1 Introduction

AlQaeda, the world’s most dangerous terrorist organization, was founded in August 1988 at a meeting that Osama Bin Laden convened in his house in Peshawar, Pakistan. (Al Qaeda did not start in Saudi Arabia, as is often thought.) He wanted to create a rapid deployment force of experienced fighters for the armed jihad, to be commanded by himself and a small cadre of veteran jihadist revolutionaries. The movement that Bin Laden initiated in his sitting room, in exile, ballooned into a global movement of political cadres, public intellectuals and street preachers, military fighter brigades, and webmasters waging online jihad. Decades later, the movement that Bin Laden started is operating on five continents and includes an estimated 100,000 armed fighters in Asia and Africa. The number is based on reporting by the analytical support team of the United Nations Security Council’s ISIL (Da’esh) and Al-Qaida Sanctions Committee, and analyses by independent researchers. A report from 2018 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies estimated the number of active Al Qaeda-aligned fighters to be closer to 250,000, 270% higher than in 2001 at the time of the 9/11 attacks.1 No one really knows precisely how many there are.

This book is about the Western branch organizations in this global movement. Western democracies have been the target and, paradoxically, home base—sometimes, a sanctuary—for the global jihadist movement. Jihadism is fueled by a revulsion against the values and objectives that sustain global growth and openness. Nevertheless, the movement thrives on globalization. Nationalists mourn the erosion of borders caused by globalization. The jihadists see it as an opportunity. They fight not for control of a patch of land. They fight against the system of states.

Al Qaeda and the jihadist movement, broadly defined as the networks and organizations, supporters and propagandists aligned with Al Qaeda or

the Islamic State, is not, of course, only, or even primarily, a Western phenomenon.2 In the 1990s, Osama Bin Laden developed the doctrine of attacking the “far enemy,” the United States and its Western allies, on the assumption that relentless terrorism against American and Western targets would compel the United States to withdraw support from governments in the Muslim world. The strategy anticipates that in consequence, “the near enemy,” the political classes in Muslim majority countries, will be left vulnerable to the religious revolution that the jihadists see as the first step to the creation of a universal reign under God’s law. It is a fantastical belief system. However, it is no more fantastical than revolutionary Marxism, which envisioned a stateless world to be brought into being by the awakening of the global proletariat, and which attracted followers across the world for 150 years. That people hold to fanatical ideologies is not what needs to be explained. The puzzle is how a belief system that kills off its followers at a high rate and is violently inimical not just to Western democracy but to all existing forms of Muslim governments can attract followers among Western Muslims and converts to Islam.

The argument of this book is that the diffusion of jihadist extremism in Western democracies was driven by the strategic objectives of Osama Bin Laden and the global movement he spearheaded rather than, as is often argued, by local grievances of Western Muslims. I use the word “movement” to describe the global jihadist organization, but it is in fact more than a social movement. Social movements are usually are seen as leaderless “fuzzy” communities held together by shared ideas. The global jihadist movement is also held together by ideas, but the global organization has hierarchies and authority structures that create a hard core of control-andcommand. It is these clandestine command structures that make it possible for the global movement to engage in coordinated insurgencies and manage terrorist campaigns across continents, and to do so in the pursuit of a unified strategic project.

An apt term for this sort of very contemporary local-global phenomenon is “glocal,” which the sociologist Anthony Giddens once defined as: “Intensification of world-wide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa.”3 More prosaically, “glocalization” also refers to the adaptation of international products to the local context in which they are sold. Two observations may be made. The first is that glocalization creates infrastructures for risk management and risk avoidance, and for the

allocation of resources, labor, and revenues. The transnational jihadist networks manage all that very efficiently. The other observation is that power in the glocal corporation rests not with the local hubs but with the global management.

