OUR PARKS LANCASTER

CITY OF LANCASTER

COMPREHENSIVE PARKS, RECREATION & OPEN SPACE PLAN 2024

CITY OF LANCASTER

COMPREHENSIVE PARKS, RECREATION & OPEN SPACE PLAN 2024

LANCASTER DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS

Steve Campbell, Director

Cindy McCormick, Deputy Director, Engineering

Karl Graybill, Environmental Planner

Emma Hamme, Transportation Planner

Ryan Hunter, Facilities Manager

LANCASTER DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNITY PLANNING & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

Chris Delfs, Director

Molly Kirchoff, Program Manager, Public Art and Urban Design

LANCASTER RECREATION COMMISSION

Heather Dighe, Executive Director

LANCASTER COUNTY

Michael Domin

Alice Yoder

RESIDENTS & STAKEHOLDERS

Adriana Atencio

Chris Aviles

Kareema Burgess

Erin Conahan

Tene Darby

Tim Freund

Zeshan Ismat

Rob Reed

Melissa Ressler

Karen Schloer

John Hursh

Jeremy Young

Christine Mondor, FAIA

Claudia Saladin, ASLA

Ashley Cox, AICP

Varun Shah

WSP

Robert Armstrong, PhD., CPRP

Connect the Dots

Sylvia Garcia-Garcia

Sophia Peterson

Stephanie Fuentes

Julia Whyte

Merritt Chase

Danica Liongson

This report has been made possible with funding from: The City of Lancaster and

This project was financed in part by a grant from the Community Conservation Partnerships Program, Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund, under the administration of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation.

A Comprehensive Parks Recreation and Open Space Plan or CPROS is a plan for the future. It guides investment in park development, maintenance, and connectivity to better serve the recreational needs of residents. In addition to focusing on the physical amenities of parks, this plan re-envisions the city’s parks and open spaces as an interconnected system and prioritizes how to equitably expand and build connections within the system. The objective of Lancaster’s 2024 CPROS plan is to increase accessibility to recreational amenities and natural areas in a way that is fair, equitable, and safe. Through research, analysis, and public engagement, the City of Lancaster has developed this plan to make the Lancaster Parks System the best it can be. It identifies policies, resources, and capital investments needed to accomplish long-term and short-term recreation and green space conservation goals. This document is a summary of the plan’s recommendations.

The Lancaster park system is approximately 212 total acres The system is maintained by the Bureau of Parks and Public Property within Department of Public Works. The main responsibility for programming the parks lies within the quasi-governmental nonprofit Lancaster Recreation Commission. Lancaster Recreation Commission provides programming for the City of Lancaster, Lancaster Township, and the School District of Lancaster. Numerous nonprofits also activate the parks with programming. In addition to parks owned by the city, Lancaster residents also have access to public parks in the county and neighboring jurisdictions. Many school district properties have recreational facilities that are open and available for public use. Additionally there are privately owned open spaces; while there is not a standard definition of open space the US Forest Service states: “Open Space refers to any open, undeveloped piece of land. Open space includes natural areas such as forests and grasslands...parks, stream and river corridors, and other natural areas within urban and suburban areas. Open space lands may be protected or unprotected, public or private.” For the purposes of this document, Cemeteries have been categorized as private open spaces.

Compared to national benchmarks, Lancaster’s park system has approximately one third the area, and is understaffed, particularly in terms of programming staff; spends less per capita than regional peer cities, and is below the national median for spending when compared to cities of similar size. Lancaster’s park system was developed opportunistically over time as parcels became available and has lacked a cohesive plan for the park system. Many of the parks are small, and some neighborhoods, particularly in the southeast of the city, are poorly served. Because Lancaster is a dense city with relatively little vacant land, the opportunities to increase the park system area, and natural open space are limited. This plan provides an overview of the system and recommendations for targeted improvements.

NORTHWEST & NORTHWEST EXTENSION

• Buchanan Park

• Mayor Janice Stork Linear Park

• Rotary Park

• North Market Street Kids Park

• Blanche Nevin Park

• CANBA Park

• Long’s Park NORTHEAST & NORTHEAST EXTENSION

• Musser Park

• Triangle Park

• Sixth Ward Park

• Reservoir Park

• Conestoga Pines Park

DOWNTOWN

• Binns Plaza

• Penn Plaza

• Ewell Plaza

SOUTHWEST

• Culliton Park

• Brandon Park

• Rodney Park

• Crystal Park

• South End Park

• Cabbage Hill Veterans Memorial SOUTHEAST & SOUTHEAST EXTENSION

• Milburn Park

• Case Commons

• South Duke Street Mall

• Joe Jackson Tot Lot

• Ewell Gantz Playground

• Holly Point Park

• Lemon Street Parklet

• Conestoga Creek Park

• Lancaster Central Park

• Lancaster Community Park

• Buchmiller County Park

• Stauffer Park

• Conestoga Greenway Trail

• Farmingdale Trails

• Noel Dorwart Park

• Hazel Jackson Woods

• Holly Pointe Greenway

• SoWe Pocket Park

• School District Campus (McCaskey)

• Reynolds Middle

• Jackson Middle

• ML King, Jr. Elementary

• Washington Elementary

• Price Elementary

• Lafayette Elementary

• Hamilton Elementary

• Wharton Elementary

• Ross Elementary

• St Mary’s

• Lancaster Cemetery

• St James Cemetery

• Shreiner’s Cemetery

• St. Josephs’ Church Cemetery

• Woodward Hill Cemetery

• Cedar Lawn Cemetery

• Greenwood Cemetery

• Riverview Burial Park

The following recommendations are based on the needs identified through the public engagement process and the consultant team’s analysis of the existing park system.

All parks need to be updated from time to time. Lancaster recently completed a process called “Facilities Condition Assessments” (FCAs) for all of its parks. The FCAs identifying needed repairs in all parks, including repairing or replacing equipment, replacing worn safety surfaces in playgrounds, and making parks more ADA accessible. In addition to these needed repairs, the following projects are recommended:

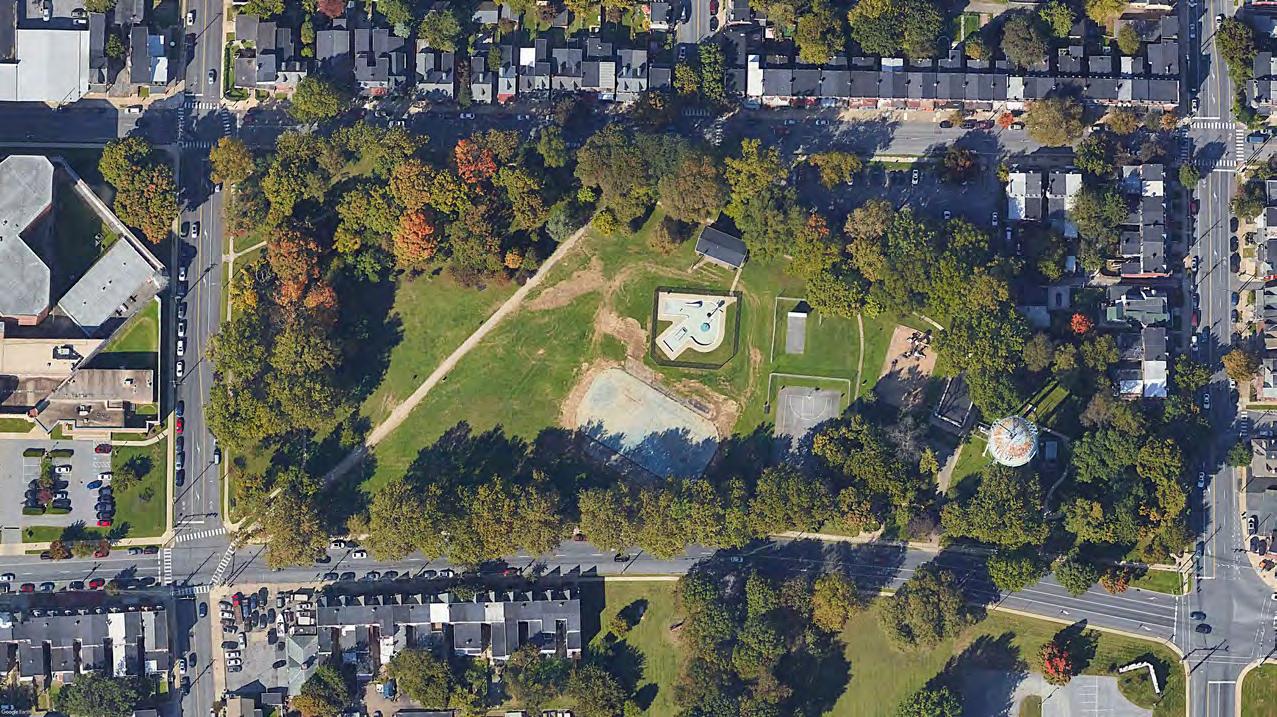

Reservoir Park is one of the largest and oldest parks in Lancaster. While it is a great park, it needs an update and master plan that will incorporate the many uses in the park. Planning for Reservoir Park should be done in conjunction with the East End Small Area Plan, that will occur around the redevelopment of the County Prison property. Reservoir Park and the prison site are potential locations for some of the new facilities discussed below. The plan should carefully balance the competing uses on the Reservoir Park site, including its use for community fairgrounds, and other recreational activities.

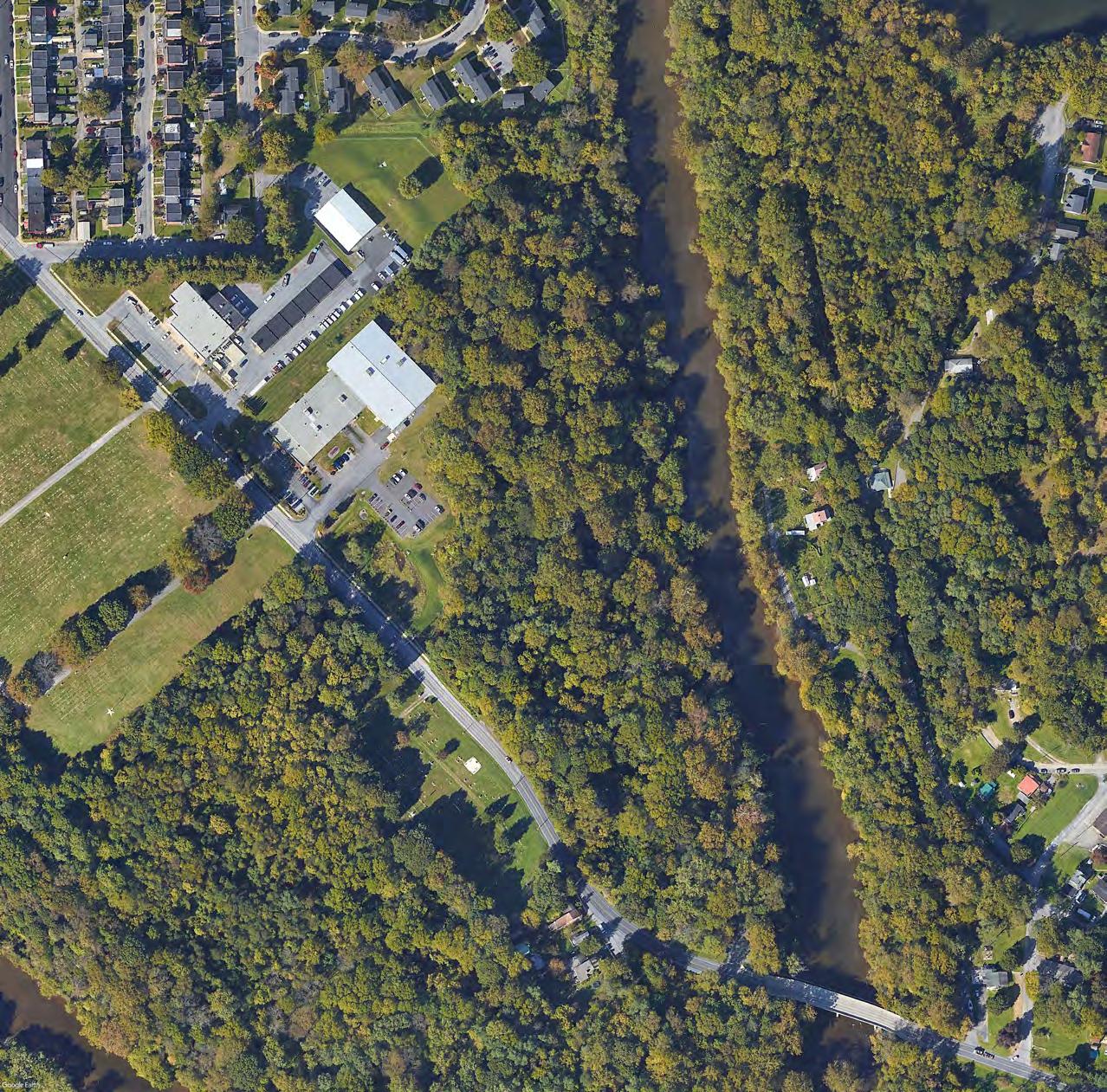

Conestoga Pines Park has been the subject of a separate master planning process. Implementation of the recommendations of that plan, including providing greater access to the Conestoga River, improvements to the barn, and addressing the aging pool currently located in the floodplain, should continue along the schedule laid out in that plan

Converting wading pools to spray parks in existing parks provides many benefits. They are less costly to maintain, are more accessible for users of all abilities, and because they have no standing water, require less staffing. Spray parks can operate longer hours and across a longer season.

