1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in India by Oxford University Press 2/11 Ground Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002, India

© Oxford University Press 2019

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

First Edition published in 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

ISBN-13 (print edition): 978-0-19-948940-4

ISBN-10 (print edition): 0-19-948940-8

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-0-19-909458-5

ISBN-10 (eBook): 0-19-909458-6

Typeset in Minion Pro 10.5/13 by Tranistics Data Technologies, Kolkata 700091

Printed in India by Rakmo Press, New Delhi 110 020

PREFACE

As Biswamoy Pati’s Tribals and Dalits in Orissa goes posthumously into print, I write this Preface for a volume that he will never get to see. His sudden and untimely demise in June 2017, following a minor surgical procedure, has thus robbed him of what he would have jestingly termed the ‘fruits of his labour’. This study therefore marks the end of a lifetime of a prodigious publishing output which totalled more than twenty volumes, consisting of monographs and edited collections of essays—the latter epitomizing his gift of ‘inclusiveness,’ his ability to bring together contributors from across the country and the world.

Working on this last MS of his has been my sole mission over the last several months. It has been an emotional journey. While preparing this book for publication, I recalled how, as young people starting out our life together some three decades ago, we had both enthusiastically copy-edited his first book Resisting Domination: Tribals, Peasants and the National Movement in Orissa, 1920–1950 (1993), based on his PhD thesis. That pioneering work which marked a milestone in Orissa’s historiography brought into focus the forgotten ‘Others’, namely the tribals, outcastes, and peasants who had been invisibilized by history.

Underlying this research actually lay deeply held, passionate, political convictions and an identification with those who had been dispossessed and disenfranchised by history. I remember how in the context of the early 1980s, when railway networks, and even roads,

barely existed in parts of the western interiors of Orissa, Biswamoy carried out arduous fieldwork, interviewing tribal communities in the remotest areas of Koraput, Jeypore, and the Bonda hills, regions possibly not visited by any historian before.

Over the years his research on the marginal sections went on to encompass an extensive range of themes—most notable was his pathbreaking work on the social history of health and medicine; indigenous and tribal medicine; leprosy, small pox, and the treatment of insanity in colonial institutions such as the Cuttack lunatic asylum. Some of the other key issues he wrote on included the neglected region of western Orissa with its princely states, the process of Hinduization among tribals in colonial Orissa; the forgotten role of advasis and tribals in the Rebellion of 1857, as well as their role in the Indian National Movement. This last monograph of his brings together many of these broad strains.

Biswamoy’s serious commitment to research was inspirational for me as well, his friend and partner. His enthusiasm underlay every book of mine, even though my own area was so different, centring on the white woman in colonial India. And as far as young research scholars were concerned, he was always sympathetic and encouraging, ever-ready to discuss their projects, chapters, and proposals. He often included their work in his collections of essays and helped them in getting their first book published. He has thus left behind a legacy of fine young scholars.

This particular volume could never have been finalized without the help of our dear young friend Saurabh Mishra. Despite his own hectic schedule at the University of Sheffield, and innumerable other commitments and responsibilities, Saurabh took it upon himself to perform the Herculean task of helping out with ‘Sir’s’ MS in the initial phase. It was like a mission for him. He took it up at a time when I was not in a position to be able to concentrate immediately after Biswamoy’s sudden demise. My immense gratitude to Saurabh cannot be put in words.

Finally, I cannot forget the generosity of Dr Cornelia Mallebrein who responded immediately to my emailed request, with images collected by her from the western interiors of Orissa, to be used on the cover. I cannot thank her enough for facilitating this in his last book.

Indrani Sen New Delhi, 2018

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The social history of the marginal people of Orissa has been the focus of my research for the last four decades or so. Some of the issues that I deal with in this monograph are also the ones that have occupied me from my earliest works. In the course of this long journey which began with my doctoral work in the 1980s, I have incurred numerous debts both personal and institutional.

I must first thank the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi for awarding me a Senior Fellowship which enabled me to work on this book in an uninterrupted fashion. My sincere thanks to the helpful staff of various archives and repositories which I have used over the years; in particular, the Orissa State Archives (Bhubaneshwar); the West Bengal State Archives and the National Library (both in Calcutta); the National Archives of India and the Nehru Memorial Museum Library (both in New Delhi); the Oriental and India Office Records at the British Library and Wellcome Library (both at London); and the South Asia Institute Library (Heidelberg).

Fellowships and grants by funding bodies and institutions have supported parts of my research over these years, including a British Academy ‘Visiting Fellowship’ at Sheffield Hallam University; a ‘Ratan Tata Fellowship’ at the London School of Economics; a ‘BadenWuerttemberg Fellowship’ at Heidelberg University; a ‘Career Award’ Fellowship and a ‘Research Award’ Fellowship awarded by the

University Grants Commission, New Delhi; an ‘International Visiting Fellowship’ at Oxford Brookes University; and a ‘Visiting Fellowship’ at the Department of History, Aarhus University, Denmark. Grants from the Indian Council for Historical Research, Wellcome Trust, and the Charles Wallace India Trust also helped me to do research work at London.

