Zen Pathways

An Introduction to the Philosophy and Practice of Zen Buddhism

BRET W. DAVIS

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Davis, Bret W., author.

Title: Zen pathways : an introduction to the philosophy and practice of Zen Buddhism / Bret W. Davis.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021035257 (print) | LCCN 2021035258 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197573686 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197573693 (paperback) | ISBN 9780197573716 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Zen Buddhism—Philosophy. | Zen Buddhism—Doctrines.

Classification: LCC BQ9268.6 .D386 2021 (print) | LCC BQ9268.6 (ebook) | DDC 294.3/420427—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021035257

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021035258

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197573686.001.0001 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Paperback printed by LSC Communications, United States of America

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

With nine deep bows of gratitude, I dedicate this book to the memory of Tanaka Hōjū Rōshi (1950–2008) and Ueda Shizuteru Sensei (1926–2019)

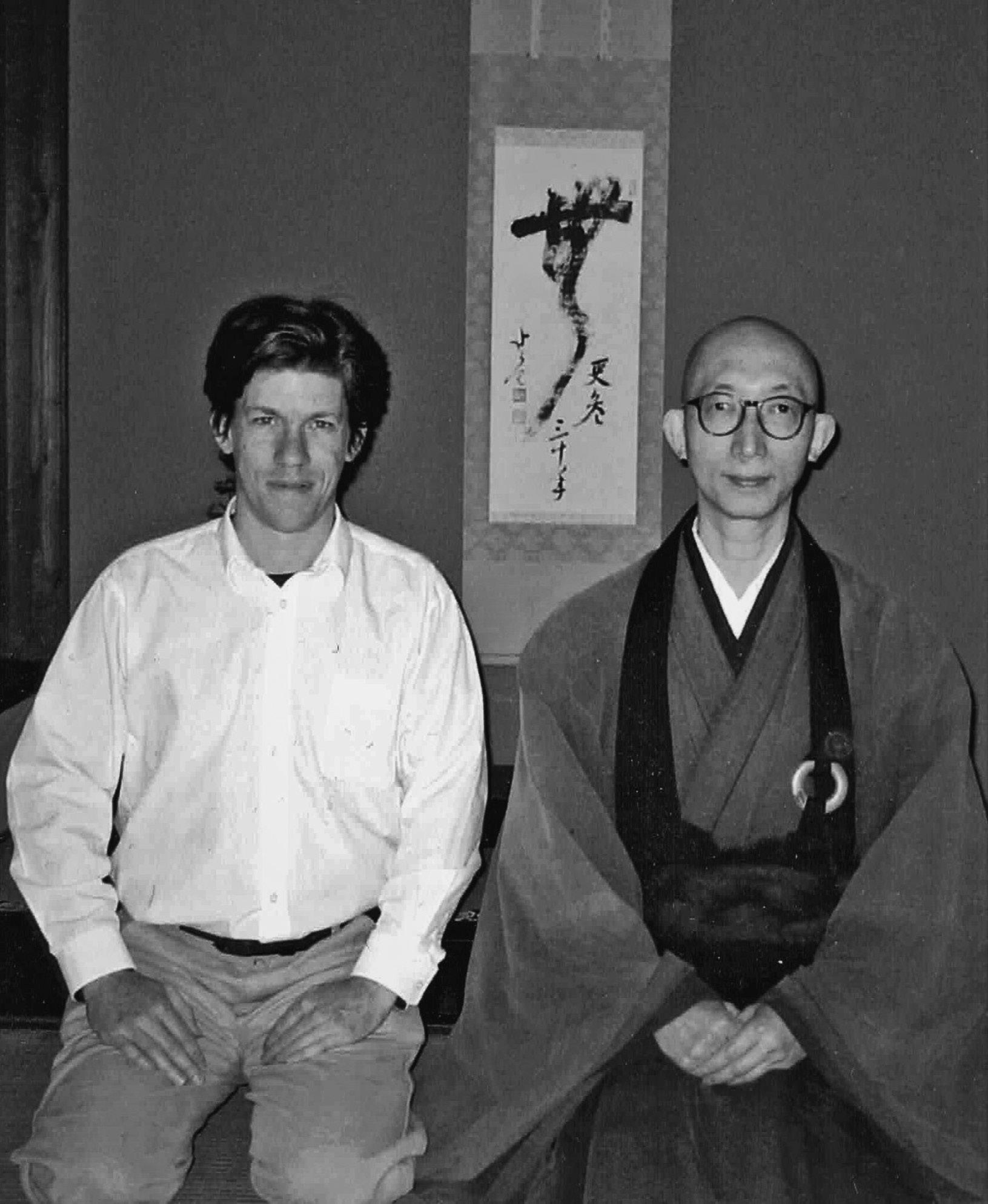

Tanaka Rōshi fulfilled his vow to become an “educator of educators.” For a decade he guided me in my practice. Time and again I entered the electrifying atmosphere of his interview room to be tested on kōans. Often swiftly dismissing me and my muddles with the ring of a bell, his compassionate severity allowed me to undertake an “investigation into the self” more rigorous and more revealing than I could have imagined. That decade of doing sanzen with him changed my life. Tanaka Rōshi wrote very little. He taught with the living words of his speech, with his piercing gaze, and with his ear-to-ear smile. He exemplified Zen for us with the crispness of his movements and with the purity of his motives. May some of the spirit of his holistic pedagogy flow through these pages to benefit its readers and all who are, in turn, touched by their lives.