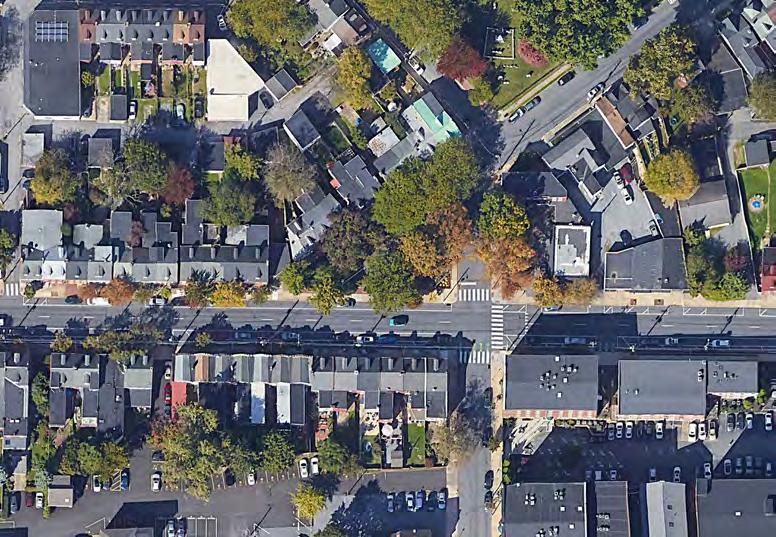

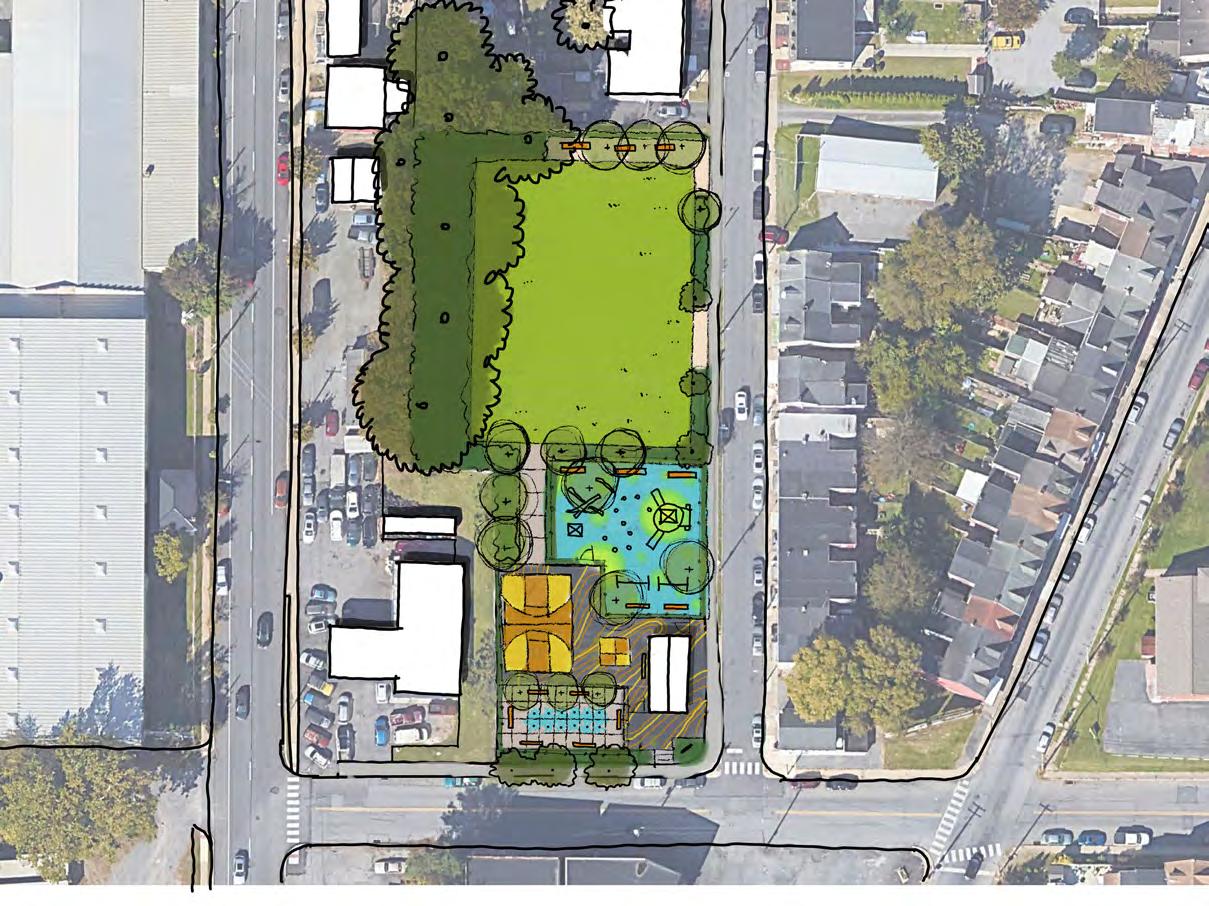

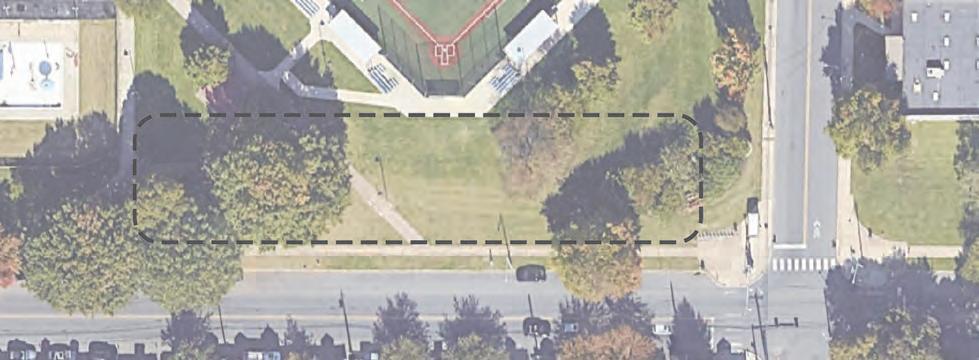

Some parks in the southern part of the city are in dire need of upgrades. These include Joe Jackson Tot Lot, Ewell Gantz Playground, South End Park, and the South Duke Street Mall. Planning and fundraising for upgrades in these parks has already begun. Investments in these parks should be a priority as they will help bring modern amenities to areas of the city that are currently underserved.

Across the system, improved infrastructure could catalyze increase use of the parks. Improving shade by planting new trees and succession planting for older trees; amenities such as water fountains and bottle filling stations, lighting, access to electricity for events, and restrooms, are items that allow people to use parks more frequently and for longer periods of time.

Through the planning process, needs for additional facilities were identified.

A new Municipal Pool. The pool at Conestoga Pines is reaching the end of its useful life, is located in a flood plain, and is not easily accessible without a car. The High School pool, which in the past was used for lifeguard training, is now closed. Lancaster needs a new municipal pool that can accommodate many activities, such as swim lessons, lifeguard training, water aerobics, be ADA accessible, and more centrally located. Possible locations include Reservoir Park or the County Jail Site.

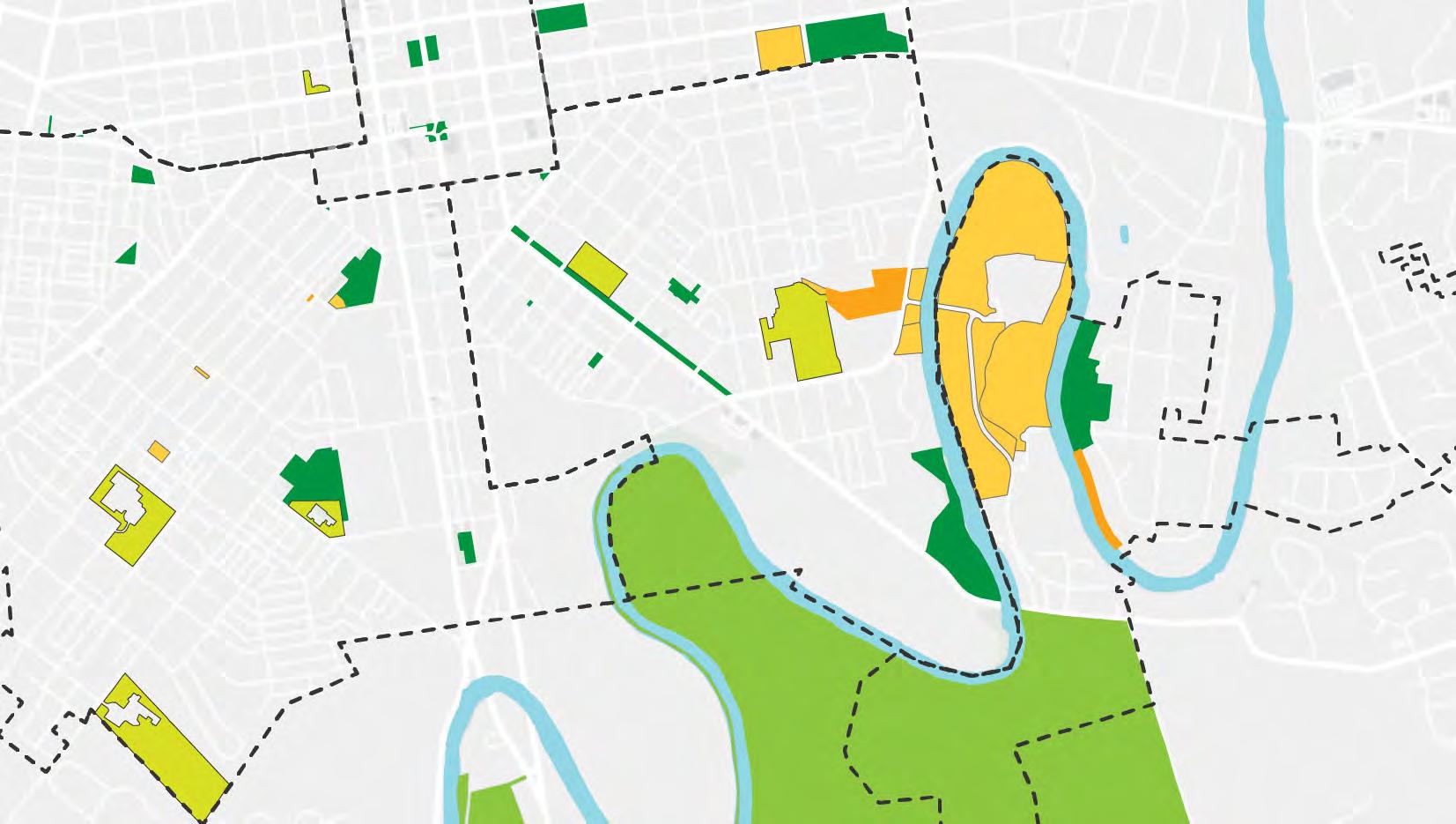

Sunnyside Peninsula was envisioned in the Our Future Lancaster Plan as a nature reserve and park, providing environmental education programming, an opportunity to connect with nature, and greater access to the Conestoga River. A park on Sunnyside Peninsula would create more access to parks for city residents. Planning on this park has already begun. The need for skate parks was identified through the engagement process. Possible locations include Reservoir Park or on city-owned property adjacent to Culliton Park. Design and implementation of a Skate Park should involve a partnership with the skating community to avoid the design challenges of the existing skate park in County Park, which is not preferred by skaters.

An off-street bicycle track or pump track was also identified as a need to allow for safe places to learn and practice bicycle skills and tricks. A future pump track should be located close to cycling infrastructure, for example, adjacent to the Water Street Bicycle Boulevard. In conjunction with converting wading pools to spray parks, additional spray parks could be added to existing parks that do not have wading pools.

This would help provide water play and cooling for users across the city, especially important in a densely populated city, such as Lancaster, where many older buildings do not have air conditioning.

Pickleball is gaining popularity as a sport, particularly among seniors, which is a growing demographic in Lancaster. Tennis courts can often be converted into pickleball courts with minimal investment. Pickleball courts can also be built as temporary installations to test locations.

Natural play areas, which incorporate natural elements into outdoor spaces, could be incorporated into the Sunnyside Peninsula Park with its focus on environmental education, or added to existing parks where there is space and community interest.

The City of Lancaster is deeply committed to public engagement. The city has identified several ways to better engage the community around parks, improve the park experience for all, and encourage park use and volunteerism.

