https://ebookmass.com/product/violent-modernities-culturallives-of-law-in-the-new-india-oishik-sircar/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Cultural Labour: Conceptualizing the ‘Folk Performance’ in India Brahma Prakash

https://ebookmass.com/product/cultural-labour-conceptualizing-thefolk-performance-in-india-brahma-prakash/

ebookmass.com

The New Cambridge History of India, Volume 1, Part 1: The Portuguese in India M. N. Pearson

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-cambridge-history-of-indiavolume-1-part-1-the-portuguese-in-india-m-n-pearson/

ebookmass.com

How Lives Change: Palanpur, India, and Development Economics Himanshu

https://ebookmass.com/product/how-lives-change-palanpur-india-anddevelopment-economics-himanshu/

ebookmass.com

Medieval Animals On The Move: Between Body And Mind 1st Edition Edition

László Bartosiewicz

https://ebookmass.com/product/medieval-animals-on-the-move-betweenbody-and-mind-1st-edition-edition-laszlo-bartosiewicz/

ebookmass.com

Turkey and the EU in an Energy Security Society: The Case of Natural Gas 1st ed. Edition Dicle Korkmaz

https://ebookmass.com/product/turkey-and-the-eu-in-an-energy-securitysociety-the-case-of-natural-gas-1st-ed-edition-dicle-korkmaz/

ebookmass.com

Conceptual Physics Pearson International Edition Paul G. Hewitt

https://ebookmass.com/product/conceptual-physics-pearsoninternational-edition-paul-g-hewitt/

ebookmass.com

Advances in heat transfer 52 1st Edition J.P. Abraham

https://ebookmass.com/product/advances-in-heat-transfer-52-1stedition-j-p-abraham/

ebookmass.com

Teaching to Change the World 5th Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/teaching-to-change-the-world-5thedition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Engineering Practice with Oilfield and Drilling Applications 1st Edition Scott D. Sudhoff

https://ebookmass.com/product/engineering-practice-with-oilfield-anddrilling-applications-1st-edition-scott-d-sudhoff/

ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/elemental-whitney-hill/

ebookmass.com

‘Violent Modernities is an expression of love as a brawl with law for space—the space to invoke, listen to, and perform law differently—in a quest marked by grace and daring.’

– Vasuki Nesiah, professor, New York University, USA (from the foreword)

Law and violence are thought to share an antithetical relationship in postcolonial modernity. Violence is considered the other of law, lawlessness is understood to produce violence, and law is invoked and deployed to undo the violence of lawlessness. Violent Modernities uses a critical legal perspective to show that law and violence in the New India share a deep intimacy, where one symbiotically feeds the other. Researched and written between 2008 and 2018, the chapters study the cultural sites of literature, cinema, people’s movements, popular media, and the university to illustrate how law’s promises of emancipation and performances of violence live a life of entangled contradictions. The book foregrounds reparative and ethical accounts where law does not only inhabit courtrooms, legislations, and judgments, but also lives in the quotidian and minor practices of disobediences, uncertainties, vulnerabilities, double binds, and failures. When the lives of law are reimagined as such, the book argues, the violence at the foundations of modern law in the postcolony begins to unravel.

Oishik Sircar is associate professor, Jindal Global Law School, Sonepat, India.

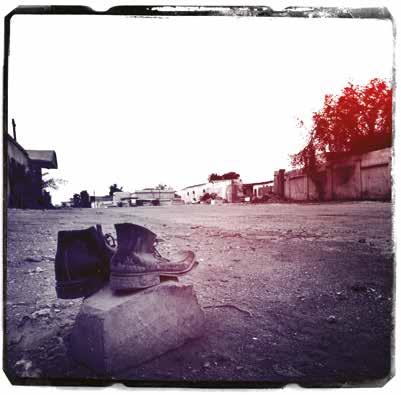

Cover photo: Oishik Sircar

design: Siddhartha Dutta

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in India by Oxford University Press

22 Workspace, 2nd Floor, 1/22 Asaf Ali Road, New Delhi 110 002, India

©Oxford University Press 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

First Edition published in 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

ISBN-13 (print edition): 978-0-19-012792-3

ISBN-10 (print edition): 0-19-012792-9

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-0-19-099214-9

ISBN-10 (eBook): 0-19-099214-X

Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro 11/13 by The Graphics Solution, New Delhi 110 092 Printed in India by Rakmo Press Pvt. Ltd.

