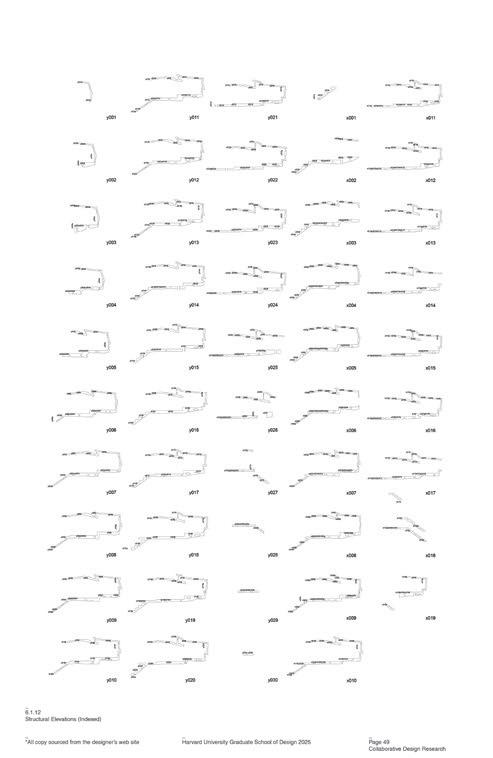

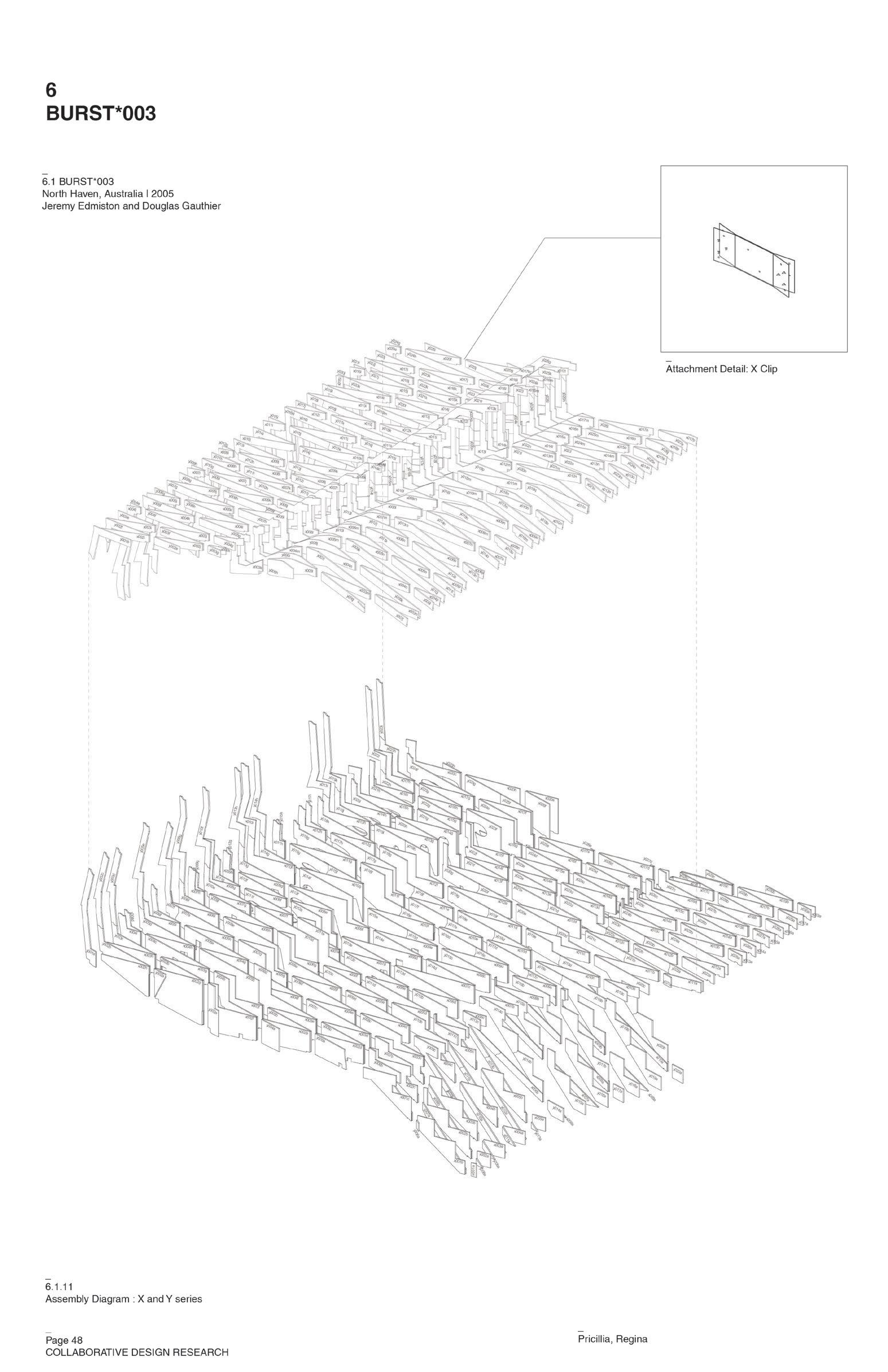

Regina Pricillia

42 SIP Shelf

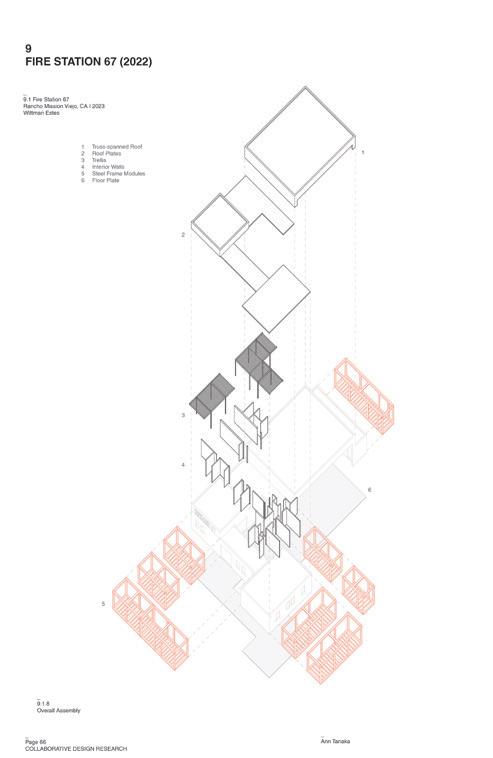

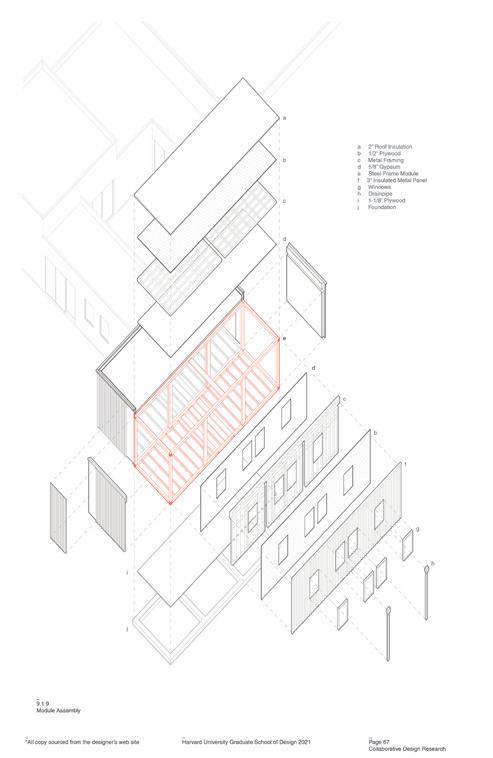

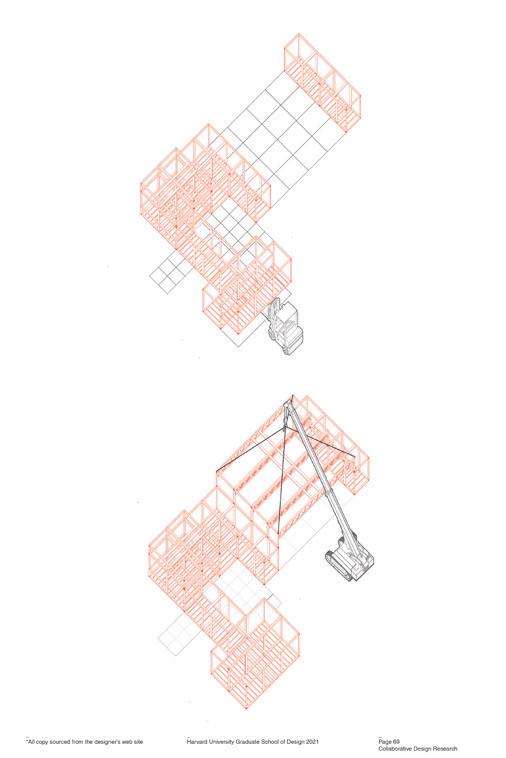

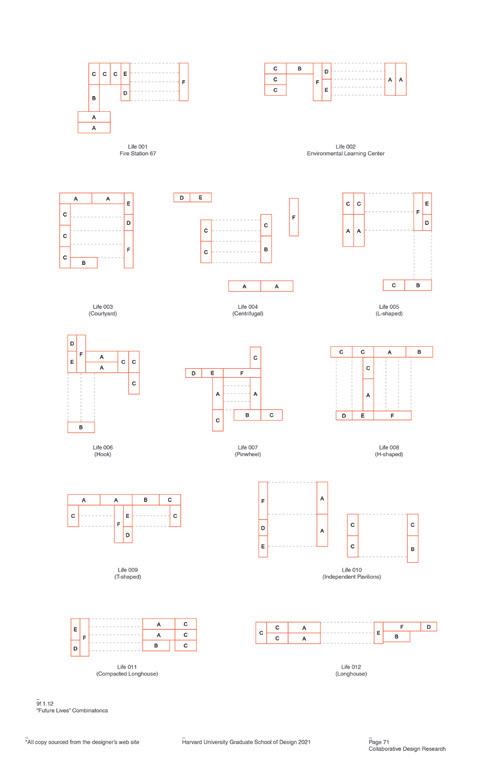

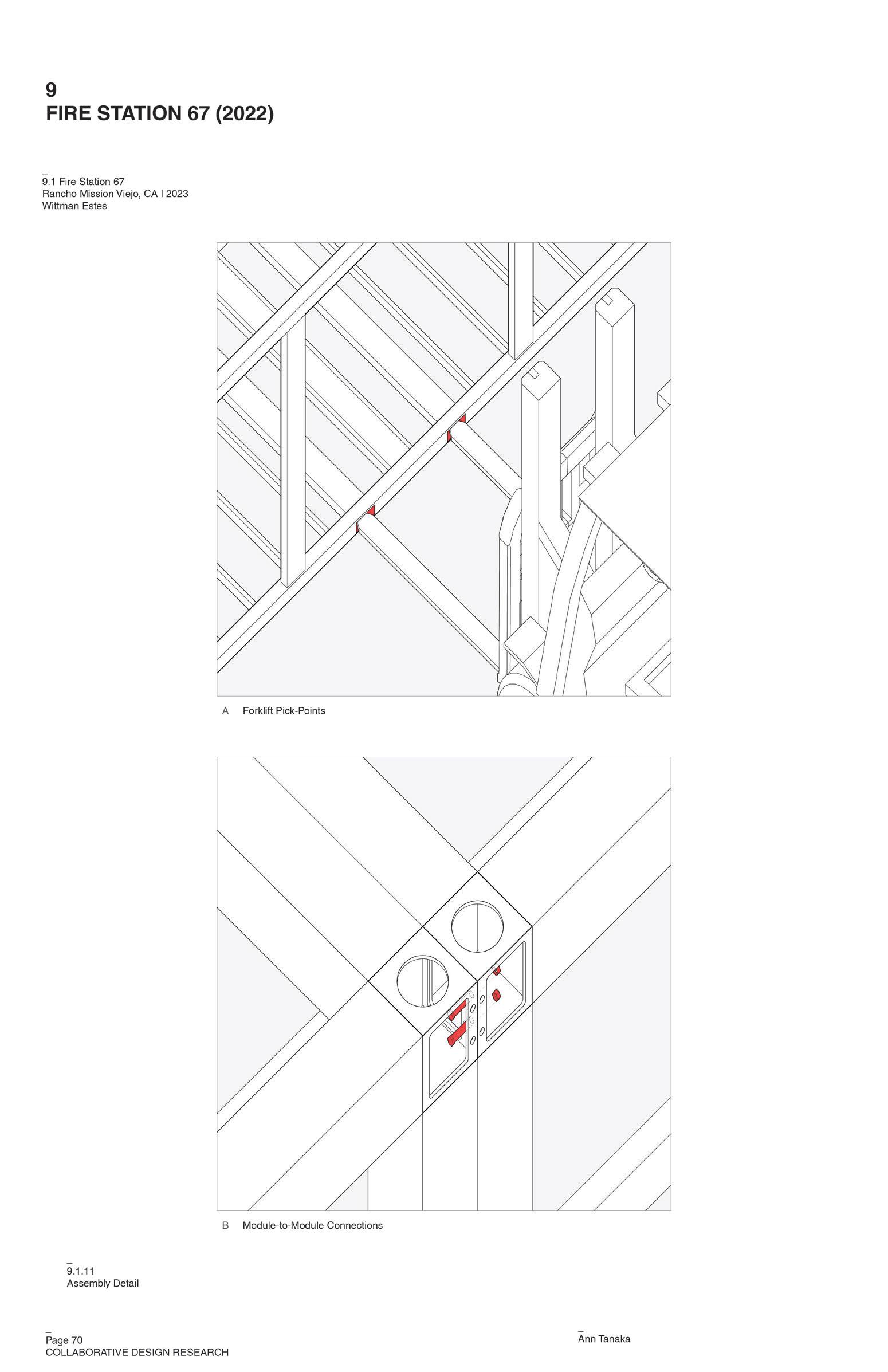

Ann Tanaka

132 Case Study II

Ann Tanaka

132 Case Study III

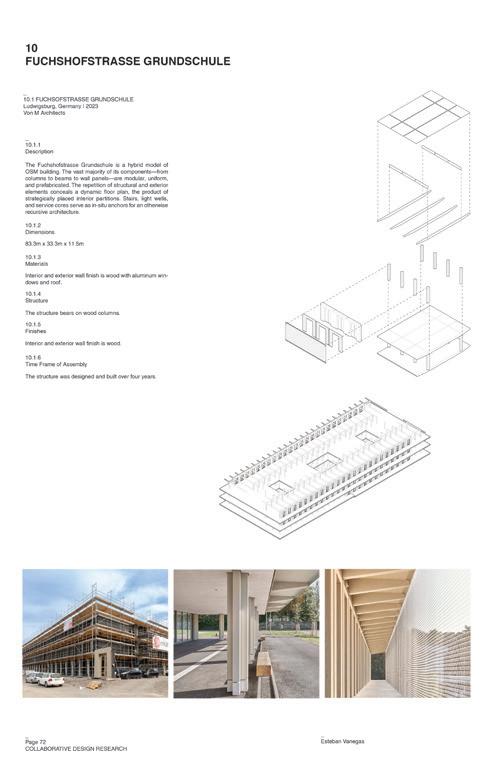

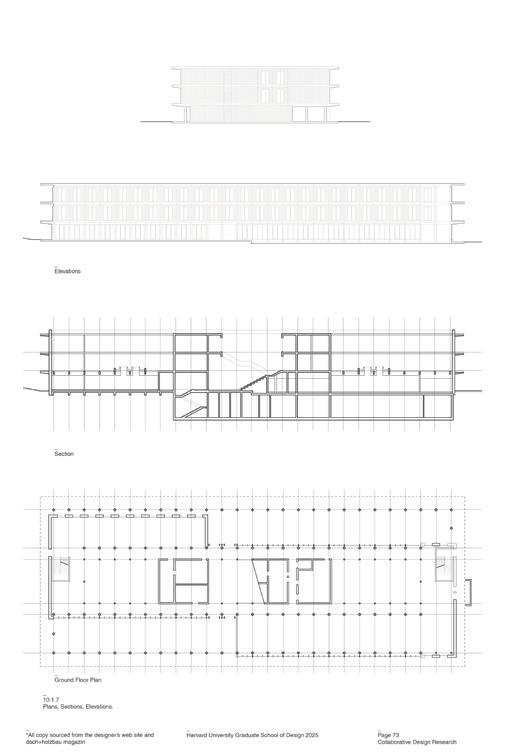

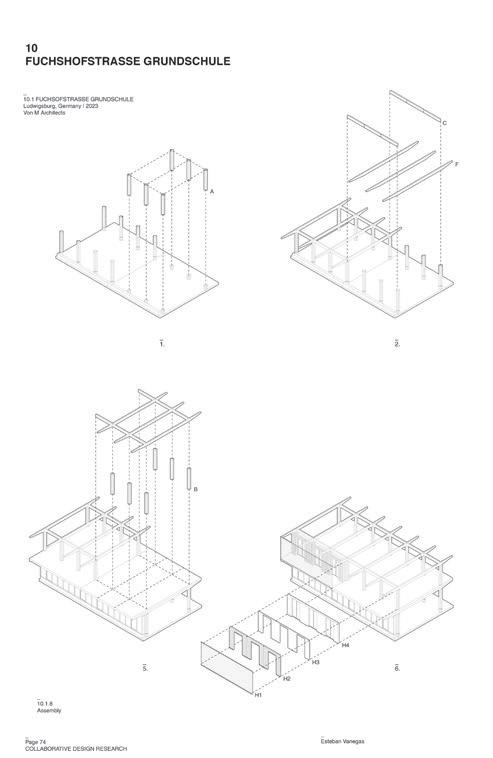

Esteban Vanegas Jr.

42 Gentle Growth: An Expansion Alternative

Esteban Vanegas Jr.

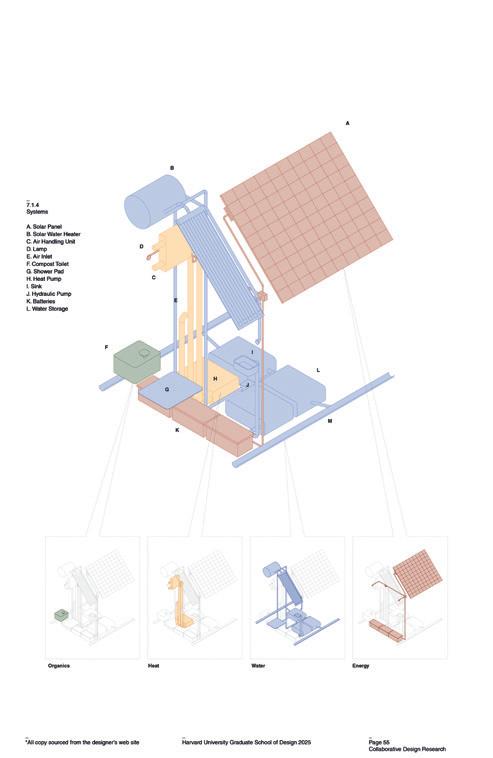

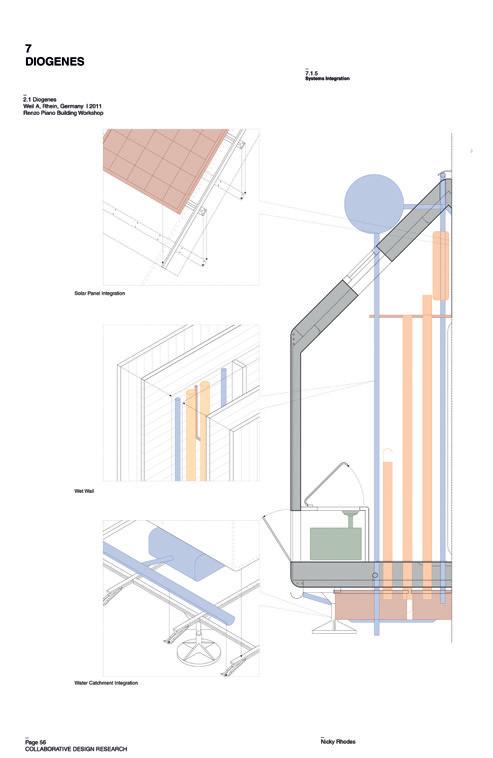

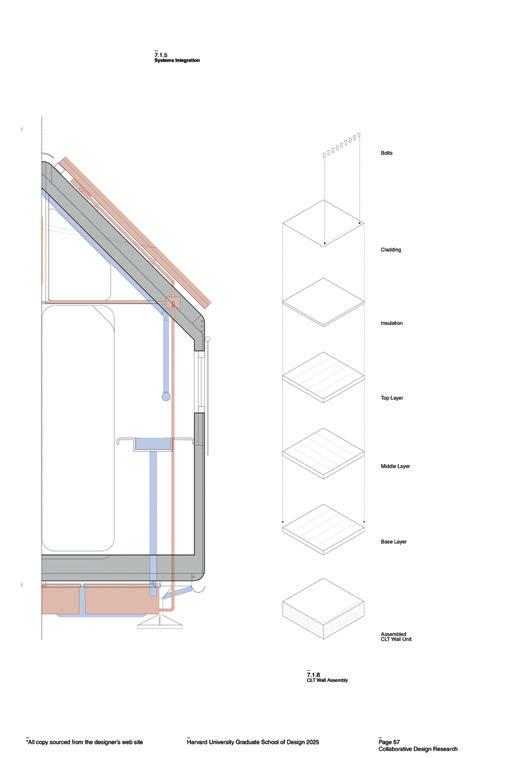

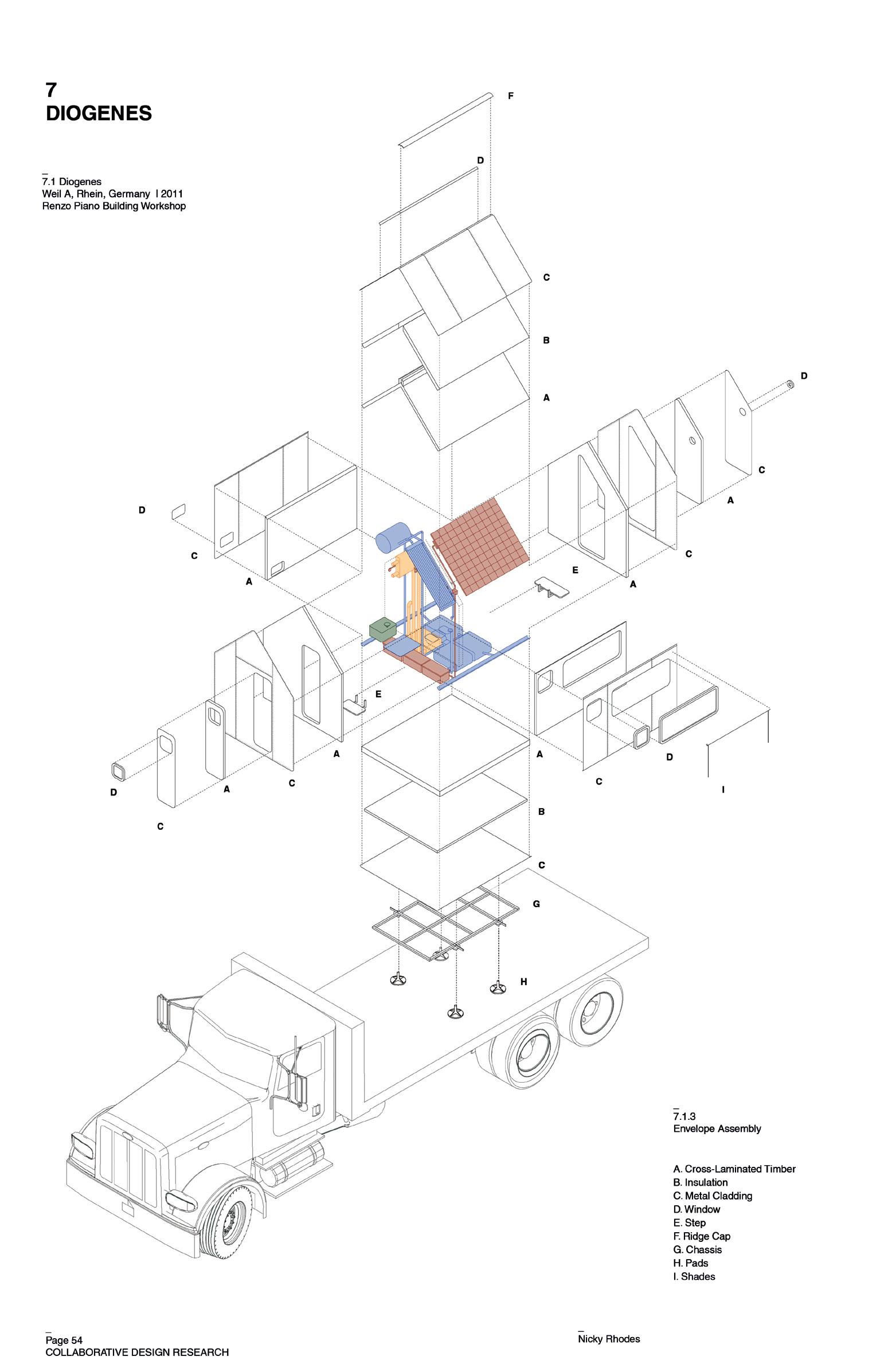

Nicky Rhodes 132 Case Study IV

Nicky Rhodes 118 Seasonal Space

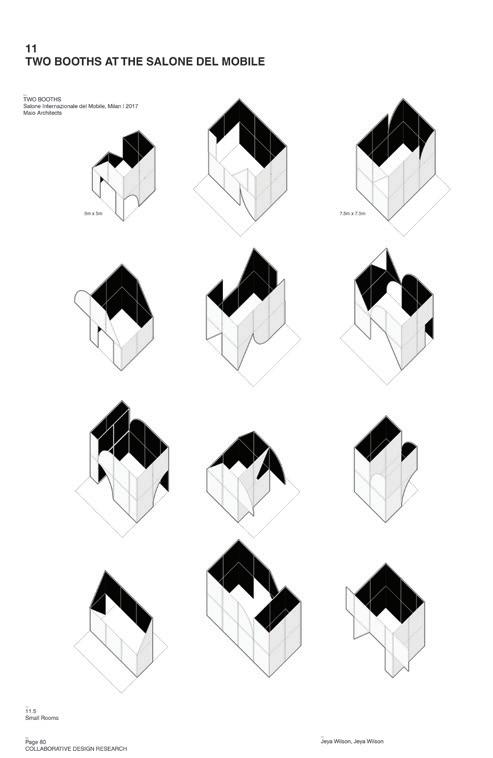

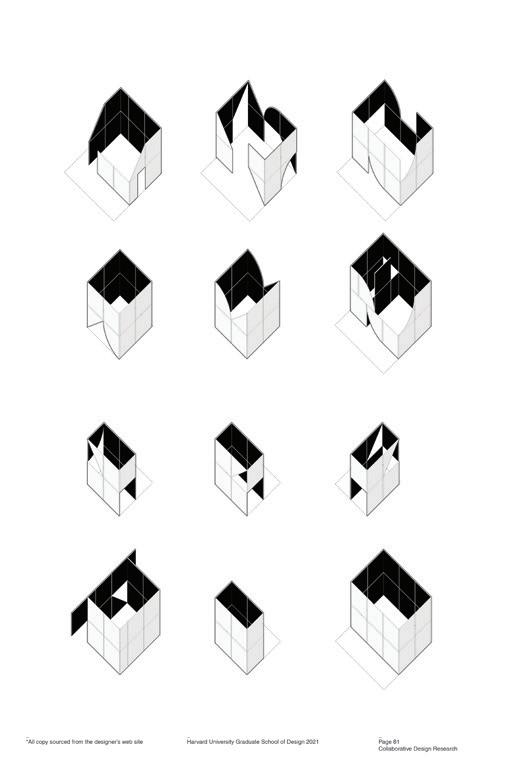

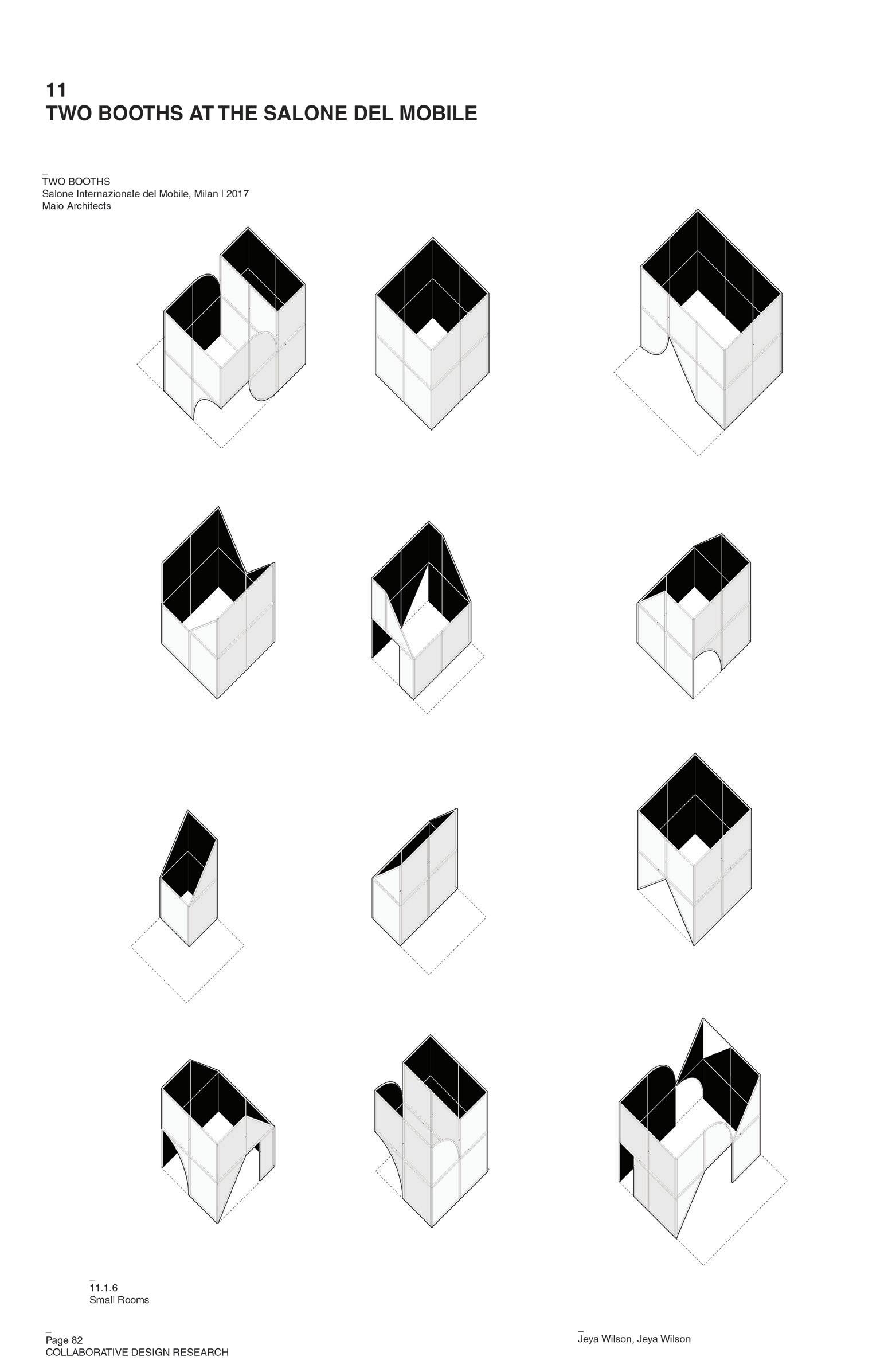

Jeya Wilson

Case Study V

Jeya Wilson

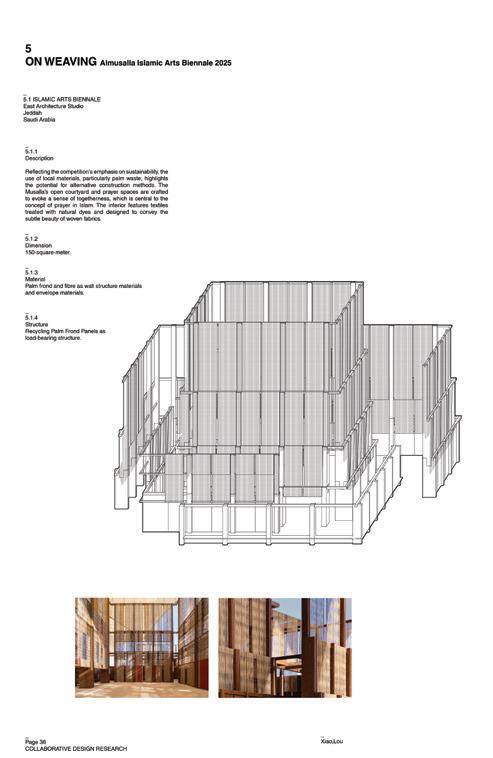

Case Study VI

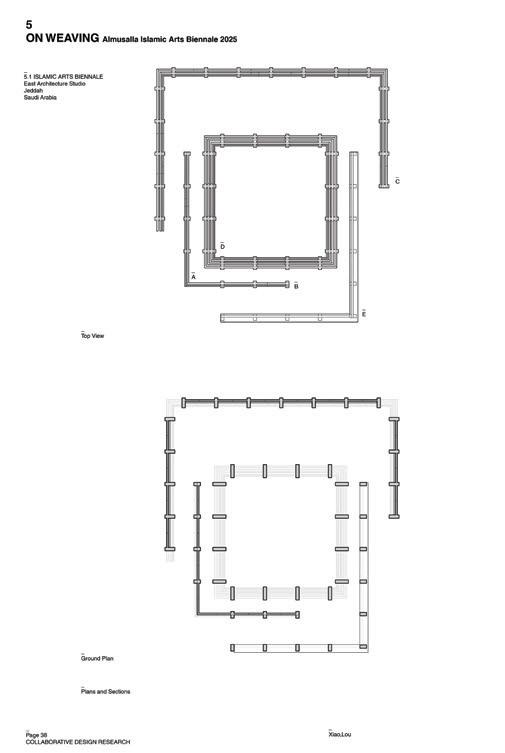

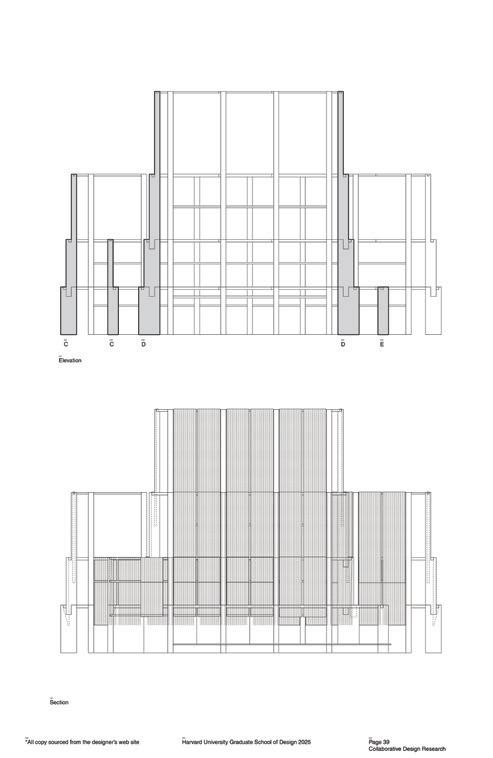

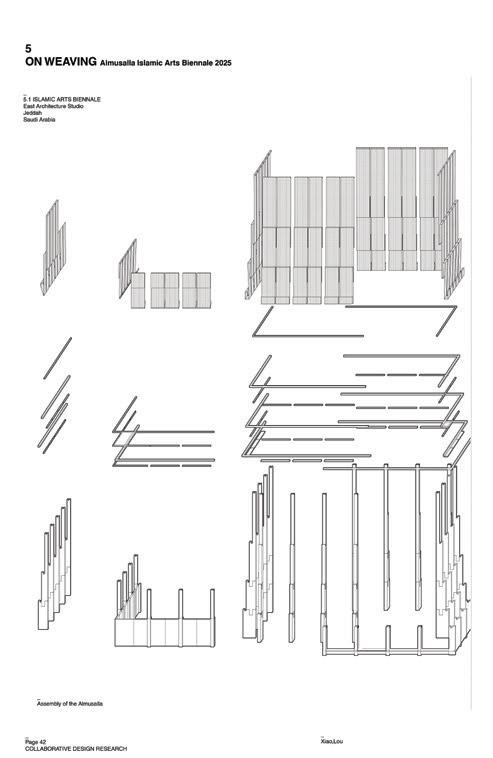

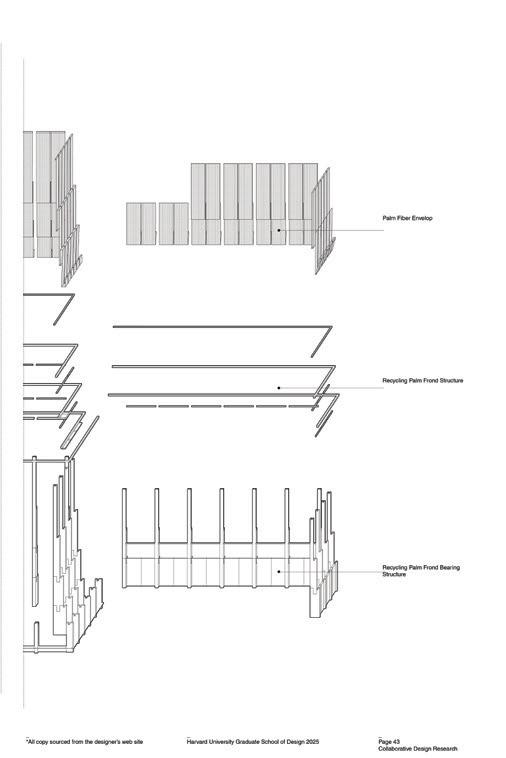

Lou Xiao

Seasoned Frames: OSM-Based Juice & Ice Cream Shop

Lou Xiao

Case Study VII

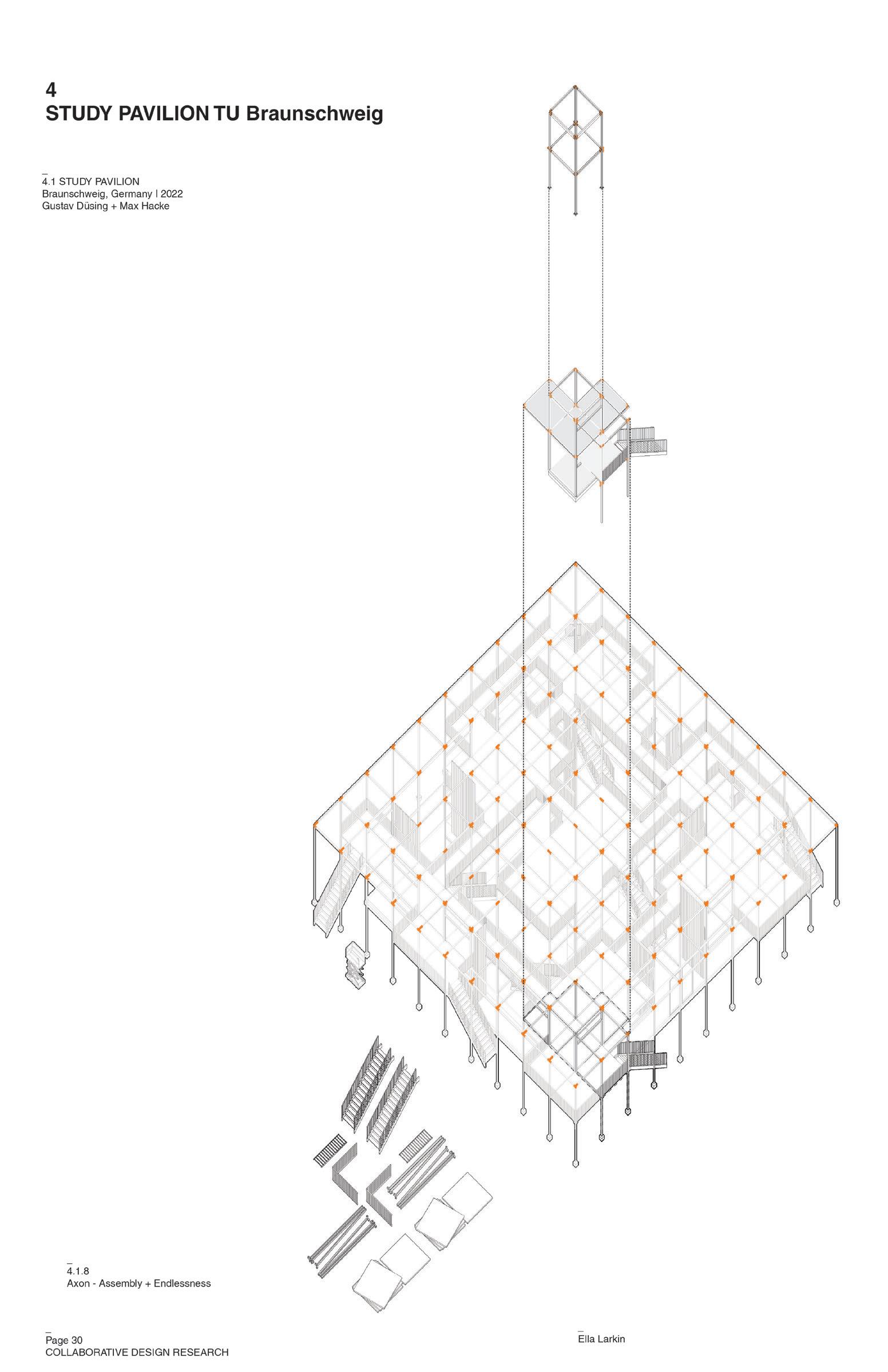

Ella Larkin

Patch-Werk

Ella Larkin

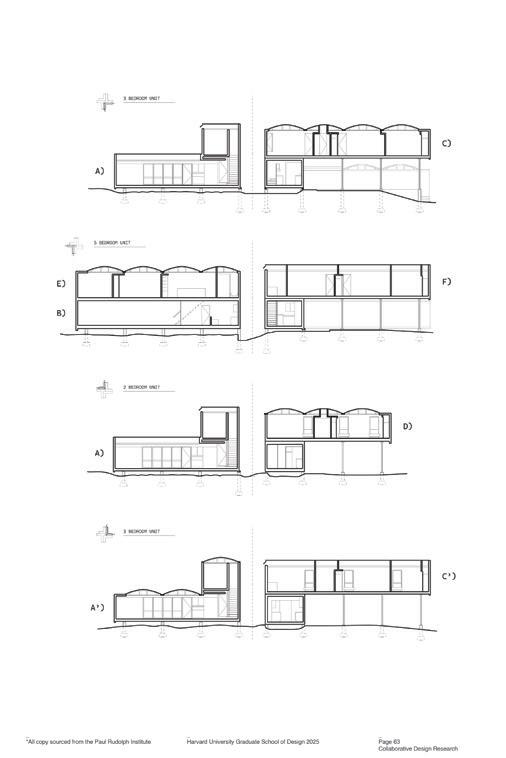

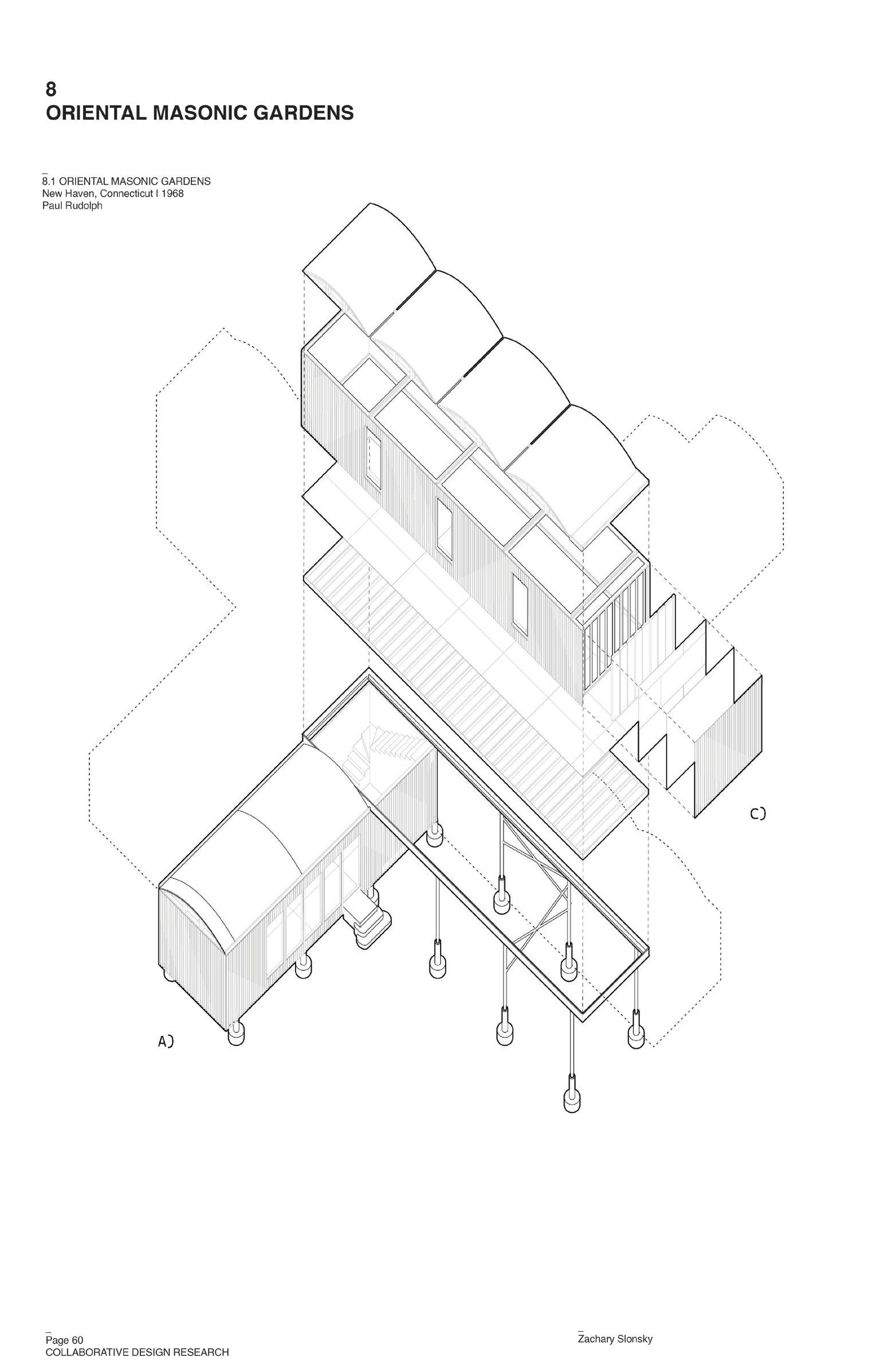

Case Study VIII

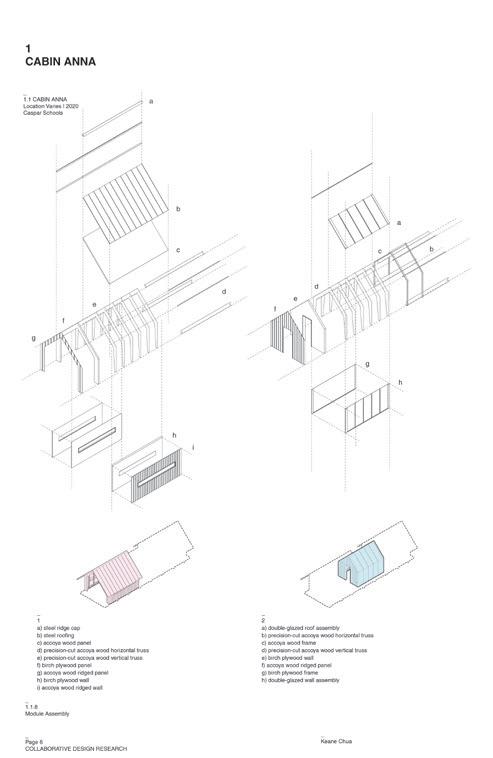

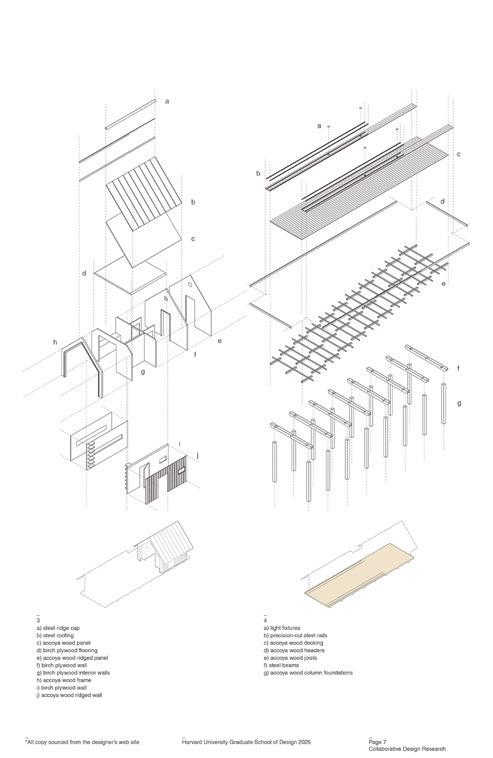

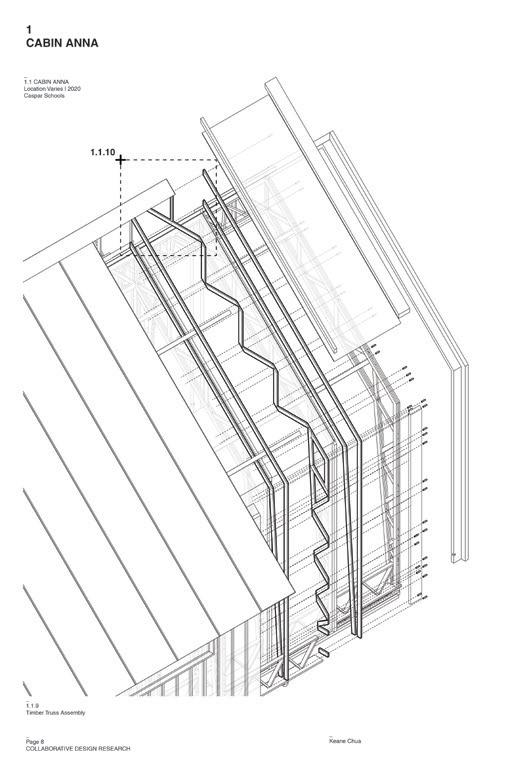

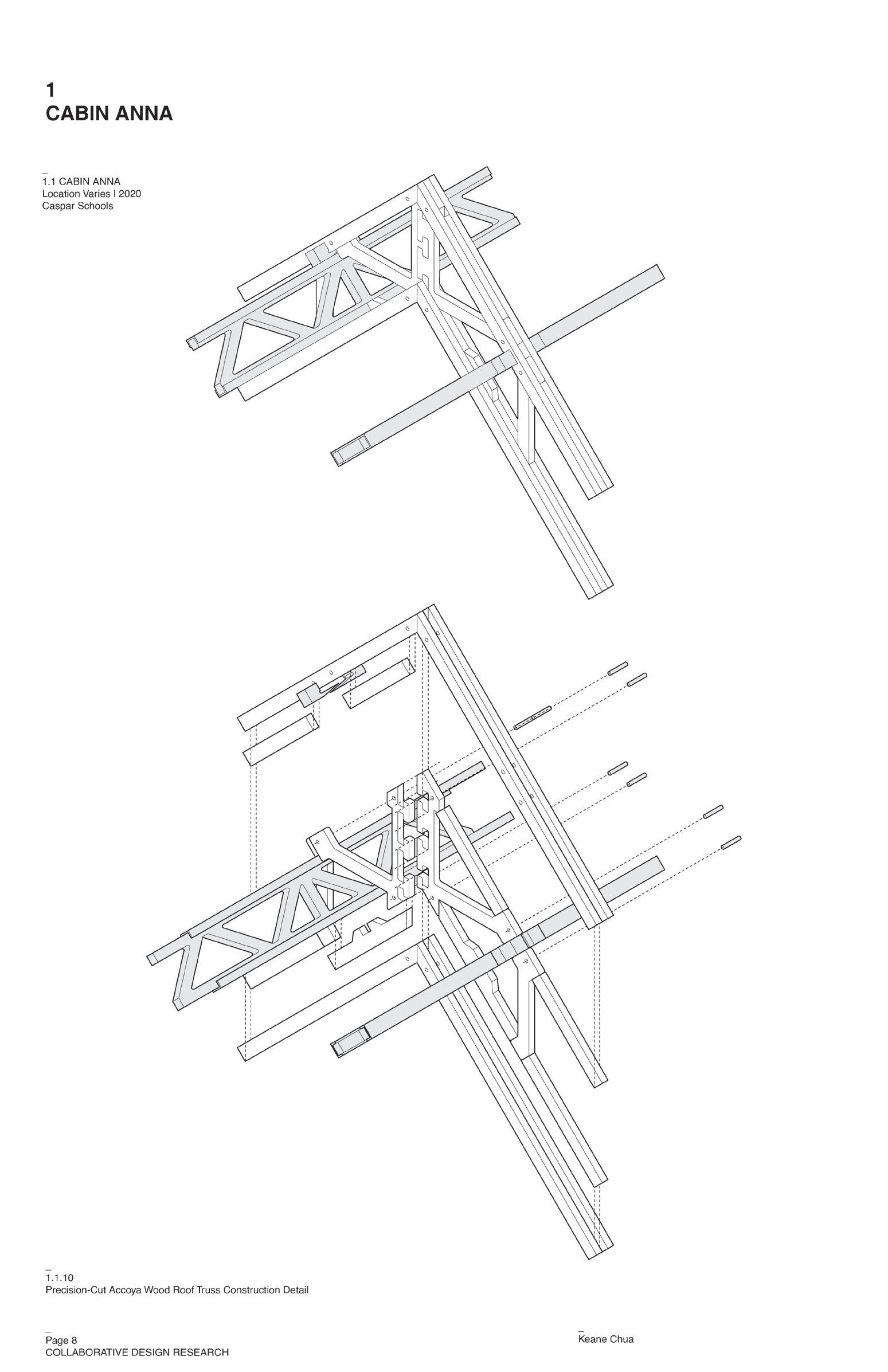

Keane Chua 132 Ceremony

Keane Chua 132 Case Study IX

Elise Hsu 132 Compounds

Elise Hsu 132 Case Study X

Ziyang Xiyong 132 AgriLab Village

Soroush Ehsani-Yeganeh 132 Case Study XI

Soroush Ehsani-Yeganeh 132 Case Study XII

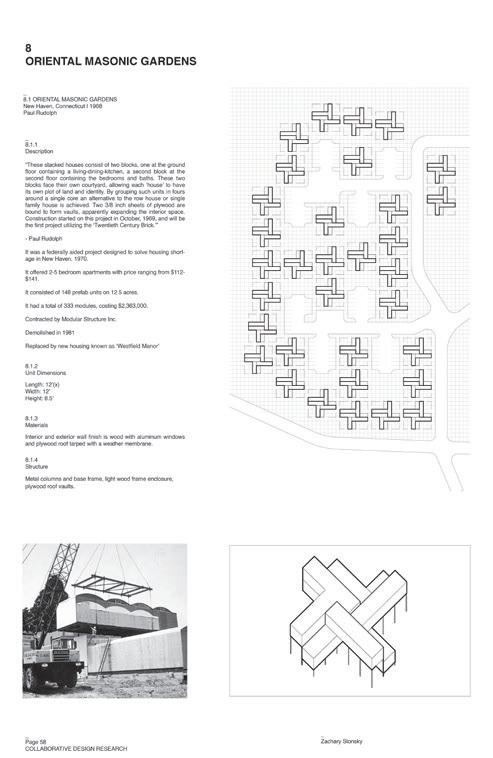

Zachary Slonsky

This studio is the first of a series on to the future of work in our changing societies, made possible by the generous support of the Nambu Family Design Studio Fund. At stake are the broad societal issues of employment, education, and work-life balance, as they relate to architecture, urbanism, and the preservation of the environment.

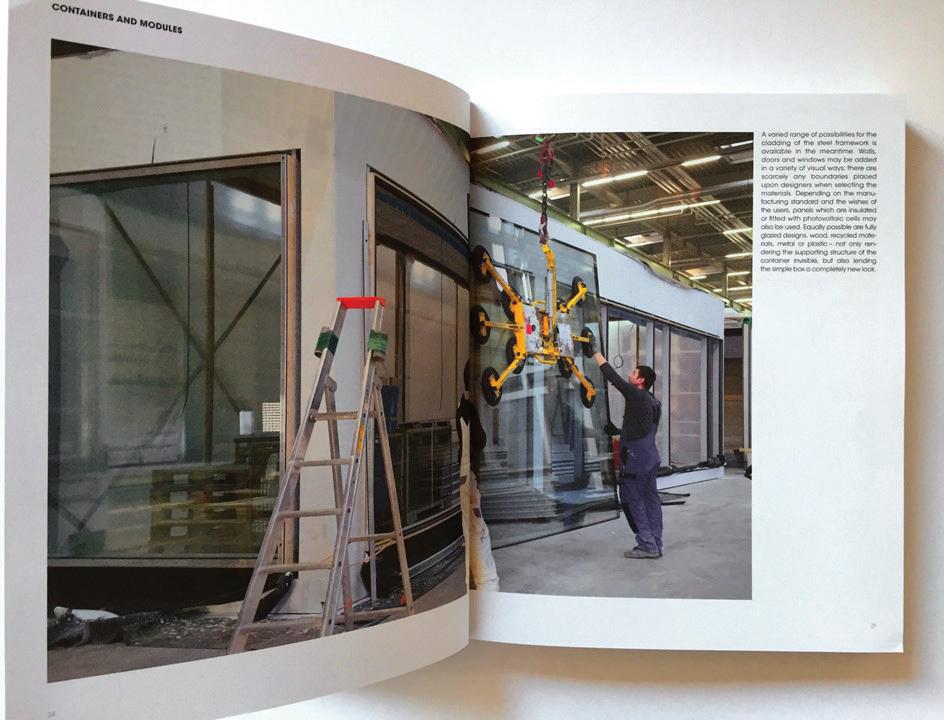

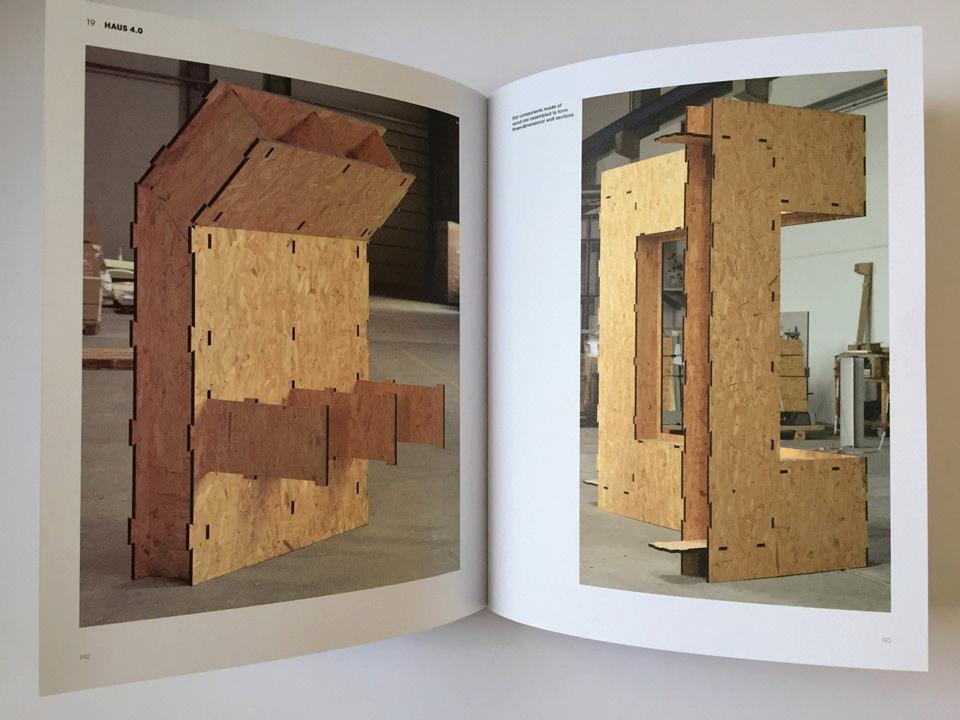

This first season focuses on the spaces of work and extends a multi-year investigation of the re-emergent phenomenon known as Offsite Manufacturing (OSM for short).

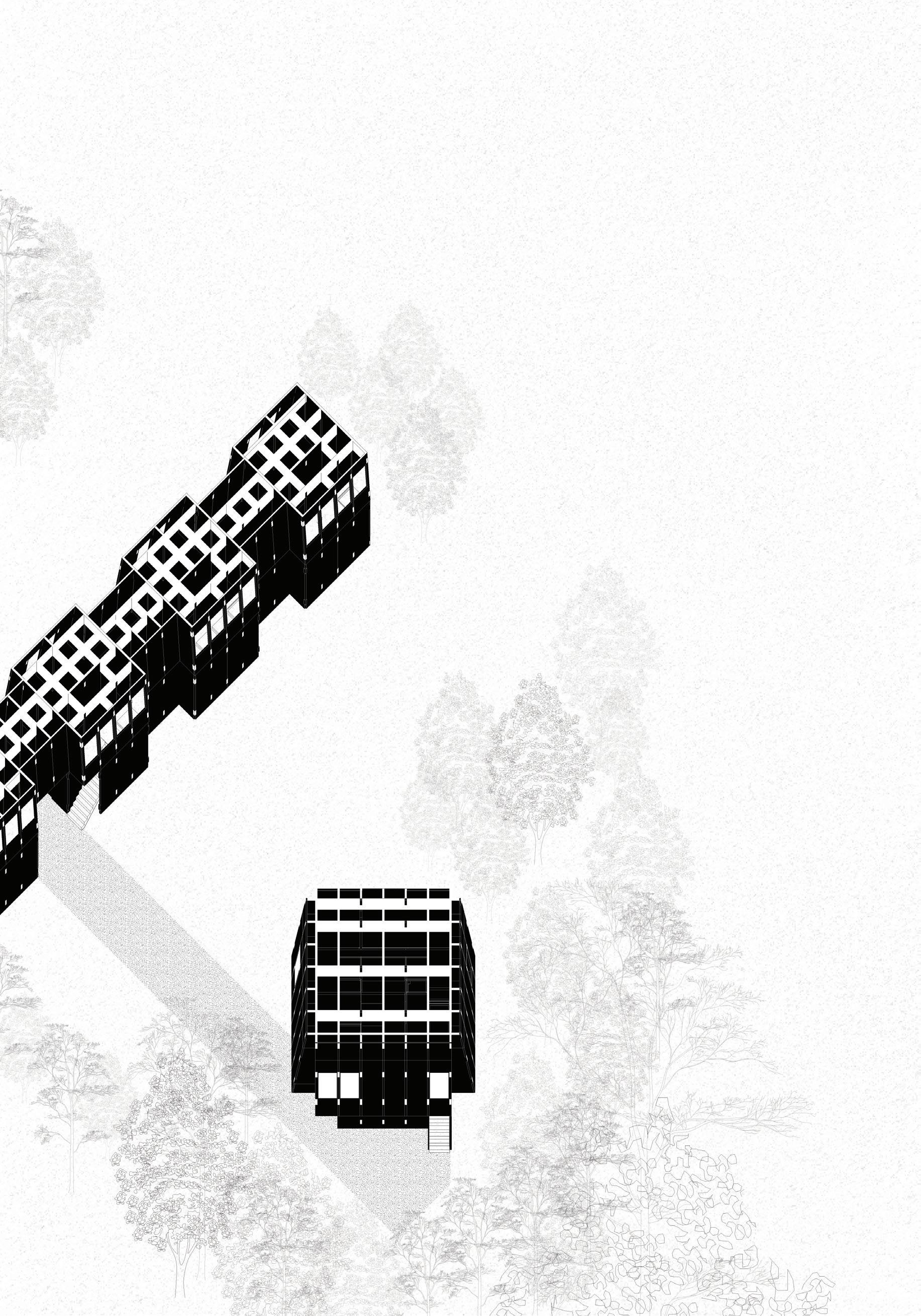

The studio is sited on Awaji, an island the size of Singapore located in Seto Inland Sea in central Japan. With its stunning natural setting and depopulating villages only a short distance from the mega-agglomeration of Kobe/Osaka, the mixed predicament of the island is typical of Japan’s most peri-urban environments.

Thinking about the future of work outside the city means finding ways to economically revitalize the periphery. In the past few years, thanks to the sustained patronage of the Tokyobased corporation Pasona Inc, Awaji has seen investments in affordable housing, primary schooling, small-holding agriculture, and an assortment of hospitality venues catering to same-day visitors, as well as professionals in search of work and a better quality of life.

The introduction of sustainable agricultural practices and training has been a particularly important part of this initiative. Working to a brief of mid-sized communal buildings designed and assembled in factories, the students explored various ways in which architecture and manufacturing could support Awaji’s unique combination of agriculture, social enterprise, hospitality, education, and outreach.

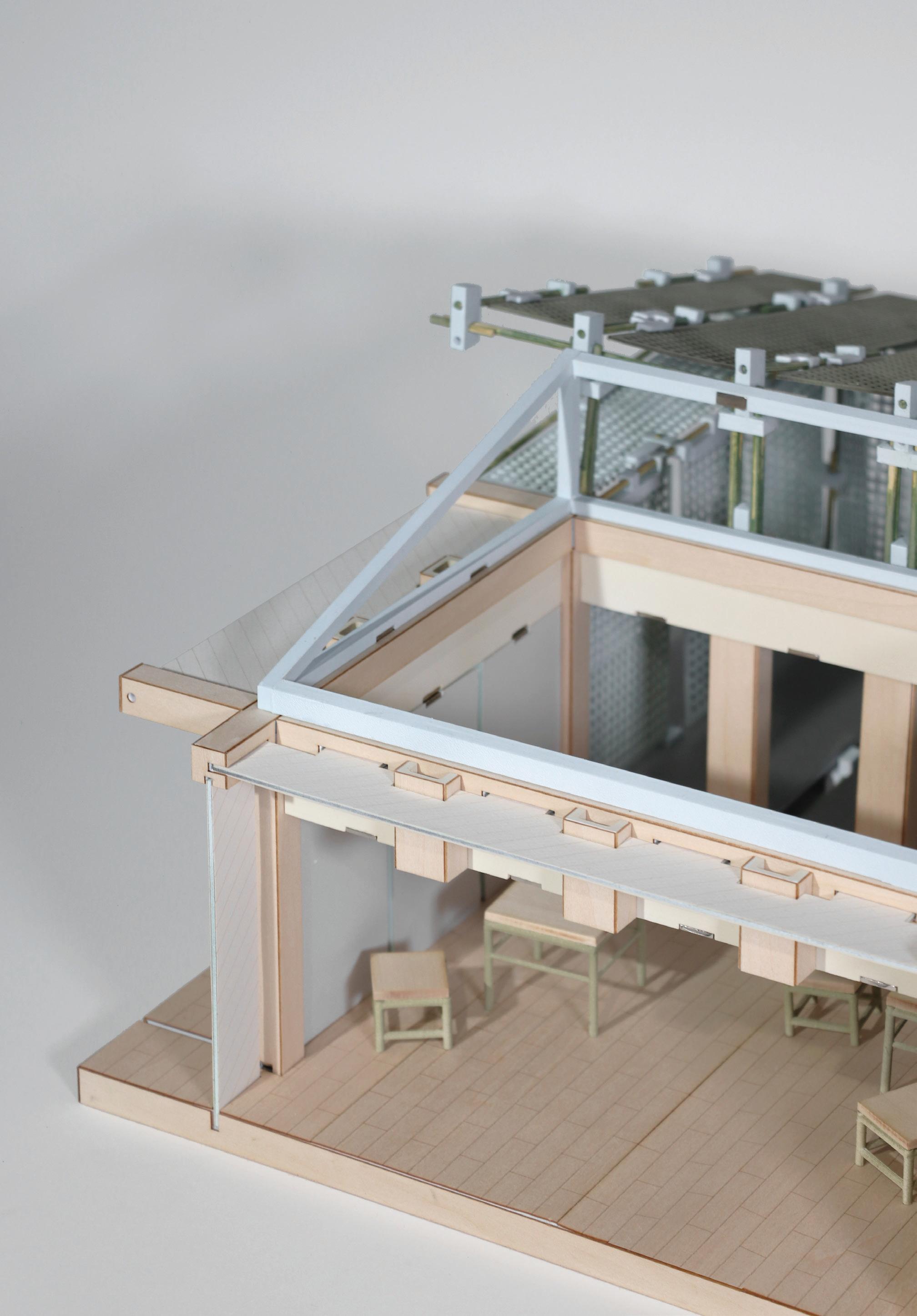

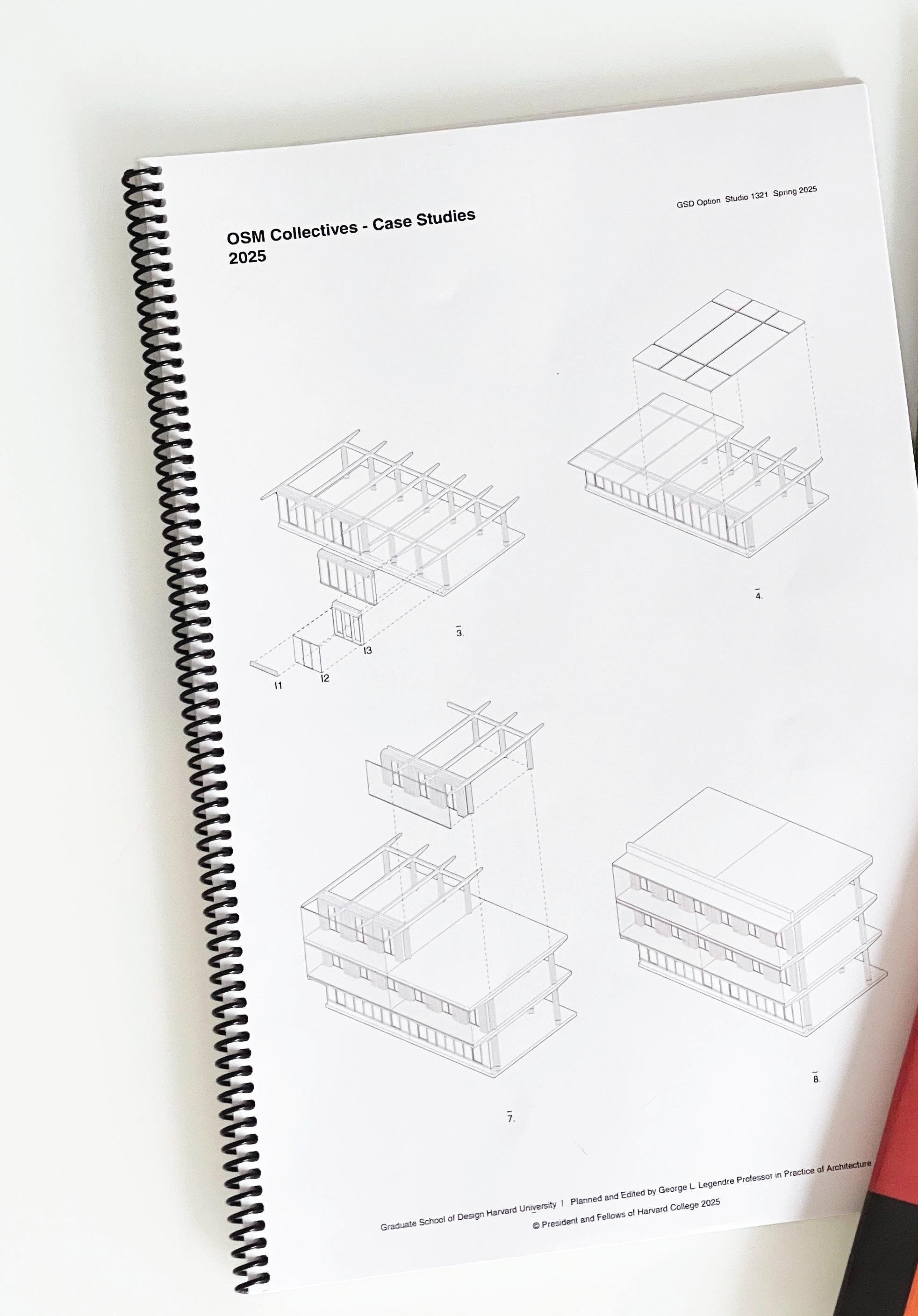

The material included in this report forms part of an ongoing design research initiative launched in 2018 under the somewhat cryptic title of Model as Building – Building as Model1 The four graduate studios taught under this moniker between 2018 and 2024 explored the reemergence in the twenty-first century of offsite manufacturing or OSM, formerly known as prefab, whereby projects of any size or purpose are designed and built anywhere –anywhere that is except on site.

OSM is not a technical problem, and our research has never been about construction. Our primary interest lies in the nature of building, and the ways in which the work of unsuspecting actors of the design and manufacturing world enrich our understanding of architecture and urbanity as disciplines.

While our past studios explored historical European and North American precedents, prioritized the demands of OSM-driven design and concentrated on small-scale residential models, this studio benefitted from the exceptional institutional support of the Tokyobased Nambu Family Fund to expand its research into the world of tomorrow’s spaces of work. In a fascinating, if somewhat unusual, twist we were invited to reflect on the broad questions

of work and well-being away from the cities, these centres of mass employment, focussing instead on the rural heartlands and economically depressed coastal communities of Hyogo prefecture in central Japan.

In late September 2024 we arrived on Awaji, an island the size of Singapore, a short distance from the mega-city of Kobe and Osaka in the Seto Inland Sea. With its stunning natural setting, depopulating towns, and semiabandoned fishing and farming villages, the predicament of the island is typical of Japan’s peri-urban environments. Thinking about the future of work in such places means finding ways to economically revitalize them, a slow process at best. In practice however, the progress made over the past decade on Awaji shows how the economic decline beyond large metropolitan conurbations can be decisively reversed. This is the context the studies and design proposals published in this report seek to address.

This semester reprises a multi-year investigation of the re-emergent phenomenon known as Offsite Manufacturing (OSM). OSM is not a new idea –the Bauhaus proposed it in the 1920s as a socially progressive model for mass housing.

Today, however, while need remains an important factor behind OSM, need is no longer the dominant one. Desire in its contemporary forms (consumerism, digital technology, social media culture) is equally important.

This new world offers opportunities for designers, too. The real draw lies in recognizing that OSM is about process –and a conceptual process at that. First and foremost, there is the primal pleasure of working in this way, which doesn’t go away with age or experience. Simple constraints inform the designer’s thinking: protocols of assembly and tooling, the width of a single room, and of course, the width of the freeway on which the house is trucked, like a gigantic model from the land of Gulliver. UK architect Andrew Waugh once said, quite rightly, that the width of the motorways will determine the form of future cities, in the same way that a fixed plot width determined the form of Victorian London2

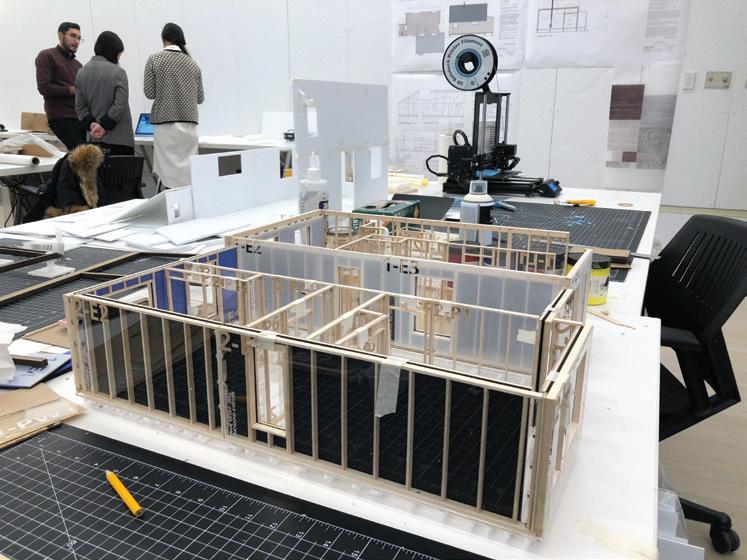

Finally, with its scale shifts, patterns, and strangely direct translation from making to building, OSM may have more in common with the speculative efforts of design students working away on the trays of the GSD, than it has with traditional building.

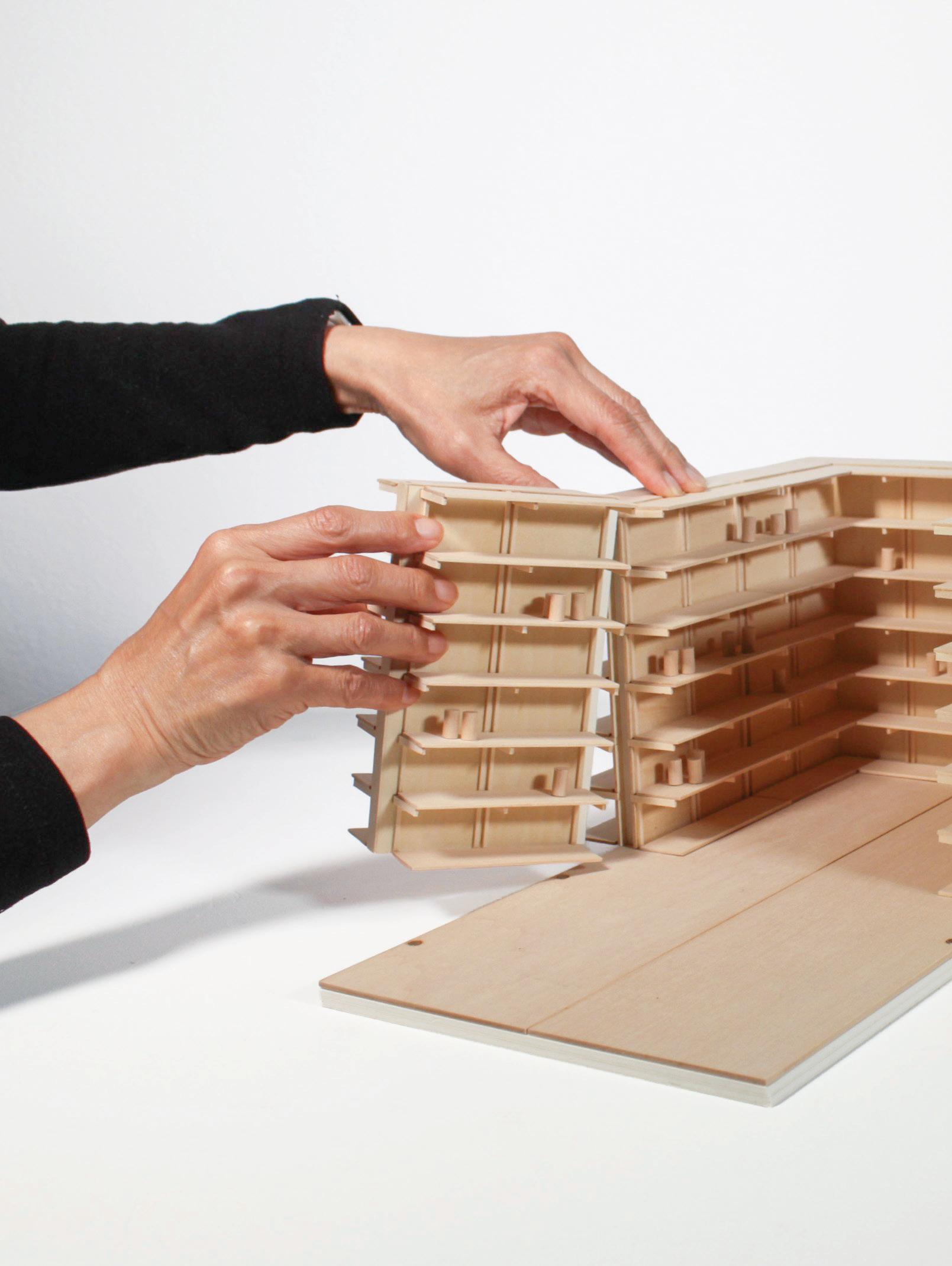

Sometimes it seems that OSM isn’t even about making buildings, but models at scale 1:1 (or maybe the other way around). Model as Building – Building as Model: we have long been intrigued by this uncanny comparison, which frames the multiple case studies compiled during the first four weeks of the term, and the design proposals developed thereafter.

Thinking about the future of work outside the city means finding ways to economically revitalize its periphery. In the past few years, thanks to the sustained patronage of the Tokyobased corporation Pasona Inc, Awaji has seen investments in affordable housing, primary schooling, small-holding agriculture, and an assortment of hospitality venues catering to same-day visitors, as well as professionals in search of work and a better quality of life.

The Introduction of sustainable agricultural practices and training has been a particularly important part of this initiative. Hence, working to a brief of mid-sized communal buildings designed and assembled in factories, the students explored various ways in which architecture and manufacturing could support Awaji’s unique combination of agriculture, social enterprise, hospitality, education, and outreach.

