NOV/DEC 2025 COMPLIMENTARY

BRENT WIESENBURGER, DIRECTOR OF AG TECHNOLOGY SERVICES, AGTEGRA

BRENT BELIEVES THAT PRECISIONAG IN THE DAKOTAS IS ABOUT TRUSTABLE DATA, SMARTER TOOLS, AND PRACTICAL ROI! PG. 22

NOV/DEC 2025 COMPLIMENTARY

BRENT WIESENBURGER, DIRECTOR OF AG TECHNOLOGY SERVICES, AGTEGRA

BRENT BELIEVES THAT PRECISIONAG IN THE DAKOTAS IS ABOUT TRUSTABLE DATA, SMARTER TOOLS, AND PRACTICAL ROI! PG. 22

Fequipment rests in the shed. But this “downtime” is anything but unimportant. Winter offers farmers a rare opportunity to step back, reflect, and recharge for the year ahead.

After months of long days, unpredictable weather, and constant demands, taking time to pause is, when you can—we know you still have things to do, it’s a necessity. Winter allows for planning and preparation in ways that busy planting and harvest seasons never permit. It’s the time to evaluate what worked, what didn’t, and to strategize improvements for the next cycle. You can review machinery maintenance schedules, update farm records, and explore new technologies or methods that could increase efficiency in the coming year.

Beyond planning, winter provides space for personal restoration. Farming is physically and mentally demanding, and the constant push through stressful seasons can take a toll.

Quiet winter days allow farmers to reconnect with family, pursue hobbies, and focus on health—both mental and physical. These moments of rest help prevent burnout and ensure farmers return to the fields in spring with renewed energy and perspective.

Moreover, winter can inspire creativity and innovation. Reading, attending workshops, or networking with other farmers and experts during this slower period can spark ideas that transform farm operations. The downtime can be as productive as planting season when used intentionally.

In agriculture, every season has its rhythm. Winter may seem like a pause, but it’s also a vital part of the cycle. Taking time to slow down, reflect, and prepare ensures that when the first snow melts, farmers are ready not just to work, but to thrive.

Brady Drake Future Farmer Editor

Written by Scott Wagendorf based on an interview with Alex Vasichek, Financial Planner

Planning has been the backbone of successful farming operations for decades. It transforms a high-risk activity into one that is more predictable, manageable and sustainable over the life of the farm—across multiple generations.

But the opposite is also true. A lack of planning can be costly. Imagine building a legacy for generations before being forced to carve up land and machinery among heirs who have little or no interest in farming. Even if one sibling chooses to remain on the farm, the others will likely cause the estate to be sold off.

While renting may seem like a viable default option that keeps all parties happy, consider this: Depending on the farmable land’s location and soil quality, an heir in Cass County, ND might earn an average of $129 an acre renting vs a one-time sale price of $4,549 per acre (according to a 2024 Five-Year Average survey conducted by the North Dakota Department of Trust Lands).

In other words, it would take roughly 35 years to recover the sales price. That’s 35 years the non-farming heirs would have no access to the remittance while the heir/s who chose to continue farming would be able to derive maximum value and benefit during that time.

By Brady Drake | provided by Agtegra Cooperative

Agtegra Cooperative, “innovation” isn’t a buzzword stuck in the tech corner. It’s a daily, whole-co-op habit— grain, agronomy, energy, feed, and every team in between looking for ways to serve members better, faster, and with more peace of mind than they realized they were missing.

That mindset shows up in big moves, like precision platforms and data systems built for real-world farms, and in small ones, like a propane keep-full monitor that quietly removes a winter headache. For Agtegra, innovation is only worth chasing if it improves efficiency, profitability, and service for the people who own the co-op.

To dig into what that looks like on the ground, we sat down with Brent Wiesenburger, Director of Ag Technology Services, to talk about how Agtegra decides where to push next, what’s changing (and what isn’t) in ag retail, and why the future of precision ag in the Dakotas is about trustable data, smarter tools, and practical ROI—not noise.

Agtegra Cooperative is an innovative, farmer-owned agricultural co-op headquartered in Aberdeen, South Dakota, serving producers across eastern North Dakota and South Dakota. Formed in 2018 through the unification of South Dakota Wheat Growers and North Central Farmers Elevator, Agtegra is built on a long legacy of local cooperative service while operating at modern scale. Today it supports roughly 6,800–7,000 memberowners through a network of 70+ locations, offering a full suite of grain, agronomy, energy, feed, and farm supply services, along with precision ag and technology support designed to improve efficiency, profitability, and quality of service on member farms.

BRENT WIESENBURGER

Director of Ag Technology Services, Agtegra

Q: WHEN YOU THINK ABOUT YOUR CO-OP’S IDENTITY, WHAT DOES “INNOVATION” ACTUALLY MEAN?

A: To me, Innovation from our co-op's perspective means every division finding ways both internally and externally that can increase our level of service and triggers the, “I didn’t know I needed this, but I do,” thoughts from our employee’s and/or patrons. For instance—I am a propane customer and a simple innovation they provided for me was a to keep full monitor 75 miles away from my house at my parents’ shop. This guarantee’s the tank never runs dry, and dad can blow snow in the middle of winter and not worry about the tractor not starting. This was peace of mind I didn’t know I needed. I also believe we need to drive innovation within the companies that sell us goods and services as well. The more efficient they can be, the more cost savings we can pass on to our member owners.

Q: IF YOU HAD TO EXPLAIN YOUR CO-OP’S APPROACH TO INNOVATION TO A MEMBER AT THE COFFEE SHOP, WHAT WOULD YOU SAY?

A: Agtegra’s primary focus is on products and services that will improve efficiency, profitability, and service for our member owners!

THE TRUTH IS THAT THE AG RETAIL FLEET (NOT ONLY AGTEGRA) STRUGGLES TO KEEP PACE WITH SPRING FERTILIZER APPLICATIONS. THE BIG THREE MANUFACTURERS NEED TO BRING US BIGGER, BETTER SOLUTIONS."

A: We have grown thru unifications/mergers, so we continue to grow, with that growth, we added regional dispatch groups to control workflow of our custom application fleet. This has been instrumental in efficiency and machine utilization across our footprint. What hasn’t changed fast enough is the size and speed of self-propelled fertilizer spreaders and application equipment. Growers continue to have larger and faster planters that are capable of hundreds of acres a day. The truth is that the ag retail fleet (not only Agtegra) struggles to keep pace with spring fertilizer applications. The big three manufacturers need to bring us bigger, better solutions.

