One of the greatest contributions of photography is its ability to accurately capture the world in all its forms. Correspondingly, notions of truth, (and indeed the opposite), have also been shaped by discourses surrounding the relationship between image-making and reality. The works of Lavender Chang, however, gently prod us to reconsider the value of images as principally one that lies in the portrayal of likeness or exactitude.

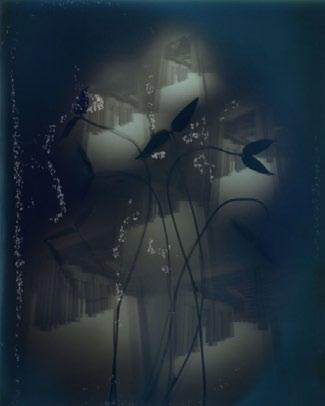

In the exhibition A Glimpse of Radiance from Under, Chang presents a new series of works titled Don’t Walk In Front of Me, I May Not Follow (2021). At first glance, the viewer may perceive the images as abstract landscapes, helmed by a horizon which vacillates between daybreak and twilight. Atmospheric ombre shades interchange with a phenomena of radiant light that shifts to darkness or brightness in an instant. We do not know this place. Perhaps we are looking at vignettes of an alternative world, somewhere that we cannot grasp the totality of, and yet sense we are getting a glimpse into something that must exist.

Lavender Chang, Don’t Walk In Front Of Me, I May Not Follow #13 (2021) Fine art archival print, Edition of 3 + 2 Artist’s Proof, H72 x W100 cm/H100 x W139 cm

Lavender Chang, Don’t Walk In Front Of Me, I May Not Follow #13 (2021) Fine art archival print, Edition of 3 + 2 Artist’s Proof, H72 x W100 cm/H100 x W139 cm

Glimpse of Radiance from Under (2022)

Gallery, Singapore

view

In actuality, these works were developed by Chang on the premise of embarking on a journey to nowhere, taking pictures without purposefully framing them. The result is a series of everyday scenes that appear as otherworldly places. One might be surprised to learn that in fact these “abstract landscapes” comprise scenes at a suburban mall, peppered with the minutiae of sundry shops, the hustle and bustle of a coffeeshop, an unremarkable sheltered walkway of an HDB estate. Chang’s interest, however, lies not so much in the symbolism or the thematics of a place, but on approaches to photography that can reveal visions of things that cannot be seen.

1 Lyle Rexer, The Edge of Vision: The Rise of Abstraction in Photography, Aperture: D.A.P., New York, 2009, p 9-10

2 Rachel Ng, “Time Present: Photography from the Deutsche Bank Collection” in Still Moving: A Triple Bill on the Image, Singapore Art Museum, Singapore, 2014, p8-9

In his writings on contemporary photography, Lyle Rexer makes a distinction between abstract photography and another of a more investigative nature. The latter relates to the rise of the artistic tendency towards “undisclosed images” that privilege a way of “novel seeing”, marking a shift away from formalist discourses regarding the representation of the real. He calls such endeavours an “investigative or undisclosed photography”, whereby the outcome of photographic images are not premeditated because artists working in this mode embrace “the freedom that can encompass all the artifacts of harnessed light, and its absence.”1

We begin to see how this informs Chang’s work from the recurring themes in her practice that explore the imperceptible qualities of time, and its transience. Chang’s works stem from a methodological approach that recognises the shifting dynamics between space and time, as well as chance occurrences which determine the outcome of her images. However much they depart from veracity, they are also a critical documentation of the less considered context of the photographic duration, which stands for the artist a legitimate element in reflecting the reality of the subject matters in her work.

That time is an abstract and organic entity, is a premise that curator Rachel Ng articulated in her 2015 exhibition and essay Time Present. Citing Roland Barthes’ pronouncement of a new space-time characteristic in photography that embodies “spatial immediacy and temporal anteriority”, the image becomes a “conjunction between the here-now and the there-then.” Ng describes the fundamental connection between time and photography as such: “By seemingly extracting a sliver of time, photography imparts onto itself a historical-temporal specificity that augments its ‘real-time effect’ and stamps it with existential authenticity”.2 She could very well have been describing Chang’s work, whose images demonstrate a condition of perpetually being in-formation in the context of passing time.

Lavender Chang, Don’t Walk In Front Of Me, I May Not Follow #0 (2021) Single channel video (00:10:00), Edition of 20 + 2 Artist’s Proof

Lavender Chang, Don’t Walk In Front Of Me, I May Not Follow #0 (2021) Single channel video (00:10:00), Edition of 20 + 2 Artist’s Proof

Chang’s works are largely created through long exposure settings which allow for a duration to be documented in a single image. Her Don’t Walk works were created by mounting a moving medium format camera at the approximate height of seven inches above ground, as the artist went on a walk through the course of a day. Floating Rays of a Wanderer (2019), an earlier series of work was conceived with a similar approach and carried out over a few excursions, but staged in a manner to consider the dimension of speed. The latter was premised on the artist following a random stranger onto a bus and documenting the journey. In doing so, Chang relinquished control of the kind of images she may yield: for the destination of the ride, the position where she sat and where the camera would be placed, depended on the decisions of a stranger. The resultant images can be described as a visual time stamp of his or her journey, moulded into being by location and light in flux.