Several of the ideas contained in the book have been presented at seminars/conferences and lectures; conferences of the Society for the Social History of Medicine at Queen’s College, Oxford; the American Association for the History of Medicine at Johns Hopkins University, Bethesda; the European Science Foundation at Wolfson College, Cambridge; the South Asian Studies Institute, University of Heidelberg; the International Institute of Asian Studies, Leiden; the International Convention of Asian Scholars at Singapore; the two conferences of the Orissa Research Programme at Salzau, Germany; the two conferences on the Princely States and India’s Independence at the University of Southampton; the conference organized by Goldsmiths College and Edinburgh University at London; the European Conference on South Asian Studies, University of Zurich; the International Conference on Asian medicine, Changwon, South Korea; the South Pacific Workshop, at the University of Canterbury, New Zealand and the International Leprosy History Symposium at the Sasakawa Memorial Health Foundation, Tokyo. In India, recent lectures and conference presentations at Utkal University, Berhampur University, Adaspur College (all in Orissa); Jadavpur University, Ramsaday College, IDSK, Calcutta University (all in Kolkata); the Centre for Contemporary Studies (Nehru Memorial Museum and Library), Jamia Millia Islamia and the National Archives (all at New Delhi). Most recently, the National Conference on ‘Anthropological Histories and Tribal Worlds in India’, at the Indian Institute of Advanced Study, Shimla; the Conference on ‘The Caste Question and the Historian’s Craft’ at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, New Delhi. I wish to thank all those who interacted with me at these forums, with their questions, suggestions and comments: these have helped me to sharpen my focus and my arguments.

I am grateful to all those whom I have interviewed in the course of my research. I cannot forget the ‘unknown’ tribal folk of Koraput, Kalahandi, and the Bonda hills around whom my life’s work has

revolved all these years, and from I have learnt so much about the meanings of social exclusion.

I also acknowledge the encouragement I received at various stages from Professors Amiya Bagchi, Amit K. Gupta, Hermann Kulke, K.N. Panikkar, and Sumit Sarkar. The friendship of Amar, Amit, Arun, Bahuguna, Bhairabi, Gopi, Lata, Madhurima, Mark, Mayank, Mridula Ramanna, Pralay, Prasun, Rajesh, Raj Kumar, Rajsekhar, Ramakrishna da, Sanjukta, Sarmistha, Sekhar, Shashank, and Waltraud has sustained me in various ways. During research visits to England, there was always Manu, Menka, Samiksha, and Saurabh to provide laptops and blankets and add cheer to our stay. Special thanks to Manmohan for his help at all times, and also to Ranjana, Saurav, and Shilpi.

I appreciate the keen interest taken by Oxford University Press, New Delhi, in this monograph. I also wish to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

My parents who always encouraged my research are not here to see this book; Alekha Bhai, Bhauja, Bindu, Jiban, Sukanta, Tina, and my nephew Sobhan have always been supportive. My final thanks goes to Indrani, my friend and companion throughout this long journey; she has not only been actively involved with this work, but with everything else that I have written in the past.

Earlier versions of some the chapters have appeared as follows: Chapter 2 (as ‘Rhythms of Change and Devastation: Colonial Capitalism and the World of the Socially Excluded in Orissa’) in Social Scientist (Vol 44, No. 7–8, July–August, 2016, pp. 27–51); Chapter 3 (as ‘Survival, Interrogation, and Contests: Tribal Resistance in Nineteenth Century Odisha’) in Uwe Skoda and Biswamoy Pati (eds)., Highland Odisha: Life and Society (New Delhi: Primus, 2017, pp. 23–48); and Chapter 6 (‘Alternative Visions: The Communists and the State People’s Movement, Nilgiri 1937–1948’) in Arun Bandhopadhyay and Sanjukta Das Gupta (eds), In Search of the Historian’s Craft (New Delhi: Manohar, 2018, pp. 435–62). I thank the publishers for their permission to use them here.

Biswamoy Pati New Delhi, 2017

ABBREVIATIONS

AICC All India Congress Committee

AISPC All India State People’s Conference

BL British Library, London

CDM Civil Disobedience Movement

CFLN Confidential File on Laxman Naiko at the Mathili Police Station

CPI Communist Party of India

EIC English East India Company

FIR First Information Report

HPFR Home Political Fortnightly Reports

IOR India Office Records, British Library, London

NAI National Archives of India, New Delhi

NGO Non-governmental Organization

NLS National Library of Scotland

NMML Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi

NPARI Nilgiri Praja Andolanara Itihasa (The History of the Nilgiri Prajamandal)

