Infrastructure Adaptation for Emerging Economies

Scaling sustainable

solutions

Foreword from the President

Catherine Karakatsanis M.E.Sc P.Eng ICD.D FEC FCAE. LL.D President, FIDIC

As FIDIC launches its first State of the World report for 2025, we do so at a time of profound challenge and unprecedented opportunity for the infrastructure sector. This report, Infrastructure Adaptation for Emerging Economies –Scaling Sustainable Solutions, speaks to the urgency of our moment and the collective responsibility we share to forge pathways of equity, resilience and climate justice.

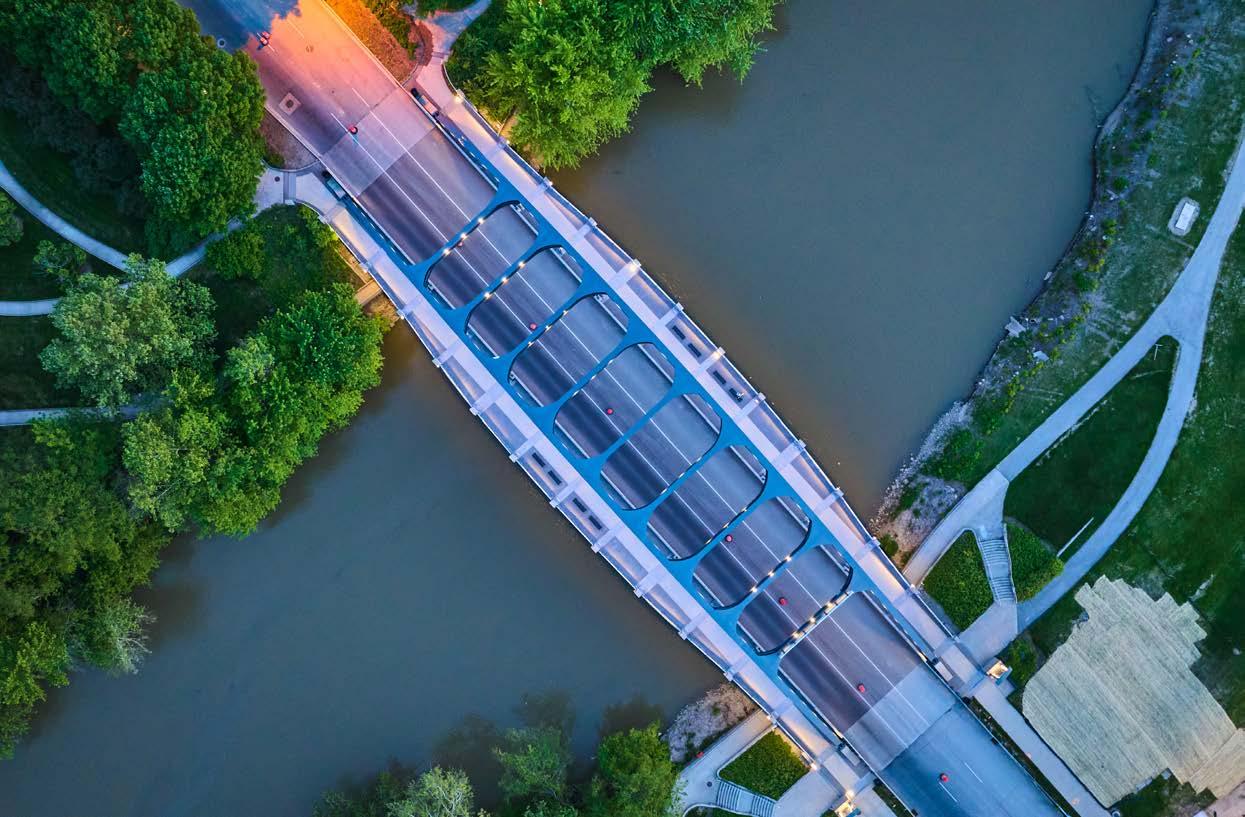

Infrastructure has always been the backbone of societies the bridges that connect communities, the water systems that sustain life and the energy networks that power progress. Yet, in too many parts of the world, these lifelines remain out of reach for millions. The global infrastructure gap is not merely a statistic; it is a daily reality that defines lives, constrains opportunity and deepens inequality.

Emerging economies stand at the forefront of this challenge and of the solutions. With rapid urbanisation, dynamic populations and unique environmental contexts, these regions are poised to lead a new era of infrastructure development, one that is inclusive, adaptive and locally grounded. From Sub-Saharan Africa to Southeast Asia, from Latin America to the Middle East, the ingenuity and determination of these communities offer hope and a clear direction forward.

This report reflects FIDIC’s enduring commitment to advancing engineering excellence and to championing the transformative potential of infrastructure. It draws upon the collective insights of our global community including engineers, policymakers, financiers and community leaders – who are working every day to deliver systems that are not only technically robust, but also socially just and environmentally sustainable.

As we navigate this pivotal decade, we are called to rethink the very principles that underpin infrastructure development. The SDGs, the Paris Agreement and the rapidly evolving climate finance landscape provide a roadmap, but it is up to us to translate these global frameworks into practical, scalable action on the ground. The pages that follow explore how that action can be realised, through inclusive partnerships, innovative technologies and capacity building that empowers local voices and expertise.

The 2025 FIDIC Global Infrastructure Conference in Cape Town and COP30 in Brazil later this year will underscore the critical role of infrastructure in addressing climate adaptation, driving economic inclusion and fostering social equity. These gatherings, along with the work of FIDIC’s global member associations and partners worldwide, remind us that solutions are already taking shape and that scaling them is both our challenge and our opportunity.

In this spirit, I invite you to explore the findings and insights of this report. Let it serve not only as a reflection of our shared progress and the road still ahead, but also as a call to action to reimagine infrastructure as a force for dignity, justice and long-term resilience in every community it touches.

Together, we can build a future where no one is left behind and where infrastructure is a catalyst for equitable and sustainable development.

This FIDIC State of the World report, Infrastructure Adaptation for Emerging Economies: Scaling Sustainable Solutions, explores the urgent need and the transformative opportunities to build infrastructure systems that are not only climate-resilient and technically sound, but also inclusive of society and its needs regionally, nationally and locally.

Nearly one billion people still lack access to electricity, two billion live without safe water and over half the world’s population relies on unreliable transport networks (World Bank, 2023)1. These figures are not just statistics, they shape lives, limit opportunities and amplify vulnerabilities in communities across the global south. As climate change, rapid urbanisation and socio-economic transitions converge, the infrastructure gap in emerging economies has become both a crisis and a catalyst for change.

This report is designed as both an informative and action-oriented resource for policymakers, infrastructure professionals, investors, and development practitioners seeking to navigate the complexities of delivering climate-resilient and inclusive infrastructure in emerging economies. It aims to equip decision-makers with actionable insights, backed by global best practices, case studies, and policy recommendations, ensuring that infrastructure is not viewed merely as a technical or financial endeavour but as a catalyst for social equity, climate resilience and economic transformation. Governments, asset owners, private sector leaders and multilateral institutions play a pivotal role in advancing this shift—through policy alignment, investment strategies and governance frameworks that centre equity and sustainability. By fostering collaboration across these sectors, this report serves as a roadmap for translating ambition into impact, ensuring that infrastructure solutions deliver meaningful, measurable outcomes for communities worldwide.

Infrastructure is not just a physical asset—it is a force that shapes societies, economies, and environmental outcomes. At its best, infrastructure unlocks opportunity and inclusion, providing access to essential services, driving economic growth, and fostering resilience. Yet, when poorly planned or unequally distributed, it can entrench disparities, reinforcing cycles of social and economic exclusion while deepening environmental vulnerabilities. This dual role makes infrastructure one of the most powerful levers for equitable and sustainable development—but only when designed with intentionality, inclusivity and climate consciousness.

