OUR YEARLY LOOK AT SOME OF THE PEOPLE WHO MAKE OUR COMMUNITIES UNIQUE

Faribault’s

Owatonna’s Sandra Boss is a pioneer for local girls sports 3 5

John St. Clair gives artisans a place to sell their goods

Global lessons inspire Vicki Dilley’s decades of service in North eld

Nicollet’s Ryan and Lonita Schmidt carry on meat market family legacy 8 12

Waseca’s Tom Sexton driven by service to country and community

Faribault’s Keith Radel helping restore bluebird population in Rice County

Matt and Deb Gillard strive to make everyone a home in Owatonna 15 18 20

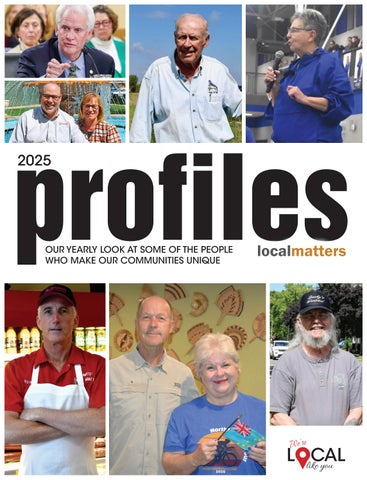

John “Spanky” St. Clair standing in front of his Makers Market sign. He helped create it for makers in town who wanted to showcase their work for people to buy. (Lauren Viska - Faribault.com)

By LAUREN VISKA lauren.viska@apgsomn.com

Three summers ago, John “Spanky” St. Clair arrived at the Faribault Farmers Market, ready to set up his woodworking booth as he had for years. But the welcome he expected didn’t come. The organizers told him makers were no longer welcome.

Most people might have walked away. Not St. Clair. Instead, he decided to create his own market, giving Faribault artisans a space to sell their handmade goods and keep local commerce in town.

“I was sick and tired of everybody from this town going to Northfield or Owatonna for their crafts,” he said, reflecting on the moment that sparked the Makers Market. “They’d spend their money outside, and it never came back here. There wasn’t a real outlet for crafters in Faribault, so I went to Parks and Rec and got it started.”

The result was the Faribault Makers Market, now in its third year, held from 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. every Saturday running from the weekend after Heritage Days until the end of October, weather permitting. Seventeen vendors participate, selling everything from carved wooden flags and jewelry boxes to reclaimed barnwood wall art.

“I make it easy for them,” St. Clair said. “I only charge $60 for the whole season, and they don’t have to come every week if life gets busy. I know it’s summer and there’s family obligations and whatnot, so if they’re only here for half the season, I’m happy, and they’re happy.”

Even with years of experience at the farmers market, St. Clair felt the town’s crafters were missing a proper spotlight.

“I just started this because I wanted people to have a venue to come to for crafts that are local instead of leaving town,” he said. “Don’t get me wrong, I think the farmers market is great, I just think the crafters and makers in town need a place to showcase their work.”

St. Clair’s approach to the market is for makers only — he wants people who make their own items to come and sell their crafts.

“I don’t want them to do [multi-level marketing]”, and I don’t want a garage sale because I’ve had people come saying they have stuff to sell, but they didn’t make it themselves,” he said. “I know it may sound strict, but this isn’t a garage sale, it’s a makers market — I want people like me who make their own items to have an outlet to sell their work.”

Customers have noticed the difference. Shoppers often spend 30 to 45 minutes wandering the park, stopping at each vendor, talking with artisans, and leaving with something unique. Vendors report sales are often triple compared to other events, a testament to St. Clair’s thoughtful design and communityminded approach.

“It’s rewarding to see the vendors thrive,” he said. “They tell me all the time how much they appreciate this space. I’m doing it for the community, not for fame or fortune.” St. Clair credits others for helping launch

the market, including Kari Caspter, who assisted in finding vendors and organizing the first year.

“I wouldn’t have been able to have a successful first year without her help,” he said. “She doesn’t help out anymore as she’s doing a million other things, but she helped get it kickstarted.”

While the Makers Market showcases local artisans, St. Clair himself is a talented woodworker. He began learning the craft in 2020, immersing himself in YouTube tutorials for months before buying tools and opening his business.

“I’ve always been interested in wood,” he says. “I wanted to make something with my hands, something that people could enjoy.” — Spanky’s Woodshed. His creations range from American flags — both traditional and Punisher-skull designs — to cutting boards, jewelry boxes and large wall art made from reclaimed barnwood.

great story to tell people.”

At first, St. Clair didn’t like the nickname, but it’s grown on him. A tattoo on his leg commemorates the story, a permanent reminder of the humor, camaraderie and adventure that motorcycles brought into his life.

Though St. Clair didn’t grow up in Faribault — he was a military brat who lived in various places — he has built a strong connection to the community since moving here in 1997. He fondly recalls visits with his mother to the Lavender Inn, a now-closed restaurant.

John “Spanky” St. Clair standing next to the Central Park sign. He hopes to have the Makers Market added to the sign with the Farmers Market. (Lauren ViskaFaribault.com)

“I would like to fill the park every Saturday with as many vendors as possible. I want to see it grow. This town has a lot of talented people and I want them to have their chance to shine.”

- John “Spanky”

St. Clair

with as many vendors as possible,” he said.

“I want to see it grow. This town has a lot of talented people and I want them to have their chance to shine.”

St. Clair said one thing he hopes to accomplish in the future for the Makers Market is better signage.

“During the pet parade this year, the one I had out there, somebody ripped it off,” he said. “Like, why would you do that? People can be mean sometimes and not have respect for things that are somebody else’s property, but eventually I’d like to have the Makers Market added to the same sign as the Farmers Market.”

“I love working with barnwood,” he said. “It’s reclaimed material and I’d rather save it from being burned and turn it into something meaningful.”

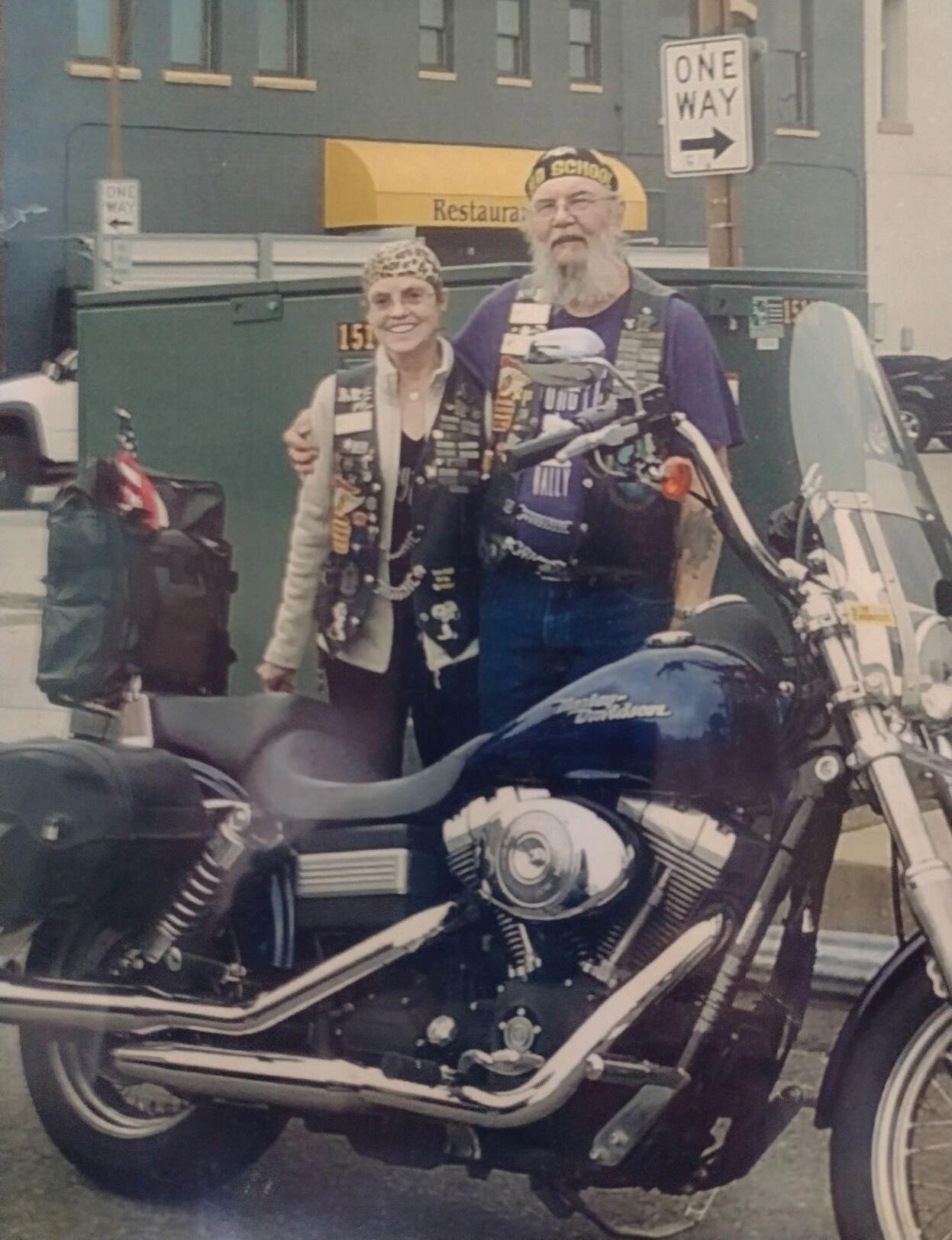

While woodworking and community building fill much of his time today, motorcycles have always been a passion. St. Clair started riding in 2000, fulfilling a lifelong dream that had been tempered by caution in his younger years. His father, a motorcycle racer, had always warned him about the risks.

