Table of Contents

Letter from the President of GATE Page iii

By Natasha Ramsay-Jordan

Letter from the Editor-in-Chief of GATEways to Teacher Education Page v By Forrest R. Parker III

Removing the Obstacles: Educator Perceptions and Practices of an Alternative Page 1 Education Model

By Joan Ferguson Whitehead, Gwen Scott Ruttencutter, and Nicole P. Gunn

Wait! You’re Both Teaching Us?!: Co-teaching in Higher Education Page 17

By Heather M. Huling, Kathleen Crawford, and Catherine Howerter

Friend or Foe: Pre-service Teachers' Perceptions of AI Page 40

By Rebecca Cooper, Tashana Howse, Samantha Mrstik, and Joye Cauthen

Towards Students’ Understanding of Doctoral Retention: A Chutes and Page 59 Ladders Approach

By Jennifer M Lovelace

Examining Elementary Preservice Teachers’ Perspectives of Equity-Based Page 93 Instruction in Mathematics

By Cliff Chestnutt and Andrea Crenshaw

Navigating Uncertainty: Using Relational Leadership to Guide Page 108 Teacher Preparation Faculty and Staff Through an Unknown Era

By Joseph R. Jones and Gayle Ramirez

Resource Section:

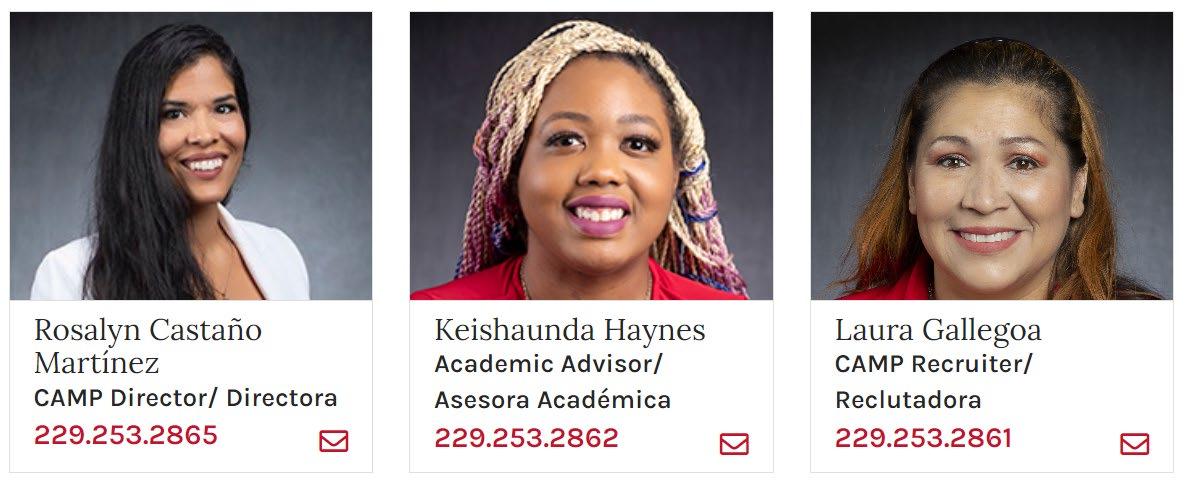

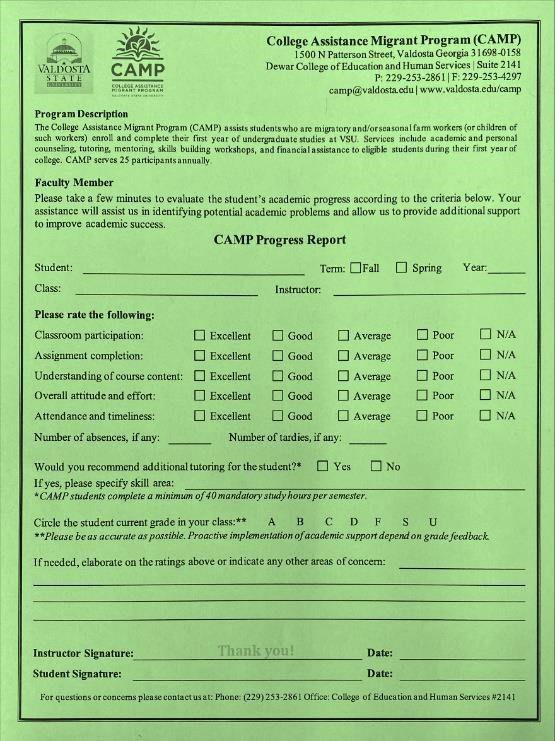

College Assistance Migrant Program Handbook Page 119

By Rosalyn Martinez and James Martinez

A Letter from the President of the Georgia Association of Teacher Educators (GATE)

Dear Gateways to Teacher Education readers and contributors,

Welcome to the Fall 2025 issue of the Gateways to Teacher Education journal, the official journal of the Georgia Association of Teacher Educators (GATE). As an affiliate of the National Association of Teacher Educators, the GATE organization works diligently to improve education in the state of Georgia, empower teachers, and enhance the teaching and learning experiences within educator preparation programs across the state. As GATE’s president, I am most grateful for your ongoing efforts to help us deliver timely, informative, and meaningful content to the GATE community, members, and readers. I am especially pleased that our readership and reach continue to grow, greater than ever, with this and other journal entries readily available online.

Like each year past, we are committed to sharing diverse perspectives on education, highlighting the breadth and scope of critical issues impacting education. From confronting how preservice teachers navigate AI to a focus on equity-based instruction, this current issue of GATEways includes works focused on student retention, school reform models to address graduation rates, and relational leadership as a guide for preparation programs. I hope each article encourages further discussions and collaborations across disciplines.

In addition to this and other research publications in the Gateways to Education journal, GATE’s social media pages, including Facebook, LinkedIn, and Instagram, continue to expand, and we hope this can provide additional platforms to share information and news of interest to our GATE community. I invite you to like, follow, and share educational news and content on each of our social media platforms.

Let me also take this opportunity to extend a heartwarming invitation to you and your colleagues to register and attend GATE’s upcoming 2026 Conference to be held on St. Simon’s Island in Sea Palms on February 19 and 20, 2026. The theme for this year’s conference is GATE Strong: Shaping the Future of Education Together. Whether you are new to GATE or a regular conference attendee, we would love for you to join us at our annual conference in Sea Palms and hear about the great work being done within the various Georgia institutions of higher education, and also engage in dialogue with K-12 educators. 2026 is a great year to hear about the wonderful work you are doing and engage in conversations about how we can all take our ambitions to the next level. Exciting!

Notably, GATE’s achievement could not have been possible without the continuous support, interest, and contributions of its members and community, the efforts of the editor, and the executive committee. On behalf of our entire team, we thank you for all you have done and continue to do for GATE. We hope that this journal, and its subsequent editions, can play some role in your scholarly journey and that you consider becoming part of GATEways' legacy by submitting your manuscript for publication.

Best,

Dr. Natasha Ramsay Jordan President, Georgia Association of Teacher Educators

(GATE)

Message from the Editor-in-Chief of the GATEways to Teacher Education Journal

Dear Readers,

It is a joy to greet you again as Editor-inChief of GATEways to Teacher Education, the peer-reviewed journal of the Georgia Association of Teacher Educators (GATE). Now entering my second year in this role, I remain deeply grateful for the trust of our community and inspired by the quality, relevance, and heart our authors and reviewers bring to the work of preparing excellent, equity-centered educators.

This issue continues our commitment to publishing scholarship that is both rigorous and useful in practice. You’ll find studies that illuminate persistent challenges, descriptive accounts of innovative coursework and field experiences, and reflective pieces that stretch our thinking about what teacher education can—and should—be. I hope you will read, cite, and share these articles with colleagues, candidates, and partners in your local schools.

Over the past year, we have focused on three priorities:

1. Clarity and Support for Authors. We’ve refined our author guidelines, added template resources, and strengthened developmental feedback for emerging scholars and practitioner-authors.

2. Launching an Editorial Board. We are establishing a diverse, service-oriented Editorial Board to guide journal strategy, uphold scholarly standards, and mentor authors and reviewers. Board members

will help shape special topics and support timely, transparent editorial processes. We invite nominations and self-nominations from across our P–20 community.