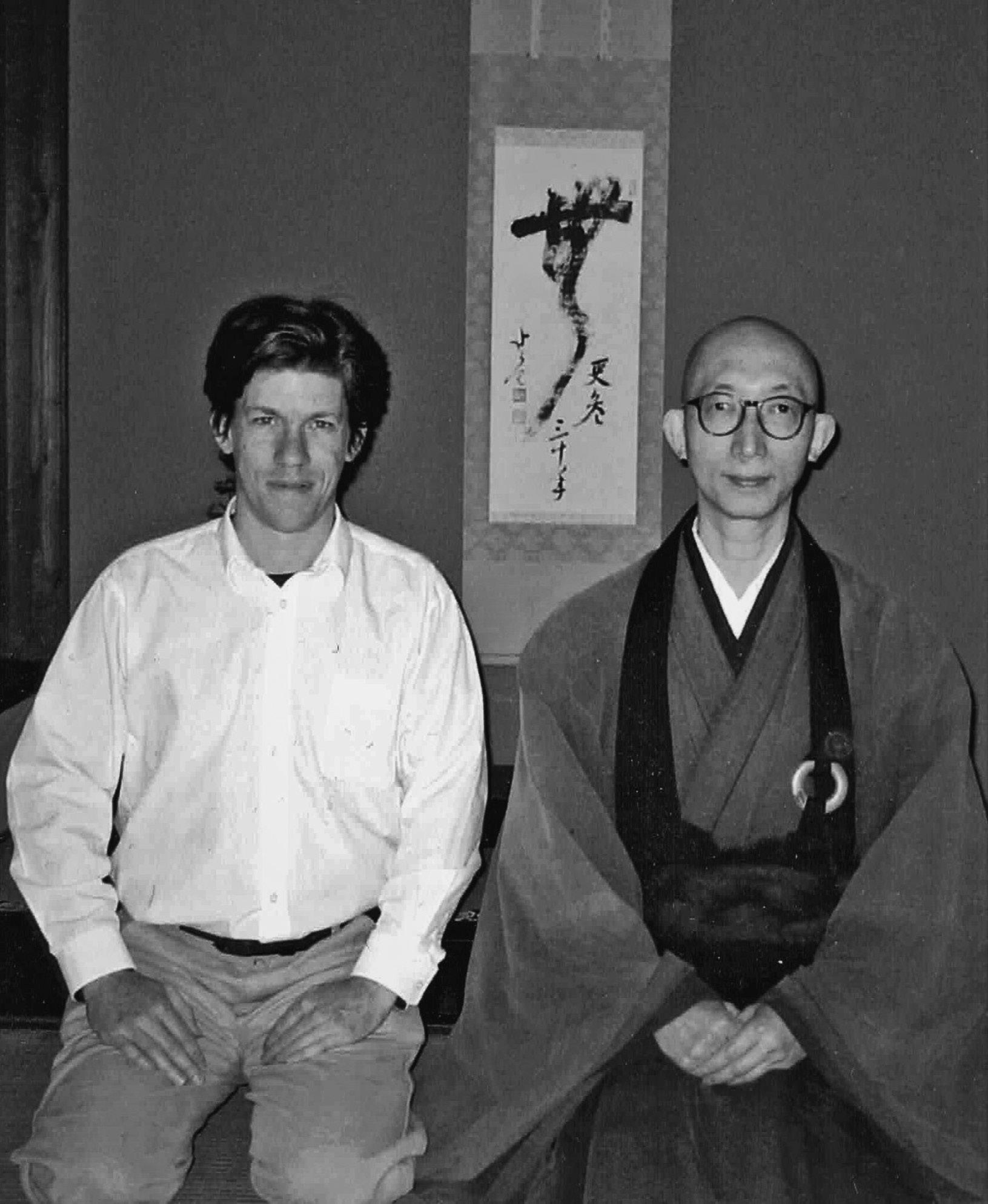

For nearly a quarter of a century I had the great privilege of learning directly from Ueda Sensei in both scholarly and Zen contexts. He modeled for me what it means to walk the parallel paths of Zen and philosophy, allowing them to illuminate and enrich each other without compromising the distinct nature and rigor of either one. Ueda Sensei’s profoundly insightful philosophical interpretations of Zen inform many pages of this book. Tanaka Rōshi’s successor and my current teacher, Kobayashi Gentoku Rōshi, asked Ueda Sensei to formulate the Zen layperson’s name (kojigō) that I was given: Kanpū 閑風 (literally “peaceful wind”). Ueda Sensei used one of the characters from his own given name: the kan in Kanpū is another reading of the character for shizu in Shizuteru 閑照 (literally “peaceful illumination”). I am deeply honored to carry forth part of his name along with his mission of relating, without conflating, the Eastern and Western paths of Zen and philosophy.