OLAP Orissa Legislative Assembly Proceedings

ORP Orissa Research Project

OSA Orissa State Archives

PCC Provincial Congress Committee

PW Prosecution Witness

RPEAEC Report of the Partially Excluded Areas Enquiry

Committee Orissa 1940

SC Sessions Court

SCP Sessions Court Proceedings

SF Subject File

WBSA West Bengal State Archives

WWCC Who’s Who Compilation

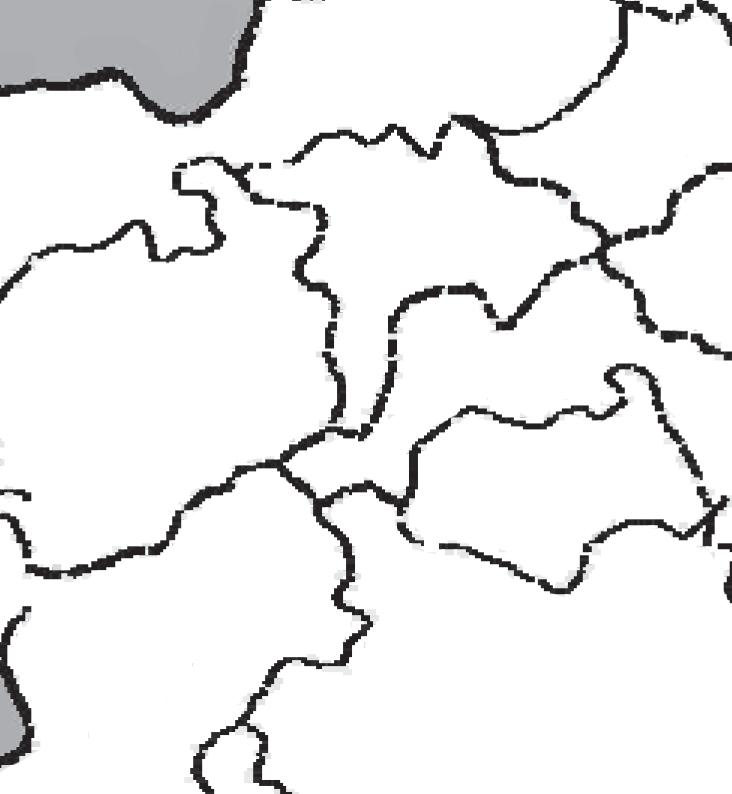

MADHYA PRADESH

Bolangir

Mayurbhanj Sundargarh

Sambalpur

Keonjhar

WEST BENGAL

Dhenkanal

O R I S S A

Kalahandi Baudh Khandmals

Puri

Balasore

Cuttack

Koraput ANDHRA PRADESH

Ganjam

Map 1 Orissa: Provinces

Source: Author.

B a y o f

B e n g a l

Note: This map does not represent the authentic national and international boundaries of India. This map is not to scale and is provided for illustrative purpose only.

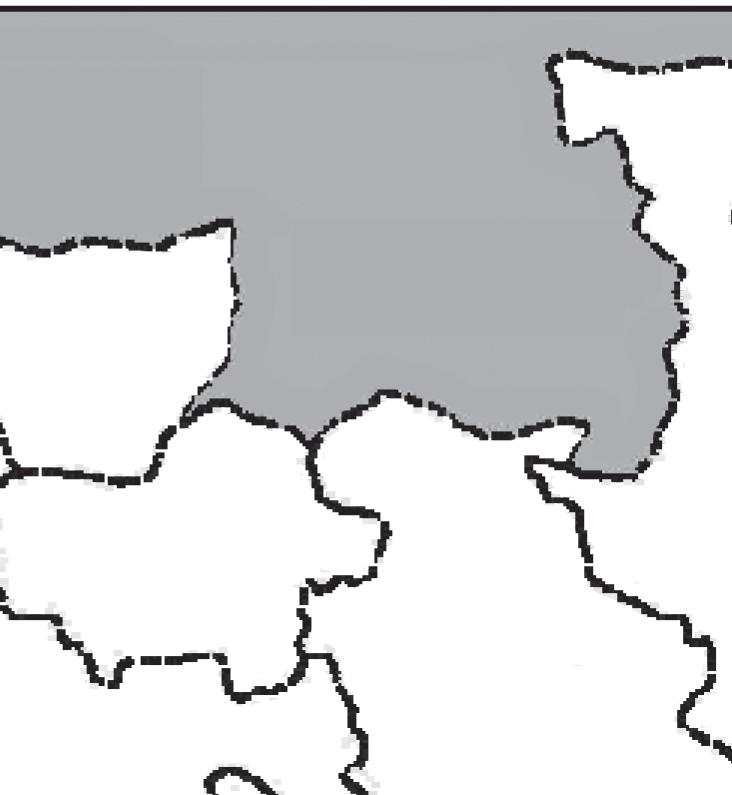

BIHAR

Rajpur

Bastar

Ranchi

Gangpur

Sambalpur

Patna

Singhbhum

Bonai

Bamra

Koraput

Madras Kalahandi

Rairakhol

Sonepur

Baud

Singhbhum

Mayurbhanj

Midnapur

Pallahar

Talcher

Athmallik

Narsingpur Angul

Keonjhar NBalasore ilgiri

Dhenkanal

Hindol

Baramba

Khandapara

Nayagarh

Ranpur

Puri

Cuttack

Ganjam

Map 2 Princely States of

Orissa

B a y o f

B e n g a l

Province boundary

Princely State boundary

District boundary

Source: Author.