3. Timely, Transparent Processes. We have tightened editorial timelines and improved communication at each stage of review and revision.

Looking ahead, we welcome submissions that advance the conversation in teacher education empirical studies, program innovations, partnerships with P–12 schools, policy analyses, and practitioner scholarship grounded in evidence. We are especially interested in work that centers diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging; field-based learning; effective assessment of candidate competencies; technologyenhanced teaching and mentoring; and strategies that sustain the educator workforce.

If you are interested in serving as a reviewer—or proposing a themed section or special issue—please reach out. GATEways thrives because of educators who are willing to read generously, offer candid and caring critique, and champion scholarship that lifts both research and practice.

GATEWAYS

My sincere thanks to our authors for entrusting us with your work; to our reviewers for your faithful labor; to Vicki Pheil, the copy editor for the GATEways Journal; and to the leadership of GATE for steadfast support of this journal’s mission.

Thank you for being part of the GATEways community. I look forward to the scholarship and dialogue ahead.

Cheers,

Forrest R. Parker III, Ph.D. Editor-in-Chief, GATEways to Teacher Education

Removing the Obstacles: Educator Perceptions and Practices of an Alternative Education Model

Joan Ferguson Whitehead,1 Gwen Scott Ruttencutter,2 & Nicole P. Gunn 2

1 Independent Researcher

2 Valdosta State University

ABSTRACT

Although access to education in the United States has improved for students across race, class, ethnicity, and gender, not all demographic groups’ progress has kept pace with access (Mujic, 2015). In the past two decades, more high school dropouts have been enrolled in public schools serving predominantly African American and Hispanic students of low socioeconomic status (Mujic, 2015). This portraiture study involved interviewing and observing six participants in an established nontraditional educational setting. This study examined the model of restorative justice practices at The Academy, a nontraditional high school in an urban southeastern RESA district of Georgia, through the voices of six educators. National, state, and local education systems may benefit from these findings by identifying mechanisms and practices that can help support graduation rates across the country. School districts and individual schools may also benefit from these findings and adopt the strategies employed to support the graduation rates for the students they serve.

Removing the Obstacles: Educator Perceptions and Practices of an Alternative Education Model

Across the United States, schools have expanded access to education, yet deep inequities remain. Nowhere are these inequities more visible than in urban districts serving Black and Brown students from low-income families. Although educational access has improved, opportunity has not been evenly distributed. Persistent gaps in graduation rates, college readiness, and life outcomes are not randomly occurring; rather, these outcomes are linked to systemic racism, poverty, and exclusionary practices that continue to disenfranchise students of color (LadsonBillings & Tate, 1995; Stevenson, 2019).

For teacher educators, these inequities are not abstract. They shape the daily realities of preservice and in-service teachers who are called to work in diverse schools, often without the preparation of frameworks to dismantle the structures that harm students. The problem is not simply academic underachievement, but the broader cycle of educational disenfranchisement leading toward mass incarceration, commonly referred to as the school-toprison pipeline (Balfanz, 2007; USDOE OCR, 2014). To disrupt this cycle, teacher professional development programs must highlight models of liberatory education approaches that affirm student identities, build authentic relationships, and resist

deficit narratives (Freire, 1970; hooks, 1994; Ladson-Billings, 1995).

This study examined the model of restorative justice practices at The Academy, a nontraditional high school in an urban southeastern RESA district of Georgia, through the voices of six educators. Using portraiture methodology, the study highlights how these educators employ relational, culturally sustaining, restorative practices that challenge systemic inequities and offer pathways toward graduation. The findings speak not only to alternative schools but also to all teacher educators and practitioners seeking to cultivate liberatory spaces for historically marginalized youth.

To understand the importance of this model of restorative justice, this study drew on three interconnected frameworks: Critical Race Theory (CRT), Relational-Cultural Theory (RCT), and the school-to-prison pipeline. CRT offers a perspective for analyzing how race and racism remain woven into educational systems, often influencing which students receive support and which students face discipline (LadsonBillings & Tate, 1995). Through counterstorytelling and critique of so-called raceneutral policies, CRT helps expose how systems continue to marginalize students of color. RCT complements this by highlighting the transformative potential of relationships. Grounded in the idea that growth occurs through connection rather than isolation, RCT provides a framework for understanding how affirming, empathetic relationships can foster resilience, particularly for students who have been marginalized by traditional schooling (Comstock et al., 2008; Miller, 1976).

Finally, the school-to-prison pipeline frames the broader social consequences of exclusionary school practices. This

framework draws attention to the disproportionate use of suspension, expulsion, and law enforcement in schools serving Black and Brown youth, and how these practices intersect with race, poverty, and disability to funnel students out of education and into incarceration (Balfanz, 2007; USDOE OCR, 2014). Together, these frameworks guide this portraiture study that focused on the voices of six educators working within The Academy. Their stories provide insight into how relational practices, cultural awareness, and structural critique can coalesce to transform a school, creating not just a place of learning but also a space of possibility.

Purpose

This study examined how educators at The Academy, a nontraditional high school in an urban southeastern RESA district, perceived and implemented an alternative education model aimed at supporting graduation rates for African American and Hispanic students from low-income backgrounds. Approved by the State Department of Education and aligned with the Georgia Performance Standards (GaDOE, 2020), The Academy implemented an alternative curriculum model that incorporates restorative practices and flexible pathways, allowing students to work toward graduation requirements at their own pace. Student progress was assessed through the Georgia Milestones End-of-Course exams. Although a four- year graduation plan was encouraged, individualized pathways allowed for additional time and faculty support when necessary.

Research Questions

1. What are the life and career experiences of educators who implemented a nontraditional high school reform model

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

to improve graduation rates at an identified urban school district serving predominantly African American and Hispanic students from low-income families?

2. What strategies did educators use to implement a nontraditional high school reform model to improve graduation rates in this context?

3. What were the barriers, if any, educators encountered while implementing this model?

Theoretical Frameworks

To explore how an alternative curriculum model might break these patterns, we used interconnected frameworks: Critical Race Theory (CRT), Relational-Cultural Theory (RCT), and the larger context of the school-to-prison pipeline.

Critical Race Theory (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995) serves as a powerful lens for examining how race and racism are not relics of the past but are deeply embedded in the fabric of educational systems. CRT challenges scholars and practitioners to interrogate race-neutral policies and practices that often sustain systemic inequities, and it centers counter-storytelling as a tool for disrupting dominant narratives. This framework helped investigate how the experiences of students of color, and the educators who serve them, are shaped by structures that normalize White cultural values while marginalizing other cultures’ values.

Relational-Cultural Theory (Comstock et al., 2008; Miller, 1976) offers a complementary lens, emphasizing the transformative power of relationships.

Although traditional models of development often celebrate autonomy and independence, RCT recognizes that growth occurs in and through connection. This framework is particularly relevant in educational settings where students may arrive carrying the weight of trauma, marginalization, or mistrust. RCT affirms the importance of educators who build mutual, empathic, and growth-fostering relationships to counteract disconnection and alienation.

Ultimately, the school-to-prison pipeline offers a crucial context for understanding why alternative education is important. This term describes the systemic pattern in which students, particularly those who are Black, Brown, poor, or disabled, are pushed out of school through exclusionary discipline policies and into the juvenile or criminal justice system (Balfanz, 2007; USDOE OCR, 2014). These patterns are exacerbated by zero-tolerance policies and school policing practices that criminalize behavior rather than address underlying needs. In this study, the alternative curriculum model is considered not simply as a programmatic intervention, but as a potential site of resistance to these broader structural forces.

Literature Review

Understanding the landscape of nontraditional high school education for marginalized youth necessitates a thorough examination of the historical, cultural, and systemic factors that have shaped traditional schooling in the United States. Since Brown v. Board of Education (1954), education policy and practice have promised equity yet consistently failed to deliver just outcomes for Black and Brown students. Although access to education has expanded, deeply ingrained disparities in performance, discipline, and opportunity persist. The literature suggested that these gaps are not

merely academic; they are structural, societal, and deeply personal, reflecting a system that was never designed with all students in mind.

