ToJuanitaBrooks

Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.

Be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good.

Romans 12:19, 21

Contents

ListofIllustrations

Preface

PART 1 CRIME

1. The Angel of Peace Should Extend His Wings: SaltLakeCity andMountainMeadows,September11,1857

2. Sermons Like Pitch Forks: NewYorktoUtah,1830‒57

3. Imposed Upon No More: ArkansastoUtah,January‒September 1857

4. Too Late: MountainMeadowstoCedarCity,September12‒13, 1857

PART 2 COVER-UP

5. Forget Everything: SouthernUtah,Mid-September1857

6. The Sound of War: SaltLakeCitytoBeyondtheMuddyRiver, September‒October1857

7. An Awful Tale of Blood: NorthernUtahandSouthernCalifornia, September‒October1857

8. Hostile to All Strangers: EasternUtahtoEasternCalifornia, September‒October1857

9. The Spirit of the Times: SouthernUtahtoSouthernCalifornia, October‒November1857

PART 3 NEGOTIATION

10. A Lion in the Path: Utah;Washington,DC;Arkansas;and Pennsylvania,November1857‒January1858

11. The Mormon Game: NorthernandEasternUtah,November 1857‒January1858

12. Fearful Calamities: Arkansas,Oregon,Utah,andWashington, DC,January‒February1858

13. Peacefully Submitting: SaltLake,CampScott,andSpanish Fork,March‒May1858

14. The Moment Is Critical: SaltLake,CampScott,andProvo, May‒June1858

PART 4 INVESTIGATION

15. Make All Inquiry: ProvoandSaltLake,June1858

16. Join the Know Nothings: NorthernandSouthernUtah,June‒July1858

17. A Line of Policy: SouthernUtah,Arkansas,andWashington, DC,July‒December1858

18. An Inquisition: SouthernUtah,August1858

19. Bring to Light the Perpetrators: NorthernUtah,November 1858‒March1859

20. Nothing but Evasive Replies: NorthernUtah,March‒April1859

21. Diligent Inquiry: SouthernUtah,March‒April1859

22. Approach of the Troops: SantaClaratoNephi,Spring1859

23. Catching Is Before Hanging: SantaClara,May1859

24. Precious Legacies from the Departed Ones: NorthernUtahto NorthwestArkansas,May‒October1859

25. Unwilling to Rest Under the Stigma: EastCoastandUtah,May‒August1859

26. The Course Adopted Will Not Prove Successful: Utah; Washington,DC;Arkansas,June‒August1859

PART 5 INTERLUDE

27. Vengeance Is Mine: SouthernStatesandUtah,1860‒62

28. In the Midst of a Desolating War: WesternUnitedStatesand Washington,DC,1862‒65

29. Too Horrible to Contemplate: Utah,1865‒70

30. Cut Off: UtahandNevada,1870‒71

31. Boiling Conditions: UtahandArizona,1871

32. Zeal O’erleaped Itself: Utah,Arizona,andWashington,DC, 1871‒72

PART 6 PROSECUTION

33. The Time Has Come: Utah,Arizona,andWashington,DC, 1872‒74

34. Do You Plead Guilty: Utah,1874‒75

35. Open the Ball: Utah1875

36. A Means of Escape: Beaver,July14‒19,1875

37. Hope for a Hung Jury: Beaver,July20‒28,1875

38. The Curtain Has Fallen: Beaver,July29‒August7,1875

39. Coerce Me to Make a Statement: SaltLakeandWashington, DC,August1875‒April1876

40. Mr. Howard Gives Promise: Utah,May‒September1876

41. The Responsibility Before You: Beaver,September14‒15,1876

42. Sufficient to Warrant a Verdict: Beaver,September15‒20,1876

PART 7 PUNISHMENT

43. The Demands of Justice: Utah,September‒December1876

44. Allow the Law to Take Its Course: Utah,January‒March1877

45. Under Sentence of Death: BeavertoMountainMeadows,March 20‒23,1877

46. Failure to Arrest These Men: UnitedStates,LateNineteenth andEarlyTwentiethCenturies

47. Haunted: WesternUnitedStatesandNorthernMexico,Late NineteenthandEarlyTwentiethCenturies

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

Notes

Index

Illustrations

1.1. 1.2.

2.1.

23.1.

27.1.

27.2.

29.1.

30.1.

30.2.

32.1.

33.1.

33.2.

33.3.

33.4.

33.5.

33.6.

