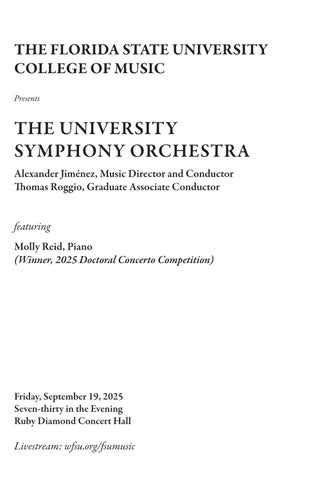

PROGRAM

The Bamboula: Rhapsodic Dance Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912)

Thomas Roggio, conductor

Concerto for the Left Hand in D Major, M. 82 Maurice Ravel Lento (1875–1937) Allegro

Molly Reid, piano

INTERMISSION

Nocturne for String Orchestra

Pini di Roma (Pines of Rome)

Alexander Borodin (1833–1887) arr. Malcolm Sargent (1898–1977)

Ottorino Respighi

I pini di Villa Borghese (Pines of the Villa Borghese) (1879-–1936)

Pini presso una catacomba (Pines Near a Catacomb)

I pini del Gianicolo (Pines of the Janiculum)

I pini della via Appia (Pines of the Appian Way)

Please refrain from talking, entering, or exiting while performers are playing. Food and drink are prohibited in all concert halls. Please turn off cell phones and all other electronic devices. Please refrain from putting feet on seats and seat backs. Children who become disruptive should be taken out of the performance hall so they do not disturb the musicians and other audience members.

Alexander Jiménez serves as Professor of Conducting, Director of Orchestral Activities, and String Area Coordinator at the Florida State University College of Music. Prior to his appointment at FSU in 2000, Jiménez served on the faculties of San Francisco State University and Palm Beach Atlantic University. Under his direction, the FSU orchestral studies program has expanded and been recognized as one of the leading orchestral studies programs in the country. Jiménez has recorded on the Naxos, Neos, Canadian Broadcasting Ovation, and Mark labels. Deeply committed to music by living composers, Jiménez has had fruitful and long-term collaborations with such eminent composers as Ellen Taafe Zwilich and the late Ladisalv Kubík, as well as working with Anthony Iannaccone, Krzysztof Penderecki, Martin Bresnick, Zhou Long, Chen Yi, Harold Schiffman, Louis Andriessen, and Georg Friedrich Haas. The University Symphony Orchestra has appeared as a featured orchestra for the College Orchestra Directors National Conference and the American String Teachers Association National Conference, and the University Philharmonia has performed at the Southeast Conference of the Music Educators National Conference (now the National Association for Music Education). The national PBS broadcast of Zwilich’s Peanuts’ Gallery® featuring the University Symphony Orchestra was named outstanding performance of 2007 by the National Educational Television Association.

Active as a guest conductor and clinician, Jiménez has conducted extensively in the U.S., Europe, and the Middle East, including with the Brno Philharmonic (Czech Republic) and the Israel Netanya Chamber Orchestra. In 2022, Jiménez led the Royal Scottish National Orchestra in a recording of works by Anthony Iannaccone. Deeply devoted to music education, he serves as international ambassador for the European Festival of Music for Young People in Belgium, is a conductor of the Boston University Tanglewood Institute in Massachusetts and serves as Festival Orchestra Director and artistic director of the Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp in Michigan. Jiménez has been the recipient of University Teaching Awards in 2006 and 2018, The Transformation Through Teaching Award, and the Guardian of the Flame Award which is given to an outstanding faculty mentor. Jiménez is a past president of the College Orchestra Directors Association and served as music director of the Tallahassee Youth Orchestras from 2000-2017.

ABOUT THE FEATURED SOLOIST

Praised for her “spellbinding” performances that feature “structural, long phrasing,” American pianist Molly Reid brings a distinctive voice to classical piano performance. Her command of sound and style has consistently earned her top prizes in competitions including the MTNA-Steinway & Sons Young Artist Piano Competition, the Rosen-Schaffel Young Artist Competition, the Annual Keyboard Competitive Festival at Florida State University, and most recently, the 2025 Florida State University College of Music Doctoral Concerto Competition. With the ability to let “expressivity be [at the] forefront of technical control,” her playing communicates the music with refreshing vitality.