A: From an Ag Tech perspective, trying to drive costs out of the crop production cycle is a definite opportunity. Whether it’s split application of Nitrogen, or using yield data to identify nutrient removal’s instead of soil testing, I believe there are ways to use “data” to achieve these goals accurately. The accuracy of weather models and disease monitoring tools are getting better as well. These can help our growers and agronomists make more informed decisions on crop protection investments in real time.

A: We have an amazing employee team that have great ideas. We also have patrons that have great ideas. I think the ability to innovate is only held back by the amount of money you want to throw at it. Ultimately, the decision must be made on where the biggest opportunity is with the challenge you are trying to solve. So, I guess it comes back to whatever provides the best improvement with efficiency, profitability, and service for our member owners

A: Again, from an Ag Tech perspective, the ability to leverage AI to solve data problems and interoperability is big. Pointing an AI tool at an ag database today is pointless if it’s bad data. Every field we touch in our Ag Tech program needs post processing to fix data collection issues from planter data to yield data. Scaling this post processing is a big opportunity we are working on. Only after we can trust this data can we start to make better decisions for our producers that are sharing it. I am very exited for the future in this segment of our tech portfolio.

A: I am very proud of the formation of FieldReveal in 2017. FieldReveal is our Ag Technology platform that handles VR prescription writing and zone management creation, soil sample analysis storage, and yield data analysis. This important decision by Agtegra, Central Valley Ag Cooperative, The McGregor Group, and Winfield United allow us to be isolated from all the noise in the Ag Tech software space and ultimately drive development of solutions from the ground up with real users. Looking at all the acquisitions and door shuttering in FMIS systems in the US, Agtegra and the rest of the owners are fortunate to not have to undergo these changes to their Precision Ag Platforms and deal with the training of new systems and the challenges association with data transfer between them.

A: We are constantly monitoring this space and actively evolving in it as well. Whether its accounting information served instantly to our patrons, historic customer sales data served to the grower’s salesperson, or automated alerts from tank sensors letting our fuel department know a farm is low on fuel on propane, every segment of our business is actively engaging with our customers more efficiently and accurately. From an Ag Tech perspective, there are exciting opportunities leveraging AI on historic datasets to bring grower specific solutions to the table—this is a real opportunity as well. The Ag Tech sector has been promising value out of the data growers and retailers have been collecting and in my opinion under delivering on that promise. AI will help us change this narrative in the future I believe.

A: Agtegra has been very open to assist in product development or research. This is vital to moving the agricultural industry forward. Whether providing soil tests for university research, feedback on product or hardware performance, or simply go to market strategies, we participate in all aspects of innovation. We want to only promote truly valuable products that bring ROI to our patrons; this strategy helps us identify those next big opportunities in Ag.

A: Our high adoption of no till and historic weather variances as driven variable rate adoption within our footprint to very high levels. Growers really understand the importance of targeted application rates to drive profitability. This keeps us keenly focused on the next value proposition relative to our Ag Technology portfolio

A: I believe we are seeing a transition in weather patterns that is shifting the “Cornbelt” west in the US. The yields have been phenomenal the last couple of years. So, I bet we see continued yield increases in corn, and a higher utilization of Ag Tech programs like zone management and VR crop nutrition and seed scripting. The Dakotas have always been very supportive of Ag Technology, but with increased yields, comes increased inputs—this makes Precision Agriculture a vital part of crop production

A: From my perspective a big concern is the ability find help that understands the long hours, and work involved in providing a great experience for our Patrons. What gives me the most optimism is the Innovation happening in autonomy. Whether it’s a tractor or spreader working unmanned or possibly an elevator that requires less people, there are great things coming relative to technology. It will be exciting to participate in the evolution.

A: I have talked about our VR adoption of fertilizer and seed, a ratio that is unheard of in the industry. We generated nearly 700K acres of VR crop nutrition recommendations for the 2025 crop year. Nearly 92% of those fertilizer recommendation had a VR plant population map get imported to a grower’s planter display to match planting rates with crop nutrition rates. Our agronomists provide a tremendous amount of value to the growers utilizing this technology. I am so proud of the team that helped us generate these numbers.

About Shannon Hauf

Shannon Hauf is a longtime ag-science and supplychain leader who has spent more than two decades inside the Bayer/Monsanto system translating research breakthroughs into dependable products for growers. She joined Monsanto in 2003 and has held senior roles across commercial strategy, R&D, crop technology, and seed production innovation, including global leadership of Bayer’s soybean technology portfolio before moving into broader product-supply responsibility. A Minnesota 4-H alum and advocate for the next generation of ag leaders, she was named to the National 4-H Council Board of Trustees in 2025 and is known as a champion for women in agriculture and science. Hauf holds a B.S. from Iowa State University and M.S./Ph.D. degrees from North Dakota State University, and she remains closely connected to production agriculture through her family’s farming roots and ongoing involvement.

By Brady Drake | provided by Shannon Hauf

hannon Hauf has lived a lot of agriculture.

She grew up on a southern Minnesota farm, went to Iowa State for undergrad, and then spent nearly six years in Fargo for graduate school. Today she’s based in St. Louis “where Midwest nice meets Southern hospitality,” she jokes, leading one of the most important pieces of Bayer Crop Science, which is product supply for North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

That job title can sound corporate. In practice, it means Hauf’s teams make sure farmers get the seed and crop protection products they need, when they need them, at the quality they expect, for the cost that keeps farms, and Bayer, competitive.

And it puts her right in the middle of one of the most aggressive innovation engines in global agriculture.

When Hauf talks about Bayer, she starts with what growers actually buy.

Bayer Crop Science’s core business still rests on two big pillars.

Seeds and traits come first. Bayer invests heavily in the crops that anchor farms in the U.S. and Canada, which are corn, soybeans, cotton, canola, and wheat. The work is both old-school and cutting-edge. It involves breeding better genetics, then pairing them with traits that solve real problems in the field.

If a farmer asks, 'How do I protect my field from insects without spraying an insecticide?' Bayer’s trait teams look at biotech routes that let the plant defend itself. If the question is, 'How do I keep my fields cleaner with fewer passes?' they develop herbicide tolerance traits, so growers can use specific chemistries safely and effectively. Disease resistance follows the same logic.

Crop protection is the second pillar. Seed alone isn’t a full-season plan. Farmers need herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides that match their genetics and their region. Bayer’s crop protection pipeline keeps pushing on both chemistry and biology—especially new “biological” products that use naturally occurring microbes to boost plant health or suppress disease.

Taken together, those two pillars explain why Bayer keeps landing at the center of big ag conversations.

Becaus of this, Hauf gets asked all the time why startups want to work with Bayer.

Her answer is their expertise, global reach, regulatory muscle, and scale.