Key findings

Emerging economies occupy a crucial position in the infrastructure landscape. Dynamic populations, rapid urbanisation and distinctive environmental contexts mean these regions are both uniquely vulnerable to infrastructure gaps and uniquely positioned to pioneer climate-smart, inclusive solutions.

Climate change acts as a powerful amplifier, intensifying pressures from heatwaves, droughts, flooding and rising seas and demands that infrastructure systems are not only technically robust but also adaptive, resilient and future-ready. This evolving context underscores the importance of moving beyond technical solutions to address persistent social inequities, particularly in informal urban growth areas and among marginalised communities who are often excluded from decision-making processes.

At the same time, the current moment presents a rare window of global opportunity to capitalise and create the urgent shift needed towards equitable, climate-resilient infrastructure. To meet this moment, innovative financing and technology which include blended finance, climate-linked bonds, modular construction, decentralised energy systems and nature-based solutions are redefining the future of infrastructure, placing people and communities at the centre of sustainable development.

Major insights for policymakers, engineers and investors

For policymakers, the report underscores that climate adaptation and social equity cannot be afterthoughts; they must be foundational principles, woven into every stage of planning, regulation and investment. Such principles are currently under greater scrutiny, with conditions such as high levels of public debt also causing challenges. It is important, however, that as a sector we remain objective even when faced with increasing uncertainty.

It will be important to continue aligning policies, actions and delivery with national adaptation plans and the Sustainable Development Goals. It’s also worth remembering that the SDGs set the ambition for 2030, not 2050 as many net-zero targets do. Engineers will be called upon to go beyond technical roles, stepping up as champions of inclusive design and climate resilience and as trusted facilitators of solutions that truly reflect community and societal needs and knowledge.

Investors and multilateral development banks are likewise urged to reframe how they approach risk and investment strategies, ensuring that capital is accessible to the regions and communities that need it most and that projects deliver tangible social and climate benefits. Traditional models which consider economic benefits per head of population for example are unlikely to deliver for remote or distant communities.

Ultimately, this moment demands not only ambition but genuine collaboration and robust collaboration between the public and private sectors, civil society and international institutions, working together to harmonise standards, share best practices and capacity building and scale impact across emerging

Summary of recommendations

For Financial Institutions and Investors:

• Harness innovative finance instruments, such as blended finance, guarantees and municipal green bonds, to unlock investment for climate-resilient infrastructure – ensuring alignment with social and environmental goals.

• Leverage global forums to spotlight the financing needs and opportunities in the global south.

For Engineers and Technical Experts:

• Integrate digital and AI tools and nature-based solutions as core components of climate-resilient infrastructure strategies – including modular construction, smart monitoring systems and green infrastructure.

• Prioritise monitoring, learning and accountability with robust resilience metrics and participatory evaluation frameworks to ensure projects deliver both social and climate outcomes.

For Policymakers and Community Leaders:

• Reframe infrastructure as a tool for climate justice and community resilience –moving beyond technical delivery to address social and environmental equity.

• Embed local knowledge and inclusive planning by centring community voices in project design and delivery, making solutions socially relevant and equitable.

• Bridge capacity gaps through technical training, institutional reforms and governance alignment with national climate adaptation plans and the Sustainable Development Goals.

Bridge capacity gaps and align with climate adaptation:

• Invest in technical training, institutional capacity and governance reforms to enable locally driven climate-resilient solutions.

Harness innovative finance and partnerships:

• Expand the use of blended finance, guarantees and municipal green bonds to unlock investment – and ensure these instruments align with social and climate goals.

Integrate digital tools and nature-based solutions:

• Mainstream modular construction, smart monitoring systems and nature-positive infrastructure as central components of resilient infrastructure strategies.

Prioritise monitoring, learning and accountability:

• Establish robust resilience metrics and participatory evaluation frameworks to ensure that projects deliver both social and climate outcomes.

Leverage global forums to drive change:

• Use the momentum of the 2025 FIDIC Global Infrastructure Conference in Cape Town and COP30 to champion the needs and leadership of the global south, building alliances and accelerating practical action.

This report is more than an analysis of today’s infrastructure gaps, it also serves as a call for transformation.

The path forward demands that engineers, policymakers, investors and communities reimagine infrastructure as a catalyst for a more equitable and climate-resilient society.

/The global urgency

The global urgency /

The growing infrastructure gap in emerging economies

The infrastructure gap in emerging economies has become one of the defining challenges – and opportunities – of our era. Nearly one billion people worldwide still lack access to electricity, two billion are without safe water and over half the world’s population does not have reliable transport networks to connect them to economic opportunity and essential services (World Bank, 2023)1. These figures are not merely statistics, they represent the daily realities of communities whose potential is constrained by systems that are incomplete, under-resourced or increasingly overwhelmed.

This gap is both a crisis and a catalyst. It is a crisis because it entrenches social and economic disparities, making it harder for emerging economies to participate in global trade, grow economies, provide the jobs and skills needed to meet development goals and reduce poverty. But it is also a catalyst because the next decade could offer an unprecedented window of opportunity to close these gaps, intelligently, inclusively and sustainably.

1 billion 2 billion Half of the world

Emerging economies are at the epicentre of this challenge. Many are experiencing rapid urbanisation, with cities expanding at an astonishing pace. The UN projects that 90% of global urban growth by 2050 will occur in Africa and Asia, adding nearly 2.5 billion people to urban areas (United Nations, 2018)3. This surge creates enormous demand for new and upgraded infrastructure. Yet, if not managed thoughtfully, it also risks deepening spatial inequality, straining natural resources and reinforcing vulnerabilities to climate change.

Climate change further amplifies these stakes. From flooding in Jakarta to prolonged droughts in the Horn of Africa, climate shocks are testing the limits of existing infrastructure and disproportionately impacting the most vulnerable communities. As infrastructure systems face growing stresses, so too do the people who depend on them for basic needs and livelihoods.

At FIDIC, we see these pressures not as a call for incremental change, but as a mandate for transformative action. Infrastructure is not merely the physical backbone of society, it is a vehicle for realising human rights, advancing climate justice and fostering equitable development. Bridging these gaps will require more than funding. It will demand new partnerships that amplify local voices, innovative technologies that adapt to local contexts and an unwavering commitment to social and environmental inclusion.

This report is a call to the global community to invest in infrastructure that is not only efficient and resilient, but also just and future-ready. It is also an invitation to emerging economies themselves to champion solutions that reflect local priorities, leverage local knowledge and strengthen local capacity.

Rapid urbanisation, population growth, and climate pressures

Rapid urbanisation and population growth are reshaping the landscape of infrastructure needs in emerging economies. Urban populations are projected to double by 2050 across much of Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, driven by a combination of demographic momentum and rural-to-urban migration (UN-Habitat, 2022)4. These dynamics, while promising in terms of economic opportunity and innovation, pose significant challenges for inclusive and sustainable urban development.

Cities in emerging economies are becoming magnets for investment, culture and connectivity, yet many remain unprepared for the sheer scale of growth ahead. Urban centres are increasingly marked by informality and spatial inequality, with one in three urban residents in the global south living in slums or informal settlements (World Bank, 2023)5. These communities often lack basic services and are at heightened risk of climate impacts, creating a dual challenge of upgrading existing infrastructure and building new systems that meet the needs of expanding populations.

