Preface: Some Words about Words

What Does “Systemic Racism” Mean?

Fair question for a book on the topic. My short answer (a longer answer is this book itself, to be not quite facetious) stems from the fact that every social system (often defined by national boundaries, as in “the American system”) is made up of separate but interlinked and interdependent institutions, both public and private, that are designed to meet one or more needs of the public; the most important include education, business enterprises and employment, government at all levels, healthcare, the legal system (including policing, courts, and imprisonment), and even religion. Each of these institutions, from their inception in colonial times (and modeled, with adaptations, on the English institutions the colonists brought with them) was established, maintained, and perpetuated by White men, who have never constituted a majority of the American population; as of January 2021, non-Hispanic White males numbered 102 million in a total population of 330 million, less than one-third. White men, of course, had completely dominated the parallel institutions in England, and the colonists had no thoughts of relinquishing their control of power; it hardly entered their minds. One institution, however, prompted the White men who controlled colonial governments to codify in law their complete control of an important form of “property” on which the colonial economy relied, especially in the agricultural South: Black slaves who could, as the Supreme Court later ruled, be “bought and sold as an ordinary article of merchandise.” Every social and political institution in colonial America either excluded Blacks entirely, or subjected them to discrimination in the allocation of benefits such as education, without which Blacks could never escape poverty. Barring the education of Blacks by law, as most southern states did, was the paradigm of systemic racism, continuing with inferior Jim Crow schooling, exclusion from jobs requiring verbal and numerical skills, and consignment for many

to lives in decaying inner-city ghettos, with “law and order” enforced by often racist police, prosecutors, and judges. This virtual millstone around the necks of generations of Black Americans has made the effects of systemic racism a continuing national crisis.

Even the adoption of a Constitution and Bill of Rights designed to govern “We, the people of the United States” did not change any of the institutions that excluded or discriminated against Blacks (and White women). And not even the end of slavery and promises in the Reconstruction constitutional amendments of “equal protection under the law” elevated Blacks to the legal or social status of Whites, as victims of a social system and its component institutions that rewarded Whites and punished Blacks for their skin color alone.

Social institutions, of course, are not “real” in any material sense. They are composed of individuals who set their policies and practices, and others who implement them. Over time, as individuals come and go (through death or retirement), and as social and political movements arise in response to factors such as immigration, technology, and economic upheaval, the goals of institutions change. But long-established and entrenched policies and practices remain, particularly at lower levels of decision-making, in which racial bias, both implicit and explicit, is common (and often unremarked) in dealings with customers, clients, and students. The many studies that have documented the discriminatory effect of these biases rebut the claims that shift blame to “a few bad apples” (such as racist cops) who violate the professed “color-blind” policies of their institutions. But the “bad apples” are in fact the poisoned fruit of institutions that fail to recognize the racism at their intertwined roots and whose institutional cultures (like the “blue wall of silence” that protects racist cops from exposure and discipline) are slow to change, even as the broader society responds to the demands of racial and ethnic minorities for equal status with the shrinking White majority. Growing in size and strength since the 1950s, the civil rights movement launched legal and political attacks on school segregation and racist denials of voting rights that forced most institutions to shift from exclusion to inclusion of Blacks and other minorities, at least as official policy.

But the damage inflicted on Blacks by these institutions, and the social system as a whole, had already been done. Despite the good intentions of reformers, systemic racism had placed Blacks well behind Whites in measures such as education, employment, life expectancy, and access to healthcare. Redressing those disparities will require, in my opinion, a multigenerational effort to “root out systemic racism” in all public and private institutions, as

President Joe Biden has stated as a primary goal of his administration. As this book recounts, the grip of “White men’s law” on Black Americans has persisted over four centuries and will be difficult to dislodge. This challenge was well-expressed in 2018 by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, an institution that has pledged to combat racism in all its forms: “Today’s continuing inequities in education, housing, employment, wealth and representation in leadership positions are rooted in our country’s shameful history of slavery and systemic racism.” But with Americans now bitterly divided over issues of racial justice, systemic racism will continue to disadvantage those who were once legally designated the “property” of White men. To be blunt, the cold hands of dead White men still maintain, through the laws and institutions they created and perpetuated, their grip on power and their legacy of White supremacy, however much disavowed by today’s vote-seeking politicians. To deny the persistent reality of systemic racism, as traced in this book over four centuries of American history, makes the deniers part of the problem, not of its long-term solution.

Who Is “White” and Who Is “Black”?