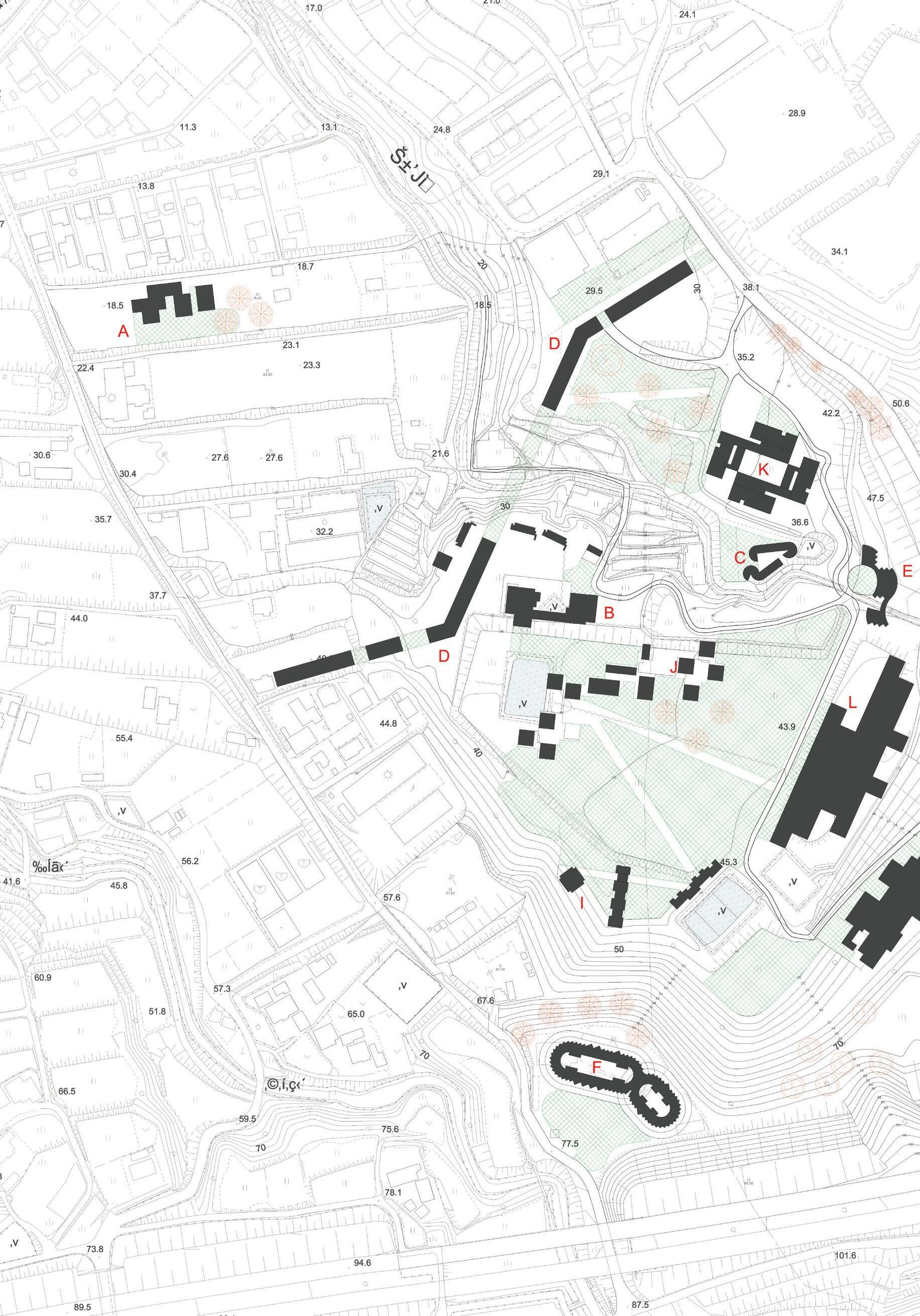

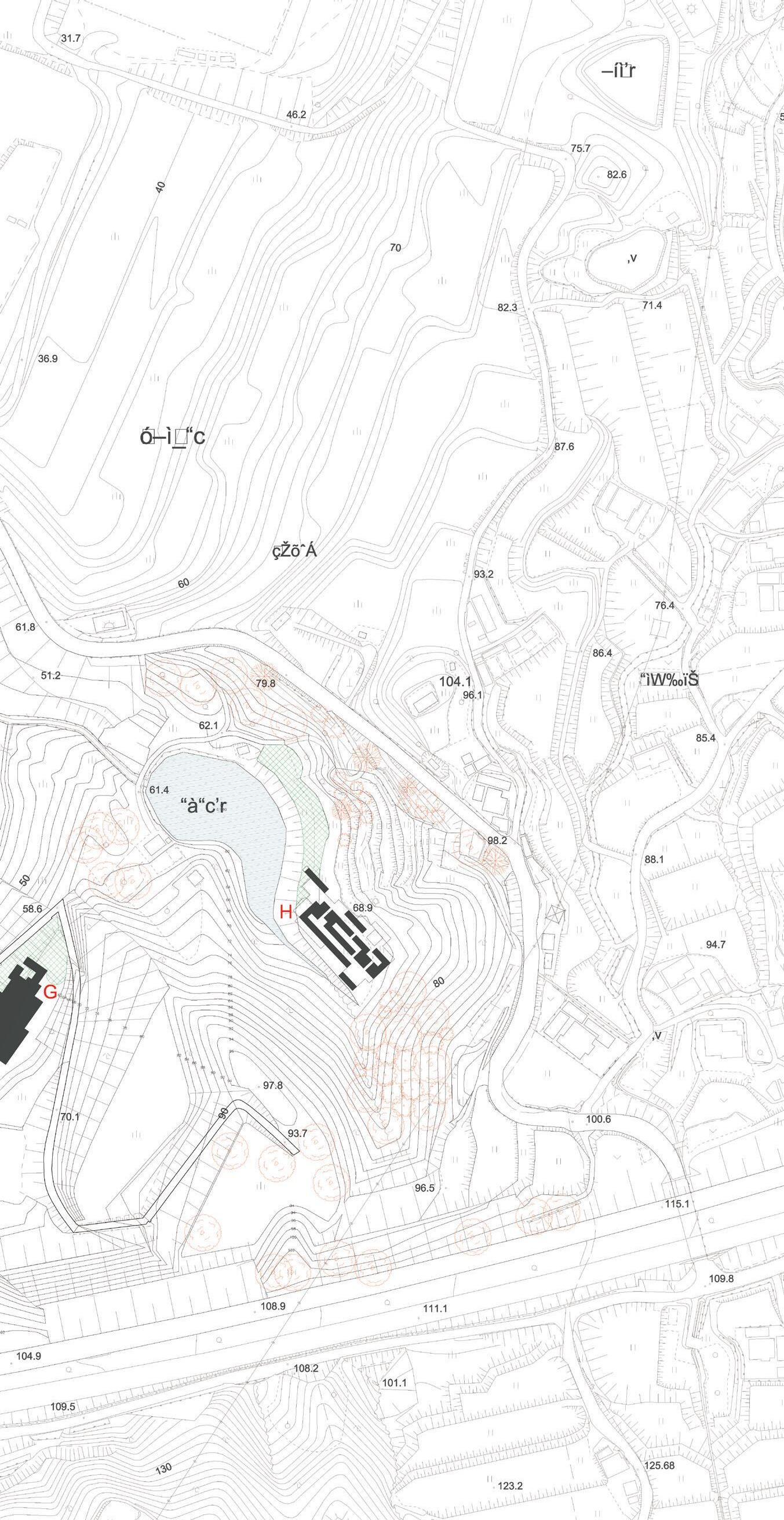

The proposals are located on a hillside above the fishing village of Asano, on the west coast of the island. Once a thriving coastal community of fishers and farmers, Asano has been steadily depopulating since the 1980s. Further up the hill, our site was originally formed by traditional Japanese mountain farming practices. The geometric terraces of its former rice fields cascade down the steep mountainside, taking nature and its accidents in their stride.

The site brims with geological crevices, lenticularly-shaped water basins, as well as talwegs running along the valley, and channelling the mountain springs down to the grey sea3

Alongside geography and program, the cultural context of Japan constitutes an important –albeit elusive–part of this semester’s agenda. There has been a dialogue between what one might call the eastern and western parts of our brief. Japan’s extensive use of timber and ancient craft of joinery, for instance, mirror the central role played by structural wood in the re-emergence of Off-Site Manufacturing.

There is therefore an important conceptual affinity between the central tenet of OSM and the cultural role of timber in Japanese history, and most of the proposals in this report have paid attention to it.

Beyond that, the brief seeks to engage with the idiosyncrasies of Japanese culture as we perceive it, such as the ubiquitous blend of contemporary and traditional. While many countries in southern Europe feature equally striking combinations of vernacular and modern, the feeling in Japan is significantly different.

When visiting say, Milan or Paris, the stark boundary between past and present never goes away. In Osaka, on the other hand, a visitor shall pause before a single-storey timber house and stare at the dark metal grill work on the gate, while missing entirely the 18-storey glass tower standing across the street. These parallel realities do not feel mutually exclusive.

We then have the distinctly Japanese way of putting together perfect buildings with little regard for the customary western distinctions between large or small, permanent or provisional, crafty or makeshift, ‘important’ or ‘menial’.

Staring at a hundred concrete beams neatly stacked behind a cordon like screws and washers boxed away on a shelf, a foreign visitor welcomed into a busy construction site in Japan would be forgiven to think she is entering a quiet, family-owned hardware store. The contrast is not so much down to tidiness and organisation (important as they may be), as to an apparent lack of hierarchy in our surroundings. In Japan, everything around us often feels equally important4

Finally, we must reckon with our own longstanding obsession with Japanese aesthetics, and the incessant movement across the imaginary border between Europe, the US and Japan over the past 150 years.

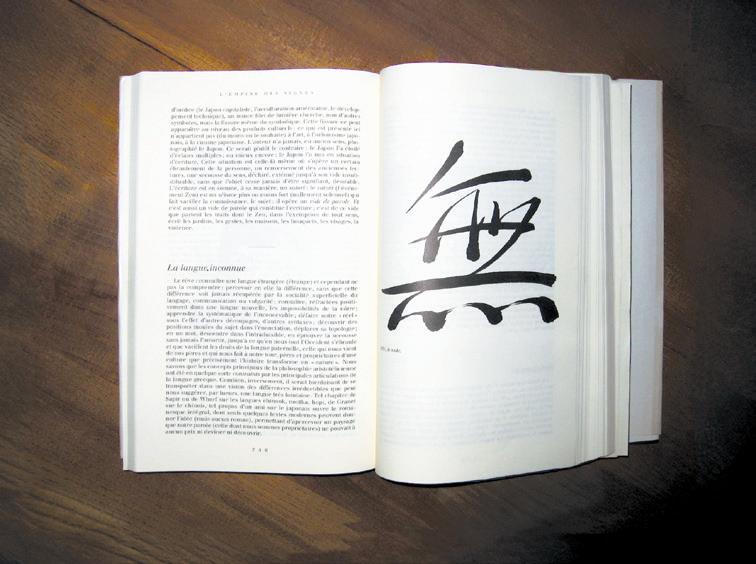

From the proto-Modernist appetite for Japonaiserie amongst European printmakers in the 1860s to the linguistic flights of fancy of Roland Barthes’ Empire of Signs, or Manfredo Tafuri’s Modern Architecture in Japan in the 1960s5, the list of exchanges, borrowings, thefts, understandings, and misunderstandings is long and productive. Language is of particular interest to anyone who studies this list. Japan’s ideogrammatic script merges symbols and images in ways fundamentally alien to the western mind, which sometimes leads to perplexing commentary on all things Japanese.

Roland Barthes’ view of the country, for instance, is that ‘the proliferation of functional suffixes and the complexity of enclitics suppose that the subject advances into utterance through certain precautions, repetitions, delays, and insistences whose final volume turn the subject, precisely, into a great envelope empty of speech, and not that dense kernel which is supposed to direct our sentences from outside and from above’ 6

With the part-time philosopher-guide Roland Barthes leading the pack, it is a miracle that this modern day visitor managed to locate Tokyo’s Shibuya tube station at all.

In any case, the projects and case studies published in this report seem to have absorbed by osmosis, and to varying extents, this powerful cultural context. Note the emphasis on craft and assembly, the attention to detail, the understated, minimal or maximal elegance, and the odd direct homages to traditional Japanese icons like the Katsura floor layouts, or the delicate framing of the Koraku-en gardens. These pervasive references testify to the immense power of context as we experienced it on site, as well as from afar.

Indeed, while the programs under consideration this term have been mostly contemporary –a disaster relief complex for coastal victims of climate change, a DIY factory for dismantling and recycling small homes lost to depopulation–there is clearly something timeless to the texture of these proposals –something perfectly in keeping with the uniquely Japanese sensation of an eternal present.

1 Building as Model – Model as Building I 2018, Building as Model – Model as Building II 2019 , Kit House I 2022, Kit House II 2024, Harvard Graduate School of Design Cambridge USA.

2 2017 London Build Expo, Olympia, roundtable.

3 The stunning quality of this entirely man-made geography appears on undated satellite images, before the village encroached at its margins and the winding down of rice farming gave way to a sprawling undergrowth. The long retaining walls setting out in stone the site’s original contours have since disappeared.

4 The distinctly non-western way of lavishing the same amount of attention on each stage of the design and building process was first reported by Rem Koolhaas in relation to the ritual of the –I quote– ‘Japanese meeting’ minutes of OMA’s Fukuoka Nexus World Housing in 1990.

5 Tafuri, Manfredo Modern Architecture in Japan MACK Publishers edited by Mohsen Mostafavi 2022

6 Barthes, Roland (1915-80) Empire of Signs (originally 1970) English edition Published by Hill and Wang, 1983

A Ziyang Xiong

B Zachary Slonsky

C Regina Pricillia

D Ann Tanaka

E Esteban Vanegas

F Nicky Rhodes

G Jeya Wilson

H Lou Xiao

I Ella Larkin

J Keane Chua

K Elise Hsu

L Souroush Ehsani-Yeganeh

Ziyang Xiong

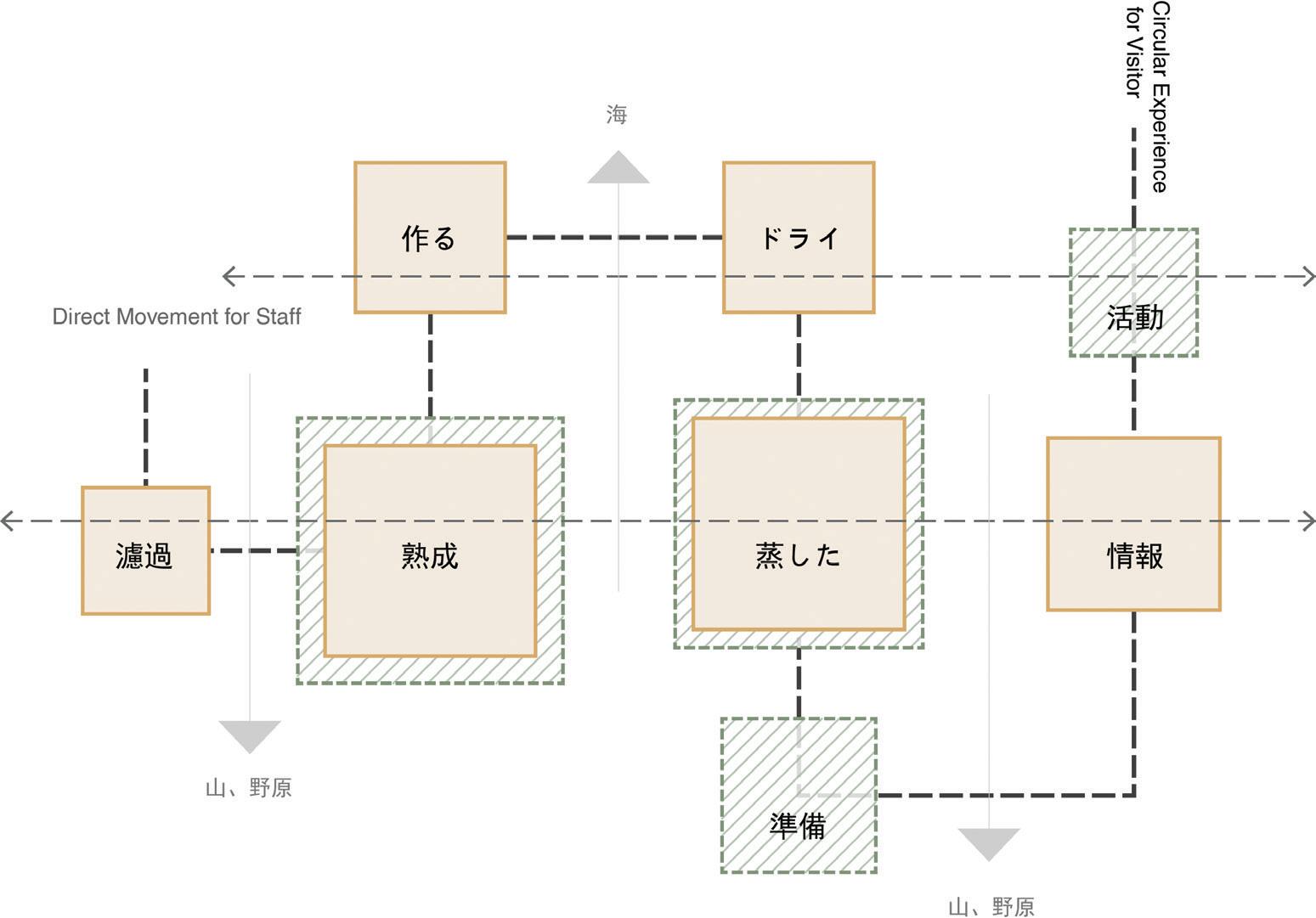

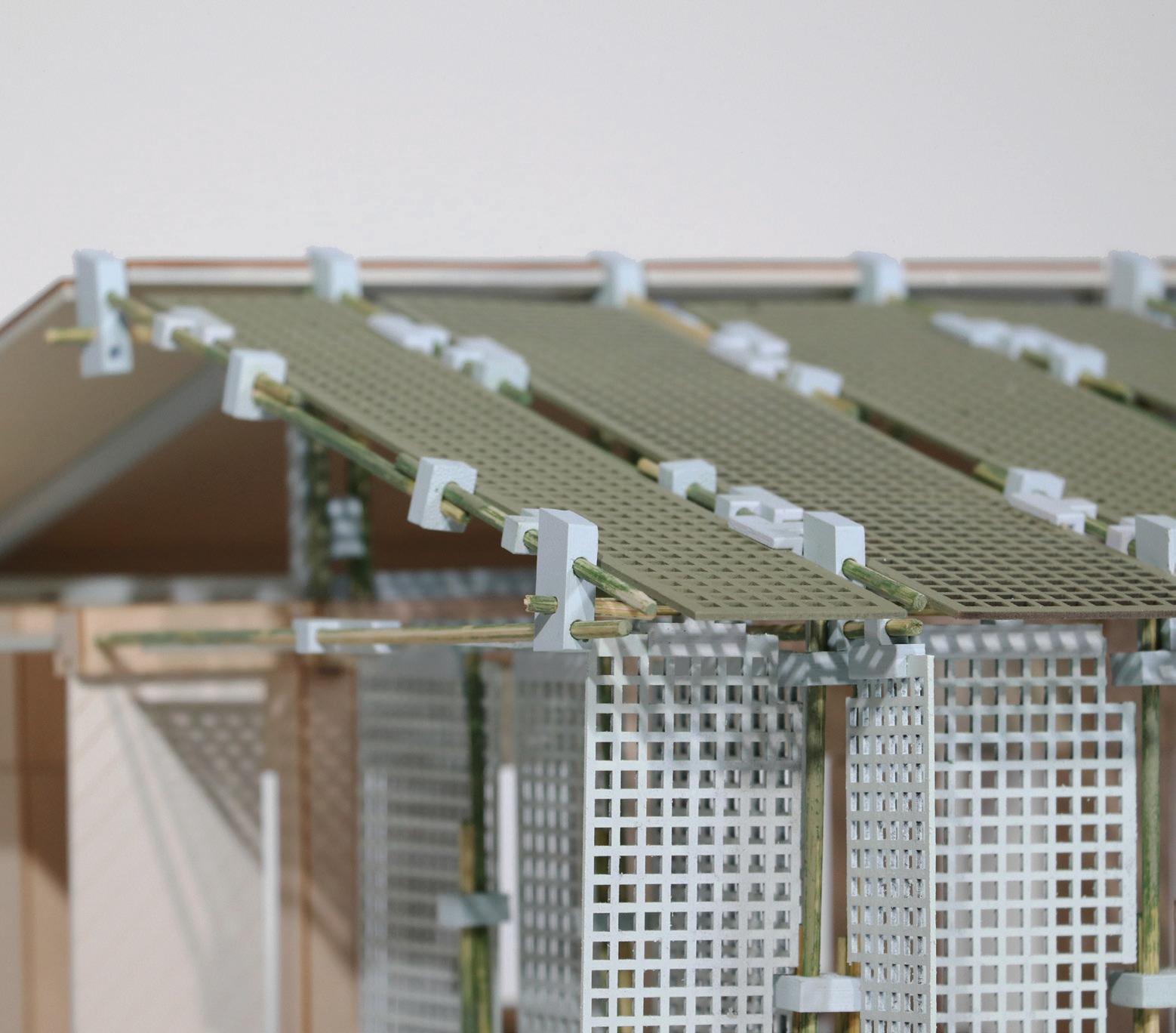

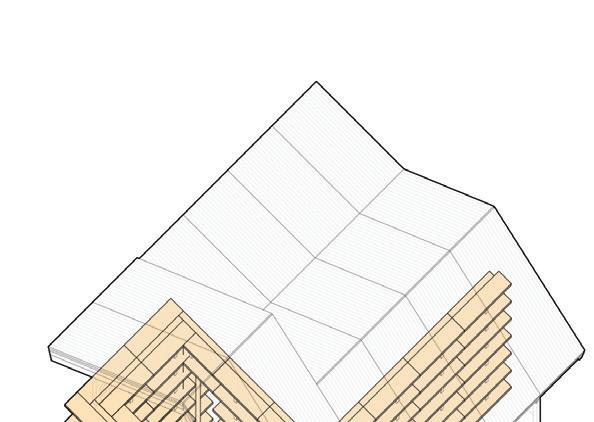

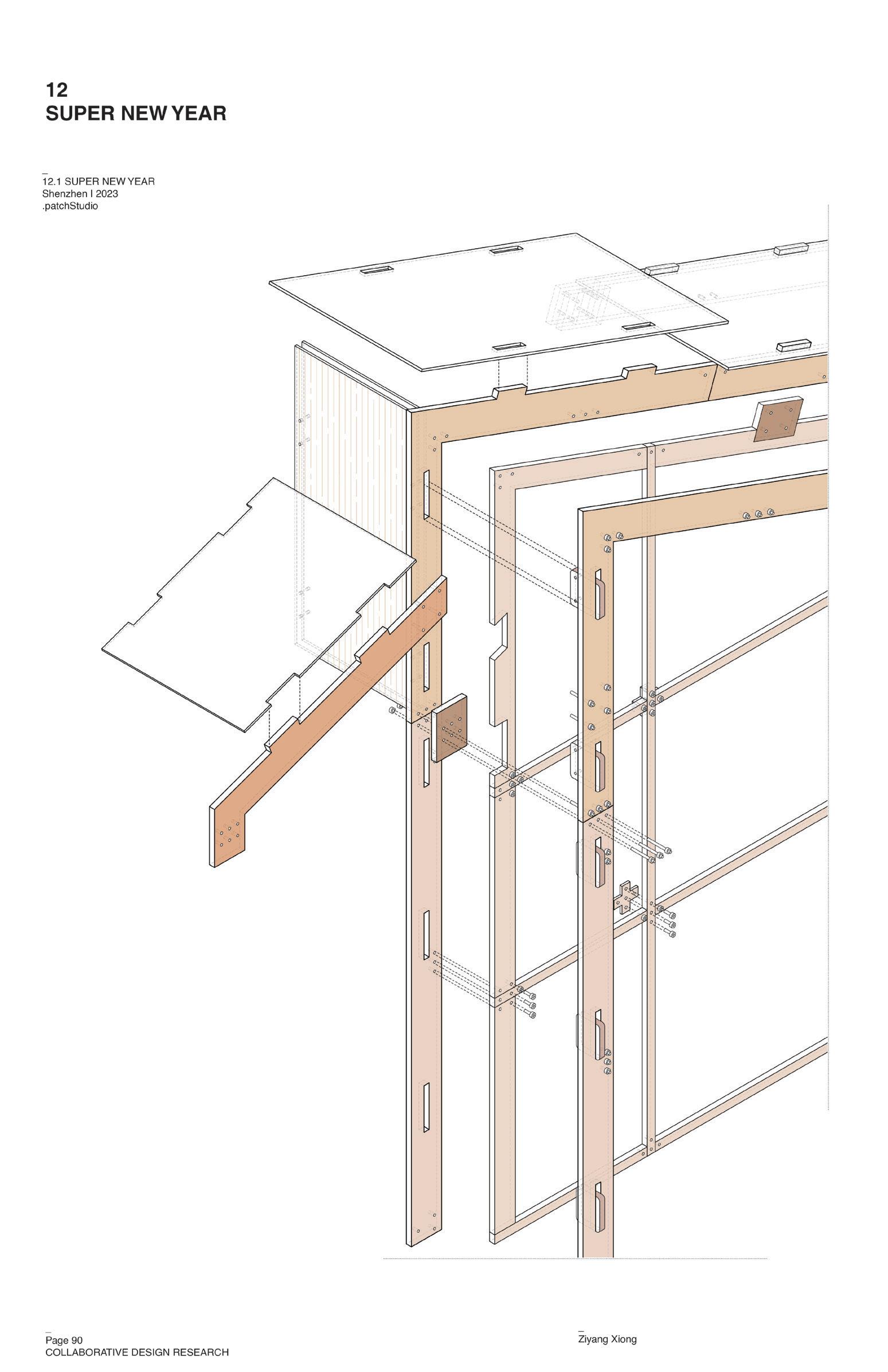

This project explores an experimental application of OSM within the Japanese rural context. It aims to reinterpret traditional rural architecture—its concepts, structures, and materials—through a modular system that can flexibly adapt to the needs of diverse local industries, contributing to rural revitalization.

The specific program is a combined sake workshop and information center, serving as a multifunctional hub where locals and tourists can work, learn, and connect.

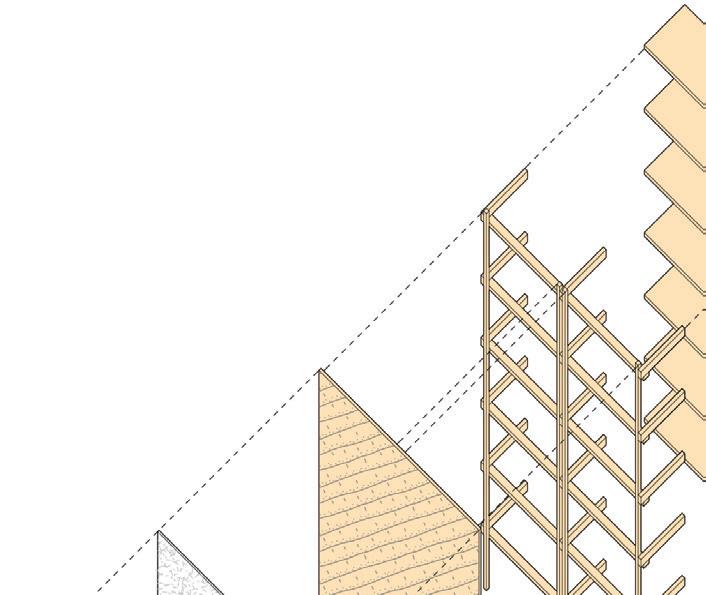

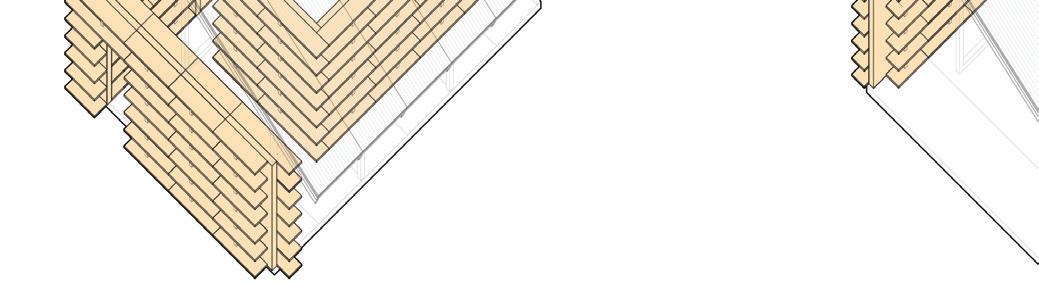

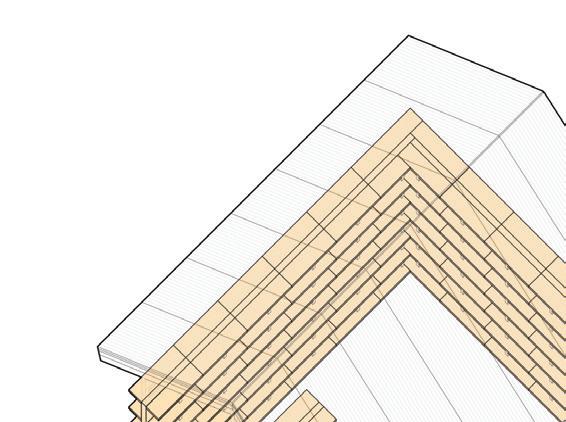

The system is composed of two interdependent modules: a solid timber module and a lightweight bamboo module. The timber module forms a refined, grounded “massing,” while the bamboo wraps around it like a “cloud,” introducing lightness and transparency. Together, they generate a dynamic range of spatial experiences and scales suited to different functions. Structurally and spatially, the modules are designed to support one another, embodying a symbiotic architectural relationship.

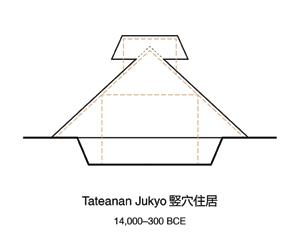

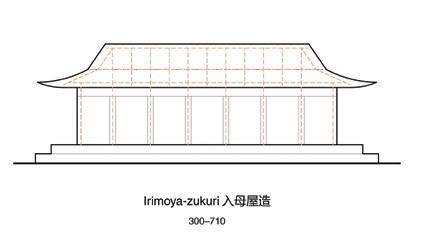

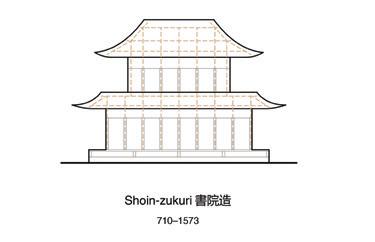

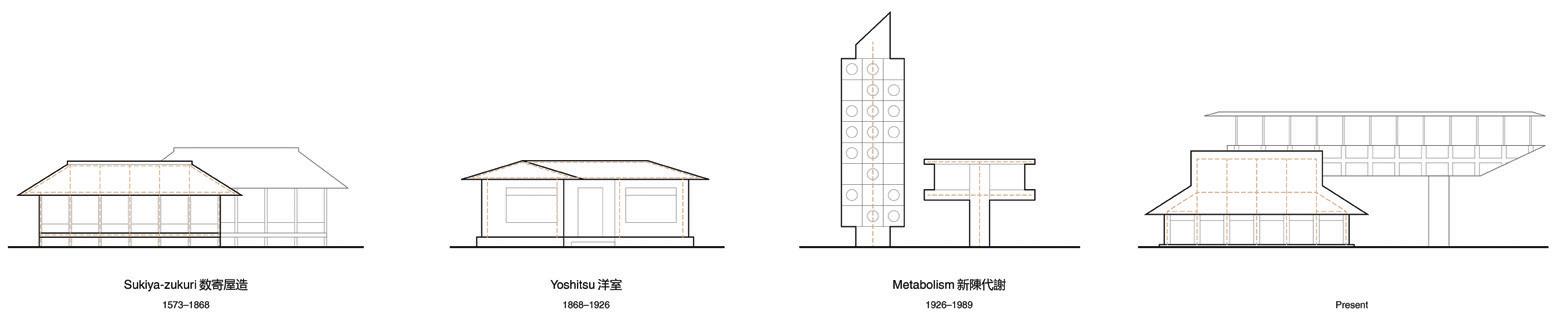

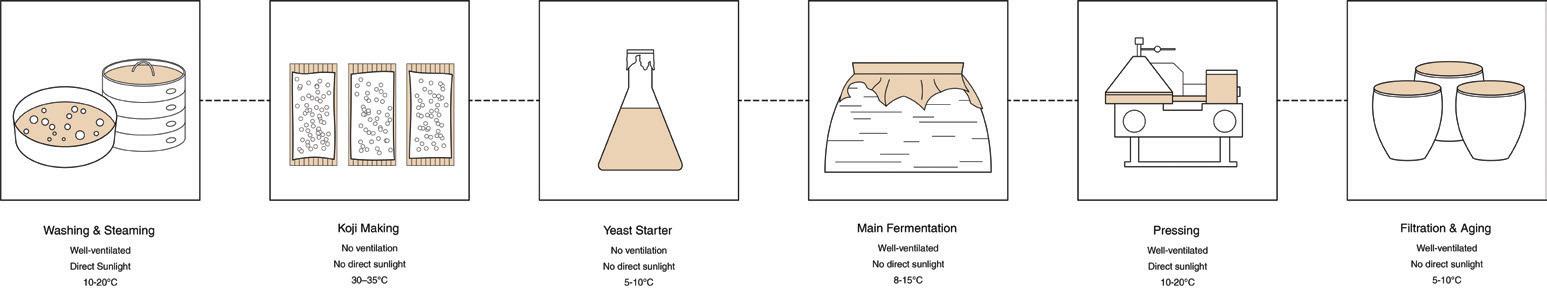

Previous page top: Formal analysis Japanese formal styles and ideas showing the production of sake

Previous page bottom: Circulation diagram showing programming adjacencies Top: Building massing diagram studies

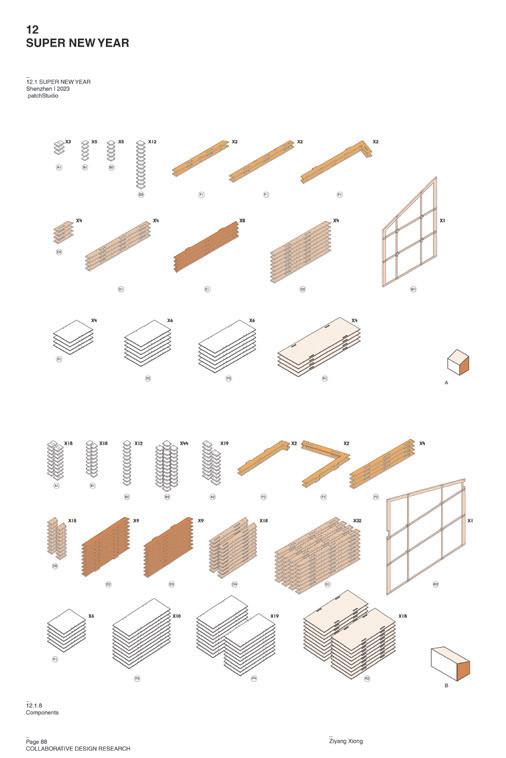

Above and following page: Components used in

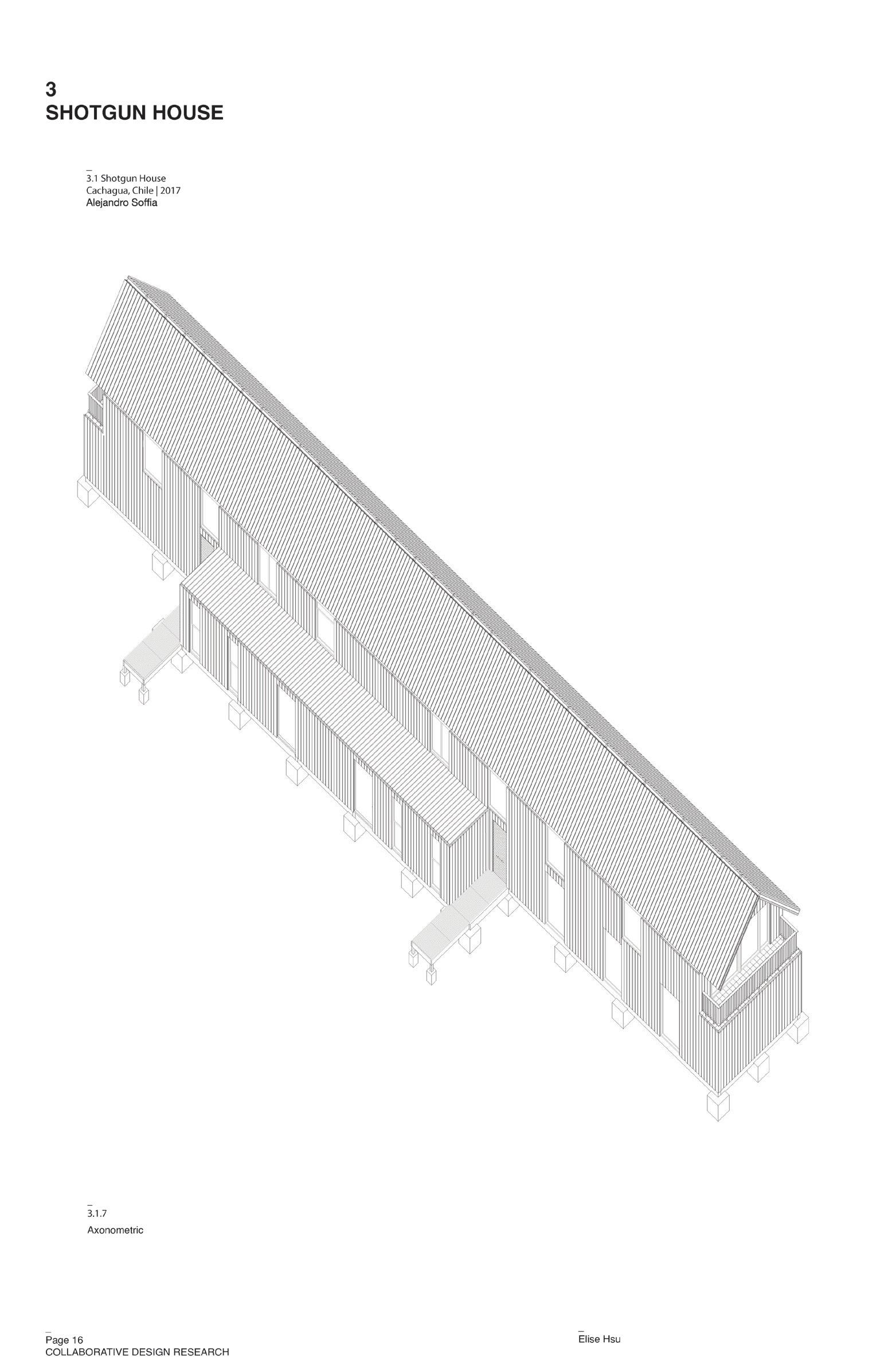

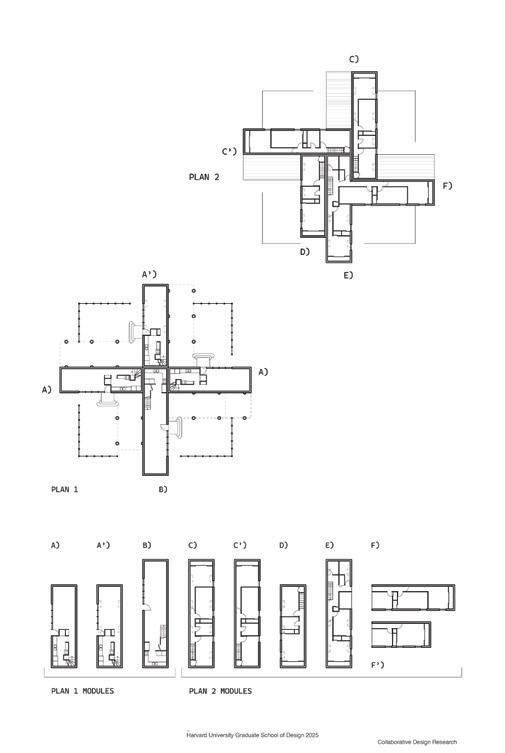

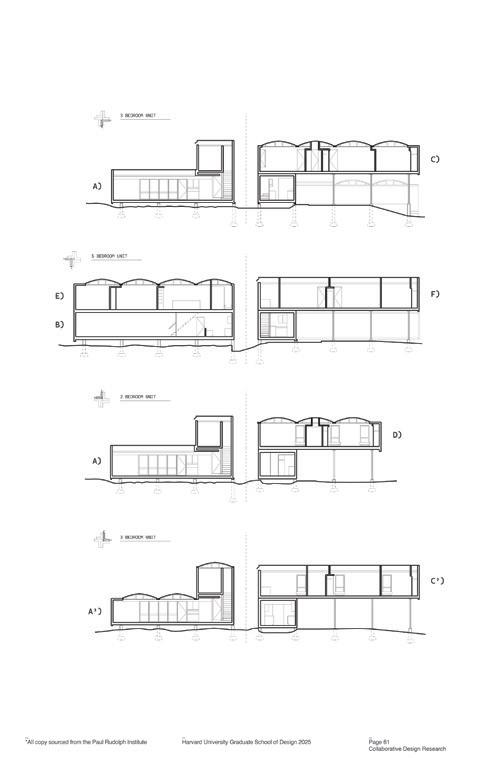

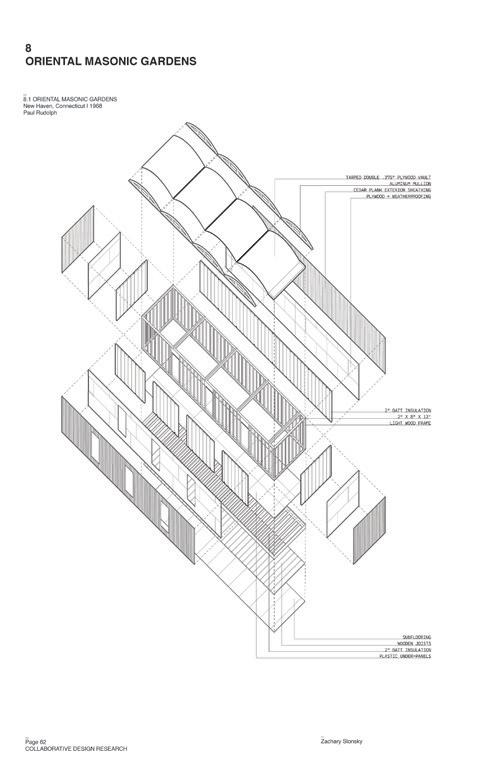

Zachary Slonsky

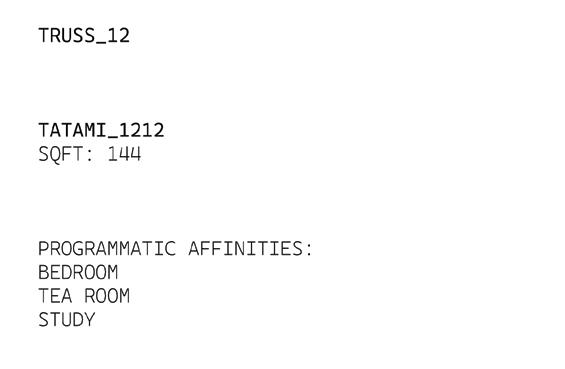

A couple of thousand years before Mies, Japanese building culture circumnavigated the load-bearing wall, celebrating the opportunity for a fluid, open space. Post and lintel construction systems were the norm, with walls, floor, and ceiling elements designed specifically to fill the spaces in between. The modernist grid, in charge of regulating proportions and ensuring the Fordist schematic for interchangeable parts, was inscribed by the tatami mat. This approach enabled building labor to be divided amongst the buildings’ constituent components- each artisan could work independently, with the confidence that their work would cohere within the final assemblage. Carpenters, weavers, papermakers, illustrators, blacksmiths, and ceramicists were all upheld by the orchestra of Traditional Japanese Architecture.

The pre-modern modernity sparks the motive of this project. The following pages propose a contemporary model for an architecture which negotiates global material, economic, and labor conditions with local identity, history, and institutions. It proposes the future of work as an artist residency, which is itself a typology for bridging these gaps.

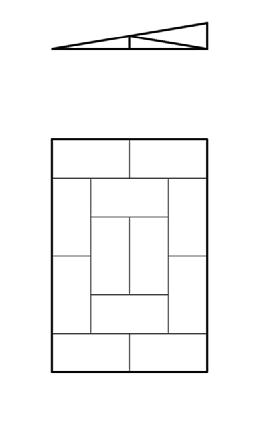

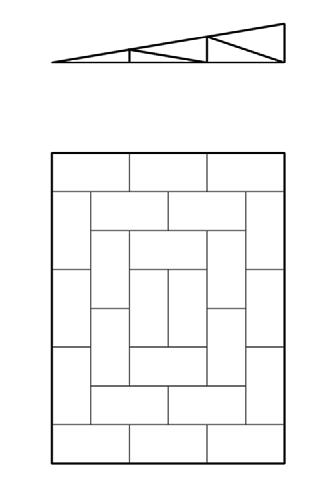

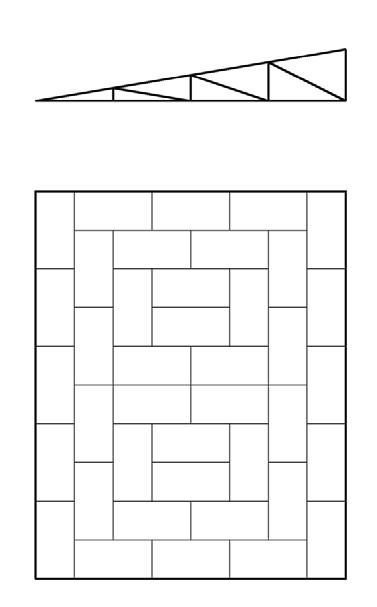

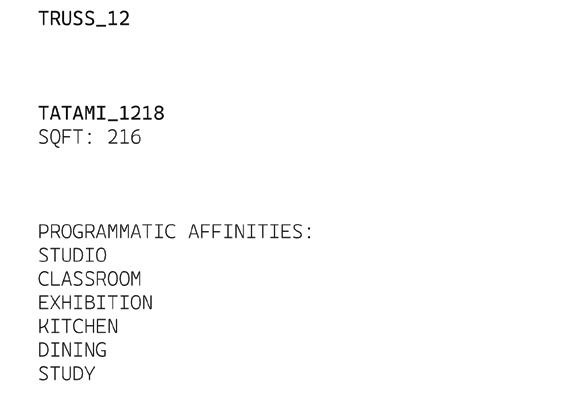

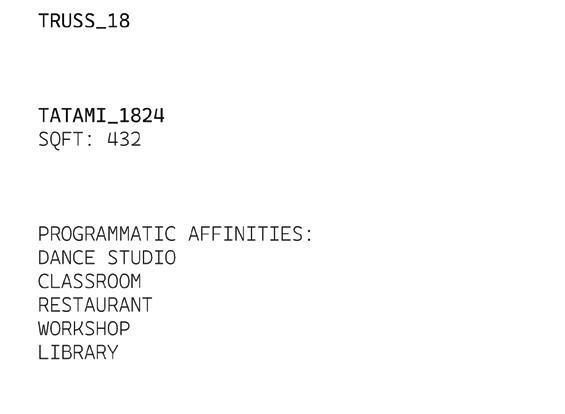

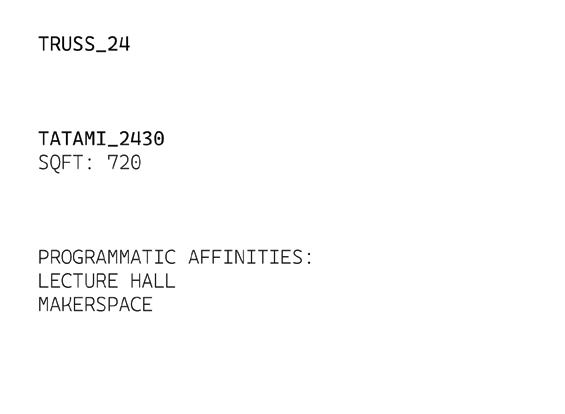

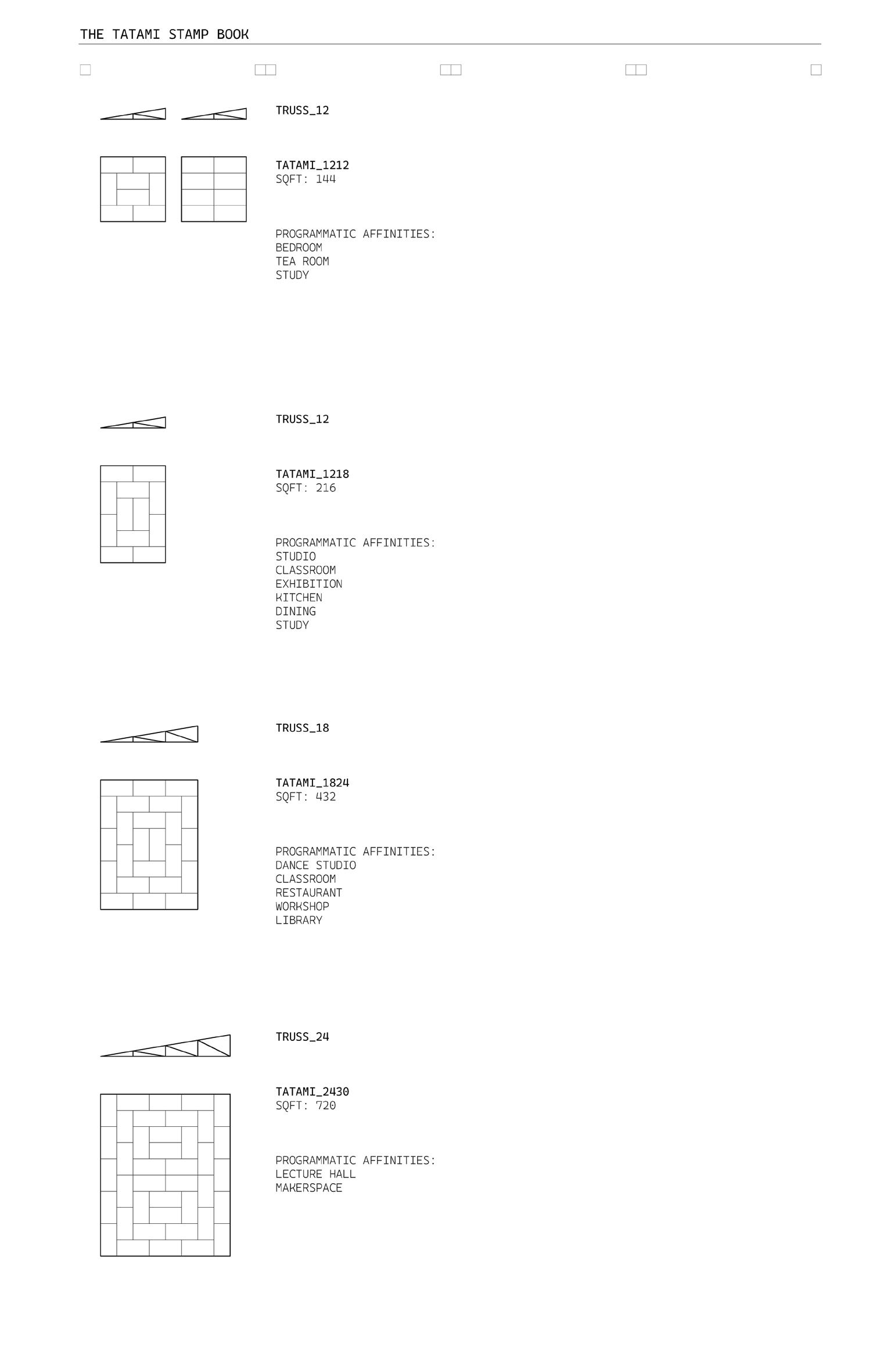

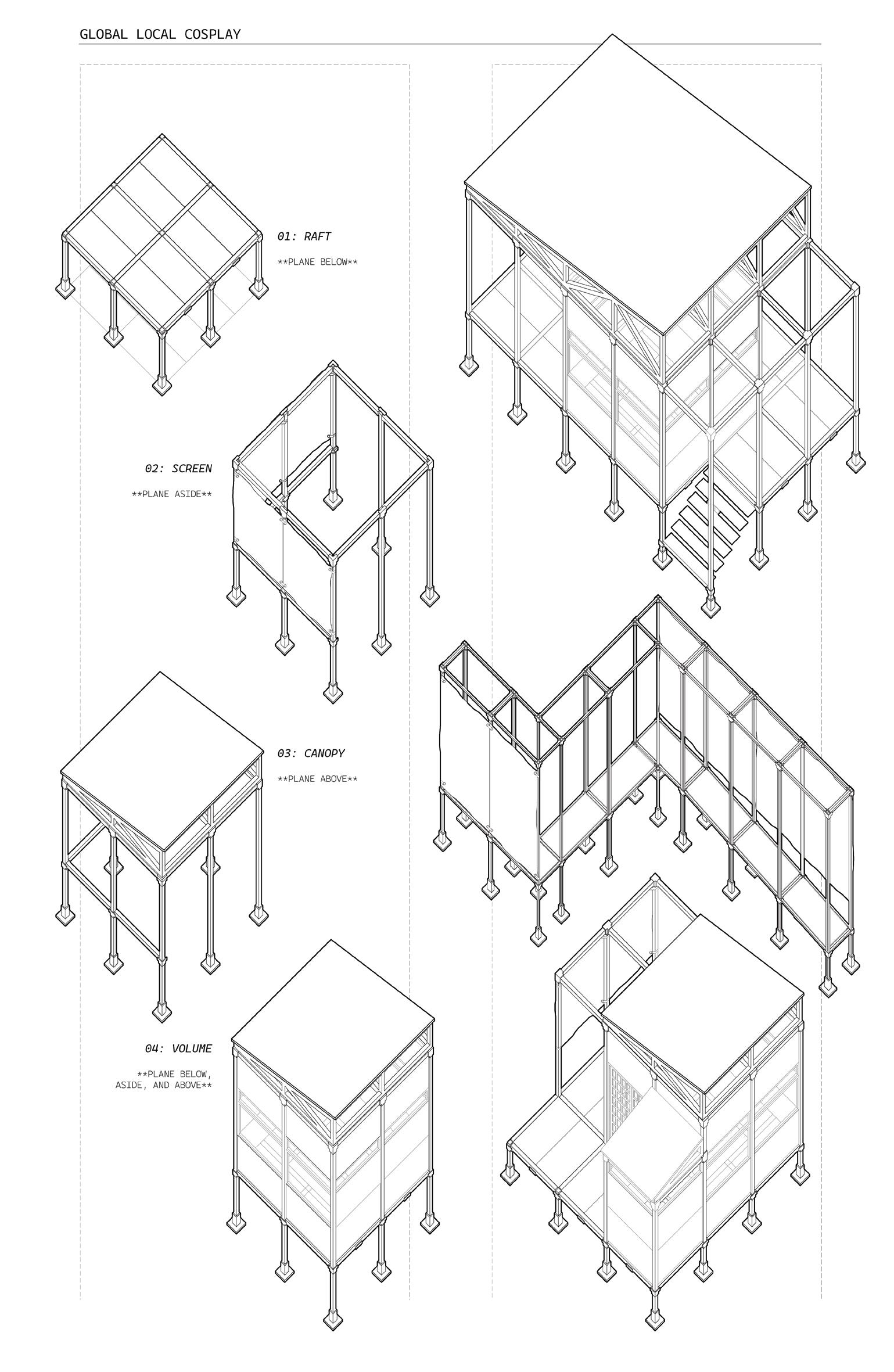

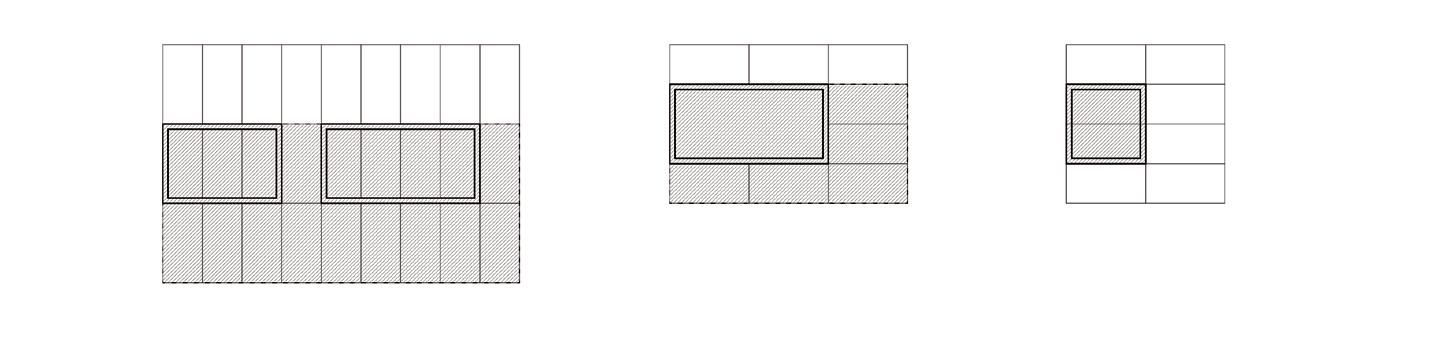

Above: This system is coordinated by the tatami mat, which forms the base aggregate unit for the mid-scale expression. The following tatami patterns are considered “lucky” because they never let four corners meet.

Above: Four mid-scale formal conditions can extend from the

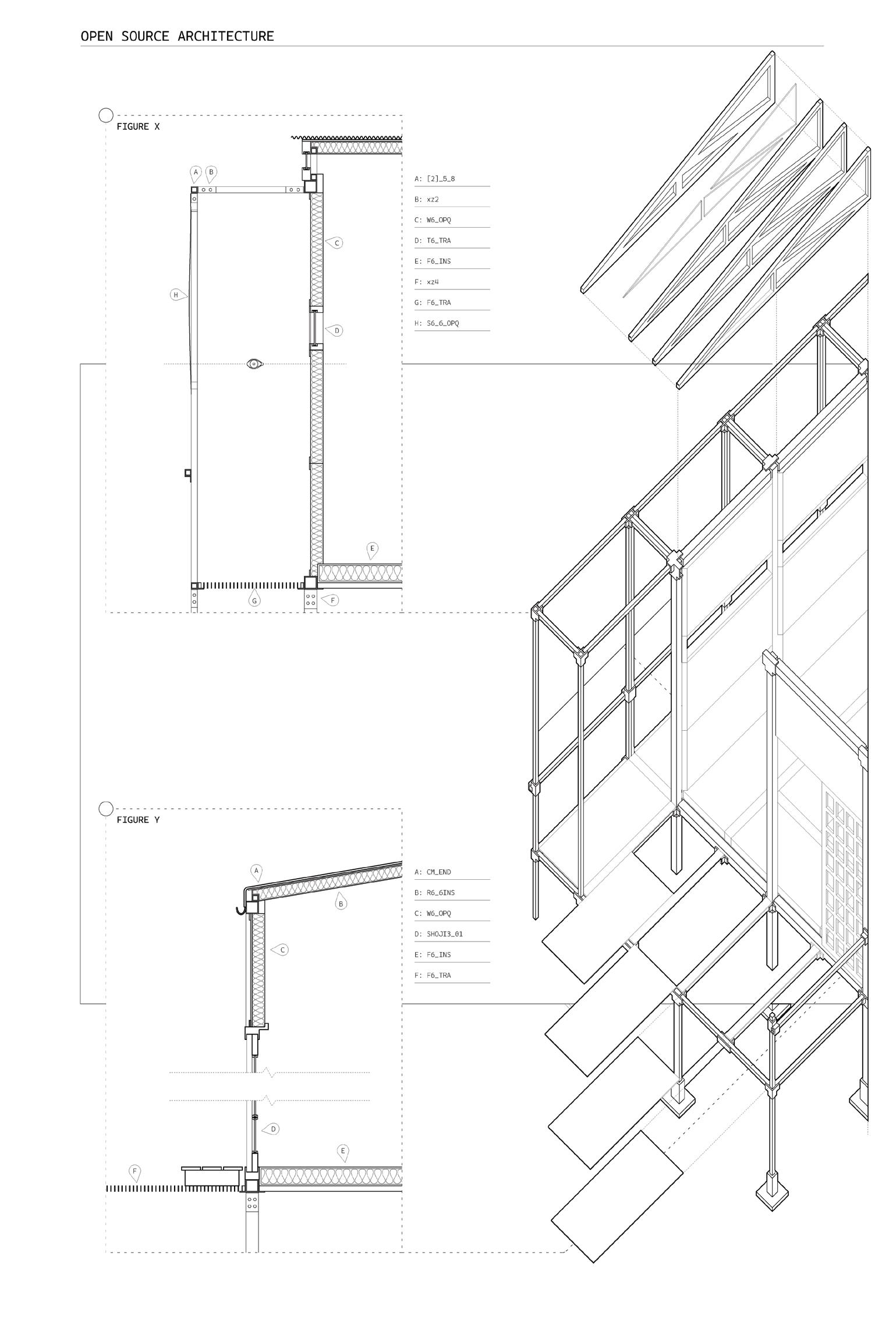

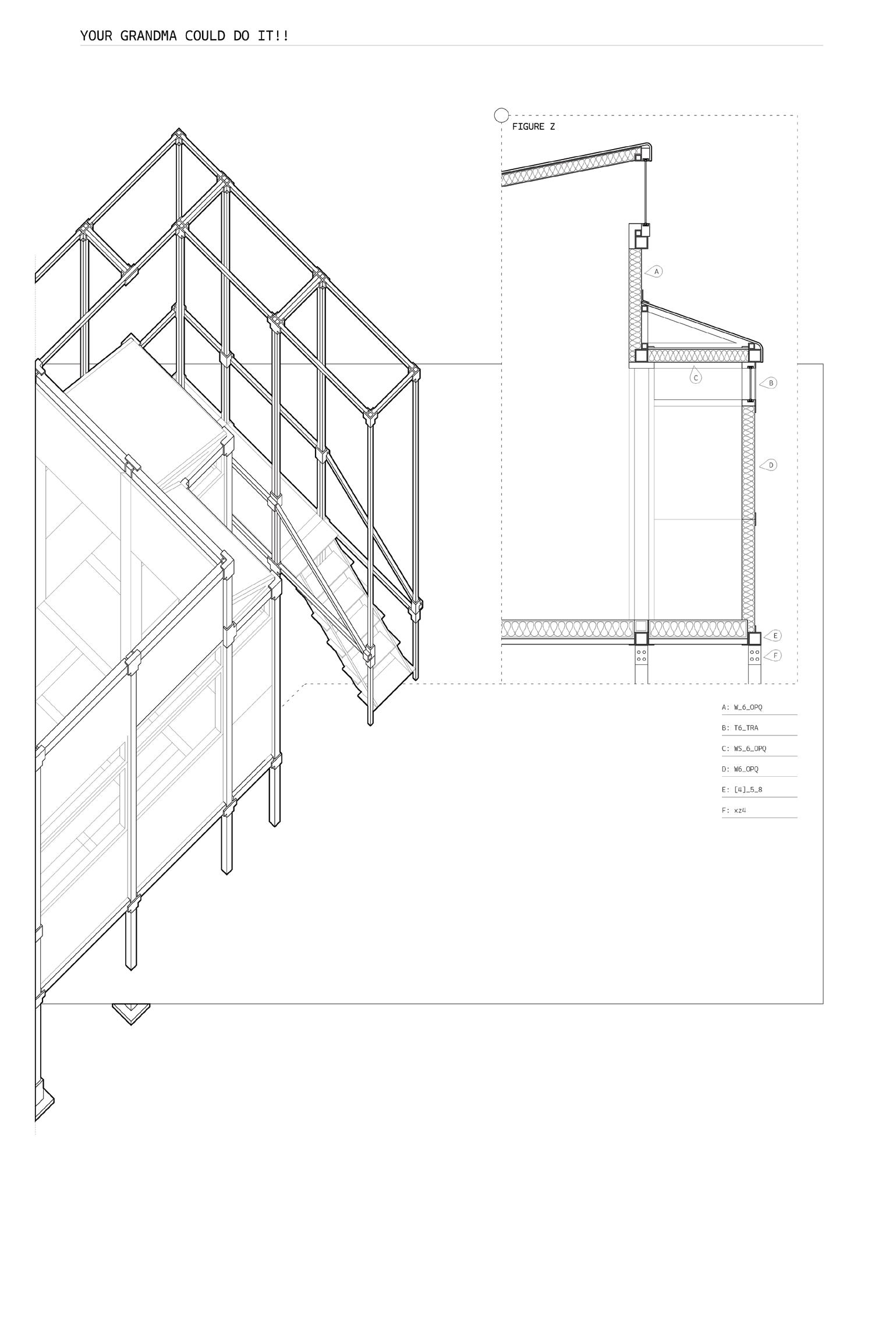

Above: The process of adapting a readymade architecture to a specific condition practices a similar logic to that of opensource software, where source code is provided as a substrate, and user-made libraries elaborate more idiosyncratic formulations.

Above: While the system is first designed formally – with later extrapolations around what sorts of activities could happen across the diversity of its spaces – once it is designed, it then becomes used in reverse.

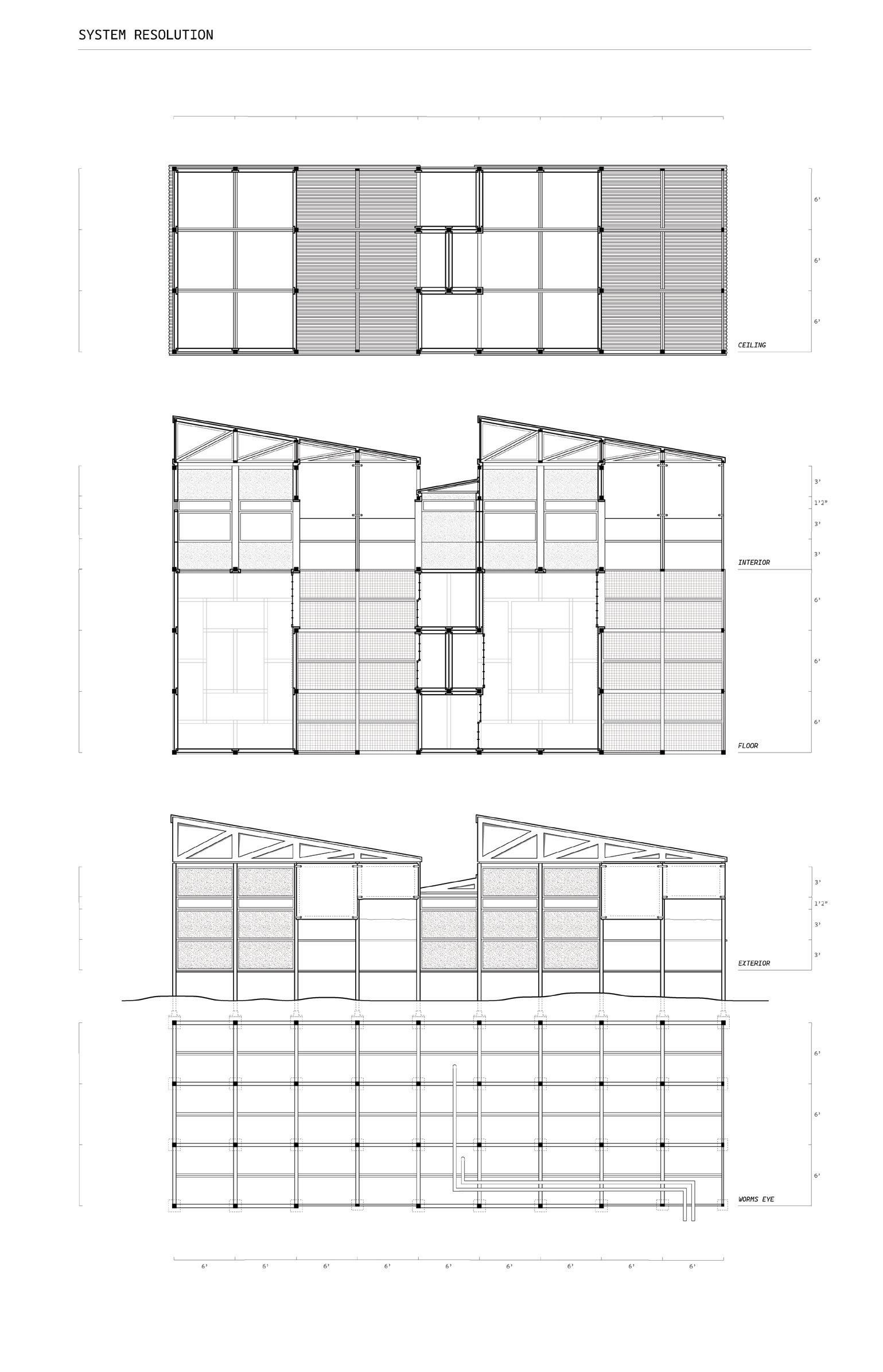

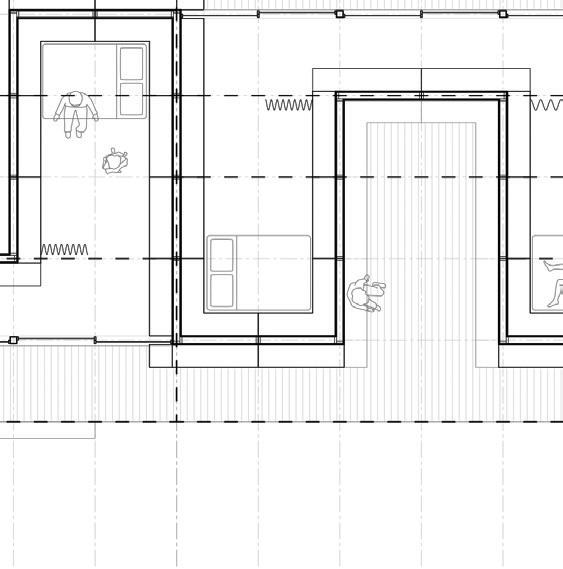

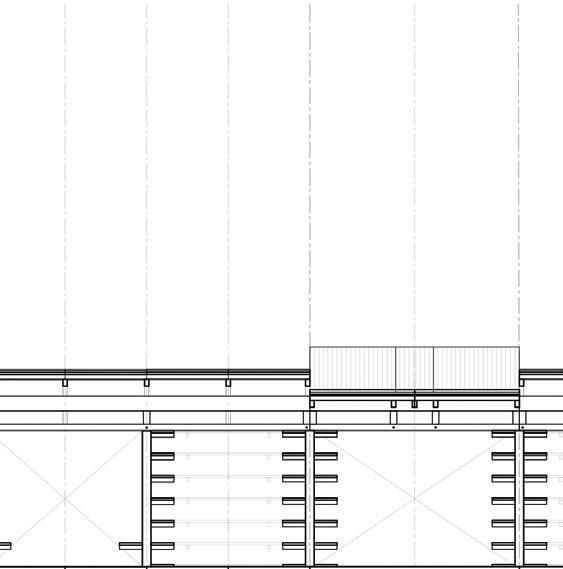

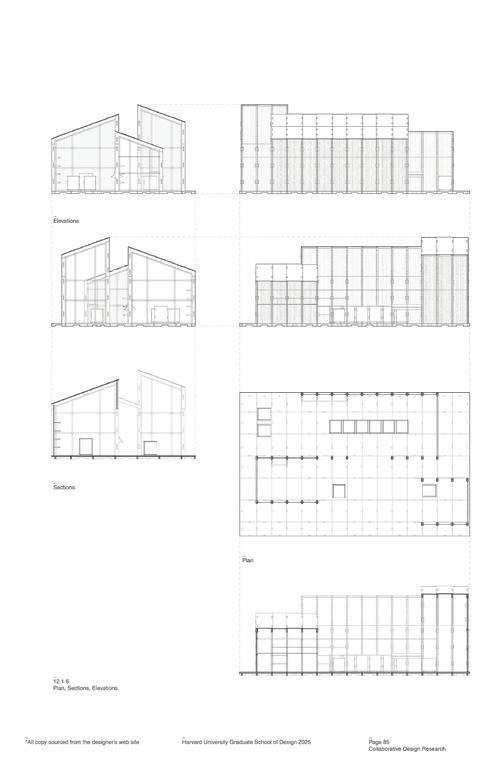

Above: Drawings showing system resolution using plans, sections and elevations

Bottom: Detail showing the model of a portion of the system that may be aggregated to create novel spaces based on needs.