Mass Incarceration and Educational Disenfranchisement

The backdrop of this study is a system in which exclusionary school practices mirror broader patterns of criminalization. Black and Brown students are disproportionately suspended, expelled, and referred to law enforcement, often for behaviors that draw minimal discipline for White peers (USDOE OCR, 2014). These patterns accelerate school disengagement and feed into the nation’s unprecedented incarceration rates (Stevenson, 2019). Nearly 70% of incarcerated youth suffer from mental illness, yet few receive adequate care (Goncalves et al., 2016).

For teacher educators, this reality underscores the urgency of preparing future teachers who can recognize the signs of trauma, resist punitive reflexes, and employ restorative practices. Teacher education must confront not only curriculum and instruction but also the carceral logics embedded in schooling that push students out rather than pull them in.

Historical and Structural Barriers

The inequities shaping today’s schools are not new. Since Brown v. Board of Education (1954), education policy has promised equity yet consistently failed to deliver just outcomes for Black and Brown students. Schools have too often privileged Eurocentric values and pathologized students of color (Roediger, 2005; Wells, 2018). African American boys have been misdiagnosed, misplaced, and misunderstood disproportionately suspended

and tracked into special education (Tatum, 2005).

For teacher preparation programs, these histories remind us that preservice teachers enter classrooms shaped by narratives that frame some students as deficient. Without explicit training in culturally sustaining pedagogy, educators risk perpetuating those same biases.

The Promise and Power of Critical Race Theory

Critical Race Theory offers one way to address these inequities by exposing how racism remains embedded in education. CRT centers counter-storytelling, highlighting the lived experiences of students and educators of color as valid sources of knowledge (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995). In teacher education, CRT challenges future teachers to interrogate race-neutral policies, recognize microaggressions (Pierce, 1970), and resist deficit-based thinking. By elevating counternarratives, CRT prepares educators to disrupt racialized structures in their own practice.

Relational-Cultural Theory and the Power of Connection

Relational-Cultural Theory (RCT) complements CRT by emphasizing the role of authentic relationships in human growth. Rather than valuing independence and autonomy above all, RCT asserts that development occurs through connection, empathy, and mutuality (Comstock et al., 2008; Miller, 1976). For many marginalized students, past experiences with schools have fostered mistrust and disconnection. RCT highlights the importance of teachers who can build trust, validate student identities, and foster resilience through connection. In teacher education, this means equipping

preservice teachers with relational competencies alongside content knowledge.

Toward Liberatory Education

Together, CRT and RCT point toward liberatory education, a pedagogy that resists oppression, affirms cultural identity, and restores dignity. Freire (1970) described liberation as education that empowers learners to read both the word and the world. Bell hooks called for an “engaged pedagogy” rooted in care and justice. Ladson-Billings (1995) argued that culturally relevant pedagogy prepares students to succeed academically while affirming cultural competence and consciousness.

For teacher educators, the call is to prepare teachers to deliver standards-based instruction and to create classrooms where marginalized students feel seen, valued and empowered. Alternative modules like The Academy provide real-world laboratories of liberatory practice, offering insights into how teachers can resist deficit narratives and reimagine education as a site of possibility.

Method

This qualitative study employed portraiture methodology (LawrenceLightfoot & Davis, 1997) to capture educator’s lived experiences and practices at The Academy, a nontraditional high school designed for students at risk of dropping out. Portraiture was selected because it blends empirical rigor with narrative sensibility, enabling the researcher to document both the struggle and strengths of educational practice. Portraiture, as described by Lawrence-Lightfoot and Davis (1997) is marked by five defining hallmarks. The first is the aesthetic whole, which requires the researcher to weave the account

with balance, rhythm and coherence so that the final narrative reads as artful and empirical. The second is goodness, a deliberate search for strengths and possibilities while acknowledging tensions and contradictions that give the story depth. A third hallmark is voice, where participants’ words are not reduced to fragments but presented in extended quotes and story-like vignettes that allow their perspective to resonate. The fourth is relationship, which purports that portraits are co-constructed; they emerge from trust, reciprocity, and the shared effort between researcher and participant. Finally, portraiture values emergent themes, encouraging meaning to surface through inductive analysis rather than through categories imposed by the researcher. Together, these hallmarks guide the portraitist in creating narratives that are authentic and deeply human.

In this study, these features guided the design and analysis. “Goodness” was shown in how educators described resilience and transformation, not just challenges. “Voice” was preserved through direct quotes and crafted vignettes. The “aesthetic whole” was achieved by weaving individual portraits with cross-case themes. Relationships of trust built during interviews shaped the candor of responses, and emergent themes were developed through multiple analytic cycles.

Setting

The study took place in a Title I school district in urban Georgia, where 100% of students qualify as low-income (Georgia Department of Education, 2020). The district enrolls approximately 23,000 students from Pre-K through 12th grade. Its demographics are 73% African American, 18% White, 5% Hispanic, 2% Asian/Pacific

GATEWAYS

Islander, and 2% multiracial. Historically, the district has faced persistent challenges, including graduation rates below the state average and college and career readiness rates among the lowest in Georgia.

The Academy, the site of this study, serves middle and high school students referred from six feeder schools. It offers a blended learning model that integrates faceto-face instruction, digital platforms, and peer collaboration. Students follow personalized learning plans tailored to their goals and needs. The school also uses the Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) framework to foster a safe, supportive climate that emphasizes prosocial behavior.

Staff at The Academy includes 28 educators: 22 African American, five White, and one Asian. Their educational credentials range from bachelor's degrees (36%) and master's degrees (36%) to education specialists (21%) and doctoral degrees (7%) (BCSD, 2021). Staff effectiveness is evaluated using the state's Teacher Keys Effectiveness System (TKES) and Leader Keys Effectiveness System (LKES).

Since its founding in 2014, The Academy has expanded its offerings to include a Twilight program, Personalized Learning Center (PLC), and Youth Build program, supporting students in smallgroup, community-focused environments. These initiatives reflect the school’s commitment to equity, access, and belonging.

Participants

Purposeful sampling was used to identify six educators with deep experience in The Academy model. Participants included the principal/director, the Positive

Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS) coach, media/technology teacher, Edgenuity coordinator, math teacher, and social worker. All had at least three years of experience in the model and consistently strong performance evaluations.

Each participant was invited through email and personal contact from the lead author. All six consented to participate. Pseudonyms were assigned to protect identities.

Data Collection

Data collection occurred over a fourmonth period during the 2021-2022 school year. Sources included:

• Interviews: Each participant was interviewed two times, using a semistructured interview, ranging from 45-75 minutes, conducted in person or via secure video conferencing.

• Observations: Eight on-site visits totaling approximately 20 hours. Observations included classroom walkthroughs, PBIS meetings, and informal interactions in hallways and common areas.

• Artifacts: School documentations, wall displays, bulletin boards, student work samples, and digital learning platforms.

• Researcher memos: Reflexive notes captured after each interaction, documenting impressions, analytic insights, and positionality considerations.

Interviews explored participants' professional histories, instructional philosophies, and experiences working with nontraditional students. Observations

focused on classroom culture, relational practices, and evidence of restorative and culturally sustaining pedagogy.

Data Analysis

Analysis followed a thematic cycle consistent with portraiture. In the first cycle of coding, in vivo coding was used to generate codes directly from the participants' own language (Saldana, 2013). During the second cycle, these codes were organized into axial categories that emphasized recurring patterns as well as important contradictions. From there, the categories were refined into themes that aligned with the study’s guiding frameworks of Critical Race Theory, Relational-Cultural Theory, and the school-to-prison pipeline. Once themes were established, individual vignettes were crafted for each educator, carefully highlighting their voices, the context of their work, and their distinctive contributions. Finally, the six portraits were woven together into a cross-case narrative, creating what Lawrence-Lightfoot and Davis (1997) have described as the “aesthetic whole.”

Analytic memoing was used throughout to track decisions and capture reflexivity. Negative case analysis was employed to ensure that disconfirming evidence was considered, such as examples where restorative practices did not resolve conflict. NVivo software (Version 12) was used to manage data.

Researcher Positionality

The lead author is a Black woman with professional experience in urban education. Her identity shaped both access and interpretation. Shared cultural background and professional knowledge facilitated rapport with participants, while also

requiring reflexivity to guard against overidentification. Memoing and peer debriefing were used to check assumptions and maintain analytic transparency.

The second author, who served as dissertation chair in the latter stages, is a white Jewish woman who has taught preservice teachers about cross-cultural awareness, culturally responsive pedagogies, and disrupting the school-to-prison pipelines.