Every author who addresses racial issues faces (but most often ignores or evades) the question of terminology. If I use the terms “White” and “Black” as racial categories, some readers may assume that I’m talking about two discrete, and identifiable, “races,” based on the skin color of their members. Most authors use those terms for convenience, as I will, but few notify their readers that there is no such thing as a “White” or a “Black” race.

Most people know that racial categories are not totally discrete. And some recognize that such categories are socially constructed, acknowledging the obvious overlap between races, such as mixed-race people, but allowing people (particularly in filling out census forms) to identify themselves as “one-race” persons. For example, in the 2010 U.S. census, 97.1 percent of respondents checked the “one race” box. The census found that 72.4 percent of respondents claimed to be only White, 12.6 percent identified as Black, 4.8 percent as Asian, 0.9 percent as Native American or Alaskan Native, and 0.2 percent as Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. In addition, 6.2 percent checked “Other,” with no indication of what “other” race they might be. That leaves 2.9 percent (roughly one out of thirty-three respondents) who identify as “two or more” races, or mixed-race.

But there are at least two problems with these numbers. One is that most of those who identify as mixed-race base that on going back just one or two

generations, that is, to their parents or grandparents, with more than one race among them. However, studies by geneticists, going back many more generations, show that some 6.9 percent of Americans are mixed-race, although 61 percent identify as one-race on census forms. Another study showed that 12 percent of Whites in South Carolina and Louisiana had African ancestry, and that 23 percent of Blacks in those states had White ancestry, obvious consequences of either consensual or forced sex between Whites and Blacks.

In fact, going back nine generations, or roughly two hundred years, gives each of us 512 direct ancestors. Studies show that the average White American has at least one Black ancestor among these 512, and at least one Native American. Dig the generational tree to its roots, of course, and we are all “out of Africa.” The point of these numbers is that virtually every American is technically mixed-race, even those who proudly call themselves “pure” White. Actually, although I’m designated as White, my skin is brown and so is yours, in varying hues from light to dark, with no agreed-upon midpoint to separate races. So why use terms that don’t actually describe our skin colors, none of which is “pure” white or black? Those who adopted them, some four centuries ago, were “White,” the color they associated with virtue, purity, innocence, while “Black” warned of danger, impurity, depravity—terms much preferred by racists rather than, say, “lighter” or “darker” people. And much easier for them to portray dark-skin people as completely lacking in the qualities associated with Whiteness. Racism, in fact, requires this binary division to avoid “pollution” and “mongrelization,” terms often flung by race-baiting politicians of the Jim Crow era (and even beyond). But, to repeat, the colors black and white do not match anyone’s skin color.

A second problem with terminology is that the terms “White” and “Black” to denote racial categories were first used in the late seventeenth century, with the racialization of slavery, to distinguish White slave owners from their Black chattel property. Before that time, hardly anyone considered it necessary to describe differences between people by skin color. After that time, especially in drafting laws governing owner-slave relations, these racial terms became important in ensuring the complete distinction between races, a necessary distinction for slavery’s defenders.

Most racially prejudiced people, I’m sure, have no interest in studies by physical anthropologists and geneticists. But these scientists show that lightskin (read “White”) people emerged only some eight thousand years ago, just a drop in the bucket of the emergence of modern humans of the species Homo sapiens, roughly 350,000 years ago in Africa. In other words, there have been “White” people for only a bit more than 2 percent of the entire time our

species has been around; for 98 percent of that time, all humans had dark skin of various shades. I’m not a geneticist, so I won’t delve into the very few genes, out of the roughly twenty thousand we each have, that determine skin color, except to note that geneticists have identified two (SLC24A5 and SLC45A2) that play major roles. These genes, which decrease production of the darkskin pigment melanin, mutated as people from the Central Asian steppes migrated to northern Europe and Scandinavia. The light-skin genes help to maximize vitamin D synthesis; those migrants didn’t get enough ultraviolet radiation-A (UVA, which comes from the sun) to do that, so natural selection over many generations favored those northerners with light skin, and also favored lactose tolerance (which darker-skin people had less of) to digest the sugar and vitamin D in milk, which is essential for strong bones.

So, in the end, our “race” depends largely on how close our ancestors lived to the equator: those closer to that line got more UVA, and those farther from it made up for getting less UVA by developing lactose tolerance to benefit from the vitamin D in milk. That’s a pretty thin reed with which to construct an ideology of “White supremacy” and to justify the kidnapping and enslavement of darker-skin people through force of arms. But that’s what happened, all because of a handful of genes that determine visible attributes such as skin and eye color, hair texture, and facial features, and despite the fact that White people share 99.9 percent of their genes with Black people and those of other socially constructed races. Unfortunately, privileged White men have seized on that handful of genes to develop an ideology and create institutions whose tragic consequences in racial violence and inequality have prompted this book.