Bin Laden, a Saudi millionaire, began his revolutionary career in alliance with Egyptian and Arab Islamist militants. In founding Al Qaeda, his intention was to create a vanguard organization that would topple apostate Muslim regimes. But while the jihadists are utopians, they are also very practical revolutionaries. The extremist networks thrive on the transformations associated with globalization—increased openness of societies, cheap travel, and the ease with which ideas and influences can be disseminated from one region of the globe to another. Western societies provided them with opportunities to broadcast their views, to recruit supporters, to organize, and to move people and money around the world.Without this Western infrastructure, Bin Laden’s project would have fallen apart at an early stage. The jihadist movement is globalist in aspiration and transnational in practice.

In the 1990s, Western hubs of displaced North African and Middle Eastern extremist Islamists became absorbed into the global jihadist movement. Al Qaeda established bases in North America, Europe, and Australia. Over time, as they adapted to local conditions, these Western hubs and networks developed their own styles and vernaculars. But, always, their primary purpose was to recruit for the global movement. Western militants are fitted into the global organization. What they do and how they do it is determined by the bosses’ business plan. Growth came at the cost of a certain loss of control, a familiar problem for any business. Bin Laden’s project is, nevertheless, on its own terms, a success story.

The data used here come from the Western Jihadism Project, a research program I started in 2006 and have continued without interruption since then. The project identified Western residents and citizens who have committed terrorism-related crimes or who died while engaged in an attack or while fighting in an insurgency in the name of Al Qaeda or any of the many groups and organization aligned with Al Qaeda and committed to the global armed jihad

The database includes demographic and biographical information about the thousands of men—5,832 to be precise, and 561 women—who meet the inclusion criteria. We record their contacts with other identified terrorists, and document conspiracies committed by the networks. Twenty countries

are represented in the database. The methods used for collecting the data are described in the Appendix.

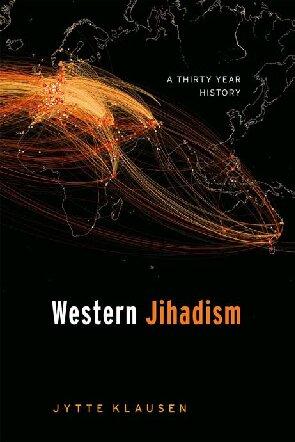

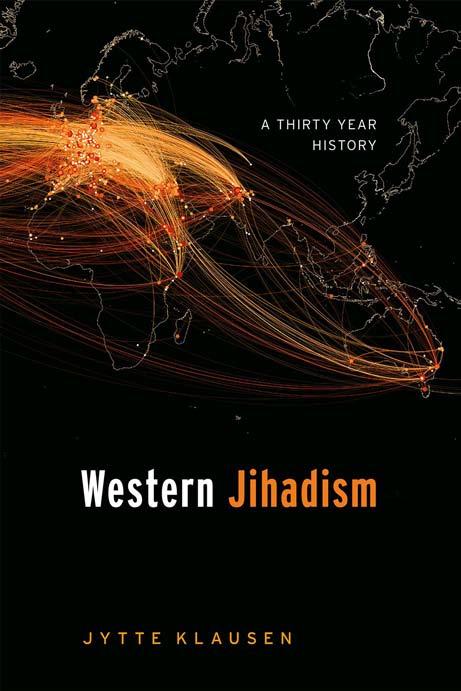

The network map on the cover of this book depicts thirty years of networking by Western jihadists and their bosses in the global jihadist movement. The network lines resemble familiar maps stashed in the pockets of seats on board planes showing the airline’s route net traversing the earth. Here, they represent communications between Western militants and their opposite numbers in the network. The map shows the travel from their hometowns in the pursuit of terrorism-related activities, and it charts their communications with other actors in terrorist networks. Each dot and line reflects a data point derived from public information gathered by my teams of student researchers and manually entered into a digitally-managed database. It took fifteen years and the work of eighty students.

Analytically, the militants and their organizations are treated as a connecting point in the network (nodes). The dots pinned on the map mark the militants’ residencies and the geographical locations in which they engaged in terrorist activities or the location of their contacts. Each line (edge) between the nodes in the network represents communications for purposes of conspiracy, acts of terrorism, and other actions or communications associated with terrorism-related crimes revealed in public records.