Figure 0.1 Author with Tanaka Hōjū Rōshi in Shōkokuji monastery, Kyoto, November 2004

Figure 0.2 Author with Ueda Shizuteru Sensei at his home in Hieidaira, August 2012

Gateless is the Great Way. It has thousands of different pathways.

Wumen, The Gateless Barrier

Your journey begins here.

Printed on a piece of trash sojourning on a sidewalk in Baltimore

20. Zen and Language: The Middle Way Between Silence and Speech

21. Between Zen and Philosophy: Commuting with the Kyoto School 275

22. Sōtō and Rinzai Zen Practice: Just Sitting and Working with Kōans 290

23. Death and Rebirth—Or, Nirvana Here and Now 302

24. Reviewing the Path of Zen: The Ten Oxherding Pictures

Preface

Why Write or Read This Book?

Why write or read a book on Zen when it is claimed that Zen is “not based on words and letters”? Well, since there is no first word in Zen, there can be no last word. Precisely because, for Zen, it is not the case that in the beginning was the Word, there can be no book or collection of sayings that says it all. That is why every new Zen teacher leaves a record of his or her teachings. That is why every new encounter can become a new kōan. Every new context calls for a new text, a text that tries to leave some life in the printed words, to leave at least a vivid trace of the living words that are—as Zen master Dōgen puts it—“expressive attainments of the Way” (dōtoku). The reader is invited to revive the verbiage.

For more than a century now, Zen Buddhism has been in the process of transmission from Japan and other parts of East Asia to the United States and other Western countries. The modern Western recontextualization of this age-old tradition has, appropriately, called forth many new texts—as did the eastward transmission of Buddhism from India to China in ancient times.

But do we really need yet another introduction to Zen? After all, there already exist many shelves of books on Zen, more than a few of which are written by authors who are—either as scholars or as teachers—more qualified than I am to write about Zen. Nevertheless, as a philosophy professor who studied with the contemporary representatives of the Kyoto School in Japan for many years, as a scholar who is fluent in Japanese and proficient in reading Classical Chinese, and most importantly as a longtime lay practitioner who has been authorized to teach Rinzai Zen, I hope that this book makes a unique contribution, one that will be welcomed especially by readers who are interested in both the philosophy and practice of Zen.

Toni Morrison famously said, “If there’s a book you really want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” I hope that there are some students, scholars, lifelong learners, and philosophically minded Zen practitioners who will appreciate my attempt to write the book that I wish had been there for me to read more than thirty years ago, when I started down the parallel pathways of Zen and philosophy. Now, I wish someone else had written this book so that I could use it in my college courses on Asian and comparative philosophy and religion.

I should mention that my Zen training has for the most part been undertaken in Japan, where I resided for thirteen years, and where I continue to spend much time during sabbaticals as well as summer and winter breaks. Since I have not been affiliated with any of the Zen establishments in North America or Europe, I feel somewhat “outside the loop” when I read accounts—such as Rick Fields’s How the Swans Came to the Lake: A Narrative History of Buddhism in America, Helen Tworkov’s Zen in America: Five Teachers and the Search for an American Buddhism, and James Ishmael Ford’s Zen Master Who? A Guide to the People and Stories of Zen of the incredible efforts that have been made over the last half century to transmit Zen to North America. When I read such books, or articles in such magazines as Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, and when I visit the established Zen centers in the United States, I feel like I’ve arrived unfashionably late to a party that is already in full swing; perhaps a bit like a Japanese monk who returned to Japan after spending years in China learning Zen in the fourteenth century, only to find that a couple of earlier generations of Chinese and Japanese monks had already done the heavy lifting of transmitting Zen from China to Japan. In any case, I hope that my unusual mixture of academic and Zen training has enabled me to belatedly add a minor new voice to the booming cross-cultural chorus involved in the ongoing movement of Zen Buddhism around the world: in the past from India to China to Japan, and onward in the present to the United States, Europe, and elsewhere.

