16 10 24 28

16 10 24 28

PUBLISHER

Kari Borgen

EDITOR

Lissa Brewer

Photographer

Lukas Prinos

DESIGN DIRECTOR/LAYOUT

John D. Bruijn

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Eric Davis

Peter Korchnak

Katherine Lacaze

Rebecca Lexa

Pat Welle

ADVERTISING SALES MANAGER

Sarah Silver

ADVERTISING SALES

Heather Jenson FOLLOW US facebook.com/ourcoast instagram.com/ourcoast

EMAIL TO US editor@discoverourcoast.com

WRITE TO US P.O. Box 210 Astoria, OR 97103

VISIT US ONLINE DiscoverOurCoast.com offers all the content of Our Coast Magazine and more.

Copyright © 2025 Our Coast. All rights reserved.

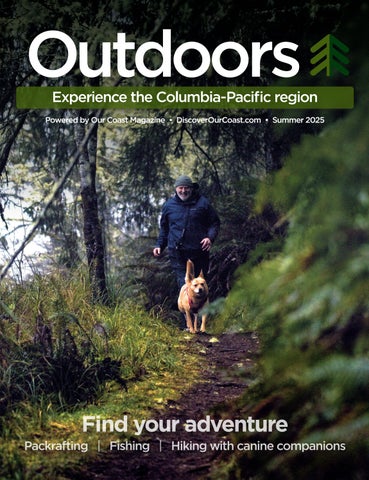

Around the Columbia-Pacific region, there’s plenty of ground to cover with the company of a canine companion.

From the Oregon Coast’s 363 miles of public shoreline to hiking trails that meander by lakes, through wispy ferns and under evergreen canopies, there’s always somewhere new to roam.

Discover some of the North Coast’s dog-friendly destinations on Page 10.

Those were the words scribbled by Rebecca Lexa onto a copy of her new book, “The Everyday Naturalist: How to Identify Plants, Animals and Fungi Wherever You Go,” at a recent signing in Seattle.

Lexa, who readers may be familiar with through her Rainy Rambles column in Coast Weekend, had framed the idea of identifying — learning the names of nature — as a means of building familiarity, not unlike getting to know the people who live next door. This concept she introduced as “phenology.”

The National Phenology Network, a group that collects data on seasonal cycles, defines the word as “the study of the timing and cyclical patterns of events in the natural world.”

In simpler terms: When do fall Chinook enter the Columbia River? When do the salmonberries ripen? How long until the first freeze?

Familiarity with nature’s patterns is essential for enjoying much of the Columbia-Pacific region’s outdoor splendor. Knowing the tide before a kayaking or rafting trip. Fishing or foraging with the seasons. Trusting experts who study when and where.

But just as this knowledge can be essential, it can also bring great joy. To watch Rebecca skip from tree to lichen on a trail is to witness contagious wonder, to get to know just a little better the places we call home.

Familiarity with nature’s patterns is essential for enjoying much of the Columbia-Pacific region’s outdoor splendor.

Check out what the Columbia-Pacific region has to offer

Eric Davis carries an inflatable raft out of the water. Portable enough to transport by backpack, rafts like this one allow for access to remote islands and forgotten estuaries.

Words & Images: Eric Davis

dventure doesn’t end at the shoreline — sometimes, that’s where it begins. Where rivers braid through alder and spruce, and the best way forward is to float. For me and my daughter, that’s where the Rapid Raft — a 3-pound inflatable raft that rolls up in my pack, then springs to life in the wild — comes in. We use it to reach what hikers can’t: secluded river islands, forgotten estuaries and gravel bars teeming with agates. On the North Coast, packrafting isn’t just a way to cross water. It’s how we cross into the unknown.

Packrafting combines hiking and rafting, with lightweight inflatable rafts that are small enough to carry in a backpack, yet tough enough to run rivers, fjords and even ocean swells. Originally developed for military crossings, the Uncharted Supply Co. Rapid Raft inflates in under a minute and holds up to 400 pounds. It’s not a luxury float. It’s a tool for exploration.

