GREEN SPAIN REGION

EBRO RIVER VALLEY REGION

CATALONIA REGION

MEDITERRANEAN REGION

MESETA CENTRAL REGION

SOUTH REGION

ISLANDS REGION

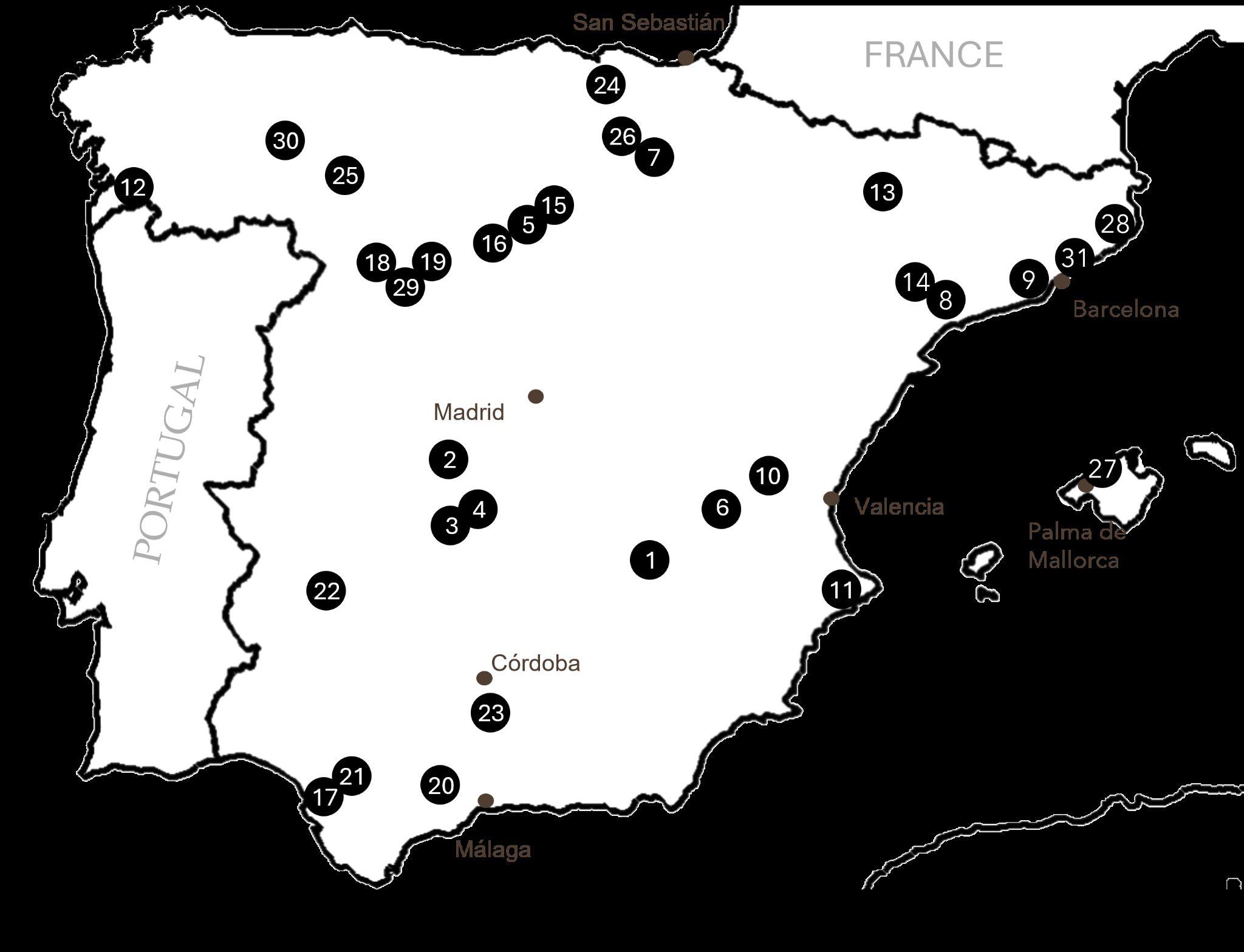

Welcome to The Terroir Workshop by Grandes Pagos de España. This study guide is a companion to the classes and includes key background information on GPE and Spain. To organize the course, we have divided Spain into eight regions according to similar historical, geographical and cultural characteristics. There is an introduction to each region that will enhance understanding of the elements of terroir covered in the classes, and is best read before attending.

The guide will be updated periodically with current information.

