The Reign Fails

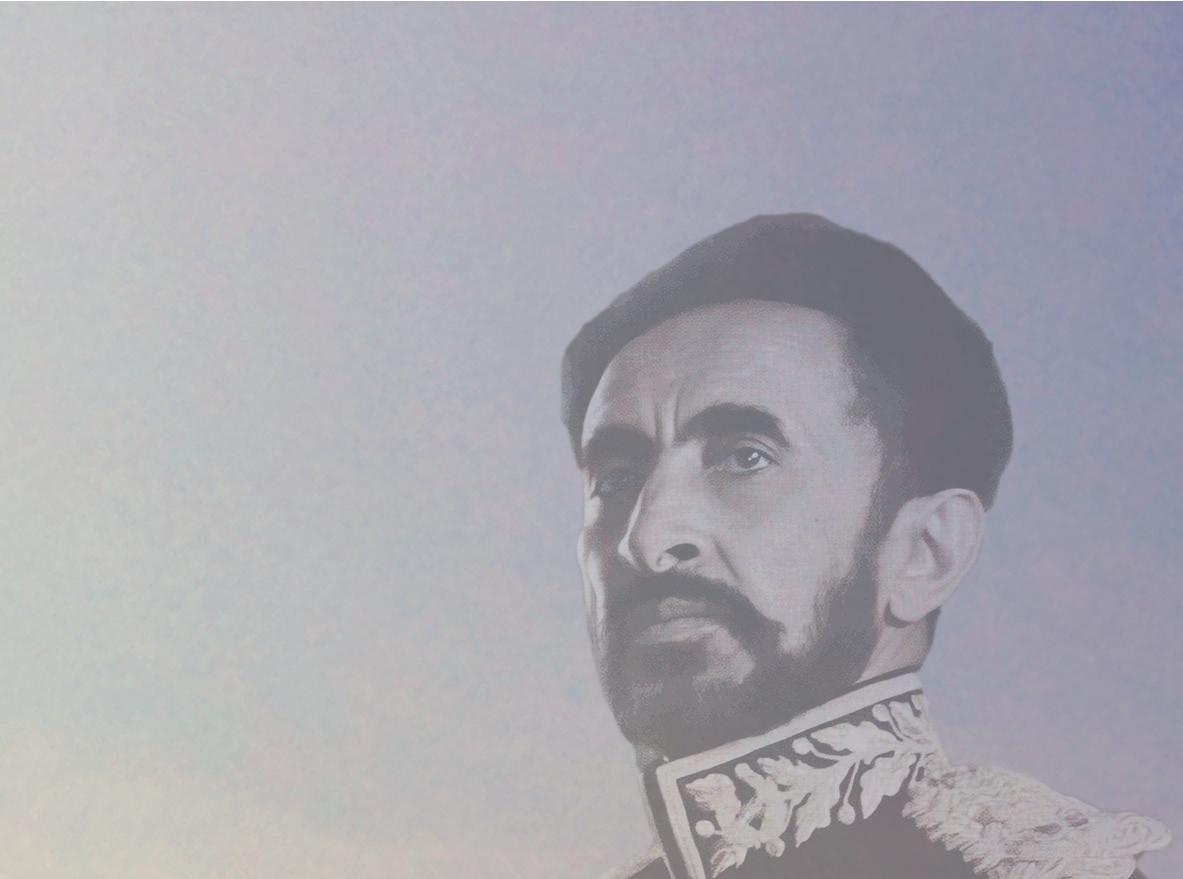

A novel by Keith Ashfield

The Reign Fails

A novel by

Keith Ashfield

This presentation edition printed in a run of 100 numbered copies. This copy is number

The Reign Fails

A novel by

Keith Ashfield

Author’s numbered edition

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to persons living or dead is entirely coincidental.

Copyright ©2024 by Keith Ashfield

All rights reserved

Cover and text designed by Bruce Hanson, EGADS

Printed 2024 by the author

Presentation edition for private circulation only.

For Bendy

Chapter 2

Camp in Weldiya,Wollo Province, Ethiopian Highlands, 8,000 ft Altitude, August 1973

Embassy, Addis Ababa, September 1973

Chapter 3 Buna Beit, Addis Ababa

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Palace, Addis Ababa

Embassy, Addis Ababa

Chapter 6 British Embassy, Addis Ababa, October 26, 1973

Chapter 7 Buna Beit, Addis Ababa, October 27, 1973

Chapter 8 Bole Airport, Addis Ababa, October 29, 1973

Intermezzo Camp in Weldiya,Wollo Province, Ethiopian Highlands, last week of October, 1973

Chapter 10

November 1, 1973

Chapter 11 Embassy of the USSR, Addis Ababa, November 12, 1973

Chapter 12 Imperial Palace, Addis Ababa, November 12, 1973

Chapter 13 Armenian General Store, Addis Ababa, November 15, 1973

Chapter 14 Bole Airport, November 20, 1973

Chapter 15

Ababa and Wollo Province December 18, 1973

WORLD LOCATION MAP 1973

NORTH ATLANTIC OCEAN

London Bern Moscow USSR

Sicily MEDITERRANEAN SEA Beirut

Suez

Canal

EGYPT SAUDI ARABIA

Sahara Desert

SUDAN

NIGERIA

SOUTH ATLANTIC OCEAN

KENYA

RED SEA

Addis

Ababa

INDIAN OCEAN ETHIOPIA

SOMALIA

Overture

ETHIOPIAN HIGHLANDS, CAMP WEST OF WELDYA WOLLO PROVINCE, 8,000 FT ALTITUDE

AUGUST 1973

DAWN AND A ZEPHYR of air sighed over the black earth. He turned onto his back slowly so that the warm air trapped between him and his gabi would not escape. It never worked. Cold mountain air surged round his body. His sleep broken he slowly unfolded from his foetal position, stood up and stretched his cramped limbs. He shook the gabi and wrapping it around his shoulders shuffled toward his sleeping wife.

The sun easing over the ridge of the horizon sent dawn light slanting across the plain at Felaka’s back. It added to the chill rather than bring warmth. When it climbed higher in the sky it would give a hard, violet heat, not the soft moist warmth that it gave to the lowlands. He was aware of it rising but didn’t turn to greet it. He bent over his wife.

He looked at her creased face in the early blue light and thoughts drifted through his mind like shadows that left no mark on his proud features. The harshness of the world in

which he lived had turned his face into a wrinkled mask. Like leather. His body had known exhaustion and his mind had known grief and the mask was too old and too set to crack now. Except once. A week ago when he had wept at the death of his second son. He had loved him as a first son after the first, Gerima, had left the land to go to school in Addis Ababa. That was thirty years ago and they had no news of him for the last twenty. And now this best loved second son had died and the old man had cried. But never before. At the deaths of three others of his grown children, and seventeen of his children’s children the mask had remained set – grave, dignified. Felaka gently placed his hand on the shoulder of his wife, Almaz. “Thirty years,” he thought, “and for fourteen of those God cherished us. We had rains twice a year – not too much and not too little. With hard work and a good family to help, a man could get two crops of t’eff harvested a year. That was enough to pay the landlord and to feed the family. But that hard work needed a full belly, and a full belly is only got with hard work. Perhaps there is no road back to the old ways now. We have not had two good rains for six years. Perhaps God has forgotten us.”

Felaka and his family had only eaten one meal a day for the last year, and that meal had become smaller and smaller as they had tried to stretch the dwindling supply of grain further and further. One day more, one day more. It had finally run out a week ago and now they lived on what they could beg from their new neighbours. His skin hung in grey folds under his arms and buttocks like drapes of cloth belonging to some ghastly garment. Almaz stirred and Felaka squeezed her shoulder.

“Yes, when there were rains,” his mind wandered on, “yes, when there were rains. Then the land on the slope was

covered in stiff grass and we had cattle and people thought us rich. We always had children to look after them too.” But not now. The last of the cattle had died months ago. And now his great grandchildren were dying one by one. Almaz stirred again, then started out of her sleep. She lay still and looked up at Felaka, unseeing against the sky as he looked down at her.

“It is good to sleep, one forgets the hunger,’ he said.

“Ayah, but it soon comes back with greater pain.” She murmured.

Slowly she raised herself up to a sitting position, drew her knees up to her chin and clasped her arms around them. She shivered and reached behind her back with one hand. She grasped the edge of her gabi and with three twists of her wrist, swirled it about herself. She rocked back and forth on her heels. Somehow it seemed to ease the pain in her stomach and to squeeze a little numbness from her cold legs and arms.

“How is your strength now?” he asked. Yesterday he had wondered if Almaz would be able to make the walk to get here. She had stumbled on after noon neither seeing nor hearing, blindly following the slow moving file of people.

“I am cold and the hunger pain is bad. Can you find some food from our neighbours?”