What it lacks in comfort, it makes up for in reach. When a trail is washed out, a beach disappears at high tide, or there’s a channel between you and a perfect gravel bar, packrafts make it possible. It gives one’s legs a muchneeded break and lets the core and upper body take over, an aid to travel farther, safer and smarter.

The Columbia-Pacific region is riddled with rivers, tidal sloughs, glacial creeks and estuaries. Some of the best agate-hunting spots lie beyond these waters. Other times, the best plan is just to go, wherever the current leads.

With a young one in tow, it’s not just about making it across; it’s about making it safe. Indra, my 8-year-old daughter, either rides with me or paddles solo, depending on conditions. If the river is swift, we set up a rope line and clip in, hand-pulling our way across. If it’s shallow or snaggy, we walk beside it, letting the raft float as we guide it forward. It’s not always graceful, but it gets us there.

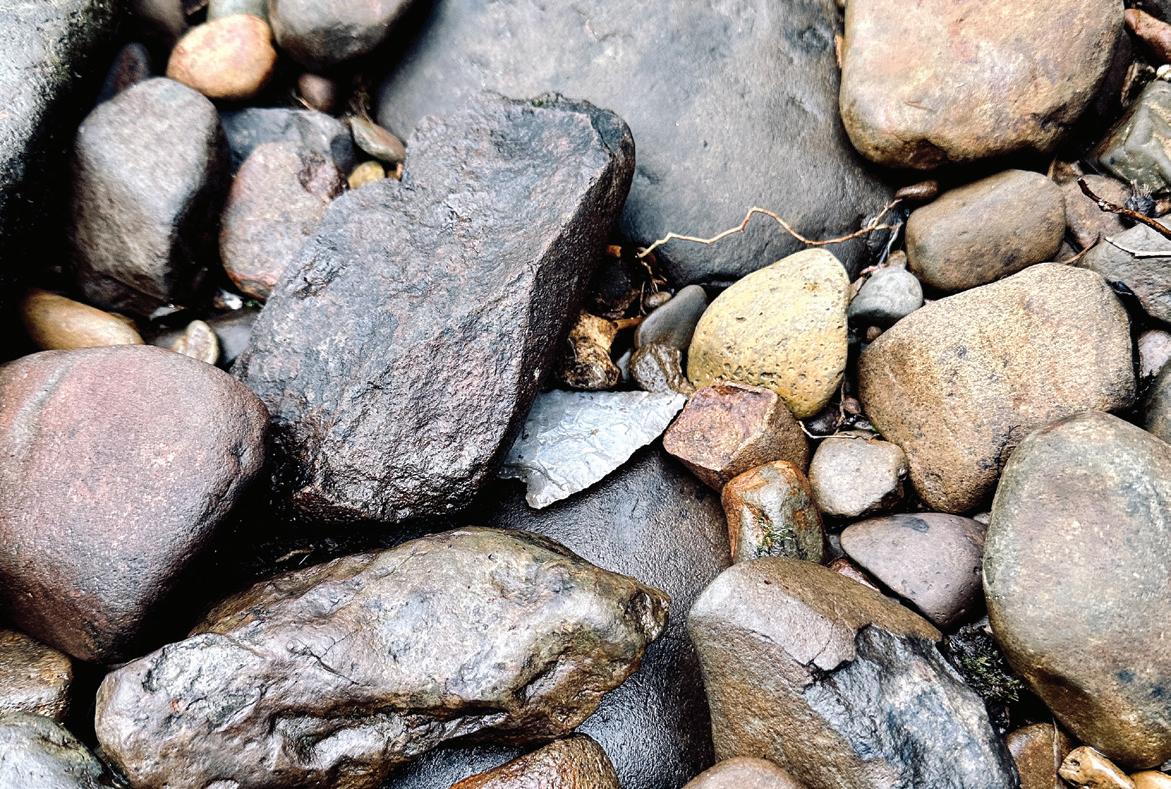

Bring a dry bag with supplies like snacks, water and tide charts and a notebook for recording finds. Arrowheads, like this one made from chalcedony, are prized finds.