The third author, who served as a dissertation reader, is a Black woman whose teaching and mentoring of diverse student populations inform her equity-centered perspective. Her lived experiences as a woman of color in higher education and commitment to critical qualitative inquiry shaped her contributions in aligning the conceptual framework with the findings and supporting reflexive dialogue throughout the analysis.

Trustworthiness and Credibility

The study incorporated several strategies designated to enhance credibility and trustworthiness. The first author engaged in continual reflexivity to identify and interrogate her subjectivities, while memoing about these subjectivities. Next, the first author engaged in a bracketing interview before initiating data collection. The first author also maintained an audit trail documenting each step of data collection and the analytical decisions that shaped the analysis. After data collection, the first author used member checking by sending each participant their respective transcript for review and revision, as the participant deemed necessary; then, the first author sent each participant their respective portrait for review and incorporated any feedback to confirm the accuracy of the

accounts. In addition, drafts of the findings were shared with two colleagues experienced in qualitative research, providing opportunities for peer debriefing and external insight. Finally, negative case analysis was employed deliberately including counterexamples and moments where themes did not fit neatly, which added nuance and complexity to the overall interpretation.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Valdosta State University Institutional Review Board and the participating district’s research office. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Pseudonyms were assigned, and data were stored securely on passwordprotected devices. Care was taken to present portraits in ways that honored participants’ voices while safeguarding confidentiality.

Results

Employing a portraiture methodology (Lawrence-Lightfoot & Davis, 1997), this study examined how educators at The Academy, a nontraditional high school in an urban southeastern RESA district, perceived and implemented an alternative education model aimed at supporting graduation rates for African American and Hispanic students from low-income backgrounds While each educator brought a distinct background and lens to their practice, they collectively envisioned education as a vehicle for healing, liberation, and justice.

Educator Portraits

Below we present a portrait for each participant.

Dr. Martin (Principal/Director)

Dr. Martin spoke with the quiet confidence of someone who had seen too many young people slip through the cracks. As principal, he framed his role less as enforcing rules and more as “building bridges back to trust.” He described attending student court hearings, making late-night phone calls to parents, and even driving students to interviews. “Leadership here is not about a title,” he said. “It’s about showing up when others don’t.” For him, success meant watching a student who once avoided school walk across the graduation state with a smile.

Ms. Daniels (PBIS Coach)

Ms. Daniels carried an energy that filled the room. She was the first to remind students that “behavior is communication” and the last to dismiss a child for acting out. Her role as PBIS coach meant she often mediated conflict, but she approached each situation with patience. “We don’t punish first; we listen,” she explained. She shared how restorative circles transformed a tense fight into an opportunity for peer accountability. While she admitted that not every circle ended neatly, she insisted that the process taught students to see themselves as part of a community that valued their voices.

Mr. Thompson (Media/Technology Teacher)

In Mr. Thompson’s classroom, technology was a tool for storytelling, not just skill practice. He encouraged students to use digital platforms to create projects that reflected their lives. “When they see themselves on screen, they realize their story has weight,” he said. One of his proudest moments was watching a student produce a short film about her neighborhood that was later showcased at a community event.

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

Though he acknowledged the challenges of limited resources and outdated equipment, he believed that giving students creative agency was one of the most powerful motivators for learning.

Ms. Lopez (Edgenuity Coordinator)

Ms. Lopez balanced structure with empathy as she guided students through online coursework. She often sat side by side with students, explaining a concept, then stepping back to let them regain confidence. “I remind them this isn’t about rushing, it’s about finishing,” she explained. Many of her students had been told they were behind, but she reframed pacing as personal progress. For her, the moment of pride came not in test scores but in a student’s realization that “I can do this.” That shift in mindset, she believed, was the true foundation for graduation.

Mr. Carter (Math Teacher)

Mr. Carter understood the weight math carried as both a gatekeeper and a fear for many students. “They come in already convinced they can’t,” he said. His approach was to dismantle that fear by breaking problems into small, meaningful steps and celebrating incremental victories. He often told students, “Math is just another language, and you already speak more than one.” His classroom became a place where mistakes were reframed as practice. Still, he acknowledged the frustration of balancing test preparation with relational teaching, a tension he navigated daily with persistence and humor.

Ms. Green (Social Worker)

For Ms. Green, the role of social worker meant far more than connecting students to services. She described herself as “the

listener in the gaps,” someone who caught stories others might miss. She helped students navigate homelessness, food insecurity, and family conflict, yet she never saw them as defined by those challenges. “They are resilient in ways most adults wouldn’t survive,” she reflected. She often sat with students in silence, offering presence rather than answers. For her, the most liberating act was reminding students that they were more than their circumstances and worthy of futures filled with possibility.

These portraits reflect the unique perspectives of each educator and their shared belief that students deserve affirmation, opportunity, and care. Taken together, their voices form the foundation for cross-case themes that emerged from the data.

Key Themes

We identified the following themes from the data:

From Hopeless to Hopeful: Redefining Success through Restorative Practice –

Educators described moving away from punitive discipline and toward restorative practices that emphasized care, accountability, and growth.

Disruptive Deficit Narratives – Teachers actively challenged deficit views of alternative school students, affirming their brilliance, resilience, and potential.

Centering Student Voice and Identity –

Participants highlighted the importance of culturally relevant lessons and opportunities for students to share their stories, identities, and agency.

Educators as Transformational Leaders –Staff emphasized that their work extended

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

beyond academics to include advocacy, mentorship, and systemic change.

Cross-Case Themes

Through analysis of the six educator portraits, four central themes were constructed to reflect the values, strategies, and philosophies guiding their work at The Academy. These themes demonstrate how educators responded to student needs while

also challenging systemic injustices embedded in traditional educational structures. Each theme is closely aligned with the study’s conceptual framework, comprising Critical Race Theory (CRT), Relational-Cultural Theory (RCT), and the school-to-prison pipeline, which together shaped both the analysis and the attitude of the school community.

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

Theme Definition Participant Quote Framework/RQ Link

From Hopeless to Hopeful: Redefining Success through Restorative Practice

Educators shifted away from punitive discipline toward restorative practices that emphasized care, accountability, and growth.

“We don’t suspend first. We sit down, talk, and ask what’s really going on. Nine times out of ten, it’s something deeper.”

RQ2 (Strategies): Illustrates how educators implemented relational practices. RCT: Connection and empathy fostered resilience. Pipeline: Disrupts exclusionary practices leading to incarceration.

Disruptive Deficit Narratives

Centering Student Voice and Identity

Teachers challenged dominant views that framed alternative school students as deficient, instead affirming their brilliance and potential.

Educators designed culturally relevant lessons and created opportunities for students to express their stories, identities and agency.

Educators as Transformational Leaders

Staff saw their role as extending beyond academics to include advocacy, mentorship, and systemic change.

“These are not throwaway kids. They’re some of the smartest, most intuitive learners I’ve ever met.”

“When they write about their lives, they start to see that their stories matter.”

“I’m not just a math teacher.

I’m a mentor, a counselor, a lifeline some days.”

RQ3(Barriers/Challenges):

Pushback against systemic deficit framing. CRT: Counterstorytelling to resist racialized assumptions.

RQ2 (Strategies): Shows how pedagogy affirms cultural identity. CRT + RCT: Culturally sustaining and relational approaches support liberatory education.

RQ1 (Experiences):

Demonstrates how educators perceive their roles. CRT + RCT + Pipeline: Educators resist structural neglect through radical care and advocacy.

From Hopeless to Hopeful: Redefining Success through Restorative Practice

At The Academy, success was not measured by test scores or rigid compliance, but by growth in emotional, relational, and academic areas. Educators actively worked to shift students away from punitive cycles and toward practices rooted in care, reflection, and accountability. Their use of restorative frameworks emphasized understanding of the roots of student behavior rather than defaulting to exclusion.

Disrupting Deficit Narratives

Educators at The Academy made a deliberate effort to push back against dominant narratives that frame alternative education as a place for students who are broken, unruly, or incapable. Instead, they described their students as brilliant, creative, and full of promise. They refused to let past labels or academic histories dictate students’ potential.