Simultaneously, climate change acts as a powerful risk multiplier. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns and intensifying storms are already testing the limits of urban resilience. In South Asia, for example, coastal cities like Mumbai and Dhaka face the threat of more frequent flooding and storm surges, putting millions at risk of displacement (IPCC, 2022)6. In Sub-Saharan Africa, prolonged droughts in rapidly growing urban corridors are straining already limited water and energy systems, while heatwaves are amplifying public health risks in densely populated informal settlements (African Development Bank, 2022)7

At the heart of these intertwined challenges lies a clear imperative – infrastructure systems must be designed and delivered to respond to demographic pressures, accommodate rapid urban expansion and withstand the intensifying climate shocks that threaten to reverse hard-won development gains. This means going beyond traditional models of infrastructure delivery to embrace solutions that are adaptive, inclusive and climate-resilient.

Simultaneously, climate change acts as a powerful risk multiplier. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns and intensifying storms are already testing the limits of urban resilience.

The global urgency /

Why this report now? Context and opportunity

The timing of this report is not incidental. The coming years present a unique convergence of global milestones and policy dialogues that will shape the trajectory of infrastructure development in emerging economies for decades to come.

FIDIC’s Global Infrastructure Conference and the G20 programme taking place in South Africa is set to place infrastructure at the forefront of the development agenda for the global south. It comes at a moment when stakeholders across regions are actively reassessing priorities, exploring innovative delivery models and seeking to leverage climate finance for infrastructure resilience.

Meanwhile, the upcoming COP30 in Brazil will sharpen the global focus on adaptation and climate finance – issues that intersect directly with infrastructure planning in vulnerable regions. For emerging economies, COP30 represents an opportunity to advocate for equitable climate adaptation funding and to demonstrate that infrastructure can serve as a lever for both climate resilience and inclusive economic growth.

These events take place against the backdrop of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which remain a central framework for national development planning and international cooperation. Infrastructure, especially in energy, water, transport and digital sectors, is not only critical to SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), but also underpins progress across nearly all other goals, from health and education to climate action and economic inclusion (United Nations, 2015)8

At the same time, the ongoing dialogue around the reform of finance mechanisms be they public sector, private equity or multilateral development banks (MDBs) as the landscape of infrastructure finance is shifting. There is growing recognition that MDBs and International Financial Institutions must move beyond traditional risk frameworks to unlock investment in fragile and climate-vulnerable economies, an agenda that resonates deeply with FIDIC’s commitment to strengthening local capacity and embedding climate justice in infrastructure delivery.

These global conversations, taken together, highlight both the urgency and the opportunity of this moment. They demand a new narrative, one that positions infrastructure not merely as a technical challenge, but as a tool for social equity, climate justice and economic transformation.

The global urgency /

Reframing infrastructure as a driver of social equity, climate justice and resilience

For too long, infrastructure has been viewed primarily as a technical domain, a realm of engineering specifications, financing mechanisms and physical assets. Yet the infrastructure choices we make, and the way we design and deliver these systems, have profound social and environmental implications. In this report, we argue that infrastructure must be reframed as a lever for societal equity, growth, nature and climate improvement and long-term resilience.

This reframing starts with a recognition of how infrastructure shapes lives.

Roads and railways connect people to markets and services.

Energy systems power economies and provide the foundation for digital inclusion and innovation.

Water and sanitation infrastructure determines who has access to basic human rights, and who remains vulnerable to disease and environmental hazards.

At its best, infrastructure can unlock opportunity and inclusion, at its worst, it can entrench inequality and environmental harm.

For emerging economies, often on the frontlines of climate impacts and demographic transitions, this dynamic is particularly stark. where there is not just an environmental challenge, but a social one. Infrastructure systems that fail to account for climate risks or to serve marginalised communities exacerbate existing inequalities, pushing already vulnerable populations further to the margins.

This is why societal, climate, nature and economic wellbeing must be integral to infrastructure planning. It means designing projects that anticipate and adapt to climate hazards while prioritising social inclusion and equitable access. It also means embedding local knowledge and community driven approaches, ensuring that solutions reflect real needs and amplify the voices of those most affected.

Delivering on this vision will require more than policy ambition or technical capacity alone. It calls for a renewed commitment across the global infrastructure community including engineers, contractors’ policymakers, investors and practitioners etc to translate these principles into action. This report draws on the experience and insights of that community to highlight how transformative infrastructure can be delivered in practice. In doing so, it underscores a simple but powerful premise. Equitable and climate-smart infrastructure is not just a moral imperative, it is essential to building societies that are resilient, prosperous and prepared for the future.

/Realities on the ground – challenges in emerging economies

Realities on the ground – challenges in emerging economies /

Access,

affordability and infrastructure inequality

Access to infrastructure is a foundational pillar of economic and social progress. In many emerging economies, however, significant disparities in availability and affordability continue to undermine inclusive development. While global investment in infrastructure has grown steadily over the past decade, its distribution remains deeply uneven, leaving many of the world’s poorest communities disconnected from basic services.

For instance, in Sub-Saharan Africa, only 48% of the population has access to electricity, compared to a global average of 90% (IEA, 2022)9. Water scarcity affects nearly 400 million people in the region, driven by a combination of climate change impacts, rapid population growth and chronic underinvestment in water infrastructure. In rapidly developing economies such as India, over 30% of urban residents still live in informal settlements without access to basic sanitation or drainage, despite significant infrastructure improvements in some urban areas.

Affordability remains another critical challenge. In some cities, low-income households spend more than 20% of their income on energy alone, forcing families to make difficult trade-offs between basic services and other essential needs. In Lagos, Nigeria, studies have shown that transport costs can absorb up to 40% of household income for informal workers, limiting access to employment and reinforcing spatial inequalities (IEA, 2022).

In Nairobi’s informal settlements, the high cost of water services has been a persistent barrier, with households paying up to five times more than those in formal neighbourhoods (World Bank, 2023)10.

Beyond physical and economic barriers lies a systemic governance challenge: infrastructure delivery that does not meaningfully engage local communities often fails to address their real needs. Top-down approaches, while expedient, risk excluding the very voices that can shape more locally responsive and context-appropriate solutions. Meaningful community participation is essential, not only for project success, but to ensure that infrastructure truly serves as a foundation for equity and inclusion.

Realities on the ground – challenges in emerging economies

Environmental vulnerabilities: Droughts, floods and heat

Emerging economies face acute and multifaceted environmental challenges that profoundly affect infrastructure systems and the communities they serve. Droughts, floods and extreme heat are no longer isolated events; they are part of a shifting climate baseline that demands urgent attention from policymakers, engineers and investors alike.

Droughts are becoming increasingly frequent and severe across Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, disrupting agricultural production, water availability and hydropower generation. In the Horn of Africa, for instance, a record-breaking drought has displaced millions and placed immense strain on already fragile water supply and irrigation infrastructure (UNICEF, 2023)12. These cascading impacts highlight how water scarcity intersects with broader issues of food security, health and economic stability. The FIDIC State of the World Report on Water Infrastructure (Tackling the Global Water Crisis 2021)13 previously examined these systemic vulnerabilities, emphasizing the urgent need for adaptive, sustainable water management solutions to mitigate both scarcity and excess. Many of its findings remain critically relevant today as water crises intensify across emerging economies.

Conversely, many coastal and riverine regions in Southeast Asia and Latin America face heightened risks of flooding. In Bangladesh, annual monsoon floods submerge vast areas, damaging transport networks, power lines and essential social infrastructure (World Bank, 2022). In cities like Jakarta and Manila, a combination of sea-level rise, extreme rainfall and land subsidence has created a growing vulnerability to urban flooding (Asian Development Bank, 2023)14. These recurrent disruptions can halt economic activity, threaten lives and push vulnerable households deeper into poverty.