“I will try, but there are so many other hungry people here. They would not have come if they had food. If there was grain here it is likely gone now, they have been here a while. What may have been a little grain for a few people will be almost nothing among so many.”

Almaz still rocked slowly to and fro. “If I do not eat today

I will not live another night. I am weak and frozen. I am worn out with sadness.”

“I will see what I can find.” He turned toward the sun with despair.

For the first time he could see just how many other people had come to this place. More people than he had ever seen. They spread in front of him, between him and the orange disc of sun. They were beginning to wake, each making the same movements. Slowly unfolding to stand, stretching their backs, then shaking their gabis and with a twist send them snaking around their shoulders – with a final shake to adjust the folds to their bodies. As he gazed at them silhouetted against the sun, they looked like a flock of huge birds settling their wings after landing.

He slipped back into his thoughts. There must be more than six hundred here already. For there to be so many some must have travelled great journeys, and there will be more yet. They have all come for the same reason as us. That is bad, it means there is no food between their villages and here. He felt his burden as head of the family dragging down on his bony shoulders, as though his threadbare gabi, woven by Almaz years ago, had his entire family strung around the hem. His despair deepened.

“They have all left their land, their homes, their possessions because they have heard that there is food here.Yet there cannot be much. How foolish that what must have been little enough for the fifty or so people of this village should attract so many already.”

He thought of the few sacks of grain that they had somehow spun out for the last year.

“This village of fifty may have held out for a while lon-

ger by itself, but with the hundreds here they are sure to starve quickly – together.” He flinched. “And yet we have come here, just as the others, to add to the distress of these villagers.”

He thought of Almaz and how weak she was, he guessed that there must be many others in her condition and he wondered how many of them would die during the cold nights, before the diseases and illnesses of starvation killed them. The night cold would not be so bad if they could sleep inside. But how could they? In normal times the tukuls in this village would be packed tightly with people so that their shared body warmth would keep them from the cold nights. But there would be no room to shelter this huge army of refugees. No, they would have to sleep in the open. They would have to forget their fear of the marauding hyenas who had been driven to desperate hunting and killing by their own empty bellies. Their food supply had become scarce as the smaller animals died out at the beginning of the famine.

And then Felaka remembered the fever; he had often heard that it came at times like this, with famine and drought. Not that he had ever seen it. Very few people were alive who had. What Felaka did not know was that their very crowding together, with some people already suffering enteric illness and with no sanitation or water, was already breeding deadly germs. But he had heard of the agony of the stomach cramps, of the desperate weakness caused by the diarrhoea and vomiting and he had heard of the way that people died within six hours of becoming sick. He thought of those things now, and he remembered Almaz’s pains. Pray God she had not got the fever. But no, she had been complaining of the pains for four days now, and hadn’t he had the same pains himself? They would be dead by now if it was the fever. It must just be hunger.

Felaka and Almaz had lain down the previous night at the edge of the gathered refugees, between them and a low ridge of earth that ran from north to south. Felaka climbed onto the ridge now and looked out over the starving people. The sun had turned from orange to yellow and was climbing higher. He felt its heat begin to prick his face. He fell into thought again and remembered the times when he had been filled with joy by that same touch from the sun, but that was always after good rain when they were in the field tending the young growth, or later when they were harvesting. He wondered how many years that same cycle of sow, tend, reap had gone on without a break. Certainly for his lifetime, until a year ago, if one discounted the years when the second rains had failed. That sometimes happened. It was the will of God. Things were difficult then, but with economy and prudence they could survive, and the big rains would always follow and the second, small rains, would return the next year. Until six years ago. Since then there had been no small rains and less and less of the big rains in each following year. For a whole year now there had been no rain at all.

His forefathers had farmed the same small piece of land for as long as his history remembered. In all the stories and songs that he knew it was always one of his father’s fathers who were named as the tenants. The land had been good to them. It had provided food for each generation of strong children in return for the hard work and care with which they tended it so that they, in turn, might raise the next generation of caretakers. The land had watched over the family for a hundred years, maybe more, giving life to generation after generation of the same family. But perhaps that long train was being broken. Perhaps there would now be a whole generation missing. There surely would be unless a miracle occurred. Without food they were all certain to die, and

there was no food. Perhaps the family would never recover. It would have to rely for survival on those of its children who had married into other families, but there was little hope of their being in any better situation than those he brooded over from the ridge. There was Gerima in Addis Ababa, if he was still there, and if he wasn’t dead, but who was there to tell him of their situation, and what, in any case, would he care who had run away from his responsibilities all those years ago?

They had left their land five days ago and arrived here last night. The journey was not a great distance, but it had been very hard for them, weakened by hunger. They had crossed two ridges and two deep gorges and their path had never been level. All the time they had been either dragging themselves up or desperately digging their heels into the loose rock to prevent themselves from plunging down. They knew the journey would be hard from the few times they had journeyed that way to get to the big road, and because they remembered the track and felt their own weakness they had set out empty handed. They took nothing except the now tattered clothes that they wore. Clothes that had once been kept for wearing at festivals. Their few other possessions were locked in wooden crates in the huts on their land. There was no risk in that because there was no-one left to steal anything and, besides, they had all felt, when they left, that to be forced away from that small piece of land was a final act, that they would never see it again. It seemed right to abandon all of their small wealth in that one place.

For the seven days before they finally abandoned the land they had eaten almost nothing. They had been eking out the last baking of grey injera made from the crumbs and husks left in the bottom of the t’eff sack. Every day they had taken smaller pieces each until, for the final three days, the tiny

squares had been bone hard and they had kept them in their mouths and sucked at them for as long as they could before the bread finally softened and dissolved and they had to swallow. Some of the young parents had eaten nothing, saving their tiny ration to feed their children when everything was gone. And then the husband of one of Felaka’s granddaughters had heard that there was some grain here, in the east, on the path that ran eventually to Weldiya. He had heard the news from a family travelling through Felaka’s land who were on the way here for that reason. Felaka and the village had clutched at the report. It seemed their only hope of avoiding death.

There had been a family council to discuss leaving their land. Even in the presence of hunger and death the ancient customs were to be followed. The talk had flowed to and fro, rolling in waves across the patch of ground that was to them courthouse, council chamber and village hall. An outsider, an observer, could not have believed that this family were debating their own chances of living or dying – not in five, ten, twenty years’ time, but next week – or the week after. They were completely impassive.

Some had argued that the rains might still come and, if they did, and none of them were there, another sowing season would be lost. But others pointed out the truth; that they had no grain for sowing, they had eaten the grain put aside for seed. So rain or not, it wouldn’t help them now. A few of the younger men had argued that if they left the land untended, some of the landless people who roamed the mountains might settle on the land and take it for their own. Others asked how that could be when the travellers they had spoken with said that everyone was leaving because there was no food and they themselves could grow no more on their own land. “If we who know the land cannot grow anything

here, how can any outsiders?” The other fact, which was in all their minds but which no one openly voiced, was that none of them could stay on the land to wait for rain, or to guard against squatters, without food. And they had no food. And then someone asked what if the word of grain on the patch of land to the east was not true? What then? There was no answer. They had to believe, it was the only hope they had.

