1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© The Winnicott Trust 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–094963–1

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Preface

Amal Treacher Kabesh

Acknowledgments

Contributors

1. The Enduring Significance of Donald W. Winnicott: General Introduction to the Collected Works 1

Lesley Caldwell and Helen Taylor Robinson

2. From Pediatrics to Psychoanalysis, 1911–1938

Ken Robinson

3. “Two makes one, then one makes two”: Early Emotional Development, 1939–1945

Christopher Reeves

4. Towards Different Objects, Other Spaces, New Integrations, 1946–1951

Vincenzo Bonaminio and Paolo Fabozzi

5. Reading Winnicott Slowly, 1952–1955

Dominique Scarfone

6. Reaching His Peak, 1955–1959

Jennifer Johns and Marcus Johns

7. Health: Dependence Towards Independence, 1960–1963 107 Angela Joyce

8. Object Presence and Absence in Psychic Development, 1964–1966 129 Anna Ferruta

9. Communication Between Infant and Mother, Patient and Analyst: The Years of Consolidation, 1967–1968 147

Ann Horne

10. Being, Creativity, and Potential Space, 1969–1971

Arne Jemstedt

Armellini

Groarke

{ Preface }

Amal Treacher Kabesh

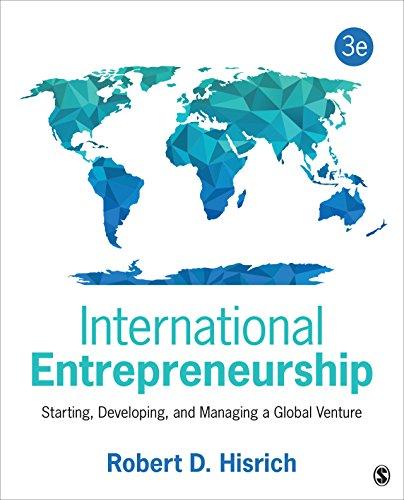

The essays assembled in this book were first published as the introductions to eleven of the volumes that make up The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott (published by Oxford University Press in 2016, print and online). Initially, it was Clare Winnicott’s aspiration and hope that Winnicott’s works (publications, audio recordings, correspondence) would be gathered together to be available in one collection. The General Editors—Lesley Caldwell and Helen Taylor Robinson— have achieved this ambition under the auspices of the Winnicott Trust.

It was then decided to group these introductory essays into one further book as they provide a textured map of Winnicott’s oeuvre and elucidate both theoretical development and clinical practice. They represent a major contribution to Winnicottian scholarship; written by renowned international Winnicottian scholars, they offer in-depth framing and discussion of Winnicott’s conceptualizations of human beings and of psychoanalytic practice. Each essay covers a different period of Winnicott’s life; the dates are indicated at the beginning of each contribution.

The essays published in this volume are very close to the original introductions except in one respect—repetitive biographical detail has been deleted from the original scripts or shifted into the section that furnishes biographical detail in the essay by Caldwell and Taylor Robinson (Chapter 1 in this volume). Where there is a divergence in opinion, then the original biographical account is retained. The full references to the Collected Works are included in this edition.

The 12 volumes of the Collected Works comprise previously published work along with previously unpublished texts. Each volume is presented chronologically according to date of delivery, or writing, or of first publication. The various drafts of Winnicott’s work are also included to illustrate the development and interplay of an idea. This inclusion of the drafts provides a fine illustration of Winnicott’s willingness to develop, refine, and reflect on his ideas and clinical practice. The Collected Works is thus ordered chronologically; the known date of composition or first presentation takes priority over the date of first publication. Robert Adès explains the order as follows: the chronological bibliography, following American Psychological Association style, is ordered exclusively by the

year of first publication. Accordingly, a work’s position in the bibliography does not always correspond to the location of the item in the Collected Works. In cases where this differs, the date of composition—and hence the publication’s location in the Collected Works is given in square brackets after the title. Uncertain or estimated dates have been indicated with “c.”—when some estimation is possible— and otherwise marked “not dated” [n.d.]. Any further information on the history of a work’s composition and publication, along with other pertinent information, can be found in its headnote. The introduction to Volume 12 authored by Robert Adès serves to provide a map to the Collected Works and, therefore, has not been included in this volume. It is accessible online.

The Collected Works opens with a detailed introduction written by Lesley Caldwell and Helen Taylor Robinson. This rich essay appears as Chapter 1—“The Enduring Significance of Donald D. Winnicott: A General Introduction to the Collected Works”—in this volume of essays and provides a multifaceted exploration of Winnicott’s progressive elaboration of his theoretical and clinical positions. Caldwell and Taylor Robinson present the intellectual and institutional context of Winnicott’s development into a major and significant analytic figure, elucidating key concepts such as creativity, the necessity of illusion, transitional objects and transitional phenomena, fantasy, and the psyche-soma. Winnicott was centrally preoccupied with what is required to develop a healthy self that is able to engage with the world with liveliness and authenticity. This essay offers a sustained discussion of Winnicott’s “clinical directions.”