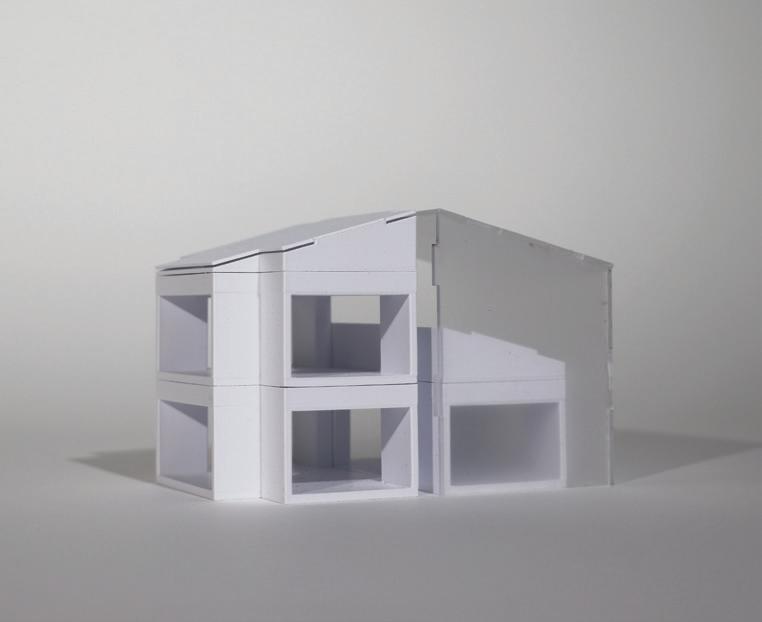

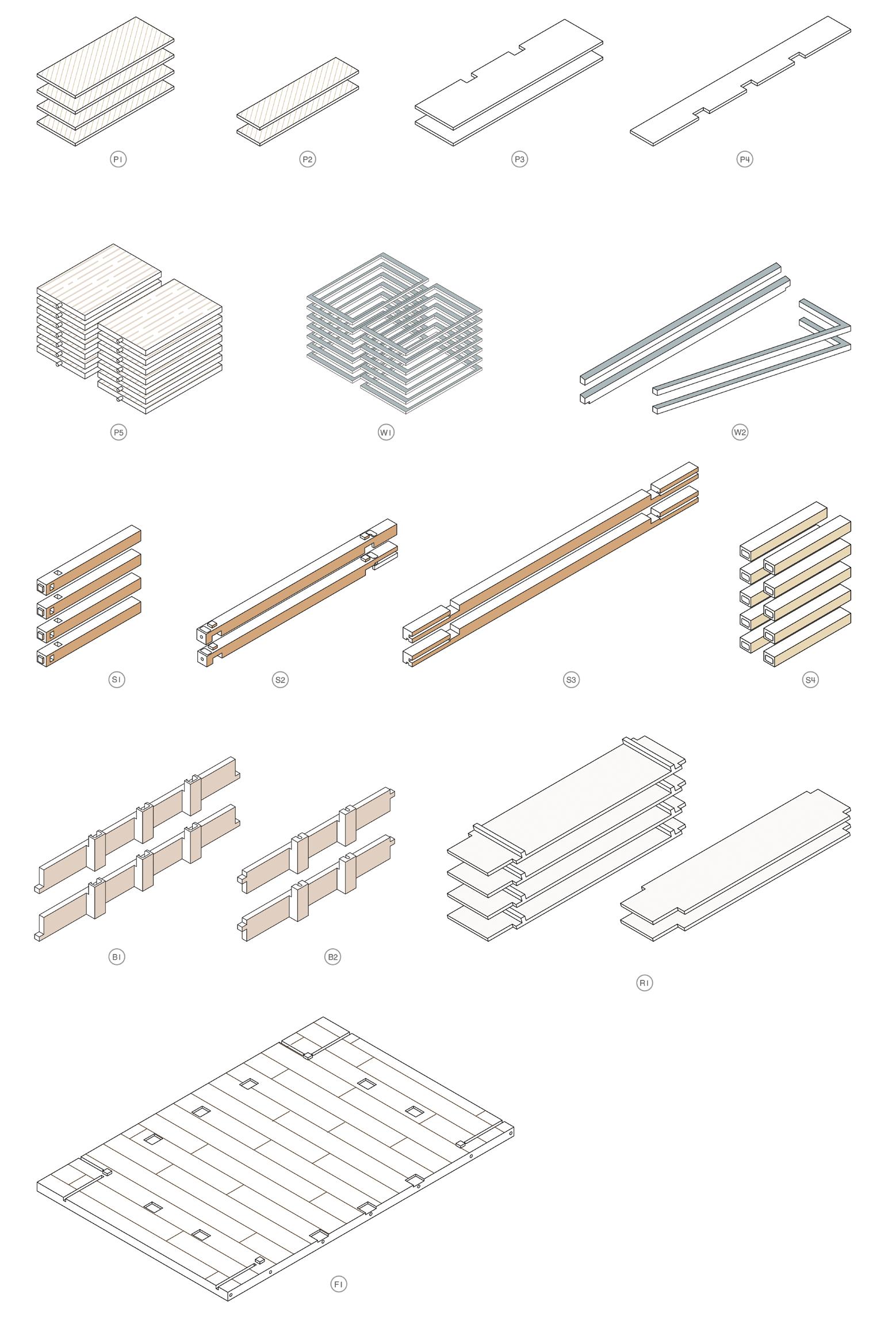

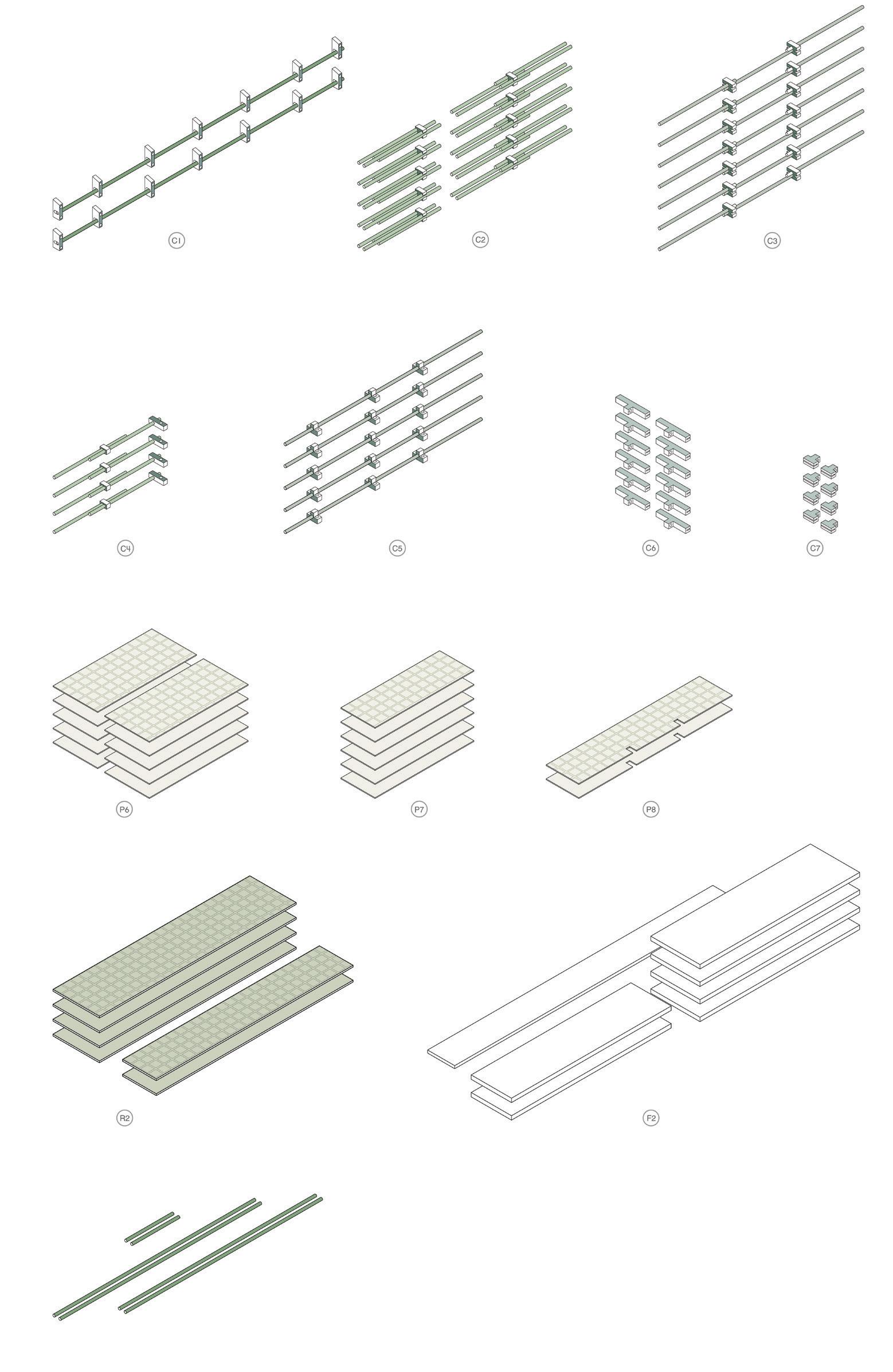

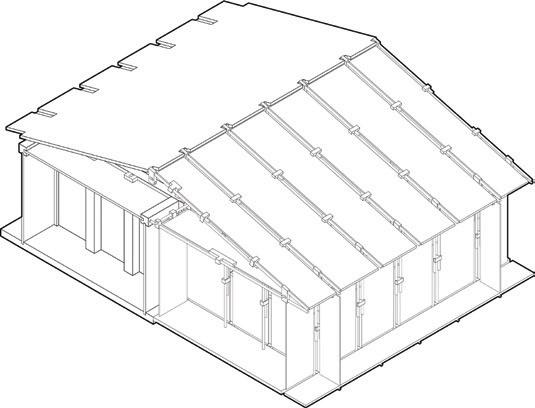

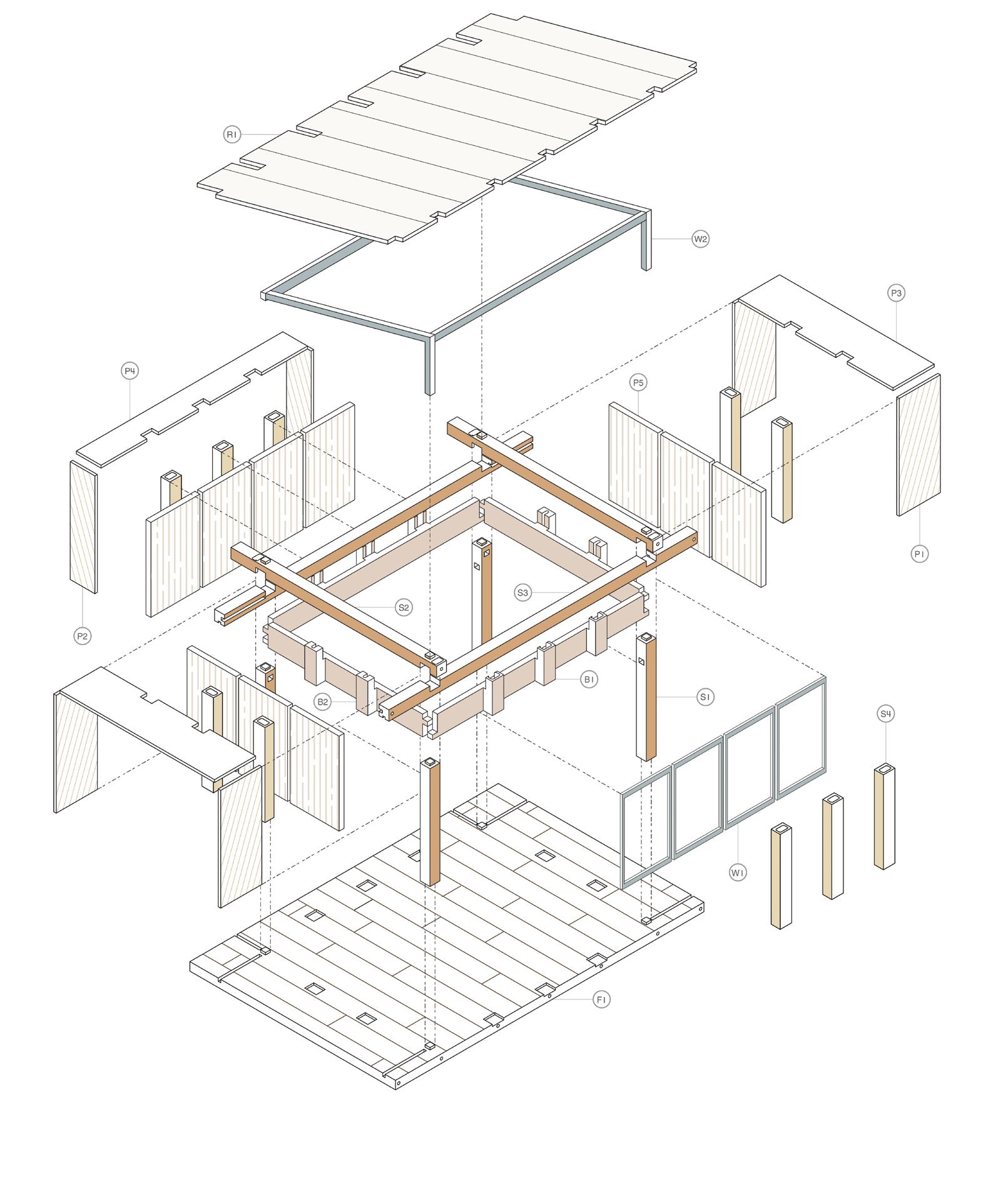

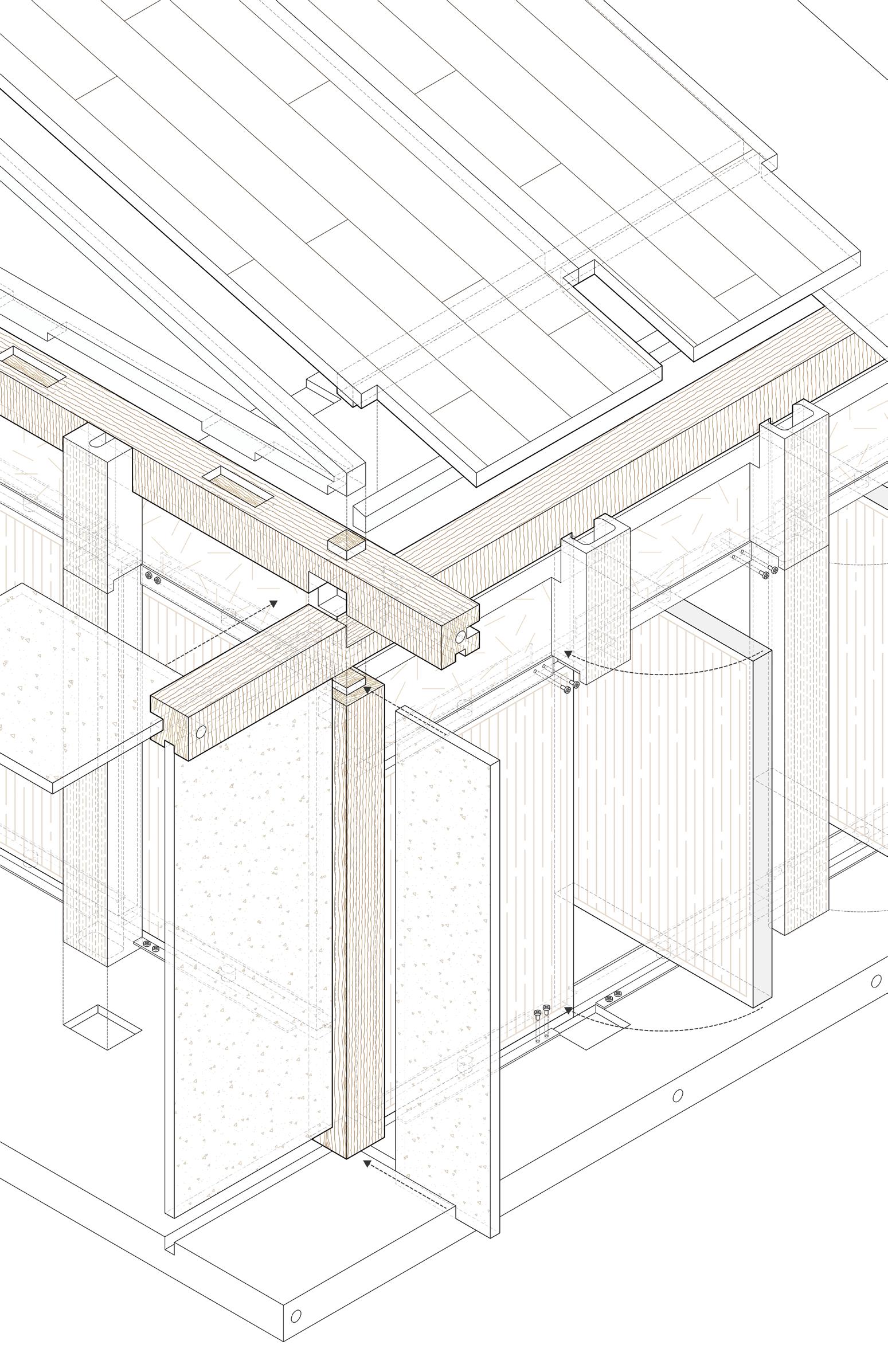

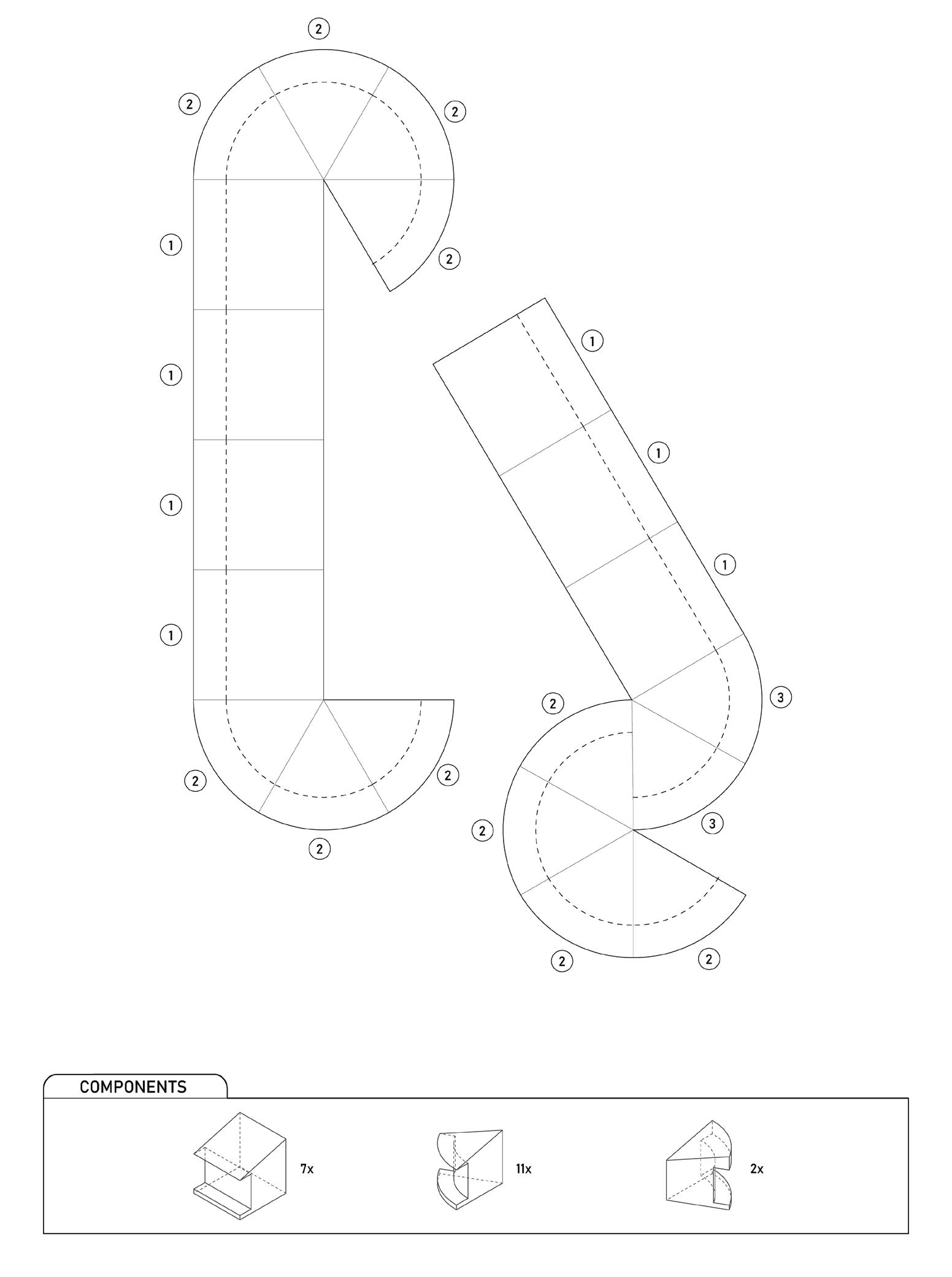

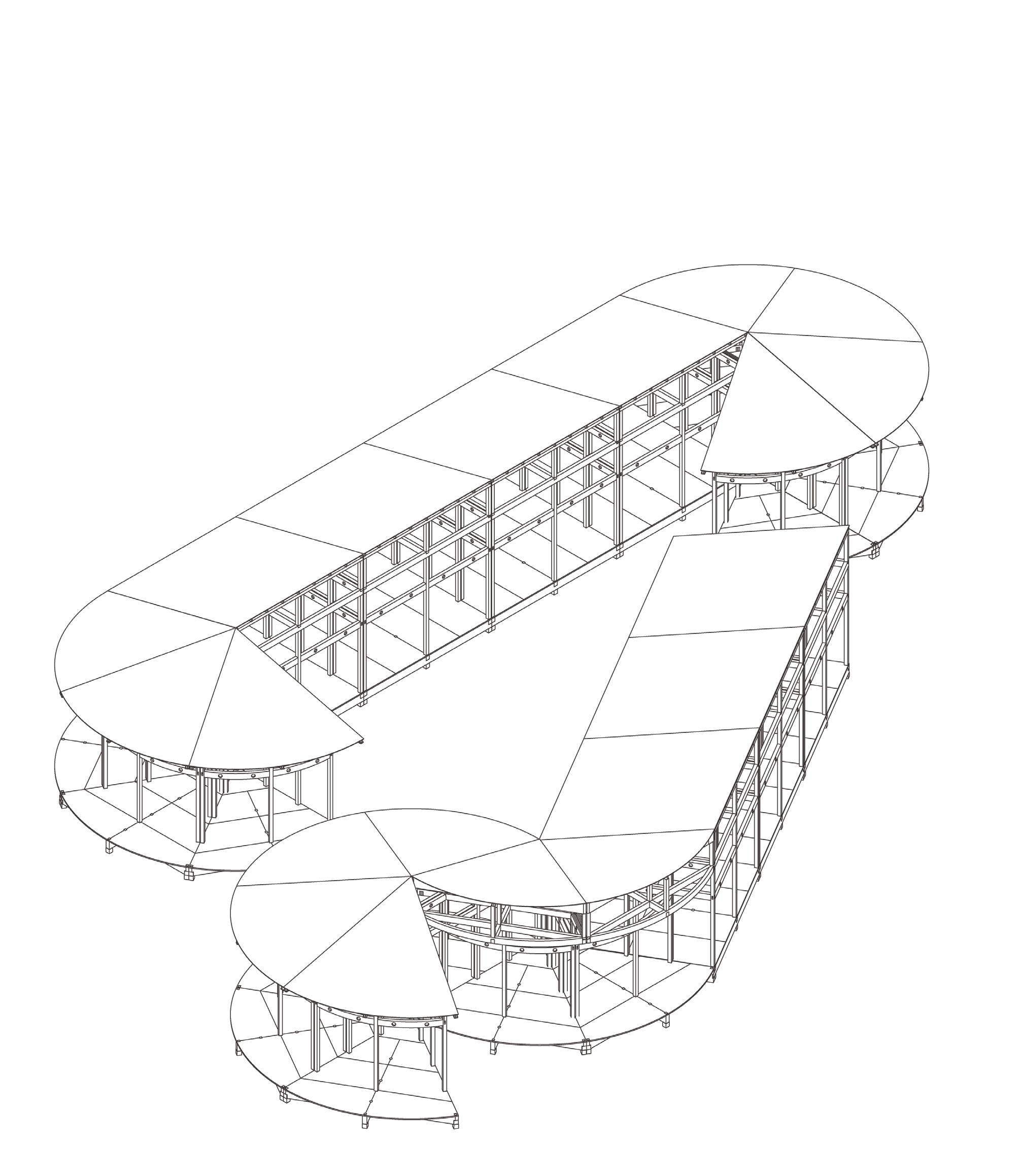

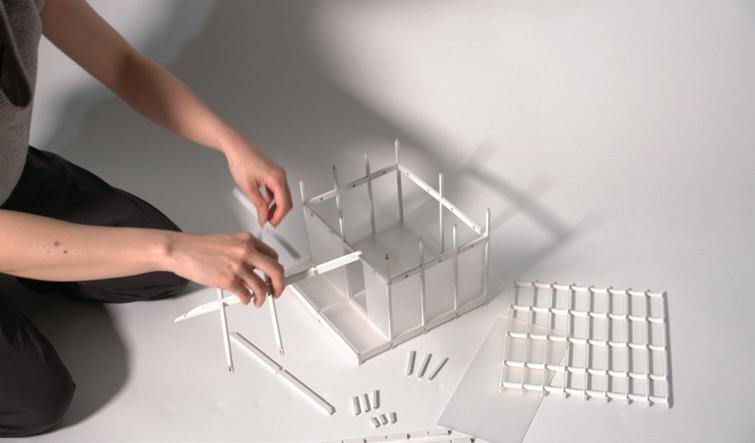

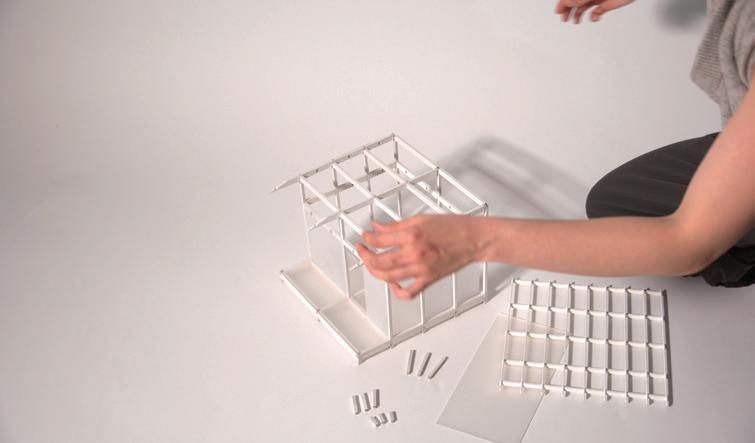

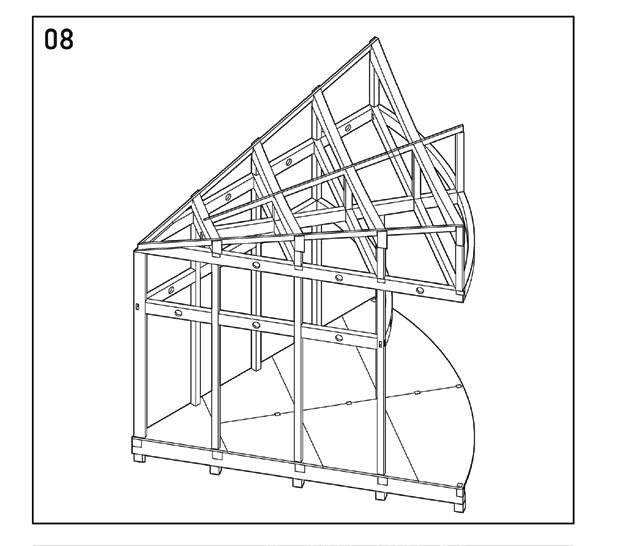

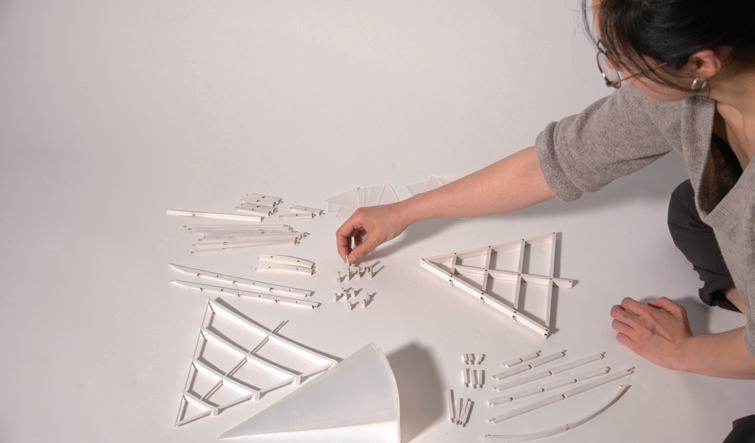

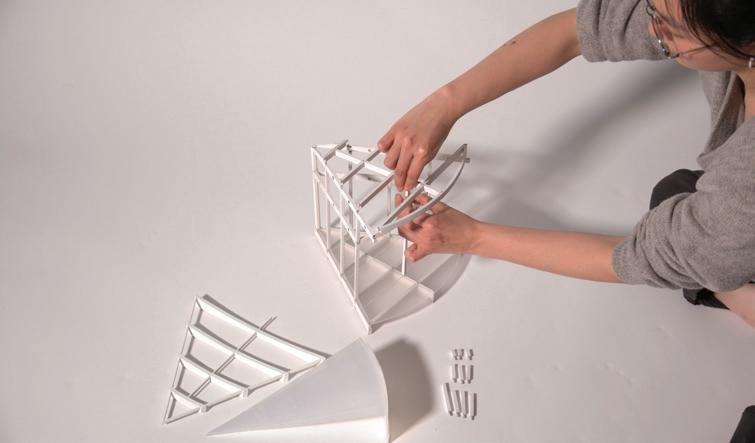

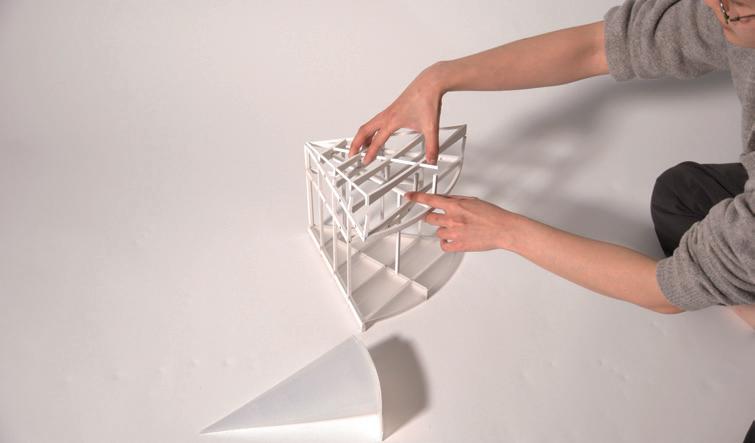

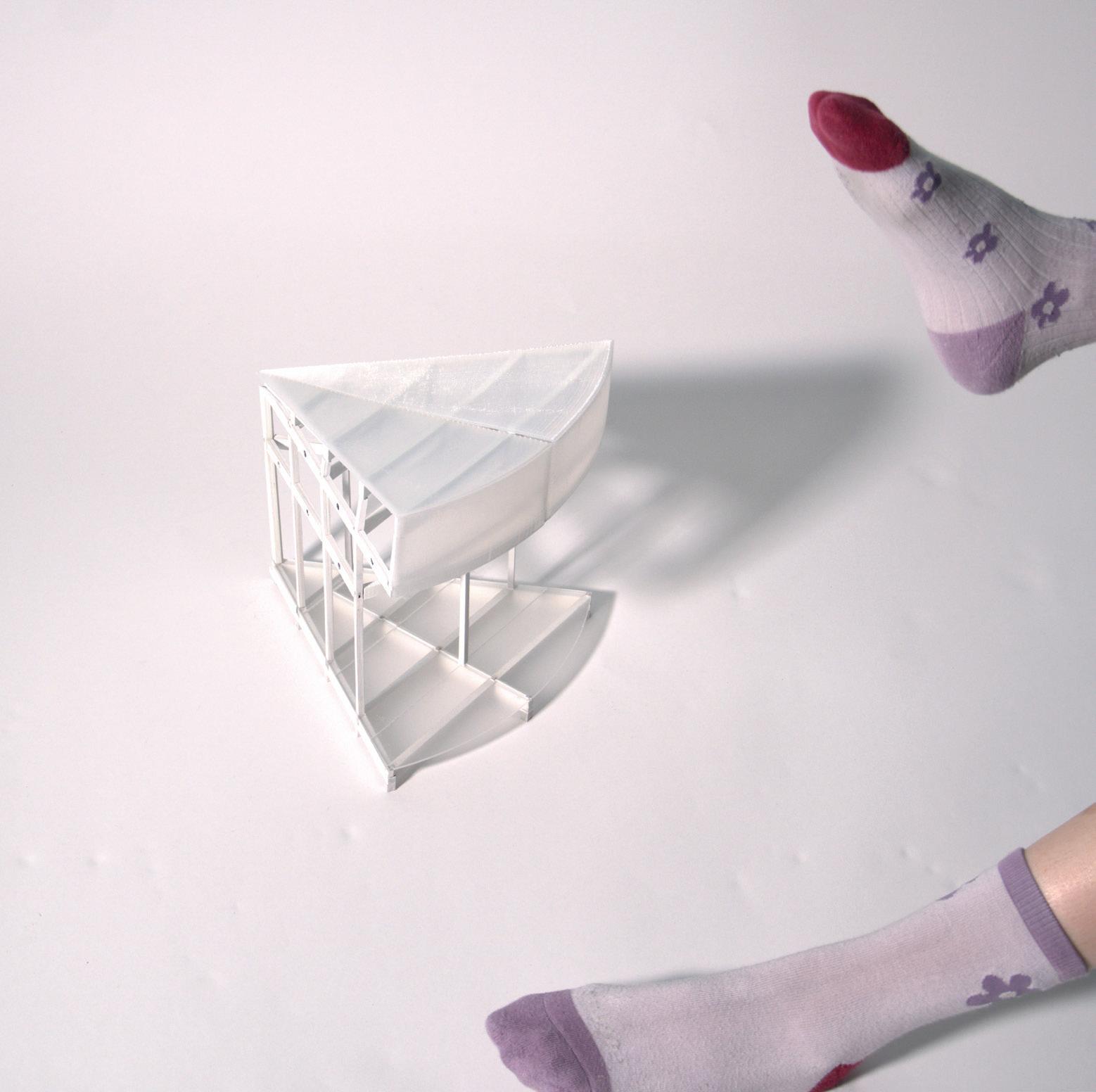

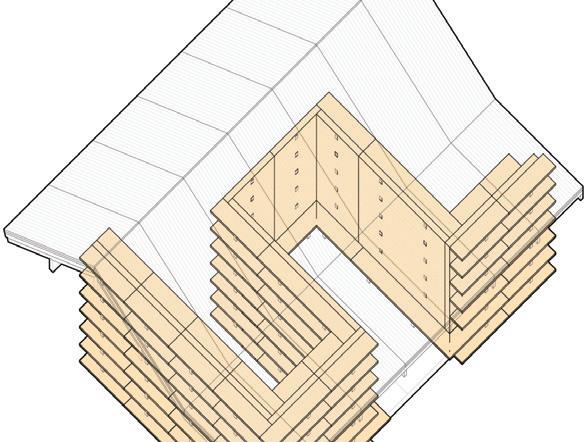

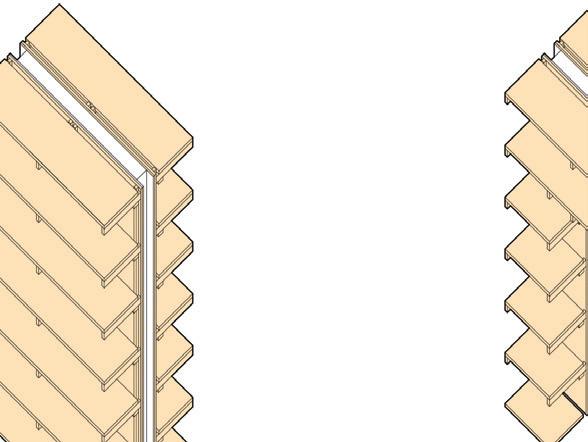

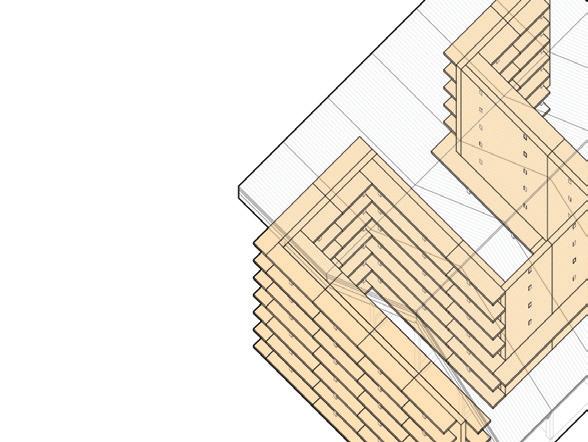

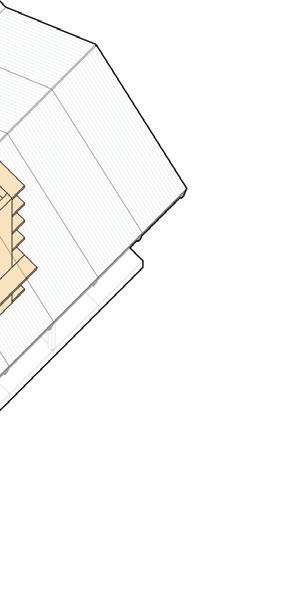

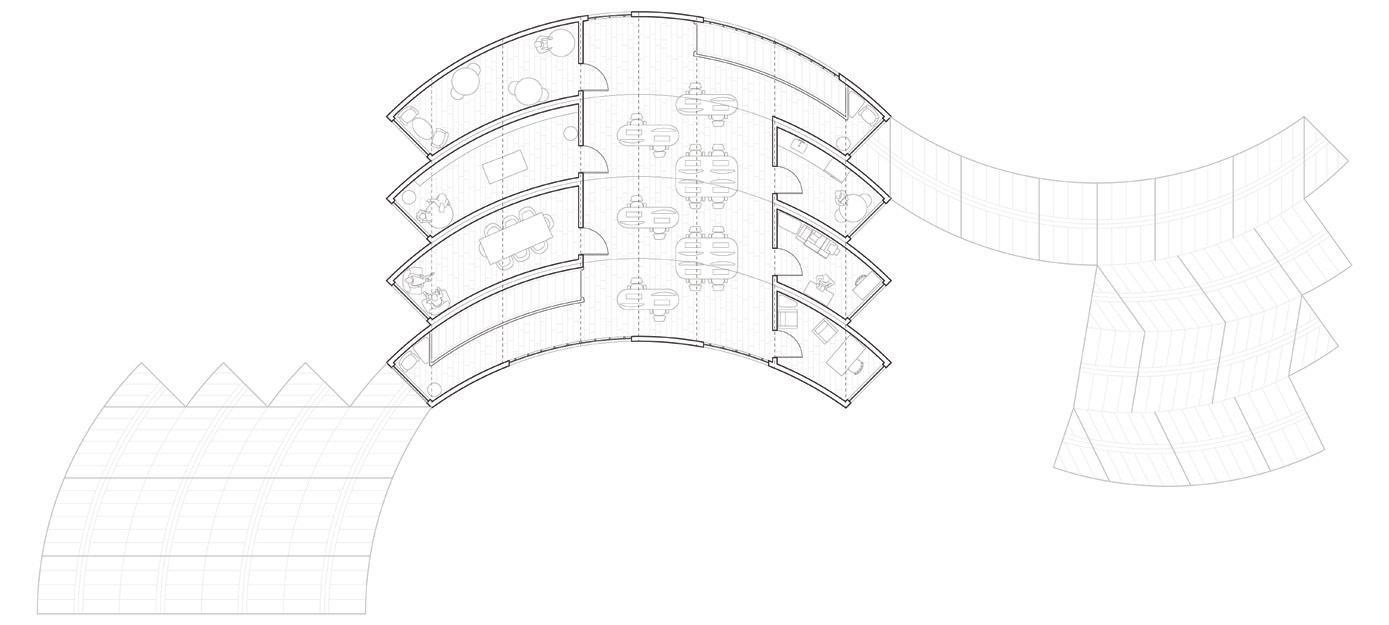

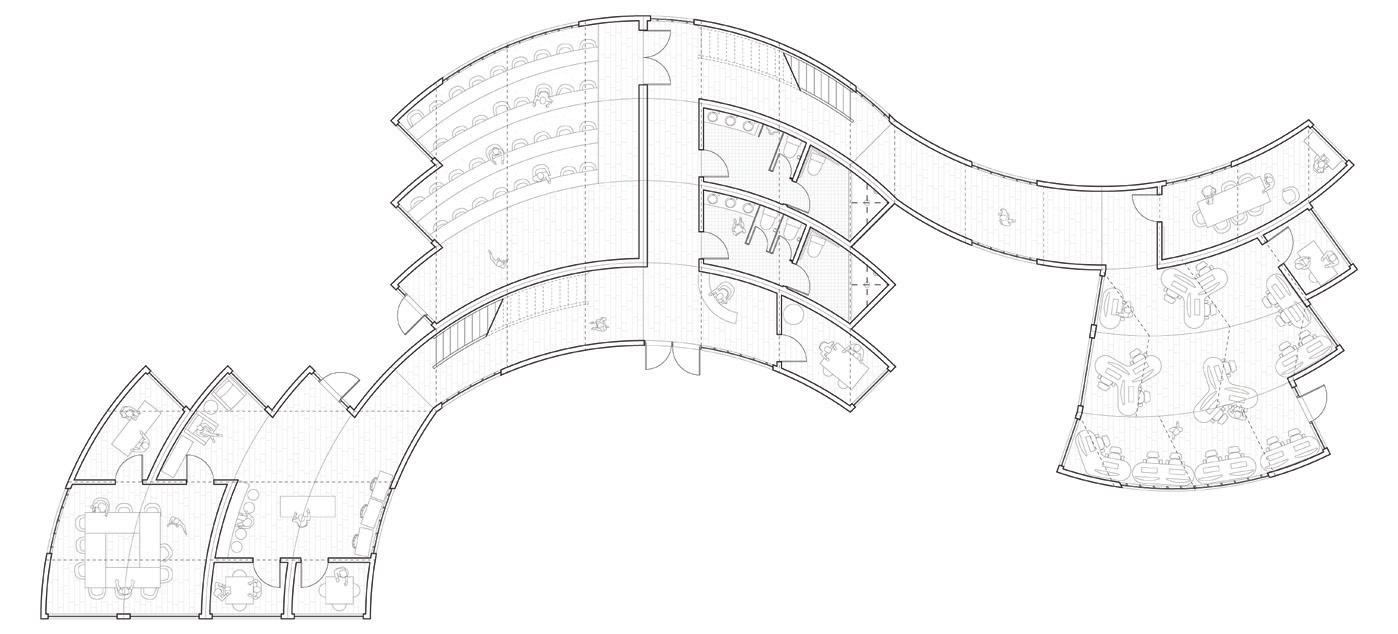

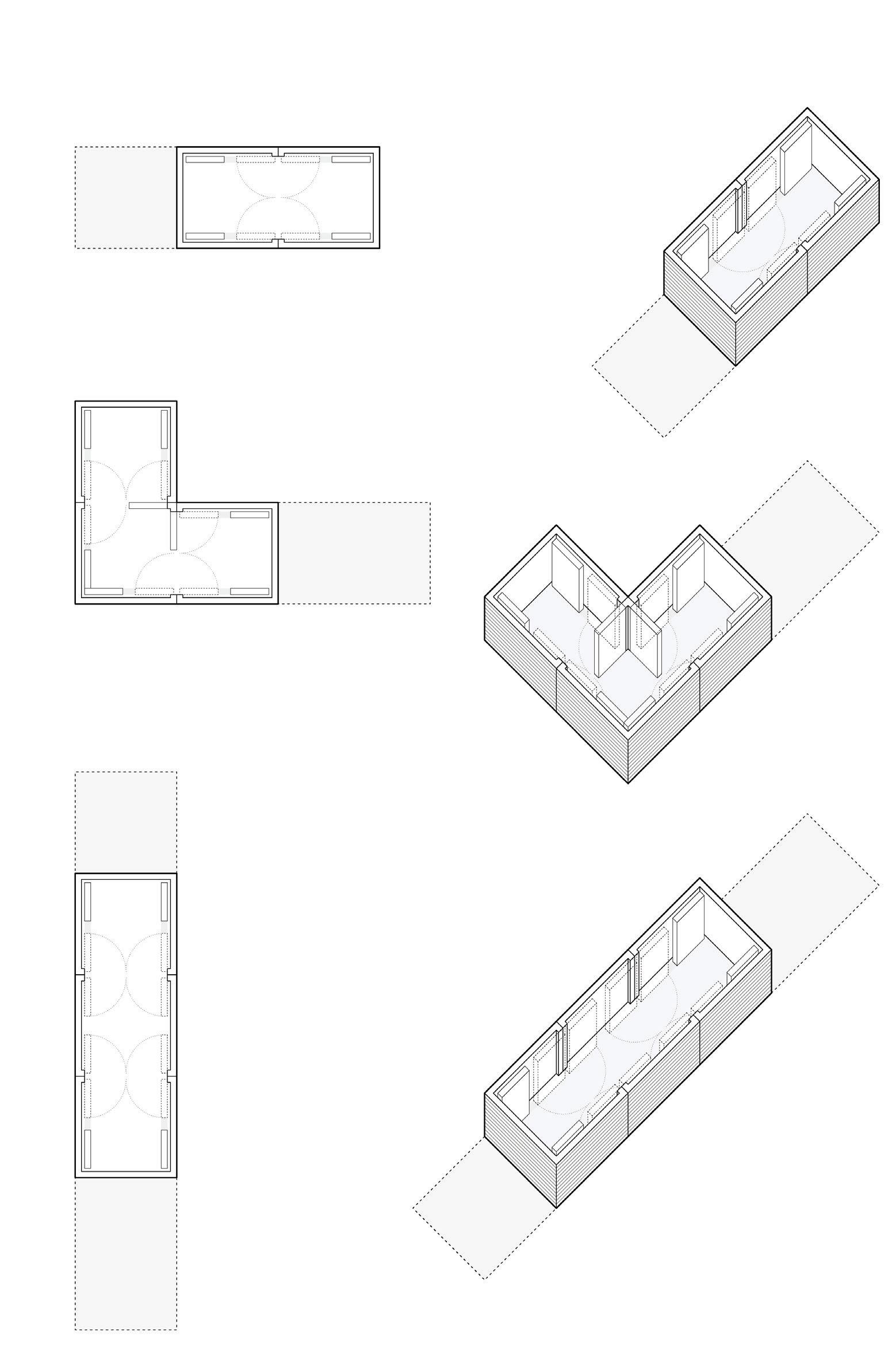

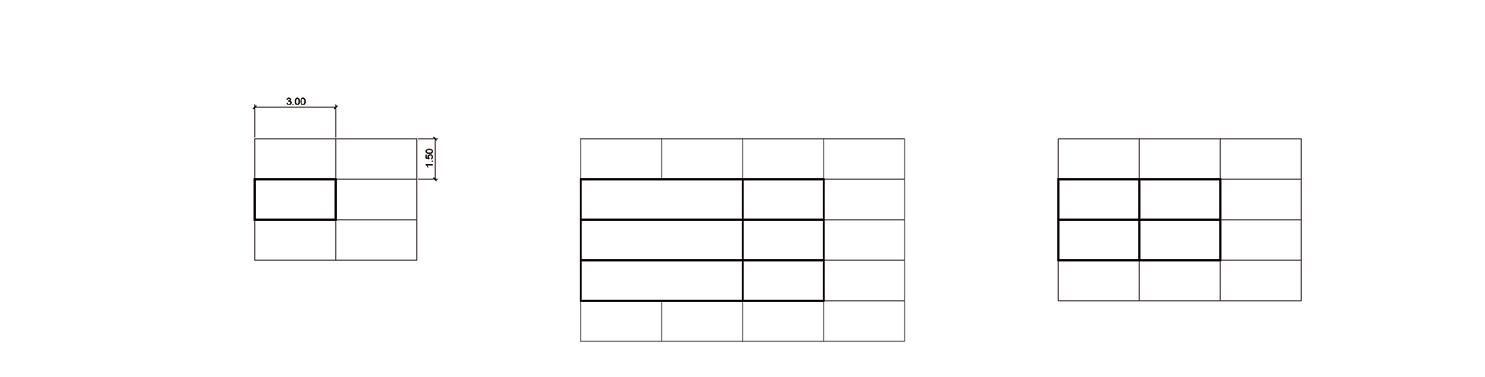

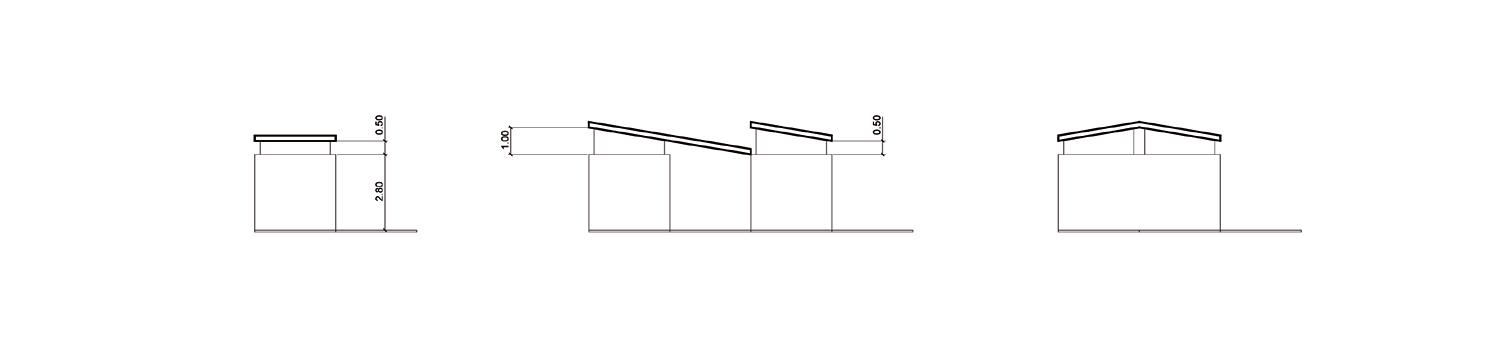

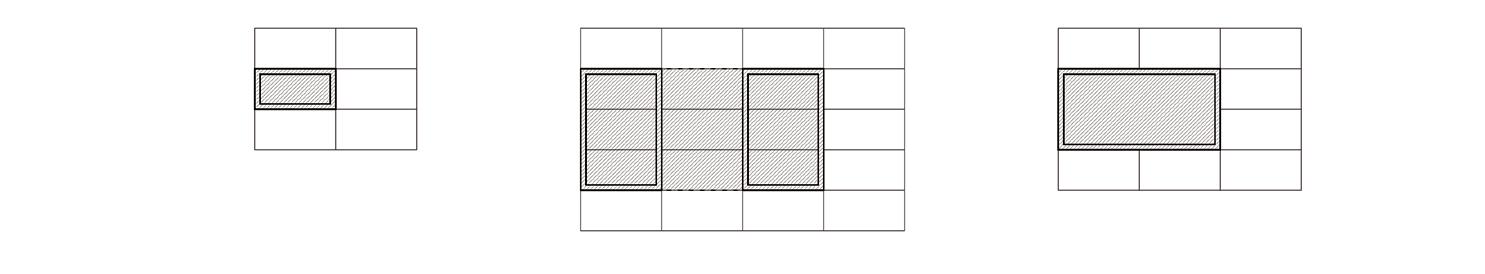

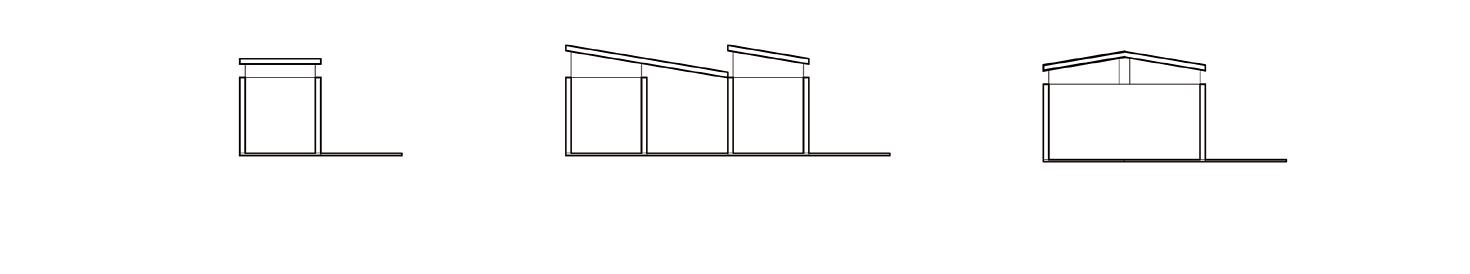

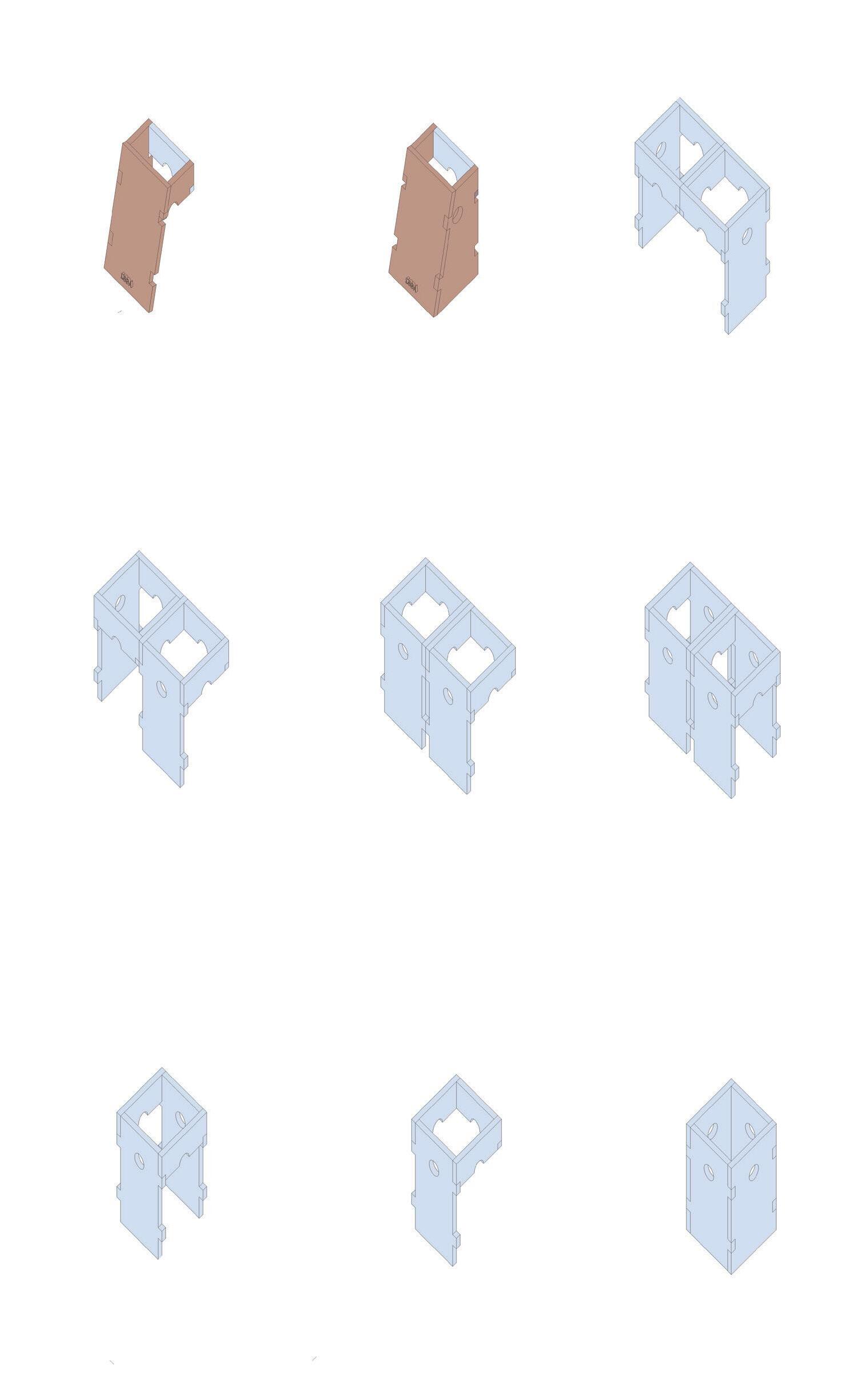

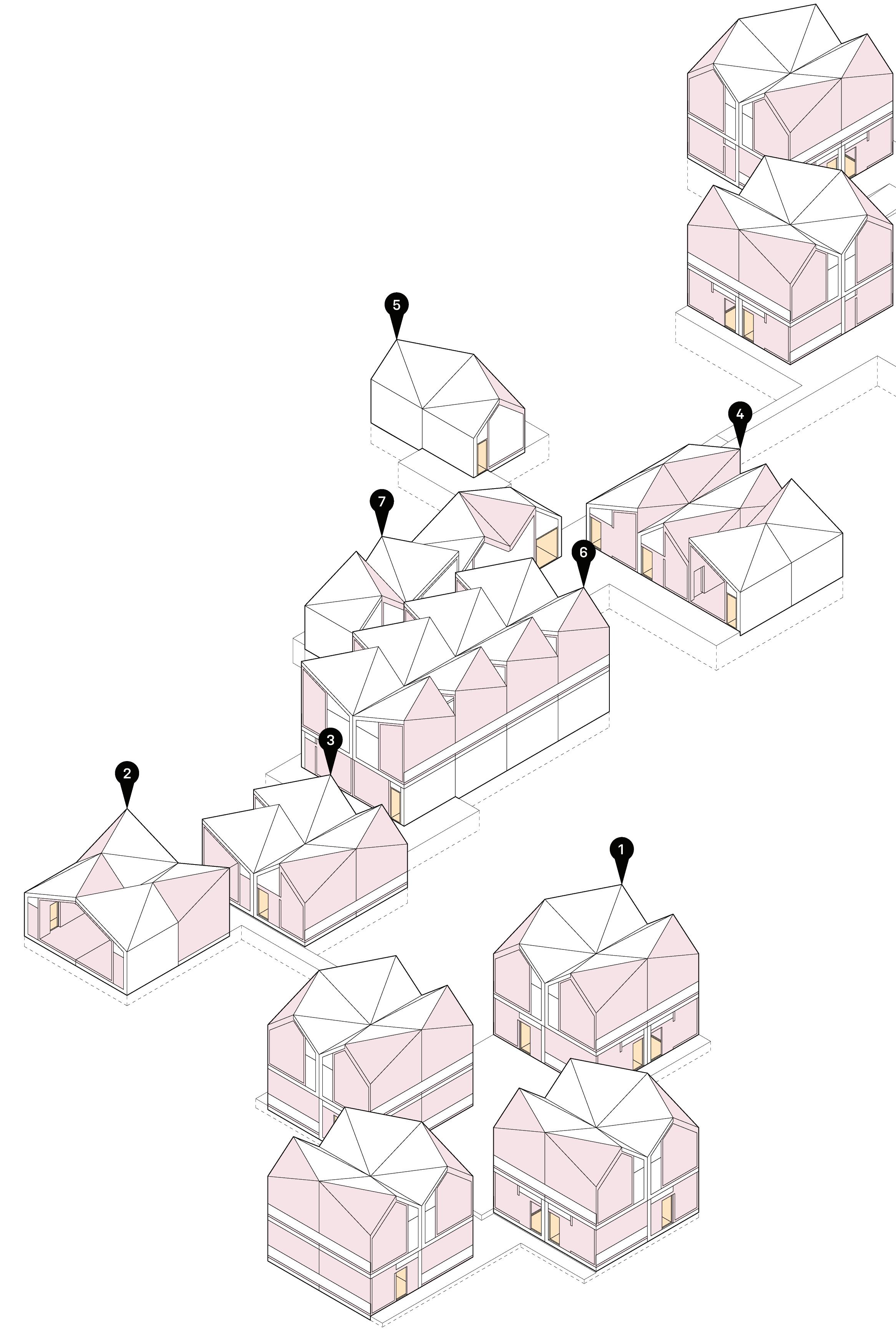

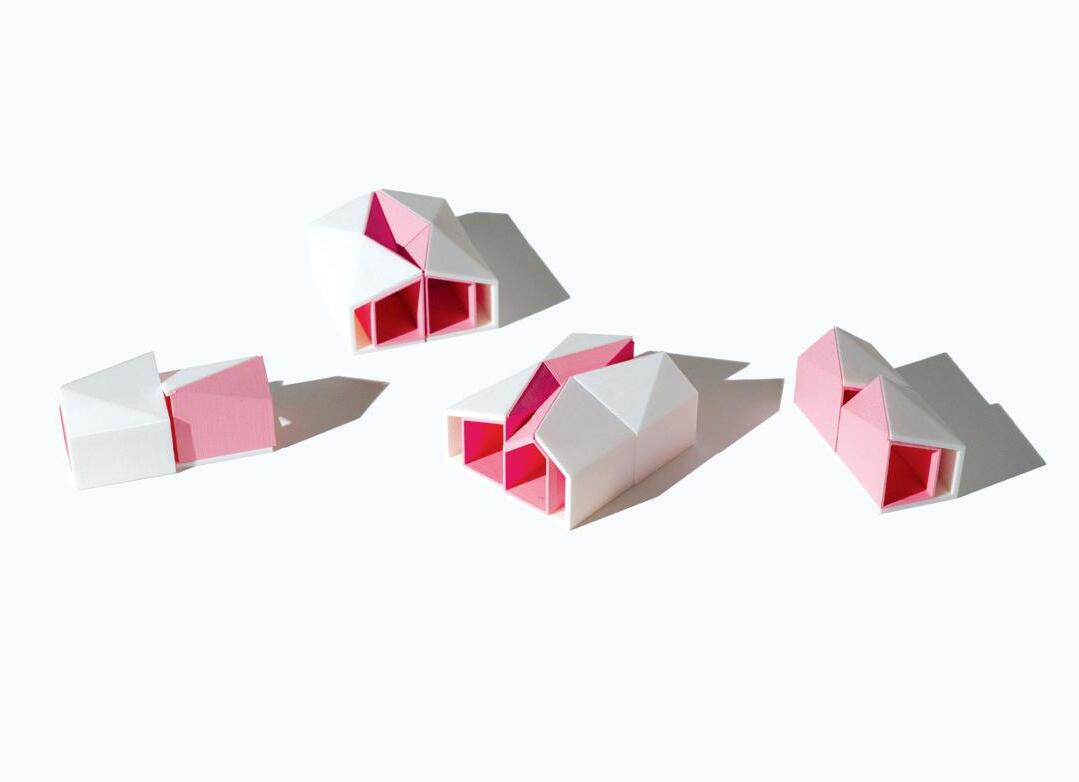

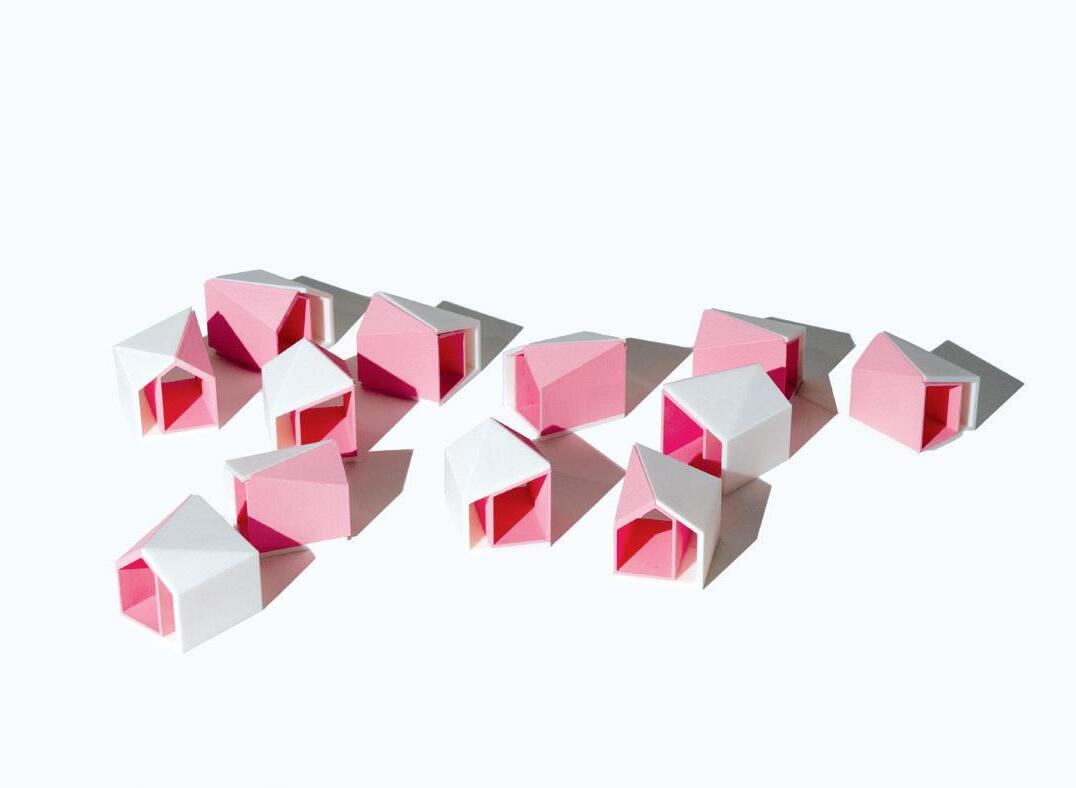

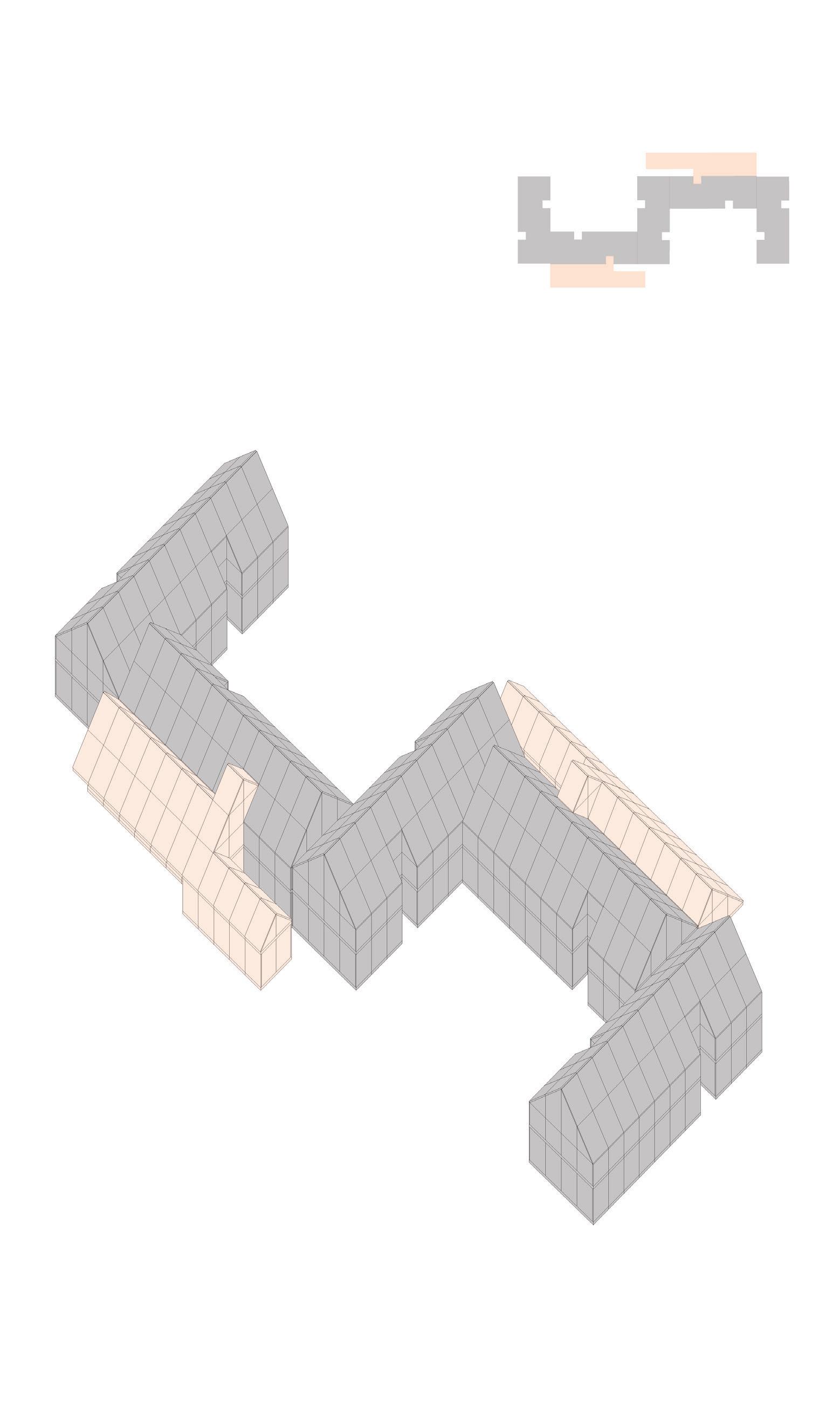

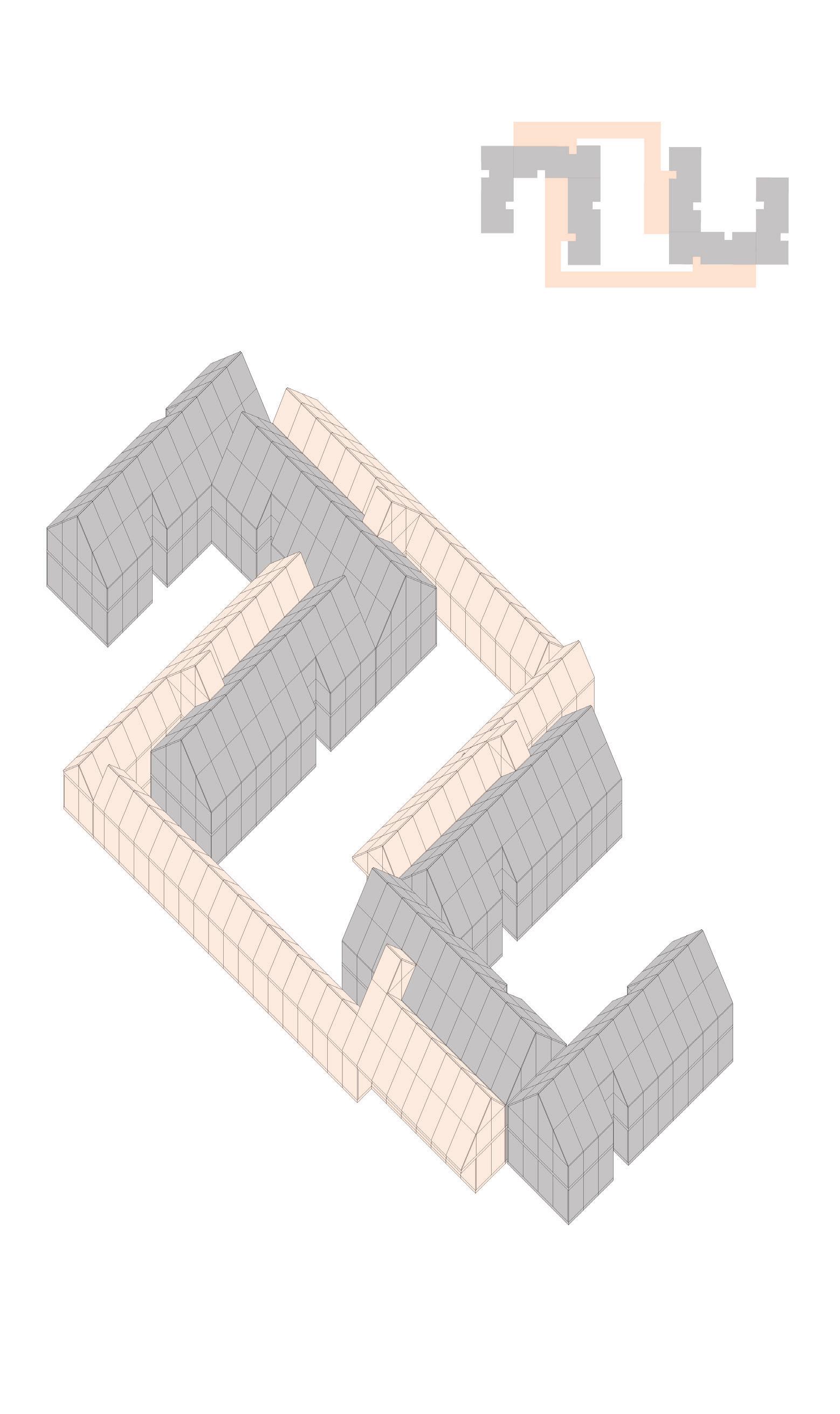

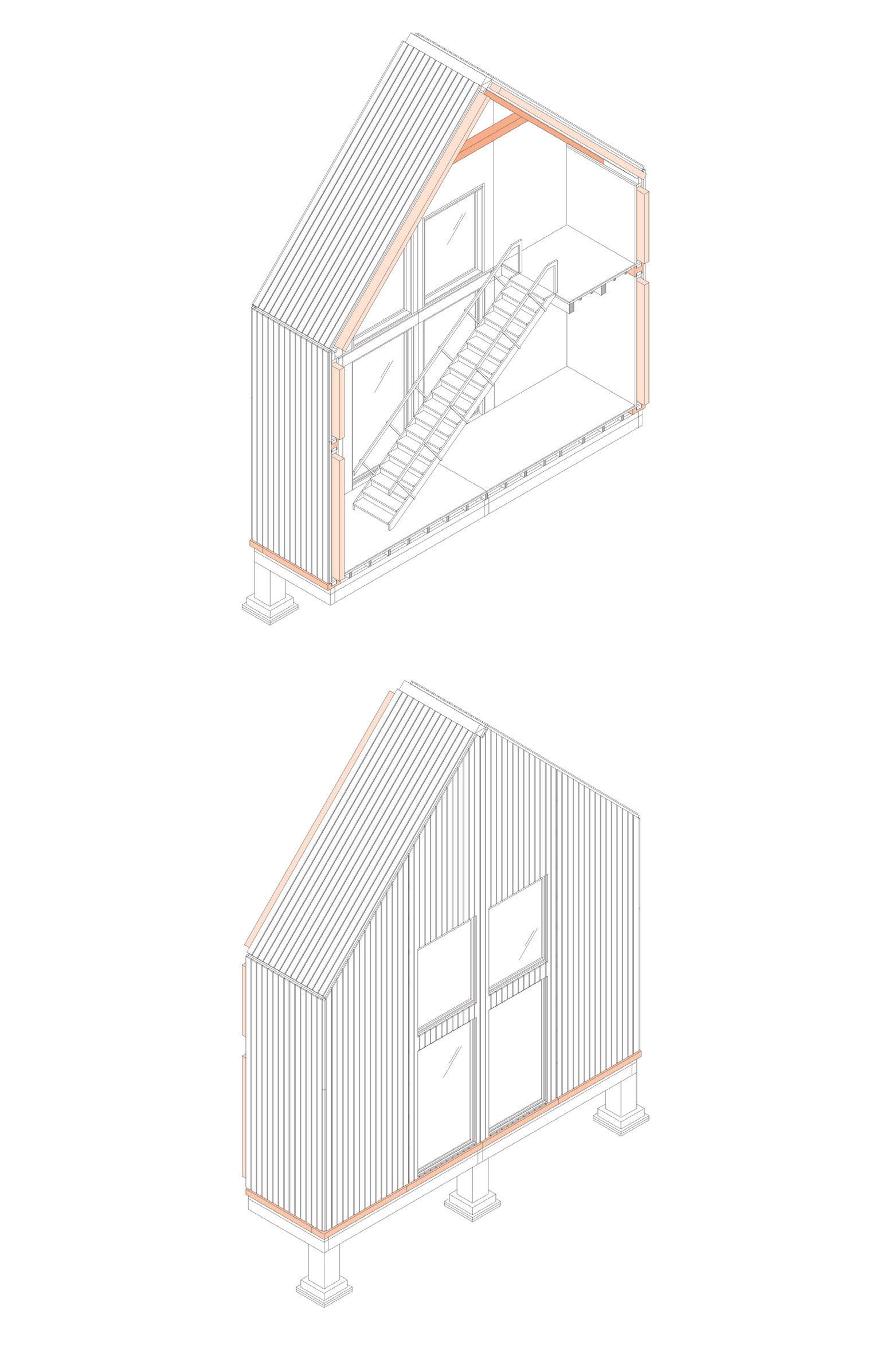

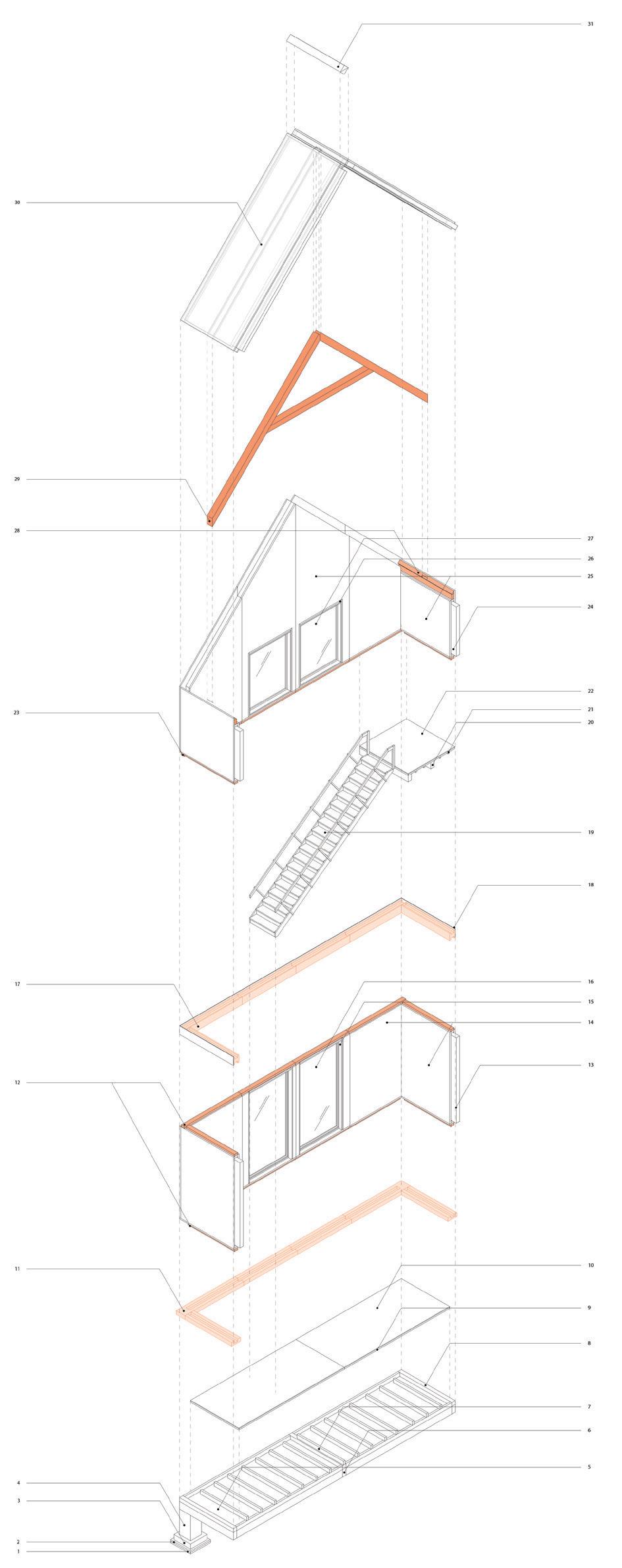

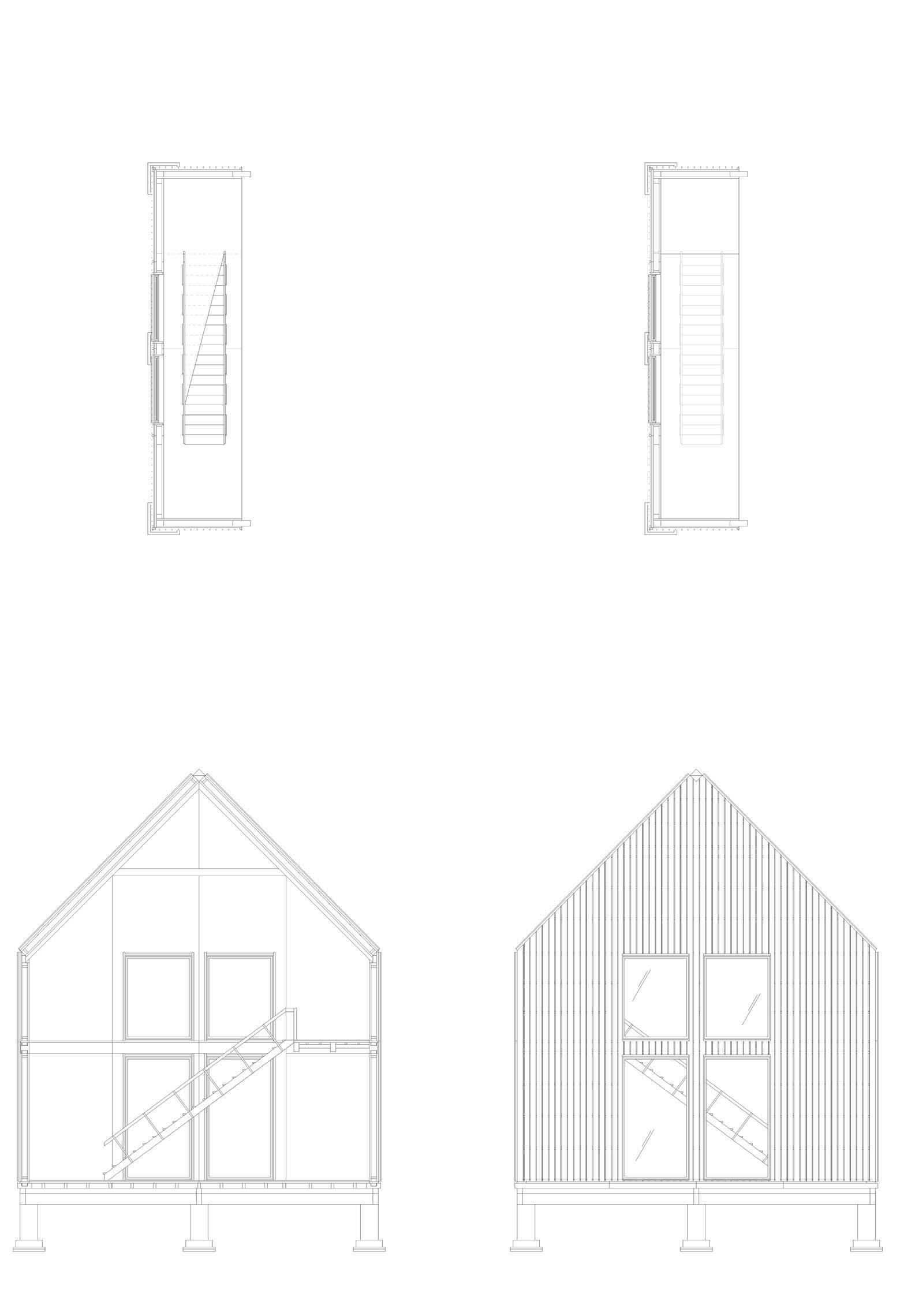

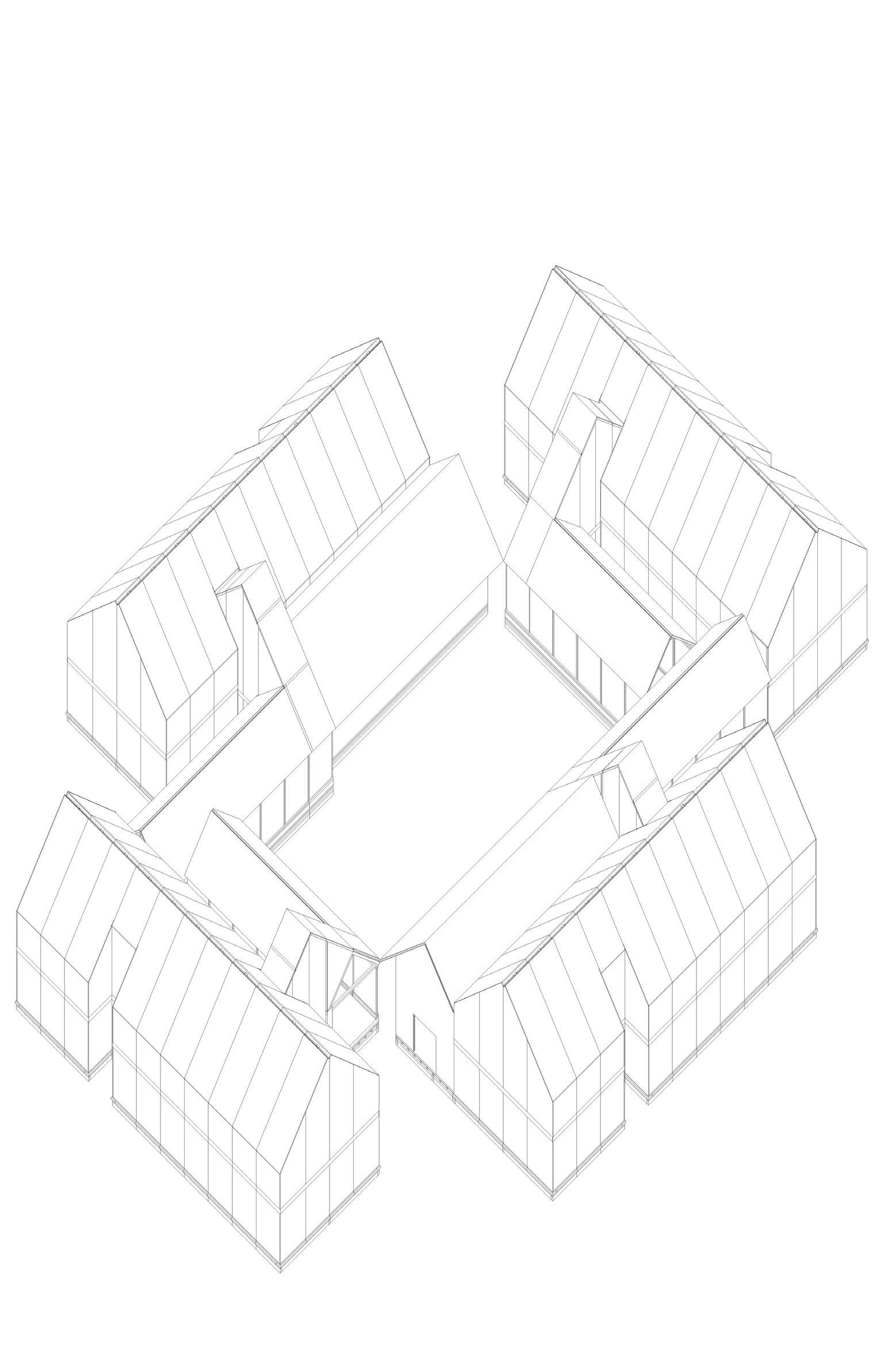

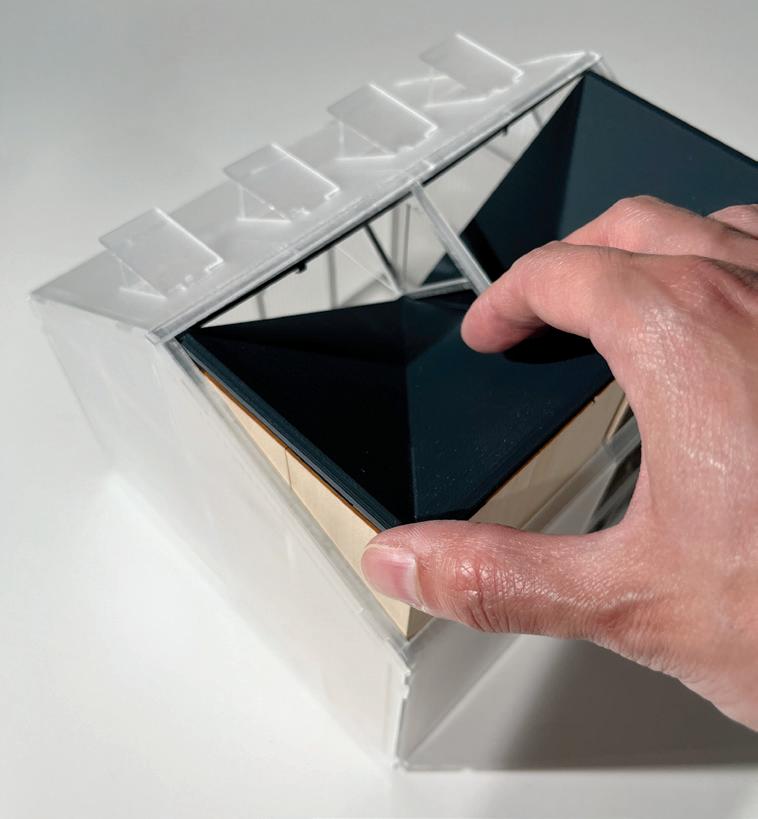

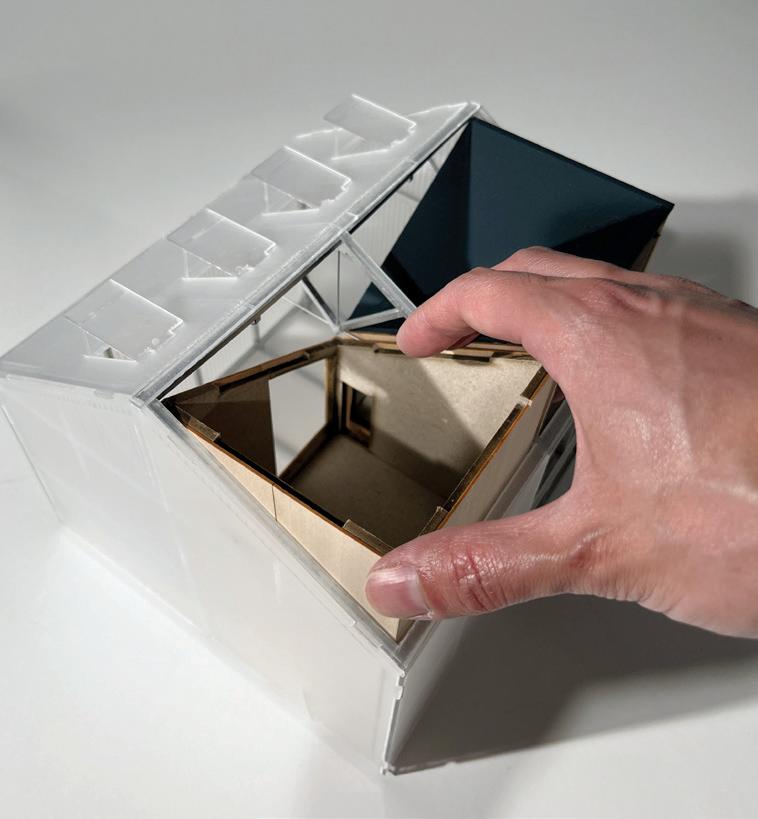

The primary challenge of the studio brief lies in reconciling the simultaneity of site-specificity and a site-less attitude—an approach demanded by its Japanese context while operating as an OSM project. It calls for architecture that serves a collective in an imagined future mode of work, departing from the small modular cabins typically associated with OSM.