Note: This map does not represent the authentic national and international boundaries of India. This map is not to scale and is provided for illustrative purpose only.

CHAPTER ONE

Invisibility, Social Exclusion, Survival

Tribals and the Untouchables/Dalits in Orissa

This book aims to trace the history of the excluded people of Orissa over a time frame that takes into account the colonial and the postcolonial. The narrative begins in colonial times, when many longterm developments in the tribal context were first set into motion. Social historians speak of the ‘long term’, the ‘day to day’ and the explosive/extraordinary forms of protest while referring to the lives of oppressed social groups. However, one wonders if features such as basic survival strategies are taken into account when talking of the socially excluded. Besides the fact that protests in some form or the other made the tribals and outcastes/dalits enter the official files and the colonial archive, this study also takes into account strategies for survival when examining their lives. After all, the basic act of simply surviving not only demonstrates resistance but is something that

Tribals and Dalits in Orissa Biswamoy Pati, Oxford University Press (2019). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780199489404.003.0001.

simultaneously expresses a whole range of possibilities related to existence.

The fact that they somehow managed to survive has, hidden right beneath the surface, a whole range of complexities while also demonstrating the ability to resist or push back against dominant social orders. In terms of method, this implies unveiling the lives and times of people that have been hidden and invisibilized. The task of the historian is to recover these lives and to dig into the layers that lie submerged beneath the humdrum realities of existence. These are some of the complexities that I seek to explore in this book. Apart from looking at the connections between the historical past, and controversies that rage on in the present day, one of the other aims of the book is to analyse some powerful colonial discourses regarding tribes.

SITUATING ORISSA

Orissa is often perceived as consisting of two parts: the fertile coastal strip towards the east, and the relatively more remote forested and mountainous region in the west. While about half of Orissa’s inhabitants live in the coastal tract, the remainder of the population composed largely of poor adivasis (tribals) and outcastes inhabit the mountainous regions. The Kandhas, Santhals, Mundas, Gadbas, Hos, Bhuyans, Koyas, Juangas, Parajas, Sauras, Kols, Bhumijs, and Bondas are among the prominent tribal communities, but the ranks of ‘marginal people’ are also swelled by non-tribal low castes/outcastes. Prominent among the non-tribal low castes/outcastes were the Panas, Bauris, Hadis, and Kandaras. Most of them worked as agricultural labourers (some of whom were bonded, or forced labourers), and some marginal peasants faced dispossession and loss of ‘customary’ rights over natural resources, like forests.

Post-colonial Orissa presents a classic case of the contradictions of underdevelopment. It is a storehouse of natural resources, ranging from bauxite, iron ore, and coal to forest resources—especially in the western hilly regions—and has naturally attracted huge investments related to major multinational-backed projects, very often without proper assessment of how these would impact the people

or the region.1 This is in sharp contrast to the life of the majority of the population—the marginal adivasis, low castes (which include the Sudras, some of whom were/are defined as ‘untouchables’ due to the ambiguous and oppressive realities of the caste system) and outcastes.

Historically, Orissa has been marked by economic, social, and cultural variations. During Mughal rule (1578–1751), it was split into two parts based on geographical, ecological, and economic divisions: the fertile coastal plain (the moghulbandi area) held directly by the Mughals, and the hilly, heavily forested hinterland (garhjat states). In 1751 Orissa was taken over by the Marathas, and in 1803–4 it was taken over by the English East India Company (which occupied the coastal belt and incorporated it into the Bengal Presidency). During colonial rule Orissa was divided into British India, consisting of the directly controlled coastal districts of Puri, Cuttack, and Balasore in the east and the princely states (also variously termed by the British as the ‘tributary states’ or ‘feudatory states’), mostly located in western Orissa, which were under indirect British rule. Besides, there were a number of zamindaris along the coastal tract of Balasore, Cuttack, Puri, and Ganjam, which were all under direct colonial administration. Right up to the country’s independence, Orissa comprised twenty-six princely states, some of which had zamindaris under them. Geographically located in what was identified as the non-coastal, western interior, they were also referred to as garhjats (garh=fort).2

COLONIAL INTERVENTIONS , TRIBALS , AND UNTOUCHABLES : LAND SETTLEMENTS AND THE EXPANSION OF CULTIVATION

The British colonization of Orissa saw major agrarian interventions over the nineteenth century. These were primarily in the form of land

1 Very few studies exist on this subject; to get an idea on this aspect see, for instance, Felix Padel and Samarendra Das, Out of this Earth: East India Adivasis and the Aluminium Cartel (New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan, 2010).