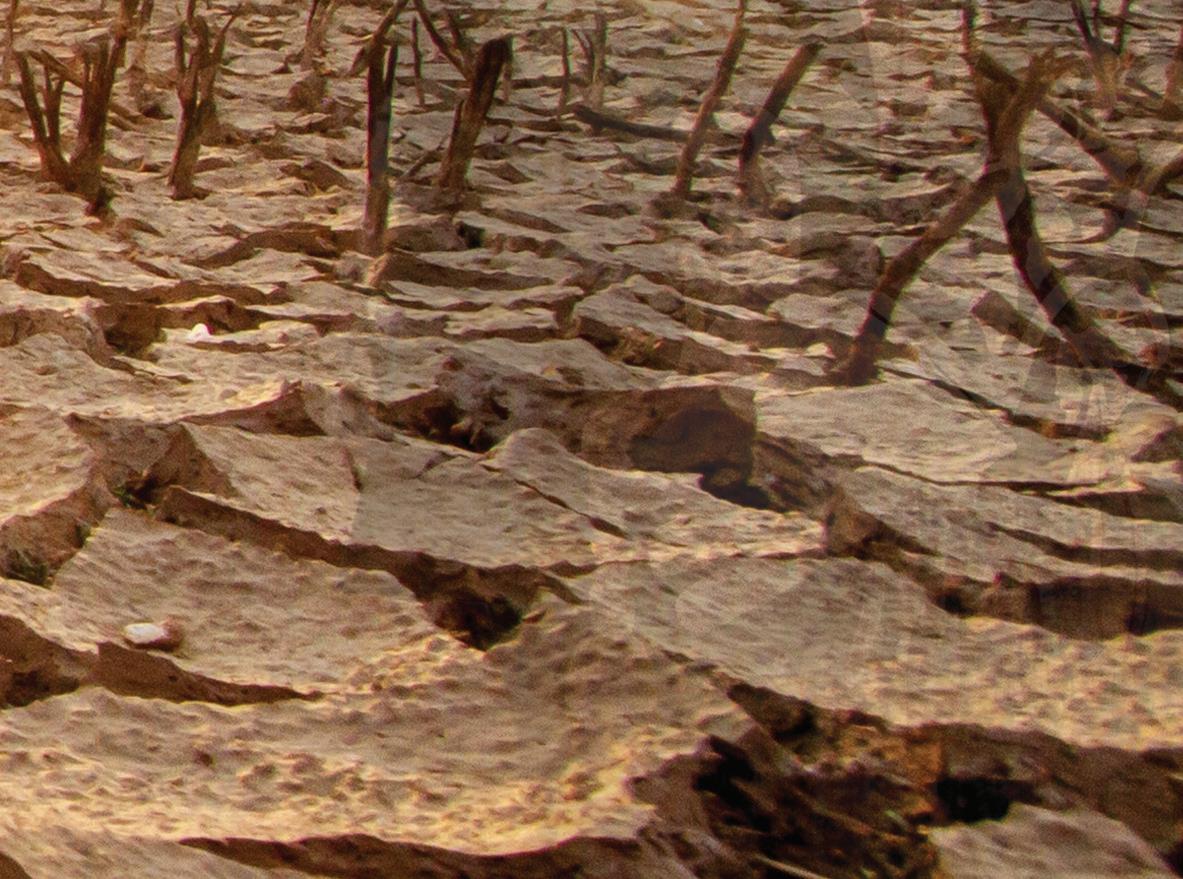

The debate had meandered on and Felaka had looked around his land from where he squatted and made his decision on how to vote. The soil on the land was baked and cracked and broken down to a fine black powder that the wind blew away in drifts to build up elsewhere as ridges. There was nothing left alive either in it, or on it. The corner that was the seed store in Felaka’s hut was swept clean, there was not one grain of t’eff left anywhere. The store had been getting smaller for the last six years. There hadn’t been enough grain left from each successive harvest to replace what they had been forced to take from the seed store as food to supplement a poor crop from the previous harvest. They had gone on saying that surely this harvest must be the last bad one, but the one the following year had been just as bad. Until this year. There had been no harvest. Field and store were empty. Everything was black, barren, bare. The council voted and decided that they must leave – immediately.

That was at sunset six days ago. The following morning they had left at first light, travelling in single file because of the narrowness of the track they had to follow. Everyone who was able had to walk, even the small children and those most feeble with hunger. The surviving babies were nestled on their mother’s backs, bound on by strips of cloth. They had to stop often and progress was painfully slow. And got slower as the days went by without food and those who started the journey weakest floated into the twilight of exhaustion. But

they had kept going on until they had arrived here last night, the feeblest ones shuffling forward with glazed unseeing eyes and a measured mechanical movement of body and legs that took no account of the irregularities of the path. Three of them had collapsed at the edge of the refugee encampment and were still lying there under their gabis.

Felaka stood on the ridge looking over the starving heads and wondered how long they could live. He thought of the families who farmed the surrounding land and whose village this was. They certainly wouldn’t have wanted to share any food they had. After all, their store of food would disappear within the hour if it was distributed among so many. They, who had some supplies, would be reduced to the same state as the refugees and could expect to die with them – soon. Felaka wondered if the farmers of the village had tried to hide some grain to keep it back for their own families, but he decided that the refugees would have expected that and would be keeping a careful watch on the tenant families of the village. They would know that they were being watched with suspicion and they would be frightened by this mass of condemned people. No, they would be forced to share their grain.

Felaka’s fear deepened. His mind made jumpy from hunger and exhaustion. He fought to control a train of thought. What could he do to help his own people, those who relied on his judgement and leadership? For whatever they said, or proposed in council, they would ultimately turn to him in their distress. He was alone, and there was no-one he could turn to, no-one he knew who could exercise any influence on this situation, no-one who could stop death. The only authority he knew that was greater than his own belonged to the landlord’s agent who came twice a year to collect the landlord’s tithe. Felaka had no idea how to find him, he just arrived twice a year with his servant and baggage, stayed for

one night and went on his way. Felaka wrestled with the idea of trying to find him, but he remembered the last time they had met and knew that the agent would not help. He had gone away in a rage without even resting for a night as was his usual custom.

He had called to collect the tithe that was due on last year’s harvest. Because there had been no crop, there was nothing on which the agent could claim his seventy percent. He had got into a frenzy, stamping his feet and shouting at the men. He raged that they were useless farmers not to have managed to grow something and that if his master, the landlord, had taken his advice in the past, they would have been turned off the land years ago. In any case, he had raged, this was the last straw and they could expect to be driven off the land just as soon as his master learned of their incompetence. There were many people, he said, who would be able to get a crop from such good land with or without rain. Felaka and his sons had said nothing, politeness and custom forbade them to argue or contradict someone as important as the agent. But they did nothing either. They knew the agent was wrong and that without water no-one could farm the land. They thought the agent a fool. “No” thought Felaka, “even if we knew where he was, we couldn’t ask him for help.”

Felaka’s stomach gnawed at him and he remembered Almaz. He realised that despite their journey, life would not be improved here, except that perhaps he could beg something to eat from any family fortunate enough to have anything left, anything at all. His spirit recoiled at the thought. Felaka the farmer, the head of a large family, he who had always provided, now had to go begging. But his stomach provided the stronger argument, it reminded him that Almaz also had the pains. He drew his skinny body upright and walked down the slope of the ridge and into the mass of people. As he picked

his way he saw that the people who were standing were all searching with their eyes as he was, scanning. Suddenly, several voices shrieked among a knot of people fifty feet in front of him and he was fleetingly aware of others rushing towards the spot. Without knowing what he was doing, he was scrambling with them. There was already a writhing pile of bodies on the ground and he was flung into the scrabble. He caught whirling glimpses of people tearing and clawing for something in the turmoil. A woman was flung past him with blood gushing from one eye. As she hit the earth and staggered for balance she clutched at the bloody mass above her cheek and something dropped from her hand. From where he crouched beneath her Felaka saw it fall and caught it before it hit the ground. He quickly pulled his hand under his gabi and crawled away to lie still.

Within another five minutes it was quiet except for the woman who sat gasping and sobbing, with her hands covering her face as blood trickled down her forearm. Felaka got up and walked slowly back to Almaz. He sat down beside her and as he pretended to rearrange his gabi he whispered, “I have a piece of bread.”

Felaka and Almaz had crawled over the ridge separately and now sat chewing and sucking at the bread they had divided between them. They each had a piece about three inches square.

In the thin morning air the sun climbed steadily up the bleached sky and looked down pitilessly on those it was destroying. There was no hope.

Chapter 1

ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA

SEPTEMBER, 1973

HIS EXCELLENCY SEIFU ASRAT, the Imperial Ethiopian Government’s Minister of Agriculture, snuggled into the upturned collar of his topcoat and pulled his scarf high around the back of his head. The night air struck chill against his glowing cheeks and it heightened his feeling of warm wellbeing wrapped inside his exquisitely cut vicuna and Italian wool. He glanced at the tall figure by his side as they moved out from the doorway, the tall figure with the long easy stride against his stiff gait with a jerk in the step. As soon as they stepped out the cloaked gatekeeper fell in behind them and the clamouring, child beggars fell silent and crouched mutely at the edge of the path with the upturned palms of their hands outstretched.

The pair swiftly crossed the forty yards to the dark silhouette of a Mercedes limousine without looking to either left or right and as the tall figure unlocked the driver side door the Minister walked around to the passenger side. The engine purred to life seconds later. The driver side window rolled down and the waiting gateman bowed low over his cupped

hands as fifty cents dropped into them. “Good night Excellency, good night balabar,” as he spoke the limousine moved forward and the window slid up, tight into its frame. Seifu sank deep into the seat and let the heated humming luxury swirl about him.

His brother-in-law drove with one hand resting lightly on the steering wheel as he lit a cigarette from the dashboard lighter. He exhaled and blew the smoke in a thin precise stream at the speedometer. “I wonder if we should try the sauna baths for a change one day? These hot springs are, well, rather old fashioned aren’t they?”

The Minister pushed the scarf back from his head and stretched his neck out of his coat collar like a turtle testing the temperature. He wriggled more upright in his seat. “I wouldn’t worry too much. They say the Emperor himself goes there sometimes. While the Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah deigns to wash off his fleas in those waters, no doubt the rest of Ethiopia will consider them a very proper thing.”