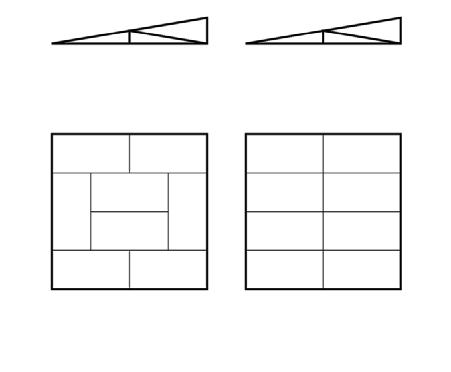

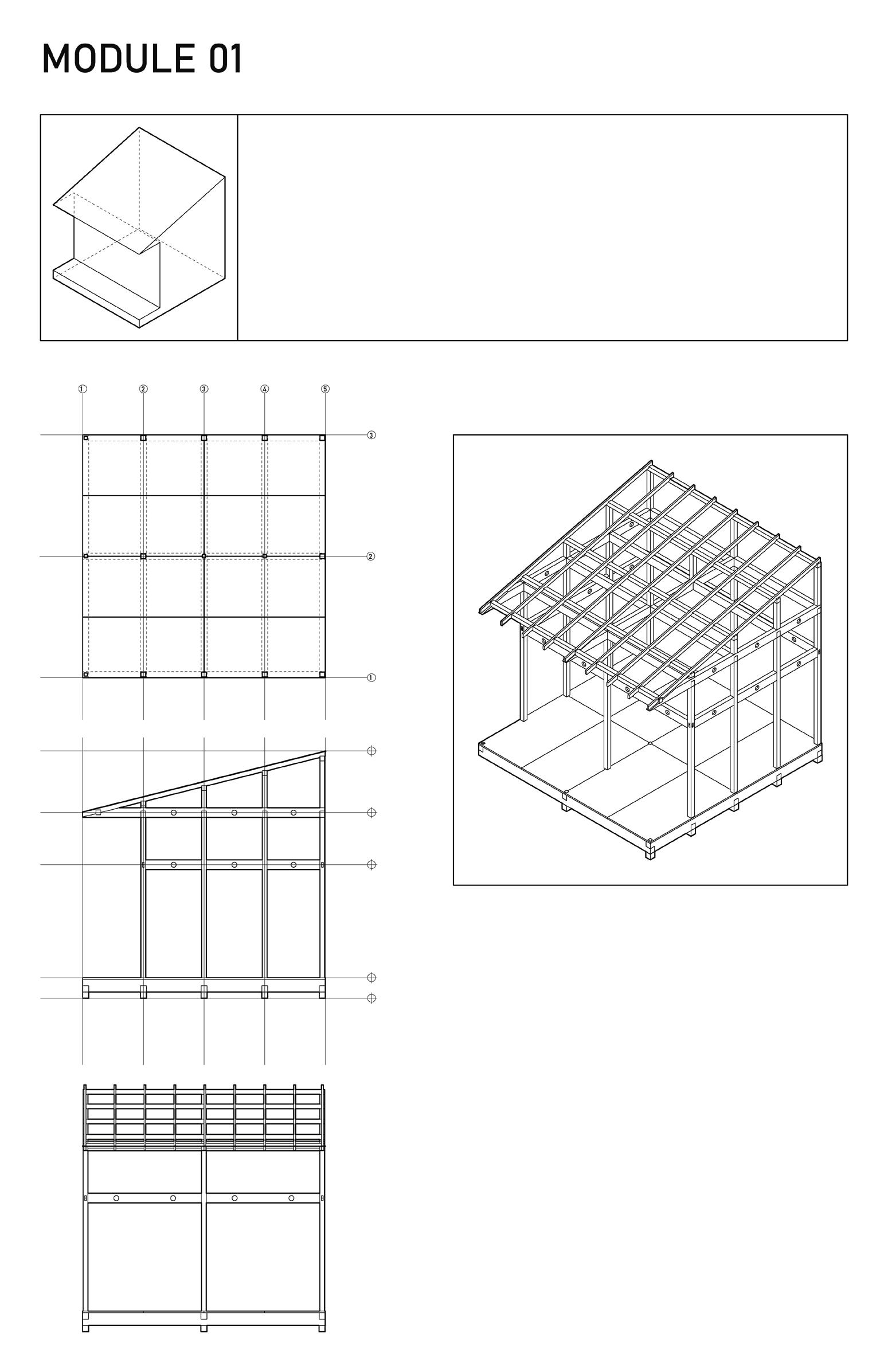

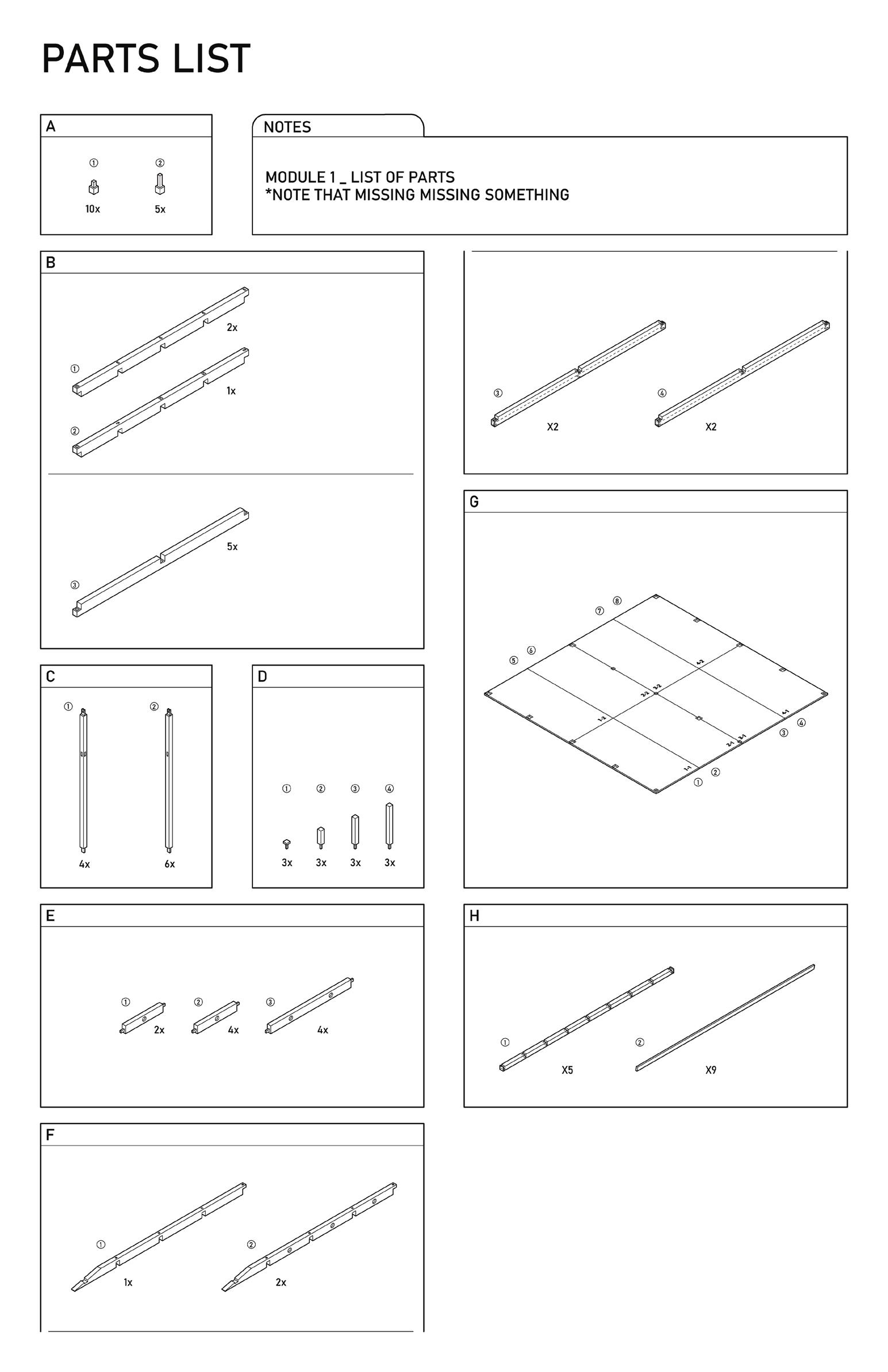

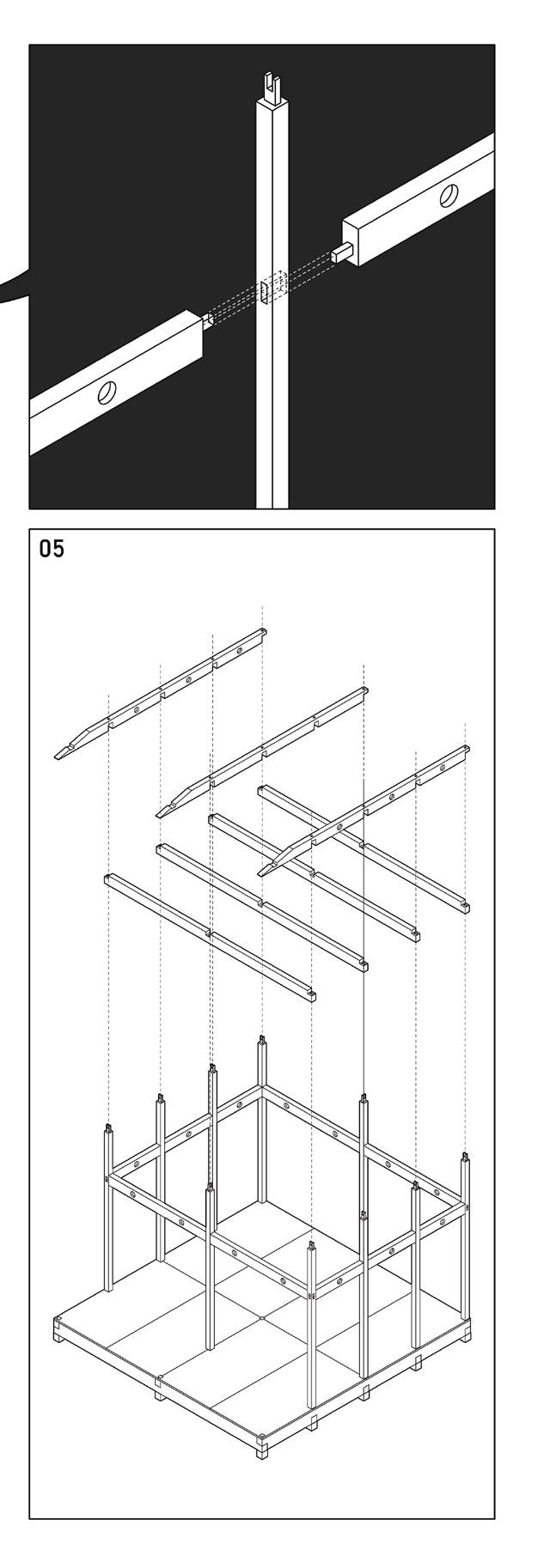

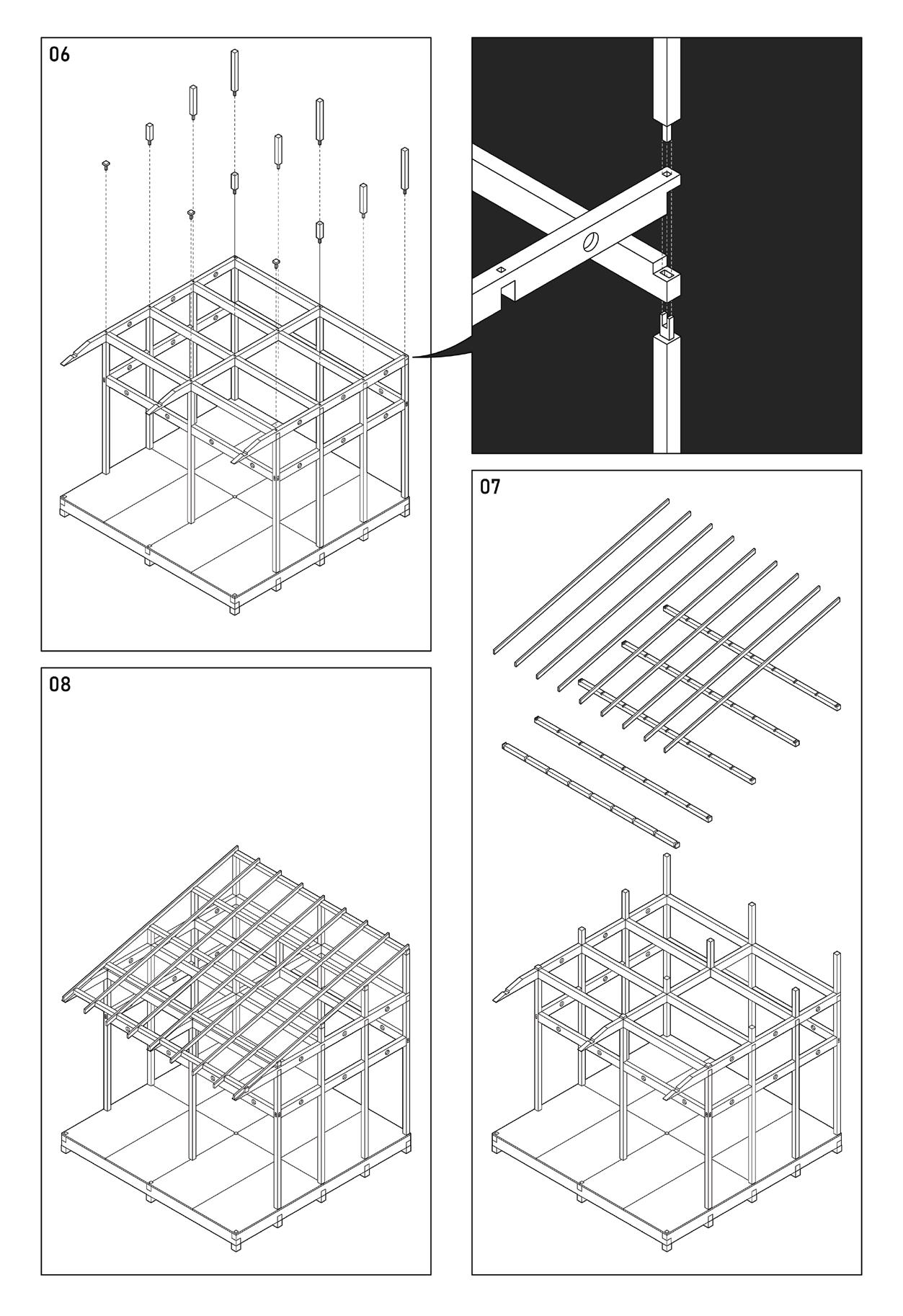

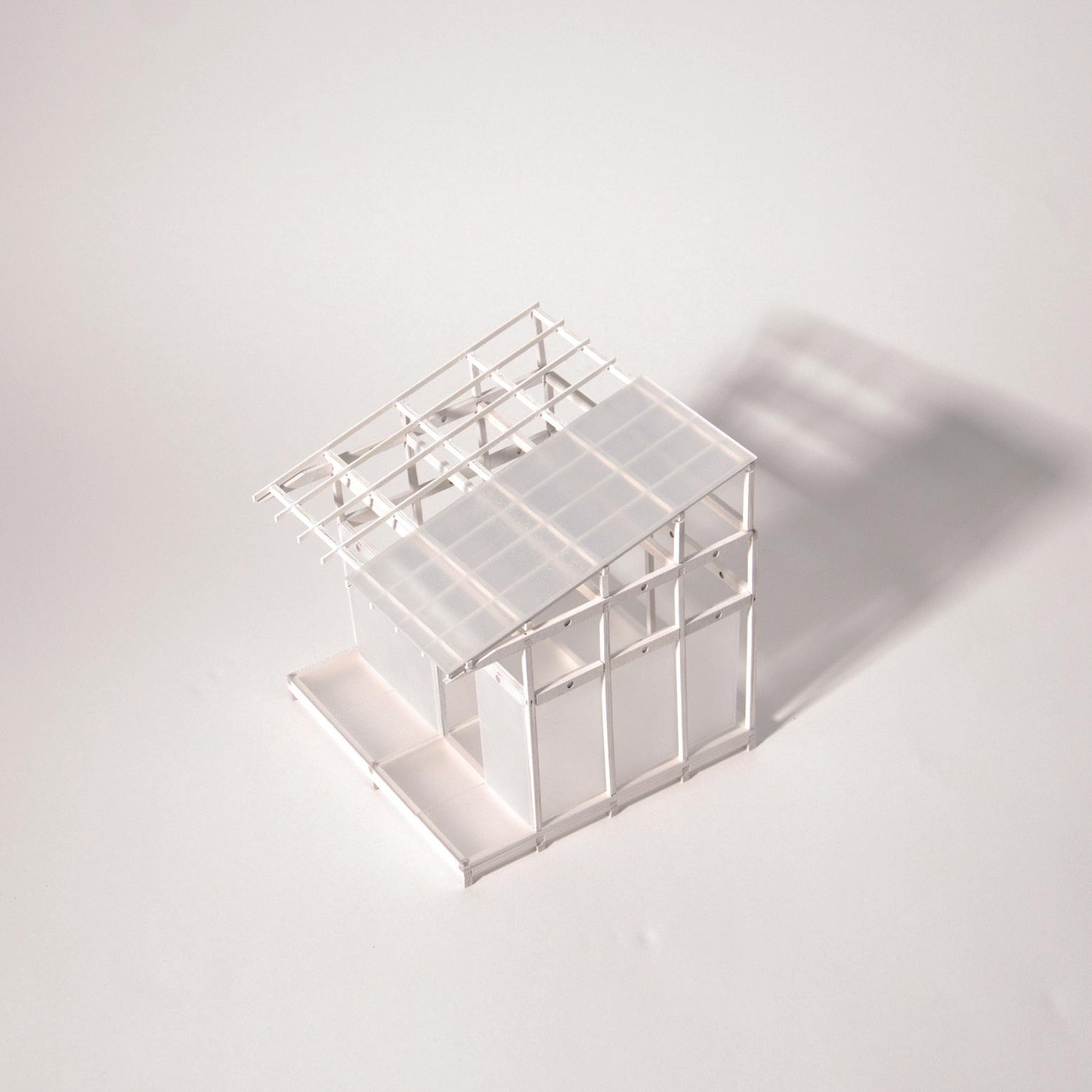

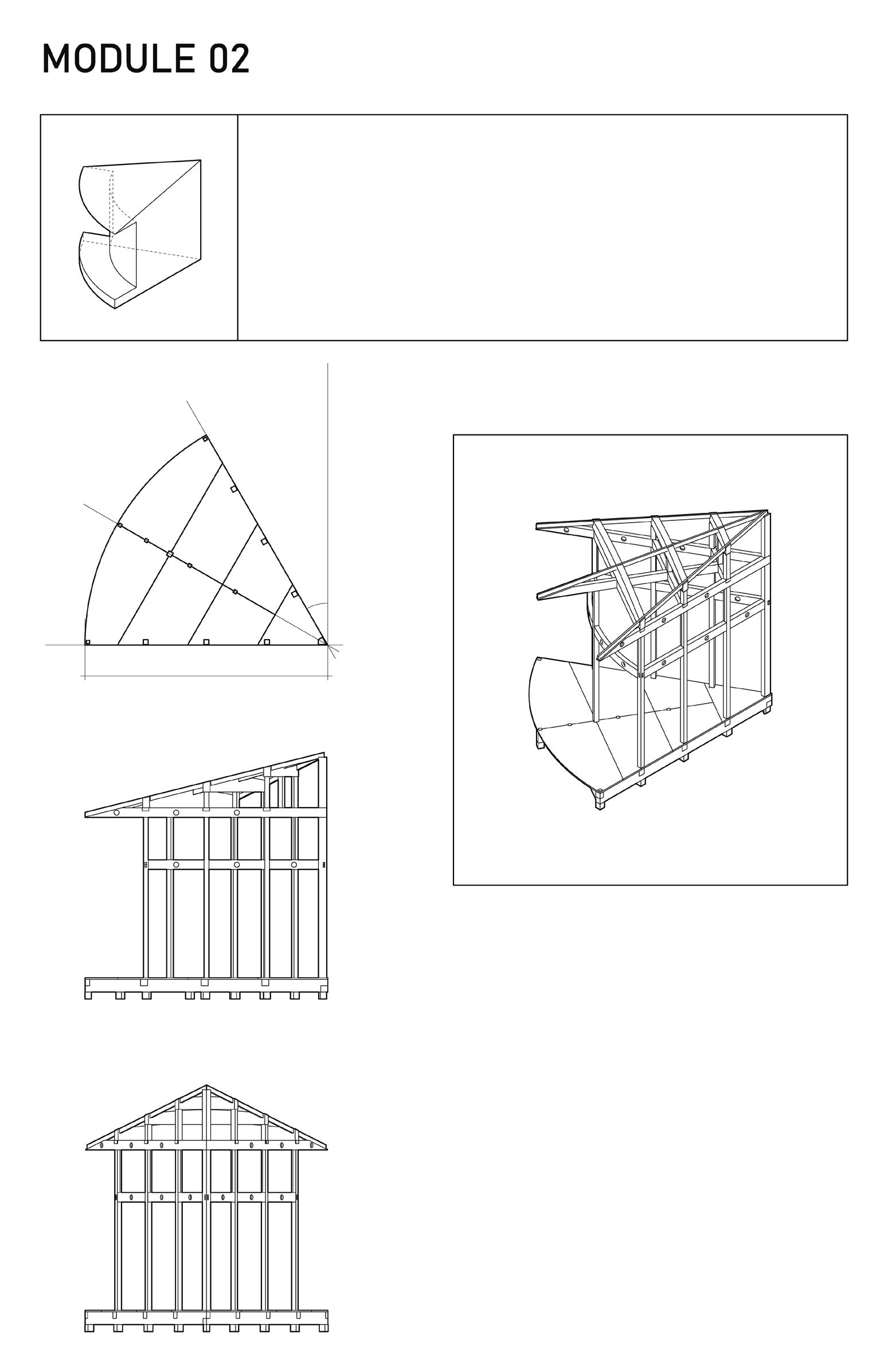

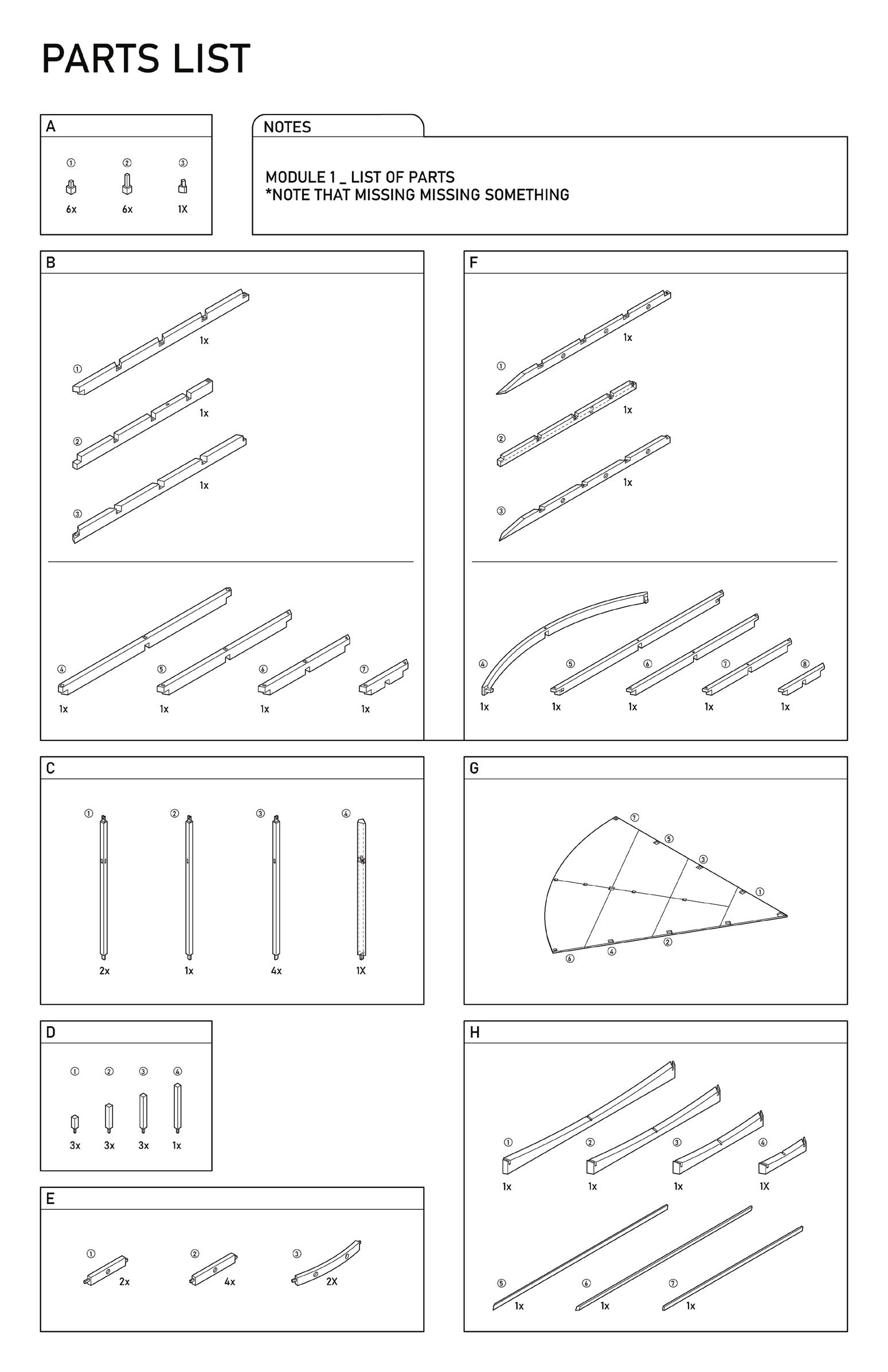

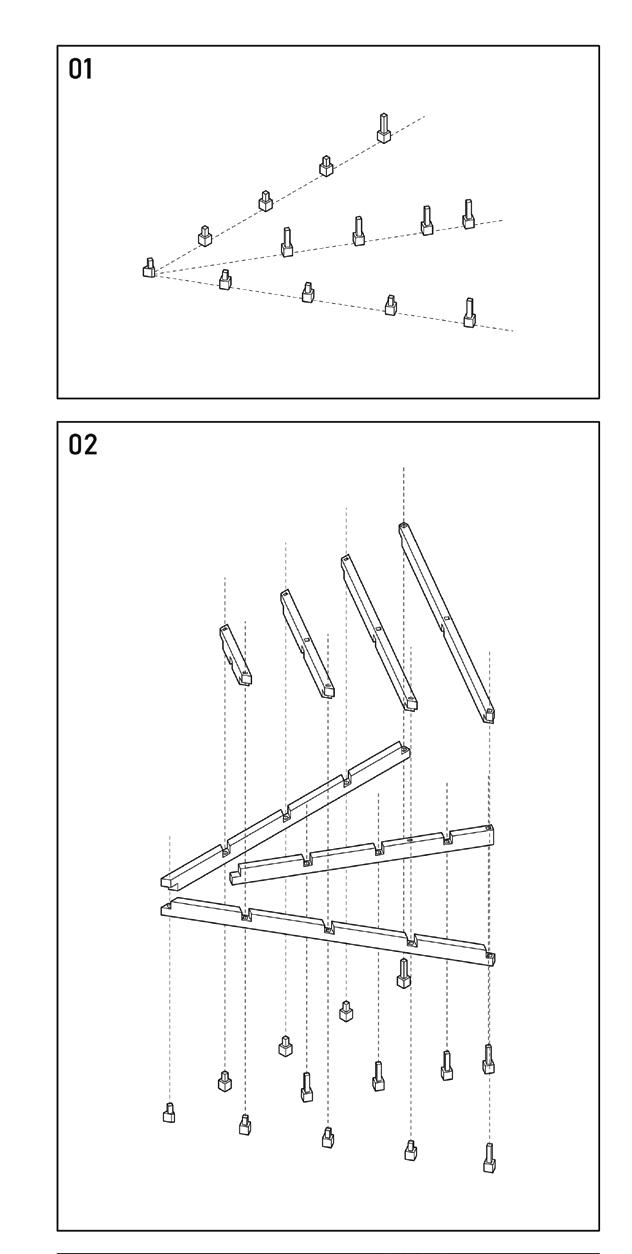

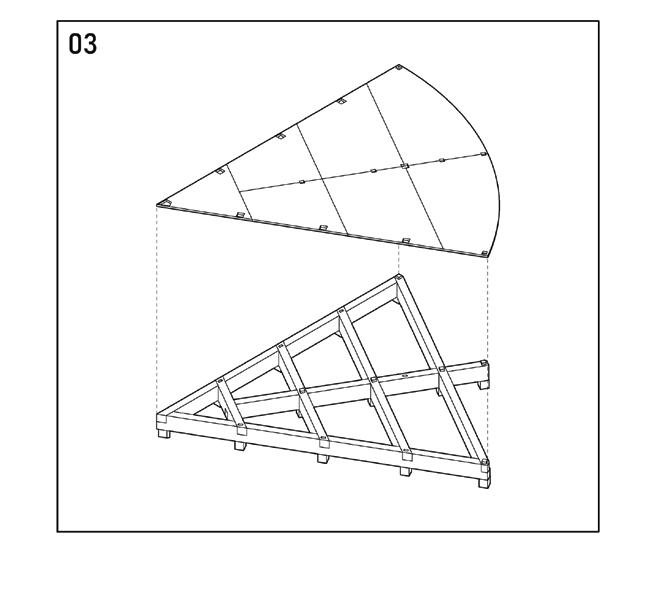

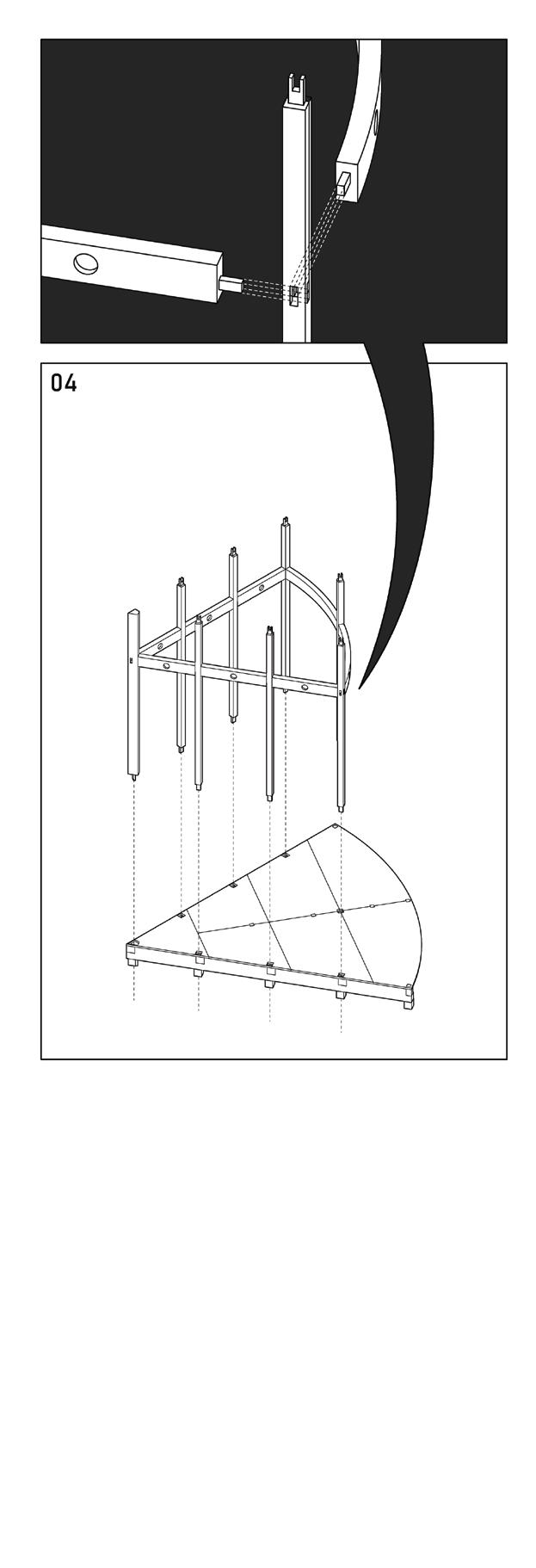

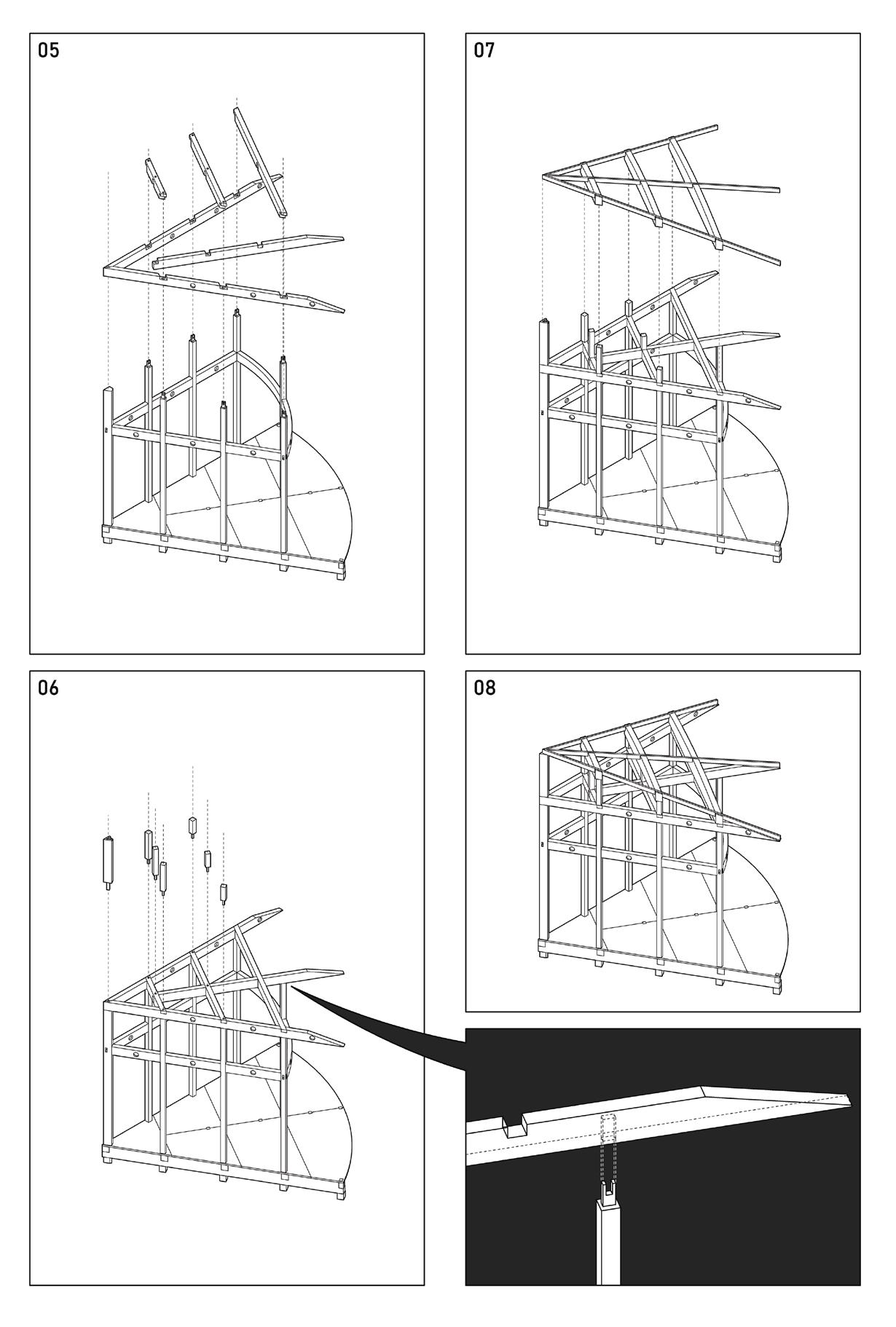

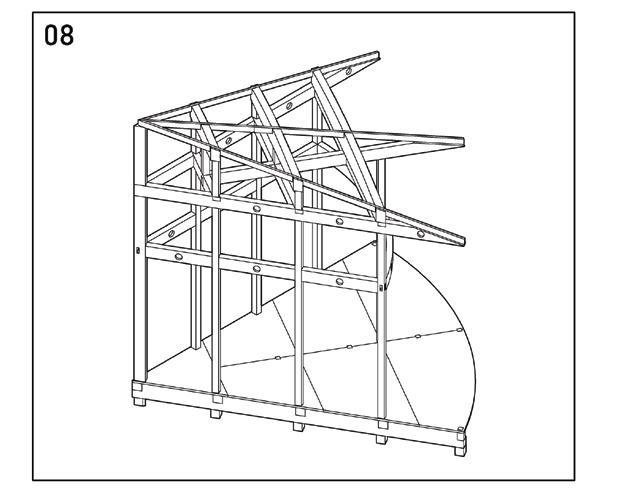

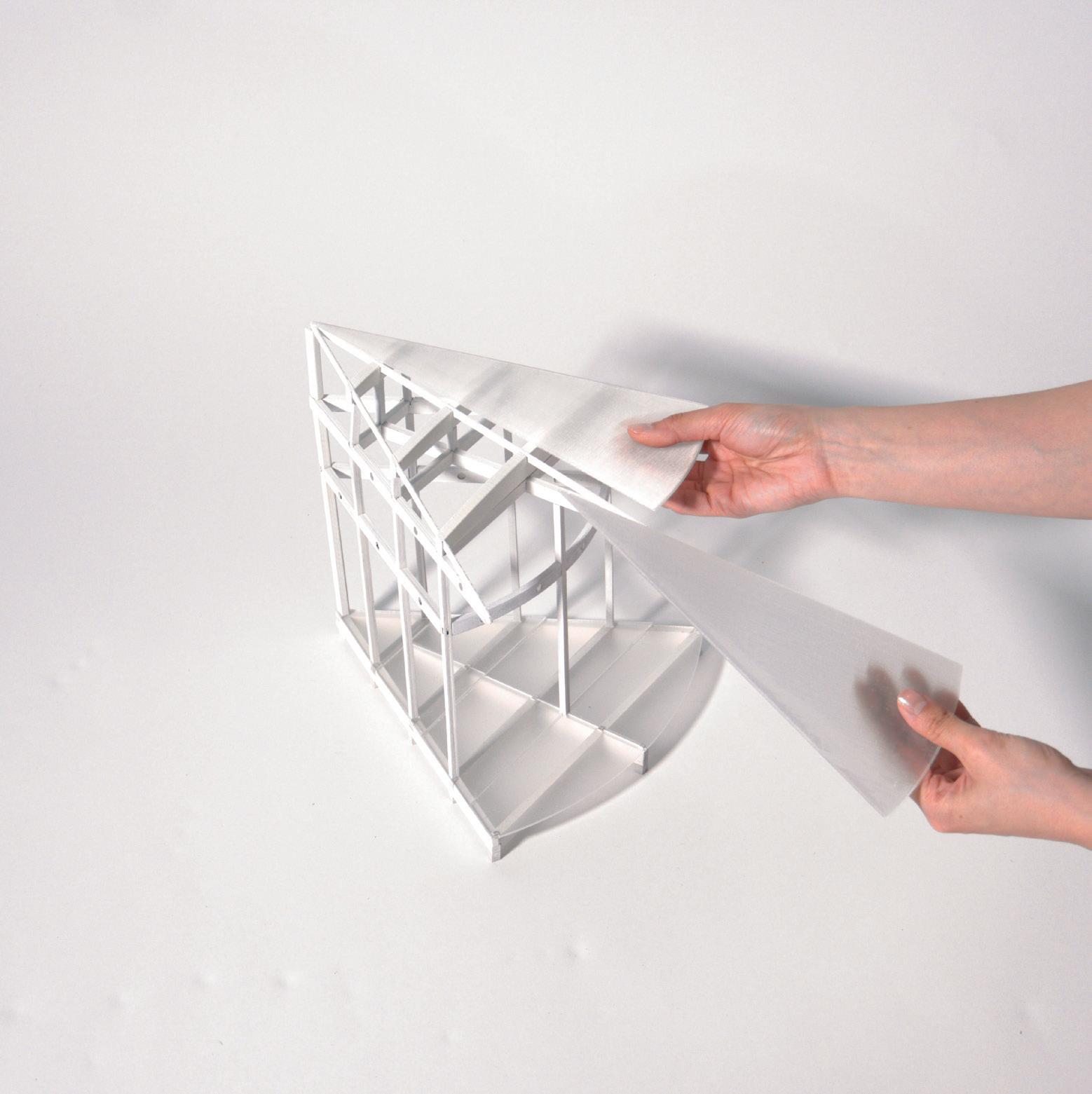

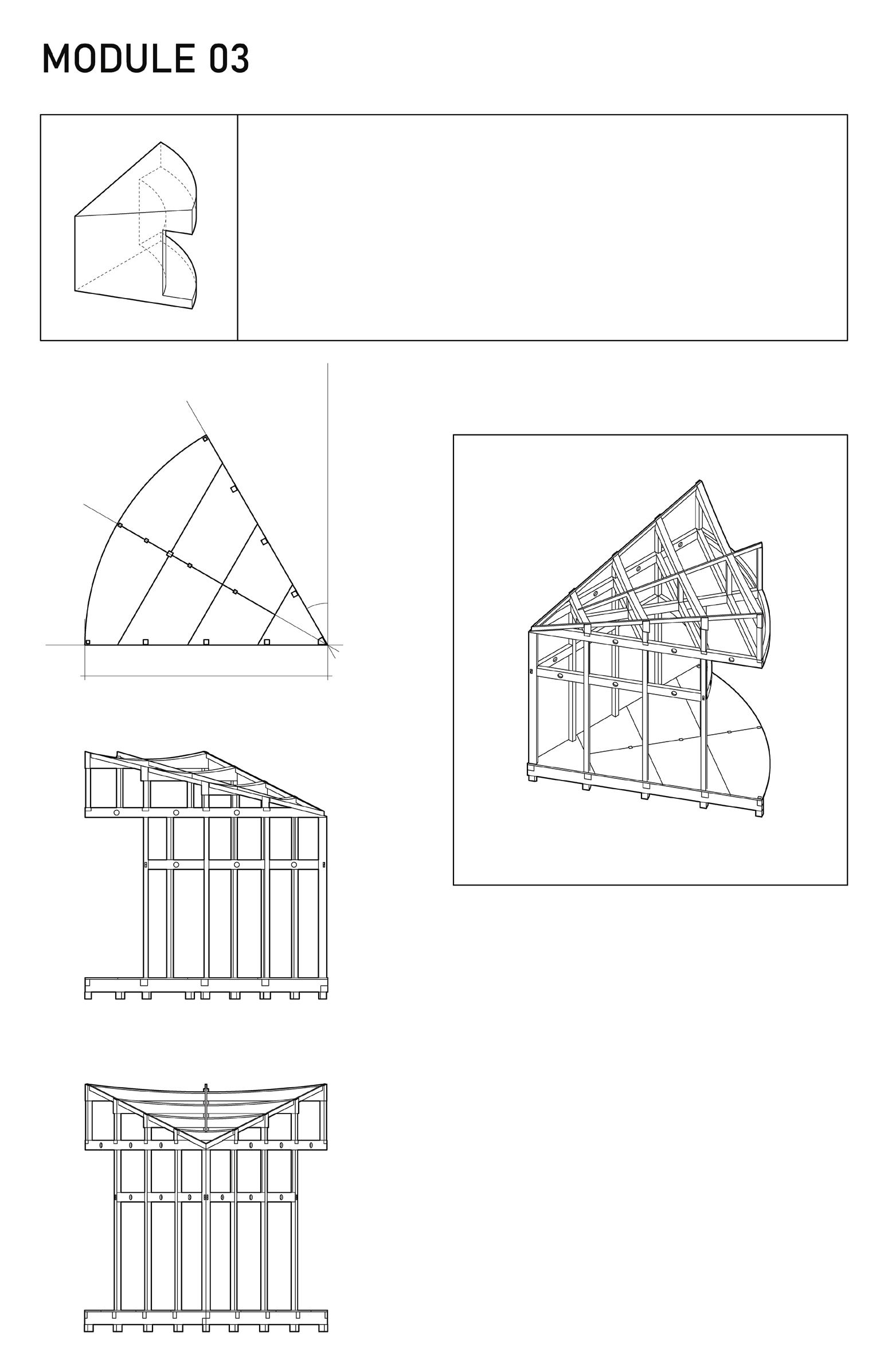

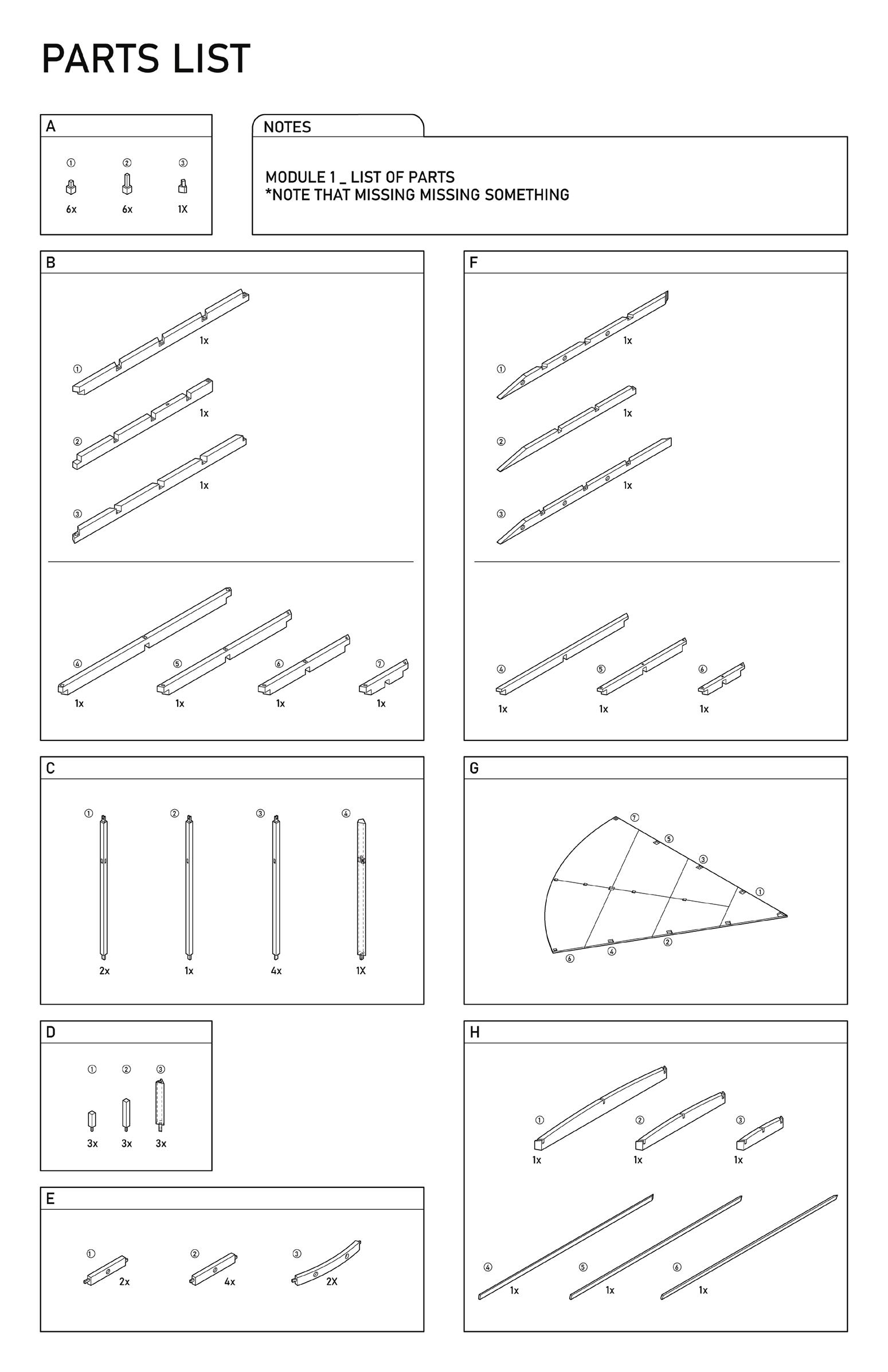

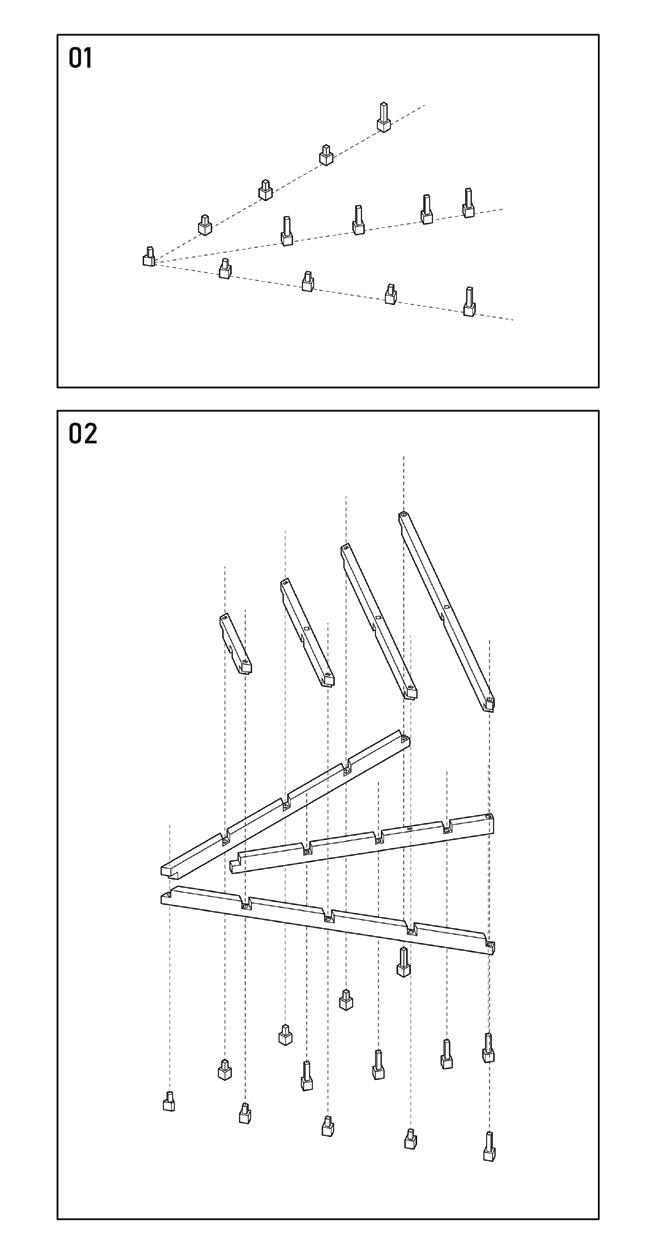

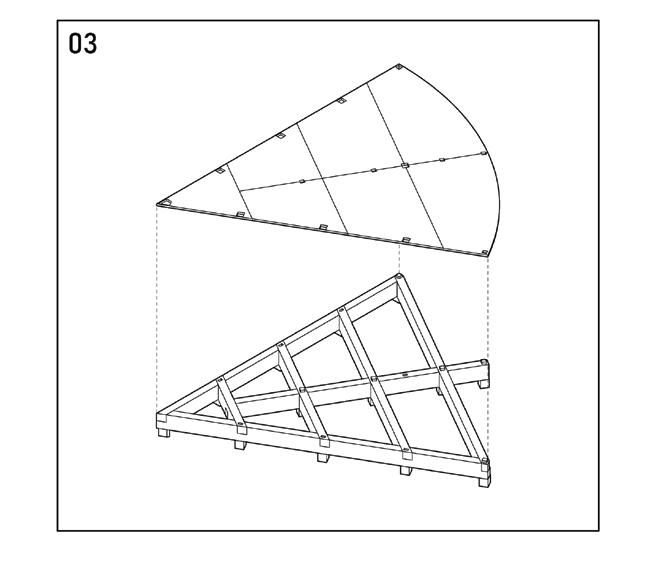

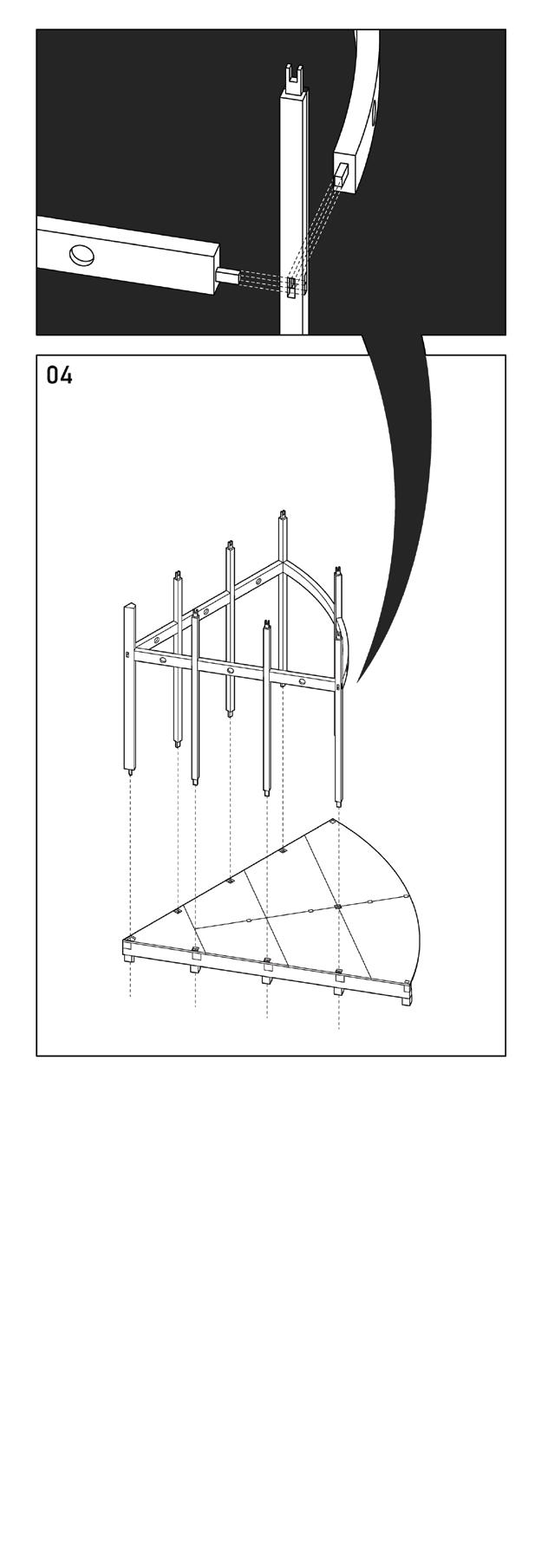

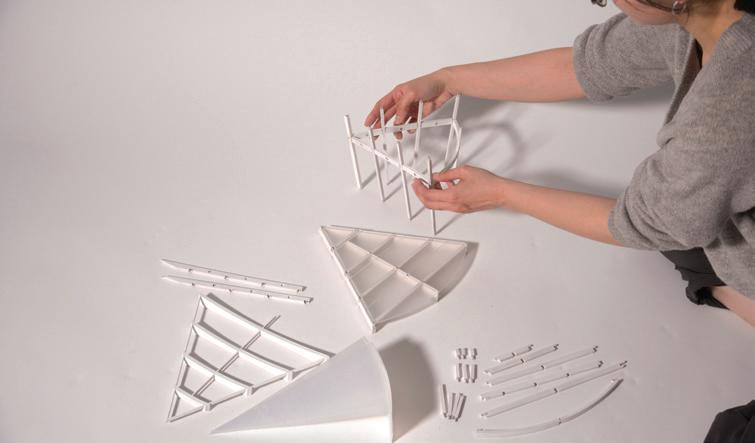

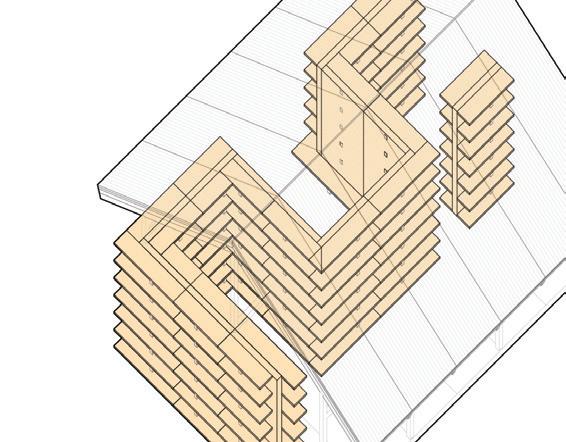

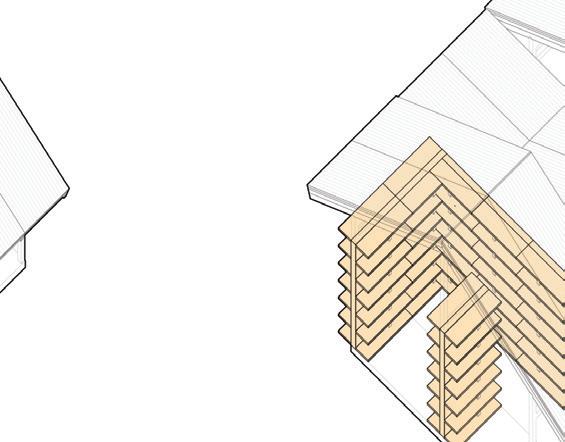

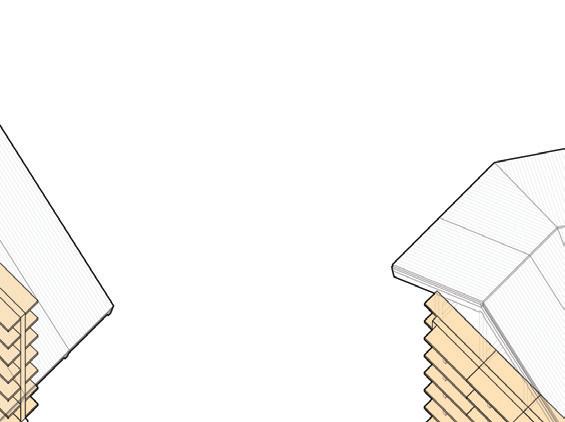

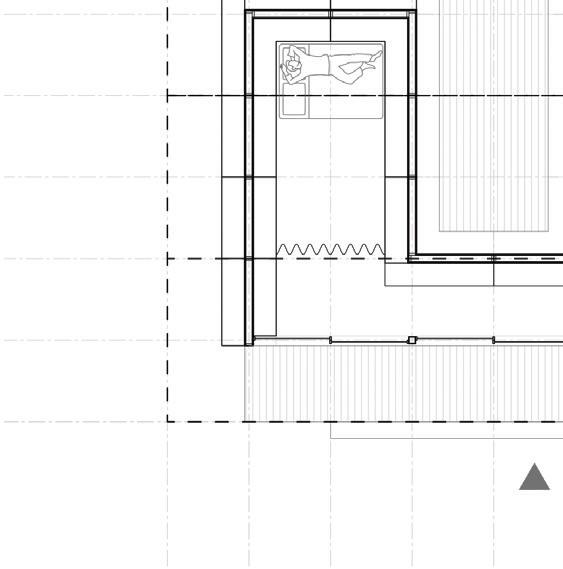

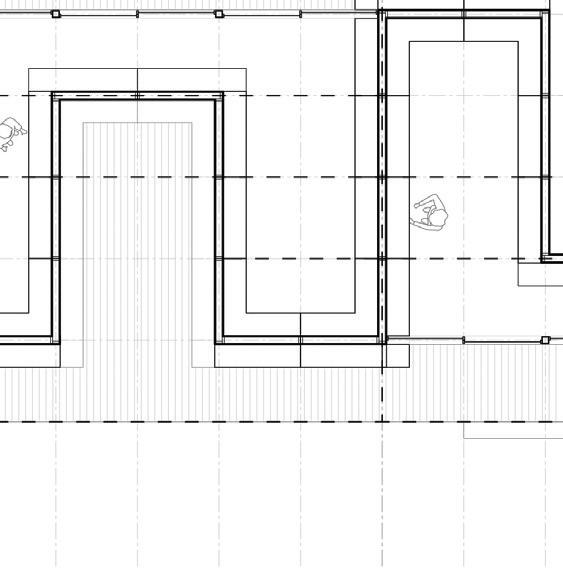

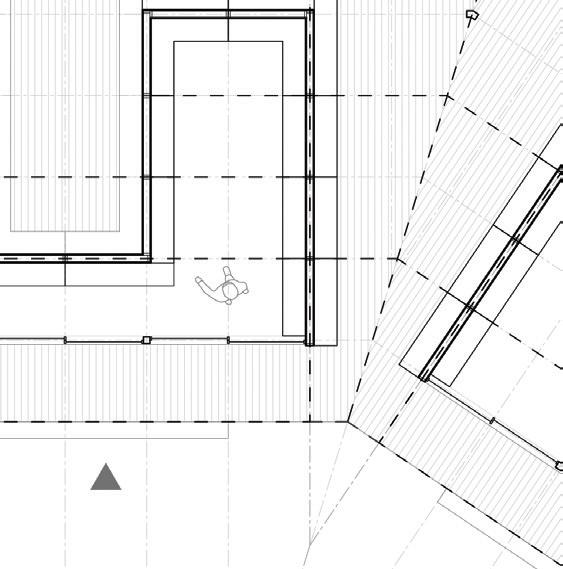

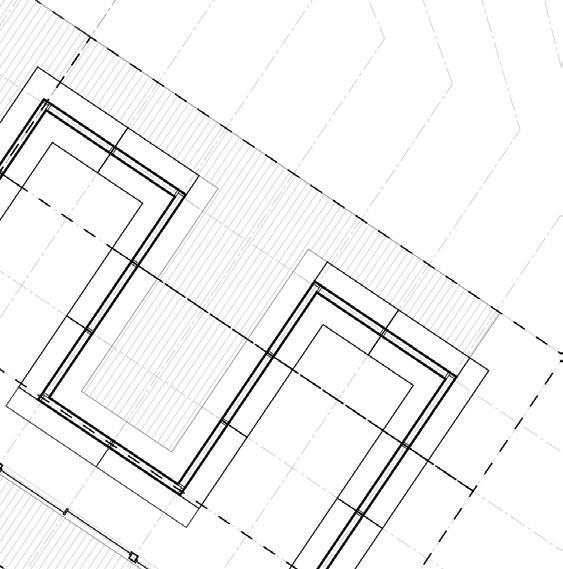

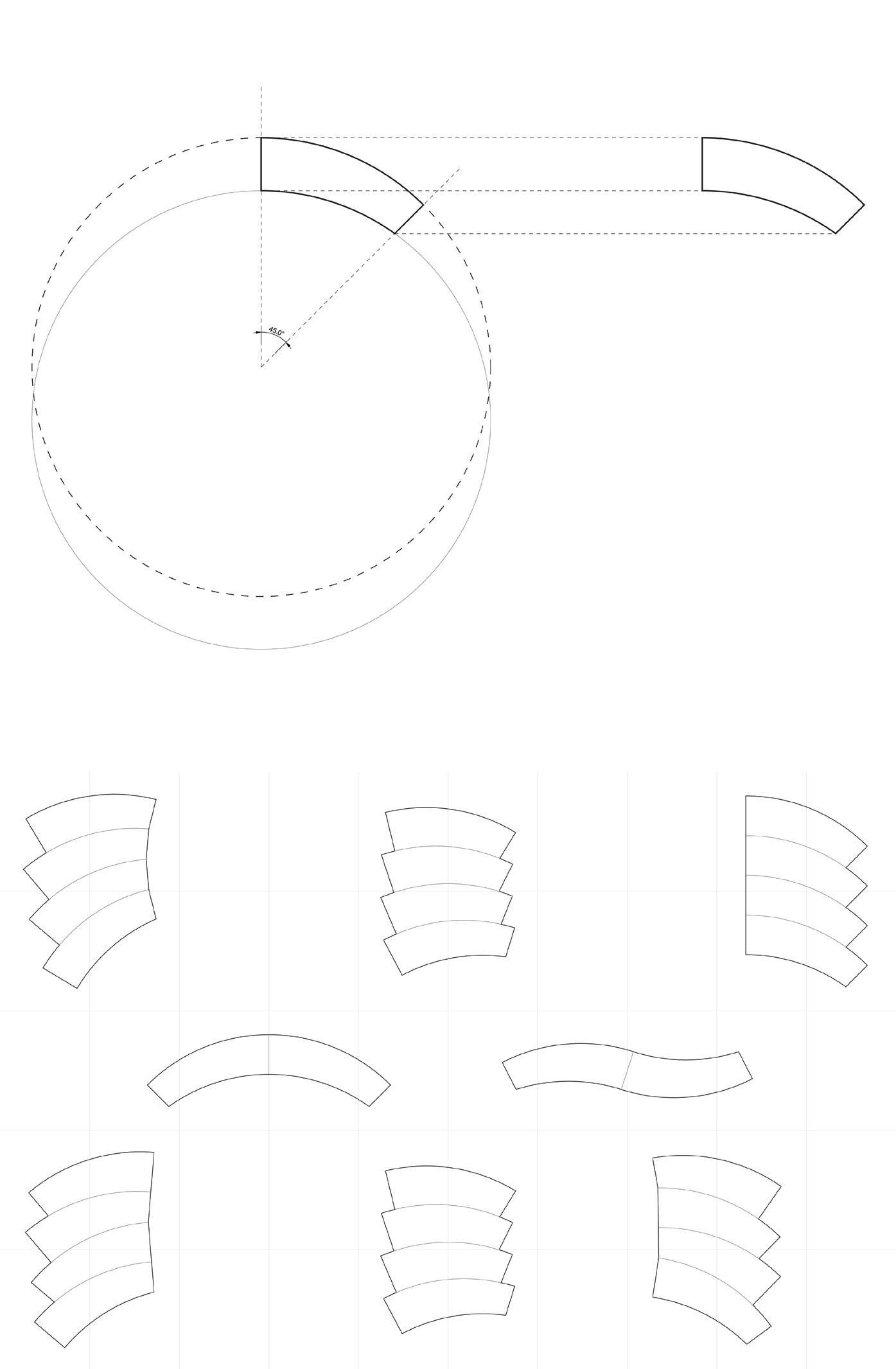

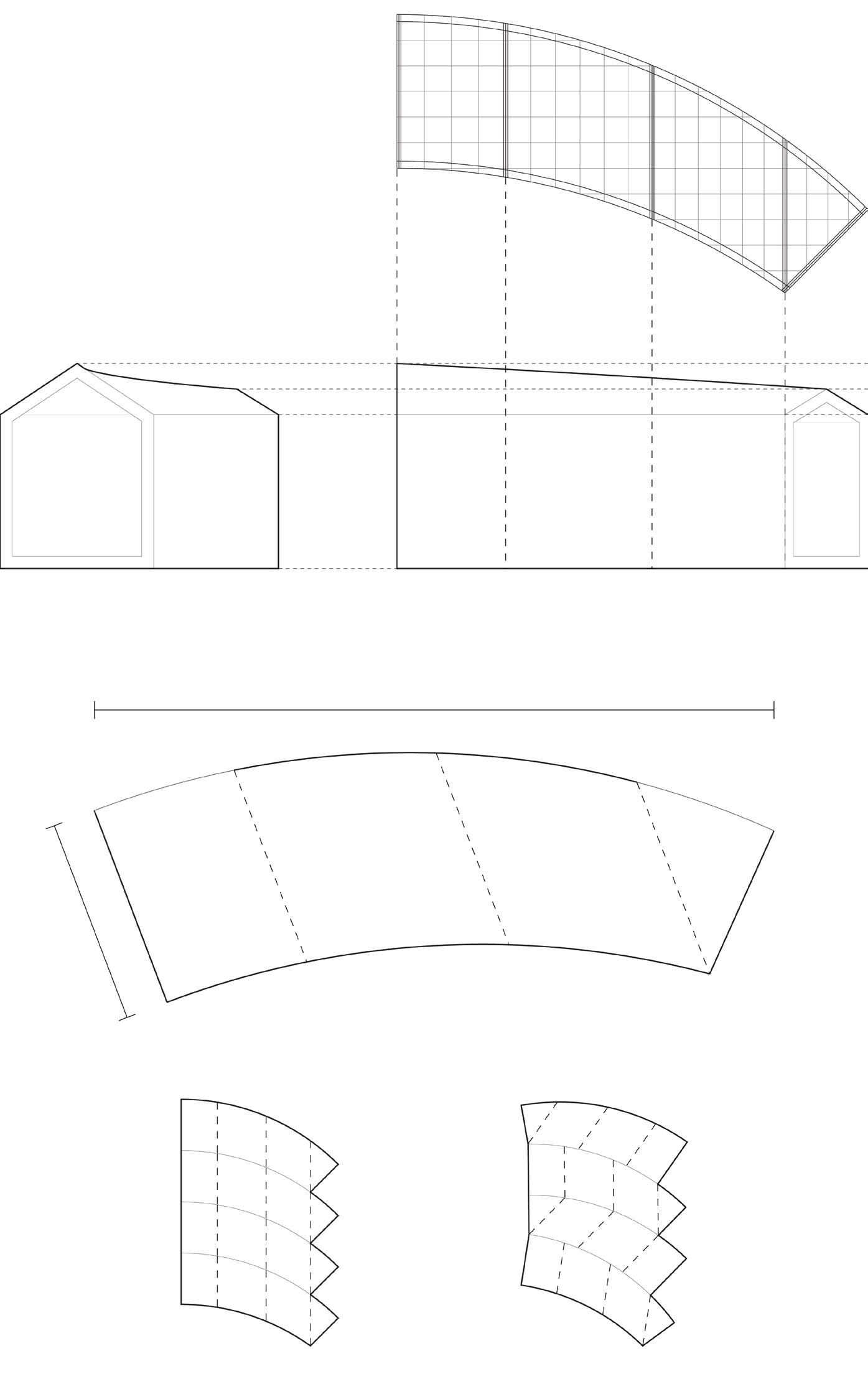

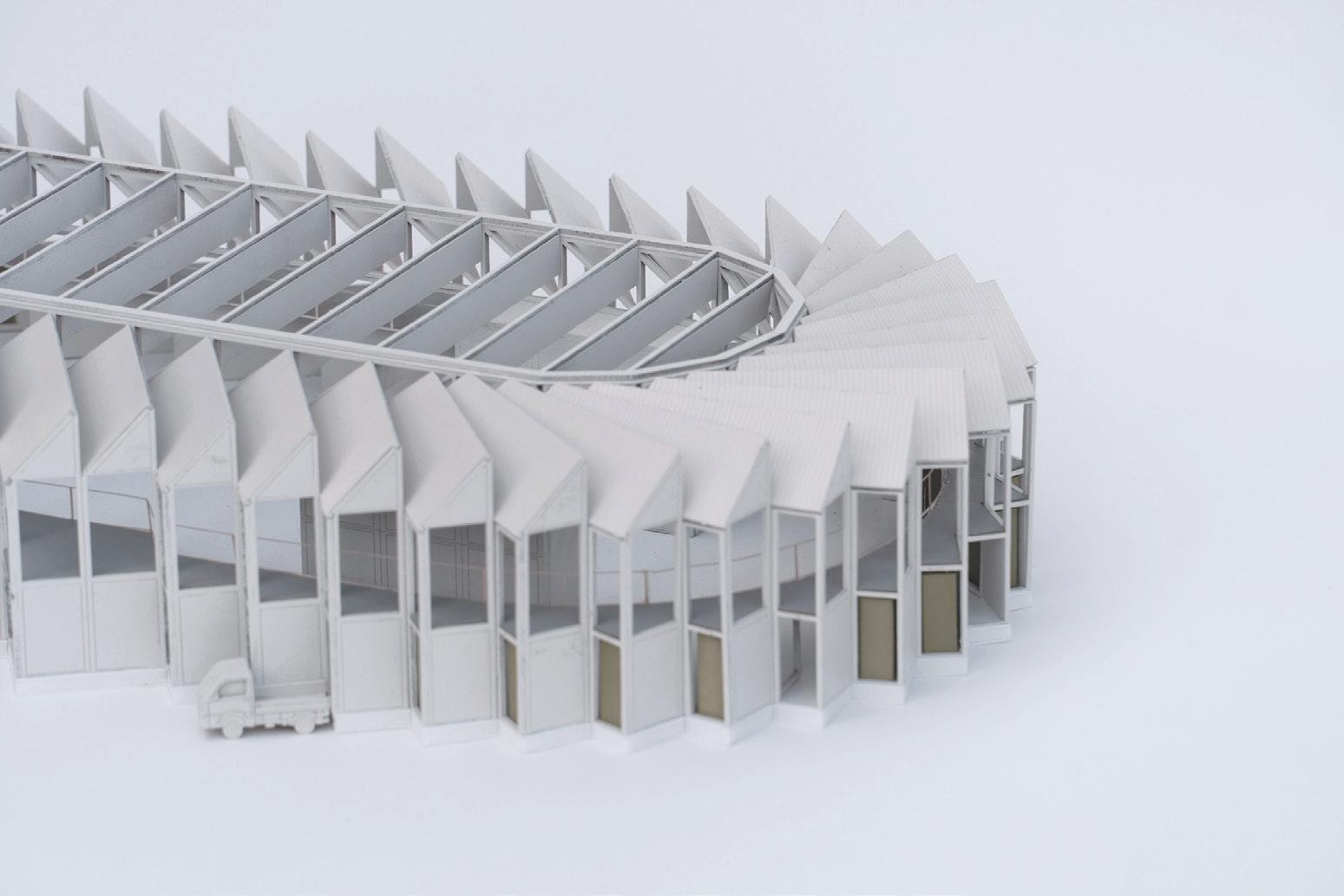

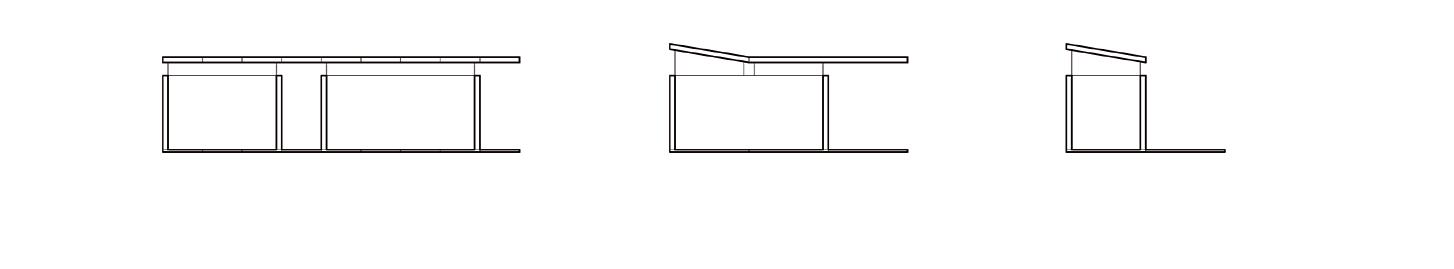

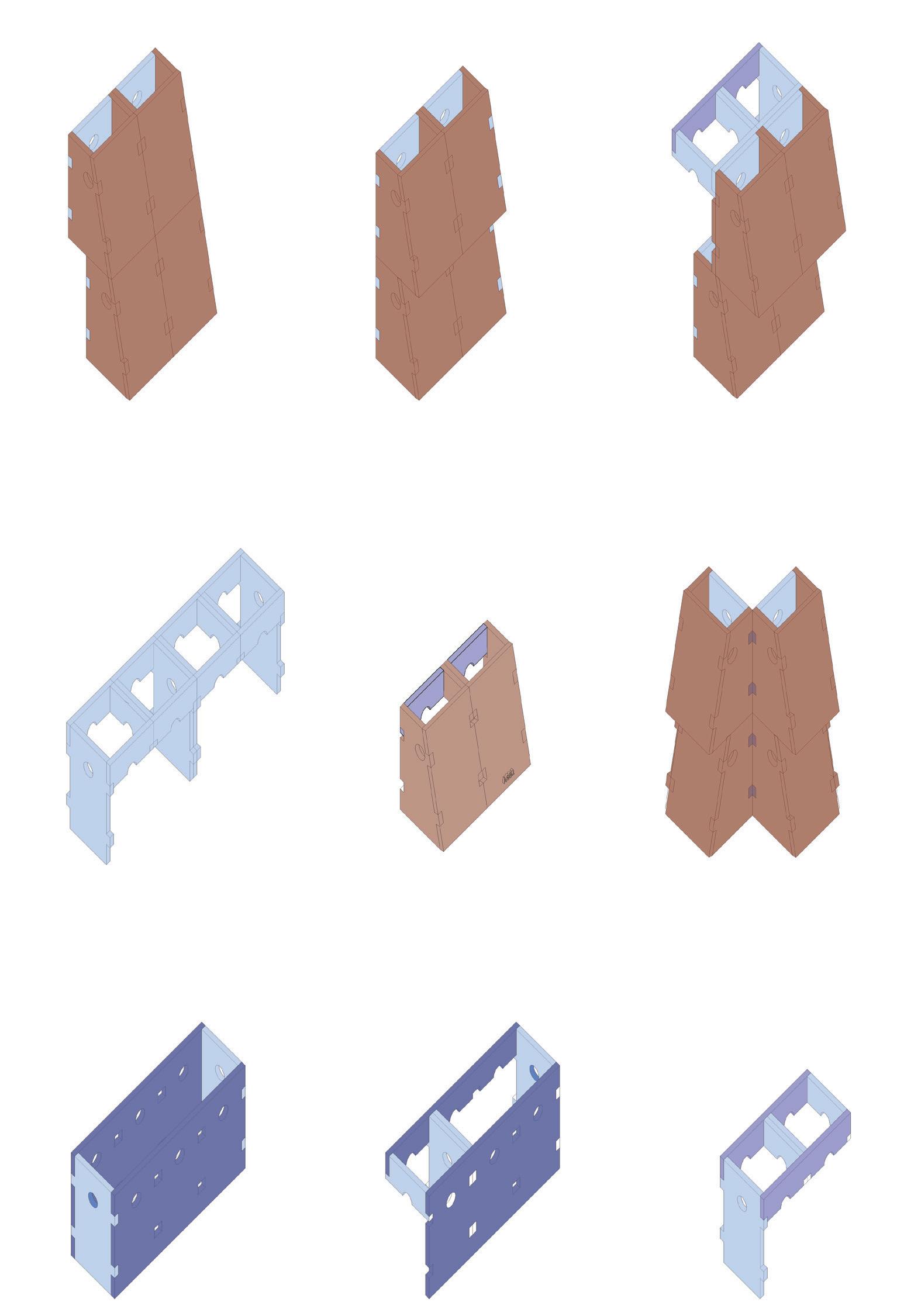

This project consists of three modules whose geometry enables a range of combinatory forms that can expand and contract as needed. Module 01 has a square footprint of 4.8 m x 4.8 m, while Modules 02 and 03 retain the same 4.8 m radius and sweep it across 60 degrees, creating a pizza-slice-shaped footprint. Their roofs slope in inverse directions, allowing Module 01 to turn corners in multiple ways—though never at a right angle.

The modules draw inspiration from old Japanese compounds and the care with which they frame gardens. The construction and assembly process is informed by the handcrafted precision of Japanese joinery and embraces the ornamentation of structural redundancy—a quality often hidden beneath modernist aesthetics.

Once an aggregate form is composed, cladding is applied selectively to enable a range of programmatic potentials and spatial intimacies—from large, porous spaces open to gardens to small, enclosed offices for individual privacy.

The design proposes an adaptable architectural language that resists rigid formal prescriptions. It invites growth, subtraction, and transformation over time, privileging relationships: between interior and exterior, individual and collective, and structure and site.