“I knew if I did it too young I wouldn’t be here, so I waited and I am so glad I did,” he said. “I think another reason I waited is because my father was 100,000% against motorcycles, but he raced motorcycles since he was a kid. He’d been on a bike and he was a wild man, so he thought that the apple wouldn’t fall far from the tree.”

He’s owned a Suzuki Intruder and a HarleyDavidson Street Bob, the latter being his favorite for long-distance travel and power. Together with fellow riders, he’s traveled throughout

southern Minnesota and even to Iowa’s Amana Colonies and the Grotto.

“There’s more power with the Harley,” he said. “I could actually pull a trailer with it. The Suzuki was a fun bike, but it wasn’t for travel — the Harleys are for travel.”

St. Clair no longer rides motorcycles due to his age, but he does miss it.

“I really miss riding, but with arthritis and back problems, I can’t do it safely anymore,” he said. “If you can’t make an emergency stop, you shouldn’t be on a bike.”

St. Clair received the nickname “Spanky” during a motorcycle rally chili contest in 1999, when a fellow rider playfully smacking him with a cutting board due to the fact that he brought all the ingredients to make the chili, but forgot one important tool — the cutting board.

“Wacky Jackie had a cutting board with a handle on it, and smacked me on the butt with it,” he said with a laugh. “The chapter president and one of the other guys looked at me and said, ‘Well, it’s Spanky,’ and I said, ‘No, it’s not happening,’ but the nickname stuck, and it’s a

“We had to stop there every time we visited my grandparents in Iowa,” he said. “I loved the hamburgers and meatloaf — they were the best. I’m sad they have since torn it down, however many years ago.”

These small memories feed into the pride he feels for Faribault today. Whether it’s reclaiming wood for a wall hanging or creating a thriving Saturday market, St. Clair’s work is rooted in connection, nostalgia and community.

As the Makers Market continues to grow, St. Clair dreams of one day filling Central Park with vendors every Saturday, potentially reaching 88 booths. He hopes this expansion will give more local artisans a platform and attract more residents to shop and socialize in Faribault.

“I would like to fill the park every Saturday

Despite occasional challenges — weather, city regulations or even the rare theft of a sign— St. Clair remains steadfast. He isn’t seeking fame or fortune. His reward comes in the smiles of vendors and shoppers alike, the sense of pride in his work and the knowledge that he’s strengthened his community — one handmade creation at a time. Walking through Central Park on a Saturday morning, it’s clear that St. Clair has done more than create a market. He’s built a hub for craft, community and creativity— a place where Faribault can come together, celebrate local talent and enjoy the simple pleasure of a Saturday in the park. n

Sandra Boss showcases the gymnastics gym she’d spent 55 years advocating for. (Lizzie Cooper - Owatonna.com)

By LIZZIE COOPER elizibeth.cooper@apgsomn.com

Growing up in an age where girls were taught to save their bodies for future motherhood, one woman moved to Owatonna to begin her career as a teacher and coach. She didn’t know it at the time, but she would eventually pioneer multiple girls sports teams and advocate for equality between girls and boys sports in the Owatonna school district.

After 55 years of advocacy, Sandra Boss went from coaching the very first gymnastics team at Owatonna to getting a gym exclusively for gymnasts.

In 2013, Boss was inducted into the Minnesota State High School Coaches Association Hall of Fame for her efforts. She said she was the second or third woman to ever be inducted into the Hall of Fame, and the association had

just started to recognize women’ s involvement in coaching.

About a 20 minutes drive south of Park Rapids lies Sebeka, Minnesota, Boss’ hometown. Throughout her childhood, she loved playing outside with her neighborhood friends.

“I loved to play. I liked to play outside, I liked to swim, I liked to bike, I loved to play any kind of game that I could play and I tried it all. If we could find an old tennis racket somewhere, then we would go and try to play tennis, and if a basketball was somewhere, we would go and shoot baskets. In the neighborhood, we played a lot of softball and just played on the playground,” Boss explained.

In junior high school, she began to teach swimming lessons at a lake in the neighboring town. She would go there on a bus with the other swim instructor and a group of children,

trying to teach them how to get off the dock. This was one of her first stepping stones to what would eventually become her teaching career.

Boss had a high school physical education teacher and plenty of college professors who were aware girls sports were going to happen in the near future. She said she had a lot of mentors who helped her realize she wanted to pursue teaching and coaching.

Being a coach was something Boss always knew she wanted to do. However, when she started attending the University of Minnesota, she majored in chemical engineering. After a year she realized she couldn’t see herself in the field, and that being around people and being active was something she prioritized in her life.

Boss moved to Owatonna in the fall of 1969, shortly after she’d graduated from the University of Minnesota. At the time, schools were hiring lots of teachers and she was able to get hired to be a gymnastics coach — a title alone that made history. She was the first

“I waited 55 years for the girls to have their own gym, and they have it. And then they won the state championship, which was just frosting on the cake. To win that trophy was pretty darn special.”

- Sandra Boss

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 5

woman coach and the first salaried coach in the Owatonna district.

During Boss’ early years in the Owatonna school district, schools had a Girls Athletic Association (GAA) and a Girls Recreation Association (GRA). These organizations had girls participating in sports, but they weren’t recognized or organized enough to be considered as “teams.”

Girls sports slowly developed over the years to add more programs. When girls basketball started, the school had it in two seasons – fall and winter. During the fall, the boys were outside playing basketball so the girls had access to the gym. Boss said people at the time couldn’t fathom having girls and boys share a gym in the wintertime for basketball practice.

Girls sports did exist in the ‘30s and even before then, but they weren’t recognized as official teams. Owatonna was once a state basketball champion in girls sports, and Boss said she thought the year was about 1902.

When Boss first came to Owatonna, a lady called her and said she was on the aforementioned basketball team. Boss wasn’t able to stay in contact with her, but the woman she spoke with had a scrapbook with all the information about the Owatonna girl’s basketball team from the early 1900s.

“I think the administration at the Owatonna High School really was pretty proactive. They wanted to be in with the leaders, and they knew it was coming,” Boss said. “They knew that women weren’t being silent anymore, that they wanted to have those opportunities. I always felt that the principal, the athletic director, the superintendent were all behind girls sports.”

Despite how proactive Owatonna was in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, there was one central issue — they didn’t want to sacrifice anything the boys had. This led to some struggles with getting girls’ sports started up.

Boss first advocated for girls to have their own uniforms. When the school finally approved these uniforms, the girls would keep them for the entire school year, using them for several sports. Eventually, girls were able to get their own sport-specific uniforms, but this took many years of advocacy.

“We accepted it because it was better than anything we ever had before,” Boss said. Another challenge was the hassle of setting up and tearing down all the gymnastics equipment before and after each practice, which was left for Boss and the student athletes she coached.

“In 1992, we went into an agreement with the Owatonna Gymnastics Club and we went out there to practice, which was great because it gave us the opportunity to not have to put back the equipment,” Boss said.

After being at the gymnastics club for nearly 30 years, Owatonna was building a new high school and Boss heavily advocated to let the gymnastics team have their own gym. She invited the superintendent and the School Board chair to come and see what the team had to deal with for meets, which included uneven seating surfaces and a lack of room for spectators. She said it was time for the girls to have their own gym, not sharing it with any other sports.

The old high school gym was finally given to the gymnastics team, and the space was transformed. A pit was dug and plenty of mats were permanently set up for the team. Now, the gymnastics gym has proper bleachers and equipment. During the first practice of this year, the bleachers were full of people watching.

“When I came to town, the school had decided that they were going to offer gymnastics,” Boss said. “When I interviewed, I said, ‘Well, I’ll coach a gymnastics team, but can I start a swim team too?’ and they said, ‘Sure.’”

Through the GAA and GRA program, girls sports got more and more organized. Boss was able to help organize girls teams for volleyball, basketball, gymnastics and track. The girls responded with an eagerness to try new things

and be competitive, with many participating in three to four sports throughout the year.

