Introduction

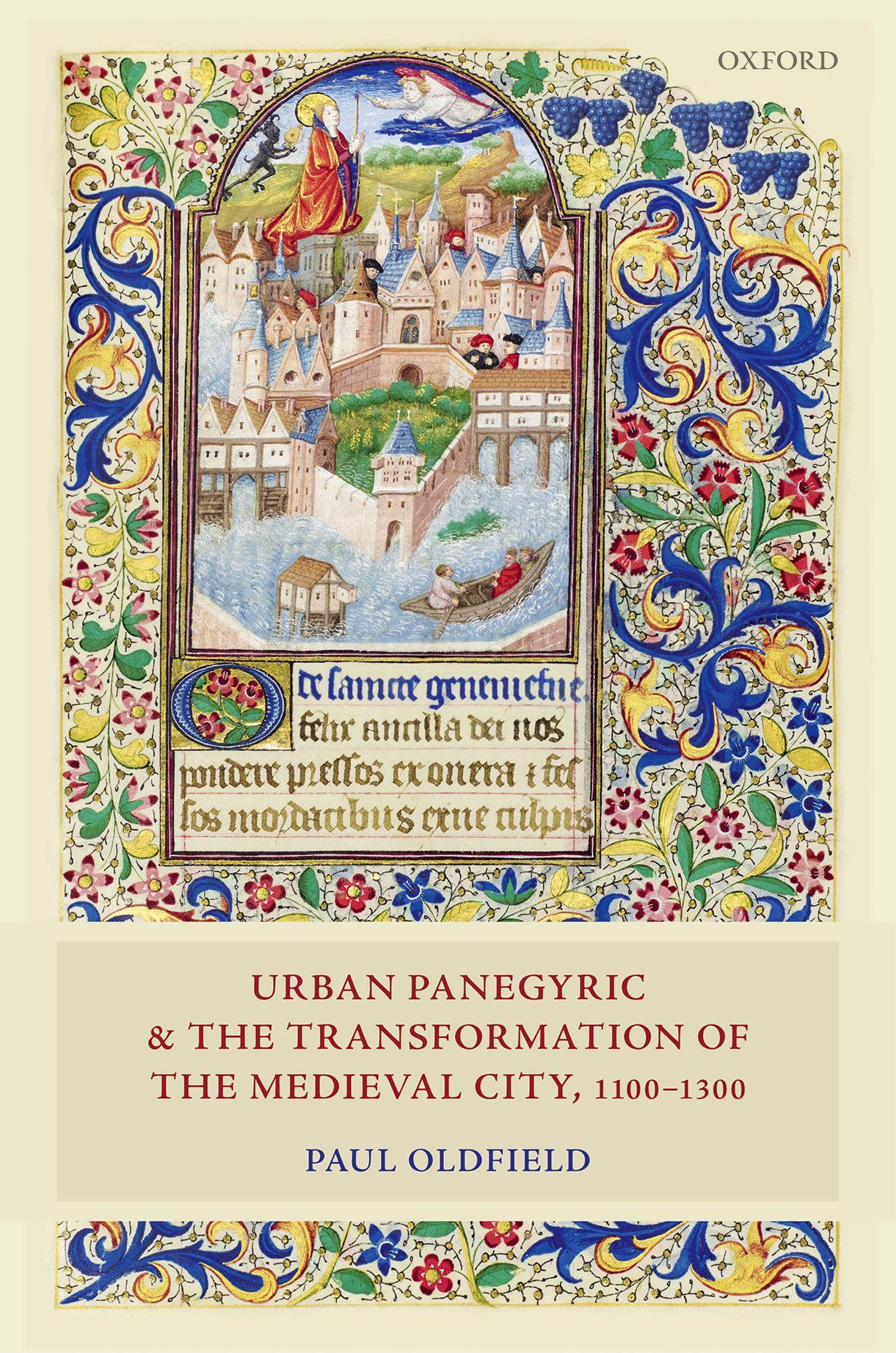

A process of intensive urbanization marked Europe’s twelfth and thirteenth centuries. This much has been abundantly clear ever since Henri Pirenne’s pioneering thesis and the rich and contested historiography it has generated on the history of medieval Europe’s cities.1 If one can question the morphologies, chronologies, continuities, and intensities evident throughout the course of medieval urbanization, the tangible reality of physical change affected in those cities is irrefutable. Demographic, material, commercial, and topographic transformation occurred within cities—in simple terms they became bigger, more influential within wider economic networks, and their layout more complex and more textured—while numerous urban settlements were established ex novo; and these processes reached their apex, or experienced crucial accelerations, roughly during the two centuries running from 1100 to 1300. Consequently, cities could now harness newfound political, commercial, cultural, and military influence which positioned them at the centre of Europe’s map of power politics.

To note, however, that change occurred, and to try to measure it in quantifiable terms (this city’s population doubled, that city built twenty new churches), is to present only half the picture. The other half was an imagined city built on constantly renewable cultural memories, emotions, and affinities; a malleable city which could be more meaningful and intrinsic to an urban inhabitant’s lived experience. Thus, another crucial facet to change and urbanization in our period was the formation of civic consciousness.2 It was underpinned by the rapid growth of urban populations and conurbations and the concomitant competition for resources and status which this aroused among urban centres. This necessitated greater focus on affective conduits for affinities—the language of citizenship, the cultivation of patron saints, the production of civic histories, the construction of civic buildings, and the delineation of more expansive and regularized public spaces, to name but a few—all of which could bind together expanded urban

1 H. Pirenne, Medieval Cities: Their Origins and the Revival of Trade, trans. F. D. Halsey (Princeton, 1925); examples of wide-ranging comparative works on the medieval city include: E. Ennen, Die Europäische Stadt des Mittelalters (Gottingen, 1972); D. Nicholas, The Growth of the Medieval City: From Late Antiquity to the Early Fourteenth Century (London, 1997); K. D. Lilley, Urban Life in the Middle Ages, 1000–1450 (Basingstoke, 2001); P. Boucheron et al., Histoire de l’Europe urbaine. Tome. 1. De l’Antiquité au XVIIIe siècle. Genèse des villes européenes (Paris, 2003); C. Loveluck, Northwest Europe in the Early Middle Ages, c. ad 600–1150: A Comparative Archaeology (Cambridge, 2013).

2 For important, though broad, discussion see: P. Riesenberg, Citizenship in the Western Tradition: Plato to Rousseau (Chapel Hill, 1992), pp. 118–39.

Urban Panegyric and the Medieval City, 1100–1300

landscapes and communities in ways which personal, face-to-face relationships alone could not, and which could project a positive (often imagined) image of the city.