Ken Robinson’s essay in Chapter 2, “From Pediatrics to Psychoanalysis,” provides a detailed and cogent account of Winnicott’s education as a medical doctor and his growing engagement with psychological matters. Robinson’s detailed account of the early years of Winnicott’s work (1911–1938) traces through the various influences (individuals, concepts, clinical practice) on Winnicott’s education. (Robinson points out that Winnicott preferred the word “education” to “training.”) Importantly, Robinson highlights Winnicott’s commitment as a pediatrician and as a psychoanalyst.

Christopher Reeves discusses Winnicott’s theoretical development during the period 1939 to 1945 in Chapter 3, entitled “ ‘Two makes one, then one makes two’: Early Emotional Development” (this chapter is dedicated to Christopher Reeves, who sadly died before the volumes appeared in print). He reminds the reader of the context of World War II, the conflict in the British Psychoanalytical Society (commonly referred to as “the Controversial Discussions”), and Winnicott’s increasing disagreements with Melanie Klein’s theoretical propositions, as all influencing Winnicott’s developing theoretical perspectives. Winnicott conceptualized the infant and mother as a unit that should be understood as “two makes one, then one makes two” as the mother and baby are to be regarded as a psychic unit and then become separated though still united.

During this period Winnicott pays increasing attention to “hate” as a powerful emotion that is felt and experienced by all human beings. Hate is discussed

thoroughly in Chapter 4, “Towards Different Objects, Other Spaces, New Integrations,” by Vincenzo Bonaminio and Paolo Fabozzi. Bonaminio and Fabozzi open their essay thus: “Hate. This is the first time that a feeling bursts into psychoanalytic discourse with such disruptive effect on the metapsychological terrain,” and thereby they equally bring the force of emotion upfront as they simultaneously explore how Winnicott also disrupted psychoanalytic discourse as he argued for the persistent strength of emotions. Movement is a theme in this chapter as Bonaminio and Fabozzi trace through the various conceptual shifts (theoretical and clinical) that Winnicott undertakes during the years 1946 to 1951.

In Chapter 5, Dominique Scarfone advocates “Reading Winnicott Slowly” in order to understand fully the complexities and movements of Winnicott’s thinking. Scarfone points out that for Winnicott it is important to speak the truth of one’s thoughts without compromise; in upholding this ideal, Scarfone understands Winnicott as close to Freud’s spirit in not being compliant or adhering to the prevalent norms within psychoanalytic groups. During this period (1952–1955), Scarfone writes, Winnicott “appears as formidably alive and in constant motion, treating patients, writing papers, discussing those of others, writing letters to medical journals and newspapers, all with a profound sense of devotion towards whatever truth can be discovered by sound psychoanalytic practice and rigorous thinking.”

In Chapter 6, “Reaching His Peak,” Jennifer Johns and Marcus Johns place emphasis on Winnicott’s theoretical and clinical influence. They argue that Winnicott the person is the same as Winnicott the theoretician and clinician. Winnicott had found his own idiom, and this led to a growing divergence of opinion between him and Melanie Klein. While Winnicott agreed with the “ubiquity and importance of envy in the analysis of adults and children,” his view was that ego-integration was in the process of development. Jennifer Johns and Marcus Johns clarify Winnicott’s understanding that envy found in adults and children is a result of what has taken place during the processes of ego-integration, individuation, and maturation. The child responds with a degree of envy due to the legacy of the mother’s capacities to respond, recognize, and adapt. Critically, envy in a Winnicottian frame is understood as a response to the environment and is not an innate essence. From the early 1950s onwards, Winnicott was concerned with the various ways a child discovers reality, explores the complex interrelationships between self and other (the me and not-me), and begins to uncover fantasy and reality, and the use of objects by the developing infant. In short, recognition as a capacity and as a process that is always in process becomes central to Winnicott’s understanding of what it is to be human.

Angela Joyce, in Chapter 7, “Health: Dependence Towards Independence,” explores Winnicott’s theoretical developments during the period 1960 to 1963. She writes that Winnicott was a theoretician of health as he was concerned to elaborate the possibilities of living and being truthful. As is well known, Winnicott paid subtle attention to the difference between the real (authentic) self and the false (compliant) self. It is when there are too many impingements, too many

demands to adapt to the environment, and when there are too many failures of a good-enough environment, that the infant retreats into helplessness and despair resulting in a compliant and false self. Alongside developing his ideas about the real and false self, Winnicott was developing his conceptualization of the infant’s necessary moves from absolute dependency to relative dependence and then finally towards independence. Winnicott did not believe that any human being was ever fully independent—but we can reach towards independence.