“Everybody was so enthusiastic and just so anxious to prove that girls could compete, too, that girls could be in sports and have fun,” Boss said. “Until that time, in the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s, they were telling girls that we had to save our bodies for being mothers. We didn’t want to harm any body parts that might hinder you from having babies. Isn’t that crazy?”

“I waited 55 years for the girls to have their own gym, and they have it. And then they won the state championship, which was just frosting on the cake,” Boss said, nodding to the historic 2025 title win.

“To win that trophy was pretty darn special,” she later said.

About the time Boss started working at Owatonna, Burnsville and Bloomington had

big meets for boys, and girls were allowed to participate in a few races. Eventually, an official track meet was formed. The first Owatonna girls state tournament was in track in 1972, the year the local team was started.

“We had really good luck and some really good athletes,” Boss said.

The girls track team was in the top four in the state within its first five meets. Then, in 1976 the girls won the track and field state meet, but Boss wasn’t coaching at the time as she was at home caring for her newborn child.

After her children got older, Boss went back to coaching track at a junior high level until she retired in 2008. In 2022, the high school team celebrated 50 years of state track meets. Boss

and her husband have fun following the teams and seeing how they’re doing.

“I keep involved with athletics in Owatonna,” Boss said.

To this day, she works for volleyball, cross country, basketball, gymnastics and track and field as a scorekeeper, meet manager, or whatever else the teams need. She also volunteers at the high school for the lifetime activities class, helping students learn how to ride bikes.

“I can’t walk away. Every year, you see something good start to happen. You just have to go the next year and see what happens next,” Boss said.

Boss currently plays in Faribault’s granny basketball team, playing together once a week through the fall and winter. Every spring, they have tournaments with Wanamingo’s team once a month because they’re the only other granny basketball team in Minnesota.

Sports aren’t the only thing Boss stays involved in. She is active in her church, playing in the bell choir and is an eucharist minister. She is also one of the superintendents in the textile department at the Steele County Free Fair and

has stayed involved in the fair for 38 years. She volunteers with the local historical society, which involves sitting in the houses during the yearly Extravaganza. She and her husband clean out the cottage in the springtime often, and sell root beer floats during the fair.

In the rest of her free time, Boss enjoys staying active, be it through swimming, biking, hiking, kayaking and other outdoor activities.

“I try to stay busy,” she said with a smile. n Reach Reporter Lauren Viska at 507-333-3128. © Copyright

By COLTON KEMP colton.kemp@apgsomn.com

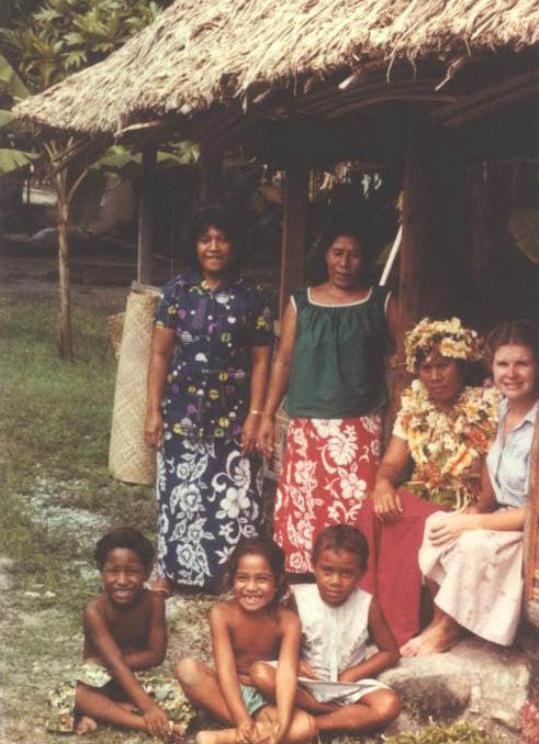

The fourthsmallest nation in the world, Tuvalu, consists of a series of islands about halfway between Hawaii and Australia.

Despite living in the nation with smallest total GDP in the world, Vicki Dilley said the people of Tuvalu “live in abundance.” Her years on the island are what inspire her service in Northfield and beyond to this day.

“I think who I am today is because of living on the island, the sense of community,” she said. “Community means so much more to me after living there. Nobody goes without on the island.”

Today, she’s proudly a past president of Northfield Rotary Club, chairs

the Rotary Bike Tour Committee, has been involved with Women in Northfield Giving Support for 25 years, helped lead the Taste of Summer and is the chair of the Justice Initiative Committee at Emmaus Church — just to name a few of her service roles.

Vicki grew up in Wyoming before moving to Montana at the age of 16. She graduated high school in Laurel, just outside of Billings.

In the summer of ‘74, she was working a summer job at Red Lodge Pea Cannery alongside a man named Lee Dilley, who was a student at the University of Montana. They became romantically involved, eventually marrying in ‘78.

Shortly after Lee’s graduation, the Dilleys were accepted into the Peace Corps, eventually finding themselves in Tuvalu to do “community development.”

Lee worked on fish ponds, water catchment and storage, as well as making soap out of coconuts. Vicki worked in well baby clinics and started a nursery school there, as well as helping develop technology for a cookless stove.

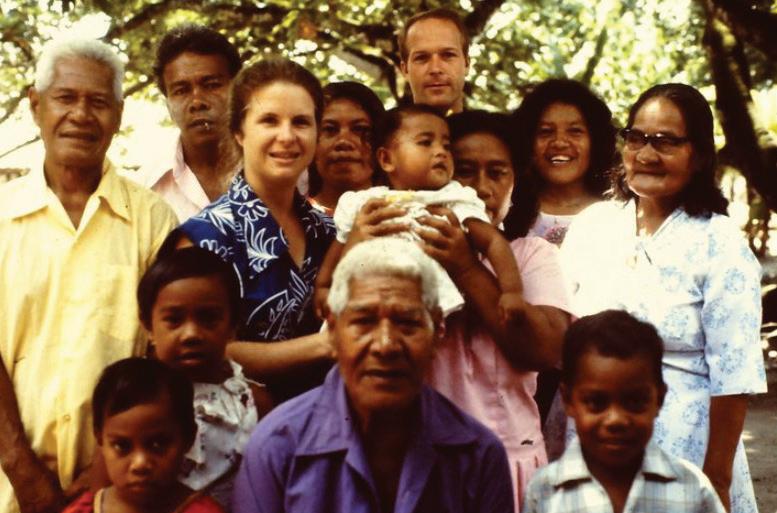

They lived on the 3-mile-by-2-mile Tuvaluan island for 3.5 years with a host family she called her “adopted family.” She still refers to them as family, and even Skypes regularly with her “sister.”

The community dynamics on the island were different than in Western culture. To describe what she meant, she offered a story about her “father,” which begins with her gifting him a new shirt.

She waited and waited for him to wear the new shirt, but the day never came. Finally, she asked if something was wrong with it.

“No, I just can’t wear it when my neighbor doesn’t have a new shirt too,” he told her.

She said people brought them fish and coconuts every day, just because they knew the Dilleys couldn’t get them themselves. Vicki said a widowed woman with children would have an entire community helping her along the way.

“That sense of equity, equality in the village was — it just took deep roots within me,” she said. “To understand what it is to

together,

and how some are able to contribute more, and some, you know, they’re under your care as well. So I think I approach so much of what I do in service and life that way.”

She said when it came time to leave the island and lead some Peace Corps training in Fiji, her “father” petitioned the government to transfer land to the Dilleys. He said if they owned a piece of land, they “would certainly come back.”

To him, she explained, richness and abundance weren’t concepts related to wealth and fortune.

“I don’t think many of us feel like we live in abundance,” she said. “We always long for the next thing. But they lived in abundance. They thought they — they knew, not just thought. They knew they were rich. They knew they had abundance. Because they had safety. They had fellowship with their neighbors.”

She gave the example of two neighbors fighting over a fence that’s slightly over a property line, or arguing over one neighbor’s leaves falling into the other’s yard.

“It’s just totally foreign to them,” she said. “Sometimes, as time goes by, I have to shake myself and go, ‘Vicki, go back to your origins there. Remember that what you have is to be shared, and to be living in that abundance.’ It just changed us in such profound ways.”

While not quite fluent, Vicki is one of just 13,000 people globally who can speak the Tuvaluan language.

After the Peace Corps, Vicki and Lee went to live near the farm where Lee grew up in Castle Rock, just north of Northfield. Lee returned shortly after coming back to Minnesota to finish a project they’d started in the Peace Corps. He was only there a few months.

Vicki returned once in 2002, bringing her daughter along this time. But things have changed in Tuvalu — and it’s only getting worse.

After seaplane service ended there in 1983, the only way to the outer islands is to travel by cargo ship. The trip, if made in a straight shot, takes about eight hours.

Climate change has caused increasingly violent storms — which she said have largely become unpredictable — and have made it so

cargo ships can only travel at certain times. Once they were there, it could be weeks before the boat could return.

Rising sea levels, also due to climate change, are an extreme vulnerability for Tuvalu. Vicki said climate refugees have already begun to leave by the thousands. In 2023, Australia agreed to open citizenship pathways for climate-related refugees from Tuvalu.

