135. T�� G���� A�������: I�������� �� ���

V�����

More important was the spread of the Phœnician letters to an entirely foreign people, the Greeks, whose language was largely composed of different sounds and possessed a genius distinct from that of the Semitic tongues. The Greeks’ own traditions attest that they took over their alphabet from the Phœnicians. The fact of the transmission is corroborated by the form of the letters and by their order in the alphabet. It is also proved very prettily by the names of the letters. As we speak of the ABC, the Greeks spoke of the Alpha Beta—whence our word “alphabet.” Now “alpha” and “beta” mean nothing in Greek. They are obviously foreign names. In the Semitic languages, however, similar names, Aleph and Beth, were used for the same letters A and B, and meant respectively “ox” and “house.” Evidently these names were applied by the Semites because they employed the picture of an ox head to represent the first sound in the word Aleph, and the representation of a house to represent the sound of B in Beth. Or possibly the letters originated in some other way, and then, names for them being felt to be desirable, and the shape of the first rudely suggesting the outline of an ox’s head and

the second a house, these names were applied to the characters already in use.

The third letter of the alphabet, corresponding in place to our C and in sound to our G, the Greeks called Gamma, which is as meaningless as their Alpha and Beta. It is their corruption of Semitic Gimel, which means “camel” and may bear this name because of its resemblance to the head and neck of a camel. The same sort of correspondence can be traced through most of the remaining letters. From these names alone, then, even if nothing else were known about the early alphabets, it would be possible to prove the correctness of the Greek legend that they derived their letters from the Phœnicians. A people who themselves invented an alphabet would obviously name the letters with words in their own language, and not with meaningless syllables taken from a foreign speech.

The Greeks however did more than take over the alphabet from the Phœnicians. They improved it. An outstanding peculiarity of Semitic writing was that it dispensed with vowels. It represented the consonants fully and accurately, in fact had carefully devised letters for a number of breath and guttural sounds which European languages either do not contain or generally neglect to recognize. But, as if to compensate, the Semitic languages possess the distinctive trait of a great variability of vowels. When a verb is conjugated, when it is converted into a noun, and in other circumstances, the vowels change, only the consonants remaining the same, much as in English “sing” becomes “sang” in the past and “goose” changes to “geese” in the plural. Only, in English such changes are comparatively few, whereas in Semitic they are the overwhelming rule and quite intricate. The result of this fluidity of the vowels was that when the Semites invented their letters they renounced the attempt to write the vowels. Apparently they felt the consonants, the only permanent portions of their words, as a sort of skeleton, sufficient for an unmistakable outline. So, with their ordinary consonants, plus letters for J and V which at need could be made to stand for I and U, and the consistent employment of breaths and stops to indicate the presence or absence of vowels at the beginning and end of words, they managed to make their writing

readily legible. It was as if we should write: ’n Gd w’ trst or Ths wy ’t Even to-day the Bible is written and read in the Jewish synagogue by this vowelless system of three thousand years ago.

In the Greek language more confusion would have been caused by this system. Moreover, the alphabet came to the Greeks as something extraneous, so that they were not under the same temptation as the Phœnicians to follow wholly in the footsteps of the first generation of inventors. As a result, the Greeks took the novel step of adding vowel letters.

It is significant that what the Greeks did was not to make the new vowel signs out of whole cloth, as it were, out of nothing, but that they followed the method which is characteristic of invention in general. They took over the existing system, twisted and stretched it as far as they could, and created outright only when they were forced to. While the Phœnician alphabet lacked vowel signs, the Greeks felt that it had a superfluity of signs for breaths and stops. So they transformed the Semitic breaths and stops into vowels. Thus they satisfied the needs of their language; and incidentally added the capstone to the alphabet. It was the first time that a system of writing had been brought on the complete basis of a letter for every sound. All subsequent European alphabets are merely modifications of the Greek one.

The first of the Semitic letters, the Aleph, stood for the glottal stop, a check or closure of the glottis in which the vocal cords are situated; a sound that occurs, although feebly, between the two o’s in “coördinate” when one articulates distinctly. In the Semitic languages this glottal stop is frequent, vigorous, and etymologically important, wherefore the Semites treated it like any other consonant. The Greeks gave it a new value, that of the vowel A. Similarly they transformed the value of the symbols for two breath sounds, a mild and a harsh H, into short and long E, which they called Epsilon and Eta. Their O is made over from a Semitic guttural letter, while for I the Semitic ambiguous J-I was ready to hand. U, written Y by the Greeks, is a dissimilated variant of F, both being derived from Semitic Vau or the sixth letter with the value of V or U. The vocalic form was now put at the end of the alphabet, which previously had

ended with T Its consonantal double, F, later went out of use in Greek speech and was dropped from the alphabet.