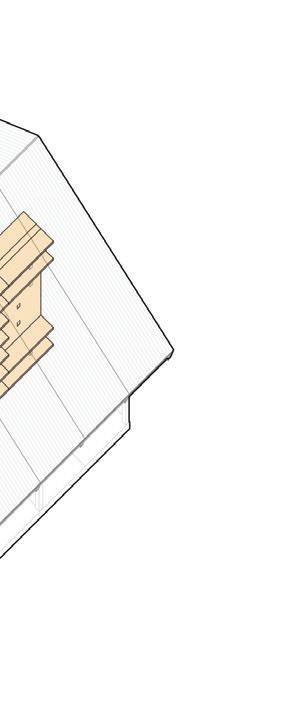

Above: Aggregate Schematic of proposed

Above: Aggregate Isonomteric view

DIMENSIONS

L 4800 mm W 4800 mm H 4800 mm

* NOTE THAT PACKAGE DOES NOT COME WITH CLADDING

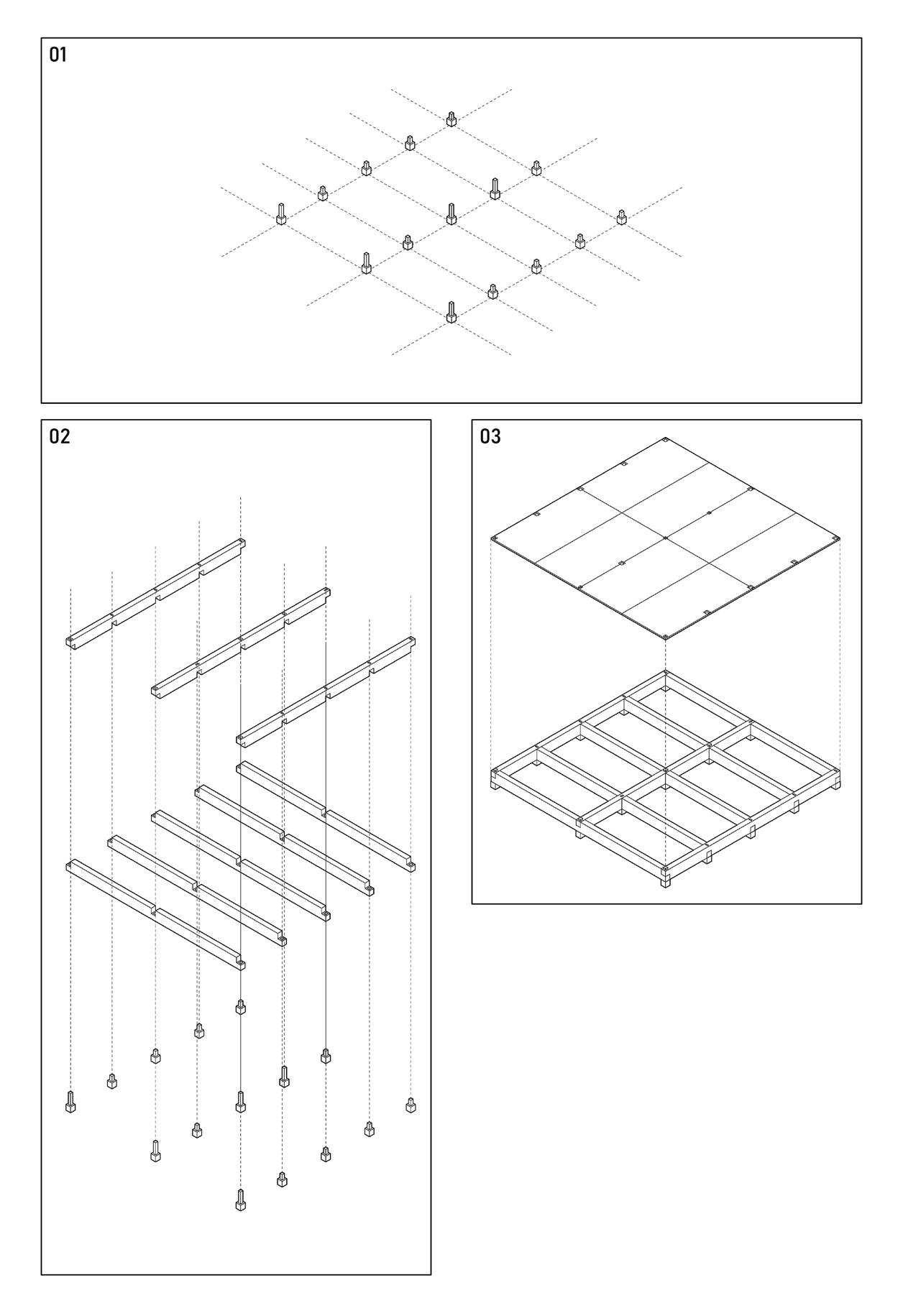

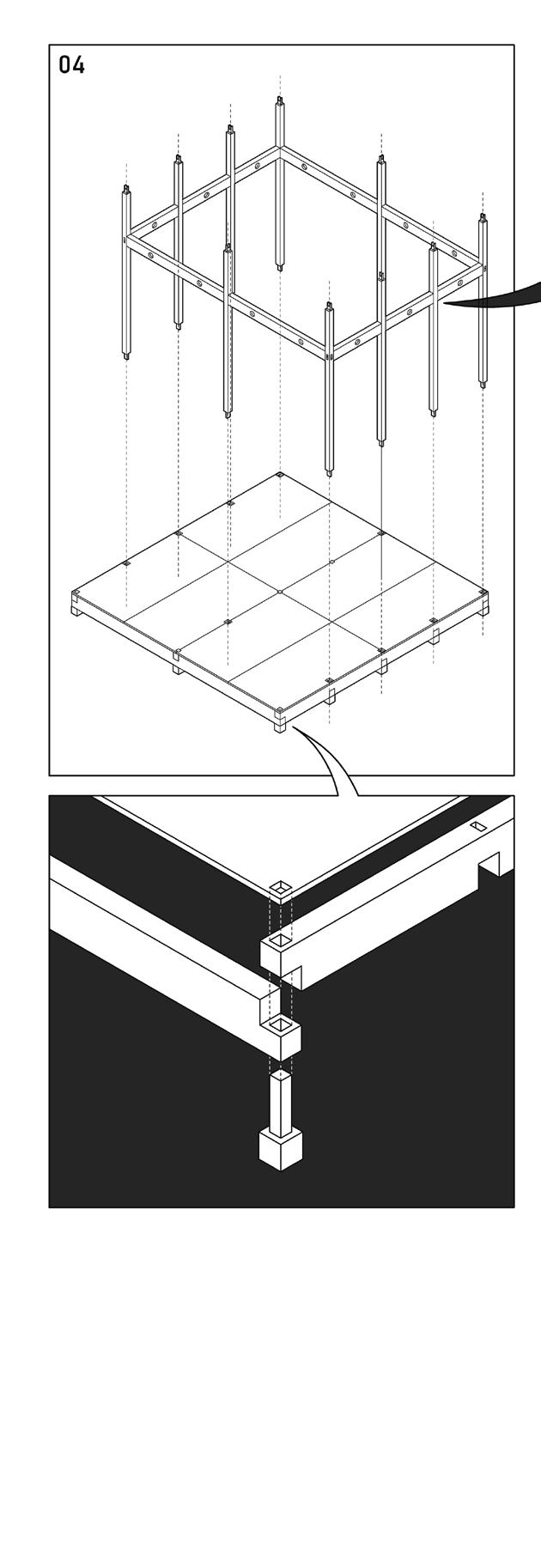

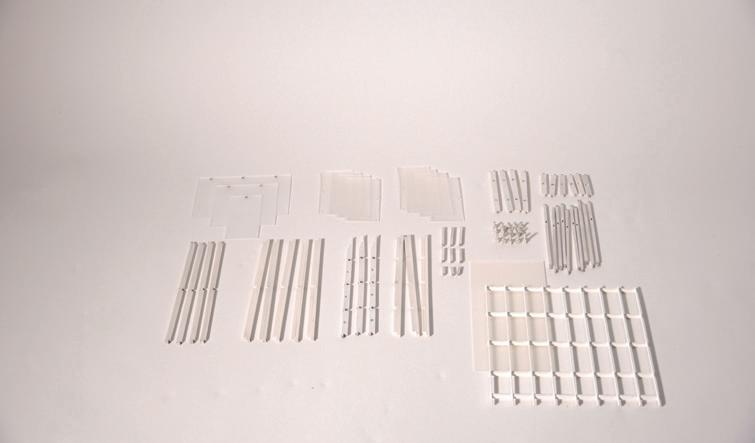

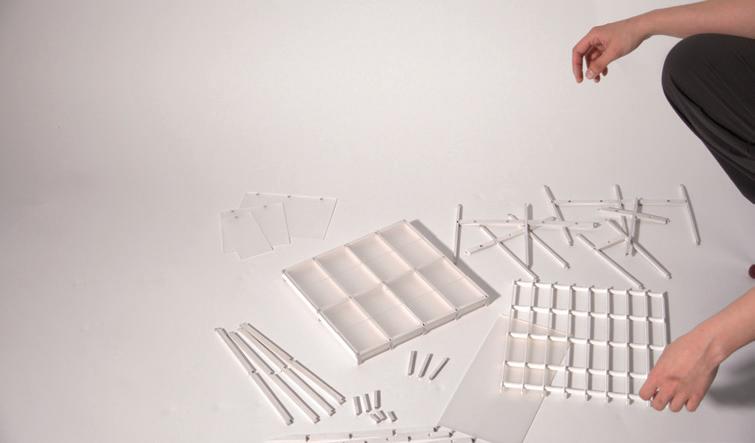

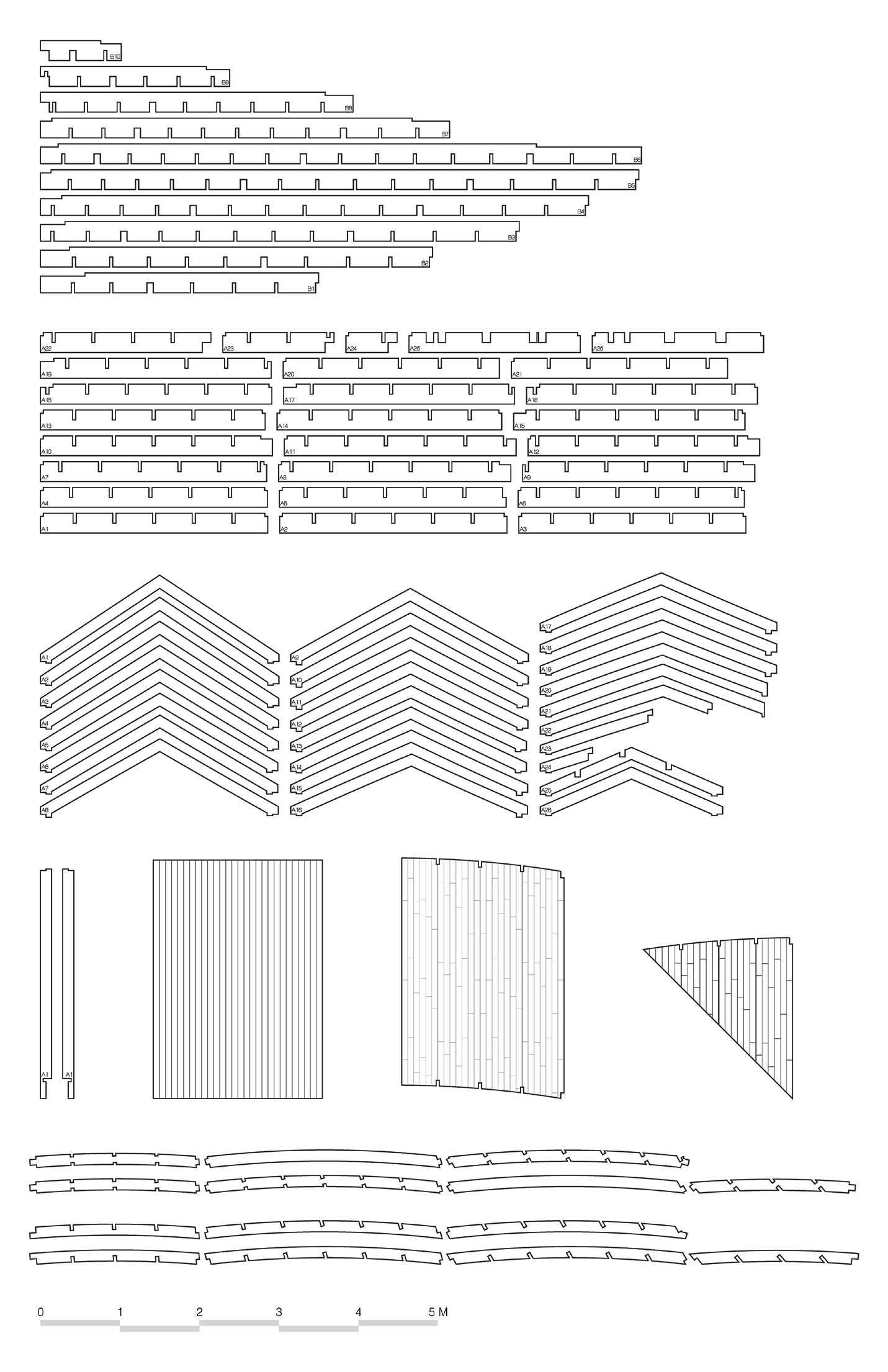

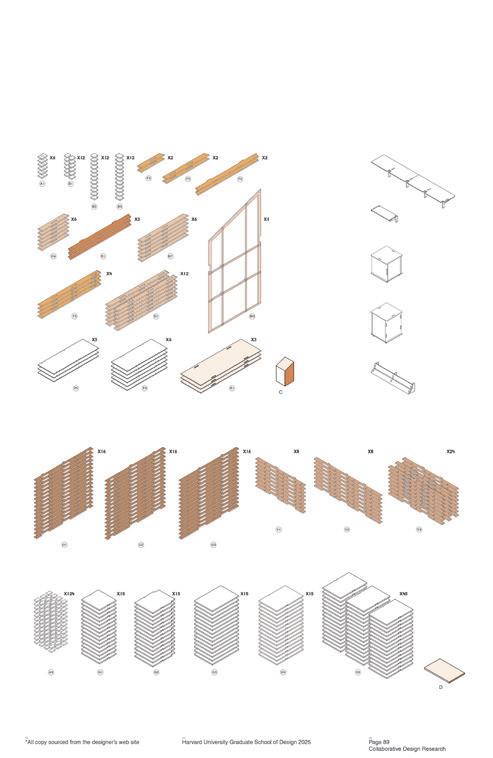

Above and following page: General design idea of Module 1 and parts list

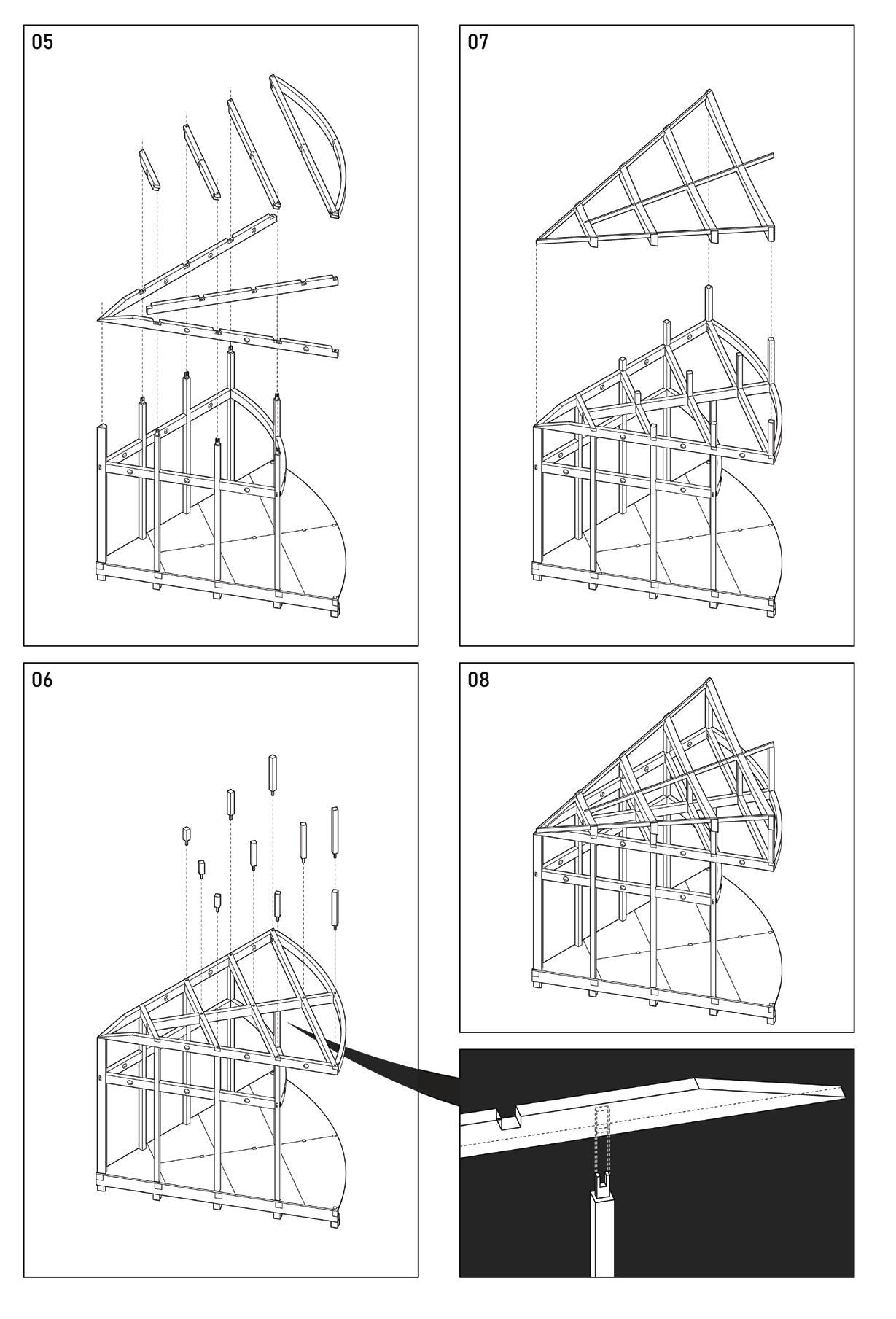

CAREFULLY READ INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE ASSEMBLY. REFER TO ILLUSTRATIONS AND PAY ATTENTION TO PARTS ORIENTATION DURING

ASSEMBLY

SOME PARTS MAY BE DIFFICULT TO DISTINGUISH FROM ONE ANOTHER. PAY EXTRA ATTENTION WHEN HANDLING SHARP POINTS AND EDGES. TO AVOID SUFFOCATION, DO NOT PUT THE PLASTIC BAG OVER YOUR FACE.

MODULE 02_ TIMBER FRAME ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS

DIMENSIONS

RADIUS 4800 mm

ANGLE 60 ° H 4800 mm

* NOTE THAT PACKAGE DOES NOT COME WITH CLADDING ** ELEVATION HEIGHTS SAME AS MODULE 01 30 °

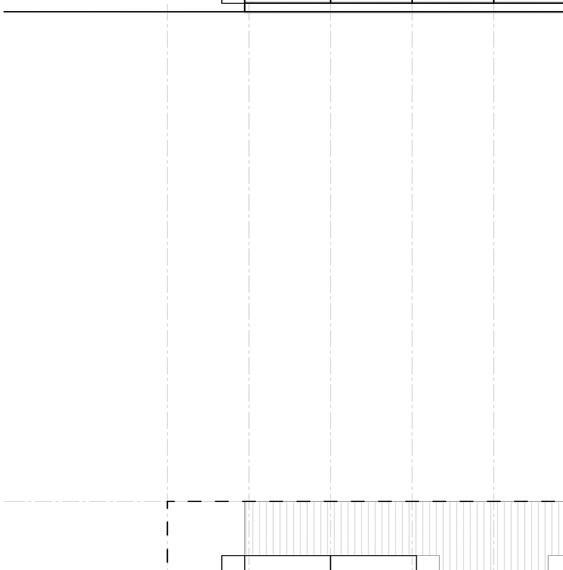

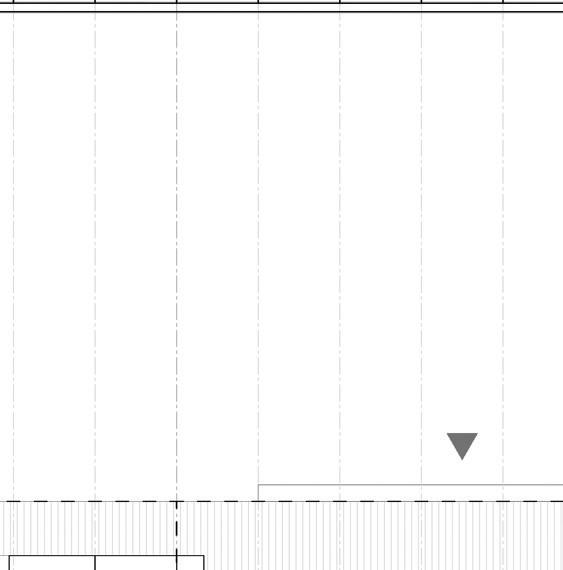

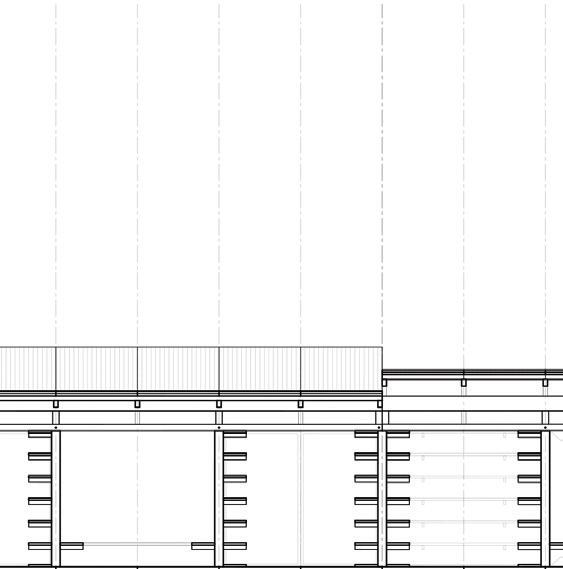

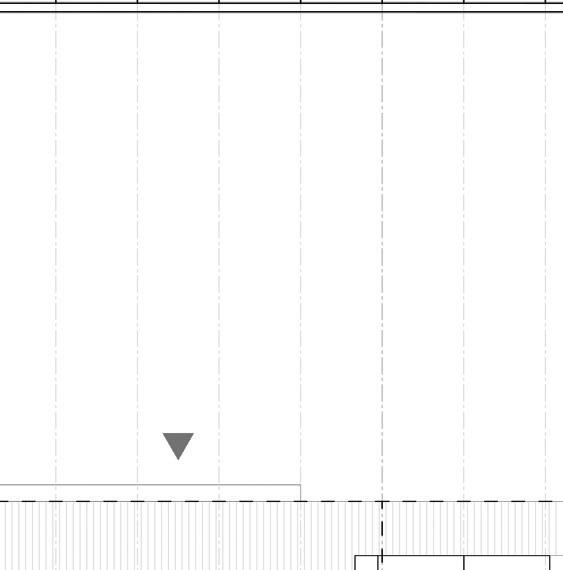

PLAN SCHEMATIC SIDE ELEVATION FRONT ELEVATION

Above and following page: General design idea of Module 2 and parts list

CAREFULLY READ INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE ASSEMBLY. REFER TO ILLUSTRATIONS AND PAY ATTENTION TO PARTS ORIENTATION DURING ASSEMBLY

SOME PARTS MAY BE DIFFICULT TO DISTINGUISH FROM ONE ANOTHER. PAY EXTRA ATTENTION WHEN HANDLING SHARP POINTS AND EDGES. TO AVOID SUFFOCATION, DO NOT PUT THE PLASTIC BAG OVER YOUR FACE.

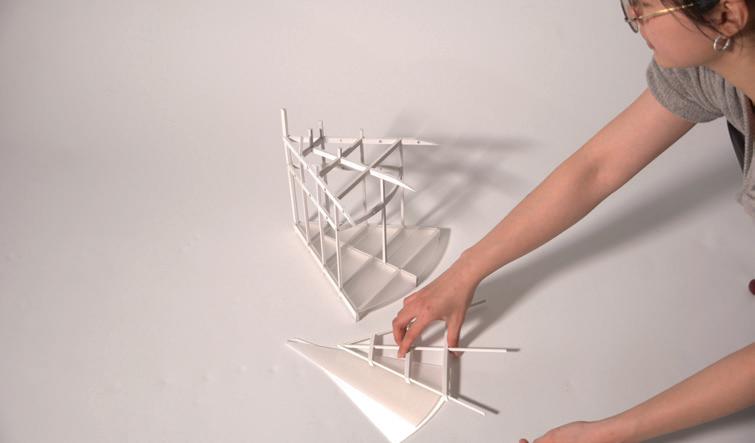

MODULE 03_ TIMBER FRAME ASSEMBLY INSTRUCTIONS

DIMENSIONS

RADIUS 4800 mm

ANGLE 60 ° H 4800 mm

* NOTE THAT PACKAGE DOES NOT COME WITH CLADDING ** ELEVATION HEIGHTS SAME AS MODULE 01 30 °

PLAN SCHEMATIC SIDE ELEVATION FRONT ELEVATION

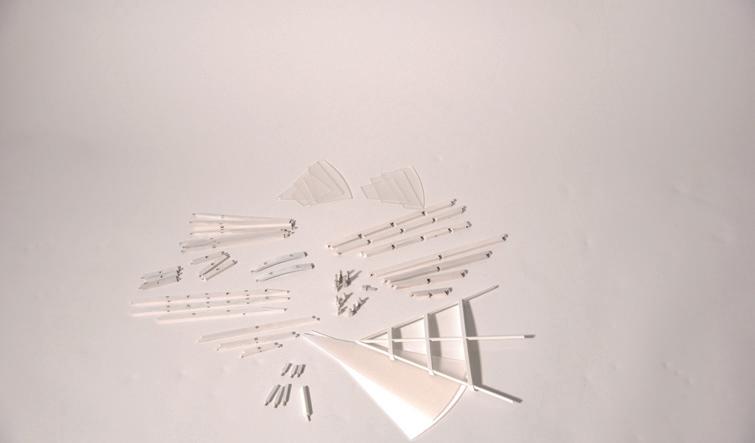

Above and following page: General design idea of Module 3 and parts list

CAREFULLY READ INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE ASSEMBLY. REFER TO ILLUSTRATIONS AND PAY ATTENTION TO PARTS ORIENTATION DURING ASSEMBLY

SOME PARTS MAY BE DIFFICULT TO DISTINGUISH FROM ONE ANOTHER. PAY EXTRA ATTENTION WHEN HANDLING SHARP POINTS AND EDGES. TO AVOID SUFFOCATION, DO NOT PUT THE PLASTIC BAG OVER YOUR FACE.

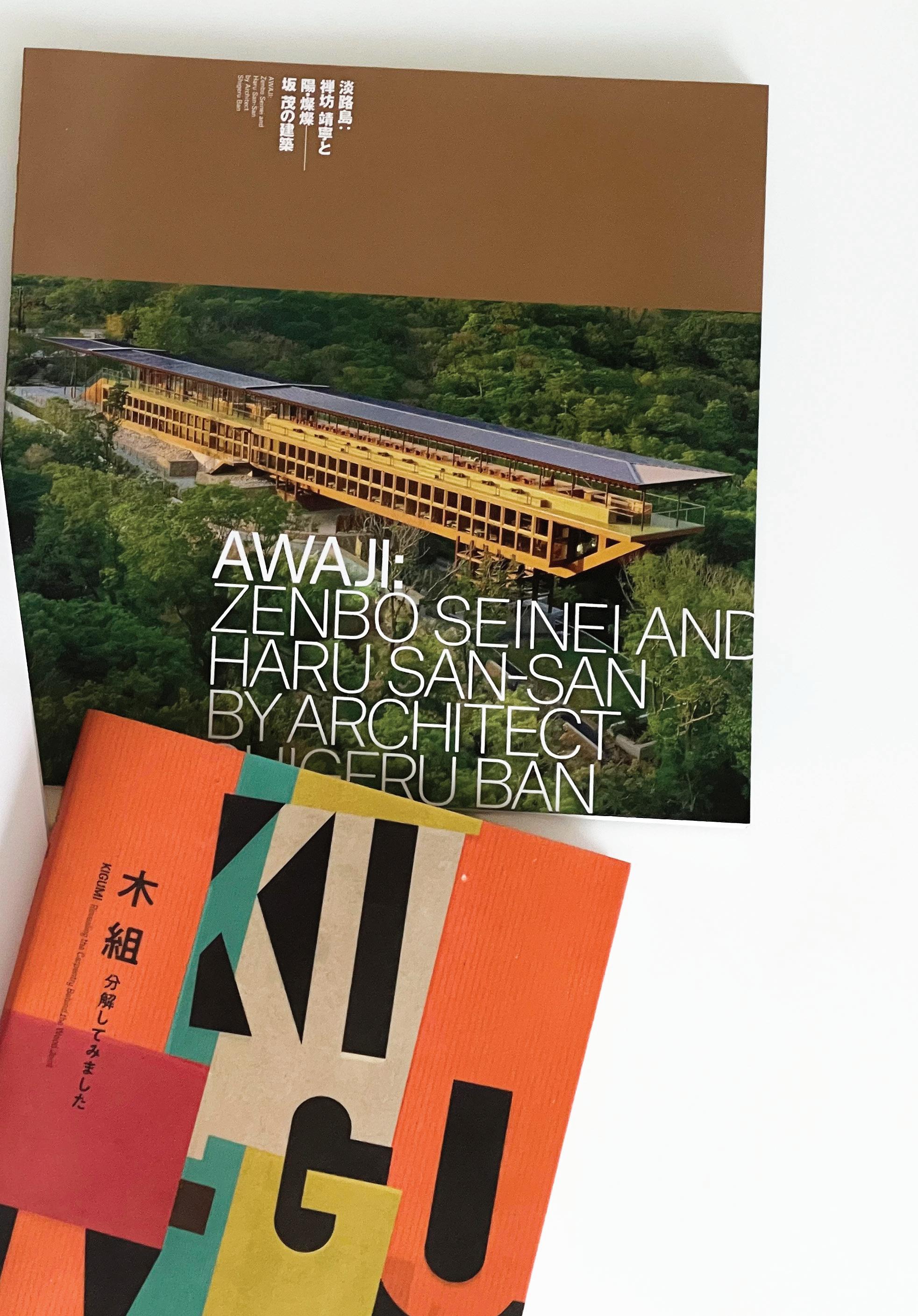

Studio research publication along the monograph

a

This project envisions a storage stockpile and community center designed for dual use: supporting everyday life while transforming into vital infrastructure during disasters. Located near the epicenter of the 1995 Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake, the site underscores the urgency of resilient design in Japan.

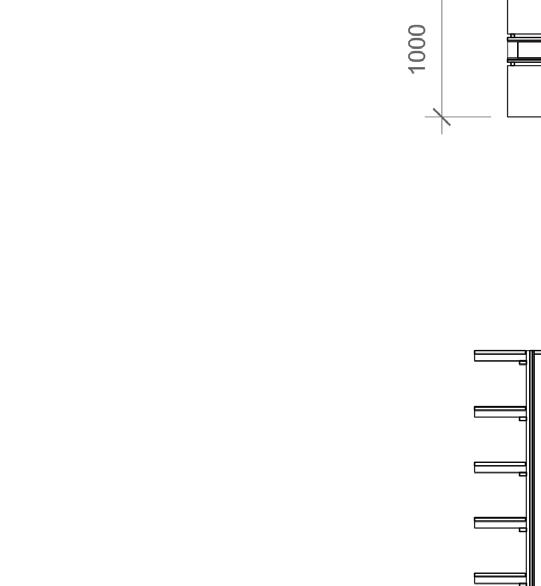

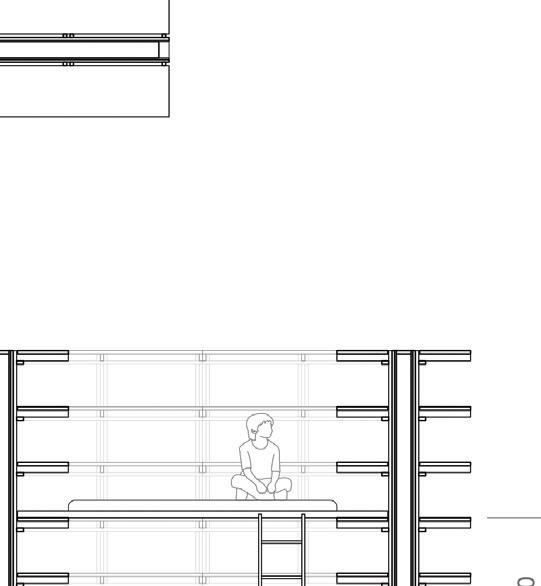

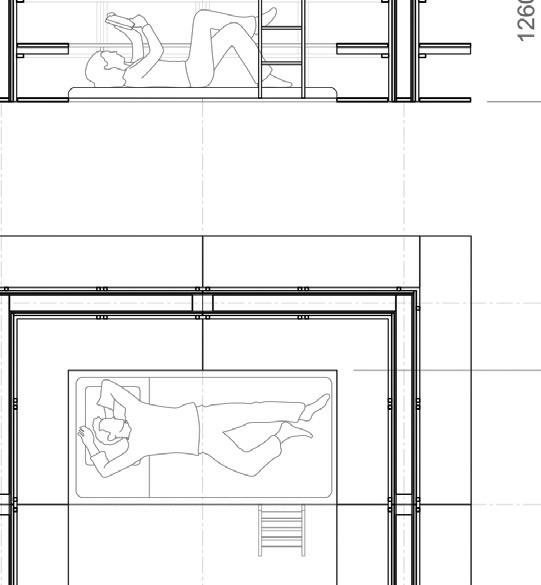

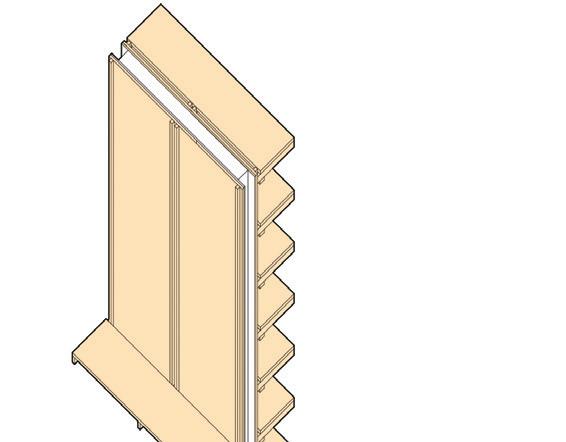

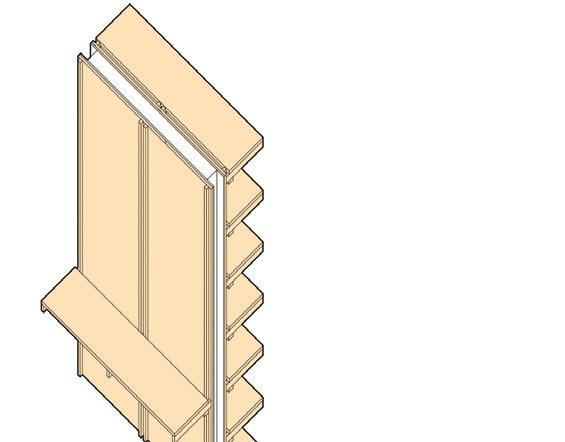

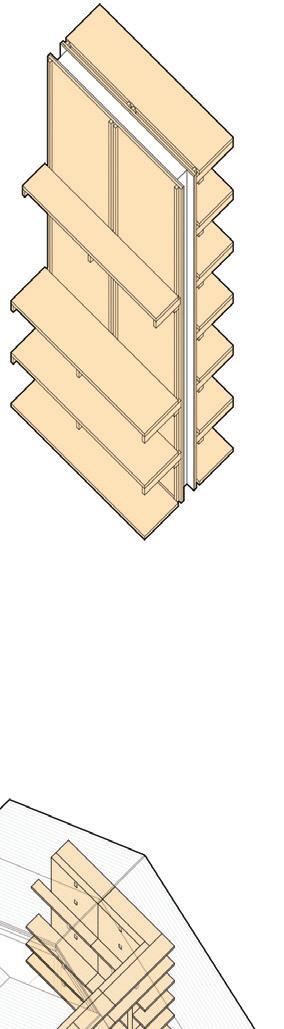

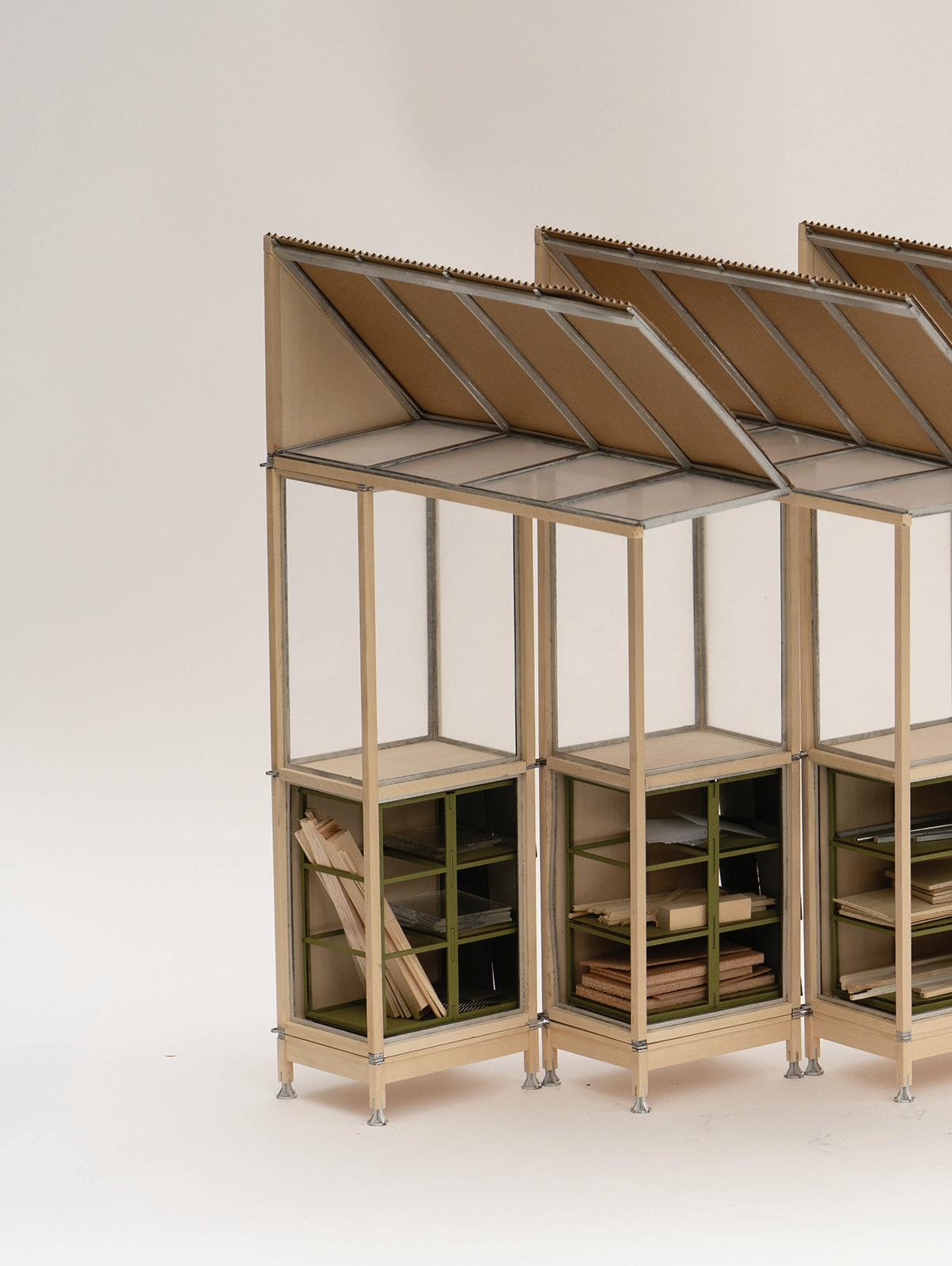

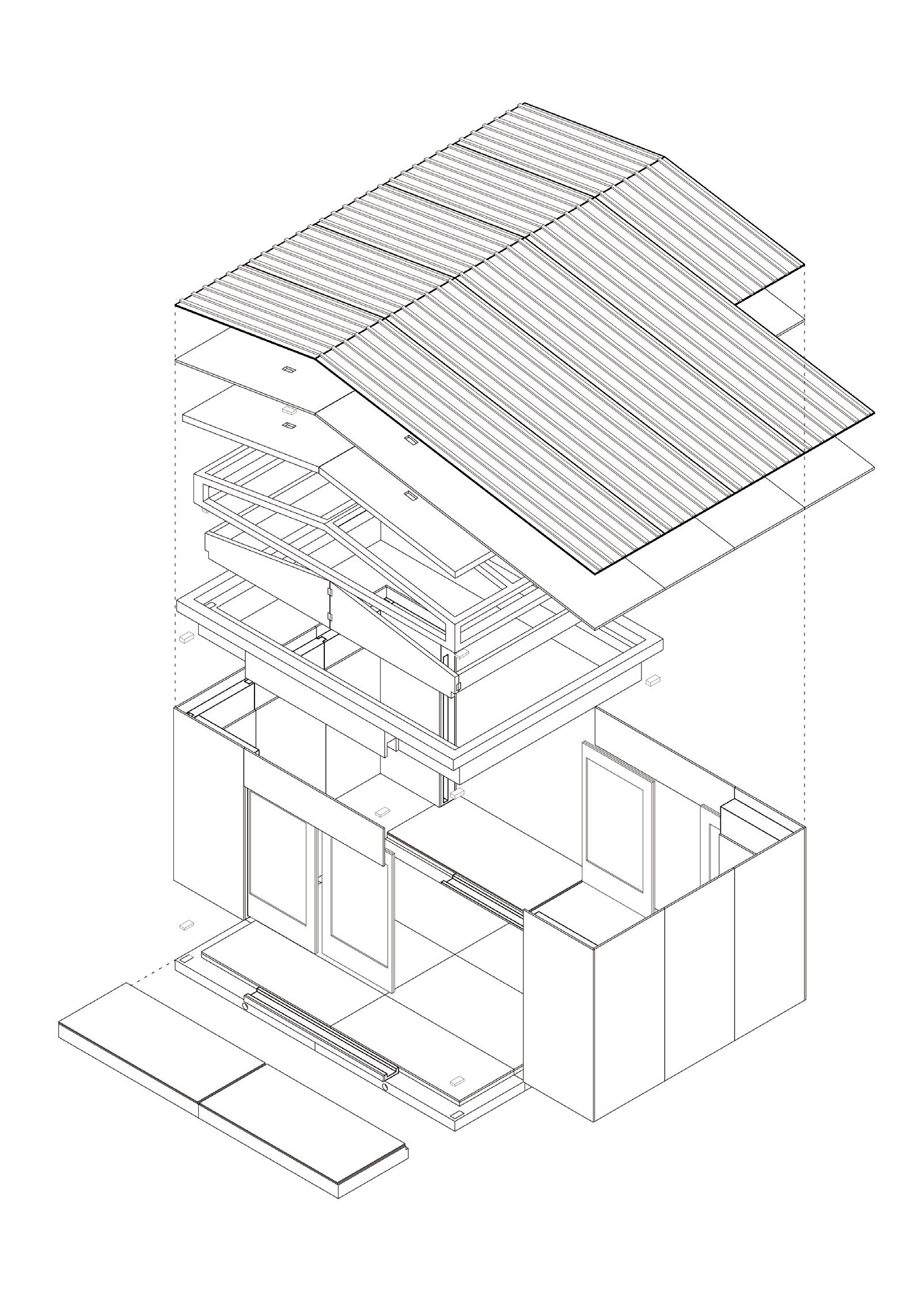

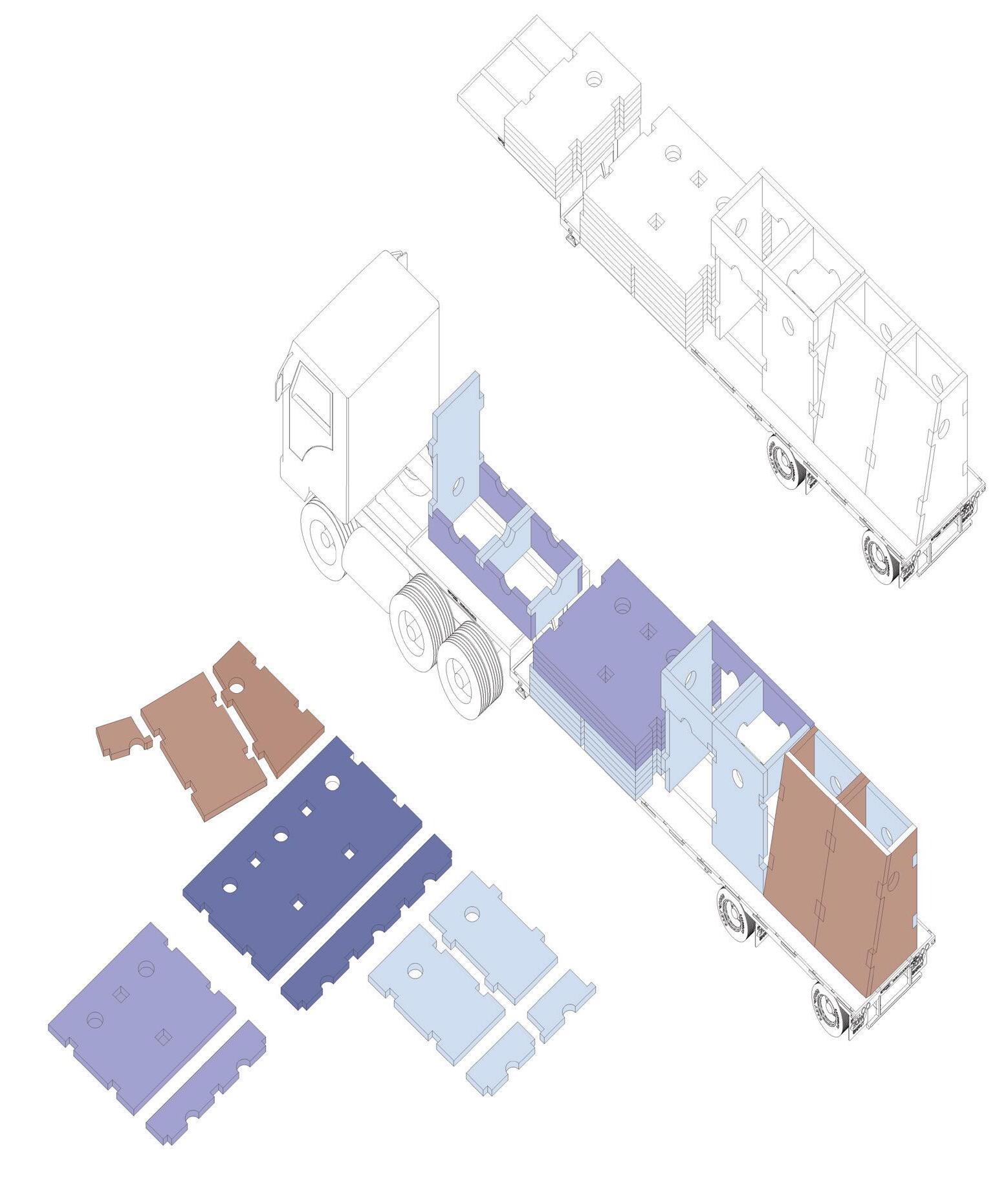

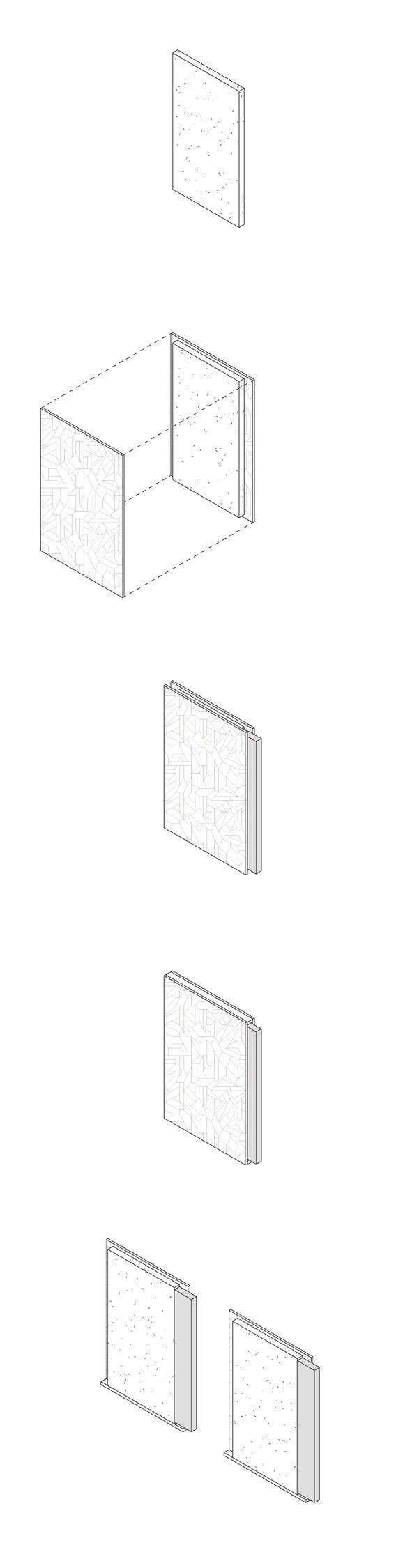

Inspired by the Japanese spirit of jishubo (voluntary disaster prevention organizations), the center employs Open Structure Method (OSM) principles to form flexible spaces that function as co-working areas, a café, a retail shop, and storage under normal conditions—and convert into evacuation shelters, volunteer hubs, and emergency clinics during crises. The system uses augmented Structural Insulated Panel (SIP) units to enable rapid deployment and reconfiguration.

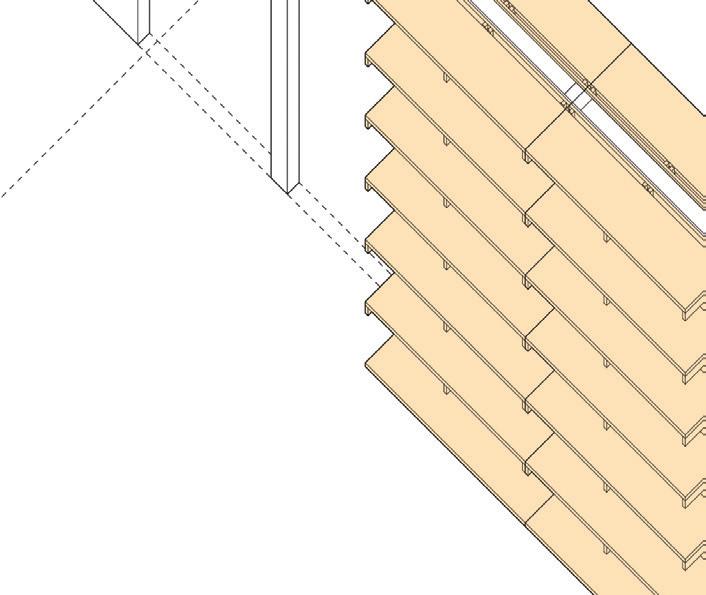

These “SIP Shelves” serve as shelving, counters, or seating depending on programmatic need. Grouped into modular clusters, they create a range of spaces from private to communal. Modules are sized per Evacuation Centre Model Plan guidelines, forming 2m x 4m nooks that accommodate 3–4 people each as temporary shelter. Each cluster is topped with a roof form that responds to the shelving below and references contextual gabled rooflines.

At the Asanokanda site, modules trace a sinuous path along the terrain, connecting main roads to the east and west. Departing from conventional gymnasium-style evacuation centers, this project emphasizes “future reuse” by embedding adaptability and resilience into daily life. It redefines architecture as both infrastructure and community catalyst—ready for crisis, yet grounded in everyday use.