2 In course of the chapters in this book we specifically touch upon the princely states of Kalahandi, Mayurbhanj, Nilgiri, Gangpur, Keonjhar, and the erstwhile Jeypore zamindari.

revenue settlements that were aimed at tapping agrarian resources. Whereas land settlements with the princely states and zamindars (landlords) were made on a long-term, permanent basis, parts of the coastal tract which were directly under the British only experienced temporary settlements. The colonial agrarian interventions saw the emergence of private property, land rights, commercialization of agriculture, and an increasing degree of monetization. Although marked by diversities, the impact generated by colonialism on the world of the tribals was increasingly felt in a significant manner after the formal takeover of Orissa by the English East India Company (1803–4). British policy was aimed at expanding plough cultivation in areas where shifting cultivation was practised, but the promotion of the plough was not very successful as it did not suit the environment where it was being introduced. This, again, led to the impoverishment of the ordinary jhum/podu cultivator as they could not successfully take up the plough.

As for the untouchable castes, a dominant section was associated with various activities ranging from the traditional industries (like cotton and salt-manufacturing—for example, Malangis, who practised the latter as their caste profession) and agriculture. The shifts and changes over the nineteenth century posed major challenges that unsettled them by dispossessing them. What one witnesses, as a result, is the development of a surplus labour force, new systems of bonded labour, and a new pattern of migration.

Simultaneously, one needs to grapple with the way the sahukar–zamindar–sarkar (money-lender–landlord–government) nexus impacted the tribals, untouchables, and dalits, the question of dispossession/ migration, and the process of politicization and resistance. Alongside that, one has to factor in crucial issues faced by households of the socially excluded. These ranged from the imposition of restrictions through forest laws (which produced very serious problems like the undermining of the traditional medicinal system) and the manufacture of liquor, to the resistance to women obtaining land rights. The last of these, in turn, saw patriarchal forces attempting to reassert themselves through practices like witch-hunting. Consequently, one has to go way beyond the colonial/anti-colonial paradigm to explore areas of social history in order to grapple with the issue of social exclusion. This would not only enable us to see a holistic picture without

romanticizing anything, but also direct scholarly attention towards effective analyses of the scope and basis of their apparent anti-colonial ‘outbursts’.

One of the serious changes that occurred during the colonial period was the entrenchment of the British administrative system, which resulted in large-scale interference with the existing way of life. Colonialism’s power extended into the forests in a significant manner, regulating, controlling, and tapping their resources. This undermined the administrative and economic position of tribal chiefs in their own territories, with village-level institutions losing their powers when it came to controlling land and forests. In parts of the Bengal Presidency such as Orissa, some of the relatively privileged tribal chiefs were incorporated through the land settlements and Brahminical Hinduism’s caste system as ‘tributary chiefs’ (princes) and zamindars, along with sections that were ‘outsiders’ and those who were settled as zamindars. These princes and zamindars emerged as the support base of British colonialism. They were required to pay a tribute (peshkush) to the colonial government out of the rents extracted from the tribals and the settled agriculturalists. Besides ensuring a steady inflow of resources for the colonial administration in the form of the tribute that these princes paid, this also served to tap the resources and administer the inaccessible forest tracts. The introduction of this new system of administration considerably lessened the power of village-level institutions.

The princely states were largely despotic and labels such as the andharua mulaks (the ‘dark zones’) were popularly bestowed on them. In fact, popular memory remembers the people of the twenty-six princely states as garhjatias (residents of the garhjats) who accepted and tolerated their despotic chiefs along with the terror that was unleashed by these despots. Most of the princely rulers went to great lengths to prove their antiquity and invented their ancient past through rajabansabalis (chronicles of their ancestral genealogies), which set off a virtual competition among them to validate their claims and, in many cases, to establish imagined links with the martial ‘Rajput’ traditions of north India.

The summary settlements in the princely states significantly reinforced a process of social stratification that had pre-colonial origins. While the states paid a paltry, fixed amount (peshkush) to the British,

they collected large amounts of revenue from the people through taxes, which were arbitrarily and exponentially increased every year. Thus, throughout the nineteenth century, the system in the princely states was designed, preserved, and reinforced by colonialism, with the active collaboration of the feudal chiefs as its junior partners. In some instances, some of the princely darbars (princely courts) also flirted with the idea of ‘modernity’. This had a direct bearing on their mode of functioning. While essentially conservative in their existence, these princes joined the bandwagon of ‘modernity’ to legitimize their position in the eyes of both the British as well as the emerging Indian middle class. Consequently, what needs to be stressed is that, through the incorporation of the project of ‘modernity’, the darbars legitimized their existence as much as they legitimized colonialism. This meant that the peasants and tribals in the princely states lost out in two ways: they had no rights over lands (in fact even customary rights over forest, pastures, and rivers were progressively undermined over the nineteenth century itself), and they were left mercilessly to the whims of the darbars when it came to taxation demands, which increased steadily from the 1860s to the 1940s. All of these are issues that we shall examine in greater detail in Chapter 2.3

DEFINING ‘ TRIBAL ’ IDENTITY IN COLONIAL ORISSA

The initial years of colonial presence were restricted to the coastal tract, and both Puri and Jagannatha emerged as key components of the drive for legitimacy, so that the state did everything possible to get ‘Jagannatha’ to sanction its authority.4 While striking terror on the hills and crushing the Rendo Majhis, the Chakra Bisois and,

3 For details see Waltraud Ernst, Biswamoy Pati, and T.V. Sekhar, Health and Medicine in the India Princely States, 1850–1950 (London: Routledge, 2018). See also Biswamoy Pati, ‘The Order of Legitimacy: Princely Orissa, 1850–1947’, in Waltraud Ernst and Biswamoy Pati (eds), India’s Princely States: People, Princes and Colonialism (London: Routledge, 2007), 85–98.