Winnicott was not willing to imbibe and repeat unthinkingly the canon of received psychoanalytic theory, as is illustrated in Anna Ferruta’s essay in Chapter 8, “Object Presence and Absence in Psychic Development.” Ferruta expounds the development of Winnicott’s thinking during 1964 to 1966, and she explores how an extraordinary range of topics and a “courageous extension” of his thinking into primitive areas of the mind characterize his work. The volume of the Collected Works that this piece introduces (Volume 7) includes a range of his essays that both bring together his preoccupations and deepen our understanding of aspects of being human: integration, movement across emotional states of mind, the integration of the ego, and the treatment of borderline and psychotic patients. Winnicott was convinced that integration starts at once for the infant despite dependency on primary caretakers. Failure of integration, or disintegration, were cause of profound concern for Winnicott, and he thought through the cause and effect of these states of mind with sensitivity and compassion. The matter of integration and the expression of individuality is a theme that runs throughout his work. Winnicott argued persistently that the task of the clinician is to be available to the patient. The clinician is there to meet the transference, to give voice to unexpressed feelings and fantasies—in short, to be of service to the patient. As Ferruta points out, the material contained in Volume 7 of the Collected Works illustrates “Winnicott’s wish to maintain his independent way of thinking while trying to avoid seeming intolerant or detached.”

In 1967 and 1968, Winnicott consolidated his thinking on technique, the task of the analyst, nonverbal communication and possible mutuality of experiences between mother and infant, use of gaze, and the mother’s capacity to adapt to her infant’s needs. For Winnicott, it is from mothers and babies that much can be learned about the needs of psychotic patients. The importance of reliability is a theme that Winnicott stresses persistently, and he emphasizes that when reliability breaks down, which it inevitably does, then unthinkable anxiety overwhelms the infant. He perceives annihilation as a catastrophe that occurs as a result of extreme anxiety and primary privation. The task of the analyst, Winnicott insists, is to attend to the primitive developmental needs of his patients. His thinking about the intermediate area of experience—fluidity between internal and external— leads for Winnicott to play, to creativity, to culture itself. Psychoanalysis itself is, for Winnicott, a specialized form of play. Ann Horne’s lucid contribution in Chapter 9, “Communication Between Infant and Mother, Patient and Analyst: The Years of Consolidation,” provides a useful synopsis of Winnicott’s achievements

that were consolidated and enhanced during these two years. Horne sums these up as follows: how the infant arrives at a separate sense of self and other; the perception of reality and the object as real; delinquency as hope; the reliable environment; and playing and culture.

In his essay in Chapter 10, “Being, Creativity, and Potential Space,” Arne Jemstedt expounds a number of ideas that were of crucial significance to Winnicott: creativity and the creative process, being, illusion, and transitional phenomena. Jemstedt draws our attention to Winnicott’s important paper “Communicating and Not Communicating Leading to a Study of Certain Opposites” (published in Volume 6:4:8). In this paper, Winnicott argues that at the core of every human being is a silent communication, a sacred area, and crucially it is an aspect of health and an important aspect of being alive. This is a Winnicottian paradox as it is from this silent core that itself cannot (indeed, should not) be communicated that communication occurs. Paradox abounds in Winnicott’s understanding of human beings and human lives as we strive to communicate and simultaneously keep our core silent and hidden; the baby creates and finds the object; we live in illusion and simultaneously inhabit relatedness with other human beings. It is in intermediate areas that the infant selects and fills the transitional object, and importantly it is the use of transitional objects that marks the beginning of the capacity to symbolize. Jemstedt writes that Winnicott places illusion, the capacity to create, and the discovery of the object as surviving intact as fundamental aspects of being alive and necessary aspects of creative living.

Essays by Marco Armellini (Chapter 11) and Steven Groarke (Chapter 12) illuminate the last works produced by Winnicott before his death, Playing and Reality, Therapeutic Consultations in Child Psychiatry, and The Piggle; these were prepared by Winnicott and published after his death in 1971. Winnicott continually revised his work on “the emotional development of the individual human being,” but it remained unfinished until edited by Christopher Bollas, Madeleine Davis, and Ray Shepherd and was published posthumously, in 1988, as Human Nature. In “Expectation and Offer: The Challenge of Communication in Winnicott’s Therapeutic Consultations,” Armellini explores the intricacies of Winnicott’s thinking as exemplified in Therapeutic Consultations and The Piggle specifically. Armellini writes that these projects represent “a complex pattern of development and maturation,” and importantly these works are not “guides to the application of theory to different settings or as a demonstration of the clinical validity of theoretical concepts.” Winnicott was able to tolerate gaps and uncertainties in order to “preserve the full complexity of life.” While wanting to maintain openness and uncertainty, Winnicott was also able to recommend that a family needed a vacation and not analytic treatment. Frequently, Winnicott perceived that the patient needed contact and communication, not interpretation nor the omniscient knowledge of the analyst. Of vital importance is Winnicott’s stringent opinion that frequently symptoms are not signs of disease but rather are the communication of the patient’s developmental history and of suffering. Indeed, as Armellini writes,

we (that is, clinicians) “are implicitly asked not to explain”; moreover, Winnicott’s case studies illustrate “how tyrannical the intellect can be and how the mind can be a persecutory object.”