For D,

fierce

and tender

That life is complicated is a fact of great analytic importance. Law too often seeks to avoid this truth by making up its own breed of narrower, simpler, but hypnotically powerful rhetorical truths.

—Patricia J. Williams, The Alchemy of Race and Rights: Diary of a Law Professor (1992)

It has long been my belief that law is the most disabling or estranged of professions. Such at least is its most radical danger: it inculcates a fear which finds its most prominent expression in the closure of the legal mind, in the lawyers’ belief in a norm or rule which speaks as ‘the law’.

—Peter Goodrich, Law in the Courts of Love: Literature and Other Minor Jurisprudences (1996)

Go back to uni, study the law. Accept the law, even when it’s unjust.

—Kamila Shamsie, Home Fire (2017)

Contents

List of Figures ix

Foreword xi

Acknowledgements xvii

Preface xxiii

List of Abbreviations xli

PART 1: … the Theoretical…

1. Spectacles of Emancipation: Reading Rights Differently 3

2. Beyond Compassion: Children of Sex Workers and the Politics of Suffering (with Debolina Dutta) 53

3. Bollywood’s Law: Cinema, Justice, and Collective Memory 98

4. New Queer Politics: Notes on Failure and Stuckness in a Negative Moment 144

Part II: … is Personal…

5. The Silence of Gulberg: Refracted Memories, Inadequate Images 189

6. Professor of Pathos: Upendra Baxi’s Minor Jurisprudence

7. The Conduct of Critique: Jurisdictional Account of a Feminist Journey

Figures

5.1 The entrance to Gulberg Society 199

5.2 Police sampatty (property) 200

5.3 A posteriori scenes of violence 1 201

5.4 A posteriori scenes of violence 2 202

5.5 Silence and foliage 203

5.6 A map with no numbers 204

5.7 ‘There is no final photograph’ 205

Foreword

Hanif Kureishi’s short story, ‘My Son the Fanatic’, tells the story of a Pakistani immigrant, Parvez, and his son, Ali. Parvez invests decades in his work as a taxi driver to create a life sustained by ambitions and hopes for his son’s modern British future—marked for him by the twinned ethe of tolerance and assimilation. Imagine how unnerved he is then when he finds that as he grows up, Ali pivots towards orthodox Islam: Turning from his accountancy exam to mosque devotions, rejecting his cricket bat for a prayer mat, dismissing his father’s celebration of secular moral tolerance for an authoritative ethical compass, turning from material rewards to religious discipline, rejecting the promise of assimilation into ‘modernity’ for the promise of spiritual fulfilment in the afterlife, deriding his father’s debts to white Britain, to instead embrace visions of worlding beyond those of the West. Parvez, the mild-mannered tolerant liberal, becomes incensed at his son’s rejection of those very promises of modernity that provided scaffolding for his immigrant dream. He beats up his son till Ali is on the floor, kicked, punched, and virtually insensible. Through bloodied lips, Ali has the final word: ‘So who is the fanatic now?’