As an addendum, let me note that, just as there are no “Black” or “White” races, the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” do not denote a “racial” group. In fact, members of this group in Mexico and Central and South America have a wide range of skin color, from very light to very dark, a consequence of sexual mingling between White Europeans, Black Africans brought to South America and the Caribbean as slaves, and indigenous people: Aztecs, Maya, Incas, and Amazonians. In Brazil and Cuba, to which many more slaves were imported than to the United States, many residents are distinctively black in skin color. And many in Argentina and Chile, to which many Germans emigrated, are blond and have fair skin. This book does not primarily focus on Hispanics, but prejudice against them is obviously based on their “brown” skin color as much as language and culture, which vary widely. But whether White, Black, or “other,” Hispanics in the United States encounter prejudice and discrimination, and the resultant inequality, as a direct consequence of

the need of many White Americans to reserve racial supremacy and “purity” for themselves. Skin color has long been the defining characteristic by which most people view themselves and others. There would be no need for this book if it were not. But sadly, it still is.

What about the “N-Word”?

The news has recently been filled with articles about journalists, professors, and commentators whose use of what we today refer to as “the N-word” has been called into question. Many of these episodes revolve around issues of authorial agency, of impact and sensibility, and of the different contexts in which that word lands when spoken and written.

I’d like therefore to explain my approach to the use of the word, reproducing it in full in several chapters of this book. Everyone, of course, knows what that word is and what it has meant historically, as a hateful slur on Black people. But that is where agreement ends and where those who agree on its history sometimes disagree on its usage today. For instance, is it any less hateful and hurtful if it’s used in a book, in quotations from people—including Black people—who have used it at some time, even in the distant past? Or is historical exactitude—and insistence on reproducing the historical record exactly as it exists—a sufficient reason to include it as spoken or written when it lands even in this context—and perhaps especially in this context—so harshly to contemporary ears? Should the word be referenced or elided (e.g., “N-word” or “n-----”) since, after all, the reference will be clear to everyone?

That word appears in this book, especially in chapter 2, most frequently in transcripts of interviews of formerly enslaved people recorded in the 1930s, people then in their eighties and nineties. The agency that conducted these interviews—some 2,300—was the Federal Writers Project, the New Deal agency designed to give employment to jobless writers, artists, photographers, and historians. The collection of what was called the Slave Narratives was followed by transcribing the tapes for publication by the Library of Congress. Most of these transcriptions were done by White people, with instructions to replicate as closely as possible the vernacular and pronunciation of the subjects, many of them illiterate and unschooled. This effort at verisimilitude produced results that may strike many people today as offensive and patronizing, but to put them into standard English would, it seems to me, greatly alter and diminish the voices of people who were never schooled in standard English and would be a presumptuous act on my part. Most of the former slaves refer in their interviews to themselves and other Blacks as

“niggers,” long before terms such as “people of color” or “African Americans” became standard and preferred. As Harvard Law professor Randall Kennedy shows in his 2002 book, Nigger: The Strange Career of a Troublesome Word, although slaves used the word among themselves, by the 1840s it had become a pejorative slur by racist Whites about, or even to, Blacks. I don’t believe it’s my role as historian to reduce the impact of the word through euphemism or elision; this would in my opinion be to reach back into history and in effect edit the words of these historical figures to fit contemporary usage. Furthermore, it would almost certainly diminish the pain—palpable, acute—that emerges from these stories, which is one of the features that makes them so irreplaceable as testament and history.

A Word of Introduction

I suspect many readers of books like this would like to know more about the authors than book-jacket lists of degrees and academic positions. For such readers of this book, a few words of introduction about who I am and why I felt compelled to write this book.

For those who don’t already know me, I am a privileged White male, born in 1940 and raised in upper-middle-class, virtually all-White, mostly Protestant, and staunchly Republican towns across the county, as my father’s work as a nuclear engineer took our family from Massachusetts to Washington state, with my high school years in a country club Cincinnati suburb. My family tree includes a Mayflower pilgrim, William White, and his son Peregrine, born on the ship in Plymouth Harbor; on another branch, I share a long-ago English grandfather with Abraham Lincoln. My education includes a Ph.D. in political science from Boston University and a J.D. from Harvard Law School; I’m also a member of the U.S. Supreme Court bar. I taught constitutional law at the University of California, San Diego, from 1982 until my retirement in 2004. Along the way, I’ve written a dozen books on the Supreme Court and constitutional litigation, some winning prestigious awards. All told, that’s about as privileged and credentialed as you can get and has given me an insider’s vantage point near the top of both the legal and educational institutions, with decades of experience in how they operate to perpetuate White male privilege. (Perhaps that’s why I focus on these two social institutions and their interaction in establishing and maintaining systemic racism.)