On New Year’s Day, we loaded up the Jeep with an inflatable kayak and packraft. Winter rains had been flooding the rivers for weeks, and we hoped water levels would drop just enough to expose new gravel bars. But as we drove, it became clear that all our usual launch points were still underwater.

Then, we noticed a stretch of shoreline we’d never accessed before. With a kayak, it would’ve been difficult, but with the packraft, it was doable. We inflated, prepped our line and crossed, though the current swept us slightly past our intended landing point.

That’s when we saw it: a shoreline littered with glints of agate and chalcedony. We pulled the raft ashore, and right where I set it down, something caught my eye — what looked like a knapped edge, half-buried beneath a rock.

I lifted the rock and uncovered what appeared to be an arrowhead made from chalcedony. Sharp, translucent and ancient, Indra held it and whispered that she could feel the energy inside it. Later, we posted the find online, where followers supposed it could be a Gatecliff Stemmed projectile point, dating back thousands of years.

For comparison, we took it to local museums, where it matched pieces from the late-middle Archaic period. Certainly, it was the find of the day.

The next morning, that shoreline was gone, flooded again by rising waters. If we hadn’t launched when we did, with the right gear and a curious heart, we never would’ve found it.

In all, we’ve crossed rivers where the only tracks are elk and raccoon. We’ve hit gravel bars so quiet, agates can be heard clinking in our bags. Sometimes it’s just us, the river, and the call of a gull overhead. That’s the magic.

The raft becomes a bridge, not just between shores, but between worlds. It’s a reminder that wildness doesn’t always announce itself. Sometimes it just waits, tucked behind the bend of a river, shining in the gravel if you know how to look.

Gravel beds along rivers, accessible by raft, are prime locations for rockhounding. Rafting is also a great way to access remote areas for agate hunting.

• Always scout entry and exit points. Tides, currents and wind can shift fast.

• If traveling with kids, test paddles in calm water before heading out.

• Be cautious around deep estuary mud or sudden drop-offs.

• Use a rope line for strong currents. Clip your raft and pull across rather than paddling against the flow.

• Avoid surf zones unless highly experienced. Packrafts are not surf kayaks

Youngs River Estuary

Where freshwater and salt meet. Paddle among herons and driftwood giants. You’ll need to time your route with the tide, but the gravel fans near the old pilings can be goldmines for agate and fossil fragments.

Walluski River

A lesser-known Youngs River tributary with brushy banks, oxbows and a remote feel. Not long, but quiet and full of wildlife. Great for solo scouting or tacking onto a bigger estuary loop.

Lewis and Clark River

A mellow tidal river west of Astoria with calm stretches and rich wildlife. Paddle past Netul Landing and into lush backwaters. Ripe for discovery with old pilings, mossy banks and the echoes of early European explorers.

John Day River

Narrow in spots, but beautiful and remote. Occasional basalt outcrops make this feel inland and volcanic. Expect solitude and the chance to spot wildlife along the riverbanks.

Skipanon River

Short but scenic, this narrow tidal river winds through docks, marshes and quiet neighborhoods. Great for a beginner’s paddle or quick scouting mission. Sandbars upstream may yield tiny drift treasures.

Necanicum River

Perfect for beginners. Gentle flow, especially in the upper stretches. Sandbars on the outskirts of town can hold surprising pockets of quartz and jasper. Drift under bridges, past riverside homes, and into quiet sloughs where you might spot herons or otters.

Nehalem River

Winding through tide flats and forest, it offers wide channels and plenty of gravel bars that emerge at low tide. This is a prime spot for agate picking. Watch for harbor seals and bald eagles. Paddle the upper estuary for serenity, or head downstream toward Nehalem Bay.

Wheeler Slough

Protected, tide-influenced backwaters between Nehalem and Wheeler. Calm paddling with excellent birdlife and scenic gravel bars. Good for families or wildlife photography.

Miami River

Small, tight and brushy in parts, but accessible with a packraft. Drift over shoals and scout side channels. Best after the rains recede. Ends near Garibaldi with estuary access.

Kilchis River

Clear and fast-flowing with rocky shoals and prime agate bars in summer. Good access off forest roads. A favorite for those chasing jasper and the occasional fossilized wood.