A total of 44,500 edges representing links between the actors and entities were used in the generation of the network graphic. The cover graphic vividly illustrates how Western-based militants integrated with the global jihadist movement, and connected with its training camps in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and with jihadist insurgencies from Somalia to Syria.

The dense mass of connected dots linking the nodes in North America, Western Europe and Australia provides a summary visual representation of the transnational social organization of Western jihadism uncovered by the research project. The map shows how widely dispersed the cells, organizations, and individuals are across the Western world from Alaska and the U.S. West Coast to Asia and on to Australia, and how closely they are interrelated. It may be assumed that the map captures just the visible tip of the metaphorical iceberg. Those depicted here are only the publicly-known networked communications that we have been able to document from the public records available to us through court documents and media reports. Whatever lies below, we do not and cannot know.

Al Qaeda in the 1990s was like a start-up. It failed and then failed again. But it had a formula for starting up once more. Operating both in jihadist

heartlands and in the West, the movement has spread through a process that I will describe as networked contagion. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a cadre of North African and Arab Islamist militants escaped to Europe and North America following failed attempts at revolution at home. From their bases in New York, London, Milan, Madrid, and a handful of other cities, they helped Osama Bin Laden staff Al Qaeda and provided logistical support and manpower so that Bin Laden could strike at the West. The bold attack on the United States on September 11, 2001, was a crowning achievement for Bin Laden’s organization.

Bin Laden was not a theorist of revolution, or a religious scholar. He was a political entrepreneur. His singular accomplishment was to give extremist Islamism a new strategic direction by focusing on a war against the “far enemy,” the United States and its Western allies. Global terrorism was the tactic, but for that he needed Western adherents who could man clandestine transnational networks and use their passports to travel far and wide. His special talent was the ability to translate theory into action. He saw early on that new communications technologies made it possible for his organization to coordinate globally and exploit gaps in surveillance.

For many years, few people in the West understood the true nature of the extremist Islamist ideology that motivated many jihadist refugees. In any case, it was assumed that they would do as most exiled expatriates do— blend in, be grateful for having been granted refuge, and direct their anger against their home countries.

There were well-trodden pathways of migration from former colonies to the metropolitan centers of the former colonial powers and to New York City, a favorite destination for generations of migrants. Generous rules for granting residency to political refugees and persecuted religious groups from the Soviet Union and the Eastern bloc countries had been passed in the 1980s. These opened the doors also to religious dissidents from authoritarian Muslim countries.

The first generation of jihadist refugees included some men who became leading figures in the jihad against the West. Omar Abdel-Rahman, an Egyptian cleric, known as the “Blind Sheikh,” led the cell responsible for the 1993 World Trade Center from a perch in Brooklyn. Abu Qatada al- Filistini (meaning “the Palestinian”), whose real name is Omar Mahmoud Mohammad, lived in London for two decades, where he built up a formidable local network and was a nuisance to British authorities until he was deported to Jordan in 2013. Abu Dahdah (alias Emad Eddin Barakat Yarkas)

a Syrian-born militant, ran an Al Qaeda cell in Spain and provided logistical support for the 9/11 hijackers. All were beneficiaries of new rules for granting residency to political refugees and persecuted religious groups. Using their new passports, the militants plotted and organized, and they created a cosmopolitan and global network.

The jihadists thrived on the opening of borders that followed the end of the Cold War. Operatives who had fled or been expelled from their home countries were free to live the lives of post-national cosmopolitans, and to build transnational networks. But the encounter with the West challenged their norms and values, and led them to adopt new ways of doing jihad.

At first, they operated mainly in mosques and prayer rooms. But their message soon spread more widely when the propagandists spoke the local languages: French, German, and always, English, which is the common language among polyglot youths. A cadre of extremist public intellectuals articulated the doctrines to fit the needs of the new audiences. They uploaded long sermons on the internet, sold compact discs online, and marketed their tracts in bookstores. Gradually the preaching incorporated local grievances. As they established a presence online, they reached audiences that were not confined to meeting halls and prayer rooms.