Extreme heat poses a third, equally critical challenge. In parts of South Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East, cities are experiencing record-breaking temperatures that exceed safe thresholds for human health and strain energy and transport systems. In India, for example, a record heatwave in 2022 caused road surfaces to buckle, rail networks to warp and a surge in demand for cooling that strained already overburdened electricity grids (World Meteorological Organization, 2023)15. These physical impacts are often most severe in informal settlements, where residents have limited access to cooling solutions and are more exposed to heat stress and related health risks.

Realities on the ground – challenges in emerging economies

Institutional and technical capacity gaps

Robust institutional and technical capacity is essential for the success of infrastructure systems, from initial planning and financing to ongoing operation and maintenance. In many emerging economies, however, these capacities remain constrained, limiting the effectiveness and sustainability of infrastructure investments.

Institutional gaps often manifest as fragmented governance structures, limited inter-agency coordination and inconsistent regulatory frameworks. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, overlapping mandates among transport and energy authorities in Nigeria have contributed to project delays and inefficiencies in power sector expansion (African Development Bank, 2022). In Southeast Asia, municipal governments in Indonesia frequently lack the financial autonomy or technical capacity to oversee large-scale infrastructure projects, leading to challenges in water and sanitation service delivery in secondary cities (World Bank, 2023)16

Technical capacity gaps are equally critical. Engineering and construction expertise, particularly in climate-resilient design, digital project management and sustainability practices, is unevenly distributed across regions.

A survey by the Asian Development Bank found that nearly half of infrastructure agencies in emerging Asia reported difficulties in accessing skilled professionals for project design and implementation (Asian Development Bank, 2023)17.

In Latin America, limited technical capacity has hindered the adoption of nature-based flood management solutions, despite growing climate adaptation needs in cities such as Lima and Bogotá (Inter-American Development Bank, 2022)18.

These gaps have direct implications for infrastructure outcomes. Projects may not fully align with local needs or climate priorities, and cost overruns and delays become more frequent, eroding public and local trust and deterring future investment.

In Ghana, for instance, weak regulatory oversight and capacity constraints have delayed key transport infrastructure projects, impacting regional trade connectivity (African Union, 2022)19. Most critically, the potential of infrastructure to drive equitable growth and climate resilience is constrained when institutional and technical systems do not have the resilience to be able to adapt to emerging challenges.

For the infrastructure sector, bridging these capacity gaps requires a multifaceted approach. Investment in human capital and professional development is essential, as is fostering collaboration between public,

Realities on the ground – challenges in emerging economies

Inclusive infrastructure: Addressing gender, accessibility and social vulnerability

Inclusive infrastructure is fundamental to ensuring that the benefits of economic growth and development are shared equitably across all segments of society. Many emerging economies, however, continue to face significant gaps in designing and delivering infrastructure that meets the diverse needs of their populations, particularly women, persons with different abilities and marginalised communities.

Gender disparities in infrastructure access and use are well documented. In Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, for example, women and girls in rural areas often spend hours each day collecting water and fuel because of inadequate infrastructure. This limits their educational and economic opportunities and reinforces cycles of poverty (UN Women, 2022)20. In urban areas, transport systems are frequently designed around male commuting patterns, overlooking the caregiving and household-related travel that women disproportionately understake (World Bank, 2022)21

Persons with different abilities face equally significant barriers. Globally, an estimated 15% of the population lives with some form of disability (WHO, 2023)22. Yet, inclusive design standards for transport networks, public buildings and digital services remain inconsistently applied, limiting access to employment, education and social participation. In Southeast Asia, for example, a lack of accessible public transport has been cited as a significant obstacle to economic participation and social inclusion for persons with disabilities (Asian Development Bank, 2023)23

Social vulnerability also extends to informal settlements and low-income communities, which often face compounded challenges in accessing reliable infrastructure services. In Latin American cities such as Lima and Bogotá, residents of informal neighbourhoods face higher costs and lower service quality for water, sanitation and energy, deepening inequalities and exposing them to greater health and safety risks (Inter-American Development Bank, 2022)24

These inequalities are not incidental. They reflect deeper systemic issues in how infrastructure is prioritised, designed and financed. Inclusive infrastructure requires moving beyond a purely technical focus to engage with the social dimensions of access and service delivery. This includes integrating gender and disability considerations into project design, embedding community engagement at every stage and using data to identify and address disparities.

For the infrastructure sector, investing in inclusive approaches brings both social and economic benefits. Infrastructure systems that respond to the needs of all users, including the most marginalised, are more resilient, sustainable and likely to deliver long-term economic and societal value.

Despite these challenges, there is growing momentum toward solutions that are both scalable and inclusive. Cities and rural communities alike are adopting decentralised energy models, leveraging digital tools for smarter service delivery, and investing in nature-based solutions to build resilience against climate risks. These promising approaches, explored in later sections, underscore how emerging economies are not just responding to infrastructure gaps but actively shaping a more sustainable future.

Realities on the ground – challenges in emerging economies

Case snapshots: Sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia and Latin America

The challenges of access, affordability and climate vulnerability are experienced in unique ways across different regions. These brief case snapshots illustrate how these challenges manifest in practice and underscore the importance of context-specific, inclusive, and resilient approaches in infrastructure development.

Sub-Saharan Africa: Nairobi’s informal settlements

In Nairobi, Kenya, rapid urbanisation has outpaced formal infrastructure provision, particularly in informal settlements like Kibera and Mathare. Residents rely on informal water vendors and unregulated energy sources, often paying significantly higher prices for lower-quality services than those in formal neighbourhoods. Climate change further compounds these vulnerabilities, with frequent flooding disrupting transport and sanitation infrastructure, causing health risks and economic losses (Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor, 2023)25. Recent initiatives by Nairobi’s county government and development partners have focused on upgrading water and sanitation systems in these informal areas, illustrating the critical role of targeted investment and community engagement in bridging infrastructure gaps.

Southeast Asia: Jakarta’s flood management challenges

Jakarta, Indonesia, faces some of the world’s most severe urban flood risks, driven by a combination of extreme rainfall, sea-level rise and land subsidence. Flooding events have repeatedly paralysed transport networks and damaged housing in low-income areas, disproportionately affecting vulnerable residents. The city has invested in large-scale infrastructure like sea walls and pumping stations, but experts argue that these must be complemented by nature-based solutions and inclusive planning to ensure long-term resilience (Asian Development Bank, 2023)26. This highlights the growing recognition that technical capacity, governance and social inclusion are as vital as physical infrastructure in achieving sustainable urban resilience.

Latin America: Lima’s informal water markets

In Lima, Peru, water scarcity and rapid urban growth have forced many residents of informal settlements to rely on expensive water vendors, paying up to 20 times more than those with formal connections (Inter-American Development Bank, 2022)27. Limited institutional capacity and financing gaps have historically constrained efforts to extend formal water services to these communities. However, recent efforts to integrate community-led solutions, combined with climate adaptation funding from multilateral development banks, have begun to close this gap. This underscores the importance of targeted financing and inclusive partnerships in addressing entrenched infrastructure inequalities.

These regional case snapshots demonstrate that while challenges vary across contexts, the core issues – of governance, capacity, social inclusion and climate resilience – are shared. They also show that truly transformative infrastructure systems emerge when technical solutions are integrated with inclusive planning and local knowledge.

/Scalable and affordable technologies

Scalable and affordable technologies /

Modular and prefabricated construction

Modular and prefabricated construction approaches given the right conditions can act as key enablers of affordable, scalable and climate-resilient infrastructure in emerging economies. These methods involve producing building components off-site and assembling them rapidly on-site, offering significant advantages in speed, cost efficiency and environmental performance compared to traditional construction.