With this background and credentials, I could well have turned out like the people I grew up and went to school with: conservative, Republican, and

also racist. The most common terms my high school classmates used to describe Blacks were “jigaboos” and “jungle bunnies,” which always provoked derisive laughter. That’s not just stupid teenage behavior but a reflection of the thoughtless racism that permeated our privileged White culture.

But I didn’t turn out like my classmates. Instead, I have long been an outsider, a civil rights and antiwar activist, a democratic socialist, and a critic of incursions on the constitutional rights of all Americans. Three factors, I think, contributed to my apostacy. First, I got from my dad a reverence for facts and a critical (in the best sense) and skeptical attitude toward supposed authority and orthodoxy of all kinds, and from my mom (an accomplished poet) a love of words and the impact they can have on how people think of themselves and others. And from both of them, a rejection of racism in any form. Second, my six younger siblings and I were raised in the Unitarian (now UnitarianUniversalist) Church, which values tolerance, inclusiveness, and engagement in society; my favorite Sunday school teacher was a wonderful Black woman who took us to Black churches in Cincinnati to experience their exuberant gospel music and prophetic message of the hard but rewarding journey to the Promised Land.

Third, and perhaps most important, was my choice of Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, then and now a bastion of progressive (radical, in fact) politics and cultural nonconformity. Founded by abolitionists in the 1850s, Antioch was only the second college (after its Ohio neighbor, Oberlin) to admit Blacks, in 1853. Its first president was the noted educator and former abolitionist congressman Horace Mann. On my first day at Antioch, in 1958, I toured the campus and stopped at a marble obelisk that honors Mann; carved into its base is a sentence from his final commencement speech, weeks before his death in 1859: “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” That is Antioch’s motto, and I adopted it for my own.

Early at Antioch, I joined the campus branch of the Youth NAACP, headed by a charismatic Black student, Eleanor Holmes, a mentor and inspiration (now the long-time D.C. delegate in Congress), who led a contingent of Antiochians to my first demonstration in Washington, a youth march for integrated schools on the fifth anniversary of the Brown case in May 1959. The next year, working at a cooperative-education job in D.C., one of my coworkers, Henry “Hank” Thomas, invited me to join the Howard University chapter of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, known as “Snick”). I joined in picketing segregated theaters and restaurants in the Maryland and Virginia suburbs; my first arrest and night in jail was from a “bowl-in” at a Whites-only bowling alley in Maryland. (Hank later

joined the Freedom Rides to integrate buses and terminal facilities in the Deep South; his bus was set afire by racists outside of Anniston, Alabama, a Klan stronghold, and Hank was bashed in the head with a baseball bat as he escaped the flames; a photo of that assault, with Hank covered in blood, was on the front page of newspapers and magazines covers across the country.)

Most important was my trip with Hank and other Howard students in October 1960 to Snick’s first national conference at historically Black Morehouse College in Atlanta, at which Snick activist John Lewis outlined a strategy of sit-ins across the country to break lunch-counter segregation. But I was most impressed, and spurred to action, by Rev. James Lawson, a young Methodist minister who had been expelled from Vanderbilt University’s seminary for leading sit-ins in Nashville, and who had earlier served a twoyear federal prison sentence for refusing military service as a pacifist. At the Morehouse conference, Lawson implored us to break all our ties to a government that practiced and condoned Jim Crow segregation; shortly after returning to Washington, I sent my draft card back to my local board in Cincinnati, with a letter explaining why I would refuse induction as a pacifist and civil rights activist. Back at Antioch, I wrote and circulated antidraft pamphlets on midwest campuses, earning a visit from FBI agents who threatened me with arrest for sedition but never returned. I was finally ordered to report for induction in 1964, as American troops began flooding into Vietnam; after I refused to report, I was indicted by a federal grand jury in Cincinnati and tried in 1965 before a very hostile federal judge, who found me guilty and imposed a three-year sentence. (I later learned he had a son serving in Vietnam.)