Park ambassadors or rangers would welcome visitors to the parks, educate the public on park rules, and be the eyes and ears on the ground to identify ongoing issues. They could assist staff with opening and closing gates and restrooms and ideally extend the hours of restroom operation.

Stewardship and recreation coordinators would help to coordinate volunteer engagement in the parks and communicate and coordinate the activities of nonprofit organizations operating in the parks to ensure that all areas of the city are served.

A landscape workforce and greenhouse would support the city’s parks and green infrastructure, and could also help support community gardens.

A comprehensive, multilingual signage program, including system-wide mapping, consistent park signage in multiple languages, and education handouts for users, would help to promote the park system and make it welcoming to all. Such a resource would also inform people about the entire park system and connections between the parks.

Lancaster’s Vision Zero Program has focused on creating safe streets for all, focusing on the most dangerous streets and intersections. The Vision Zero Program complements the parks plan by providing safer routes to parks. Particularly important improvements for park connectivity include the South Duke Street corridor, improved connection to Lancaster County Central Park at Strawberry Street, and connections to a future Sunnyside Peninsula Park and Conestoga Greenway Trail at Circle Avenue.

The project goals guide how this plan is rethinking the city parks and open spaces as one integrated system. The consultant team worked with the City of Lancaster and the steering committee to develop a set of goals for the Comprehensive Parks, Recreation, and Open Space Plan.

Incorporate environmental sustainability, green infrastructure, and climate resilience into parks and open spaces.

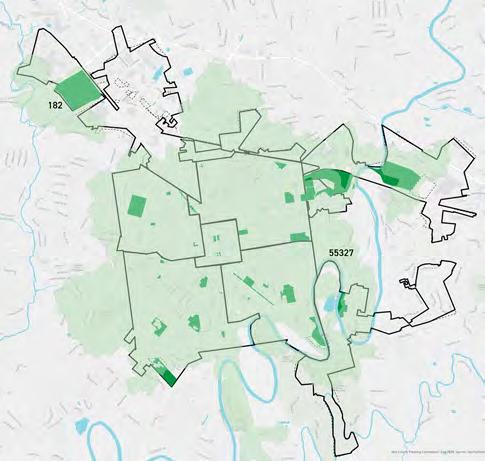

Ensure that all residents are within a safe 10-minute walk of a “high quality” park.

Increase connectivity of parks and open spaces to enhance accessibility and safety for active transportation mobility.

Prioritize park and open space projects that improve accessibility for people of all ages and abilities and emphasize inclusivity and equity.

Increase adaptability of parks and open spaces to accommodate current and future needs.

Establish a plan for long-term sustainability of the city’s public spaces to address resiliency, maintenance, programming, funding, and upgrades.

The Lancaster Parks Recreation and Open Space Plan is the result of a robust analysis of the existing park system and community engagement.

The Introduction & Context chapter provides a community profile, a short history of Lancaster’s park system, a review of past and ongoing plans in the City of Lancaster, a discussion of the various benchmarking standards used to evaluate the system, and an introduction to the many types of parks in Lancaster’s system. This section also describes the public engagement methodology used in the project and presents the City of Lancaster’s mission statement developed during the planning process.

The System Analysis chapter analyzes the park system of the City of Lancaster. This analysis includes an understanding of the city administration, recreation services, benchmarking of staffing and budget to national and regional benchmarks, as well as the physical system of parks and open space. The recreational facilities available to Lancaster residents were benchmarked, the quality of individual parks assessed, and the distribution of parks and amenities across the system evaluated. The connectivity of the system was then reviewed, building on the important work Lancaster is doing on Vision Zero and active transportation. This chapter provides details on each of the parks in the system.

The Recommendations chapter presents the recommendations developed based on the findings of the system analysis and input from the public. The development of the recommendations was guided by the National Recreation and Parks Association’s pillars of equity, health and wellness, and conservation and sustainability, as well as Lancaster’s goals of stewardship and maintenance, engagement and participation, and leadership. The recommendations include improvements to individual parks, new types of facilities, and improvements across the system in infrastructure, workforce, signage, and policy.

The Implementation Plan chapter prioritizes the recommendations based on community priority, equity, technical need, and cost. It organizes the recommendations into three tiers. Within each tier, it identifies project considerations, funding sources, and project phasing for each of the recommendations.