Steven Groarke’s essay “Winnicott and the Primacy of Life” explores the vitality of living, communicating, and making meaning. Volume 11 provides an account of Winnicott’s treatment of a young toddler—Gabrielle (“Piggle”)—who suffered from troubling fantasies. Winnicott describes his treatment of Gabrielle and enables readers to imagine and think through the treatment for themselves (thinking for oneself is a theme that is also taken up in Scarfone’s essay “Reading Winnicott Slowly”). Groarke pays close attention to Winnicott’s essay Human Nature. It is living, as Groarke writes, that is vital for Winnicott, who was resolved that it is living that gives life meaning. Groarke sums up the questions as follows: What did it mean for Winnicott to be on good terms with life? What kind of life did he assume a healthy person is able to live? And how might we live fuller, more meaningful lives? In short, it is reaching for, striving after, meaning that is to “reach for life.” This is not, though, about the avoidance of pain; indeed, for Winnicott suffering is a way of going-on-being, and the healthier the individual the greater the capacity for suffering. What we make of life is inextricably linked with what we make of the world we inhabit, and yet again Winnicott’s view is that the world has to be invented and perceived before it becomes habitable and thinkable. Of vital importance is what we make out of what we have.

These twelve essays explore Winnicott’s ideas, clinical innovations and intentions, his conceptualization of what it is to be human. The authors of these essays provide a rich elucidation of his capacity to communicate, to be an engaged and concerned bystander, to rethink psychoanalytic practice and theoretical dogma, and perhaps above all to be engaged in life. The last word belongs to Winnicott, who asserted that despite the pains and struggles of being a human being and the unspeakable difficulties, we are always “urged into life by living.”

{ Acknowledgments }

These essays were originally published as introductions to the eleven volumes of The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott. Lesley Caldwell and Helen Taylor Robinson are the General Editors of the Collected Works, and grateful thanks are due to them for their careful editorship and sustained stewardship of the Collected Works over a number of years. A large number of clinicians and academics initially reviewed the introductions, and the feedback provided was invaluable. Thanks are also due to Robert Adès, Emma Letley, Sarah Nettleton, and Clay Pearn for their work on the introductions to the Collected Works and for providing much-needed expertise.

I am grateful to Ann Horne and Angela Joyce for their help and support while I was editing these essays. Recognition is also due to members of the Winnicott Trust (past and present) for their unstinting enthusiasm for the publication of Winnicott’s work: Barbie Antonis, Lesley Caldwell, Steven Groarke, Ann Horne, Jennifer Johns, Angela Joyce, Ruth McCall, Marianne Parsons, Helen Taylor Robinson, Judith Trowell, and Elizabeth Wolf. Camilla Ferrier, Sarah Harrington, and Hayley Singer patiently answered my queries with humor and efficiency, and I owe them a debt of gratitude. Even though most of the work was undertaken during much-needed summer vacations, the contributors willingly answered any query with alacrity and good humor. Importantly, thanks are due to the authors of this collection of essays for their invaluable contributions to Winnicottian scholarship.

{ Contributors }

Marco Armellini

Marco Armellini has been a practicing child psychiatrist since 1985. He completed his training in Child and Adolescent Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy with Andreas Giannakoulas and Vincenzo Bonaminio in the 1990s. His clinical experience developed with the Italian public health sector, particularly in the area of infant mental health and autistic developmental disorders. He has published several contributions about the British Independent Tradition in psychoanalysis.

Vincenzo Bonaminio

Vincenzo Bonaminio, PhD, is training and supervising analyst of the Italian Psychoanalytic Society (SPI) and works in Rome in private practice with adults, adolescents, and children. He was Adjunct Professor at the Department of Child Psychiatry, La Sapienza, University of Rome, where he taught child psychotherapy, worked clinically with children, and coordinated a research group on brief psychoanalytic psychotherapy with latency children. For over 25 years he has been Director of the Istituto Winnicott, a training program for the psychoanalytic psychotherapy of children, adolescents, and parental couples, attached to the University. He is Director of the Winnicott Centre Italia in Rome. He has been Honorary Visiting Professor at University College London. He is co-editor of Richard e Piggle, the Italian Journal for the Psychoanalytic Study of the Child and the Adolescent, and co-editor of the series Psicoanalisi Contemporanea.