136. S������� �� ��� I��������

The Greeks did not make these alterations of value all at once. The value of several of the letters fluctuated in the different parts of Greece for two or three centuries. In one city a certain value or form of a letter would come into usage; in another, the same letter would be shaped differently, or stand for a consonant instead of a vowel. Thus the character H was long read by some of the Greeks as H, by others as long E. This fact illustrates the principle that the Greek alphabet was not an invention which leaped, complete and perfect, out of the brain of an individual genius, as inventions do in film plays and romantic novels, and as the popular mind, with its instinct for the dramatic, likes to believe. One might imagine that with the basic plan of the alphabet, and the majority of its symbols, provided readymade by the Phœnicians, it would have been a simple matter for a single Greek to add the finishing touches and so shape his national system of writing as it has come down to us. In fact, however, these little finishing touches were several centuries in the making; the final result was a compromise between all sorts of experiments and beginnings. One can picture an entire nationality literally groping for generation after generation, and only slowly settling on the ultimate system. There must have been dozens of innovators who tried their hand at a modification of the value or form of a letter.

Nor can it be denied that what was new in the Greek alphabet was a true invention. The step of introducing full vowel characters was as definitely original and almost as important as any new progress in the history of civilization. Yet it is not even known who the first individual was that tried to apply this idea. Tradition is silent on the point. It is quite conceivable that the first writing of vowels may have been independently attempted by a number of individuals in different parts of Greece.

137. T�� R���� A�������

The Roman alphabet was derived from the Greek. But it is clear that it was not taken from the Greek alphabet after this had reached its final or classic form. If such had been the case, the Roman letters, such as we still use them, would undoubtedly be more similar to the Greek ones than they are, and certain discrepancies in the values of the letters, as well as in their order, would not have occurred. In the old days of writing, when a number of competing forms of the alphabet still flourished in the several Greek cities, one of these forms, developed at Chalcis on Eubœa and allied on the whole to those of the Western Hellenic world, was carried to Italy There, after a further course of local diversification, one of its subvarieties became fixed in the usage of the inhabitants of the city of Rome. Now the Romans at this period still pronounced the sound H, which later became feeble in the Latin tongue and finally died out. On the other hand the distinction between short and long (or close and open) E, which the Greeks after many experiments came to recognize as important in their speech, was of no great moment in Latin. The result was that whereas classic Greek turned both the Semitic H’s into E’s, Latin accepted only the first of these modifications, that one affecting the fifth letter of the alphabet, whereas the other H, occupying the eighth place in the alphabetic series, continued to be used by the Romans with approximately its original Semitic value. This retention, however, was possible because Greek writing was still in a transitional, vacillating stage when it reached the Romans. The Western Greek form of the alphabet that was carried to Italy was still using the eighth letter as an H; so that the Romans were merely following their teachers. Had they based their letters on the “classic” Greek alphabet which was standardized a few hundred years later, the eighth as well as the fifth letter would have come to them with its vowel value crystallized. In that case the Romans would either have dispensed altogether with writing H, or would have invented a totally new sign for it and probably tacked it on to the end of the alphabet, as both they and the Greeks did in the case of several other letters.

The net result is the curious one that whereas the Roman alphabet is derived from the Greek, and therefore subsequent, it remains, in

this particular matter of the eighth letter, nearer to the original Semitic alphabet.

There are other letters in the Roman alphabet which corroborate the fact of its being modeled on a system of the period when Greek writing still remained under the direct influence of Phœnician. The Semitic languages possessed two K sounds, usually called Kaph and Koph, or K and Q, of which the former was pronounced much like our K and the latter farther back toward the throat. The Greeks not having both these sounds kept the letter Kaph, which they called Kappa, and gradually discarded Koph or Koppa. Yet before its meaning had become entirely lost, they had carried it to Italy. There the Romans seized upon it to designate a variety of K which the Greek dialects did not possess, namely KW; which is of course the phonetic value which the symbol Q still has in English. The Romans were reasonable in this procedure, for in early Latin the Q was produced with the extreme rear of the tongue, much like the original Koph.