The benefits of modular construction are particularly relevant in contexts where infrastructure demand is outpacing conventional delivery. In East Africa, for example, modular construction has been leveraged to address urgent gaps in healthcare infrastructure. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Rwanda deployed prefabricated hospital units to expand capacity rapidly and meet rising health service needs (African Development Bank, 2022)28. Similarly, in India, modular classrooms have been constructed to quickly scale access to primary education in rural and peri-urban areas, where demand has long exceeded conventional build capacity (World Bank, 2023)29.

From an environmental perspective, modular approaches can significantly reduce construction waste and limit the carbon footprint of infrastructure delivery. A study by the International Finance Corporation found that modular construction can reduce embodied carbon by up to 45% compared to traditional concrete and steel structures, while also lowering operational costs and improving building quality (IFC, 2023)30. These advantages align well with global efforts to decarbonise the built environment and meet climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

The

adoption of modular and prefabricated construction in emerging economies is not without challenges. High upfront investment in manufacturing facilities and supply chain logistics can create barriers, particularly in markets with limited access to affordable financing. Additionally, regulatory frameworks and building codes often lag behind technological advances, constraining innovation and uptake.

Scalable and affordable technologies /

For the infrastructure sector, integrating modular and prefabricated solutions requires not only technical expertise but also enabling policies and partnerships that support adoption at scale. Public-private partnerships can play a vital role in overcoming financing challenges, while standardisation efforts and supportive regulation can help mainstream these approaches into national infrastructure pipelines.

By leveraging these approaches, emerging economies have the potential to close infrastructure gaps more rapidly and cost-effectively, while also building the foundations for a more resilient and sustainable future.

While academic research, including studies from the Laing O’Rourke Centre at the University of Cambridge (Jansen van Vuuren and Middleton, 2020)31, highlights challenges in robustly benchmarking environmental impacts in modular construction—such as material use, waste reduction, and carbon emissions—the potential for improved sustainability remains a key area of exploration. Many industry case studies and practical applications suggest that off-site construction can reduce construction waste, enhance resource efficiency, and improve energy performance, particularly when paired with optimized supply chains and circular economy principles. However, the full extent of these benefits depends on project-specific implementation, material sourcing, and life-cycle analysis, underscoring the need for continued research and standardized performance metrics to substantiate broad claims about modular construction’s environmental advantages.

Many advocates of modular and off-site construction hope that these methods will deliver significant benefits—such as enhanced process control, reduced waste, and lower carbon emissions. However, robust empirical evidence to conclusively support these claims remains limited, with ongoing research highlighting challenges in benchmarking environmental performance. While modular approaches may offer efficiencies in certain contexts, their actual impact depends on material sourcing, implementation practices and life-cycle assessments, underscoring the need for further investigation and standardised evaluation frameworks.

Scalable and affordable technologies /

Off-grid and decentralised energy systems

Off-grid and decentralised energy systems have become increasingly critical in addressing energy access challenges in emerging economies. These systems, ranging from small-scale solar home kits to mini-grids serving entire villages, offer flexible and locally tailored solutions that can accelerate progress towards universal energy access and climate goals.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly 600 million people lack reliable electricity, off-grid solar systems have provided a lifeline for many rural and peri-urban communities (International Energy Agency, 2023)32. In countries like Kenya and Nigeria, decentralised solar mini-grids and home systems have not only expanded access to clean energy but also spurred local entrepreneurship and improved health and educational outcomes by powering clinics and schools (Power for All, 2022)33

These systems also offer significant climate and economic benefits. Decentralised renewables reduce dependence on diesel generators and other high-emissions energy sources, helping to lower greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. A recent study by the African Development Bank found that decentralised energy systems in West Africa can reduce CO2 emissions by up to 50% compared to conventional grid extension solutions (AfDB, 2023)34. Moreover, they can be deployed faster and more cost-effectively, particularly in remote or underserved regions.

Southeast Asia presents similar opportunities. In Indonesia and the Philippines, decentralised renewable energy projects have been critical in reaching island and mountainous communities where grid connections are logistically challenging and economically unviable (Asian Development Bank, 2023)35. These projects highlight the role of context-specific energy planning and the importance of integrating decentralised solutions into broader national electrification strategies.

Challenges remain in scaling up these systems sustainably.

Access to finance to fund capital costs is a persistent barrier, especially for smaller community-led projects, despite the longer term operational and societal benefits. Technical capacity gaps in installation, maintenance and system management can also limit long-term reliability. Addressing these constraints requires integrated policy frameworks that prioritise decentralised solutions as part of national energy plans, along with targeted investment in training and technical support.

For infrastructure professionals and policymakers, the rise of decentralised energy solutions underscores the need for flexible and adaptive infrastructure systems that respond to the diverse realities of communities. By bridging gaps in energy access through innovative, locally anchored approaches, off-grid systems are helping to lay the foundation for more resilient and inclusive development in some of the world’s most dynamic regions.

Scalable and affordable technologies /

Smart water and sanitation innovations

Reliable water and sanitation services are critical to health, economic development and climate resilience. Yet, in many emerging economies, rapid urbanisation, climate impacts and governance gaps have left millions without safe and affordable water and sanitation. Smart water and sanitation innovations are increasingly being seen as transformative solutions to bridge these gaps and build more resilient and equitable systems.

Smart technologies, including real-time sensors, digital monitoring tools and data-driven management systems, are enabling more efficient and adaptive water service delivery. In cities like Dakar, Senegal, water utilities have deployed sensor-based leak detection systems to reduce water losses, which in some networks exceed 40% of total supply (World Bank, 2022)36. These innovations are not only improving water security but also reducing operational costs and enhancing service reliability.

Sanitation is another area where smart innovations are making a difference. In India, digital platforms have been used to map and monitor informal sanitation facilities in urban slums, providing critical data to guide targeted investments and reduce public health risks (Asian Development Bank, 2023)37. In Kenya, decentralised wastewater treatment systems that incorporate smart monitoring are enabling safe water reuse in water-scarce communities, illustrating the potential for technology to drive climate adaptation and sustainable resource management (WSUP, 20233)38.

India example: Community-led sanitation management in Delhi

Project Raahat, initiated by Enactus Shaheed Sukhdev College of Business Studies in collaboration with the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board, focuses on the management of Community Toilet Complexes (CTCs) in Delhi’s slum areas39. The project emphasises operational management, aesthetic improvements and community sensitisation activities to promote hygiene and reduce open defecation. Innovative features include a ticket system to make toilet use affordable and the use of a cartoon character, Raahi, to educate children about sanitation. These efforts have significantly improved sanitation conditions in the targeted communities.

Kenya: Decentralized wastewater monitoring in Kisumu

In Kisumu, Kenya, a study published in PLOS Water evaluated the effectiveness of decentralised wastewater monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 as part of Covid-19 surveillance40. The research involved collecting wastewater samples from various community-based locations, including hospitals and public toilets, to detect the presence of the virus. The findings demonstrated that decentralised wastewater monitoring could serve as an early warning system for Covid-19 outbreaks, highlighting the potential of such systems in enhancing public health responses in resource-limited settings.

Scalable and affordable technologies /

Digital tools and AI for infrastructure monitoring and optimisation

Digital technologies are playing an increasingly critical role in transforming infrastructure systems, offering powerful tools to enhance efficiency, extend asset life and build climate resilience. In emerging economies, where resource constraints and rapid urbanisation intensify infrastructure pressures, digital monitoring and optimisation tools are essential to bridge capacity gaps and ensure sustainable delivery.

Remote sensing, data analytics and digital twin modelling are enabling infrastructure managers to anticipate risks and optimise performance in real-time.