Allow me to introduce myself in just a little more detail, so that readers have a better sense of whose voice is speaking through the printed words of this book. While living in Japan for much of my twenties and thirties, and during numerous stays since returning to the United States in 2005 to begin my career as a philosophy professor, I have endeavored to follow in the giant footsteps of Kyoto School philosophers and lay Zen masters Nishitani Keiji and Ueda Shizuteru, who spent their lives commuting between the academic study of philosophy and religion at Kyoto University and the holistic practice of Zen at the nearby Rinzai Zen monastery of Shōkokuji. After graduating from college in 1989, I spent half of the next seven years studying philosophy in a PhD program at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, and half studying Japanese, practicing Zen and karate, and teaching English mainly at a Buddhist university in the vicinity of Osaka, Japan. After going back to the States for a couple of years to finish my coursework at Vanderbilt, in 1996 I returned to Japan to live for eight and a half more years, this time in Kyoto. There, I studied Buddhism at Otani University for a couple of years, and then undertook doctoral studies and postdoctoral research in Japanese philosophy at Kyoto University. I also taught philosophy, religion, and ethics courses at universities in the area. All of this study and teaching was done entirely in Japanese, which is also the language I have spoken at home for the past three decades. Alongside my academic activities in Kyoto, I commuted

regularly to, and sometimes lived in, the monastery at Shōkokuji in order to practice Zen. For a decade I worked on kōans under the direction of Tanaka Hōjū Rōshi, and after he passed away in 2008, I have continued this practice under the direction of Kobayashi Gentoku Rōshi. In 2010, I was officially authorized by Kobayashi Rōshi as a teacher (sensei) and director of a Zen center (dōjōchō).1

In fact, with Tanaka Rōshi’s permission and encouragement, in 2005 I founded, and since then have directed, The Heart of Zen Meditation Group, which meets in a remodeled “meditation chapel” at my home institution in Baltimore, Loyola University Maryland.

This book is the hybrid fruit of, on the one hand, more than three decades of practicing and more than a decade of teaching Zen, and, on the other hand, more than three decades of studying and two decades of teaching Western, Asian, and cross-cultural philosophy. The bridge builders between these two disciplines, in whose footsteps I have tried to follow—albeit starting from the Far West rather than from the Far East—are those Kyoto School philosophers who have both practiced and reflected on Zen. Especially important for me have been the central figures of the first three generations of the Kyoto School: Nishida Kitarō (1870–1945), Nishitani Keiji (1900–1990), and Ueda Shizuteru (1926–2019).

Nishida understood the essence of religion to be the direct self-awareness obtained through delving deeply into the basic fact of existence. And he understood the essence of philosophy to be an intellectual reflection on that selfawareness.2 Human beings, Nishida thought, need both.

Another prominent Kyoto School philosopher and influential lay Zen teacher, Hisamatsu Shin’ichi (1889–1980), expressed the relation between philosophy and religion as follows:

Philosophy seeks to know the ultimate; religion seeks to live it. Yet for the whole human being, the two must be nondualistically of one body, and cannot be divided. If religion is isolated from philosophy, it falls into ignorance, superstition, fanaticism, or dogmatics. If philosophy is alienated from religion, it loses nothing less than its life. . . . Religion without philosophy is blind; philosophy without religion is vacuous.3

When Hisamatsu says “religion,” he mainly means Zen practice and the experience of awakening to the “formless self.” In fact, he was quite scathing in his critiques of Christianity, Pure Land Buddhism, and other religions that preach salvation based on faith in a higher power outside the self. By contrast, D. T. Suzuki (1870–1976), along with many Kyoto School philosophers—including Suzuki’s lifelong friend Nishida, and also Nishitani, Ueda, and Hisamatsu’s student Abe Masao (1915–2006)—were interested not only in pointing out various differences but also in pursuing parallels between Zen and the profoundest

theological, buddhological, and mystical teachings of Christianity and Pure Land Buddhism.

Some readers may wish to think of Zen teachings and practices in terms of “spirituality” rather than “religion,” insofar as “religion” connotes for them institutional establishments and dogmatic creeds more than liberating and enlightening personal experience. Yet if we think of “religion” etymologically as re-ligio, and if we understand this to imply a way of reuniting with the ground and source—or source-field—of our being, then perhaps they might feel more comfortable with the term. In any case, the present book is less concerned with the history and sociology of Zen as an institutional religion and more concerned with elucidating and philosophically interpreting its most enlightening and liberating teachings and practices.

To be sure, a lot of mischief, hypocrisy, and abuse has also gone on in Zen institutions, as is sadly the case with other religious traditions. One can and should read books that investigate such matters. Although this book is written more for philosophically minded spiritual seekers than for critically minded sociologists and historians, I do make an effort to take the latter kind of research into consideration, and also to point out what I see as certain potential shortcomings and pitfalls of Zen practice and philosophy (such as those involving erroneous anti-intellectualism or harmful antinomianism) that must be heeded and avoided.

The word “spirituality,” it should be remarked, has its own problems. It cannot be applied to Zen if it indicates a concern with the spirit as opposed to, or as separable from, the body and the material world. Yet if “spirit” is used—as it sometimes is—as a holistic word for what encompasses and pervades our whole body, heart, and mind, then Zen can indeed be understood in terms of spirituality. Zen practice is holistic. It engages the whole psychosomatic person, which, moreover, it does not dualistically separate from the whole universe.