“I didn’t mean that. It’s just that the place is so old. All those green tiles and dampness.You never really feel dry until you get into the car. The sauna is new and properly laid out. Not damp everywhere. It has got air conditioning and when you finish with the hot room and the massage, there are cooler rooms to wind down in until you feel like changing. The whole thing is more civilized, more European.”

“That’s what you really mean – European. You would like all Ethiopia, or all of your bit of it, to be like Europe. You make a big mistake. You’ve been to school in Europe, you’ve been to university in Europe, and now you spend a great part of your time in Europe. But you forget. You forget where the money to pay for it all comes from. It comes from Ethiopia,

from the land of Ethiopia. I wouldn’t push too hard for European ways to be taken up if I were you. It might just get out of hand. If everyone starts pressing for more European ways, you might find they start agitating for land reform, for socialism. And then what? Then your land gets taken by a government and given to the peasants who farm it. Then all you will be able to do is think about Europe, because you won’t even be able to afford a ticket to get there, let alone live there.”

Seifu settled back into the leather seat of the Mercedes.

Seifu’s brother-in-law, Taye was a mulatto, a half caste –there really was no polite word to describe the children of the Italians left behind in 1939 who had married Ethiopian women and integrated into Addis society – married to Seifu’s sister. Seifu often envied his wife’s and brother-in-law’s close and easy relationship with their family in Sicily. They all four visited Sicily often, it was almost a second home to them.

Taye guided the car along the dark streets unmoved, smoking as precisely as he drove. “Perhaps things are already moving towards that end.”

“No. It’s only a theory.” Seifu swept his hand through the air to dismiss the notion.

“Maybe, but the news from the country isn’t good. I was going to ask you about it, anyway. I thought you might have heard something.”

“No, nothing. What’s happened?” Seifu asked the question out of politeness, not interest. Anything which was likely to affect him would turn up in his office – he was Minister of Agriculture after all. His information network was good; he didn’t need to go looking for problems – they came to him.

“My agent got back today from a tour of my land in the north and he says there is a famine. He says that the story

is that the small rains failed completely and there has been no second crop. That following the paltry big rains last year. Well, no rains really. He hasn’t collected one single grain in rent.”

“That may be his story, but the truth is more likely that he’s been getting into debt and had to pay your rent for his freedom.” Seifu was looking out of the window into the darkness as he spoke.

“He’s not stupid. If he was stealing he’d have at least something for me, he wouldn’t take it all. You expect them to steal a bit, but I’ve never heard of an agent brazen enough to do that. No, I believe him. He’s been with the family for years and he’s never let us down. He has certainly been told that there was no crop, and his own eyes would tell him if there had been rain or not.” Taye turned the Mercedes into the wide boulevard that passed the Imperial Palace. And Seifu suddenly realized where they were. “Are we going to the Hilton?” he asked.

“We always do.”

“If you want to continue this conversation, I suggest we drive out to the airport and back. I shouldn’t care for anyone to overhear this kind of talk.”

Taye let the Mercedes roll down the hill past the entrance to the Hilton and swung around the circle onto the airport road. The Minister sank down into the seat again and stared at the roof lining. A display of disinterest. “I say the agent has stolen your rent. His past record suggests it. We’ve heard that the small rains have failed for the last five or six years, but he’s always collected the rents, hasn’t he? In fact, you’ve always said that he is very efficient. It is remarkable that he suddenly can’t get people to pay up.”

“I said that to him. He says that they have been paying the tithes with the seed grain, or pooling resources with neighbours. But every time there has been a harvest after the big rains they have had to repay both neighbours and their seed store. That made a shortage in the new harvest so they’ve had to borrow again to make payment when the small rains failed. And so on for the last years. The effect has built up, accumulated, as the seed stores have dwindled. Until this year when there are no stores to raid for payment. None of them have any grain left.”

Minister Seifu closed his eyes and spoke sneeringly from the darkness. “Well, I hope you have told my sister this news. She will be most surprised to learn that land gifted by the Emperor can fail to produce a crop. I’m sure she thinks he really is God. You could suggest that she starts thinking of a few economies.” Seifu was beginning to enjoy himself. “It would stop her pitying me for a while. She might even start wondering whether or not it’s such a bad thing for me to have to work to live. To earn an income. At least it doesn’t depend on the weather – it depends on the humour of the little man, but I know the game and I can make some of the moves myself.” Referring to the Emperor as the “little man” would be enough to see Seifu jailed or worse. But no one except Taye was there to hear. He fell silent. His face had hardened, become sharper as he spoke of his sister and now his compressed lips turned slightly upward at the corners, almost smiled. His eyes remained tightly closed.

Taye remained silent. He felt there was more to come from Seifu. He wondered how to get Seifu back to his, Taye’s, own problem. But now that Seifu had worked his sister into the conversation he would adopt his most childish, scornful, manner. It was often the same. Almost unconsciously he twisted the conversation just to weave her into it and then

became absurd as he honed his envy against the thought of her. Taye inwardly writhed with impatience as Seifu went on in a fast taut voice. “A little financial setback really won’t do her any harm. She can try to remember what life was like without money. She had plenty of practice living on next to nothing before she married you. If her memory is good enough, she could be invaluable to you now.” Seifu snorted, “It might even make her a better person, you never know.”

Taye ignored the insult to his wife. He looked across at Seifu whose eyes were still closed. He tried again. “I really do think there’s a famine and I think it’s a bad one. The agent would have nothing to gain by lying about it – he thinks it is the beginning of a great famine. Perhaps greater than any that can be remembered.” Taye glanced at Seifu again. He hadn’t moved. He went on quickly, before Seifu could interrupt. “If it is a big one it could affect us all, not just the land owners and the farmers. And what about the farmers? No one here in Addis ever thinks of them. None of us. You accuse me of forgetting where my good fortune comes from because I’m often away, but people here in Addis, people who never leave Ethiopia, forget the peasants in the country just as easily as me.”

Seifu was sitting up now, his face and his voice relaxed, the crisis of his bitterness passed. “Bah. Nonsense. Why should anyone worry too much about them? They have their lives, and they live them out. Even if there is a famine there is nothing we can do, and if we all start worrying on their behalf, we’ll just add to the casualty list. The big rains can’t fail completely. They must be here in a couple of months or so and that will be the end of your famine. There have been grain shortages before, and no doubt there will be again, but the farmers carry on.

The dim night lights of the Bole airport buildings flickered into view as the Mercedes swung around the curve that took the road past a low spur of land and into the huge bowl where the airport stood. Taye let the car slow to roll round the roundabout at the airport intersection and then gently accelerated along the city-bound carriageway of the road they had just travelled.

Taye was thoughtful as he abstractedly lit another cigarette. He shifted in his seat and flexed his arms against the steering wheel. He realized that the minister was finished with the conversation and decided to close it down. He spoke calmly. “Well, I dare say you’re right. The agent frightened me a bit. I don’t know why I got so worked up about it, after all, the rents from these farmers will hardly make any difference to me if I never collect them again. It must have been the agent’s imagination that got hold of me. He was talking about famine leading to trouble for the government, peasants gathering and rising together and god knows what. Silly really.”

Seifu shot a glance at his brother-in-law, and his brow furrowed for a second before he controlled it. In the same relaxed, thoughtful tone he asked, “where did he get those ideas from?”

“From the peasants he saw travelling, I suppose.”

Seifu, now interested and alert, kept it out of his voice. “Farmers on the move? Where were they going? Maybe to beg some food from their neighbours I suppose, if some of them are really short.”

Taye wasn’t deceived, and wondered at Seifu’s sudden interest. What an extraordinary man he was. You never knew what turn his mind would take next. Taye had thought they

were done with the subject and now Seifu was beginning to pose questions as though he had just lighted on a new interesting topic. He sighed. Talking with Seifu was like this. Even when Taye started a conversation, Seifu would get hold of it and turn it into his own. It was frustrating.

“No,” Taye said heavily, “they were travelling. That’s what impressed the agent so much. They had packed up their farms, abandoned their possessions, and were making for an area just to the west of Weldiya. Apparently these people really had run out of food and they had heard that the farmers in this one small area still had some grain in store. He saw three families struggling towards the same place and he says that they looked as though they hadn’t eaten much for a while. Horribly thin, almost skeletal.”

Seifu was thoughtful, but spoke without betraying the interest that he felt. “I wonder how many will go there? I wonder if there are other gathering places as well?”

“The agent thinks there might be four of five places where there is still grain, so I suppose they will all attract people. Some had travelled six days to get to the place near Weldiya. That means the catchment area is big. There could be a thousand people, I guess. It could be less. The agent said that he’s certain that on one of my lands several of the elders and some babies have recently died. He said he was sure that the number of deaths had accelerated since his last visit. More than usual. More than he would have expected. He can’t prove it, of course, but I’ve no doubt he’s right. He’d be bound to notice. There’s no way of knowing how bad it is, but if some are dying on the farms, many more could die by travelling.”

