A Distant Rainbow

There’s an old proverb that tells how all nations are slaves to imaginings about their origins, blind pride in their finest hours, pure joy in those moments when it’s said extraordinary things were achieved that others thought beyond reach. India is no exception to this time-tested truism. The story runs like this: back in the midtwentieth century, against formidable odds, the people and leaders of India courageously mobilized to snap the chains of imperial domination and set out on the rough road to democracy. They built a democracy that’s today not only the planet’s biggest, but a democracy that breathed fresh life into its ideals and boosted India’s global reputation as a country that survived a murderous Partition, defeated an empire and blessed the fortunes of self-government by its people, and for its people, in radiant style.

Like other national stories, India’s rests on a belief in a beginning that ranks as the beginning of beginnings: that magical moment of birth of Indian democracy, just before sunset on the 14 August 1947, when the Indian tricolour was raised over the old imperial Parliament, to flutter in the late-monsoon Delhi sky, blessed by a distant rainbow. Later that evening, just before midnight, runs the founding story, Jawaharlal Nehru, boyishly slim, dressed in a white achkan with a red rose in his lapel, stood before the Constituent Assembly to declare that the half-century struggle for full independence from British rule was finally over.The four-and-a-half minute speech by Nehru is said to be among the most compelling made by any modern world leader.

Nehru’s words combined humility with ambition and the yearning, expressed in formal English spoken with an upper-class accent, to start something new in a world broken and battered by war, cruelty, and domination. ‘It is fitting’, he said forcefully, into the All India Radio microphone, ‘that at this solemn moment we take the pledge of dedication to the service of India and her people and to the still larger cause of humanity.’ The world was now One World, he continued. Peace and freedom had become indivisible. Local disasters now produced global effects. Beginning with India, democracy thus had to be brought to the world, so that power and freedom were exercised responsibly. ‘Long years ago’, he said, ‘we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially.’ He added: ‘This is no time for ill-will or blaming others. We have to build the noble mansion of free India where all her children may dwell.’

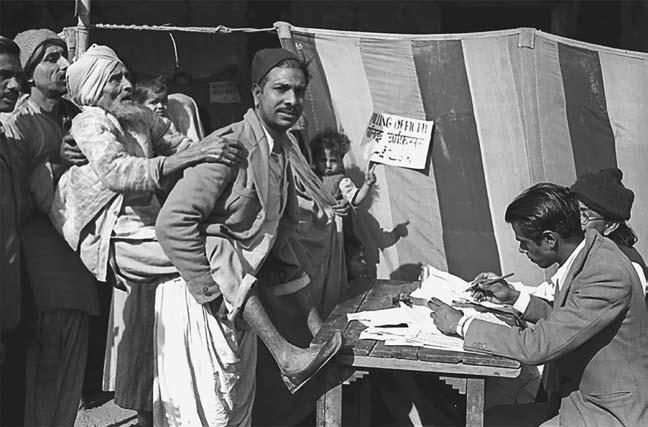

The allegory of India’s tryst with democracy notes the formidable obstacles confronting its transition from a trampled British colony to a proud power-sharing democracy. Nehru and his Congress party envisaged an Asian democracy that wasn’t simply a replica of the West. It had to solve two problems at once. The new democracy had to snap the chains imposed from the outside by its colonial masters; and unpick the threads of colonial domination at home by creating a new nation of equally dignified citizens of diverse backgrounds. Democracy was neither a gift of the Western world nor uniquely suited to Indian conditions. India was in fact a laboratory featuring a first-ever experiment in creating national unity, economic growth, religious toleration, and social equality out of a vast and polychromatic reality, a social order whose inherited power relations, rooted in the hereditary Hindu caste status, language hierarchies, and accumulated wealth, were to be transformed by the constitutionally guaranteed counter-power of public debate, multiparty competition, and periodic elections (Figure 1).