After losing an appeal on a two-to-one vote, and advised that a Supreme Court review would be futile, I began serving my sentence in 1966 at a federal prison in Michigan; I was later transferred to the prison in Danbury, Connecticut, where I got to know Mafia bosses, Black Muslims, and crooked politicians. While at Danbury, a friend sent me several books by Howard Zinn, the radical historian and political scientist at Boston University; Howard and I began a correspondence that led to my graduate work at BU right after my release in 1969, with Howard as mentor and close friend. After I completed my Ph.D. in 1973, Howard arranged a job for me as a researcher with the lawyers defending Daniel Ellsberg in the Pentagon Papers case. (The charges were later dropped due to governmental misconduct.) I found this legal work fascinating, and in 1974 I applied to Harvard Law School, although I feared my felony conviction would lead to quick rejection. But Harvard was then boiling with antiwar activism and surprised me with a seat in the Law School’s

hallowed halls. Spurning the corporate-law and tax courses my classmates endured as tickets to eventual partnerships in Big-Law firms, I took all the constitutional law and legal history courses Harvard offered. While still in law school, I obtained (through the Freedom of Information Act) my FBI and draft board records, discovering that I had been drafted a year earlier than regulations permitted, as punishment for my antidraft organizing. Searching the Law School library, I found an obscure and rarely used provision of federal law (called a Writ of Error Coram Nobis) that allows former inmates to challenge their convictions with newly discovered evidence of governmental misconduct. I drafted a brief petition, attached the incriminating documents, and sent it to the federal court in Cincinnati. Much to my surprise, the U.S. attorney agreed I had been unlawfully charged, and a judge vacated my conviction; I was later granted a full pardon by President Gerald Ford, restoring my rights to vote and practice law, making me probably the only ex-convict member of the Supreme Court bar. I like to joke that I’ve been on both sides of the bars in prisons and courtrooms, but those experiences have given me insight that few others have into the systemic racism that both institutions still reflect and grapple with. And these experiences—as both an insider and an outsider in American society—have spurred me to devote much of my academic work and political activism to issues of race and inequality.

As a lawyer, I used the coram nobis writ in the 1980s to initiate the successful efforts to vacate the World War II criminal convictions of Fred Korematsu and Gordon Hirabayashi for violating military curfew and internment orders, convictions upheld by the Supreme Court in widely denounced opinions. During research for a book on their cases, I uncovered records showing that government lawyers had knowingly lied to the Court about the dangers of sabotage and espionage posed by Japanese Americans on the West Coast; this was evidence of egregious governmental misconduct. Aided by some thirty young lawyers and law students, most of them children or grandchildren of Japanese Americans imprisoned in concentration camps (120,000 in all, two-thirds of them native-born citizens), I was honored to represent Fred and Gordon in their long quest for vindication, culminating with both men receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian award. Sitting in the East Room of the White House while President Bill Clinton placed the medal around Fred’s neck, linking him to Rosa Parks and Homer Plessy as civil rights pioneers, was moving and immensely gratifying to me.

Let me close this introduction—in this time of a deadly global pandemic— with another admonition that inspires me, from the legendary labor organizer

Preface

of a century ago, Mary Harris “Mother” Jones: “Pray for the dead, and fight like hell for the living.”

I hope this brief account of my experiences gives readers a sense of who I am and why I felt compelled to write this book, which I view as a vicarious conversation with you, asking questions and pointing to sources from which you can learn more about the history and impact of systemic racism and persistent inequality in American society. And thanks for joining me in this conversation.