The imbrications of the discourses and institutions of modernity and violence have been pivotal to colonial and post-colonial histories. This imbrication is a central dimension of our current moment from

Foreword

the domestic and micro-political (such as in Kureishi’s short story), to the global and macro-political (consider the war in Afghanistan). Oishik Sircar’s remarkable book illuminates these tangles of modernity and violence with sophistication, originality, and insight. Violent Modernities is anchored in contemporary India and that historical context is central to the political struggles Oishik is invested in, and the analytical arguments he advances. Indeed, vigilant about the risks of universalizing his critical interventions, he insists that the work is not conceived as ‘atemporal and portable’. This work invites us into grappling with the specific histories and geographies of contemporary India and shines a light onto the braiding of the ‘rule of law’ and violence in this pivotal moment in Indian debates about modernity and its futures. However, I began with a story of modern Britain and its promises to underscore how the theoretical portals Oishik opens up have a wider purchase. That grappling with debates grounded in the specific histories and geographies of contemporary India have much to teach us about how violence inhabits discourses and institutions of modernity, including the ‘rule of law’, in other spaces and places. Central to the entanglements of ‘violent modernity’ that are the focus of this book, is the terrain of law, its institutionalization and its imagination. The book speaks of how laws get constituted through processes that have far-reaching local impacts, while emerging from transnational processes of professionalization of legal knowledge. ‘Global Economic Constitutionalism’ and ‘New Legal Order’ are examples of these travelling knowledge regimes that Oishik describes (drawing on Jasbir K. Puar) as ‘history vanishing’ frameworks. They build on long-standing investments in notions of the ‘rule of law’ that have emerged as distinctive features of how modernity has come to be defined by dominant institutions and political cultures in India. This work tells us how law and cultures of legality interpolate modern citizenship through what Oishik identifies as ‘spectacles of emancipation’ that seduce faith and compliance through the mirage of law as a conduit for justice, or even as itself a metonym of justice. The striking achievement of the ‘spectacles of emancipation’ that this story lays bare is that liberal legality and majoritarian violence have moved forward as co-travelers in shaping the contours of modern citizenship from courtroom battles to cinematic dramas. Thus, while the Special Investigation Team exonerated Narendra Modi for his

Foreword xiii

role in the orchestration of the anti-Muslim pogrom in Gujarat, giving him a ‘clean chit’ carrying the imprimatur of supreme legality, cinematic representations of the afterlives of Gujarat in cultural memory represent and rationalize the constitution and ‘state-making’ practices that were the pre-histories of the pogrom. Through analysis of the Best Bakery massacre and the Bollywood film Dev, Oishik shows how a space is made for Islamophobic violence that is represented in both law and cinema as ever present but with no one responsible—indeed, it emerges as compatible with the ‘secularism, legalism and developmentalism of the New Indian State’. Naturalized and aestheticized as a necessary backdrop for the nation, the film allows anti-Muslim violence to be remembered anew in ways that re-inscribe national mythologies of heritage and heroes, reconciliation and redemption, tolerant Hindu majorities and ever outsider Muslim minorities. Oishik describes a ‘jurisprudential–aesthetic’ narrative compact that carries subliminal cinematic cues (about Hindi–English as the national–universal for instance) that work alongside constitutional inheritances to shape conditions of legibility for modern political subjectivity in ways that exclude and marginalize minorities. The analysis powerfully portrays the mythic lives of law—offering nuanced portrayals of the hyperbolically visible and audible jurisprudential orientations of Bollywood on the big screen, but also with an eye acutely alert to the nuances of affect in a film’s reception, attentive to the work of ‘minor jurisprudence’ in the cinemagoer’s aesthetic consumption.

Critical legal theorists who speak of the social construction of law have developed a body of work on the development of institutions and traditions of judicial interpretation; equally, there has been work on the relationship between social movements and legal developments. This book takes these conversations further into the realm of cultural production and connects the dots between institutions tasked with the administration of justice (including social services), social movements making justice claims (for instance, around sex work in one instance, and sexual rights in another) and the interpolation of the juridical in realms such as film (documentaries to advertisements). For instance, in the case of children of sex workers, the analysis (co-authored with Debolina Dutta) offers a compelling critique of how dominant humanitarian tropes of ‘rescue’ deny

Foreword

children’s agency and the complexity of their familial and social relations. It is an argument that deconstructs the affective structure of compassion in this domain, and how it facilitates violence and abuse against these same communities precisely by advancing narratives in their name.