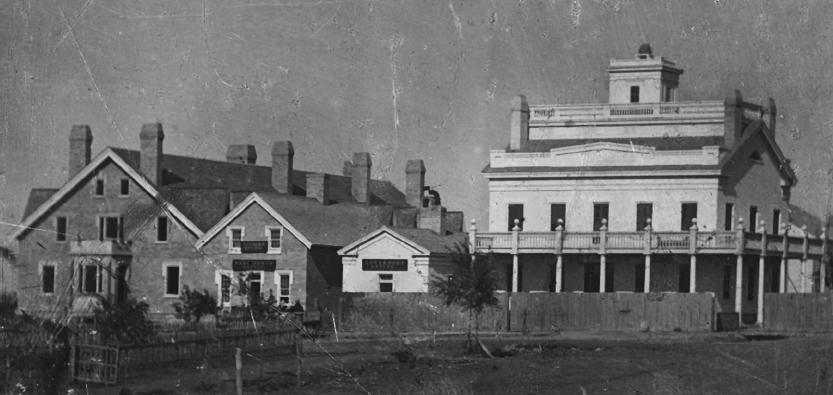

Left to right: Brigham Young’s Lion House, church president’s office, governor’s office, and Beehive House. Courtesy Church History Library.

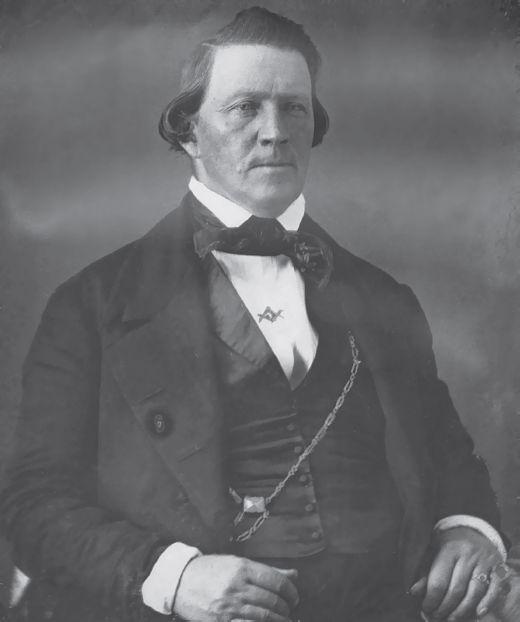

Brigham Young, 1855. Courtesy Church History Library.

Latter-day Saints baptizing Paiutes in southern Utah, 1875. Courtesy Church History Library.

John D. Lee with wives Rachel and Sarah Caroline. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Samuel Clemens. Courtesy University of Nevada, Reno, Special Collections.

The five fingers of Kolob rise above ruins of old Fort Harmony. Wally Barrus, Courtesy Church History Library.

George A. Smith. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Paiute leader Tau-gu (Coal Creek John) and John Wesley Powell. Courtesy American Antiquarian Society.

Men of second Powell expedition. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

John D. Lee family members at home at Jacob’s Pools. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

George W. Adair. Public Domain.

William H. Dame. Public Domain.

Isaac C. Haight. Public Domain.

John M. Higbee. Public Domain.

Samuel Jewkes. Public Domain.

Philip Klingensmith. Public Domain.

33.7.

33.8.

33.9.

37.1.

John D. Lee. Courtesy Sherratt Library, Special Collections, Southern Utah University and Jay Burrup.

William C. Stewart. Courtesy FamilySearch.

Ellott Willden. Courtesy Jay Burrup.

John D. Lee, his legal team, and the judge: Left to right: (seated) William W. Bishop, John D. Lee, and unidentified man; (standing) Jacob Boreman, Enos Hoge, and Wells Spicer. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

45.1.

John D. Lee’s execution. Lee is seated on his coffin left, surrounded by reporters and government officials. To the right are the wagons from which the executioners fired. Courtesy Church History Library.

46.1.

46.2.

46.3.

46.4.

46.5.

47.1.

47.2.

Brigham Young late in life. Courtesy Church History Library.

Kit Carson Fancher. Public Domain.

Sarah Baker Mitchell. Public Domain.

Elizabeth Baker Terry. Public Domain.

Nancy Saphrona Huff Cates. Public Domain.

Nephi Johnson. Courtesy Church History Library.

Juanita Leavitt Brooks. Courtesy Utah State Historical Society.

Preface

On September 11, 1857, a group of Mormon settlers in southwestern Utah used false promises of protection to coax a party of Californiabound emigrants from their encircled wagons and massacre them. The slaughter left the corpses of more than one hundred men, women, and children strewn across a highland valley called the Mountain Meadows.