Scientists have predicted the entire country will be underwater by 2050, she said.

“Anyway, so this is a whole culture, a whole language,” she said. “All these people that get displaced need to find new homes. It’s the beginning of the end for them. So, I have come to understand the value of their culture and how much it taught me, and now that gets dispersed into the rest of the world. How much they take with them, I don’t know. But I know that they’re trying.”

Vicki and Lee had two children of their own, and have hosted many international students through the Rotary Youth Exchange Program. Their biological daughter is named Riana, a Tuvaluan name. Their son, Evan, has the middle name Tavita, which is also Tuvaluan. Her host sister also named her daughter after Vicki.

“We’ve always just tried to continue to, if we’re not traveling, bring the world to us in here,” she said. “So over the years, we’ve probably hosted well over 30 people from different countries.”

Lee worked at Malt-o-Meal for a little over

CONTINUED ON PAGE 10

doesn’t feel so hard.”

She said the committee isn’t the only group in Northfield “pulling their own weight.”

“Northfield is just one of those unique places,” she said. “I call it a little piece of magic, the way that this community does come together. Harking back on Tuvalu and living there, I feel like we’re not perfect, but I think we do care about each other. You know, if somebody is suffering over at Viking Terrace, the community comes together. And that has been demonstrated.”

While Vicki’s passion and drive for service to others might seem unique to many, it doesn’t feel that way for her.

“I’m not unique in this community,” she said. “This community gives and gives a lot. I just like being a part of it. If I can offer some leadership now and again, I’ll do that.”

She said she’s less confident about the rest of the world, adding that she wishes “people would see each other, really see each other as human beings, see each other as valued, that nobody’s greater than the other.”

30 years, and Vicki wound up working for a nonprofit called Project Zawadi. The group leads safaris in Tanzania and works to form replicable educational programs that are sustainable for the communities.

One of the exchange students, a boy from Brazil who she still is in contact with today, asked Vicki why she wasn’t in Rotary. She wasn’t sure what the group really was, but soon thereafter joined in 2005. Vicki quickly took over the exchange program.

She continued to help or chair various committees, organizing events or coordinating partners. In 2023, she took over the Bike Tour.

“It’s really suffered because we couldn’t do it through COVID,” she said. “It was, I think, two years off, and then for two years they tried to do it on a different date than Jesse James weekend. It felt like it barely had a heartbeat.”

She moved the tour back to Defeat Days weekend. She formed a partnership with the Dundas Dukes ball field, which serves food for participants after the tour. At the suggestion of Imminent Brewery owners, she also partnered with Chapel Brewing, which donates hundreds of free beers — one for every rider of drinking age.

Despite all this, she said not to give her the credit of saving the bike tour.

“The committee, we stick together,” she said. “We like working with each other. I appreciate

every single one of them that’s on the committee, because they each pull their own weight in an equal way. When you’re a chair of something, and everybody’s pulling their weight, it

“I think, [my life advice would be to] approach life with relational curiosity,” she said. “There’s so much to gain from knowing other people, hearing their story and understanding where they come from. Sometimes I make quick judgments on somebody, and then I hear their story and go, ‘Oh my goodness, there’s so much more depth to you than I ever imagined.’” n

“There’s so much to gain from knowing other people, hearing their story and understanding where they come from. Sometimes I make quick judgments on somebody, and then I hear their story and go, ‘Oh my goodness, there’s so much more depth to you than I ever imagined.’

- Vicki Dilley

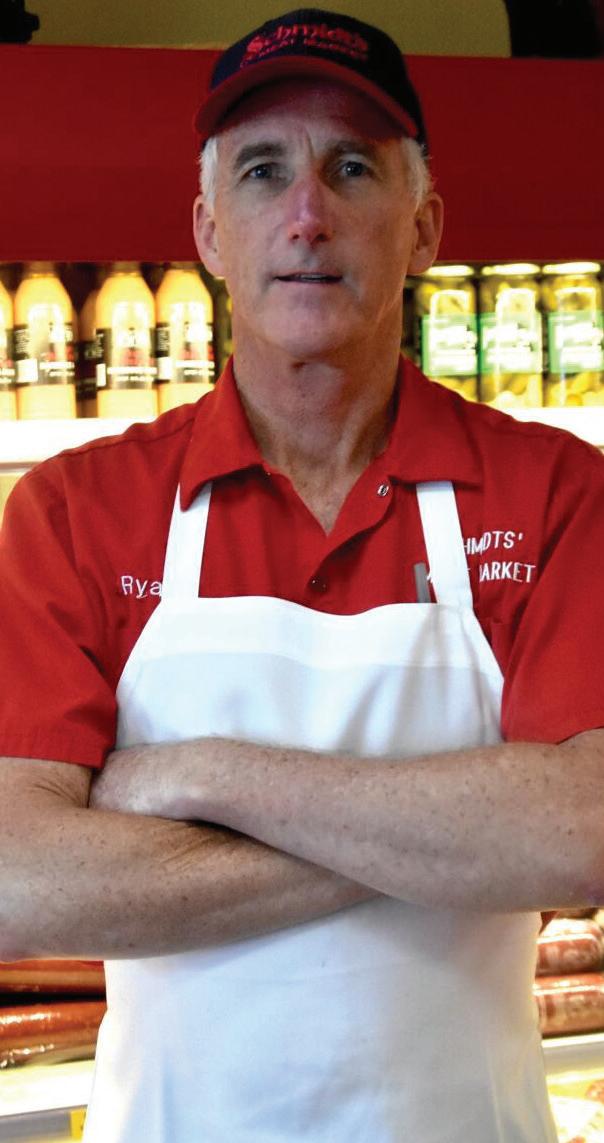

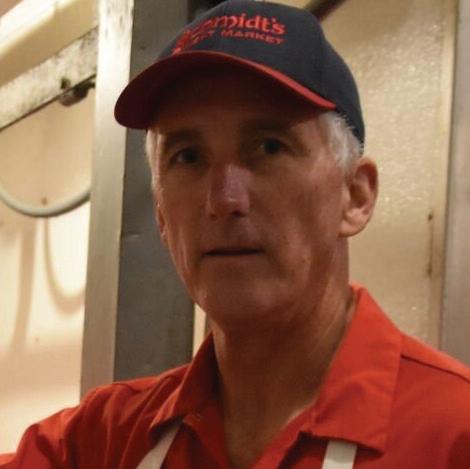

Ryan Schmidt, the third generation of Schmidts to own and operate Schmidt’s Meat Market stands in front of the business’ signature summer sausage. (Carson Hughes - StPeterHerald.com)

n the heart of Nicollet, just 12 miles west of St. Peter, customers come from far and wide to be greeted by the “Wilkommen” sign on the half-timbered, German-styled exterior of Schmidt’s Meat Market.

The savory aroma of the market’s signature summer sausage being cooked in their traditional wood-fired smokehouse brings in visitors from all across the state eager to try what has been consistently rated one of the best processed meats in all of Minnesota.

Behind that summer sausage — which recently took the grand champion and best in show ribbons in the Minnesota State Fair’s processed meats championship — and the hundreds of different kinds of meats and cheeses stocked on the market’s shelves are husband-and-wife team Ryan and Lonita Schmidt.

Seven days a week, customers will find at least one of the Schmidts behind the counter with their 55-plus employees, managing the

By CARSON HUGHES carson.hughes@apgsomn.com

78-year-old business. The store is not only the largest meat market in southern Minnesota, it’s a family legacy passed down through the generations.

Ryan is the third generation of Schmidts to run the market, founded in 1947 by his grandparents Gerhardt and Esther Schmidt, who had bought an existing one-room butcher shop from Anthony Woodley. The store was their literal livelihood, hosting not only the smokehouse, production area and the retail space where the Schmidt’s made their income, but an apartment space as well where they raised their two boys Gary and Bruce.

Ryan’s father, Gary, and uncle, Bruce, lived and breathed Schmidt’s Meat Market, living at the store building with their parents and regularly assisting them at the shop when they came home from school. It wasn’t much of a surprise then when the two would come to take over the business in 1975.

Under Bruce’s lead as the the day-to-day manager and Gary’s oversight as the store’s accountant and marketing manager, Schmidt’s Meat Market underwent numerous changes —

seeing a 3,000-square foot expansion in 1984 after the store’s acquisition of the neighboring Nicollet Oil Company property, the addition of new wood-fired and electric smokehouses in 1995 and the doubling of the retail space in 2003 to incorporate the deli.

The renovation came just two years prior to Ryan Schmidt buying out his father’s portion of the business in 2005. He and his wife, Lonita, would become the sole heads of the

“

operation in 2008 when he bought the remaining shares from his uncle Bruce.

Like his father before him, Ryan grew up helping around the shop, starting around the age of 14, though he hadn’t always intended to take over. After graduating from Minnesota State University with a degree in finance, he would go on to spend a decade in California before moving to the Twin Cities. It was in the metro area where Ryan met his wife, Lonita.

