INCREASING UNDERSTANDING OF ENHANCED INFLUENZA VACCINE PRODUCTS IN LONG-TERM CARE SETTINGS

Bene ts of Enhanced In uenza Vaccine Products

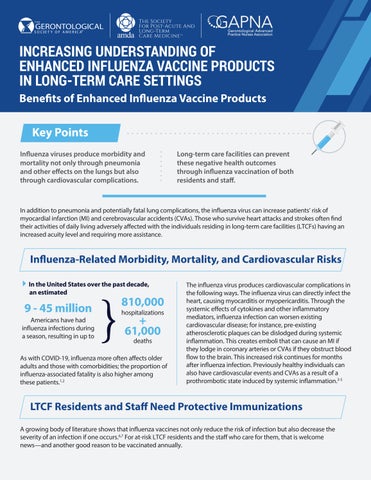

In uenza viruses produce morbidity and mortality not only through pneumonia and other e ects on the lungs but also through cardiovascular complications.

Long-term care facilities can prevent these negative health outcomes through in uenza vaccination of both residents and sta .

In addition to pneumonia and potentially fatal lung complications, the in uenza virus can increase patients’ risk of myocardial infarction (MI) and cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs). Those who survive heart attacks and strokes often nd their activities of daily living adversely a ected with the individuals residing in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) having an increased acuity level and requiring more assistance.

In uenza-Related Morbidity, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Risks

In the United States over the past decade, an estimated

9 - 45 million

Americans have had in uenza infections during a season, resulting in up to

810,000

61,000 hospitalizations deaths

As with COVID-19, in uenza more often a ects older adults and those with comorbidities; the proportion of in uenza-associated fatality is also higher among these patients.1,2

The in uenza virus produces cardiovascular complications in the following ways. The in uenza virus can directly infect the heart, causing myocarditis or myopericarditis. Through the systemic e ects of cytokines and other in ammatory mediators, in uenza infection can worsen existing cardiovascular disease; for instance, pre-existing atherosclerotic plaques can be dislodged during systemic in ammation. This creates emboli that can cause an MI if they lodge in coronary arteries or CVAs if they obstruct blood ow to the brain. This increased risk continues for months after in uenza infection. Previously healthy individuals can also have cardiovascular events and CVAs as a result of a prothrombotic state induced by systemic in ammation.3-5

LTCF Residents and Sta Need Protective Immunizations

A growing body of literature shows that in uenza vaccines not only reduce the risk of infection but also decrease the severity of an infection if one occurs.6,7 For at-risk LTCF residents and the sta who care for them, that is welcome news—and another good reason to be vaccinated annually.

In LTCFs, highly contagious viruses are quickly transmitted among people in con ned spaces and sharing common areas. Older adults, especially those with comorbidities, have high mortality rates from severe respiratory illness. Yet only about two-thirds of LTCF residents receive annual u shots, and among all health care work settings, LTCFs continue to have the lowest sta vaccination rates (67.9% in the 2018–2019 season).8

LTCF administrators, medical directors, and directors of nursing must set and enforce nursing home policies that keep residents and sta safe and healthy. Enhanced in uenza vaccines have an important role in accomplishing this goal.

Figure 1. Estimated Range of Annual Burden of In uenza in the United States Since 2010

*’The top range of these burden estimates are from the 2017-2018 u season. These are preliminary and may change as data are nalized Source: Reference 1.

Estimated U.S. In uenza Burden, by Season, 2010–11 Through 2019–20

Deaths

Hospitalizations

Illnesses

*Estimates for these seasons are preliminary and may change as data are nalized.

** 2019–20 data are incomplete. Shown are seasons-to-date gures through April 4, 2020. Only ranges of burden had been released; the midpoint of those ranges is depicted in the gure. The reported ranges for this season at the time this report was prepared were 39 million to 56 million infections, 410,000 to 740,000 hospitalizations, and 24,000 to 62,000 in uenza-related deaths.

Resources

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disease burden of influenza. April 17, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/index.html. Accessed May 18, 2020.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019–2020 U.S. flu season: preliminary burden estimates. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/burden/preliminary-in-season-estimates.htm. Accessed May 18, 2020.

3. Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):345–353.

4. Boehme AK, Luna J, Kulick ER, et al. Influenza-like illness as a trigger for ischemic stroke. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2018;5(4):456–463.

5. Schaffner W, McElhaney J, Rizzo A, et al. The dangers of influenza and benefits of vaccination in adults with chronic health conditions. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2018;26(6):313–322.

6. Thompson MG, Pierse N, Sue Huang Q, et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness in preventing influenza-associated intensive care admissions and attenuating severe disease among adults in New Zealand 2012–2015. Vaccine. 2018;36(39):5916–5925.

7. Arriola C, Garg S, Anderson EJ, et al. Influenza vaccination modifies disease severity among community-dwelling adults hospitalized with influenza. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65(8):1289–1297.

8. Bardenheier B, Lindley MC, Yue X, et al. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel — United States, 2018–19 influenza season. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 26, 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/fluvaxview/hcp-coverage_1819estimates.htm. Accessed June 10, 2020.