Molly began her piano studies at a young age with her parents, both classical pianists. Her principal teachers include Heidi Louise Williams and Rodney Reynerson, with additional study under Ney Fialkow, Junie Cho, and Eugene Pridonoff. She has performed in master classes with many renowned artists including Boris Giltburg, Hung-Kuan Chen, Boris Berman, and Ksenia Nosikova.

Equally accomplished as a scholar, Molly has presented papers and lecture-recitals at national and regional conferences across the United States. Her work has been published in the Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy and recognized with the Best Student Paper Award at the national Pedagogy into Practice Conference. In 2024, she was one of 100 women doctoral students in the U.S. and Canada to be honored with the internationally competitive P.E.O. Scholar Award.

Holding degrees from the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music (MM) and Appalachian State University (MM, BM), Molly is currently a dual doctoral candidate in piano performance (DM) and music theory (PhD) at Florida State University, where she teaches undergraduate music theory and is supported with a Legacy Fellowship.

NOTES ON THE PROGRAM

Coleridge-Taylor: The Bamboula: Rhapsodic

Dance

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born in the central London neighborhood of Holborn in 1875. Soon after his birth, his family moved to the outskirts of London to Croydon, where he would spend the rest of his life. Named after the famed poet, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Coleridge-Taylor was born to Alice Hare Martin, a white Briton, and to Dr. Daniel Taylor, who was from Sierra Leone in West Africa. While Alice was pregnant, Dr. Taylor returned to West Africa, apparently not aware that Alice was pregnant, and never returned. Samuel would never know his father.

Coleridge-Taylor showed great talent for music and in 1890 he become a student in the renowned Royal College of Music in London. There he studied with Charles Villiers Stanford, who also claimed as his students such future luminaries as Ralph Vaughan Williams and Gustav Holst. Only the second black student to attend the College, Coleridge-Taylor was highly regarded among his peers and gained the attention of influential musicians of the day such as George Grove and Edward Elgar.

The Song of Hiawatha, a trilogy of three cantatas, would become Coleridge-Taylor’s bestknown works. Based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem of the same name, he found great similarities between the Native American and African American experiences and gave that synergy voice in The Song of Hiawatha. He also found a personal connection to Hiawatha who, like him, spends part of the poetic narrative searching for his absent father.

In writing The Song of Hiawatha, Coleridge-Taylor associated himself with the antiimperialism and Pan-Africanism movements of the day. As a leading delegate in the first Pan-African Conference in London in 1900, Coleridge-Taylor would gain recognition among African Americans as a symbol of hope thanks to his successes as a composer in Britain. According to historian Jeffrey Green, “For people of African birth or descent he had a role as a leader: a person whose achievements were to international standards, and whose successes countered concepts of racial inferiority.” Coleridge-Taylor first came to the United States in 1904 where he was treated as a celebrity. He conducted performances of his own music, became the first black man in American to conduct a white orchestra, and was one of very few people of African descent to be invited to the White House, where he was honored by President Theodore Roosevelt. Sadly, his life was cut short in 1912 when he died suddenly of pneumonia. His legacy would live on until World War II through annual performances of The Song of Hiawatha at Royal Albert Hall from 19241939, during which time the work would be performed as often as Handel’s Messiah and Mendelssohn’s Elijah.

Coleridge-Taylor wrote The Bamboula: Rhapsodic Dance for Orchestra in 1910 for the Litchfield Choral Festival in Connecticut. The Bamboula is an African drum and corresponding dance accompanied by these drums that came to the United States from Haiti during the exodus of African slaves deported from Haiti to Louisiana, specifically New Orleans. These slaves were known to dance the Bamboula on the so-called Congo Square near the French Quarter. The first appearance of the Bamboula in art music is found in a work for piano of the same name by the American composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk in 1848.