The complexity of the multiple lives of law and its disciplinary technologies that Oishik describes is that these dynamics worked differently for social movements seeking institutional legibility for the sexually marginalized in struggles for the decriminalizing of adult, consensual, and private sex. Here, the driving trope of liberal modernity was not humanitarian compassion but the mythos of equal rights, and how it has been invoked and deployed in ways that domesticated the subversive thrust of queer politics. Oishik’s argument in this discussion deconstructs the affective structure of inclusion into neoliberal, market-friendly modernity, and how it presses depoliticization and individualization onto queer communities precisely by advancing narratives in their name for the redemption of ‘New India’ and new markets. In both these cases, Oishik is not just an observer but an activist and his reading of these domains also situates his own creative interventions and solidarities in these struggles (including, he says, in performing ‘stuckness’, following Lauren Berlant). Thus, these are not arguments for abandoning activism but for doing it differently by wrestling with intersecting structures and identities to stay with the fraught political challenges of thinking collaboratively with social movements about how to advance justice claims but refuse ‘homonationalism’ and interrupt neoliberal citizenship.

This a book of dazzling erudition—Oishik is in conversation not only with other legal scholars in India and elsewhere, but also with the theorizing of legal modernity in a range of other disciplines from literary theory to postcolonial studies to anthropology to queer theory. Masterfully drawing attention to and analyzing the assemblage of mnemohistories in the formation of a national consciousness driven by the juridical unconscious, this work offers a remarkable tour de force journey through battles over the life of the law, showing the co-constitutive intimacy of constitutional and cultural domains. Yet, what is most striking is the

Foreword xv

insistent self-reflexive situating of these conversations in his own role in academia and social movements with particular political investments. The discussion of his feminism and the vexed entanglements of those commitments, from the personal to the professional to the political, offers but one example of what is a running sub-narrative that is a dialogic companion to every argument in the book.

In other words, the book’s erudition and multiple interdisciplinary conversations are not channeled into the disinterested pursuit of critique as enlightenment, but a constant questioning of the theorist as activist, and the activist as theorist. In fact, one may situate the notion of enlightenment here as akin to the notion of critique that Foucault articulates in ‘What is Enlightenment?’ Foucault argues that Kant’s essay should not be understood as a celebration of the knowledge regimes associated with the historical moment of enlightenment but as an interrogation of that moment—or indeed, a critical interrogation of the moment one is in. Such an interrogation is a constant companion to Oishik’s analysis—an alter ego, pushing at every analytical move, grappling with hard questions about the relation of text and context at each turn, relentlessly holding itself to account. In this sense, in this book that gives expression to the responsibilities of critique alongside the hope embedded in struggle, Oishik may be a worthy inheritor of Upendra Baxi’s mantle and his simultaneously inspiring and discomforting presence in a wounded world.

In the Kureishi short story that I began with, Ali criticizes his father’s investment in Britain’s promises, asking ‘Papa, how can you love something that hates you?’ Parvez does not answer the question but perhaps the story of Parvez’s love is that he had to fight against the hate of injustice to create the space for his life; that fight engendered the investment that Ali terms love. Oishik’s critique of the law and the injustices it has wrought in the name of justice, also loves wrestling the law for the space that justice struggles demand. This comes through in the aesthetics and rhythms of this beautifully written book that was such a pleasure to read. I lean on James Baldwin here who speaks of love as ‘a battle; love is a war’—but love is also, as he says in another passage, ‘a state of being, or a state of grace … in the tough and universal sense of quest and daring and growth.’ Violent Modernities in chapter after chapter, can be seen to be just

xvi Foreword

that, an expression of love as a brawl with law for space—the space to invoke, listen to and perform law differently in a quest marked by grace and daring.

Vasuki Nesiah Professor of Practice

Gallatin School of Individualized Study New York University

Acknowledgements

A book is not an isolated being: it is a relationship, an axis of innumerable relationships.