Integral to the generation of civic consciousness was the capability to disseminate its core messages, and in the period post-1100 we see such capabilities put into practice in ways which had arguably not been achieved on such a widespread scale since antiquity. Increased literacy rates and the development of new centres of education, the maturation and expanded aspirations of urban governments, the management of the physical urban landscape, and novel expressions of religious devotion, particularly among the laity, all stimulated more articulate attachments to, and understandings of, the city which attempted to transcend the increasingly eclectic groupings which co-habited the urban landscape. This civic consciousness created appreciation of the positive values connected with the urban world, attached pride to one’s home city, and countered negative, disparaging perspectives on the city. It was nuanced in scholarly circles by exposure to Aristotle’s Politics, which became available once again in the thirteenth century, and also by a deeper engagement with Ciceronian texts which emphasized the unified communitas and its civic obligations.3 Drawing from these ideas, that influential medieval thinker Thomas Aquinas identified the ‘ultimate community’ in the self-sufficient civitas. 4 Thus, identifying and understanding the development of civic awareness opens up the possibility of evaluating what the more fundamental urban transformations of the period meant, in qualitative terms, to some of those who directly experienced them. Crucially, it allows us to assess which aspects of this great phase of urbanization challenged, empowered, bewildered, and defined contemporary city-dwellers, and to evaluate what the city represented to them. And framing the foregoing sketch is the acknowledgement that medieval notions of urban living can continue to question the so-called myth of modernity ‘as a radical break with the past’.5 For civic consciousness in the Central Middle Ages was very much a conscious ‘mode of being’ well before commentators of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—such as the celebrated cultural observer Walter Benjamin—identified ‘civicness’ as an emblem of modernity.6

Civic consciousness is, of course, a more ephemeral entity to identify than a newly built city wall or parish church; it can appear in all manner of guises, often underlying rather than directly defining developments, and its interpretation

3 D. Luscombe, ‘City and Politics before the coming of the Politics: some illustrations’, in D. Abulafia, M. Franklin, M. Rubin (eds), Church and City in the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 41–3.

4 Luscombe, ‘City and Politics’, p. 48; H-J. Schmidt, ‘Societas christiana in civitate: Städtekritik und Städtelob im 12. und 13. Jahrhundert’, Historische Zeitschrift, CCLVII, ii (1993), pp. 333–4.

5 See D. Harvey, Paris, Capital of Modernity (Hoboken, 2013), who prefers to see the formation of modernity less in terms of breaks and more so in ‘decisive moments of creative destruction’ (p. 1).

6 For an overview on Walter Benjamin’s interpretation of the city see G. Gilloch, Myth and Metropolis. Walter Benjamin and the City (Cambridge, 1996), pp. 1–20. A. Butterfield, ‘Chaucer and the Detritus of the City’, in A. Butterfield (ed.), Chaucer and the City (Woodbridge, 2006), pp. 3–22 offers an excellent survey on how Benjamin’s approach can be applied to thinking on the city, and concludes with the observation, important for assessing the medieval city, ‘that modernity is always changing, and has always been there’ (p. 22). See also M. Boone, ‘Cities in Late Medieval Europe. The Promise and the Curse of Modernity’, Urban History, XXXIX (2012), pp. 329–49 for an excellent discussion of the role of the medieval city in scholarly discourses on modernity.

invariably open-ended. Fortunately, many of the key components of civic consciousness were absorbed into, and articulated most vividly by, literary works which offered praise of cities—urban panegyric—which were produced in far greater quantity during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries than at any previous point. Crucially too, the messages within these works of urban panegyric reached a far greater audience than had been the case for comparable forms in the Early Middle Ages. Their material ostensibly addressed the most prominent, laudatory features of urban living, but at the same time tapped into a range of qualitative, quantitative, and functional transformations that were occurring throughout Medieval Europe’s cities so as to serve as commentaries on what the medieval city meant to (at least some of) its inhabitants. Indeed, used reflectively these works also demonstrate what the city was not, or what it should not be, those points on which urban life might be censured. In short they act as cultural texts, a ‘storage medium’ for the construction of cultural memories.7

The present study thus utilizes this vital body of material which has, to my mind, not been sufficiently integrated into studies of medieval urban life. Urban panegyric has often been dismissed as being too bound by convention, rhetoric, and exaggeration and therefore rather sidelined from understandings of the medieval city. The aim of this study is to demonstrate that the messages within urban panegyric are indeed highly valuable ones. It represents the first sustained examination of the content and significance of urban panegyric in the Central Middle Ages. It will connect the production of urban panegyric to two major underlying transformations in the medieval city. It will explore how the physical and functional changes in medieval cities influenced the production of laudatory material on the city and by extension how this shaped civic consciousness. Connected to this, it will ask, vice versa, what that material can reveal about urban transformation. It will also locate the role of urban panegyric in the wider ideological battle which orbited around the concept of the medieval city; one in which new discourses emerged after c.1100 and which contested notions of the evil and the good city.

URBAN PANEGYRIC AND ITS SOURCES

This work aims to track both physical and ideological change associated with the city during the crucial period of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, and uniquely to do so through the prism of urban panegyric, a vastly undervalued textual record which offers a significant voice on these transitions and which has yet to be examined extensively nor fully connected to wider urban transitions. It will provide a wide and comparative geographic analysis, incorporating material on England, Flanders, France, Germany, Iberia, Northern and Southern Italy and Sicily, and (occasionally) the Near East. In Chapter 2 we will discuss at greater length how the material within some of the sources can be interpreted. But it is

7 A. Erll, Memory in Culture, trans. S. B. Young (Basingstoke, 2011), pp. 161–2.

Urban Panegyric and the Medieval City, 1100–1300

important to establish some very broad methodological parameters at the outset, by considering how this study defines urban panegyric.

Urban panegyric appears in many literary shapes and sizes, but simply put, I identify it here as any textual record that can be interpreted as praising (implicitly or explicitly) an aspect of urban life. Thus, for example, seemingly uncomplicated ‘descriptions’ of cities can often be viewed—as will be shown in this study—as implicit praise. At the more explicit end of the scale, at its most formulaic, and arguably most discernible, urban panegyric was influenced by the laus civitatis. This literary template crystallized during Antiquity via rhetorical treatises on the construction of panegyric and encomium which were produced by some of the most renowned rhetoricians and grammarians of the day: Quintilian, Hermogenes, Priscian, and Menander Rhetor to name some of the most important.8 Collectively these works demonstrated ways in which praise could be applied to a city, and their guidance remained influential, not least because its flexibility covered most of the fundamental characteristics of the city in the Middle Ages. Popular subjects for praise included: the origins of a city and the etymology of its name, its physical size, its material legacy (religious and secular buildings; monumental structures such as city walls, towers, and gates; public spaces such as squares, amphitheatres and marketplaces), its wealth and commercial vitality, its geographical situation and layout (including fertility of surrounding lands), the attributes/ achievements of its inhabitants (especially if they were pious, learned, or famous) and (from the Christian era) of its chief patron saints, and the city’s status comparative to other urban centres. The classical influences derived from the early rhetorical texts on urban panegyric were subsequently overlaid by Christian understandings of the city (for more see Chapter 3) to ensure that there were some broader framing devices, agendas, and commonalities which underpinned some of the medieval praise we shall encounter.