Coleridge-Taylor’s work is composed for a large orchestra that includes two flutes and piccolo, pairs of oboes, clarinets, and bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, and orchestra bells, and strings. A grand fanfare featuring the brass choir opens the work and introduces the primary Bamboula theme, an energetic dotted rhythm in 2/4 time that permeates the work. Coleridge-Taylor’s mastery of harmony and orchestral texture is clearly on display.

A tranquil middle section turns our dance theme into a lyrical song passed between solo woodwinds with a gently undulating accompaniment from the strings. The strings take over the tranquil melody with increasing intensity before returning to the original tempo and spirit of the work. Performances of this work are exceptionally and sadly rare. It is an honor to share this masterpiece with our audience tonight.

– Alexander Jiménez

Ravel: Concerto for the Left Hand

About 1930, Ravel found himself simultaneously with two commissions for piano concertos, one from his longtime interpreter Marguerite Long, and the other from Paul Wittgenstein, a concert pianist who had lost his right arm in World War I. Ravel worked on both commissions at the same time, but the results were quite different. The G major concerto, composed for Ravel’s own use, but eventually given to Marguerite Long when Ravel realized he was too ill to perform it himself, is a three-movement concerto part brilliant, part ravishingly melancholy. The Concerto for the Left Hand, perhaps inevitably, is altogether more serious, one of the most serious of all the works of that urbane master.

Paul Wittgenstein was a remarkable member of a remarkable Viennese family. He was the brother of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein, who also possessed considerable musical talent. Paul had barely begun his concert career when he was called into the Austrian reserves in 1914. Only a few months later he was wounded, and his right arm had to be amputated. After being captured by the Russians (when the army hospital in which he was located was overrun), Wittgenstein was exchanged as an invalid and returned to Vienna, where he resumed his concert career in the season of 1916-17. He quickly made a name for himself as a pianist with only one arm, and he induced many leading composers to write substantial works for him in all the genres—chamber and orchestral—that made use of a piano. Among those who responded to his requests were Richard Strauss, Franz Schmidt, Erich Wolfgang Korngold, Benjamin Britten, Sergei Prokofiev, Paul Hindemith, and, most famously, Ravel.

There are few sources of music for the left hand alone to which Ravel might have gone to study the problems involved, among them Saint-Saëns’s six studies for the left hand and Leopold Godowsky’s transcriptions for left hand alone of the Chopin etudes. He might also have seen Brahms’s mighty transcription for piano left-hand of the Bach D minor Chaconne for unaccompanied violin and Scriabin’s Prelude and Nocturne. But for the most part Ravel was on his own, especially as he wanted the piano part to be as full and active as if it were intended for a pianist who had both hands. The result, needless to say, is a fantastically difficult work perfectly gauged for the shape of the left hand (which can have, for example, a rather large stretch between the thumb and index finger in the higher pitch levels and the upper ends of chords, an arrangement that would be reversed if the piece were conceived for right hand).

Ravel once discussed his two piano concertos with the critic and musicologist M.D. Calvocoressi. Of the left-hand concerto he commented:

In a work of this sort, it is essential to avoid the impression of insufficient weight in the sound-texture, as compared to a solo part for two hands. So I have used a style that is more in keeping [than that of the lighter G major concerto] with the consciously imposing style of the traditional concerto.

The concerto is in one long movement divided into Lento and Allegro sections. Beginning low and dark in strings and contrabassoon, a long orchestral section avoids the first appearance of the soloist until a climax brings the piano in with a cadenza designed to show right off the bat that limiting the conception to a single hand does not prevent extraordinary virtuosity. Ravel describes this as being “like an improvisation.” It is followed by what Ravel called a “jazz section,” exploiting ideas he had picked up during his visit to America. “Only gradually,” he noted, “is one aware that the jazz episode is actually built up from the themes of the first section.” The level of virtuosity required by the soloist increases—if that is possible—to the end. Ravel rightly considered this, his last completed large-scale work, a supreme piece of illusion. Who can tell, just from listening, the nature of the self-imposed restriction under which he completed his commission?