Buddhism has always been an exceptionally philosophical religion. Indeed, it is for this reason that Zen masters have often felt the need to push back against what they saw as an overemphasis on intellectual reasoning and textual study in the Buddhist tradition. Their counterbalancing stress on embodied-spiritual practice over merely cerebral intellection remains an important lesson for many of us today. However, the counterbalancing pendulum has sometimes swung too far in the opposite direction, with some teachers and especially their epigones suggesting that philosophical thinking and scholarly studies are not only unnecessary but even antithetical to Zen. Especially in some of his early writings, the pioneer Zen spokesperson in the West, D. T. Suzuki—himself, ironically, an avid and prolific scholar—at times left readers with that impression. However, as will be discussed in Chapter 21, in his later work Suzuki increasingly stressed the need to articulate a “Zen thought” and even a “Zen logic” rather than resting

content with only “Zen experience.” It is important to bear in mind that those past Zen masters who tried to wean their students from an overreliance on the intellect were often themselves learned and sharp thinkers. The thirteenth-century Japanese Zen master Dōgen, for example, was an ingenious philosopher and erudite scholar. At the same time, as will be discussed in Chapters 20 and 22, Dōgen too stressed the importance of regularly putting aside texts, putting on hold intellectual reasoning, and wholeheartedly engaging in embodied-spiritual practices, especially the silent practice of seated meditation.

Those Kyoto School philosophers who were also dedicated Zen practitioners—Nishida, Hisamatsu, Nishitani, Abe, Ueda, and so on—have done the Zen tradition, and the world at large, an indelible service in reconnecting the embodied-spiritual practice of Zen with rigorous philosophical thinking, and also with pioneering a dialogue between Buddhist and Western philosophy and religion. That is why, as a student who was committed to philosophy yet not wholly satisfied with its exclusively intellectual approach, and who thus took up a parallel practice of Zen, I was drawn to follow in their footsteps and to commute between the university and the monastery. What I offer in this book is the fruit of that commute: an introduction to Zen that pays due attention to both its practical roots and its philosophical leaves.

Tips for Using This Book, and Conventions Used in It

Although it is based on decades of academic research along with practice and teaching, I have endeavored to write this book in an accessible and engaging manner. It is primarily addressed to college students and other newcomers with a philosophical as well as practical interest in Zen (even though I certainly also hope that seasoned scholars and practitioners will find in its pages fresh takes on familiar teachings). For this reason, I have tried to keep the main text uncluttered with scholarly references to terms and texts. For those who are interested in delving deeper into an issue addressed in the main text, the notes provide references and suggestions for further thinking and reading. Although I encourage students to study—and appreciate scholars who work in—multiple languages, and although my own study and practice of Zen have been undertaken largely in Japanese, given the introductory nature of this book I have limited my references mainly to sources in English, except in cases where I am quoting from or drawing directly on a non-English source that has not been translated. I have noted cases where I have modified or redone existing translations, either to make them more faithful to the original or to make them fit with the conventions and style of this book. In cases where only a non-English source is cited for a quotation, translations are my own.

In the main text, Chinese, Japanese, Sanskrit, and other non-English terms are used sparingly. I have transliterated terms using the English alphabet and, except for macrons over certain Japanese vowels, I have not used diacritical marks. When original-language equivalents are provided for some key terms, and when it may not be clear from the context which language the terms are from, I use the following abbreviations: P. = Pali, Sk. = Sanskrit, Ch. = Chinese, Jp. = Japanese, Gk. = Greek, Ln. = Latin, and Gm. = German. To keep things simple, I use Sanskrit (e.g., Nirvana, anatman) rather than Pali (e.g., Nibbana, anatta) versions of equivalent terms, even when referring to teachings and texts from the Pali canon. For Chinese terms and names, the now standard Pinyin (instead of the older Wade-Giles) method of transliteration has been used. East Asian names are written in the order of family name first, except in cases where authors have used the Western order. In such cases, the original language order will be given in parenthesis after the first appearance of the name—for example, Shunryu Suzuki (Jp. Suzuki Shunryū) and D. T. Suzuki (Jp. Suzuki Daisetsu).

I use the familiar Anglicized Japanese term “Zen” throughout rather than “Chan,” “Seon,” or “Thien” when referring to the Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese pronunciations of the same sinograph: 禪, simplified in modern Japanese as 禅. East Asian countries all adopted the sinographs, or Chinese characters, from China in ancient times. The Japanese language still uses them today. Sinographs for many key terms in Chinese and Japanese are provided in the index, as are diacritics for some key Pali and Sanskrit terms. Although there is no distinction between lowercase and uppercase letters in these languages, I frequently capitalize key terms in order to emphasize their importance and indicate respect—not in order to reify or deify their referents.