4 For details, see Hermann Kulke, ‘ “Juggernaut” under British Supremacy and the Resurgence of the Khurda Rajas as the “Rajas of Puri” ’, in A. Eschmann, H. Kulke and G.C. Tripathy (eds), The Cult of Jagannatha and the Regional Tradition of Orissa (New Delhi: Manohar, 1978), 346.

later, the Dharani Bhuyans, the enterprise of acquiring knowledge to effectively control the region formed a central part of colonial policy.5 This implied intellectual productions associated with classifying strategies that saw the active support of some upper caste collaborators. Reinforcing this phenomenon were major contributions made by colonial officialdom, the upper castes, and propertied sections such as the princes and the zamindars.

Another part of this enterprise meant that everything had to be given a form and position and incorporated into the ‘colonial knowledge’ system. For example, a set of diverse people that constituted the ‘tribals’ were classified as ‘brutal’. Of course, there were clear efforts here to focus specifically on some tribal groups such as the Kandhas (who supposedly practised human sacrifice), in order to construct homogenous ideas about tribes in general. Any simple effort to examine the colonial ‘terror strikes’ in the hills over the years between 1800 and 1860 would easily show how this was occasioned by a combination of fears and insecurities regarding the tribals, along with an eagerness to extend control and conquer the untapped resources of the region. And it was precisely here that the ‘civilizing mission’ was invoked to justify the brutal campaigns in the hills. In fact, this partially led to the creation of the ‘civilized’/‘uncivilized’ binary, which the colonial knowledge system oscillated between, providing the ‘rationale’ to either crush or romanticize the hill people (which included tribals and also large sections of untouchables) according to specific needs and contexts. Some historians tend to over-emphasize the role of colonialism when it comes to caste formation; while there is some justification for this, one needs to underline the fact that the pre-colonial order was also rooted in inequalities. This was altered, or intensified, over the course of the nineteenth century when land settlements united the colonial administration, the Brahminical order, and the propertied classes (comprising the princes and the landlords) in an enterprise that polarized caste/class equations.

5 Rendho Majhi (head of the Borikiya Kandhas of Kalahandi), Chakra Bisoi, legendary tribal leader; and Dharani Bhuyan (Bhuyan leader of Keonjhar) led major uprisings against the colonial authorities in the nineteenth century. See Chapter 3.

By the nineteenth century, a ‘tribe’ came to be seen not only as part of a particular type of society, but also a particular ‘stage of evolution’. A closely related assumption was that the tribe was an isolated, selfcontained, and primitive social formation. This was despite the fact that such arguments are difficult to sustain when it comes to the South Asian world, where interactions between the tribal/non-tribal people has had a long past.6 It needs to be emphasized that tribal communities were very much a part of the South Asian social reality at the time of India’s colonization. Besides, labels such as these drew upon the active participation and collaboration of the upper caste, Brahminical order. In addition, they were coloured by race theories of the West as well as by interactions with the pre-colonial ideas and institutions that were carried over in an altered form during colonial times. Equally significant were the colonial agrarian interventions and the commercialization of agriculture and the ways in which these impacted production processes and social structures. Given these complexities, the world of the tribals—which was far from being monolithic at the time of India’s colonization—underwent major shifts and changes over the course of the nineteenth century. Taken together, they were clearly responsible for reinforcing the structure of stratification. Whereas historians have tended to stress the anti-colonial dimension, what needs to be also studied is the way in which tribal society negotiated with itself, along with the shifts and changes that it went through. The outward manifestation of this process can be seen in various acts of resistance, but the deeper implications of this need to be explored and researched further.

UNPACKING COLONIAL STEREOTYPES

Although tribal society meant different things to different people by the nineteenth century, what gradually developed as a part of

6 See André Béteille, ‘The Idea of Indigenous People’, Current Anthropology, vol. 39, no. 2 (1998), 187–91; Virginius Xaxa, ‘Tribes as Indigenous People of India’, Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 34, no. 52 (1999), 3589–95; and Bengt G. Karlsson, ‘Anthropology and the “Indigenous Slot”: Claims to and Debates about Indigenous Peoples’ Status in India’, Critique of Anthropology, vol. 23, no. 4 (2003), 403–23.