An eighth-century Lombard text called De Laudibus Urbium did attempt to aid an author in the production of urban panegyric, and echoes some of the earlier classical rhetoricians:

The first praise of cities should furnish the dignity of the founder and it should include praise of distinguished men and also gods, just as Athens is said to have been established by Minerva: and they shall seem true rather than fabulous. The second [theme of praise] concerns the form of fortifications and the site, which is either inland or maritime and in the mountains or in the plane. The third concerns the fertility of the lands, the bountifulness of the springs, the habits of the inhabitants. Then concerning its ornaments, which afterwards should be added, or its good fortune, if things had developed unaided or had occurred by virtue, weapons and warfare. We shall also praise it if that city has many noble men, by whose glory it shall provide light for the whole world. We should also be accustomed for praise to be shaped by neighbouring cities, if ours is greater, so

8 For an excellent summary of the pre-1100 material see J. Ruth, Urban Honor in Spain. The Laus Urbis from Antiquity through Humanism (Lewiston, 2011), Chapters 1–2.

that we protect others, or if lesser, so that by the light of neighbours we are illuminated. In these things also we shall briefly make comparison.9

The tract then showed the reader how to perform such a comparison. Yet, this type of explicit instruction on the praise of cities was remarkably rare in the Middle Ages. Thus, despite the guidance of classical rhetorical manuals and the evident continuities and recurring themes within aspects of medieval urban panegyric, no linear literary tradition of urban praise developed nor any authoritative taxonomy of laudatory qualities was established. Astrid Erll’s analysis suggests that ‘only when authors and recipients of a mnemonic community share the knowledge of genre conventions [ ] can one speak of the existence of a genre.’10 For the Middle Ages it remains problematic to establish how far authors and audience were explicitly aware of such genre conventions rather than absorbing them at a more subconscious cultural level. For these reasons the present study makes no attempt to delineate nor to offer a definitive model of what constitutes the laus civitatis and urban panegyric in general. Praise within the laus civitatis model could focus on any combination of laudatory attributes, exclude some, and nuance others. The laus civitatis template (and urban panegyric more broadly) is at best a loose category, which in itself demonstrates the variety of ways to praise and conceptualize cities. Each example of praise (and conversely censure) needs to be assessed individually and then comparatively by considering authorship, context, purpose, and type of source, and then, of course, by focusing on the content of the praise itself. Text and context cannot be separated.11

Understandably, the type of distinctive praise which formed extensive passages of texts, or which represent ‘free-standing’ works in their own right, has dominated scholarship on urban panegyric. Some of the most celebrated examples, all of which will be encountered in this study, are the Mirabilia Urbis Romae on Rome (c.1143), William FitzStephen’s description of the city of London, its origins, and its future (c.1173), and Bonvesin da la Riva’s distinguished De Magnalibus Urbis Mediolani on the city of Milan (1288).12 Indeed, J. K. Hyde’s seminal study in the 1960s showcased the importance of many of these works.13 Yet on closer inspection it becomes apparent that these major laudes civitatum are a mixed bag, diverse

9 De Laudibus Urbium, Latin text in G. Fasoli, ‘La coscienza civica nelle “Laudes Civitatum” ’, in her Scritti di storia medievale, ed. F. Bocchi et al. (Bologna, 1974), p. 295 n. 6.

10 Erll, Memory, p. 74. 11 Erll, Memory, p. 171.

12 An edition of the Mirabilia Urbis Romae can be found in Codice topografico della città di Roma, eds. R. Valentini and G. Zucchetti, vol. III (Rome, 1946), pp. 17–65; William FitzStephen, Vita Sancti Thomae in Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, ed. J. Craigie Robertson, Rolls Series, LXVII, vol. III (London, 1877). There is also a translation of FitzStephen’s description of London by H. E. Butler, reproduced in F. Stenton, Norman London: An Essay (Introduction by F. Donald Logan) (New York, 1990), pp. 47–60; Bonvesin da la Riva, De Magnalibus Mediolani (Le Meraviglie di Milano), ed. and trans. P. Chiesa (Milan, 2009).

13 J. K. Hyde, ‘Medieval Descriptions of Cities’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, XLVIII (1965–6), pp. 308–40.

Urban Panegyric and the Medieval City, 1100–1300 in content, purpose, and form.14 Many are embedded in much larger tracts, like the aforesaid description of London which serves as a prologue to William FitzStephen’s Vita of Thomas Becket. In some works too—the Gesta Treverorum for Trier, Boncampagno da Signa’s for Ancona, or Martin da Canal’s for Venice, for example—praise is conveyed implicitly through an entire text which takes a city as its central reference point. The Gesta Treverorum, for instance, has been described quite rightly as written by an author ‘who incorporated into his chronicle everything that contributed to the glory of the Treveri’.15 In others it can be detected indirectly in strategies which enhanced a city’s reputation without applying overt praise, perhaps by simply recording an urban foundation legend which projected the city’s origins into a distant past.16 Furthermore, some works which considered the city as a universal entity and presented that entity in a positive light—such as the Christian philosophers Alain de Lille in the twelfth century and Albert Magnus in the thirteenth—have also been included here as types of urban panegyric.17 All of this reflects the varied forms panegyric could take and the diversity of the textual source types through which it appeared: chronicles, annals, poems, chansons and romances, hagiographies, letters, sermons, legal, political, and theological treatises, customary tracts, and administrative documents.

The approach in the present study therefore recognizes the heterogeneity within the body of works conventionally labelled as laudes civitatum and takes a more holistic interpretation of what constitutes urban panegyric and where to locate it. The corpus of ‘major’ laudes civitatum distract from the considerably larger occurrence of what Elisa Occhipinti termed microlaudes, smaller passages of urban panegyric and description of varied forms and length inserted into larger works.18 Sometimes these may simply be a line or two within a text, sometimes more, but their concision and subtextual implications can be powerful and articulate deeprooted messages. This approach allows us to consider small passages of praise in the same terms, and potentially of the same value, as ‘recognized’/‘major’ laudes civitatum. Thus, to offer two seemingly polarized examples from the thirteenth century, it might be possible to compare and utilize on an equal footing John de

14 D. Romagnoli, ‘La coscienza civica nella città comunale italiana: il caso di Milano’, in F. Sabaté (ed.), El mercat: un món de contactes i intercanvis (Lleida, 2014), pp. 59–62 notes the fluid overlap evident in the so-called mirabilia, itineraria and laudes civitatum genres.

15 W. Hammer, ‘The Concept of the New or Second Rome in the Middle Ages’, Speculum, XIX (1944), pp. 57–8.

16 Gesta Treverorum, ed. G. Waitz, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores, VIII (Hannover, 1848), pp. 130–200; see the important work by H. Thomas, Studien zur Trierer Geschichtsschreibung des 11. Jahrhunderts, insbesondere zu den Gesta Treverorum (Bonn, 1968); and K. Krönert, L’Exaltation de Trèves. Écriture hagiographique et passé historique de la métropole mosellane VIII–XIII siècle (Ostfildern, 2010), pp. 277–87.

17 Alain de Lille, Opera Omnia, ed. J-P. Migne, Patrologia Latina, CCX (Paris, 1855), cols. 200–3; the sermons in which Albert delivered his discourse on the city are edited by J. B. Schneyer in ‘Alberts des Grossen Augsburger Predigtzyklus über den hl. Augustinus’, Recherches de théologie ancienne et médiévale, XXXVI (1969), pp. 100–47 [henceforth: Albert Magnus, Augsburg Sermon Cycle].

18 E. Occhipinti, ‘Immagini di città. Le Laudes Civitatum e la rappresentazione dei centri urbani nell’Italia settentrionale’, Società e Storia, XIV (1991), p. 25.