Willapa Bay

Bring a tide chart and a weather window. Hop between remote spits and ghostly tidal channels. Land where the clams bubble and the agates glint. Ferry across the wind and let the fog lead. Ideal for full-day or overnight missions with proper gear.

A storybook waterway, shared with Wahkiakum County, just north of the Columbia. Flowing under covered bridges and through foggy pastures, this peaceful stretch is great for light paddling and shorecombing. Jasper and tumbled stone may turn up in the right conditions.

A moody river with prime winter gravel exposures and upper stretches that feel wilder than they are. Explore near the tide line for hidden beaches and driftwood banks.

• Packraft

• Paddle or rope line

• Life vest or other personal flotation device

• Dry bag with layers, snacks and water

• Agate bag and rock hammer

• Map and compass, or GPS

• Tide and river level charts

• Headlamp

• Wading boots or river shoes

• Child-sized raft or tandem option for youth paddlers

• Lightweight tarp, for sudden rain or a makeshift base camp

Words: Katherine Lacaze

Oregon’s North Coast entices hikers for a variety of reasons: a myriad of trails that wind through lush temperate rainforest and across grass-covered dunes, sprawling beaches hugged by rocky cliffs and quaint coastal towns, and several walkways that connect cultural and natural sights.

Another big draw? There are many hikes where you can be accompanied by your four-legged friends. In fact, this region has a reputation for being particularly dog-friendly, with easy-to-find lodging for pet owners plus water bowls and treats common in downtown Seaside, Cannon Beach and Manzanita.

And for those looking to experience the outdoors with their pets, there is no shortage of recreational options.

From the Long Beach Peninsula to Tillamook County, you can find sandy beaches, waterfront walkways, and forested trails that welcome you and your dog — or even cat, in some cases.

There are many hikes on Oregon’s North Coast where you can be accompanied by your four-legged friends. The region has a reputation for being dog-friendly.

The southwestern corner of Washington state offers nearly 30 miles of open beach that is pet-friendly. The beach itself is considered a highway, so it’s easy to drive and park on the hard-packed sand and head out for a walk.

Dogs can be off-leash on the beach, but must be on a leash no longer than 8 feet in Long Beach, an ordinance that also applies to Washington State Parks. And, of course, pick up after your pet. That applies to even the most welcoming trails and beaches.

A variety of historical and natural attractions, including the Wreck of the Peter Iredale — remains of a ship that ran ashore in 1906 — and a historic fort built near the end of the Civil War, as well as beaches, dunes, forests and hiking trails await at Fort Stevens State Park.

Dogs are welcome in the park, and there’s a large campground, too. According to Oregon State Parks, pets must be “physically restrained,” meaning on a leash no longer than 6 feet, with two exceptions: designated off-leash areas and inside your vehicle, tent or pet-friendly cabin or yurt.

Although a work in progress, the Warrenton Waterfront Trail offers a casual and easygoing walk with your dog along a relatively flat surface.

It follows an old railroad spur to Point Adams, with a few sections crossing city streets. Dogs must be kept on a leash along this trail, but they can run around and play at the Warrenton Dog Park, located along the trail at Carruthers Memorial Park.

Between Warrenton and Gearhart, the drivable 10-mile Sunset Beach is easily accessible, but dog owners should keep an eye out for vehicles. Del Rey Beach State Recreation Site, on the southern end of the stretch, is also considered pet-friendly. The grassy dunes and soft sand are suitable for soft paws, but dogs should remain on a leash.

With the dunes of Gearhart to the north and majestic Tillamook Head to the south, Seaside is a beautiful spot for a walk or a jog. Dogs are welcome off-leash, but owners must keep an eye out and assume responsibility for their behavior. Keep in mind, overnight camping is not permitted within or near state parks, nor on beaches within most major city limits.

However, this is the perfect spot to catch a sunset or take an evening stroll. And if you want a non-sandy option for your dog or cat, consider the Seaside Promenade. This 1.5-mile boardwalk starts at 12th Avenue and concludes at Avenue U, lined with lamps along the way.