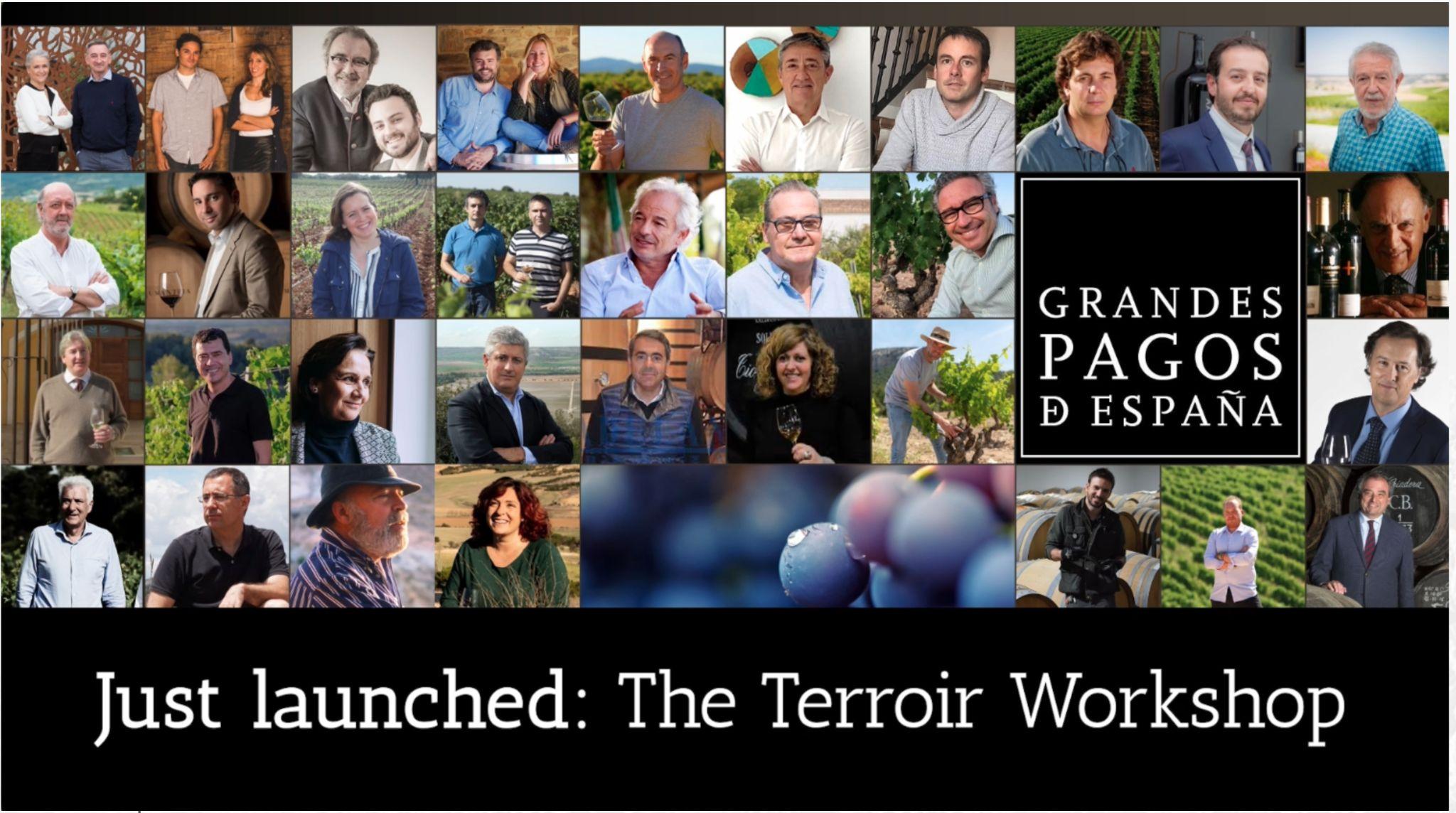

Founded in 2000, Grandes Pagos de España is a non-profit association of 31 prestigious wineries dedicated to single-estate production across Spain. Membership in Grandes Pagos is based on rigorous selection criteria for viticulture and winemaking excellence on the level of a pago, a delineated vineyard parcel that is the ultimate terroir designation in Spain. Grandes Pagos de España aims to defend the unique, terroir-driven personality of single-estate wines, to uphold and promote the ethos of Spanish winemaking, and to make wines of excellence in harmony with the soil, nature and climate of each vineyard. Just launched, The Terroir Workshop by Grandes Pagos de España (currently available in the U.S. and Mexico) explores Spanish terroir in the context of history, science, geography, language and people.

1. To make and promote pago wines of the highest quality, made with distinct personality and respectfortheirterroiroforigin

2. Todefendthecultureandqualityofpagowinesthroughouttheworld

3. TopreserveanddevelopthebesttraditionsofSpanishvineyardsandwinemaking

4. Toadvancethescientificandtechnicaldevelopmentofwinemakingandcultivationtechniques

5. Topromoteconstantinterchangebetweenmemberstoadvanceviticultureandwinemaking

Grandes Pagos de Castilla is founded by five estates 2000

Collaboration with Spanish government to add single estate wines (Vino de Pago) to national wine law 2003

Grandes Pagos de España is renamed and expands beyond Castilla with 12 member estates

Grandes Pagos has grown to 31 wineries TODAY

At the turn of the 21st Century, a group of five producers of single-estate wines came together with a shared vision and mission for the future of Spanish winemaking. The establishment of Grandes Pagos de Castilla in 2000 laid the foundation for a new association of winemakers dedicated to high-quality, single-estate wine production. By 2004, the group had grown beyond Castilla to 12 estates known as Grandes Pagos de España. The exponential growth in the years since is a testimony to the collective value of preserving terroir and single vineyard origins in modern winemaking: As of 2025, GrandesPagosdeEspañaincludes31wineries.

To be eligible for GPE membership, wines must come from an exceptional estate and single vineyard, have a track record of industry recognition for at least five years, and receive the highest ratings from established wine critics and competitions. New members must pass a rigorous inspection and quality testing process. Existing members are subject to annual blind tasting evaluations conducted by an independent External Expert Tasting Committee (CCEC). These evaluations ensure quality continually meets the GPE’ standards of membership, which can be revoked if a winerynolongermeetsthecriteria.

VinodePago isawineclassificationestablishedin2003bythe Spanishgovernmenttorecognizeselectestateswithspecialsoil structure. The Vino de Pago legal requirements are based primarily on soil composition. In contrast, GPE membership requires a track record of the highest quality as defined by benchmarks like style, balance, terroir reflection and outstanding winery values. Not all Vino de Pago wineries are GPE members (and vice versa), however, the two designations have a close relationship; many of the GPE founding members advocatedforthenationallegislationthatledtothecreationof theVinodePagodesignation.

In keeping with Grandes Pagos de España's maxim of maintaining the highest level of quality, personality and uniqueness of its member wines, an External Committee of Expert Tasters is entrusted with the continuous evaluation of all the wines of the associated wineries, which must be submitted at least onceayearoreverytimethereisachangeofvintage.