My grandpa used to have a very simple saying and it resonates true. ‘If you put good stuff in, you get good stuff out.’ It’s all about, what are the meats that you put in - pork beef, whatever it might be, the seasoning you use.”

- Ryan Schmidt

She was working in United Healthcare’s finance department where Ryan had recently come on board as a consultant.

“I had no idea,” Lonita laughed, when asked if she ever imagined she would one day be working at a meat market. “It’s all been fun that’s for sure, but yeah I definitely didn’t imagine that I would be in the spot that I am.”

Ryan said he became interested in taking over the business due to wanting a change in his life away from the finance world he had been occupying.

“It just kind of goes back to the upbringing and discussions around the table about the business. I guess I ultimately wanted to be in control of my own destiny. Being your own boss versus working for somebody was intriguing,” said Ryan. “I knew they had a good solid business and I was ready for a change from what I had been doing.”

Ryan said what sets Schmidt’s apart is its commitment to old-world craftsmanship. Unlike many markets that have switched to modern electric smokehouses in the past 25 years with liquid smoke or gas generators, Schmidt’s still uses traditional wood-fired smokehouses to process meats. That and the market’s selection of ingredients are what helps bring its meats to another level.

“My grandpa used to have a very simple saying and it resonates true. ‘If you put good stuff in, you get good stuff out.’ It’s all about, what are the meats that you put in — pork beef, whatever it might be, the seasoning you use,” said Ryan.

The market now makes nine different varieties of its signature summer sausage and carries more than 100 varieties of sausage in total, with flavors ranging from classic bratwurst to bolder, trend-driven offerings like jalapeño-cheddar and blueberry wild rice sausage. The shop also has a deep supply of jerkies, chicken breast, fresh cuts of beef and pork, blocks of cheeses, sauces and more.

Ryan said he’s regularly looking for new products to attract new customers and keep existing patrons coming back. Over the 20 years he’s operated the store, Ryan said he’s seen tastes change with younger crowds seeking bolder and hotter meat products. Meat snack sticks like teriyaki and honey BBQ beef jerkies are also on the rise, encompassing a growing part of the business.

“Snack sticks in general, that part of our business has grown quite a bit, along with jerky,” said Ryan. “It’s good for traveling and doesn’t need to be refrigerated because it’s shelfstable.“

Part of operating a meat market is regularly seeing suppliers come in pitching products and experimental flavors, which can sometimes come with unexpected results.

One of Schmidt’s most popular products came about when they had been using raspberry chipotle seasoning as the basis for a chicken marinade. A supplier came in one day and suggested they try combining it with a pork product, like bacon. It was right in time for the state meat convention, so the Schmidts decided to test their experiment there. The bacon would go on to win grand champion and best in show. The results encouraged them to try making a small batch for sale.

“I think within about three hours we had to put a second post out there that said ‘We are out. We will be making more,’” laughed Ryan.

“That product today still sells fantastic.”

It’s moments like these that Ryan said are the best part of the job. From watching his staff be creative with new products, to working the deli counters and interacting with customers, hearing stories of where they’re from.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 14

“How far our name and products are known, it’s fun to listen to customers and hear some of those stories,” said Ryan. “Especially when you get into the holidays, people will be doing holiday gatherings and bringing families together from near and far.”

The holidays hold a special place at Schmidt’s. Every December, the store is decorated with holly and pine to celebrate one of the store’s busiest seasons as customers line up for specialty cuts that have become part of family Christmas feasts for generations.

“A lot of our customers have been coming to the store for quite a while. My favorite part is being part of the family traditions,” said Lonita.

“We hear that so much, especially around the holidays, where they have a certain special meal they get from Schmidt’s or the summer sausage or getting jerky as stocking-stuffers.”

Like many small businesses, Schmidt’s has faced its share of challenges. Labor shortages have hit the meat industry particularly hard, a trend that began even before the COVID-19 pandemic. Where once there were plenty of teens willing to help pack and slice meats, those numbers have started to dwindle in the new millennium.

“The education system seems to be shifting where kids are now all heading off to college

and looking for more white-collar jobs, rather than meat-cutting and sausage production and stuff like that. We saw that coming and knew we had to get efficient,” said Ryan.

While labor challenges affect all sides of the business, the production side has been hit the hardest as an increasing number of candidates come with little to no meat experience. Where there used to be many technical colleges that would train these skills, Ryan said many of those programs have since disappeared in the last 20 years.

To keep things running, the Schmidts have been dedicated to operating the business. Ryan is in-store all week long while Lonita spends three days a week working there during the regular season, and all week long during the busiest times of the year in the fall and holiday seasons.

On those days where they can get away from the business, the Schmidts will often go vacationing, enjoying the outdoors and activities like hunting, snow skiing and spending time at Ryan’s parents’ lake house.

As Ryan reflects on nearly two decades at the helm, he acknowledges he is closer to the end of his career than the beginning. Nothing is for certain, but he sees a future where his now college-aged sons might carry on the family tradition.

“At that point they seem to have plans to get into the business after college, so we’ll see where that goes,” said Ryan. n

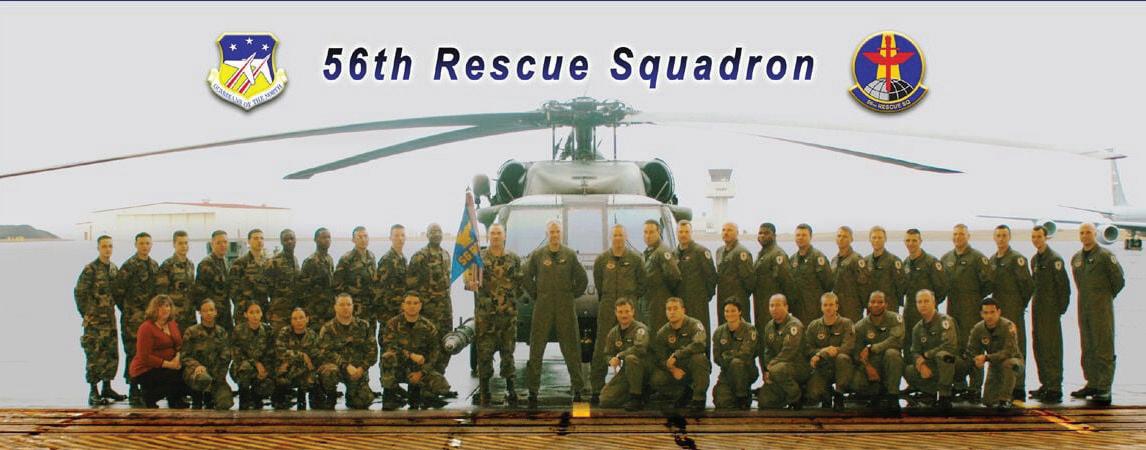

By ANDREW DEZIEL andrew.deziel@apgsomn.com

Long before stepping onto the floor of the Minnesota House of Representatives as one of 21 first year legislators, Rep. Tom Sexton’s passion for public service and love for Waseca were instilled from an early age by his parents and grandparents.

Born in Omaha, Sexton has been on the move ever since, spending just a few years in one place at a time in the U.S. Air Force and in his subsequent career as a project manager and executive working to bring large scale pipeline projects to fruition.

Sacred Heart High School in 1951 and enrolled in the U.S. Army Reserves the following year.

Sexton wrapped up his 26 year career in the U.S. Air Force at U.S. Army War College, as a student for one year and an instructor for the next four.

The oldest of three, Sexton is the son of Dick and Mary Sexton and the grandson of Leon Sexton, who served as Waseca’s postmaster in the 1950s and was active in the community as a Municipal Judge, member of the Waseca County Fair Board and in other roles.

After a childhood that took place amid the backdrop of the Great Depression and World War II Dick Sexton graduated from Waseca’s

In 1953, he was called up to active duty and dispatched to Germany, where he helped the Germans rebuild their country following the destruction of WWII and, his son proudly notes, built a railroad that remains in the area to this day. Following an honorable discharge, Dick returned home, earned a degree from the University of Minnesota and joined the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development as an inspector and architect, ensuring federally funded housing projects met federal requirements. When he was a little kid, Tom Sexton recalled going with his father to the annual air

shows at Offutt Air Force Base near Omaha. By that time, the United States was deeply involved in the Vietnam War and the military was eager to flex its muscles.

While he was only about 5 or 6 years old at his first air show, it made quite an impression on the young Sexton and stuck with him. Years later, he would join the ROTC program at the University of Minnesota, paving the way for a 26-year career in the Air Force.

The Sexton family’s time in Nebraska was relatively short, as Leon was able to get a job with HUD in the Twin Cities. After a few years of commuting from Waseca to the metro for work, the Sextons moved to an outer ring development of the Twin Cities, in an area that

is now Lakeville.