Centering Student Voice and Identity

Empowering students to speak their truths and see themselves reflected in their learning was a cornerstone of practice at The Academy. Educators took intentional steps to affirm student identity and create space for student agency. Lessons were personalized, culturally relevant, and often co-designed with students themselves.

Educators as Transformational Leaders

Participants consistently described their work as extending beyond the classroom. They served as mentors, case managers, liaisons, and advocates, building bridges between students and the institutions that so often failed them. Their leadership was grounded in proximity and a refusal to accept educational neglect as inevitable.

Discussion

The findings shared from this study illuminate how educators at The Academy conceptualized their roles, implemented practice, and challenged dominant narratives within alternative education. Their responses to the needs of marginalized youth were not only personal and pedagogical, but also deeply political. In addressing the three research questions, these educators positioned themselves at the intersection of care, resistance, and transformation, underscoring what it means to lead with both strategy and heart.

Reimagining the Educator’s Role: Advocacy, Restoration, and Relational Presence

In response to the first research question, which explores how educators perceive their roles in supporting students’ academic and personal growth, participants consistently described themselves as more than just instructors. They saw themselves as advocates, mentors, and stabilizers—adults who reliably showed up in students’ lives to affirm their worth, listen without judgment, and provide pathways back to trust. This aligns with the principles of RelationalCultural Theory, emphasizing mutual empathy and emotional attunement as essential to learning (Comstock et al., 2008; Miller, 1976).

Educators made it clear that emotional safety was not a luxury but a prerequisite for academic success. They met students where they were, academically, socially, and emotionally, recognizing that many carried trauma from past schooling experiences, poverty, or systemic neglect. These practices align with the trauma-informed approaches advocated by Souers and Hall (2016) and respond to what McGee and Stovall (2015)

GATEWAYS TO

have identified as the racial traumas produced when students are forced to navigate systems designed without them in mind.

Within a Critical Race Theory framework, these educators embodied what Dixson et al. (2005) called a “ground-level resistance,” using their daily interactions to interrupt deficit narratives and rehumanize students often pathologized in mainstream educational discourse.

Cultivating a Culture of Connection: Relational Structures as Resistance

The second research question inquired about how educators foster a positive school culture. At The Academy, this culture was not accidental; it was intentionally designed through structures that emphasized connection, care, and shared accountability. Restorative circles replaced punitive discipline. Personalized learning plans honored students’ unique journeys. Regular data meetings allowed staff to reflect, adjust, and respond collaboratively. And emotionally safe classrooms offered spaces where students could be seen and heard.

These practices reflect the core commitments of Relational-Cultural Theory, which frames growth as a product of connection, not control. In contrast to the zero-tolerance policies critiqued by Balfanz (2007) and the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (2014), educators at The Academy approached conflict as an opportunity to build rather than break relationships. This was not just a matter of tone; rather this was a deliberate rejection of the carceral logics embedded in traditional school discipline policies. Educators leveraged these relational strategies to resist the punitive cultures that dominate many alternative schools. Their

classrooms became spaces of belonging, coregulation, and cultural affirmation, aligning with what Ladson-Billings (1995) described as culturally relevant pedagogy rooted in justice and joy.

Reframing the Narrative: Challenging Myths of Deficiency

In response to the third research question, regarding how educators challenge dominant narratives about alternative education, participants offered compelling counter-stories that reimagined The Academy not as a last-chance placement but as a place of opportunity and excellence. Through language, actions, and pedagogical choices, they actively broke down the stereotype that students in alternative settings are deficient or disengaged.

This form of resistance is central to Critical Race Theory, which elevates counter-storytelling as a method for exposing and contesting racialized assumptions (Ladson-Billings and Tate, 1995). Educators at The Academy rejected the notion that their students were broken. Instead, they spoke of resilience, potential, and promise. Their classrooms affirmed student identity, and their leadership made room for students to communicate, create, and lead.

By reframing alternative education as a space for healing, growth, and affirmation, these educators also disrupted the trajectory of the school-to-prison pipeline. Rather than replicating the exclusionary practices that push students out, they cultivated systems of care that pulled students back in.

Limitations

As with all qualitative research, this study is bound by its context and scope. The

Academy is a unique environment with a strong culture of care, visionary leadership, and district-level support. These conditions were central to the school’s success but may not be easily replicated in other settings.

The study also focused solely on the perspectives of six educators. Although this aligns with the portraiture methodology, it does not capture the voices of students or families who directly experience the model. Including those perspectives in future studies could provide a more comprehensive view of the school’s impact.

Finally, the lead researcher’s identity as a Black woman with experience in urban education shaped the access and interpretation. This positionality enriched the analysis and also required reflexivity to guard against over-identification. Member checking, peer debriefing, and an audit trail were employed to support credibility.

Recommendations

The findings from this study suggest several pathways for practice, policy, and research that can strengthen alternative education and inform teacher education.

For Educators and Teacher Educators

Teacher preparation and professional development should move beyond technical training to include culturally sustaining pedagogy, trauma-informed practice, and relational competencies. Preservice teachers need opportunities to examine deficit narratives, practice restorative approaches, and learn how to affirm student identity. Embedding case studies from alternative schools like The Academy into teacher education programs can help future educators imagine what liberatory practice looks like in action.

For School and District Leaders

District leaders must ensure that alternative schools are not treated as lastchance placements but as innovation hubs. Adequate funding, smaller class sizes, and access to mental health support are critical. Leadership programs and specialized licensure pathways should be developed for educators working in nontraditional settings, given the unique demands of these environments.

For Policymakers

Policy must recognize the complexity of alternative education. Funding formulas should reflect the multiple needs of students who enroll in these schools, and accountability systems should value relational trust, student agency, and emotional growth alongside academic outcomes. Policymakers can also support legislation that reduces reliance on exclusionary discipline and promotes restorative frameworks.

For Families and Communities

Families and communities are essential partners in sustaining alternative models. Schools should create regular opportunities for families to engage in restorative practices, leadership activities, and curriculum planning. Community organizations can extend the work of schools by providing wraparound services such as housing, health care, and workforce training.

For Researchers

This study demonstrates the value of portraiture in elevating educator voice. Future research should expand this lens to include students and caregivers, whose experiences would enrich understanding of

alternative schooling. Longitudinal studies are also needed to track the long-term academic, social and emotional outcomes of students in culturally sustaining, traumainformed alternative schools.

Conclusion

The educators at The Academy provide a counter-story to the deficit narratives that too often surround alternative schools. Their portraits reveal teachers and leaders who act like builders of trust and advocates for justice. They remind us that liberatory education is not an abstract theory but a daily practice of care, relationship, and affirmation. They are not simply teachers; they are builders of trust, architects of belonging, and agents of change. Their work is grounded in the belief that relationships, cultural affirmation, and restorative practices are not luxuries but necessities for students who have been historically marginalized.

This study reaffirms the potential of alternative education when reimagined through a critical, relational, and justicecentered lens. By embedding the principles of Critical Race Theory, Relational-Cultural Theory, and a refusal to accept the inevitability of the school-to-prison pipeline, these educators offer a model for transformative schooling. The Academy is not a last chance; it is a new beginning. Their stories remind us that systems can be redesigned, healing is possible, and every student deserves a space where they are seen, known, and prepared to thrive.

References

American Civil Liberties Union. (n.d.). School-to-prison pipeline. https://www.aclu.org/issues/racialjustice/race-and-inequalityeducation/school-prison-pipeline

Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2021). Children in poverty by race and ethnicity in the United States. Kids Count Data Center. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tabl es/44-children-in-poverty-by-race-andethnicity

Balfanz, R. (2007, August). Locating and transforming the low performing high schools which produce the nation’s dropouts. Paper presented at Turning Around Low-Performing High Schools: Lessons for Federal Policy from Research and Practice, Washington, DC.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

https://www.oyez.org/cases/19401955/347us483

Comstock, D., Hammer, T. R., Strentzsch, J., Cannon, K., Parsons, J., & Salazar II, G. (2008). Relational-cultural theory: A framework for bridging relational, multicultural, and social justice competencies. Journal of Counseling & Development, 86(3), 279–287.

https://doi.org/10.1002/j.15566678.2008.tb00510.x

Dixson, A. D. & Rousseau Anderson, C. K. (2005). And we are still not saved: Critical race theory in education ten years later. Race, Ethnicity, and Education, 8(1), 7-27

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

Georgia Department of Education. (2020). Georgia Milestones Assessment System https://www.gadoe.org/CurriculumInstruction-andAssessment/Assessment/Pages/GeorgiaMilestones-Assessment-System.aspx

Goncalves, L. C., Endrass, J., Rossegger, A., & Dirkzwager, A. E. (2016). A longitudinal study of mental health symptoms in young prisoners: Exploring the influence of personal factors and the correctional climate. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-0160803-z

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003 465

Ladson-Billings, G., & Tate, W. F. (1995). Toward a critical race theory of education. Teachers College Record, 97(1), 47–68.