In ag, a clever idea is only step one. The hard part is turning that idea into something farmers can actually use. Many solutions, especially biotech traits or crop protection tools, require years of regulatory approvals, field validation, and careful IP work. That process is expensive, and it’s where most startups hit a wall.

Bayer can carry that load. The company invests about $2.5–$2.6 billion every year into Crop Science R&D, one of the largest annual aginnovation budgets in the world.

It’s also global. About 40% of Bayer’s Crop Science business sits in the U.S., but the rest spans Latin America, Europe, and Asia. An innovation that works only in one corner of the world isn’t enough. Bayer has to build tools that travel, and it has the footprint to do that.

A good example of that pipeline momentum showed up recently when Bayer announced a new genetically engineered soybean technology in Brazil, Intacta 5+, with

tolerance to multiple herbicides and built-in caterpillar protection.

Hauf’s own lane is product supply, which how seed and crop protection products get produced, packaged, and delivered.

“When we deliver innovation and service that make life easier for farmers, the experience speaks for itself,” she said. “You just want to have a really great customer experience.”

That mindset is pushing Bayer to innovate from the inside out.

Over the last few years, Bayer has revamped its operating model through something called Dynamic Shared Ownership (DSO). Instead of decisions climbing a tall ladder of management, teams closer to the work are empowered to make big calls themselves. Bayer is shifting into self-managed teams, with fewer layers and more accountability.

Hauf sees the payoff in Fargo.

Bayer’s Asgrow soybean facility there is a real-world example of DSO. Hauf rembers a story about the Fargo plant team choosing to rework how they ran shifts and packaged product. Nobody in St. Louis dictated the change. A technician on site spotted a better way, tried it, and ended up saving serious money.

The trick, she says, is building a culture where it’s safe to test ideas. If something doesn’t work, you learn and move on. If it does, the whole system gets better.

That kind of innovation looks different from a new trait or molecule, but it matters just as much to growers. If Bayer can reduce waste, tighten delivery windows, and keep quality high, farmers feel it in real time.

Bayer is a global life-science company with a major footprint in agriculture through its Crop Science division. Bayer Crop Science develops and delivers seeds and traits for key row crops, a broad crop-protection portfolio (herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, and fast-growing biological solutions), and digital farming tools designed to help growers raise yields sustainably and manage risk in the field. Headquartered globally in Monheim, Germany, with North America’s Crop Science hub in St. Louis, Bayer combines deep R&D, regulatory expertise, and worldwide scale to turn new genetics, traits, and chemistries into practical products farmers can use season after season.

Artificial intelligence with really smart people gets a better result. It’s not one or the other. It’s the partnership.”

Bayer has been using AI long before AI was trendy.

In breeding, Bayer has spent nearly a decade pairing machine learning with its scientists to make faster, better decisions about germplasm selection. “Artificial intelligence with really smart people gets a better result,” she said. “It’s not one or the other. It’s the partnership.”

But the bigger surprise is how far AI has moved into everyday operations. Hauf says Bayer’s transportation and logistics systems are now driven through AI models, coordinating seed movement and seasonal supply across massive geographies.

On the customer side, Bayer has already rolled out agentic AI tools for sales teams and agronomists. The aim is pretty straightforward: help farmers get answers faster, sharpen recommendations, and make the whole customer experience feel more personal and useful.

Behind those tools sit partnerships with the major cloud and AI players— Google, Microsoft, and Amazon among them— because Bayer wants bestin-class systems in each slice of the stack, not a single one-size-fitsall platform.

Even with a global footprint, Hauf keeps circling back to home.

Bayer has long invested in the Northern Great Plains through R&D sites and product supply facilities. Fargo is a big part of that story. So is the broader pattern of what Bayer looks for next.

Hauf gave a quick history lesson to make the point.

In the mid-1990s, North Dakota planted less than 1 million acres of soybeans. Today, it’s roughly 7 million. Corn followed the same arc, rising to more than four million acres in a state where corn used to be hard to find. Bayer (and Monsanto before it) helped drive those shifts through genetics, traits, and investment.

Now Bayer is scanning for the next frontier.

One example is camelina, an oilseed crop Bayer sees as a future fit for the Northern Plains. The vision is a new market that routes camelina oil into sustainable aviation fuel, which another way for growers to diversify rotations while catching a new demand wave. Bayer has flagged biofuels and regenerative systems as major adjacent growth areas.

"There are plenty of companies doing good work in ag," Hauf said. She respects that, and Bayer partners with many of them. But she thinks Bayer’s advantage is the combination that’s hardest to replicate, which is deep science, regulatory and IP capability, global scale, and the ability to put real value on a grower’s operation.

By Brady Drake | J. Alan Paul Photography

farm’s toughest years rarely announce themselves all at once. Commodity prices soften.

Fertilizer costs more than it should. A labor shortage that won’t ease up. A trade war rages on. One season alone can stretch working capital thin. A few in a row can test the foundation of even a strong operation.

That’s why the value of a good ag lender changes in a tight economy. When margins are wide, credit is widely available. When margins narrow, the lender stops being a vendor and turns into a partner. A partner who is there for the long haul and can help producers manage risk, see around corners, and protect the long-term health of the farm.

Bank Forward has been in agriculture for nearly a century, and that history matters. The bank has financed multiple cycles.

They've seen good years, bad years, and everything in between.

Statistically, it’s now a $1 billion organization and employee-owned, with more than 40% of the bank held by its employee-owners. But the real proof of stability isn’t a number. It shows up in how a lender behaves when the cycle turns down. They stay consistent, present, and willing to work beside the producer instead of backing away.

That philosophy is clearest in the people doing the work. In the Red River Valley, Bank Forward is building an ag team designed not just to lend money, but to lend wisdom. Kent Anderson, Amanda Wolf, and Blaine Anderson each bring a different kind of expertise to the table. Together, they represent what a strong ag lender looks like right now because they are experienced, proactive, deeply communicative, and rooted in the realities of farm life.

VP of Ag Business Development Officer Blaine Anderson views a tight ag economy from two angles at once.

For producers, he sees his role as a coach and a steady hand. He helps them cut through noise, hold discipline on cash flow and working capital, and avoid shortterm fixes that could weaken the long game.

For the internal ag team, he emphasizes consistency. Cycles can tempt lenders to tighten too hard or loosen too fast. Blaine’s goal is to balance by protecting the bank from risk without choking out good operations that still deserve room to grow.

His lending principles are built for down cycles:

» Character first. Integrity and follow-through matter more than any spreadsheet.

» Cash-flow discipline. Profit matters, but liquidity keeps farms alive.

» Collateral as a backstop, not a crutch. Land values swing; the legacy must be protected.

» Partnership mindset. Farmer and bank are on the same team.

The signals he watches most closely are the ones that forecast stress early:

» input costs outrunning commodity prices

» weakening debt service coverage

» shrinking working capital over time

» inconsistent crop marketing or crop insurance use

To prevent overleverage, Blaine stress-tests every operation under multiple scenarios. Including lower yields, higher interest rates, and softer prices. If the plan can’t handle those shocks, growth needs to slow down. “Growth is great, but it must be paced with cash flow… and a sound plan,” he said.

Even in today’s constraints, he sees opportunity. Value-added agriculture and off-farm income can strengthen resilience. Precision agriculture can trim costs and improve efficiency. Succession planning matters as older generations begin handing off to younger producers who bring fresh approaches.

The difference between a strong lender-producer relationship and a transactional one is transparency. In strong relationships, the producer calls before they’re in trouble, not after. Blaine’s team stays proactive by monitoring cash flow trends, visiting farms regularly, and encouraging early conversations. Adjusting terms or restructuring early can prevent major damage later.

Ag Relationship Manager Amanda Wolf is the steady presence that keeps the day-to-day relationship strong. Amanda grew up on a farm, too. She understands the resilience and constant decision-making required to run an operation, and she brings more than 16 years of ag-specific banking experience into her role. That mix of personal ag roots and professional ag depth is exactly what farmers look for during stressful cycles.

On a practical level, Amanda supports the entire ag lending process. She is there for prospecting, origination, administration, and servicing. But her real value is that she makes sure producers never feel like they’re alone in the system.

“Day to day, my job is really about being a steady resource,” she said, both to the bankers and to their clients. Farmers rely heavily on the servicing side of her role, and even more on dependability. Partners know that when they call or text, someone is truly paying attention.

The concerns she’s hearing most consistently this year are direct and urgent:

» commodity prices tightening

» input costs staying higher than producers want

» storage shortages squeezing marketing options

In an environment like that, being proactive isn’t a nice extra. It’s the job. Amanda believes showing up matters beyond loan paperwork.

That might mean checking in during harvest, attending a bull sale, visiting after a hailstorm, or simply walking through account transactions together so the producer has real-time clarity.

“Farmers notice when you consistently show up in the small moments,” she said. Those moments build trust long before renewal time arrives.

When producers switch lenders, Amanda says they usually have the same story that they were missing communication and proactive planning. They didn’t feel understood. Their lender didn’t visit the operation. They didn’t get guidance until it was time to renew.

Bank Forward’s approach flips that. The bank prioritizes visibility and ongoing communication, and structures ag lending around farm reality—operating lines with seasonal flexibility, equipment and livestock loans built for production cycles, and programs for young or expanding producers, often in partnership with the Bank of North Dakota and USDA Farm Service Agency.

Amanda sees the bank’s long ag track record as a critical advantage right now. A lender can talk about commitment, but years of sticking with ag through multiple down cycles proves it. In a tight economy, producers don’t just need a financial product. They need a bank that won’t disappear when the cycle is rough.

Kent Anderson, VP Ag Business Development Officer, has spent about 30 years financing agriculture. He’s lived enough cycles to know that volatility isn’t an exception in ag—it’s the baseline.

He also knows lending isn’t only math. “As an ag lender, you wear many hats,” he said. He sees himself as an advisor, analyst, risk mitigator, coach, friend, and at times counselor. In a tight economy, those hats matter more than ever. Production decisions, capital purchases, cropping mix, marketing timing—the consequences of each choice get heavier when margins slim.

Kent came into the work with a personal understanding of what’s at stake. He grew up on a farm outside of Mayville, where he watched the effort his parents poured into the land to make a living and build a future. That experience shaped his style as a lender. He is open, believes in candid conversations, and understands that farming needs to be treated like the capital-intensive business it is.

Today, he sees producers facing a familiar but intense mix of pressures:

» depressed commodity prices

» rising inputs, especially fertilizer

» trade uncertainty and tariff risk

» wage pressure and tight labor supply

In response, his role has evolved. The banker’s job is still to help producers succeed, but the conversations now spend more time on expense management, cropping plans, and risk control. “We find ourselves spending more time discussing tactics to limit excess risk exposure,” Kent said.

When he evaluates whether Bank Forward can be a longterm partner for a producer, he starts with alignment. What does the producer want out of a lender? Are they looking for a transaction, or a relationship rooted in shared goals, honest feedback, and forward planning?

Then he looks at patterns in performance. Over decades, he’s learned to spot the difference between farms that drift with the market and farms that weather it:

» balance sheet strength

» disciplined working capital

» clear break-evens

» timely, accurate financial reporting

» marketing habits that lock in profit when it’s there

“Cash is king,” he said. Farms that protect liquidity can handle adversity without selling assets or restructuring their way out of trouble. The goal in good years is to build working capital; in tight years, to manage it wisely.

He’s especially blunt on taking advantage of opportunities because he’s watched too many operations lose margin simply through hesitation. “Don’t be afraid to take a profit when the market provides,” he tells clients.

What separates a great ag lender from an average one, especially now? Kent points to the ability to listen, connect resources, and say “no” when needed. “I never want to put a farmer into a position by knowingly letting them overextend themselves,” he said. A lender who protects the farmer from bad timing or emotional buying isn’t slowing them down; it's keeping the farm in position to keep going.

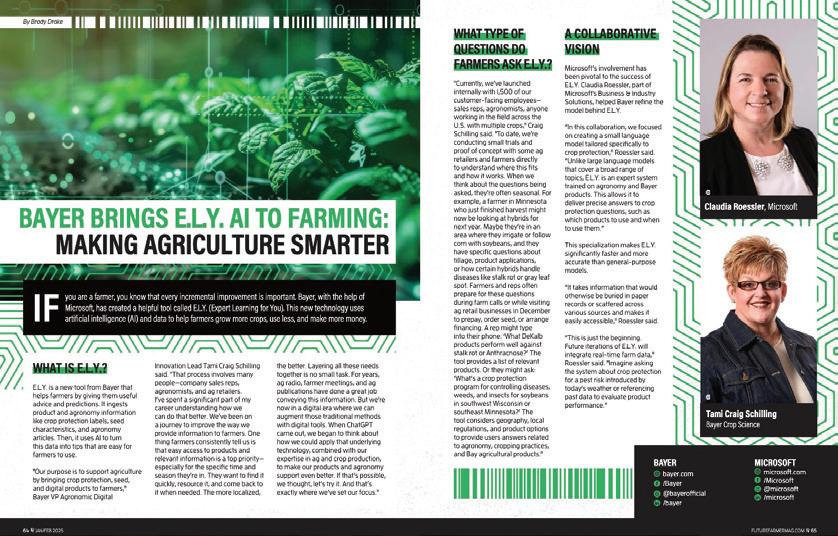

Bayer, partnering with Microsoft, introduced E.L.Y. (Expert Learning for You), an AIdriven agronomy assistant designed to help farmers make faster, more informed decisions. The tool pulls from Bayer’s deep library of crop protection labels, seed characteristics, and agronomy guidance, then turns that information into practical, easy-to-use recommendations.