138. L������ �� N������ S����

In later Greek, Koph remained only as a curious survival. Although not used as a letter, it was a number symbol. None of the ancients possessed pure numeral symbols of the type of our “Arabic” ones. The Semites and the Greeks employed the letters of the alphabet for this purpose, each letter having a numeral value dependent on its place in the alphabet. Thus A stood for 1, B for 2, C or Gamma for 3, F for 6, I for 10, K for 20 and so on. As this series became established, Q as a numeral denoted 90; the Greeks, long after they had ceased writing Q as a letter, used it with this arithmetical value. Once it had acquired a place in the series, it would have been far too confusing to drop. With Q omitted, R would have had to be shifted in its value from 100 to 90. One man would have continued to use R with its old value, while his more new-fashioned neighbor or son would have written it to denote ten less. Arithmetic would have been as thoroughly wrecked as if we should decide to drop out the figure 5 and write 6 whenever we meant 5, 7 to express 6, and so on. Habit

in such cases is insuperable. No matter how awkward an established system becomes, it normally remains more practical to retain with its deficiencies than to replace by a better scheme. The wrench and cost of reformation are greater, or are felt to be greater by each generation, than the advantages to be gained.

139. R����� �� I�����������

This is one reason why radical changes are so difficult to bring about in institutions. These are social and therefore in a sense arbitrary. In mechanical or “practical” matters people adjust themselves to the pressure of new conditions more quickly. If a nation has been in the habit of wearing clothing of wool, and this material becomes scarce and expensive, some attempt will indeed be made to increase the supply of wool, but if production fails to keep pace with the deficiency, cotton is substituted with little reluctance. If, on the other hand, a calendar becomes antiquated, which could be changed by a simple act of will, by the mere exercise of community reason, a tremendous resistance is encountered. Time and again nations have gone on with an antiquated or cumbersome calendar long after any mediocre mathematician or astronomer could have devised a better one. It is usually reserved for an autocratic potentate of undisputed authority, a Cæsar or a Pope, or for a cataclysm like the French and Russian revolutions, to institute the needed reform As long as men are concerned with their bodily wants, those which they share with the lower animals, they appear sensible and adaptable. In proportion however as the alleged products of their intellects are involved, when one might most expect foresight and reason and cool calculation to be influential, societies seem swayed by a conservatism and stubbornness the strength of which looms greater as we examine history more deeply.

Of course, each nation and generation regards itself as the one exception. But irrationality is as easy to discern in modern institutions as in ancient alphabets, if one has a mind to see it. Daylight saving is an example very near home. For centuries the peoples of western civilization have gradually got out of bed, breakfasted, worked,

dined, and gone to sleep later and later, until the middle of their waking day came at about two or three o’clock instead of noon. The beginning of the natural day was being spent in sleep, most relaxation taken at night. This was not from deliberate preference, but from a species of procrastination of which the majority were unintentionally guilty. Finally the wastefulness of the condition became evident. Every one was actually paying money for illumination which enabled him to sit in a room while he might have been amusing himself gratis outdoors. Really rational beings would have changed their habits—blown the factory whistle at seven instead of eight, opened the office at eight instead of nine, gone to the theater at seven and to bed at ten. But the herd impulse was too strong. The individual that departed from the custom of the mass would have been made to suffer. The first theater opening at seven would have played to empty chairs. The office closing at four would have lost the business of the last hour of the day without compensation from the empty hour prefixed at the beginning. The only way out was for every one to agree to a self-imposed fiction. So the nations that prided themselves most on their intelligence solemnly enacted that all clocks be set ahead. Next morning, every one had cheated himself into an hour of additional daylight, and the illuminating plant out of an hour of revenue, without any one having had to depart from established custom; which last was evidently the course actually to be avoided at all hazards.

Of course, most individual men and women are neither idiotic nor insane. The only conclusion is that as soon and as long as people live in relations and act in groups, something wholly irrational is imposed on them, something that is inherent in the very nature of society and civilization. There appears to be little or nothing that the individual can do in regard to this force except to refrain from adding to its irrationality the delusion that it is rational.

140. T�� S���� ��� S������ L������

The letters, such as Q, in which the Roman alphabet is in agreement with the original Semitic one and differs from classic

Greek writing, might lead, if taken by themselves, to the conjecture that the ancient Italians had perhaps not derived their alphabet via the Greeks at all, but directly from the Phœnicians. But this conclusion is untenable: first, because the forms of the earliest Latin and Greek letters are on the whole more similar to each other than to the contemporaneous Semitic forms; and second because of the deviations from the Semitic prototype which the Latin and Greek systems share with each other, as in the vowels.