In East Africa, water utilities in Uganda and Tanzania are using smart metering and remote sensors to detect leaks and manage water distribution more efficiently, reducing non-revenue water losses and improving access for underserved communities (World Bank, 2023)41. In South Asia, digital twin technologies are being deployed in transport networks to model traffic flows, identify congestion hot spots and inform more adaptive urban mobility planning (Asian Development Bank, 2023)42

These tools also offer critical insights for climate adaptation. In coastal regions of Southeast Asia, digital flood modelling platforms are helping local governments plan resilient infrastructure investments by simulating extreme weather scenarios and identifying vulnerabilities in transport and water systems (International Finance Corporation, 2022)43. Such data-driven approaches are vital to ensure that climate risks are not just recognised but embedded into infrastructure decision-making.

A notable example of digital flood modelling enhancing climate adaptation in Southeast Asia is Singapore’s “Virtual Singapore” initiative44. This comprehensive 3D digital twin of the city-state integrates real-time environmental and infrastructural data, enabling authorities to simulate extreme weather events, including flooding scenarios. By leveraging this platform, Singapore can identify vulnerabilities in its transport and water systems, facilitating informed decisions for resilient infrastructure investments.

In the Philippines, Project NOAH (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards) serves as another significant example45. This disaster risk reduction programme employs advanced technologies to provide real-time flood forecasts and hazard maps, assisting local governments in planning and implementing effective flood mitigation strategies.

These initiatives exemplify how digital tools are instrumental in aiding Southeast Asian countries to adapt to climate change by enhancing the resilience of critical infrastructure against extreme weather events.

The uptake of these digital solutions, however, is not without challenges. Limited digital literacy and uneven access to Information and Communication Technology (ICT) infrastructure in many regions can constrain adoption. Furthermore, data governance and privacy frameworks often lag behind technological advances, raising concerns about equitable access to data and the security of critical infrastructure systems.

Addressing these challenges requires a concerted effort to build digital skills within infrastructure agencies and local communities, as well as to foster inclusive public-private partnerships that can unlock investment in digital tools and data systems. For infrastructure professionals, embracing digital innovation is not merely a technical upgrade, it is a critical enabler of more transparent, efficient and climate-ready infrastructure systems.

Ultimately, digital monitoring and optimisation tools are not just about technology. They represent a broader shift toward data-informed decision-making and collaborative governance in infrastructure development. As this report explores, leveraging these tools can help emerging economies build the resilient, adaptive infrastructure systems that are essential in an era of accelerating climate and social change.

Case studies: Local innovations in India, South Africa and Brazil

The potential of scalable and affordable technologies in emerging economies is best illustrated through real-world innovations that adapt global solutions to local contexts. These case studies highlight how local leadership, tailored design and community engagement can deliver infrastructure outcomes that are both climate-resilient and socially inclusive.

India: Solar-powered cold storage for smallholder farmers

In India, post-harvest losses in agriculture have long been a major challenge for smallholder farmers, driven by a lack of affordable cold storage solutions. Recent innovations in solar-powered cold storage units have provided a scalable and cost-effective solution, reducing spoilage and boosting farmer incomes (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2023)46. In states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, these systems have been deployed in local cooperatives, integrating modular technology and digital monitoring to ensure reliable performance even in remote, off-grid areas. This innovation illustrates how decentralised energy and smart technologies can address intersecting challenges in food security, livelihoods, and climate adaptation.

South Africa: Modular healthcare infrastructure in rural areas

South Africa has been at the forefront of leveraging modular construction to close infrastructure gaps in underserved communities. The Limpopo Modular Health Clinics initiative, for example, has delivered prefabricated, fully equipped clinics in remote areas with limited access to healthcare (African Development Bank, 2023)47. These clinics can be deployed in a matter of weeks, compared to years for traditional brick-and-mortar construction. Crucially, the approach has been paired with capacity-building programmes for local healthcare workers, highlighting how modular technologies can be part of holistic infrastructure solutions that strengthen community resilience.

Scalable and affordable technologies /

Brazil: Digital water management in informal settlements

In Brazil’s favelas, access to safe water and sanitation is a persistent challenge, compounded by informal settlement patterns and governance gaps. The Água Carioca initiative in Rio de Janeiro has pioneered a digital water management system that combines real-time monitoring with community-led data collection to improve water access and quality (Inter-American Development Bank, 2023)48. By integrating smart technologies with participatory planning, the project has reduced water losses and improved health outcomes in some of the city’s most vulnerable communities. This case demonstrates how digital tools can be deployed in tandem with inclusive governance to deliver equitable infrastructure services.

These examples underscore a shared lesson – technologies alone do not guarantee impact. Success depends on integrating technical innovation with local knowledge, inclusive engagement and supportive policies that prioritise equity and climate resilience. For infrastructure leaders and practitioners, these case studies offer practical insights into how scalable solutions can be adapted to diverse contexts and how, when thoughtfully applied, they can unlock real progress in bridging infrastructure divides. Looking ahead, these local innovations provide a blueprint for future investments that align climate adaptation, social equity and economic development in the world’s most dynamic regions.

/Building local capacity and human capital

/Building local capacity and human capital

Community-driven infrastructure models

The effectiveness and resilience of infrastructure systems depend not only on technical excellence and financial resources but also on the meaningful involvement of the communities they serve. In many emerging economies, community-driven infrastructure models have emerged as critical pathways to ensure that projects are locally grounded, socially inclusive and adaptable to changing needs.

Community-driven approaches involve local stakeholders from municipal governments to grassroots organisations and informal community leaders in every stage of the infrastructure lifecycle. These models prioritise participatory planning, shared decision-making and the harnessing of local knowledge and labour. This not only builds trust and social cohesion but also ensures that infrastructure investments reflect real community priorities and can adapt to future challenges.

Examples from across the global south highlight the transformative impact of these models. In India’s rural regions, for example, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) has supported the creation of small-scale water, road and climate adaptation projects designed and implemented by local communities (World Bank, 2022)49. In Kenya’s informal settlements, community-based water committees have played a vital role in managing shared water resources, reducing costs and improving service reliability through collective action (WaterAid, 2023)50

Community-driven models also build local ownership and capacity in ways that traditional, top-down projects often cannot. In Latin America, participatory budgeting initiatives in cities like Porto Alegre, Brazil, have enabled communities to allocate funds for local infrastructure priorities, strengthening accountability and governance in the process (Inter-American Development Bank, 2023)51. In West Africa, farmer-led irrigation cooperatives have transformed degraded landscapes into productive agricultural zones, highlighting how community agency can unlock environmental and economic benefits (African Development Bank, 2022)52

For the infrastructure sector, these examples underscore the value of partnerships that go beyond contracts to build shared understanding and long-term resilience. Engineers and project managers working with community-driven models must adapt their roles from technical experts to facilitators and knowledge partners, supporting locally defined goals and embedding equity into every stage of delivery.

Looking ahead, integrating community-driven models into broader national and regional infrastructure strategies can help create systems that are more equitable, responsive and climate-ready. For policymakers, this means creating regulatory environments and financing mechanisms that enable community leadership to thrive. For practitioners, it means valuing social capital as much as technical and financial capital and recognising that inclusive infrastructure is ultimately smarter, more sustainable infrastructure.

/Building local capacity and human capital

Local training, apprenticeships and knowledge transfer

A sustainable and resilient infrastructure sector relies not only on physical assets but also on the skills and expertise of the people who design, build and maintain them. In emerging economies, investing in local training and apprenticeships alongside knowledge transfer from international and regional partners shows how crucial it is to building the human capital needed to deliver transformative infrastructure outcomes.