In her study of works depicting artist-altered environments, Liz Wells proposes a way of viewing such works, as an experience of a sensation of place that is based on the connection of circumstances, places and people rather than visual facts.3 We can sense this in Chang’s works of compressed, overlapping moments which reveal the liminal, transitory states of places, as the artist attempts to, if not close the gap between reality and representation, then most certainly to show what that gap may possibly resemble.

There is yet another context that differentiates the two bodies of work presented in this exhibition, and it is one of proportion and scale. This essay describes the method of Chang’s Don’t Walk series via a camera being mounted at seven inches above ground. In the actual words of the artist, it is placed at a “cat’s eye level.” While this anecdotal detail may explain the difference in the proportion of the foreground in these works compared to those in Floating Rays, the prospect of the source of perspective in Chang’s art is deserving of more attention. In fact, this curiosity of the inner life and visual field from non-human perspective goes back to her earlier 2016 work The Movingly Minute Scale of a Restricted Life, a year-long project in which the artist had placed a pinhole camera with a live bean plant inside, on the windowsills of 15 different households, to record both the plant’s progress and its view of the external world.

Previous page: Lavender Chang, Wanderer #10 (2019)

Fine art archival print, Edition of 3 + 2 Artist’s Proof, H81.45 x W100 cm | H100 x W122.7 cm

Detail

Left:

A Glimpse of Radiance from Under (2022)

FOST Gallery, Singapore

Installation view

Top, from left to right: Lavender Chang, #14-312 (2016), #08-140 (2016), #24-616 (2016), No. 24 (2016), #16-559 (2016)

4 Michelle Ho, “Lavender Chang” in In Praise of Shadows, ADM Gallery, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, 2017, exhibition brochure.

Over the lifespan of each bean plant, her cameras yielded solargraph images of the plants in the most unlike setting for growth. Devoid of sunlight and optimum nutrients, the images nonetheless provide a surreal documentation of nature’s survival against the odds, if only for a moment.4 It would be inaccurate to suggest such images as a possible view of the world from other species. But what we can gather is Chang’s artistic sensibilities that seek to expand our view of the world in reimagining the vast extent of range and scale of vision, however minute or magnificent.

Through conceptual gestures like these, Chang reminds us of the potential and capacity of yet other unseen things, beyond what the human eye can possibly perceive.

Lavender Chang’s focus lies in conceptual photography. Chang’s work is a reflection of the sensitivity towards the subtle nuances surrounding her. She hopes to focus on these experiences, to create a canvas allowing further contemplation and letting the passage of time to leave behind traces of her mortality.

In 2011, she was the recipient of the Gold Award at The Crowbar Awards, Singapore, and was the winner of the Noise Singapore Prize. Chang was one of the winners of the 2012/2013 Affordable Art Fair’s Young Talent Programme. In 2013, she held her winner’s solo show in ION Art Gallery, Singapore. In 2015, she won the 6th France+ Singapore Photographic Art Awards. In 2016, her collaboration with &Larry won the President Design Award’s Design of the year. In 2018, her cinematography work for John Clang’s debut feature film, Their Remaining Journey, premiered at the 2018 International Film Festival Rotterdam and garnered a nomination for the festival’s Bright Future Award. It is also the opening film for the National Gallery Singapore’s Painting with Light: Festival of International Films on Art. In 2020, A Love Unknown is selected by the International Film Festival Rotterdam for its Bright Future Main Programme and Asian premiere at the 12th DMZ International Documentary Film Festival, on Singular Screens by Singapore International Festival of Arts, curated by Asian Film Archive in 2021.

PICTURED: Portrait, Lavender Chang Image Courtesy of the Artist

PICTURED: Portrait, Lavender Chang Image Courtesy of the Artist

Michelle Ho is a curator with over 15 years’ experience in Southeast Asian contemporary art. As director of the NTU ADM Gallery, she launched a new curatorial vision that connected contemporary art with the university’s research fields. Some of her recent exhibitions include Vertical Submarine and the Amusement of Knowledge and Illusion (2022), Reformations: Painting in post 2000 Singapore Art (2019) and Exceptions of Rule: Counterpoints to Truth (2018). Formerly a curator at the Singapore Art Museum, she has led the acquisition strategies of its contemporary art collection from 2013 to 2015, and co-curated exhibitions with museums such as Queensland Art Gallery (QAGOMA), Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo (MOT) and Kunsthaus Zurich. She was also co-curator of the 2013 Singapore Biennale. In 2020, she was appointed curator for the Singapore Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale.