Business Process Outsourcing and Shared Service Centres: –

Business, Operational, and Contractual Risks and Opportunities at a Crossroad

1 Introduction 3

2 What is BPO outsourcing and which processes are typically outsourced? 4 3 Captives, BPO or BOT solutions 4

4 AI, captives and BPO 7

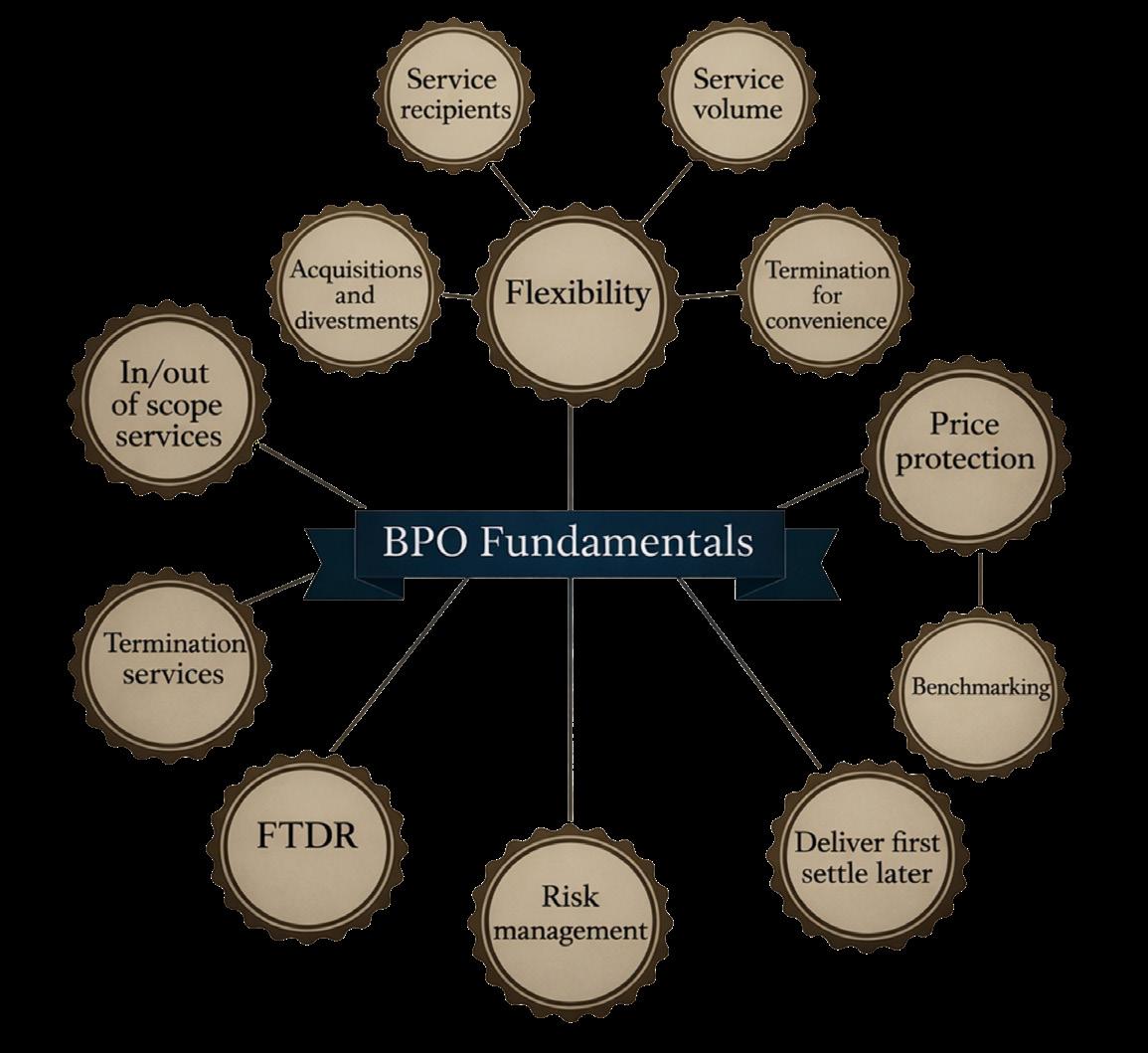

5 Key commercial issues 9

6 Key practical challenges when contracting 13

7 Key legal issues 14

8 Contract issues: BPO is “just” outsourcing so get the outsourcing fundamentals right 16 9 Gorrissen Federspiel’s BPO outsourcing team 20

1 Introduction

It has been more than 10 years since we published our first BPO best practice guide. Since then, many Nordic companies across all sectors have used business process outsourcing to leverage labour arbitrage and cut costs. BPO agreements have largely been successful, though some deals have unravelled or encountered difficulties during initial transition phases.

Over the past decade, BPO providers have acquired relatively few customer-owned captive service centre operations in India or Eastern Europe. The number of shared service centres operated as internal captives remains high in the Nordics compared with the penetration of externally outsourced IT and BPO adoption rates in the UK and US.

During the same period, BPO providers have established large service centres in Eastern Europe with language capabilities covering all Nordic languages.

Today, both external BPO and captive shared service centres face the same fundamental challenges: inflation and wages in Eastern Europe are rising at levels that will prove difficult, if not impossible, to offset through further optimisation. Meanwhile, investments in artificial intelligence-driven automation remain uncertain and substantial.

AI will undoubtedly drive significant changes to the BPO industry, which has hitherto relied largely on labour arbitrage. Those BPO providers and captives that successfully cannibalise their current labour-intensive business through the use of AI will come out on top.

The important questions to ask right now are:

• How quickly can we exit Eastern Europe, and where should we relocate given geopolitical risks and instability?

• Who is best positioned to implement AI-driven automation – providers or captives?

• Is it time to leave the captive shared service strategy and rely on BPO instead?

In this best practice note we provide reflections on these salient questions and provide an overview of the general aspects of BPO, which we hope can inspire further strategising with our clients.

But we would also like to be clear:

• the business case for BPO has never been stronger,

• it is too early for the customer side to bear the risk of AI transformation alone,

• first time BPO customers wishing to outsource should aggressively seek higher warranted savings than in the past,

• existing deals should be renegotiated and prolonged to allow for AI driven transformations to be financed and investment costs recouped by the service provider, and

• existing captive shared service centres must carefully evaluate the long term viability of a captivebased strategy balancing significant short to medium term gains achievable through divestment and outsourcing against the long term benefits of fully controlling internal business processes.