The chapters in this book are like summary snapshots of my current understanding of what I consider to be the most important and interesting topics in Zen practice and philosophy. I hope that readers will approach each chapter as an initiation and as an invitation to further study and practice, a portal through which they can access a field of inquiry and discussion. Scholars, practitioners, and other readers who want to broaden and deepen their study of Zen, or students who want to dig further into a specific topic for a research paper, can mine the notes of the chapters that address the topics in which they are most interested for sources and suggestions for further reading.

In the back of the book can be found discussion questions for each chapter. Professors may want to use these for assignments; general readers may want to peruse them in order to pique their interests and prep their minds before reading each chapter; study groups may want to use them to stimulate discussion of the main ideas in each chapter.

The chapters have been organized such that the book unfolds as a comprehensive introduction to the practice and philosophy of Zen. At the same time, each

of the relatively brief chapters has been written such that it can be read on its own. Each chapter focuses on a single issue or cluster of ideas, which its title is meant to display. This means that readers don’t necessarily need to read the whole book; they can easily zero in on the topics that most interest them by browsing the table of contents in the front of the book or the discussion questions in the back—or they can use the index to research specific terms and explore the ways in which they are discussed in various contexts across the book. Professors should be able to easily select a set of chapters to fit with the content of their courses and within the space available on their syllabi.

For example, readers interested mainly in practical instructions for meditation can focus on Chapters 3, 4, and 22. For readers interested in attaining a more accurate and in-depth understanding of topics that are popularly associated with Zen in the West (including meditation, oneness, karma, being in the zone, art, and kōans), I recommend Chapters 1, 3, 8, 15, 17, 19, and 22. Readers interested in a Zen interpretation of basic Buddhist teachings and in Zen’s relation to other schools of Buddhism can focus on some or all of Chapters 5–7, 10–12, 15, and 23. Readers interested in interreligious dialogue between Zen and Christianity can focus on some or all of Chapters 1, 7–15, 21, and 23. Readers interested in specific areas of philosophical inquiry such as metaphysics, epistemology, ethics and society, or nature, art, and language can focus on a relevant selection from Chapters 2, 3, 8, 9, 11, 14–16, and 18–21.4 Readers interested in the nature of the self (i.e., philosophical anthropology) can focus on Chapters 2, 7, 8, 9, 11, and 24. Those who want to cut to the chase and get a quick preview of the path of Zen as an “investigation into the self” can start with Chapter 2; then, if they want to get a fuller overview of the entire path of Zen, they could jump from there straight to Chapter 24.

Acknowledgments

Most of the first draft of this book was written during a sabbatical leave granted to me by Loyola University Maryland for the academic year 2018–19. That earlier and briefer version became the basis for a series of lectures recorded and released in video and audio formats under the title Real Zen for Real Life by The Teaching Company as part of their Great Courses series. I thank The Teaching Company for permission to publish a substantially reworked and expanded version of this material in the form of a book. I also thank The Teaching Company for, in the first place, convincing me to attempt to address a wider audience in a more direct and personal manner than I am used to doing in my more exclusively academic writing. I sincerely thank Peter Ohlin at Oxford University Press for taking an interest in and supporting the project, and Madeleine Freeman, Leslie Johnson, Koperundevi Pugazhenthi and others involved at OUP and Newgen for their congenial and careful work on its production.

Readers of this book may be surprised to learn that my personality inclines me to keep my most intimate thoughts and experiences to myself. Because of that inclination, combined with my enculturation in the self-effacing and reticent ethos of Japan, I have, up until this point, been hesitant to write directly about my practical experience of Zen. Yet, after my much more extroverted mother passed away in 2009, and then after I turned fifty a few years ago, I decided it was time to stick my neck out of my introverted shell and—as my brother Peter likes to say—to put myself out there, for better or for worse. I don’t know if I have managed to find the appropriate middle way between the unwholesome and unhelpful extremes of being “stingy with the Buddha Dharma,” on the one hand, and spreading “the stench of Zen” by flaunting my personal experience, on the other, but I have tried, with the hope that including some personal anecdotes and other autobiographical references along the way will make the book more engaging and thus more impactful.

I am accustomed to composing scholarly articles, and writing this book for a wider readership of students and lifelong learners has enabled me to find a more candid and straightforward voice, one that is somewhere in the triangulated middle of the academic voice I use when addressing other scholars, the pedagogical voice I use in the classroom with college students, and the more intimate teaching and testimonial voice I use in meditation meetings with fellow practitioners. I thank my academic colleagues around the world, the many students I have been privileged to teach at Loyola University Maryland and in

Japan, and the members of The Heart of Zen Meditation Group for allowing me to cultivate these three voices. I now hope that the synthesis of these voices forged in the writing of this book manages to speak to the integrated body-heartmind-spirit of its readers.