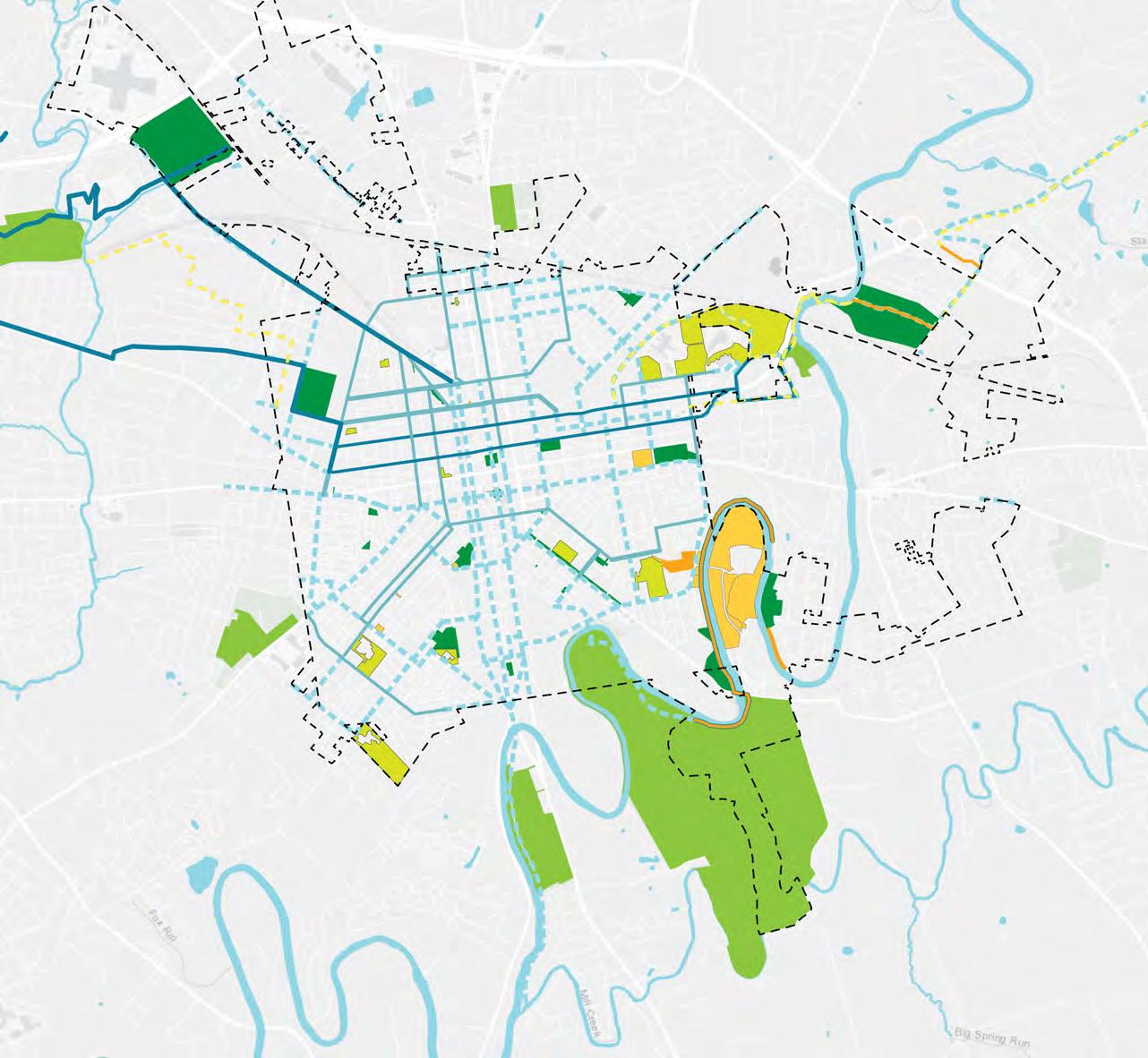

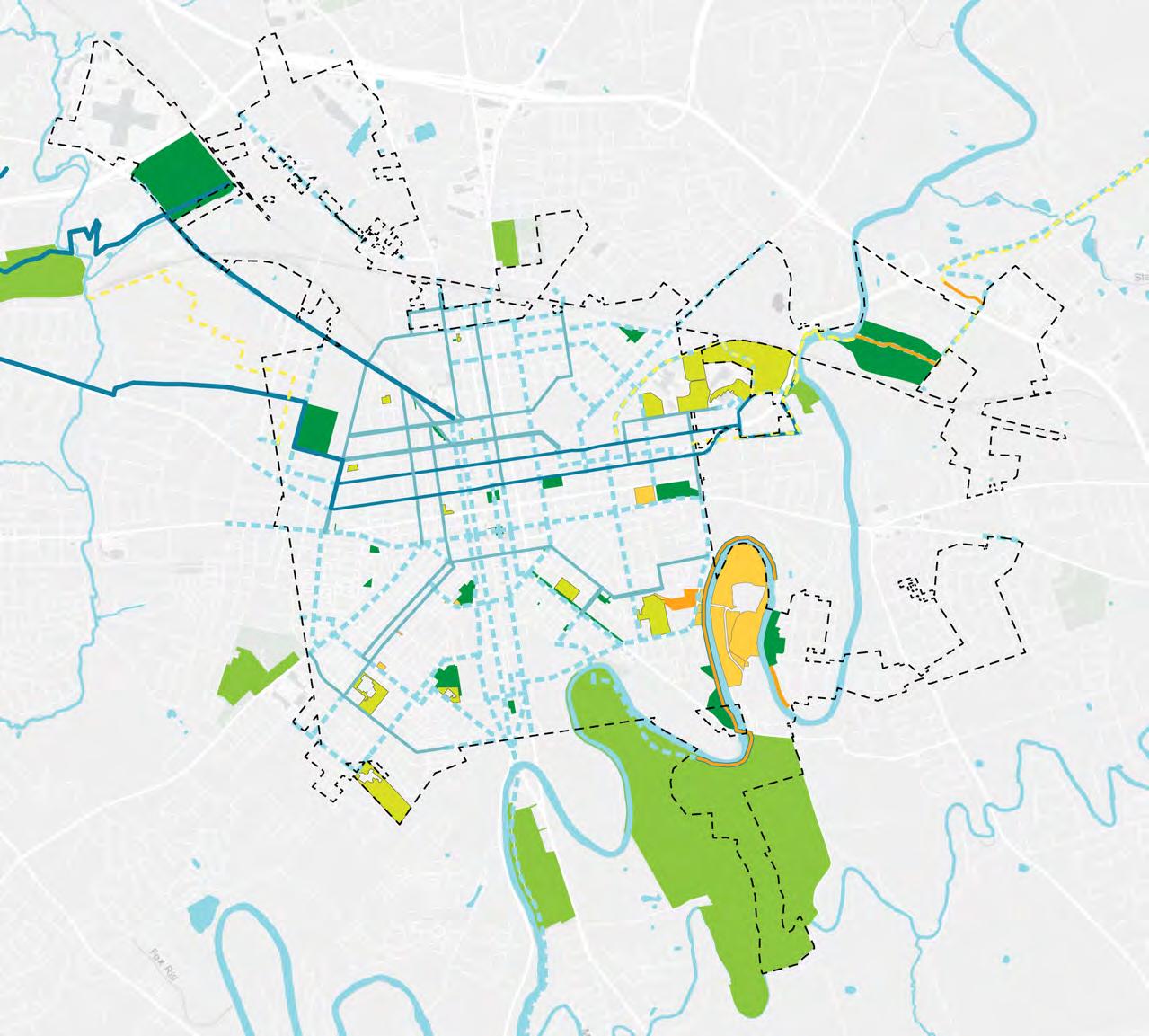

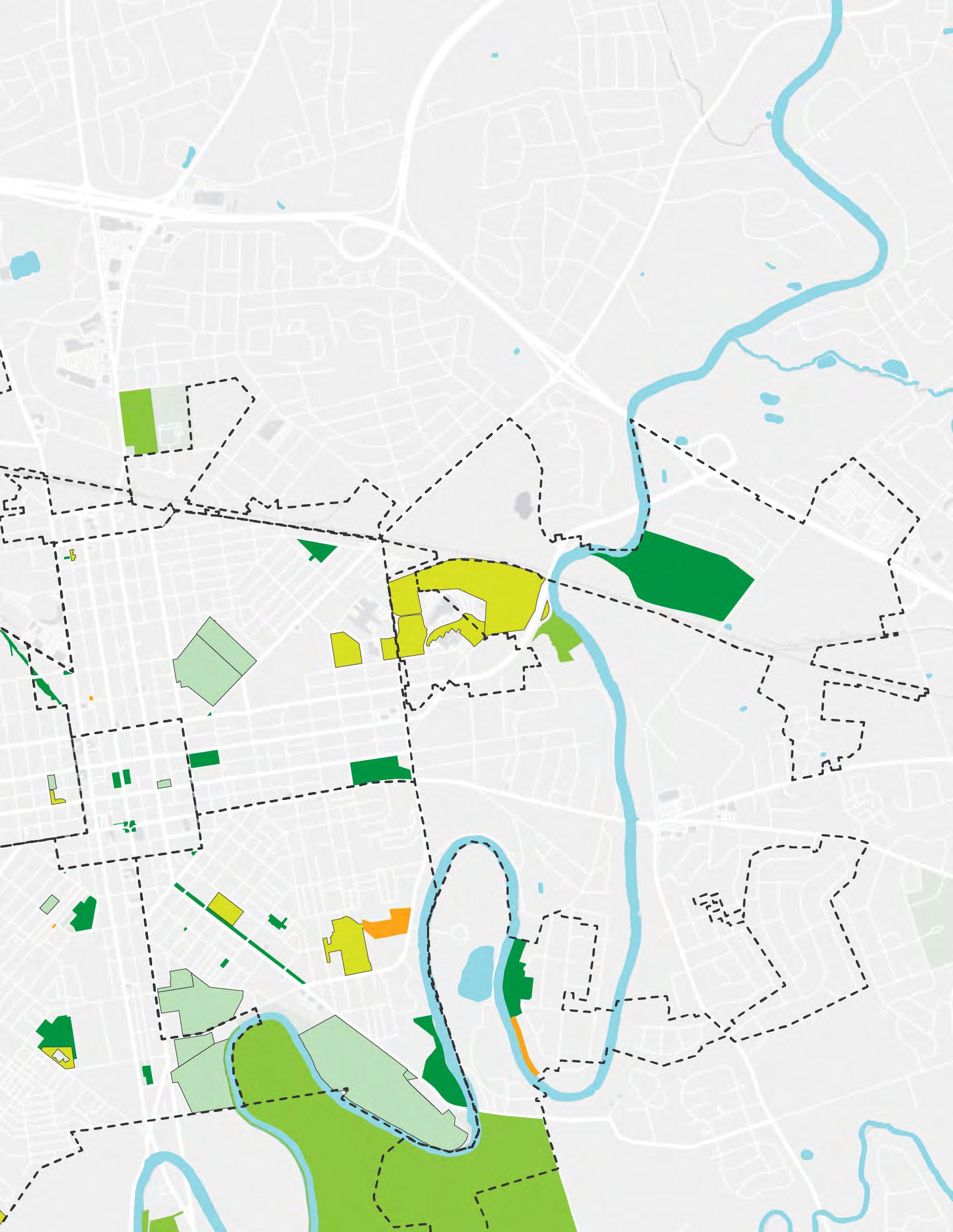

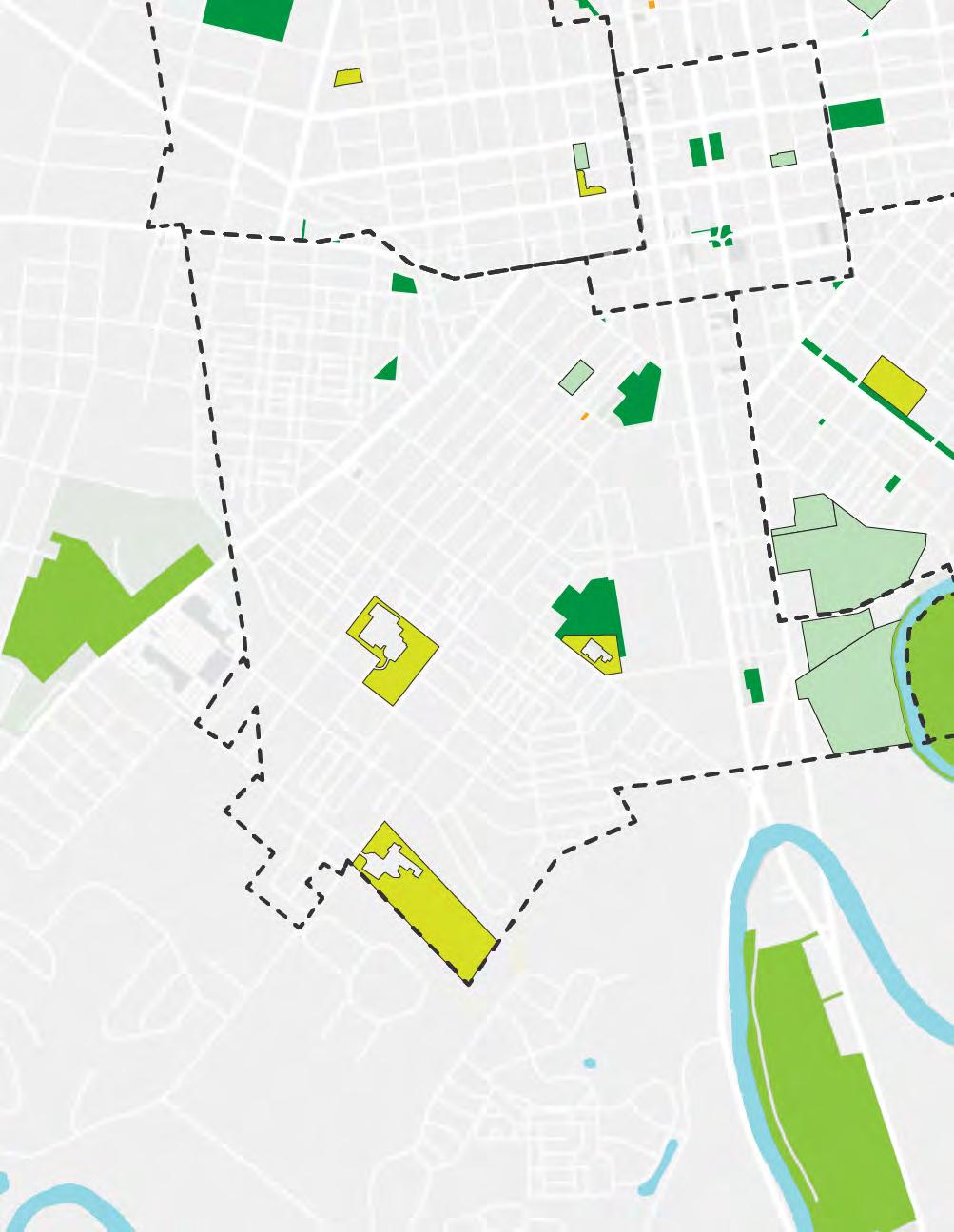

City Parks

Other Parks

School District Properties (open to the public)

Cemeteries (private)

Other Open Spaces (private)

Publicly-owned Opportunity Sites

Existing trails

Existing bike facilities

Regional trail connections

Proposed trails

Proposed bike facilities

Proposed Riverfront trail

A Comprehensive Parks Recreation and Open Space Plan or CPROS is a plan for the future. It guides investment in park development, maintenance, and connectivity to better serve the recreational needs of residents. In addition to focusing on the physical amenities of parks, this plan re-envisions the city’s parks and open spaces as an interconnected system and prioritizes how to equitably expand and build connections within the system. The objective of Lancaster’s 2024 CPROS plan is to increase accessibility to recreational amenities and natural areas in a way that is fair, equitable, and safe. Given the focus on equity, equity-related challenges and considerations have been address and recommendations integrated throughout every section of the CPROSP

Through research, analysis, and public engagement, the City of Lancaster has developed this plan to make the Lancaster Parks System the best it can be. It identifies policies, resources, and capital investments needed to accomplish long-term and short-term recreation and green space conservation goals. This document is a summary of the plan’s recommendations.

The project goals guide how the plan is rethinking the city parks and open spaces as one integrated system. The consultant team worked with the City of Lancaster and the steering committee to develop a set of goals for the Comprehensive Parks, Recreation, and Open Space Plan.

Incorporate environmental sustainability, green infrastructure, and climate resilience into parks and open spaces.

Ensure that all residents are within a safe 10-minute walk of a “high quality” park.

Increase connectivity of parks and open spaces to enhance accessibility and safety for active transportation mobility.

Prioritize park and open space projects that improve accessibility for people of all ages and abilities and emphasize inclusivity and equity.

Increase adaptability of parks and open spaces to accommodate current and future needs.

Establish a plan for long-term sustainability of the city’s public spaces to address resiliency, maintenance, programming, funding, and upgrades.

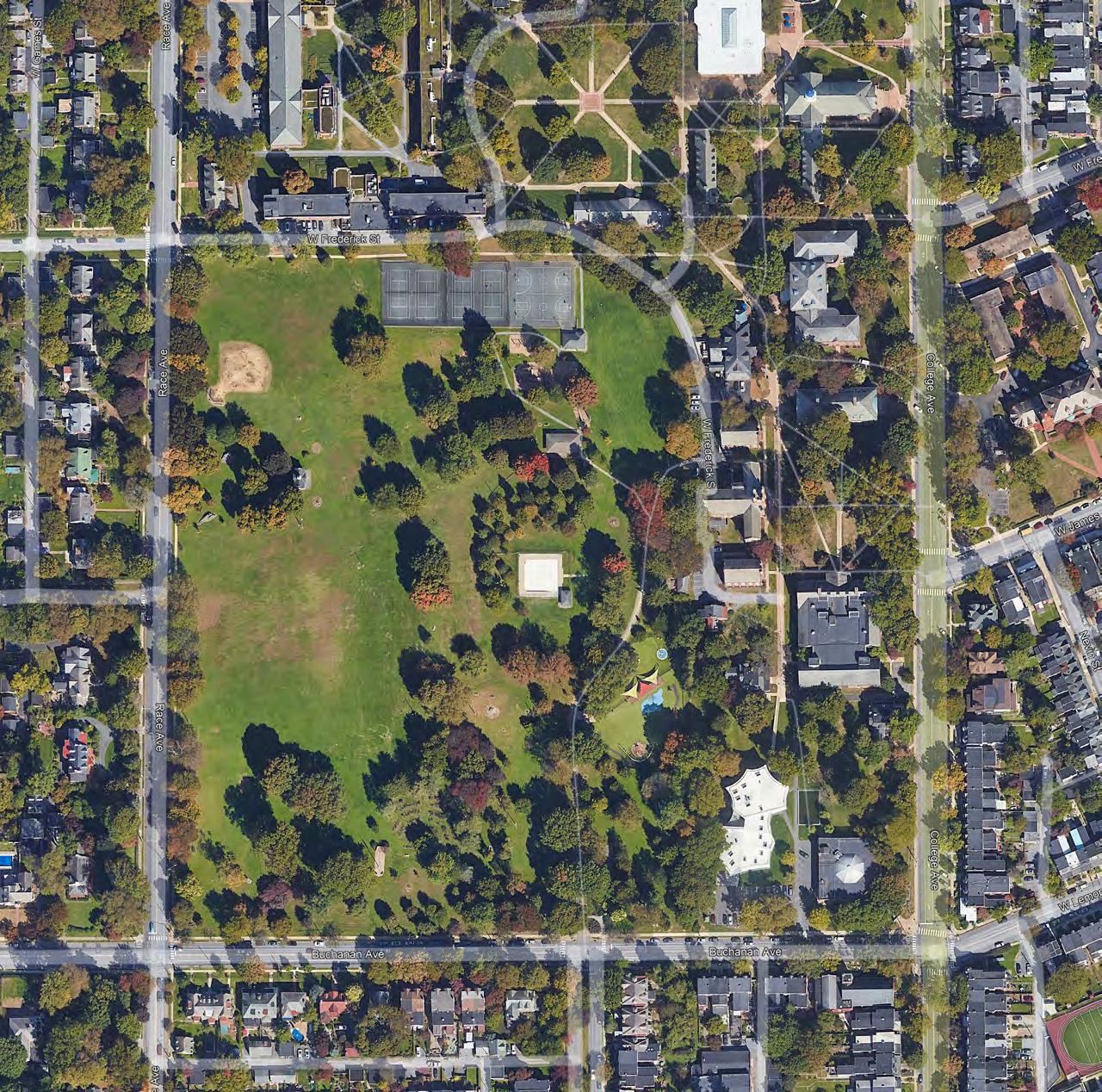

The City of Lancaster, located in South Central Pennsylvania and founded in 1730, is important both historically and culturally to the region, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the Nation. In 2001, the City of Lancaster Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places with over 13,000 contributing properties, encompassing almost the entire historic city boundary. With a period of significance of 1760-1950, the City of Lancaster is one of the oldest and most historically important places in all of Pennsylvania.1 Three main parks referenced in the City of Lancaster Open Space Plan Request for Proposals are listed as contributing properties to the National Register: Musser Park in the northeast of the Central Business Area, Buchanan Park in the northwest, and Reservoir Park in the east. In addition, 12 of the small playgrounds and pocket parks are located within the boundaries of the historic district.2

The City of Lancaster has a long history as the center of commercial, industrial, and governmental affairs in Lancaster County. Lancaster was the capital of Pennsylvania from 1799 to 1812 before it moved to Harrisburg. Its proximity to Philadelphia and its importance as an inland market center allowed the city to grow as a cosmopolitan center from the 18th century well into the 20th century. Linked first by the 62-mile Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike, completed in 1795, and later by railroads, the transportation network connected the agricultural marketplace of Lancaster with Philadelphia, one of the nation’s most important commercial and intellectual centers since colonial times.