Seifu was silent as he juggled his thoughts. There could be something in what Taye was saying. It wouldn’t be all that surprising if he hadn’t heard about it. The farms in the north

were isolated and the only news that came out arrived in Addis with the merchants and land agents like Taye’s who travelled the district collecting rents. In fact, it was recognized inside the government, but never spoken of, that the farmers’ very isolation could at times be useful. It was only when people were gathered together that unrest and discontent began to kindle. One of the reasons that the feudal landlord tenant system had survived so long was that farmers never had a real opportunity for discussion. They only met on holy days or, very occasionally, if they travelled to a market day. And then they would have too much business to attend to; they had no time for leisurely conversation. Of course there had been food shortages before and they had passed off without troubling the government for the same reason. People had died, but they had died on the family land and their loss had been quickly absorbed by people who always lived so close to death. It was an event kept within the family, even an extended one, living together and working side by side for their common survival. But now here was something unusual, something that could develop dangerously for the government and the established order, whole families travelling to the same place not for a market or church festival, but to live together, presumably until the rains arrived. That could be two or three months yet.

It could be a problem. The feudal system was entrenched and because of that, and the land’s isolation, there was no tradition of leaders rising up to lead the people. And he couldn’t remember them ever gathering together in the numbers Taye suggested, even for religious festivals. Distress and congregation. It was unlikely to lead to trouble, but one never knew. It made Seifu a little apprehensive. If any students from Addis had been on teaching assignment in the area when the grain shortage became apparent, there could be a problem. But

that was a long chance. Very unlikely. This new generation of students was full of ideas about the power of the people and the need for different government. But he thought, in the end, they were probably no different to their predecessors and would have got out quickly if they had encountered problems getting fed.

The thoughts had flashed through Seifu’s mind in microseconds. Now he frowned and looked away from Taye, out of the passenger side window as he spoke, “If the agent is straight, you’re right. It could just be serious.”

They drove on in silence, each lost in his own web of thought.

Two and a half hours later Seifu was home in his villa, sitting at the desk in his study with only the desk lamp for illumination. He pulled the telephone across the desk, lifted the receiver, and stopped. He tapped the receiver three times against his cheek and went to replace it. He stopped again with it poised just above the instrument, then let it drop into its cradle. He sat still for a minute, then decided. He lifted the receiver and dialled.

“Good evening Excellency . . . .yes, Seifu. I am sorry to trouble you in the evening but I have some business that I’d like to discuss fairly soon . . . .Quite, I could have phoned your secretary to do that . . . I’m not sure, but I do think we should discuss it . . . yes, that would be good . . . Same place? . . . at one? Good. Good night Excellency.”

Seifu took a Cuban cigar from the silver box on his desk, pierced it, then stared thoughtfully at it. He lit it with care and pushed his chair back from the desk. He sat in the dim light occasionally drawing on the cigar, mulling on his good fortune and the life he had constructed. He revolved Taye’s

words in his mind. Could this be a problem, a threat to that?

At twelve forty-five the next day Seifu was driving himself at a leisurely pace along the road out of Addis leading to the south-west. The sun beat down on the car and a haze shimmered on the tarmac road as it wound through the parched, yellow country. A fiery stream of air swirled in through the open window. It made no difference to the temperature, but it was easier to breathe the stifling air when it was moving.

His thoughts were going over the same ground as they had last night, and the frustrating irony of his situation tugged at him. It wasn’t unusual. He was going once again to do his duty as a minister and to protect the system from a threat. Of course, there probably wasn’t anything in the agent’s story at all but, all the same, if he did nothing, the possibility remained that something might just happen. In a way he would love it to. He loathed the Emperor and often, in his idle thoughts, plotted his downfall. He loathed him not for what he was, but because of his patronage and the dependence on his bounty that Seifu and his peers suffered to maintain their own way of life. The Emperor had made them what they were, and without him, or at his whim, they could equally well be unmade and thrown into poverty. Any rising of the people would certainly see that they were. Seifu knew that he and his government colleagues were the visible instruments of oppression and that the people resented his position as much as he resented the Emperor’s. So here he was on his way to report a danger that probably didn’t exist, but which a very few powerful people should be made aware of in case anything should develop. Haile Selassie had survived for almost half a century because of people like Seifu acting in exactly the same way. To protect themselves they had to protect the system – and the Emperor was the most important part of it.

Seifu came to a eucalyptus plantation that ran back from both sides of the road. The air in the shade of the trees was resin scented and cool and Seifu gulped it eagerly. He slowed toward the end of the stand of trees and immediately past them turned right, off the road and bumped over a wooden bridge across a drainage ditch into a rough field. He turned in an arc to park facing the ditch and road. He looked round and noted with satisfaction that there were only three other cars there and one of them was the improbably red Mercedes that he had hoped to see. Seifu got out and eased his trousers from the back of his thighs and adjusted his jacket with a shrug. He gave the carpark guard a short jerk of his head as he walked, dragging his left foot slightly, to the bridge. He stopped on the bridge and looked back at his white Peugeot 504. The sight of it usually filled him with pleasure, but now he ground his teeth. That, he thought, was part of the reason he was here, protecting the system.

He limped across the road and through the ramshackle double gates set in a corrugated iron fence painted green many years ago. He stepped into the courtyard of an Italian colonial home. A verandah ran around the three sides of the courtyard on which stood tables with white cloth tablecloths set for lunch. In the centre of the courtyard a single olive tree grew from a hole in the stone paving and in its shade a single dining table was laid. At it sat a large shambling figure, facing the gateway and drumming long bony fingers on the table. Seifu limped toward the table as smoothly as he could, conscious of his disability under the gaze of the occupant.

His Excellency Aklilu Habte Wolde, minister in charge of the Emperor’s personal cabinet office, the most powerful appointed official in Ethiopia, looked unblinking at Seifu.

“Good afternoon.”

“Good afternoon Excellency.”

Aklilu waved at the vacant chair. “Sit down. What will you have to drink?”

“A beer, I think.”

Aklilu raised his hand without looking round and a waiter scurried to the table from his station at the verandah steps. “A beer and a bottle of Ambo.” Aklilu never touched alcohol. The waiter ran back up the steps. “Shall we order straight away? Then we can dispense with the waiter.” The waiter reappeared with the drinks and they ordered. Then sat in silence – neither of them had anything to say to the other. After a few minutes the waiter returned with thin chicken soup and lasagne. Aklilu took a noisy slurp at his soup, then looked up, “I assume it’s something important?”

Seifu hesitated. “Well, it could be. It could be nothing.” He shrugged. “But then it might.”

“Another plot against His Majesty?” Aklilu looked irritated. “You’ve already had one of those this year and I’ve heard of two more in the last month.

“No, it’s not.” Seifu was hurt. Now he’d make Aklilu ask. Silence.

After a while Aklilu spoke, “My apologies. What is it?”

Seifu relented. “I’ve had a report of famine starting up in the north. Apparently there is evidence that it is serious. People are already dying.”

Aklilu nodded over his soup, “Yes, I’ve heard rumours myself. A couple of people with land up there say they’ve had trouble collecting rent. They’re upset but we need to keep things in perspective. You and I both know that there have been some grain shortages for the past few years and

the small rains failed again up there, I am told. So it’s not unreasonable to expect the same thing as in the past. There’s little we can do, but we’ve kept the extent of the problem pretty much under control.”

“If you mean we’ve prevented news of the shortages becoming generally known, then you are right.” Seifu replied.

“Exactly so. After all, it has been very localized and there is nothing we can do except stop alarm spreading. Turning a relatively tiny problem into panic. We don’t want the whole province panicking over something controllable within a small area. One of our prime objectives is surely to preserve stability. Without that, nothing can be done.”

Seifu nodded. “That’s true. And we have been successful. Very few people learn of these little problems. If they had got widely known, I’m sure there are elements in the population that would use them to stir up trouble.” Seifu rehearsed the government patter that he had heard before, almost parroting Aklilu; “and then it is impossible to give a complete picture of government strategy to the people. These small events could derail the government’s overall objectives if they get overblown. We can only ever give so much information and news of food shortages would create pressure of a size out of all proportion to the problem. It would put the government in a difficult position.” Seifu heard himself with distaste. “Has His Majesty mentioned it?”

Aklilu looked up from his empty bowl and pushed it away. “He doesn’t know. In some ways he is like his subjects; inclined to ignore problems of governance to pursue some unimportant, trivial matter. When it’s looked at in its proper place, this is a small local problem. And so His Majesty has not been told of it.”