None of this was criminal at the time, and many aspects of these activities are still not criminalized because they are, in essence, the sort of things that many legitimate political and religious groups do: hold meetings, spread the word, and proselytize. Jihadist intellectuals modified their ideas in this encounter with the West. Adapting and rejecting Western political ideas and styles of protest, they developed a remarkably consistent anti-liberal system of thought and populist rhetorical styles that appealed to new followers with little or no knowledge of Islam.

The first time the Western bases rescued Bin Laden’s project was after he was thrown out of Sudan, in 1996. The men who came to his rescue were expatriate militants who had fled the home countries in North Africa and the Middle East in the 1980s and 1990s and who, over a few years, became integrated into networks under Bin Laden’s command.

The second time the Western militants rescued Bin Laden’s project came after Al Qaeda’s near-death experience in December 2001, following the American counterstrike in response to the September 11 attacks. Al Qaeda’s bases in Afghanistan were obliterated, the leadership cadre decimated or driven into exile. The internet, another Western invention, helped the

movement grow back, changing the ways in which the terrorist networks organize their operations and recruit new followers. This time, the rescue took the form of what became known as “homegrown” terrorism.

Some analysts interpreted the Arab Spring uprisings in 2011 that swept Arab countries with a demand for reform and democracy as a repudiation of Al Qaeda’s agenda. Fawaz Gerges, a professor at the London School of Economics, wrote that, “Only a miracle will resuscitate a transnational jihad of the al-Qaeda variety [ ] the Arab Spring represents a fundamental challenge to the very conditions that fuel extremist ideologies.”4 In 2012, Peter Bergen, the author of several books on Bin Laden and a commentator on CNN, declared that Al Qaeda had been “defeated” because of the Arab Spring. He compared Al Qaeda to Blockbuster, a video rental chain that went bust when movie watching went online.5

Skeptics countered that the pro-reform Arab Spring movement was fractured, and that in many places it was coming under the control of the better organized Islamist groups. Two veteran Al Qaeda observers, Bruce Hoffman and Rohan Gunaratna, were among the skeptics.6 Acknowledging that the first generation of Al Qaeda, the so-called “Core,” may be in decline, Al Qaeda has succeeded in expanding its tentacles. Al Qaeda’s tactic, Gunaratna wrote, was to go along with the democratic movements in the short term and win over new recruits.They would then try to take over the local resistance.This was what happened.When the regimes collapsed in Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, and Yemen, the extremists found room to recruit new followers. In Syria and Iraq, civil wars opened doors for a jihadist revival. Democracy, it turned out, was not the antidote to extremism that it was supposed to be. Tunisia is an example of a successful transition from an authoritarian regime to a representative democratic republic after the 2011 Arab Spring revolution. But as Aaron Zelin writes, Tunisians joined the Islamic State in unprecedented numbers and became one of its largest sources of foreign fighters.7

By 2012, Syria had become a destination for old and new militants committed to the jihadist program.The proximity to Europe made this war zone particularly attractive to a new generation of righteous fighters for the cause—and their would-be wives. The movement’s European bases sprang into action again, recruiting and organizing volunteers to fight with Al Qaeda. Some militants opted rather for Al Qaeda’s deviant offspring, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (referred to as Da’esh, ISIL or ISIS).

ISIS renamed itself to the Islamic State, resulting in a profoundly confusing alphabet soup of acronyms. To be clear, “the Islamic State” is a terrorist organization and also refers to a pseudo-state that lasted for more or less five years. That state, in turn, was the base for the proclamation of a new “caliphate,” a fictional claim conjured up by the terrorist group to control all of the world’s Muslims. (Media organizations use ISIS/ISIL, and the Islamic State alternatingly to refer to the terrorist group. Many have stuck with ISIS as the label even after the group changed its name. Here, ISIS is used when referring to the group and “Islamic State” when referring to the territory it occupied.)

At its peak, the Islamic State controlled about ten million people across northern Iraq and eastern Syria comprising a territory the size of the United Kingdom.