The sixth letter of the Roman alphabet, F, the Semitic Waw or Vau, is wanting in classic Greek, although retained in certain early and provincial dialects. One of the brilliant discoveries of classical philology was that the speech in which the Homeric poems were originally composed still possessed this sound, numerous irregularities of scansion being explainable only on the basis of its original presence. The letter for it looked like two Greek G’s, one set on top of the other. Hence, later when it had long gone out of use except as a numeral, it was called Di-gamma or “double-G.”

The seventh Semitic letter, which in Greek finally became the sixth on account of the loss of the Vau or Digamma, was Zayin, Greek Zeta, our Z. This, in turn, the Romans omitted, because their language lacked the sound. They filled its place with G, which in Phœnician and Greek came in third position. The shift came about thus. The earliest Italic writing followed the Semitic and Greek original and had C, pronounced G, as its third letter. But in Etruscan the sounds K and G were hardly distinguished. K therefore went out of use; and the early Romans followed the precedent of their cultured and influential Etruscan neighbors. For a time, therefore, the single character C was employed for both G and K in Latin. Finally, about the third century before Christ, a differentiation being found desirable, the C was written as C when it stood for the “hard” or voiceless sound K, but with a small stroke, as G, when it represented the soft or voiced sound; and, the seventh place in the alphabet, that of Z, being vacant, this modified character was inserted. Thus original C, pronounced G, was split by the Latins into two similar letters, one retaining the shape and place in the alphabet of Gimel-

Gamma, the other retaining the sound of Gamma but displacing Zeta.

But the letter Z did not remain permanently eliminated from western writing. As long as the Romans continued rude and selfsufficient, they had no need of a character for a sound which they did not speak. When they became powerful, expanded, touched Greek civilization, and borrowed from this its literature, philosophy, and arts, they took over also many Greek names and words. As Z occurred in these, they adopted the character. Yet to have put it in its original seventh place which was now occupied by G, would have disturbed the position of the following letters. It was obviously more convenient to hang this once rejected and now reinstated character on at the end of the alphabet; and there it is now.

141. T�� T���

�� ���

A�������

In fact, the last six letters of our alphabet are additions of this sort. The original Semitic alphabet ended with T U was differentiated by the Greeks from F to provide for one of their vowel sounds. This addition was made at an early enough period to be communicated to the Romans. This nation wrote U both for the vowel U and the consonantal or semi-vowel sound of our W. To be exact, they did not write U at all, but what we should call V, pronouncing it sometimes U and sometimes W. They spelled cvm, not cum.

Later, they added X. An old Semitic S-sound, in fifteenth place in the alphabet and distinct from the S in twenty-first position which is the original of our S, was used for both SS and KS. In classic Greek, one form, with KS value, maintained itself in its original place. In other early Græco-Italic alphabets, the second form, with SS value, kept fifteenth place and the X or KS variant was put at the end, after U. The SS letter later dropped out because it was not distinguished in pronunciation from S.

The Y that follows X is intrinsically nothing but the U which the Romans already had—a sort of double of it. The Greek U however was pronounced differently from the Latin one—like French U or

German ü. The literary Roman felt that he could not adequately represent it in Greek words by his own U. He therefore took over the U as the Greeks wrote it—that is, a reduced V on top of a vertical stroke. This character naturally came to be known as Greek U; and in modern French Y is not simply called “Y,” as in English, but “Ygrec,” that is, “Greek Y.”

With Z added to U (V), X, and Y, the ancient Roman alphabet was completed.

Our modern Roman alphabet is however still fuller. The two values which V had in Latin, that of the vowel U and the semi-vowel W, are so similar that no particular hardship was caused through their representation by the one character. But in the development of Latin from the classic period to mediæval times, the semi-vowel sound W came to be pronounced as the consonant V as we speak it in English. This change occurred both in Latin in its survival as a religious and literary tongue, and in the popularly spoken Romance languages, like French and Italian, that sprang out of Latin. Finally it was felt that the full vowel U and the pure consonant V were so different that separate letters for them would be convenient. The two forms with rounded and pointed bottom were already actually in use as mere calligraphic variants, although not distinguished in sound, V being usually written at the beginning of words, U in the middle. Not until after the tenth century did the custom slowly and undesignedly take root of using the pointed letter exclusively for the consonant, which happened to come most frequently at the head of words, and the rounded letter for the vowel which was commoner medially.