Copenhagen, January 2026

Ole Horsfeldt

Tue Goldschmieding Partner, Gorrissen Federspiel Partner, Gorrissen Federspiel

2 What is BPO outsourcing and which processes are typically outsourced?

At its core, business process outsourcing (“BPO”) involves transferring management of a business process or function to a third-party provider that the customer has previously handled internally.

Put simply, BPO saves companies money through labour arbitrage and the service provider’s superior ability to transform work processes through deep domain expertise and technology and deliver equivalent or improved output using fewer resources.

The following business processes are generally outsourced:

a. Finance (accounting, billing, accounts payable, accounts receivable, reporting etc.);

b. Human resources (administration and payroll etc.);

c. Procurement and logistics (packing, warehouse management etc.);

d. Administration (audit, tax etc.); and

e. Help desk and support services.

The captive shared services model enjoys high penetration in the Nordic market. For companies that have not yet invested substantially in shared service centres, BPO is increasingly viewed as a less costly alternative that requires no capital expenditure and can be implemented more rapidly.

Surveys by leading consultancies generally show that the top 5 per cent of captive shared service centres outperform external service providers. However, on average the BPO industry comfortably outperforms shared service centres on total cost of ownership and service level performance.

3 Captives, BPO or BOT solutions

3.1 Understanding the models

A captive shared service centre represents an internal operation, typically established in a lower-cost jurisdiction such as Eastern Europe or India, where a company consolidates and manages its own business processes using its own employees and infrastructure. By contrast, BPO is the transfer of a business process or function in its entirety to a third-party provider.

Between these two models sits the build-operate-transfer (“BOT”) solution, which offers a hybrid approach. Under a BOT arrangement, a service provider establishes and operates a dedicated service centre on the customer’s behalf for a defined period, after which ownership and operational control transfer to the customer, converting the operation into a captive. This model allows organisations to benefit from the provider’s expertise and speed to market whilst ultimately retaining long-term control and ownership. A variation of the BOT model is the build-operate-transform-transfer (“BOTT”) model. The idea is that the service provider will not only establish a robust captive but in the process of doing so also fundamentally transform work processes, use of technology, and, where relevant, also the output to become of higher quality or value.

3.2 Key differences and trade-offs

Control

and governance

The primary advantage of captives is control. Captive centres offer complete control over operational decisions, process design and data handling. Outsourced BPO necessarily involves ceding operational control to the provider, with governance exercised through contractual mechanisms rather than direct management authority. BOT and BOTT arrangements provide evolving control over time, with the organisation progressively assuming greater involvement as the transfer date approaches.

Capital requirements and financial structure

Captives require substantial upfront capital investment – typically several million euros for meaningful scale –with the organisation bearing full financial risk. Outsourced BPO converts capital expenditure into operational expenditure, eliminating upfront capital requirements and transferring investment risk to the service provider. BOT arrangements involve lower initial capital requirements than pure captives, with the service provider funding the build phase and recovering costs through service fees.

Implementation speed to operational capability

Establishing a captive centre typically requires 12-18 months from initial decision to stable operations. BPO providers can typically commence service delivery within three-six months (after a three-six months’ negotiation period), leveraging existing infrastructure and trained personnel. BOT arrangements fall between these extremes.

Scalability and volume flexibility

Captives face inherent challenges managing volume fluctuations, with the organisation bearing the full cost of excess capacity during downturns. BPO arrangements offer greater flexibility, with providers able to redeploy staff across their client base. BOT models may ideally provide flexibility during the service provider-operated phase, though this advantage disappears following transfer to captive status.

Access to expertise and innovation

Leading BPO providers invest heavily in process optimisation, automation and AI capabilities, spreading these investments across their client base. Captive centres must fund all innovation investments directly, which is challenging for smaller operations lacking the scale to justify significant automation investments. BOT arrangements provide access to provider expertise during the operating phase, though organisations must build equivalent capabilities internally following transfer.

Risk profile

Captives concentrate operational risk within the organisation, including recruitment, compliance and geopolitical risks, but avoid supplier dependency. Outsourced BPO transfers many operational risks to the provider but creates supplier dependency risk and may have the same or different geopolitical risks. BOT arrangements involve evolving risk profiles, with supplier dependency during the provider-operated phase shifting to operational risk following transfer.

Captive shared service BPO

BOT (and BOTT)

What is it?

Ownership & control

An internal operation, typically established in a lower-cost jurisdiction such as Eastern Europe or India, where a company consolidates and manages its own business processes using its own employees and infrastructure.

Organisations maintain direct oversight of their processes, data, and personnel.

The transfer of the management of a business process or business function to a third-party external provider that has (until the outsourcing) been handled by the customer itself.

Third-party service provider owns and operates.

Capital investment Requires substantial capital expenditure. No capital expenditure commitment.

Speed to market Slower to establish (12-18 months from decision to stable operations). Organisation must build all capabilities from scratch.

Cost structure

Fixed costs remain largely unchanged regardless of volume. Organisation bears full cost of underutilised capacity. Potential for lower unit costs at scale.

Faster to implement (three-six months to service commencement). Third-party service provider leverages existing infrastructure and trained personnel.

Variable cost structure scaling with consumption. Per-transaction, per-FTE or fixed-fee pricing. Organisation pays provider margin but avoids capacity risk.

A hybrid approach where a service provider establishes and operates a dedicated service centre on behalf of the customer for a defined period, after which ownership and operational control transfer to the customer, effectively converting the operation into a captive.

Provider establishes and operates initially, then transfers ownership and operational control to customer.

Organisations avoid upfront capital investment during the operating phase.

Allows organisations to benefit from the third-party provider’s expertise and speed to market (six-nine months to service commencement).

Variable costs during operating phase. Transitions to captive cost structure post-transfer with associated fixed cost exposure.

Dimension Captive shared service BPO BOT (and BOTT)

Scalability & flexibility Limited flexibility. Scaling up requires recruitment and training. Scaling down creates redundancy costs and unutilised capacity.

Risk profile Organisation bears all operational risks: recruitment, retention, compliance, facilities, business continuity, geopolitical. No supplier dependency risk.

Governance & decisionmaking

Advantages

Organisation exercises direct management authority over operations, personnel and processes. Changes are implemented through internal processes without external approvals. Close integration between the captive centre and retained organisational functions.