‘common sense’ was its location on the fringes of sedentary, peasant society. For colonial rulers, the distance or closeness from caste Hindu peasant society with regard to social and cultural practices/ rituals seemed to have been the yardstick that determined how ‘uncivilized’/‘civilized’ a particular tribal community was. This served as the guiding rationale behind colonial officials’ perception of them as ‘wild’ people who needed to be ‘tamed’ or ‘civilized’. The effort to survey the tribes led to descriptive accounts that highlighted their distinctive character. In colonial documents and census reports, tribal people were often classed as ‘aborigines’ and ‘semi-Hinduized’ people, while pastoralists or nomads were located as ‘wandering tribes’ who needed to be ‘settled’. What was never seriously considered was the basis of the problem—namely the colonial inroads and the manner in which they unsettled a large section of people and thereby created and/or reinforced this phenomenon.7

Colonial officials and anthropologists were the pioneers who collected materials related to the lives of the tribal people and documented these through descriptive accounts.8 Here one cannot miss the fact that they were based on the interactions with the Brahminical order. Moreover, what might have started as a matter of curiosity did assume a serious dimension with the taking over of India by the Crown in 1858. This led to the beginning of the serious enterprise of acquiring knowledge in order to administer the tribals effectively—a process that was significantly reinforced during the census operations that were launched in the 1860s.9 By the end of the nineteenth century, with the experience of four census operations, colonial officialdom

7 For example, both Meena Radhakrishna, Dishonoured by History: ‘Criminal Tribes’ and British Colonial Policy (Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 2001) and Bhangya Bhukya, Subjugated Nomads: The Lambadas under the Rule of the Nizams (New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan, 2010) refer to the colonial logic of unsettling and then criminalizing nomadic people.

8 See, for example, E.T. Dalton, Descriptive Ethnology of Bengal (Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing, 1872), and E. Thurston, Anthropology of the Todas and Kotas of the Nilgiri Hills (Madras: Superintendent of Government Press, 1896).

9 The First Census Report was completed in 1871–2.

and Dalits in Orissa

could think of defining the category of the ‘tribe’. Thus, as H.H. Risley put it:

A tribe as we find in India is a collection of families or groups of families bearing a common name which as a rule does not denote any specific occupation; generally claiming common descent from a mythical or historical ancestor and occasionally from an animal, but in some parts of the country held together by the obligations of blood-feud than by the tradition of kinship; usually speaking the same language and occupying, professing, or claiming to occupy a definite tract of country. A tribe is not necessarily endogamous.10

Behind this was a serious enterprise that sought to make the ‘tribe’ definable. Beyond administrative needs, one can discern the idea of classifying tribes and seeing them differently from caste as the ‘guiding principle’ behind this effort. What is simultaneously observable is that early descriptive efforts gradually lost their fluidities and became polarized in order to incorporate typical stereotypes regarding the ‘brutal’ and ‘wild’ tribals. Fuelled and reinforced by the pressures of increasing racism over the 1850s and 1940s, this colonial knowledge system drew upon the discourses of ‘scientists’, ethnographers, colonial officials, travellers, and fiction writers, amongst others, to justify its positions.11

Certain typical aspects of colonial anthropology and classification strategy are discernible in the way the ‘tribal’ was constructed. This ranged from the glorification of the ‘ancient people of the east’ to emphasizing the essentially ‘brutal’ and ‘violent’ nature of the tribals. Of course, certain elements such as the image of the ‘violent tribal’ retains a level of unparalleled continuity. Colonial brutality associated with conquering the tribal tracts (or jungle mahals, forested hills and so on, as they were called) were often justified on the basis of presenting this negative image of the tribal. Interestingly, along with

10 H.H. Risley, Census of India, 1901, Vol. 1, Part 1 (Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing, 1903), 514.

11 Meena Radhakrishna explores some of these dimensions in ‘Of Apes and Ancestors: Evolutionary Science and Colonial Ethnography’, in Biswamoy Pati (ed.), Adivasis in Colonial India (New Delhi: Orient BlackSwan, 2011), 31–54.

other aspects, this construct stressed their violent nature on the basis of the ‘fact’ that they were always ‘armed’—namely with sticks, pickaxes, or bows and arrows. What needs to be articulated here is that these ‘weapons’ were as commonplace as the pistols and guns carried by colonial officials who toured forests and mountains, or the books, papers, and laptops carried by historians today. Additionally, these ideas about the ‘barbaric’ and ‘wild’ tribes were also reinforced by sections of the Oriya middle class, based on pre-existing fears and insecurities of the popular masses—a point that we shall look at more closely later in this chapter.

Besides, one needs to bear in mind the ambiguities and grey areas while drawing distinctions between the tribes and the untouchables. It is not unusual to find, in many official reports and archival sources, a tribal group being identified both as untouchables as well as a tribe.12

Consequently, one has to be careful about boundaries that seek to differentiate between the ‘tribes’ and untouchables/dalits. At the same time, the process of ‘integration’, which led to the incorporation of tribals into the Brahminical order of caste needs to be grasped as well. Although projected as a ‘harmonious’ affair that drew upon the method of colonial anthropology of situating tribes based on the similarities/dissimilarities with Brahminical caste society, the process was marked with complexities that ranged from brutal terror strikes that aimed to ‘civilise the Tribals’, to sections of the latter opting, in certain cases, to be incorporated as tribals. Here one has to be sensitive to see the process of conversions (which some scholars choose to call ‘integration’), predominantly to Brahminical Hinduism—a phenomenon that we shall examine in detail in Chapter 3.13

Simultaneously, the term ‘tribal’ (as well as Adivasi—namely, ancient people) needs to be substantially clarified while discussing

12 H.H. Risley, The Tribes and Castes of Bengal, Vols I and II (Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press, 1891), can be cited as a representative example where this is evident.