There was silence until Seifu finished his lasagne and Aklilu signalled the waiter to bring the second course. Aklilu now prodded at half of a spit roasted chicken and Seifu delicately examined an escalope, lifting the edges and peering under it, as though he expected to see something. Eventually he cut a small piece and slowly chewed. After a while he spoke again, being careful in his choice of words: “All of that is true and has been up until now, but the most recent news could, I think, be more far reaching.”

Aklilu looked up, “How’s that?”

Seifu rested his knife and fork on his plate and leant forward, elbows resting on the table. He appeared thoughtful. “Well, it goes back over the last five years of bad rains. Apparently one of the reasons that these people have survived is that each year they have been eating some of the next year’s seed grain.”

“Makes sense,” Aklilu shrugged as he hacked at the chicken.

“Yes, but each year they have had to take a bit more from the already diminished supply. They have never repaid the previous year’s borrowing. Their stock of seed grain has got smaller and smaller from year to year until this year when, apparently, a good number of them have no store at all.”

Seifu watched alarmed as Aklilu crammed a large forkful of chicken into his mouth and a glob of sauce ran down his jacket lapel. Aklilu didn’t notice and spoke through a halfchewed mouthful. “That’s bad. Difficult for those who have run out. Big rains can’t be far off though. They’ll be able to borrow, barter from neighbours, I’m sure.”

Seifu became a little excited. The older man didn’t seem to grasp that he wouldn’t be here speaking unless there was

something out of the ordinary in the situation. He picked up his knife and fork and collected himself.

“It’s serious. A great number,” he stressed the words, “A great number of them don’t have any grain. In fact I’ve heard there have already been deaths.”

“How many.”

“I don’t know. Some of the weaker people, old people, babies I am told.”

Aklilu, unperturbed, continued to chop at the chicken carcass, “but you can’t say it’s serious if you haven’t any figures, and how do you know that deaths are from starvation? They could be from smallpox, cholera, typhus, anything.”

“You are right, of course, but there is something else that makes it look more serious. It’s why I thought you should know about it.” Seifu bent over his plate and looked at Aklilu from under his eyebrows. Aklilu was now wrestling with the chicken’s bones. “What is it?” he grunted.

“I’ve heard that people are leaving their land and gathering together.”

Aklilu looked up from his private field of destruction and peered at Seifu as though he had seen him for the first time. As though a mist had cleared.

“They’re doing what?” he asked, amazed.

“Gathering in crowds. That’s why I thought it might be worse than usual.”

Aklilu wrinkled his nose and fixed his eyes on Seifu, “I don’t understand. Why are they doing that?”

Seifu spent a long time chewing. He was pleased with the response he had drawn. Now the old man was interested, he

thought. Finally he swallowed and spoke slowly. “If it’s true, then they are obviously out of grain. What I heard is that there is still some grain from the land around one of the lower lying villages, a village west of Weldiya. The news got around and people are travelling there. Apparently from quite a way off. So a sort of encampment is forming.”

Aklilu still peered at Seifu, almost in disbelief. “This is remarkable. I can’t remember it ever happening before.”

“Neither can I,” Seifu shook his head.

“How many of them are there?”

“I don’t know. There may eventually be hundreds, maybe a thousand. Who knows? If it’s bad enough to have started a migration, then I’m sure more will follow.”

Aklilu returned to forking over the carcass left on his plate, but in a slower, more thoughtful manner. “Do you think they’ll be gathering elsewhere?”

Seifu had a sensation of deja vu about this conversation, but fought it off.

He thought to himself that everyone who served in this administration thought in the same way. It was their common instinct for survival.

“Well, I’ve been told that there could be a few other places with some grain in the province. Maybe three or four. But that’s a guess. I’ve no idea and no other information about people moving. The point, the worrying thing, is that for tenants to leave their land their need must be desperate. They lose their home and livelihood when they leave. Land the family has lived on and farmed for generations.”

Aklilu pulled at his chin. “Yes, but what might happen if people gather? Without work, without food. They could

become dangerous. Mobs. That would be a worry.”

“That’s what I wondered,” replied Seifu. “That’s why I thought I should speak to you.”

“I’m grateful that you have. I’m not sure what we can do, but we can plan. We are forewarned. I wonder who else in Addis has the same information.”

“Not many people, I’m sure,” replied Seifu. “My information came through two people, and they won’t let it go any further.” Seifu had cautioned his brother-in-law before he left him last night.

Aklilu surveyed the wreckage on his plate. “I’ve heard one or two landowners whining, as I said, but none of them has come up with a story like this. If I move quickly, I can silence them in any case.”

“It would be a good idea, I think. If this gets widely known it could create serious trouble for the government” Seifu pushed away his empty plate and Aklilu sat back in his chair, “Yes, you’re right. We’d soon come under pressure and that could escalate to more discontent. Then we’d have to restrain the malcontents and the government would attract criticism for restraining them. We’ve seen the same cycle recently. I’ve no wish to repeat it. We’ll be better able to cope if we keep this within the government, perhaps best if just between ourselves.”

“Will the landlords be difficult?” asked Seifu. “They won’t like losing their rent.”

“No” Aklilu shook his head, “I don’t think so. The only people they’ll willingly tell are me or His Majesty. And they’d only do that in the hope of being given more land to make up their income. I can listen to their petitions, their complaints, promise to deal with them. I don’t have to hurry. And

they won’t discuss it with one another for fear of losing face. One of the most useful reins with which our countrymen can be steered, Ato Seifu, is that. Their fear of losing face. They won’t tell each other that their wealth is diminished.”

“And His Majesty? What about His Majesty?”

“That is not a problem.” Aklilu spoke briskly, “No one sees His Majesty without coming through me. As you well know, I will not allow His Majesty to be troubled by trivial matters.”

“I wondered if you thought perhaps His Majesty should be told,” Seifu spoke hesitantly, “perhaps by you?”

Aklilu threw out an arm in a gesture of appeal. “To what end? His Majesty might seize on the issue as something for his special attention – he is strangely affected by some things these days. And he would run ahead, issuing orders without any regard for the consequences and the problems they might create for the government. It would make our effort to control the situation hopeless. Besides . . .”

“Yes, Excellency? Something else?” The waiter appeared at Aklilu’s side and neither of them had seen him approach. Aklilu turned to the man and became aware of his outstretched arm. The waiter had obviously seen it as a summons. Aklilu looked closely at the waiter. His expression revealed nothing.

“Yes,” Aklilu said, “creme caramelo for me and . . .” he looked across at Seifu, “and for me too.”

The waiter retreated and Aklilu looked questioningly at Seifu who shook his head and shrugged. They sat in silence until the dessert arrived. Once they were alone again Seifu spoke, “you were speaking about His Majesty.” Aklilu looked around again before he spoke. “Yes, well, yes.” He was now

hesitant. Although he and Seifu had a working relationship, he didn’t quite trust him. But then he didn’t quite trust anyone. It was how he had survived in his position for many years. He struggled within himself and decided. “Frankly, I shouldn’t care to tell His Majesty about this. I can’t always read him recently. If he decided to be interested, he would want to know why he didn’t know of the problems the last few years with the small-rains failing. That would all become an issue if he got involved in this situation.”

“And that might be difficult for you.” There was a slight note of malice in Seifu’s voice.

Aklilu countered sharply. “And for you too. You are Minister of Agriculture, Ato Seifu.”

There was a pause of a few moments. They were both thinking of the Emperor’s stone cold rages and of his absolute power of appointment and dismissal.

“I take your point. It might be best if we can deal with it without His Majesty.” They sat on for several minutes, the only sound the weaver birds chattering in the tree. Finally Seifu broke the silence. “What else can we do? You can prevent gossip from travelling either up or down, as it were. It’s unlikely that news of the situation will get out at the moment, unless someone that we can’t account for knows about it.”

Aklilu looked around the courtyard and up at the pale blue sky. He spoke slowly, almost thinking aloud, “unless there are travellers or students doing their teaching practice. Farenji travellers would be the most difficult. Thinking they are helping. But it’s difficult to travel up there. No one is likely to have done it for fun and I don’t think there are any aid projects in the province. Have you ever been there?”

“No,” Seifu replied, “I haven’t. We’ll just have to trust

that no farenji are there now. It’s unlikely, but they do odd things. A farenji woman once went through the whole of the Simian on a donkey. The students are the most likely problem. I imagine they would have got out quickly if food ran short though. I doubt there are any there now. There won’t be any in the area of this village anyway. At the most there might have been one of two teaching in the elementary school in Weldiya and it’s possible that news hasn’t even reached Weldiya. These villages are way back in the mountains.”

Aklilu gave a dismissive shrug. “The students are controllable anyway. Our information system inside the university and teacher training place is good. We have nipped several of their plans in the bud. They don’t have a newspaper or a union. The Emperor didn’t think it a good idea. So information, such as it is, travels by word of mouth, and we can monitor and channel that.”