Lawrence-Lightfoot, S., & Davis, J. H. (1997). The art and science of portraiture. Jossey-Bass.

McGee, E. O., & Stovall, D. (2015). Reimagining critical race theory in education: Mental health, healing, and the pathway to liberatory praxis. Educational Theory, 65(5), 491–511. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12129

Miller, J. B. (1976). Toward a new psychology of women. Beacon Press.

Mujic, J. A. (2015, October). Education reform and the failure to fix inequality in America. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/ar chive/2015/10/education-solvinginequality/412729/

Pierce, C. (1970). Offensive mechanisms. In F. Barbour (Ed.), The Black seventies (pp. 265–282). Porter Sargent.

Roediger, D. R. (2005). Working toward whiteness: How America's immigrants became White: The strange journey from Ellis Island to the suburbs Basic Books.

Souers, K., & Hall, P. (2016). Fostering resilient learners: Strategies for creating a trauma-sensitive classroom. ASCD.

Stevenson, B. (2019). Just mercy: A story of justice and redemption. One World.

U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights. (2014). Civil rights data collection: Data snapshot (school discipline) https://ocrdata.ed.gov/assets/downloads/ CRDC-School-Discipline-Snapshot.pdf

Wells, A. S. (2018). Diverse neighborhoods, diverse schools? Benefits, barriers, and policy solutions to more integrated schools. Teachers College Press.

Wait! You’re Both Teaching Us?!: Coteaching in Higher Education

Heather M. Huling,1 Kathleen Crawford,1 and Catherine Howerter 2

1 Georgia Southern University

2 Texas Woman’s University

Abstract

This study explores co-teaching in higher education, specifically in an undergraduate literacy methods course. Traditionally employed in special education, co-teaching involves instructor collaboration to support diverse learners. In the context of this study, two elementary educators co-taught a Language Arts Methods course, modeling the practice for pre-service teachers. After modeling this practice for a semester, students completed a Qualtrics survey with qualitative and quantitative measures. The results showed strong student support for coteaching, citing increased engagement, exposure to multiple perspectives, and enhanced instructor accessibility. Key advantages included a dynamic learning environment and improved collaboration. The findings suggest co-teaching enhances teacher preparation and classroom dynamics, recommending its continued use in higher education. Future research should further examine co-teachers’ perspectives and the long-term impact on educators and students.

Introduction

Initial certification teacher education is meant to prepare pre-service teachers for their future classrooms through content

delivery, methods instruction, and field experiences in the K-12 setting. As teacher educators, we are responsible for preparing pre-service teachers through developing their content knowledge and pedagogical practices in our courses (Polly, 2022). One way we can do this is by modeling a variety of appropriate instructional strategies in our courses for our pre-service teachers, and one trend is to use a co-teaching model in higher education (Salifu, 2021). Co-teaching refers to the collaboration that occurs between a general education teacher and a special education teacher working together to meet the needs of a diverse group of students, including those with disabilities in general education settings (Friend, 2008). Coteaching is an instructional strategy that is typically taught and modeled in special education courses or within dual certification programs, where pre-service teachers are obtaining a general education and special education certification.

For this study, the co-teaching strategy was modeled in an elementary education and dual certification course, Elementary Language Arts Methods, by two general education elementary teacher educators. The purpose of this research was to examine elementary education pre-service teachers’ experiences with and perceptions of coteaching in higher education; thus, our

GATEWAYS TO

research question was: What are pre-service teachers’ perceptions and experiences with instruction in a co-taught elementary language arts methods course? In our study, we focused on the importance of modeling co-teaching at the higher education level.

This study aims to expand upon the existing research on modeling co-teaching for pre-service teachers. Morelock et. al. (2017) found that the modeling of coteaching practices in higher education was underrepresented within the literature, indicating the need for continued research. Bandura’s (1977) social learning theory highlights the importance of modeling in the learning process. According to this theory, individuals often learn by observing others, particularly when they are new to a role or skill. Proving the value of co-teaching in higher education, Hurd and Weilbacher (2017) found that pre-service teachers are more likely to be prepared for co-teaching when it is modeled for them. Kelly (2018) also described the benefits for teacher educators in providing more opportunities for collaboration, growth, efficiency, and mentorship between faculty.

Literature Review

As stated previously, co-teaching is a collaborative approach in which a general education teacher and a special education teacher work together to support a diverse group of students, including those with disabilities, within general education classrooms (Friend, 2008). There are six models of co-teaching: one-teach/oneobserve, one-teach/one-assist, station teaching, alternative teaching, and team teaching (Friend, 2021). “The practice of coteaching is a platform that can increase a variety of teaching and learning approaches through utilizing the expertise of more than one tutor [instructor] in the room and,

therefore, support individuals in their own way of engaging with the class” (Sweeney, 2021, p. 55). Chitiyo and Brinda (2018) state the following as benefits of co-teaching: Coteaching reduces the instructional fragmentation for students with disabilities, which might occur if they are moved from one classroom to another, ensuring consistency in their learning process. In higher education settings, university-level students in co-teaching settings indicate an appreciation for multiple perspectives, communication styles, and pedagogical practices from the instructors (Rooks et al., 2022). This union of two instructors creates an environment in the classroom where students feel comfortable with at least one, if not both, instructors (Rooks et al., 2022; Sweeney, 2021). Instructors are able to build relationships with students to create safe spaces in the classroom and best support the diverse needs of their students (Loertscher & Zepnik, 2019; Sweeney, 2021). It has also been shown that when students are engaged in co-teaching settings, there is greater student engagement, retention, and overall success (Kelly, 2018; Kerr, 2020; Sweeney, 2021).

A study completed by Chitiyo and Brinda (2018), when they surveyed 77 teachers, concluded that 44% of participants had learned about co-teaching through university training, suggesting that more than half of the teachers surveyed had no university training in co-teaching (p.47). Almost all the participants, 96%, acknowledged that they understood what coteaching is, yet only half of the participants, 50%, indicated that they were confident in using co-teaching. The findings from this study shed light on the urgent need for teachers to be adequately prepared in coteaching.

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

Co-teaching has been shown to improve the quality of teaching and student engagement in the higher education setting (Hurd & Weilbacher, 2017; Kerr, 2020; Loertscher & Zepnik, 2019). Morelock et al. (2017) noted that collaboration in planning and instruction showed increased effectiveness for both teachers and students. Engagement, academic achievement, and modeled pedagogy were among the benefits to the student population when taught in cotaught settings (Kerr, 2020; Loertscher & Zepnik, 2019). Faculty members collaborate and create respectful partnerships, share multiple perspectives and experiences, and provide individualized instruction based on student needs (Hurd & Weilbacher, 2017; Scherer et al., 2020).

Methodology

This mixed-methods study is based on a survey (Appendix A) from a co-taught Elementary Language Arts (ELA) Methods course where the authors sought to investigate pre-service teachers’ experiences and perceptions in a co-taught class at the university level. A survey was developed by the authors specifically for this study to gather pre-service teachers’ perceptions and experiences related to instruction in a cotaught course. The survey consisted of ten items, including a combination of Likertscale, open-ended, and illustrative response formats (see Appendix A). While the survey was not piloted or formally validated prior to data collection, its development was informed by relevant literature on coteaching and teacher preparation (e.g., Friend, 2014; Murawski & Dieker, 2013). The authors acknowledge this limitation of the study. The authors obtained approval from the University Institutional Review Board (IRB) to survey pre-service teachers enrolled in the ELA Methods course. The first two authors taught the ELA methods

course, and at the conclusion of the semester, the third author administered the survey to both co-taught classes. Of the 91 pre-service teachers enrolled in the course, 64 pre-service teachers were present in class and gave consent to participate.