After World War II and especially after 1960 and lasting into the end of the 20th century, Lancaster began to lose population to its burgeoning suburbs, especially Manheim Township to the north of the city (location of Stauffer Park) and Lancaster Township to the west of the city (location of Lancaster Community Park). The construction of suburban developments on farmland located just outside

1 For the City of Lancaster Historic District National Register Nomination see: https://www. cityoflancasterpa.gov/the-national-register/

2 Ibid, page 9 (Section 7, page 2)

the city limits and suburban shopping centers and malls with ample parking in the mid-20th century drained the vibrant nature of the downtown business district. Urban renewal changed the character of much of downtown Lancaster in the 1960s and 1970s in an attempt to solve the problems of parking, congested streets, and housing for its economically disadvantaged residents.3 The remnants of urban renewal can be seen in the design and location of the South Duke Street Mall, for example, with the adjacent public housing fronting along Rockland Street and along North Queen Street where the former Lancaster Square urban renewal project has been transformed into Binns Park and Ewell Plaza.

The 21st century has seen a resurgence in Lancaster as art galleries, restaurants, and shops have opened and the downtown is once again a destination, even during the pandemic era. Population loss seems to have plateaued and the city is attracting new residents. Adaptive reuse saved many historic buildings from demolition, particularly in the older industrial area located in the northwest section of the city. Unlike other cities, Lancaster has retained much of its historic fabric, although preservation of the historic environment remains a challenge. Lancaster has one of the most diverse populations of any smaller city in Pennsylvania, boasting a large population of Puerto Rican descent as well as an established African-American community. The city is poised to continue to thrive, especially by connecting its residents to the many parks, open spaces, and cultural and historic sites scattered throughout this important, historic place.

3 For a discussion of Urban Renewal in Lancaster see David Schuyler’s “Prologue to Urban Renewal: The Problem of Downtown Lancaster, 1945-1960.” file:https://journals.psu. edu/phj/article/view/25117/24886

Public space in Lancaster originated in Penn Square, as laid out by James Hamilton in the mid-1730s. Originally named Centre Square, the square was the site of the County Courthouse and sat at the center of the grid pattern Hamilton used for the city Plan, which is similar to Philadelphia’s. This would remain Lancaster’s only public space until almost 180 years later. While there was much public interest in parks in Lancaster during the mid-to-late nineteenth century, the city did not have any substantial public spaces for its residents. In 1892, the Lancaster Intelligencer stated that “When William Penn laid out Philadelphia he made provision for certain parks” while “James Hamilton laid out Lancaster (and) wasted no sentiment on parks for that would have been to throw away real estate with cash value. The spirit of the founder, each his own, seems ever since to have dominated these two cities.”1

It was not until later in the nineteenth century that larger public parks began to become a reality in Lancaster as the East Reservoir, site of

1 “Our Lancaster Parks” 16 April 1892, Lancaster Intelligencer

Reservoir Park, and the West Reservoir, site of Buchanan Park, were both identified as locations for larger parks and were championed by local newspapers. In 1889, land adjacent to the East Reservoir was identified for a public park, however, it would take several years to become a reality.2 In 1900, land that would become Long’s Park was donated, however, at that time it was outside the city limits. In 1905, Buchanan Park was dedicated on the site of the West End Reservoir and remains the largest park inside the original city limits at over 20 acres.

1909 saw the creation of the Lancaster Recreation Commission (originally called the Lancaster Playground Association) and several smaller playground areas were identified throughout the city for recreational purposes. However, many times these areas remained in private ownership and areas once used for recreation were sold off for development as the city’s population swelled in the early twentieth century.

2 “The Park Has Come” 1 June 1889 Lancaster New Era

By the early 1920s, the city began either purchasing or receiving through donation parcels and dedicating them for public use. These included Farnum (now Culliton) Park, Rodney Park, Sixth Ward Park, and South End Park, all acquired during the 1920s and all of which remain parkland to the present day. After many decades without any new land acquisitions during the Great Depression and World War II eras, the city acquired Musser Park through donation in 1949. Crystal Park was dedicated eight years later in 1957.

The mid-to-late 1960s saw the next great expansion of Lancaster’s park system as federal funds became available to acquire land for park purposes during the Urban Renewal period. Conestoga Pines (1966), South Duke Street Mall (1967), Joe Jackson Tot Lot (1968), Conestoga Creek Park (1968), Lancaster Square (1970), and Brandon Park (1971) all were acquired within five years as the city utilized funding to acquire park land and increase recreational activities for its citizens.

Since the late 1960s and early 1970s, the city has acquired key parcels to expand its park and recreational assets through acquisition or donation. These include Triangle Park (1979), Mayor Janice Stork Linear Park (1994), Ewell Gantz Playground (1996), Case Commons (1997) and Holly Pointe Park (1999). The western portion of Lancaster Square was redeveloped as Binns Park in 2005 and the eastern portion was redeveloped as Ewell Plaza in 2022.

Historically, the sporadic and opportunistic process of adding parks and public spaces led to a system that lacks true connectivity and equitable access for city residents. Due to a lack of prioritization and planning over time and rapid development in the early twentieth century as Lancaster became a densely populated city, access to open space became difficult. This made it challenging for open space advocates such as the Lancaster Recreation Commission to gain traction with the city to acquire meaningful land for new parks and recreation purposes.

ALL_Updated

Lancaster City, PA

Lancaster City, PA (4241216)

Geography: Place

According to the US Census Bureau, the City of Lancaster’s population in 2022 was 57,453 with a population density of approximately 8,000 residents per square mile. Lancaster’s population density is greater than much larger cities such as Pittsburgh (approximately 5,400 residents per square mile) and Baltimore (approximately 7,200 per square mile). Lancaster is also more densely populated than other smaller, peer Pennsylvania cities between 50,000 and 100,000 residents such as Harrisburg (approximately 6,000 residents per square mile) and Bethlehem (approximately 4,000 residents per square mile). Lancaster is a multi-racial city with roughly 40% of the population identifying as Latino or Hispanic and 16.5% identifying as Black or African American. The population of foreignborn residents is approximately 12%. Around 19% of the population lives in poverty, roughly 18% are under the age of 18, and about 9% are over age 65.1

Looking forward, it is projected that the City of Lancaster population will grow to 58,392 residents by 2030. The population is then expected to decline to 58,024 residents by 2035 and to 57,656 residents by 2040. Given the relatively small population change expected through 2040, the recommendations made in this report regarding the number of parks appropriate for the City of Lancaster will remain relevant through 2040.”

1

$5,788

2021 Population by Race

2021 Population by Race

2021 Population by Hispanic-Race

Hispanic Population (darker blue color correlates to higher number)

Black Population (darker blue color correlates to a higher number)

Linguistically isolated population (households with out a person 14 yrs. or older who speaks English well) (darker blue color correlates to a higher number)

Population that speaks a language other than English very well (May speak a language other than English at home) (darker blue color correlates to a higher number)

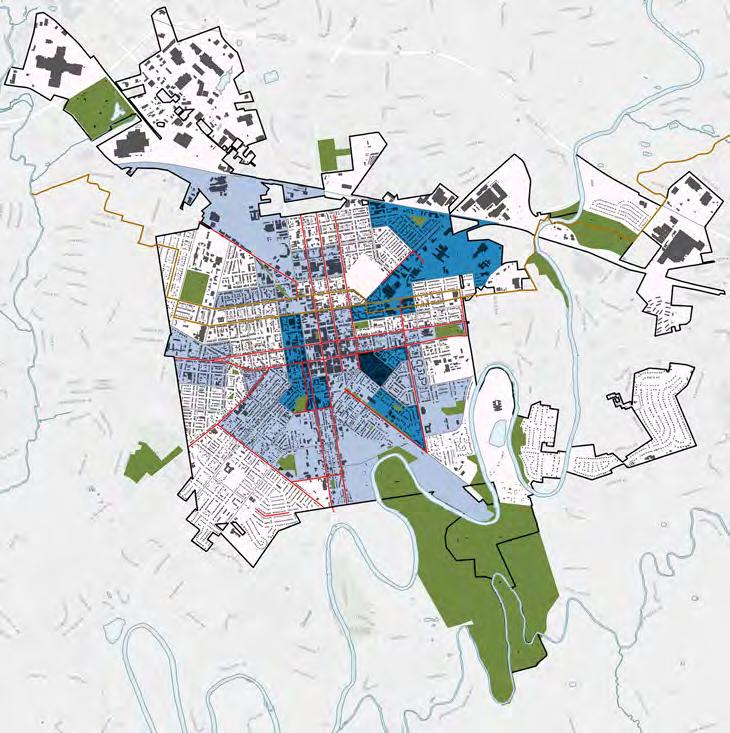

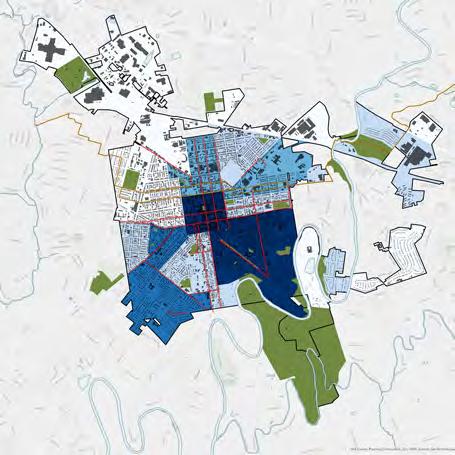

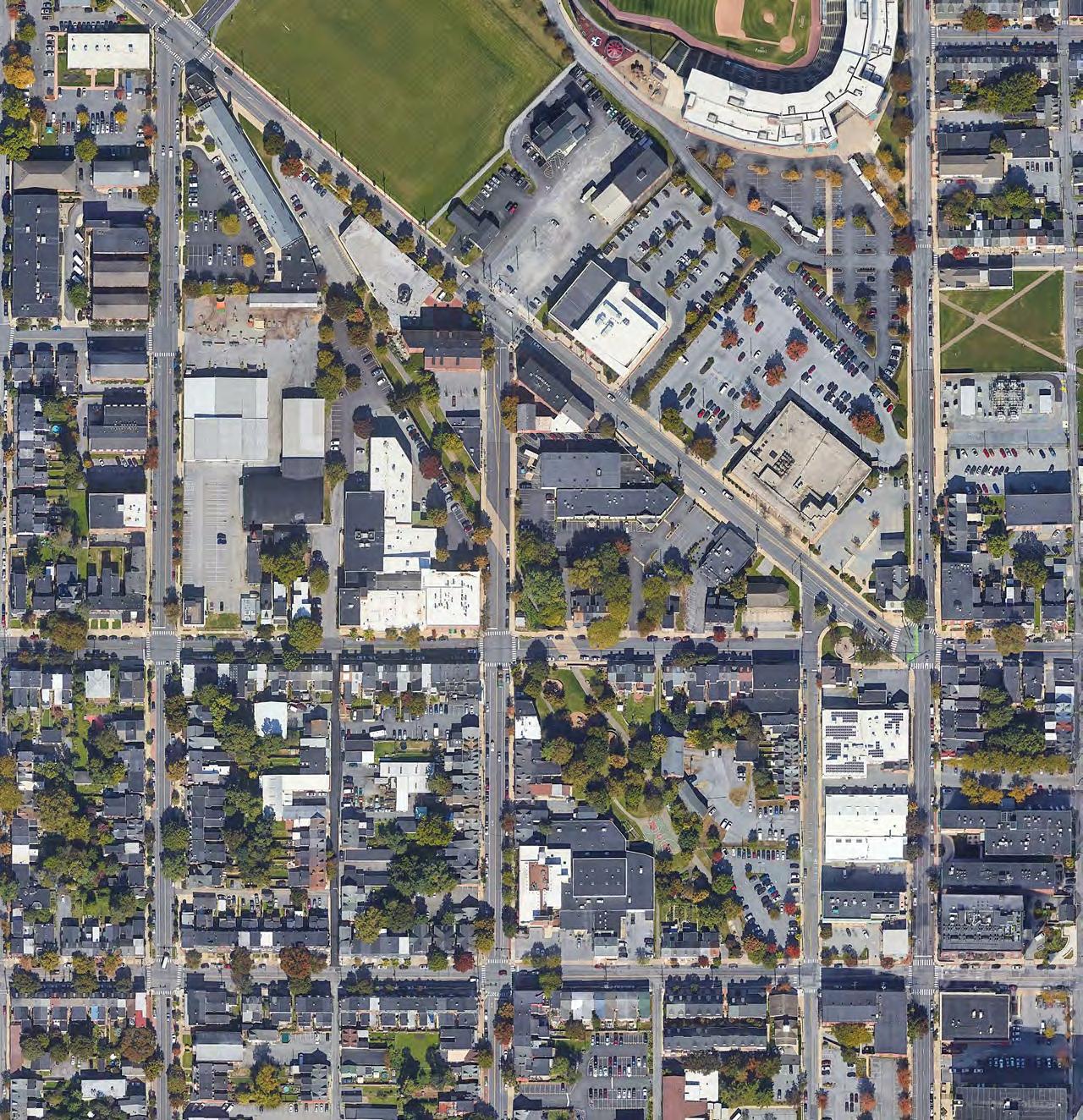

The historic grid of the City of Lancaster is organized into four quadrants: northwest, northeast, southwest, and southeast. The core section of the city is characterized by a dense, narrow street grid and a high level of density. The city has annexed additional areas over time beyond the historic grid. These annexes or extensions have lower density and are more suburban. The annexed areas include two of the largest parks in the system, Long’s Park in the Northwest annex and Conestoga Pines in the Northeast annex.