This is done by means of a blind tasting, requiring a minimumscoreof16pointsonascaleof20.

Grandes Pagos de España offers an extensive educational program to certify knowledge of Spanish terroir. GPE has forged relationships with leading sommelier and trade organizations, to support an expansive educational focus including Spanish terroir, history, culture and gastronomy supported by two levels of custom coursework for professionals.. GPE has just launched The Terroir Workshop to support globaleducationfortrade and consumers.

GPE membership builds community engagement and collaboration through a “network of knowledge” to exchange ideas. Exclusively for members, the program includes regular regional tastings, wine region immersion trips, winemaker collaboration, expert seminars and discussions on technical subjects, global exportsandmarketing.

GPE is committed to sustainability and environmental preservation. Many GPE estates are located in specially protected natural areas: 26 of the 31 member wineries practice organic viticulture (13 are certified), and three wineries practice biodynamic viticulture (two are certified). GPE provides resources and guidelines to reinforceresponsibleenvironmentalpractices.

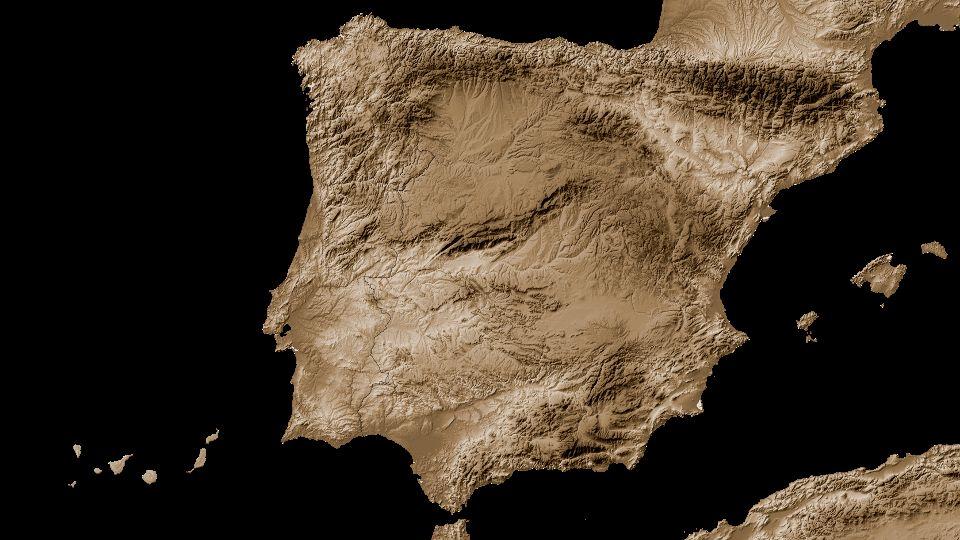

SpainisborderedtothewestbyPortugalandtothenortheast by France. From France, it is separated only by the small principality of Andorra and by the impressive Pyrenees Mountains. Spain’s only other land border is in Gibraltar to the south,anenclaveunderBritishrulethatbelongedtoSpainuntil 1713, until ceded to Great Britain after the War of the Spanish Succession. On all other borders, the Spanish mainland is surroundedbywater:theAtlanticOceantothenorthwestand southwest; the Mediterranean Sea to the east and southeast; and the Bay of Biscay, an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean, to the north. Other parts of Spain include The Canary (Canarias) Islands in the Atlantic Ocean, near the northwestern African mainland; the Balearic (Baleares) Islands in the Mediterranean; and Ceuta and Melilla, two small provinces in northern MoroccothathavebeenSpanishdomainsforcenturies.

Spainisarelativelysmalllandmass(similarintotalsurfacearea to the state of Texas) but its unique geography and climatic situationallowforconsiderableregionaldiversityinlandscape, culture,historyandevenlanguage.Forteachingpurposes,GPE groups Spain into 8 regions with common traits, as follows: Green Spain, Meseta North, Ebro River Valley, Catalonia, Mediterranean,MesetaCentral,SouthandTheIslands.

Spain is characterized by three distinct climate zones: maritime, continental and mountainous, defined by a range of humid, semi-arid and arid conditions. Overall, climate conditions are complex supporting a wide range of wine varietiesandstyles.Proximitytocounteringinfluencesfromthe Atlantic Ocean and North Africa expose winegrowers to both maritime and sub-Saharan influences. The northern Pyrenees and Cantabrian mountain ranges play an important role in the Spanish climate, holding the warm, dry subtropical airstream from Africa over Spain during the summer months and blockingmoisturefromreachingtheinterior.

InadditiontoVinodePago,Spainhasmanywinedesignations basedonsharedcriteriasuchasgeography,climateinfluences, style and cultural ties. These include the well-known Denominación de Origen (DO) classification, primarily delineated by geographic boundaries but which also includes Cava,theméthodetraditionelleforsparklingwinesapprovedin variouspartsofSpain.GPEisaninclusiveorganizationwithno requirementforotherclassificationamongtheirwineriesapart frommeetingtheorganization’sstrictcriteriaformembership.

Denominación de Origen or DO is the equivalent of the European Union classification Denominación de Origen Protegida (DOP)createdin2016.Eithertermmaybeusedlegally(andinterchangeably)onSpanishwinelabels,thougheventuallyDOP willbeusedexclusively.

Vinos de Pago: Thehighestcategoryforsingle-estatewines.Grapesmustbecultivatedexclusivelyfromthe pago.

Denominación de Origen Calificada (DOCa) or (DOQ in Catalan): wines at high levels of quality with a minimumof10yearsasaDO.SubjecttostricterregulationsthanDO,therearetwoinSpain:DOCaRiojaand DOQPriorat.

Denominación de Origen (DO): Quality wines from a delimited production area and with production standardscertifiedandoverseenbyalocalRegulatoryCouncil(ConsejoRegulador).

