17 minute read

Informed Dissent

THE NEW HOAX The failures that brought us this pandemic can never be forgiven or forgotten

BY JEFFREY C. BILLMAN

Advertisement

“The reason you’re seeing so much attention to [COVID-19] today is that [the media] think this is going to be the thing that brings down the president. That’s what this is all about it. … The flu kills people. This is not Ebola. It’s not SARS, it’s not MERS. It’s not a death sentence; it’s not the same as the Ebola crisis.” – Acting chief of staff Mick Mulvaney, Conservative Political Action Conference, Washington, D.C., Feb. 27, 2020

From 2014-2016, Ebola killed more than 11,300 people. In 2003, SARS infected 8,096 people and killed 774. In 2012, MERS spread throughout the Arabian Peninsula, leading to about 2,500 confirmed cases and 858 deaths by the end of 2019.

As of Monday morning, COVID-19 has infected nearly 1.3 million people and killed 70,356 in just over three months.

Mulvaney wasn’t speaking out of turn. This was the party line. A day earlier, on Feb. 26, Trump tweeted that the coronavirus was “very much under control.” At a press briefing on Feb. 24, when there were 58 known coronavirus cases in the U.S., Trump said it wasn’t as big a deal as the flu: “The flu, in our country, kills from 25,000 people to 69,000 people a year. That was shocking to me. … And again, when you have 15 people, and the 15 within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero, that’s a pretty good job we’ve done.”

A few hours after Mulvaney hand-waved the coronavirus threat, the president traveled to a MAGA rally in South Carolina, where he blamed not just the media but Democrats for overhyping the crisis: “This is their new hoax.”

Two days later, the first American died of COVID-19. Since then, 9,652 Americans have followed – again, as of Monday morning – and roughly 338,000 Americans have been diagnosed with the novel coronavirus.

If Trump gets his way, this history will be memory-holed. In his retelling, he knew it would be a pandemic before anyone called it a pandemic, and he took it seriously from the start, even though it was a crisis no one saw coming. And if the death count is less than 2.2 million – as in a years-long, worst-case-scenario projection that assumed no mitigation – it will be a testament to his leadership.

Last week, the White House’s coronavirus task force unveiled its own projection: Between 100,000 and 240,000 would die, it said, though the White House wouldn’t divulge the projection’s timeline or assumptions. As of Monday, the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s model – which the White House used to develop its projections – forecast 81,766 U.S. deaths through August.

Some public health officials believe the IHME is optimistic, and other models are much grimmer. But if it is correct and this wave of COVID-19 fizzles by July, Trump will head into the election touting it as an achievement. And all of a sudden, 80,000 deaths in four months – more than in Vietnam, more than 25 9/11s – will somehow be recast as a victory instead of a colossal failure, likely with the same pusillanimous media now swooning over Trump’s “change of tone” complicit in the sales job. Trump is, if nothing else, a champion bullshitter.

But make no mistake: This is a colossal failure with catastrophic repercussions. It will cost thousands of lives. And the worst of it could have been avoided. We shouldn’t forget that. And we damn sure shouldn’t forgive it.

Two startling reports from this weekend lay bare how badly Trump botched the most important job of his presidency.

The first, from the Associated Press, reveals that the administration waited until mid-March to place bulk orders for N95 respirator masks, ventilators, and other equipment needed by front-line health care workers. By that time, the national emergency stockpile was depleted. In late March, Trump finally ordered General Motors and Ford to manufacture ventilators, but the order came too late for them to produce mass quantities before the peak of the crisis hits.

More damning is a devastating Washington Post investigation detailing how a disinterested president and his incompetent team missed chance after chance to contain the virus before it spun out of control, all while telling the public that this was nothing to worry about.

Throughout January, as officials tried to focus Trump’s attention on the pandemic, he brushed them aside. Finally, on Jan. 31, Trump shut down travel to China, but only after China locked down Wuhan. By then, the U.S. already had eight coronavirus cases.

Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar’s efforts to secure additional funding for equipment and a testing-and-tracking network were shot down as “alarmist.” When coronavirus cases started to mount, the White House eventually agreed to ask Congress for $2.5 billion, which Congress upped to $8 billion. By then, the Post reports, “The United States missed a narrow window to stockpile ventilators, masks and other protective gear.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention failed to put together a reliable coronavirus test while the government blocked private and academic labs from deploying their own until Feb. 29. Again, too late. Without widespread testing, the U.S. lost weeks in which it could have pinpointed and contained outbreaks before they spread.

This tragedy of errors, of course, traces to the very top: to a president who disdained expertise, nurtured his sense of grievance, and prioritized the stock market and his own re-election above all else.

The result, as the Post succinctly puts it, is that “the United States will likely go down as the country that was supposedly best prepared to fight a pandemic but ended up catastrophically overmatched by the novel coronavirus, sustaining heavier casualties than any other nation.”

No matter how many die, that will always be Trump’s unpardonable sin. feedback@orlandoweekly.com

PUT YOUR MONEY WHERE YOUR MOUTH IS How to ethically use your federal coronavirus relief check

BY DAVID ANDREATTA In a few weeks, most American taxpayers will receive a onetime check from the federal government for $1,200, plus $500 per dependent child, as part of a relief package intended to help them weather the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic.

The payments are for people earning below $75,000 a year, like my wife and me, who, with our two children, are in line for a $3,400 windfall. The rebates begin to phase out after that income level before dwindling to zero for those earning over $98,000. For the millions of workers who have lost their jobs, that extra money will hopefully be put to good use paying rent, mortgages, utility bills and day-to-day living expenses.

But what of the millions of taxpayers like my wife and me who still have our jobs and for whom this aid is found money? How should we use our share? What is the right thing to do? What is the ethical thing to do?

There has been no shortage of news stories citing the advice of personal finance experts on how to best use the money. Most conclude the same thing: Seed a rainy-day fund, then pay off debt and, if there’s anything left over, invest it.

That’s perhaps how to best use the money from a personal finance standpoint, but that’s not my question. I’m asking how the money should be used by someone in my circumstances. In other words, what is the purpose of the money?

Some congressional leaders have called the $2 trillion package a “stimulus,” but that’s a misnomer. The economy, which has been shut down to slow the spread of the virus, doesn’t need a jolt to get moving again. It can’t move.

What the government is really trying to do with the payments is tide people and businesses over until it is safe for the economy to start up again. The government is essentially paying people not to work and businesses not to shut down, even if they have no customers.

My wife and I don’t need to be helped through this period financially, at least not now. Our 401(k)s are anemic at the moment, but we have a savings account that could sustain us for a few months. Barely, but the money is there.

For advice, I didn’t turn to another personal finance consultant. I turned to an ethicist. Randy Curren, who heads the philosophy department at the University of Rochester, where he specializes in ethics, explained that the money was intended to sustain economic activity on which people other than my wife and I – and the millions of others like us – depend.

He went on to say that while my household may not need the money, people at our income level are generally more likely to spend it than the wealthy, who already have more money than they know how to spend.

“In the spirit of the law’s intent, people who receive these payments should spend what they can to help those who are more vulnerable – the small businesses and nonprofit organizations of our communities,” Curren says.

Richard Dees, a professor of philosophy and bioethics at the University of Rochester who researches public health ethics, weighed in, saying taxpayers like me should consider aiding a nonprofit agency.

“There are many agencies that are getting hit by requests for help that could use the cash, or other nonprofits, like arts organizations, that have been shuttered by the virus that could put a donation to good use right away,” Dees says.

My wife and I aren’t wealthy. In these unprecedented and uncertain times, my gut tells me to sock away our $3,400 to shore up our rainy day fund for, well, a rainier day, which at this rate seems right around the corner.

But not spending it might be worse for everyone.

One family can’t solve the current crisis. But one family can do its part to alleviate the strain on others. What that looks like for us is dumping the money into a local business in our community.