The Islamic State was the product of an invading army of crowd-sourced foreign volunteers. In 2017, Army Lt. Gen. Michael K. Nagata, the director of the National Counterterrorism Center’s Directorate for Strategic Operational Planning, assessed that an estimate of 40,000 foreign terrorist fighters from at least 120 countries had been identified, at that time, as having joined the Islamic State. Nagata admitted the number was imprecise, and added, “It is probably the most ethnically diverse, sociologically diverse, non-monolithic [. .] foreign fighter problem we have seen, so far.” It was also “inarguably the largest foreign fighter challenge the world has seen in the modern age.”8

Explaining jihadist terrorism in the West

Why do they do it? There is a large, sprawling literature on the root causes of terrorism and on Al Qaeda specifically. Academic specialists in security studies and terrorism studies (which are not the same fields) have, however, been curiously blind to the ways in which globalization made it possible for an effective non-state networked global organization to emerge, grow, and manage its operations. These global terrorist networks work differently from states, but may occupy the same stage. Security studies have focused on states as the effective actors in international relations, and downplayed the independent importance of international terrorist networks. In their view, terrorism only becomes significant when it finds a state sponsor. Martha Crenshaw perceptively pointed out in her book Explaining Terrorism (2011) that international relations theorists have an ingrained

state-centric bias.9 The bias has made international relations specialists dismiss the national security risk that a non-state actor may pose to domestic security as well as to global stability. It followed from the state-centric theories that terrorists will not be able to undermine a Western state, nor bring about a shift in the balance of power in the global system.

Sociologically-inspired approaches have their own blind spots. Rather than identifying state sponsors, terrorism studies specialized in bottom-up analyses of the root causes of terrorism and motivations—of which there are so many that they cannot easily be generalized. However, they tend to ignore the broader strategic thinking of a sophisticated global leadership.

Law enforcement and intelligence agencies too have had trouble connecting the dots. The 9/11 Commission Report found that the information needed to anticipate and assess the threat posed by Bin Laden had been flagged and routinely put on the desks of successive presidents. The institutions responsible for the country’s safety nevertheless failed to prevent the attacks because of “four kinds of failures: in imagination, policy, capabilities, and management.”10 The world of academia may also be faulted for a lack of imagination, and for a failure to recognize the big picture.

Broadly, three schools of thought—three-and-a-half schools, if we include the argument that Islam itself is the root cause of the problem with Islamist extremism—have dominated the discussion of why Al Qaeda decided to attack the “far enemy,” the United States and its Western allies. I will discuss them briefly in turn and then sketch an alternative perspective.

The first line of argument is what Max Abrahms calls the Strategic Model of Terrorism, which is associated with what is known as the Realist school in international relations theory. This school of thought is particularly influential in security studies in American universities and in the foreign policy establishment. Realist theory takes it for granted, first, that states are the central actors in international politics and, second, that what states do is motivated by national interests. Expressions of moral concern or ideology are simply cloaks for self-interest.11 States may be resource rich or resource poor, but all compete for influence and control. Terrorism is accordingly understood as a tactic, used in the competition between states, to gain control of territory, of people, and of governance.

In his book Dying to Win (2005) Robert A. Pape argued that terrorism works. The title says it all. Suicide terrorists are a substitute for smart bombs. Strap a vest on somebody and point him or her in the right direction, the human wrapped in the bomb will get to the target. Terrorism is selected

when it is the most efficient means to achieve an objective, and so is suicide terrorism. As for the suicide terrorist’s own motivations, they are incidental to the strategic interests of the terrorist organization. There is nothing particularly religious about jihadist suicide terrorism. Many terrorist groups aside from Al Qaeda have used suicide missions, among them groups that have no sympathy for Islamist conceptions of martyrdom. The Realists can cite historical examples in support of their thesis. National liberation movements from the African National Congress to the Palestine Liberation Organization and the Basque and Northern Irish separatists used terrorism to ratchet up costs to the state but were pacified by concessions and compromises.