• Complete control over operations, data and culture

• Potential for lower unit costs at scale

• No supplier dependency

• Tailored processes and systems

• Close integration with organisation

Disadvantages

• High upfront capital investment

• Long implementation timeline

• Organisation bears full financial and operational risk

• Limited scalability and flexibility

• Must build innovation capabilities

• Fixed cost structure creates capacity risk

High flexibility. Third-party provider can redeploy resources across client base. Contractual mechanisms (AVC/RVC) manage volume changes. May have minimum commitments.

Transfers operational risks to third-party service provider. Creates supplier dependency risk (financial stability, performance, relationship, monopoly effects, and exit issues). Organisation retains some geopolitical risk.

Governance through contractual mechanisms. Changes require formal change management, may attract additional charges. Less integration with retained functions.

High flexibility during operating phase (similar to BPO). Flexibility diminishes post-transfer when organisation assumes capacity management.

Supplier dependency risk during operating phase. Operational risks transfer to organisation post-transfer. Transfer itself creates transition risk requiring careful management.

Provider governance during operating phase. Progressive organisation involvement pre-transfer. Full management responsibility post-transfer.

• Minimal capital investment and financial risk

• Rapid implementation

• Variable cost structure

• High scalability and flexibility

• Access to provider expertise and innovation

• Operational risk transfer

• Loss of operational control

• Supplier dependency risk

• Provider margin in pricing

• Potential lock-in effects

• Generic rather than tailored innovations

• Contractual complexity for changes

• Lower initial capital than pure captive

• Faster implementation than pure captive

• Provider expertise during critical build phase

• Flexibility during operate phase

• Eventual captive ownership and control

• More complex than pure captive or BPO

• Supplier dependency during operate phase

• Transfer creates transition risk

• Must build post-transfer capabilities

• Higher cost than BPO during operate phase

• Loses flexibility post-transfer

Optimal for

• Large-scale operations (200-300+ employees/ FTEs)

• Organisations requiring tight control

• Those with capital and risk appetite

• Longer strategic time horizons

• Existing offshore management capability

• Smaller to medium operations

• Rapid implementation requirements

• Limited capital availability

• Preference for variable costs

• Organisations comfortable with supplier relationships

• Volatile volume environments

• Organisations wanting eventual captive ownership

• Those lacking immediate capability to build independently

• Medium to longer time horizons

• Desire to learn before assuming full control

• Willingness to manage transition complexity

4 AI, captives and BPO

As noted in the introduction, both external BPO and captives face the same fundamental challenges: inflation and wages in Eastern Europe are rising, whilst investments in AI-driven automation are massive and a suitable outcome difficult to predict and achieve. AI is fundamentally transforming the BPO sector, creating significant opportunities and substantial risks for all parties. The question is: who should bear the risk –customers or suppliers?

4.1 The automation dividend

AI is reshaping operations with widely varying impacts. The BPO market reached over EUR 250 billion in 2024,1 with customer support alone representing nearly EUR 100 billion,2 making it the largest subsegment and prime target for AI disruption. Front office functions, such as customer service and help desk, face potential head-count reductions, some companies experiencing up to 40 per cent,3 for routine enquiries, as AI agents provide round-the-clock support across all channels, though complex cases still require human judgement. The shift is toward fewer junior staff and more experienced problem-solvers.

Back-office processes face more dramatic change. AI technologies directly impact the core BPO processes typically outsourced, as stated above, and enterprise workflows involving messy, unstructured data from disparate systems – mundane work previously handled by operations employees, robotic process automation solutions, or BPO outsourcing – are now being automated at scale.

4.2 The price of progress

For a medium-scale operation (200-300 full-time equivalent (“FTE”) ), total AI investment over three-five years reaches EUR 5-12 million. Larger operations face EUR 20-50 million or more.4 Returns are uncertain: AI capabilities are evolving rapidly, technologies that appear cutting-edge today may become obsolete within two-three years, processes prove more complex than anticipated, and actual savings may fall significantly short of projections. At the same time a very high percentage of AI projects fail to deliver to expectations and similarly a high percentage of projects are abandoned during implementation.5

4.3 The BPO dilemma

The traditional BPO model has been FTE-based, where savings are achieved through labour arbitrage, with providers committing to year-on-year efficiency gains meaning an increasingly smaller number of FTEs process the same transactional volume over time. AI dramatically accelerates this trajectory – but threatens the FTE-based pricing model underpinning BPO economics.

A fundamental business model mismatch exists between building AI-native products and running a BPO. In reality, most BPOs charge on an underlying time-and-materials billing model, charging clients an intransparent markup on labour: their business model depends on employing people and selling the output of that labour. Overhauling that model to become product-first and AI-native would dramatically compress margins, eliminate current cash cows and distort company culture.

Leading BPOs are attempting transformation, shifting from traditional hourly billing to outcome-based

1 Grand View Research (2024), Business process outsourcing market (2026 – 2033) - size, share & trends analysis report: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/business-process-outsourcing-bpo-market

2 Global Growth Insights (2025), Customer Service BPO Market Size, Share, Growth, and Industry Analysis: https://www.globalgrowthinsights. com/market-reports/customer-service-bpo-market-118244?utm_source=chatgpt.com

3 Reuters (2025), Meet the AI chatbots replacing India’s call-center worker: https://www.reuters.com/world/india/meet-ai-chatbots-replacing-indias-call-center-workers-2025-10-15/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

4 Gartner (2025), Gartner Says Worldwide AI Spending Will Total $1.5 Trillion in 2025: https://www.gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2025-09-17-gartner-says-worldwide-ai-spending-will-total-1-point-5-trillion-in-2025?utm_source=chatgpt.com & Stanford University Human-Centered AI (2025), AI Index Report 2025: Chapter 4 (Economy): https://hai.stanford.edu/assets/files/hai_ai-index-report-2025_ chapter4_final.pdf & Wavestone (2025), Global AI Survey 2025: https://www.wavestone.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/wavestone-global-ai-survey-2025.pdf

5 Gartner (2024), Gartner Predicts 30% of Generative AI Projects Will Be Abandoned After Proof of Concept By End of 2025, https://www. gartner.com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2024-07-29-gartner-predicts-30-percent-of-generative-ai-projects-will-be-abandoned-after-proof-of-concept-by-end-of-2025 & Fortune (2025): MIT report: 95% of generative AI pilots at companies are failing: https://fortune. com/2025/08/18/mit-report-95-percent-generative-ai-pilots-at-companies-failing-cfo/

models where clients pay for results rather than time. This business model could align incentives – but only if providers can navigate the transition without destroying their existing business – or put more bluntly if providers are willing to disrupt their existing business. Their willingness to do so will depend on their societal commitments (and corporate values) and the size of investment in real property (the delivery centres). Obviously, those unwilling to sacrifice investments and short term margin will in accordance with traditional disruption theories just die!