Efforts to build an Indian democracy are said to have done more than transform the lives of its people. India fundamentally altered the

nature of representative democracy itself. During the first several decades after independence, a new ‘post-Westminster’ type of democracy resulted, in the process slaughtering quite a few goats of prejudice. None of the standard political science postulates about the prerequisites of democracy survived. They had spoken of economic growth as its fundamental precondition, so that free and fair elections could be practicable only when sufficient numbers of people owned or enjoyed such commodities as automobiles, refrigerators, and wirelesses. Weighed down by destitution of heart-breaking proportions, the country managed to laugh in the face of academic insistence that there was a causal—perhaps even mathematical—link between economic development and political democracy. Millions of poor and illiterate people rejected the imperial and pseudo-scientific prejudice that a country must first be deemed materially fit for democracy. Struggling against poverty, they decided instead that they must become materially fit through democracy.

This was a change of epochal significance, say those who tell the India Story, as it’s been called.1 In contrast to post-1949 China and

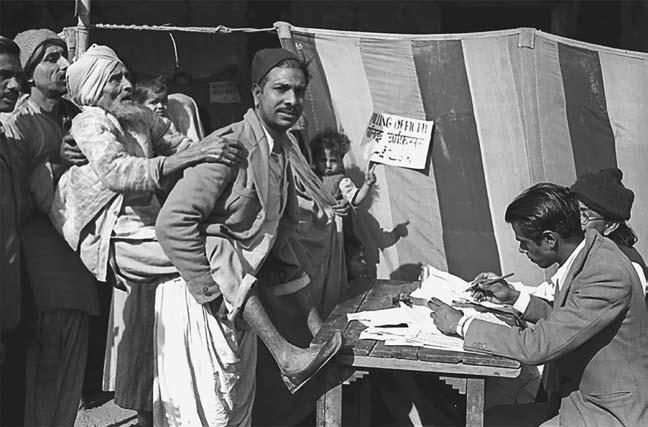

Figure 1. A polling station in Delhi, 1952, during the first general election

many postcolonial countries, India’s transition to democracy did not just show that Mugabe- and Stroessner-style dictatorship and military rule were unnecessary in the so-named Third World. Indian democrats proved that political unity within a highly diverse country could be built by respecting its social differences. They showed, despite everything, that the hand of democracy could come to include potentially billions of people defined by a huge variety of histories and customs that had one thing in common: they were people who were not Europeans, and did not want to be ruled by them. In this way, the region defied the common-sense rule of the white sahibs of Britannia that democracy takes root only where there’s a demos bound together by a common culture. Churchill had said so repeatedly. In contrast, say, to the colonies of Australia or Canada, India was the white man’s burden, he insisted, a muddled place that was immune to purposeful change in the Western way, which meant that the British were condemned to play the role of custodians of a pagan wilderness in need of law and order. ‘The rescue of India from ages of barbarism, tyranny, and intestine war, and its slow but ceaseless forward march to civilisation constitute the finest achievement of our history’, he crowed. Then he grumped. ‘India is an abstraction’, he said, ‘a geographical term. It is no more a united nation than the Equator.’ This fact posed a special difficulty.

There are scores of nations and races in India and hundreds of religions and sects. Out of the three hundred and fifty millions of Indians only a very few millions can read or write, and of these only a fraction are interested in politics and Western ideas. The rest are primitive people absorbed in the hard struggle for life.

Hence India had no democratic future. It was preposterous to suppose that ‘the almost innumerable peoples of India would be likely to live in peace, happiness and decency under the same polity and the same form of Government as the British, Canadian or Australian democracies.’2 Indian democrats rejected such poppycock. They instead thought of India as a society brimming with different hopes and expectations

about who Indians were and what their government should do for them. They bearded the woolly predictions of experts who said that French-style secularism, the compulsory retreat of religious myths into the private sphere, was necessary before hard-nosed democracy could take hold of the world. The Indian polity was home to hundreds of languages. It contained every major faith known to humanity. Social complexity on this scale led Indian democrats to a brand-new practical justification of democracy. Democracy—say champions of the India Story—was no longer regarded as a means of protecting a homogeneous society of equals. It came to be seen as the fairest way of enabling people of different backgrounds and divergent identities to live together as equals, without civil war.3

The Greatest Show on Earth

The India Story has had a great run. Despite many disquieting twists and turns in the country’s nearly three-quarters of a century as an independent republic, the broad story has mostly endured. The world sees India as a democracy and the majority of Indians say they’re attached to ‘democracy’ (63 per cent) and satisfied with its achievements (55 per cent).4 There are at least three overlapping explanations for the long life of the India Story.