“Since the Mountain Meadows Massacre occurred,” wrote southern Utah historian Juanita Brooks decades later, “we have tried to blot out the affair from our history.” Brooks believed she was doing her church a service by publishing her landmark book, The MountainMeadowsMassacre,in 1950, maintaining “that nothing but the truth can be good enough for the church to which I belong.” Though no official condemnation of her work came from authorities of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, neither did any recognition.1

Just over fifty years later, historian Will Bagley introduced his own book on the subject, BloodoftheProphets:BrighamYoung andthe Massacre atMountainMeadows, with the criticism that “the modern LDS church wishes the world to simply forget the most disturbing episode in its history.”2

In 2008, agreeing with Brooks’s conclusion that the atrocity “can never be finally settled until it is accepted as any other historical incident, with a view only to finding the facts,” and acknowledging that “only complete and honest evaluation” of the crime can bring true catharsis, we (along with coauthors Ronald W. Walker and Glen M. Leonard) published Massacre at Mountain Meadows.3 The book was a turning point, marking the first time that the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints encouraged its historians to publicly lay

bare this shameful episode in its history. The church’s support of that effort included unfettered access to its previously restricted massacre-related sources and funding for researchers to scour archives and other sources across the United States.

The scope and findings of that research led to reckoning and change. Massacre at Mountain Meadows made its way into the hands of tens of thousands of readers and led church leaders, members, and others to understand and accept “more than we ever have known about this unspeakable episode,” said Latter-day Saint apostle Henry B. Eyring. Speaking to massacre victims’ descendants gathered at a September 11, 2007, sesquicentennial commemoration at the Mountain Meadows, Eyring shared an official apology on behalf of the church.4

Continued reconciliation efforts between the church and organizations of the victims’ relatives resulted in these disparate entities coming together to petition for and receive, in 2011, National Historic Landmark status for the Mountain Meadows, where monuments today memorialize the victims’ final resting place in the valley. “The designation means the United States has recognized that this site is among the most important in U.S. history,” National Park Service historian Lisa Wegman-French declared in a ceremony at the Mountain Meadows.5

All of the sources gathered and used in writing Massacre at Mountain Meadows were made available to the public in Salt Lake City’s Church History Library. Some of the most revealing sources were also published in two documentary histories: Mountain Meadows Massacre: The Andrew Jenson and David H. Morris Collections(2009) and MountainMeadowsMassacre:CollectedLegal Papers(2017).

Yet the efforts that produced Massacre at Mountain Meadows were not complete. As the book’s preface explained, after considering the overwhelming amount of source material gathered, “we concluded, reluctantly, that too much information existed for a single book. Besides, two narrative themes emerged. One dealt with the story of the massacre and the other with its aftermath—one with

crime and the other with punishment. This first volume tells only the first half of the story, leaving the second half to another day.” With the publication of Vengeance Is Mine: The Mountain Meadows MassacreandItsAftermath, that day has come.

As one of the authors and the content editor of Massacre at MountainMeadows, we combined our efforts to coauthor Vengeance Is Mine. We have concluded that the decision to tell the massacre story in two volumes was the right one, as it allowed us to explore the aftermath of the atrocity in greater detail than any previous work. The depth of that exploration has led us to new conclusions that change how the story has been told for generations.

Multiple raids on emigrant wagon trains in Utah Territory, both before and weeks after September 11, 1857, demonstrate that the train massacred at Mountain Meadows was not the only one attacked. These assaults were motivated by political wrangling over federal and local rule and tensions between church and state that reached a deadly peak in 1857 but roiled Utah for decades. Modern readers may recognize similar tensions today, not only in Utah but throughout the United States. This jostling for power between Latter-day Saints and federal authority continued long after the massacre. Attempts to wield the case as a political weapon resulted in justice delayed—and justice denied—for the innocent victims of the massacre and their families.

For generations, the telling of the massacre and its aftermath has been shaped by an 1877 book titled Mormonism Unveiled; or the Life and Confessions of the Late Mormon Bishop, John D. Lee; (Written by Himself). Attorney William W. Bishop published the volume a few months after the execution of his client, John D. Lee— the only man convicted for his role in the mass murder. Mormonism Unveiled went through nineteen printings within fifteen years of its publication and several more modern reprints, demonstrating just how influential this book has been for more than a century.6

Other books and portrayals of the massacre have liberally cited and quoted the words that Bishop claimed to be Lee’s. Based on our research, we conclude that Bishop altered and expanded Lee’s

original and significantly shorter “confession” to publish Mormonism Unveiled. We have therefore not relied on the account that Bishop attributed to Lee in Mormonism Unveiled, but on primary research, including new transcriptions of the original shorthand records of Lee’s two trials and other documents.