4.4 Who should bear the risk of AI implementations in BPO processes?

The question is not whether AI will transform BPO – it will – but who bears the investment and risk, and who captures the value. With 95 per cent of AI investments achieving zero return, strategic clarity and partnership selection matter far more than technology choice alone.6

External partnerships achieve 66 per cent deployment success compared with just 33 per cent for internally developed tools.7 Strategic partnerships with AI vendors dramatically outperform internal builds. One global major service provider has assessed that 80 per cent of AI projects currently fail to deliver to expectations and 50 per cent are scraped before completion.8 It would in our opinion be wrong to assume that AI has come out of the early adopter phase and become a mature product easily implemented. To the contrary, service providers’ major advantage is that they can experiment across multiple clients, learning from failures and refining approaches without suffering total loss from failed bets.

The main advantage of outsourcing and letting the service providers transform business processes through use of AI is the speed of implementation and thus the speed to get to savings and secondly transferring the implementation and business risk to the service provider. This advantage is achieved through warranted savings isolated from the success of AI driven transformation and requires that the “lock-in trap” is resolved.

4.5

The lock-in trap

AI vendor lock-in occurs when organisations become so reliant on a single AI or service provider that detaching becomes technically, financially or legally prohibitive. Many AI tools are deeply integrated with proprietary APIs, services or storage formats. What begins as a quick deployment decision evolves into a strategic bottleneck when models cannot be exported or infrastructure design conceals critical dependencies.

In 2025, the most significant hidden expense in the contact centre industry is not hardware, software or compliance – it is vendor lock-in.9

When evaluating AI technology components delivered by a BPO service providers, organisations must first and foremost focus on the transferability at the end of the term. If the contract with the then incumbent is not prolonged can the AI based/enhanced solution and business processed be continued inhouse or with a replacement provider? Will licensing and transfer of the solution be possible? Which data, training data, design documentation, algorithms etc. will be required to transfer? Alternatively, how easily can a replacement solution be built, which data and which documentation will be necessary?

Such exit scenarios design is relevant to cater for business continuity planning and to secure an advantageous end game without lock-in. This issue of vendor lock-in is certainly not new and in the past commercial practices and operational planning have been able to provide feasible escape options from the lock-in trap. AI based BPO services provide a new challenge and contract practices are in the developing stages.

6 MIT NANDA (2025), The GenAI Divide STATE OF AI IN BUSINESS 2025, https://mlq.ai/media/quarterly_decks/v0.1_State_of_AI_in_Business_2025_Report.pdf

7 MIT NANDA (2025), The GenAI Divide STATE OF AI IN BUSINESS 2025, https://mlq.ai/media/quarterly_decks/v0.1_State_of_AI_in_Business_2025_Report.pdf

8 McKinsey & Company (2025), The state of AI: How organizations are rewiring to capture value: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai-how-organizations-are-rewiring-to-capture-value & Gartner (2024), Gartner Survey Finds Generative AI Is Now the Most Frequently Deployed AI Solution in Organizations, https://www.gartner. com/en/newsroom/press-releases/2024-05-07-gartner-survey-finds-generative-ai-is-now-the-most-frequently-deployed-ai-solution-in-organizations?utm_source=chatgpt.com

9 Boston Consulting Group (2025), Managing the Evolving Dynamics of Digital Platform Lock-In: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2025/managing-dynamics-digital-platform-lock-in

5 Key commercial issues

5.1

Introduction

A limited number of key commercial aspects consume most of the time spent negotiating a BPO deal. These are traditional topics seen in all outsourcing arrangements — but each has a particular BPO dimension.

5.2

Term

All but the simplest payroll outsourcings require significant preparation and transition time. To achieve an acceptable period of stable operations before commencing reprocurement and any potential transition to another provider, a contract duration of four years is often viewed as the ideal term.

This term also allows transaction and transition costs to be written off over a reasonable period. In most deals the customer has the right to extend the term for up to 24 months.

While contract durations of less than four years have a disproportionate and negative effect on prices, we are not seeing longer-term contracts deliver significant additional discounts, and therefore benefits, to the customer.

5.3

Transition costs

In the classic BPO deal, a “lift and drop” approach is taken. This means a process or sub-process will, at least initially, be performed by the service provider in the same manner and using the same systems the customer has previously applied. Before the service provider can commence actual delivery of the services, substantial investment in building manuals and training personnel is required. Often the provider has key managers trained on site with the customer as part of a “train the trainer” or “shadowing programme”.

This investment will not be eliminated entirely, but in many deals, we have seen providers have offered to absorb transition costs. Our advice is to be transparent on all cost elements and to reflect actual transition costs in the pricing schedule rather than bundling transition with prices for ongoing services. This does not mean transition costs must be paid upfront — the payment profile is a matter of financing and financial engineering, and we see clients agreeing to different profiles depending on their needs.

5.4 Pricing models and pricing

The traditional pricing model for BPO services is a full-time equivalent (“FTE”) based model where a number of FTEs are allocated to service the customer — and the customer pays on the basis of forecast and consumed FTEs. Most often, the number of FTEs applied initially equals the number of FTEs the customer used before transition; the savings achieved by the customer are simply the mechanics of labour arbitrage.

If the number of managed transactions increases or decreases under this model, the parties will agree through a change management discussion how many FTEs should be added or deducted from the account. This is a difficult and opaque process.

An alternative model uses a fixed price for a given process. This model has the same change management-related problem as the FTE-based model and is generally used only for simple BPO transactions with limited or no expectation of changes in transaction volume.

A transaction (or unit) based model is more complex but generally the most flexible. Under this model, a small fixed base fee is combined with consumption-based pricing based on the number of transactions completed — for example, the number of invoices processed. Under this model, year-on-year efficiency improvements are agreed and reflected in decreasing unit prices.

In most modern BPO deals savings are warranted by the service provider but of course dependent on a given volume of transactions. The upper limit of potential of AI driven efficiency gains has yet to be determined and we expect to see warranted savings far exceeding past best practices both when relying solely on AI and when combining with labour arbitrage.