Training and apprenticeships provide pathways for local workers, particularly youth and marginalised groups, to enter the infrastructure workforce and gain valuable technical skills. In East Africa, for example, public works programmes in Tanzania have integrated construction skills training for young people, creating employment while also addressing local capacity gaps in road and water projects (International Labour Organization, 2022)53

In Southeast Asia, the Philippines’ Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) has partnered with private engineering firms to offer apprenticeships in green building practices, preparing graduates for roles in sustainable infrastructure delivery (Asian Development Bank, 2023).

Knowledge transfer is equally critical, enabling emerging economies to leapfrog traditional models and integrate innovative solutions more quickly. In Latin America, knowledge-sharing partnerships between regional universities and engineering consultancies have advanced climate-resilient transport and water management practices in Colombia and Peru (Inter-American Development Bank, 2023). In West Africa, twinning arrangements between local water utilities and international engineering firms have accelerated the adoption of digital water management tools, bridging gaps in technical expertise while strengthening local ownership of infrastructure solutions (African Development Bank, 2023)54

Beyond technical skills, these initiatives help build a broader culture of learning and collaboration that is essential for adapting to the complexities of climate change and rapid urbanisation. They also play a vital role in addressing social inequalities by opening opportunities for women and underrepresented groups to enter and thrive in the infrastructure sector.

For policymakers and infrastructure leaders, the lesson is clear. Investing in people is as essential as investing in projects. Sustainable infrastructure outcomes are built on a foundation of local capacity, not just to implement today’s projects, but to sustain, adapt and innovate in the face of tomorrow’s challenges.

/Building local capacity and human capital

FIDIC has played a crucial role in this landscape, setting the global standard for contracts that guide the procurement and delivery of infrastructure. Its suite of internationally recognised contracts and guidance documents has been widely adopted and adapted by governments and private sector actors alike, helping to promote fairness, quality and accountability in infrastructure delivery. By embedding these standards within local professional bodies and training institutions, FIDIC has supported capacity building and contributed to the strengthening of national systems for infrastructure development.

In Nigeria, for example, the Council for the Regulation of Engineering (COREN) has expanded its accreditation and professional development programmes, aligning national standards with global best practices and supporting the delivery of resilient infrastructure (COREN, 2023)55. Similarly, in Kenya, the Institution of Engineers of Kenya (IEK) has partnered with regional universities to integrate climate adaptation and digital tools into civil engineering curricula, preparing graduates to design infrastructure fit for a changing climate (World Bank, 2023)56

Universities are also central to bridging the gap between research and practice. In Latin America, universities in Chile and Colombia have developed joint research hubs with public agencies to pilot nature-based solutions in urban planning, producing replicable models that can be scaled across the region (Inter-American Development Bank, 2022)57. In Southeast Asia, regional engineering schools have begun to incorporate gender and social inclusion modules into infrastructure management degrees, building the social dimensions of sustainable infrastructure into technical education from the outset (Asian Development Bank, 2023)58.

Programmes like FIDIC Academy’s online and in-person courses can complement these local efforts, providing internationally recognised certifications and technical updates to support national training agendas. In addition, collaborative partnerships between local and international institutions, private sector actors and professional associations.

Persistent challenges, however, remain. Limited funding, outdated facilities and gaps in research capacity can constrain the ability of engineering institutions and universities to meet evolving sector needs. Addressing these challenges requires sustained investment and an inclusive approach to developing local talent and leadership.

For the global infrastructure sector, the strengthening of these institutions is not merely a question of workforce development. It is about building the intellectual and social capital needed to design and deliver infrastructure systems that are both inclusive and resilient. Supporting engineering institutions and universities is, therefore, an investment in the leadership and innovation that will shape the next generation of infrastructure solutions.

/Building local capacity and human capital

Inclusive skills development and gender-balanced capacity building

Inclusive skills development and gender-balanced capacity building are essential pillars of sustainable infrastructure delivery. They ensure that the benefits of infrastructure investment reach all segments of society and that local communities are empowered to play an active role in shaping and maintaining these critical assets.

In many emerging economies, women and marginalised groups continue to face barriers to participation in the infrastructure sector from technical training and apprenticeships to leadership and decision-making roles. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, women make up only about 15% of the engineering workforce, reflecting both cultural and systemic challenges (World Bank, 2023)59. Yet, evidence shows that when women and underrepresented groups are engaged in infrastructure planning and delivery, projects are more likely to address community needs and generate broader social and economic benefits.

Efforts to address these imbalances are gaining momentum. In Latin America, initiatives like Peru’s “Construyendo Igualdad” (Building Equality) programme have integrated gender-sensitive policies into public infrastructure projects, increasing women’s participation in technical roles and fostering more inclusive procurement practices (Inter-American Development Bank, 2023)60. In South Asia, India’s “Mahila Shakti Kendra” initiative has combined skills development with digital literacy training to enable rural women to participate more actively in local infrastructure projects and governance (Asian Development Bank, 2023)61

Beyond gender, inclusive skills development must also account for other forms of social disadvantage, such as disability, ethnicity, and rural-urban disparities. In Kenya, targeted technical training programmes have worked to address the exclusion of persons with disabilities from construction and transport sector jobs, both by adapting training content and by collaborating with disability rights organisations (African Development Bank, 2023)62

For infrastructure professionals and policymakers, the message is clear equitable infrastructure outcomes depend on equitable capacity-building. This means embedding inclusion as a core objective, not as an afterthought, in training, recruitment and leadership development.

As the infrastructure sector navigates the dual challenges of rapid urbanisation and climate change, inclusive skills development is not only a moral imperative but a practical necessity. Building capacity that reflects the diversity of the communities that infrastructure serves will be critical to delivering projects that are resilient, just and future-ready.

/Building local capacity and human capital

Examples: TVET in Rwanda and Kenya and institutional capacity building in Bangladesh

The transformative power of targeted capacity-building initiatives is vividly illustrated by recent examples from emerging economies. These initiatives demonstrate how technical and vocational education and training (TVET) programmes, combined with institutional strengthening, can help bridge persistent gaps in skills, governance and long-term infrastructure resilience.

In Rwanda, the government’s flagship TVET policy has created new pathways for young people and women to enter the infrastructure workforce. Supported by international partners and national engineering bodies, Rwanda’s Integrated Polytechnic Regional Centres (IPRCs) offer hands-on training in areas such as sustainable construction, renewable energy systems and water resource management (African Development Bank, 2023)63. These programmes have not only improved the employability of graduates but have also aligned skills development with national climate adaptation and digital transformation priorities.

Kenya has also emerged as a leader in aligning TVET with climate-resilient infrastructure delivery. Through the Kenya Climate-Smart Agriculture Project, technical colleges have introduced modules on climate-resilient construction and project management, providing rural communities with the skills to implement water conservation, irrigation and nature-based solutions (World Bank, 2023)64. These initiatives have empowered local communities to actively participate in shaping infrastructure investments that reflect local priorities and ecological realities.

In Bangladesh, capacity-building efforts have focused on institutional reform and upskilling at the policy level. The Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100, a comprehensive strategy for climate-resilient infrastructure and water management, has integrated capacity-building for civil servants and local engineers as a core component (Asian Development Bank, 2023)64 Workshops and twinning arrangements with regional universities have built the skills needed to translate global adaptation frameworks into locally grounded, context-sensitive strategies.

After all, what good is world-class engineering if it doesn’t meet the needs of the people it is built to serve? These examples underscore a shared lesson that capacity building cannot be a standalone effort. It must be woven into broader strategies for infrastructure planning, climate resilience and inclusive growth.

It is not only about developing technical skills but also about fostering a culture of continuous learning, leadership and accountability across institutions and communities. These lessons are increasingly evident in conversations with practitioners and local leaders across the global south, highlighting the urgency – and the opportunity – to embed capacity building into every stage of infrastructure development.