The first reason is the usual focus on India’s achievements in the field of government since independence—the performance of its state institutions, political reforms, and elections. The new republic of India is seen to have managed to resolve its boundary challenges and to establish itself as a sovereign territorial state with an impressive written constitution. The Indian state crafted a durable peace with its humbled British masters by choosing to remain within the British Commonwealth. The French and Portuguese enclaves on Indian soil were annexed. The new Indian republic survived the turmoil and hell of the Partition of 1947, when perhaps as many as 16 million people were forced to cross borders and a million or more suffered

murderous pogroms. A new written constitution was adopted (on 26 November 1949). Its principal hand was the political leader of the lowly ‘untouchable’ caste and law minister, B.R. Ambedkar. ‘We, The People of India’, began a document soon to be renowned for its length and sweeping breadth, and for its redefinition of democracy to include the rule of law as a weapon to be used against abuses of power in the hallowed name of ‘the people’. Its soberly written preamble described India as a ‘sovereign democratic republic’. It stood for social, economic, and political justice for all its citizens; liberty of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship; equality of status and of opportunity; and fraternity that would assure the dignity of ‘the individual and the unity and integrity of the Nation’.

It was within this visionary constitutional framework that the new republic hosted its first parliamentary general election, which began in October 1951 and took six months to conduct. It was the grandest show the world had ever seen.The aim: to create a countrywide electoral system that extended a fair vote for 4,500 seats to 176 million Indians aged 21 or over, 85 per cent of whom couldn’t read or write. The methods: in quick time, 224,000 polling booths were built; 2 million steel ballot boxes were manufactured and delivered to site; 16,500 clerks were hired on six-month contracts to type and collate the electoral rolls; 56,000 presiding officers and 280,000 support staff supervised the voting; and 224,000 police officers were assigned to polling stations. At each polling station, to assist voters who were mainly illiterate, multiple ballot boxes were installed, each one with a separate political party symbol: an elephant for one party, an earthen lamp for another, a pair of bullocks for the Congress party. Helped by Indian scientists, the newly established Election Commission actioned plans for preventing fraudulent voting by finger printing each voter; the indelible ink, of which nearly 400,000 phials were used, lasted at least a week. Voter turnout was 60 per cent. It was an election in which 75 political parties wooed the votes of 176 million adult women and men. A total of 489 seats in the federal Parliament and 3,375 seats in the state Assemblies were filled. Nehru’s Congress party claimed

victory in eighteen of the twenty-five states and won an outright majority of seats (364 of the 489) in the directly elected lower house called the Lok Sabha, or the House of the People (the upper house, called the Rajya Sabha, or Council of States, comprises members elected by state legislatures and a few nominated by the president). The socialists were routed. The communists claimed second place, which was an impressive result for a newborn democracy that probably included more hardcore believers in Stalin than the Soviet Union. In the interests of a fair and equal franchise, there were even efforts by the Election Commission to dismantle patriarchal barriers to women’s participation in the election. The diffidence of many women to allow their names to be entered on the electoral register—preferring instead to be X’s wife or Y’s mother—was publicly criticized and officials were instructed to record the actual name of such women voters. They sometimes refused. An estimated 2.8 million female voters were turned away, yet the public uproar that followed was the beginning of an unfinished democratic revolution against male prejudice.