— Jorge Luis Borges, Labyrinths(1962)

The essays collected in this book document my scholarly and activist journeys through the labyrinths of the learnings and failings of my politics over a period of a decade. I would like to thank those whose influences have played a foundational role in both strengthening and questioning the praxes of my proclivities and predilections over these years.

Ravi Nair, for initiating me into the world of human rights activism and research. Ranabir Samaddar, for making me realize that activism is fortified through theorizing. Hutokshi Doctor, for training me to never underestimate the intelligence of readers and for cautioning me against my love for jargons. Sharmila Rege, for showing me the joys of bringing together teaching and writing for social justice. Rustom Bharucha, for demonstrating through his writing and thinking how to read politics into aesthetics and vice versa. Ratna Kapur, for lending me a feminist language to work through my double-binds. Brenda Cossman, for pushing me to think of the worth of critique as scholarly practice. Shaun McVeigh, for provoking me to think of conduct as different from critique. Jasbir Puar, for enlivening theory as life practice.

Acknowledgements

Sundhya Pahuja, for impressing on me the political worth of scholarly conventions. Dianne Otto, for keeping alive the flame of activism in scholarship. Peter Rush, for showing me why style matters for scholarship. Joan Nestle, for insisting on the political necessity of pleasure and poetry. Jennifer Nedelsky, for emphasizing how material conditions of gendered work are intrinsic to the politics of scholarship and activism. Janet Halley, for urging me to never flinch if I want to take a break. Ritu Birla, for teaching me history as process, not event. Flavia Agnes, for keeping alive a faith in law’s promises in dark times. Upendra Baxi, for practicing a scholarly life that brings alive the struggles of keeping faith in law’s promises and learning from law’s betrayals. Friends, mentors, comrades, colleagues, and collaborators whose lives, work, and generosity have materially, gastronomically, emotionally, and intellectually sustained and nurtured me in ways that might be completely unknown to them: Adil Hasan Khan, Trina Nileena Banerjee, Sakyadeb Choudhury, Shayanti Sinha, Deepti Mohan, Saptarshi Mandal, Rohini Sen, Rajshree Chandra, Claire Opperman, Anirban Ghosh, Garga Chatterjee, Shilpi Bhattacharya, Dipika Jain, Samia Khatun, Carolina Ruiz Austria, Alivia Dey, Ann Genovese, Sara Dehm, Luis Eslava, Rose Parfitt, Vik Kanwar, Julia Dehm, James Parker, Cait Storr, Dolly Kikon, Yasmin Tambiah, Sally Engle Merry, Kalpana Kannabiran, Saumya Uma, Bina Fernandez, Jaya Sagade, Maria Elander, Bikram Jeet Batra, Farrah Ahmed, Mohsin Alam Bhat, Mohsin Raza Khan, Albeena Shakil, Rahul Rao, Nikita Dhawan, Meenakshi Gopinath, Swati Bhatt, Agyatmitra Shantanu Mehra, Ruchira Goswami, Arun Sagar, Arpita Gupta, Rajgopal Saikumar, Priya Gupta, Sneha Gole, Anagha Tambe, Sannoy Das, Danish Sheikh, Prabhakar Singh, Maddy Clarke, Sagar Sanyal, Aashita Dawer, Ankita Gandhi, Sanskriti Sanghi, Max Steuer and Anish Vanaik.

My students at Jindal Global Law School who have humoured and tolerated my ideas in the Jurisprudence, and Violence, Memory, and Justice courses—some of which were built on the essays in this book and some which contributed to the essays. Thanks to Shivangi Sud, Uday Vir Garg, Amshuman Dasarathy, Rhea Malik, Aishwarya Koralath, Medha Kolanu, Sanjana Hooda, and Rohan Talwar for your research assistance. Pallavi Mal, Muskaan Ahuja, Ishani Mookherjee, and Shubhalakshmi Bhattacharya, for your assistance with teaching. Rishabh Bajoria, Siddharth Saxena, Ayushi Saraogi, Dikshit Sarma Bhagabati, Malini Chidambaram, Neeta Maria Stephen, Katyayani