Vinos de Calidad con DO (VC): WinesfromageographicareaseekingfullDOstatus

VinodelaTierra(VdT): IndicaciónGeográficaProtegida(IGP)isthetermcreatedbytheEuropean Union,equivalenttotheSpanishVinodelaTierra(VdT).Bothtermscanbelegallyusedonwine labels.Thesewinesarehighquality,butregulationsarelessstringentthanaDO.Atleast85%ofthe productionmustcomefromtheprotectedzone,withupto15%fromotherareas.

VinoTinto,VinoBlancoorVinorosado:ThisistheformerVinodeMesa,ortablewinecategory. Winescanbesourcedfromanygeographicarea.

Due to its geographical location, Spain has a rich, often complex history with many overlapping cultural influences. FromtheRoman,GermanicandMoorishoccupationstothe Christian reconquista — to the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorshipofFranciscoFrancointoitsprosperousmodern era — Spain has been the site for some of history’s most dynamic fusions of culture, language and religion. The legacy of Spanish winemaking, equally fascinating, has followedthistrajectorythroughoutthecenturies.

Prehistoric traces of human occupation in Spain have been recorded as far back as 780,000 years, with the appearance of modern humans (H. sapiens) by 35,000 BCE. While there is evidence of grape cultivation between 4000-3000 BC, Spanish wine history was more formally established by 1100 BC when the Phoenicians founded the southwestern trading post of Cádiz. During classical antiquity, wine-growing culture took hold under successive colonizations by Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans. The native Iberian people trace their ancestry to the Spanish Ibero, the prehistoric people of southern and eastern Spain. Waves of migrating Celtic peoples from the 8th to 6th century BC also settled in northern and central Spain, with strongtiestoGalicia.Celt-Iberiancultureandlanguagewas defeated by Rome after 200 BC, who established Latin cultureasthedominantforce.

The Roman conquest of Iberia began in 218 BC, which led to RomandominationoftheIberianPeninsula(calledHispania)for more than 600 years. Under Roman occupation, Hispania developed a more centralized infrastructure and public works, suchasaroadsystem,aqueducts,theaters,bathsandthebasis ofacommonlanguage.RemnantsofRomaninfluencecanstill be found in Spain today, such as the aqueduct of Segovia. Under Roman rule, Spanish wine was widely exported and traded throughout the empire, with two principal wine-producingregionsinmodern-dayTarragonatothenorth andAndalucíainthesouth.

Throughout the 5th century, Roman rule began to destabilize as Germanic tribes crossed the Pyrenees. By 410 AD, the Visigoths,SueviandtheVandalshadgainedsignificantcontrol across the Peninsula. In 542 AD, Visigoth rulers established Toledo as the capital of their kingdom. The Visigoths were Christians who tolerated wine, but little is known about the viticultureofthisera.

In 711 AD, Spanish history took a significant turn when the Moors conquered the Peninsula from North Africa. For more than 700 years after, the Moors held the chief power over Al-Andalus, the name given to Muslim territory. Southern Spanish cities like Córdoba, Sevilla and Granada were the epicenters of Moorish influence, where the greatest concentrationofMoorishartandarchitecturecanstillbefound today. During this period, wine consumption was discouraged under Moorish law. However, in practice, many caliphs and emirs were known to own vineyards and drink wine, and wine productionandtradecontinuedwithnon-Muslimneighbors.

The Reconquista (or Reconquest), in medieval Spain and Portugal,referstoaseriesofcampaignsbyChristiankingdoms to recapture territory from the Moors. As Christian influence gradually rose across Spain through the Late Middle Ages, the widespread exportation and consumption of wine resumed, with Bilbao to the north as a booming trading port. The reconquista of Spain lasted for more than seven centuries before the 1492 marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella united the territories of Aragón and Castile, laying the foundation of a modern Spanish nation. The two monarchs completed the reconquistaandlaunchedtheSpanishInquisitiontopersecute, exile or convert Muslim and Jewish citizens. Ferdinand and Isabella also funded the voyage of Christopher Columbus to “discover”theAmericas,whichledtothecreationofaSpanish empireoverseas—andanewglobalexportmarketforwine.

ThediscoveryoftheAmericasusheredinagoldeneraof colonialexpansionandglobalpowerforSpain.Aspartof thecolonizationofindigenousterritoriesintheAmericas, conquistadors such as Cortés and Pizarro also brought EuropeanvinestotheNewWorld,asourceofnewfound wealth. The Spanish Empire continued to flourish under thereignofPhillipII(1556-98),whichestablishedMadrid as the new capital of Spain. In 1588, Phillip II launched the Spanish Armada with the intention of overthrowing Queen Elizabeth I’s Protestant rule in England. The Spanish navy lost badly, which marked the beginning decline of Spain’s financial prosperity. In debt, Spain grew more dependent on income from its colonies, including wine exports, but the emergence of growing wineindustriesintheNewWorldlowereddemand.Philip IIIandsucceedingmonarchsissueddecreesorderingthe uprooting of New World vineyards, which halted wine productioninthecolonies.

Spain’s financial decline was exacerbated by involvement in other international conflicts over the following centuries — such as the Thirty Years War, Franco-Spanish Wars and World War I — and ongoing domestic conflict between regions across Spain. As a result,theprogressofSpanishwinemakingfellbehind.In the mid-1800s, a phylloxera outbreak decimated other Europeanvineyards(includingwinemakingpowerhouses likeFrance)butmostlysparedSpain,whichusheredinan era of innovation and cross-cultural learning with Bordeaux, Champagne and other regions for Spanish winemaking. The phylloxera outbreak reached Spain in thelate1800s,resultinginconsiderablevineyardlosses, but somewhat contained by the emergence of treatment options such as rootstock grafting over the same time period. Despite political conflicts, some of Spain’s most historic wine estates were founded in this era. The end of the 19th century also saw the rise of Spain's sparkling wine industry with Codorniú’s developmentofCavainCatalonia.