Garlande’s Parisiana Poetria (c.1231–35), a student textbook on Latin prose and verse, which contains under the section on constructing hyperbole a short sentence on the city of Paris (‘The famous name of Paris reaches to the stars, and its borders contain the human race’), alongside Bonvesin’s aforementioned De Magnalibus Urbis Mediolani, a book dedicated to the praise of the city of Milan and consisting of eight chapters covering the cities virtues: location, buildings, inhabitants, wealth, strength, faith, liberty, nobility.19 John’s praise of Paris, as short as it may be, merely reflects the tip of an iceberg. Below it, submerged, lie numerous literary and cultural traditions and evident links to urban realities which were left unarticulated but believed by the author to be sufficiently understood and resonant to serve as part of a pedagogic tool for local university students. The brief praise of Paris’s hosting of a large and eclectic population taps into some of the oldest literary features of urban panegyric but also speaks directly to thirteenth-century experiences of urban life, as cities (particularly Paris) expanded, became the locus of diverse communities, and their rulers willingly promoted their power through the governance and protection of the mosaic of peoples inhabiting their cities. Bonvesin, on the other hand, might provide far more explicit and explicated praise, but the same background of literary and cultural influences mixed with lived urban experiences suffuses the text. Approached in this way, the issue then is one of degree not type. Similarly, one could compare the often passing, but crucial representations of the city in any number of ‘secular’ and ‘fictionalized’ Epic and Romance works with the extensive, and distinct, prologue of William FitzStephen’s Vita of Thomas Becket which was entitled Descriptio nobilissimae civitatis Londoniae (c.1173).20 In some of the former, for example Jean Renart’s L’Escoufle (c.1200–2), supportive urban inhabitants and the city itself (in this case Montpellier) act as agents enabling the redemption of the chief characters (Aelis and Guillaume).21 Several scholars have demonstrated how these types of works can be used as entry points into the conflicted aristocratic and mercantile perceptions of the city while telling us a great deal about both positive and negative experiences of urban life in the Central Middle Ages.22 In FitzStephen’s work, the description of London is informative and rich, but like L’Escoufle its ‘background’ noises are equally as important (particularly the use of classical authors such as Virgil and Plato, and the imperial claims made for London) as is the juxtaposition of this descriptio with a hagiographical

19 John de Garlande, The Parisiana Poetria of John of Garlande, ed. and trans. T. Lawler (New Haven, 1974), Chapter 6, p. 129: ‘Sidera Parisius famoso nomine tangit, Humanumque genus ambitus Urbis tangit’.

20 William FitzStephen, Vita Sancti Thomae, pp. 2–13.

21 Jean Renart, L’Escoufle, trans. A. Micha (Paris, 1992).

22 J. Le Goff, ‘Warriors and Conquering Bourgeois. The Image of the City in Twelfth-Century French Literature’, in his Medieval Imagination, trans. A. Goldhammer (Chicago, 1992), pp. 151–76; U. Mölk, ‘Die literarische Entdeckung der Stadt im französischen Mittelalter’, in J. Fleckenstein and K. Stackmann (eds), Über Bürger, Stadt und städtische Literatur im Spätmittelalter (Göttingen, 1980), pp. 203–15; M. Harney, ‘Siege Warfare in Medieval Hispanic Epic and Romance’, in I. A. Corfis and M. Wolfe (eds), The Medieval City Under Siege (Woodbridge, 1995), pp. 177–90, emphasizes the broad distinction between epics which presented the knights’ desire to acquire the city against the chivalric romances which showed the knights being absorbed into the city (pp. 187–8).

Urban Panegyric and the Medieval City, 1100–1300 text. Both tell us much about medieval urban identities and the conceptualization of the medieval city.

Thus, the present study will also utilize less well-known, and often shorter, pieces of laudatory and conceptual material. This heterogeneity of source types—which will be set out in more detail in Chapter 1—represents another salient indicator of transformation in the urban world. Through combining this diverse corpus of material it will be demonstrated that the messages within the so-called ‘major’ laudes civitatum were simultaneously far more quotidian and far less generic than had previously been thought, and that some of the seemingly derivative material within them become more meaningful once properly contextualized.

HISTORIOGRAPHY

Fortunately, this study has been able to utilize some key scholarship on medieval urban identities, on literary criticism, on audience and reception, on cultural studies, and on cultural geography.23 It has also drawn on studies from the social sciences to help further understand, for example, the formation of group identities, notions of legitimacy, and interpretations of crowds, all of which shaped medieval perceptions of the city.24 While there exists a huge historiography on the medieval city, scholarship directly on medieval urban panegyric is remarkably meagre. Among the broader (though still regrettably brief) treatments there are, however, several important studies. The aforementioned work by J. K. Hyde played a crucial role in placing medieval works of urban panegyric on the radar of many scholars. While Hyde’s analysis is rather narrow with its approach to city descriptions (descriptiones) which rejected works which he deemed too short or interconnected with another text to be autonomous, it nonetheless presented an important underpinning interpretation:

23 A work which remains fundamental in any discussion of urban identities is S. Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300 (Oxford, 2nd edition, 1997), pp. 155–218; on literary criticism see A. Minnis and I. Johnson (eds), The Cambridge History of Literary Criticism. Vol. 2: The Middle Ages (Cambridge, 2005) and A. Bennett and N. Royle, An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory (Edinburgh, 4th edition, 2009); on literacy, audience, and reception see: J. Tompkins (ed.), Reader-Response Criticism: from Formalism to Post-Structuralism (Baltimore, 1989); D. H. Green, Medieval Listening and Reading. The Primary Reception of German Literature, 800–1300 (Cambridge, 1994); W. J. Ong, ‘Orality, Literacy and Medieval Textualization’, New Literary History, XVI (1984), pp. 1–12; M. Mostert and A. Adamska (eds), Uses of the Written Word in Medieval Towns: Medieval Urban Literacy, II (Turnhout, 2014); Erll, Memory; on cultural geography in a medieval urban context see: K. D. Lilley, City and Cosmos. The Medieval World in Urban Form (London, 2009).

24 For example: M. J. Hornsey et al., ‘Relations between High and Low Power Groups: the importance of legitimacy’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, XXIX (2003), pp. 216–27; D. Waddington and M. King, ‘The Disorderly Crowd: from Classical Psychological Reductionism to Socio-Contextual Theory: the impact on public order policing strategies’, The Howard Journal, XLIV (2005), pp. 490–503; R. M. Chow et al., ‘The Two Faces of Dominance: the differential effect of ingroup superiority and outgroup inferiority on dominant-group identity and group esteem’, Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, XLIV (2008), pp. 1073–81.

The gradual elaboration of descriptive literature from the tenth to the fourteenth centuries represents not so much the growth of a literary tradition as a change in its subject-matter. The medieval descriptiones are a manifestation of the growth of cities and the rising culture and self-confidence of the citizens.