5.5 Eastern Europe or India

Wage trends across major BPO destinations since 2000 show a stark divergence. Eastern European wages have surged 150-200 per cent, fundamentally reshaping the region’s cost structure.10 Indian wages have remained flat, preserving the differential that underpins offshore economics.11

The Baltics have seen the sharpest growth. Lithuanian wages rose 177 per cent since 2000,12 Latvian wages climbed 192 per cent,13 —transforming these once low-cost destinations.

Poland has followed a similar, although slightly more moderate, trajectory, with wages approaching USD 45,000 (EUR 38,700).14 The Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia show more modest growth, converging around USD 35,000-39,000 (EUR 30,100-33,540) – marginally better value than Baltic and Polish markets.15

India’s trajectory remains flat below USD 15,000 (EUR 12,900).16 Whilst Eastern European wages surged 150-200 per cent since 2000, Indian wages barely moved in purchasing power parity terms, maintaining the cost differential driving offshore demand.

Eastern European wage convergence with western levels will continue, eroding near-shore cost advantages. India’s stable positioning preserves the traditional offshore value proposition—provided organisations can manage the operational complexities of distant delivery.

Wage development by country (2000-2024)

The choice between nearshore Eastern Europe and offshore Asia involves trade-offs beyond cost calculations.

5.6 Nearshore

Geographical and temporal proximity: Eastern Europe operates in time zones identical to or within two hours of Western Europe, enabling real-time collaboration. Proximity cuts travel time and costs, facilitating face-to-face engagement – particularly valuable during transitions and operational challenges.17

10 OECD (2026), Average Annual Wages: www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/average-annual-wages.html & OECD Data Explorer • Average annual wages

11 World Bank Group, GDP per capita (current US$) - India, World Bank Open Data, 2025: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?locations=IN

12 OECD, Average annual wages, OECD Data, 2025: OECD Data Explorer • Average annual wages

13 OECD, Average annual wages, OECD Data, 2025: www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/average-annual-wages.html & OECD Data Explorer • Average annual wages

14 OECD, Average annual wages, OECD Data, 2025: OECD Data Explorer • Average annual wages

15 OECD, Average annual wages, OECD Data, 2025: OECD Data Explorer • Average annual wages

16 World Bank Group, GDP per capita (current US$) - India, World Bank Open Data, 2025: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?locations=IN

17 Toptal (2026), Software Developers from Eastern Europe in 2024: Which Country Best Suits Your Project: www.toptal.com/external-blogs/youteam/developers-in-eastern-europe-which-country-suits-your-project

Cultural and linguistic alignment: Geographic proximity typically means similar business practices. Business etiquette across North America, Western and Eastern Europe is largely uniform – standard working hours, strong English fluency, established quality frameworks.18 Poland ranks 15th globally for English proficiency, Romania 11th, the Czech Republic 23rd, according to the EF English Proficiency Index.19 This linguistic capability particularly benefits Nordic companies requiring multilingual support.

Regulatory harmonisation: Nearshore destinations often have legal frameworks aligned with client home countries. European Union membership facilitates business cooperation through favourable regulations and simplified cross-border hiring, reducing compliance complexity with data protection, intellectual property and contractual agreements versus offshore arrangements.20

Higher cost structure: Nearshore labour costs exceed offshore rates. Whilst still affordable, savings prove materially less significant than offshore alternatives.21 Near-shore costs may in the midterm not differ substantially from onshoring. Eastern European wage inflation will prove difficult to offset through further optimisation.

Limited talent pool: Certain specialised skills prove less readily available nearshore than offshore. The specialised labour pool commands higher wages as nearshore locations increasingly resemble onshore markets. Eastern Europe offers substantial technology talent, but the market remains smaller than Asia –making specialists in advanced technologies harder to find.

Market volatility: Nearshore nations experience economic fluctuations affecting availability and costs, despite greater stability than distant offshore locations. High turnover in Eastern European based delivery centres, driven by competitive markets, disrupts workflow and extends lead times. Regional geopolitical instability adds further uncertainty.22

5.7 Offshore

Cost optimisation: This sustained advantage explains why offshore BPO providers establish the vast majority of delivery capacity in Asian markets, where economics remain compelling despite operational trade-offs. Offshoring to lower-cost jurisdictions enables substantial savings for reinvestment in strategic priorities. Cost reductions of 70-90 per cent prove achievable, reflecting significant wage differentials between developed and developing economies.23

Round-the-clock operations: Time zone variations enable follow-the-sun operational strategies, particularly benefiting businesses requiring 24/7 availability. Teams across time zones facilitate continuous operations, enhancing output and expediting project delivery.

Access to vast talent pools: Offshoring taps global talent, harnessing specialised skills potentially unavailable domestically. It opens doors to global expertise, stimulating innovation and providing competitive advantage. The sheer scale of available resources in markets such as India and the Philippines provides unmatched capacity for large-scale operations.24

Communication and cultural barriers: Time zones, language and cultural differences create communication difficulties compromising work quality. Language barriers cause delays and misunderstandings, whilst cultural differences influence communication styles and business practices, potentially creating conflicts.

18 Dreamix (2025), Software Development in Eastern Europe: 2025 Overview and Current State: https://dreamix.eu/insights/software-development-in-eastern-europe-in-2025/

19 EF (Education First) (2025), EF English Proficiency Index 2025: https://www.ef.com/wwen/epi/

20 Netrom Software (2025), The guide to nearshoring in Eastern Europe: https://www.netromsoftware.com/insights/nearshoring-in-eastern-europe/

21 COPC Inc., What are the pros & cons of going offshore vs. nearshore?: https://www.copc.com/clearly-cx/what-are-the-pros-cons-of-going-offshore-vs-nearshore/

22 COPC Inc., What are the pros & cons of going offshore vs. nearshore?: https://www.copc.com/clearly-cx/what-are-the-pros-cons-of-going-offshore-vs-nearshore/

23 Netguru (2025), Offshore Outsourcing Pros and Cons: A Comprehensive Guide: https://www.netguru.com/blog/offshore-outsourcing-pros-and-cons

24 Netguru (2025), Offshore Outsourcing Pros and Cons: A Comprehensive Guide: https://www.netguru.com/blog/offshore-outsourcing-pros-and-cons

Although offshore teams may have proficient English, barriers persist-leading to miscommunication, misaligned expectations and project delays.