Acknowledgements xix

Suhrud, and Amala Dasarathy for your provocations in the classroom. I am immensely grateful to each one of you for your efforts, engagement, and unremunerated labor. You have been my closest readers and most thoughtful interlocutors. You are the motivation behind bringing this book out. If I have an imagined ideal reader in mind, it is a young student at an Indian law school like you. Thank you for teaching me about how to make the politics of law relevant and accessible for tomorrow’s critical lawyers.

A range of organizations and institutions supported the writing of the essays at various times for over a decade without whose intellectual, financial, and infrastructural support I could have possibly never written. Thanks to: Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, Krantijyoti Savitribai Phule Women’s Studies Centre at the University of Pune, West Bengal National University of Juridical Sciences, Child Rights and You, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Public Service Broadcasting Trust, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta, Johannesburg Workshop on Theory and Criticism at the University of Witwatersrand, Australia India Institute at the University of Melbourne, Institute for Global Law and Policy at Harvard Law School, Institute for International Law and the Humanities at Melbourne Law School, and the Jindal Global Law School (JGLS). Among these, I spent the most amount of time in Melbourne and JGLS, Sonipat and I am especially thankful to these institutions. I would like to particularly thank C. Raj Kumar, my dean at JGLS for fostering a culture of critical interdisciplinary legal research that has been most generative for me. JGLS has always been a location of contradictions for me—one with which I have a relationship of uneasy affinity. That is what has also made it one of the most provocatively productive spaces to inhabit as a critical legal academic in the New India.

I would like to acknowledge that the writing done at the Melbourne Law School was carried out on the lands of the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation who have not ceded their sovereignty. I pay my respects to their elders, past, present, and emerging. This acknowledgement is necessary because even as a temporary migrant to the settler colonial state of Australia, I was the beneficiary of colonialism’s loots that allowed me to pursue my doctoral studies there.

Every expression of gratitude will fall short for Vasuki Nesiah’s incisive and generous foreword to the book. Thank you for writing

Acknowledgements

it so beautifully. Vasuki has been a constant figure of encouragement and support for several years. I continue to learn new lessons about scholarly humility, collegiality, and care from her writings and teaching. It is a very special feeling to have the essays prefaced by her words (written under the very difficult circumstances of the COVID-19 lockdown in New York City).

I am so excited about this book featuring a cover image designed by Siddhartha Dutta. I cannot thank him enough for lending an unusual aesthetic intensity to an ordinary photograph that I had taken many years back. I have for long admired his creative imagination as a visualizer and it is an honour to have his work on the cover.

Irrespective of their interest in what I research on and write about as an academic, my family members have remained an unconditional source of love, overenthusiasm, and distraction. I’d especially like to acknowledge the presence in my life of my parents, Anjan and Anjana, my mother-in-law, Pratima, my aunts, Swapna, Roma, Ratna, Manjula, uncles, Amal, Partha, Tapan, and Pradip, my siblings, Ishika and Shayak, their partners, Sayak and Aashima respectively, my little nephew Ricco, my cousins, Sreya, Kanishka, Tisha, and Ayan, and the indelible memories of my grandparents, Bani, Prafulla, Santosh, Dolly, Krishna Narayan, my uncles, Alok and Ranjan, and my father-in-law, Ajit.

Since much before the ten-year period through which the essays in this book were researched, written and published, I have been living a life of immense joy, exhilarating frivolity, and deep reflection with D. She has been my teacher in how to live an ethical life that takes the quotidian and the relational seriously. She continues to exemplarily live out both the possibilities and perils of ‘the personal is political’. Her sarcasm keeps my academic vanity in check and her love provides a lihaaf of comfort and care that I cannot live without. She is my fiercest critic and my most intellectually stimulating collaborator. I am proud to be able to feature one of our collaborative works in this book. To D—on her fortieth birthday—I dedicate this book as a gift to celebrate our life together as partners in politics, profanities, and vulnerabilities. ____

Special thanks to the former and current team at Oxford University Press who helped with bringing the book to fruition: Manish Kumar,

Acknowledgements xxi

Barun Sarkar, Moutushi Mukherjee, Mousumi Bera, Marianne Paul and Paulami Sengupta. I also thank the two anonymous reviewers whose very supportive feedback helped with sharpening some key arguments.