Lesley Caldwell

Lesley Caldwell, General Editor of the Collected Works, is a member of the British Psychoanalytic Association in private practice in London. She is a guest member of the British Psychoanalytical Society and a corresponding member of LAISPS—Los Angeles Institute and Society for Psychoanalytic Studies. She is an Honorary Professor in the Psychoanalysis Unit and Honorary Senior Research Associate in the Italian Department at University College London. As Chair of the Squiggle Foundation (2000–2003) and editor of the Winnicott Studies monograph series (2000–2008), she published four edited collections on D. W. Winnicott. She was an editor for the Winnicott Trust from 2002 to 2016 and the Chair of Trustees from 2008 to 2012. With Angela Joyce, she published Reading

Winnicott (2011). She has a continuing interest in psychoanalysis and the arts and has written on film and the city of Rome.

Paolo Fabozzi

Paolo Fabozzi, PhD, is training and supervising analyst of the Italian Psychoanalytic Society (SPI) and works in Rome in private practice with adults, adolescents, and children. He is an adjunct professor in the Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, “Sapienza,” University of Rome. He has published in international reviews and edited Al di là della metapsicologia (1996), Il sé tra clinica e teoria (2000), and Forme dell’interpretare (2003).

Anna Ferruta

Anna Ferruta is Psychologist, Full Member and Training Analyst of the Italian Psychoanalytic Society and of the International Psychoanalytical Association. She is a member of the Monitoring and Advisory Board of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis and past Director of Training at the Italian Psychoanalytic Society. She works as a psychoanalyst in Milan, Italy, specializing in the treatment of severe psychic pathologies and the psychodynamics of institutional working groups. She is a founding member of Mito & Realtà: Association for Therapeutic Communities. Other appointments have included Vice-Director of Psiche, Lecturer in Psychiatry at the University of Pavia, and consultant at the Neurological Institute C. Besta in Milan. She is the author of several Italian and international publications, including books (Pensare per Immagini, Borla, 2005; Le Comunità Terapeutiche, Cortina, 2012; La cura psicoanalitica contemporanea. Estensioni della pratica clinica, Fioriti, 2018), articles (“Continuity or discontinuity between healthy and pathological narcissism,” Italian Psychoanalytic Annual, 2012; “Setting analitico e spazio per l’altro,” Rivista di Psicoanalisi, 2013), and chapters (“Themes and developments of psychoanalytic thought in Italy,” in F. Borgogno, A. Luchetti, & L. Marino Coe [Eds.], Reading Italian psychoanalysis. London/New York: Routledge, 2016).

Steven Groarke

Steven Groarke is Professor of Social Thought at Roehampton University, an analyst of the British Psychoanalytical Society, and a member of the International Psychoanalytical Association. He teaches at the Institute of Psychoanalysis in London and is an Honorary Senior Research Associate at University College London and a training analyst of the Association of Child Psychotherapists. He is a member of the Editorial Board and Reviewing Panel, respectively, of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis and the British Journal of Psychotherapy. He currently works as a psychoanalyst in private practice in London.

Ann Horne

Ann Horne is a Fellow of the British Psychotherapy Foundation and an Honorary Member of the Czech Society for Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy. A former Head of the Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Training at the British Association

of Psychotherapists (now IPCAPA at the BPF), she was co-editor of the Journal of Child Psychotherapy and The Handbook of Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy (1999; 2nd ed. 2009) and of four books in her Routledge series on Independent Psychoanalytic Approaches with Children and Adolescents. Her selected papers—On Children Who Privilege the Body: Reflections of an Independent Psychotherapist will be published by Routledge in September 2018. Retired from clinical practice, most recently at the Portman Clinic, London, she teaches and lectures in the United Kingdom and abroad.

Arne Jemstedt

Arne Jemstedt, MD, is a psychoanalyst with a private practice in Stockholm. He is a member and training analyst of the Swedish Psychanalytical Association. He was President of the former Swedish Psychoanalytical Association from 1997 to 2003 and the first President of the new Swedish Psychoanalytical Association (formed through the fusion of the Swedish Society and the Swedish Association) from 2010 to 2012. He is the editor of Swedish translations of several of Winnicott’s books and has published articles and chapters on Winnicott’s work in Swedish and international psychoanalytic journals and books. He is European Co-Chair of the project IPA Encyclopaedic Dictionary.

Jennifer Johns

Jennifer Johns is a Fellow of the Institute of Psychoanalysis in London. She came to psychoanalysis from general medical practice and was supervised during her training by Donald Winnicott. She has worked in psychotherapy departments at University College Hospital in London and at the West Middlesex Hospital. She has an interest in psychosomatic disorders. An editor and member of the Winnicott Trust for many years, she chaired the Trust from 1997 to 2008 and has taught Winnicott’s work widely.

Marcus Johns

Marcus Johns is a Fellow of the Institute of Psychoanalysis in London. He studied medicine at Charing Cross Hospital and psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital. He trained in child and family psychiatry at the Tavistock Clinic and was Director of the Child Guidance Training Centre, where he was Consultant-in-Charge of the Day Unit for disturbed children. During this time, he trained as a psychoanalyst and became Acting Director of the London Clinic of Psychoanalysis. He was an editor of the Bulletin of the British Psychoanalytical Society. He is past Chair of the Trustees for the International Pre-Autistic Network (IPAN).