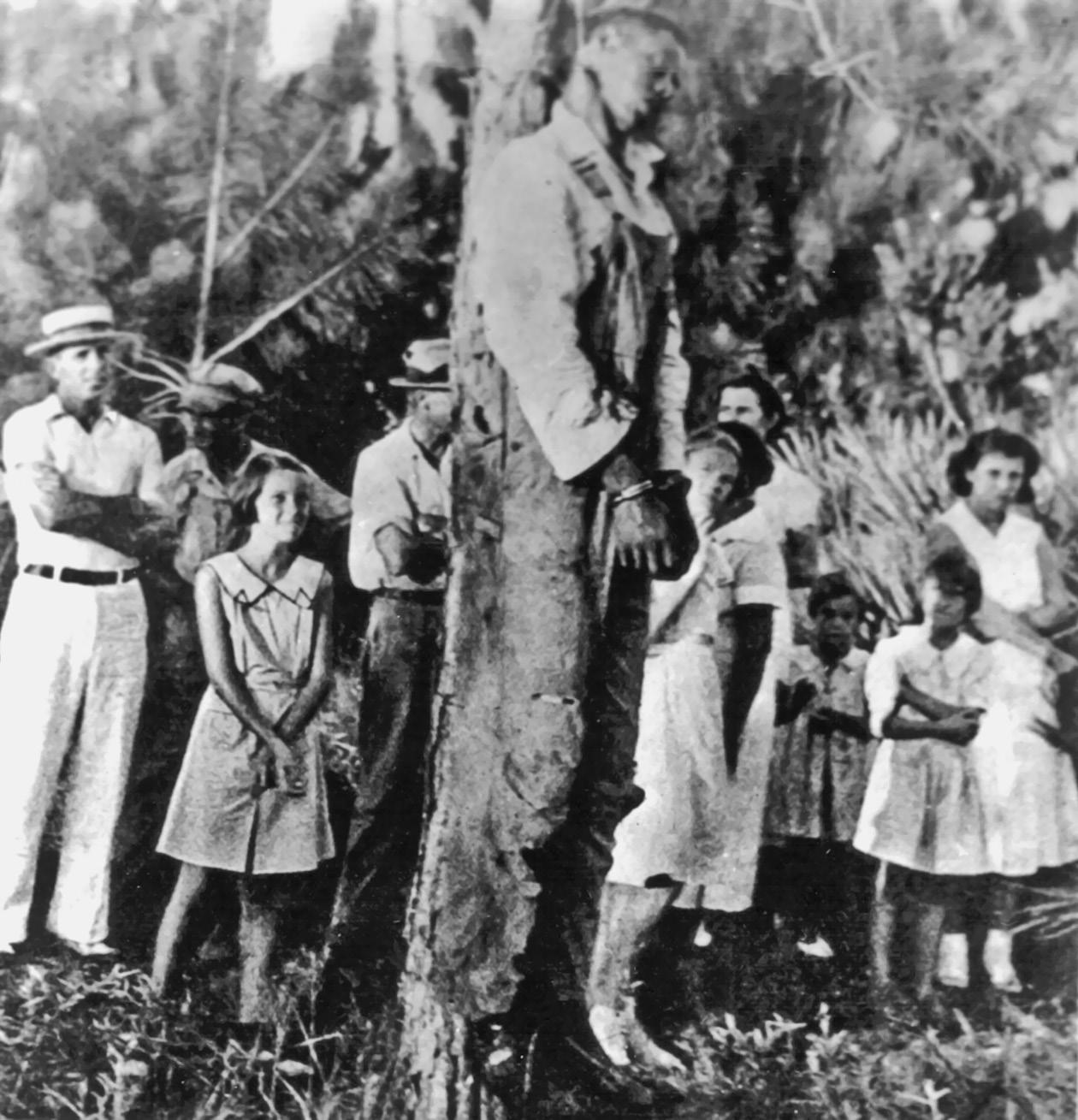

Fort Lauderdale, Florida, July 19, 1935

Prologue

“They’ve Got Him!”

Friday, July 19, 1935, was a typically hot, muggy summer day in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Decades before the Atlantic Coast city became a thriving metropolis—its white beaches and inlets luring 13 million visitors each year, docking forty-five thousand boats, the third-largest cruise ship port in the world, the seat of surrounding Broward County, with a combined population just under 2 million—Fort Lauderdale in 1935 was a town of some twelve thousand residents, with extensive citrus groves and vegetable farms in the western section, stretching through the county to the wetlands and swamps of the Everglades.

That Friday, a young woman was in the front yard of her home on Las Olas Boulevard, then a dirt road and now the main tourist drag of Fort Lauderdale, running inland from the beachfront to the city’s western edge. Her husband was also out, mowing the lawn. The town had been buzzing since Tuesday with rapidly spreading rumors that a Black man had raped a White woman, who escaped after her screams brought neighbors rushing to her aid. Summoned by the Broward County sheriff, Walter Clark, a posse of one hundred men had been conducting a manhunt since then. Clark was elected sheriff in 1931 at the age of twenty-seven. By 1935 he had already become notorious among the county’s small Black population as a virulent racist, demanding that Blacks stand up when he entered a room; one who didn’t was arrested and found dead in his cell the next morning, supposedly having “fallen out of [the] bunk and hit his head.” Clark also reportedly shot and killed a Black man who urinated within sight of an affronted White woman; the sheriff’s younger brother and chief deputy, Robert, was widely known to have shot and killed a Black woman who spit on him during an argument. Confined to

an area known as “Short Third,” Blacks in Fort Lauderdale seldom ventured into White neighborhoods except to work, many as farm laborers and fruit pickers, and kept “in their place” around Whites, adopting the southern mores of servility and deference.