/Resilient investment models

/Resilient investment models

Financing gaps and reform

One of the most persistent challenges facing infrastructure development in emerging economies is the chronic mismatch between ambitious plans and the funding needed to make them real. While the scale of infrastructure investment required is vast and estimated at over $1.7 trillion annually for developing countries alone (World Bank, 2023)65 the flow of capital remains uneven and constrained by structural barriers.

A report from FIDIC and EY, launched in September 2023 at FIDIC’s Global Infrastructure Conference in Singapore, revealed the massive investment gap in sustainable infrastructure globally. The report, Closing the Sustainable Infrastructure Gap to Achieve Net Zero, found that a total investment of around $139 trillion is needed by 2050 to reach net zero targets, with a gap of $64 trillion compared to current investment trajectories. This underscores the urgent need for innovative financing structures and reforms to the multilateral development bank system to unlock and direct these essential resources towards climate-resilient and socially just infrastructure in emerging economies.

In work with policy and engineering communities, it has become clear that these financing gaps can stall critical projects, from climate-resilient transport corridors in Africa to off-grid water systems in Southeast Asia. These gaps are not merely financial shortfalls – they represent lost opportunities for communities to build resilience and thrive.

MDBs have historically and continue to play a crucial role in bridging these gaps, providing both capital and a framework for technical support. However, there is growing recognition that with growing public debt and economic uncertainty the system itself needs reform to meet the scale and complexity of today’s infrastructure challenges. Criticisms have focused on slow disbursement processes, overly risk-averse lending practices and frameworks that sometimes prioritise traditional large-scale projects over locally driven, innovative solutions.

Reform and investment efforts are gaining momentum. For example, the G20’s recent push for a “triple agenda” which involved MDBs and IFIs and mobilising more private capital, strengthening support for global public goods and enhancing country-level effectiveness, signals a shift toward more dynamic and inclusive financing (G20, 2023)66. Regional banks like the African Development Bank are also pioneering new models, such as climate adaptation bonds and blended finance facilities, to crowd in private investment and local capital.

Beyond policy reform, there is a growing appreciation for the need to make financing not only more available but more equitable and accessible. For communities on the frontlines of climate change and urban growth, affordable and transparent financing is essential to ensure that infrastructure projects meet their needs and aspirations. This means that reforms must be guided not only by macroeconomic metrics but by the lived realities of the communities these investments are meant to serve.

As we will explore in this chapter, closing financing gaps and reimagining the roles of various finance institutions is not simply a question of moving money. It is about creating an enabling environment that respects local contexts, empowers communities and ensures that infrastructure investment becomes a driver of inclusive and sustainable growth, not another layer of inequality.

/Resilient investment models

Blended finance, guarantees and public-private partnerships

As emerging economies work to close the persistent financing gaps in infrastructure, blended finance, guarantees and Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs or P3) have gained renewed urgency and attention. These tools are not new, but they have evolved into critical instruments for mobilising capital, sharing risk and bringing innovative solutions to scale.

Blended finance is the strategic use of public or concessional funds to de-risk investments and attract private capital and has shown promise in catalysing climate-resilient and socially inclusive infrastructure projects.

In Latin America, for instance, the Emerging Markets Infrastructure Fund has combined public seed capital with private investment to deliver renewable energy and water systems to underserved communities. Similarly, in East Africa, blended finance structures have supported the expansion of decentralised solar mini-grids, unlocking energy access in remote areas that have long been beyond the reach of traditional grid infrastructure (World Bank, 2023)67

Guarantees, meanwhile, remain a crucial yet underutilised tool for de-risking projects and reducing financing costs. Research has shown that well-designed guarantee schemes can lower the cost of capital by up to 30%, making previously unbankable projects viable (African Development Bank, 2022)68. Challenges in governance and implementation, however, continue including limited capacity to design guarantee structures and align them with local priorities, continue to constrain their use.

Public-private partnerships have also taken on new forms and relevance. In Kenya, the Nairobi-Nakuru-Mau Summit Highway PPP has successfully mobilised private finance while embedding local employment and gender inclusion targets (African Development Bank, 2023)69. In India, hybrid PPP models have enabled the delivery of metro systems in cities like Pune and Lucknow, blending public oversight with private sector efficiency to meet growing urban mobility demands (Asian Development Bank, 2023)70.

Yet for all their promise, these models are not panaceas. Experience has shown that poorly structured PPPs can exacerbate inequalities and fiscal risks if not carefully designed and monitored. That is why governments, financiers and technical partners increasingly emphasise the need for robust governance, local capacity-building and meaningful community participation as essential preconditions for success.

Additionally, emerging models of capital extraction—where developers are required to fund local infrastructure improvements as a condition of project approval—are also being explored as part of innovative financing solutions in Asia and increasingly in Western countries.

The most successful blended finance and PPP initiatives are those that are rooted in local needs and co-created with the communities they serve. These approaches go beyond financing to become frameworks for shared accountability and social value creation, critical elements in building infrastructure that is both financially sustainable and socially inclusive.

/Resilient investment models

Climate finance – rethinking risk in fragile economies

For many emerging economies, climate change is not a distant concern it is an immediate and compounding risk. From devastating floods in South Asia to persistent droughts in the Sahel, climate impacts are already testing the resilience of infrastructure systems and the communities they serve. Yet for all their urgency, climate-resilient infrastructure projects in fragile contexts still face a critical barrier, the perception of heightened financial risk.

MDBs and IFIs have historically been among the most important financiers of climate adaptation and resilience projects. Traditional risk frameworks and lending criteria, however, often discourage investment in the very regions that need it most. Countries experiencing conflict, political instability, or severe climate vulnerability frequently struggle to secure the concessional financing or risk guarantees needed to advance transformative infrastructure solutions.

Emerging reform initiatives are beginning to challenge this paradigm, which is being championed by the MDBs. The World Bank’s recent climate finance roadmap, for instance, explicitly calls for a rethink of how risk is assessed in fragile economies, proposing tailored risk-sharing instruments and a shift toward resilience as a primary investment criterion (World Bank, 2023)71. Similarly, the African Development Bank has piloted climate adaptation bonds in partnership with local governments, demonstrating how innovative financing models can be structured to address both climate and fragility risks.

Importantly, these shifts are not just about unlocking new capital flows. They are about changing mindsets and moving away from risk-averse, one-size-fits-all models towards approaches that recognise the dynamic realities of emerging markets. In this context, MDBs have a unique role to play, not only as financiers, but as conveners and champions of new climate risk methodologies that prioritise the voices and needs of frontline communities.

This rethink of risk is especially relevant for infrastructure professionals and policymakers in emerging economies. As experience has shown, the best-designed projects can still falter if financial risk perceptions make them too costly or complex to implement. By integrating more holistic, climate-sensitive approaches to risk – and by working in partnership with local institutions and technical partners – MDBs can help unlock the full potential of infrastructure as a catalyst for inclusive growth and resilience.

Innovative municipal or city-level funding

While national and multilateral funding remain central to large-scale infrastructure development, municipalities and cities are increasingly emerging as critical drivers of innovative financing approaches. As urban centres become the engines of population growth, climate adaptation and social inclusion, empowering them with tailored financial tools is essential to unlock their potential.

One of the most promising trends in this space has been the rise of municipal green bonds and other city-level financing mechanisms. In South Africa, the City of Cape Town issued Africa’s first green bond to fund climate adaptation measures, including water conservation and flood resilience infrastructure (City of Cape Town, 2023)72. This model has since inspired similar initiatives across the continent, highlighting how local governments can leverage financial markets to address climate challenges directly.