Angela Joyce

Angela Joyce is a training and supervising psychoanalyst with the British Psychoanalytical Society and a child psychoanalyst trained at the Anna Freud Centre in London, where she has been a member of the pioneering Parent Infant Project for many years; there she jointly led the resurgence of child psychotherapy. She works in private practice in London and is an Honorary

Senior Lecturer at University College London. She is a trustee of the Squiggle Foundation and Chair of the Winnicott Trust. She has written papers and contributed to books on early development and parent–infant psychotherapy. With Lesley Caldwell she edited Reading Winnicott, published as part of the New Library of Psychoanalysis Teaching Series in 2011, and she edited Donald Winnicott and the History of the Present, published by Karnac in 2017.

Amal Treacher Kabesh

Amal Treacher Kabesh was the Managing Editor of The Collected Works of D. W. Winnicott. She has a longstanding interest in bringing together psychoanalytic and cultural theory in order to understand identity (especially gender and ethnicity) and she has published extensively on these topics. She is an Associate Professor in the School of Sociology and Social Policy at the University of Nottingham. Her two recently published books are Postcolonial Masculinities: Emotions, Histories, and Ethics (Ashgate, 2013) and Egyptian Revolutions: Conflict, Repetition and Identification (Rowman and Littlefield, 2017).

Christopher Reeves

Christopher Reeves (1939–2012) was a child psychotherapist who trained at the Tavistock Clinic in London and had some personal experience of Winnicott, having attended seminars at his house during the last two years of Winnicott’s life. His papers on the theoretical and clinical aspects of Winnicott’s work have been published in the United Kingdom and America. He edited a collection of essays, Broken Bounds: Contemporary Reflections on the Anti-Social Tendency (2012), and was a contributing editor to Judith Issroff’s Donald Winnicott and John Bowlby: Personal and Professional Reflections, both published by Karnac Books. He was Director of the Squiggle Foundation from 2008 to 2011.

Ken Robinson

Ken Robinson is a psychoanalyst in private practice in Newcastle upon Tyne. He is a member of the British Psychoanalytical Society and was formerly its Honorary Archivist. He is a training analyst for child and adolescent and adult psychotherapy in the North of England and Scotland and lectures, teaches, and supervises in the United Kingdom and Europe. Before training as a psychotherapist and psychoanalyst, he taught English Literature and the History of Ideas in the university and maintains an interest in the overlap between psychoanalysis and the arts and humanities. His essay “Creativity in Everyday Life (or Living in the World Creatively)” appeared recently in Donald Winnicott and the History of the Present edited by Angela Joyce (Karnac, 2017). He is especially interested in the nature of therapeutic action and the history of psychoanalysis and is currently completing a book on the use in the consulting room now of basic clinical concepts rooted in the theory and practice of Freud, Ferenczi, Balint, and Winnicott.

Dominique Scarfone

Dominique Scarfone, MD, was full professor and is now honorary professor at the Department of Psychology of the Université de Montréal and trainingsupervising analyst at the Institut psychanalytique de Montréal (French section of the Canadian Psychoanalytic Institute). A former associate editor of the International Journal of Psychoanalysis, he has published five books: Jean Laplanche (1997; translated into Hebrew, Italian, and English), Oublier Freud? Mémoire pour la psychanalyse (1999), Les Pulsions (2004; translated into Spanish and Portuguese), Quartiers aux rues sans nom (2012), and The Unpast: The Actual Unconscious (2015). He is the author of several book chapters and numerous articles published in international journals. He is invited regularly to give seminars and conferences in various countries and was author of one of two key papers discussed in the 2014 International Congress of French-Speaking Analysts in Montreal. He will be one of the keynote speakers at the 2019 Congress of the International Psychoanalytic Association in London.

Helen Taylor Robinson

Helen Taylor Robinson, General Editor of the Collected Works, is Fellow of the Institute of Psychoanalysis, British Psychoanalytical Society, London, and was a clinical psychoanalyst with adults and children until her retirement. She was an Editor and Trustee of the Winnicott Trust for seventeen years and co-edited Thinking About Children with Jennifer Johns and Ray Shepherd. Her special interest is in the relationship of psychoanalysis to the arts, literature, and cinema. She has been Honorary Senior Lecturer at the Psychoanalysis Unit of University College London. She has contributed to books and journals in the field of psychoanalysis and to the European Psychoanalysis and Film Festival.

