DESIGN PROPOSAL

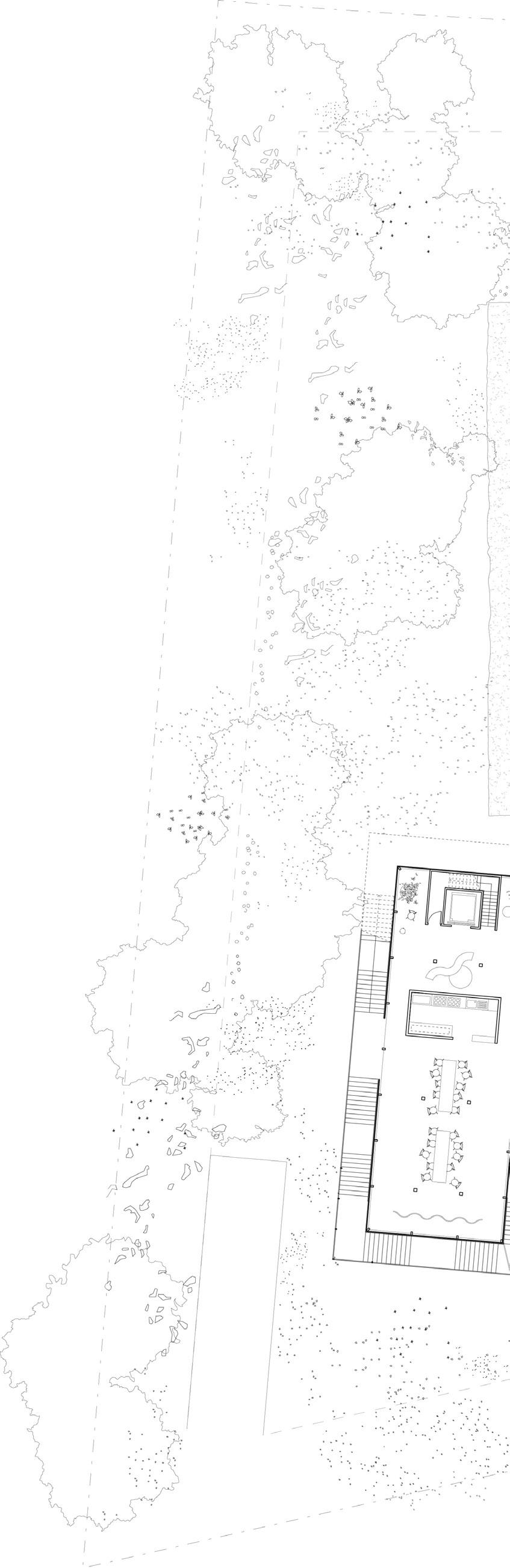

Site arrangement

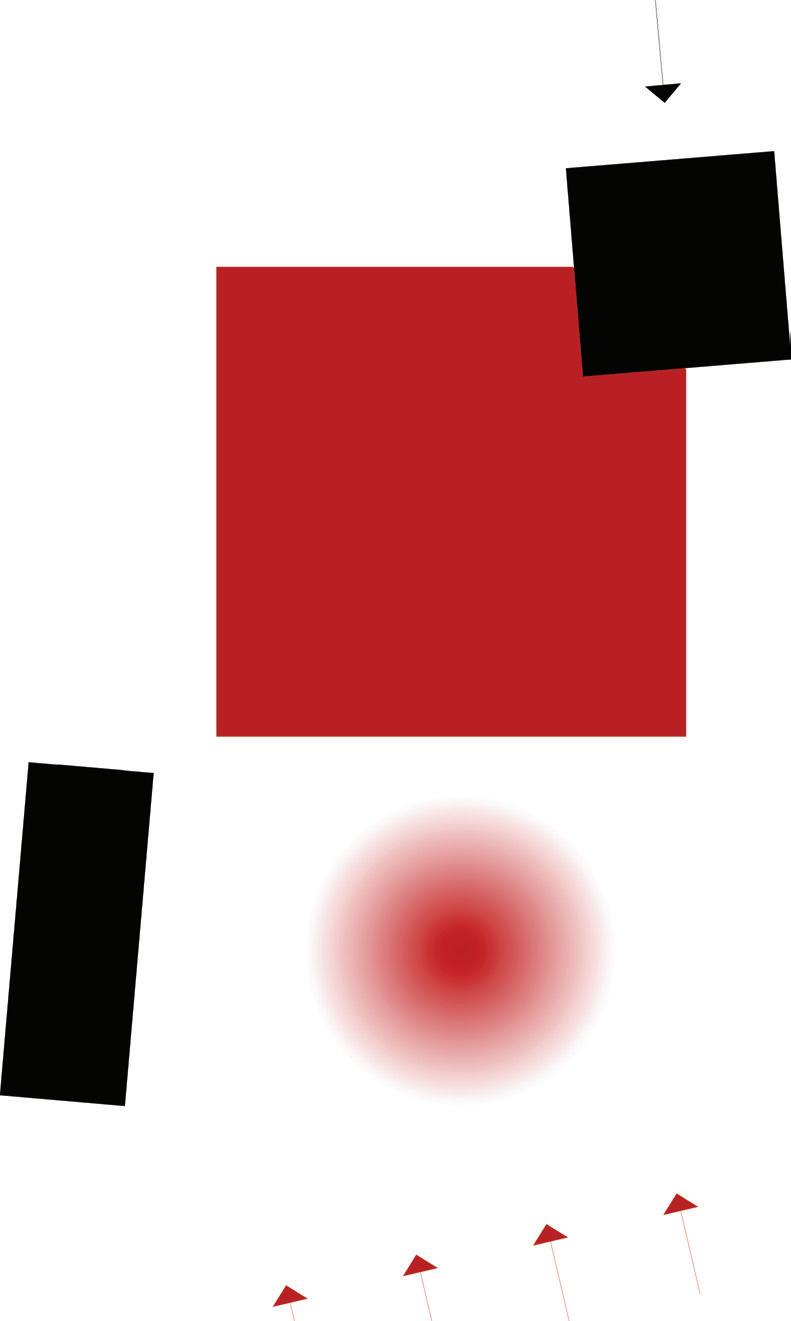

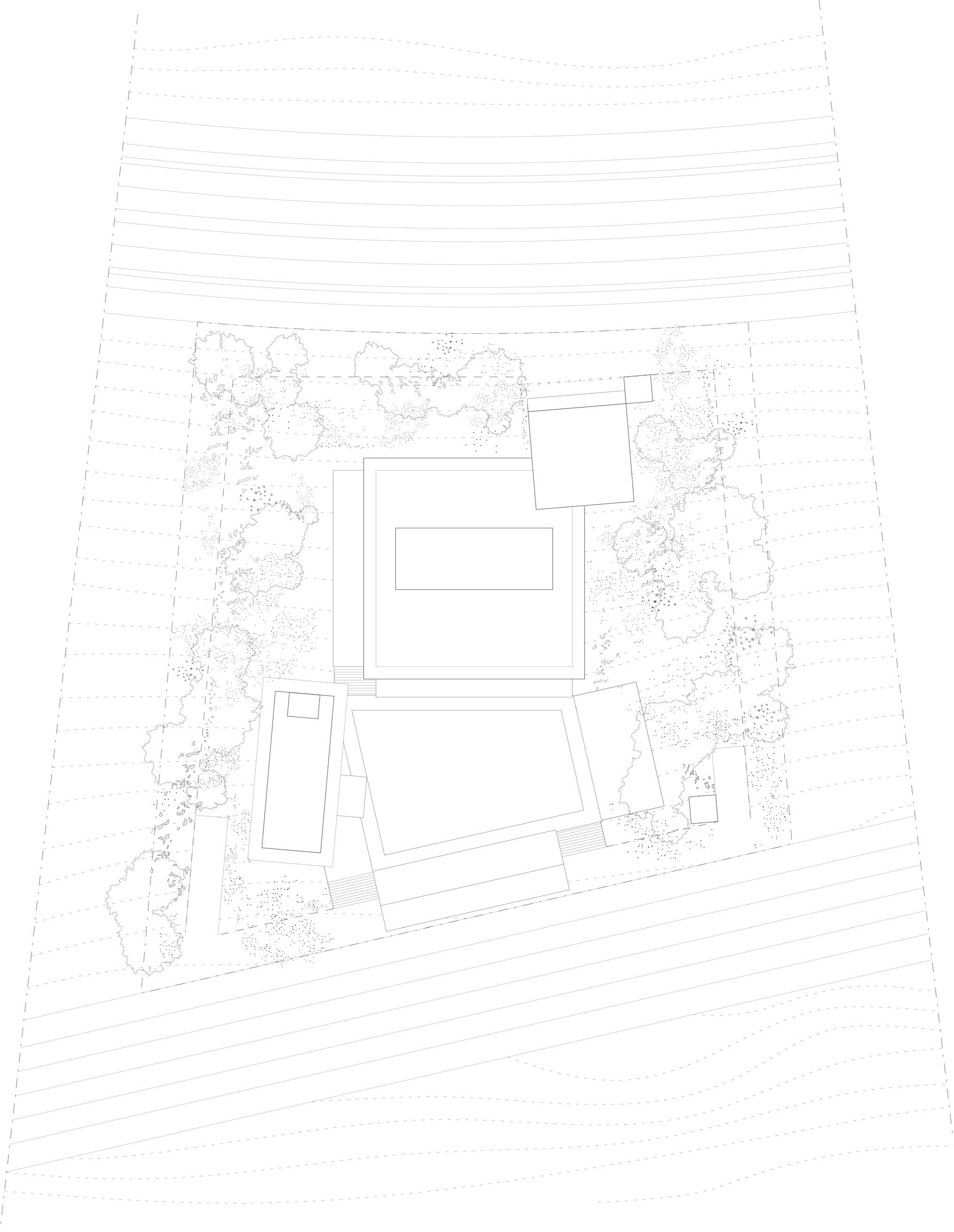

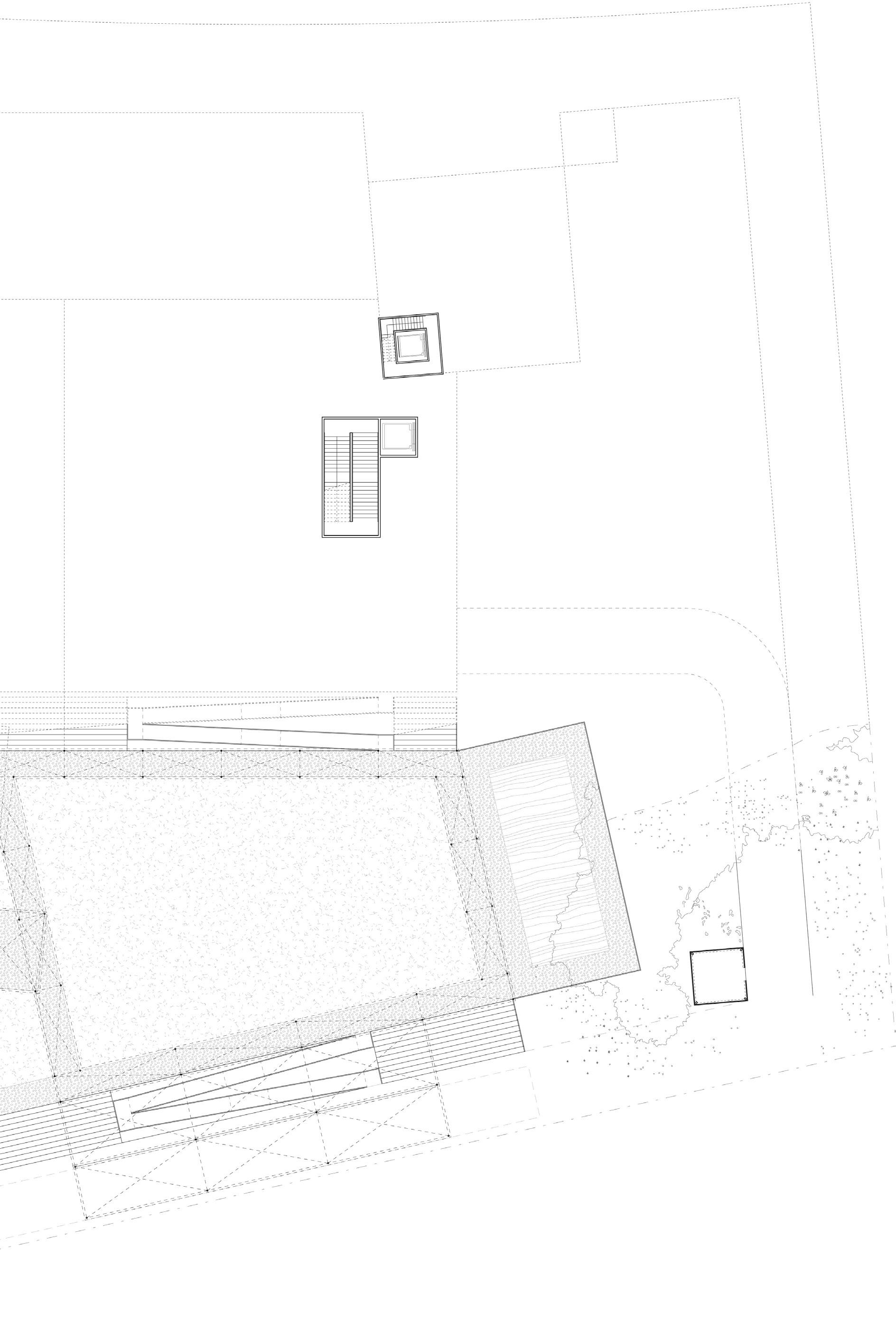

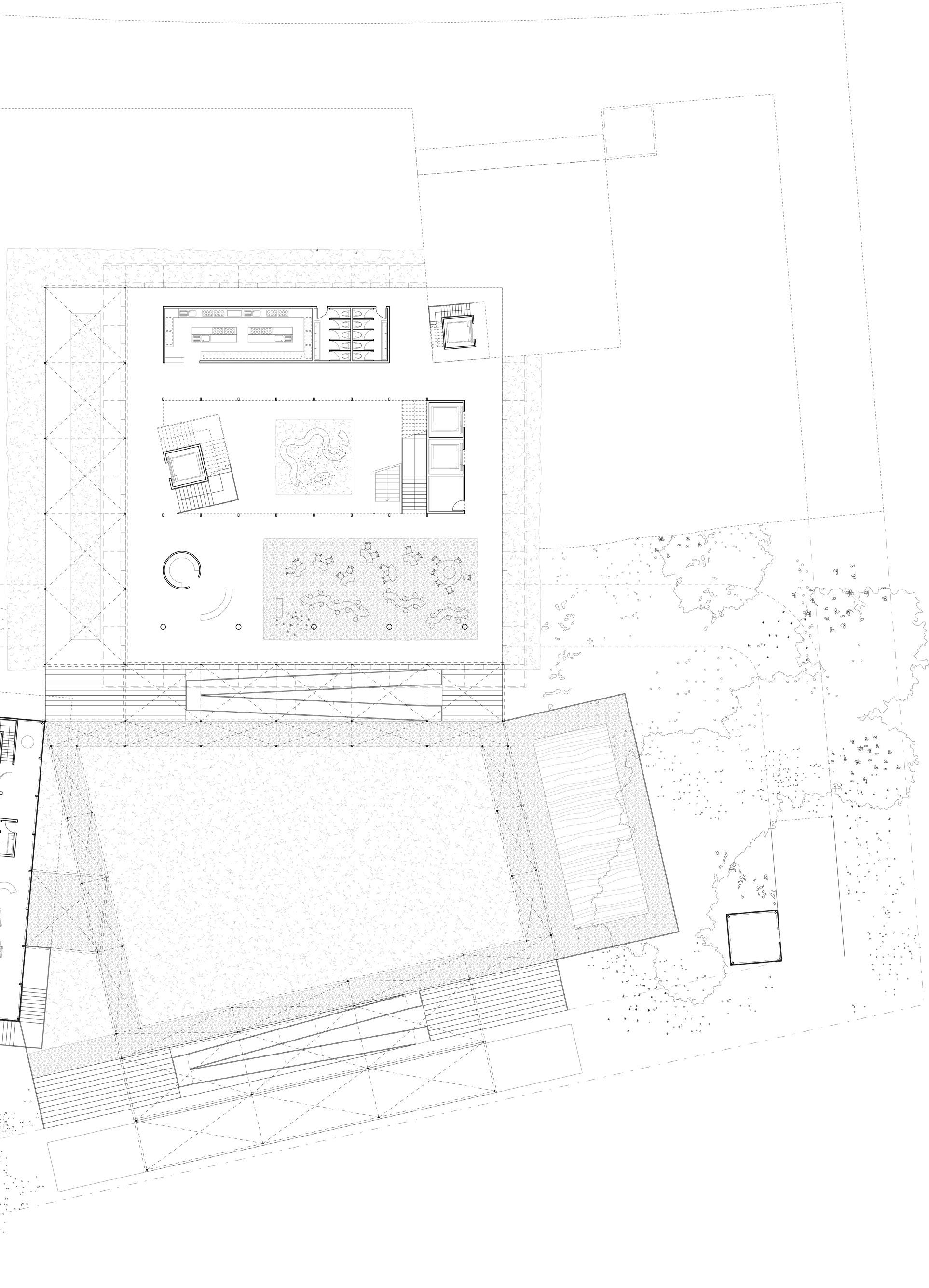

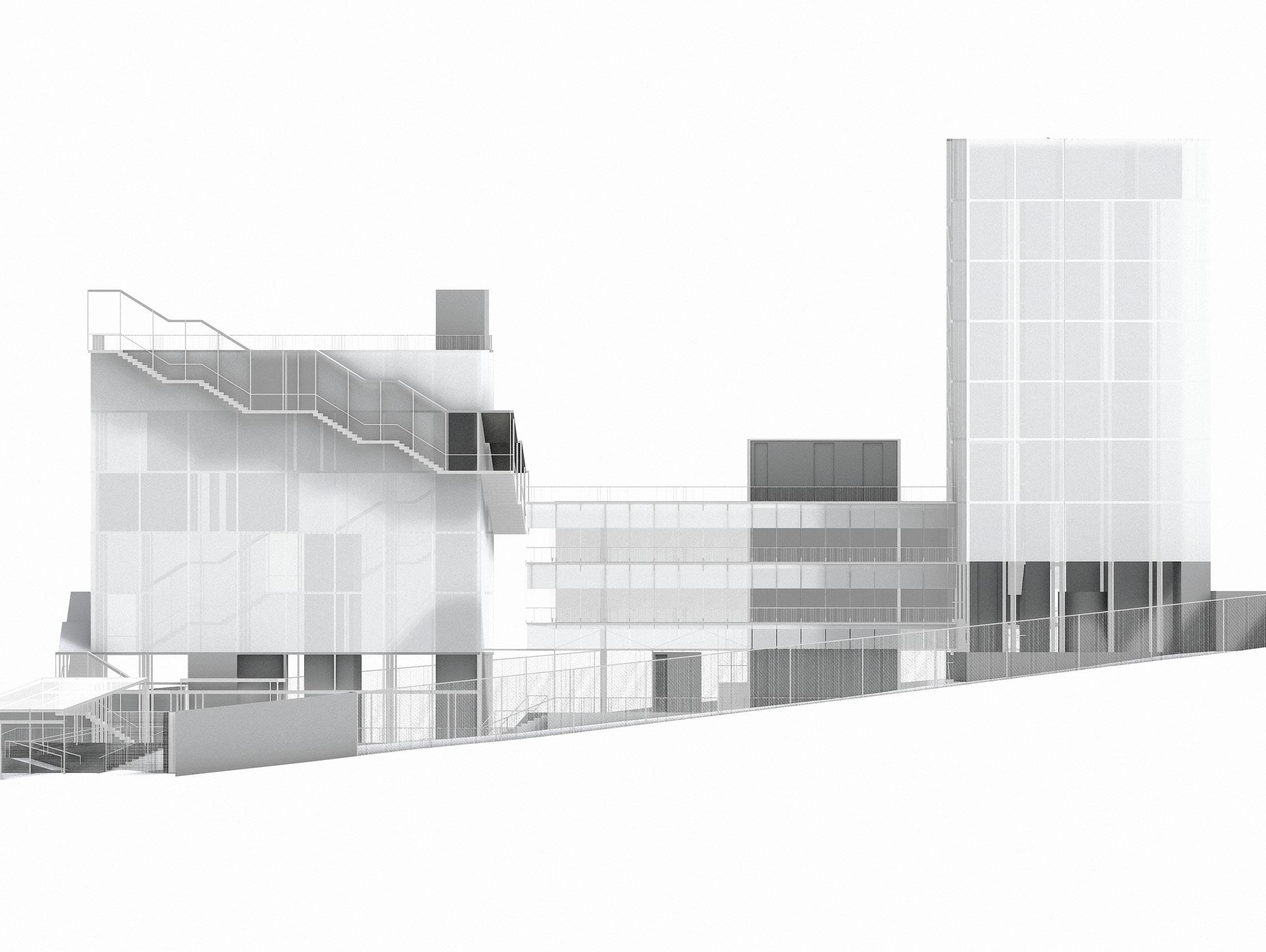

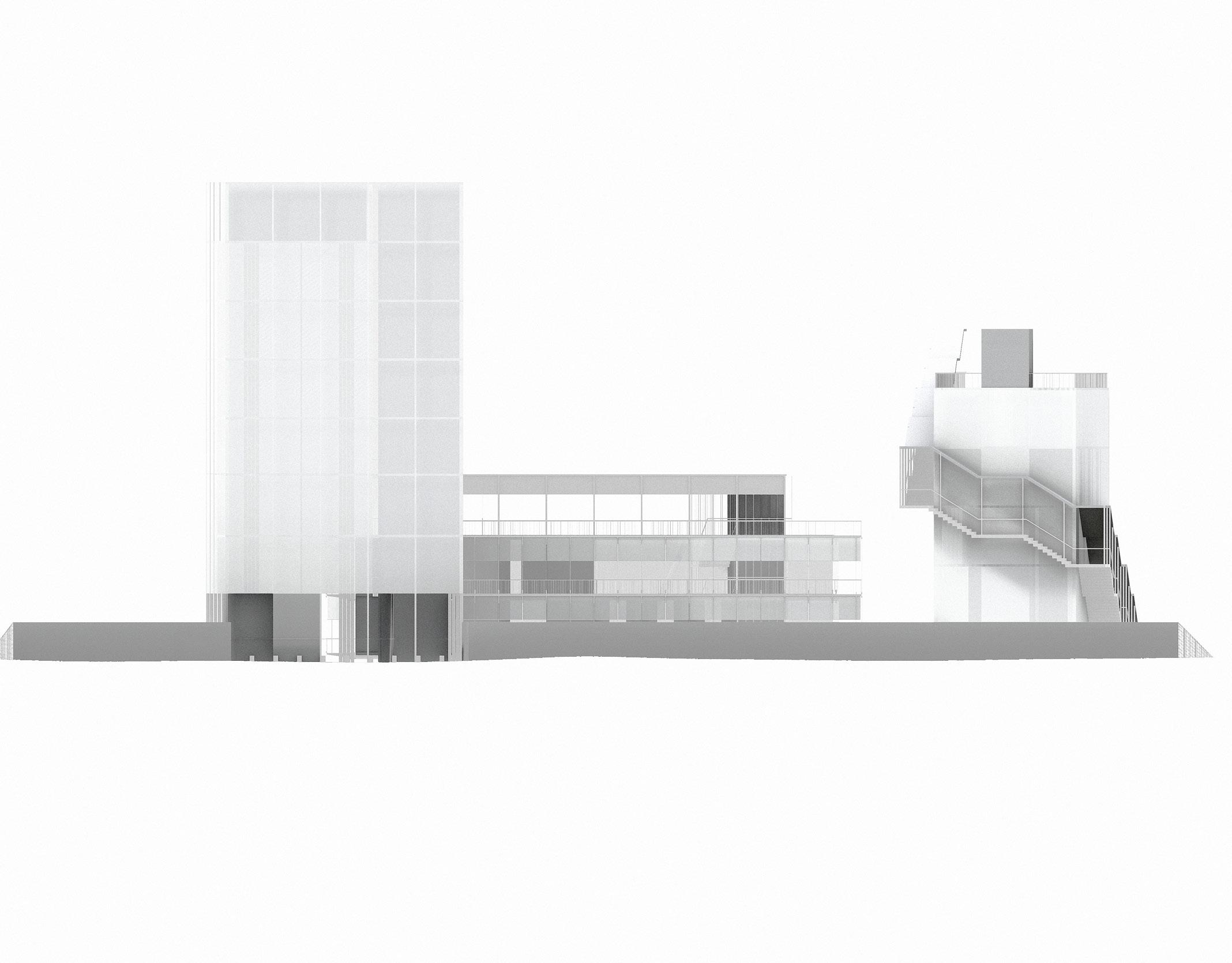

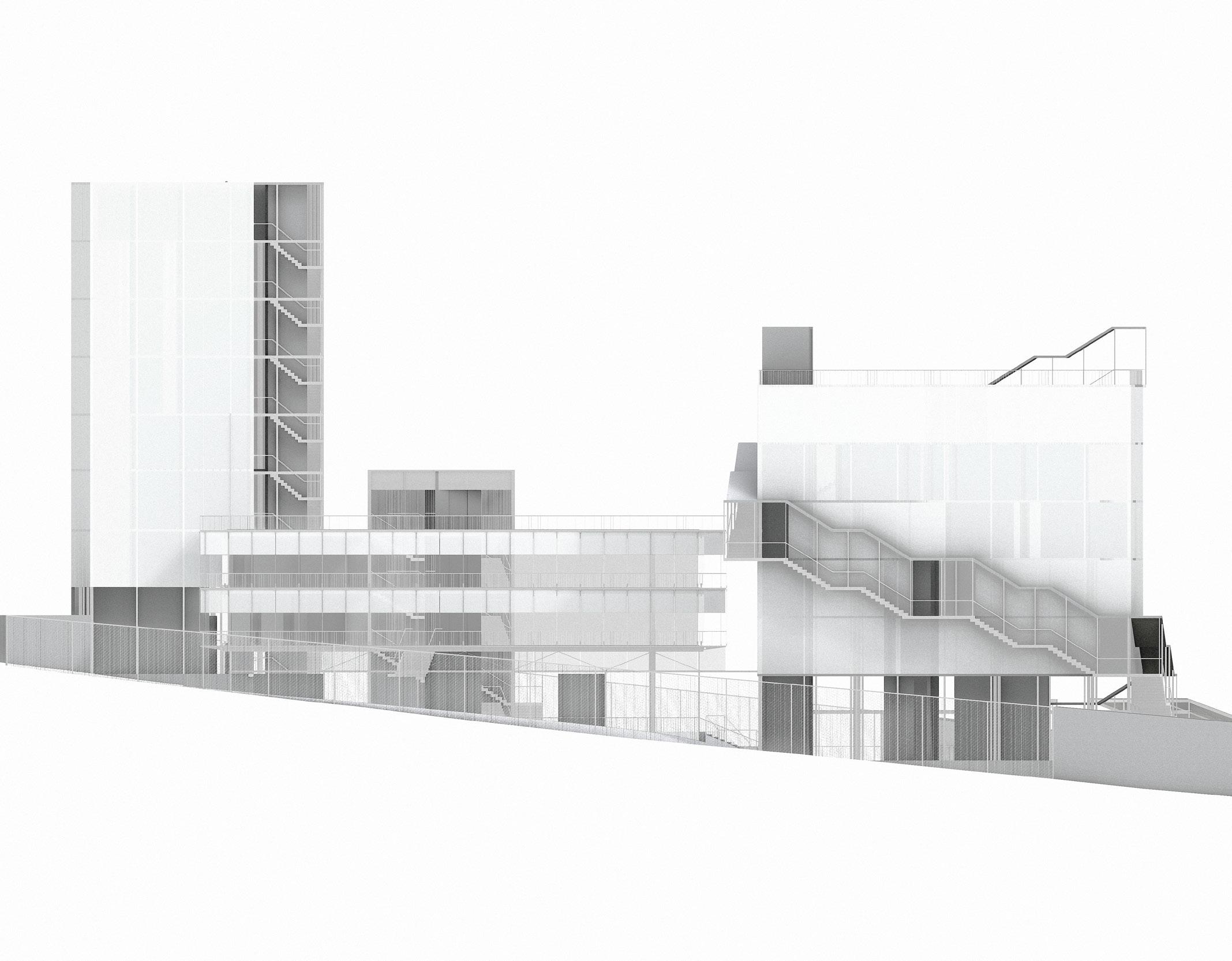

Centred around the alun-alun as the core element of the project, the site is divided into two sectors: the public realm (red) and the private realm (black), with the embassy programs arranged into three building masses. The public realm comprises the central alun-alun and parts of the chancellery sector, which includes the café/restaurant, function hall, library, farmhouse, consular section, and other complementary back-of-house facilities. This section of the site