In 1936, a military coup d’etat against the Second Spanish Republic signaled the start of the Spanish Civil War. Led by the fascist General Francisco Franco, Nationalist forces eventually defeated the Republicans and assumed governmental control in 1939. The chaos of the Spanish Civil War decimated vineyards and wineries throughout the country. World War II caused furtherdeclineinSpanishwineexports.Francoremained in power in Spain until 1975, and his dictatorship significantly delayed the country’s post-war development, notably in rural areas known for their viticulturalproduction.

FollowingFranco’sdeath,JuanCarlosIwascrownedKing of Spain in 1975, and the shift to a constitutional monarchy led to the creation of the modern Spain’s constitution in 1979. Spain is divided into 19 autonomías or independent states (examples include Castilla y León, Andalucía and Catalonia), and further divided into 50 provinces to oversee state-level and provincial administrative affairs. The national capital of Spain is in Madrid and the current President is Pedro Sánchez Pérez-CastejónfromtheSocialistParty.

Spain entered what is now the European Union in 1986, allowingforneweconomicopportunitiesforwinemakers andarenewedemphasisonqualitywineproduction.With Spanish borders open, winemakers were able to travel and study worldwide. New investment in viticulture and technologyalsofacilitatedqualitygrowth.Throughoutthe 1990s, the Spanish agricultural ministry oversaw the creation of multiple new DOs, allowing regional authorities under the Consejo Regulador system to implement standards including allowed varieties, yields, aging,irrigationandstyles.Bytheturnofthe21stcentury, the prevalence of premium wines began to outpace that ofgenericSpanishbulkwines.

Today, Spain is a global wine leader with the most vineyard surface of any wine-producing country and a reputation for a quality, terroir-driven culture epitomized by classifications such as Vino de Pago. With its vibrant culture, art and history, Spain is also an emerging destination for enotourism with significant investment in local tasting rooms, lodging, hospitality and transportationnetworkstohostwinelovers.

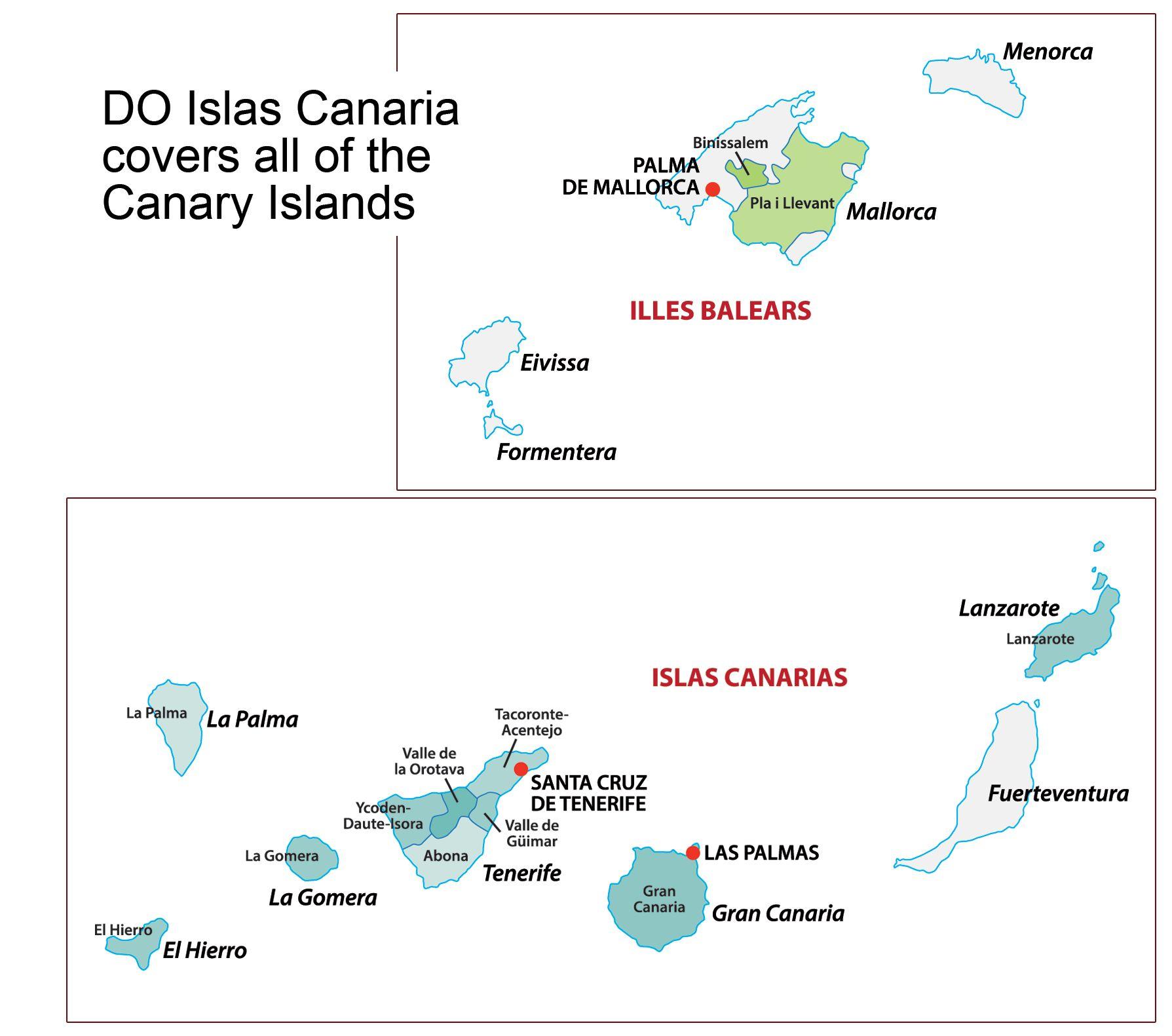

Established as an autonomous community in 1982,TheCanaryIslands(IslasCanarias)consist of an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, with the nearest island 67 miles (108 km) off the northwestAfricanmainland.TheCanaryIslands are located about 60 miles west of Morocco and include the Spanish provinces of Las PalmasandSantaCruzdeTenerife.Itscapitalis Santa Cruz de Tenerife. Island councils or Cabildosgoverneachofthesevenmainislands: El Hierro, Fuerteventura, Gran Canaria, Lanzarote,LaGomera,LaPalmaandTenerife.