Al Qaeda’s campaign against the West, Pape writes, “is mainly a response to foreign occupation rather than the product of Islamic fundamentalism.”12 He insists it is wrong to assume that jihadist suicide terrorism is the product of an evil ideology. The ideology may be evil, but an evil ideology is not the cause of what the terrorists do.The jihadist terrorist campaign will continue as long as the United States has troops in Iraq and on the Arabian Peninsula. This makes the United States an occupying force and therefore the target. Withdraw, let the locals handle the problem, Pape advised, and the attacks on the United States and the West will cease.

Max Abrahms, also coming from the Realist school, argues that, on the contrary, terrorism does not work. It repels the people whose support the terrorists seek. And the more violent terrorists become, the less inclined governments will be to negotiate with them.13 The 9/11 attacks are an example. They hurt rather than helped Al Qaeda. After the 9/11 attacks, Al Qaeda’s organization was decimated, and its leadership forced into exile. The strike was a disaster for the movement. According to Abrahms, the Islamic State imploded from within because its “caliphate” depended on a reign of terror and therefore was not sustainable.

So, what should Western governments do? Ignore the terrorists, Abrahms counsels. Don’t talk them up. Don’t kill the leaders. That will only rouse the followers. Governments should engage with the terrorist leaders, but in private. Smart leaders will control their followers and limit the violence. Bad leaders will ratchet up the violence and so lose support. When militant leaders are stupid enough to broadcast their massacres, let’s not stand in their way. The more violent, the less likely the group is to succeed.

Abrahms’ final piece of advice is that governments should put his book “into the hands of militant leaders. Following his rules will help them

achieve their goals.”14 Bin Laden had a surprisingly large collection of books written by American analysts and academics in his house in Abbottabad, Pakistan. He might have been interested. But would ignoring Al Qaeda persuade Ayman al-Zawahiri, the Egyptian physician and militant who became the leader of Al Qaeda after Bin Laden’s death in 2011, to negotiate? There is no plausible scenario under which that is a likely outcome.

In twenty years, Al Qaeda has not been able to stage another coup on the scale of the 9/11 attacks. International terrorism could be ignored as a risk to American domestic security—which among some of the more isolationists thinkers in international relations is all that matters—unless they have “weapons of mass destruction” (WMD) capable of causing mass civilian casualties. And it is unlikely that terrorist groups will get their hands on WMDs without the help of a state sponsor.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the list of candidates for state sponsors of terrorism narrowed to Iran, Iraq, and North Korea. Rogue countries like these could—and should—be kept in check by the traditional means available to the United States as a superpower. Hawks in the Bush administration trumpeted a Saddam Hussein-Bin Laden “axis of evil” that justified the 2003 Iraq War. There was no such alliance, although the theoretical model insisted it just had to be there. Ironically, the architects of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, Dick Cheney, the Vice-President, Donald Rumsfeld, the Secretary of Defense, and Paul Wolfowitz, security advisor to George W. Bush, were all political scientists, and adherents of Realist theory. They drew the conclusion that, with the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States was left standing as the “hegemon” in a “unipolar” world. Now it was up to the United States to set the rules. (There was also the idea that in a unipolar world spreading democracy by military force was in the long-term interest of the United States.) Daniel Deudney and John Ikenberry describe the disagreement between interventionists and advocates of restraint as an inter-mural dispute among Realists.15 This disagreement also does not overlap neatly with partisan political divisions. Democrats and Republicans alike are split between advocates of restraint, bordering on isolationism, and humanitarian “interventionists” accused of perpetuating an “endless” war on global terrorism.

Realists who do not favor military intervention often advocate variants of what they call “offshore” balancing, foregoing direct military interventions and letting the locals handle local problems. “Onshore” deployment brings with it the risk that the United States will make itself responsible for

situations that the country cannot, and need not, control. The wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are held up as prime examples. However, isolationism cannot put the genie of globalization back in the bottle. Can the United States simply turn away when humanitarian concerns demand intervention? From Cambodia’s Pol Pot to Serbian atrocities in Bosnia, and on to genocide in Rwanda and the Islamic State, the American response has been inconsistent. When human rights advocates argue for military intervention to prevent atrocities, Realists are the skeptics at the table.