Quality control challenges: Offshore distance limits on-site presence, with travel budgets stretched to ensure corporate personnel visit locations frequently enough to understand floor operations. Travel for in-person meetings proves more time-consuming and expensive than nearshore alternatives. Practical difficulties maintaining regular face-to-face contact undermine relationship quality and operational effectiveness.25

Security and compliance risks: Personal data volumes transferred depend on BPO scope. Once personal data transfers outside the European Economic Area, additional data protection requirements trigger and parties must enter European Commission standard contractual clauses, or other legal transfer mechanisms.26 Data shared with offshore partners may face security vulnerabilities due to differing security standards. Offshore outsourcing raises questions about data security and compliance with local and international laws. When business processes move to different countries, concerns about maintaining confidentiality of proprietary information make robust legal agreements and security measures essential.

Advantages

• Time zone alignment

• Real-time collaboration possible

• Reduced travel time and costs

• Cultural and business practice similarity

• Strong English proficiency

• EU regulatory harmonisation and shared legal frameworks

• Simplified data protection compliance

Disadvantages

• Higher labour costs than offshore

• Rapid wage inflation (difficult to off-set)

5.8 Strategic implications

• Cost savings of 70-90 per cent

• Significant labour cost arbitrage

• 24/7-follow-the-sun operations

• Unmatched capacity for large-scale operations

• Access to specialised skills

• Substantial time zone differences

• Communication delays and difficulties

• Cultural differences in business practices

• Complex data protection requirements

• Language barriers

Decision-making requires evaluating which processes suit relocation based on costs, workforce availability, political stability, infrastructure and legal environment.

For organisations prioritising collaboration, quality and regulatory alignment, near-shoring to Eastern Europe offers access to substantial developer talent and thousands of software houses, enabling western companies to achieve significant annual savings per employee through lower development rates whilst maintaining quality and cultural compatibility. Rising wages and geopolitical instability raise long term financial viability questions.

For cost-sensitive operations with well-defined processes and limited need for real-time interaction, offshore locations provide superior economics. As almost all services are delivered from Asia, the provider’s business case assumes no customer personnel will transfer through outsourcing, eliminating redundancy costs and accelerating implementation.

Viewed from a geopolitical stance, the analysis is not clearcut. While the proximity to and cultural alignment with Eastern Europe undisputedly in the past has led to Eastern Europa being viewed more favourably from a security risk perspective, that analysis is now more clouded. Events under the recent Trump presidency is pushing Europe towards other partners in Asia, India being an important potential trade partner. Similarly, geopolitical threats in Eastern Europe draw parallels to the pre-1990 cold war period where investments in Eastern Europe for obvious reasons were off the map. Control Risk’s – the global risk advisory firm – 2026 risk map places Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, France and Italy, and India in the same risk bracket.27

25 Piton Global (2025), The Economics of Offshore vs. Nearshore: A Decision Framework for BPO Buyers: https://www.piton-global.com/blog/the-economics-of-offshore-vs-nearshore-a-decision-framework-for-bpo-buyers/

26 European Data Protection Board, International data transfers: https://www.edpb.europa.eu/sme-data-protection-guide/international-data-transfers_en

27 See Control Risks | Global Risk Consultancy (www.controlrisks.com)

5.9 Minimum commitments

Providers will request minimum commitments, but in our view the current market standard is that no direct minimum commitment should be given. Rather, a provider’s revenue stream is secured through either a fixed base fee as part of a consumption-based pricing model, a forecast mechanism, or the notice period applicable to termination for convenience.

5.10 Currency risks and COLA adjustments

Generally, payment in a western currency is agreed (euros or dollars). As the provider has most of its costs in a local Asian currency, the provider faces significant currency risk. Over the past few years, Indian providers have become noticeably more sophisticated in their approach to hedging and managing currency risk. This has translated into a high degree of risk appetite and willingness to assume currency risk for a defined number of years. Our experience is that allocating currency risk in the initial contract period to the provider is worthwhile. However, after this period, the risk premium added to prices erodes this advantage.

5.11 Transfer of employees and related costs

As almost all services are provided from Asia, the provider’s business case is (with very few exceptions) built on the assumption that none of the customer’s personnel will be taken over as a result of the outsourcing (based on the Acquired Rights Directive (ARD, Directive 2001/23/EC)). Consequently, providers require that the customer bear all costs associated with redundancies resulting from the outsourcing.

5.12 Benchmarking

Benchmarking provisions have now become common practice and benchmarking is supported by a host of expert benchmarkers.

6 Key practical challenges when contracting

6.1

Preparing service requirements and specifications

In each of the BPO processes we have seen, the overriding problem has been crafting adequate process and workflow descriptions, including descriptions of the handovers between different sub-processes, or between the parts of a process conducted by the customer and the parts conducted by the service provider.

For example, if the service provider is providing help desk services to the customer’s customers, the service provider will need to understand and be able to:

a. use decision trees and execute workflows;

b. apply the customer’s policies, including main policies and exceptions; and

c. access data in the customer’s systems and understand how to use such data.

BPO requirements cannot be stated as simple output requirements such as “issue all invoices before the 28th day of each month” or “complete a help desk call with final resolution within five minutes in 98 per cent of all calls”.

Therefore, process and sub-process descriptions must be sufficiently detailed that from a qualitative viewpoint a particular process can be executed by the service provider with the expected output that meets all relevant handover criteria and service levels.

In most organisations business processes are described in general manuals — but most often descriptions that set out sufficient detail for an external service provider to conduct the same processes are not available. The interpretation of policies, accepted practices, or large parts of processes, is often ingrained in the customer’s organisation through training or through an experienced understanding of working alongside colleagues. However, this information is in most instances not documented owing to its intangibility. The challenge of preparing a BPO arrangement is to capture this undocumented part of the customer’s processes in writing, set out in manuals, instructions and training material, to:

a. set contractual obligations;

b. secure compliance and a high quality of services; and

c. establish a baseline that will enable the customer to change processes during the term of the contract without incurring extra charges by replacing part processes and to hopefully avoid discussions whether the amended process is an expansion of such duties.

Another traditional part of this discussion is the issue of documentation for internal service level compliance. Generally, customers will not have applied the same service levels internally, if any, with which the service provider is being asked to comply. Consequently, service providers are reluctant to accept service levels and associated service credits unless granted sufficient time to improve and fine-tune the services after service commencement.