Newspaper reports of the alleged assault on Tuesday, although making no mention of a rape, completed or attempted, further inflamed the public as the manhunt spread throughout the county. On Thursday, July 18, the Sarasota Herald Tribune, under the headline “Woman Beats Off Assailant,” ran a large photo of a woman sitting on a porch, her hands wrapped in white cloth, one arm around a small boy. Under the photo, two sentences explained the scene: “Accosted by an unidentified Negro who attempted to assault her, Mrs. J. L. Jones of Fort Lauderdale, Fla. put him to route [sic] by her struggling and screaming—but not until he had slashed her hands with a knife. She is shown after the attack with her 5-year-old son Jimmie who kept his wits and ran for help.” Any attack by a Black man on a White woman, of course, was bound to produce cries for extreme punishment.

The young woman in her front yard on Las Olas Boulevard, watching a cloud of dust approach her home, soon made out a car in which she recognized Chief Deputy Sheriff Bob Clark. In the back seat she saw a Black man sitting between two White men. Clark’s car was followed by several others and a uniformed officer on a three-wheeled motorcycle, which slowed down in front of the young woman’s house, the officer shouting, “They’ve got him!” Assuming he meant the reported and sought-after rapist, she grabbed her husband, and they jumped in their car, joining the procession as Clark’s car turned onto Old Davie Road, pulling up at its intersection with Southwest 31st Street, into a clearing with a pine tree near the center. The site for what followed had been picked in advance; it lay just behind the back yard of the home of Marion Jones, the alleged victim of an assault by a Black man. As the rest of the caravan arrived, with White men spilling out of cars, some carrying pistols and rifles, the young woman saw Deputy Clark lead a young Black man, his hands cuffed in front, dressed in denim overalls and a white, long-sleeved shirt, from the car toward the tree.

Fifty years later, in 1985, that young woman, now in her seventies and speaking anonymously, recounted what she had seen that Friday to Bryan Brooks, a writer for the Fort Lauderdale Sun Sentinel, who researched and wrote a fifty-years-after feature on what happened to that young Black man. Her story is the only first-person account—then or since—by anyone at the scene that day, told with the graphic details that people who have witnessed some horrific event can often recall many years later, indelibly impressed into

their memories. She told Brooks that Deputy Clark turned his prisoner over to a member of the crowd, by then a couple dozen, then walked into the back yard of the Jones house, returning with a length of clothesline. Shouting, “You black son of a bitch!,” he wrapped one end around the prisoner’s neck, tying it tightly under his jaw, then tossed the other end over a tree limb about ten feet above the ground. The Black man, knowing his fate, said nothing and did not resist. Clark then pulled the rope until the man’s neck snapped, his head lolling to the left, his body dangling about a foot off the ground.

The lynching—for everyone there knew what they had witnessed—was over, but Clark was not done. Pulling his pistol from its holster, he fired a round into the victim’s body, followed by shots from mob members who had brought their own guns. Clark handed his gun to several people—including the woman who later spoke with Brooks—who also took shots, some missing and spraying pine bark, but most hitting their mark, the swaying body shuddering with each impact. Clark made it clear to the shooters that they were now accomplices to the lynching and had good reason to deny having taken part in it, or even being at the scene, in case an investigation ensued.

Word of the lynching quickly spread, drawing more than a hundred spectators, many of them families with small children. A local reporter, toting a camera, also arrived and took photos of the crowd and of those standing within a few feet of the hanging body. The woman who spoke with Brooks identified herself in one of those photos. Included in the photo were several children, among them a blonde girl of about seven, in a white dress, her hands clasped in front, perhaps in unconscious imitation of the cuffed body, gazing at it with an enigmatic smile on her face.

Deputy Clark left the body hanging for more than three hours, while a steady stream of spectators filed by the tree. Some cut swatches from the Black man’s overalls, pieces of the hanging cord, even chunks of pine bark as souvenirs. The body remained hanging until about 7:30 p.m., when George Benton, the county’s only Black undertaker and part-time coroner, arrived with his hearse. Deputy Clark cut the cord, letting the body drop into a heap. (Benton’s son later told Brooks that Sheriff Clark once pulled up at the mortuary with the body of a Black man strapped across his car’s hood, like a ten-point buck. Dropping the body to the ground, the sheriff had said, “Here’s another dead nigger for you, George,” then sped off.) Peeling the blood-stained clothing from the latest dead Black man, Benton counted seventeen bullet holes in the body, which was soon buried in an unmarked grave in the town’s Black cemetery. His coroner’s report listed the cause of death as

“broken neck or bullet wounds.” The death certificate filed with the county identified the deceased man as Rubin Stacy.