The different quadrants of the city also have different socioeconomic characteristics. The southern quadrants of the city have higher levels of poverty and are home to a larger portion of the city’s African-American and Latino communities. The northern quadrants and the extensions have a larger White population. The southeast quadrant in particular is characterized by a large immigrant population and populations of households that are isolated by language barriers. The different socioeconomic characteristics of each quadrant prompted the consultant team to benchmark the parks from both a city-wide perspective and on a quadrant level.

Other Parks

School District Properties (open to the public)

Cemeteries

Other

NORTH WEST

NORTH WEST EXT.

SOUTH WEST

NORTH EAST

NORTH EAST EXT.

SOUTH EAST

SOUTH EAST EXT.

The government of the City of Lancaster is based on Pennsylvania’s Constitution, which authorizes the General Assembly, Pennsylvania’s state legislature, to create different types of local government and to give each specific responsibility and authority to carry out those responsibilities. All forms of local government were created by the state legislature and operate under the laws of the Commonwealth. Each local government operates under a state law, called the Municipal Planning Code (MPC) which establishes who and how the local government is managed.

The City of Lancaster currently functions as a city of the Third Class under the Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As a city of the Third Class, Lancaster operates under a MayorCouncil form of government, which includes a full-time mayor and a seven-member city council, the members of which are part-time and are elected to a four-year term. Under the State Code for Cities of the Third Class, Lancaster is not required to have the council represent geographic districts, and therefore all members of the city council are elected at-large and do not necessarily represent all of the city’s quadrants and annexed areas. Due to this, certain areas of the city can be underrepresented by the council. Historically, the least represented areas of the city are the southwest and southeast quadrants.1

The PA code gives the council certain responsibilities, the legal authority to carry out these responsibilities, and the means to pay for them generally through taxes or fees.

The mayor is the chief executive of the city and enforces the ordinances of the council. The mayor may veto ordinances, but that can be overridden by at least two-thirds of the council. The mayor supervises the work of all city departments and submits the annual city budget to the council. Property taxes remain the primary source of Lancaster City’s Budget.

1 https://lancasteronline.com/news/local/ lancaster-residents-want-more-representationforsoutheast-in-city-government-democratic-party/ article_bd52f784-b86c-11ed-8b6df7369aaf04a2.html

In the 2023 City of Lancaster Budget Address, Mayor Sorace quoted from an October 2022 Pennsylvania Economy League study, “It’s Not 1965 Anymore: State Tax Laws Fail to Meet Municipal Needs,” because Lancaster’s tax structure is antiquated and the city cannot rely on other taxes to cover the city’s operating expenses.

The Mayor proposed and the voters have supported a study commission to review and adviste on potential updates to the tax structure in the city. The revised tax structure could allow for more funding to be allocated for parks, recreation, and open space; following the recommendations of this plan could thereby provide for a more equitable distribution of parks & recreation services within Lancaster.

The City of Lancaster and Lancaster County have engaged in extensive planning over the years. The goals and findings of these plans have guided the development of this Comprehensive Parks, Recreation, and Open Space Plan. The last city-wide parks plan completed by the City of Lancaster was the Urban Park, Recreation and Open Space Plan prepared in 2009. This plan focused on developing and improving open space connections, enhancing existing park facilities, and promoting environmental stewardship and education.

Our Future Lancaster: The City of Lancaster’s Comprehensive Plan is a document that guides city decision-making regarding future development. It identifies what is important to the community and creates a vision for development over the next 20 years. The plan focused on five major planning systems:

Strengthening Neighborhoods and Housing (SNH) focuses on stable, supportive, and equitable neighborhoods where all residents have the same access to social capital, safe housing, green spaces, economic opportunity, and public services;

Expanding Economic Opportunity (EEO) by growing the local economy and prioritizing the triple bottom line (economy, equity, environment);

Connecting People and Places (CPP) by providing access to jobs, services, and educational needs and creating a sense of community and shared spaces;

Growing Green (GG) focuses on natural resources, parks and open space, sustainable buildings, and infrastructure systems to limit greenhouse gas emissions, reduce waste, and improve urban sustainability;

Building Community and Capacity (BCC) includes community health, safety, and welfare to enable residents to take greater control of their lives.

Revitalizing and connecting to the Conestoga Riverfront was also a major focus of the Comprehensive Plan, including further development of the Conestoga Greenway Trail. The Sunnyside Peninsula is identified as a major opportunity to develop natural parkland, extend the Conestoga Greenway Trail, and provide connections to the Conestoga River.

Places 2040: A Plan for Lancaster County is the county’s comprehensive plan. It priorities, include: Managing Growth by creating compact, walkable communities; improve Transportation by building a network with more alternatives and connections; enhance Parks, Trails and Natural Areas by providing more places to hike, bike, and enjoy nature.

Both the City and County of Lancaster have been very proactive in planning for active transportation and Vision Zero. Active transportation describes transportation networks that reduce congestion and promote physical activity. Vision Zero is an transportation planning approach that sets the goal of eliminating severe injuries and fatalities for all road users, including cyclists and pedestrians.

The Lancaster Active Transportation Plan (2019) was a joint effort between Lancaster County, the City of Lancaster, and the Lancaster Intermunicipal Committee. The goals include connecting the transportation system, implementing complete streets, improving safety through education awareness and enforcement, encouraging walking and biking, and working collaboratively to implement active transportation priorities. The report includes a recommended bikeway network for the City of Lancaster, integrating with bike network improvements in the county.

The City of Lancaster’s Vision Zero Action Plan (2020) identifies the city’s high-injury network and most dangerous intersections. Lancaster has followed up the Vision Zero Action Plan with several Vision Zero projects aimed at creating safer intersections and bicycle facilities, including the South Duke Street Mobility Project, the Church Street Complete Streets Project, and the Water Street Bicycle and Pedestrian Boulevard. These specific projects also implement the bikeway network recommended in the Active Transportation Plan.

Green It! Lancaster (2019) is the city’s green infrastructure plan to create livable, safe, and sustainable communities and clean rivers and streams. The plan looks city-wide at the potential of green infrastructure to manage stormwater runoff and mitigate combined sewer overflows to meet the city’s requirements under its 2018 consent decree with the Environmental Protection Agency and Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. It identifies green parks as one of eight green infrastructure strategies. The plan identifies green parks and green streets as the most effective green infrastructure strategies in terms of both the volume of stormwater they can manage and the lowest overall unit cost. Currently, Lancaster is in the process of preparing Clean It! Lancaster’s Combined Sewer Overflow Control Plan.

Trees for People: An Action Plan for Lancaster City’s Urban Forest (2020) seeks to increase and maintain Lancaster’s urban forest sustainably, and to enlighten residents and property owners about the importance of the urban forest so that it will remain healthy and verdant, and continue to benefit all residents and visitors long into the future.

Lancaster Public Art Ten-Year Plan (20172027). The plan focuses on equity, livability, and excellence to promote neighborhood connectivity, create meaningful collaborations, and magnify Lancaster’s distinct sense of place to position Lancaster as a city distinguished by public artworks and engaged communities. It seeks to ensure that

• every community in Lancaster will have opportunities to collaborate with artists on projects in the public realm (equity)

• public art contributes to Lancaster’s sense of community, livability, creativity, and character (livability)

• public art initiatives in Lancaster are guided by artistic excellence and sincere community participation (excellence)

Southwest Lancaster Neighborhood Revitalization Strategy (SoWe) 2016 is a 10 year vision to chart a course of action to enable Southwest lancaster to identify and prioritize revitalization strategies.

The Historic Southeast Neighborhood Plan is a neighborhood strategic planning process that began in 2018 and was led by the Spanish American Civic Association (SACA) for residents, business owners, civic leaders, and other stakeholders to share their goals and aspirations for the neighborhood. Strategies identified by the plan include introducing neighborhood connectors, creating new and improving existing civic spaces, and involving the community in plan implementation to build social cohesion.

The Conestoga Pines & Walnut Street Fishing Master Plan (2023) is currently in process. It studies the 61-acre park located in the Northeast Extension of Lancaster along the banks of the Conestoga River. It looks at making improvements to the park to promote public enjoyment of the park and improve the long-term health of the Conestoga River. It seeks to increase access to the river for fishing, small craft, and boardwalks; to protect and manage the existing forest; to protect the historic Civilian Conservation Corp Will Rogers Camp; and update the existing barn into a recreation center. It also proposes removing the existing pool, which is at the end of its life and located in the flood plain.

In addition to understanding the city-wide context, part of the scope was to compare the Lancaster Parks, Recreation, and Open Space System to other similar jurisdictions in the state and nationally. To do this, the consultant team referenced several national standards, such as the National Parks and Recreation Association (NRPA), other similarly sized third-class cities in Pennsylvania, such as Harrisburg and Bethlehem, as well as national studies, such as the Trust for Public Land’s Park Serve System, and Lancaster’s own goals and objectives for its park system as a welcoming and inclusive community.

These benchmarking standards were used to evaluate the system overall, including the level of investment, staffing, and operating expenditures, and equity (the size, distribution and accessibility of park and recreation resources across the city. They were used to develop a park scorecard for evaluating the individual parks.

The NRPA is a national non-profit organization dedicated to building strong, vibrant, and resilient communities by supporting the work of park and recreation professionals. Their mission is to “advance parks, recreation, and environmental conservation efforts that enhance the quality of life for all people.”1

The NRPA has three pillars2 that guide their work:

• Health & Wellness: Advancing community health and well-being through parks and recreation.

• Equity at the Center: Striving for a future where everyone has fair and just access to quality parks and recreation.

• Conservation: Creating a nation of resilient and climate-ready communities through parks and recreation.

The NRPA publishes an annual NRPA Agency Performance Review. This review collects data from across the country and is a benchmarking resource that assists park and recreation professionals in the effective management and planning of their operating resources and capital

1 https://www.nrpa.org/aboutnational-recreation-and-park-association/ 2 https://www.nrpa.org/ourwork/Three-Pillars/

facilities. It provides data on park facilities, programming, staffing, budget, funding, and policies. The data presented by the Performance Review is broken down by jurisdiction size. These metrics were used to benchmark Lancaster’s Park and Recreation System as one facet of the system-wide evaluation in the next chapter.

In addition to the NRPA, other organizations have been working to create park evaluation standards and metrics.

The Trust for Public Land has a national 10-minute walk to parks goal. As part of that campaign, they have developed a park score rating system, which looks at a city’s park system through five categories: acreage, investment, amenities, access, and equity.3

Acreage is a combination of median park size and the percentage of city area that is dedicated to parkland. Investment is measured as public spending by all agencies that own or manage parkland with the city as well as state, federal, and county agencies, non-profit spending, based on information from 1090s and volunteer hours. The amenities measure focuses on six key park amenities on a per capita basis: Basketball hoops, off-leash dog parks, playgrounds, recreation, and senior centers, restrooms, and splash pads and spraygrounds. Access focuses on the percentage of the population living within a 10-walkable service area for each park.

The Pennsylvania Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan: Recreation for All, 2020-2024 lays out DCNR’s blueprint for meeting the outdoor recreation needs of all Pennsylvanians. The plan focuses on five priority areas: Health and Wellness; Recreation for All, including equitable access and meeting the needs and expectations of the underserved; Sustainable Systems; Funding and Economic Development; and Technology.

The Urban Land Institute also undertook a study to examine the importance and characteristics of high-quality parks. It finds that communities of color and low-income communities receive less park investment than more affluent white communities. They note that evaluating park quality can engage communities and help address disparities in funding and investment to create equitable 3 https://www.tpl.org/parkscore/about

access to high-quality parks. The report outlines five characteristics of high-quality parks and identifies key evaluation questions within each of the criteria:

• High-quality parks are in excellent physical condition

• High-quality parks are accessible to all potential users

• High-quality parks provide positive experiences for park users

• High-quality parks are relevant to the communities they serve

• High-quality parks are flexible and adaptable to changing circumstances

Change Lab Solutions’ Complete Parks Playbook (2015) develops the idea of a “complete parks system.” This concept is a way to assess parks, green spaces, and open spaces in a community, and to identify areas in need of improvement and the policies necessary to support those improvements. The complete park system has eight elements:

• Engage: Engaging everyone in the process

• Connect: Creating safe routes to parks

• Locate: Ensuring equitable access to parks

• Activate: Programming activities and amenities for parks, ensuring that all members of the community can participate

• Grow: Planting and maintaining sustainable parks to protect and support biodiversity and ecological integrity

• Protect: Making parks safe using crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED)

• Fund: Committing to finance the complete parks system, including capital projects, ongoing maintenance, and programming.