For a pet-friendly hike that’s a little further inland, visit Soapstone Lake Trail, located on Oregon Route 53, about 5 miles from U.S. Highway 26. Situated west of Oregon Coast Range, the roughly 2-mile trail to the lake weaves its way through towering trees, moss, ferns and other native plants.

From there, you and your pet can enjoy a roughly 40-minute walk around the lake, known for its reflections of the surrounding vegetation, as well as optimal wildlife viewing. Pets must be kept on a leash and there is no camping allowed in the park.

With a reputation for being dog-friendly, Cannon Beach is a destination to enjoy a walk with your dog year-round, either downtown or on the beach, although they must be kept on a leash or under voice control. On the northern end of the beach, you might spot herds of elk in their favored spot near Ecola Creek.

Cannon Beach’s famous Haystack Rock is another big attraction. These can be fun sights for locals and visitors, but make sure your dog doesn’t interact with the elk. Additionally, Haystack Rock is protected as one of Oregon’s seven marine gardens and it is a part of the Oregon Islands National Wildlife Refuge.

The tide pools at Haystack Rock are sensitive habitats, so it’s best to keep dogs close to avoid harming marine wildlife and birds.

Located near Arch Cape, the Hug Point State Recreation Site offers easy beach access and a forested picnic area, making it an ideal spot for those looking for a simple way to savor scenic coastal beauty with their pet.

There’s a sandy beach, seasonal waterfall, and caves that have been naturally carved over time in the sandstone cliffs. According to Oregon State Parks regulations, you don’t have to leash your dog on the ocean shore, but should when you’re walking on the trails.

At 2,484 acres, Oswald West State Park contains miles of hiking trails, including a 13-mile stretch of the beloved Oregon Coast Trail. There are about 4 miles of coastline in the park, which extends from Arch Cape down to Manzanita, along with old-growth forest and breathtaking views from tall summits.

Along all trails, you’re expected to keep your dog on a leash and clean up after them. Some popular spots for dog walkers include the Cape Falcon Trail and Short Sand Beach, which is accessible by a short, shaded path down from the parking area off U.S. Highway 101. Be cautious with your pup when visiting the tide pools north and south of Short Sands.

Neah-Kah-Nie Beach and Nehalem Bay State Park

Manzanita is a quaint coastal village that, similar to Cannon Beach, has a welcoming atmosphere for pet owners. It also is nestled next to 7 miles of sandy beach, from Neah-Kah-Nie Mountain on the north end to Nehalem Bay.

In the vast open area on the beach, you can comfortably let your dog run or walk off leash. Inside the park itself, there’s a 1.8-mile forested path where you can catch beautiful views of the bay, but dogs must be kept on a leash.

Additionally, there’s a Western Snowy Plover Management Area on Nehalem Spit, which means during nesting season — from March 15 to Sept. 15 — no dogs are allowed, even leashed.

For a longer but moderately easy hike with your pet, visit Cape Lookout State Park in Tillamook. There’s an approximately 5.2-miles hike along the Cape Lookout Trail, where hikers are given views of the Pacific Ocean and its shoreline through forests of Sitka spruce and hemlock when venturing to the tip of Cape Lookout.

Dogs are required to be on a leash, even on the beach. Along with day use, Cape Lookout is also a popular camping destination, with more than 200 sites for tents, trailers and RVs, and pets are welcome inside the camping area.

Dogs can roam free on most ocean beaches, but watch for exceptions, such as around the Haystack Rock Marine Garden.

A photo essay by Pat Welle

The Lower Columbia River is dynamic, complex, sometimes very dangerous, but always beautiful. Surrounded by cliffs, forests and quiet backwaters, visitors can see numerous birds and animals, and enjoy fishing, hiking and boating through this expanse where the river meets the ocean. Communities hug the river and working fisheries support local economies.

I tend to focus my camera on small, quiet spaces — along trails in Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, sloughs off the John Day river, and numerous beaches to watch feeding shorebirds.

Summer brings white pelicans and other seasonal birds, while the common loon and many waterfowl return in winter. Year-round, we hear Pacific wrens deep in the forests, and can usually find belted kingfishers perched on snags above the water. Occasionally whales and other marine mammals wash up and are stranded on the beach, reminding us of life’s many cycles.