Still, Waseca played a special role in the heart of Tom Sexton throughout his life. Even when they weren’t living in Waseca, he was in town often to see his grandparents, and it was in Waseca’s own Clear Lake Park — so near to his grandmother’s house — that he learned to swim.

That skill would later come in handy when Sexton enlisted in the Air Force after graduation from the University of Minnesota, where he initially aspired for an engineering degree but switched to business due to not having quite enough background in calculus.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 16

ter’s Degree in National Securities Studies. He was then assigned to Joint Special Operations Command at Fort Bragg in North Carolina.

While Sexton was at Fort Bragg, the U.S. became involved in Afghanistan following the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and subsequently Iraq. In a non-flying assignment role, Sexton helped to negotiate with various countries to secure air space for U.S. and coalition air operations.

Sexton’s next two stops took him to Iceland’s Naval Air Station Keflavik, a hub for NATO Air Policing in the region, and U.S. Army Garrison Stuttgart in Germany. At the latter stop, Sexton’s work focused heavily on Operation Enduring Freedom-Transahara.

Redesignated as Operation Juniper Shield in 2013, the operation focused on helping 10 African nations to better secure their borders, cognizant that al-Qaeda affiliated terrorist groups were attempting to move their operations to Africa after the fall of Taliban-controlled Afghanistan.

Pipeline expanded capacity on a route connecting two of Enbridge’s most important hubs. From Cushing, oil continues down the Seaway Pipeline to and from ports along the Texas gulf coast.

The project was powered by seven massive pump stations, each of which uses about half as much power as would be required to power Superior, Wisconsin. While he didn’t come into the job with a ton of direct experience in the construction industry, Sexton said that Enbridge appreciated the project management expertise he brought with his background in the military.

Sexton left Enbridge in 2017 to accept a position as Vice President of Field Services at UniversalPegasus International in Houston, surveying proposed pipeline routes and working with landowners along those routes to secure the needed permissions.

FROM PAGE 15

Determined to avoid taking on the burden of student loans, Sexton worked his way through college, simultaneously working as a security guard in St. Paul, as a caretaker at the Minnesota Zoo (located near the family home) and as manager at a Twin Cities apartment complex.

One summer day in 1985, one tenant in the apartment complex left Sexton a note saying that her faucet was dripping and she wanted it fixed. Though he was tired after working a full day at the zoo, Sexton came over to the apartment to tear apart and fix the faucets.

Over a pizza, Sexton struck up a conversation with his future wife Jeanne, who he had only met briefly before when he first got the job. The two would keep talking as friends, and it might have stayed that way had Sexton gone to pilot training in 1985 as initially planned.

As chance would have it, Sexton’s orders came in just a few weeks too soon as classes at the University wouldn’t wrap up until the first week of June. During the 10 month delay that followed the rescinding of the order, Sexton courted and proposed to Jeanne.

In the spring of 1986, Sexton began his military journey with a three-week flight screening program in San Antonio, Texas. Sexton came into the program with some experience flying in the Twin Cities through the University of Minnesota’s ROTC program.

Here, Sexton’s experience of swimming in Clear Lake would come in handy as he pursued his goal of flying helicopters right off the bat. While swimming wasn’t part of the Air Force ROTC program, you’d need such skills in order to be able to pass the dunker portion of the training.

Among the more nerve wracking portions of pilot training, the “dunker” training is designed to ensure that pilots are prepared to safely handle a situation in which their helicopter crashes into the water, potentially during nighttime conditions.

In order to pass dunker training, pilots need to demonstrate strong enough swimming skills to hold up safely even in a terrifying scenario in which they might be submerged and battling against disorientation and darkness and needing to swim some 75 yards.

While another pilot had been expected to fill the helicopter slot, he lacked the swimming experience necessary and also had an interest in going to fixed wing training and learning to fly F-16s. So, he and Sexton convinced their superiors to allow them to switch spots.

After completing his pilot training, Sexton was assigned to Alabama’s Fort Rucker and then transferred to Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque. At first, Sexton flew the famous Vietnam Era “Jolly Green Giants” (Sikorsky HH-3E helicopters).

In 1987, Sexton was deployed on his first overseas assignment at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines. He served there until 1990, just one year before the eruption of a local volcano forced the base’s closure.

Sexton then returned stateside for training as the Air Force transitioned over to the HH-60, its version of the Army Black Hawk helicopters. While he was still training in Albuquerque, Operation Desert Storm abruptly launched and then concluded in a matter of weeks.

Sexton said the change in aircraft was like going from a “VW bus to a Ferrari,” so much more powerful and also more sensitive the Black Hawk helicopters were compared to the reliable and relatively large but underpowered HH-3E helicopters.

The HH-60s were also well built for special operations, but Sexton noted the Army at the time had a somewhat more robust capacity for special operations than the Air Force. After he was fully retrained for the new aircraft, he was selected to serve at Fort Campbell, a U.S. Army base on the Kentucky-Tennessee border, as part of an exchange between the Army and Air Force.

The specific aircraft Sexton flew while serving at Fort Campbell was the “MH-60 Kilo,” a variant of the Black Hawk helicopter that was somewhat larger and heavier with additional equipment specifically designed to assist in the completion of special operations.

It was in 1993 that Sexton was involved in what would become the most famous mission across his 26 years in the Air Force, participating in “Operation Serpent Gothic” which was launched by President Bill Clinton against Somali National Alliance fighters and other insurgents.

The operation culminated in the Battle of Mogadishu against insurgents in the south of Somali capital Mogadishu, which ook place on Oct. 3 and 4 of 1994 and was profiled in the 1999 book Black Hawk Down, with an eponymous film based on the book released in 2001.

After his time as an exchange pilot in the Army ended, Sexton was assigned to United States Special Operations Command, which oversees special operations across the whole of the U.S. Military. There, Sexton worked on various joint aviation operations.

From 1998 to 1999, Sexton attended the Air Force’s Air Command and Staff College in Montgomery, Alabama, graduating with a Mas-

Sexton attended U.S. Army War College in Pennsylvania from 2007 to 2008 and was then expected to deploy to Afghanistan to help coordinate the NATO Alliance’s operations there. However, the Dutch military instead requested to fill the position and their offer was accepted.

Instead, Sexton stayed on at U.S. Army War College but as an instructor before retiring from the Air Force as Colonel in 2012. He said the decision to retire was driven by a desire to settle back down in Minnesota with his youngest son, Mark, set to graduate from high school.

Raised across the both country and the world as Sexton was moved from one assignment to the next, both Sexton sons have since entered the Air Force as Officers. Sexton’s eldest son Matthew has a pending promotion to Lieutenant Colonel.

Given his broad experience in leadership and operations management, Sexton didn’t have much trouble finding a civilian job. Taking advantage of more than three months of leave he had accumulated during his quarter century in the military, he returned to Minnesota early to begin work as a facilities construction manager for Enbridge.

While based in Duluth, Sexton’s work with Enbridge was largely focused on the Flanagan South Pipeline. Constructed in 2013 and 2014, the roughly 600-mile pipeline ran from Enbridge’s Flanagan Terminal in central Illinois to Cushing, Oklahoma.

Running largely parallel to the already existing Spearhead Pipeline, the Flanagan South

Subsequently promoted to Vice President of Construction Management, Sexton was working nearly six to seven days a week to help bring projects to fruition. At the time, under the first Trump Administration, he said that demand was incredibly high for new pipeline projects.

When President Joe Biden took office and canceled the Keystone XL Pipeline, Sexton said that the pipeline industry immediately entered a tailspin. Spooked investors feared that even projects well along in the permitting and construction process could get wiped out with the stroke of a pen.

After taking several months to close down the books on some $400 million in cancelled projects, Sexton finally moved back to Waseca. Jeanne’s mom would move to Waseca too, moving into the house Dick and Mary Sexton once called home, keeping her nice and close to the family.

Rebuffing offers to return to the pipeline construction industry, Sexton settled into a comfortable semi-retirement in Waseca, but found himself getting pulled into more and more commitments. When a position opened up on the Waseca County Planning Commission, an old friend from his time at Sacred Heart — County Commissioner Brian Harguth — invited him to fill the role.

Soon, Sexton was a member of both the Waseca County and city of Waseca Planning Commissions. In those roles, Sexton became increasingly determined to help Waseca find ways to encourage housing development to close a shortage of roughly 300 units of housing.

and had been urging Sexton to throw his hat in the ring.

Long before coming to Waseca, Rostislavovich built a career in Minnesota Republican politics, working for high profile Minnesota Republicans like Rep. Vin Weber and Sen. Rod Grams. While he’d been retired since last working for Gov. Tim Pawlenty, he offered to come out of retirement to serve as Sexton’s campaign manager.

ing reductions to cover a projected $6 billion shortfall.

Sexton was also living near Clear Lake as he did during his childhood,and was quick to join the Waseca Lakes Association. Upon hearing that Waseca Lakefest could fall by the wayside after no one stepped up to replace Joan Mooney, he decided to step up again to take on the task of organizing the beloved Fourth of July festival.