Generally, customers expect that BPO processes are standardised and that service providers (or bidders in a tender) will possess detailed process descriptions with associated service levels that can slot into the deal documentation. Unfortunately, that is not the case and from a documentation and service requirement perspective each deal is approached as bespoke.

The foregoing represents a practical problem not easily resolved. If the customer initiates a procurement process without reliable documentation of the services to be outsourced, the outcome will be:

a. unrealistic pricing (either too high or too low) which will be revised throughout the bidding process;

b. substantial delays of the process; or

c. a weak contract coupled with low budgetary certainty or protection as the service provider will exploit any insufficiently described element of necessary services to require additional charges.

The solution is not as simple as spending sufficient time painstakingly detailing each aspect of processes before the tender process begins. The reality is that documenting services is to some extent best done together with the chosen service provider as an integrated part of the transition process and the training of service provider personnel. The disadvantage is that this work cannot be initiated before a service provider has been chosen. Therefore, a balance must be struck between achieving a sufficient level of documentation before down-selection to one bidder and the level of detail to be developed as a joint effort between the customer and the service provider at a later date.

7 Key legal issues

7.1 Compliance with laws

When conducting a BPO outsourcing, many customers believe the service provider will ensure the customer remains in compliance with all applicable laws. In other words, that the service provider will ensure all processes and documentation from the time of the outsourcing will continuously be compliant. At times this expectation stems from those FTEs that previously secured internal compliance within the customer’s organisation and have been made redundant as a consequence of the outsourcing.

The service provider’s perspective differs. A service provider will rarely employ lawyers with local law knowledge and will not wish to monitor changes in laws and assume responsibility for the customer’s compliance unless that kind of compliance management is the main subject of the BPO.

Moreover, as a customer will not be able to shed its liability for legal compliance and will have to maintain a strong focus on legal compliance, we (almost without exception) recommend that:

a. the risk of the customer’s legal compliance; and

b. the risk of future changes to laws applicable to the customer, should remain with the customer. From a cost efficiency perspective, this is also the most optimal solution as a customer can in most cases achieve compliance at lower cost than the service provider.

In accordance with generally accepted standards for other kinds of outsourcing, BPO providers will undertake to comply with those legal requirements that at any given time apply to the business of service providers.

Additionally, most service providers will undertake to comply with those local legal requirements from the service provider’s local jurisdiction that are triggered by the BPO (for example, local Indian data protection requirements that may apply to data being accessed from or stored in India).

The responsibility for compliance can be expressed as follows: Responsibility for compliance

Compliance with law relevant to the customer where it operates its business, including data protection

Duty to follow instructions and requirements stated by the customer in order for the customer to remain compliant

Compliance with laws applicable to the service provider’s general business

Compliance with local laws related to the delivery locations of the service provider relevant to the customer’s business which are triggered by the outsourcing

7.2 Data Protection

Financial responsibility for the consequences of changes in laws

While the data protection implications associated with the provision of BPO services depend on the scope of the BPO services being outsourced, most BPO services will comprise some aspect of processing of personal data.

The key data protection challenges associated with BPO outsourcing include:

a. Establishing and maintaining a compliant data processing chain

b. Ensuring compliance of data transfers to third countries

c. Establishing a risk assessment and compliance framework for achieving AI-based efficiency gains

As a data controller, a customer entering into a BPO outsourcing arrangement is required to ensure the compliance of the service provider’s processing of personal data as a data processor and the compliance of the entire processing chain comprising any sub-processors engaged by the service provider. The European Data Protection Board has emphasised this obligation in its Opinion 22/2024, clarifying the level of detail by which data controllers are required to assess the compliance and security of the BPO supply chain.

The transfer of personal data to recipients in third countries (ie in countries outside the EU/EEA area) continues to pose a challenge in BPO outsourcing that leverage offshore service providers. The lessons derived from the Schrems II decision still require that a level of data protection equivalent to the protection provided under the GDPR has to be established when transferring personal data to service providers in third countries. As the legislative data protection offered in the countries where key offshore providers are located (such as India) is generally not equivalent to the level provided under the GDPR, customers engaging with offshore service providers have to carefully assess the supplementary technical and organisational measures available to protect the transferred personal data.

While compliance with the data transfer restrictions entails an ongoing administrative task for the customer, the maturity of the leading offshore providers has increased significantly in recent years and most service providers offer comprehensive measures involving pseudonymisation, encryption and monitoring to protect personal data transferred to or accessed by the service provider from third countries.

With the introduction of the AI Act and its application alongside existing data protection legislation, the use of AI in BPO services to achieve efficiency gains presents compliance challenges. Assessing potential AI-specific risks such as potential biases, inadequately trained AI models and automated decision making is a prerequisite to deploying AI tools.

The solution

Introducing compliance requirements that facilitate the customer’s compliance process (end to end) is a prerequisite. This involves connecting the customer’s compliance processes for data processor assessment and audits with the contractual obligations of the service provider to provide compliance documentation and risk assessments (TIA, DPIA, FRIA etc.) in a format that easily integrates with the customer’s compliance management systems.

With respect to the use of AI, it is particularly important for customers to impose contractual obligations for service providers to provide transparency regarding the service provider’s use of AI tools and to establish a compliant framework for the service provider’s introduction of new AI tools and models.

8 Contract issues:

BPO is “just” outsourcing so get the outsourcing fundamentals right

BPO is outsourcing at its core and most will be familiar with the basics. However, as a useful primer to a best practice approach to BPO, this section sets out those issues and solutions relating to the fundamental aspects of BPO that should be correct from the outset.

8.1 In-scope and out-of-scope services

The issue

Prices relating to the BPO arrangement are generally based on the in-scope services – the services the service provider will provide to the customer on commencement of the agreement. As mentioned above, the in-scope services should be specified carefully in the agreement, and both parties should be aligned on what services the service provider will and will not provide from the outset.

Service providers will go to lengths to argue that an additional service is a “new service” and therefore chargeable.

The solution

To keep the customer protected from unexpected future price spikes, the BPO agreement should include a high (but not impossible) threshold for what constitutes a “New Service”. Essentially, this means an additional service is included within the original price unless the service provider can prove the additional service meets the requirements of a “New Service”.

The definition of what constitutes a “New Service” should include the following three elements:

a. Services that are materially different from the existing services;

b. Services that require significantly different levels of cost or effort than those used by the service provider to provide the existing services; and

c. Services for which there is no current resource baseline or related resource unit, except for resource units related to services performed on the basis of consumed time.