Context

In this study, participants were preservice teachers enrolled in a collaborative ELA Methods course at a rural, mid-sized university situated in the southeastern United States. The course convened twice weekly over a span of 17 weeks. The first two authors were responsible for planning and teaching all four sections of the ELA course. The co-teachers of the course were current Elementary Education program faculty who frequently taught the ELA Methods course in previous semesters. The two instructors had also previously guest lectured in each other’s courses and collaborated on course content and activities. To facilitate the co-teaching approach, classes were merged in a large classroom during the first and second time slots as scheduled in the university course platform. In Table 1, the authors provide contextual information about the ELA Methods course the study took place in, including class time, number of students, and assigned instructor.

Table 1 Course Contextual Information

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

Throughout the semester, the first two authors collaboratively planned and implemented the ELA curriculum, employing a variety of co-teaching models as outlined by Cook and Friend (1995), with the primary model being team teaching. Team teaching, where both instructors share equal responsibility in teaching the class (Cook & Friend, 1995), was the natural selection for the co-teachers as they both share expertise in the content and methods related to the course material. This course was taught during two time slots (12:30 and 2:00) over a 15-week semester period to approximately 90 pre-service teachers (see Table 1). The pre-planned course content and assignments were identical between both course times as the co-teachers created and used a common syllabus. Interactive teaching methodologies were planned for and employed to actively engage pre-service teachers, with the instructors sharing instructional responsibilities equitably during all class sessions. The co-teachers shared the teaching time equitably within the course times, and each instructor was responsible for grading the assignments for the students listed on their individual rosters. Both instructors maintained office hours that coincided with the pre-service teachers' schedules as well as individual appointments upon request. Upon completion of the semester, the three-part survey was administered to examine pre-service teachers' perceptions and experiences with the co-teaching approach.

Participants

During the final week of the semester, an invitation to participate in the co-teaching study was extended to all pre-service teachers enrolled across the four sections of the course. Among the total 91 pre-service teachers, 64 provided consent and completed all segments of the survey. However, 15 pre-

service teachers chose not to submit the third part of the survey, which involved providing an illustration. Predominantly falling within the traditional college age range of 19-23, these demographics closely resembled those of the wider elementary education program at the university, encompassing approximately 250 preservice teachers.

Participants were at the midpoint of their junior year and had been admitted to the Teacher Education Program at the university, with their course of study leading to certification in grades PreK-5th grade and a Bachelor’s degree in Elementary Education. Prior to enrolling in the ELA Methods course, participants completed two field experiences: one involving 50 hours in a PK-5 classroom and the other consisting of 30 hours in a different PK-5 classroom. Throughout the duration of the ELA course, participants engaged in a third field placement totaling 150 hours. Within each of these field placements, pre-service teachers were placed in diverse classrooms, many of which involved working under the supervision of a clinical supervisor/mentor teacher who was in a co-teaching setting. Additionally, within the pre-service teachers’ field placement during the semester, they are required to co-plan and co-teach a read-aloud lesson.

Data Collection and Analysis

This mixed-methods study used both qualitative and quantitative approaches in the survey. The qualitative data came from open-ended questions and visual responses, while the quantitative data was gathered using a linear rating scale. In the final week of the semester, the third author administered the survey (Appendix A), which consisted of three sections: 1) openended questions, 2) linear scale/rating

questions, and 3) illustrations. The survey instrument included questions and prompts that were adapted from King-Sears, Brawand, and Johnson (2019) and are grounded in the literature on co-teaching (King-Sears et al., 2019). The first two parts of the survey investigated the pre-service teachers’ experiences and perceptions of coteaching in an elementary Language Arts Methods course. The third part, illustration analysis, mirrored the work of King-Sears, Brawand, and Johnson (2019), where the researchers examined patterns in the position of students and teachers in the classroom.

All three authors ensured consistency and trustworthiness through a collaborative analysis process to establish inter-rater reliability. To ensure inter-rater reliability, the authors initially coded the survey responses separately, and the team then collaborated to identify overarching themes (Merriam, 2009). By independently coding the open-ended responses and illustrations through an inductive approach then engaging in discussions about their findings, it allowed the researchers to refine the coding scheme and agree on consistent codes and emerging themes. Contradictions were discussed and explored collectively to maintain consistency across data analysis. This approach enhanced the credibility and dependability of the themes as described in the findings. This collaborative commitment to inter-rater reliability and consistency ensured the trustworthiness of this study.

Any identifying information from the open-ended questions or illustrations was redacted to ensure confidentiality. Within the survey instrument, the authors were able to gather three sets of data that explored the pre-service teachers’ perceptions of the coteaching experience. Using three distinct data sets enabled the authors to engage

thoroughly with the research and identify thematic connections across the sets, thereby facilitating data triangulation and enhancing the study’s trustworthiness (Amankwaa, 2016; Saldaña, 2016). The authors’ analysis and coding of the open-ended responses were validated through consistent patterns observed in the illustrations and the Likertscale ratings. Consequently, the triangulation of open-ended responses, Likert scale items, and visual illustrations served to confirm the findings through collaborative analysis by the co-authors.

To analyze the results of the first part of the survey, the authors began by using inductive analysis, as no pre-set codes were created based on the research question (Creswell & Poth, 2018; Saldaña, 2016). Each researcher individually read through the open-ended question responses and used holistic coding to analyze participants' perceptions and experiences with coteaching. Saldaña (2016) explains that holistic coding is useful when trying to identify basic issues "as a whole" rather than line-by-line coding (p.166). All three authors independently read through the entire data set, identifying segments of participants’ responses that were aligned with the research questions and creating initial codes. Initial codes included sorting the data into positive and negative experiences with co-teaching. The authors then met to share initial codes with each other, pattern matched the codes to narrow down a list of codes for all to use, and completed a second cycle of coding (Saldaña, 2016). The second cycle of coding was used to produce our main themes as delineated in the findings sections.

To analyze the results of the second part of the survey, the authors identified numerical trends and patterns in the dataset, as well as any outliers, using the three linear

scales and rating questions. These three questions allowed students to provide a numeric rating of their perceptions of the coteaching within the course. The authors computed responses in percentages and then compared them to the emerging themes from the qualitative data.