It is not possible to adequately acknowledge all the people who have aided me as I’ve walked and crisscrossed the paths of Zen and philosophy. I can only single out a few people and a few of the ways in which they have influenced and enabled me on this journey. I have dedicated this book to Tanaka Hōjū Rōshi and Ueda Shizuteru Sensei, who, as I stated on the dedication page, were pivotal to my practice and study of Zen, and thus to my life. The other Zen teacher to whom I am profoundly indebted is Kobayashi Gentoku Rōshi. After Tanaka Rōshi passed away in 2008, Kobayashi Rōshi became the abbot of the monastery at Shōkokuji in Kyoto. Having long known him as a monk, and for many years as the head monk at Shōkokuji, since 2008 I have continued my practice under his guidance during my periodic sojourns in Kyoto and during his mostly annual visits to Baltimore. Given that I am an academic philosopher by profession, Kobayashi Rōshi has made sure that my practice does not get overly mired down in “bookish Zen” (moji Zen).

The monks at Shōkokuji alongside whom I have had the privilege to practice over the last quarter of a century are too many to mention by name— most of whom, in any case, I only know by their monastery nicknames. The fellow lay practitioners and scholars of Zen with whom I have practiced and studied in Japan are also too many to list, though I would like to single out a few. Horio Tsutomu, one of Nishitani Keiji’s last students, tutored me regularly on Nishitani’s texts at Ōtani University while I was taking classes in Buddhist studies there from 1996 to 1998, before he graciously encouraged me to transfer to Kyoto University. A very accomplished lay practitioner, Professor Horio made the introductions necessary for me to begin my practice at Shōkokuji in 1996 as a member of the lay practitioner group, Chishōkai, whose past members have included eminent Kyoto School philosophers such as Nishitani Keiji, Tsujimura Kōichi, Ueda Shizuteru, Hanaoka Eiko, and Ōhashi Ryōsuke. It was inspiring to sit for many years in the same zendō (meditation hall) and even on the same wellworn cushions as these path-making predecessors, and an honor to sit alongside fellow inheritors of this lineage such as Akitomi Katsuya, Minobe Hitoshi, and Mizuno Tomoharu, as well as other “Way-friends” (Jp. dōyū) such as Steffen Döll, Yoshie Takami, and many others. I’d also like to mention in this context Professor Kataoka Shinji, a Chishōkai daisenpai (great predecessor) whom I never met, though I lived for a time in the same room of the head monk’s quarters at Shōkokuji that he once occupied. A renowned lay Zen master and a professor of education at Kyoto University, it was Professor Kataoka who inspired Tanaka Rōshi to set out to become an “educator of educators.” For most of the

years I lived in Kyoto, Matsumoto Naoki served as the leader of Chishōkai. He and I spent many moons practicing together, including many long nights sitting side by side under the moon doing yaza (night sitting) during intensive meditation retreats (sesshin).

Again thanks to Professor Horio’s mediation, I was able to participate in the last two annual meetings of the landmark Kyoto Zen Symposia in 1997 and 1998. It was there that I first met a number of leading scholars who would, over the years, become my good friends as well as mentors; these include John Maraldo, Mori Tetsurō, Thomas Kasulis, James Heisig, Rolf Elberfeld, Graham Parkes, Thomas Yūhō Kirchner, Matsumaru Hideo, Michiko Yusa (Jp. Yusa Michiko), and Fujita Masakatsu. Professor Mori does his Zen practice elsewhere, but I was able to study many Kyoto School and Zen texts with him and other members of the Kufūkai research group he leads. Although Professor Fujita is not a Zen practitioner, I learned a great deal from him about Nishida and other Kyoto School philosophers while I was a PhD student and later a postdoctoral research fellow in the Department of Japanese Philosophy at Kyoto University between 1998 and 2004.

Before moving to Kyoto in 1996, I lived in Osaka from 1990 to 1994. During those years I spent many evenings, weekends, and vacations “temple hopping.” Among the places where I got my Zen practice under way was Shinshōji International Zen Training Monastery in Fukuyama, where I often spent several days, and sometimes several weeks, learning the basics of monastic life. One of the places I regularly attended meditation meetings near my home in Osaka was Shitennōji, an ancient temple complex founded by the legendary Prince Shōtoku in the sixth century. At the time, I was teaching at Shitennōji Buddhist University, where all classes begin with a brief meditation.