Spain’sprincipalisland groups, which include the Canary Islands and the Balearic Islands,encompasssomeof the most unique and challenging terroir in the country, if not theworld.Therichhistories of these two distinct island groups inform modern-day winemaking practices, includingworkingdiligently to protectrare,indigenous grape varieties.

Established as an autonomous community in 1983,TheBalearicIslands(IslasBaleares)arean archipelago in the western Mediterranean Sea that share the Spanish province of the same name. The archipelago is located 50 to 190 miles (80 to 300 km) east of the Spanish mainlandandconsistsoftwogroupsofislands. The larger eastern group forms the Balearics proper and includes the principal islands of Majorca (Mallorca) and Minorca (Menorca) as wellasthesmallislandofCabrera.Thewestern group, the Pitiusas, includes the islands of Ibiza (Eivissa)andFormentera.Palmaisthecapitalof the Baleares as well as its military, judicial, and ecclesiastical center; its government includes the island councils of Mallorca, Menorca, and Ibiza-Formentera.

The Canary Islands’ first inhabitants were the Guanches, a Berber people who were conquered by the Spanish in the 15th century. The aboriginal occupants of the Canaries, the Guanche and Canario, belonged to a Neolithic, monotheistic culture with its own written alphabet. The descendants of the Guanche and Canario are now assimilated into the general population of the Canaries. The Canaries have been overrun by different cultures throughout history, including the Arabs, Genoese, Mallorcan, Portuguese andFrench.In1404,JeandeBéthencourtbecameking of the islands, completed the conquest of Lanzarote, Fuerteventura,andElHierro,andestablishedabaseon theislandofLaGomera.Hisrulewaslaterovertakenby the Portuguese. The 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas settled the Castilian-Portuguese conflict and established Spanish sovereignty over the Canaries. The remaining islands were conquered by 1496. During this time, the Canaries also became a crucial Spanish base on sea routes to the Americas, including as a rest stop for Christopher Columbus’s fleets. In 1927, the Province of Canary Islands was divided into two provinces, and in 1982,itsautonomouscommunitywasestablished.

The Balearic Islands also have a long and fascinating history of overlapping cultural influences, international conflict and piracy. One of the first known civilizations on the islands, the prehistoric Talayotic civilization (named for its rough stone towers called talayots), has had a lasting archaeological impact on the area. Discoveries such as bronze swords, single and double axes, and figures of bulls and other animals all point to various influences throughout history. Archaeological records indicate at least 2,600 years of human settlement, and the islands were successively ruled by Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Moors, and Spaniards from 526 to 1833. The raids of Barbary pirates delayed settlement along the coast until at least the 19th century. Since then, the spread of tourism has led to a higher concentration of population along the coastal areas. A statute of autonomywasproposedin1931,butwasnotpassed until1983.

The Canary Islands and The Balearic Islands each have many microclimates that vary between islands, though theirlocationinsouthernwatersmeanstheysharesome common climatic factors. The Canary Islands are the most tropical of Europe’s wine regions, located at a latitudeofroughly28°N.Thealtitudeofthestone-terrace vineyards can stretch up to 3,280 feet. Mount Teide, Spain’s tallest peak, is located in Tenerife, and has some ofEurope’shighestvineyards,twodistinctclimaticzones, and five DOPs. Old phylloxera-free vines from the Canaries can date back 200 years. The Balearics have a contrasting terrain with rolling hills, plateaus, and lowlands,aswellasextensiveplainsinMenorca.

Soil composition varies among the two island groups. The Canary Islands’ topography is influenced by mercurial geological conditions such as volcanic eruptions,landslidesanderosion—leadingtolightstone soils, heavy basalt rock, and different proportions between sand and clay. For example, in Lanzarote, vines are planted in crater-like pits called hoyos, and then dug deep into soil containing thick layers of water-retaining volcanicash(picón).Protectivelava-stonewallsshieldthe

The Canaries’ eastern island group (Lanzarote, Fuerteventura Island, and six islets) is of an older geological formation with a lower, more uniform altitude and an arid, desert-like climate. The western isles (Tenerife, Gran Canaria, La Palma, La Gomera, and El Hierro) have higher and steeper elevations and a greater varianceinmicroclimates.Northerntradewindsfromthe Atlantic called the Alisios, bring cool temperatures, moistureandhumiditytotheislands.Annualrainfallislow and rarely exceeds 10 inches (250 mm). Due to their volcanic conditions and extremely hot, dry climate, The Canary Islands are considered one of Spain’s most extreme terroirs. The Balearic Islands climate is Mediterranean, with a moderating influence from the summer’s Embat winds to mitigate scorching temperaturesandcarrymoisturefromtheMediterranean Sea, retained in the soils. Annual precipitation rarely exceeds18inches(450mm).