13 G.N. Dash refers to the absorption of tribals, over-emphasizes the ‘openness’ of the caste system, overlooks the exploitative aspects of the caste system in Orissa, and the dimensions of terror accompanying this process of caste consolidation: G.N. Dash, Hindus and Tribals: Quest for Co-Existence (New Delhi: Decent Books, 1998).

large sections of the populace like the Koyas, Mundas, Kandhas, or Santhals. The term ‘tribal’ was also a way of describing people who had distinct identities in terms of language, cultural bonds, and religion, including a certain commonality when it came to their economic life. As can be seen, this effort to define ‘tribes’ does not preclude features such as internal social differentiation as well as conflicts. One also needs to remember that there were large sections of the population in colonial India that were heavily forest-dependent, but were simultaneously involved in other activities, including agriculture. This particular aspect needs to be located in terms of its transitory logic that was premised on contradictory pressures. In many ways, these were connected to the twin pressures of growing encroachments on forests and the loss of land brought about by the zamindar–sahukar–sarkar nexus that was based on exploitation and was cradled and defended by the legal and administrative system introduced by colonialism. This implied a context that destabilized the agricultural systems of different tribal communities. In fact, a phenomenon that needs serious enquiry is the nature of the agricultural practices that remained transitory, caught as they were between shifting cultivation and forms of settled agriculture.

COLONIAL CONSTRUCTIONS OF THE ‘ CRIMINAL TRIBE ’

It is also necessary to foreground the manner in which ‘tribes’ and untouchables/dalits were stereotyped in the past (and indeed continue to be so in the present). As mentioned earlier, this was a phenomenon that marked the triumph of colonial anthropology but was also conditioned by sections of the colonized who provided the colonial ethnographers with ‘condensed’ courses on caste and its workings in Orissa.

These ideas and images were distinctly associated with the criminalization of the tribes and untouchables/dalits—a feature that has had a rather long afterlife.14 Alongside, though, it is clear that some of the ‘features’ associated with these groups today, though seen as

14 The Criminal Tribes Act was first enacted for north India in 1871 and was subsequently extended to the Bengal Province in 1876.

longstanding features of the past, are relative recent ‘inventions’. Besides revealing the continuation/dominance of a narrow, prejudiced mindset, they serve to justify and sustain what can only be seen as the post-colonial ‘civilising mission’. For instance, as late as the 1960s, P.K. Bhowmick, an anthropologist, began his study of the Lodha tribals by boldly noting that ‘the Lodhas of West Bengal, who ... live scattered in the western jungle-covered tracts of Midnapur ... were designated as one of the “criminal tribes” till the revocation of the practice by the Criminal Tribes Act of 1952’.15 Since Lodhas are also found in adjoining Orissa, Bhowmick’s observations are really noteworthy. While he admitted that ‘no correct information could be had about them excepting from Police records’ and that ‘they [had] to face some sort of social seclusion’, he nevertheless described them as ‘criminal-minded’, ‘extremely poor and at the same time reluctant to do hard labour’, noting that whenever a crime was committed near their settlement,‘they [were] generally suspected both by the local people and the Police Officers ... harassed and sent ... for trial’. He cited one particular episode in 1905, when goods were stolen, the cash spent and the food consumed ‘on the spot’. Noting that the overwhelming majority of those listed as ‘criminals’ ‘[had] no landed property at all’, he mentioned how Kanki, a 10-year-old girl who was arrested for stealing a brass cup (in 1953), who confessed to her ‘crime’, had admitted that she had been starving for two days after which she had stolen the cup and bought some food after selling it.16 Thus this study, in conveying several bits of interesting information, together with various omissions, biases,

15 Bhowmick’s survey revealed that out of the twenty-two Lodhas who changed residence, six did it to find employment, fourteen in order to escape police oppression, and two because of the fear of witchcraft and ghosts. Their daily food consumption: at 8 am they ate boiled rice that had been left to soak overnight, together with chillies and salt, while children ate stale curry or boiled roots; at 5 pm they consumed rice, pulses, curry, fish or meat, if available. Men drank small quantities of rice beer after a hard day’s work. See P.K. Bhowmick, Lodhas of West Bengal: A Socio-Economic Study (Calcutta: Punthi Pustak, 1963), 1.

16 Out of the forty-nine Lodhas who were arrested for the first crime they had committed, three were fifteen years, nine were sixteen years and six were eighteen years old. Bhowmick, Lodhas, ix, 21, 47, 266–8, and 275–6.