Indeed, for Hyde, prior to 1400 a genuine medieval literary tradition of the laus civitatis ‘was either lacking, or at the best sporadic’, and these works of praise instead tend to ‘reflect successive stages in the fortunes of medieval cities’.25 Later, Occhipinti’s work, although solely examining Italy, suggested a compelling methodological approach to urban panegyric. By acknowledging the importance of (the already noted) microlaudes, Occhipinti highlighted the impossibility of constructing an evolutionary line of development among such works owing to the extreme diversity among the types of sources. Instead, Occhipinti saw greater value in mining these sources for what they tell us about civic self-identity and their representations of the city rather than in attempting to identify an autonomous literary genre with distinct characteristics.26 Aligned to this approach, Harmut Kugler’s study emphasized the need for scholars to recognize the heterogeneity of works praising cities. It acknowledged the value of studying these as literary works but also stressed the importance of contextualizing them within their contemporary urban settings.27 Hyde’s, Occhipinti’s, and Kugler’s methodologies underpin this present study.

Other studies have done a great deal to frame some of the key themes of this study, by elucidating the spiritual and ideological understandings of the city, and highlighting the interrelationship between urban praise and condemnation. Hans Hans-Joachim Schmidt’s masterful analysis of the Christian moralizing and allegorical interpretation of the medieval city in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries makes much of the interplay with fundamental urban transitions, and is complemented by Thomas Renna’s works on Cistercian thinking on the city.28 And Paolo Zanna’s excellent study built a nuanced picture of the classical and biblical legacies framing medieval urban descriptions, and his examination of elegiac works demonstrated their significance for medieval conceptions of the city.29

25 Hyde, ‘Medieval Descriptions’, pp. 308–10.

26 Occhipinti, ‘Immagini’, pp. 25–6.

27 H. Kugler, Die Vorstellung der Stadt in der Literatur des deutschen Mittelalters (Munich, 1986), especially pp. 17–26.

28 Schmidt, ‘Societas christiana’, pp. 297–354; T. Renna, ‘The City in Early Cistercian Thought’, Citeaux: Commentarii cistercienses, XXXIV (1983), pp. 5–19 and ‘The Idea of the City in Otto of Freising and Henry of Albano’, Citeaux: Commentarii cistercienses, XV (1984), pp. 55–72.

29 P. Zanna, ‘Descriptiones Urbium and Elegy in Latin and Vernaculars in the Early Middle Ages’, Studi Medievali, XXXII, 3rd series (1991), pp. 523–96. More focused, localized, examinations have also been produced. A sample would include: Fasoli, ‘coscienza civica’, pp. 293–318; M. Accame Lanzillotta, Contributi sui Mirabilia urbis Romae (Genoa, 1996); D. Kinney, ‘Fact and Fiction in the Mirabilia Urbis Romae’, in É. Ó Carragain and C. Neuman de Vegvar (eds), Roma Felix. Formation and Reflections of Medieval Rome (Aldershot, 2007), pp. 235–52; Ruth, Urban Honor; G. Rosser, ‘Myth, Image and Social Process in the English Medieval Town’, Urban History, XXIII (1996), pp. 5–25; J. Scattergood, ‘Misrepresenting the City. Genre, intertextuality and Fitzstephen’s Description of London (c.1173)’, in his Reading the Past. Essays on Medieval and Renaissance Literature (Dublin, 1996), pp. 15–36; Le Goff, ‘Warriors’, pp. 151–76; Mölk, ‘literarische Entdeckung’, pp. 203–15; Kugler, Vorstellung der Stadt; A. Haverkamp, ‘ “Heilige Städte” im hohen Mittealter’, in F. Graus (ed.), Mentalitäten im Mittelalter (Sigmaringen, 1987), pp. 119–56.

Two additional works require particular mention, however, because they have been important to the present study in addressing specific topics that will be covered here. Carrie E. Beňes’ study on urban origin legends demonstrates the growing interest (in this case in Northern Italy from 1250 to 1350) in civic histories and foundation myths in an increasingly classicizing environment.30 The work will be drawn upon, particularly in Chapter 7, but the way Beňes demonstrated how such legends were projected to a wider audience in several different media supports some of my methodological approaches presented in Chapter 2. Keith Lilley’s monograph likewise combines the abstract with the concrete to show how theoretical conceptions of the city could be mapped onto, and influence the layout of, the physical city, and used to promote the notion of holy cities: this approach will be valuable for the analysis in Chapters 2 and 3 below.31

Perhaps the most salient feature of the entire body of scholarship is the dearth of in-depth book-length studies on a European-wide spectrum. Carl-Joachim Classen produced a welcome and erudite monograph on descriptiones and laudes urbium However, in reality it represents an extended article-length study, half dedicated to the classical period, and the brief examination halts at the twelfth century.32 Chiara Frugoni also offered a thought-provoking examination of the changing concept of the city throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. In combining an analysis of architectural, topographic, iconographic, and textual sources, Frugoni pointed the way towards a more holistic and interdisciplinary approach. That said, as the work proceeds, it becomes increasingly and then (in chapters covering the Later Middle Ages) exclusively focused on Italy.33 There is, therefore, a need for an indepth, methodologically flexible and interdisciplinary approach to this subject, but it has yet to be achieved and very little sustained comparative analysis across medieval Europe has been conducted. The present study aims to offer a small step towards addressing this.

PARAMETERS OF THE STUDY

It is important to acknowledge where this study’s limits lie. First, the very idea of the city has always been a contested subject field. Indeed, the terminology used for urban settlements in the Middle Ages itself was highly fluid and open to various interpretations. The most frequently used label, civitas, reflected ‘a double heritage from Antiquity, a concept of political philosophy and an administrative term’.34

30 C. E. Beňes, Urban Legends. Civic Identity and the Classical Past in Northern Italy, 1250–1350 (University Park, Pa, 2011).

31 Lilley, City and Cosmos.

32 C-J. Classen, Die Stadt im Spiegel der Descriptiones und Laudes Urbium in der antiken und mittelalterlichen Literatur bis zum Ende des zwölften Jahrhunderts (Hildesheim, 1980). See the assessment of Classen’s book in Kugler, Vorstellung der Stadt, pp. 23–4.

33 C. Frugoni, A Distant City. Images of Urban Experience in the Medieval World, trans. W. McCuaig (Princeton, 1991).

34 P. Michaud-Quantin, Universitas: expressions du mouvement communautaire dans le Moyen-Âge latin (Paris, 1970), p. 111.

It represented both the Ciceronian ideal of a city as a community of individuals brought together under the same law, and as an imperial jurisdictional category for an urban centre and its dependent territories.35 In the Early Middle Ages, as bishops invariably took over political and administrative leadership in many postRoman cities, the term civitas also became synonymous with urban episcopal centres. However, other meanings abounded in the Middle Ages. Civitas could imply a walled or fortified centre, a settlement with a legal status recognized in a charter of privileges, an administrative locus, a place of a certain demographic density and physical size, or one with particular commercial and consumer functions. Alongside this, other terms were applied to centres which could appear to have urban characteristics: urbs, municipium, villa, or oppidum could often be used interchangeably with the label civitas. 36 Thus, the ‘richness of the general lexicon’ of the medieval city undoubtedly poses challenges for establishing typologies, particularly when we add in seemingly intermediary terms such as portus, burgus (a term originally connected to a settlement’s military functions), and suburbium, all of which could contain urban associations.37 This terminology likewise varied depending on the education and agenda of the author applying the term.38

For some commentators the city could be the physical entity—its buildings and infrastructure—for others, like the Christian philosopher St Augustine (d.430) it is the inhabitants, or a particular mode of being.