According to Bayer VP Tami Craig Schilling, E.L.Y. grew out of a consistent message from farmers wanting quick, localized, season-specific access to trustworthy product and agronomy information. Instead of digging through paper labels, scattered resources, or waiting for a rep callback, farmers and field staff can ask questions on the spot and get tailored answers.

Microsoft helped Bayer refine E.L.Y. as a specialized small language model focused tightly on crop protection and agronomy. That narrow training makes it faster and more accurate for its job than general AI chatbots. Bayer has already rolled the tool

out internally to about 1,500 U.S. customerfacing employees and is running small trials with retailers and farmers. Future versions aim to connect to real-time farm and weather data for even more responsive recommendations.

IN THIS ISSUE, WE LOOKED AT BOTH EMERGING TECH AND EMERGING GROWERS!

Ryan Raguse comes from a sixth-generation farming family near Wheaton, Minnesota, and like many farm kids, he started young—driving tractors by 10 and hauling grain trucks by 13. Farming was always in his blood, even though he originally expected to build a life off-farm first. That detour became a major strength: Ryan studied business and entrepreneurship (St. Cloud State, then NDSU) and launched multiple ventures, including what became Bushel—an ag-tech platform headquartered in Fargo that helps farmers and grain elevators manage contracts, deliveries, and payments digitally.

His path shifted sharply in early 2023 when his father became sick and later passed away that summer. Ryan stepped in to finish that year’s harvest alongside strong community support, then fully took over farm management in the 2024 season. Though he had always helped on the farm, carrying full decision-making responsibility felt different, pushing him to research, question, and refine every choice.

Now Ryan balances two demanding roles: farmer and Bushel CIO. He argues that dual careers are becoming normal in agriculture, and technology makes that balance possible—not just high-end equipment, but everyday digital systems that let farmers manage real tasks remotely. His farm approach blends respect for tradition with an entrepreneurial, problem-solving mindset built from years of working with limited resources in both farming and startups. Looking forward, Ryan is focused on sustainability in every sense—financial survival, soil health, and long-term land stewardship—including exploring organic crops and strip-till practices that align with both modern pressures and his father’s vision.

Logan Rayner has never wavered on what he wanted to do: farm. Raised on his family’s operation near Finley, North Dakota, he grew up immersed in agriculture, riding along with employees, running tractors early, and absorbing the rhythm of farm life. Even college didn’t pull him far away. He chose the University of Minnesota Crookston for its ag program and because it kept him close enough to drive home every weekend to work.

Now 23 and freshly graduated (fall 2024), Logan is back on the farm full-time with about 1,000 acres of his own to manage. His growth into leadership came gradually, guided by a father who gave him room to learn by doing. In recent years he’s taken over the “health side” of the farm—equipment maintenance, repairs, and year-round operational readiness—while shifting more into planning and farm management.

Logan is also carving out new income through drain tiling. What started as a tool his dad bought for their own fields turned into a side business when neighboring farms asked for help. Logan now runs tiling projects when time allows, using a young crew willing to do the heavy manual labor. Alongside that, he pushes innovation through test plots with agronomists and seed suppliers, believing that trials are essential to staying competitive. He’s realistic about the challenges ahead—automation, costs, sustainability pressures—but stays optimistic, rooted in the support of his farming community and the legacy he’s preparing to carry forward.

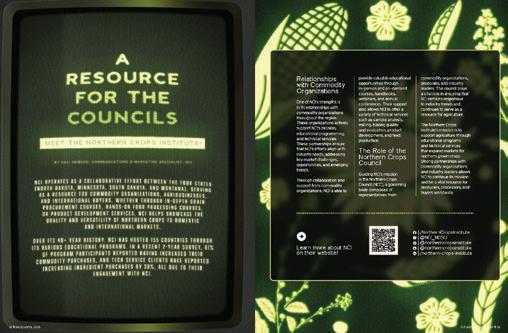

NCI is a Fargo-based, four-state collaboration (MN, ND, SD, MT) built to expand markets for northern-grown crops. It operates as an international meeting, training, and technical services center, bringing together global buyers, traders, processors, and crop experts. Over 40+ years it has hosted participants from 155 countries and shows measurable market impact through increased commodity purchasing after programs. The Northern Crops Council (NCC) is the governing body that guides NCI’s mission and keeps it aligned with industry needs.

MCGA is a grassroots, membership-based advocacy group representing Minnesota’s 24,000 corn farmers, with about 7,000 members. It works in legislative/regulatory arenas, so it cannot use checkoff dollars. MCR&PC is the separate, checkoff-funded body that invests in research, education, and market development to grow demand and improve production. Together, they cover both policy voice and innovation funding.

MSR&PC is a farmer-led, checkoff-funded council investing in research, market development, and education to improve profitability for Minnesota soybean farmers. MSGA is the membership-based policy/advocacy organization, separate because checkoff dollars can’t be used for lobbying. The checkoff is assessed as a small percent of soybean sales, split between state and national boards.

MWRPC is a producer-elected board that directs Minnesota wheat checkoff dollars into research, education, and promotion. It’s built to increase profitability and sustainability through innovation and market development. It operates with daily collaboration with researchers and monthly grant review, plus annual reporting. The council is structured around nine districts with elected wheat farmers.

NDBC is a state agency created in 1983 to strengthen North Dakota’s barley industry. It invests barley checkoff dollars into research, market development, and education. The council is led by five elected barley growers representing major barley districts. Checkoff applies per bushel sold/ delivered, excluding barley used as livestock feed by the grower.

NDWC is a 1959-created state agency that promotes and expands trade for North Dakota wheat. It invests wheat checkoff dollars into research, market development, and education to support grower profitability and longterm sustainability. Governance includes six elected wheat producers plus one governor-appointed member, representing districts across ND.

NDSC is a 1985-created state agency that manages soybean checkoff dollars for research, marketing, and education. It’s farmer-led, with 12 elected growers representing regions across ND. NDSGA is the separate membership-based advocacy organization handling policy and legislation since checkoff funds can’t be used for lobbying.

NDOC is a state agency promoting multiple oilseed crops in North Dakota — sunflower, safflower, canola/rapeseed, crambe, and flax. It invests checkoff dollars into research, education, and market development to improve profitability and expand demand. The council has 14 representatives, with a mix of elected growers and appointed members tied to specific crops.