– © Steven Ledbetter

Borodin: Nocturne for String Orchestra

The illegitimate son of a Russian prince, Borodin received a wide-ranging education that made him a precocious polyglot scientist and musician. As a composer, he became a member of the so-called Mighty Handful, Russian composers that included RimskyKorsakov, Mussorgsky, Balakirev, and Cui. However, he also became a noted chemist, so it is not surprising, perhaps, that his work list is shorter than probably any other composer of similar stature and the list is full of unfinished pieces.

He began the String Quartet No. 2 while on holiday in 1881. Because it often took years for him to complete multi-movement works, he wrote this work twenty years after his marriage, and the quartet was dedicated to his wife as an anniversary gift.

Borodin was a cellist, and it is clearly his voice in this beautifully lyrical work. The third movement of the quartet, Notturno (Nocturne) is one of the best known and most often arranged movements in the repertoire (musical theater fans may recognize it as the tune for “And This Is My Beloved” from Kismet). Tonight’s version by English conductor Malcolm Sargent is among the most often performed.

– Alexander Jiménez

Respighi: Pines of Rome

After Respighi moved permanently to Rome in 1913–at the time, a center of orchestral concerts in Italy–he turned more attention to the composition of instrumental music. His first big success was the symphonic poem, Fountains of Rome, from 1916, although it did not garner accolades immediately. But, by the early 1920s it was fast becoming an international hit, and he was on his way to world-wide recognition—not to speak of a much more secure financial future. He followed up on this success with two more symphonic poems evocative of his home: Pines of Rome (1924) and Roman Festivals (1926). Collectively, they are often known as his “Roman trilogy.” They all are showpieces for orchestra, spectacular evidence of his mastery of orchestration, vivid musical imagination, and flamboyant penchant for instrumental color. He had listened well to his predecessors who were successful in this vein.

Pines of Rome is cast into four movements, all using the conceit of pine trees that happen to be growing by various evocative Roman locations to tie everything together. Respighi scored the work for a large orchestra: the usual and familiar full complement, with additions of piano, organ, celesta, off-stage brass band, and (for the first time in musical history), a sound recording of a bird. All of these resources receive a full workout. Pines of Rome was an immediate hit; Toscanini was so enamored with it that he included it in the first concert—and nineteen years later, the last—that he conducted with the New York Philharmonic.

The first movement, “Pines of the Villa Borghese,” is a sparkling, lilting evocation of children playing on a Sunday morning, madly dashing about, full of youthful delight. The Villa Borghese is one of the largest public gardens in Rome, built in the informal English garden style, containing spectacular plantings, lakes, pathways, and buildings. It has long been a favorite with tourists and natives alike, and Respighi conjures up a bright musical context that depicts the cheerful setting. A filigree of attractive rhythmic figures and simple tunes clearly evoking childhood mirth sustains the fun-filled, light-hearted atmosphere. Woodwind trills, cheeky dissonances, glissandi in the harps and keyboards, high register brass, and the complete absence of “gloomy” low instruments sustain the joy.

It abruptly ends, though, as we enter the dark world of a catacomb. The second movement (“Pines Near a Catacomb”) is set in the malarial region of the Roman campagna, abandoned in ancient times, but with extraordinary stark beauty. The ominous, dark atmosphere of the burial caverns is aptly portrayed by most of the instruments that we did not hear in the first movement. Trombones, with the deepest of organ notes beneath them, don the garb of priests as they solemnly chant the melodies of the dead. The gloom is then broken by a shimmering solo trumpet, offstage in a lonely elegy. The chanting soon returns, building to a huge climax, more affirmatively, perhaps alluding to triumph over death. All soon dies down (no pun intended), as the brass returns to a crepuscular chant.

The “Pines of the Janiculum” is a tranquil visit at night to the prominent hill west of Rome where St. Peter is popularly thought to have been crucified, and which is now the site of a number of universities, colleges, and academies. It offers a spectacular view of Rome, and is named after the Roman god, Janus, who famously looked simultaneously in two opposite directions: the past and the future. This movement is a nocturne, opened by the gong and piano, introducing various woodwind solos that quietly evoke the moon on the pines. Apparently, a nightingale is perched in one of them, for as the music gradually fades away in trills, his song is faintly heard.