TheCanaryIslands’culturehaslongrevolvedarounditsrich agriculture. Wine sourced from unirrigated slopes was its stapleproductuntil1853,andbananasandsugarcanewere also major exports for the islands’ economy. The Canaries’ economy now relies primarily on its tourist industry, which first saw a rapid influx around the 1950s. Today, the Canaries receive nearly 12 million tourists a year, a volume thathasraisedconcernsaboutenvironmentalsustainability on the islands, with Las Palmas and Santa Cruz de Tenerife as the main hubs during peak tourist season (December throughMarch).

The Canaries’ local cuisine is largely seafood-based as well as wine-centric. It’s history as a port on the way to the Americas also had a strong influence on ingredients. Peppers,potatoes,bananasandtomatoesbroughtonships from America thrived in the islands. Common dishes include roasted fish, chicken and beef stews, potatoes (papas arrugadas, wrinkled potatoes) and garlic. A unique productoftheareaisgofio,asweetcorn-basedflourfound in many dishes. Mojo, a sauce used in cooking and alongside dishes, also originated in the Canaries. It is made from a base of olive oil with peppers added along with garlic, pimentón and other spices. Perhaps the best kept gourmet secret of the Canaries´ are the outstanding cheeses. Various types from goat, sheep or cow’s milk reflectoldtraditionsandsome areprotectedbyDOs.Look fornameslikeMajorero,PalermoorFlordeGuía.

While the Canaries have experienced many cultural and religious influences throughout history, Roman Catholicism has remained the prevalent religion in the archipelago for over five centuries. The dialect spoken on the Canaries is similar to that of Andalucía, the language of the islands’ initialsettlers.

Each of the Balearic Islands has its own individual culture with several overlapping cultural influences, from Roman ruins to Arab baths to Georgian architecture to Catholic cathedrals. Mallorca has a long and vibrant tradition of fine art,literatureandmusic,asitscapitalPalmadeMallorcahas welcomed modern artists, writers, and musicians for years. Other artistic additions like concerts, art shows, operas, literature,andtheaterperformancesthroughouttheyear

help to enliven the Balearics’ cultural scene. Mallorca’s most famous site is its Catedral, a large Gothic building andmuseumlocatednearthewater.

The Mediterranean cuisine of the Balearics is also unique, featuring several dishes rich in vegetables, cereal and legumes. Popular dishes include ensaïmada, a lard-based pastry sprinkled with powdered sugar; sobrasada, or raw, cured sausage made with ground pork, paprika and other spices; tombet (or tumbet), a traditional vegetable dish with layers of sliced potatoes, aubergines and red bell peppers; and Máo cheese producedontheislandofMenorca.

Like the Canaries, Catholicism has remained the predominant religious influence across the Balearics. As in mainland Spain, the Balearic Islands have celebrated numerous traditional Roman Catholic religious festivals forcenturies,ofteninterwovenwithfolkcustoms.Some longstanding cultural traditions include the winter festival of Sant Antoni, a fiery celebration featuring caperrots(characterswithverylargeheads)anddimonis (demons), as well as songs around bonfires on the ximbomba, an old instrument made of lambskin and cane. The colorful Ball dels Cossiers is a group of traditional dances celebrated in several villages. Catalan and Spanish are the Balearics’ official languages, although English and German have grown in popularity withtheriseoftourism.

The Balearic Islands These Mediterranean islands havetwoofficialwineDOs:PlaiLlevant(introducedin 2001)andBinissalem-Mallorca,bothofwhichareon the island of Mallorca. The latter was the islands' first DO title, and the first ever granted outside the Spanishmainland.AlthoughtherearejusttwoDO's,a number of VT-classified zones are spread across the other islands, including Ibiza VT, Formentera VT, Isla de Menorca VT, Mallorca VT and the encompassing Illes Balears VT. The majority of the vineyards of DO Binissalem-Mallorca are on gently rolling slopes made up of limestone-rich soils, which help retain moisture. This is essential for the grapes during the scorchingsummers,whicharethebiggestchallenge for grape production in the area. Conditions suit the local grape Manto Negro, often compared to Garnacha, which produces aromatic wines with velvety tannins. In blends, it is valued for adding ripe fruit character without adding tannins. Mostly these wines are best consumed within a few years, but are age-worthy if cultivated in poor soils with low yields. Local wine laws dictate that red wines produced in the Binissalem-Mallorca DO must contain at least 30% Manto Negro; whites must contain 50% of Prensal Blanc or Moscatel. Pla i Llevant is a DOP winegrowing zone on the island of Mallorca in the Balearic Islands. It occupies the southeastern half of the island. Limestone-enriched clay soils and the Embat winds shape the region's wine styles, often described as fruit-driven and mouth-filling with smoothtannins.Mallorca'snativePrensalBlanc(Moll) grape accounts for the majority of white Pla i Llevant wine, although Moscatel, Macabeo, Parellada and Chardonnayarealsoused.Mostredwinesarebased on local varieties such as Fogoneu (which once dominated the island's vineyards), Callet and Manto Negro.

TheCanaryIslands TheIslandssitatalatitudeof roughly 28°N, making them the most tropical of Europe's wine regions. Tenerife, the Canaries' largestislandandhomeoftheMt.Teidevolcano, houses half of the region's DOs: Abona, Tacoronte-Acentejo, Valle de Guimar, Valle de la Orotava and Ycoden-Daute-Isora. The remaining designationscovertheislands(intheirentirety)of ElHierro,GranCanaria,LaGomera,LaPalmaand Lanzarote. DO Canary Islands is a catch-all designationforwinesfromanyislandthatdoesn’t fallunderalocalDO.