In the same way I and J were originally one letter. In the original Semitic this stood for the semi-vowel J (or “Y” as in yet); in Greek for the vowel I; in Latin indifferently for vowel or semi-vowel, as in Ianuarius. Later, however, in English, French, and Spanish speech, the semi-vowel became a consonant just as V had become. When differentiation between I as vowel and as consonant seemed necessary, it was effected by seizing upon a distinction in form which had originated merely as a calligraphic flourish. About the fifteenth century, I was given a round turn to the left, when at the beginning of words, as an ornamental initial. The distinction in sound value came

still later The forms I and J were kept together in the alphabet, as U and V had been, the juxtaposition serving as a memento of their recency of distinction—like the useless dot over small j. Had the people of the Middle Ages still been using the letters of the alphabet for numerical figures as did the Greeks, they would undoubtedly have found it more convenient to keep the order of the old letters intact. J and U would in that case almost certainly have been put at the end of the alphabet instead of adjacent to I and V.

J presents a survival—a significant anachronism. Although now recognized in the alphabet, the letter is not always accorded its full place in the series; now and then it is treated like an adopted child whose position in the family is somewhat subsidiary. When a continental European uses letters to designate rows of chairs in a theater, paragraph headings in a book, a series of shipping marks, or any other listing, he often omits J, passing directly from I to K as a Roman of two thousand years ago would have done. Americans occasionally do the same: in Washington, K street follows directly on I street. If asked the reason, we perhaps rationalize the omission on the ground that I and J look so much alike that they run risk of being confused. Yet it scarcely occurs to us that I and L, or I and T, can also be easily confused. The true cause of the habit seems to be the unconscious one that our ancestors, in using the letters seriatim, followed I by K because they had no J.

The origin of W is accounted for by its name, “Double-U,” and by its form, which is that of two V’s. The old Latin pronunciation of V gradually changed from W to V, and many of the later European languages either contained no W-sound or indicated it by the device of writing U or some combination into which U entered Thus the French write OU and the Spanish HU for the sound of W. In English, however, and in a few other European languages, the semi-vowel sound was important enough to make a less circumstantial representation advisable. Since the sound of the semi-vowel was felt to be fuller than that of the consonant, a new letter was coined for the former by coupling together two of the latter. This innovation did not begin to creep into English until the eleventh century. Being an outgrowth of U and V, W was inserted after them as J was after I. It

is a slight but interesting instance of convergence that its name is exactly parallel to the name “Double Gamma” which the Greek grammarians coined for F long before.

142. C������� ��� M���������

The distinction between capitals and “small” letters is one which we learn so early in life that we are wont to take it as something selfevident and natural. Yet it is a late addition in the history of the alphabet. Greeks and Romans knew nothing of it. They wrote wholly in what we should call capital letters. If they wanted a title or heading to stand out, they made the letters larger, but not different in form. The same is done to-day in Hebrew and Arabic, and in fact in all alphabets except those of Europe.

Our own two kinds or fonts of letters, the capital and “lower case” or “minuscule,” are more different than we ordinarily realize. We have seen them both so often in the same words that we are likely to forget that the “A” differs even more in form than in size from “a,” and that “b” has wholly lost the upper of the two loops which mark “B.” In late Imperial Roman times the original “capital” forms of the letters were retained for inscriptional purposes, but in ordinary writing changes began to creep in. These modifications increased in the Middle Ages, giving rise first to the “Uncial” and then to the “Minuscule” forms of the letters. Both represent a cursive rather than a formal script. The minuscules are essentially the modern “small” letters. But when they first developed, people wrote wholly in them, reserving the older formal capitals for chapter initials. Later, the capitals crept out of their temporary rarity and came to head paragraphs, sentences, proper names, and in fact all words that seemed important. Even as late as a few centuries ago, every English noun was written and printed with a capital letter, as it still is in German. Of course little or nothing was gained by this procedure. In many sentences the significant word must be a verb or adjective; and yet, according to the arbitrary old rule, it was the noun that was made to stand out.

To-day we still feel it necessary in English to retain capitals for proper names. It is certain that a suggestion to commence these also with small letters would be met with the objection that a loss of clearness would be entailed. As a matter of fact, the cases in which ambiguity between a common and proper noun might ensue would be exceedingly few; the occasional inconvenience so caused would be more than compensated for by increased simplicity of writing and printing. Every child would learn its letters in little more than half the time that it requires now. The printer would be able to operate with half as many characters, and typewriting machines could dispense with a shift key. French and Spanish designate proper adjectives without capitals and encounter no misunderstanding, and all English telegrams are sent in a code that makes no distinction. When we read the newspaper in the morning and think that the mixture of capital and small letters is necessary for our easy comprehension of the page, we forget that this same news came over the wire without capitals.