When it comes to terrorism far away from American shores, Realists of both camps agree that terrorism is a top-down problem. Modify how the leaders act, and so reduce the demand for terrorists. If the demand for terrorists goes away, the terrorists will also go away. Rather like Abrahms, Audrey Cronin argues, in How Terrorism Ends, that states should start negotiating with leaders of terrorist groups, including Al Qaeda. It is a weak and divided organization, she writes, which has actually been strengthened by the overreaction of government agencies.16 Similar views may be found in the works of a number of political scientists: John Muller and Mark G. Stewart, Marc Sageman, and Charles Kurzman, to mention a few.17 But, as Cronin acknowledges, Al Qaeda has outlived the statistical life expectancy of terrorist groups—and it has repeatedly made a comeback after predictions of its demise.

The Realist worldview suffers from an unrealistically narrow conceptualization of rational action. Terrorist groups base their strategies and actions on their own theories about this world and the next.18 The Realists assume that the jihadists are either out to get their own patch of land or are proxies for states seeking to control territory. This misconstrues the aims of the jihadist movement. The jihadist worldview is anchored in an apocalyptic vision of an Islamic awakening that will sweep away all borders. With that comes a theory of history, and there follows, logically enough, a blueprint for action that relies on divine intervention.

Al Qaeda has failed many times but has a capacity for recovery unparalleled among terrorist groups. Bin Laden fatally miscalculated how the United States would respond to the 9/11 attacks. The retaliation that followed caused huge damage to him personally and to his organization. But the Realist school has consistently underestimated the resilience of Bin Laden’s organization and of the jihadist networks. The state-centric focus of the Realists blinds them to the true strengths of the jihadist movement. The jihadists are capable of adjusting tactics to the facts on the ground. They can

be savvy and flexible exponents of realpolitik. But any accommodations or trade-offs they make are tactical. They will not compromise on the ultimate objective. Any concessions they make are temporary and can only be justified if they are in the interest of the long-term goal. This is to take back control of all territories once governed by Allah’s law, the sharia. (The boundaries of the territory to be reclaimed are a matter of debate.)

The comparison of the jihadists to national liberation movements or ethno-national separatists, who want their own state, is therefore profoundly misleading. The jihadists have no homeland. They do not want a state for themselves. They want the end of all states. They see the weakening of Muslim states as a vehicle for uniting the imaginary global ummah, the borderless Muslim nation of righteous believers. They fight to speed up the process that leads inexorably to the return of the Messiah and the final Day of Judgment. Their ultimate goal is to hasten the coming of the Apocalypse. Until that day comes, they will fight a global holy war.19 Their apocalyptic dreams may be fantastical, but their means are rational enough.

Wait, wait, skeptics may say, did the Islamic State not proclaim a “state”? They did, but they also declared a worldwide extraterritorial caliphate that was understood by followers as a springboard to global domination. Al Qaeda and the Islamic State had differences about the “state” vs. “caliphate” doctrine. Bin Laden allowed “emirates” but not “caliphates.” The disagreement between Al Qaeda and the Islamic State was partly a matter of theory. The faithful had to figure out which step on the escalator to the global jihadist revolution the Syrian civil war had landed on in late 2013, when the jihadists gained the upper hand among the rebel groups fighting the Assad regime. The Al Qaeda view was that by wedding itself to a “state,” the Islamic State had neglected the duty to pursue a global revolution. The break-away affiliate would be tied down in a fight for every piece of soil of which it had taken ownership. (The Al Qaeda bosses were right. In March 2019, after dragged out trench warfare, the Islamic State lost control of the last slice of territory in eastern Syria and northern Iraq it had claimed for its caliphate five years previously.)

The jihadists are often depicted as violent thugs but they are more than that. Their tactics and strategies are scripted by elaborate doctrines deduced by a militant intelligentsia. The Islamic State followed a theory for how to progress through the stages of the revolution to the end of history. The author of this theory was a jihadist intellectual who used the alias Abu Bakr Naji. (Naji is allegedly a pseudonym for an Egyptian named Mohammad Hassan Khalil al-Hakim who may have been killed in 2008.)