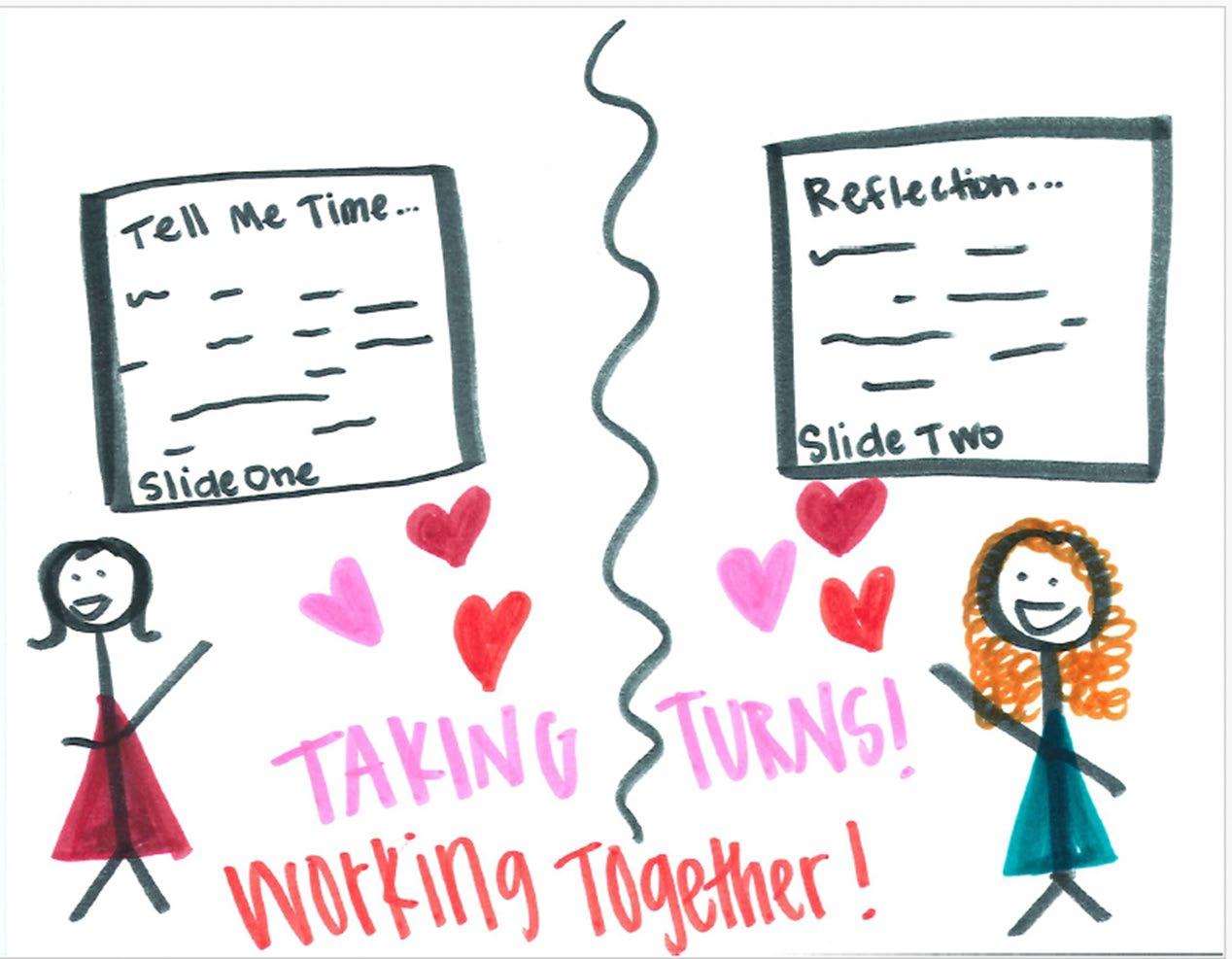

The directions to the final part of the survey, illustrations of co-teaching in practice, were as follows: Please use the paper and markers to create a picture that represents what a camera would see or hear when your teachers teach. You may use images, speech bubbles, labels, etc., to best represent your vision. To analyze part three of the survey, the authors independently examined the pre-service teachers’ illustrations and looked for patterns in the positions of pre-service teachers and the two teachers’ positions in the classroom to identify which models of co-teaching were most represented. The authors also analyzed trends in words or phrases used in labels and speech bubbles, and once those patterns were identified, the authors collaborated to create initial codes and formulate themes (Creswell & Poth, 2018).

The findings from the data analysis were organized into two categories based on the instrument: survey analysis findings and illustration analysis findings. Reporting in this style allowed for deeper understanding and connections of the themes that emerged from the qualitative data in the survey, as well as the illustration data in the drawings.

Findings

Survey Analysis

The research question for this study was: What are pre-service teachers’ perceptions and experiences with instruction in a cotaught elementary language arts methods

course? In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the pre-service teachers’ perceptions and experiences, we developed a survey comprised of ten questions (see Appendix A). The participants were also asked to create an illustration that represented their view of their co-teaching experience as part of the survey. The authors critically analyzed all data sets individually and collectively. The results are presented below by common themes noted in the data analysis. Common themes noticed across the survey and illustration included benefits of co-teaching, a positive classroom learning environment, and modeled effective coteaching strategies.

Benefits of Co-Teaching

Among the survey and illustration responses, the benefits of co-teaching were most frequently mentioned or rated highly among the data, specifically noting the support and accessibility and multiple perspectives. The responses reveal that 97.1% rated their recommendation as 4, indicating the highest level of support for co-taught classes. Both the mode and median ratings were 4, indicating a common agreement on the benefits and appreciation of co-teaching.

Support and Accessibility.

Being one of the most cited benefits of co-teaching from the data, support, and accessibility from the co-teachers were evident in their open responses, illustrations, and Likert scale data. Having increased support from two instructors in the classroom made the pre-service teachers feel more secure and confident in their learning. It allowed opportunities for more questions to be answered and feedback to be provided in a timely manner.

GATEWAYS TO TEACHER EDUCATION

Survey responses highlighted the benefits of the co-teaching approach and how it contributed to the students’ success, particularly the support provided by having two educators, which fostered a sense of security and confidence among students. One student noted, "There was always someone there to help me if I needed it.” Moreover, the increased accessibility and availability of teachers ensured that students' questions were addressed more efficiently, further enhancing their overall experience. Students expressed that teacher support was crucial, emphasizing the value of teachers being available to answer questions and provide assistance throughout lessons. Out of 64 responses, 98.3% of the students rated the helpfulness as 4, indicating the highest level of assistance and support. Both the mode and median ratings were 4, emphasizing a strong consensus among participants regarding the benefits of having two instructors present.

Multiple Perspectives

Another benefit noted in co-teaching from the participants was the use of multiple perspectives. The students noted appreciation in hearing the same content and information explained from different viewpoints based on the different experiences and expertise of each instructor. This is believed to contribute to deeper understanding and more comprehensive learning experiences based on the data.

According to the data, the presence of two teachers allowed the students to gain a broader understanding of the content, as they were exposed to multiple perspectives, with one respondent stating, "I have more than one perspective in the content area being taught." Additionally, students perceive co-teaching as beneficial for their learning experience, with one remarking,

"Having two professors offers even more information about a specific topic." Another student highlighted the advantage of receiving multiple perspectives: "You get to hear the same content from two teachers who might explain it a little differently.” Students appreciated the diverse perspectives from both instructors, as reflected in quotes like, "I love being able to hear from two different perspectives. If I don't quite get something when it's explained the first time, the other is able to provide an explanation I understand." Having the two instructors allows for more understanding across student learning as they are able to have content explained in multiple ways and various times throughout a lesson if needed.

Positive Learning Environment

Another theme noted among the survey and illustration responses is the positive learning environment, specifically noting the engaging aspects of the classroom, the interactive creative activities, and positive relationships within the classroom. The responses indicate that 85% of the students expressed enthusiasm for engaging and effective practices, highlighting the supportive classroom atmosphere and interactive activities.

Engagement in the Classroom

After analyzing the data, it was noted that the lively, engaging atmosphere in the co-taught classroom created a positive learning environment for the students. The students noted that they found it enjoyable to have two instructors as it brought additional energy to the classroom. The dynamic interaction between teachers also made the learning experience more enjoyable and engaging, with a participant commenting, "It made things so much fun,

and it gave a different atmosphere to the class!" A most prominent pattern from this data that emerged was the sense of fun and enjoyment in the co-taught classroom. One student mentioned, "It's really fun and it brings more energy to the classroom," while another student stated, "It helps to make class more engaging and upbeat!"

Interactive Creative Activities

The use of interactive and creative activities was noted in the data frequently in both the survey and illustrations. Students noted that it emphasized the positive energy in the classroom by catering to different learning styles and allowed for collaboration among students and co-teachers. The variety of teaching methods and activities kept students engaged and motivated them to learn the content in meaningful ways.

Creativity and enjoyment were also significant factors, with themed sessions and various activities enhancing the learning experience. Hands-on methods, such as interactive journals and anchor charts, were commonly used to facilitate active learning through direct engagement with the content. Additionally, variety and choice, through activities such as gallery walks and "this or that" exercises, appealed to diverse learning preferences and increased student engagement.

From the data, the most frequently cited activities within the open response survey question were "turn and talk" mentioned 22 times, interactive journals 15 times, and anchor charts 14 times. These interactive activities add to student engagement and understanding of the content, while also opening opportunities for creativity and collaboration. The illustrations supplemented these findings with drawings that depicted the co-teachers and their

instructional strategies, along with positive characteristics such as words and drawn facial expressions. Collaborative learning strategies, such as "turn and talk", “tell me time”, and group work, were frequently highlighted within the illustrations for encouraging peer interaction and idea exchange.

Positive Relationships

Students noted that the positive relationships within the course were a contributing factor to the learning environment and the overall co-teaching experiences. The co-teachers created a supportive and motivating environment for students that emphasized positive energy and open communication, where students could feel comfortable asking questions and participating in class. Fifty-five responses highlighted the importance of a positive atmosphere, praising instructors for their lively personalities and engagement. Comments such as "they should continue to be silly and engage with the students" and “they have great synergy” emphasized the role of engagement and the positive relationship between the students and coteachers in the classroom.