is accessible for all, guided from the grand entrance at the alun-alun, and has lower levels of security. The private realm includes two independent masses—the residence building and the office tower. The residence building is positioned close to the alun-alun due to its reception function, while the office tower is located at the back of the site for administrative purposes. These two buildings feature higher levels of security and are accessible only to relevant personnel; the office tower has a separate main entrance at the northern end of the site.

1. main entrance / drop off

2. ambassador’s residence entrance

3. alun-alun

4. cafe / restaurant

5. atrium garden

6. public toilet

7. function hall

8. consular section

9. library

10. consular office

11. rooftop farmhouse

12. carpark

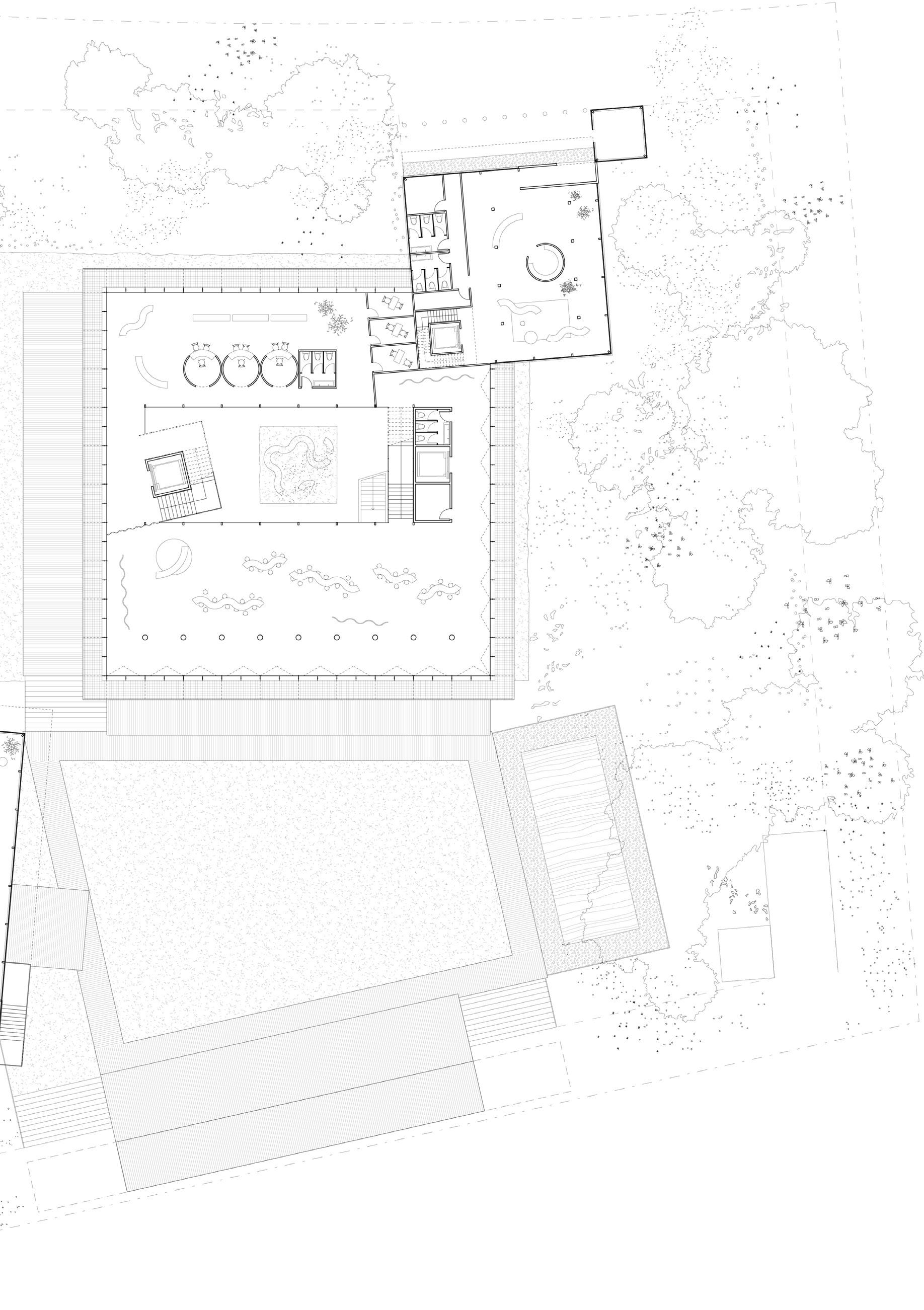

Program arrangement, public realm

The arrangement of programs in the public realm is organised from leisure-based activities to more administrative functions, progressing from south to north. The most publicly engaging program, the alun-alun, is positioned at the southernmost side of the site, adjacent to the grand entrance. It is followed by the café/restaurant, farmhouse, function hall, and library, layered on top of one another, with the consular section placed at the northernmost end of the public realm. Vertically, spaces that are likely to receive more visitors (higher influx) are arranged at lower levels, with quieter programs positioned at higher levels. Similarly, the spatial quality of these programs transitions from fully open to fully enclosed, moving from south to north and from lower to higher levels.