Here along the Columbia River, you can always find fascinating beauty, and enjoy the outdoors in all its forms.

A spotted sandpiper feeds on pilings, often seen along riverbanks.

The Netul River Trail follows the Lewis and Clark River from a historic canoe landing to Fort Clatsop, site of the famed explorers’ winter encampment.

A belted kingfisher, common to see year-round, perches above the water.

A common loon in Baker Bay, located just inside the mouth of the Columbia River.

Reflections along the Wallicut River, near Ilwaco.

Beached whale

A whale becomes part of the sand at Long Beach.

Summer brings white pelicans to the Columbia River and Youngs Bay.

A wave breaks over Waikiki Beach. The cove, located within Cape Disappointment State Park, is popular for viewing high surf during annual king tides.

“The Everyday Naturalist: How to Identify Plants, Animals and Fungi Wherever You Go”

Words: Rebecca Lexa • Illustrations: Ricardo Macia Lalinde

One of my best moments ever was when I got to add a bird to my life list and impress a guy at the same time.

Okay, so the guy was my longtime partner, who’s impressed by everything I do, and he once told me, “I need a life list of animals I’ve looked up on Google Image Search because you told me you saw one in the wild.” But I really did outdo myself this time. We were out on a chilly March day near Echo, Oregon, tracing the ruts left by wagons on the Oregon Trail. Small flushes of greenery were just starting to emerge beneath miles of twisted, pungent sagebrush scrub, and we stopped every so often to watch large black darkling beetles trundle across our path. They — and one pile of dried-up coyote scat — looked to be our only wildlife sightings for the day.

That was, until a flash of feathers snapped my attention to the northwest. Forty yards off and flying away fast was a towhee-sized bird; even at that distance, I could see its grayish-brown back and the white belly flecked with an abundance of brown spots. But it was the bill that I noticed the most: slender and longer than that of a thrush, with a slight curve. It was not so large as the one on the brown thrasher I had seen near my parents’ place in Missouri the year before, and it lacked that bird’s russet tones. The overall giss, though, indicated “thrasher.”

The bird quickly winged its way low over the scrub before it disappeared into the sea of sage. All told, I had it in view for about three seconds. But it was enough to trigger memories of pictures I’d seen while paging through countless field guides and articles. In this area, at this time of year, there was only one bird it could be.

“Sage thrasher!” I yelled to my partner, pointing where it had gone. “My first one!”

He was momentarily incredulous. “You’re kidding. You’ve never seen one in person before?”

“I am absolutely certain of it.” I giddily recited the traits that pointed toward my identification.

He shook his head and grinned. After more than a decade together, he was used to me getting distracted every five feet so I could pin an identification on some animal, plant, or fungus I’d seen. But this was proof I’d leveled up: I’d nailed down my unidentified flying object with mere seconds of observation time, at a distance, and with no prior in-person experience with this species.

Book illustrations

“The Everyday Naturalist: How to Identify Plants, Animals and Fungi Wherever You Go” is illustrated by artist Ricardo Macia Lalinde.

I did, of course, verify my identification once we got back to the car, pulling out field guides and checking websites of the National Audubon Society, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and other well-respected sources. I checked iNaturalist to see if anyone else had seen sage thrashers here this early in the year, since they are in the Pacific Northwest only for the breeding season. I looked up similar species that might be found in this location at this time, and none were as close a match with the bird I saw. Everything still pointed to my encounter as seeing one of the earliest sage thrashers to return to Oregon for the breeding season. I’m always open to the possibility that I am wrong no matter how solid my research is, but for now, I’m certain enough that I added the sage thrasher to my life list, thanks to that encounter.

Being able to identify a bird at fifty paces may seem like a small accomplishment, but for me it was a major milestone on a dedicated path that I’ve been exploring for the better part of two decades. I’ve always been a giant

nature nerd ever since I was big enough to toddle around the yard. But when I left behind the Ozark oak-hickory forests in my twenties and landed in the coniferous Pacific Northwest, I realized I was in unfamiliar territory.