143. C����������� ��� R��������������

The fact is that we have become so habituated to the existing method that a departure from it might temporarily be a bit disconcerting. Consequently we rationalize our cumbersome habit, taking for granted or explaining that this custom is intrinsically and logically best; although a moments objective reflection suffices to show that the system we are so addicted to costs each of us, and will cost the next generation, time, energy, and money without bringing substantial compensation.

It is true that this waste is distributed through our lives in small driblets, and therefore is something that can be borne without seeming inconvenience. Civilization undoubtedly can continue to thrive even while it adheres to the antiquated and jumbling method of mixing two kinds of letters where one is sufficient. Yet the practice illustrates the principle that the most civilized as the most savage nations assert and believe that they adhere to their institutions after an impartial consideration of all alternatives and in full exercise of

wisdom, whereas analysis regularly reveals them as astonishingly resistive to alteration whether for better or worse.

If our capital letters had been purposely superadded to the small ones as a means of distinguishing certain kinds of words, a modern claim that they were needed for this purpose could perhaps be accepted. But since the history of the alphabet shows that the capital letters are the earlier ones, that the small letters were for centuries used alone, and that systems of writing have operated and operate without the distinction, it is clear that utility cannot be the true motive. The employment of capital letters as initials originated in a desire for ornamentation. It is an embroidery, the result of a play of the æsthetic sense. It is the use of capitals that has caused the false sense of their need, not necessity that has led to their use.

144. G�����

Another exemplification of how tenaciously men cling to the accustomed at the expense of efficiency, is provided by the “BlackLetter” or “Gothic” alphabet used in Germany and Scandinavia. This is nothing but the Roman letters as elaborated by the manuscriptcopying monks of northern Europe toward the end of the Middle Ages, when a book was as much a work of art as a volume of reading matter. The sharp angles, double connecting strokes, goosequill flourishes, and other increments of the Gothic letters undoubtedly possess a decorative effect, although an over-elaborate one. They were evolved in a period when a copyist cheerfully lettered for a year in producing a volume, and the lord or bishop into whose hands it passed was as likely to turn the leaves in admiration of the black and red characters as to spend time in reading them.

When printing was introduced, the first types were the intricate and angular Gothic ones customary in Germany. The Italians, who had always been half-hearted about the Gothic forms, soon revolted. Under the influence of the Renaissance and its renewed inspiration from classical antiquity, they reverted as far as possible to the ancient shapes of the characters. Even the mediæval small letters were simplified and rounded as much as possible to bring them into

accord with the old Roman style. From Italy these types spread to France and most other European countries, including England, which for the first fifty years had printed in Black-Letter. Only in north central Europe did the Gothic forms continue to prevail, although even there all scientific books have for some time been printed in the Roman alphabet. Yet Germans sometimes complain of the “difficulty” of the Roman letters, and books intended for popular sale, and newspapers, go into Gothic. There can be little doubt that in time the Roman letters will dispossess the Gothic ones in Germany and Scandinavia except for ornamental display heads. But the established ways die hard; Gothic letters may linger on as the “oldstyle” calendar with its eleven-day belatedness held out in England until 1752 and in Russia until 1917.