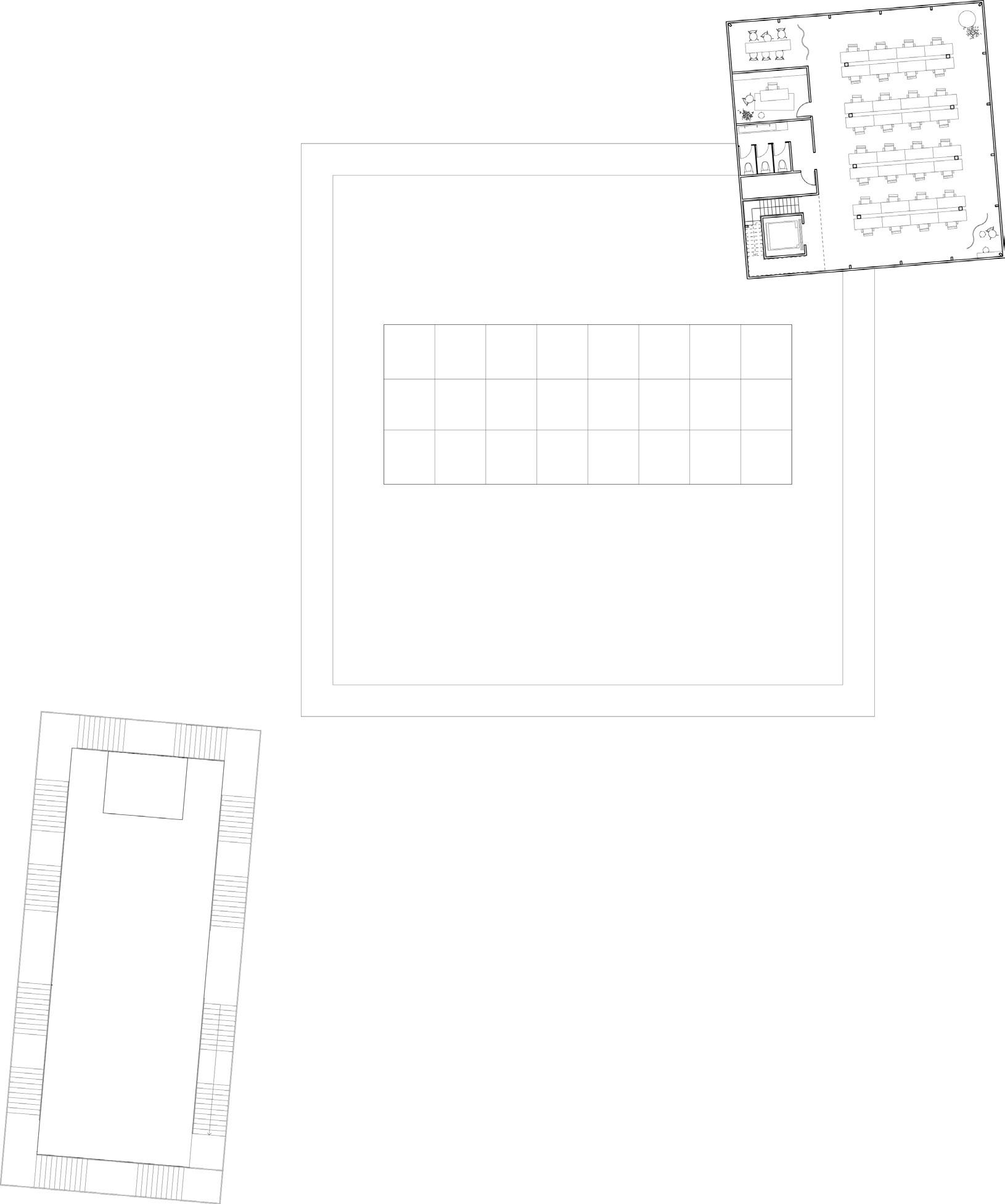

1. alun-alun

2. ambassador’s lobby + gallery

3. salon

4. ambassador’s public dining

5. staff residence

6. ambassador’s bedroom space

7. ambassador’s private living

8. rooftop garden

9. carpark

Program arrangement, the residence building

The program distribution of the residence building follows a logic where more public spaces are placed at lower levels and more private spaces at higher levels. The lobby/gallery space, salon, and public dining area are arranged respectively from ground level to level 2, designed for diplomatic receptions and thus more public in nature. Juxtaposed with the open ground, these spaces share the openness of the alun-alun. The staff residence, ambassador’s bedroom, and living spaces are arranged respectively from levels 3 to 5. These private spaces are designed to have quieter quality and are hence distant from the vibrancy of the ground level while enjoying views to the south as the site slopes downwards.

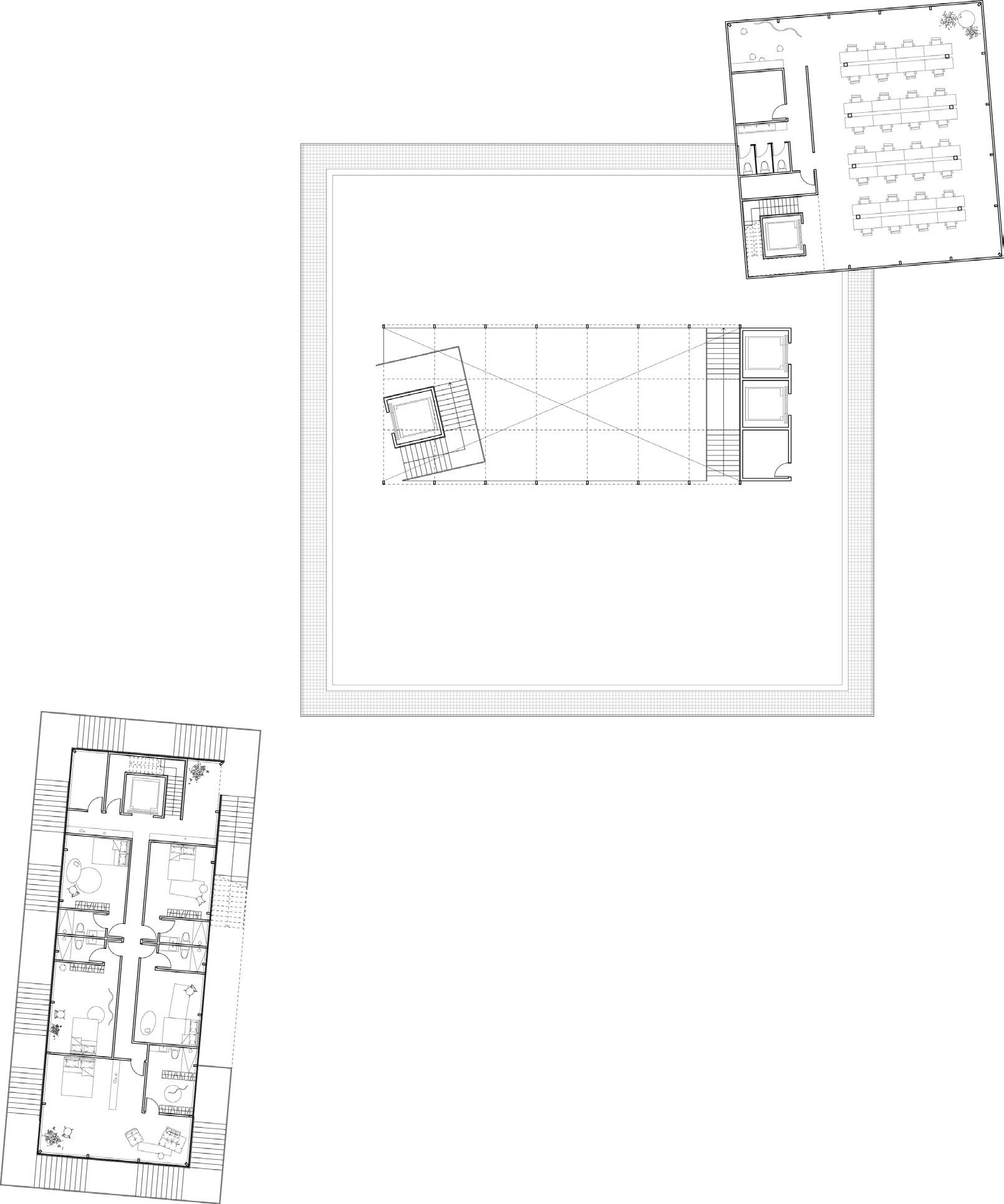

1. carpark entrance

2. public carpark

3. plantroom

4. ambassador carpark

5. staff carpark

6. public circulation core

7+8. plantroom

9. office circulation core

10. carpark exit

Carpark

The carpark is entirely underground, with entrances and exits located at the corners of the grand entrance. It is divided into three sections, each with independent circulation cores linked to the programs above ground— namely, the public building, the residence building, and the office tower. The public section is accessible to all, featuring 10 vehicle parking spaces and 22 motorbike parking spaces. The residence parking section is designed exclusively for the ambassador and family, with 2 vehicle and 3 motorbike parking spaces. The office parking section is designated for staff at the office tower, featuring 16 vehicle and 8 motorbike parking spaces. Additionally, key plant rooms and storage spaces are arranged on this level.

1. main entrance / drop off

2. alun-alun

3. screening room

4. ambassador’s residence lobby

+ gallery space

5. gatehouse

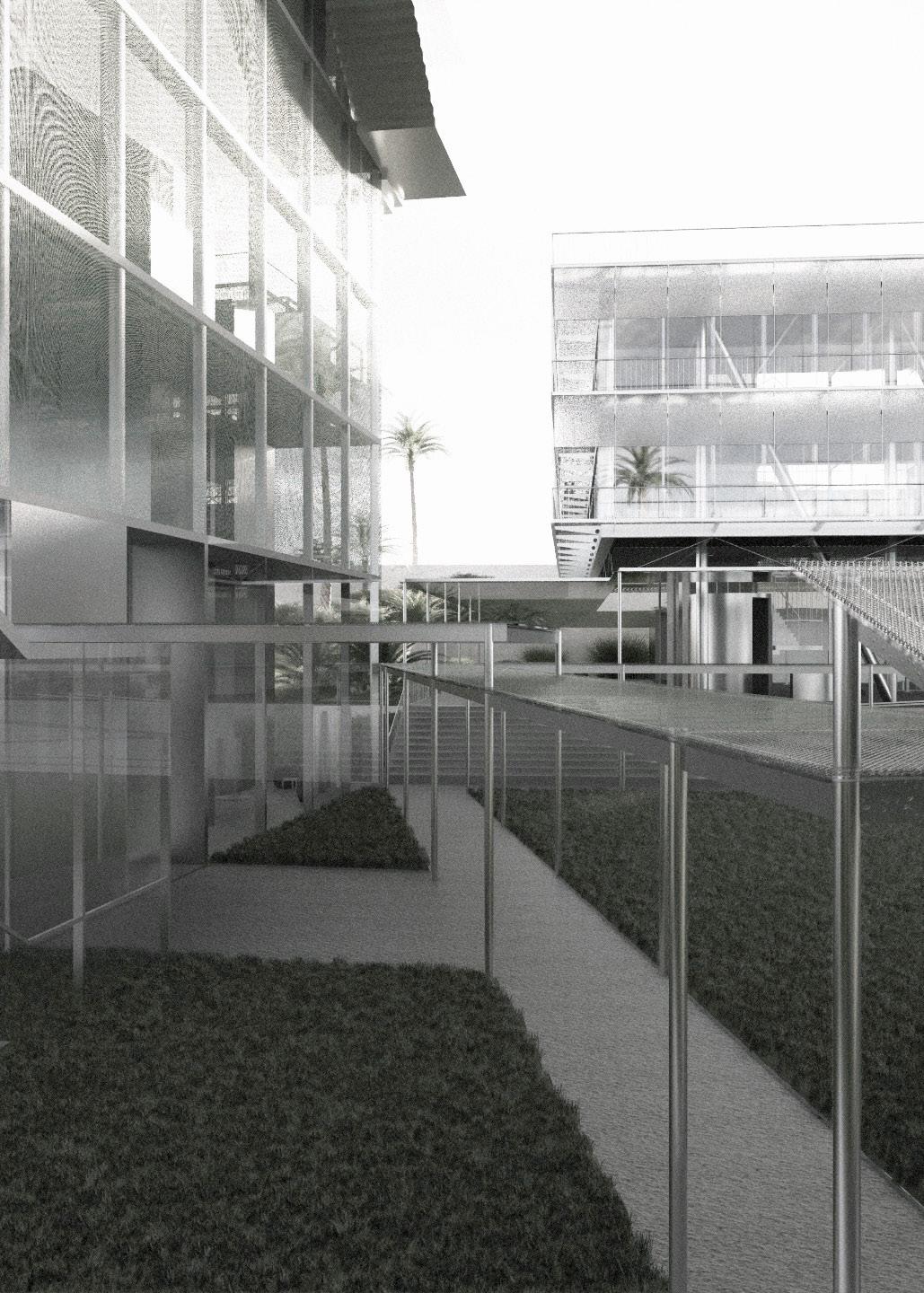

The grand entrance of the site is marked by ascending staircases leading to the central alun-alun and a shaded drop-off area for arriving visitors. The shade then extends as a long, open-air corridor around the alunalun, guiding access to different sectors of the site. The alun-alun itself is a flat, open-air lawned common, designed to flexibly accommodate various events similar to a traditional alun-alun, including festive celebrations like Grebeg Maulud and Koningsdag, performances such as Wayang Kulit, and Sunday markets. The eastern end of the alun-alun includes a water plaza, which further enhances the liveliness of the space. The entrance of the residence building is marked by a slightly raised shade, leading to the screening room to ensure building security. The ground floor of the residence building features a transparent façade, inviting visitors at the alun-alun to view the gallery space at the lobby level.

Shading is designed along the perimeter of the alunalun to accommodate the pluvial climate of Nusantara. Additionally, the façade at ground level is transparent compared to the upper levels, inviting visitors to see into the gallery space at the lobby level.

render image entrance of the main building

This image shows the transition from the alun-alun to the main building is marked by raised shading and ascending staircases. This image also highlights the materiality of the project, where the use of exposed steel structural elements reflects the Dutch value of efficiency, while the transparent features align with the concept of openness.