Finally, an important component of developing the criteria for evaluating the system was understanding the specific goals and objectives of the City of Lancaster. Lancaster is a city committed to public engagement and inclusion as well as to being a welcoming community for immigrants and refugees. Lancaster is one of the largest refugee destination cities in Pennsylvania.1

1 https://www.democratandchronicle.com/ in-depth/news/2022/01/10/refugees-palancaster-pennsylvania-dutchimage/8765556002/

The City of Lancaster’s Strategic Plan, Block-byBlock focuses on four key areas: Strong neighborhoods; safe places; sustainable economy; and sound government. Lancaster is also a certified Welcoming City. The Welcoming City framework focuses on ensuring equitable access to community services and opportunities for all residents, newcomers, and immigrant communities providing opportunities for civic engagement, and providing safe communities.

During the CPROS planning process, the consultant team worked with the project steering committee to define a high-quality park system. The steering committee, which includes representatives from the city, county, and recreational non-profits, identified the following components of a high-quality park system:

• Focus on nature and ecology

• Have community buy-in, support, and engagement with the parks

• Provide diverse and high-quality amenities and programming

• Provide opportunities for both active and passive recreation

• Are easy to access and accessible: residents should be able to walk on safe streets to parks that are ADA accessible and have connections to transit

• Welcome all users: there should be activities and amenities for people of all ages and from all backgrounds, providing language and cultural access

• Are knowable and transparent: it should be easy for residents to understand the entire system, what amenities and activities are available, how to get there, and how to access them

• Are well cared for and maintained, both by the city and by the residents

• Are adaptable for multiple uses

• Have quality design and comfortable spaces

Finally, the phased, year-long public engagement process, which consisted of in-person workshops, surveys, interviews, focus groups, and community events, aimed to intentionally include public input into the CPROS Plan. Community stakeholders and community members were asked what they wanted to see in the parks, what they liked about the parks, and what would lead them to use the parks more often.

The consultant team used studies, benchmarks, standards, and public input to evaluate the Lancaster Park System. The information collected was used to create a scorecard for the parks and to develop recommendations in this report that address the established criteria, goals, and aspirations.

Building on the benchmarking references above, the consultant team developed a set of metrics for evaluating individual parks, which was organized into a quantitative scorecard. The team also developed a set of evaluation metrics that were both quantitative and qualitative that looked at the park system as a whole. The evaluation was conducted through a series of on-site evaluations and GIS analysis. To evaluate the Lancaster parks and park system, the team visited all City of Lancaster Parks and conducted an on-site survey. This data was paired with GIS analysis to assign a set of scores to each of Lancaster’s Parks. The consultant team also conducted interviews, focus groups, and community surveys to gather additional information and reviewed the 2023 budgets for the City of Lancaster and the Lancaster Recreation Commission. Finally, the team benchmarked the Lancaster data against the National Recreation and Parks Association (NRPA) metrics for cities in the 50,000 to 99,999 population range.

For individual parks, the criteria evaluated were:

• Stewardship - is the park clean and wellmaintained?

• Sustainability - does the park contribute to stormwater management, growing the urban forest, and reducing the urban heat island effect?

• Programming and Activities - How many types of uses and programming are available in the parks, and do they provide flexibility in programming?

• Amenities - Are there a variety of amenities available and what is their condition? In parallel, the City of Lancaster conducted Facilities Conditions Assessments of the parks, reviewing in detail the safety and condition of existing structures and equipment in the parks. The consultant team also used the NRPA benchmarks to understand how the level of amenities that Lancaster provides compares to similarly sized jurisdictions nationally.

• Welcoming and Relevant - Does the park appear inviting and welcoming, is it comfortable to spend time in, are entrances clear and well-signed?

• Connectivity, Access & Accessibility- is it safe to walk or bike to the park? Can it be accessed by public transit, can it be accessed by people of all ages with differing abilities.

• Safety - is the park visible from and wellintegrated into the neighborhood, does it feel safe, and are adjacent land uses compatible with a park?

For the evaluation of the system, the consultant team looked broadly at the following categories:

• Knowable & Transparent - is there system-wide legibility, do people know what amenities and programming are available, where it is, and how to get there? Is signage clear and consistent and is it available in multiple languages?

• Size & Distribution - System-wide what kinds of parks are there, are they high quality, and how are they distributed? How does this distribution compare to the demographics of the city?

• Investment - Is system-wide spending, investment, and staffing adequate to support the parks system? The team used the NRPA benchmarks, as well as the Harrisburg and Bethlehem budgets to understand how Lancaster compares to benchmarks and similar cities.

Not all parks are the same. A park might be a large park, such as Lancaster County Central Park with forested areas, trails, and multiple amenities, or a pocket park with just a bench and some trees, such as Triangle Park. Not everyone can live within a 10-minute walk of a park the size of Lancaster County Central Park, but a project goal is for everyone to be within a safe 10-minute walk of a high-quality park. To better evaluate the system and the type of parks that people have access to, the project team developed a set of park typologies to look at the question of access at a more granular level. The

Plazas are typically paved spaces surrounded by buildings and public right of way. They function as meeting and event spaces. Design and landscape are highly important due to compact size, level of use and visibility, weather conditions, and the types of events and programming that need to be accommodated. Plazas are located in central areas and serve either regional or local users (based on programming). Visits can be brief or longer for events and programming. Examples of plazas in Lancaster include Binns Park, Ewell Plaza, and Penn Square.

typologies were developed using several criteria, including size, the number of facilities, the catchment area (the distance people typically travel to get there), visit length (how long people typically spend in the park), and naturalness.1

An example of each park type is provided and identified again for each park evaluation.

1 Byrne, Jason and Sipe, Neil. “Green and Open Space Planning for Urban Consolidation: A Review of the Literature and Best Practice,” Griffith University, January 2010.

Pocket Parks are small, often the size of a single city lot or smaller. They serve localized areas, such as a block, or a street, and typically have few facilities, for example, a bench, some grass or shrubs, a few trees, or a play structure. Visits can be as brief as 10 minutes up to one hour. To be most successful, pocket parks should have good visibility from the public street. Pocket parks can serve as “stepping stones” along the routes to larger parks. Examples of Pocket Parks in Lancaster include Triangle Park, North Market Street Kids Park, and Ewell Gantz Playground.

NEIGHBORHOOD PARK

Neighborhood Parks are 1-2 acres and can accommodate up to 50-75 users. They provide a mix of uses both passive and active. They typically serve a city neighborhood. The average visit is 1-3 hours. Facilities can include green space, plantings, and potentially a mix of play equipment, basketball courts, 1-2 playing fields (soccer, baseball), wading pools or spraygrounds, and picnic tables in zones with passive open spaces for non-active uses. Examples of Neighborhood parks include South End Park, Sixth Ward Park, and Holly Pointe Park.

COMMUNITY PARK

Community Parks are typically 3-10 acres and can accommodate up to 75-200 users. The average visit is 30 minutes to 3 hours but can be longer for events. Community parks serve a larger area than a city neighborhood, drawing from multiple neighborhoods due to their size and amenities. They can accommodate active play areas, such as picnic pavilions, pools, play equipment, and passive spaces. They have a variety of landscaped areas and tree plantings with a variety of uses and can include water features, sculptures, structures, dog parks, trails/greenways, and concessions. These major amenities require significant ongoing maintenance. Examples of community parks in Lancaster include Reservoir Park, Culliton Park, and Musser Park.

REGIONAL PARK

Regional Parks are typically 1 to 500 acres or more and can accommodate hundreds of users. Visit times range from 1 hour to an entire day. They typically have a large mix of amenities including walking trails, a pool, structures, an amphitheater, water features (ponds, lakes, rivers), and can have multiple concessions, including kayak rentals, forested areas, large areas of permeable surface, natural areas, restrooms, and multiple playing fields. People visit from further away, drawing visitors from the entire city as well as suburban users. Examples of Regional Parks in Lancaster Include Long’s Park, Lancaster County Central Park, and Buchanan Park.

Trails and Greenways are linear corridors used for biking, hiking, rollerblading, jogging, and walking. Trails can connect parks and urban, on-street bicycle facilities to assist in park and open space access. Urban trails are typically paved or feature stone fines (sometimes referred to as crushed fines) but can be soft surfaces as well. Trails connect users to natural areas, including rivers and creeks, and forested areas. Trails can attract residents from adjacent neighborhoods and also community and regional users, especially if there is a gateway with parking (and sometimes a portable toilet in warmer seasons or restroom facility). Examples of Greenways in Lancaster are the Conestoga Creek Park, Conestoga Greenway Trail, and Mayor Janice Stork Linear Park.

Streetscapes/Medians are areas of public right of way (ROW) with a higher level of amenity values, including plantings, public art, street furnishings, and amenity paving, such as pavers or exposed aggregate. Streetscape elements can also be incorporated into sidepath and greenway designs for higher-level public realm ROW spaces. Although streetscapes and medians are not typical parks, they can provide important amenity space, safer pedestrian and cyclist areas, and improved connectivity to parks. Streetscapes can also incorporate pocket parks. In Lancaster, Duke Street Mall and Blanche Nevin Park are examples of streetscapes and medians.

Remainders. Some properties are intersticial spaces that may enter into public ownership but are not classified as a park as they provide no amenity value. CANBA park is an example of a remainder in Lancaster.

TRAIL / GREENWAY

In addition to the park types, school properties that are open to the public can provide important recreational opportunities for the community, particularly for sports and active recreation.

STREETSCAPE / MEDIAN

The consultant team worked with the City of Lancaster and the steering committee to develop the benchmark statements, consisting of the mission, vision, and values concerning parks and recreation. The group engaged in an iterative process during several steering committee meetings to brainstorm who the city serves, what services they provide, and how those support the city’s other goals. The answers to these questions guided the development of the recommendation and implementation plan and contributed to creating the mission, vision, and values.

The City of Lancaster’s Strategic Plan, Block by Block, identifies Strong neighborhoods, including quality public spaces and facilities as a city-wide goal. Providing quality parks in all Lancaster neighborhoods supports this broader city goal. Safe Places is another city-wide goal in the Block by Block plan, including safe, walkable, and accessible places for all. Providing safe parks and safe routes to parks supports this broader city goal.

Because Lancaster does not provide recreation services directly, Lancaster’s role in directing the Lancaster Recreation Commission and coordinating the efforts of the many non-profit organizations that provide recreational services and programming is critical to ensuring that recreation opportunities are equitably provided.

Lancaster’s 2023 Comprehensive Plan, Our Future Lancaster, emphasized equity and sustainability as guiding principles for the city’s comprehensive plan. This CPROS plan and these benchmark statements build on the base established by Our Future Lancaster.

We envision a healthy, happy, and engaged community brought together by recreation, parks, and open space.

MISSION

We provide parks and recreation services to enhance the quality of life for Lancaster residents and visitors by connecting people to nature, providing recreational opportunities, and promoting civic engagement with and ownership of the parks and open space.

We believe parks enhance quality of life, physical and mental health, and social and emotional wellbeing.

We provide direction, planning, and coordination of recreation services in the city’s parks and open spaces.

We maintain parks and trails in excellent condition so that they are safe, clean, and ready to use.

We provide safe routes to parks through traffic calming, and improved pedestrian and bike infrastructure.

We believe in equity and will guide investment and spending on parks and recreation that benefit the entire city, especially historically underserved communities and neighborhoods.

We believe parks play a critical role in protecting and improving environmental quality, enhancing climate resilience, and connecting people to and educating them about the environment.

The purpose of engagement for this project was to inform the CPROS plan by allowing the community to give input on their experiences in the parks and thoughts on recommendations that the project team drafted.

Phase 0 was focused on gathering information to draft a public engagement plan. This included creating a community profile to understand vulnerable communities, possible barriers to engagement, and establishing metrics for success for outreach and engagement. This phase occurred between March and May of 2023. The project team worked with the project Steering Committee to:

• Understand target and priority audience groups to engage;

• Understand desired insights from the engagement process;

• Develop a clear understanding of roles and responsibilities for engagement tasks;

• Agree on public engagement schedule and approach

Phase 1 was focused on collecting insights from Lancaster residents about their experiences accessing spaces like parks, playgrounds, and nature areas. This input helped the project team draft initial recommendations. This phase engaged near 280 people and took place between May and October of 2023.

The tactics undertaken during this phase include:

• Pop-ups at 6 local events across Lancaster City

• 16 stakeholder interviews

• 3 focus groups with 16 stakeholders on May 22, July 27, and August 9, 2023

• A survey (open from May 2024 to September 2023)

• 248 participants took the survey

PHASE

Phase 2 was focused on gathering deep, detailed insights and feedback from community leaders and stakeholders on the preliminary recommendations. This phase engaged 86 people and took place between March and April of 2024.