The Enduring Significance of Donald W. Winnicott

General Introduction to the Collected Works

Lesley Caldwell and Helen Taylor Robinson

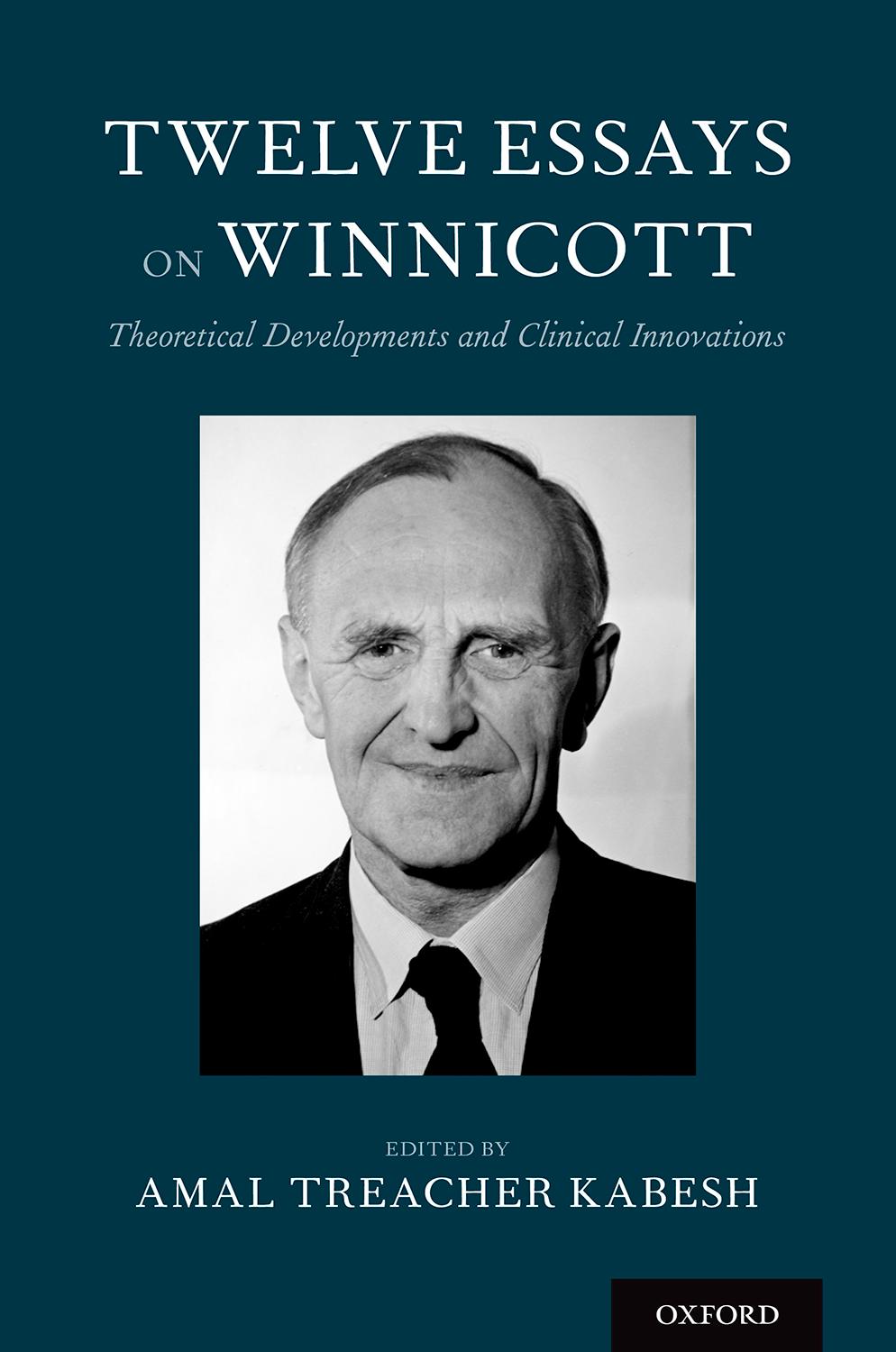

Donald Woods Winnicott is a major figure in the world of psychoanalysis. His books have been translated into many languages, his are the most frequently accessed psychoanalytic writings online, and his innovative ideas have provided a continuing focus in the training of psychoanalysts and in debate at national and international congresses. Not only was Winnicott, according to André Green, the most important psychoanalytic thinker after Freud, he was committed to making a psychoanalytically informed approach available to a wider public. No psychoanalyst before or since has been so intent or so successful in bringing psychoanalysis into public institutional and cultural life. His openness and the facility for communicating that he displayed in very different contexts extended to a willingness to debate with fellow practitioners of different orientations and approaches, professionals from related fields, and a vast general audience. In his capacity to convey highly specialized thought effectively, he made use of technical language and that of paradox and metaphor. His interest in understanding the interaction between inner and outer reality within the growing individual was sustained with increasing complexity throughout his life.

After Freud, Sandor Ferenczi, and Karl Abraham, Winnicott, with Melanie Klein and Anna Freud, is a major figure of the second generation of psychoanalysts. His writing, teaching, and broadcasting helped to take psychoanalysis forward by making it a continuingly relevant and dynamic discipline. His work in pediatrics and child psychiatry, education, child health, and development remains influential, and, more recently, associated disciplines in the humanities and social sciences have begun to use his work.