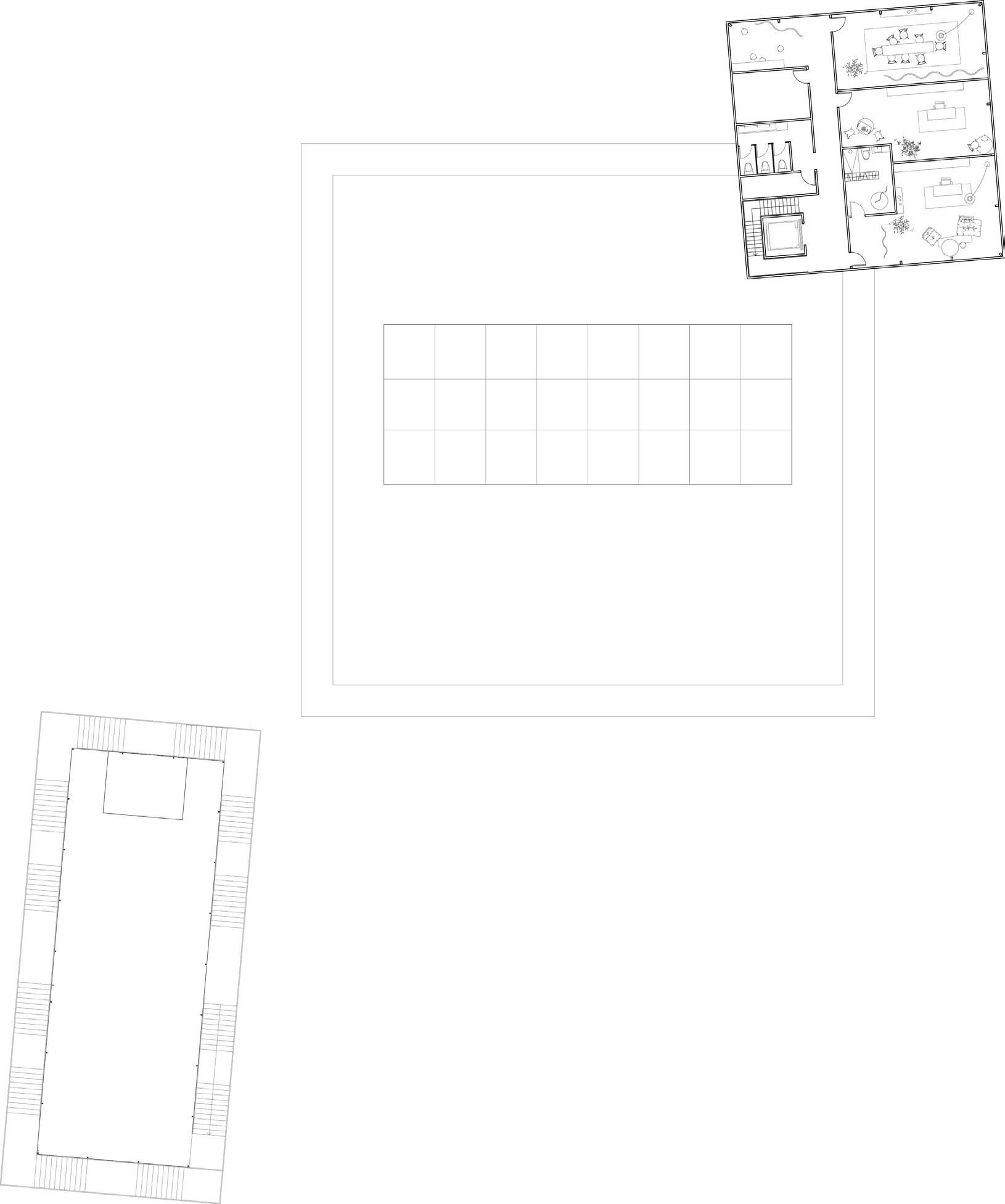

1. main entrance / drop off

2. alun-alun

3. salon

4. kiosk

5. cafe / restaurant

6. mailroom

7. consular section circulation

8. storage

9. public space circulation

10. carpark circulation

11. kitchen

12. public toilet

13. office circulation

14. atrium garden

A kiosk is positioned at the entrance of the public building, where this feature could guide visitors to their intended destinations—for instance, the consular section located in the northern half of the building or the function hall on the level above. The café/restaurant is also placed at the front of the public building, designed as a casual space where visitors can socialise and relax while enjoying views of the alun-alun. The central atrium is a circulation space that houses two independent cores: the western one serving the consular section, and the eastern one serving other public spaces. Back-ofhouse functions, such as the kitchen and public toilets, are located at the northern end of this level. A circulation core at the north-eastern corner of the building allows staff to access the office tower if they entered the site from the alun-alun rather than the office entrance at the northern perimeter.

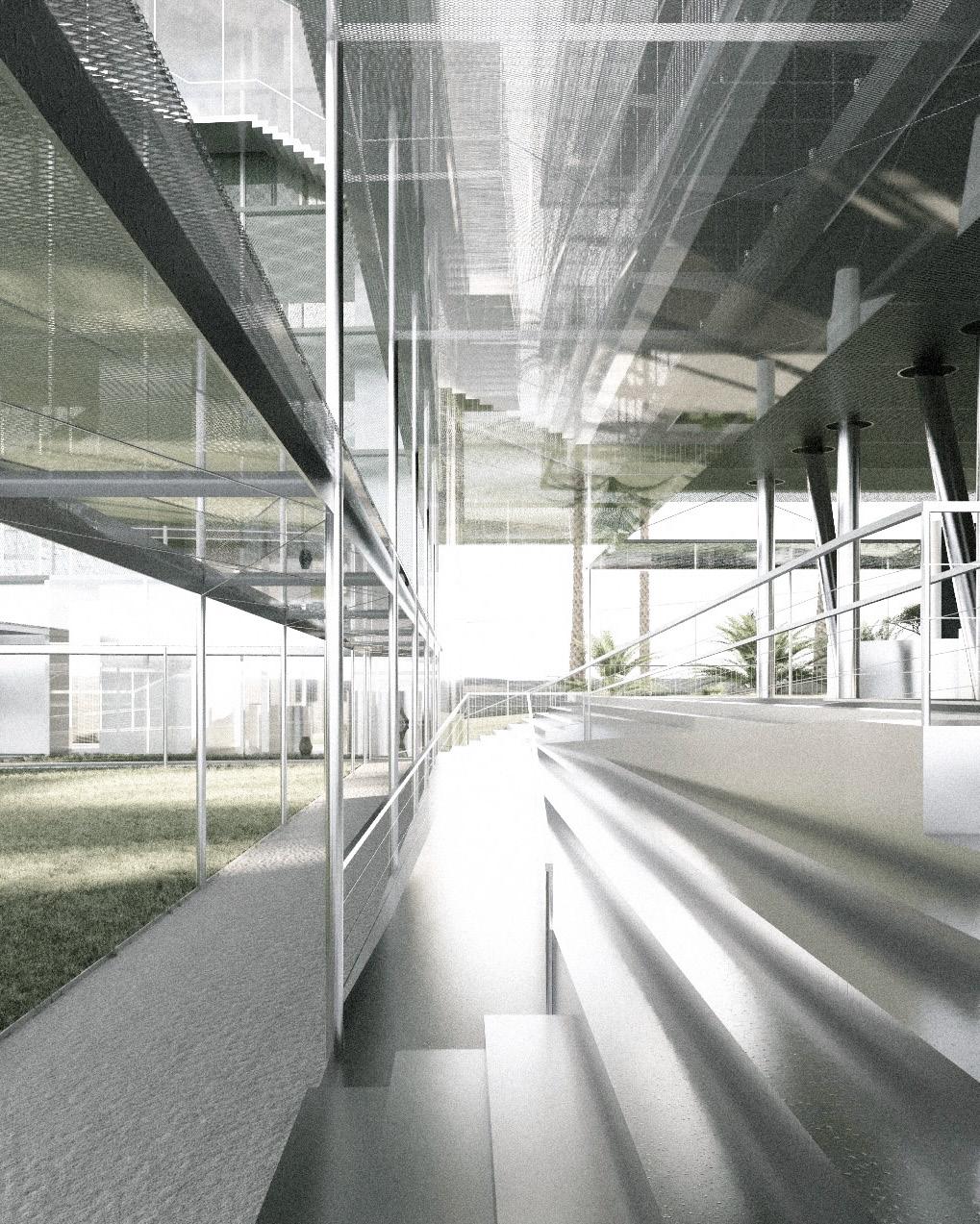

This image depicts the central atrium of the public building. Note that activities within and around this void are transparent, reflecting the intent of enlisting occupant movement to add liveliness to the space. The prominence of the circulation element also contributes to the concept of liveliness.

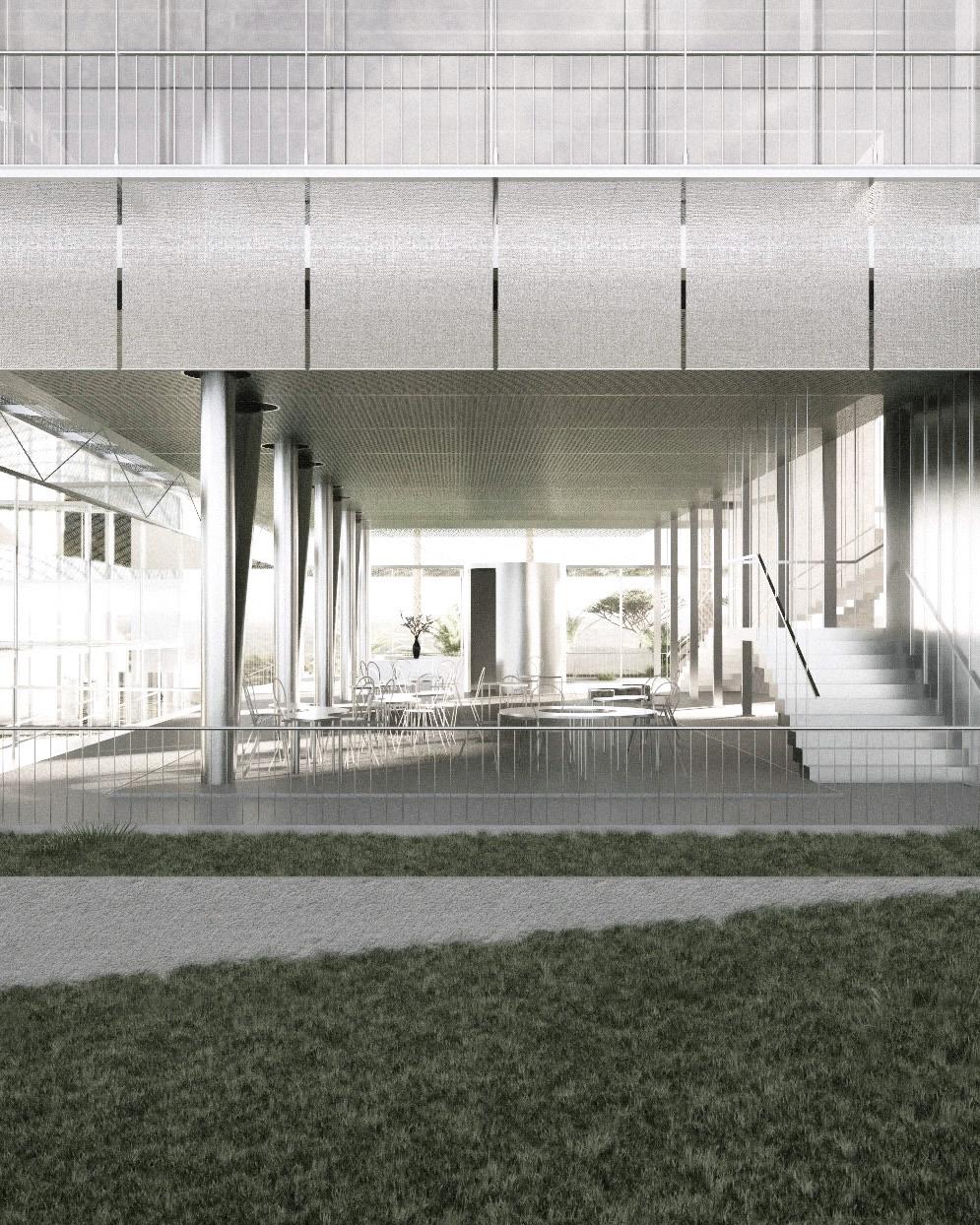

This image is of the entrance space of the public building, with the café/restaurant in the foreground. Note the space is entirely open-air, which responds to the humid climate of Nusantara while creating a spacious and transparent atmosphere that reflects the concept of openness.