SCAN HERE TO READ THE REST OF THE STORIES

IN THIS ISSUE, WE SET OUT TO MEET THE COUNCILS!

NDDPLC is a state agency formed in 1997 to grow ND’s pulse crop industry (peas, lentils, chickpeas, fava beans, lupins). It directs checkoff dollars into research, market development, education, and government initiatives. It operates under the broader Northern Pulse Growers Association (NPGA), which serves as the policy/outreach voice. The pulse checkoff is a 1% assessment and is framed as delivering high ROI.

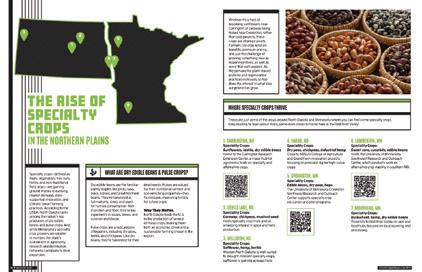

North Dakota and western Minnesota are seeing a quiet but real shift: alongside traditional wheat, corn, and soybeans, more farmers are adding specialty crops like edible beans, buckwheat, sunflowers, caraway, hemp, and even grapes. These crops are showing up not as side hobbies, but as strategic rotation and market plays. The movement is being pushed by demand for plant-based proteins, regenerative agriculture, and state-supported research/ innovation. North Dakota stands out nationally for dry edible beans and pulse crops, while Minnesota’s growth is smaller but fueled by research and distribution investments.

• Specialty crops are gaining acreage in ND and western MN.

• They include non-traditional field crops plus fruits/veg/nuts/herbs.

• ND is a top U.S. producer of dry edible beans and pulse crops

• MN has fewer growers but is growing via research + distribution networks

• Farmers are motivated by rotation benefits, premium pricing, learning/ innovation, and market demand

• Rising demand for plant-based proteins + regenerative practices is accelerating interest.

Dry edible beans (pinto, navy, black, kidney, Great Northern) are harvested mature and dried for food. Pulse crops are legumes like dry peas, lentils, and chickpeas—also harvested for dried seeds. Beyond nutrition, pulses matter agronomically because they

fix nitrogen and improve soil fertility. North Dakota leads U.S. production of several of these crops, making them both profitable and sustainable for the region.

• Dry beans = mature, dried food beans (pinto, navy, black, kidney, etc.).

• Pulses = dry peas, lentils, chickpeas (legume subcategory).

• Pulses fix nitrogen, improving soil for future crops.

• ND is a national leader in these crops, so they’re economic + soil-health drivers

Specialty crops cluster where climate, infrastructure, and research align. ND hubs like Carrington, Devils Lake, Williston, and Fargo are tied to crop trials and droughttolerant or high-value alternatives. In MN, Crookston, Lamberton, and Moorhead connect to university outreach centers, coops, and food hubs, supporting beans, peas, hops, buckwheat, hemp, and more.

• Carrington = sunflowers, lentils, edible beans + a major NDSU research center.

• Devils Lake = caraway, chickpeas, mustard with spice/herb momentum.

• Williston = safflower, hemp, lentils in drought-tolerant western ND.

• Fargo = peas, chickpeas, hemp near NDSU + Grand Farm precision ag work.

• Crookston = beans, peas, hops supported by UMN NWROC.

• Lamberton = sweet corn, cucurbits, beans via UMN SWROC.

• Moorhead = buckwheat, hemp, beans tied to Red River Valley processing.

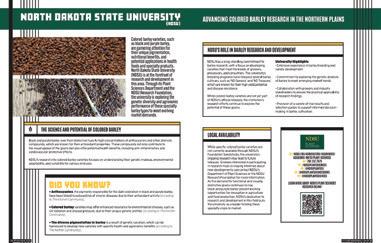

Colored barley (black/purple) is gaining attention for its anthocyanin-rich pigmentation, antioxidant potential, and appeal for health foods. NDSU is leading research into the genetics, agronomics, and end-use potential of these varieties. While not yet in official releases, the work builds on NDSU’s proven barley-breeding track record and could open new specialty-grain markets.

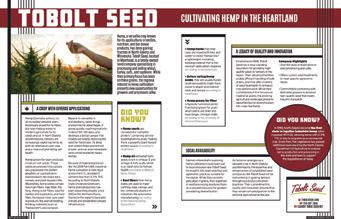

Hemp is re-emerging as a serious Northern Plains specialty crop because it can be grown for grain and fiber, both with expanding end markets. Tobolt Seed, a Moorheadbased family seed company known for traditional grains, is positioned as a potential resource for local hemp growers because of its processing expertise and infrastructure. Hemp offers diverse product pathways (oil, protein, textiles, bioplastics, hempcrete), plus environmental benefits like weed suppression and soil protection. ND has a long regulatory history with hemp, and regional acreage has been rising steadily.

Sunflowers and millet are growing specialty-crop bright spots in the region, and Red River Commodities (Fargo, founded 1973) is a major reason why. The company processes sunflower seeds into food ingredients and consumer products worldwide — including SunButter — and also cleans/hulls millet for food-grade and gluten-free markets. Their long processing legacy, tech investment, and full-utilization approach show how specialty crops become durable regional industries.

4e Winery in Mapleton shows that grapes can be a viable specialty crop even in ND’s climate — if they’re coldhardy. Greg and Lisa Cook grow and process varieties like Frontenac, Marquette, Petite Pearl, La Crescent, and Brianna, plus local fruit wines using rhubarb and haskap berries. The winery combines agriculture, science, and hospitality, producing about 12,000 bottles a year and serving as a model for diversified, value-added farming.

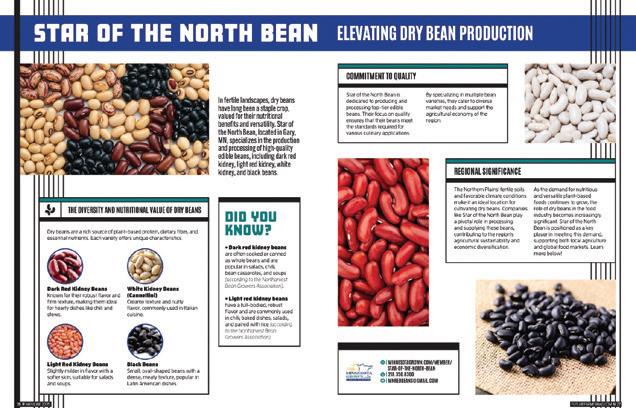

Dry edible beans are a cornerstone specialty crop in the Northern Plains. Star of the North Bean (Gary, MN) grows and processes multiple varieties — dark red kidney, light red kidney, cannellini, black beans — each tied to different culinary markets. The company’s role underscores how regional soils/climate plus processing infrastructure turn beans into a reliable, high-value rotation crop.