The nightingale is chased away, and the mood is ominously broken by the distant tread of the Roman Legions on the Appian Way (“Pines of the Appian Way”), beginning far off, perhaps in the morning mist, as they grow inexorably closer. A sinuous solo in the English horn adds a bit of mystery. Fanfares are heard, both in the orchestra and in the off-stage band that portrays the ancient Roman buccine—the large circular horns familiar from Roman mosaics. Everyone in the orchestra gradually joins in as the Legions march closer, and the music grows inevitably to a paroxysm of aural grandeur. It’s one of the most impressive moments in orchestral sound and never fails to please.

– © 2015 William E. Runyan

Violin 1

Jean-Luc Cataquet Santaella‡

Rachel Lawton

Masayoshi Arakawa

Javaxa Flores

Bailey Bryant

Keat Zhen Cheong

Mari Stanton

Emily Palmer

Francesca Puro

Stacey Sharpe

Elizabeth Milan

Abigail Jennings

Ilayda Ilbas

Violin 2

Ioana Popescu*

Christopher Wheaton

Sobin Son

Amanda Marcy

Samuel Ovalle

Alexa Dinges

Mariana Reyes Parra

Will Purser

Rose Ossi

Noah Johnson

Victoria Joyce

Carlos Cordero Mendez

Katherine Ng

Quinn French

Viola

Noel Medford*

Maya Johnson

Jeremy Hill

Tyana McGann

Hannah Jordan

Nathan Oyler

Yey Mulero

Spencer Schneider

Emelia Ulrich

Jonathan Taylor

Abigayle Benoit

Harper Knopf

University Symphony Orchestra Personnel

Alexander Jiménez, Music Director

Thomas Roggio, Graduate Associate Conductor

Cello

Mitchell George*

Noah Hays

Thu Vo

Natalie Taunton

Turner Sperry

Abbey Fernandez de Castro

Jake Reisinger

Sydney Spencer

Param Mehta

Ryan Wolff

Jaden Sanzo

Tia Stajkowski

Bass

Jarobi Watts*

Kent Rivera

Caleb Duden

Josh Dennis

Paris Lallis

Connor Oneacre

Flute

Pamela Bereuter*

Samuel Malavé

Kaitlyn Calcagino

Paige Douglas

Oboe

Gracee Myers**

Rebecca Johnson**

Steven Stamer

Rebecca Keith

English Horn

Gracee Myers

Clarinet

Jaxon Stewart**

Daniel Kim**

Hali Alex

Zhu Zhiyao

Bass Clarinet

Steven Higbee

Bassoon

Georgia Clement*

Timothy Schwindt

Hannah Farmer

Horn

Eric On*

Gio Pereira

Jeason Lopez

Allison Hoffman

Kate Warren

Trumpet

Avery Hoerman*

William Rich

Johniel Nájera

Noah Solomon

Trombone

Connor Altagen*

Elijah Van Camp-Goh

Bass Trombone

Maxwell Brower

Off-Stage Brass

Jeremiah Gonzalez

Sharavan Duvvuri

Avery Hoerman

Wayne Pearcy

Nathan Reid

Cayden Miller

Percussion

Darci Wright

Ian Guarraia

Jordan Brown

Matthew Korloch

Caitlin Wright

Harp

Ava Crook

Piano

Bryden Reeves

Celesta

Cristian Dirkhising

Orchestra Manager

Za’Kharia Cox

Orchestra

Stage Manager

Carlos Cordero Mendez

Orchestra

Librarians

Guilherme Rodrigues

Tom Roggio

Library

Bowing Assistant

Victoria Joyce ‡ Concertmaster * Principal ** Co-Principal

UNIVERSITY MUSICAL ASSOCIATES 2025-2026

Les and Ruth Ruggles Akers

Dr. Pamela T. Brannon

Dean’s Circle

Richard Dusenbury and Kathi Jaschke

Joyce Andrews

Patrick and Kathy Dunnigan

Kevin and Suzanne Fenton

Andrew and Karen Hoyt

Alexander and Dawn Jiménez

Jim Lee

Paula and Bill Smith

Margaret Van Every

Gold Circle

Albert and Darlene Oosterhof

Bob Parker

Todd and Kelin Queen

Karen and Francis C. Skilling

Bret Whissel

Sustainer

Stan and Tenley Barnes

Kathryn M. Beggs

Karen Bradley

Steve and Pat Brock

Suzi and Scott Brock

Brian Causseaux and David Young

James Clendinen

Mary and Glenn Cole

Sandy and Jim Dafoe

John S. and Linda H. Fleming

Joy and James Frank

William Fredrickson and Suzanne Rita Byrnes

Ruth Godfrey-Sigler

Ken Hays

Dottie and Jon Hinkle

Todd S. Hinkle

The Jelks Family Foundation, Inc.