1. office entrance

2. screening room

3. office lobby

4. plant room

5. storage

6. function hall

7. storage

8. consular section

9. counter

10. interview room

11. ambassador’s public dining

12. servery

Due to the sloping contours of the site, the office tower entrance is located at this level. The office entrance displays heightened security, with a gatehouse, bollards, and a screening room when entering the building. The clear division between the consular section and other public functions within the public building is also evident in this drawing.

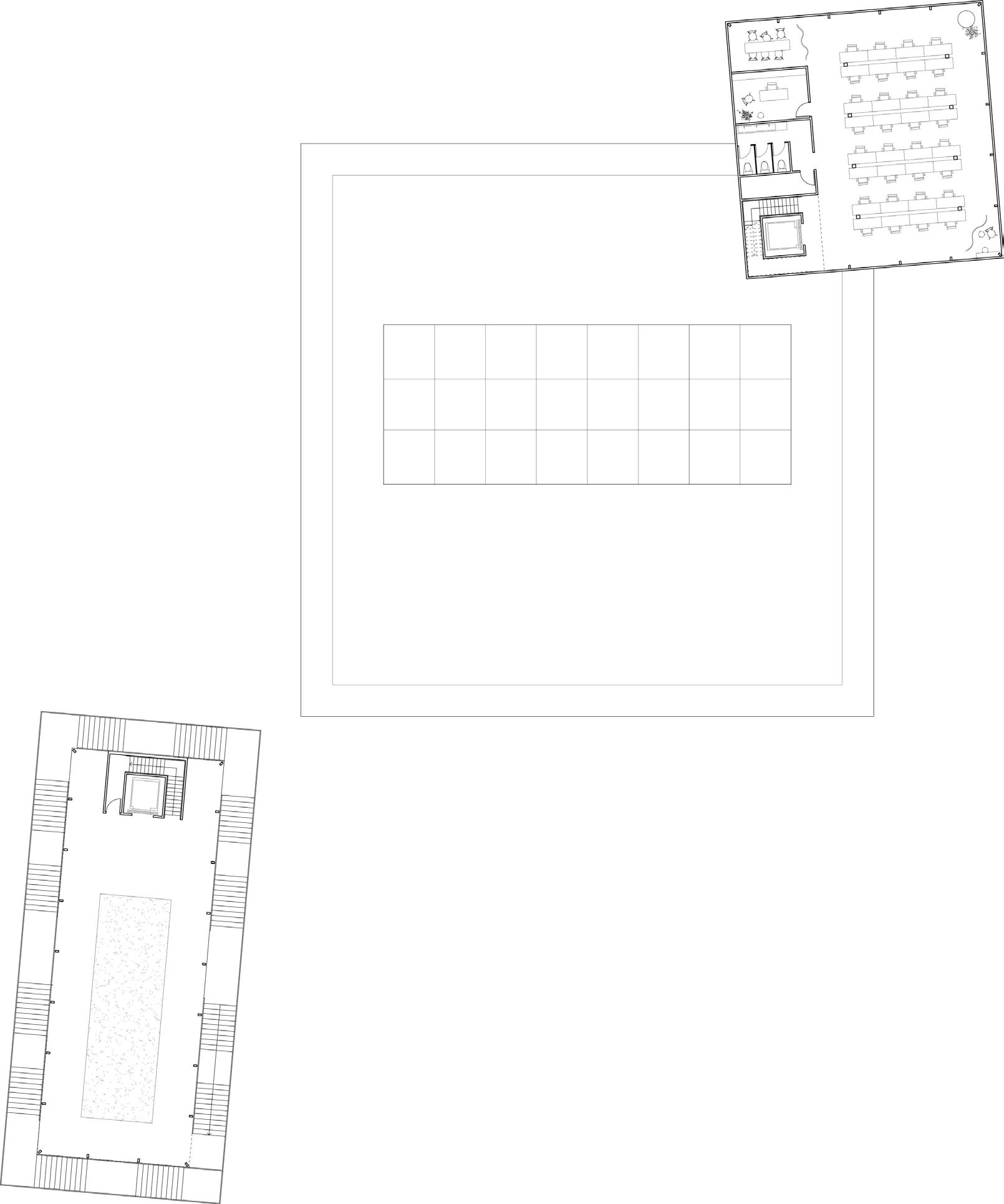

1. library

2. seminar room

3. storage

4. consular’s back office

5. tea point

6. deputy consul’s office

7. consul general’s office

8. open plan office

9. tea point

10. plantroom

11. storage

12. staff private residence

13. study

14. bedrooms