The tactics undertaken during this phase include:

• 2 workshops at Lancaster Science Factory and Lancaster Rec Center on March 14, 2024

• 72 people attended

• A survey (open from March 2024 to April 2024)

• 14 participants took the survey PHASE 3: SHAREBACK

Phase 3 focused sharing back the finalized recommendations which were organized and prioritized based on input from the public.

All laws and ordinances on the City of Lancaster’s parks and Lancaster Recreation Commission are included in the City of Lancaster’s Code. The code includes articles and chapters on Parks, Facilities, the Department of Public Works, Boards and Commissions, pools, skateboards, trees, public streets, riparian corridors, vending, zoning, public art, graffiti, and stormwater management.

The primary responsibility for maintenance of Lancaster’s parks resides with the Bureau of Parks and Public Property (BPPP) within the Department of Public Works (DPW). DPW is one of five departments that report directly to the Mayor within the Organizational Chart of the City of Lancaster. Other key departments that interface with Parks and Recreation include:

• The Department of Neighborhood Engagement (DoNE) and Lancaster Office of Promotions (LOOP)

• The Department of Public Safety

• The Department of Community Planning and Economic Development

The Director of Public Works is responsible for four divisions within DPW and approximately 210 full-time employees. The DPW Divisions are:

• Public Right of Way

• Construction and Operations

• Sustainability and Environment

• Utilities

The Director of DPW represents the City of Lancaster on a variety of Boards, including Long’s Park Commission, Lancaster County MPO, Lancaster Recreation Commission, Public Arts Advisory Committee, and Green Infrastructure Advisory Committee.

Although not shown on the Organization Chart on page 39, the Department of Administrative Services supports DPW and all departments with grant writing and other financial and accounting services.

The Department of Neighborhood Engagement (DoNE) was created in 2022 by the Lancaster City Council by merging the Lancaster Office of Promotion (LOOP) and Neighborhood Engagement into one department, although LOOP continues to operate under that name. DoNE’s purview includes:

• Language Access,

• Tourism and Promotion, and

• Civic Engagement.

DoNE intersects with Lancaster’s Park and Recreation system in the following areas:

• planning special events,

• permitting the use of public space,

• river connections through the Love Your Block Community Building Grants, and

• building civic engagement and language access to park and recreation resources.

Through LOOP, DoNE is directly responsible for planning special events, marketing Lancaster as a destination, managing the Lancaster City Welcome Center, and permitting the use of public space.

In 2023 DoNE rolled out the Fix It! Lancaster program, which is the city’s new non-emergency request platform which residents utilize to submit their service requests. Many requests are routed through DPW’s Bureau of Parks and Public Property and handled by staff, adding additional tasks to their workdays. In addition, DoNE oversees the Public Art Community Engagement (PACE) program which is grantbased and supports local artists in making temporary public art.

Because Lancaster’s Parks and Recreation spaces do not have a Park Ranger program, the responsibility of enforcing any park rules and regulations falls to either “individuals designated by the Director of Public Works,” Animal Law Enforcement Officers, or all city police officers per City of Lancaster Code (Chapter 210 Parks).

BUREAU OF ENGINEERING

TRANSPORTATION

CONSTRUCTION & OPERATIONS

SUSTAINABILITY & ENVIRONMENT

PUBLIC RIGHT OF WAY UTILITIES

BUREAU OF PARKS & PUBLIC PROPERTY

BUREAU OF STREETS, TRAFFIC & FLEET

BUREAU OF STORMWATER

BUREAU OF WATER

CLIMATE ACTION PLAN

BUREAU OF WASTE WATER

CONSTRUCTION

BUREAU OF SOLID WASTE

Lancaster City Departments with responsibility for the parks and recreation system

Bureau of Parks and Public Property

Organizational Chart

BUREAU OF PARKS & PUBLIC PROPERTY

CONSTRUCTION SUPERVISOR

The Department of Community Planning and Economic Development (CPED) includes the Bureau of Planning within the Land Development and City Division. This department may collaborate with DPW to apply for design and planning grants for parks, trails, and open space. The Bureau of Property Maintenance and Housing Inspections unit ensures safe and quality housing stock through the administration of the city’s ordinances. The Historical Commission oversees the Heritage Conservation District and reviews projects that have an impact on the surrounding streetscape. There are several parks within the Heritage Conservation District, including Buchanan, Musser, and Reservoir. The Historical Commission is involved in any changes to parks

falling under the Heritage Conservation District and adheres to the Design Standards in the Heritage Conservation District.

It should be noted that the CPED also provides administrative support to the Redevelopment Authority of the City of Lancaster (RACL) and the Land Bank Authority through service agreements. RACL is a state agency and not officially part of the CPED.

The Bureau of Parks and Public Property (BPPP) lies within the Department of Public Works and has primary responsibility for the management of the parks. It was created in 2020 when the Bureaus of Facilities Management merged with Parks (including Long’s Park), Trees, and Green Infrastructure to create the Bureau of Parks & Public Property. The manager of BPPP reports to the Deputy Director of Construction and Operations who in turn reports to the Director

of Public Works.

Under the BPPP Manager, six separate structural units report to their own internal chain of command with one construction supervisor assigned to all units who reports directly to the BPPP Manager. There is also an Administrative Assistant who coordinates between management and staff. The total full-time staff of the Bureau of Parks and Public Property is 43 employees, including the BPPP Manager.

Building Maintenance is responsible for sixteen city owned municipal buildings, including City Hall, Police Administration Building, fire stations, and park buildings.

Parks Maintenance is responsible for maintaining all city parks, including wading pools (with assistance from Lancaster Rec), restrooms, mowing, trash removal, is heavily involved in special events (set up/tear down).

Long’s Park has staff dedicated specially to the 80-acre Long’s Park in NW Annex. The Long’s Park Commission oversees Long’s Park while BPPP staff work on maintenance.

Green Infrastructure is responsible for all rain gardens and stormwater BMP’s located within the public realm city-wide.

Landscape is responsible for landscaping around all parks and public property.

The City Arborist heads the Tree Crew and is responsible for complying with the City’s Tree Ordinance and street tree planting program. The Tree Crew is funded by the stormwater fund.

Though not public facing, the Mission of the BPPP is:

The Bureau of Parks and Public Property strives to provide an exceptional work and public environment which is functional, clean, accessible, and sustainable via facilities and maintenance services that are fully aligned with the City’s strategic and financial objectives.

In 2023, the City of Lancaster adopted Cityworks, an asset-based, internal-facing work order management system utilizing ArcGIS to create a more manageable workflow while also allowing for the development of priorities. Before this, maintenance work was performed in more of an ad hoc manner. Implemented in 2024, Cityworks should provide a more manageable way for BPPP management and staff to track work orders and allow for better record-keeping and asset management over time.

The total level of funding for the BPPP in the

Lancaster budget in FY 2023 was $5,870,563. This includes funding for staff, park and building maintenance, and tree and green infrastructure maintenance. The majority is contributed from the general fund but includes contributions from the stormwater fund as well. Applications for construction grants falls under the auspice of the Construction Capital Unit of DPW with support from Administrative Services.

There are a total of 43 full-time employees (FTEs), including the Manager of Parks and Public Property.

Lancaster has 7.7 FTEs, or parks related employees, per 10,000 residents. This is lower than the median for cities of a similar size in the NRPA benchmark. Moreover, it is low given the population density of Lancaster. According to the NRPA 2023 Agency Performance Review, agencies with greater population density should have higher FTEs per number of residents. Jurisdictions with more than 2,500 people per square mile have an average of 10.2 FTEs per 10,000 residents. Lancaster, with a population density of 8,000 people per square mile has only 7.7 FTEs per 10,000 residents, well below the national benchmark for similar-sized and densely populated jurisdictions.

Even though staffing levels are below the NRPA benchmark and are lower than other similarly sized third-class cities in Pennsylvania, staff is routinely not being used specifically on parks, so in reality park-specific staffing levels are very low. Due to this, management and staff have very little ability to proactively maintain and operate parks. Low levels of staffing for landscaping leave little time for the beautification of park facilities through plantings and maintaining plantings while parks maintenance staff spend the majority of their time mowing during 8-9 months of the year.

In addition, BPPP Buildings Maintenance staff also spend a considerable amount of time on the numerous special events that the City of Lancaster hosts throughout the year. While these events contribute to the quality of life of the citizens of Lancaster, the Special Events set up/tear down process is time-consuming and removes staff from any daily operations.

In the Annual Budget of the City of Bethlehem, PA, a peer Pennsylvania City with approximately 75,000 residents, there is a clear breakdown of the goals and objectives of the Recreation Department, something the Lancaster Budget lacks for BPPP (only the day-to-day duties). Potentially laying out core duties of BPPP staff and the goals and objectives of this Bureau within DPW for the Annual Budget would create goals that the City Council would support and

align with and would provide a more aspirational emphasis on work within the public realm as well as potentially commit more fiscal resources to the BPPP from the Annual Budget.

According to the BPPP manager, much of the Parks Maintenance staff time is spent mowing the approximately 80 sites that fall under the BPPP management, including all park and public property land within the city as well as water facilities owned by the City of Lancaster that are outside the city limits in other areas of Lancaster County, including Columbia Borough which is approximately 15 miles to the west of Lancaster. To mow these areas, travel time is included in the calculation contributing to a considerable amount of time devoted to mowing in-season. Due to this, routine maintenance within parks is consistently deferred and staff cannot be proactive on issues which would lead to improved parks from a maintenance perspective. (See Page 260 of the City of Lancaster Budget–Bureau of Water Grounds Maintenance: 5.9 FTE/yr dedicated to mowing water facilities).

In addition to mowing, BPPP Buildings Maintenance staff are also tasked with graffiti removal on public and private property, which removes staff from performing core duties. Graffiti is specifically discussed in the City of Lancaster’s Code and is a priority for the city to have graffiti removed from private property (see code–https://ecode360.com/8118199). In discussions with management and staff, it appears that staff spends a lot of time on graffiti removal.

In January 2023 the City of Lancaster rolled out its “Fix It! Lancaster” program through the Department of Neighborhood Engagement. While the program intends to provide more efficient city services for non-emergencies, BPPP staff are engaged in responding to these requests, again removing them from core duties within the BPPP. There is also the possibility that this system could add more time to graffiti removal as that is a prime complaint in the system.

Public restrooms are routinely available in Culliton Park, Brandon Park, Buchanan Park, Ewell Plaza, Long’s Park, Reservoir Park, Rodney Park, and Sixth Ward Park. With the exception of Ewell Plaza, these restrooms are only open and available during the periods that staff is on duty to custodially manage and maintain them, i.e. Monday through Friday, ~7:30a to ~3p; they also lack insulation and are winterized and completely unavailable between ~November 1 and ~April 1 annually. Ewell Plaza’s restrooms are available year-round and are generally open in accordance with park hours between approx. 9a to dusk. South End Park and Musser Park do have restrooms, but these are not publicly available and are generally only open during special events or rentals. A common complaint/issue in interviews with stakeholders is the lack of public restrooms during times the public most needs them–after school hours and after work when people are using parks and or participating in recreational activities.

Volunteering is challenging (“Adopt-It” Program) as it requires the supervision of the Parks Maintenance Supervisor. Volunteer groups are sporadic and require effort to manage. Citizens who are involved know which staff to contact when there is a need, however, there is no staff assigned to any specific stewardship or volunteer activities. This is an equity issue as citizens who know the system and are connected to city staff benefit while those who don’t know who to contact tend to come from more historically disadvantaged areas such as the Southeast/Southwest neighborhoods.

The City of Lancaster does not historically or presently provide any recreational programming on any parks or open space that it owns. Instead, per the City Code, it relies on the Lancaster Recreation Commission (LRC), a non-profit partner of the city, to program the various parks, open spaces, and recreational areas throughout the City of Lancaster. Several other private, non-profit organizations provide communitybased services that interface with park and recreation space. The City of Lancaster and the School District of Lancaster own the majority of land and facilities, including most play equipment, playgrounds, ball fields, courts, wading pools and pool (Conestoga Pines), and other recreational amenities on which all recreational programming takes place in the city. In addition, the recently created Lancaster Rec Foundation Fund, a separate 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization was created to provide recreation services to all for the long-term.

Non-profit organizations partner with the City to provide either recreational programming, utilize park space in an organized manner, interface with city-owned land, maintain aspects of city-owned land, or lease buildings or land from the City. Certain groups are geographically focused while others are city-wide and even extend into suburban areas, in the case of the LRC, and the programming it provides in Lancaster Township, which is a partial funder of the LRC.

In addition, there are smaller, geographically based groups focused on specific parks, providing stewardship, engagement, programming, and stakeholder-led improvements. These groups are connected to the leadership at BPPP but are not connected to one another in their efforts which serve only the individual parks.

LANCASTER RECREATION COMMISSION (LRC)

• City Wide and Lancaster Township

BOYS AND GIRLS CLUB OF LANCASTER

• City Wide and lease Roberto Clemente Field

COMMON WHEEL