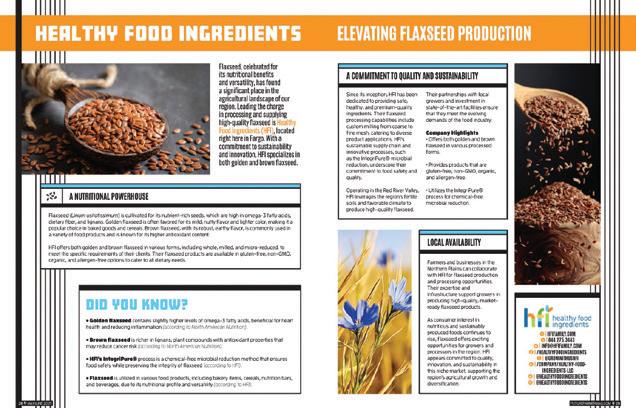

Flax is thriving as a specialty crop because of its nutritional profile and flexible food uses. HFI in Fargo processes golden and brown flax into multiple formats (whole/milled/micro-reduced) and offers tailored, food-safe products (gluten-free, organic, non-GMO). Their IntegriPure® microbial reduction method shows how processing innovation builds trust and scale in specialty markets.

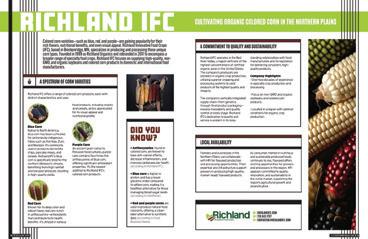

Colored corn (blue/red/purple) is growing in demand for flavor, nutrition, and natural pigment uses. Richland Innovative Food Crops (Breckenridge, MN) specializes in organic/non-GMO soy and colored corn for domestic and global food manufacturers. Their vertically integrated model controls genetics through packaging, giving traceability and consistent quality — key in specialty markets.

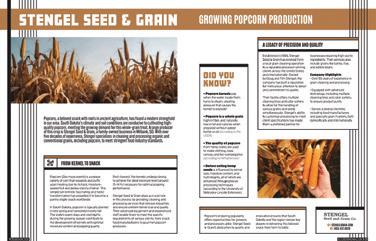

Popcorn is a specialty corn with unique processing needs, and South Dakota’s climate supports high popping quality. Stengel Seed & Grain (Milbank, SD, founded 1956) cleans and processes organic and conventional popcorn, ensuring moisture and kernel uniformity for food manufacturers and gourmet markets. Their equipment and customization highlight how specialty grains depend on precision postharvest handling.

Buckwheat, a fast-maturing, cool-climate, gluten-free pseudocereal, fits Northern Plains rotations well. Minn-Dak Growers (East Grand Forks, MN, founded 1967) is North America’s largest buckwheat processor, linking regional growers to major global markets, especially Japan for soba noodles. Their vertically integrated milling and quality systems stabilize buckwheat as a profitable specialty option.

What we learned

• Buckwheat is gluten-free, nutrient-dense, and in global demand.

• It’s a short-season crop ideal for cool climates and marginal soils.

• Offers agronomic perks: weed suppression, biodiversity/pollinator support

• Minn-Dak Growers is North America’s largest buckwheat miller.

• They connect growers to international markets, especially Japan.

• Their systems help optimize harvest timing + consistent food-grade quality

IN THIS ISSUE, WE LEARNED ABOUT THE RISE OF SPECIALTY CROPS IN OUR REGION! SCAN HERE TO READ THE REST OF THE STORIES

Grand Farm’s cross-border AgTech showcase returned to Fargo in 2025, and the through-line was clear: Canada isn’t just watching Midwest agriculture evolve— it’s building alongside it. Facilitated by the Consulate General of Canada, the event brought a cohort of Canadian startups into the Northern Plains to meet growers, researchers, and ag leaders, reinforcing Fargo’s role as a proving ground for realworld innovation.

At the center of the week was Consul General Beth Richardson, who oversees Canada’s relationship with North Dakota, Minnesota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Iowa. With a diplomatic career spanning Seoul, London, and Moscow—and a formative upbringing in rural Alberta— Richardson bridges global trade thinking with prairie practicality. Her role is both economic and strategic: build the pipelines that let Canadian companies expand into U.S. agriculture while strengthening a trade relationship that already runs deep.

Richardson explains that Canada’s presence in Fargo flows through the Canadian Technology Accelerator (CTA) program, which the Consulate has run annually since partnering with Grand Farm in 2021. Roughly ten export-ready startups are selected through a competitive process led by the Trade Commissioner Service. Their CTA cohort spends six months making market connections across North America. Fargo is the final stop—after World AgriTech in San Francisco and a Mexico visit—because

it offers something coastal hubs can’t: immersion in a collaborative, farm-adjacent ecosystem where pilots become real acreage.

That pilot-to-scale path is already proving itself. Richardson points to companies like Fair, which began with a Grand Farm pilot in 2020 and moved into a five-acre NDSU field trial in 2024, using ultra-high-pressure water-jet tech for no-till nutrient placement. Another, eLf Garden, brought biosecurity software from Canadian hog and poultry systems into the U.S., then established a Midwest subsidiary once demand aligned. The pattern is consistent: Fargo isn’t just a showcase—it’s a gateway into the U.S. market.

Richardson also makes a direct appeal to producers: this isn’t a closed loop between governments and startups. Growers can engage through trials, early adoption, and outreach to the Consulate’s ag trade commissioners, who match Canadian innovation with U.S. farm needs. For producers, the takeaway is simple—if a Canadian tool fits your operation, the Consulate wants that connection to happen.

Trade, though, isn’t friction-free. Richardson is blunt about tariffs: they’re hurting both sides. Between North Dakota and Minnesota alone, about $3 billion in ag trade crosses the border annually; CanadaU.S. agricultural trade overall sits around $75 billion. Most of that trade is inputs, not finished products. When tariffs inflate those

costs, margins shrink on both sides, and the eventual cost rolls to consumers. Her message is practical: agriculture works better when cross-border supply chains stay open and predictable.

Alongside trade realities, Richardson zooms out to what she sees as the bigger story in agriculture: innovation is colliding with clean tech, circular economy thinking, and renewable energy. Byproducts once treated as waste are becoming inputs for bioenergy, soil amendment, and regenerative systems—improving soil health, reducing input intensity, and creating new markets at the same time.