Nowadays, I must admit, I don’t begin all my classes at Loyola University Maryland that way. However, I do offer students in my courses on Asian philosophies the option of doing a “meditation path,” which requires them to regularly meditate on their own and with The Heart of Zen Meditation Group, and to reflect on their experience in relation to assigned readings. I am very grateful to Loyola for supporting my use of this experiential pedagogy, and, moreover, for providing me with the use of a chapel that has been beautifully renovated in a Japanese style with tatami mats and meditation cushions. My senior colleague Drew Leder has been a constant source of encouragement and support, as well as a co-conspirator in engaging our students in this holistic pedagogy, as has more recently my junior colleague Jessica Locke. Drew has also inspired and assisted me in incorporating an alternative “service-learning path” in some of my classes. To be able to discuss Buddhist texts and teachings together with some students who are meditating and others who are doing community service—is this not how it should be? It is certainly teaching me a lot.5

Let me thank by name some of the current regular participants in The Heart of Zen Meditation Group: Ethan Duckworth, Ed Stokes, Janet Preis, Mickey Fenzel, Janet Maher, Steve DeCaroli, Jeffrey McGrath, John Pie, Rhonda Grady, Bess Garrett, Susan Gresens, Phil Pecoraro, Carl Ehrhardt, Cheryl McDuffie, David Gordon, Bu Hyoung Lee, Ilona McGuiness, Drew Leder, and Rick Boothby. Former students who have continued or come back to sit with us include, among numerous others, Coleman Anderson, Patrick McCabe, Alex Kasinskas, Samantha Kehoe, Daniel Napack, and Will Stann. Among the many hundreds of other students who have participated in The Heart of Zen Meditation Group over the years, let me single out one of the very first: Luke Dorsey. Luke was one of my first students at Loyola and, to this day, maybe the most enthusiastic one. He even visited me in Kyoto one summer when I was staying in the monastery of Shōkokuji. I remember him patiently kneeling for nearly two hours listening to a talk by Ueda Sensei, of which he could understand not a word. I also remember taking a walk with him on the Kamo River and getting attacked from behind by a hawk trying to steal our ice cream sandwiches. After he graduated, Luke continued to attend our weekly meditation meetings in Baltimore—until he went to bed one New Year’s Eve and never woke up. His picture adorns our group’s altar, along with a picture of Michael Prenger, a buoyant and sturdy ship captain and a contagiously committed meditator who sat with us for several years prior to his passing, and a picture of Father Greg Hartley, a joyful Jesuit priest who ran a Zen meditation group at Loyola before I started teaching there in January 2005, and who suddenly died from a heart attack a month after I arrived. The “Heart” in the name of our group is, in part, a tribute to the legacy of Fr. Hartley.

Beyond Loyola, let me thank Kōshō Itagaki, Tetsuzen Jason Wirth, Shūdō Brian Schroeder, and Jien Erin McCarthy, together with whom I founded CoZen, a loosely organized group dedicated to bringing Zen practice and academic philosophy into a fruitful partnership. Participants in the CoZen Symposia I have led at Istmo—an idyllic retreat center in Panama run by my brother Sean and his wife, Ayesha—have included fellow philosopher-practitioners Carolyn Culbertson, Brad Park, Gereon Kuperus, and Matt Swanson, in addition to many of the CoZen and Heart of Zen Group friends already mentioned. Among family members, as always, I’d like to thank my children, Toshi and Koto, as well as my brothers, Peter, Chris, and Sean. For this book, I’d like to single out the two most important women in my life: my mother, Barbara Stephen Davis (1938–2009), and my wife, Naomi Tōbō Davis. My mother was an open-minded spiritual seeker as well as a devout Christian. She always and unreservedly supported my philosophical pursuits and wandering ways, even when my spiritual quest led me to fly far away from the nest in which I was raised. Whatever regrets she had about our Episcopal church’s failing to fully satisfy my search seemed to be redeemed by the vicarious joy with which she shared my

journey into Zen practice. The connections I have more recently been able to make between some of the profoundest teachings of Zen and Christianity are inspired by her trust that, in due time, the bird will return to replenish the nest with foreign yet strangely familiar fruits.

I met my wife, Naomi, a few months after first moving to Japan in 1990, and she has been my daily source of sustenance—emotional as well as culinary—ever since. Naomi has not only passively endured but indeed actively enabled my long absences for monastic as well as academic reasons. Two episodes tell the story. About six months after we starting dating, I suddenly showed up at the office building where she worked, basically to beg her for money. Granted, I needed the dough for a noble purpose: to buy a train ticket to get to a Zen monastery and to make a donation to cover a month of training there. Nevertheless, I don’t think this beggar boy managed to impress her upwardly mobile co-workers as a real catch of a boyfriend. And yet she stuck with me. Many years later, in 2006, with our two-and-a-half-year-old son Toshi in tow and our baby daughter Koto still in her belly, Naomi got left with her parents in Osaka while I spent the summer training at the monastery of Shōkokuji. And still she stuck with me. Before and after that, she has held down the fort on innumerable such occasions. When I was considering whether to take on the project that led to this book, it was Naomi who reminded me not only of Kobayashi Rōshi’s support but also of Tanaka Rōshi’s wish that I would help convey the spirit as well as teachings of Rinzai Zen to the wider world. While I am far from fulfilling his wish, I promise to continue along this path, and I hope that this book will serve others as a set of trail markers.