a EPS Insulation Core

b Block-Spline Joint

c OSB Interior Panel

d OSB Exteror Panel

e Plywood

f Shelf Supports

g Shelf Panels

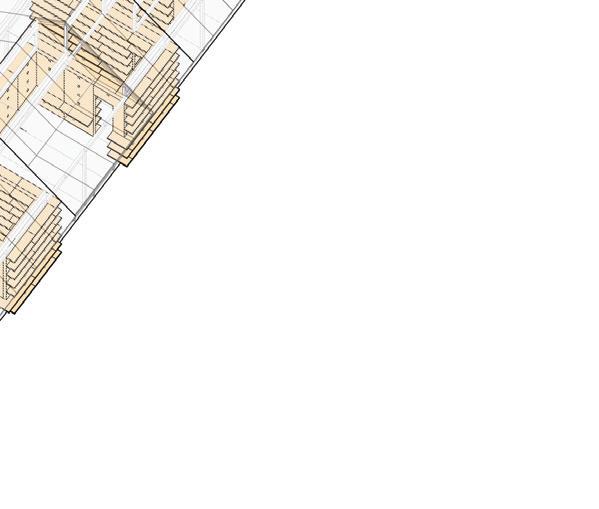

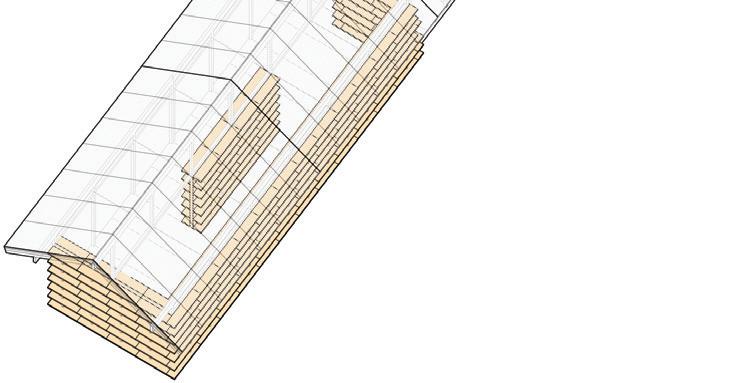

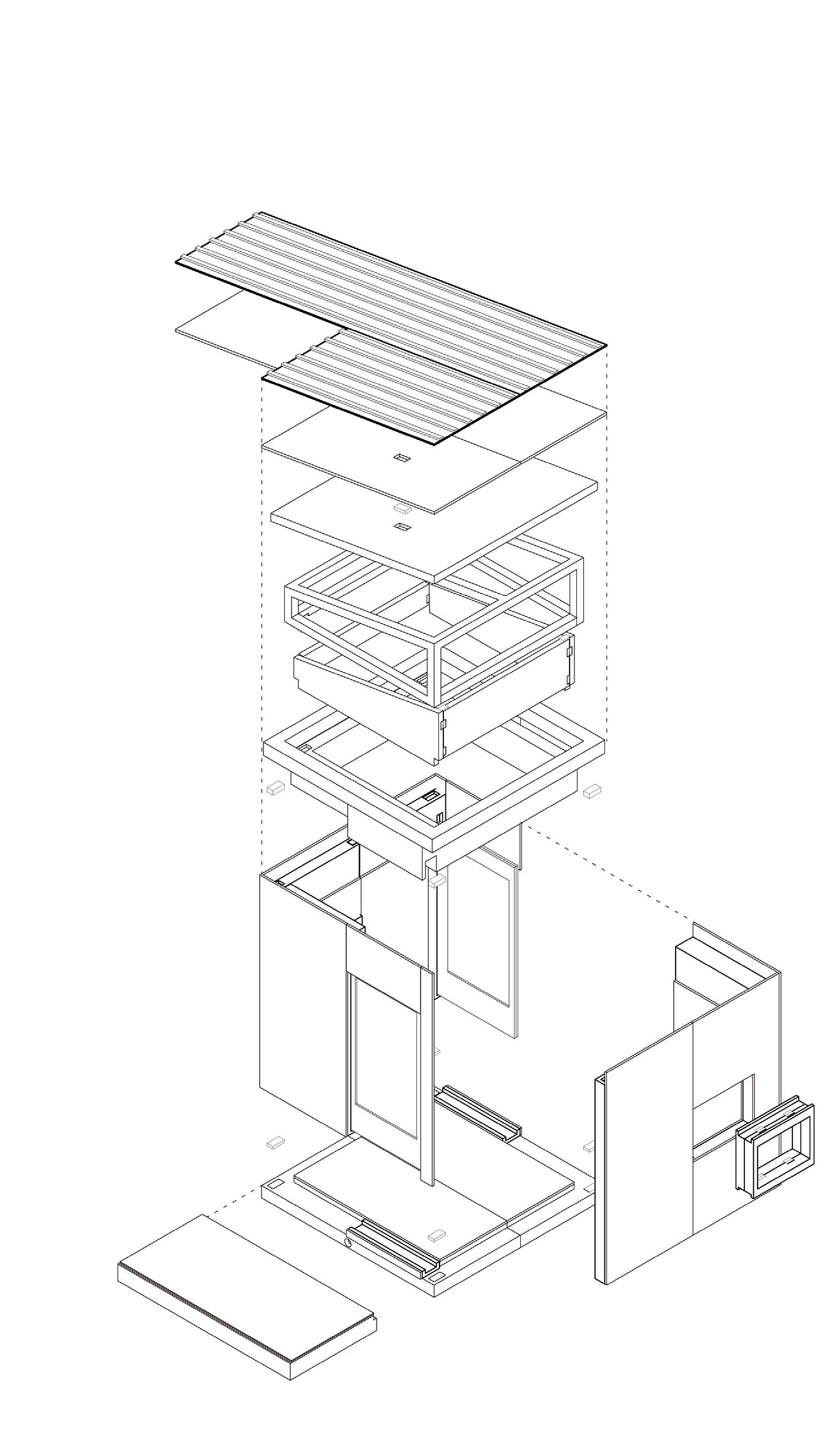

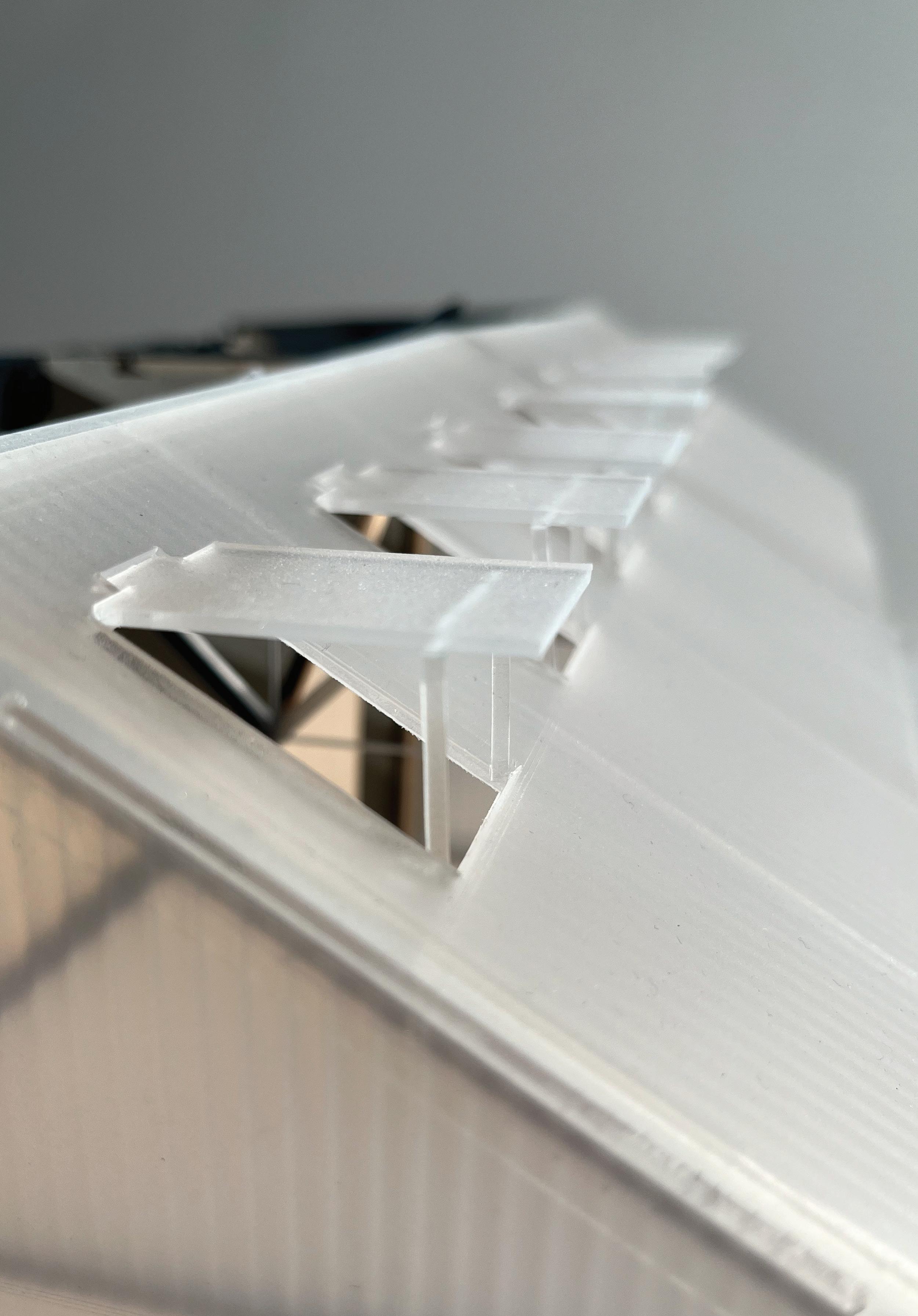

Previous page: Exploded SIP shelf module

Shelf module and nook dimensions

Across: Shelf module and shelf grouping types

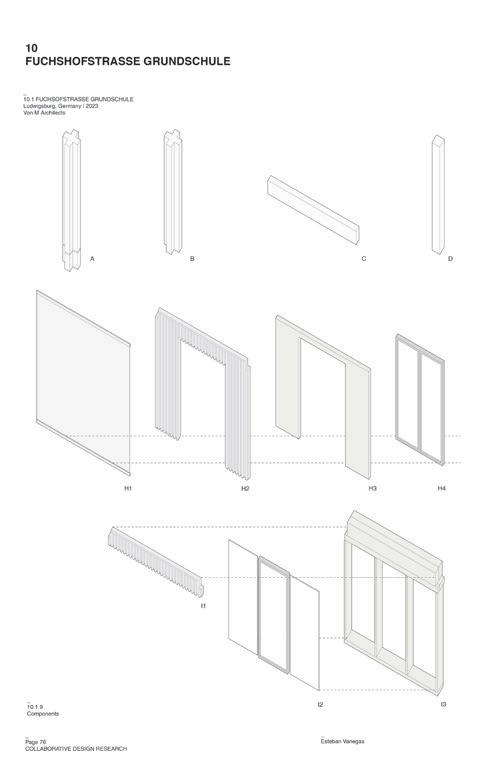

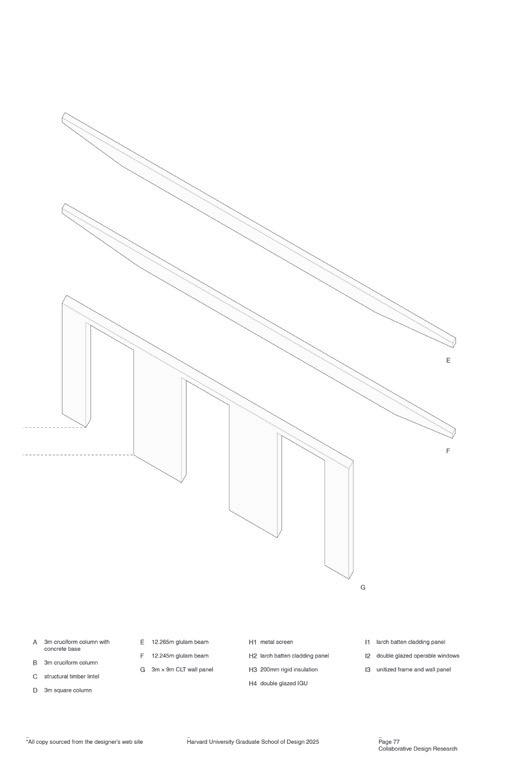

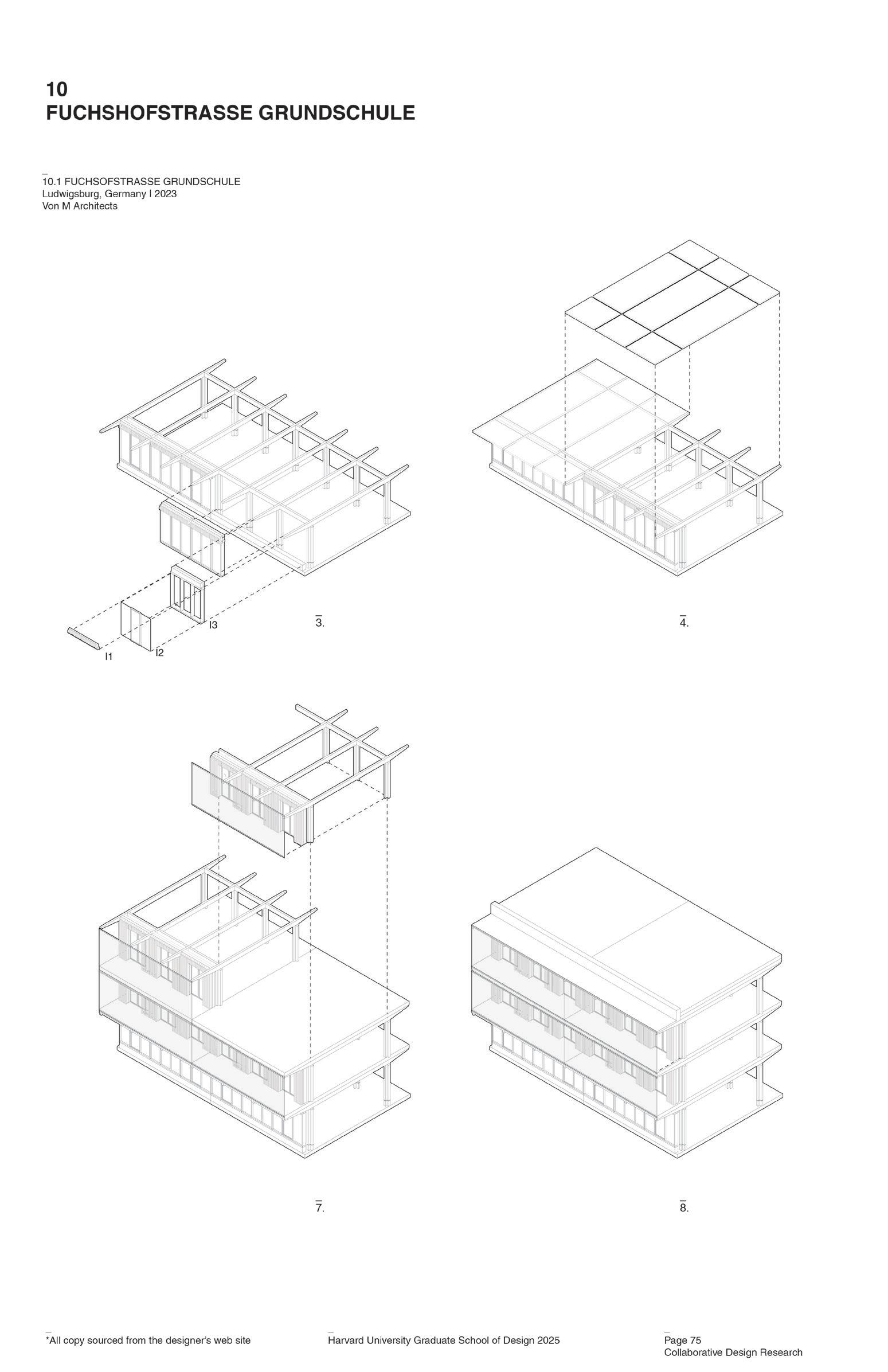

Top and following page: Fuchsofstrasse Grundschule by Von

research

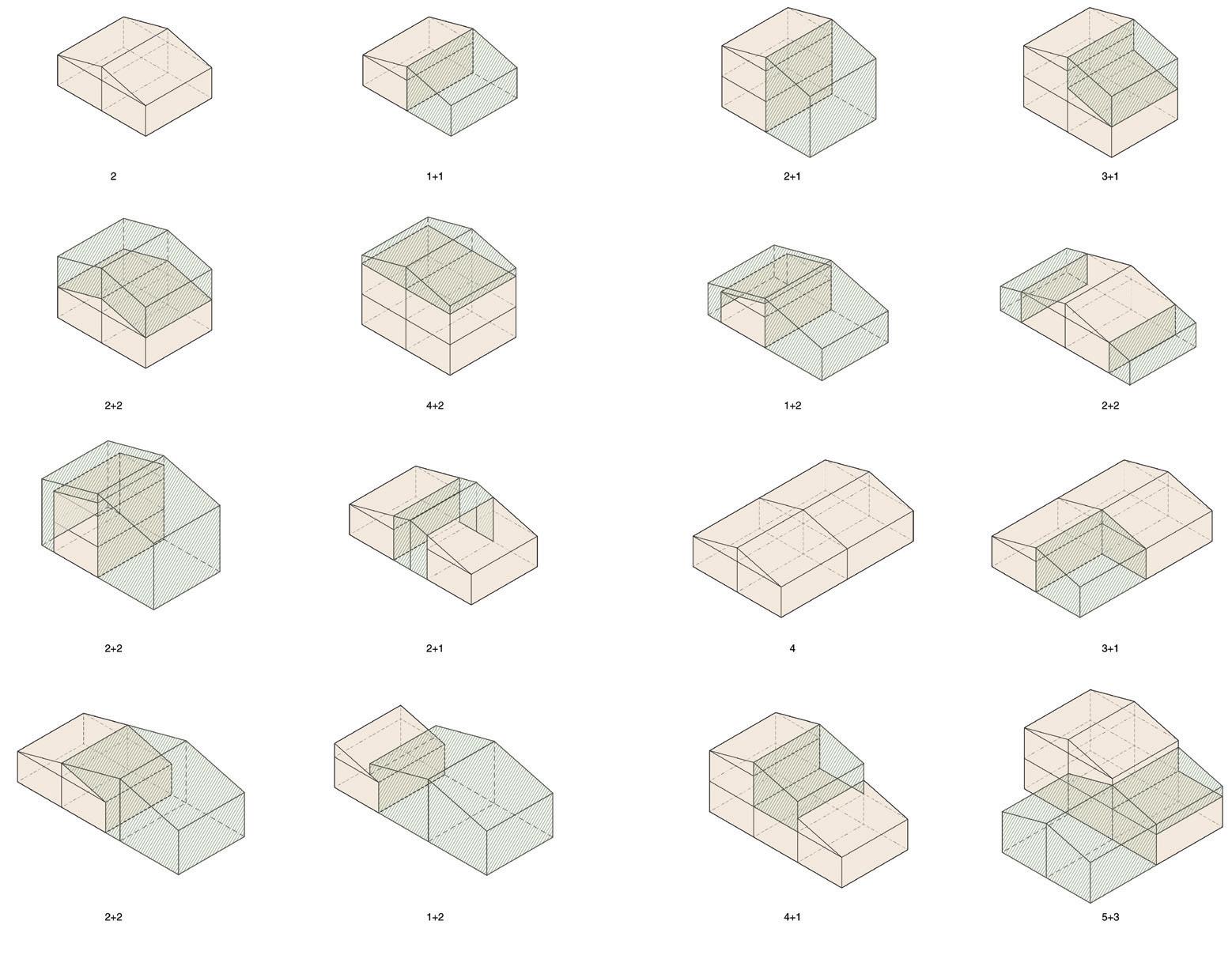

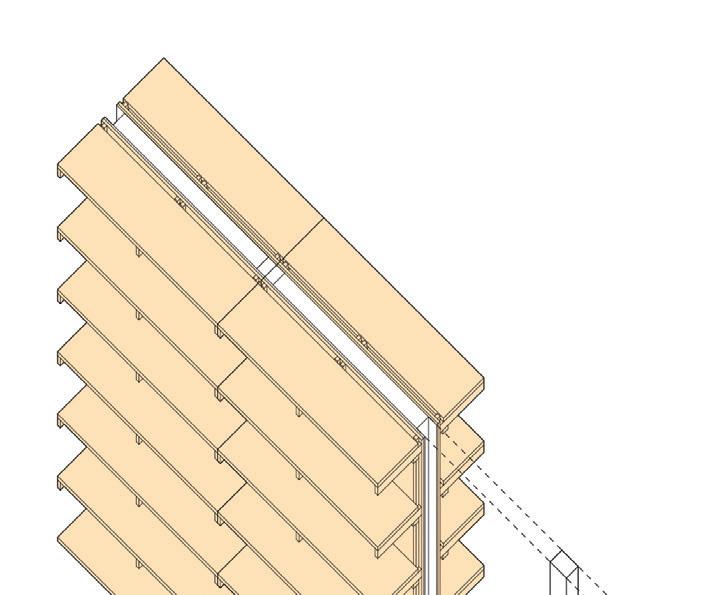

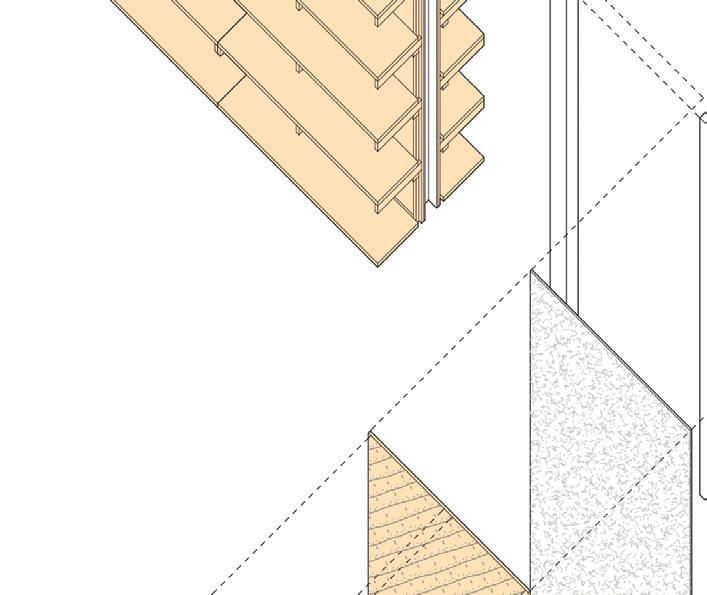

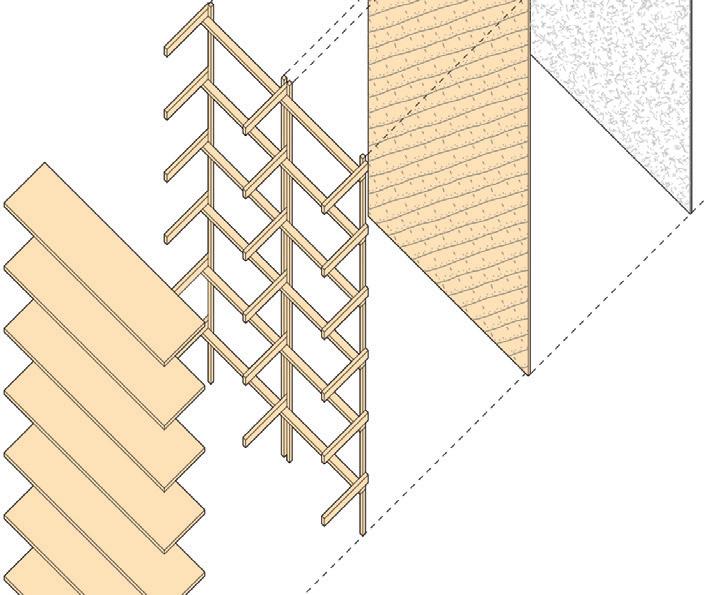

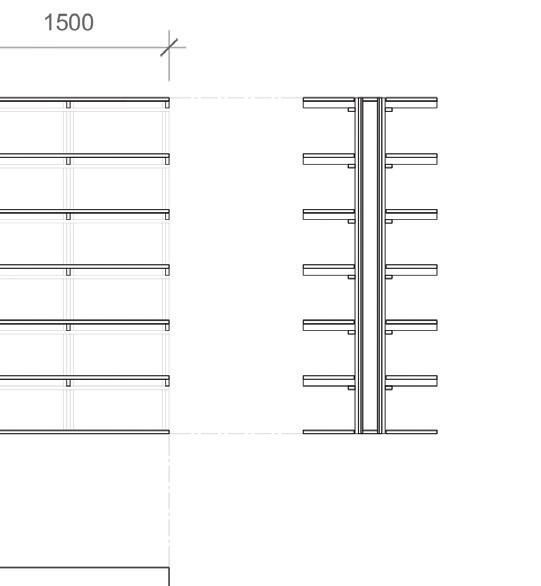

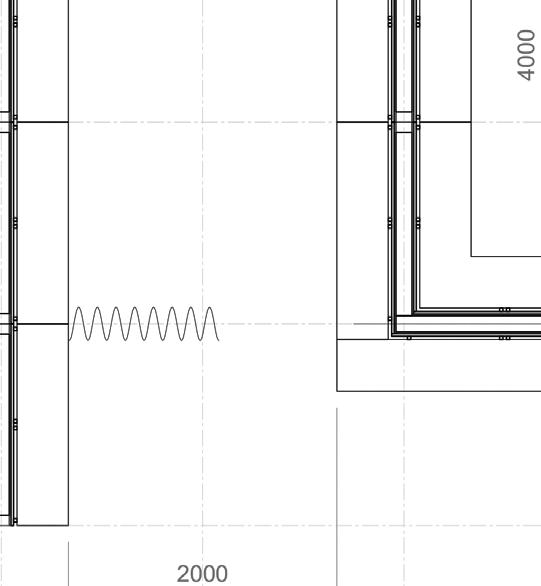

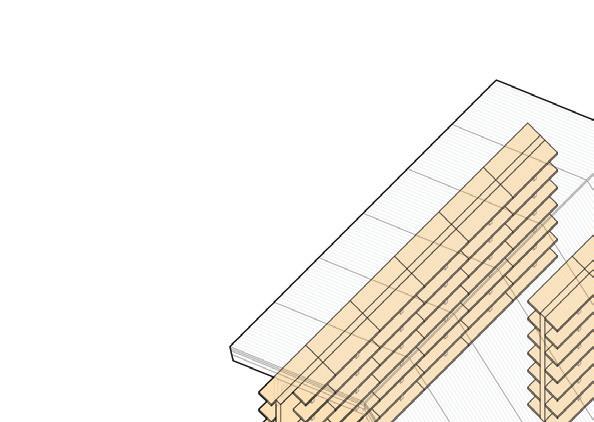

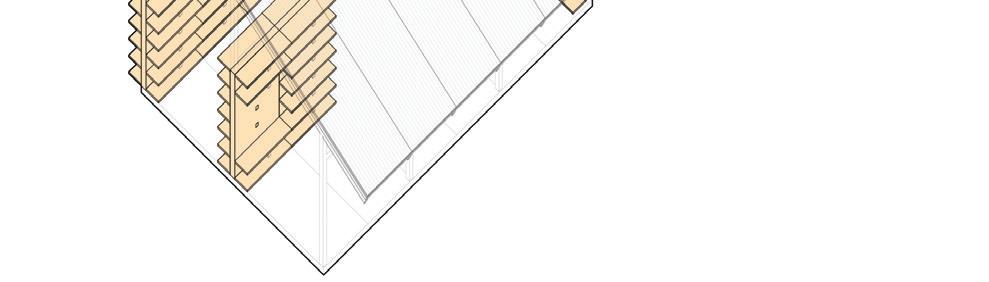

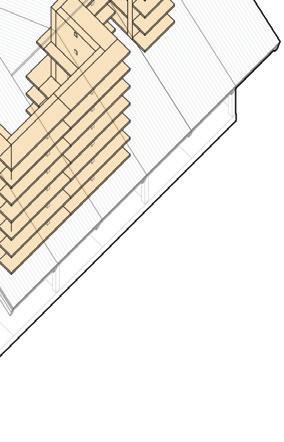

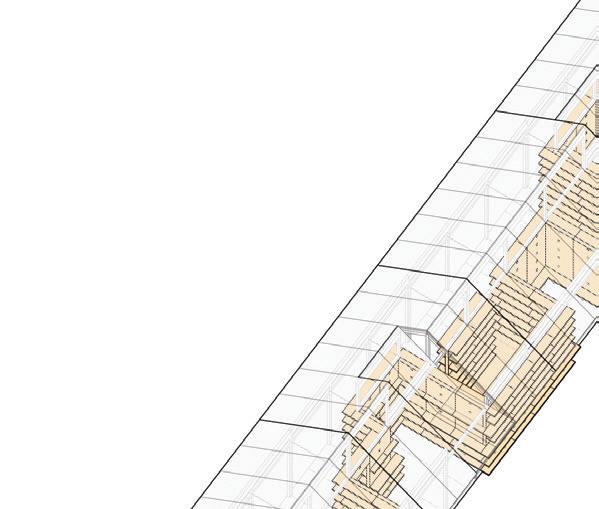

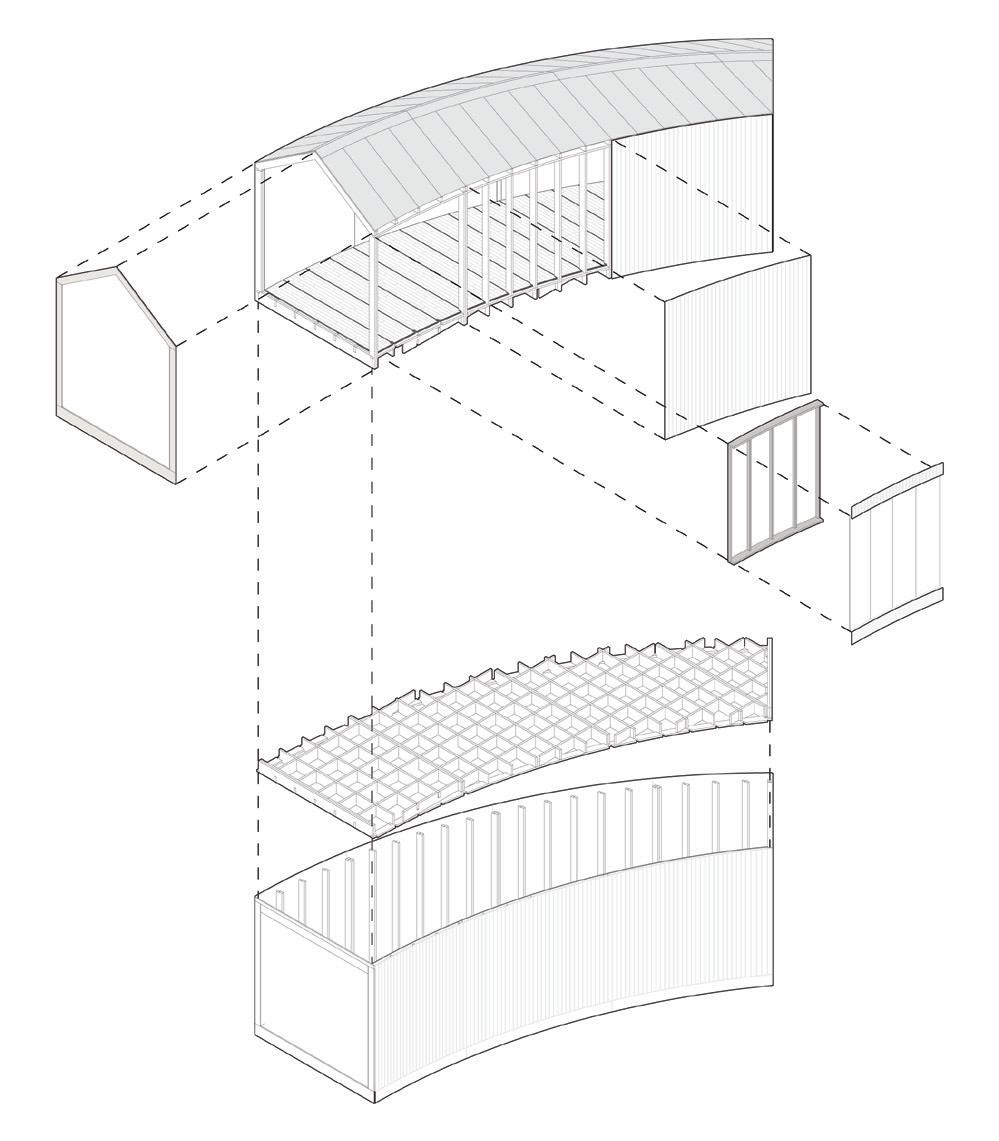

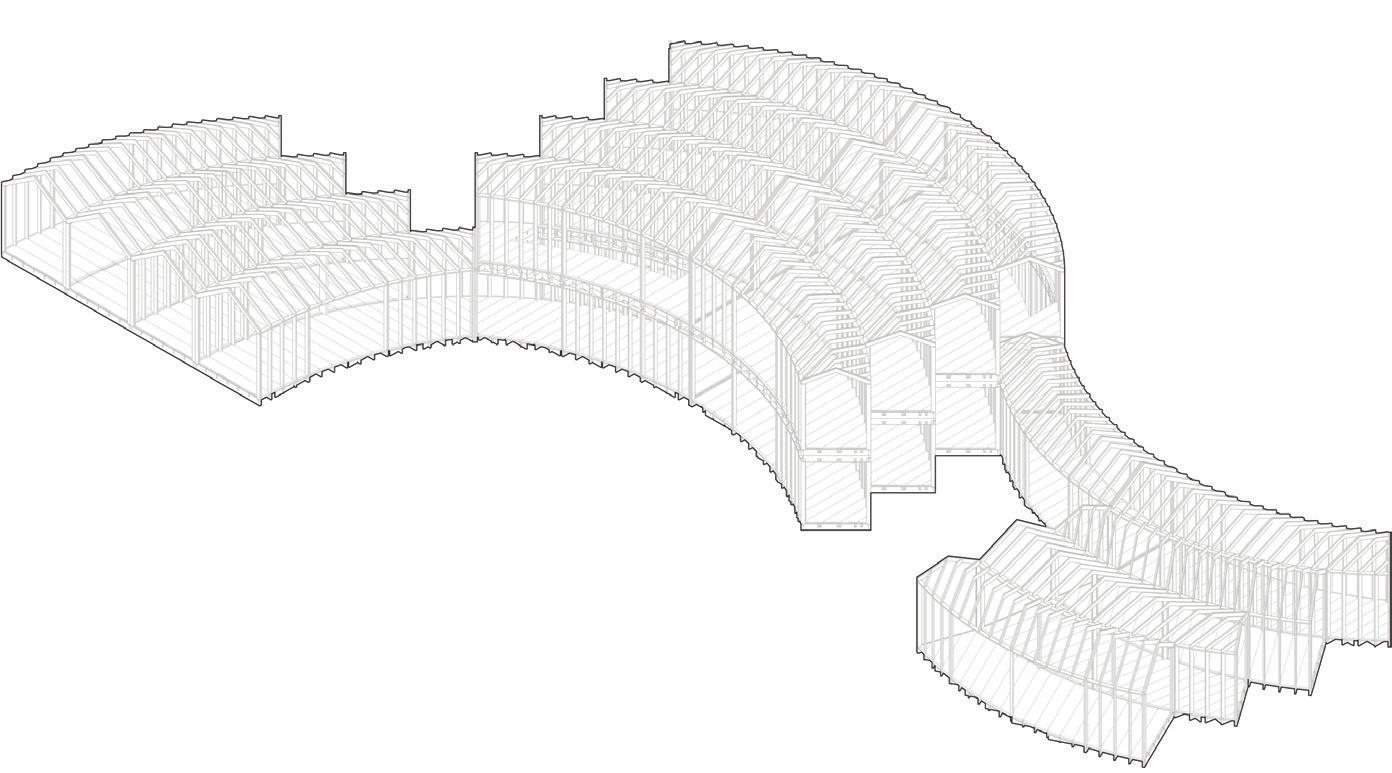

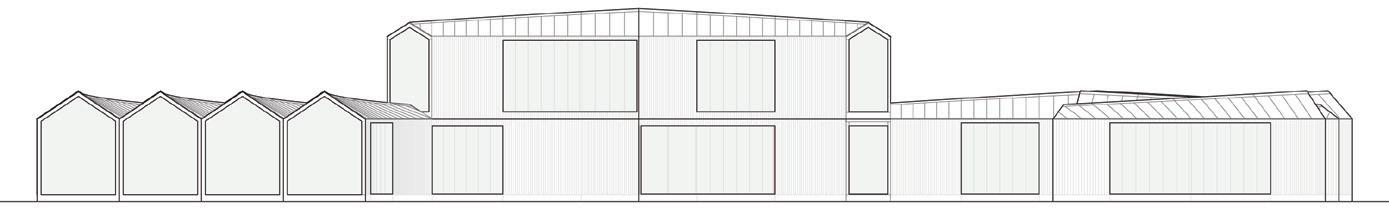

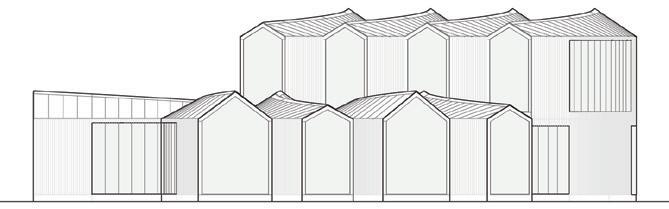

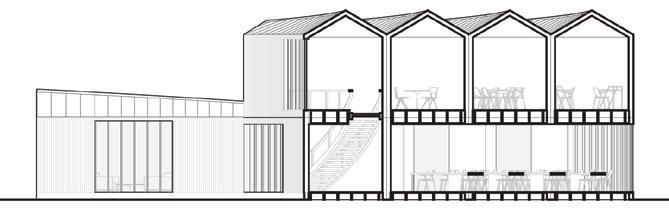

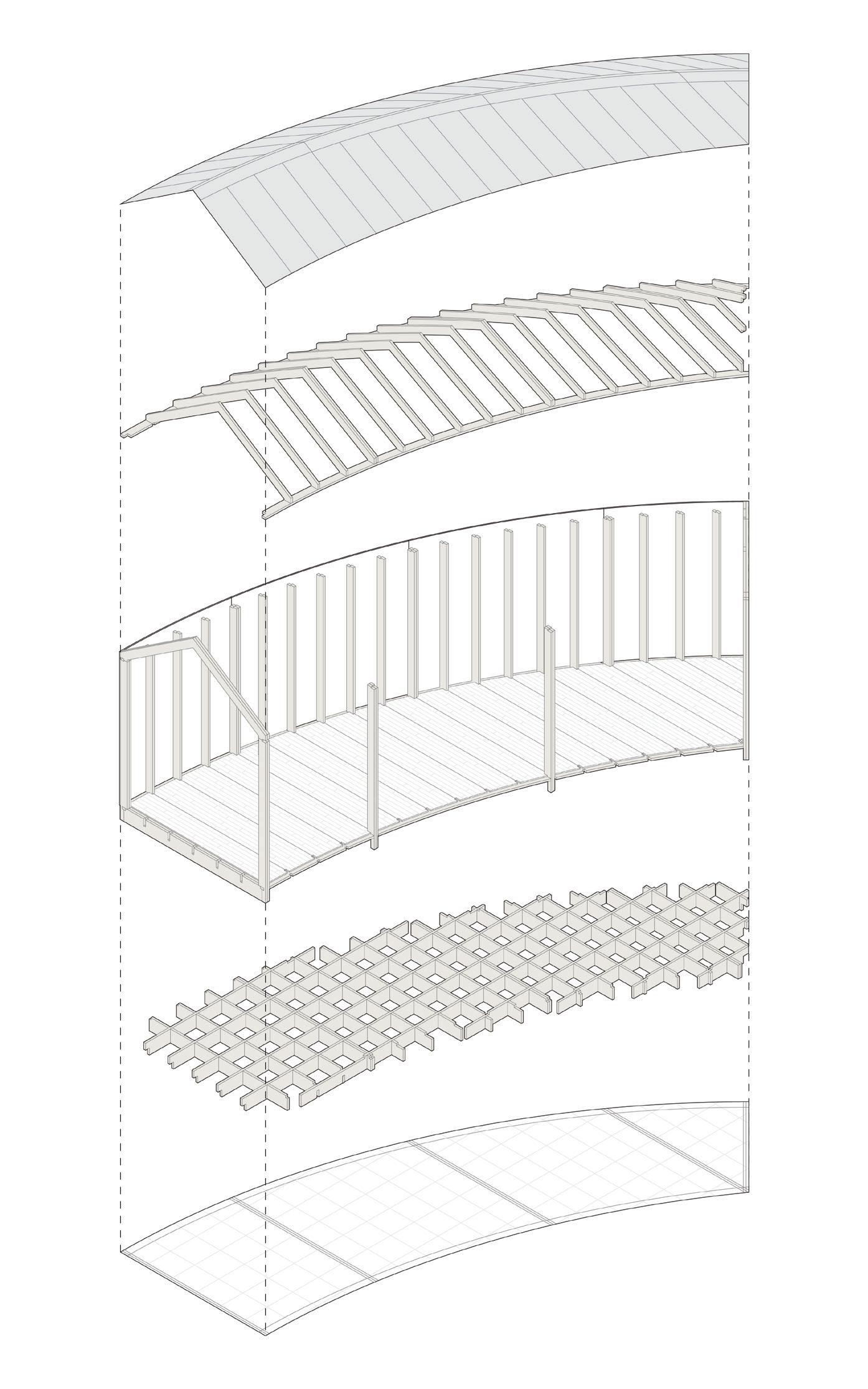

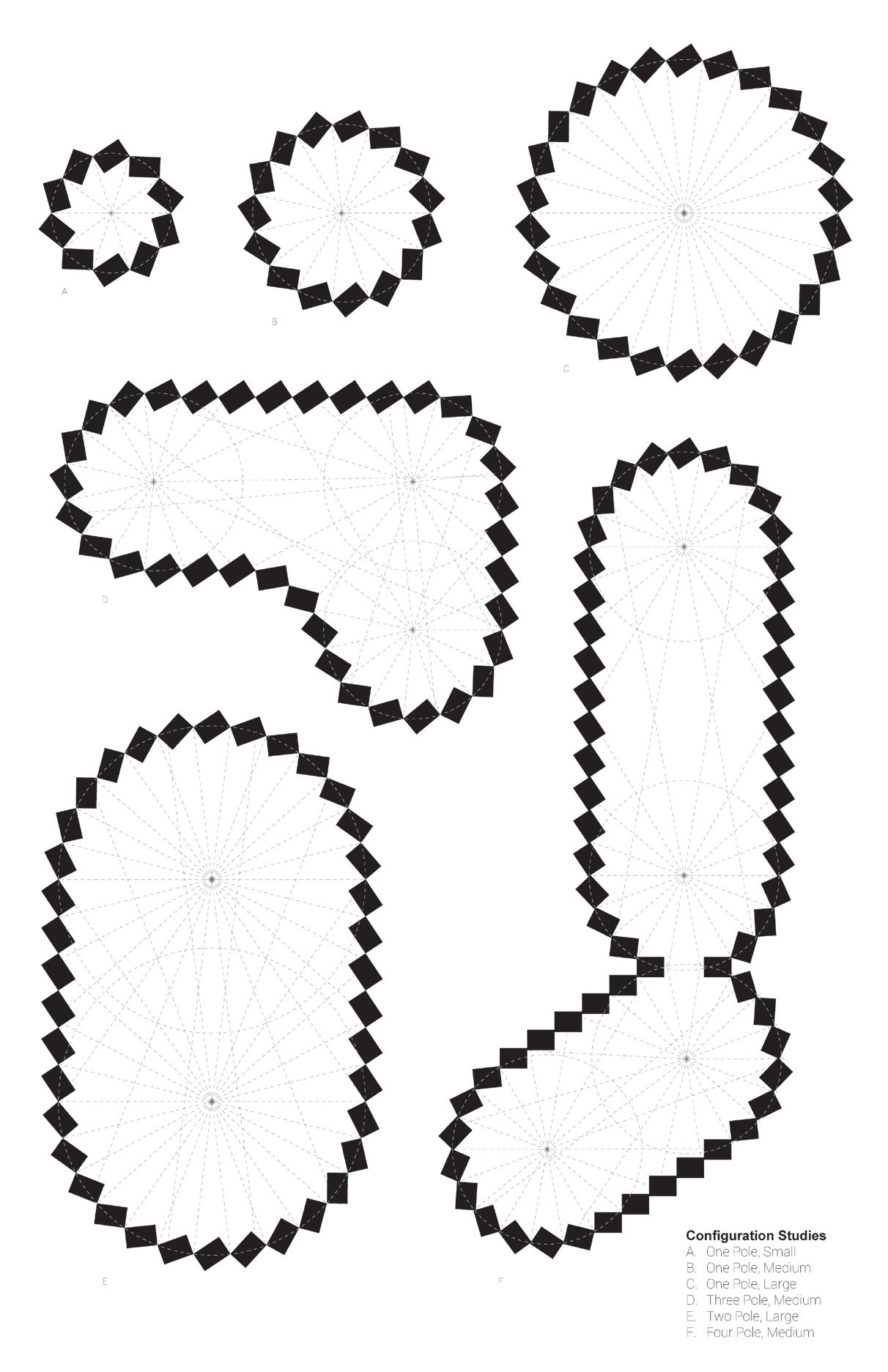

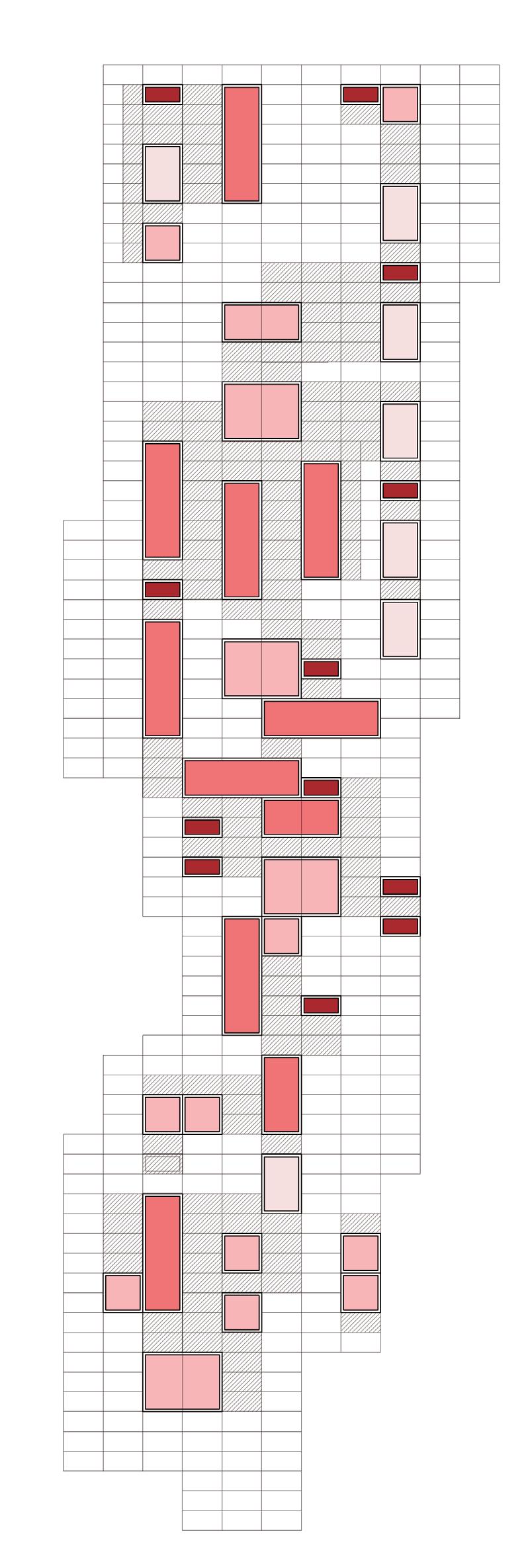

In imagining the future of work, the investigation focused on the notion of expansion. As the demands, scale, and capacity of a given business change, so too do its spatial needs. To facilitate the expansion (or contraction) of the physical footprint of a workplace, a single module which can array, bridge, or tessellate with itself in a variety of configurations while remaining cohesive and novel in its form was designed.

The curvature of the module allows it to geometrically nest with others in plan, allowing for the creation of deep, open volumes. Conversely, the module’s subdivisions allow for partitioning into smaller and medium-sized spaces for offices, meeting rooms, or service areas. Modules can be chained to create corridors between volumes, and a light timber waffle structure enables small spans over natural features, such as brooks, for a minimal impact on the site.

Notched light timber framing provides a durable structural system that can be sustainably sourced, while the façade materials provide a clean aesthetic in keeping with the context of Awaji-Shima. The module’s subdivisions enable simple flatpacked transport and easy assembly, and individual modules can be added or removed and recycled over the lifetime of an office.

Above: Derivation of the curve

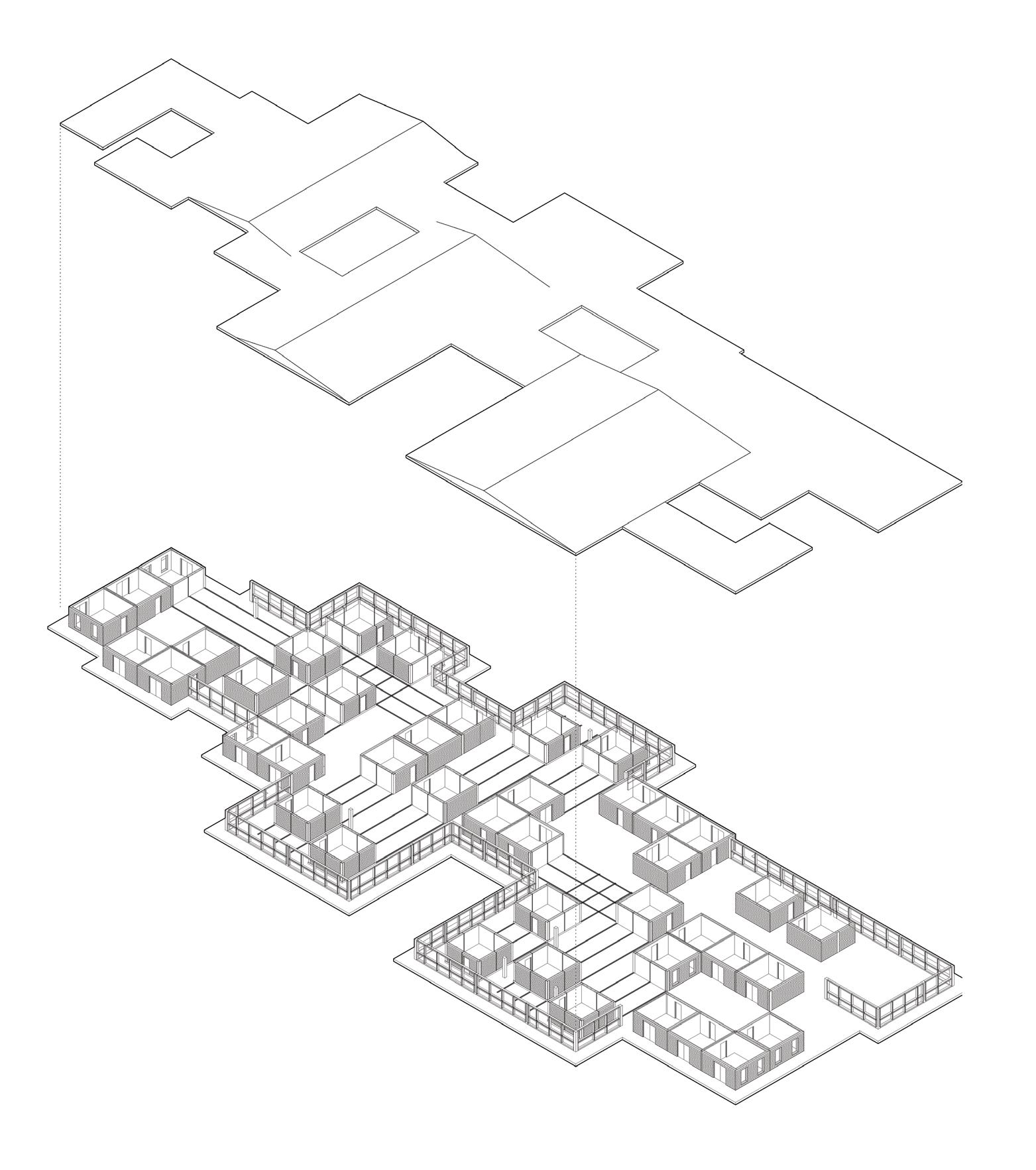

Previous page: Exploded axonomteric showing constructiton compoments and skeletal isomteric of the aggregated form

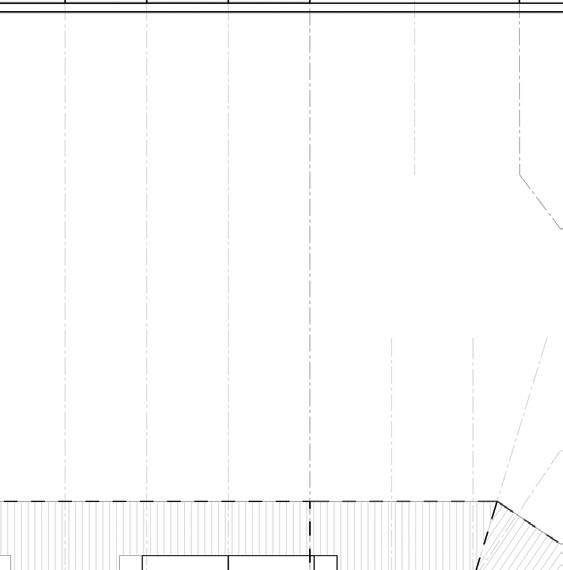

Above: Proposed plans, sections and elevations

Above: Exploded axonometric showing levels and details of construction

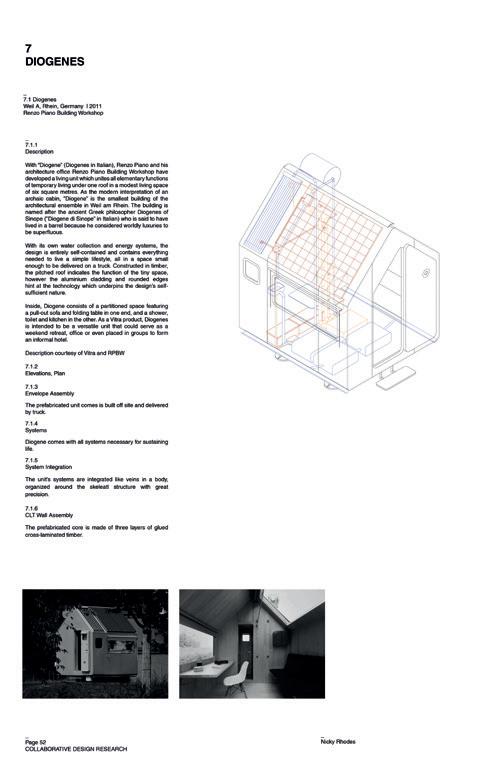

Nicky Rhodes

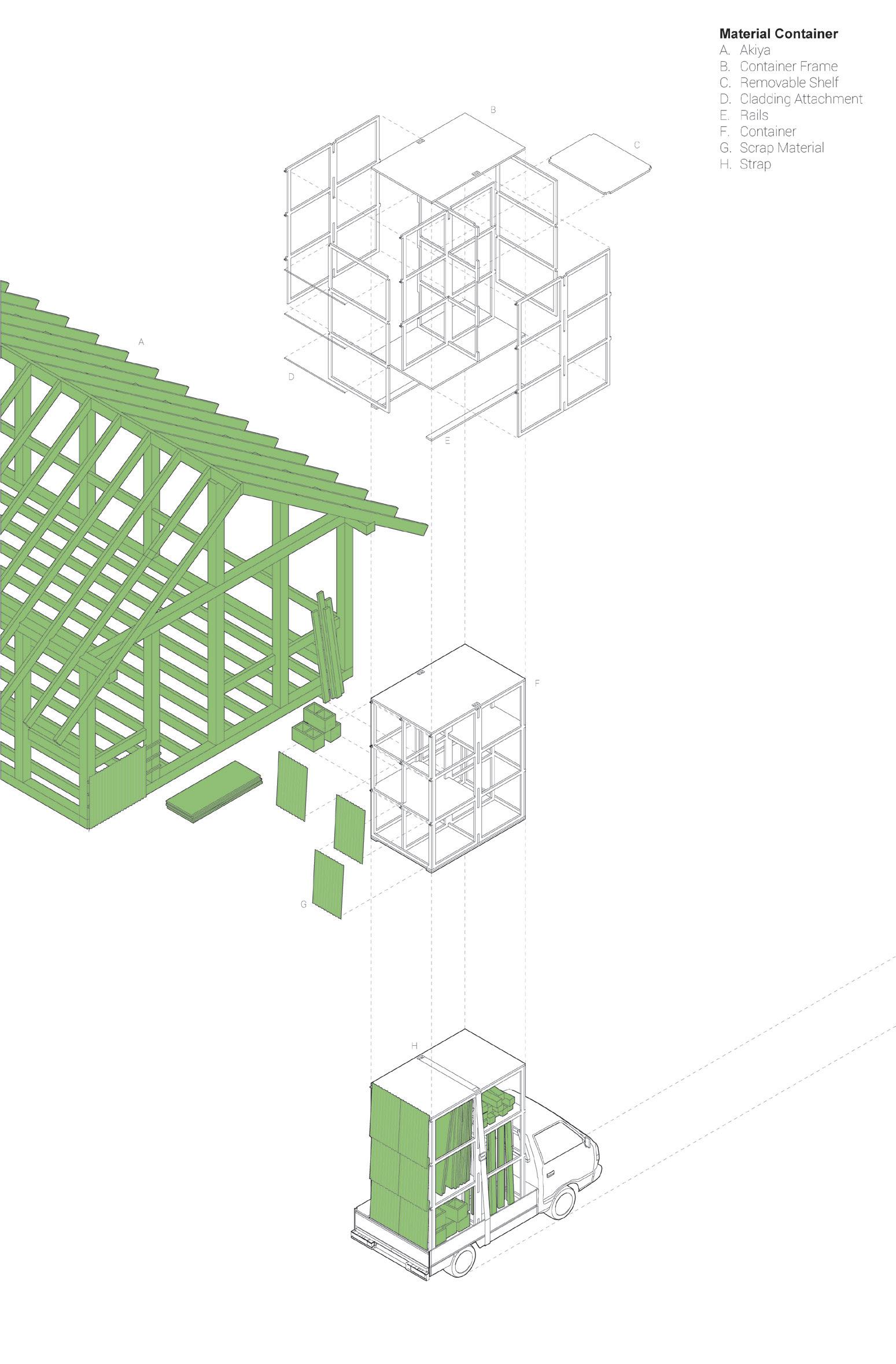

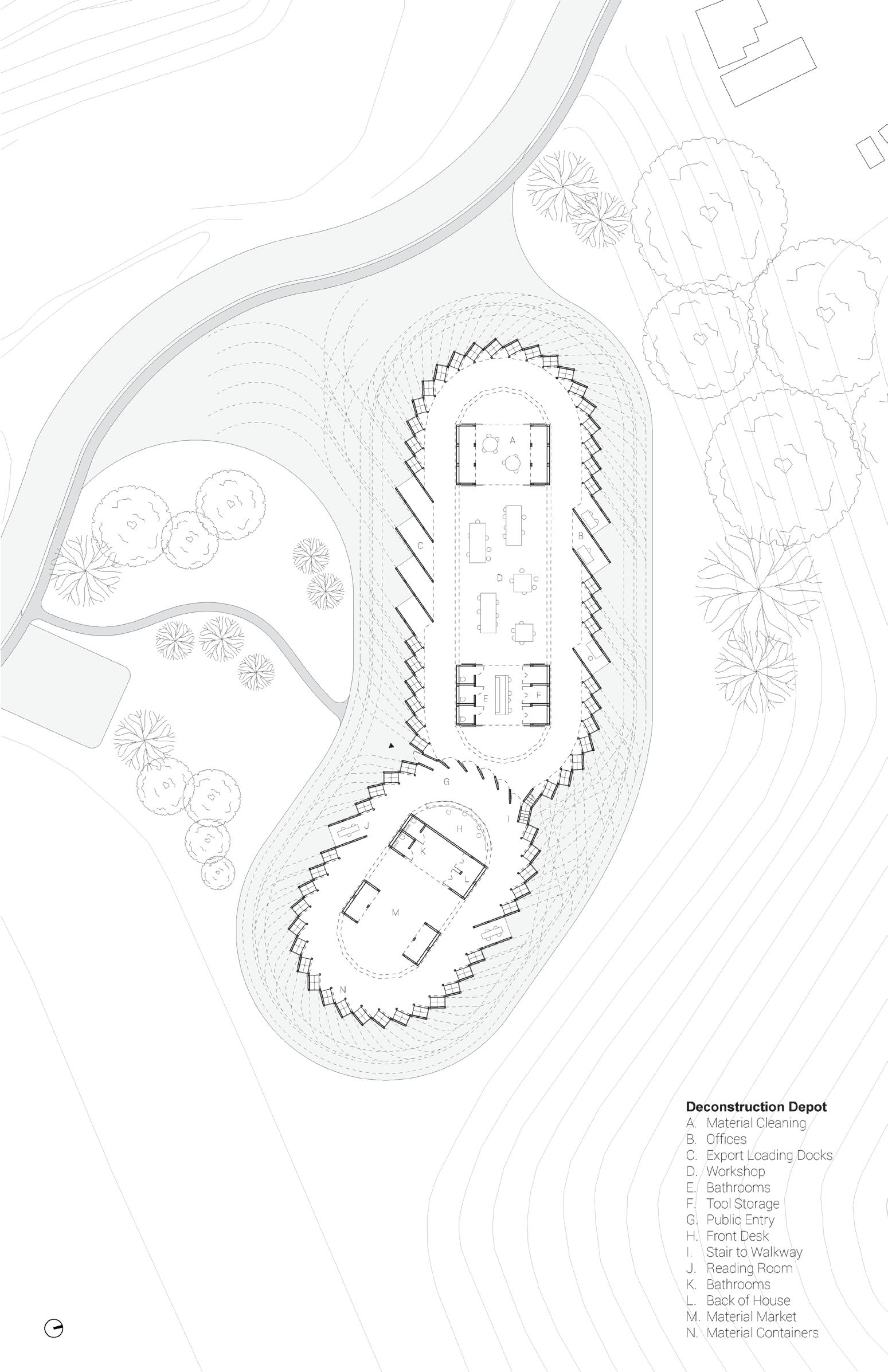

Awaji, like much of rural Japan, faces steep population decline as people migrate to cities like nearby Osaka, leaving behind a growing number of vacant homes known as akiyas. With little demand and high maintenance costs, many of these buildings sit abandoned and decaying, reinforcing a cycle of exodus. While the government tracks akiyas to encourage reinvestment, often by outside speculators, these empty structures may also represent a hidden abundance of material and cultural heritage, rather than just loss.

Japan has a long tradition of deconstructible architecture, where buildings were designed for multiple lifespans through joinery and pegging. This legacy continues in advanced deconstruction systems that salvage up to 90% of materials, even generating energy in the process. In Awaji’s Asanokanda district, signs of productive life persist, local industry thrives with cement plants, ironworks, and fisheries. Kei trucks and utilitarian materials—corrugated metal, timber, and concrete—reflect a resilient working culture and textured landscape shaped by labor.

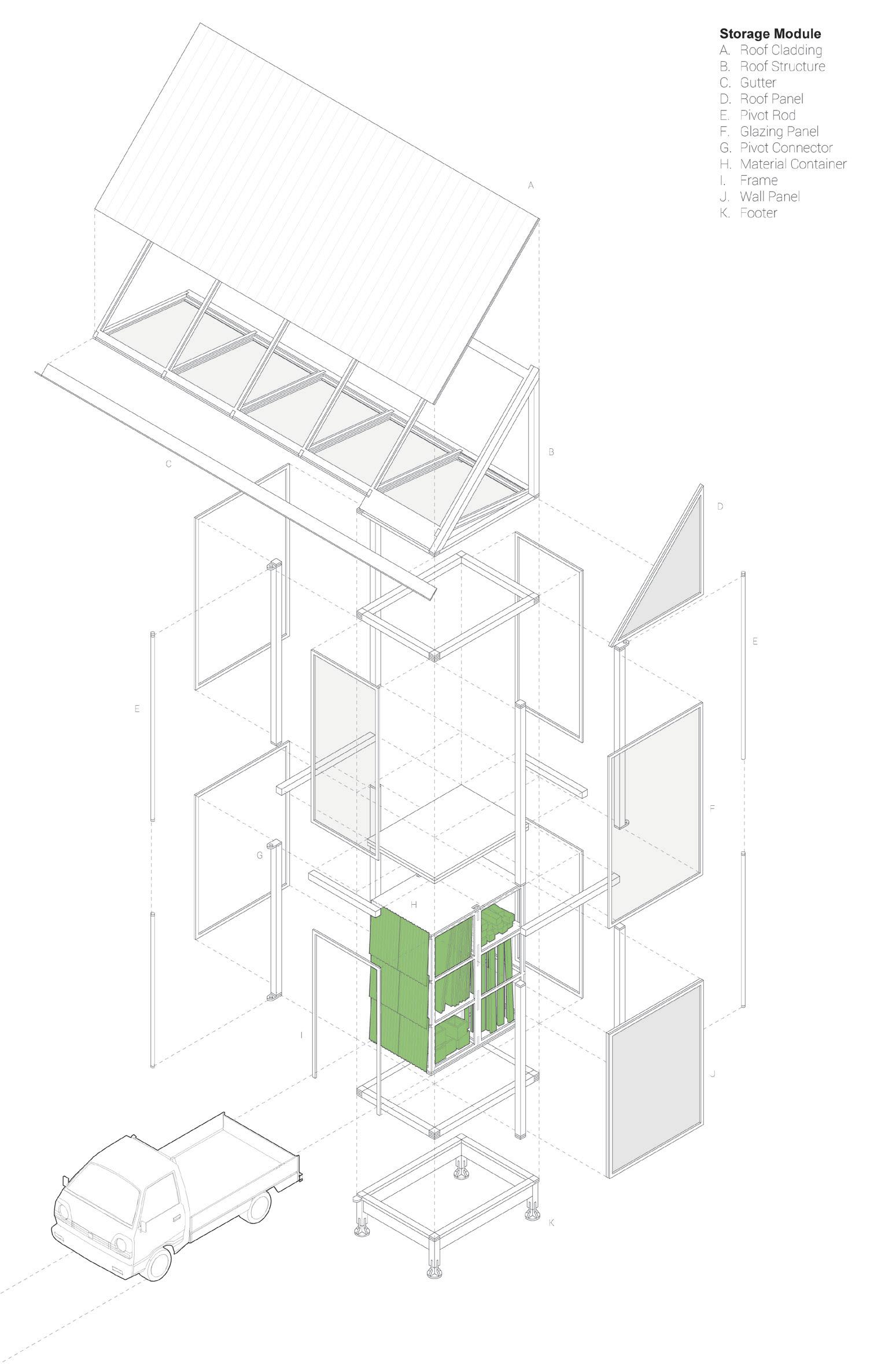

The Deconstruction Depot is a mobile, modular system rooted in the reuse of materials from abandoned akiyas across rural Japan. Using the kei truck’s 4x6 ft bed as a standardized “tatami” unit, materials are gathered and delivered to a purpose-built depot dock, designed to the truck’s turning radius. Inspired by the Toyota Production System, the depot stores reclaimed materials around its perimeter as a living archive. Inside, a pivot-based modular system transforms them into bespoke furniture, while elevated walkways invite public engagement. The structure itself can be disassembled and relocated, continuing the cycle of thoughtful, place-based reuse.

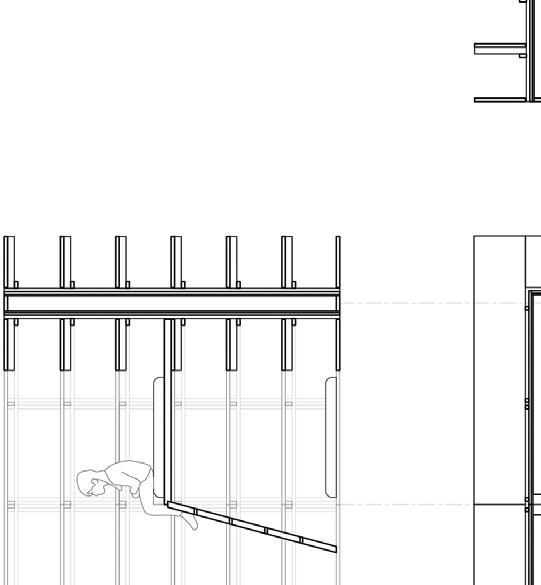

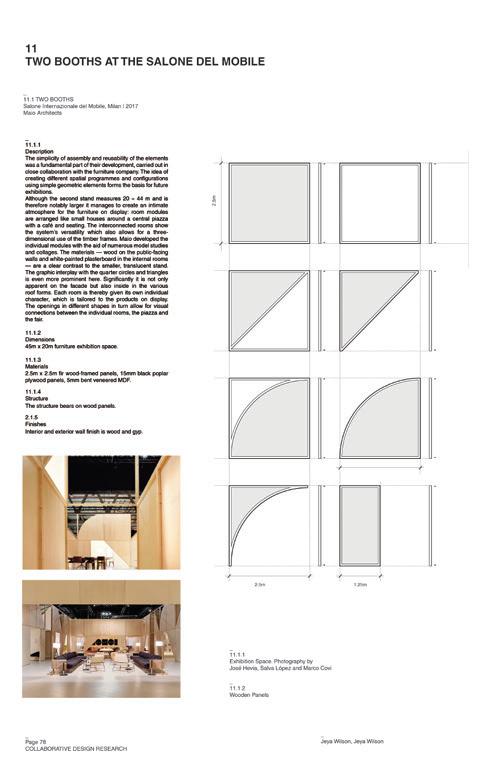

Jeya Wilson

For the millions of residents living across the straight in the great agglomeration of Kobe and Osaka, Awaji offers a uniquely desirable recreational destination. The hospitality sector of the island is one of the largest employers of seasonal workers.

As the working population of Awaji flows and ebbs with the seasons, there is a need for a type of space that contracts or expands according to seasonal demand.

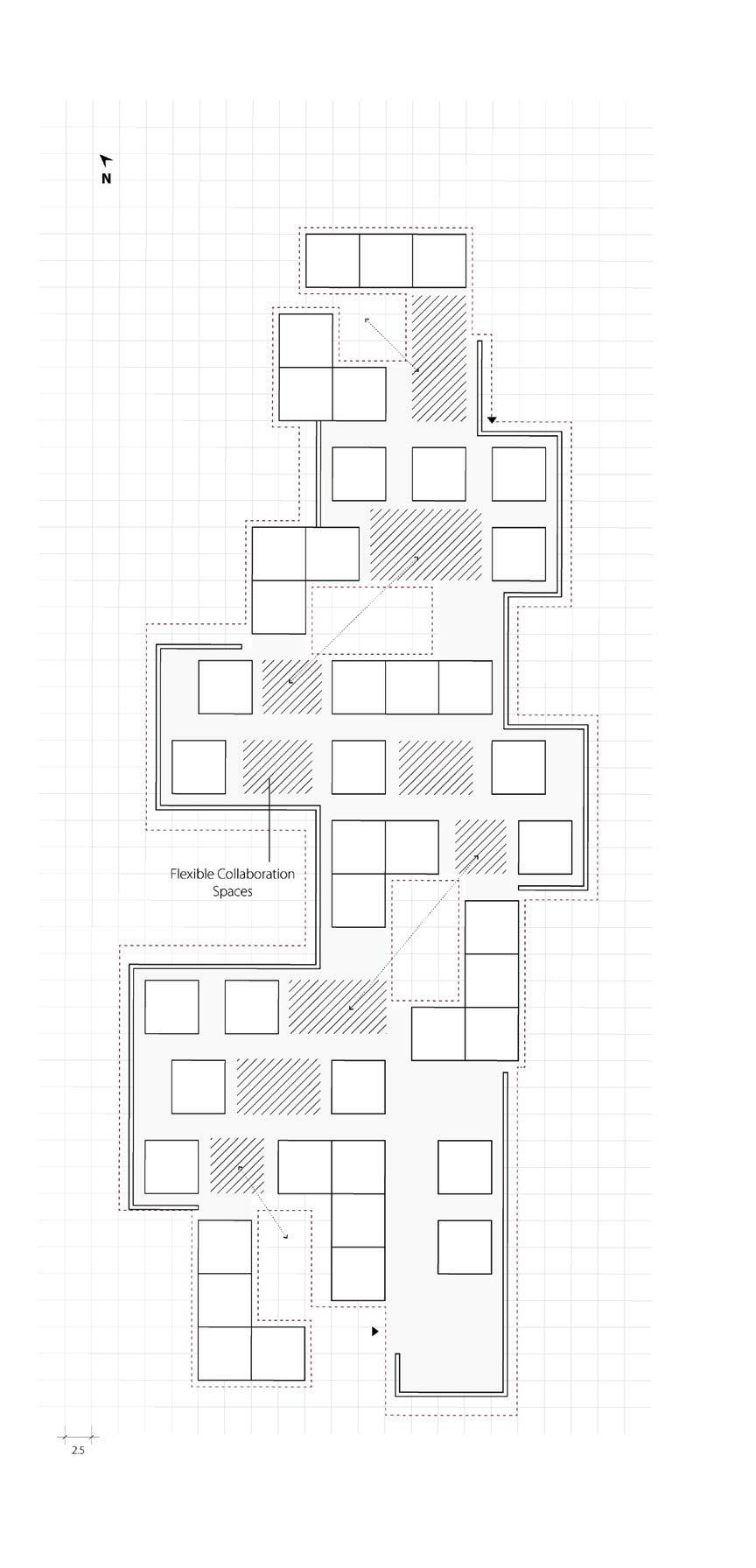

This proposal explores the possibility of a large communal facility planned around the twin principles of modular interior reconfiguration, and horizontal expansion. In this proposal, flexibility is king.

The facility expands over time by aggregating clusters of rooms around patios. The function of the rooms adapts to accommodate the variable patterns of occupation. This is done by reconfiguring the partitions between adjacent spaces, or by moving around some of the rooms themselves, thanks to a bespoke system of internal tracks.

Eventually, the facility will reach its optimal size according to use.

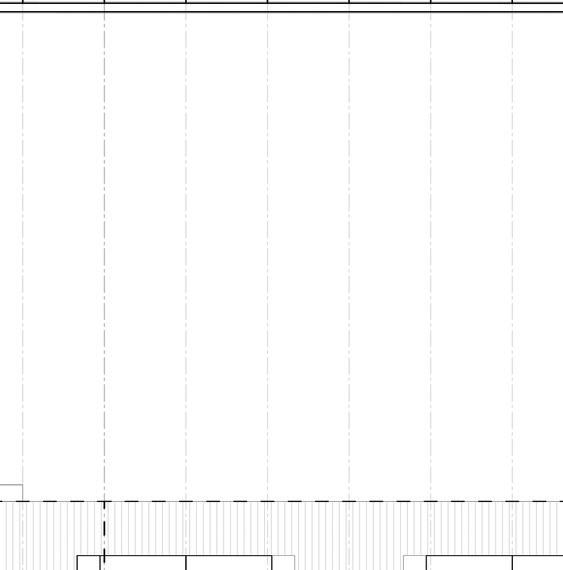

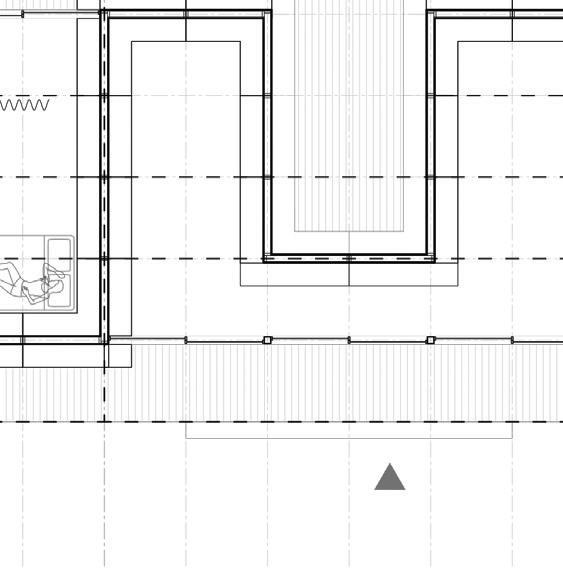

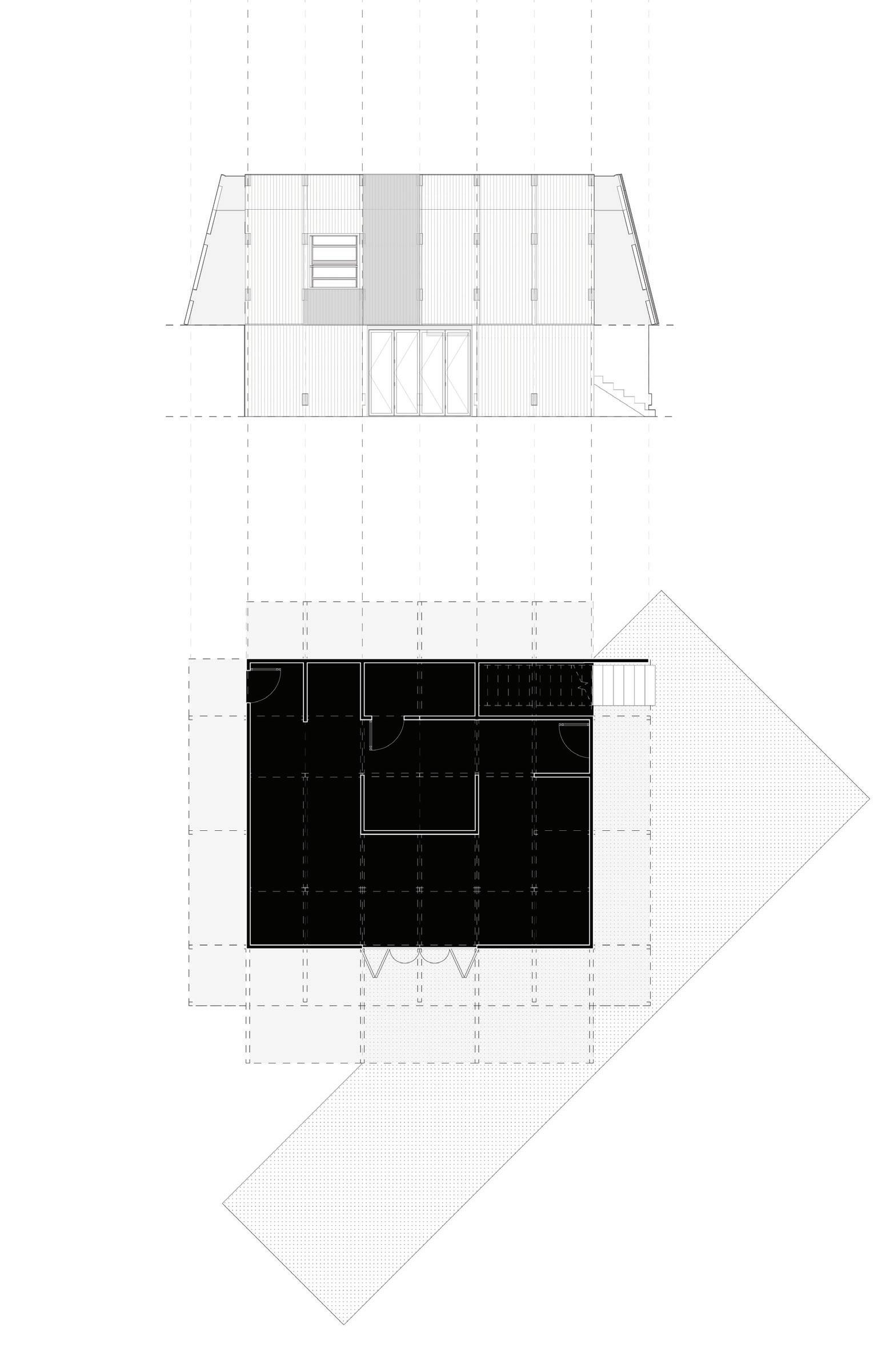

Floor plans showing operability of spaces in massing and program adjacencies during off-season

nologies

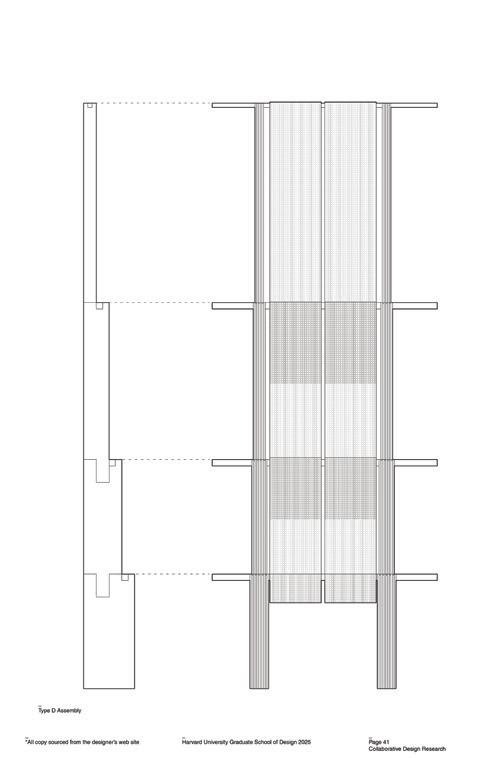

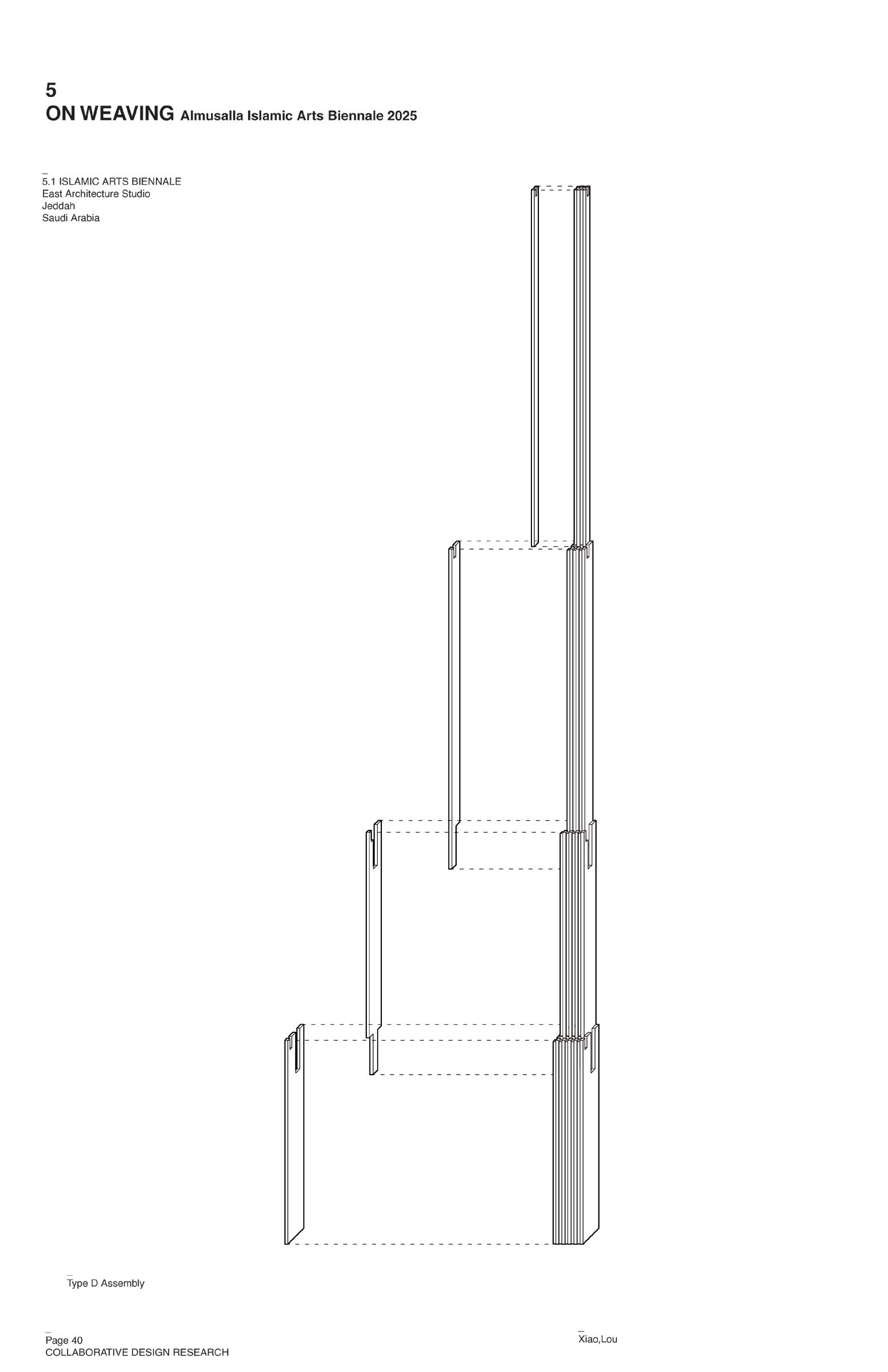

Lou Xiao

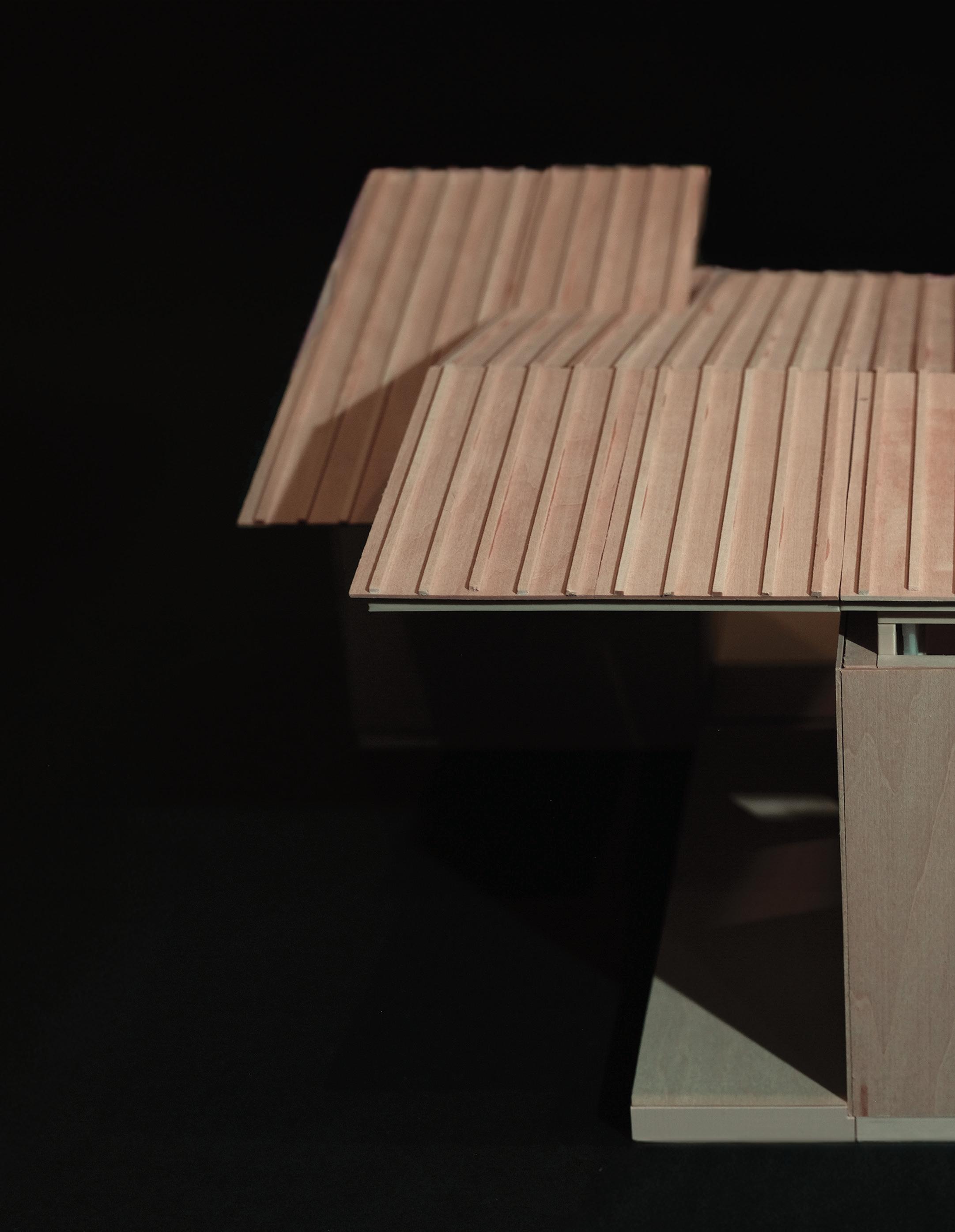

Set gently into the terraced slopes of Awaji Island, this modular wooden architecture gathers time, wind, and labor beneath its evolving canopy.

Framed in timber joints and tuned to the rhythm of citrus seasons, the structure breathes through shifting apertures and layered eaves.

Neither static shelter nor fixed program, it constitutes a scaffold for seasonal life—a place where work, rest, and weather meet in quiet negotiation.

As the light moves and the frames age, architecture becomes a trace of lived cycles.

Rest

Previous page: Design logic of the roofs Top: Programming adjacancies

Type F module assembly procedure

Ella Larkin

This project begins with an analysis of Awaji and its relationship to the fishing community. Historically, Awaji has supported a large portion of Japan’s fishing industry. In particular, Asano was the original location for the creation of the Sashiko Ko Donka—translated as “stitch-small-work coat.” The intricacies of these coats—layering, stitching—became an early tool for analyzing Asano. There was an inherent patchwork quality in the built environment; materials felt stitched and overlaid.

Though these coats are no longer worn, they represent the cultural importance of fishing in Asano. Today, the industry is in decline, affected by climate change and environmental degradation. Located along the Seto Inland Sea, Asano has experienced increased red tides since rapid industrialization in the 1970s— harmful algae blooms that disrupt fish populations. Combined with shifting migration patterns, this has altered the seasonality of fishing.

The Japanese fisherperson has become endangered: from nearly three million a century ago to just 220,000 today—only 3% of whom are under 25. As the industry shrinks, invaluable knowledge is at risk of being lost. Asano’s experience could become essential to fisher communities elsewhere.

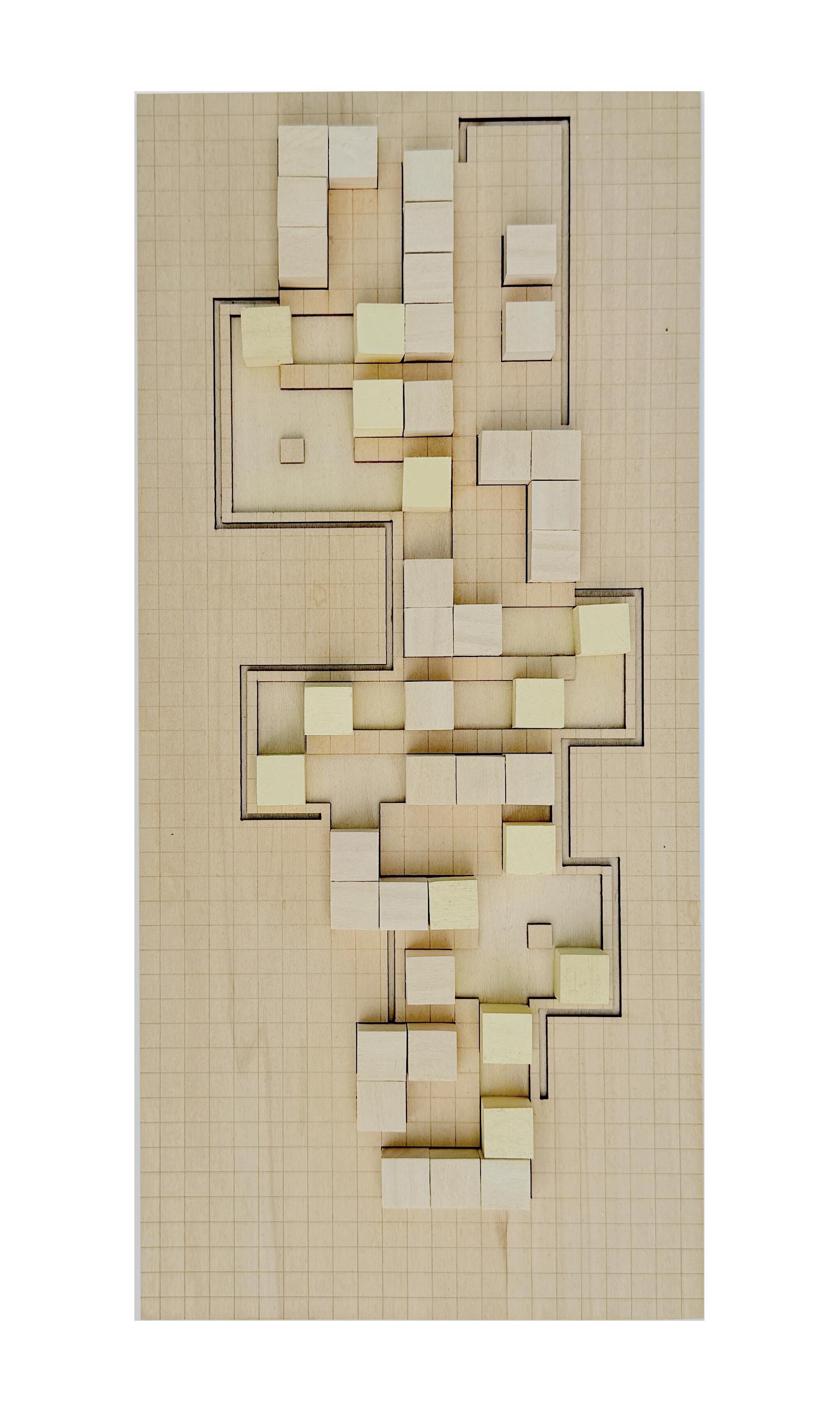

This project proposes a living archive that preserves existing knowledge while collecting new information through research. Small modules are deployed that adapt to seasonal needs. Working within a piece-to-whole logic, the modules scale from a 5x5 ft square up to 15 ft. Initially volumetric, the modules were pruned—walls selectively removed—to enable reconfiguration into archives, labs, and living spaces.