15. storage

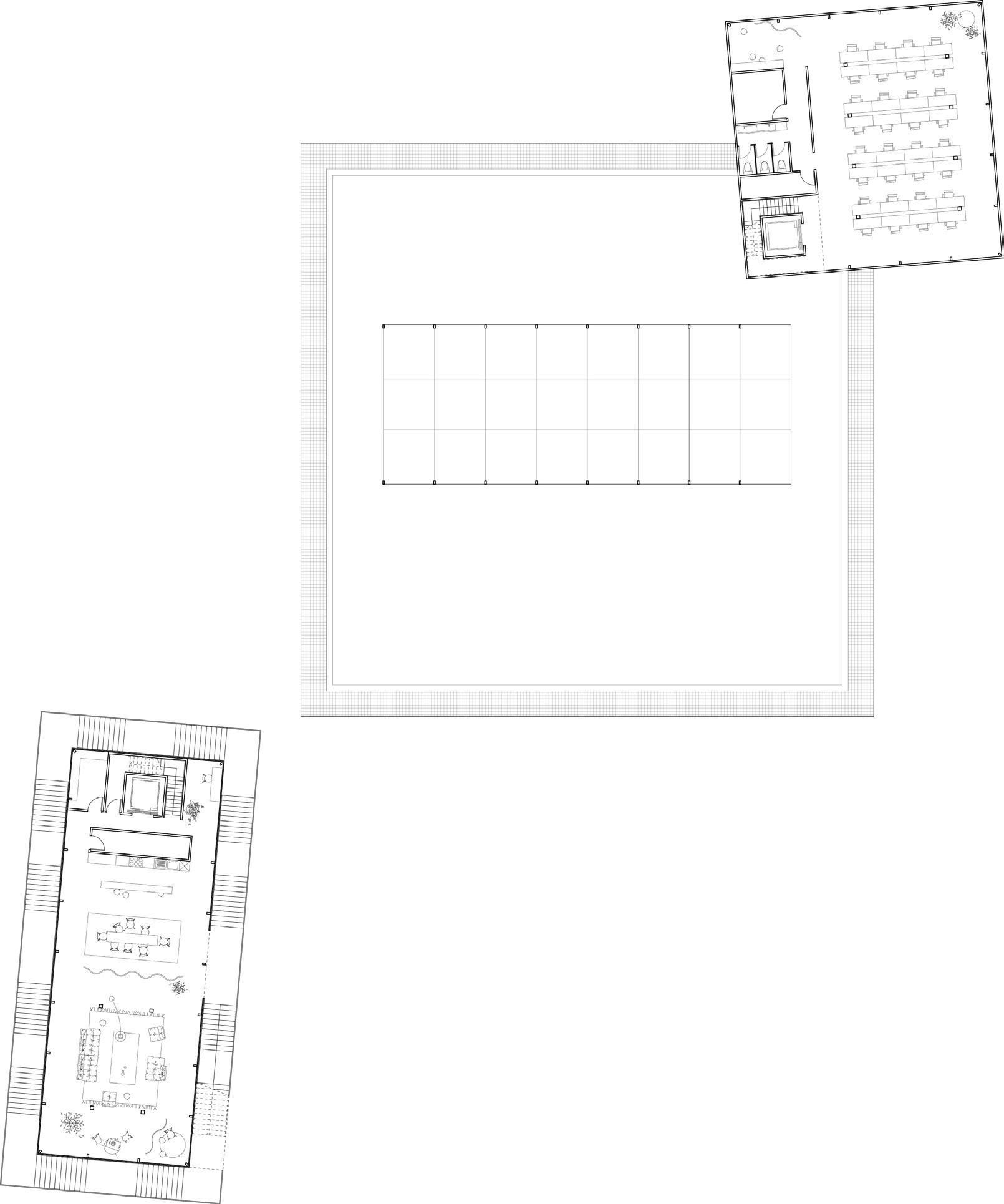

1. rooftop farmhouse

2. office

3. ambassador’s bedroom space

4. storage

5. bedroom

6. guest bedroom

7. master bedroom

1. office

2. ambassador’s private dining

3. ambassador’s private living

4. kitchen

5. study 6. storage

1. ambassador’s office

2. chief of staff office

3. meeting room

4. tea point

5. storage

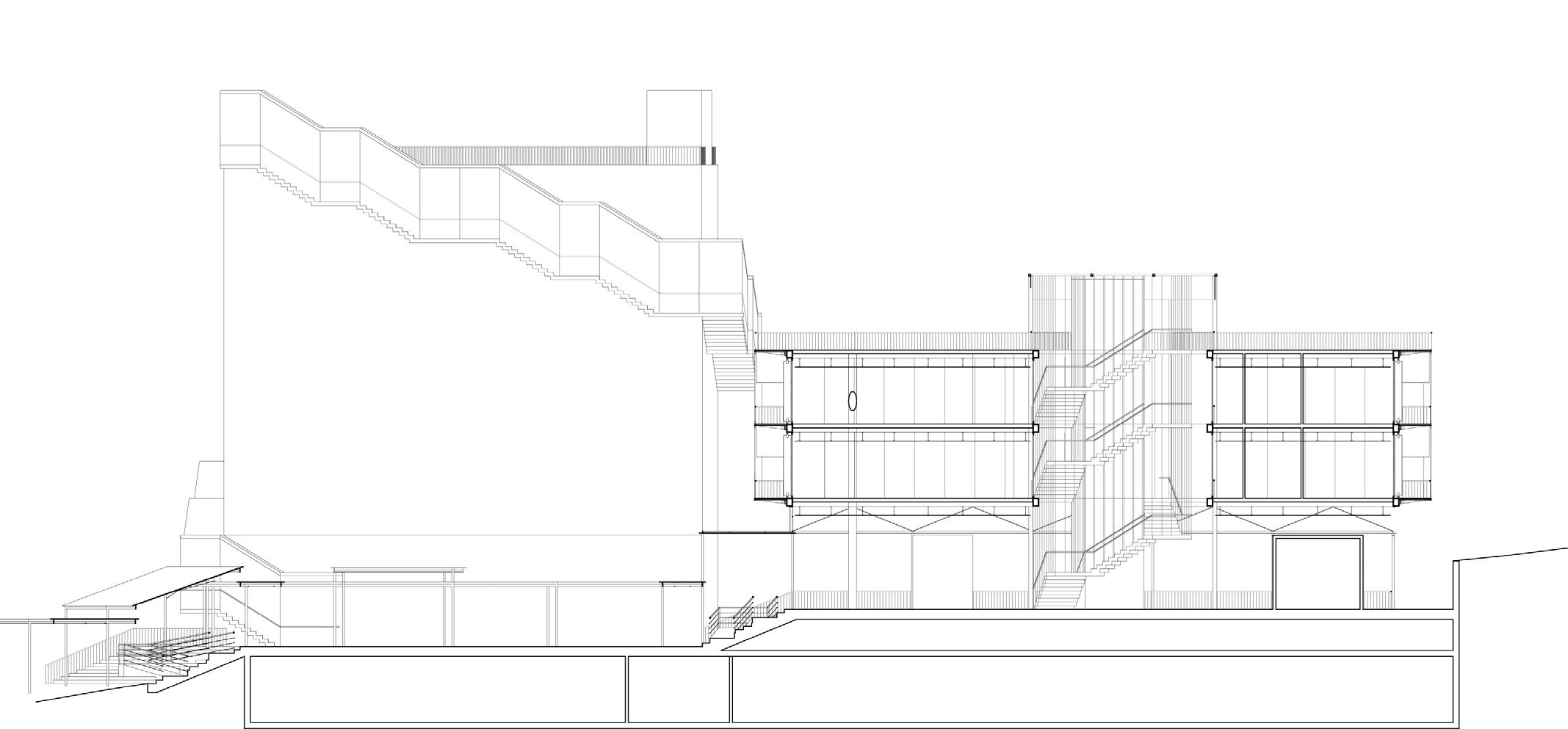

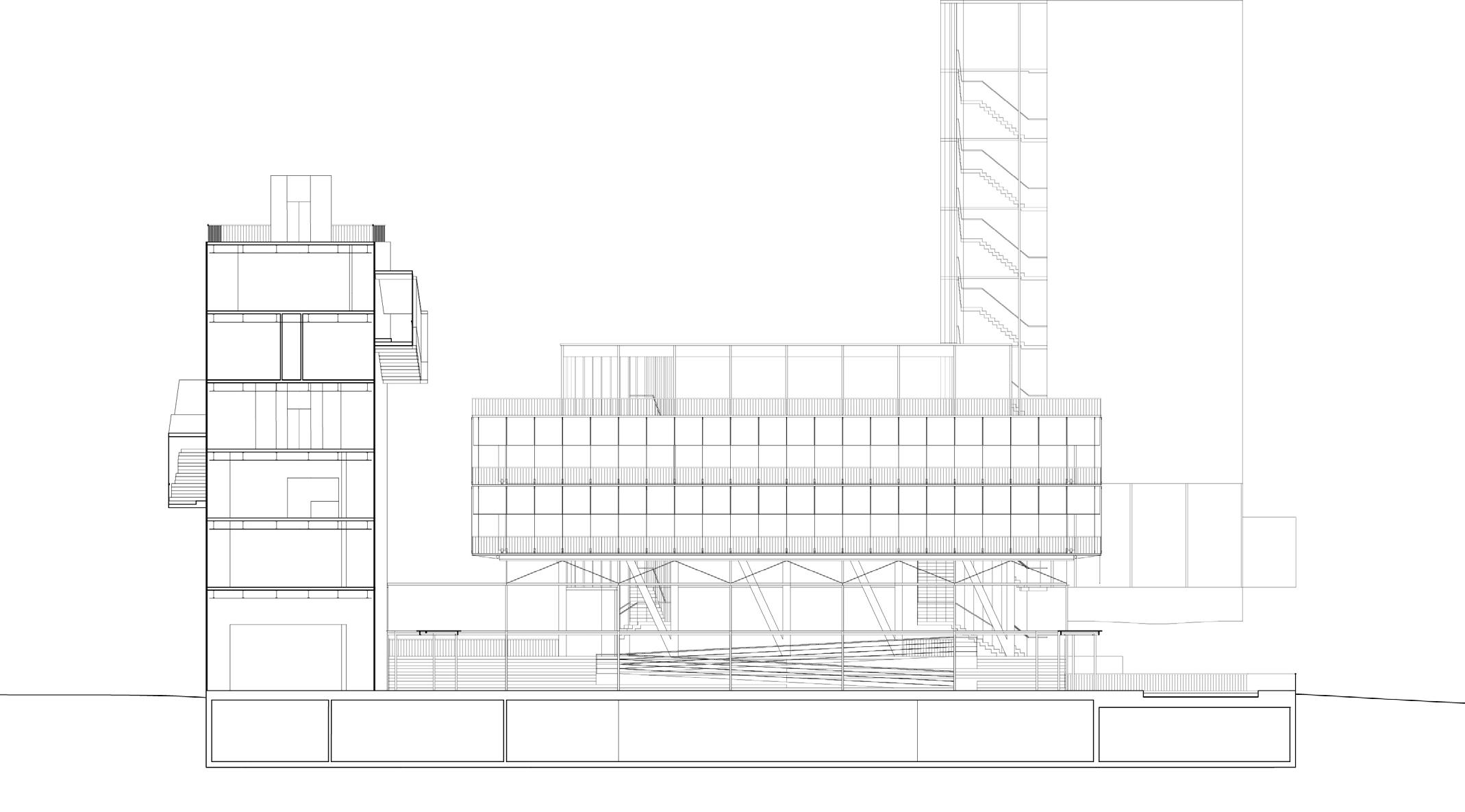

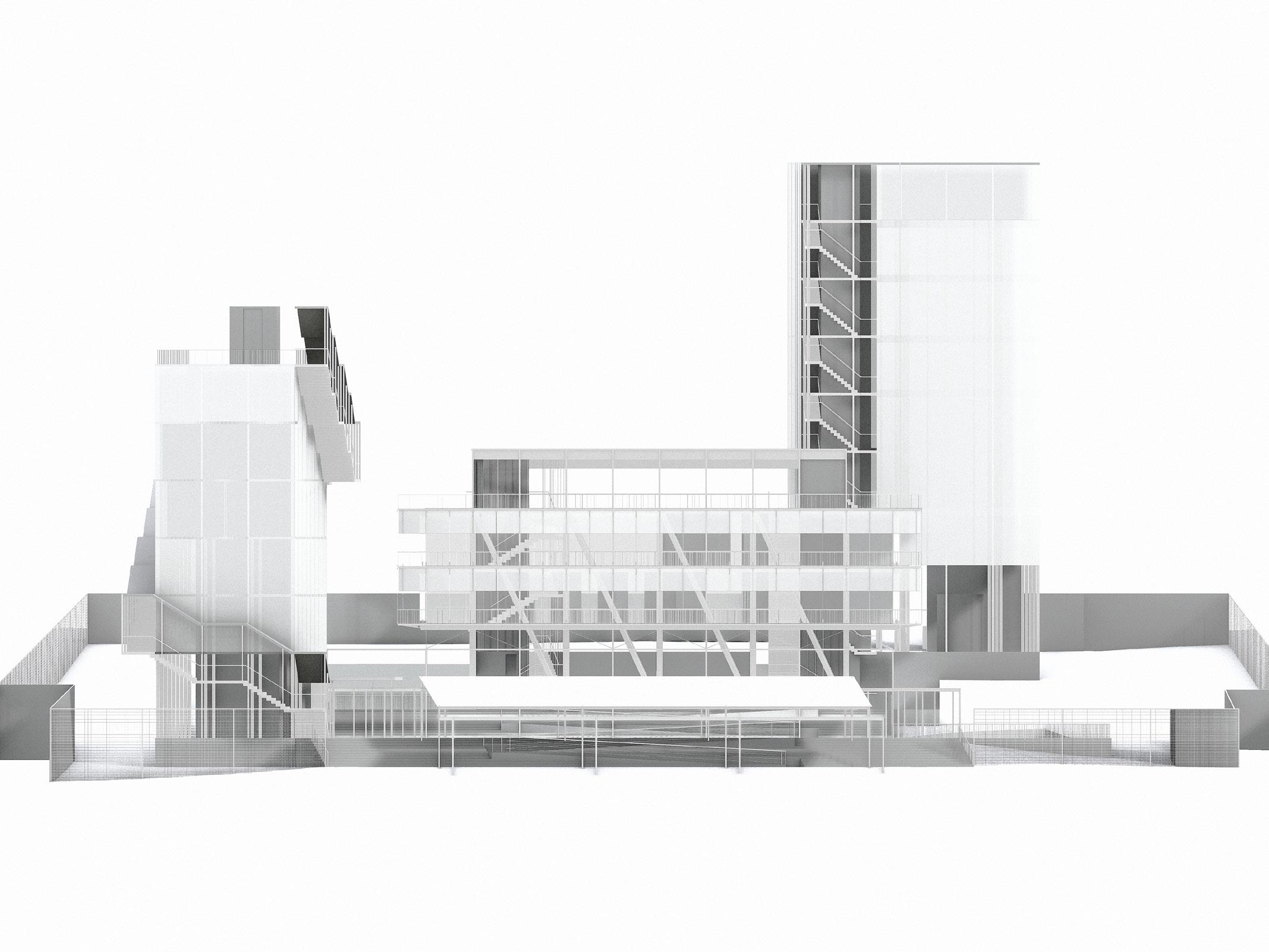

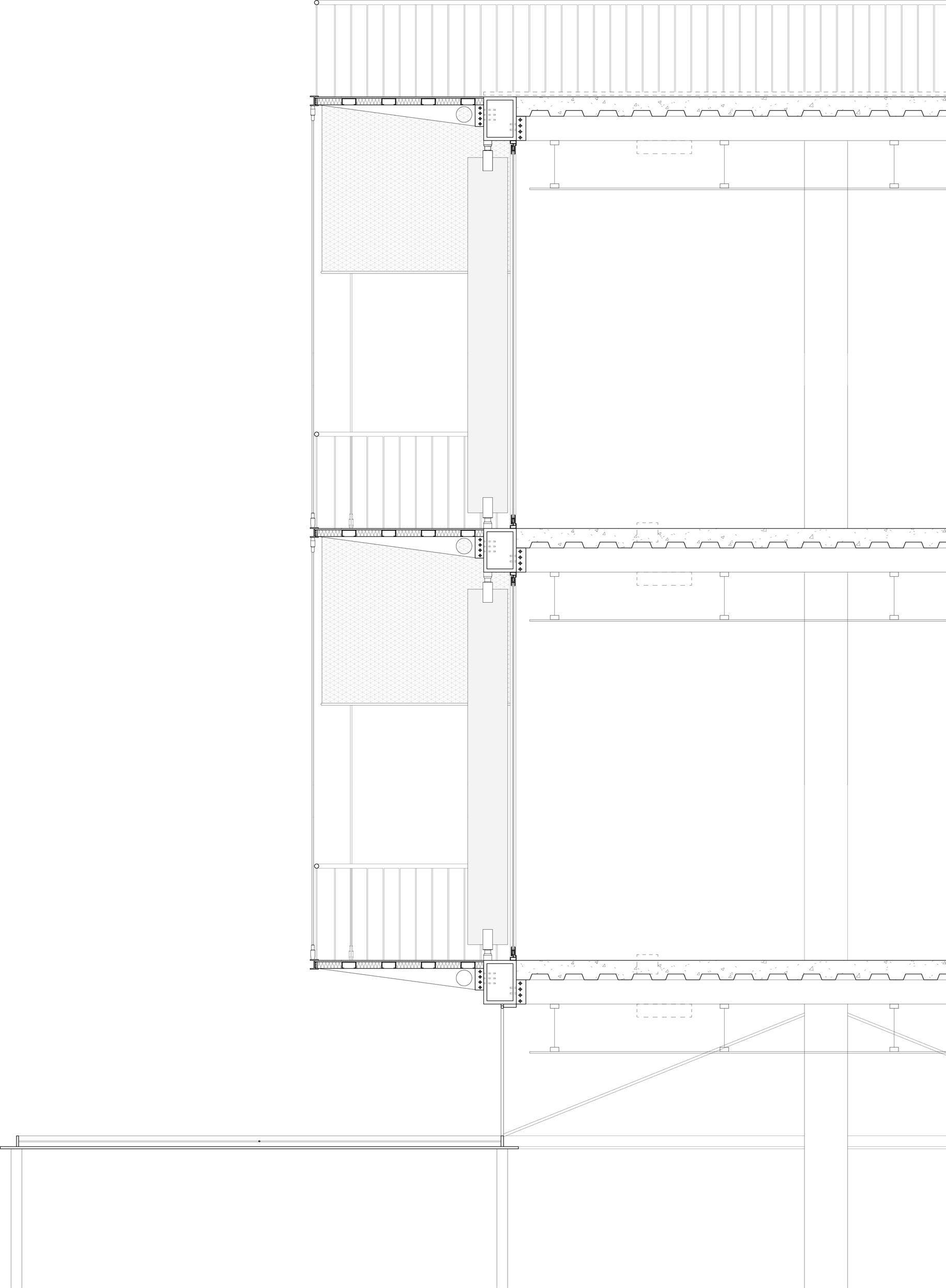

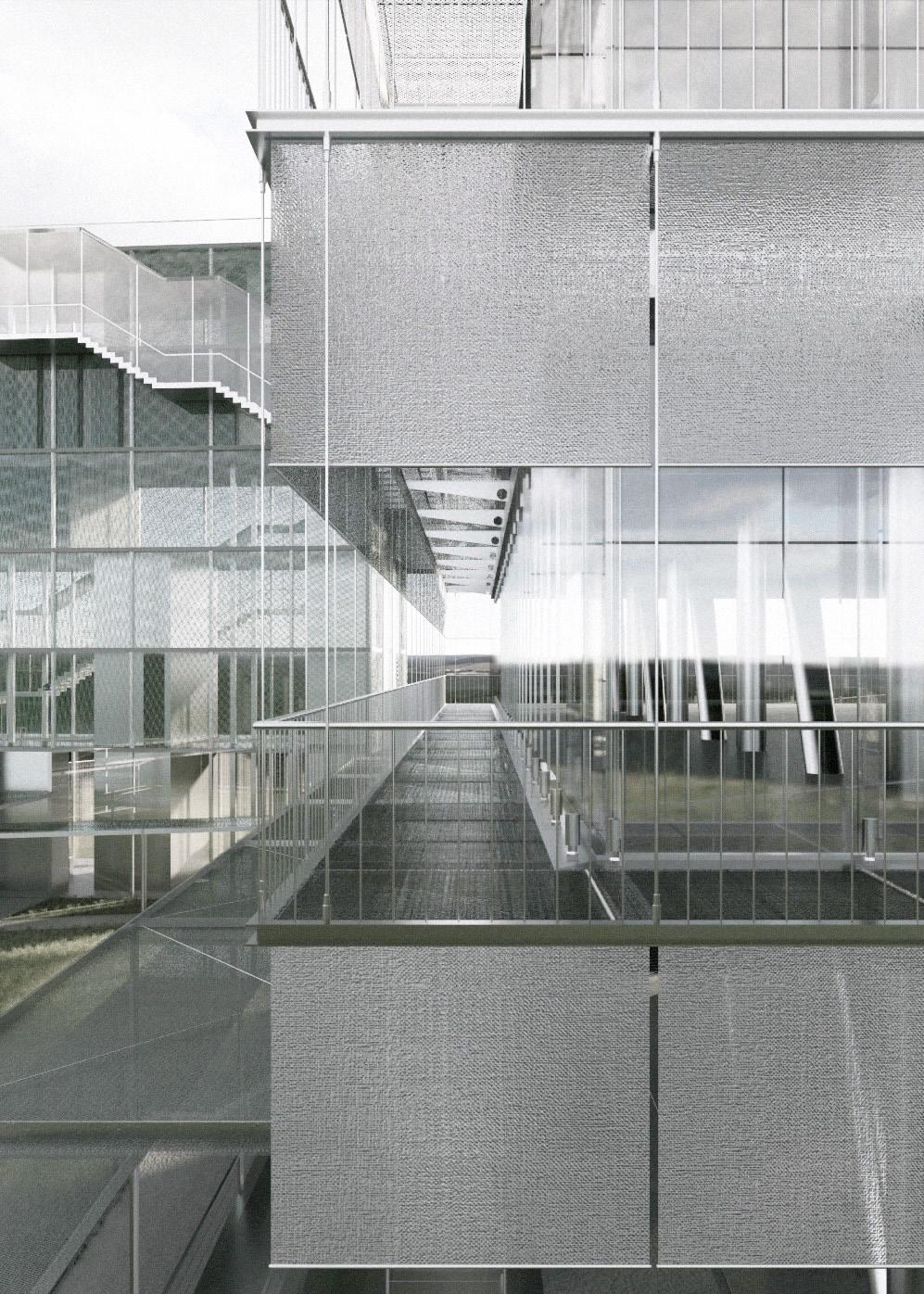

The design of this project features two façade typologies, with the public building differing from the other two. The public building’s façade consists of a glass-fin glazing skin and a lightweight balcony with shading. Its transparency and the ambiguity of enclosure