Brief Biography

Winnicott (1896–1971)1 grew up in the prosperous business class in Devon, England, where he enjoyed a cared-for, somewhat religious upbringing, with two older loved sisters and many cousins living nearby. His father was twice mayor of Plymouth and knighted for his contribution to local politics, but it appears to have been his mother, sisters, cousins, and the family servants who constituted Winnicott’s main early environment. He was sent to The Leys School in Cambridge at the age of thirteen and then began to study biology at Cambridge with a view to training in medicine. In his adolescent years, he appeared to be as good at sports, singing, and playing as at academic work. He read and admired Darwin and was already manifesting a concern for the less fortunate in the local Cambridge community. He had a short period as a volunteer medical officer on board a navy destroyer during World War I, which brought him up against death and loss at an early age.

On beginning his medical training at Bart’s Hospital, London, in the autumn of 1917, Winnicott, troubled by his dreams, came across Freud and felt he had discovered something significant. In 1923, he sought analysis with James Strachey for his “inhibitions” (and his short height, he joked later). After medical qualification in 1920, he worked as a House Physician in several hospitals specializing in children’s medicine before being appointed, in 1923, to Queen’s Hospital, Bethnal Green, and Paddington Green Children’s Hospital. He had a private practice in child medicine near Harley Street, and, at the age of twenty-seven, he married Alice Taylor. By 1934, Winnicott had qualified as an analyst. He kept medical posts in public health until his retirement in 1961, but he was particularly committed to the psychological aspects of his work, especially with mothers and children. He completed the child analytic training in 1935, and, in 1936, he began a second analysis with Joan Riviere. He offered intensive analytic work and shorter psychotherapeutic interventions to children and adults. In 1939, he began writing radio broadcasts for mothers.

While valuing much of what he had learned, Winnicott began to break with some of his psychoanalytic mentors on the basis of what he observed daily in his clinical work. He became confident that the infant’s actual dependence on the maternal/familial environment made the interactions of mother and child from birth crucial for psychic development. Despite the emphasis on the internal world of fantasy, he became more and more committed to what real babies need to develop a healthy self as the basis for a creative life.

During the period of the British Society’s Controversial Discussions (see later in the chapter) and a certain polarization of ideas around the developmental model

1 For extensive bibliographies of Winnicott’s life see Adam Phillips (1988), Brett Kahr (1996), Robert Rodman (2003), and Jennifer Johns (2006).

of Anna Freud and Klein’s model of the internal world’s unconscious fantasy structure, Winnicott was able to maintain his own often uncompromising stance.

After his father’s death in 1948 (his mother had died in 1925), he divorced Alice and married Clare Britton, who became the focus of his personal world and a professional collaborator for the rest of his life. He had worked with Clare, a gifted psychiatric social worker (and subsequently a psychoanalyst), in the Oxfordshire Evacuation Scheme, which led to their contributing to the postwar government planning of children’s services. In 1948, Winnicott had his first heart attack, the condition that would lead to his death in 1971.

Winnicott was Chair of the International Psychoanalytical Association’s 1953 committee of investigation of Jacques Lacan, served as President of the British Psychoanalytical Society from 1956 to 1959 and again from 1965 to 1968, and managed the Child and Adolescent Department of the London Clinic of Psychoanalysis. He was also instrumental in the establishment of the Finnish Psychoanalytic Society. He was President of the Paediatric Section of the Royal Society of Medicine (1952) and of the Association for Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Chairman of the Medical Section of the British Psychological Society (1948). He won the James Spence Gold Medal for Paediatrics in 1968.

He published his first collected papers in 1958. As an internationally known clinician, he gave well-received lectures in America in 1962 and 1963, but, on a visit to New York at the end of 1968, his ill health caught up with him. In the last two years of his life, Winnicott prepared and planned books and, when he could, took on speaking engagements. He died in January 1971.

Psychoanalytic Writing: DWW and the Tradition

While all conscious communications are inflected with unconscious meaning for psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic writing itself is subject to this dimension. Winnicott’s writing style, commented on both critically and favorably by so many of his readers, makes his works distinctive. From the very early letter about psychoanalysis to his older sister Violet [CW 1:1:11] to his late piece on “The Unconscious” [CW 7:3:29], he shows great skill in conducting a conversation between aspects of familiar and less familiar ways of engaging with an idea and an emotional experience.

The American analyst Thomas Ogden (2005, p. 109) discusses psychoanalytic writing as a literary genre that attempts to replicate “something like the analytic experience” through a continuing conversation that draws on conscious and unconscious experience. Through his or her writing, the analyst is engaged in a creative act in which “the reader in the experience of reading has a sense not only of the critical elements of an analytic experience that the writer has had with the patient, but also ‘the music of what happen(ed)’ ” (Heaney, 1979, p. 173). For him, the best psychoanalytic writing is the expression of this “conversation” between