I countered my disorientation by learning the unknown species around me. At first, it was just a few each time I went hiking, but as the years went on, my quest intensified. I purchased stacks of field guides and scoured websites, and when I was introduced to iNaturalist as part of a citizen science project, I added electronic apps to my toolkit.

And now I’m handing that toolkit over to you. Whether you are a seasoned naturalist or just starting to learn the species around you, I want you to feel more confident in your ability to positively identify a new-to-you species. You aren’t required to have a degree in the natural sciences to do this, either. “The Everyday Naturalist” is full of techniques and tools that anyone can use, both to learn about your neighborhood nature and when traveling to exciting new ecosystems.

Whether you are a seasoned naturalist or just starting to learn the species around you, I want you to feel more confident in your ability to positively identify a new-to-you species.

Editor’s note

This is an excerpt from the book “The Everyday Naturalist: How to Identify Plants, Animals, and Fungi Wherever You Go” by Rebecca Lexa, published June 17, 2025, and reprinted with permission by Ten Speed Press, a division of Penguin Random House.

“The Everyday Naturalist” is available online at Penguin Random House and from local independent booksellers.

Rebecca Lexa, now based in Portland, is a frequent contributor to Coast Weekend and wrote the book while living on the Long Beach Peninsula.

he Columbia-Pacific region is a fishing paradise.

TWhile charters handle larger groups on bigger boats, licensed by the U.S. Coast Guard with a skipper and crew, while guides usually work alone, providing hands-on fishing experiences with smaller craft.

Ilwaco, on the Washington side of the Columbia River, is a hub for ocean fishing charters, while Astoria boasts an array of river guides.

Steve Sohlstrom, owner of Ilwaco-based Sea Breeze Charters, is one of several purveyors of ocean fishing trips. Each of the company’s boats is able to carry 7 to 14 passengers and is equipped with electric reels. Sohlstrom himself captains the vessel Salty Dog.

Ocean fishing runs roughly from April to September, with varying fisheries. Bottom fishing begins in early April, with lingcod, rockcod and other bottom dwellers. Halibut season kicks off May 1. In a just-wrapped halibut season, Sohlstrom’s charter ran 79 trips for some 560 guests, with the record specimen weighing 63 pounds.

“Halibut was literally off-the-charts good,” Sohlstrom said.

But the region is perhaps most famed for salmon, a major ocean fishery between June and September.

“We’ve been just scoring beautiful limits of nice Chinook and Coho salmon on nearly every trip that we’ve gone to sea,” Sohlstrom said as of July, with trips going out some 7 or 8 miles off the coast. “Some of our boats are coming back to port with 30 salmon on board in less than one hour of fishing. The fish are just stacked. It’s been an incredible start.”

The company also participates in the Buoy 10 salmon fishing season on the Columbia River, which is expected to begin Aug. 1.

“But predominantly we’re ocean fishermen, that’s where the fish are,” Sohlstrom said.

For albacore tuna, starting Aug. 1, charters travel 50 miles offshore to catch — with live bait — as many fish as they can carry.

The charters of Ilwaco work together, according to Sohlstrom, even crossreferring customers if they’re full. “We’re a community,” he said.

In Astoria, river fishing guides vie for business.

Jeff Keightley has been running Astoria Fishing Charters and Guide Service out of his home for the past 17 years. With Buoy Beer, his nearly 30-foot sled boat, he can accommodate up to six guests.

Ocean fishing runs roughly from April to September, with varying fisheries. Bottom fishing begins in early April, with lingcod, rockcod and other bottom dwellers. Halibut season kicks off May 1.

Coffenbury Lake is stocked with rainbow trout during the spring and summer months.

A

Spring Chinook runs begin In March. While Keightley focuses on bait fishing salmon and bottomfish, his boat can also handle the ocean, where he targets crab.

According to Keightley, his is one of the few local charters that can issue one-day fishing licenses right on the boat, and he also provides customers with higher-end fish processing, including cutting, vacuum seal packaging, and ice packing containers.