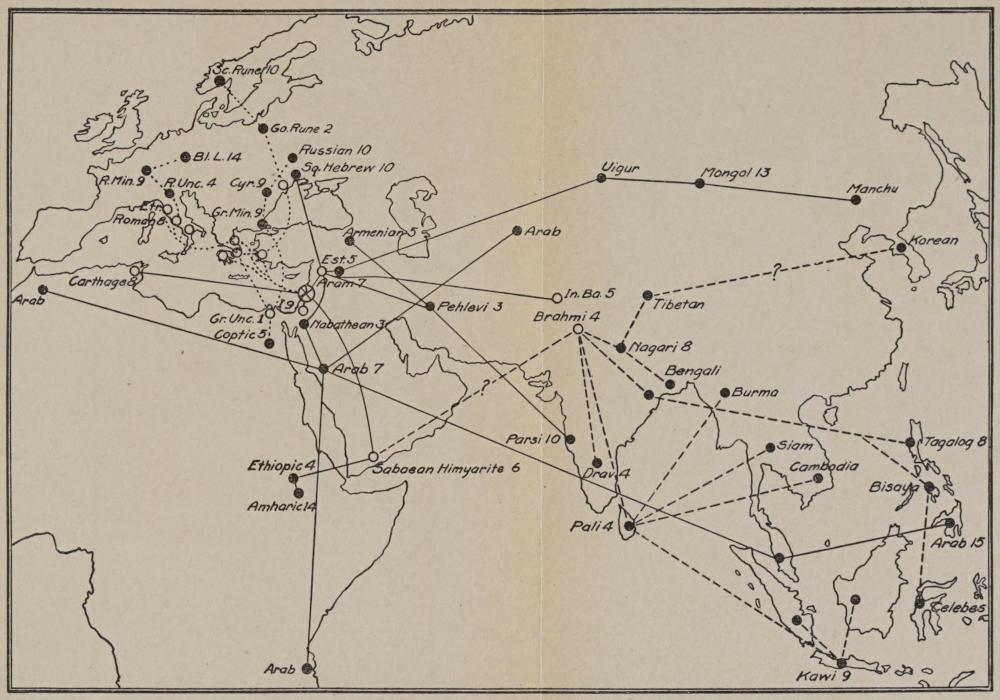

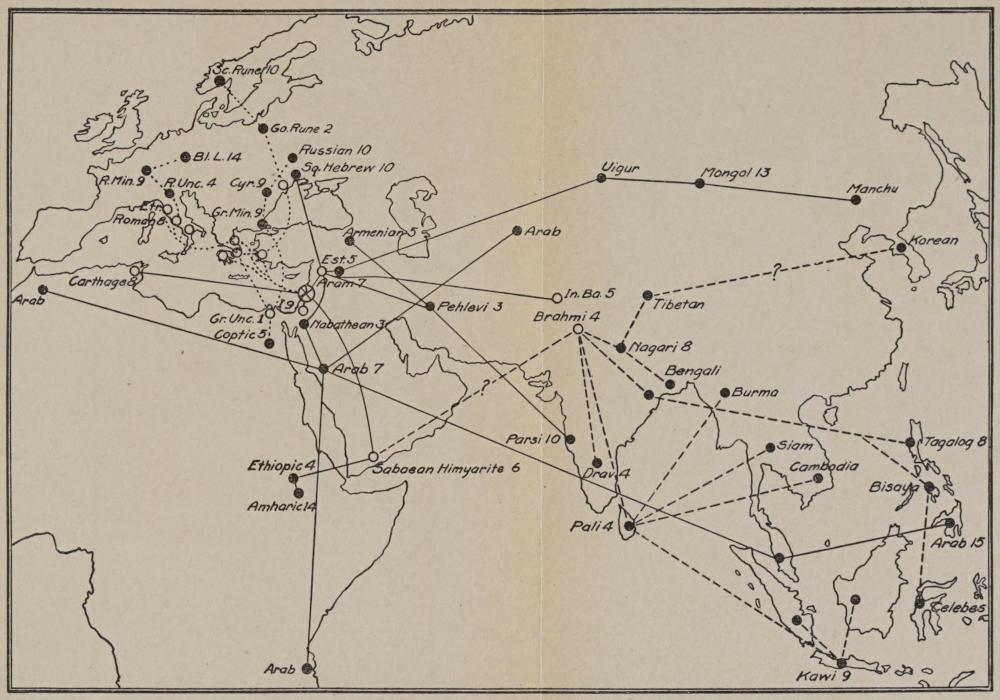

F��. 30. The spread of alphabetic writing. Course of Occidental alphabets in dotted lines; West Asiatic, continuous lines; Indic, broken lines. The numbers stand for centuries: with hollow circles, before Christ; with solid circles, after Christ. Crossed circle, point of origin, Phœnicia, 11th century B.C. Abbreviations: Aram, Aramæan; Bl L, Black Letter (Gothic); Cyr, Cyrillic; Est, Estrangelo; Etr,

Etruscan; Go, Gothic (Runes); Gr Min, Unc, Greek Minuscule, Uncial; In Ba, Indo-Bactrian (Kharoshthi); I, Israelite; R Min, Unc, Roman Minuscule, Uncial; Sc, Scandinavian (Rune) The flow was often back and forth; compare the 2,000 year development from Phœnician to Ionian to Athens to Alexandria (Uncial) to Constantinople (Minuscule) to Russian; or from Phœnician northward to Aramæan, thence south to Nabathean and Arabic, east to Pehlevi and back west to Armenian

145. H����� ��� A�����

Only a small part of the history of the alphabet was unfolded in Europe, where the seemingly so different forms of writing that have been discussed are after all only fairly close variants of the early Greek letters. In Asia the alphabet underwent more profound changes.