created by the balcony align with the concept of openness, allowing the internal programs to connect more closely with the central alun-alun.

The two private buildings present a more concealed and understated appearance, reflecting the nature of their housing programs while highlighting the presence of the public interface of the site. The metal mesh façade ensures the security and privacy of these two buildings. Three distinctive forms of circulation space are depicted in this elevation, with circulation being a prominent design motif inspired by contemporary Dutch architecture. This gesture responds to the liveliness of the alun-alun, where the movement of occupants adds vibrancy to the imagery.

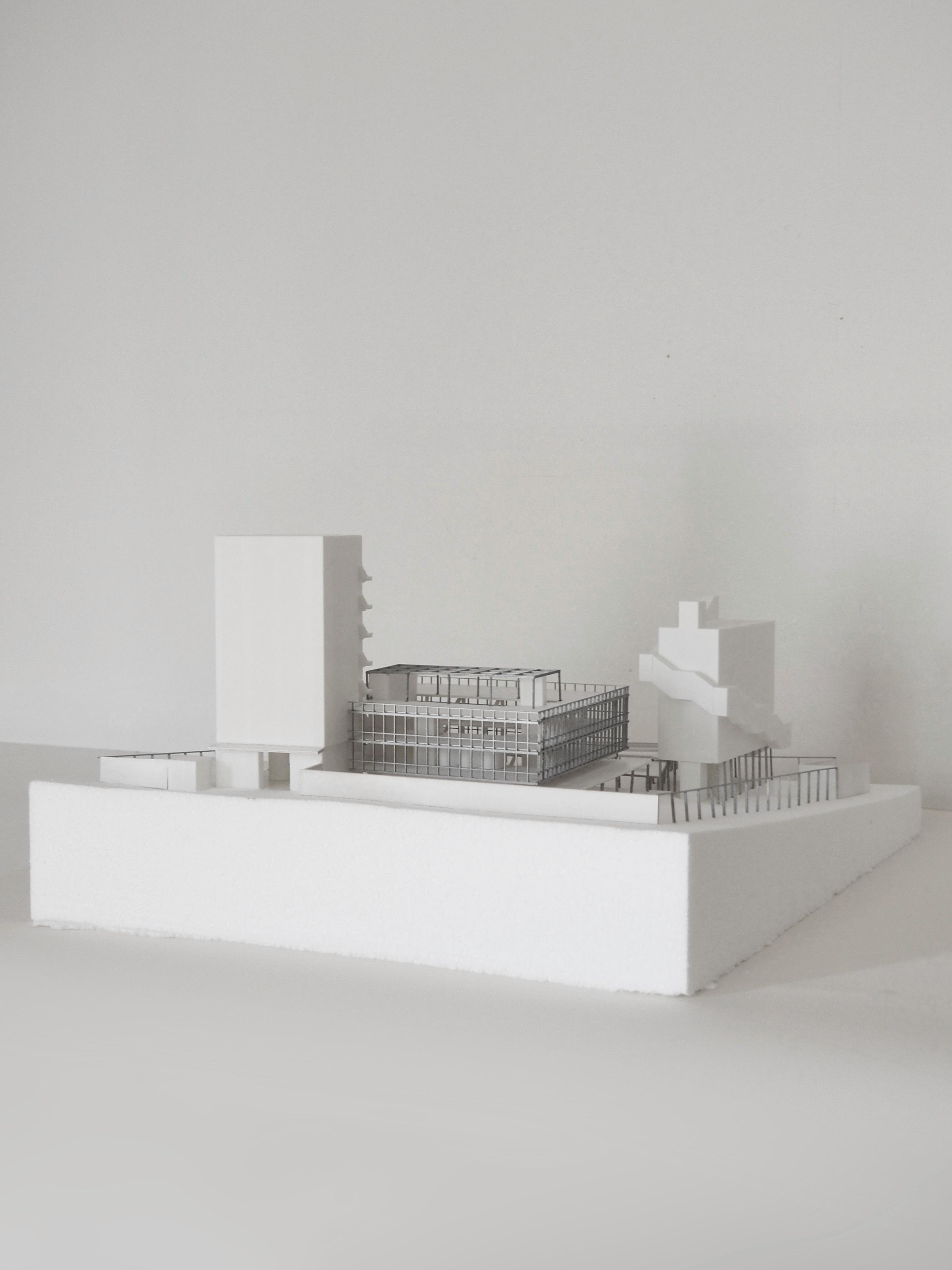

physical model southern perspective

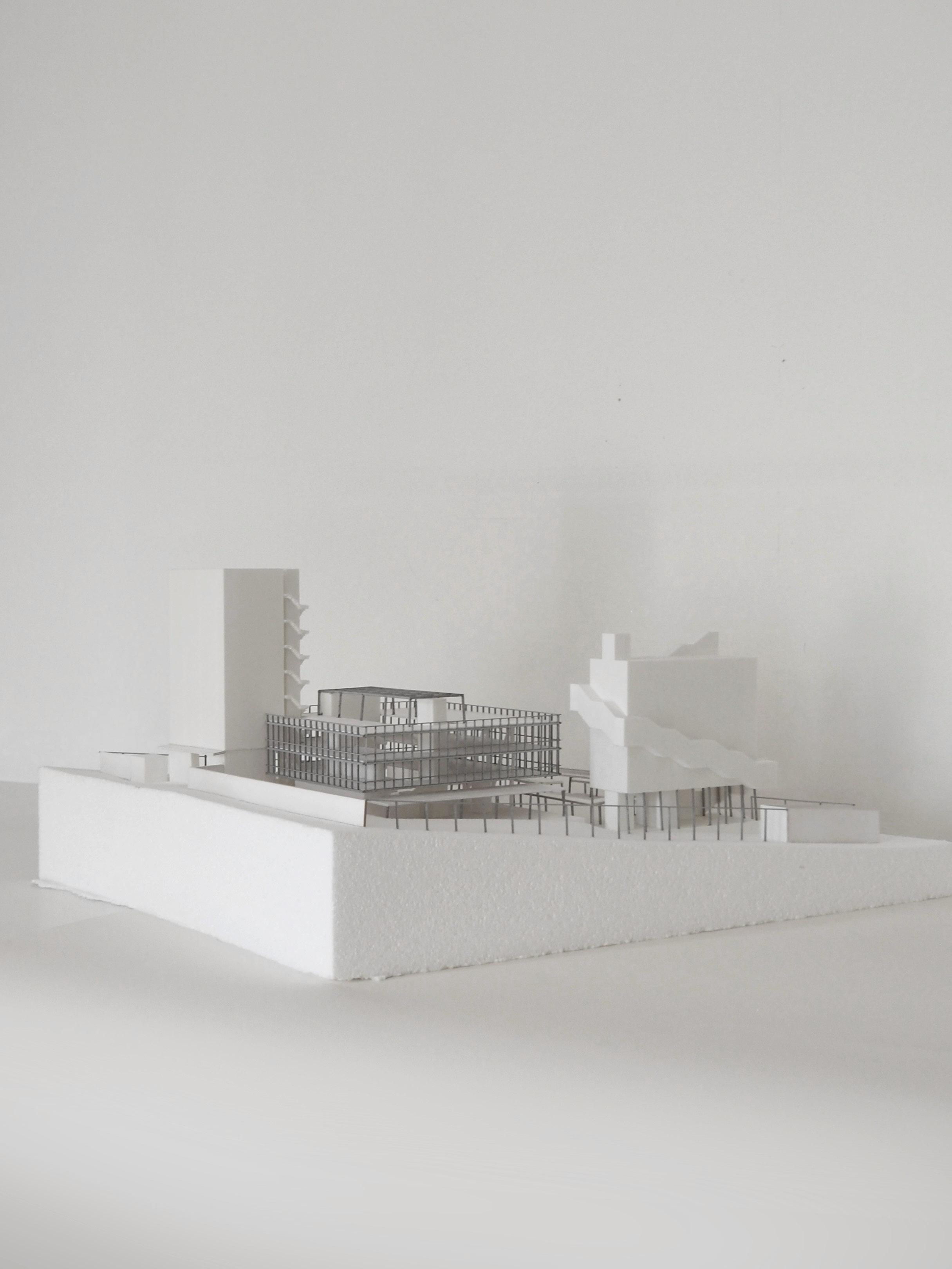

physical model northern perspective