Aklilu scrubbed at the shiny folds of his face with his napkin. “Nothing more we can do at the moment. To do anything at all might be to over-react and, anyway, we have no idea how bad this is. Come to that, here is no real proof at all. Really how good is your information?”

“It’s reliable. It comes from a source that I trust – especially over a matter like this. I’ve no doubt the problem exists and that the people are leaving their land and gathering.”

“I suppose it’s something to be sure of that even. But I wish we had information about the numbers involved.” Aklilu kept abstractedly dabbing his face with his napkin. “I think we can keep a grip on the situation – unless it gets worse.”

Seifu relaxed a little. “It won’t get much worse. The big rains will arrive in six, eight weeks at most. I don’t believe they will fail completely. They never have and I doubt they ever will.”

Aklilu nodded. “Of course you are right. The big rains will come sooner or later in a greater or smaller quantity. But they will come. We’ve just got to control the information until then. If we can do that, then the problem will pass.”

“Yes,” Seifu nodded in agreement, “once the rains come they will return to their farms with or without seed grain and somehow get going again. Smaller families won’t even be a bad thing. Regrettable, but their first harvest will be small if it is sown with borrowed seed.”

They sat looking round the dusty courtyard. The sun vibrated off the stones. The silence only disturbed by four weaver birds squabbling in the branches of the olive tree. Seifu felt the vastness of Africa about him. He said, “the remoteness helps deal with the problem. It is possible that no one else will ever know about it. Even if they do, by the time news gets out the rains will have come and it will be over.”

He looked across at Aklilu who had closed his eyes and rocked back in his chair. He looked, for all the world, as though he was asleep.

Chapter 2

ADDIS ABABA

BRITISH EMBASSY

SEPTEMBER 1973

FRANCIS SHAW, Her Britannic Majesty’s Ambassador to Ethiopia sat at his office desk with his back toward open double french doors. He sat upright, hands resting palm down on the edge of the desk. Hands aligned over knees. Stiff, like a window dresser’s dummy. To his mind a “dignified attitude.” Appropriate for a representative of Great Britain to this remote land. Accessible by a weekly airline flight from three carriers and a decrepit rail line from Djibouti on the Red Sea, but still largely unknown. The corner of Africa never really colonized by Europeans. The only African country to have repelled colonial forces twice. Italy both times. Shaw felt he somehow represented an outside, developed, world.

Which is why he felt it appropriate to maintain his London wardrobe. With carefully arranged sparse dark hair, charcoal gray business suit, black oxford shoes from Lobb’s in St James’s Street, laundered white shirt and college tie replete with small diamond pin, he could be on his way to lunch at his London club. But he wasn’t. He was stuck here

in this minor diplomatic outpost. He had really hoped for more towards the end of his career.

The large shambling figure sitting in the wooden visitor chair across the desk could not have presented a greater contrast. Either in dress, demeanor or attitude. His baggy sports jacket hung open revealing a cotton v-neck pullover that could have once been beige, protecting a checked shirt and floral tie. Dennis Wilkins, forty-three, Counselor at the embassy, number two in the diplomatic hierarchy, was looking abstractedly past the Ambassador through the open french doors to the neatly trimmed grass and the blue wall of eucalyptus that marked the edge of the embassy compound.

Wilkins pushed his fingers through his pile of sandy hair as he shifted uncomfortably in the hard wooden chair. “I don’t remember, Wilkins, how you came to know Mary Pierce in the first place.”

“We play in a string quartet together.” His reverie interrupted, Wilkins replied abstractedly, without changing the direction of his gaze.

“Oh. she’s in that, is she.” said more as a slightly disapproving statement than a question.

“Yes, she plays the cello.”

“And this musical friendship led her to tell you about a famine?” Shaw was irritated. This kind of information was an intrusion on what he thought of as his diplomatic duties.

“Yes, perfectly natural, I suppose. She doesn’t mix much with the expat community outside of the Mission. I’m probably the only person she knows here at the embassy. She wanted to tell someone. She was distressed. I think she thought that by telling me, she would have made someone aware without a lot of inquisition, red tape . . .” Wilkins’ voice trailed off.

“Well, I can see that.” Shaw realized he had appeared antagonistic and needed to be a little conciliatory. “What’s she like? I mean, you obviously think she’s reliable, otherwise you wouldn’t have taken her seriously, but some of these missionaries are a bit odd, aren’t they? Perhaps I should say, ‘eccentric’ – it’s a better word.”

The Ambassador looked carefully at Wilkins. He hadn’t meant to say either odd or eccentric. He did think that Wilkins fitted both words pretty well himself. Not that he wasn’t brilliant. Shaw acknowledged that, but it was the way he dressed, and some of the things he was interested in, well . . . he wasn’t the first embassy official to go native.

Wilkins was unaware of the Ambassador’s glance. He turned in his chair and threw his weight on the other arm, his eyes roamed restlessly around the Ambassador’s collection of water colours depicting the English countryside that hung on the wall behind the desk. “She’s quite sound. She’s been here fourteen years, speaks fluent Amharic and Oromo and has a deep knowledge of Orthodox religion – quite interesting when she talks about it. She edits, and mostly writes I suspect, the Amharic newspaper that the mission puts out for the Orthodox Church. She’s not nutty like some of them, if that’s what you’re thinking.” Wilkins smiled as he said it. Mary was the least “nutty” expatriate that he could think of. In the four years he had been in this post in Ethiopia, he had become close to Mary. Chamber music wasn’t the only interest that they shared, they were both interested in anthropology, prehistory really, particularly the excavations being conducted by the French team at Melka Kunture, just thirty miles from Addis. They visited whenever they could during the digging season. Wilkins and Mary were serious people with serious interests. Mary was far from “nutty.”

The Ambassador cleared his throat. “Some of these people do exaggerate a little though, don’t they? They do it because they think no-one listens to them.”

“Not her, she’s been here too long.”

“Well, I rely on your judgment, not that I doubt her, of course.” Shaw added hastily, hearing the pomposity in his own words. He usually tried to appear a little more approachable when he dealt with Wilkins. In truth, he was slightly in awe of the man’s accomplishments, his languages, his music, his interest in pre-history. “What did you say she was actually doing in the north when she found these farmers?”

“It was part of her newspaper work. She’s doing a series of articles about the Church, religion, and its meaning in different sections of society. She wanted to interview some of the tenant farmers in the more remote communities. When she got there, not easy by the way, she found an abandoned tenancy. As she travelled deeper into Wollo, she found more people clearly on the edge of starvation. She wasn’t able to get a fix on how bad it might be. She wanted to go back with a medical team.

“Very laudable. I do hope she got the directions right. I wouldn’t want young Cornick to have been on a wild goose chase.” Cornick was the most junior of the embassy’s professional staff and this was his first posting.

Wilkins shrugged, dismissing Shaw’s comment without recognition or reaction and looked at his wristwatch. “We’ll soon know, his appointment is at ten.” And as he spoke the Ambassadors’ English carriage clock struck the hour. The ambassador pressed the key on the office intercom. “Is Mr Cornick here yet?”

“Yes, sir.” There was suppressed laughter in the voice.

“Ask him to come in, please.” The Ambassador spoke in the clipped polite tone reserved for conveying disapproval to junior staff. Especially secretaries with the giggles.

Jim Cornick gangled into the office and danced, heron like, from one leg to the other, just inside the doorway. He wished he hadn’t been clowning with Kate. He had heard the edge in the Ambassador’s voice.

“Good morning, Cornick.You’re back in one piece?” The Ambassador relaxed his voice to a little more friendly.

“Good morning, sir. Yes, I am thank you. Good morning Dennis – Counselor.” He remembered the Ambassador’s insistence on formality at official meetings just in time. He tried to speak slowly, in a lower voice – more diplomat-like. He was tormented by what he thought of as his over-squeaky voice. He winced. He was sure he had squeaked, ‘counselor.’

“You’re preparing a written report.” A statement not a question.

“Yes, sir. I got back late last night and I’m working on it.” Cornick lied, he hadn’t started it.

The Ambassador had guessed that. “Quite. That’s why the Counselor and I would like a verbal report now. Give us an overview, an outline. It could be important – at least so far as giving the situation serious consideration goes.”

“Yes. sir.”

“So sit down and tell us about it.” The Ambassador indicated the visitor chair across from Wilkins.

Cornick sat down and crossed his legs. Then uncrossed them. Perhaps that was too informal at meetings with the Ambassador. Cornick hoped he hadn’t noticed. He glanced at Wilkins slumped in his chair. He was senior enough for it

not to matter. But Wilkins was aware of Cornick’s discomfort. He tried to ease his path, “How did you get on? Pretty difficult journey, I imagine?”

Cornick seized the opening. “Yes, it was, we had lots of trouble with the local big-wigs. They didn’t want us to travel into the interior at all. That was obvious.”