When State Rep. John Petersburg announced he wouldn’t seek a seventh term in 2024, local Republicans began looking for a strong candidate to succeed Petersburg in what has become a a safely red district in the Trump era.

Several local Republicans urged Sexton to step forward, but he was very hesitant to throw his hat into the ring. He’d never previously given the idea of being politically involved much thought, having been conditioned to be strictly apolitical while in the military.

Sexton was also fully cognizant of how much Jeanne had sacrificed to support his military

career and how much family time he’d missed. Now a grandpa, he was determined to be there as much as he could for her and for his kids and grandkids.

After saying no initially twice, Sexton talked it over with Jeanne on an 18-hour road trip to Albuquerque to see their kids and grandkids. With Jeanne’s full support and encouragement, he finally decided to say yes.

While the Sextons knew little about how to secure the Republican endorsement, they got help from local hypervolunteer Mikhail Rostislavovich, who currently serves as President of the Waseca Chamber of Commerce and the Waseca Arts Center, among many other commitments.

Active in the Waseca County Republican Party along with his brother Dwight Tostenson, Rostislavovich came to know Jeanne through their involvement in the Waseca Exchange Club

While Sexton may have been a political newcomer, local Republicans quickly warmed to his business and military experience. He crossed the 60% threshold to secure the GOP endorsement on the second ballot, then easily dispatched challengers in the Republican primary and general election.

Sexton talking with a St. Paul Police Officer following his election to the Minnesota Legislature.

At the State Capitol, Sexton walked into a uniquely fraught situation. Not only was polarization between Republicans and Democrats deeper than ever, both along ideological and regional lines, voters had sent an exactly equal number of Republicans and Democrats to the House.

After much political maneuvering and tension, the two parties did manage to pass a compromise budget as required under state law, despite the challenges of having to find spend-

Sexton came to the Capitol expecting plenty of gamesmanship and he wasn’t disappointed. He said that it reminded him of the jockeying between Ambassadors, the Pentagon and the State Department to get their way on military operations. Still, he said he’s really enjoyed and appreciated the honor of representing local constituents in St. Paul and trying to find solutions to challenges they face, from the large to the small. Amid the polarization, Sexton also said he has tried hard to hear the opinions of all, including through his “Coffee with Tom” roundtable events.

“I want to make sure I’m available for everybody,” Sexton said. “As a representative, I represent everybody regardless of their affiliation partywise.” n

Andrew Deziel is a reporter for the APG Southern Minnesota Newspaper Group. Reach him at 507-333-3133. © Copyright 2025 Adams MultiMedia of Southern Minnesota. All rights reserved.

Keith Radel has spent four decades caring for bluebirds in Rice County, helping them to thrive by building them houses and checking on them weekly while they nest. (Chloe Kucera — Faribault.com)

By CHLOE KUCERA chloe.kucera@apgsomn.com

“I just think the world would be a better place if there’s bluebirds when I’m dead and gone because they’re just a gorgeous bird.”

- Keith Radel

It’s not often that someone would be willing to dedicate 40 years of their life to bring back a species of bird from near eradication to their local area, but that is precisely what Keith Radel has done. He has spent four decades caring for bluebirds in Rice County, helping them to thrive with a touch of human intervention. At age 76, he shows no signs of slowing down with his conservation efforts.

Radel’s interest in bluebirds can be traced back to his childhood when he made a kite in grade school that had a picture of that bird on it.

“I’d never seen [a bluebird], and I never did try to fly the thing,” he said. “I don’t think it would have flown, but I really was fascinated with bluebirds. It might be God given, I think.”

As Radel got older, he learned that the blue-

bird population was in trouble. In the 1970s, the price of fuel oil rose, causing the heating bills of many households to increase. People began cutting down dead trees and burning them as an alternative. This destroyed bluebird habitats as they are secondary cavity nesters that use holes created by woodpeckers.

“A bluebird can’t make its own hole,” he said. “Well, when all the dead trees got cut down, there went their nest places.”

The state of the bluebird population was dismal in Rice County, according to reports at the time.

“In 1979, nobody saw a bluebird in Rice County, not one adult,” Radel said. “And nobody had seen any nests either. So they were just about gone.”

This lack of presence was felt around the state. Dick Peterson, founder of the Bluebird Program of Minnesota, began to implement efforts to save the birds. He built bird boxes for

the bluebirds to nest and would check in on them every week to see if he could help them reproduce. His work was successful, inspiring people like Radel to join in and help out.

Radel and his wife came to the Faribault area in 1982, after selling his 80-acre farm in southwest Minnesota. With a passion for spending time outside, he started a landscaping business.

As Radel became connected with local birders, he learned about bird boxes and how to build them. He recalled a special moment when he went with a friend to check some boxes on land where the Minnesota Correctional Facility now stands.

“That was where I saw my first bluebird ever,” he said. “One up above the boxes in a tree on a dead tree branch. Now I couldn’t believe how blue they were. Henry Thoreau, the writer, said, ‘It’s the bird that flies with the sky on his back.’”

“Rice County is the number one county in the state for Bluebird production and has been for over 30 years. We fledge 3,000 plus a year here. No other county has ever fledged 2,000.”

- Keith Radel

In 1986, Radel began building his own bird houses using a plan from a book by the DNR called “Woodworking for Wildlife,” but he was not satisfied with the model.

“After using it for two years, I decided it was a piece of junk because the nest got wet,” he said. “Then, I started looking for a different style.”

He moved on to a Peterson house model patented by the founder of the Bluebird Program of Minnesota. Now he uses a lightweight, cylindrical-style house that can be removed from the post to look in on. Radel enjoys this feature because it makes it easy to show others what is happening in the nest.

Throughout his years of bird box building, Radel has learned through a lot of trial and error. He was using wood posts that animals could climb up and eat the eggs. Then, he used steel poles, but found that woodland creatures

could still get inside the house. He has resorted to skinny metal tubing, which works the best.

His birding friends helped him learn as well. He had put up bird boxes on his property and didn’t have any luck getting bluebirds in his first year. One of his friends came out to visit and

pointed out all the things he was doing wrong. There were too many boxes for the area they were arranged in. Some were mounted to trees, allowing animals to access the boxes, and the holes were too small for the birds to get in.

The following year, he made some changes and was able to raise eight birds successfully.

Then, he became involved in the Bluebird Program of Minnesota after attending the Bluebird Conference. Gaining lots of knowledge from fellow bluebird enthusiasts, he returned home and began his great bluebird house endeavor. With permission from property owners around Rice County, he established various sites to raise bluebirds throughout the area.

Currently, Radel monitors 186 different sites, with two houses at each spot. Every week, from April to August, Radel visits each site to check on the nests, ensuring they are dry and free from any pests.

This year, the bluebirds laid 11,163 eggs, with 931 hatched and 798 fledged from the nests. This season, the county experienced an unusually heavy rain in May, resulting in a loss of 150 baby birds. However, Radel cleaned and dried those boxes, and 22 of the 24 were nested again successfully. Though the experience was disheartening, Radel was happy that ultimately, his intervention made a difference.

With the work Radel and other bluebird enthusiasts have done in the community, Rice County now has an impressive population.

“Rice County is the number one county in the state for bluebird production and has been for over 30 years. We fledge 3,000 plus a year here,” he said. “No other county has ever fledged 2,000.”

Having done work with bluebirds for decades, Radel is affectionately known as “The Bluebird Guy” in the community. He said it has been pretty neat to get recognized in public. If he is at the grocery store or driving into a driveway to check on his sites, people will ask how the bluebirds are doing. He mentioned that many of the properties he owns have residents who have never seen a bluebird until he

installed a site.

By sharing knowledge and helping others set up their own bluebird boxes, Radel loves sharing in enthusiasm about birds.

“It’s more exciting for me when new people get them than me,” he said. “I’ll never forget that first bluebird I ever found in mine. Well, if you want to have that great feeling again, just help somebody have it, too.”

Bluebirds hold a special place in Radel’s heart, and he believes others could be inspired by the way they live.

“I just think the world would be a better place if there’s bluebirds when I’m dead and gone because they’re just a gorgeous bird,” he said. “If you watch a pair of bluebirds, you could do worse than to pattern your family life after them. Mom and Dad stick together. She builds a nest. He protects her while she builds so another bird doesn’t come in and get her, and he brings her food when she’s sitting on the eggs.”

Radel hopes that the Bluebird Program of Minnesota can gain more volunteers to share in their mission of sustaining bluebirds for the future. With volunteers on the decline, Radel wants people to understand the benefits of helping out for a cause.

“I hope the younger people pick up on the volunteering, because it doesn’t seem like they are,” he said. “Most organizations that rely on volunteers are having real troubles, and we’re hoping that changes, because you can make such a difference. I mean, I like landscaping, and it was fun, but for a business, it was great. But the satisfaction that I get from being around nature, you don’t get that sitting in the house.”