The companies in the CTA cohort embody that shift. Sultech Global Innovation Corp is turning recovered sulphur

from oil and gas processing into micronized fertilizers designed to oxidize quickly and cut emissions. Picketa Systems is rebuilding tissue analysis around speed, putting real-time nutrient scanning into agronomists’ hands so fertility decisions can happen in-season. Upside Robotics is targeting compaction and nitrogen waste by replacing heavy tractors with lightweight autonomous robots that micro-apply fertilizer through the year.

Put together, the week wasn’t about futuristic promises. It was about practical systems solving current problems— nutrient timing, soil health, fertilizer cost, labor pressure— and about a Prairie-to-Prairie partnership that keeps Fargo one of the most relevant agtech checkpoints in North America.

FARRMS (Foundation for Agricultural and Rural Resources Management and Sustainability) is a North Dakota nonprofit that has spent 25 years helping beginning farmers and ranchers build sustainable, locally focused farm businesses. Led by Executive Director Stephanie Blumhagen, the organization serves people in their first 10 years of farming, emphasizing “people, planet, and profit” — meaning community impact, environmental stewardship, and realistic business planning all matter equally.

FARRMS supports a wide range of small-scale and diversified producers across the state. Many grow under 10 acres, including urban and backyard farmers, and they sell through farmers markets, CSAs, food co-ops, and farmto-school programs. Products range from vegetables, flowers, and heirloom grains to microgreens, mushrooms, honey, and small livestock. Beyond teaching skills, FARRMS prioritizes building a farmer community in a state where many growers feel isolated. Their programs intentionally pair new farmers with mentors, bring producers together through field days and farm tours, and amplify farmer stories through directories, calendars, and blogs.

Demand for local and organic food is rising faster than supply in North Dakota, and FARRMS positions that gap as a major opportunity for new growers — especially in rural areas facing grocery store loss and food deserts. At the same time, federal grant cuts have hit local-food nonprofits, so FARRMS is fundraising $25,000 by June 2026 to keep programs strong and funding flowing directly to farmers through loans, grants, scholarships, stipends, and travel support.

SCAN HERE TO READ THE REST OF THE STORIES

IN THIS ISSUE, WE HIGHLIGHT A SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP WITH OUR FRIENDS UP NORTH!

Farm Rescue began in 2005 when Bill Gross, a pilot from Cleveland, North Dakota, saw a gap opening in rural life. The old expectation — that neighbors would roll in with combines or extra hands when a farmer got sick or hurt — was still the ideal, but harder to pull off as farms grew larger and rural populations shrank. Gross built Farm Rescue to formalize that tradition so families wouldn’t lose a season (or their livelihood) just because life happened.

Twenty years later, it’s grown into a multistate nonprofit that has helped more than 1,220 farm and ranch families across ten states, powered by over 2,500 volunteers. While North Dakota remains home base and a state where most people already know the name, Farm Rescue now operates across much of the Midwest and Great Plains — including Minnesota, South Dakota, Iowa, Kansas, Illinois, and others — with a continued push into regions where awareness is still thin.

The mission is straightforward: step in during a crisis to keep a farm running. If a producer is sidelined by cancer, a heart attack, injury, wildfire, or another disaster, Farm Rescue brings volunteers and equipment in at no cost so planting, harvesting, or haying still gets done.

Executive Director Tim Sullivan emphasizes they’re focused on small-to-mid-sized operations, not giant farms with multiple backup crews. To stretch resources, they cap help at 1,000 acres per season per family — enough to save a farm’s year without

overextending volunteer and equipment capacity.

Speed is one of the organization’s defining traits. Requests arrive constantly, sometimes multiple in a day. Families apply through a short online form under “Family in Crisis.” Farm Rescue staff quickly vet the case, verify details (including medical documentation when needed), visit the farm to map acreage, then dispatch crews. Turnaround can be just a couple days — fast enough to matter in tight seasonal windows.

Volunteers are the backbone. Farm Rescue maintains a registry of more than 300 active volunteers, typically deploying around 250 in a busy year. They come from all over the country. Some run combines, tractors, balers, or trucks; others serve as support crew — bringing meals, swapping drivers, helping with logistics, staffing booths at events, or simply being present with stressed families. The work is intense: dual day-night shifts, late harvest runs, and constant coordination — but testimonials show how deeply it lands for both the families and the volunteers.

The article also highlights a newer layer to Farm Rescue’s work: mental health. Agricultural crises aren’t always visible injuries. Stress, burnout, or emotional collapse can be just as disabling. Farm Rescue’s role isn’t to provide counseling directly, but to ease immediate workload pressure and connect families to longerterm support through partners like NDSU

Extension, AgrAbility, and national mental health networks. In some cases, families say the help went beyond fieldwork — it included listening, presence, and a bridge to resources they didn’t know existed.

Financially, the organization runs lean at about $4.5 million annually, covering fuel, hauling equipment, staff coordination, outreach, and logistics. While in-kind and corporate partnerships (like John Deere) are essential, fundraising remains the biggest challenge. The work can’t happen without money to move people and machines.

Giving Hearts Day has become a major lifeline. Farm Rescue has participated since 2015, but 2024 was a breakout year: with a $500,000 matching gift and a $1 million goal,

they raised $1.3 million in a single day, ranking third among hundreds of charities. Sullivan says the deeper meaning wasn’t rank — it was the public vote of confidence that Farm Rescue’s mission matters and works.

The piece ends by reinforcing why Farm Rescue is still necessary in modern agriculture. Farms are bigger, equipment is more complex, seasonal windows are tighter, and rural isolation is real. Missing a planting or harvest season can mean losing a farm that’s been held for generations. In that landscape, Farm Rescue isn’t just help — it’s a lifeline that keeps families on the land. Looking forward, the organization aims to expand name recognition in more states, build volunteer ranks, and keep responding fast when urgency hits.

QA Farmer launched at the Big Iron Farm Show with a simple promise: stop making farmers bounce between a pile of apps just to answer basic daily questions. The pitch isn’t that it invents brand-new tools. It’s that it pulls the essentials into one farmer-first dashboard — actionable weather, local elevator bids, bin inventory, and (soon) a direct connection to agronomists using FarmQA.

The opening frames the pain point clearly: every morning comes with rapid-fire decisions — Can I spray today? What’s the basis doing? What’s left in the bins? Did someone check that field? Until now, those answers lived in separate places. QA Farmer compresses them into one workflow, shrinking the lag between question and decision during the most margin-sensitive parts of the year, especially harvest.

The article lays out why timing matters. Harvest (and spraying windows) forces fast calls, where a two-hour weather shift, a small basis move, or a sudden storm can swing real money. QA Farmer is built to reduce that friction.

SCAN HERE TO READ THE REST OF THE STORIES

IN THIS ISSUE, WE PROFILE A NONPROFIT THAT'S HELPING WHEN IT MATTERS MOST.