“Hold on.” Wilkins held up his hand. “Let’s get the whole trip straight in our heads from the get-go. Imagine it’s the written report. Start from the time you left here, go step by step. Slowly.”

Jim Cornick looked ill at ease and fidgeted with his hands. Wilkins caught his glance and nodded encouragingly. Cornick gathered himself and plunged off again.

“I’m sorry.” He paused to slow and lower his voice, “I left the day after we met, Friday, as soon as it was light, about five thirty. I took Assefa to act as guide and we had decided the night before to take the Land Rover as far as Weldiya and to go off road from there by mule. Assefa comes from the area and he said that Miss Pierce’s instructions would set us in the right direction, but he couldn’t say beyond that as he didn’t know exactly where we were going. Neither did I. We were looking for an area where, according to Miss Pierce, we would find people in distress.”

The Ambassador looked enquiringly at Cornick who was momentarily held by his gaze. “We did. We found people visibly starving.” Cornick swallowed, remembering the sight. “Very, very thin. Skeletal, almost like Oxfam ads really.” Cornick was visibly shaken by the recollection.

The Ambassador nodded and sat back in his chair with his hands resting on the chair arms.

“Anyway” Cornick went on, speaking a little more quickly,

“We arrived at Weldiya around five o’clock and then came our first problem. We needed to hire mules, and there weren’t any. No one seemed to know why, or at least they weren’t saying, until Assefa went into a buna beit, chatted to the owner, and found out. They were all dead. The mules usually for hire belong to local farmers. When the rains failed again there wasn’t any grazing and the farmers were using everything edible for themselves. The animals began to starve and eventually they were butchered as one of the last sources of food.”

Wilkins puffed his cheeks and let the air explode through his pursed lips. Cornick carried on. “The next morning, Saturday, Assefa left early and was gone about three hours and when he came back said he’d managed to fix something up. A man he had spoken with at the buna beit the night before thought he knew where there were still two animals belonging to a tenant farmer out to the east. He agreed to go with Assefa to see if he could hire them. He did and arrived back with them on Saturday afternoon. They were in terrible condition and I didn’t think we’d get far on them. We exchanged half of our canned rations for the mules and then loaded them with the rest. They would never have carried us. So we walked alongside them.

“Next day was Sunday and we couldn’t do anything so we managed to buy some feed at an incredibly extortionate price and feed the mules. It was strange. In Weldiya there was animal feed in the store but the price was maybe ten times the going rate here in Addis. No way could the farmers have afforded it.

“Monday we went early to the District Governor’s office. There were a number of people hanging around outside with two policemen watching over them from outside the office

door. We were sent straight in although I suspect the other people had been waiting a while to see him. Do you know him?” Cornick looked at the Ambassador then at Wilkins.

“No,” said the Ambassador. Wilkins shook his head.

“He’s a retired Brigadier. Quite an impressive figure. He was very polite and asked us what we needed the mules for. He’d obviously heard about Assefa’s efforts in the buna beit. I said I was working in Addis and wanted to see some of the country before I left and that I’d been told that it was possible to trek to the rock churches from Kobo. I think he was genuinely surprised by that. Maybe it was a mistake. Anyway. He was very discouraging. He said he didn’t think it was possible, especially with our two scraggy animals. I asked him if we could get better ones and he became guarded. I said it seemed strange there weren’t more beasts around. He blustered, but didn’t say anything about the animals dying.

“We didn’t get anywhere with him but before we left he tried jolly hard to dissuade us from going off road. He said there were bandits in the hills, the peasant farmers were anti-Europeans, there was no water because it was the dry season and that we wouldn’t be able to carry enough for more than a few days. In fact, that was a good point. Without pack animals we’d have to limit ourselves. We couldn’t rely on active springs when we didn’t know where or how to look for them. In the end he gave in, just warned us not to travel too far from the road without sufficient water. He suggested we forgot the churches. I think he thought that I was slightly mad. Crazy English. He definitely didn’t want us nosing around.

“So we set off with the two mangy mules. We calculated we had enough water for five days and we didn’t see a spring the whole journey. We were in the bush from Tuesday

morning until Saturday, four nights. It really was very rough going. We were always pulling on the mules to get them up the slopes or hauling back on them to stop them from sliding down the scree. I doubt we covered much distance measured in a straight line. Everywhere we found people, food was obviously short. The people and animals are all thin, emaciated in many cases. Every single person we encountered asked for food. Begged almost. We gave away more than we ate of our own supplies. Difficult to say just how bad it is. Some people obviously still had some stores, but they all looked to be in poor shape. I shouldn’t think they’ve eaten properly for some time. Trying to spin out dwindling supplies, I suppose. Assefa says that some of them told him they couldn’t last out much longer because their stores were practically exhausted. We found two tracts of land deserted – apparently the farmers had travelled south. There’s a rumour that there is still some grain in one spot to the west of Weldiya. Some of the people Assefa spoke to were leaving to go that way themselves. They said it was their only hope.”

Wilkins bent forward in his chair. “ Did you get any idea of how widespread the food shortage is?”

“No. We didn’t really. The further we got from the road, the worse it looked and we certainly didn’t see any land that looked as though it had born a crop recently. Most of what had once obviously been fields were barren stretches of land with deep cracks crisscrossing the surface.”

The Ambassador cleared his throat with a cough. “Do you think it’s a famine? A famine. Not just a shortage?”

Cornick looked at the Ambassador apprehensively. He was nervous of overstating the case, being the cause of alarm, the catalyst starting action. He felt too junior to shoulder that responsibility. “I can’t say. I don’t have any experience

to compare with. I’ve never seen a famine, but I’ve never seen so many people in such obvious distress. Some of the sights were awful. Pathetic. Sad. The children were the worst. Distended stomachs and arms and legs that are just bones covered with skin.”

Cornick paused and thought for a moment, the silence and stillness only broken by the twittering of the weaver birds outside. It seemed unreal, sitting in the heavy, plush room discussing what had been so tangibly squalid to him only three days ago. His judgment wavered.

“Some of the people we saw had a little food. I don’t know how much. The signs of starvation are there, the people are hungry, ravenous. I don’t know.” Cornick pulled at his cheek, uncertain.

The Ambassador leant back in his chair, tilted his head back and looked down the line of his nose. “Supposing that relief was available, would it be welcome? Do they need it?”

“Certainly.” Cornick snapped the word. He had made the decision almost unconsciously, overcoming his fears, and replied emphatically. “What I saw was hunger. Real hunger, starvation if you like. They need it alright.”

Silence fell again. The Ambassador and Jim Cornick sat motionless but Wilkins flopped restlessly in his chair. Eventually the Ambassador spoke. “Well Cornick, you’ve had a hard week. We need to think this over carefully. We need your written report. Can you get that done by tomorrow morning?”

“Yes, sir.”

“So we won’t delay you. We’ll talk again when we have the report.”

The door clicked shut behind Cornick and Shaw and Wilkins sat looking at one another.

“What do you make of it?”

Wilkins grabbed at his hair and tugged on it as he spoke. “In a way we’re in more of a quandary than before he went. We know there’s some sort of shortage for sure. But what does that mean? How bad is that? How widely does it stretch? How can Cornick judge? He has no experience of the country, let alone famine.”

“Cornick was the wrong chap to send really. He’s very inexperienced.”

“But we had to,” Wilkins said with a touch of exasperation, “it’s his job.”

“True,” rejoined Shaw.

“Beats me why London promoted him so young. They thought he’d be out of the way here, I suppose. They’d be right ninety-nine percent of the time.”

The Ambassador snapped back to business mode with a jerk. “Let’s think this out. We now know there is a grain shortage but no idea of its proportion. How big or how bad. Cornick more or less confirms the report of the Pierce woman, so in a way we have two independent witnesses. I wonder how bad she really thinks it is.”

Wilkins didn’t react to Mary being described as “the Pierce woman” but he was in a tight spot. He didn’t want to throw too much weight, too much accountability, on Mary Pierce. It seemed ungallant. But she had been firm in her opinion.

“She said it was serious. She saw starvation and, in her opinion, some of the children might not survive much longer.

She does have a great deal of experience here and probably a more informed view than Cornick. On the other hand, she has no idea of the breadth of the problem either. It’s pretty difficult trekking off-road up there.”

Shaw had picked up a paper knife and was smoothing the blade between his fingers. “Did she actually say it was a famine?”

Wilkins was being tortured with indecision, between putting Mary in the position of being accountable to Shaw and her own drive to see something done. He replied slowly, thoughtfully, “Yes, she did, but it’s an emotive word. One could say famine without using the word precisely. There must be a technical definition. She may have seen a shortage but shortage, famine, who could tell?”

“Well, you say yourself that she has a lot of experience here and whether she meant the word technically or not, famine only means one thing in most people’s minds.”