Across: Module typolgies and their assembly and transportation

Across: Module typolgies and their assembly

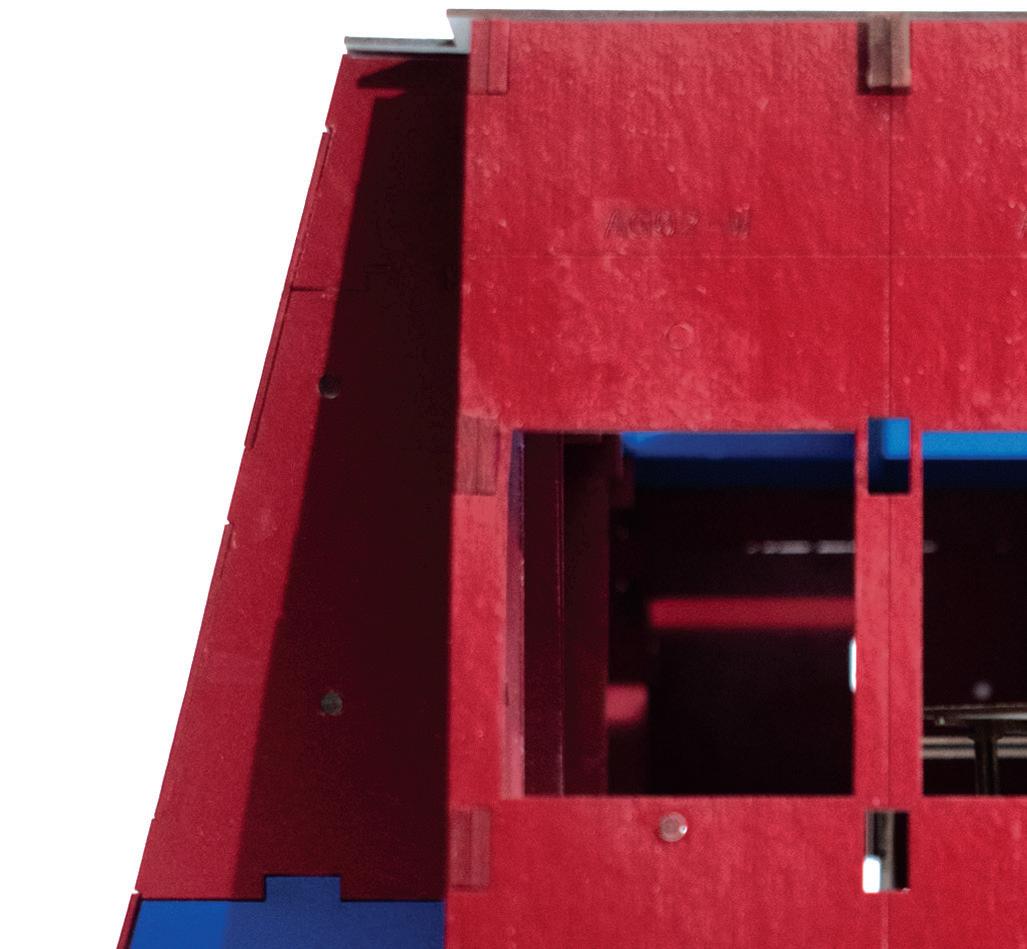

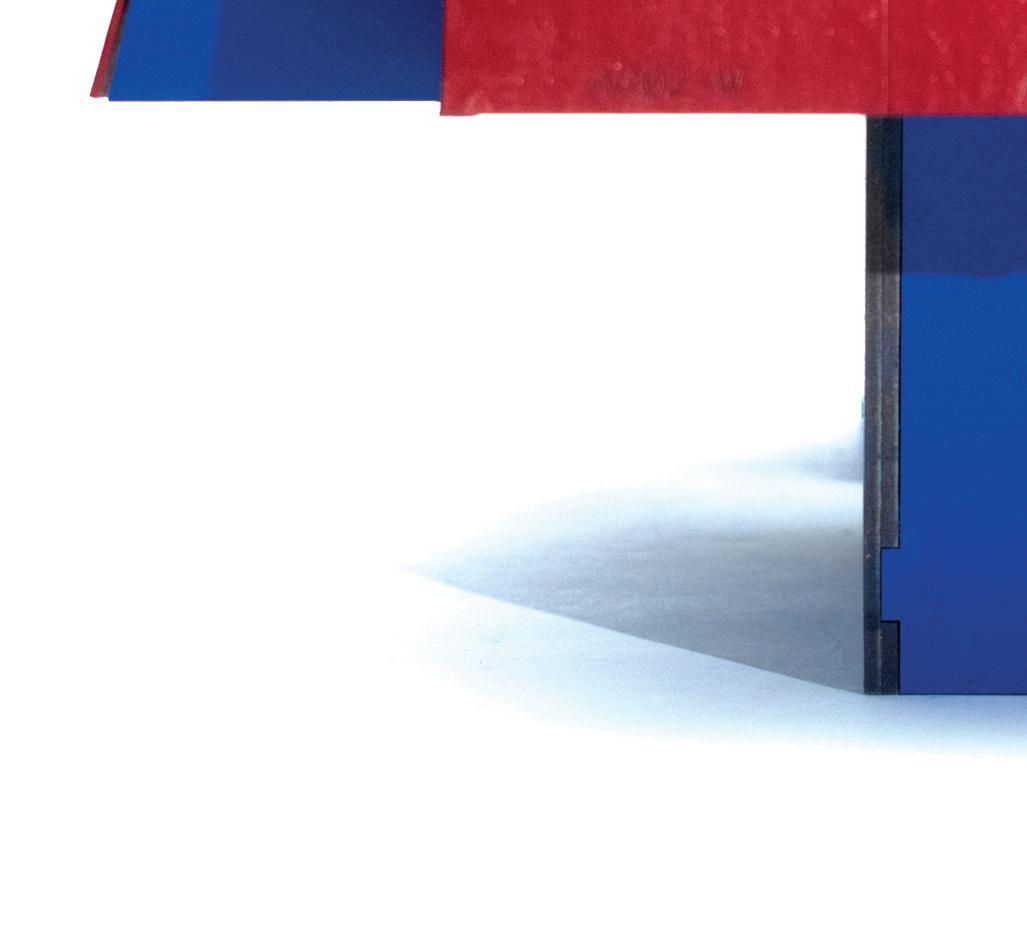

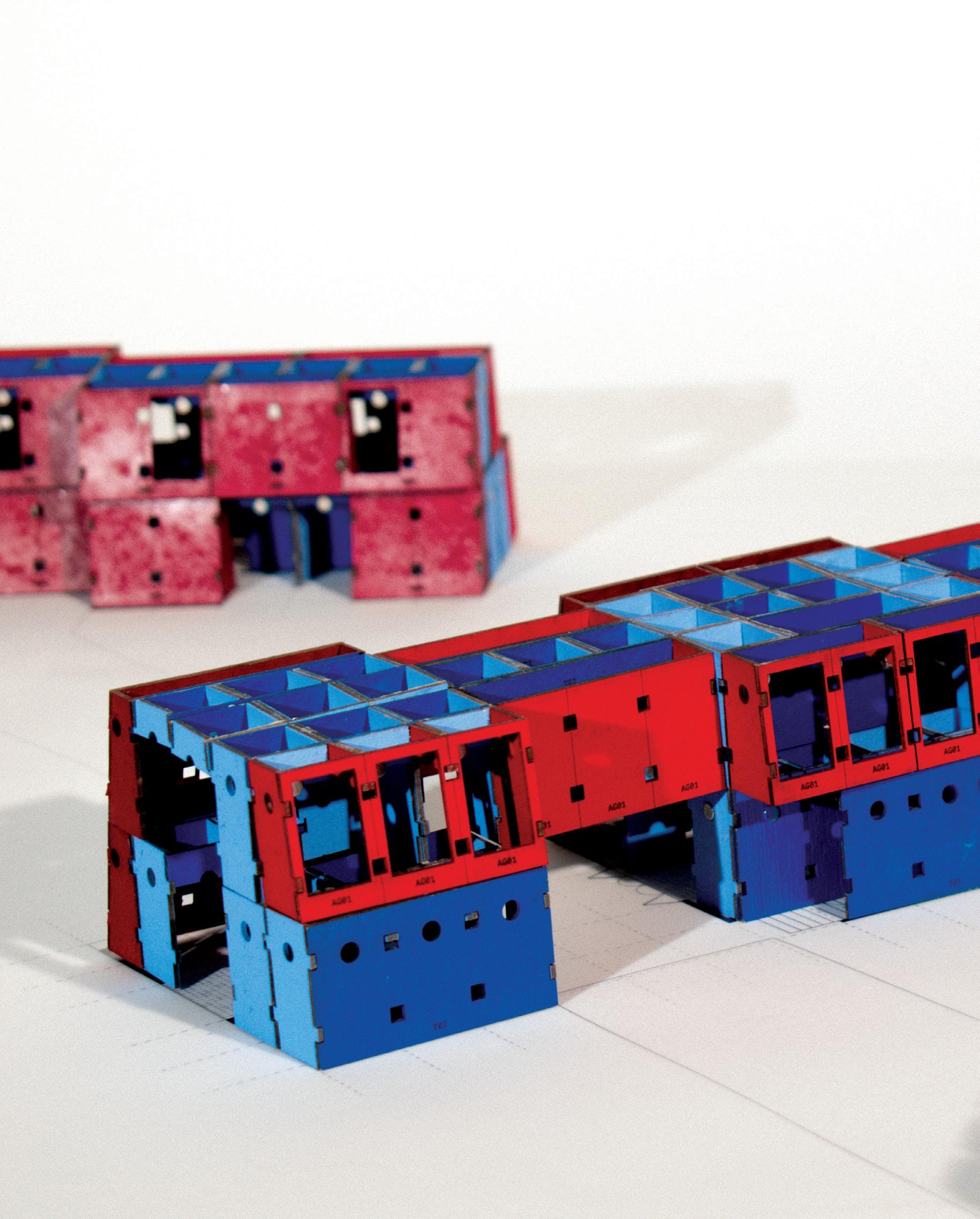

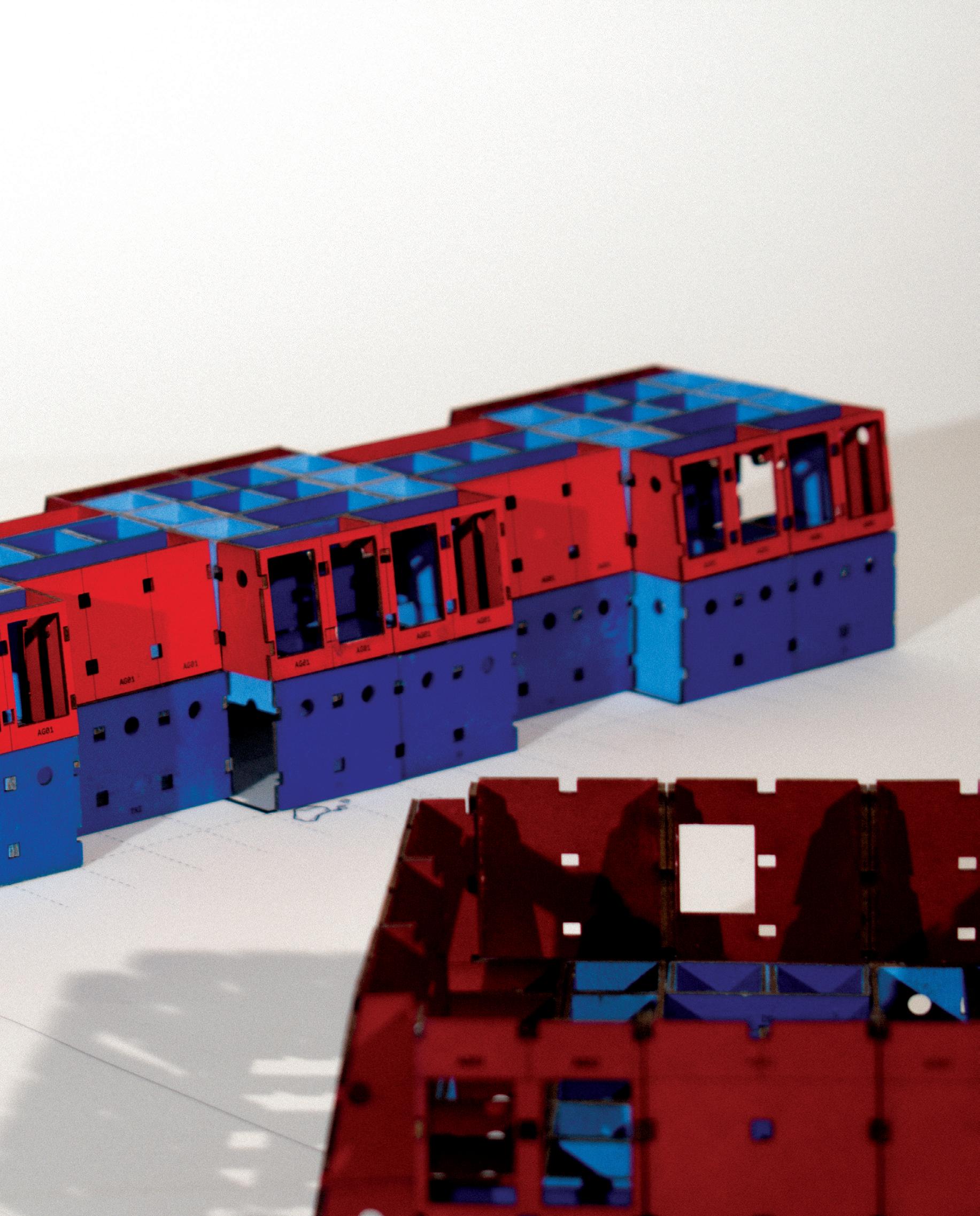

Across: Model exploration built form and aggregation through OSM

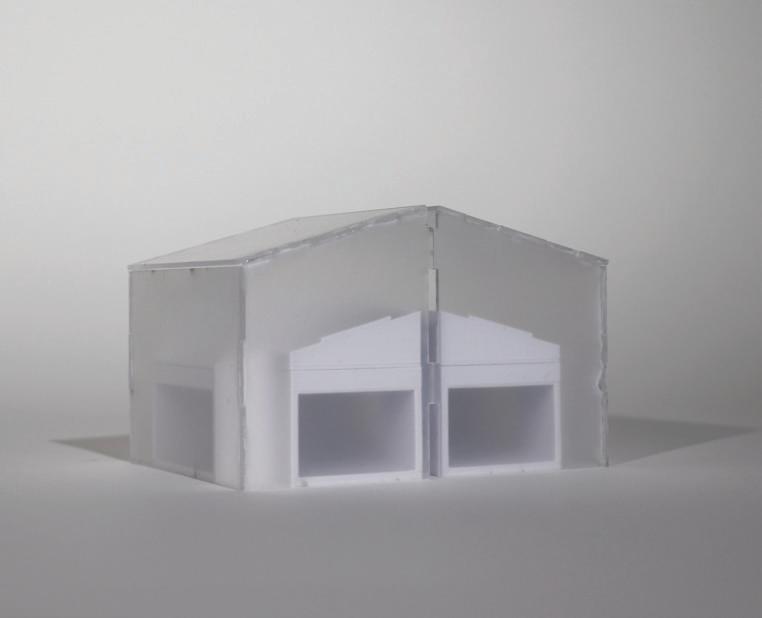

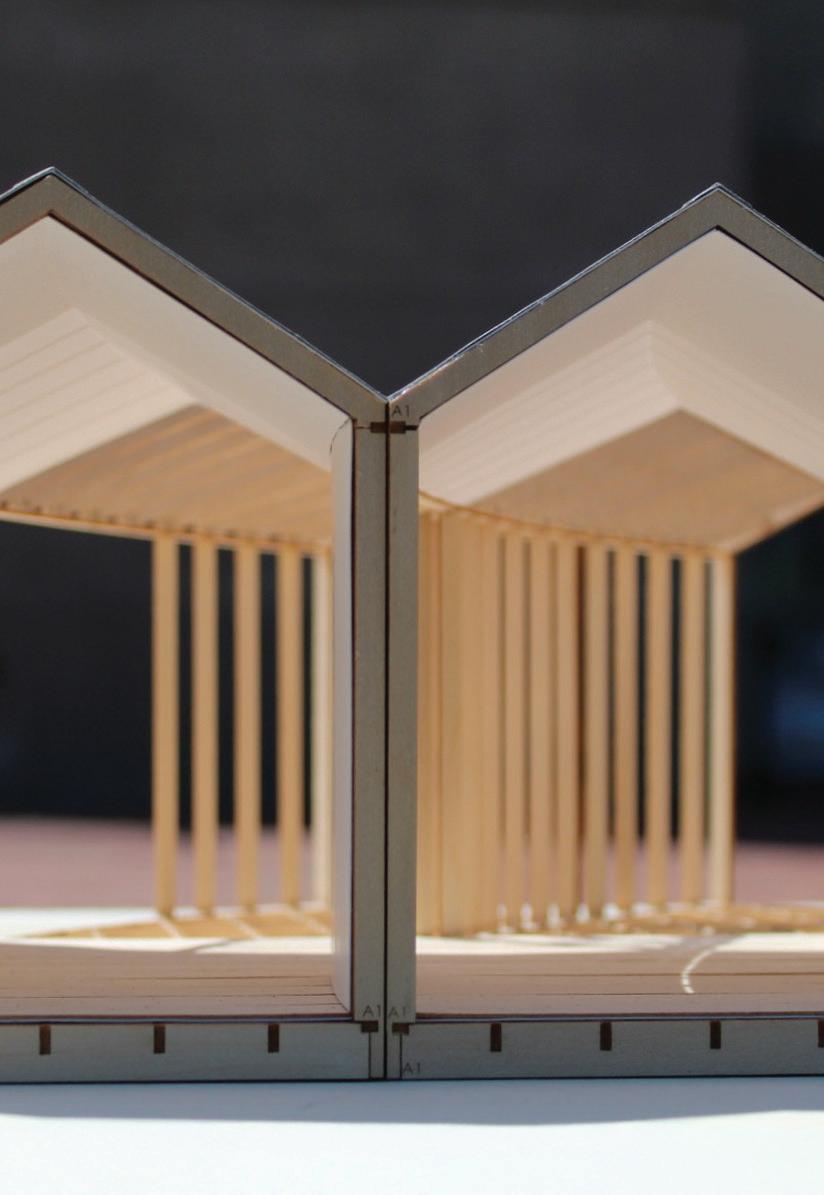

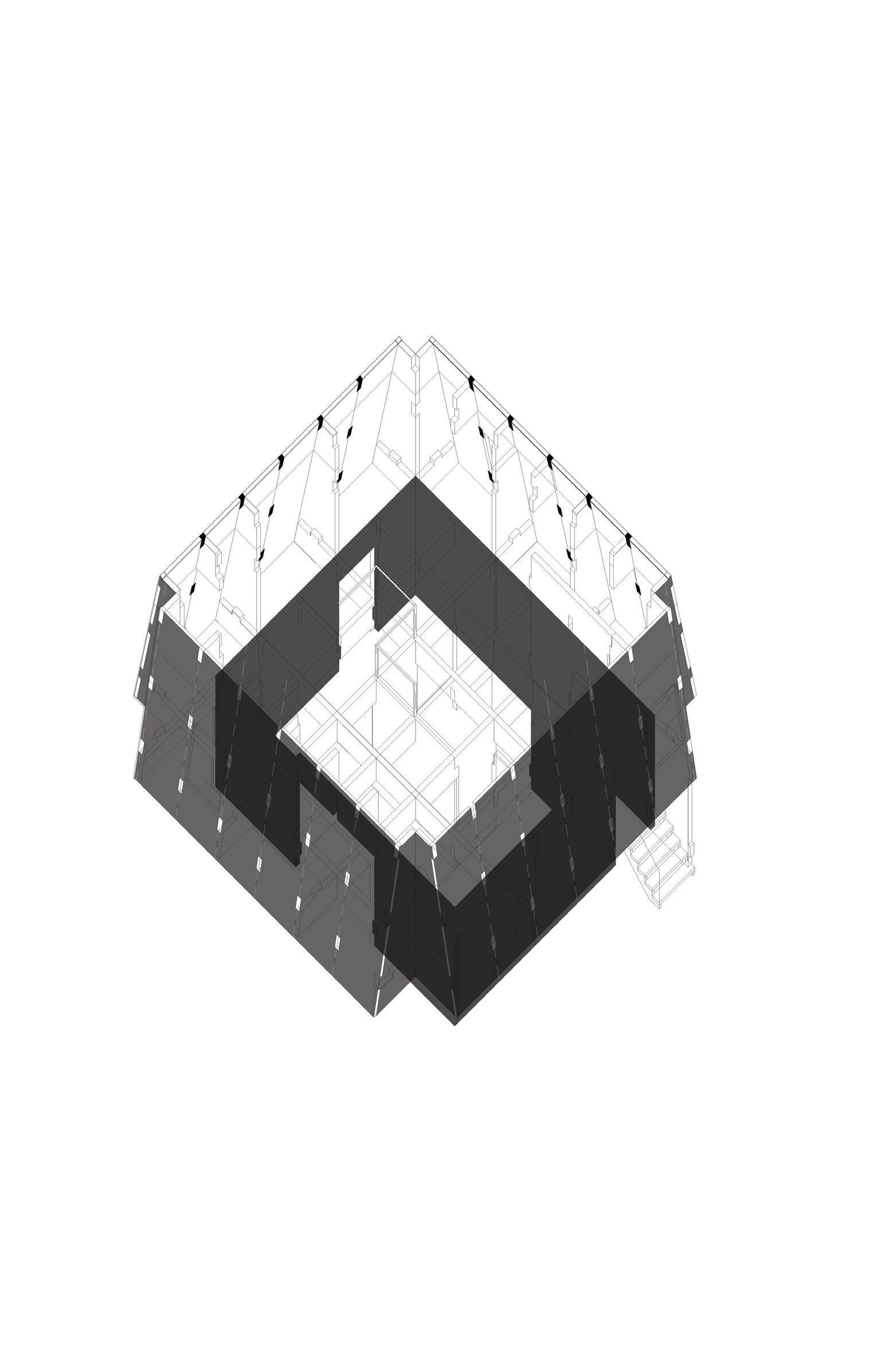

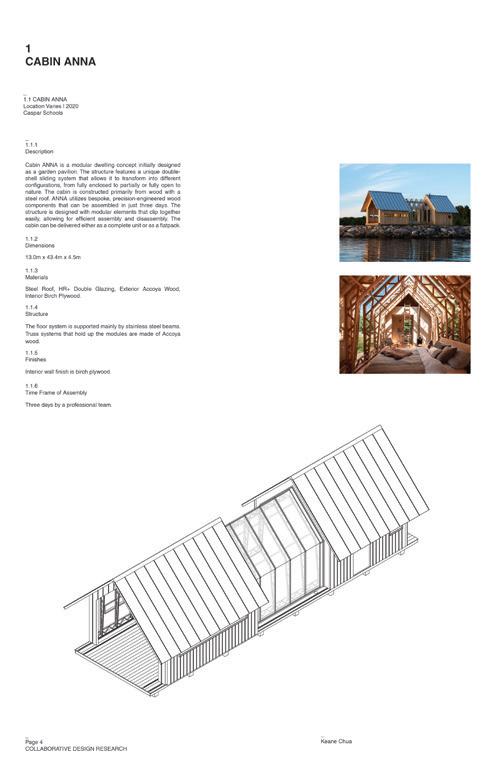

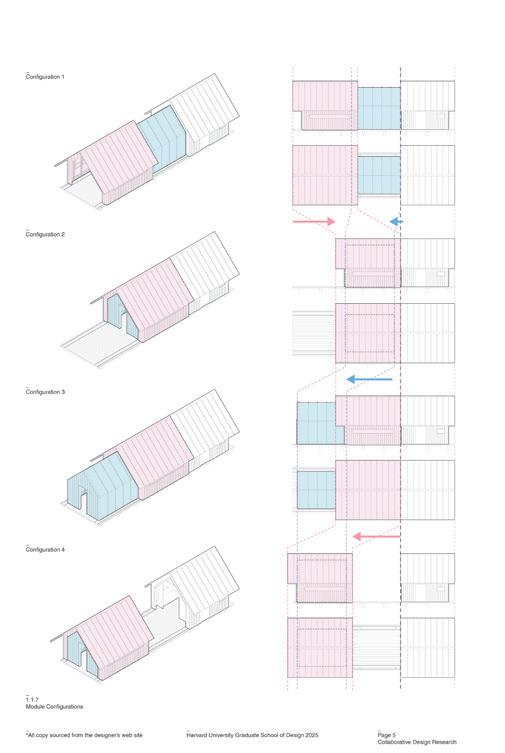

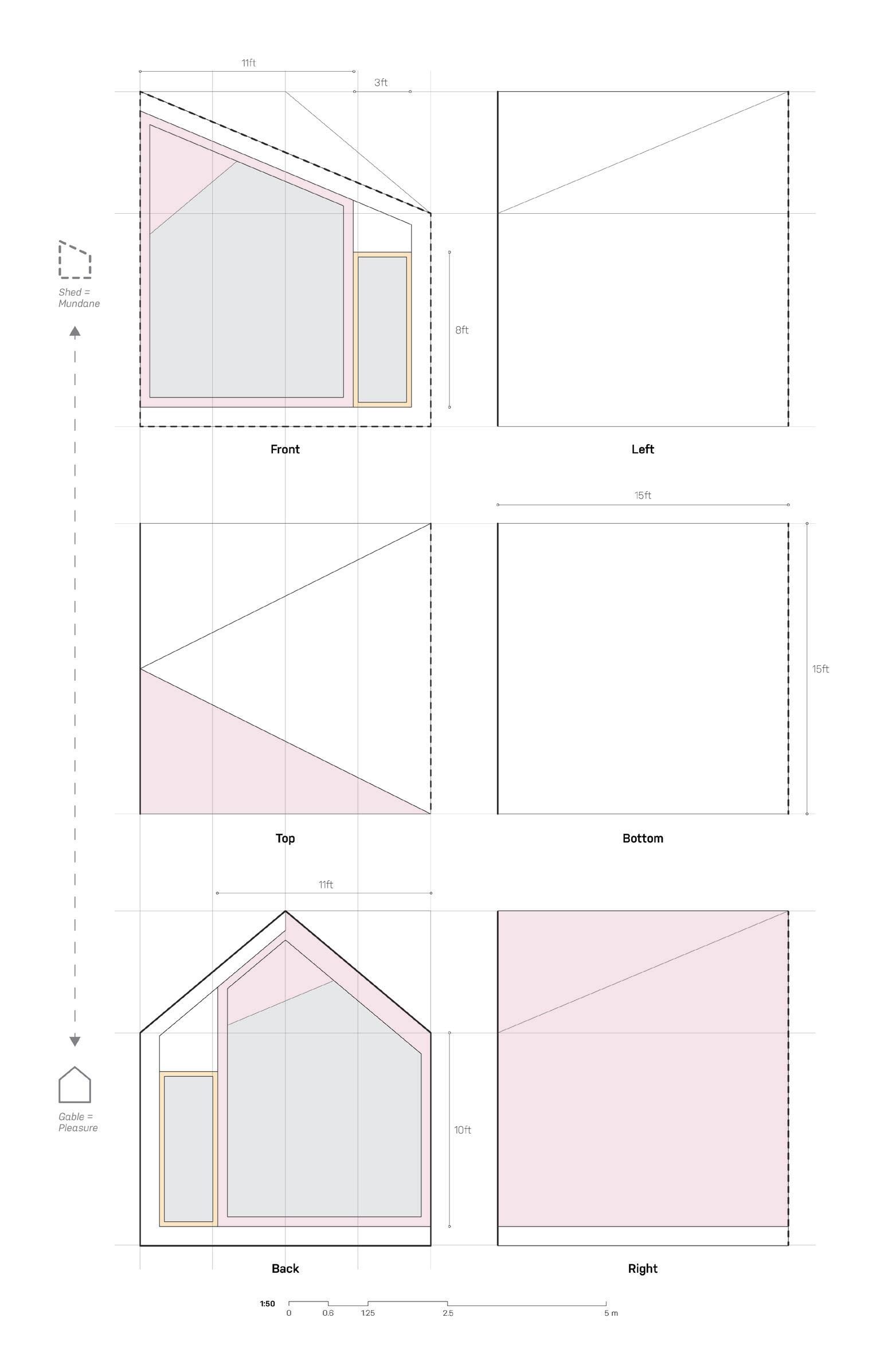

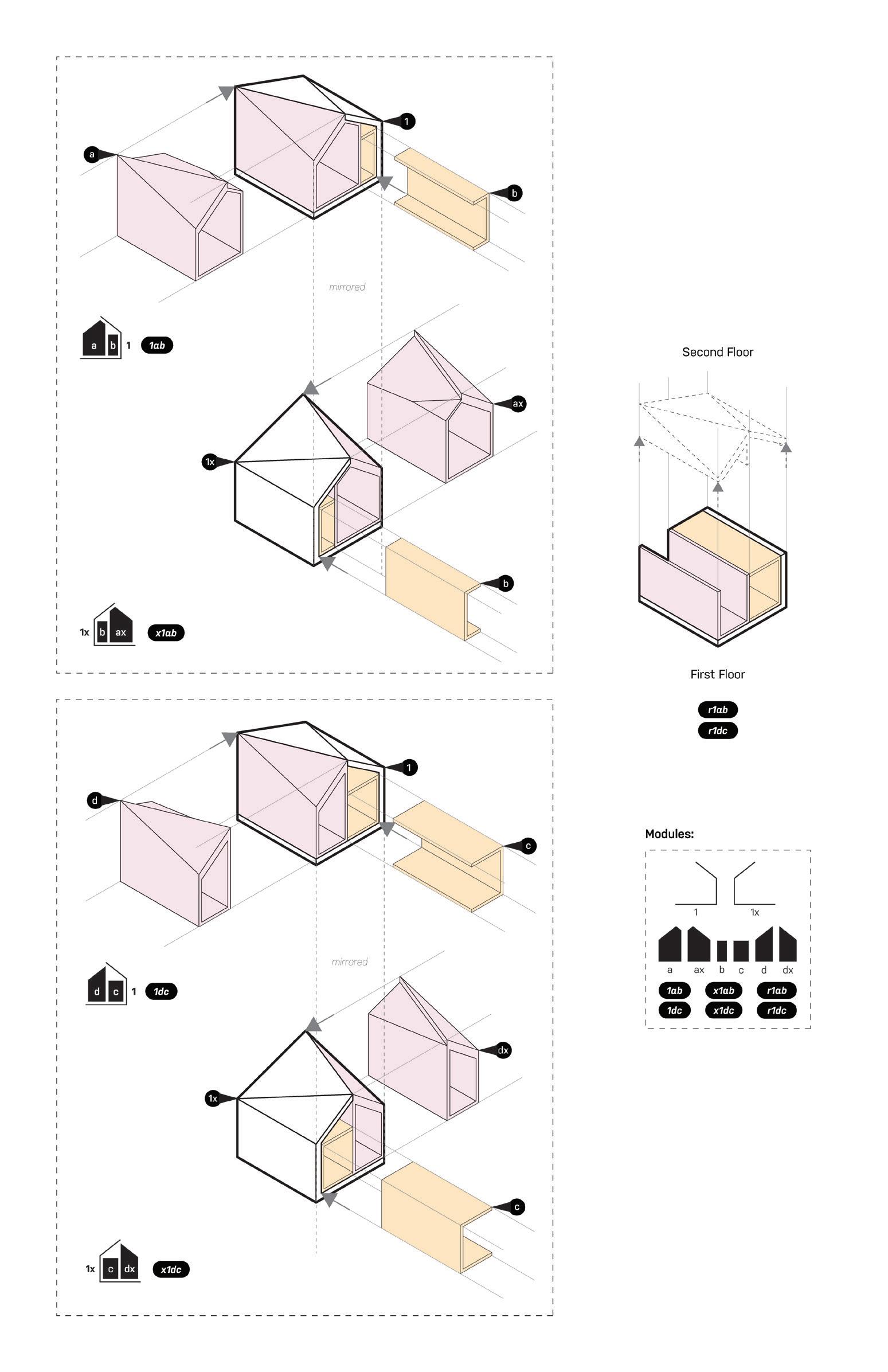

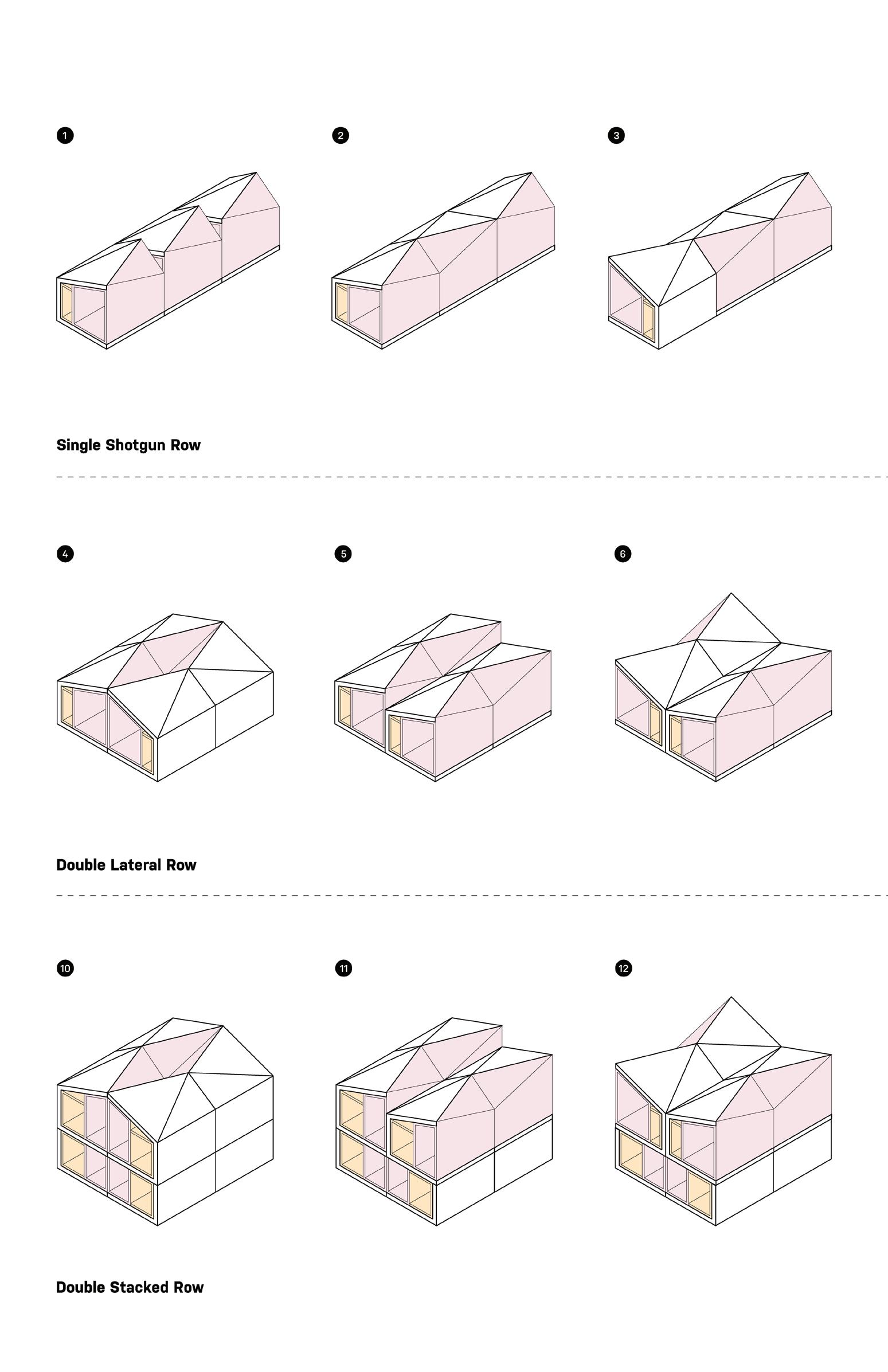

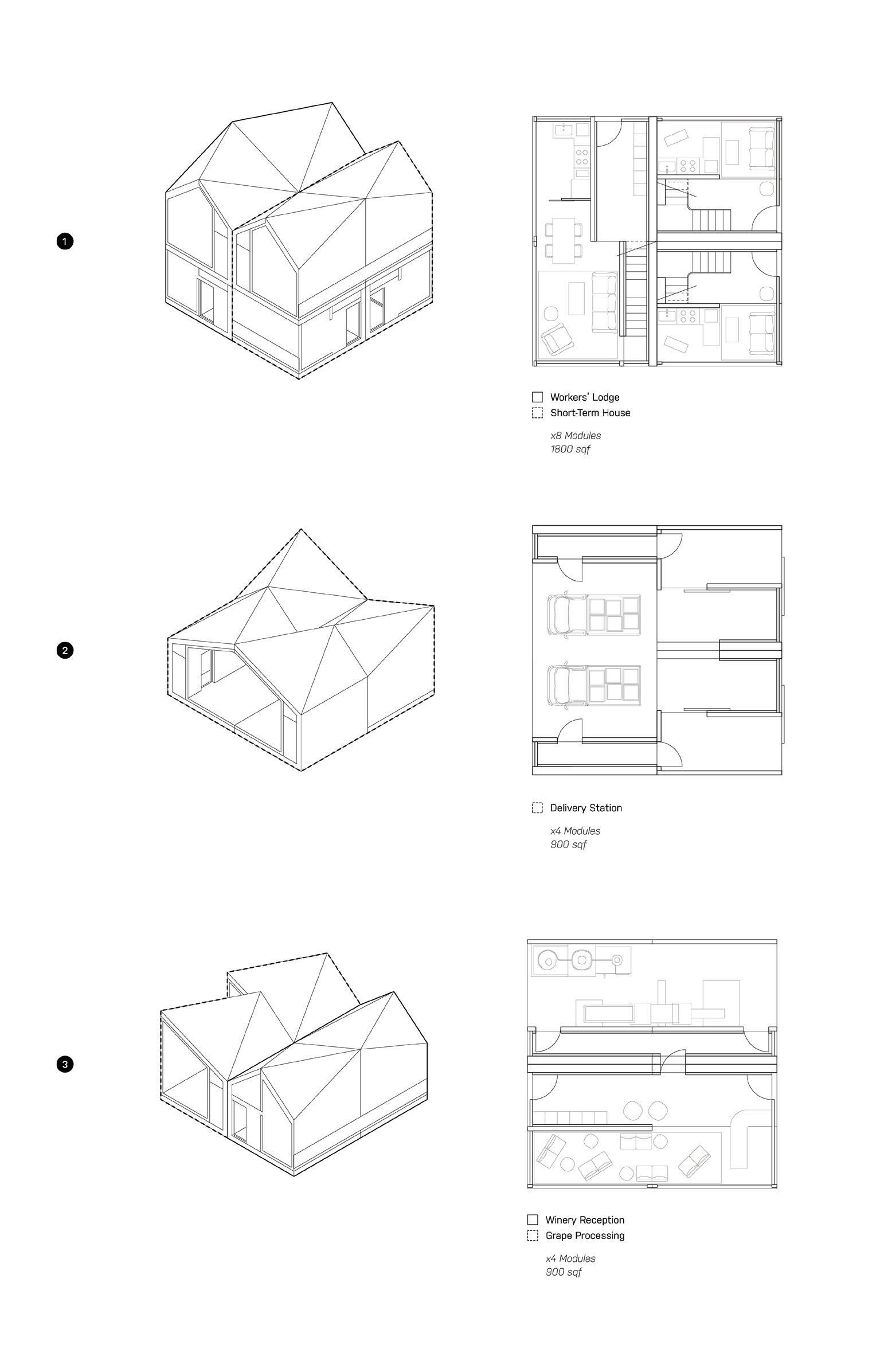

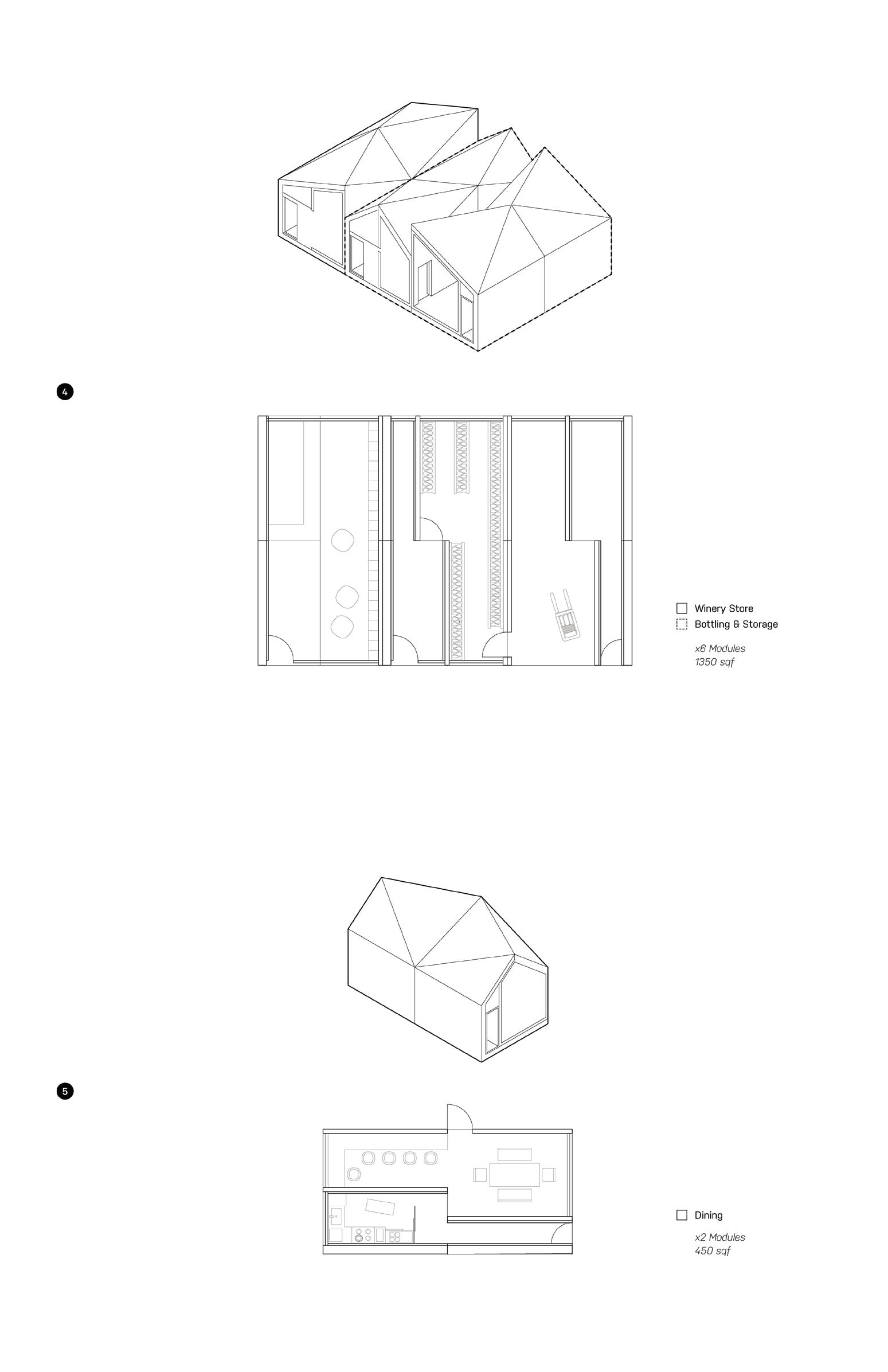

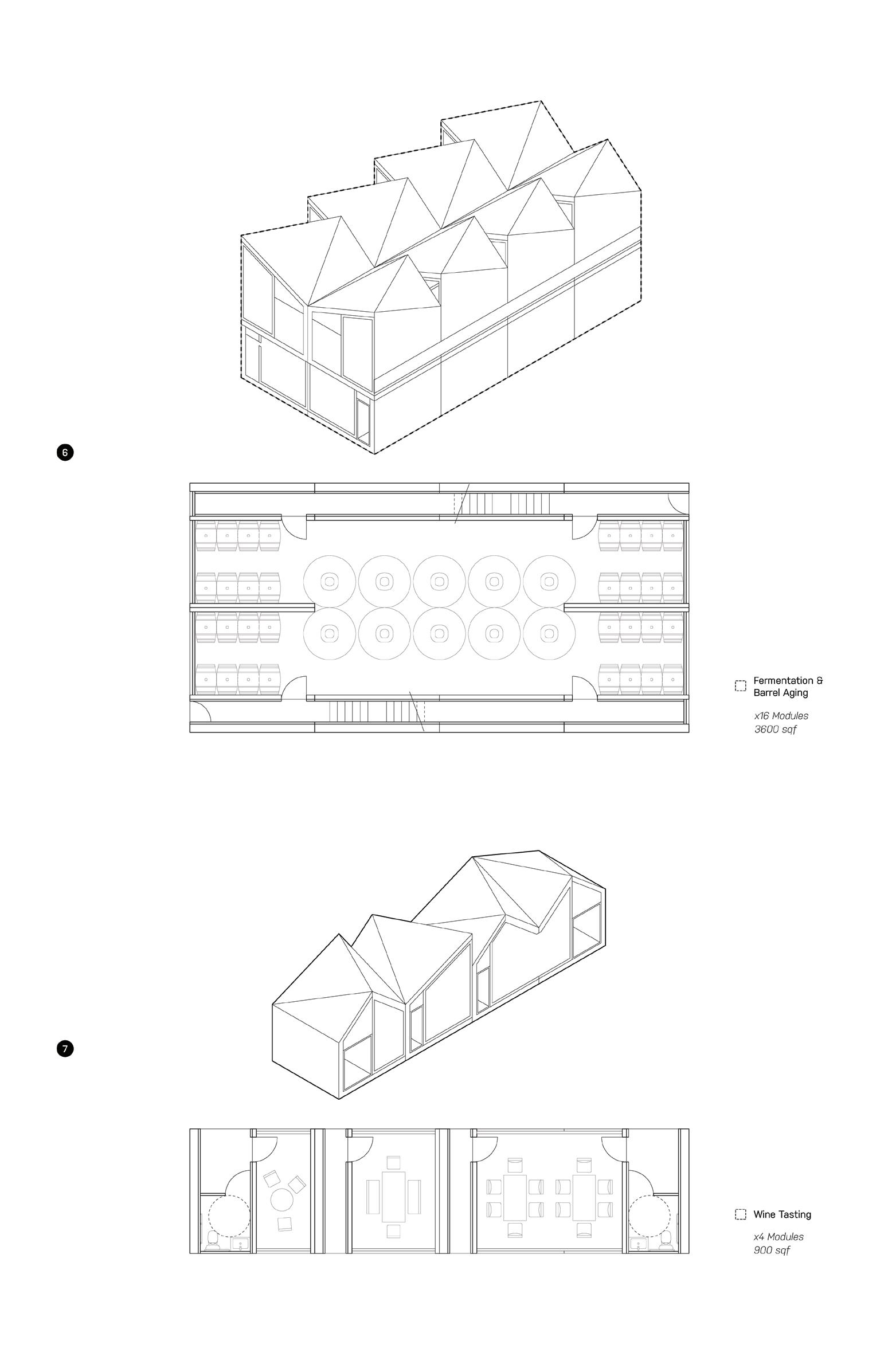

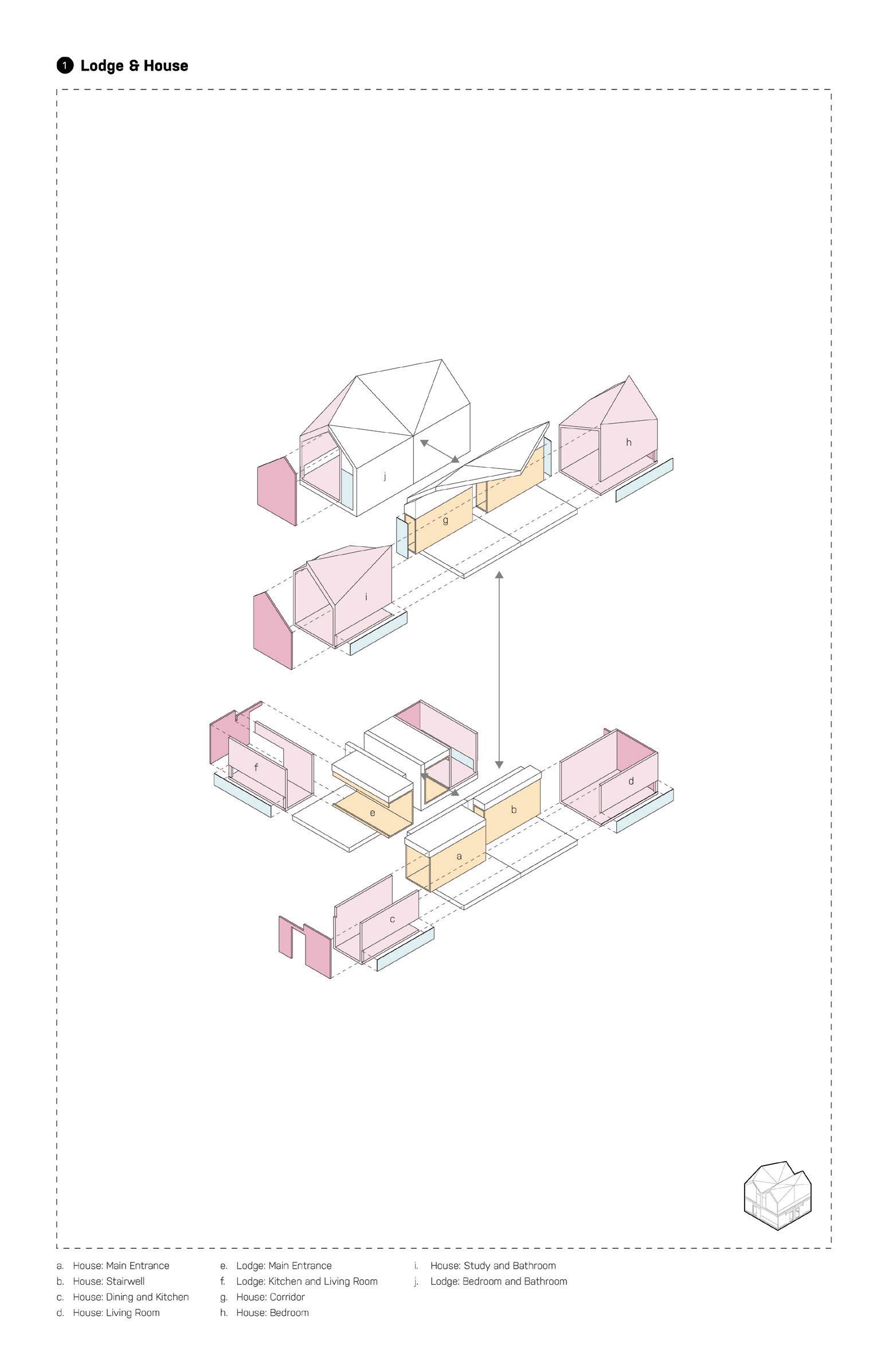

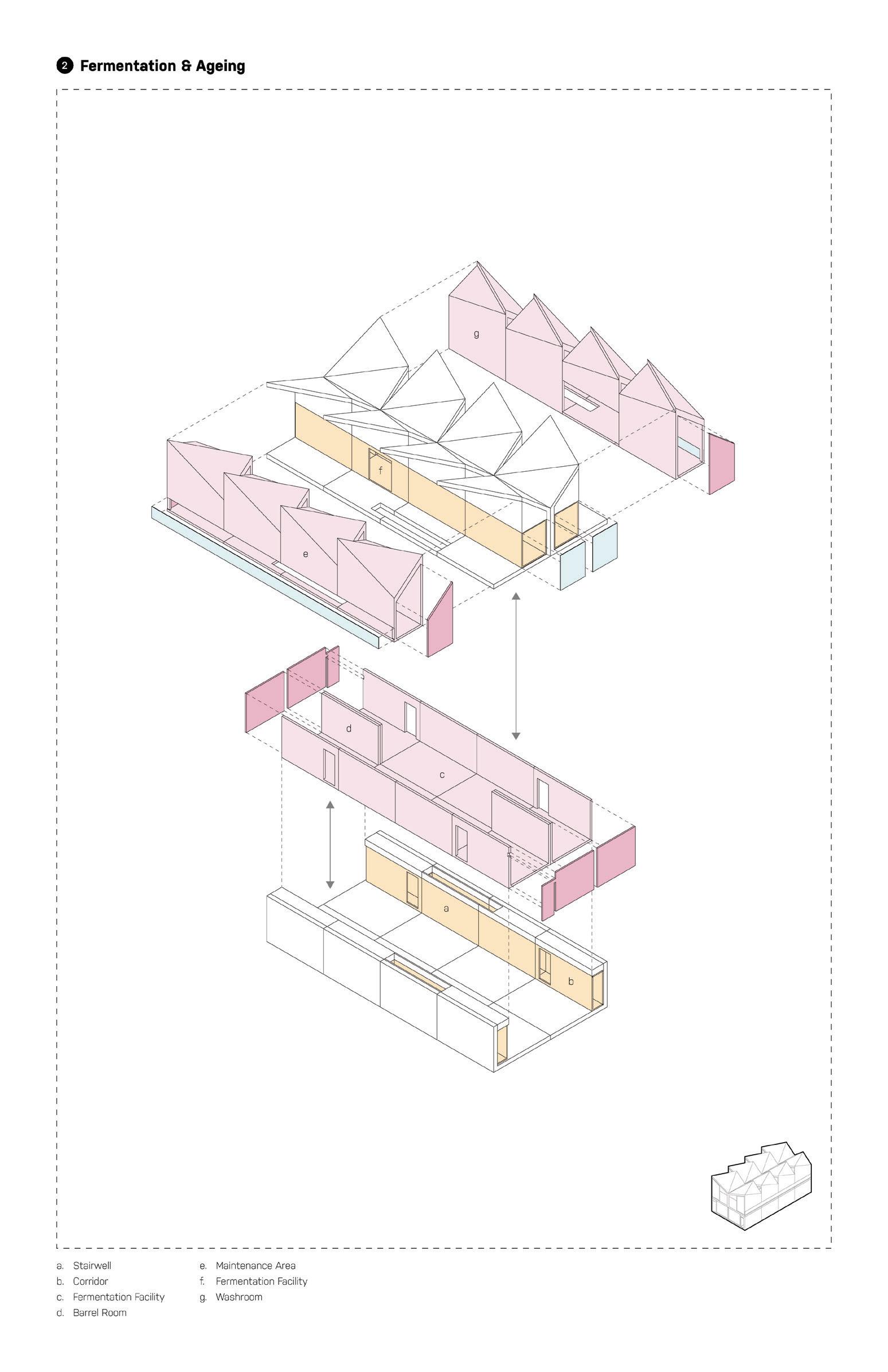

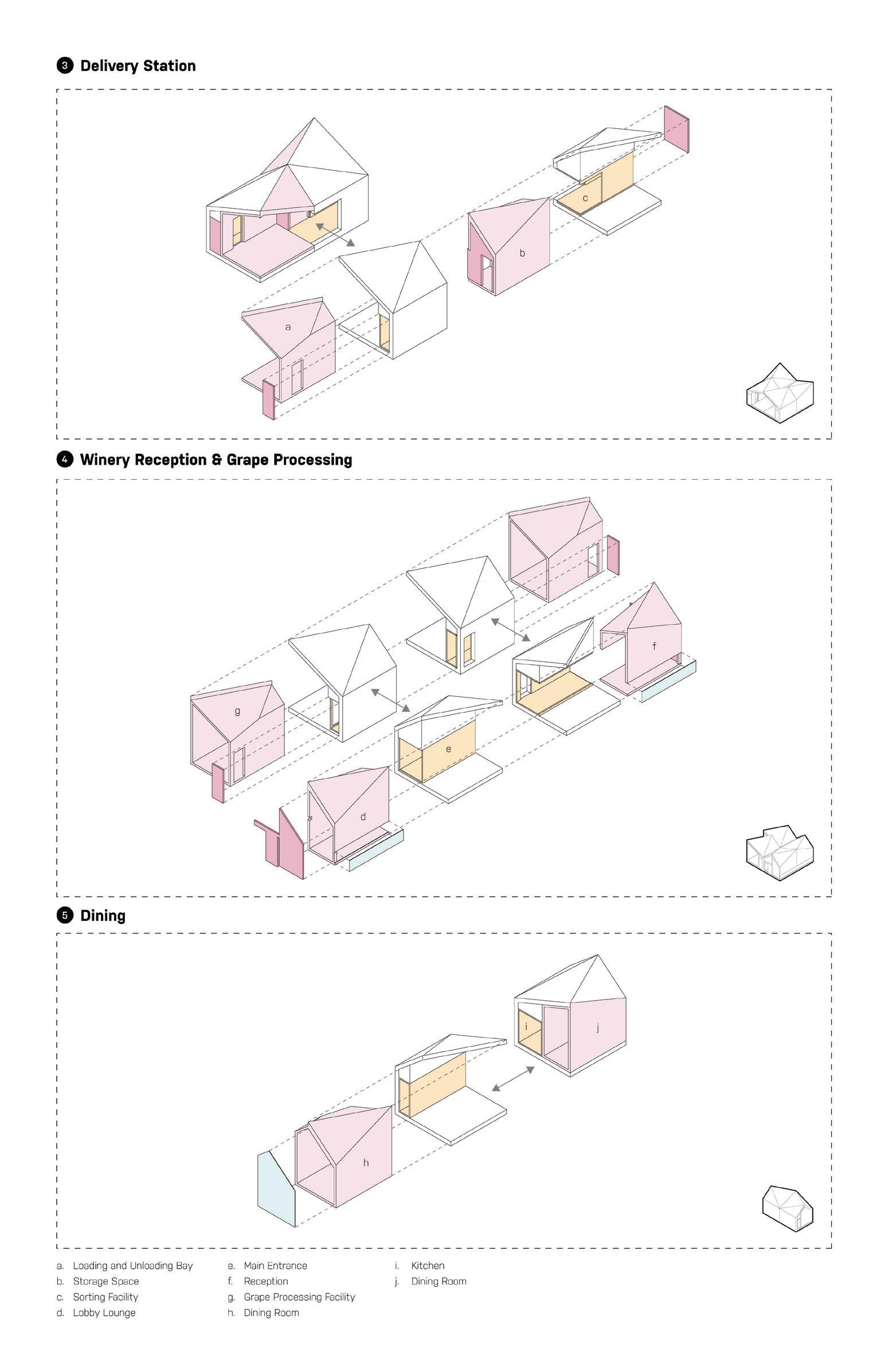

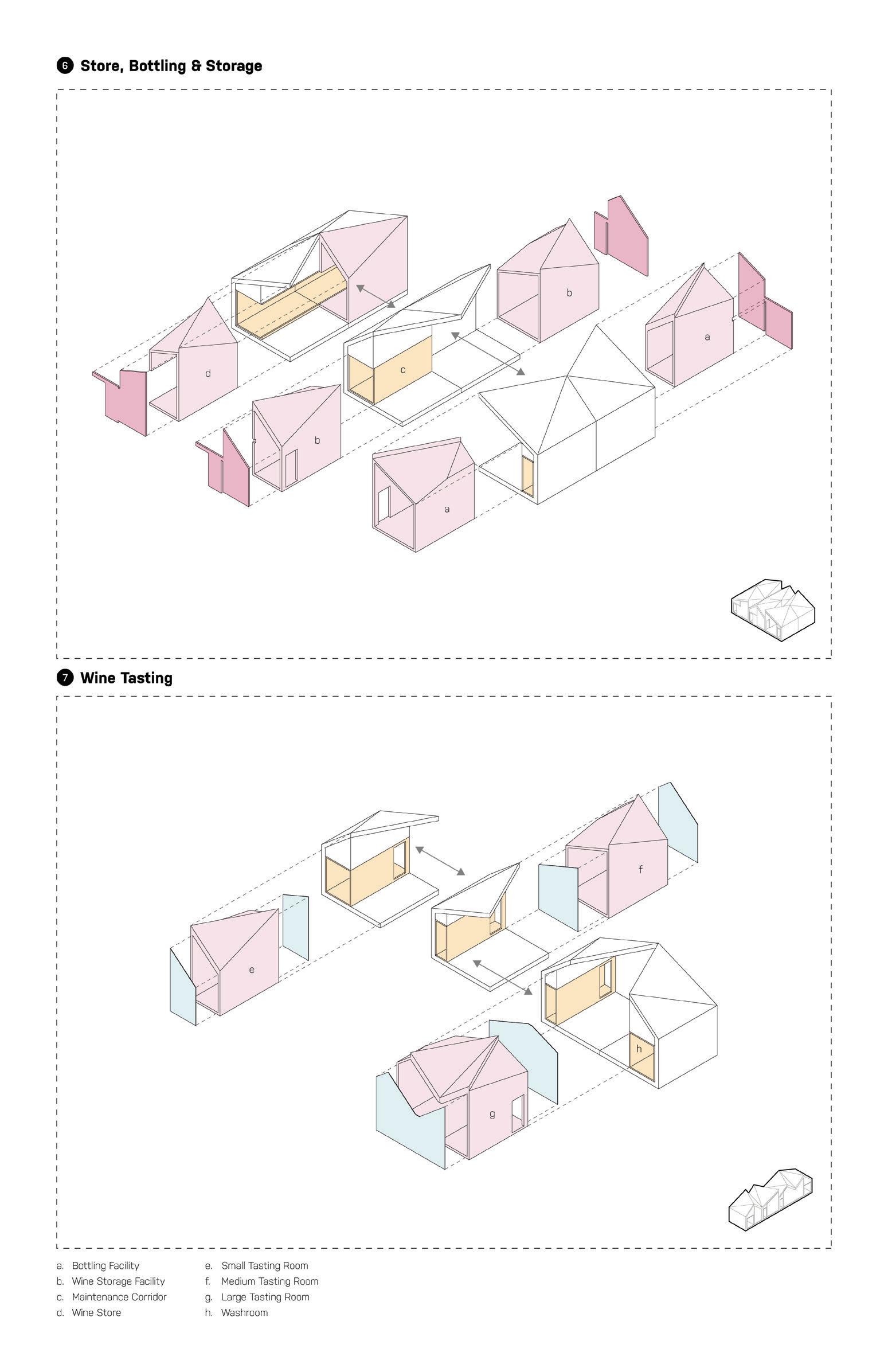

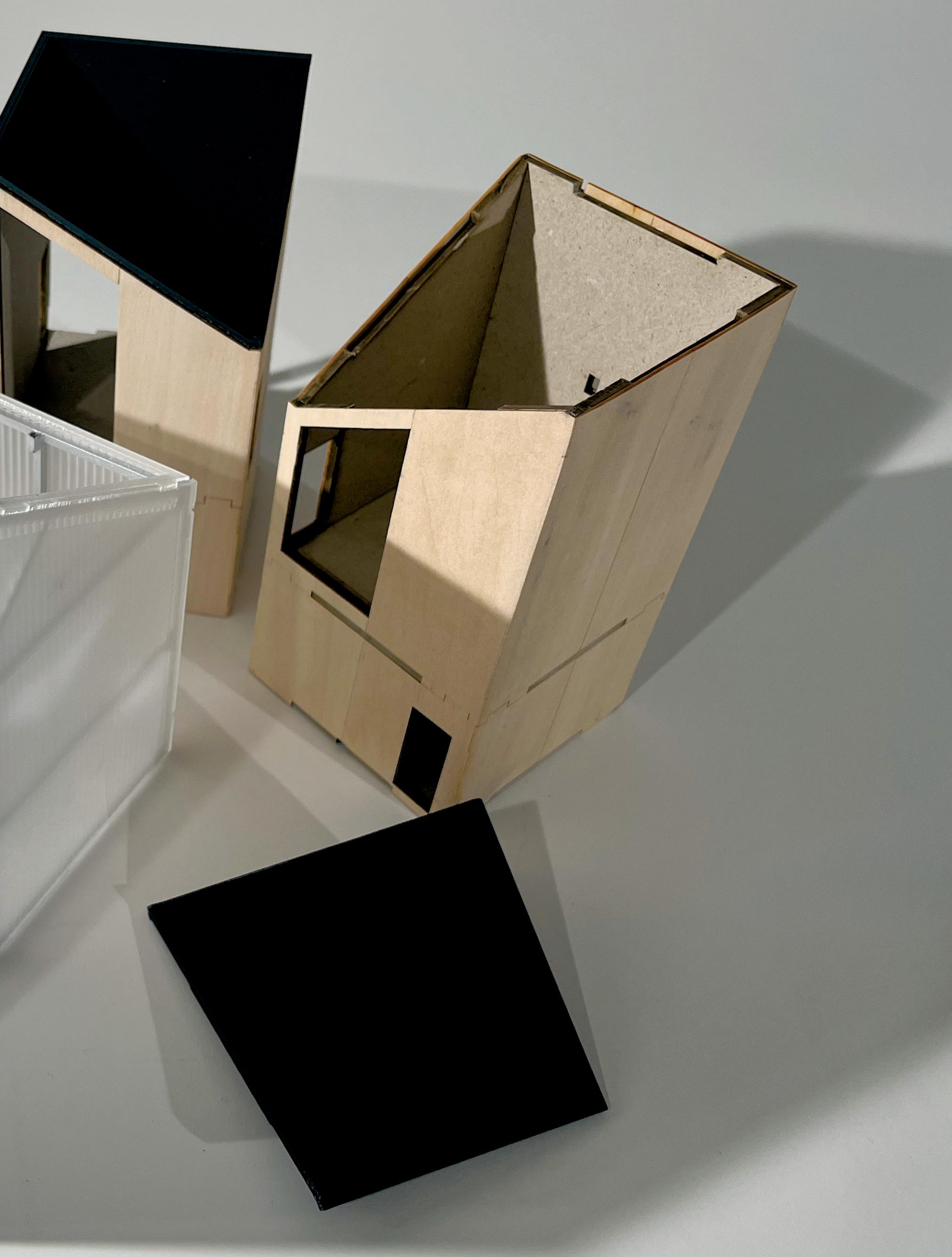

Ceremony explores the dual nature of its Japanese etymology, encompassing both celebratory bliss and ritualistic discipline. This conceptual framework establishes the foundation for reimagining the relationship between pleasure and work in architecture. As the future of work increasingly demands integration between the mundane and the joyful, this project proposes that the boundaries between living, working, and playing must dissolve into productive adjacencies.

The architectural scheme centres on a winery that shares programmatic adjacencies with worker housing and shortstay accommodations for remote workers. These functions are organised along intersecting axes of work and living that run diagonally across the landscape. The winery’s linear arrangement follows the ceremonial sequence of wine production, running parallel to visitor circulation and tasting spaces. This processional logic transforms functional necessity into spatial ritual, where production becomes performance and work becomes celebration. The adjacency between production and consumption spaces reinforces the idea that work and pleasure can coexist harmoniously.

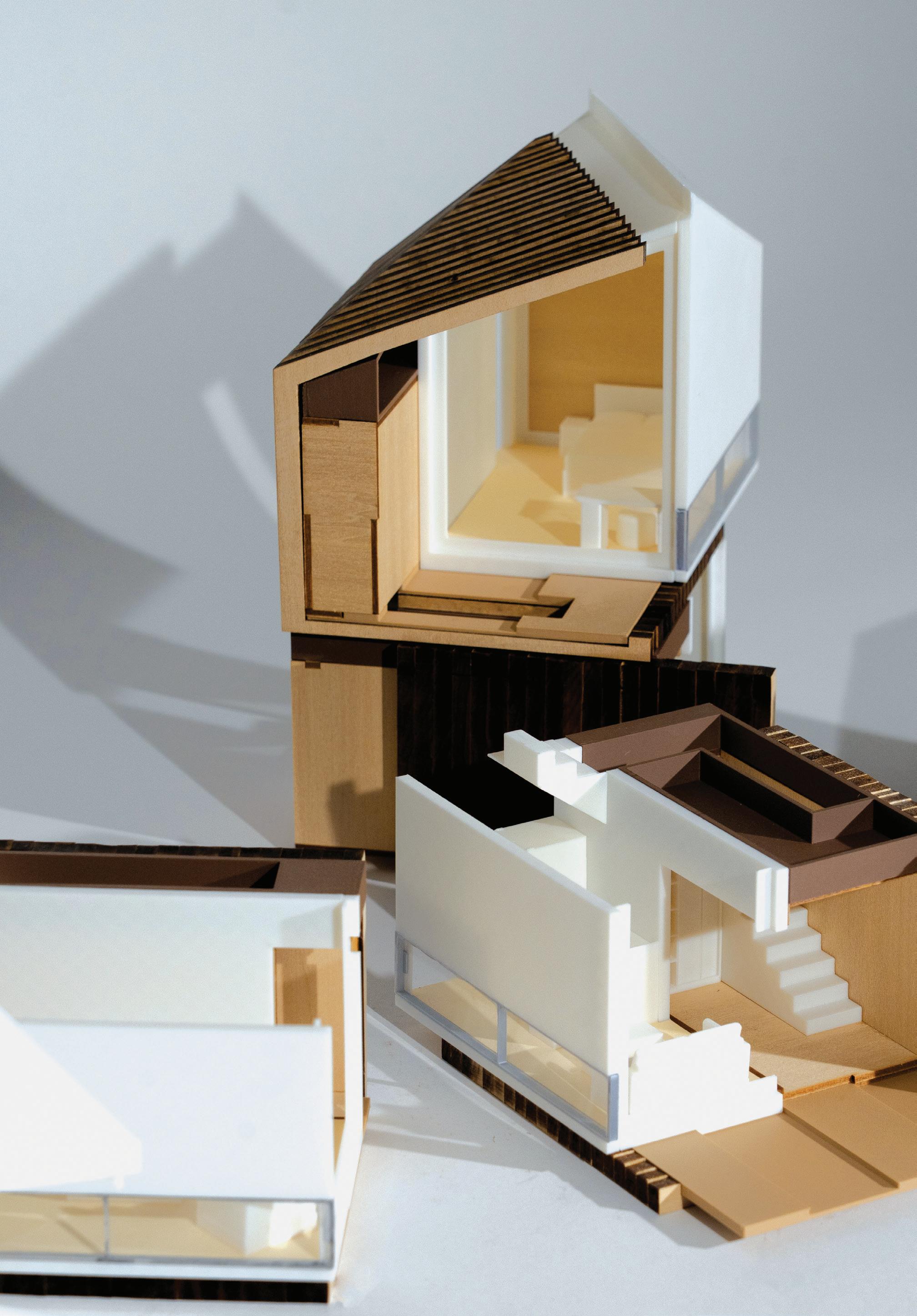

Constructed using the OSM method of construction, the form of the single module emerges from the lofting of gable and shed profiles — typological forms that represent house and work, rest and production, respectively. These modules repeat and combine in various permutations, embodying ceremony through ritualisation and repetition while maintaining operational flexibility. The exterior surfaces achieve material differentiation through reflection rather than projection, creating a flush facade where matte timber, transparent glass, and reflective steel borders distinguish program through subtle material dialogue that undercuts formal hierarchy.

Previous page: View of system aggregation to create a campus of spatial variety

Top and bottom: Model exploration through massing combinations

Following page: View of the final model showing the different layers incorporated to create this module

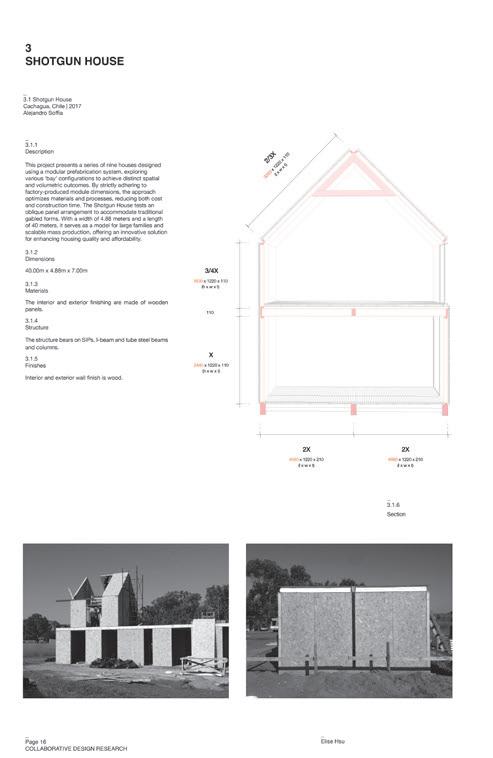

Elise Hsu

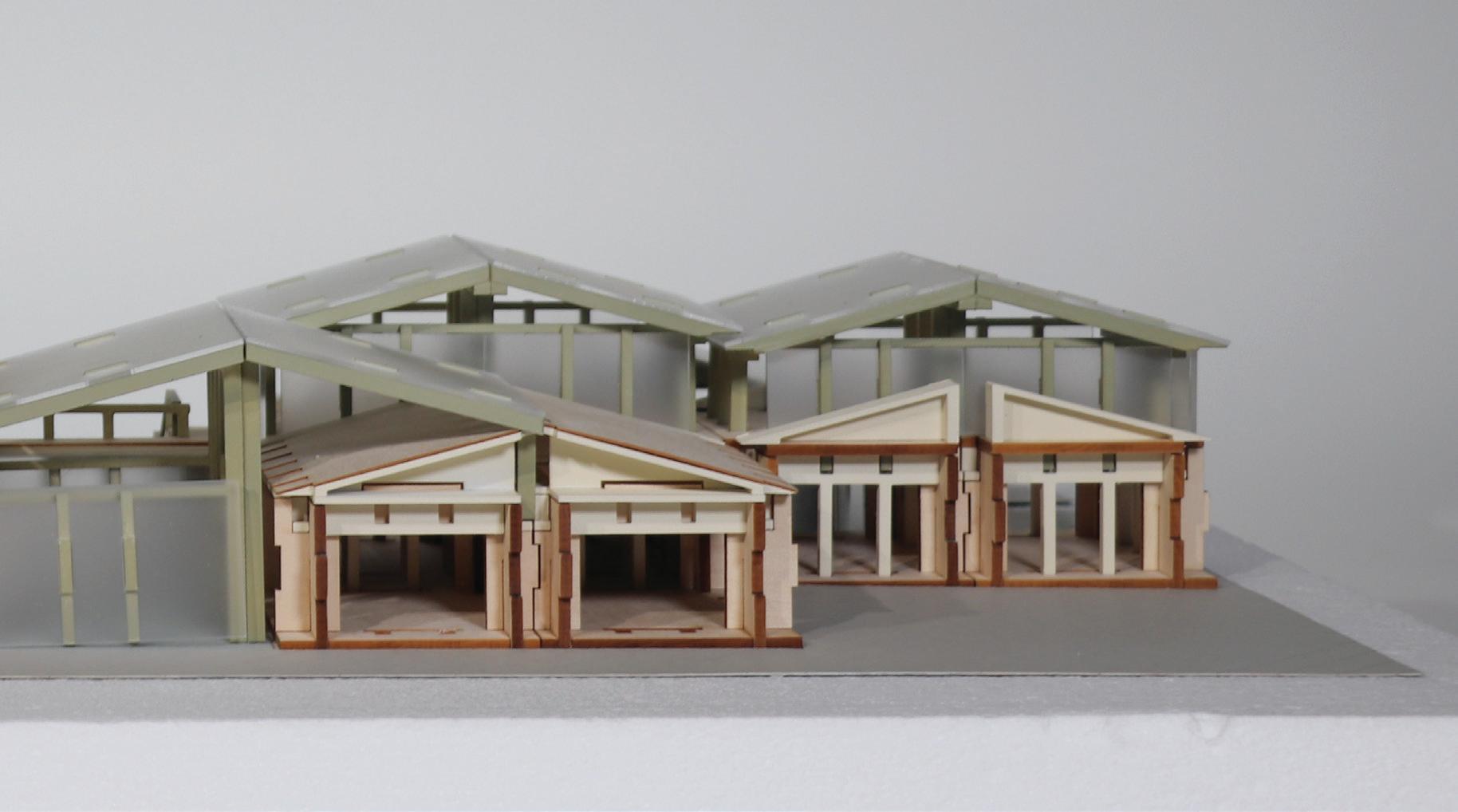

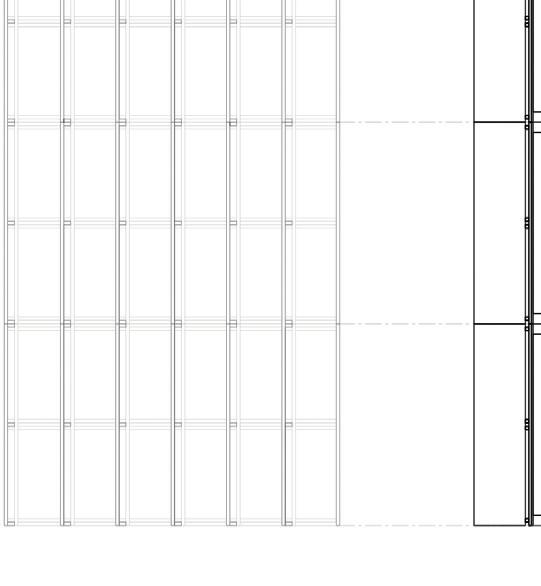

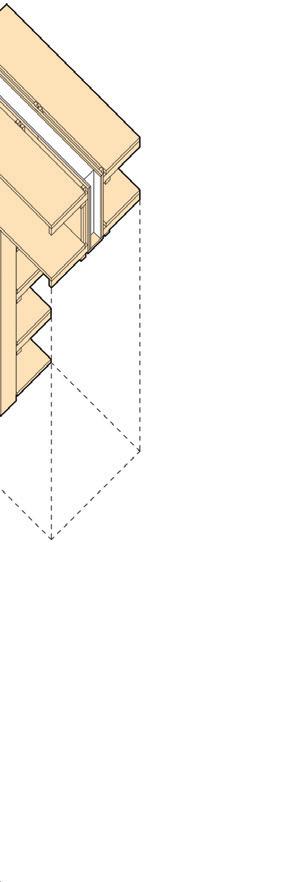

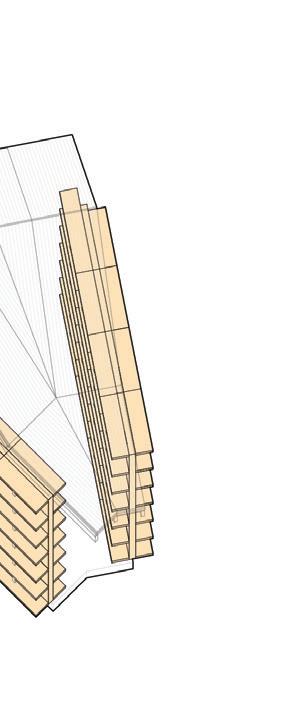

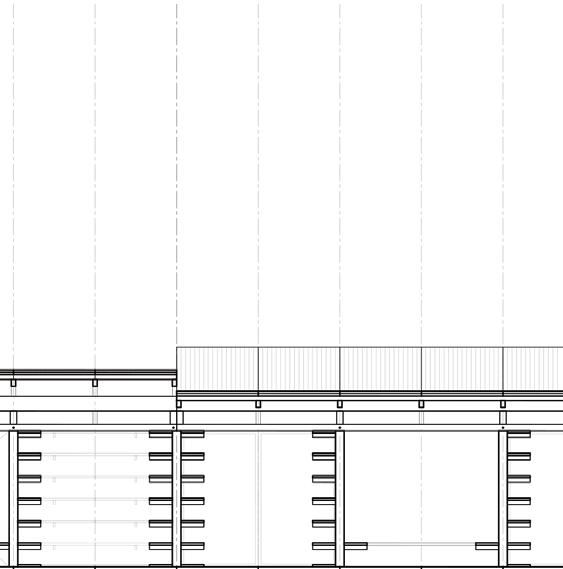

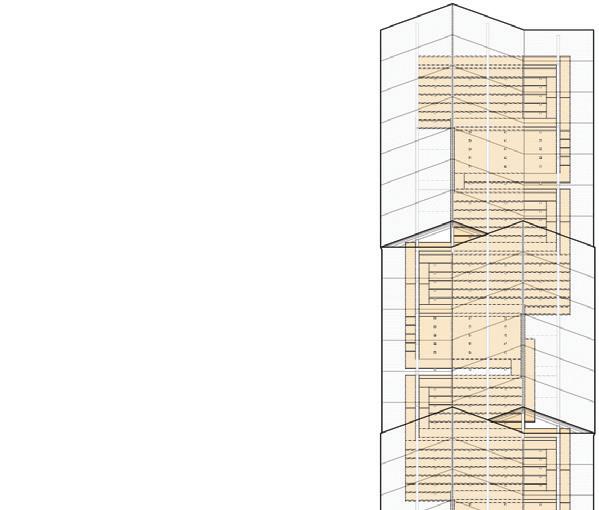

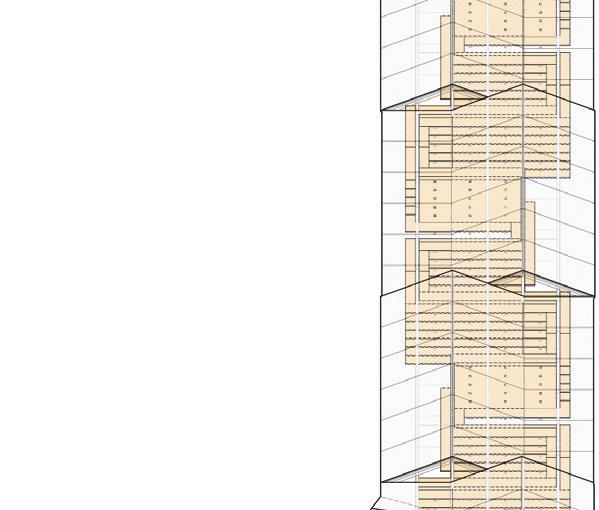

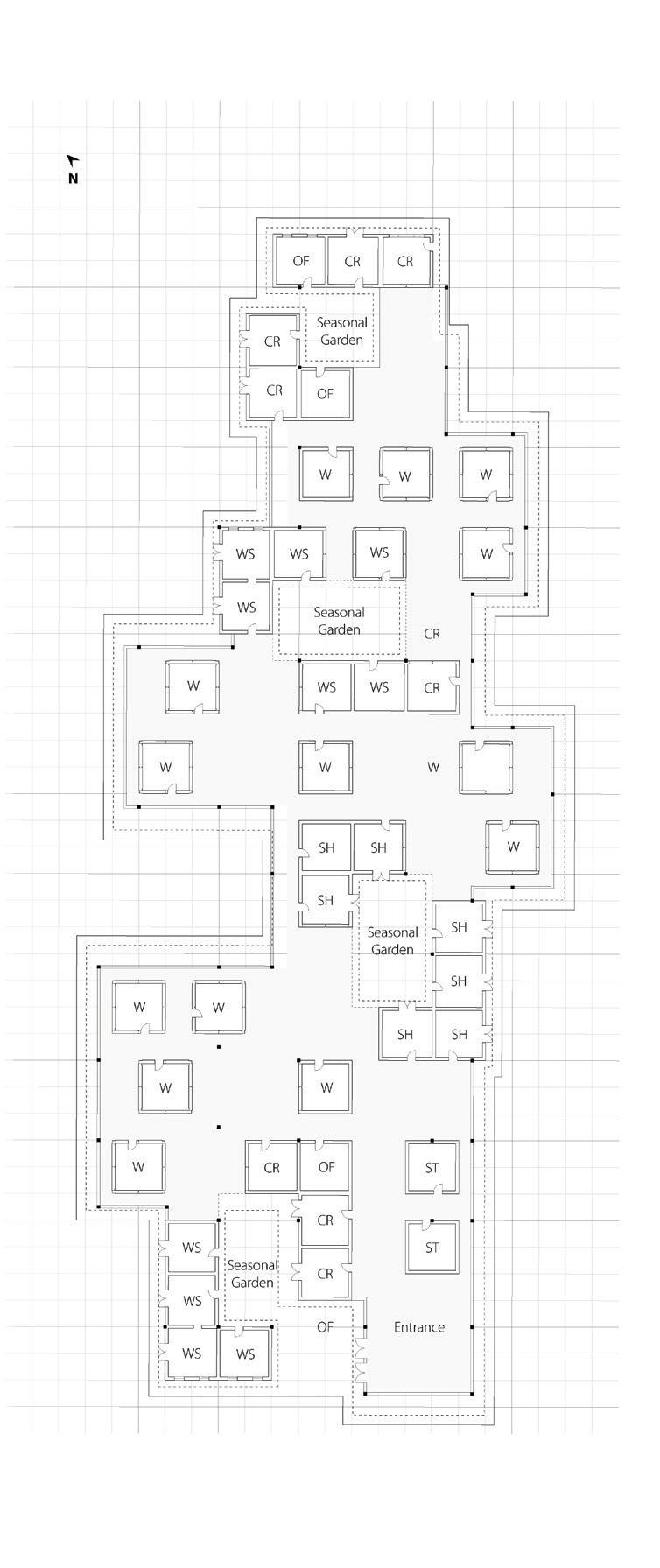

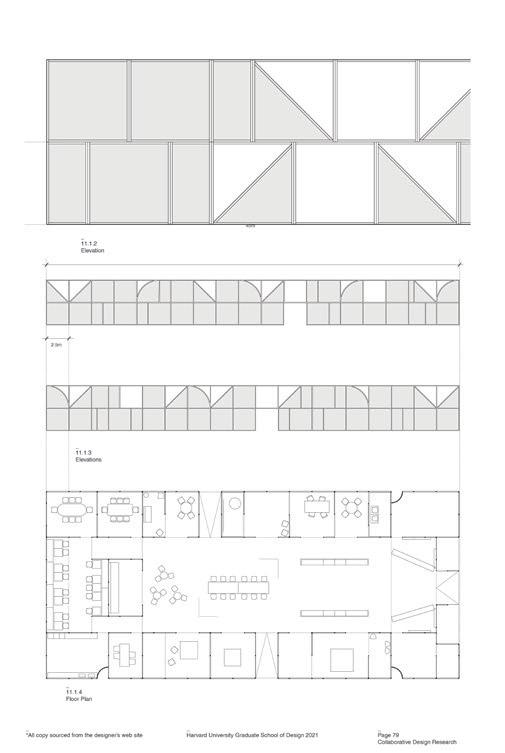

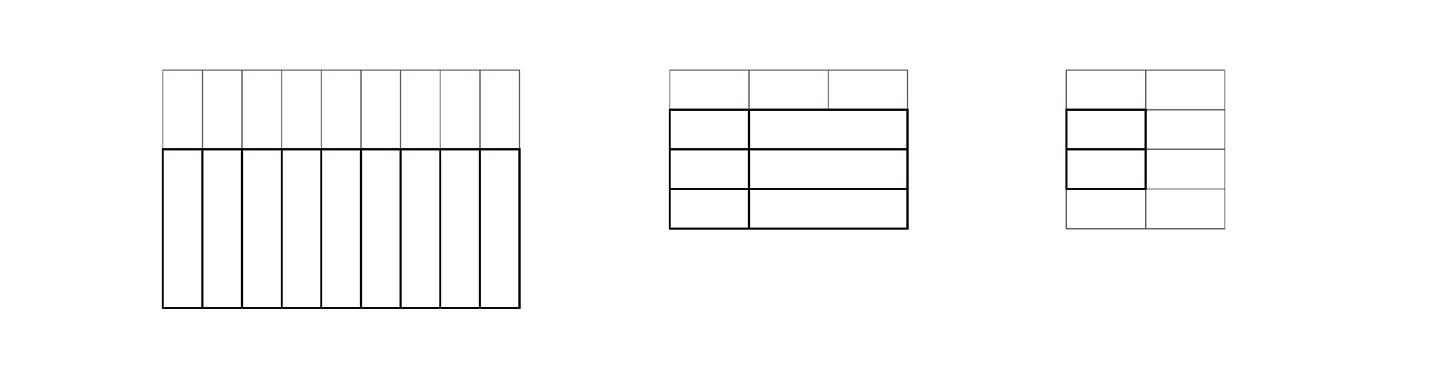

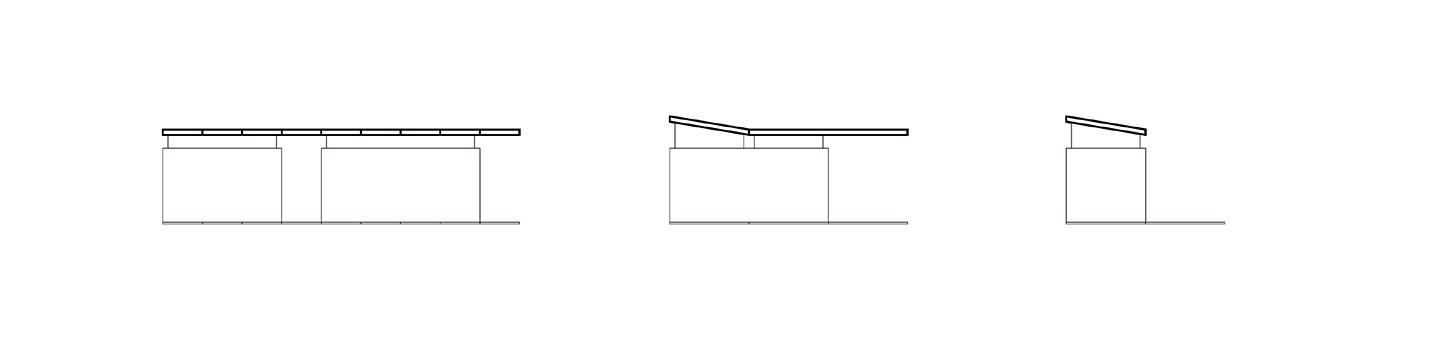

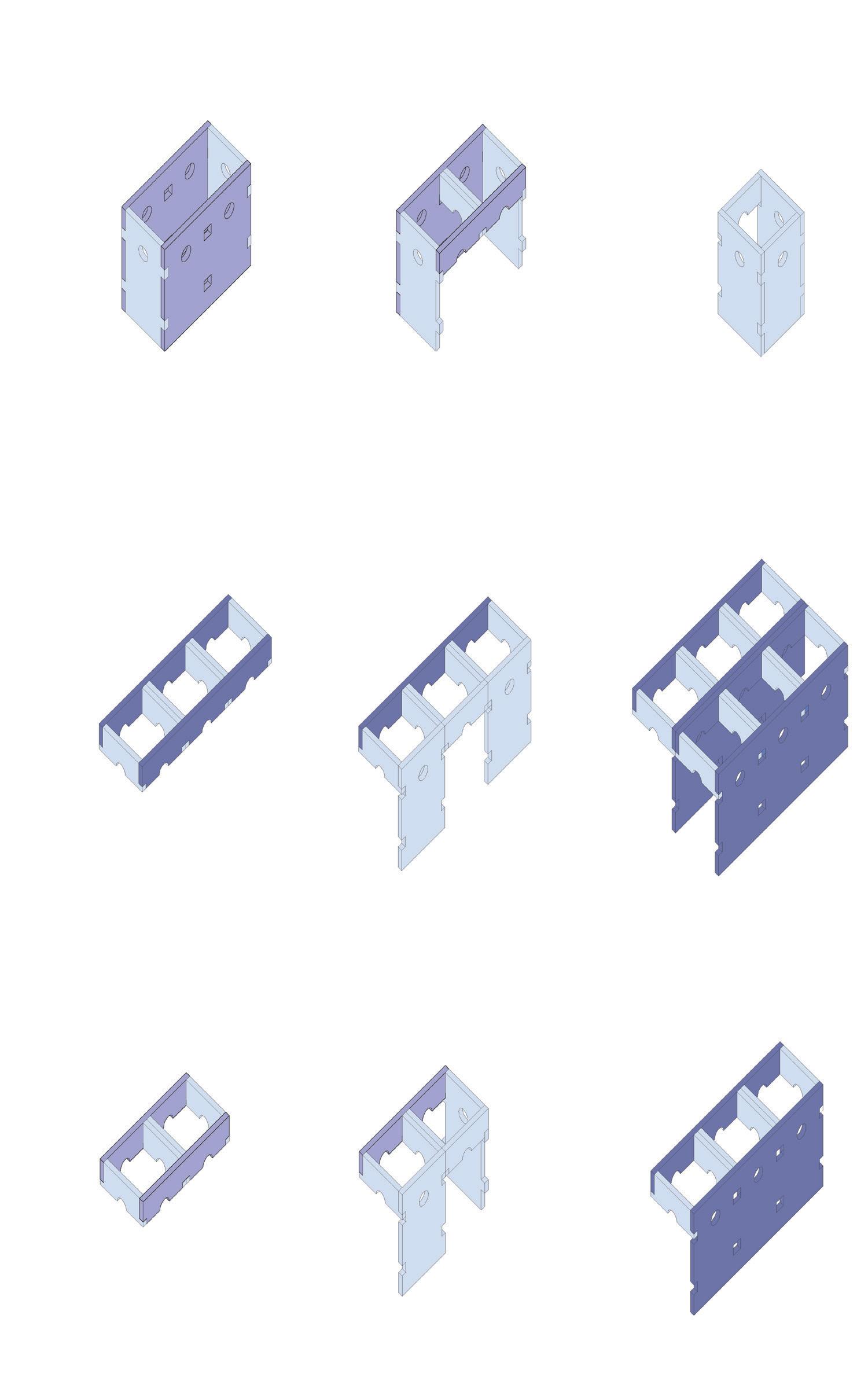

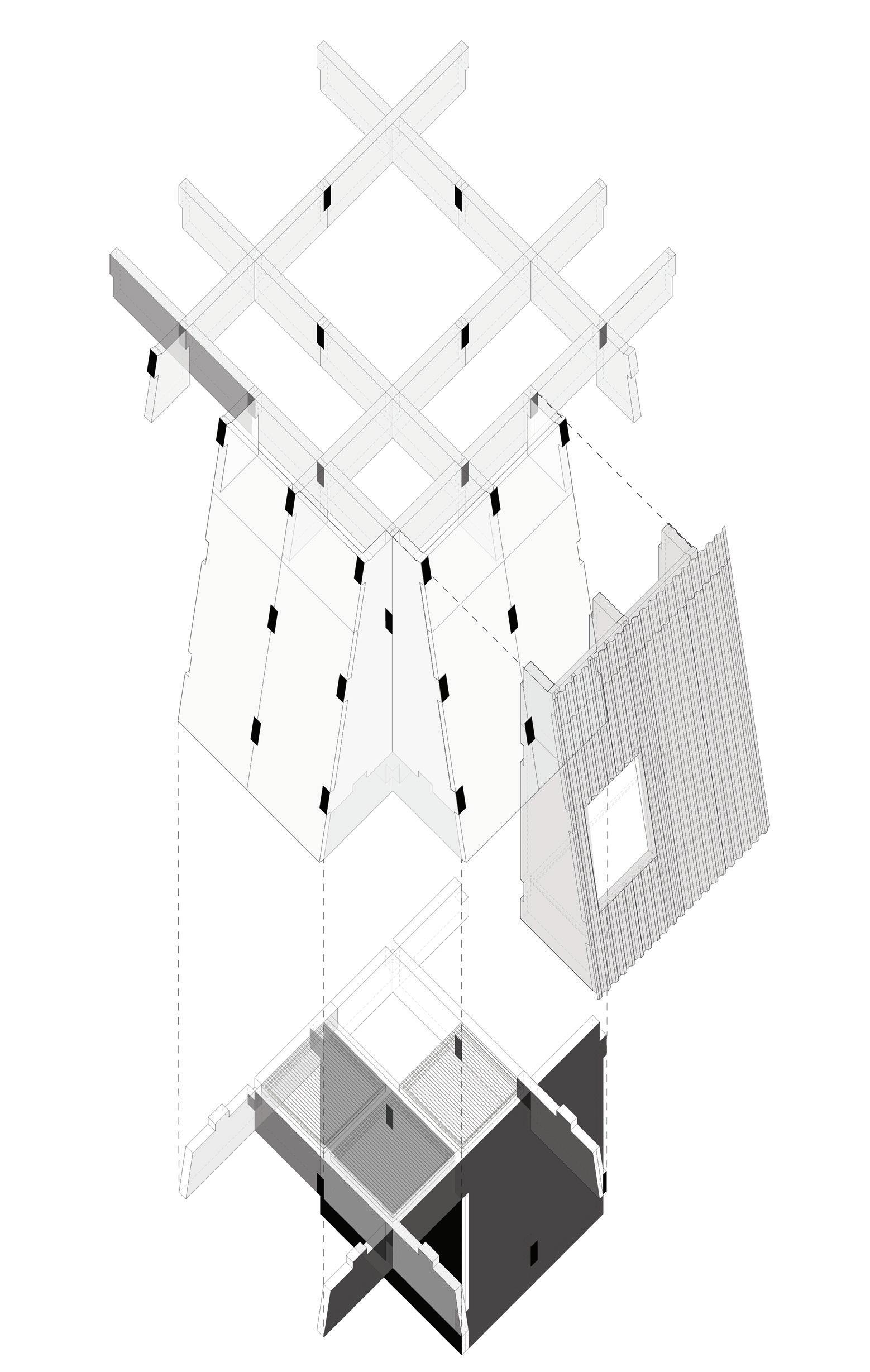

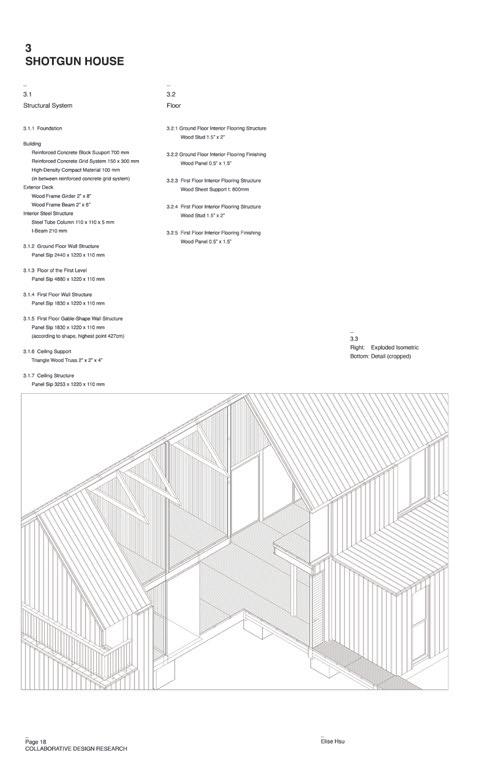

The design concept draws inspiration from architectural typologies commonly found in Japan’s agricultural production system, such as the main house, auxiliary buildings, and small sheds. These structures are typically organized according to functional hierarchies, forming a layered spatial logic of primary, secondary, and extended spaces.

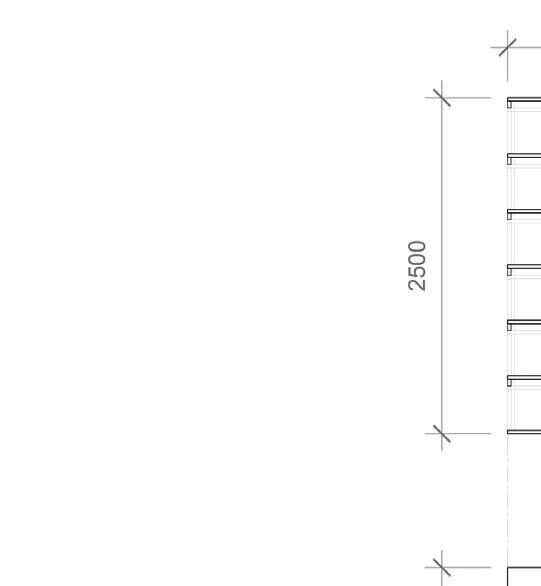

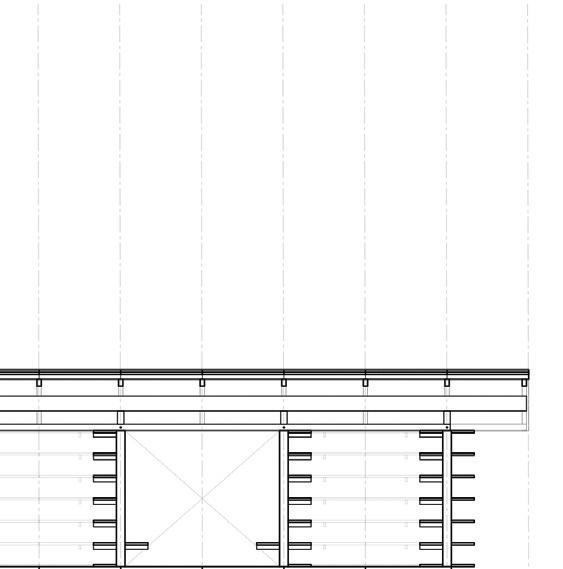

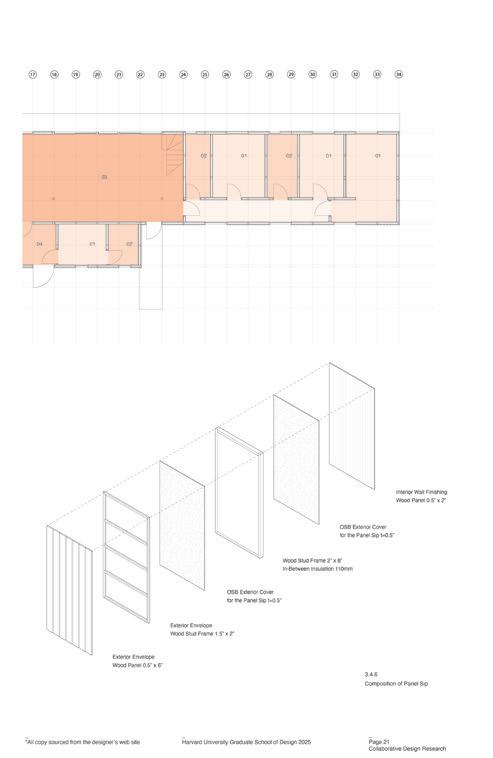

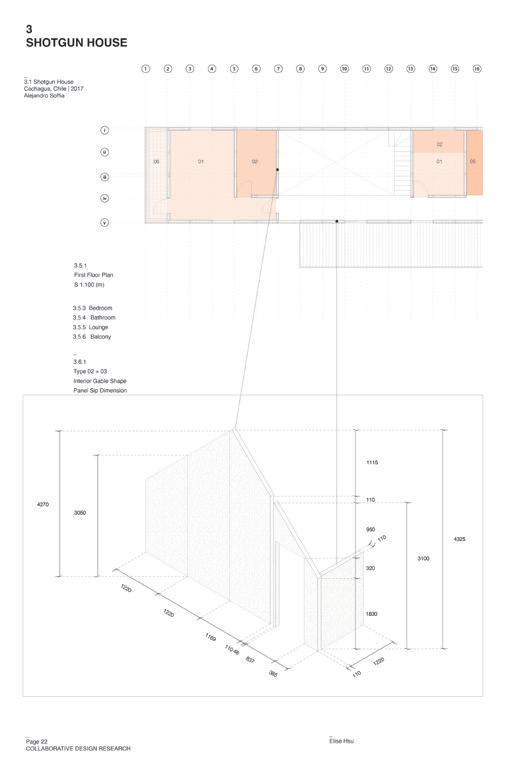

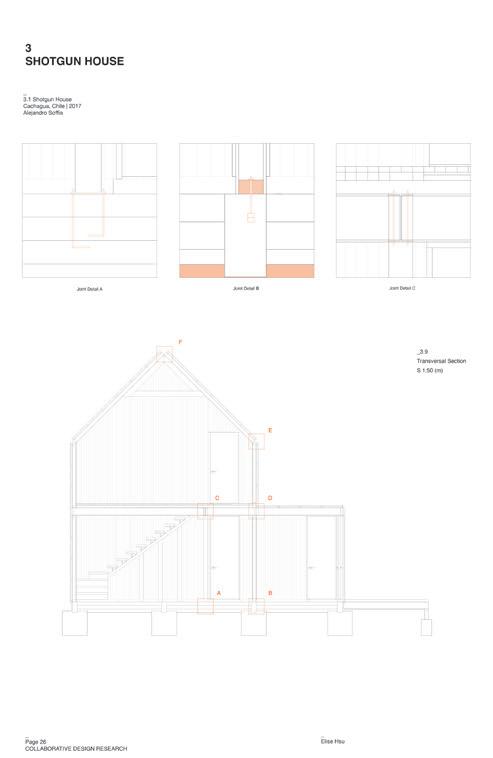

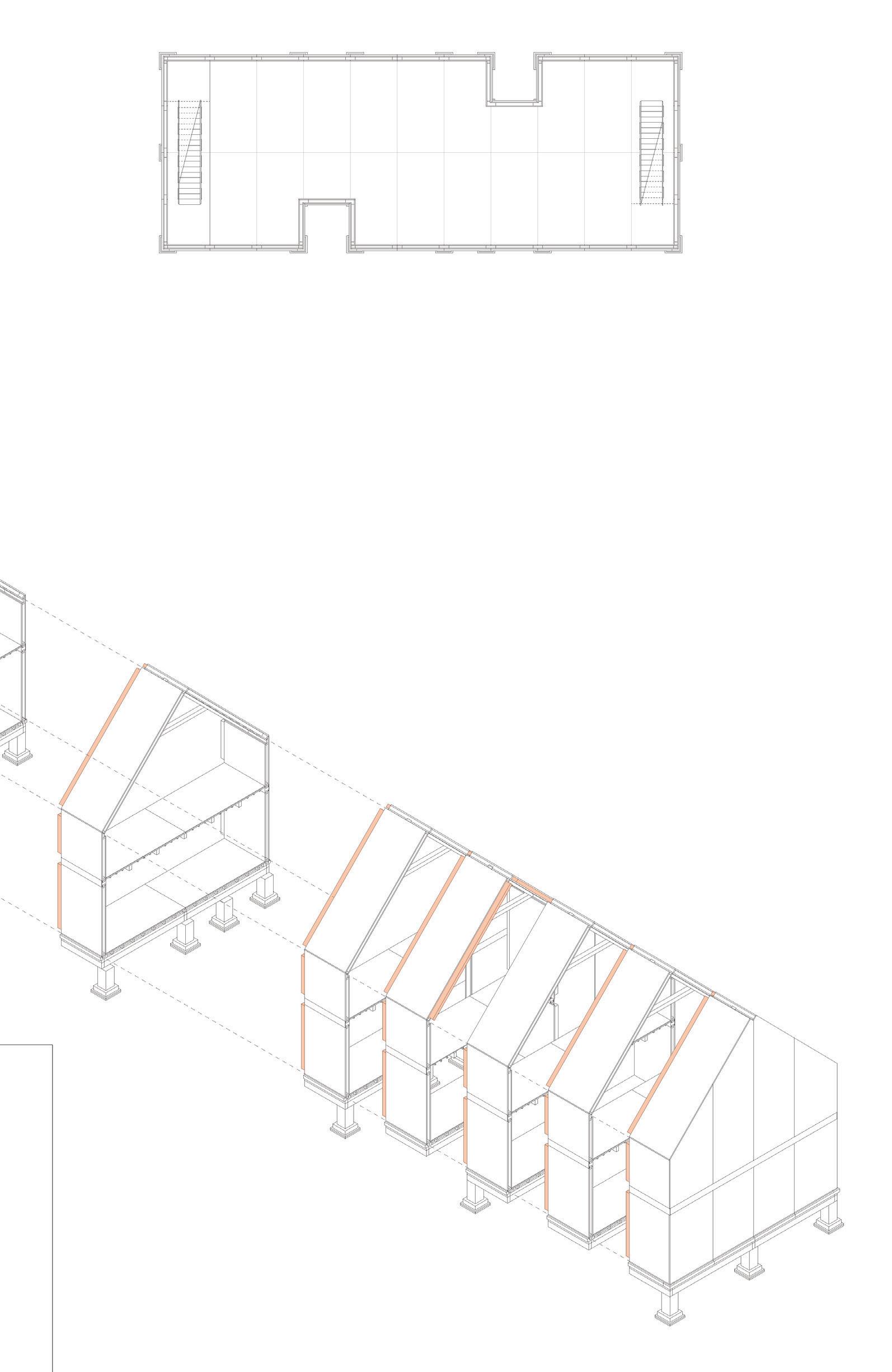

The spatial system is broadly divided into two categories: the main structure and extendable modules. Both are based on a standardized unit width of 2.44 meters, derived from the dimension of SIP panels. The main structure comprises 11 panel units, totaling 26.84 meters in length, with recessed joints at the 4th and 8th panels to accommodate plug-in modules.