After some thought, that business will be a landscaper.

For years, we’ve put off felling a couple of trees in our yard, one of them diseased, that are perilously close to our home. They need to come down before they topple and put a hole in the house – a hole the size of the one in many people’s wallets right now.

David Andreatta iseditor of the Rochester City Newspaper, where this story first appeared. feedback@orlandoweekly.com

NEWS

MASKING ANXIETY

Central Florida’s nurses are working on the front lines with very little personal protection

BY LILLIAN HERNÁNDEZ CARABALLO S ecurity, stability and permanence are fragile constructs at the best of times, but in this grave new world we all find ourselves in, well, they’ve all but shattered.

Ever since Central Florida started feeling the effects of COVID-19, Marissa Lee’s work day has changed significantly.

The labor and delivery nurse says the first thing she does is find the hand sanitizer as soon as she gets in the building. The second thing she does is put on a surgical mask.

She then goes about her business at the Osceola Regional Medical Center in the new world of COVID-19, explaining to each of her patients why she’s wearing a mask and carefully assessing health threats.

Lee is doing her best to keep everyone as safe as she can. There’s only one problem: Surgical masks don’t protect against the infection.

Yet Lee says that ORMC medical staff is lucky if they even get that, as N95 masks and other necessary personal protective equipment are being locked away, denied and harshly regulated.

Lee and the staff at ORMC are not alone. As the global battle against the new coronavirus continues to intensify, the American healthcare system is becoming overwhelmed with a demand for adequate medical care. The sudden spike in patient numbers and the urgency of their conditions have left hospitals across the U.S. depleted of resources and medical staff basically begging for provisions.

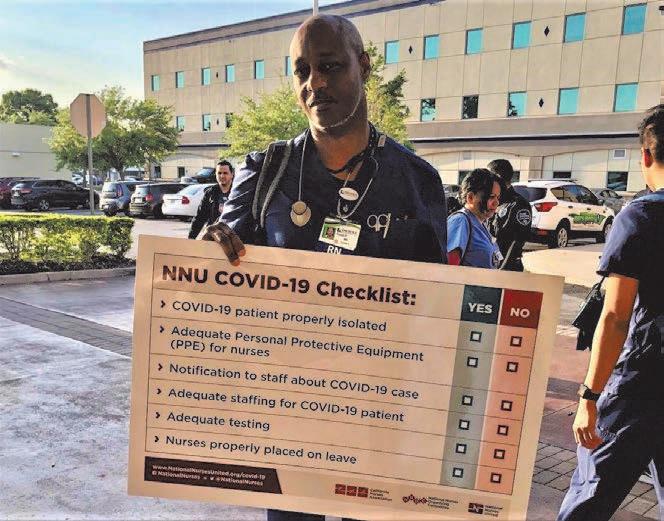

Outraged at the neglect from hospital owners, management and authorities, National Nurses United, the largest

workers union for registered nurses in the country, organized to protest “a lack of preparedness” that they say “places nurses, other staff, and patients at risk” during this pandemic. The protests took place last week in 15 different medical facilities spanning several states.

“Nurses at various HCA hospitals are reporting that they have had to work without proper protective equipment,” said a National Nurses United press release released last Wednesday. “They are told to unsafely reuse masks, and at one hospital they are even being told not to wear masks because it ‘scared the patients.’”

HCA stands for Hospital Corporation of America, recently renamed HCA Healthcare – a Fortune 500 company with a recorded revenue of $46.6 billion in 2018, and also the company formerly led by Florida Sen. Rick Scott. You may remember HCA for committing the largest Medicare fraud in U.S. history under Scott’s watch.

According to the NNU press release, “the wealthiest hospital corporation in the United States” should be able to meet such minimal demands, and failing that, should be held accountable for its “disgraceful and unconscionable” disregard for worker and patient safety.

The protesters held signs bearing a checklist of specific items nurses need to properly attend patients sick with COVID19. They used the opportunity to educate other nurses about their entitlements as workers.