With the rare ability to read and transcribe nineteenth-century Pitman shorthand, our colleague LaJean Purcell Carruth created new transcripts of the original shorthand records of John D. Lee’s trials, along with never-before-transcribed passages from other legal proceedings and additional types of records. We cite Carruth’s transcriptions throughout our book. Readers can view the side-byside comparison of her trial transcriptions and the transcriptions made by nineteenth-century shorthand reporters at www.MountainMeadowsMassacre.org, under the “Trial Transcript Archive” tab.

Partly because of their reliance on Mormonism Unveiled, prior massacre historians have concluded that Lee’s trials and conviction were a mere appeasement to justice that closed the massacre case and vindicated church leaders. Our book shows that the pursuit of further convictions continued after Lee’s execution.

From the beginning of this project, our goal has been to make our work approachable for nonacademic readers, not just professional scholars. We believe our decision to tell the story in a narrative style is another reason Massacre at MountainMeadowsreached so many readers. We chose to continue that narrative format in this volume, though with interpretive signposts along the way to share our conclusions based on our decades of researching and writing about the massacre. While Vengeance Is Mine essentially picks up where Massacre at Mountain Meadows left off, the use of flashback and summary—often with new insights—will bring readers up to speed even if they have not read the first volume.

The primary sources we rely on for our book’s narrative reflect some of the erroneous beliefs of their time. While we feel it is important for modern readers to see how these prejudices of the past shaped the Mountain Meadows Massacre and its aftermath, we do not subscribe to them.

Nineteenth-century Euro-Americans did not typically distinguish between the vastly diverse original peoples and nations of the Americas, instead monolithically referring to all simply as Indians. In general, we have used tribal or band names—such as Paiute, Pahvant, Ute, and Shoshone—to identify these groups when we can, using Indian, Native, and Indigenous as synonyms occasionally for variety. Similarly, both Mormon and non-Mormon sources of the era refer to non–Latter-day Saints as gentiles. We find this term objectionable today but use it in the text to reflect nineteenthcentury parlance, in part because the alternative non-Mormon, which we also use for variety, has its downside.

Though this volume, like the first, benefited from extensive research funded by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints History Department, for the past several years we have written Vengeance Is Mine independent of church funding. From start to finish, we have had sole editorial control over our manuscript, and we alone are responsible for its contents.

Richard E. Turley Jr. Barbara Jones Brown

1

The Angel of Peace Should Extend His Wings

Salt Lake City and Mountain Meadows, September 11, 1857

On September 11, 1857, a tall, slender girl approached a pair of offices nestled between two mansions. The elegant structures must have intimidated the sixteen-year-old, who lived her life in roughhewn houses and stone forts. Gathering her skirts and her nerve, she stepped through the door marked “President’s Office.”

As her eyes adjusted to the coolness of the brick-and-plaster interior, she made out several clerk desks. In a ledger labeled

Figure 1.1 Left to right: Brigham Young’s Lion House, church president’s office, governor’s office, and Beehive House. Courtesy Church History Library.

“Sealings Record,” a clerk recorded her name, birthdate, and birthplace: “Sarah Priscilla Leavitt; 8 May 1841; Nauvoo, Illinois.” On the line above, the clerk took down the same information for the man who came in with her: “Jacob Hamblin; 2 April 1819; Ashtabula County, Ohio.”1

Priscilla and Jacob creaked up a staircase to the second story, where they met with the man who was both Utah’s governor and president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, fifty-sixyear-old Brigham Young.2

Priscilla and Jacob clasped hands as Young pronounced the words of their marriage ceremony, which the Latter-day Saints called a “sealing.” When Priscilla accepted Jacob’s proposal weeks before, he gave her the options of marrying in southern Utah, where they lived, or waiting until he could bring her here, to Salt Lake City. She chose this place. Priscilla Leavitt’s marriage was unusual by American standards, but not because of her youth. Rural girls of the day often

Figure 1.2 Brigham Young, 1855. Courtesy Church History Library.

wed by sixteen, sometimes marrying established men who were much older. Priscilla’s marriage was peculiar because Jacob already had a wife.3

At that moment, thirty-five-year-old Rachel Hamblin—whom Jacob called his “kind[,] effctionate companion”—was three hundred miles south in a highland basin called the Mountain Meadows. The year before, Rachel and Jacob had moved their family to the north end of the pristine valley to start a summer ranch.4

The Hamblin and Leavitt families had long been intertwined. Two of Priscilla’s older sisters both married Jacob’s brother William, and Rachel employed Priscilla around the house. In early August 1857, when Brigham Young called Jacob to head his church’s Southern Indian Mission, Jacob chose Priscilla’s brother Dudley as one of his two mission counselors. Rachel chose Priscilla to be not only a “plural wife” for Jacob but also a helpmeet and companion for herself.