In his Etymologies (c. ad 615–636) Isidore of Seville offered his own influential interpretation of the city:

A city (civitas) is a multitude of people (hominum multitudo) drawn together by a bond of community, named after its ‘citizens’ (dicta a civibus), that is, from the inhabitants of the city (ab ipsis incolis urbis) [. .] Now urbs is the name for the actual buildings, while civitas is not the stones, but the inhabitants.39

Isidore thus echoed the Ciceronian and Augustinian position of the city (civitas) as a community, which dwelled in a particular physical setting, the urbs. Later Christian thinking of the Middle Ages witnessed a partial shift from Augustine’s equation of city with community, to twelfth-century ideas of the city as a ‘place’, in line no doubt with the marked material expansion of many urban centres at this

35 Michaud-Quantin, Universitas, pp. 111–12.

36 Boucheron et al., Histoire de l’Europe urbaine, pp. 287–8; sometimes urbs could denote a city of higher status, connected no doubt to its intrinsic association with the city of Rome: MichaudQuantin, Universitas, pp. 117–19; for specific examples from Normandy see P. Bouet, ‘L’image des villes normandes chez les écrivains normands de langue latine des XI et XII siècles’, in P. Bouet and F. Neveux (eds), Les villes normandes au Moyen Âge. Renaissance, essor, crise. Actes du colloque de Cerisyla-Salle, 8–12 octobre 2003 (Caen, 2006), pp. 320, 327–8.

37 Boucheron et al., Histoire de l’Europe urbaine, pp. 369–70. Burgus/burg became a particularly common urban designation in medieval Germany and to a lesser extent France: F. Opll, ‘Das Werden der mittelalterlichen Stadt’, Historische Zeitschrift, CCLXXX (2005), pp. 567–73.

38 Opll, ‘Das Werden der mittelalterlichen Stadt’, p. 567.

39 Isidore of Seville, Etymologiarum sive Originum libri XX, ed. W. M. Lindsay (Oxford, 1911), vol. II. XV.I.II. My translation slightly adapts the one found in The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville, trans. S. A. Barney et al. (Cambridge, 2006), XV.II.I, p. 305.

Urban Panegyric and the Medieval City, 1100–1300 time.40 Connected to this association with place, the interrelationship with the countryside, as we shall see in Chapter 5, could offer an important framework for defining the city. Rather crude dichotomies might be established between the worlds inside and outside the city wall: the urban as metaphor for ‘civilized’ and the rural for ‘unsophisticated’; the city as ‘haven’ and the country as ‘wild’, or, to turn it around, the ‘corrupt’ city of man versus the ‘moral/simple’ ‘natural’ world; or the ‘chaotic’ city juxtaposed with the solitude and the metaphorical ‘desert’ of the rural.41 The interrelationship was, of course, far more mutually dependent than this, both in Antiquity and in the Middle Ages. At the same time, the revived interest in Aristotle’s Politics in the thirteenth century also ensured that the term civitas retained a broader meaning as the ‘body politic’, an associational interpretation more layered than a simple expression of a location that was urbanized.42 As city laws were developed to consolidate this associational drive so too did the allure of having access to the rights those laws brought. Consequently, from the twelfth century onwards individuals were more willing to self-identify as a civis or its close derivative burgensis to flag up this membership of a civic association with the benefits it might convey, and urban governments were more determined to control who could use the term.

In practice, then, medieval commentators offered nuanced and varied criteria to identify the city.43 The Vita Mathildis (written from 1111 to 1116) by the monk Donizone of Canossa offers one revealing case of a contemporary commentary on what a city should be. His work contained an urbana altercatio between Canossa and Mantua which indicates that several different criteria were all thrown into the mix when conceptualizing the city. In the altercatio, both Canossa and Mantua vie to assert their urban credentials in order to claim the relics of Matilda’s father Boniface. Mantua claims boldly and simply: ‘I am called a city (‘Urbs ego sum dicta’), you, Canossa, are merely a stronghold (‘arx’)’; and ‘nowhere else is it right for such a body to be than in a city’.44 Canossa accepted that Mantua may have the name of city (‘Urbis nomen habes’) but that it could not claim great honour (‘sed

40 M. Richter, ‘Urbanitas-rusticitas: linguistic aspects of a medieval dichotomy’, Studies in Church History, XVI (1979), pp. 152–3.

41 This drew on Aristotle’s position, which was more accessible in the twelfth century, that those who organized themselves within cities could be termed true beings, those outside were not: see C. E. Honess, From Florence to the Heavenly City. The Poetry of Citizenship in Dante (London, 2006), p. 23; J. Le Goff, ‘The Town as an Agent of Civilisation, c.1200–c.1500’, trans. E. King, in C. M. Cipolla (ed.), The Fontana Economic History of Europe, vol. I, Chapter 2 (London, 1971), pp. 6, 12.

42 Luscombe, ‘City and Politics’, pp. 44–5.

43 For discussion of the urban–rural relationship in Antiquity and in the Old Testament in particular, see L. L. Grabbe, ‘Introduction and Overview’, in L. L. Grabbe and R. D. Haak (eds), ‘Every City shall be Forsaken’. Urbanism and Prophecy in Ancient Israel and the Near East (Sheffield, 2001), pp. 30–3 where the author presents the view of an oppositional relationship between city and country in the Middle Ages. For more on the latter see M. Richter, ‘Urbanitas-rusticitas’, pp. 147–57. However, B. Beck, ‘Les villes normandes au Moyen Âge: de la ville réelle à la ville rêvée’, in P. Bouet and F. Neveux (eds), Les villes normandes au Moyen Âge. Renaissance, essor, crise. Actes du colloque de Cerisy-la-Salle, 8–12 octobre 2003 (Caen, 2006), pp. 337–8, argues that separation between town and country was more evident in Antiquity than the Middle Ages.

44 Donizone di Canossa, Vita di Matilde di Canossa, ed. and trans. P. Golinelli (Milan, 2008), Bk. I.VIII, lines 601, 605, p. 58.

non es grandis honore’).45 For Mantua might have many inhabitants (‘populos multos habeas’), but it lacked triumphs because it did not have a circuit wall to protect it.46 Canossa’s fortifications, on the other hand, rendered it impregnable.47 Mantua responded that it had a marvellous church, bishop, priests, and many venerated relics; Canossa claimed in turn that its own direct dependence on the papacy conferred freedom and higher nobility.48 The remainder of the altercatio then shifts to Canossa’s efforts to deny Mantua an esteemed classical heritage by refuting the latter’s claim to be the birthplace of Virgil. The altercatio ends with an apparent victory for Canossa, but it seems a hollow one, and indeed Canossa ‘commands’ Mantua to keep Boniface’s relics.49 Thus, the recognition of the city here was identified variously with its materiality, its inhabitants, spirituality, cultural esteem, and heritage. Another example can be found in the sermons of the great thirteenthcentury philosopher Albert Magnus, who combined several criteria within his potent neo-Platonic/Augustinian emphasis on the city. Albert identified its four quintessential characteristics thus: fortification (munitio), sophistication (urbanitas), unity (unitas), and liberty (libertas).50