Further, a non-exhaustive list of what a “New Service” is not will usually be included.

The combination of the above two mechanisms means the threshold for a new chargeable service is high but not impossible to achieve.

8.2 Flexibility

The issue

By their very nature, outsourcing arrangements are often inflexible. Generally, such arrangements incorporate a fixed term, whereby termination for convenience is permitted only against payment, and for a predefined area of scope. Predefined geographic scope and service recipient lists, together with rigid pricing models (which are often related to a predefined services scope), add to the inflexibility of the arrangement.

Such inflexibility significantly impacts the organic growth of the customer’s business. Business requires flexibility to support growth often seen (for example) through the creation of new products and conducting corporate acquisitions and divestments. Equally, flexibility is required for downsizing businesses in the case of economic downturns seen over the past decade.

There are three main customer requirements that might compliment the above:

a. more volume (in the instance of growth);

b. less volume (in the case of downsizing); or

c. new needs (applicable in both instances).

The following illustration provides a useful overview of our proposed solution to each of these needs, which are assessed further below.

AVC rates

Ramp up ti me

Termination for convenie nce

RVC rates and bandwidth s

Ramp dow n time

Termination for convenie nce per s ervice element or whole new agreeme nt

New services

Princing pri nci ples

The solution

Adjusting the volume of services

Additional volume charges (AVCs) and reduced volume charges (RVCs) are potentially the best way to deal with additional or reduced volume fluctuations. Put simply, any increased or decreased consumption relative to a service baseline is either chargeable by the service provider (AVC) or deductible by the customer (RVC).

The AVC and RVC rates should be agreed in advance, noted in the agreement’s price book, and calculated on the initial FTE baseline.

In addition, many BPO arrangements combine the above with a dead band mechanism whereby the AVC and RVC rate would be applied to the base charge only if the dead band was exceeded. This can be further illustrated using the diagram below.

Price adjustments would consequently be adjusted by using the following formula:

AVC / RVC Rate x volume units above or below baseline (i.e. actual consumption) = amount to adjust the base charge by

Flexibility in termination for convenience

Termination for convenience should cover only a need to reduce the services to a significant extent such that it would not make sense to use the RVC mechanism as set out above. From the service provider’s perspective, this is perhaps the greatest threat to its business as termination for convenience would have a direct impact on its profits. In response to such a threat, any service provider would seek to protect itself against lost income, rampdown costs, deferred profits and depreciated investments.

While service providers would generally accept termination for convenience by “Service Order” and by service area, our approach is that termination for convenience should take place at least at service area level, but preferably for any other independent element.

Termination fees should be fully transparent and subject to competition during the tender process (ie, service providers may be scored according to termination fees offered as part of the financial evaluation). Finally, the agreement should state a precise formula to account for depreciation of identified investments, if any.

No established global market practice exists relating to the calculation of termination fees. We see the following terms being combined to achieve a balance between the service provider’s and customer’s interests:

a. three-six month termination notice period;

b. payment of any undepreciated pre-agreed investments, such as transition costs; and

c. a termination fee based on a single digit percentage of remaining expected revenues over the term of the agreement.

Generally, customers should expect more favourable termination for convenience terms than those often set out in IT infrastructure outsourcing arrangements.

Flexibility in service recipients

In most instances, the list of service recipients is set out in a pre-agreed schedule and often the customer is granted a right to add more entities to this list. The service provider’s general concern with this approach is that it does not want the customer simply to resell its services — as this would amount to lost income.

Acquisitions and divestments

From the service provider’s perspective, increased volumes generally present little threat to their operations. However, the same cannot be said of decreased volumes owing to the knock-on effect of lost income the service provider will likely suffer. A corporate acquisition would likely result in more services, whereas a divestment might result in fewer.

Our approach is to evaluate carefully whether the flexibility built into the pricing model and termination for convenience terms are sufficient, or whether special terms and conditions applicable only to acquisitions and divestments need to be crafted.

d. disputes relating to whether a “Change” is payable, or in fact is a “New Service” and therefore payable.

The common consequence of the above is that the service provider will either refuse to remedy any problem quickly, or might refuse delivery of the service entirely unless the customer pays more money. In this latter instance, the customer is held to ransom at the mercy of the service provider — as if the customer refuses to pay it will usually face significant business losses. Conversely, if it does pay, such payments are often difficult to recover at a later date.

8.3 Termination services and exit assistance

The issue

All outsourcing arrangements will at some point come to an end — whether at the expiry of the term or before. At this point, the service provider will need to provide additional services to transition the services either back to the customer or to a replacement service provider. At this point, as the service provider is aware the relationship is ending, its incentive to provide a top-notch service is low. This imbalance must be addressed in the outsourcing agreement.

The solution

To address the above problem, an effective termination services schedule must be drafted. This provision must incentivise the service provider not only to continue to provide the services during this last period, but also ensure an orderly handover of the services either back to the customer or to a replacement service provider. It is therefore important that any termination services provision includes the following key elements:

a. The scope of the termination services includes all services relevant to the successful transfer of the services to the customer or a replacement service provider, with the burden resting on the service provider, such that all services are deemed to be included unless the service provider proves otherwise;

b. The cost for the termination services should either be agreed upfront upon signature of the outsourcing arrangement, or should be subject to quotation and approval at a later date;

c. The following should be included in the base charges and therefore not be separately payable in any event:

i. Compilation and delivery of due diligence materials;

ii. Continued performance of the services;

iii. Drafting and delivery and maintenance of the termination management plan;

iv. Compilation and delivery of data;

v. Drafting and delivery and maintenance of a fall-back plan; and

vi. Deletion, removal and decommissioning activities;

d. To the extent termination is caused by the service provider’s material default, the termination services should be provided by the service provider at no cost to the customer;

e. The service provider should continue to provide the services until the date the termination services are completed;

f. Should the transfer of the performance of the services or any part thereof not be possible or conducted as agreed, the service provider should be responsible for drafting an adequate fallback plan that contains all relevant information to ensure the services can be performed in the same manner as before the end date of the agreement;

g. Any transition plan agreed between the customer and any replacement service provider should designate how the current services will transfer to the replacement service provider. Therefore, on request by the customer, the service provider should update the termination management plan so that it supports and integrates with the transition plan held by the replacement service provider. It is integral that the milestones for delivery under the termination management plan match the transition plan; and

h. An option to retain consultancy services in the post-transfer period.