The extension system consists of three types: (1) a vertical connector module with the same width and height as the main structure (2.44 meters); (2) plug-in type 1, featuring an eaved roof and composed of seven panels (17.08 meters); and (3) plug-in type 2, with a gable roof and made of six panels (14.64 meters). Plug-in types 1 and 2 may serve as corridors, storage rooms, or semi-outdoor workspaces. These are not limited to fixed lengths and may be scaled or used independently depending on programmatic needs.

This flexible spatial logic supports a range of programs, including studios, hostels, shops, and community centers. Depending on frequency, scale, and privacy requirements, modules can function independently or be integrated into a larger composite structure. Adaptive connection mechanisms allow for configurations that support work, dwelling, and public interaction, while accommodating varied user groups and site conditions.

03

05

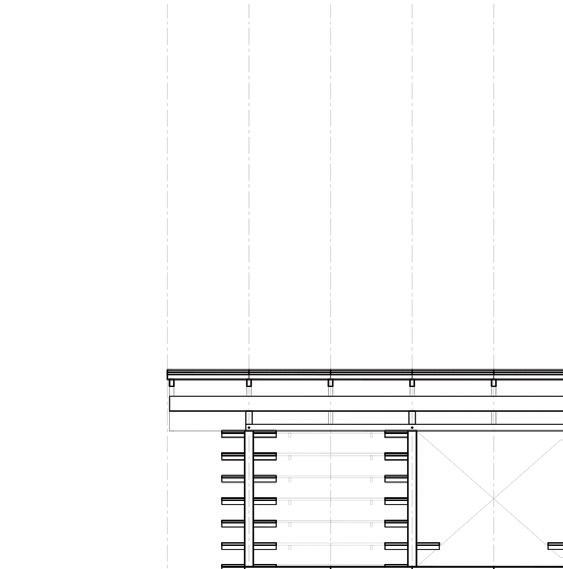

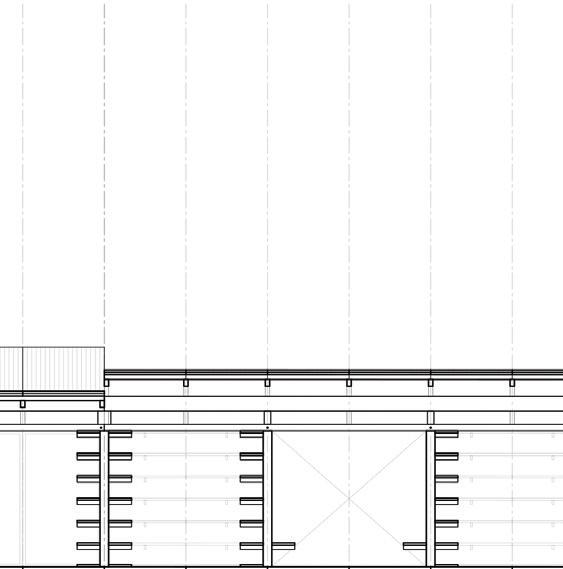

Above: Plans and elevations of

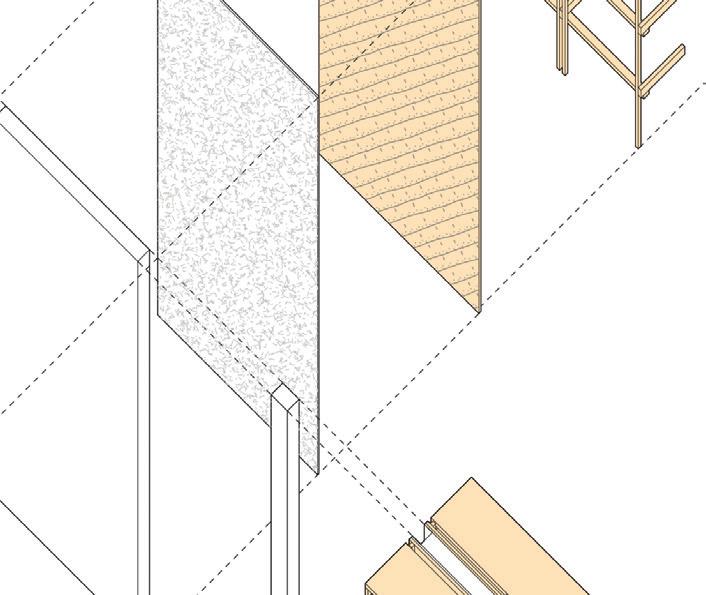

Above: Assembly of SIP panels

Step 01

Use the EPS insulation foam (1584 x 2816 x 150mm).

Step 02

Apply a thin layer of glue on both side of the EPS insulation foam, and paste the OSB wood sheathing pieces together.

Step 03

Joint with the block-spline joint (500 x 3350 x 150mm).

Step 04

Add two wood studs on the bottom and the top of the SIP Panel.

Completion of a typical SIP Panel on the Ground Floor. (2440 x 3600 x 150mm)

Step 05

Connect with the other SIP Panel with the block-spline joint. (interior side)

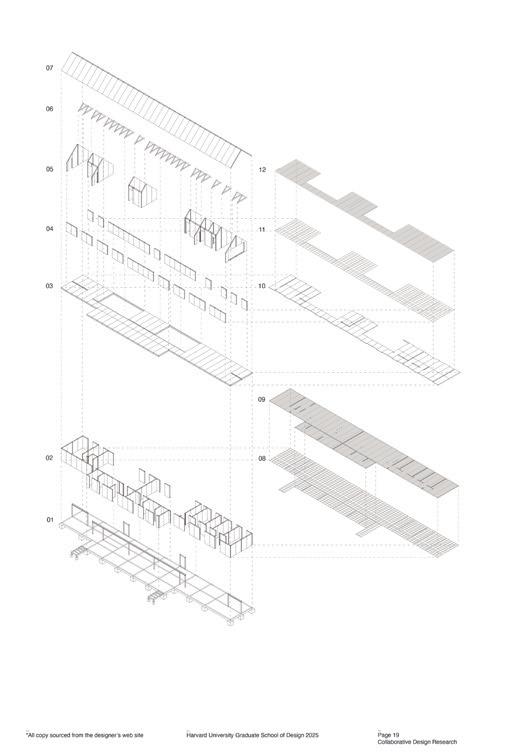

Across: Exploded isometric of different types of Module A; ground floor plan to the main building; isometric of the main building

Module 06

Addition with Plug-In

Paired with Module 05

Module 01

Main Building with Two Slots

Module 05

Addition with Plug-In

with Hatlf Eaves

02

Module 03

Addition with Plug-In

Gable with Eaves

Module 04

Addition with Plug-In

Paired with Module 03

Ehsani-Yeganeh

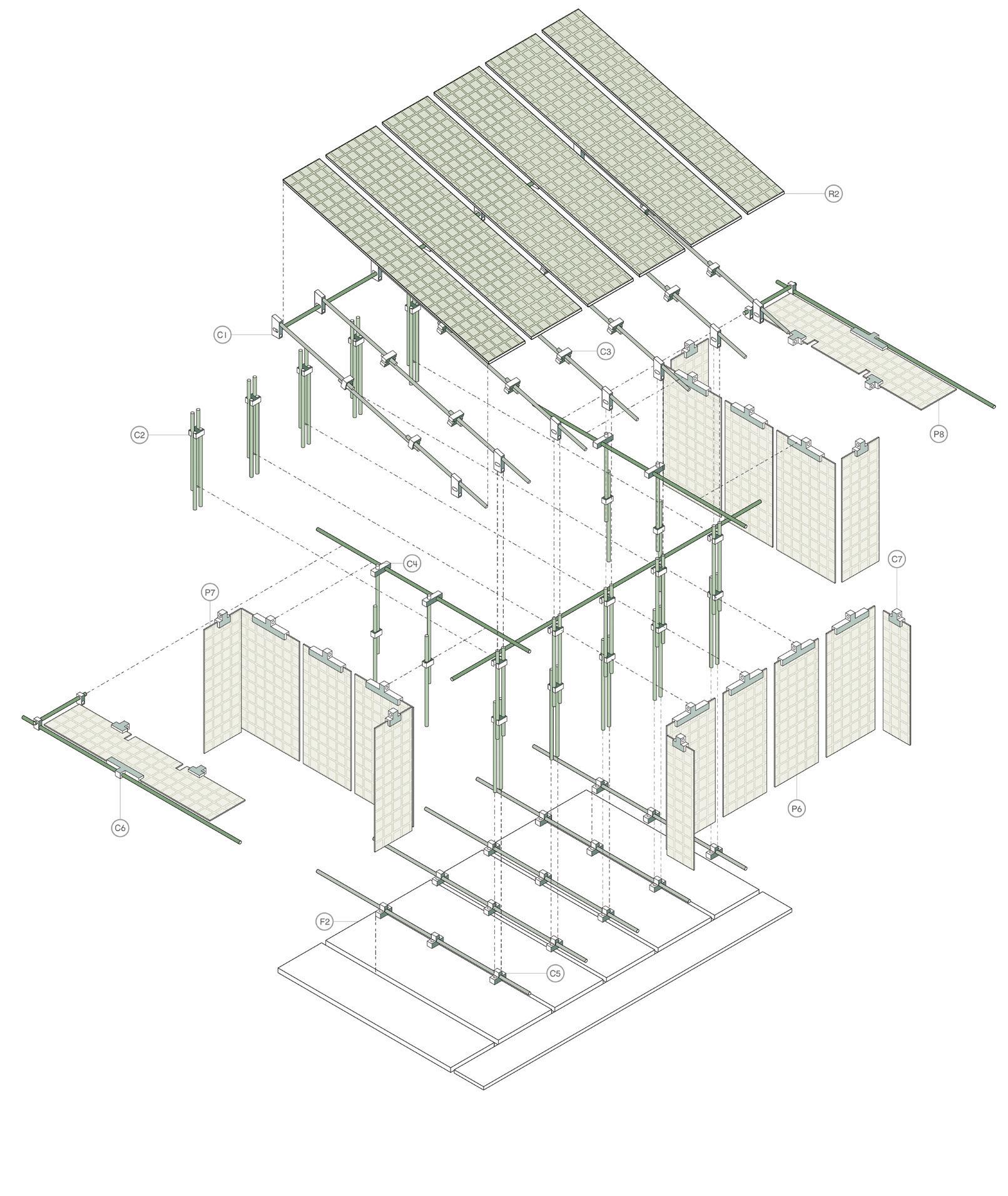

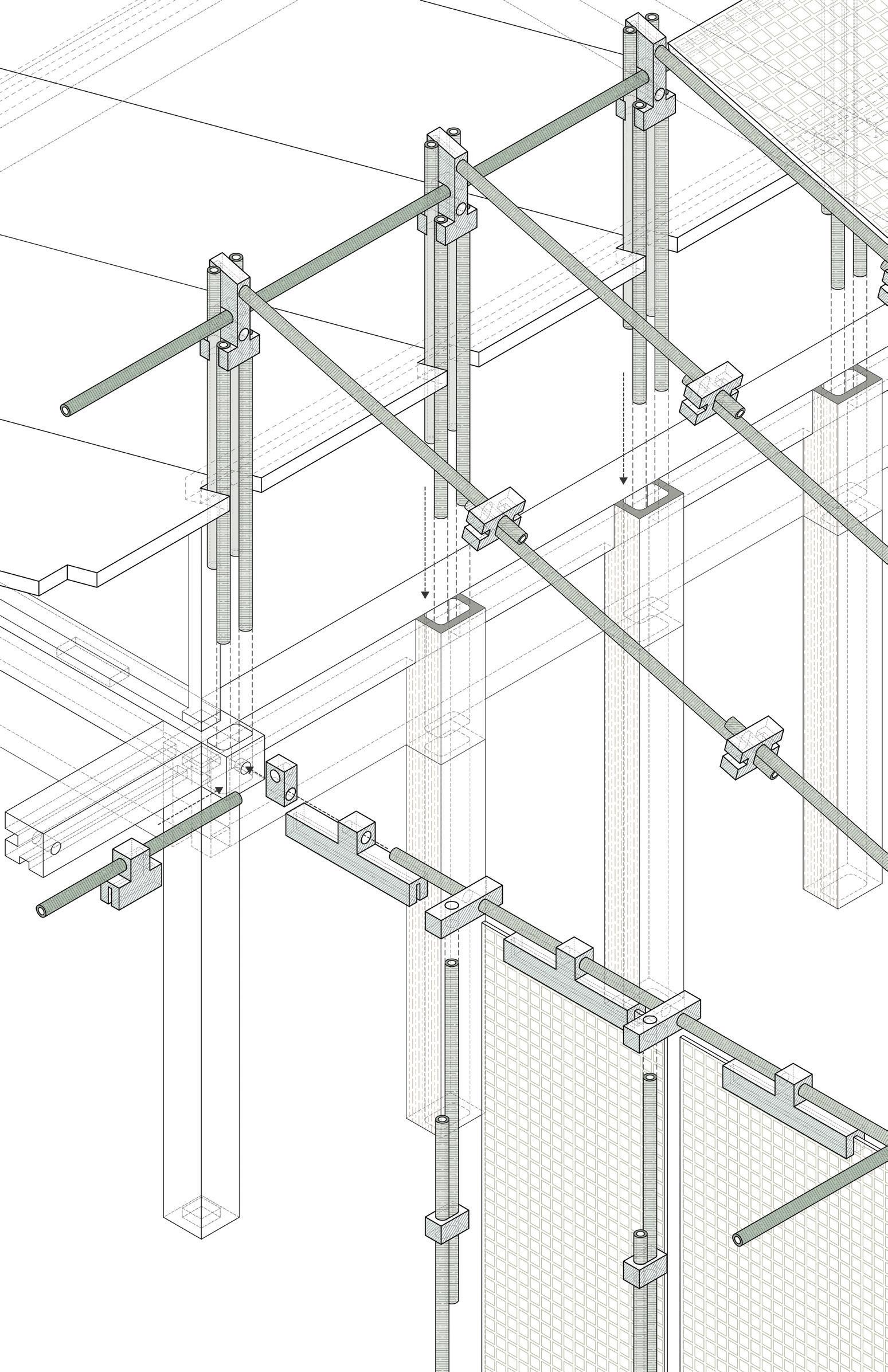

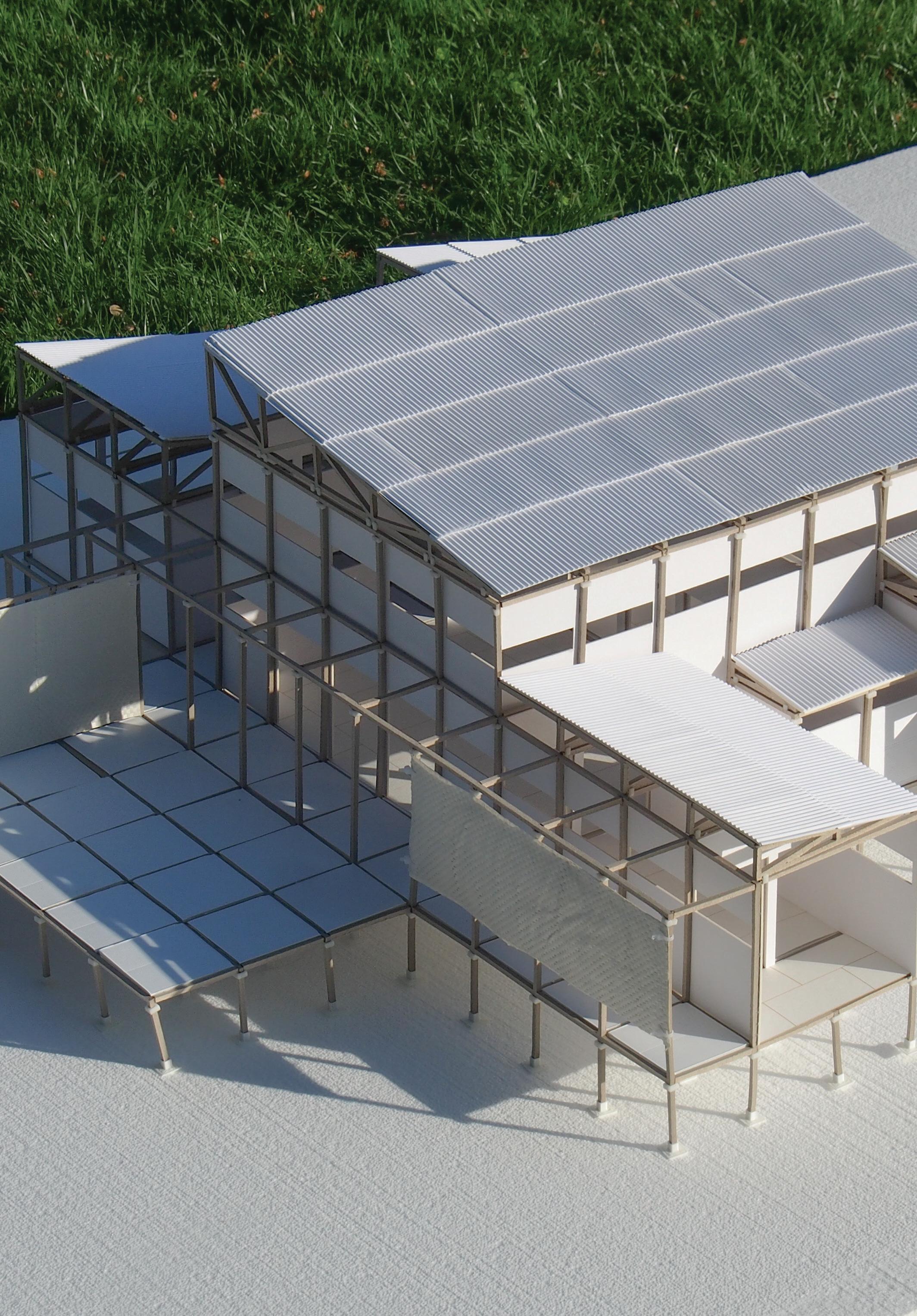

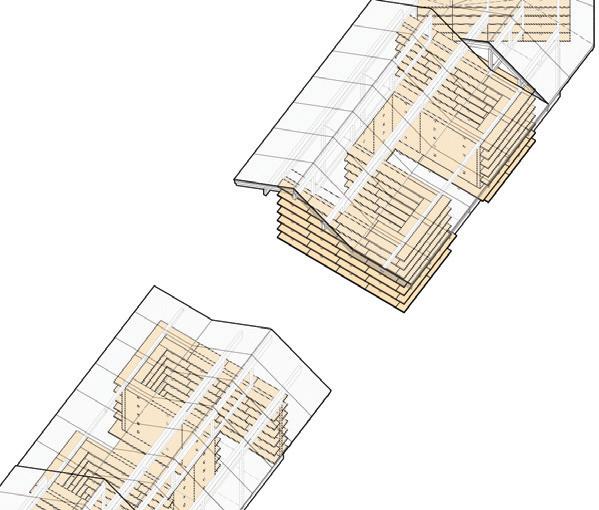

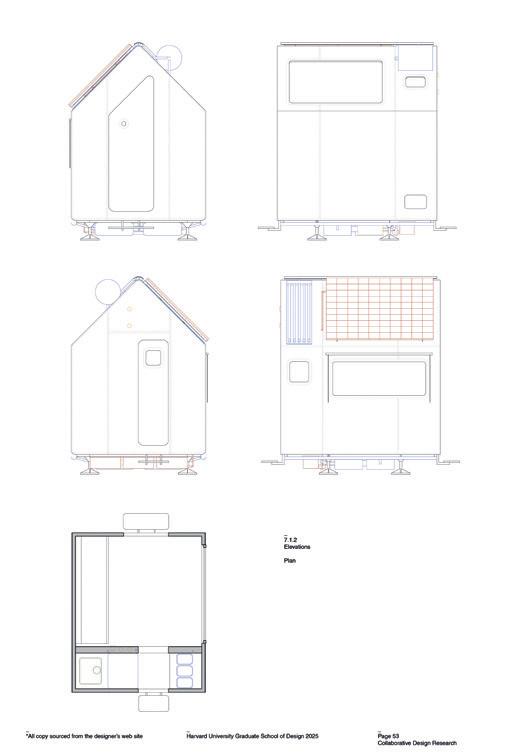

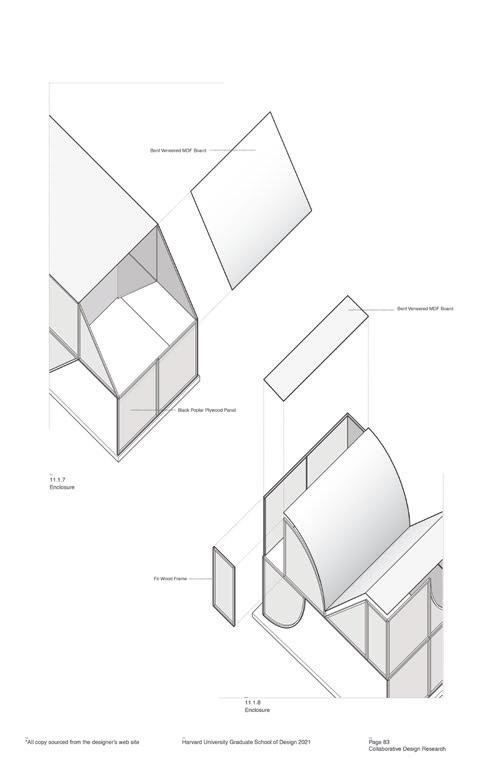

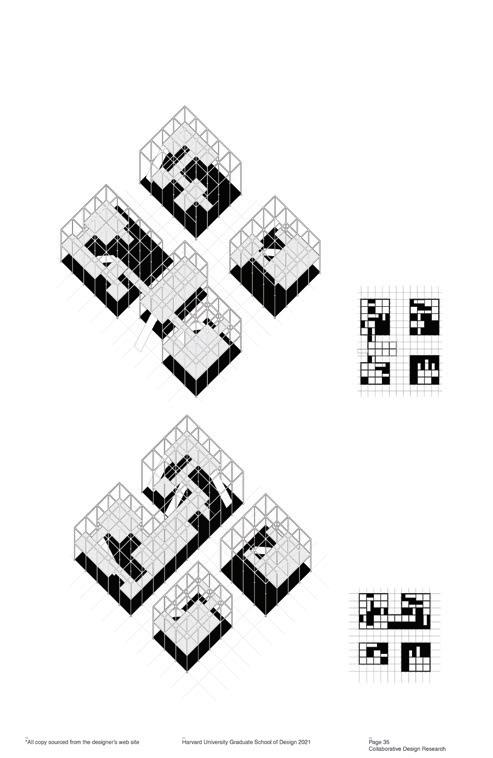

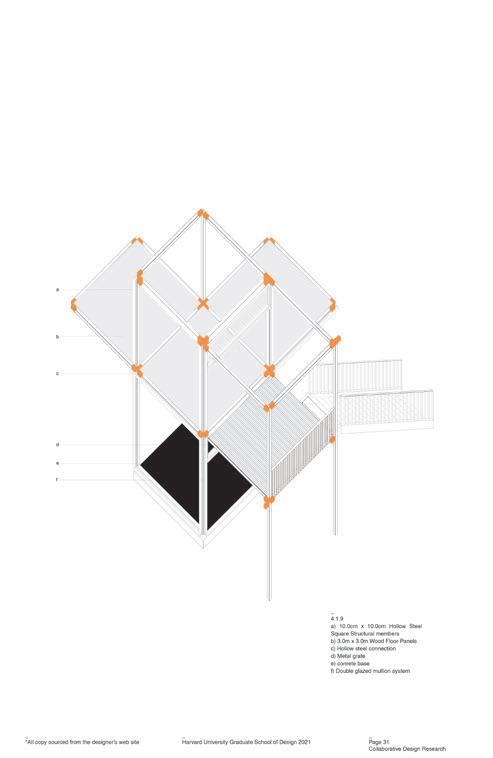

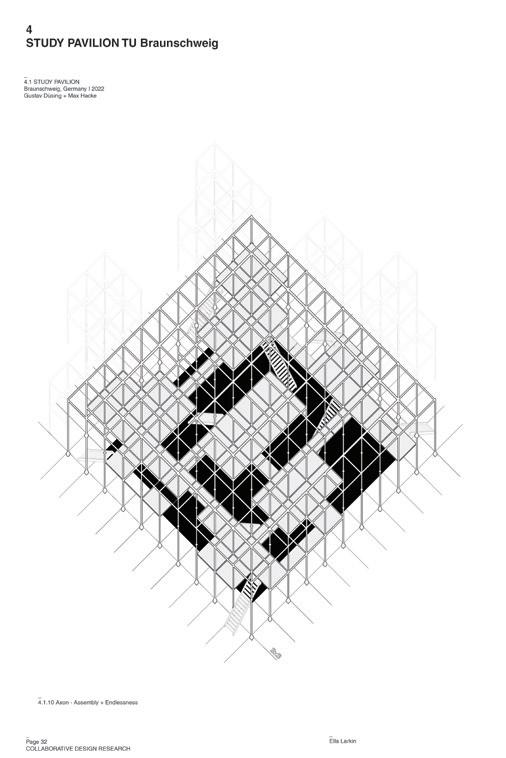

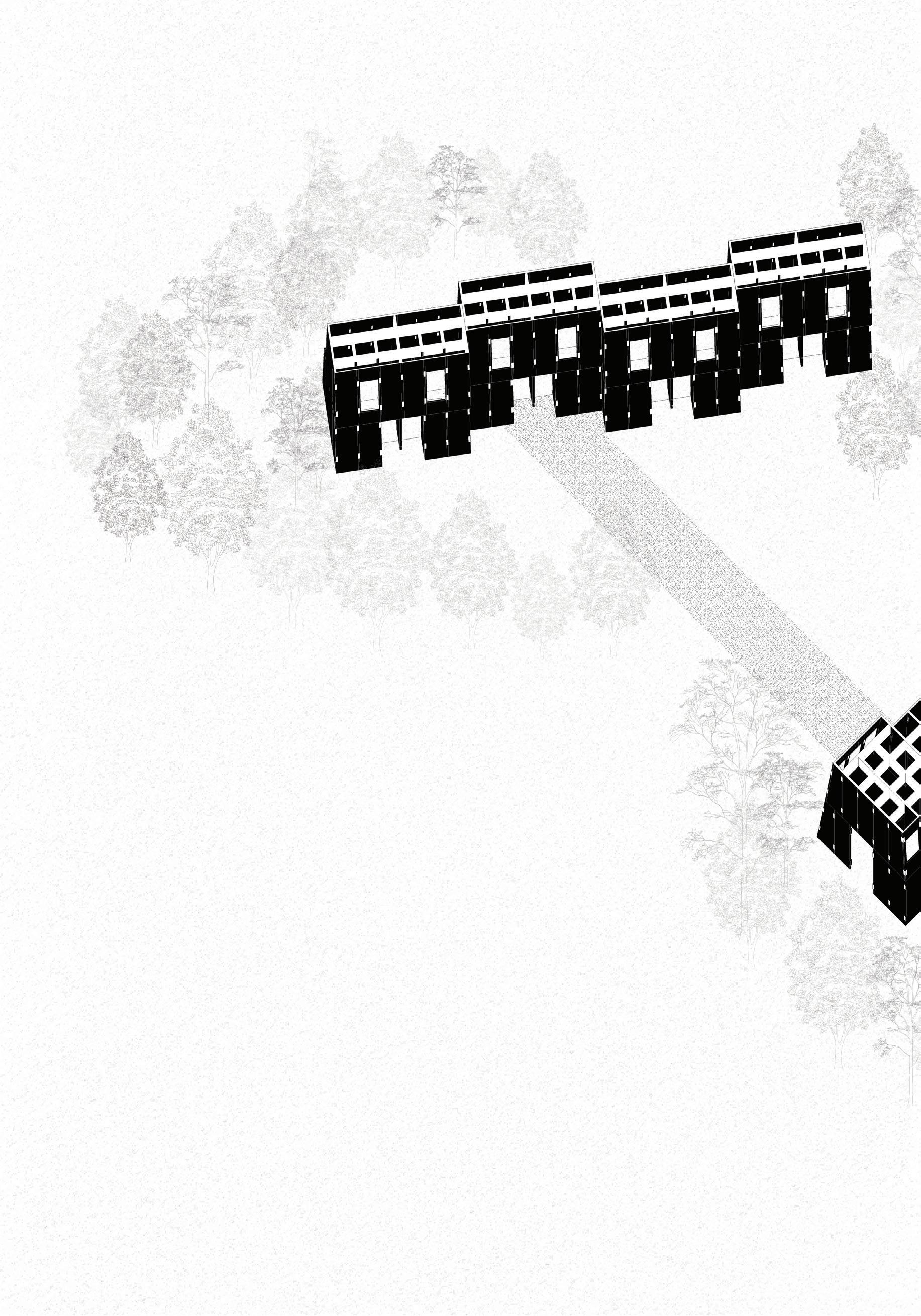

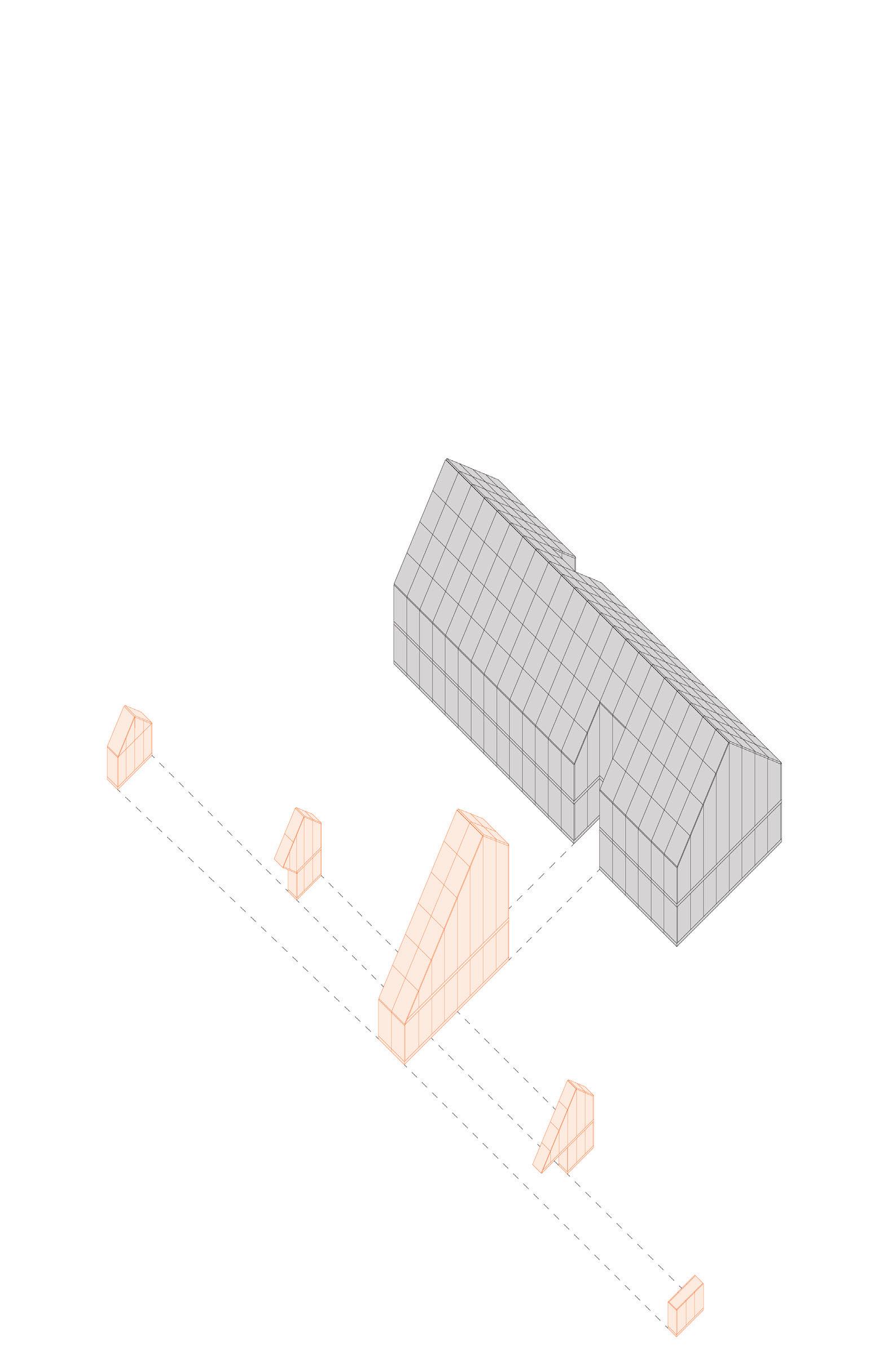

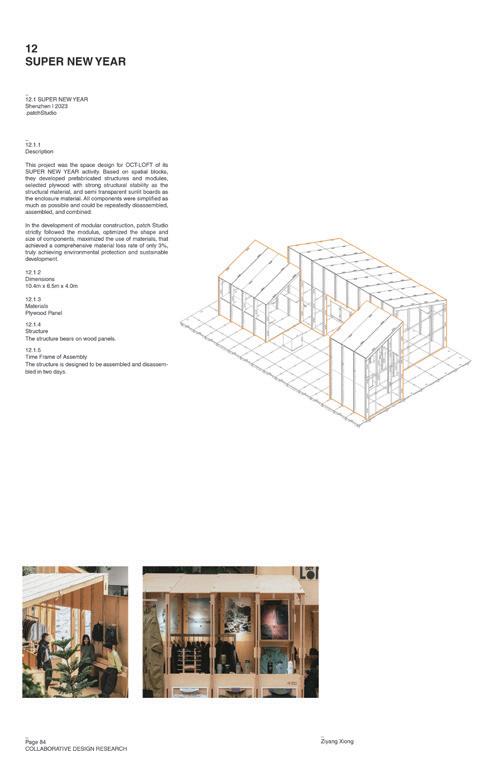

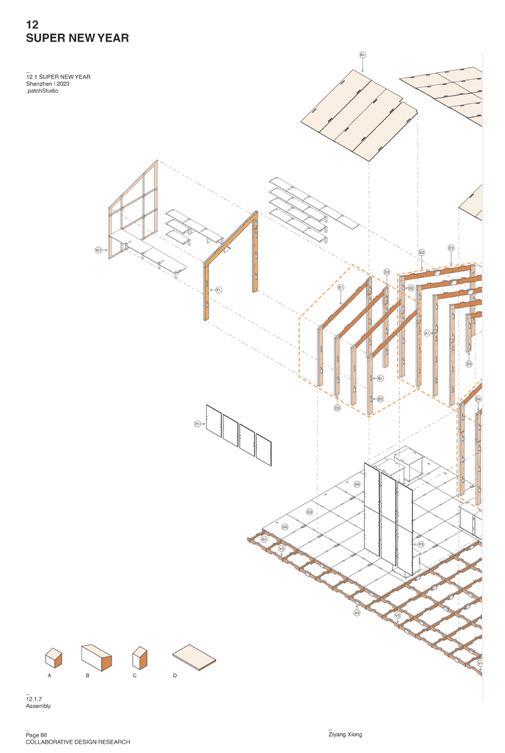

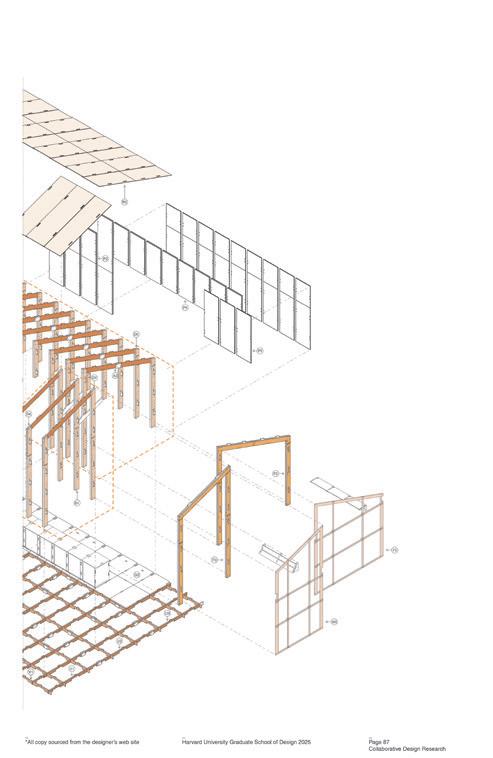

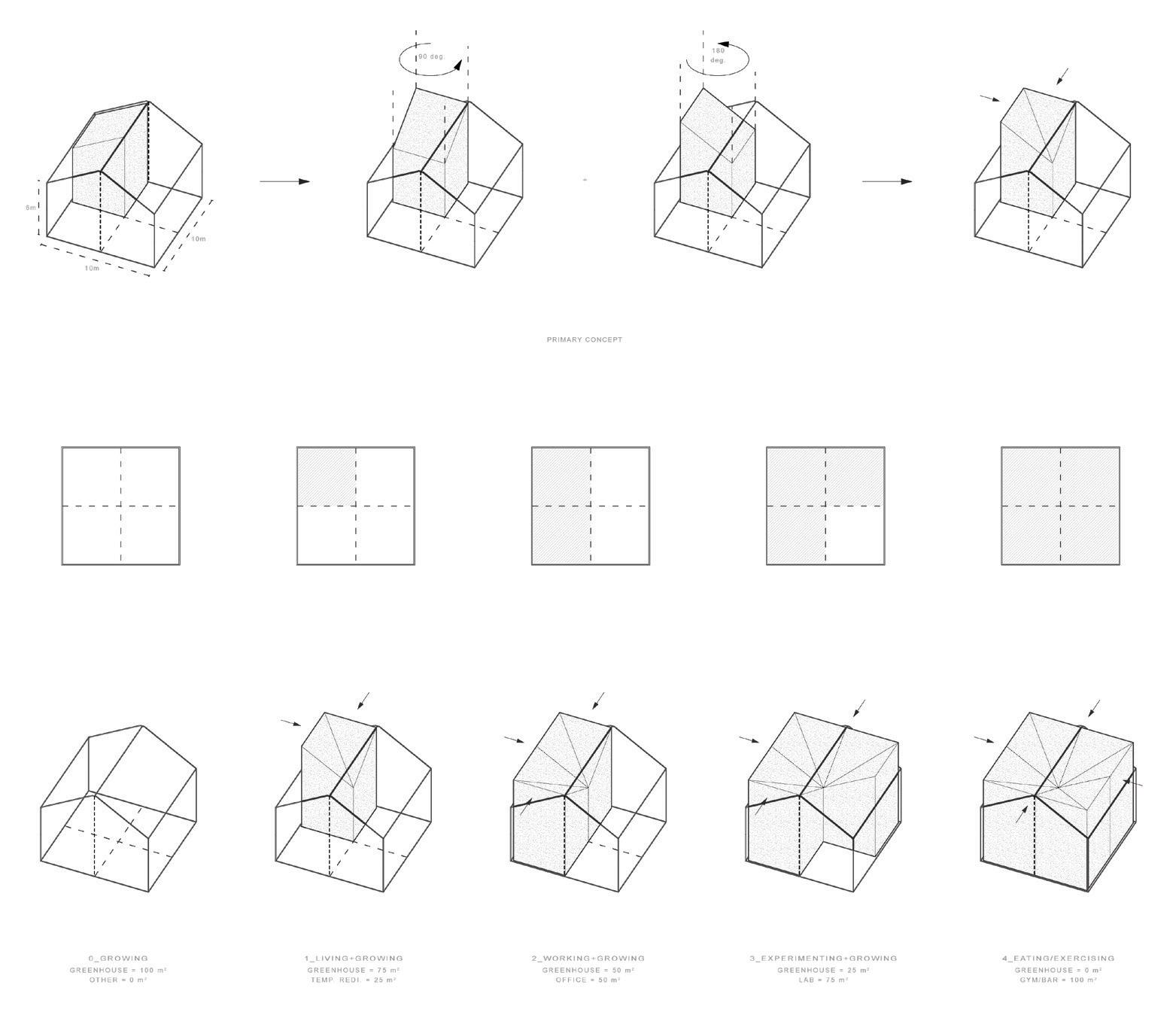

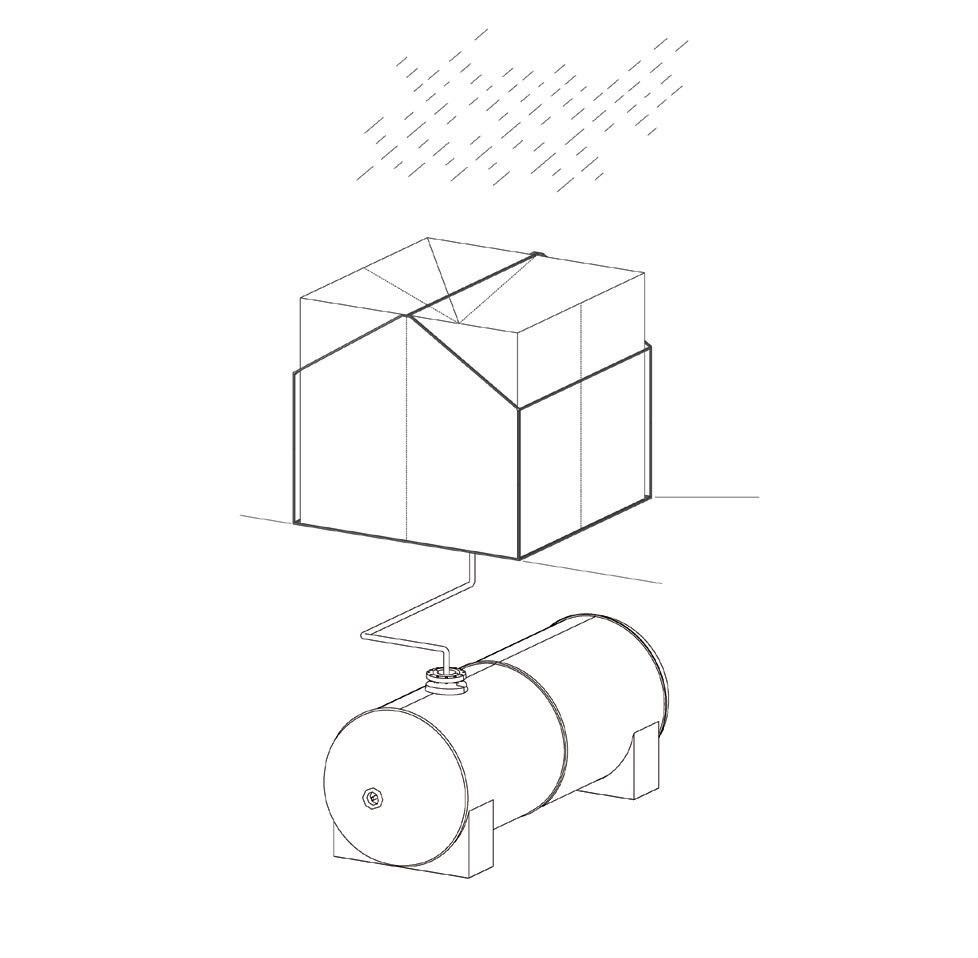

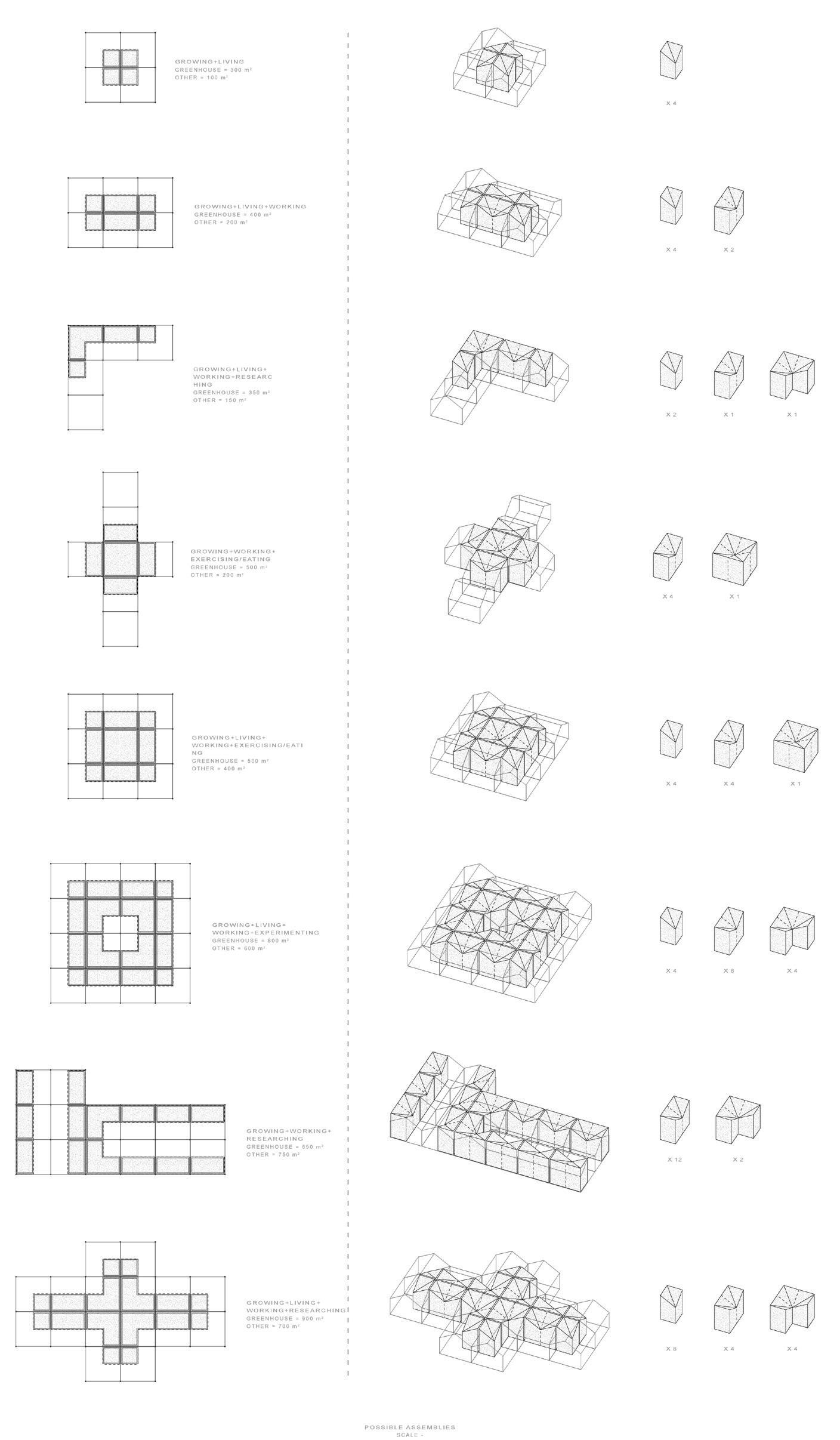

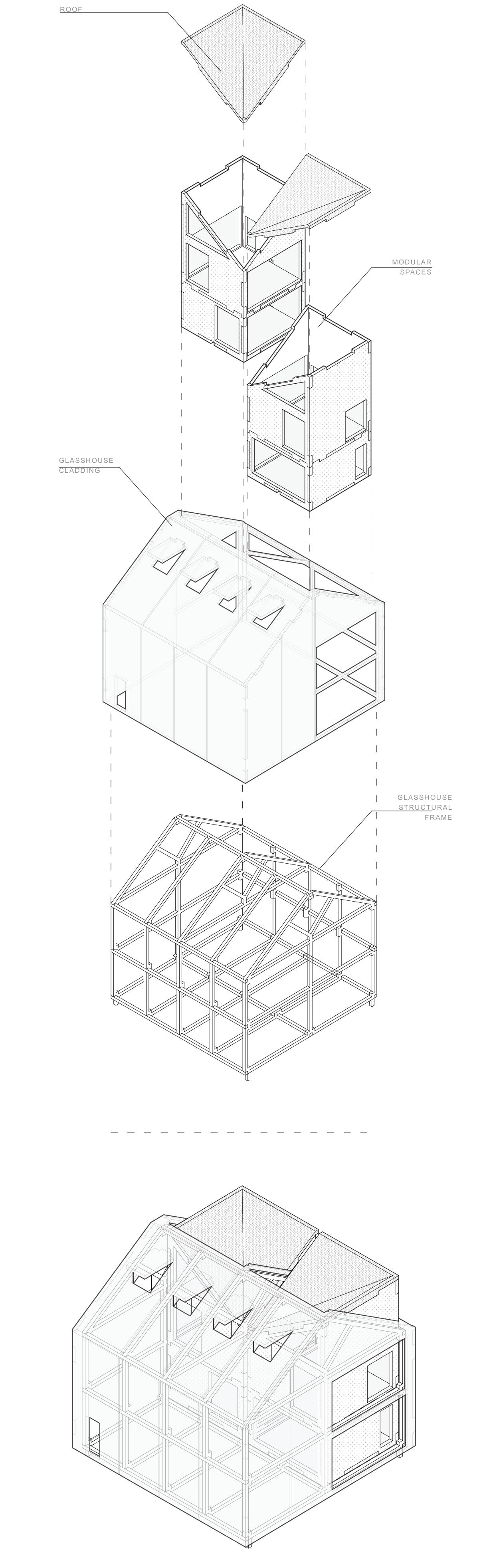

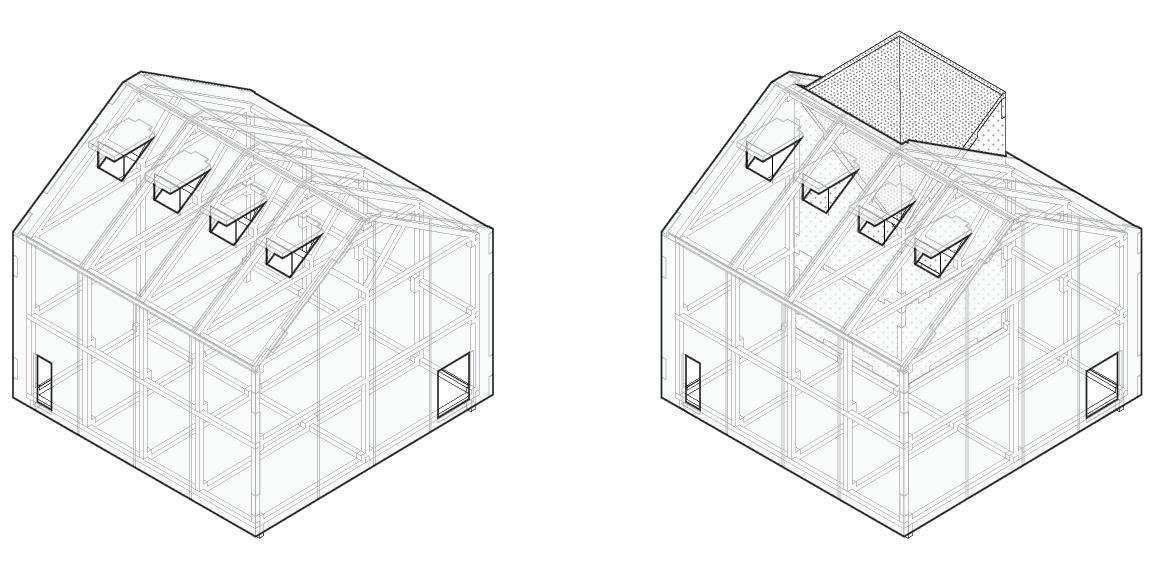

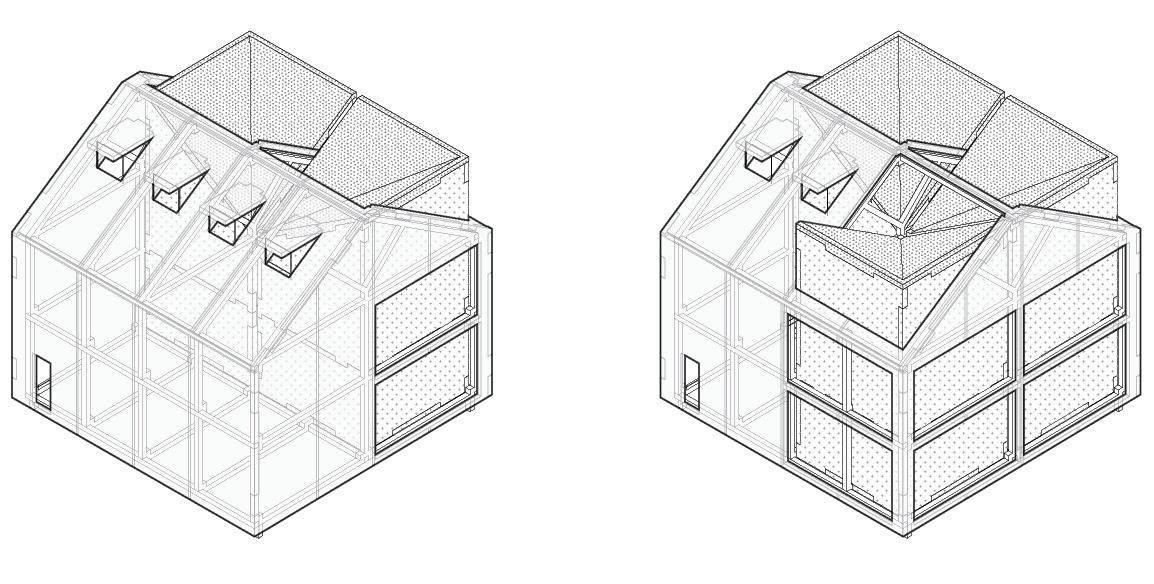

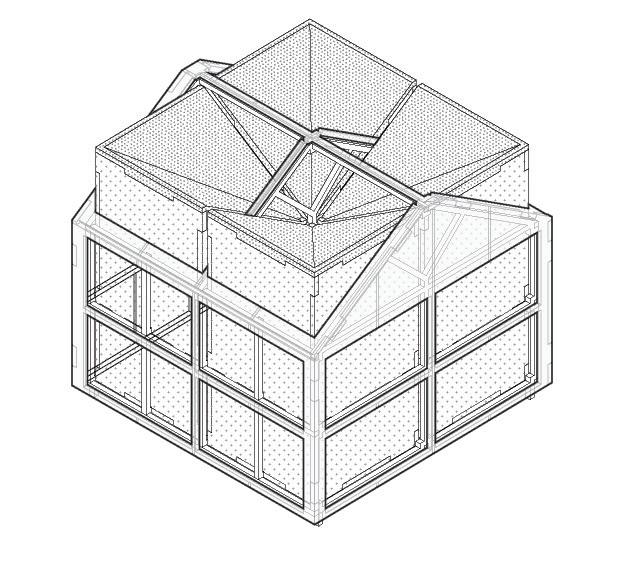

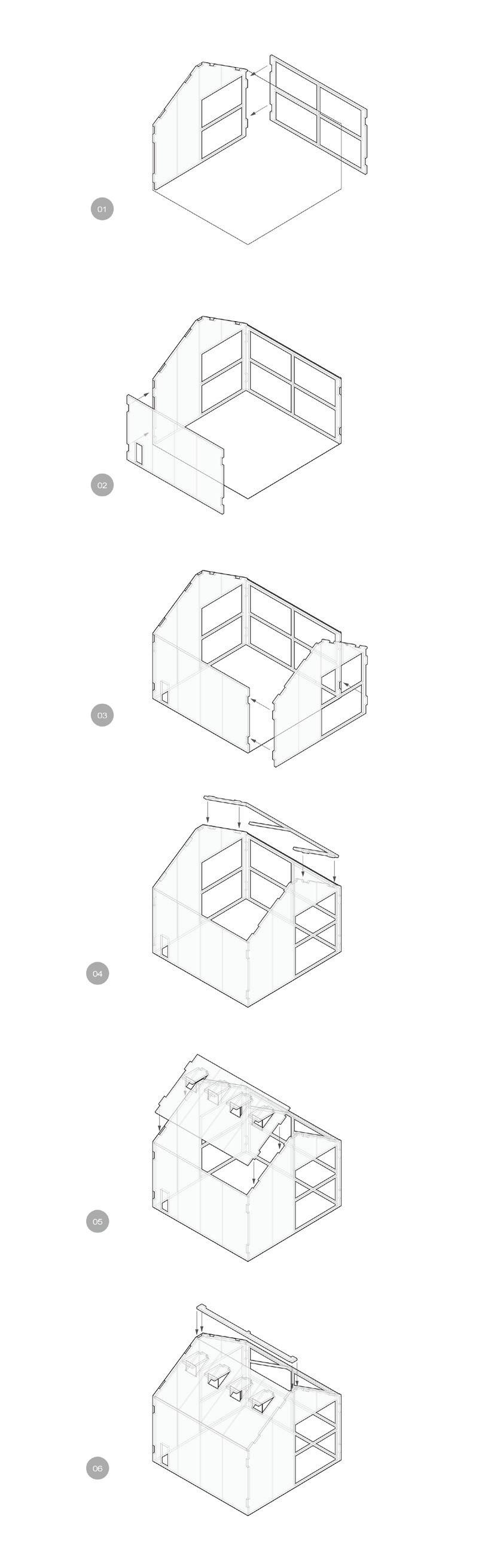

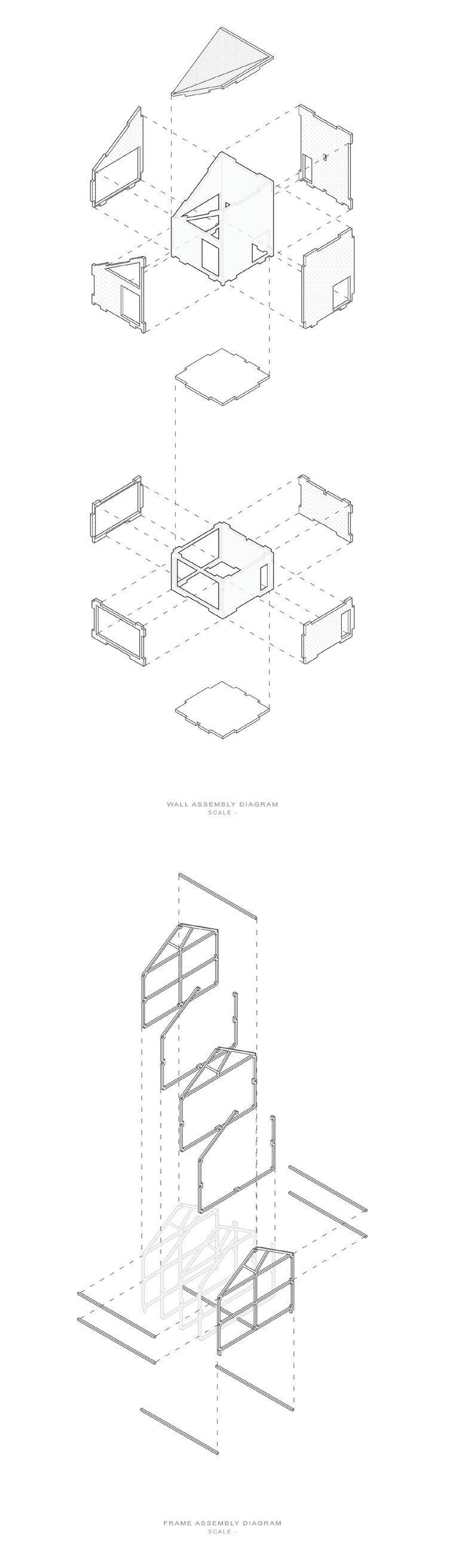

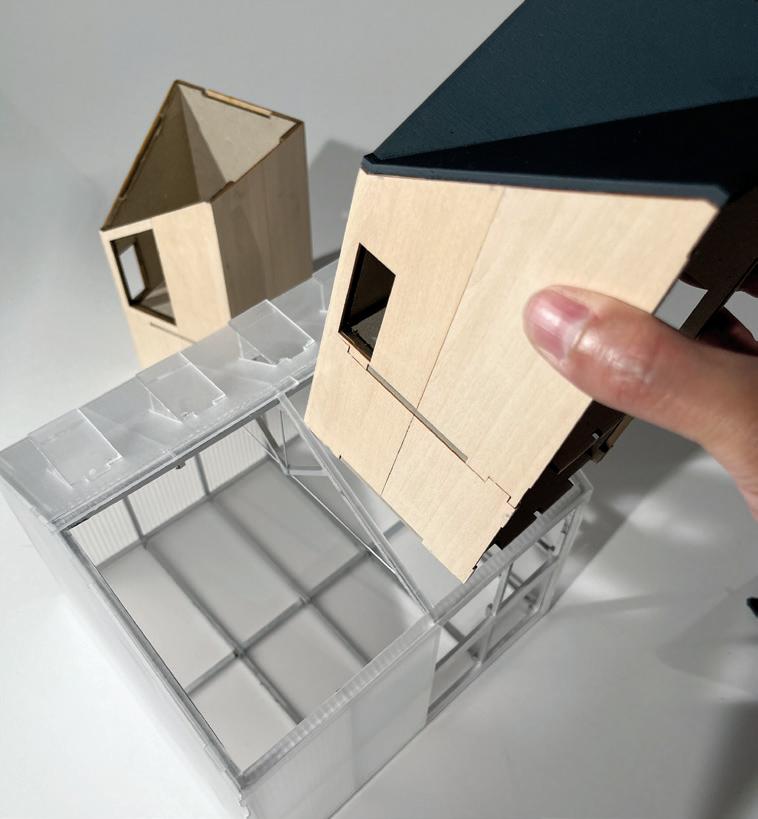

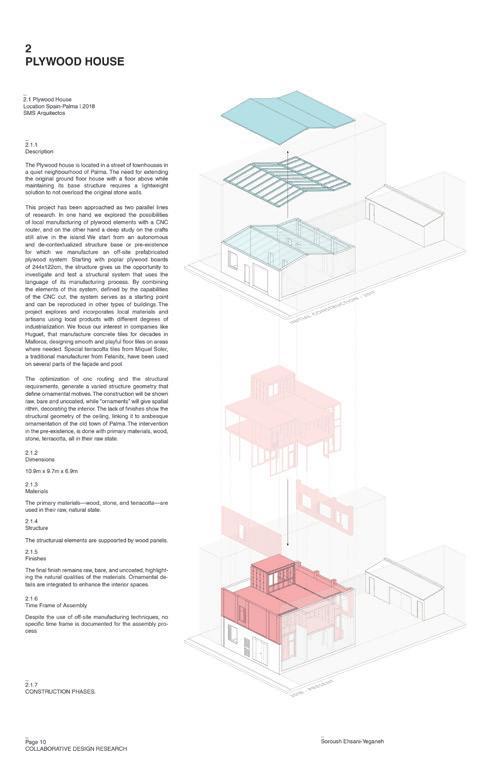

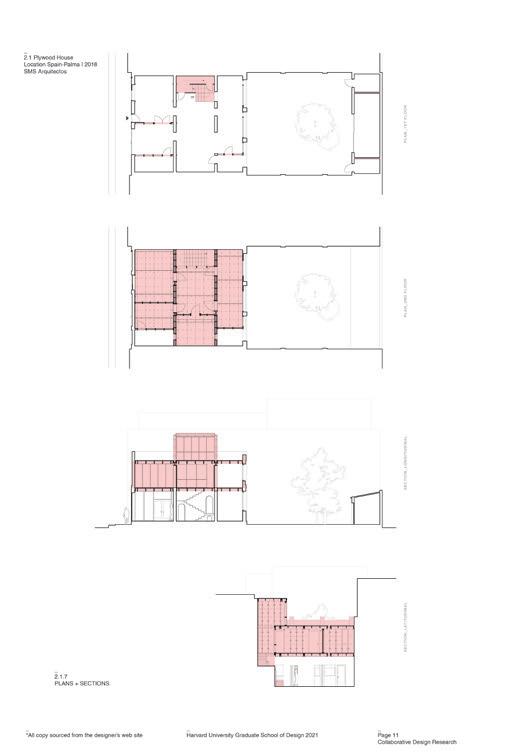

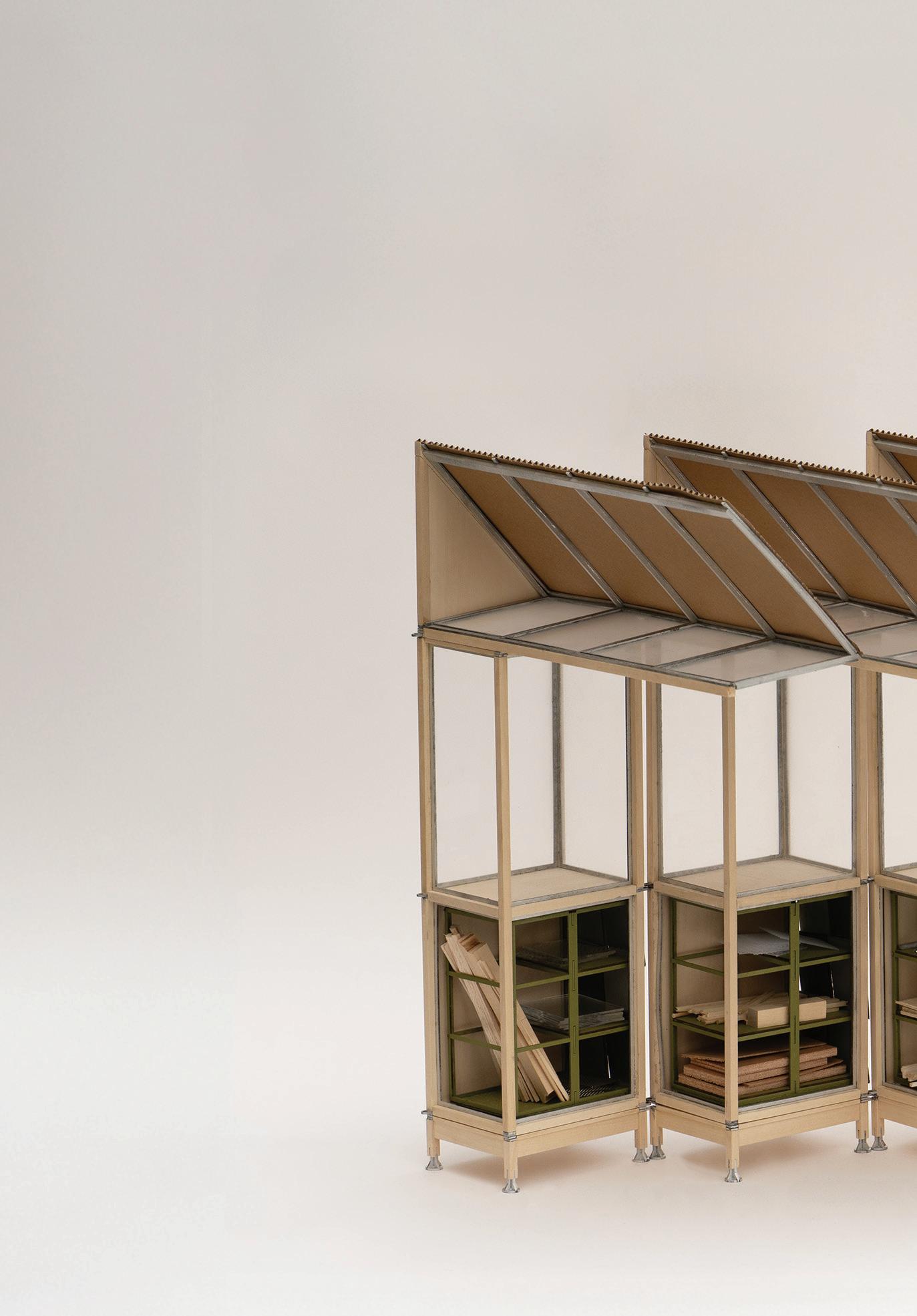

AgriLab Village is a speculative architectural project exploring the revitalization of agricultural knowledge and rural life in Asanokando, Japan. Traditionally, rural Japanese communities practiced occupational pluralism, combining farming with offfarm work. Today, this model is eroding as younger generations migrate to urban centers, threatening the continuity of agricultural expertise. In response, AgriLab Village proposes a new typology: a greenhouse-based experimental hub merging agribusiness, research, and communal living.

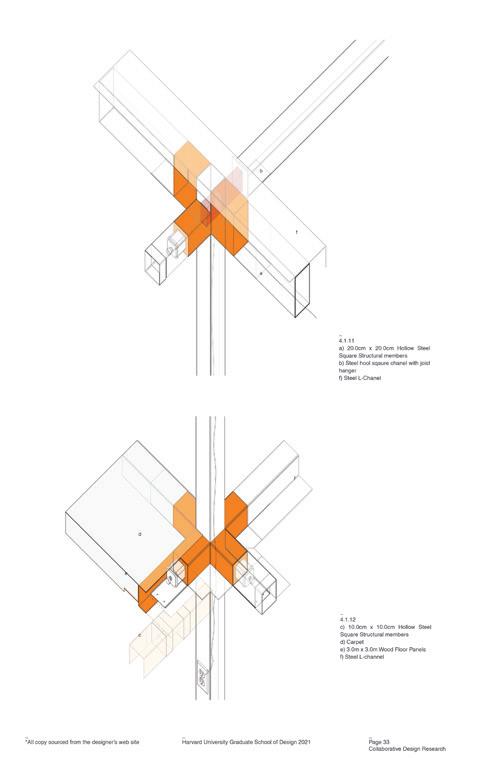

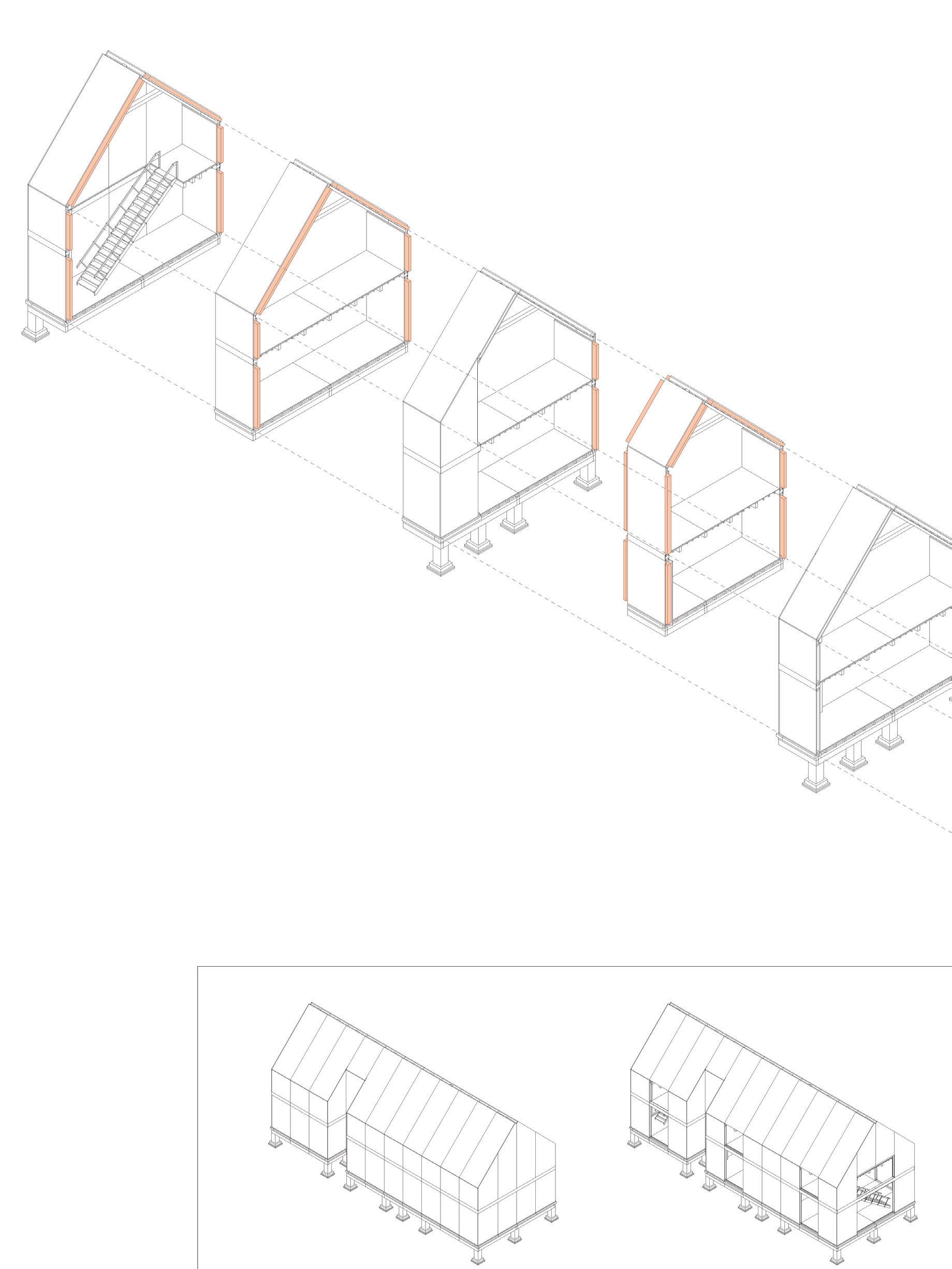

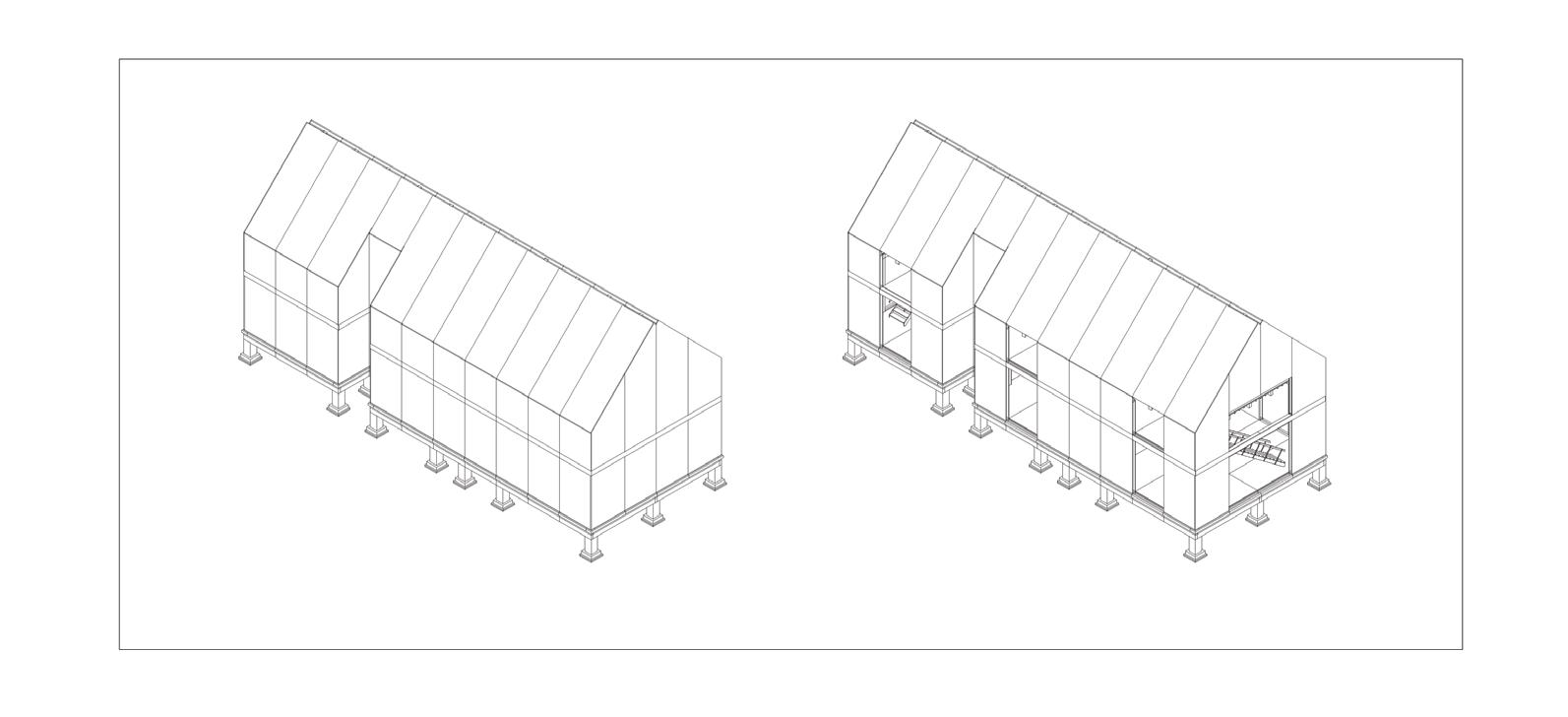

At the core of the project are modular greenhouse units that support diverse programs. Beginning with a 10x10-meter greenhouse, strategic subtraction and rotation transform portions of each module to host labs, residences, or communal spaces. These are aggregated into adaptable clusters, enabling flexible spatial configurations. The construction sequence involves building the greenhouse frame, applying cladding, inserting the secondary program block, and finishing with an inverted roof.

The program includes lab facilities, administrative offices, communal gathering areas, and short-term residences, all embedded within interconnected greenhouse structures. These serve as both spaces for experimentation and daily living. Residents—visitors engaged in agricultural research—are immersed in lab activities, each with access to a private garden within the greenhouse to test and apply knowledge firsthand. This proximity fosters continuous exchange between residents and researchers.

AgriLab Village proposes a model for rural regeneration through architecture that prioritizes knowledge production, community interaction, and agricultural innovation. It serves as a prototype for reclaiming rural relevance.

Above: Diagrammatic study of possible assemblies

Previous page: Modules and program Above: Unit typologies

following

Asanokanda, March 2025.

Asanokanda, March 2025.

Asanokanda, March 2025.

George L. Legendre

George L. Legendre is a London-based architect and educator. He is a Professor in Practice of Architecture at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) and a founding partner of the London-based practice IJP Architects (IJP).

The Future of Work I: Awaji-Shima

Instructors

George L. Legendre Report Design

Rishita Sen with George L. Legendre Report Editor

George L. Legendre with Rishita Sen

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah Whiting Chair of the Department of Architecture Grace LA

Copyright © 2025 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2025 by their authors.

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design 48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu

Special thanks to Dean Sarah Whiting and Chair Grace La for initiating this multi-year research program –and for giving me the opportunity to return to Japan as principal investigator of the inaugural semester. Special thanks to Pasona Inc chairman Yasuyuki Nambu for endowing the program through the establishment of the Nambu Family Design Studio Fund. Special thanks to senior directors Makiya Nambu and Keiko Okabayashi for their leadership. We are grateful to directors Sho Fukuda and Leon Yamashita for sharing the work of their respective departments. Finally we are indebted to staff members Tamoi Fuji, Gabriela Shimakawa, and Owissa Callista for their selfless support on the ground. At the GSD, many thanks to midterm and final review critics James Dallman, Iman Fayyad, Jenny French, Jon Gregurick, Grace La, Mohsen Mostafavi, Keiko Okabayashi, Riho Sato, Allen Sayegh, Michael Voligny, Sarah Whiting, and Adrian Wong. Special thanks to FabLab team Rachel Vroman, Minyoung Hong, and Leon Fong for their generous logistical help. Thanks to Teaching Assistant Rishita Sen ’25 for her key role in the design and production of this report. And a special mention for former GSD Assistant Dean for Alumni and Development Michael Voligny for his deep knowledge of Japan, and precious advice in all matters international.

George L. Legendre

Image Credits

The pictures of models included in the Projects section of the report are by the individual contributors. The illustrations of the main essay and the full-bleed image spreads punctuating the report are by principal investigator George L. Legendre.

Studio Report

Spring 2025

Students

Keane Chua, Soroush

Ehsani-Yeganeh, Elise

Hsu, Ella Larkin, Regina

Pricillia, Nicky Rhodes, Zachary Slonsky, Ann

Tanaka, Esteban Vanegas

Jr., Jeya Wilson, Lou Xiao, Ziyang Xiong

Harvard GSD Department of Architecture