* * *

The aftermath and impact of Rubin Stacy’s lynching was brief and frustrating. South Florida newspapers ran editorials condemning the bypass of the legal system in which Stacy would undoubtedly have been convicted of aggravated assault or attempted rape and sent to the state penitentiary for perhaps twenty years or even life imprisonment. But the editorial tut-tutting also painted him as a vicious criminal, attacking an innocent White woman in front of her three children, grabbing her around the neck and slashing her hands and arms with a pen knife when she fought back, screaming for help as Stacy threw her to the ground in the yard, running off into the surrounding woods and wetlands.

Responding to these editorials and calls to his office in Tallahassee from church leaders and antilynching advocates, Florida’s governor Dave Scholtz promised a thorough and honest investigation. He instructed Louis F. Marie, the Broward County state’s attorney, to convene a grand jury, which he did just three days after the lynching. Needless to say, all its members were White men from the county’s business community, hand-picked by Marie, as were almost all southern juries for decades before and since. Sheriff Walter Clark pledged his full cooperation with the inquest. Marie called twenty-nine witnesses, including Clark and his brother the chief deputy. The Clarks both testified that Stacy had been apprehended about twenty miles north of Fort Lauderdale, after a passing trucker reported spotting a “suspicious looking” Black man ducking behind some roadside bushes, and that a police officer and two citizens had detained him after a chase that ended with shots fired at the suspect.

Sheriff Clark testified he had then taken Stacy to the home of Marion Jones, the woman who claimed she had been assaulted and slashed with a knife. A thirty-year-old housewife, she and her husband, James Lee Jones, lived in a comfortable home next door to Marion’s parents, William and Catherine Hill, who owned and operated a surrounding truck and fruit farm. James, who was not home during the alleged attack, had a steady job as a lumber handler and planer at Gate City Sash and Door, one of the city’s leading businesses. The Joneses’ three children— Catherine was nine, Lorraine was seven, and James Lee “Jimmie” Jr. was five—had been home and raised cries for help as the assailant fled. Sheriff Clark testified that when he brought the

suspect to the Joneses’ door, Jimmie shouted, “That’s the man, for sure,” as the children ran from the room in fear.

Stacy, of course, could not contest what Sheriff Clark told the grand jurors or present anyone who could defend him. And there is no record of anything Stacy may have said during any “interrogation” by Clark or his deputies. Accounts did circulate, however, that he had admitted to police officers that he had, in fact, knocked on the Joneses’ kitchen door to ask for a glass of water on that hot day. Marion Jones confirmed this request. But Stacy apparently said that the woman, with three young children at home, had panicked seeing a strange Black man at her door and began screaming, scaring him into running away. He denied threatening or slashing her with a knife. Asked by an officer why he had run to avoid arrest after being spotted by the truck driver, he replied, “Well, I just can’t stand it. You know how Negroes are. They just can’t stand for anyone to chase them.”

Sheriff Clark further testified that after he took the suspect to the small Broward County jail, he started hearing of plans to form a lynch mob. Concerned about the prisoner’s safety, Clark said, he consulted a local judge, who advised him to take the suspect to the larger jail in Miami, some twentyfive miles south of Fort Lauderdale. Assisted by several deputies, Clark went on, he loaded the Black man into a police car and set off for Miami. However, they encountered a roadblock of more than a dozen cars. Trying to get past them, Clark’s vehicle was forced off the road into a ditch, where masked men seized the handcuffed Black man and sped away. By the time Clark and his deputies reached the clearing on Old Davie Road, he testified, the lynching was over and the masked men had disappeared, leaving the scene to the growing crowd of spectators.

Not surprisingly, not a single witness before the hastily convened grand jury could identify any member of the lynch mob, although the faces of several men who had been there were clear in the photos taken by the newspaper reporter at the scene. Two days later, on July 24, the grand jurors announced they had found “no true bill” of indictment against anyone, concluding that Rubin Stacy had died “at the hands of a person or persons unknown,” a common phrase in reports of inquests into lynchings that found no one culpable.

Quite obviously, Sheriff Clark’s account to the grand jurors was very different—and self-exculpatory—from the account told to Bryan Brooks by an eyewitness, who had no reason to fabricate, even admitting her participation by firing a bullet into Stacy’s body. She, of course, would have no knowledge of what Clark and his deputies had done before she and her husband