More modern, but contested, definitions of the city, as can be seen in Lewis Mumford’s influential commentary of 1937, broadened the measures notably: ‘The city in its complete sense, then, is a geographic plexus, an economic organisation, an institutional process, a theater of social action, and an aesthetic symbol of collective unity’.51 Medieval historians of the twentieth century continued to set out the varied criteria for defining the medieval city: from Rodney Hilton’s preference for occupational heterogeneity as one of the main markers of the urban to Jacques Le Goff’s compelling association between the number of Mendicant convents and the size and wealth of a city.52 But the careful treatment of the issue by medievalists further demonstrates how difficult and indeed misleading it could be to present a single, monolithic definition of ‘city’ or ‘urban’. In truth, not one of the multiple ways of categorizing the city is fully satisfactory and deserves privileging. All the ‘cities’ in this present study were identified at some point in the Middle Ages as either a civitas, urbs, municipium, villa, or oppidum. Encapsulated

45 Donizone di Canossa, Vita, Bk. I.VIII, line 606, p. 58.

46 Donizone di Canossa, Vita, Bk. I.VIII, lines 607–14, p. 58.

47 Donizone di Canossa, Vita, Bk. I.VIII, lines 618–32, p. 60.

48 Donizone di Canossa, Vita, Bk. I.VIII, lines 638–75, pp. 60–2.

49 Donizone di Canossa, Vita, Bk. I.VIII, lines 679–748, pp. 64–8.

50 Albert Magnus, Augsburg Sermon Cycle, pp. 100–47 (quote at p. 105). For a similar Augustinian view of the city, but different in some of its salient facets, see the ideal city proposed by William of Auvergne, bishop of Paris (1228–49): J. Le Goff, ‘An Urban Metaphor of William of Auvergne’, in his Medieval Imagination, trans. A. Goldhammer (Chicago, 1992), pp. 177–80.

51 L. Mumford, ‘What is a City?’, Architectural Record (1937), reproduced in R. T. LeGates and F. Stout (eds), The City Reader (London, 2011), p. 93. For a survey of the sociological approach to cities see B. D. Nefzger, ‘The Sociology of Preindustrial Cities’, in L. L. Grabbe and R. D. Haak (eds), ‘Every City shall be Forsaken’. Urbanism and Prophecy in Ancient Israel and the Near East (Sheffield, 2001), pp. 159–71.

52 R. H. Hilton, English and French Towns in Feudal Society: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, 1992), especially pp. 6–7, 33, 152; J. Le Goff, ‘Ordres mendicants et urbanisation dans las France médiévale’, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, XXV (1970), pp. 924–46; See also J. B. Freed, The Friars and German Society in the Thirteenth Century (Cambridge, MA, 1977), p. 52.

Urban Panegyric and the Medieval City, 1100–1300

within these terms was a spread of political, legal, religious, material, military, and economic functions, with different authors/works emphasizing some of these functions over others.53 The ensuing study should then at least offer the reader several angles through which to see how flexible these definitions of the city could be, and to consider some of them as they might apply in the Middle Ages.

The chronological parameters of this work, 1100 to 1300, inevitably impose certain artificial boundaries. Comparable works interlinking with comparable urban developments of course existed before and after these dates, and consequently we will sometimes move earlier and later in time. However, the overwhelming rise in output in works of urban panegyric and the most intense phase of medieval urbanization correlate primarily with the twelfth and thirteenth centuries and this period therefore remains the focus of the study. Also, as already pointed out, comparative analysis is fundamental to this work in order to move beyond the more localized studies. The present study therefore attempts to utilize as wide a range of source types as applicable and spread them as evenly as possible both chronologically and geographically. In doing so, I hope to strike a balance between breadth and depth, offering some more intensive analyses on particular works and cities, while keeping in mind the universality or the uniqueness of patterns and differences which might well be missed if we focused on a more narrow body of texts. At the same time, conversely, there is a lack of source coverage for many of Europe’s medieval cities. For some cities we have very little material, for others only one or two works which arguably provide momentary snapshots. In some cases—for the Flemish cities of Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres—the near silence in our source records for this period is both astonishing and surely significant. In other words, there are inevitably chronological and geographical gaps in this study, and there are equally source hotspots—Italy obviously—which we cannot and should not avoid.

URBAN TRANSFORMATION, 1100–1300:

THE BACKGROUND

Before setting out the plan of this book we should also make the important point that, while the work does not follow a chronological analysis, some of the salient themes in this study and the nature of the sources themselves experienced change over time, and this will be teased out in places. Most cities in 1300 looked different and were doing things differently to those of 1100. This must be kept in mind, with the obvious caveat that our picture must surely be distorted by the greater quantity of evidence available as we move towards the latter date. Each thematic chapter will contextualize and highlight this more fully, but it will be useful here

53 All three labels, particularly, urbs and civitas, were often used interchangeably, but sometimes urbs could denote a city of higher status, see Michaud-Quantin, Universitas, pp. 111–19 and for specific examples for Normandy see P. Bouet, ‘L’image des villes normandes chez les écrivains normands de langue latine des XI et XII siècles’, in Bouet, ‘L’image des villes’, pp. 320, 327–8.

in at least the broadest of brush strokes to remind ourselves of some of the most significant aspects of urban growth and then revisit them in subsequent chapters. Above all, after 1100, cities were shaped by a rapid rise in population, stimulated by rural migration, climatic change, and the revival of the economy, which centred wealth in cities, and this in turn attracted further migrants. Figures for medieval urban populations are notoriously problematic, and growth could be uneven and hit temporary downturns through plague and war, but by the mid-to late thirteenth century some truly large cities had emerged. Several Italian cities may have had populations above 100,000, such as Milan (perhaps even as high as 150–200,000), Florence, Venice, Naples, and Palermo.54 Recent estimates suggest a population of around 80–100,000 for London in 1300, and perhaps an even higher figure for Paris.55 Rome’s population, and numerous other cities—Bruges, Cologne, Montpellier, Rouen, Seville—may have reached somewhere in the region of 40–50,000 by 1300.56

Yet the most important statistic is the one on relative growth—most cities of all ranks in Europe appear to have doubled in size at some point between the start of the twelfth and the end of the thirteenth century, whether it be a York expanding from c.8,000 in 1086 to c.23,000 in c.1290, or a Padua from c.15,000 in 1174 to c.35,000 in 1320.57 And this level of relative growth is of course to be amplified in those cases where ‘new’ cities were founded, a phenomenon which peaked in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.58 Most cities expanded beyond their original footprint during this period, establishing extra-mural suburbs, or even incorporating them in newly expanded circuits of city walls, as occurred most spectacularly at Florence in the thirteenth century.59 Cities consequently underwent a physical transformation in line with commercial revival and Church reform. The twelfth and thirteenth centuries was therefore an era of intensive urban construction. New shrine centres, cathedrals, and religious complexes, like Santo Stefano at Bologna, city walls, gates and towers, and guildhouses marked a new urban skyline. Distinct secular spaces also re-emerged, pioneered in thirteenth-century Italy with communal palace complexes and public piazzas. At a more quotidian level, multi-storey buildings and subdivided tenements became more common, as did stone housing,

54 See E. Hubert, ‘Le construction de la ville: sur l’urbanisation dans l’Italie médievale’, Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales, LIX (2004), pp. 109–19; for the debates on Milan’s population see P. Grillo, Milano in età comunale (1183–1276): istituzioni, società, economia (Spoleto, 2001), pp. 39–41 and P. Racine, ‘Milan à la fin du XIII siècle: 60,000 ou 200,000 habitants?’, Aevum, LVIII (1984), pp. 246–53; see also the brief but useful survey, Nicholas, Growth of the Medieval City, pp. 178–82.