Each area has a unique microclimate and soil composition, lending to distinctive wines with signature mineral notes. The altitude of the stone-terrace vineyards is vital and for the majority,itrangesfrom1,640to3,280feet(500 to 1,500 meters) – sometimes even higher. This ensuresthatfreshnessandacidityaremaintained in the grapes. Listán Blanco (aka Palomino) and Listán Negro are the most widely planted grapes on the islands. Others include white wine grapes Malvasía Volcánica, Malvasía Aromática and Albillo Criollo; along with red wine grapes Negramoll, Vijariego Negro and Baboso Negro. On Lanzarote, Malvasía Volcánica is used to produce their famous sweet Malvasía, known for itslongagingcapability.

DO Abona 2,965 acres (1,200 ha)

DO El Hierro

DO Gran Canaria

DO Islas Canarias

DO La Gomera

511 acres (207 ha)

605 acres (245 ha)

618 acres (250 ha)

296 acres (120 ha)

DO La Palma 1334 acres (540 ha)

DO Lanzarote

DO Tacoronte-Acentejo

4,942 acres (2,000 ha)

5,985 acres (2,422 ha)

DO Valle de Güimar 1566 acres (634 ha)

DO Valle de la Orotava

984-5,577 ft. (300-1,700 m)

410-2,297 ft. (125-700 m)

985-2,625 ft. (300-800 m)

164-4,921 ft. (50-1,500 m)

984-2,297 ft. (300-700 m)

656-4,921 ft. (200-1,500 m)

656-1,640 ft. (200-500 m)

164-3,281 ft. (50-1,000 m)

164-4,921 ft. (50-1,500 m)

840 acres (340 ha)

DO Ycoden-Daute-Isora 3,954 acres (1,600 ha)

Varies by elevation: Mediterranean to mountain

Moderate to cool according to altitude

Mediterranean with Atlantic influence

Varies

Moderate subtropical with Atlantic influence

Temperate Atlantic, varies according to elevation and topography

Subtropical semi-arid Mediterranean

Mild Atlantic

Varies by elevation. Generally mild, dry.

328-2,953 ft. (100-900 m)

164-4,593 ft. (50-1,400 m)

Warm, Atlantic influence

Mediterranean in La Marina; continental in Vinalopó

DO Binissalem

1359 acres (550 ha)

DO Pla i Llevant

1,161 acres (470 ha)

230-459 ft. (70-140 m)

0-328 ft. (0-100 m)

Mediterranean

Mediterranean

Chalky sands at lower elevations, clay in higher areas

Listán Negro, Negramoll, Moscatel Negro, Tintilla,

Listán Blanco, Gual, Verdello, Malvasía, Sabro, Bermejuelo

More whites than reds. Rosado permitted.

Volcanic, sandy

Volcanic sands and rock

Varies

Steep, terraced vineyards with volcanic soil

Steep, terraced vineyards with volcanic soil

Listán Negro, Vijariego Negro, Baboso Negro Vijariego Blanco, Bermejuelo, Baboso Blanco, Gual

Listán negro, Negramoll, Tintilla, Malvasía Rosada

Malvasía Rosada, Moscatel Negro,

Listán Prieto, Listán Negro, Tintilla, Castellana Negra, Negramoll, Vijariego, Bastardo Tinto

Malvasía Volcánica, Gual, Bermejuelo, Vijariego, Albillo, Moscatel de Alejandría

Sabro, Bermejuela, Forastera Blanca, Doradilla, Gual, Verdello, Vijariego, Malvasía Aromática, Malvasía Volcánica, Listán Blanco

Listán Negro, Negramoll, Castellana, Tintilla Forastera Blanca, Listán Blanco, Marmajuelo, Malvasía

Listán negro, Bastardo Negro, Malvasía Rosada, Moscatel Negro, Negramoll

Red clay and sand covered by thick layers of volcanic ash (called lapilli), rock Listán Negro, Negramoll

Red volcanic; permeable and rich in minerals

Volcanic in origin. Sandy areas at low and middle altitude; clay soils at high altitude

Listán Negro, Negramoll

Listán Negro, Malvasía Rosada, Negramoll, Tintilla

Listán Blanco, Albillo, Bujariego, Gual, Malmsey, Sabro, Verdello

Malvasía Volcánica, Listán Blanca, Burrablanca, Breval, Diego, Pedro Ximénez

Gual, Malvasía, Listán blanco and Marmajuelo

Listán Blanco, Malvasía, Moscatel, Gual, Vijariego, Verdello

Primarily young, fresh whites. Red, sweet, fortified permitted

Young, fresh reds and whites.

Reds, whites, rosados, sweet and fortified in a wide range of styles.

Primarily young, fresh whites. Red, sweet, fortified permitted

Young reds, whites, rosados. Well-known for sweet Malvasia, Vino de Tea (aged in pine barrels)

Predominantly Malvasia in styles from dry to sweet, sparkling. Rosados, reds permitted.

Mainly young and barrel aged reds. Whites, rosados permitted.

Mostly white in various styles including sparkling. Reds, rosados increasing.

Volcanic sand and clay over volcanic bedrock Listán Negro, Malvasía Rosada, Negramoll Gual, Malvasía, Verdello, Vijariego, Listán Blanco Red, whites; rosados permitted.

Volcanic ash, rock

Tintilla, Listán Negro, Malvasía Rosada, Negramoll, Baboso Negro

Limestone with abundant gravel, rocks Manto Negro, Callet, Tempranillo, Syrah, Gorgollassa

Red limestone-rich clay

Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Callet, Syrah, Ull de llebre, Manto Negro

Listán Blanco,

Prensal Blanc, Parellada, Macabeo, Chardonnay, Moscatel de Alejandría, Moscatel de Grano Menudo

Prensal Blanc, Macabeo, Chardonnay, Giró Blanc

80% vineyards planted to Listán Blanco. Whites, reds, rosados in a wide variety of styles.

Minimum 30% Manto Negro in reds; minimum 50% Prensal Blanc or Moscatel in whites. Rosados, sparkling.

Ripe, soft reds. Whites, rosados, sparkling permitted.