I thank the editors of the journals and books where the essays were first published for giving me writing space and to the publishers for the permission to republish them as part of this book. Thanks are also due to the peer reviewers who had commented on the articles and chapters for their considered reading and feedback.

Chapter 1 was published as ‘Spectacles of Emancipation: Reading Rights Differently in India’s Legal Discourse,’ Osgoode Hall Law Journal 14: 3 (2012) 527–573. Chapter 2 (co-authored with Debolina Dutta) was published in parts as ‘Beyond Compassion: Children of Sex Workers in Kolkata’s Sonagachi’, Childhood: A Journal of Global Child Research 18: 3 (2011), 333–349 and ‘Notes on Unlearning: Our Feminisms, Their Childhoods’, in Rachel Rosen and Katherine Twamley (eds) Feminism and the Politics of Childhood: Friends or Foes?, London: UCL Press (2018) 75–81. Chapter 3 was published as ‘Bollywood’s Law: Collective Memory and Cinematic Justice in the New India’, No Foundations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Law and Justice 12 (2015) 94–135. Chapter 4 was published as ‘New Queer Politics in the New India: Notes on Stuckness and Failure in a Negative Moment’, Unbound: Harvard Journal of the Legal Left XI (2017) 1–36. Chapter 5 was published in parts as ‘The Silence of Gulbarg: Some Inadequate Images’, Human Rights Defender 25: 1 (2016) 24–28 and ‘Gujarat 2002: Refracted Memories, Inadequate Images’, in Satvinder S. Juss (Ed.) Human Rights in India, London: Routledge (2019) 125–151. Chapter 6 was published as ‘Professor of Pathos: Upendra Baxi’s Minor Jurisprudence’, Jindal Global Law Review 9: 1 (2018) 203–222. Chapter 7 was published in parts as ‘Doing and Undoing Feminism: A Jurisdictional Journey’, Economic and Political Weekly L: 12 (2015) 44–47 and ‘Doing and Undoing Feminism: A Jurisdictional Journey’, in Romit Chowdhury and Zaid Al Baset (eds) Men and Feminism in India, New Delhi: Routledge (2018) 73–100.

Preface

Negative Spaces

The relationship between law and violence is paradoxically structured: law is the opposite of violence, since legal forms of decisionmaking disrupt the spell of violence generating more violence. At the same time, law is itself a kind of violence; because it imposes a judgment that determines its ‘subject’ like a curse.

— Christophe Menke, ‘Law and Violence’ (2010: 1)

[L]aw as a unified entity can only be reconciled with its contradictory existences if we see it as myth.

— Peter Fitzpatrick, The Mythology of Modern Law (2002: 1)

That law and violence share an antithetical relationship in modernity is a virtuous cliché.1 Violence—both exceptional and ordinary—is commonsensically considered the other of law.2 It is axiomatic to value lawfulness as progressive and lawlessness as primitive.3 A condition of lawlessness is understood to produce violence. A fetishistic desire for the rule of law and human rights (Kerruish 1992: 99), particularly in the postcolony (Comaroff & Comaroff 2006), is pursued as a means of resisting and repairing the violence of lawlessness. Unless, lawlessness is desired by law itself (couched in the language

Preface of exceptionalism) to achieve the promise of a greater common good (Hussain 2006; Agamben 2005; Roy 2019: 25–75).