While on his bluebird checks, Radel expressed that he feels fortunate for the unique nature experiences he has had. From seeing a fawn nurse from its mother to watching a pheasant mom with eight chicks behind her, Radel has no shortage of stories to tell.

By ANNIE HARMAN annie.harman@apgsomn.com

After 20-plus years of finding people the perfect home, it has never been the actual structures that moves Matt and Deb Gillard, owners of Owatonna’s RE/MAX Venture.

Instead, the Gillards have a bigger goal: making Owatonna a dream home for all.

The Gillards could easily be known for their business acumen alone. But for those who truly know them, their legacy lies not in the properties they sell, but in the lives they touch.

The Gillards know a thing or two about second chances. Their own marriage is one. Both had previously been married and were navigating the messy, vulnerable space of starting over when fate — and a

very determined friend, Lisa Havelka — intervened.

“I had just gone through a divorce,” Deb recalled. “Lisa was trying to set me up, and I wasn’t interested.”

But when Matt walked into that happy hour, something clicked. “He gave me a hug and said, ‘No one wants to get divorced. It feels like a failure.’” That empathy struck a chord.

They married two years later, blending their families and their lives. For Matt, who had a son just starting school, and Deb, whose kids were teenagers, it was less about merging than it was about expanding.

“It was never ‘step kids’ — they’re ‘our’ kids,” Matt said. “I genuinely love them.”

Now, with grown children and grandchildren, the Gillards look back on that leap of faith with gratitude.

“If I had lived my life afraid to start over, I would’ve missed out on all of this,” Deb said. “Sometimes the scariest decisions are the ones that lead you home.” A passion for community

Matt considers Owatonna his hometown, even

LEFT: Downtown business owners, including Deb and Matt Gillard of RE/MAX Venture (second and third from the left), throw dirt in solidarity at the groundbreaking ceremony for three major downtown Owatonna projects that began in June. (File photo - Owatonna.com) RIGHT: RE/MAX Venture owners Matt and Deb Gillard have participated in the downtown spring cleaning event since 2016, providing lunch for ALC students after the service day. (File photo - Owatonna.com)

though he grew up in West Concord.

“All our friends are here, our family is here,” he said. “We have no plans on moving.”

Deb, originally from Columbia Heights, found herself unexpectedly drawn to Owatonna’s charm. She moved for a job in broadcasting, and legendary local radio host Todd Hale helped her settle in.

“Todd invited me to everything — plays, fireworks, holidays,” Deb said. “It felt more like home right from the get-go.”

Her love for theater and community blossomed from those early invitations. She acted, worked backstage and eventually became deeply embedded in local causes.

“That’s what we tell people who come to work with us,” she says. “Find your thing. Get involved. That’s how you really become a part of this town.”

Matt and Deb’s shared love for giving back became the foundation of their relationship and business philosophy.

“Giving is our way of paying rent for the place we live,” Matt said. “Whether it’s your time or your money, it’s important.”

That mindset was front and center nearly 20 years ago when devastating floods hit the area. Together with friends and neighbors — including many graduates from the Owatonna Community Leadership Academy — organized fundraisers to support those affected.

“We just jumped into it,” Matt said. “And it changed our lives.”

One of the Gillards’ deepest passions is supporting Owatonna’s Area Learning Center students — kids who are too often dismissed or misunderstood.

“They’re not bad kids,” Matt said. “They’re kids who’ve been dealt tough hands.”

He recalls one student standing up during an OCLA session and explaining her daily routine: getting siblings ready, feeding them, going to school, then working late.

“She was just doing what she had to do,” Matt said.

That moment cemented their commitment.

“We realized, if no one is telling these kids they matter, how can they believe it?” Deb said. “Everyone deserves to feel seen, appreciated and given a chance.”

“It just takes one adult believing in them,” Matt said. “One ‘I see you’ to change the course.”

That belief is the driving force behind the Gillards’ support of Owatonna’s ALC students — not just in word, but in deep, consistent action. And one of the biggest ways they show up for these students is during the Downtown Cleanup — a cornerstone community event every spring where the ALC students come out in full force to help beautify the entire downtown district.

As a “thank you” to these kids, the Gillards go out of their way to ensure every student involved feels seen and appreciated. That means collecting donated giveaway items from other downtown business owners so every kid walks

Matt Gillard accepts the Small Business Live United Award on behalf of he and his wife, Deb, along with the RE/MAX Venture Agency. (File

away with something — from earbuds and snacks to gift cards and gear.

But the real prize isn’t something they can carry home. It’s the smell of burgers on the grill, the laughter echoing through Central Park, and the quiet joy of being recognized and appreciated.

One of the event’s most beloved traditions is the post-cleanup cookout, where Matt joins longtime beloved volunteer Vern White behind the grill.

“Grilling with Vern is one of the highlights of my year,” Matt said with a grin. “The kids work hard — they deserve to be celebrated.” For the students, it’s more than a “thank you.” It’s a chance to be part of something bigger, to feel a sense of pride and ownership in their town.

“We want to acknowledge them and say “thank you,’ because that increases the chances

CONTINUED ON PAGE 22

of them going forward in their life and continue to do good things,” Deb said. “Who doesn’t like to feel someone appreciated what you did there?”

“If you’ve been beat down, why have confidence?” Matt added. “It just takes someone to give a little bit to these kids to give them that confidence they need and they deserve.”

The Downtown Cleanup has become a powerful way to deliver that message. It’s not just about picking up litter, it’s about students reclaiming ownership of their community and seeing firsthand that they matter. That their hands, their effort, their presence, makes a difference.

The Downtown Cleanup isn’t the only way the Gillards have been deeply invested — literally and emotionally — in Owatonna’s downtown. Matt served over a decade on the Owatonna Planning Commission, while Deb currently serves as the Board Chair for the Owatonna Area Chamber of Commerce and Tourism. And both of them have been strong advocates for progress-driven projects such as the streetscape project and the riverfront development.

“It takes people like us to care for our 22-feet of downtown,” Matt said, referring to the frontage of their real estate office. “We plant flowers, we keep it clean. It matters.”

They believe downtown is more than just a place — it’s a symbol of a community’s values.

“It’s the beating heart,” Deb said. “If you take care of that, everything else can grow from there.”

Of course, their commitment to Owatonna stretches well beyond downtown. For Matt and Deb, leadership is quiet, consistent and rooted in action. They don’t seek the spotlight — but it often finds them.

From co-founding Alzheimer’s caregiver support groups — after Deb lost her dad to the disease — to mentoring young professionals, they lead by showing up, listening and building bridges.

Deb is quick to admit she’s learned to say no when needed.

“I used to say yes to everything. Now I ask myself: Can I give this the time it deserves? If not, maybe I know someone who can.”

Their real estate business has given them a front-row seat to Owatonna’s growth — and its growing pains.

“When clients come looking for a home, they ask about schools,” Matt said. “Not just because of kids, but because it’s a sign of a healthy, cared-for community.”

That’s why they supported the new high school referendum, even when it was somewhat controversial.

“It’s the only ‘political’ stance we’ve taken,” Matt said, noting if a community doesn’t invest in their youth then the future will be uncertain. “We are big believers and supporters in the whole city growing.”

The Gillards’ commitment to Owatonna doesn’t end at business hours — it’s woven into nearly every corner of the community. Matt, a longtime real estate professional, has brought his industry expertise to the Minnesota Real Estate Professional Standards Board, the Southeast Minnesota Realtors MLS Board, and served as a Children’s Miracle Network Miracle Agent, donating a portion of every sale to support children’s hospitals. His civic service also includes time on the Steele County Planning Commission, and early involvement

in the Owatonna MainStreet Committee and Save the State Theater Taskforce. His passion for local business and community collaboration also led him to serve on the Foremost Brewing Cooperative Board.

Deb, equally invested in the town’s future, has led with heart and strategy. In addition to her other volunteer work, she also serves as a trustee for the Owatonna Foundation and brings her marketing expertise to the Steele County Historical Society. Like Matt, she is a Miracle Agent and alum of the Owatonna Community Leadership Academy, an experience they both credit as transformational. Together, they’ve become pillars in programs like Big Brothers Big Sisters as a Big Couple,

the Owatonna Business Partnership and the Owatonna Foundation Legacy Society. They regularly participate in Community Pathways of Steele County donation drives and supporting events like the Give Hope Concert.

RE/MAX Venture was also honored as the 2022 United Way Small Business of the Year — a reflection of how deeply their business philosophy is tied to community impact.

With grandchildren in town, a thriving downtown just blocks from home and deep ties to local boards and causes, the Gillards aren’t going anywhere.

“There’s something special happening in Owatonna,” Matt said. “We’re growing in a way that includes everyone. That’s the kind of place we want to live.”

They dream of more restaurants, more riverfront housing, more families walking down beautifully maintained streets. But more than that, they want to keep showing others that community isn’t something you consume — it’s something you build.

“Most of us can’t save the world, but we can do good right here,” Deb said. “One person at a time.”