The chief modern Semitic alphabets, Hebrew and Arabic, are considerably more altered from the primitive Semitic or Phœnician than is our own alphabet. The Hebrew letters were slowly evolved, during the first ten centuries after Christ, under influences which have turned most of them as nearly as possible into parts of squarish boxes. B and K, M and S, G and N, H and CH and T, D and V and Z and R are shaped as if with intent to look alike rather than different. Arabic, on the other hand, runs wholly to curves: circles, segments of circles, and round flourishes; and several of its letters have become identical except for diacritical marks. If we put side by side the corresponding primitive Semitic, the modern English, the Hebrew, and the Arabic letters, it is at once apparent that in most cases English observes most faithfully the 3,000-years old forms. The cause of these changes in Hebrew and Arabic is in the main their derivation from alphabets descended from the Aramæan alphabet, a form of script that grew up during the seventh century B.C. in Aram to the northeast of Phœnicia. The Aramæans were Semites and therefore kept to the original value of the Phœnician letters more closely than the Greeks and Romans. On the other hand, they employed the alphabet primarily for business purposes and rapidly altered it to a cursive form, in which the looped or enclosing letters like A, B, D were opened and the way was cleared for a series of

increasing modifications. Greek and Roman writing, on the other hand, were at first used largely in monumental, dedicatory, legal, and religious connections, and preserved clarity of form at the expense of rapidity of production.

One feature of primitive Semitic, most Asiatic alphabets retained for a long time: the lack of vowel signs. In the end, however, representation of the vowels proved to be so advantageous that it was introduced. Yet the later Semites did not follow the Greek example of converting dispensable consonantal signs into vocalic ones. They continued to recognize consonant signs as the only real letters, and then added smaller marks, or “points” as they are called, for the vowels. These points correspond more or less to the grave, acute, and circumflex accents which French uses to distinguish vowel shades or qualities, é, è, ê, and e, for instance; and to the double dot or diæresis which German puts upon its “umlaut” vowels, as to distinguish ä (= e) from a. There is this difference, however: whereas European points are reserved for minor modifications, Hebrew and Arabic have no other means of representing vowels than these points. The vowels therefore remain definitely subsidiary to the consonants; to the extent of this deficiency Hebrew has adhered more closely to the primitive Semitic system than have we.

The reason for this difference lies probably in the fact that Hebrew and Arabic have retained virtually all the consonants of ancient Semitic. Hence the breaths and stops could not be dispensed with, or at least such was the feeling of their speakers. In the IndoEuropean languages, these sounds being wanting, the transformation of the superfluous signs into the letters needed for the vowels was suggested to the Greeks. The step perfecting the alphabet was therefore taken by them not so much because they possessed originality or specially fertile imagination, as because of the accident that their speech consisted of sounds considerably different from those of Semitic. Perhaps the Greeks once complained of the unfitness of the Phœnician alphabet, and adjusted it to their language with grumblings. Had they been able to take it over unmodified, as the Hebrews and Arabs were able, it is probable that they would cheerfully have done so with all its imperfection. In

that case they, and after them the Romans, and perhaps we too, would very likely have gone on writing only consonants as full letters and representing vowels by the Semitic method of subsidiary points. In short, even so enterprising and innovating a people as the Greeks are generally reputed to have been, made their important contribution to the alphabet less because they wished to improve it than because an accident of phonetics led them to find the means. Such are the marvels of human invention when divested of their romantic halo and examined objectively.

146. T�� S����� E�������: ��� W������ ��

I����

The diffusion of the alphabet eastward from its point of origin was even greater than its spread through Europe. Most of this extension in Asia is comprised in two great streams. One of these followed the southern edge of the continent. This was a movement that began some centuries before Christ, and often followed water routes. The second flow was mainly post-Christian and affected chiefly the inland peoples of central Asia.

India is the country of most importance in the development of the south Asiatic alphabets. The forms of the Sanskrit letters show that they and the subsequent Hindu alphabets are derivatives, though much altered ones, from the primitive Semitic writing. Exactly how the alphabet was carried from the shore of the Mediterranean to India has not been fully determined. By some the prototype of the principal earliest Indian form of writing is thought to have been the alphabet of the south Arabian Sabæans or Himyarites of five or six hundred years B.C. As the Arabs were Semites, and as there was a certain amount of commerce up and down the Red Sea, it is not surprising that even these rather remote and backward people had taken up writing. Between south Arabia and India there was also some intercourse, so that a further transmission by sea seems possible enough. Another view is that Hindu traders learned and imported a north Semitic alphabet perhaps as early as during the seventh century, from which the Brahmi was made over, from which

in turn all living Indian alphabets are derived. Besides this main importation, there was another, from Aramæan sources, which gave rise to a different form of Hindu writing, the Kharoshthi or IndoBactrian of the Punjab, which spread for a time into Turkistan but soon died out in India.