In Violent Modernities: Cultural Lives of Law in the New India, I locate law and violence in a negative space—‘the recessive areas that we are unaccustomed to seeing but that are every bit as important for the representation of the reality at hand’ (Daly 2003: 771)—where they are not adversaries but allies. The seven essays4 that follow constitute a bricolage5 that speaks to select ‘critical events’ (Das 1995) in contemporary India to offer explorations of the paradoxical relationships between law and violence. Each essay tells a story about the relationship between law and violence not as one of animosity, but of deep intimacy, where one symbiotically feeds off the other (Cover 1995: 203–8). Instead of casting law as the heroic Hercules that slays the hydra-headed demon of violence (Flood & Grindon 2014: 7–9),6 the essays unsettle and blur this relationship—not to claim that there are no differences between law and violence, or to favour violence over law, but to interrogate the terms on which such differences are founded, sustained, and reified. I foreground the political and ethical stakes involved for a critical legal praxis in considering either law or violence as hermetically sealed, Manichean categories of good and bad.

Modern law’s mythology—founded on the ideas of parliamentary democracy, constitutionalism, state secularism, social development, economic growth, techno-scientific advancements, and justice—is what popularly makes postcolonial India a modern and liberal nation-state. That law carries the potential to be violent or unjust is not outside of the liberal imagination. Law in this imagination is a public good that entitles citizens to rights, limits the state’s totalitarian tendencies, and criminalizes those who threaten the polity and the people through their speech or deeds. However, a liberal critique of modern law is mostly concerned with the nation-state’s inability to guarantee access to or strengthen justice-delivery mechanisms, with the nation-state’s acts of overreach into the arena of individual rights like privacy and property, and with the nation-state’s demonstration of ‘softness’ towards thoughts and actions of those considered ‘antinational’. Such a critique is interested in expanding or limiting law for the enhancement and flourishing of the lives of individual citizens (Cole & Craiutu 2018). Of course, who qualifies as the citizen

Preface xxv

deserving of protection from harm by the law has historical roots in liberalism’s violent exclusions of those considered to be in their ‘nonage’ (Mehta 1999; Kapur 2005). For ‘dealing with barbarians’, wrote John Stuart Mill in On Liberty, ‘despotism is a legitimate mode of government […] provided the end be their improvement’ (2002: 8).

The essays in this book question this commonsensical wisdom of the liberal critique to understand law not as the slayer of violence, but as its conduit. What would justice look and feel like if law, as the path to it, is one that authorizes violence—spectacularly and stealthily—in the name of justice? The book engages in a reading of law’s relationship with violence to offer an insight into the cultural imaginaries of justice in the New India—one marked by the combined rise of neoliberalism and Hindutva (Desai 2004; Gopalakrishnan 2006: 2,803–13; Nanda 2009; Teltumbde 2018), which, ‘far from being antagonistic forces [are] actually lovers performing an elaborate ritual of seduction and coquetry that could sometimes be misread as hostility’ (Roy 2019: xvii).7

Law, as matter and metaphor, has been at the heart of the contestations over cultural politics in India today—be it in the struggles for social justice, for holding the state accountable for mass crimes, demanding sexual autonomy for queer people, calibrating experiences of suffering, or the pedagogical practices of citizen-making in the university. The essays step out of the regular venues of legal activity to focus on reading a set of cultural sites—literary texts, Bollywood cinema, documentary films, social media posts, photographs, advertising, and the university—where the law’s promise of emancipation and the performance of violence live a life of intimate paradoxes.

Researched and written between 2008 and 2018, the essays speak to the time of their writing to provide an at once theoretical, activist, and self-reflexive critique of select critical events that have animated the cultural lives of law in the New India.8 I understand culture as the terrain on which legal knowledge is produced that is not solely attached to the sources of modern ‘positivist’ state law—courts, judgements, or legislations. While I engage with these sources, the essays are primarily interested in understanding what happens to the meanings produced by these sources when they enter the negative space of culture, or one of ‘shared meanings’ that are in flux and fossilized at the same time (Hall 2009: 1).