55 S. Rees Jones, York: The Making of a City, 1068–1350 (Oxford, 2013), pp. 236–7; B. M. S. Campbell et al., A Medieval Capital and Its Grain Supply: Agrarian Production and Distribution in the London Region, c.1300 (Cheltenham, 1993), pp. 8–11.

56 C. Wickham, Medieval Rome: Stability and Crisis of a City, 900–1150 (Oxford, 2014), p. 112; Nicholas, Growth of the Medieval City, pp. 178, 180.

57 Rees Jones, York, p. 236; Nicholas, Growth of the Medieval City, p. 182.

58 The classic work remains M. Beresford, New Towns of the Middle Ages: Town Plantation in England, Wales, and Gascony (London, 1967); see more recently Lilley, City and Cosmos, especially pp. 41–73.

59 See the work of F. Sznura: L’espansione urbana di Firenze nel Dugento (Florence, 1975) and ‘Civic Urbanism in Medieval Florence’, in A. Molho, K. Raaflaub, and J. Emlen (eds), City States in Classical Antiquity and Medieval Italy (Stuttgart, 1991), pp. 403–18.

Urban Panegyric and the Medieval City, 1100–1300

funded by newly rich merchants and artisans.60 These stone houses reflected both status and the need for protection stimulated by the growth of urban populations and the density of housing constructed in flammable materials. Stone housing, and the development from c.1200 of civic building regulations to ensure stone party walls, thus served as a means for the more wealthy to protect property and merchandise against fire and urban disorder.

And, as a result of migration and trade, most urban populations by 1300 were more diverse in background and composition (and more transient) than they had been in 1100. It should be no surprise that, against this backdrop, cities began to define membership of the urban community more closely. But such was the social fluidity that in reality cities ‘tolerated several citizenships’, with gradations of legal rights and obligations functioning within them.61 In sum, the twelfth and thirteenth centuries represented one of the most intense and complex periods of population growth in European history prior to the nineteenth century, and witnessed significant transformation in urban social ordering and city topographies.

Concomitant to this demographic expansion was the commercial revival of the Central Middle Ages. By 1100, mercantile and artisanal groups were certainly prominent features of the urban landscape, but by 1300, guilds and confraternities had formed around many of these merchant and specialized craft groups, projecting conspicuous wealth and influence through rituals, festivities, monumental buildings (such as the aforesaid stone houses and towers), and also, in some cases, claiming political power in urban government.62 In line with the commercial boom, markets became ever more the focal point of urban communities and were regulated more strictly. As the thirteenth century progressed, improved farming techniques saw bigger surpluses in urban hinterlands reaching city markets. The development of international trading fairs and networks, aided by the expansion of Latin Christendom’s frontiers, also saw luxury goods from distant lands appear in cities, along with more and more foreign merchants, who in some cases established mercantile enclaves in their host cities. Underpinning these transformations, by the late thirteenth century, Europe’s urban economies were highly monetized and technically more sophisticated through the introduction of systems of credit, insurance, bills of exchange, and banking facilities. Historians quite rightly see the thirteenth century as the point at which a true profit economy, rooted in cities, emerged in Western Europe and as a period in which a new focus on numbers and data came to the fore.63

Equally, urban governments were ruling in a very different manner by 1300. Two centuries earlier, many urban governments—especially in Italy—were starting to develop embryonic communal institutions, or at the least urban elites were aspiring to a more prominent role in the government of their own cities. Over the course of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, several cities—not just in Northern

60 Hubert, ‘construction de la ville’, pp. 121–2. 61 Riesenberg, Citizenship, p. 111.

62 Loveluck, Northwest Europe, pp. 302–27, 328–60.

63 See L. K. Little, Religious Poverty and the Profit Economy in Medieval Europe (Ithaca, 1978); A. Murray, Reason and Society in the Middle Ages (Oxford, 1978), pp. 180-7; Romagnoli, ‘coscienza civica’, pp. 69–74.

Italy, but to lesser degrees in England, Iberia, France, Flanders, and Southern Italy—had attained a much higher level of self-government, either through formal communal bodies, or via more informal agreements with higher authorities. Indeed, these centuries witnessed a surge in associational movements—communes, guilds, and confraternities—all of which developed their own norms of social action and political practice.64 Even if numbers remained restricted and processes could hardly be described as democratic within these associations, a greater proportion of urban inhabitants in Europe could play a role in urban government than had been the case in 1100. And urban governments were becoming ever more interventionist as their administrative complexity and capabilities crystallized. Civic councils, again pioneered in Italy but echoed elsewhere, took more interest in their urban hinterlands, in taxation, in the urban environment (both aesthetically and functionally), in justice, in commercial enterprise, and in external military policy.65 The new demographic and commercial wealth of cities had assisted greatly in this process. Urban social hierarchies became more fluid too, with certain kin-groups able to utilize new forms of liquid wealth and social esteem to rise to prominence. By the same process, established elite families could rapidly lose their status, and no wonder that the motif of Fortuna and her Wheel—signalling the cyclical rotation of success and failure—was so resonant in the Central Middle Ages.66 This should remind us of the fragility of wealth, the limitations of urban welfare support, and the omnipresent spectre of poverty in medieval cities.

The development of more intensive urban governments which were simultaneously more accessible to a wider body of the urban populace also generated a deleterious by-product: urban faction and conflict. New constellations of power formed within cities, they could be based around professions, migrant communities, religious, landed and mercantile communities, and even by city quarter. As cities acquired greater power, so that power became ever more contested. This could be internal: urban uprisings blighted the Italian communes, especially in the thirteenth century, but they were a feature of most cities in our period. And it could be external: cities were coveted by higher authorities, kings and emperors, for their wealth and political and military potential. Cities might pull away from those higher authorities, or conversely become entangled in higher power politics and consequently find themselves attacked and conquered. From the mid-twelfth century onwards many monarchies were visibly constructing more centralized and powerful administrative states—above all in England (though of course here the ‘centralized state’ was already a prominent feature in the eleventh century), France,

64 For an excellent study see: O. G. Oexle, ‘Peace Through Conspiracy’, in B. Jussen (ed.), Ordering Medieval Society. Perspectives on Intellectual and Practical Modes of Shaping Social Relations, trans. P. Selwyn (Philadelphia, 2001), pp. 285–322.

65 F. Bocchi, ‘Regulation of the Urban Environment by the Italian Communes from the Twelfth to the Fourteenth Century’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, LXXII (1990), pp. 63–78.

66 R. L. Greene, ‘Fortune’, in J. R. Strayer (ed.), Dictionary of the Middle Ages, vol. 3 (New York, 1985), pp. 145–7 and also the discussion in the introduction of ‘Hugo Falcandus’, The History of the Tyrants of Sicily by Hugo Falcandus, 1153–69, trans. G. A. Loud and T. E. J. Wiedemann (Manchester, 1998), pp. 37–8.