“Everything you need to carry fish on an airplane,” he said. Like many guide services, while Keightley can provide customers with the basics, including climate-specific rain gear, he advises consulting the exhaustive list of “things to bring” provided on his company’s website. He also calls customers the day before their trip to check on their preparedness.

For the past decade, Curtis Bunney has owned and operated First Pass Outfitters, another single-boat operation based in Astoria. Up to six passengers can go on half- or full-day fishing trips on his 28-foot aluminum boat, Blood Sport.

In addition to salmon and sturgeon, he also targets steelhead trout. Ocean fishing, for both salmon and crab, is weather-dependent. Bunney processes keepers on the boat and then, after inspection, dockside at Astoria’s West Mooring Basin.

Because of his job as a tugboat captain, Bunney’s schedule is flexible.

“If the fish is not good, we can reschedule or do something else,” he said. Still, he added, “I do an awful lot of guide fishing.”

Safety is the first topic Bunney covers with customers, including the need to bring weather-appropriate gear and dress in layers. Sohlstrom, too, underscored the point. “Out on the ocean, we’re all safety-first,” he said.

Like Keightley, Bunney does not guarantee a catch.

“I don’t sell fish, I sell an experience,” he said. “I believe I’m a good fisherman, and I’m going to work my butt off to make sure that you have an opportunity at a fish. It would be unheard of to go out and not catch one. But you’re still fishing a wild animal, so there are no guarantees.”

The fishing business is a seasonal one.

“Seasonality is all part of the game,” Sohlstrom said “Here on the ocean, the best weather months are May to September, that’s the time you’re going to want to be fishing.”

Bunney doesn’t mind the seasons. “It’s nice to take a break sometimes,” he said.

Charters are equipped to carry a cross section of guests,

from families with children to experienced fishermen, corporate teams to novice anglers.

Sohlstrom particularly enjoys introducing ocean fishing to newbies. “They say, ‘my God, why haven’t I done this earlier in my lifetime?’,” he said. “It’s a pretty exciting trip.”

Similarly, Keightley’s setup is geared toward tourists.

“I prefer people that think they don’t know what they’re doing, because they tend to listen well,” he said. “A lot of the people that call me, they just know they’re going to a fishing town, and they want to go fishing.”

While he welcomes a diverse group, Bunney strives to attract corporate clientele.

“I think it’s a great atmosphere for employees to go out there with their managers or just be in a relaxed environment to talk about business,” he said. “A lot of ideas have been created on my boat.”

As for how to pick the right charter or guide, most of which can be booked online or by phone, providers tend to agree on several points.

Choosing a local company is key, because skippers or guides can offer experience.

“I’ve been fishing these fish my whole life,” Bunney said. “I know their patterns and that allows me to be one step ahead of them.”

The fishermen have seen the business evolve over the years. One constant change is limits, set annually by the Pacific Fisheries Management Council and state fish and wildlife departments. According to Sohlstrom, this year’s salmon quotas increased year-to-year by 15% to 25%, reflecting forecasts of larger than usual runs. Once popular, sturgeon stocks on the river have been depleted and are only available for catch-andrelease fishing.

There are also more sea lions stalking the stocks. According to Keightley, the industry has seen an influx of guides, many based out of upriver locations — and marketing has shifted from word-of-mouth to online.

But all in all, Bunney said, “the business basically stays the same: we’re still taking people out and creating memories and enjoying the outdoors.”

Sea Breeze Charters, Ilwaco, Wash. www.washingtoncoastfishing.com 360-642-2300 or fishon@seabreezecharters.net

Pacific Salmon Charters, Ilwaco, Wash. www.pacificsalmoncharters.com 360-642-3466 or pacificsalmoncharters@gmail.com

First Pass Outfitters, Astoria www.firstpassoutfitters.com 503-741-0075 or curtis@firstpassoutfitters.com

Scott’s Outdoor Adventures, Astoria www.scottsoutdooradventures.com 503-860-7211 or scottsoutdooradventures1969@gmail.com

Astoria Fishing www.astoriafishing.com 503-436-2845 or jeff@astoriafishing.com

For trailhead mornings and firepit nights, Xtratuf has a pair for every path.

From dockside runs to campsite strolls, boots built for your whole rugged crew.