“I told them both,” Priscilla said, “that I loved this family well enough to help them, and to give them my love and care. Since Brother Jacob had to be away from home so much on church business and missionary work with the Indians, I felt very humble in accepting this great responsibility.” In polygamous Latter-day Saint culture, a plural wife did not just marry a husband; she married his family.5

As Priscilla and Jacob took their marriage vows at 11:55 a.m., dozens of Mormon militiamen readied themselves for action at the Mountain Meadows, four miles south of the Hamblin ranch. They lined the wagon trail that ran through the valley’s luxuriant grass. The ragtag men faced a circle of besieged wagons some distance from where they stood. Above the encircled wagons, they could make out a white flag, hung from a pole in desperation.6

The militiamen watched as a leader from their ranks, Major John D. Lee, hoisted his own white swag on a stick and walked toward the wagon fort. After a brief negotiation, iron jangled as the emigrants inside removed chains connecting their wagons at the wheels. After their barricade opened, Lee disappeared into the circle with two

other men, both driving wagons. One was Samuel Knight, Jacob Hamblin’s other counselor in the Indian mission. The remaining militiamen outside waited for an hour or more, clutching their guns, sweating in the midday sun, thinking about what they were soon to do.7

That evening in Salt Lake, a newly arrived visitor joined his Latterday Saint hosts for supper. Captain Stewart Van Vliet was a quartermaster for hundreds of U.S. troops headed for Utah. The army had sent Van Vliet ahead with the “ostensible errend . . . to Learn wheather certain Supplies could be procured for the troops ‘enroute’ for this place,” Young concluded, “but it is generally thought that he has been Sent here as a feeler to know & find out the mind of the people.” Young gave Van Vliet his answer: the soldiers must not come into Utah’s settlements. If the troops continued their advance, his people would resist.8

This was not Van Vliet’s first meeting with the Mormons. A decade earlier, he gained their trust when he visited their refugee camps along the Missouri River after mobs drove them from their homes in Illinois. Now, at the September 11 dinner, Van Vliet arose and asked the privilege to speak. “He warmly expressed gratitude for his former and present acquaintance and associations” with the Saints. “His prayer should ever be,” he said, “that the Angel of Peace should extend his wings over Utah.”9

About the same time, near sundown at the Mountain Meadows, Lee, Knight, and several other militiamen arrived at the Hamblin shanty in time for their supper, drawing two wagons to Rachel Hamblin’s door. Though she had heard gunshots throughout the week and “a firing greater than before” earlier that day, Rachel must have been shocked at what she saw in the wagon beds—seventeen blood-stained children, most of them crying. Their hair was tangled and their clothes filthy from what they had endured over the past five days. Seven were infants not yet two years old. The other ten ranged from ages two to six.10

Blood oozed from one toddler’s ear. A one-year-old girl’s left arm dangled by the flesh just below the elbow. The ghastly wound made

one militiaman think she would die. Yet these children were lucky to make it this far. Behind them on the killing fields lay the butchered bodies of their parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. The children in the wagons were all who remained of what had been a bustling train of more than a hundred California-bound emigrants.11

The tear-stained girls and boys, along with two quilts, were pulled from the wagons and passed to Rachel, who was already caring for several children of her own. Some were her stepchildren, some adopted, and three she’d had with Jacob. She could not shield her youngsters from the trauma of seeing the bloodied and wailing little ones. Instead, the older Hamblin children must have helped their mother care for the survivors, who cried in vain for their own mothers. Rachel left no account of how she and some two dozen children at the ranch got through that horrific night. Her adopted Shoshone son, a teenager named Albert, recounted that “the children cried all night.” He never got over the horror of that September 11.12

Outside, in the Mountain Meadows, the militiamen made their own beds under the blackening heavens. John D. Lee unrolled his blanket, laid his head back, and fell into an oblivious sleep.13