Emory and Dorothy Johnson

Gregory and Margo Jones

Anne van Meter and Howard Kessler

William and Susan Leseman

Annelise Leysieffer

Linda and Bob Lovins

Marian and Walter Moore

Ann W. Parramore

Almena and Brooks Pettit

David and Joanne Rasmussen

Edward Reid

Mark and Carrie Renwick

Richard Stevens and Ron Smith

William and Ma’Su Sweeney

Martin Kavka and Tip Tomberlin

Steve Moore Watkins and Karen Sue Brown

Stan Whaley and Brenda McCarthy

Kathy D. Wright

Joe and Susan Berube

Marcia and Carl Bjerregaard

Sara Bourdeau

David and Carol Brittain

Bonnie and Pete Chamlis

Rochelle Davis

Judith Flanigan

Harvey and Judy Goldman

Jerry and Bobbi Hill

Judith H. Jolly

Arline Kern

Jonathan Klepper and Jimmy Cole

Keith Ledford

Judy and Brian Buckner

Marian Christ

Sarah Eyerly

Gene and Deborah Glotzbach

Sue Graham

Laura Gayle Green

Donna H. Heald

Carla Connors and Timothy Hoekman

Jane A. Hudson

Jayme and Tom Ice

Stephanie Iliff

William and DeLaura Jones

Jane Kazmer

Patron

Joan Macmillan

Joel and Diana Padgett

Karalee Poschman

Mary Anne J. Price

Magda Sanchez

Jill Sandler

Jeanette Sickel

Susan Sokoll

George Sweat

Sylvia B. Walford

Geoffrey and Simone Watts

Natalie Zierden

Associate

Paige McKay Kubik

Joe Lama

Jane LeGette

Eric Lewis

Cindy Malaway

Lealand and Kathleen McCharen

Dr. Linda Miles

Becky Parsons

William and Rebecca Peterson

Susan Stephens

Allison Taylor

Karen Wensing

Lifetime Members

Willa Almlof

Florence Helen Ashby

Mrs. Reubin Askew

Tom and Cathy Bishop

Nancy Bivins

Ramona D. Bowman

André and Eleanor Connan

Russell and Janis Courson

J.W. Richard Davis

Ginny Densmore

Carole Fiore

Patricia J. Flowers

Hilda Hunter

Julio Jiménez

Kirby W. and Margaret-Ray Kemper

Patsy Kickliter

Sallie and Duby Ausley

Anthony M. Komlyn

Fred Kreimer

Beverly Locke-Ewald

Cliff and Mary Madsen

Ralph and Sue Mancuso

Meredith and Elsa L. McKinney

Ermine M. Owenby

Mike and Judy Pate

Laura and Sam Rogers

Dr. Louis St. Petery

Sharon Stone

Donna C. Tharpe

Brig. Gen. and Mrs. William B. Webb

Rick and Joan West

John L. and Linda M. Williams

Corporate Sponsors

Beethoven & Company

Business Sponsors

WFSU Public Broadcast Center

The University Musical Associates is the community support organization for the FSU College of Music. The primary purposes of the group are to develop audiences for College of Music performances, to assist outstanding students in enriching their musical education and careers, and to support quality education and cultural activities for the Tallahassee community. If you would like information about joining the University Musical Associates, please contact Kim Shively, Director of Special Programs, at kshively@fsu.edu or 850-645-5453.

The Florida State University provides accommodations for persons with disabilities. Please notify the College of Music at 850-644-3424 at least five business days prior to a musical event if accommodation for disability or publication in alternative format is needed.