Lee says the protests were kept small on purpose. Though she had an overwhelming response from nurses who wanted to participate, in adherence with social distancing, she only accepted just three to four nurses at a time.

At the Central Florida Regional Hospital in Sanford, Louella Ellis, an ICU nurse, was a supporter of the protests as well. She says she is dedicated to her job but has her family to think about.

Ellis says that medical staff deserves to be prioritized over profit at a time like this, and that the hospital has an obligation to keep her safe while she works.

Ellis refers to a confusing flow of information they’ve received, something Lee also mentions. They both say they were first told not to wear masks at all. Then, they were told they could wear masks but had to provide their own. After that, they were told they couldn’t wear their own masks anymore. Now they’re being told they can wear “face bandanas.”

“There is no science behind that,” Ellis says. “Who’s saying this? Who’s making these decisions?” She says she believes the treatment of medical staff throughout this crisis has been insulting from all ends. She fears the U.S. will find itself with a shortage of its most essential workers if they become tired of the abuse.

“They are sacrificing us for cost because they didn’t prepare,” Ellis says. “And we’re sitting here looking at the President saying that we’re stealing masks – you’re going to have a lot of nurses who are going to leave the profession rather than do this job. And you’re going to run out of that precious commodity of nurses and doctors to take care of patients.”

Last week, President Donald Trump made public statements about N95 masks “going out the back door” of hospitals, suggesting that nurses were stealing supplies they need to work.

Trump’s suggestion falls short on validity when placed against the intense criticism and persistent clamors for aid coming from the American medical field at large.

The American Hospital Association, American Medical Association and the American Nurses Association collectively signed and published a letter to the President as early as March 21, asking that he use the Defense Production Act to “increase the domestic production of medical supplies and equipment” for hospitals.

Criticism has even come from within the administration. In a House committee hearing on COVID-19 test kits, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Anthony Fauci declared that America “is not really geared to what we need right now” to be prepared for this pandemic.“That is a failing,” he said. “Let’s admit it.”

Rep. Anna Eskamani of Florida’s District 47 says the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically increased her to-do list and that the No. 1 issue right now is managing the health crisis.

Eskamani says she subscribes to the idea that the economic crisis should not be addressed before the public health crisis. However, Lee says therein lies the root of the problem.

In the meantime, while the healthcare industry brings in a GDP of trillions every year, nurses are having to fashion their own medical protection gear with unsuitable items.

From wrapping double gowns around “I was insulted,”

Lee says of Trump’s suggestion that nurses were stealing masks. “It was a smack in the face. I couldn’t believe he said that.”

themselves to cover their entire bodies, to wearing surgical caps on their shoes – a simple Google search will yield plenty of photographs and articles showcasing the tragicomedy these nurses are living. Some even use visors as face shields, tape to seal their gloves, or trash bags to cover breathable nylon gear.

One of Lee’s co-workers just tested positive for coronavirus. The 28-year-old, whose identity she kept to herself, went on to infect his partner and their roommate. Lee says she wonders how many patients he could have potentially infected while treating them, as he was not told to stay home while awaiting his results.

Lee is immune-suppressed, with diabetes and high blood pressure. At her age (63), she could use that as a reason to stay home. She says she thinks of the extra workload on her co-workers, however, and of how it would impact the quality of care for the patients. So she decides to make that 45-minute drive to the hospital every shift, to sanitize and put on a useless surgical mask that she knows won’t keep her safe.

“You know why I go to work? Because I made an oath to take care of my patients and do the best I can,” she says. “I have to think about my patients first, me second. This is a sad way to think but, as a nurse, I feel that I’m invincible, and I have to go to work and take care of those patients that are ill.”

With a hint of faith in something greater, Lee says she is not afraid of becoming infected. What does concern her is what may be yet to come.

Sounding this alarm, Lee insists on leaving only one message behind:

“People, stay home,” she says. “Please, please, stay home, and stay safe.” feedback@orlandoweekly.com