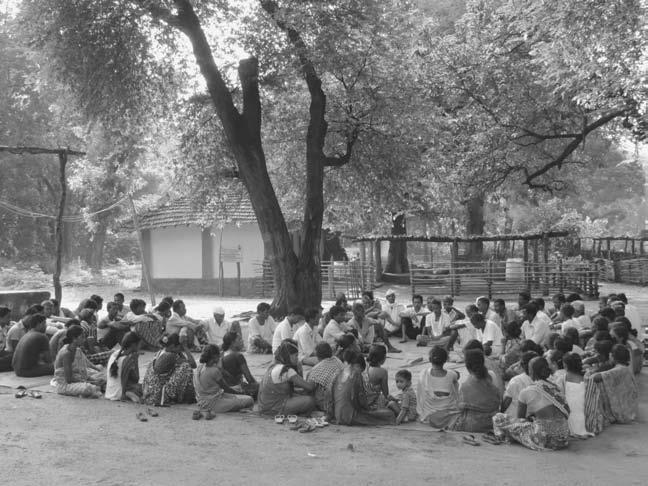

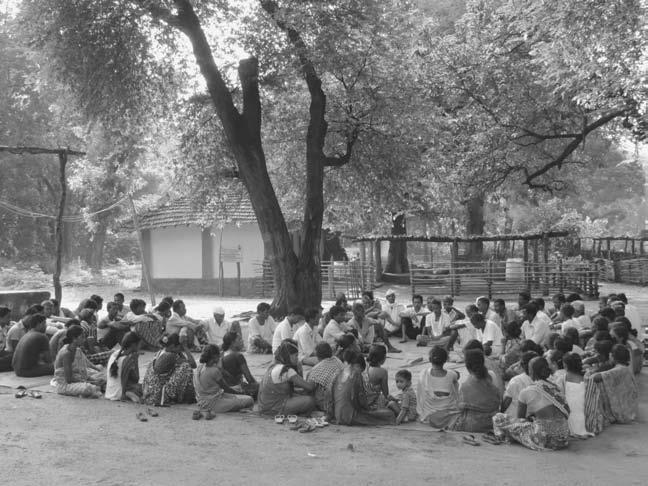

The political institution-building that took place after independence was substantial, but the chroniclers of the India Story go further, by emphasizing how, during later decades, India’s gravity-defying adventure with democratic politics was strengthened by institutional repairs and experiments with new governing procedures. They give the example of the Parliament’s breathtaking decision (in 1993) to extend democracy ‘downwards’ and ‘sideways’ by extending local selfgovernment (panchayat) to all of India’s 600,000 villages (Figure 2). The three-tiered reform created some 227,000 ‘village councils’ at the base; 5,900 higher-level or ‘block councils’ comprising representatives drawn from the village councils; and standing above these over 470 ‘district councils’. Similar structures (municipal corporations and councils) were erected in the cities, so that overall, the ranks of the country’s elected representatives—some 500 members of Parliament (MPs) and 5,000 state representatives—were swelled by another 3 million newly elected local representatives. There were design flaws, and this momentous move towards greater democratization was not welcomed by all.

States unevenly implemented the new structures, and fiscal decentralization failed to keep pace with political decentralization. Local governments were unable to legislate or take either the states or the central government to court over jurisdictional disputes. Dirty tricks were played on the weak by the strong.Village assemblies often didn’t take place, or they were inquorate, or their records were falsified by village oligarchs. Women candidates and voters suffered harassment. Elected local government leaders (called sarpanches) from the lower castes were physically prevented from assuming office. Even though there was talk of excluding political parties from this new domain of self-government, foul party-political games were played. And, when all else failed, the dominant castes used violence to have their way. And yet, in the India Story, despite all this, the panchayat reforms produced benefits. Not only was panchayat voter turnout generally higher (on average 60 per cent) than for state and national elections. The local government reforms helped democratize Indian

Figure 2. A village council meeting in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra

democracy. New political spaces were created for the downtrodden, especially women (one-third of seats was set aside for them). Groups such as Dalits (the lowest in the Hindu caste structure, officially classified as Scheduled Castes, or SCs) and tribal people known as Adivasis (literally, ‘original inhabitants’, officially classified as Scheduled Tribes, or STs) were also guaranteed seats in proportion to their actual numbers.

Equally gravity-defying was the creation of a new model of secularism—not the secularism of the French or American constitutions, but in effect a new vision of guaranteeing the political equality of all Indian religions, which implied the need for government policies to fight religious fanaticism and to correct the imbalances of power within and among different religions. India’s secular democracy, say its defenders, came to resemble a modern palimpsest bearing traces of many ancient faiths and ways of life, a legally protected canvas of many different colours, not a patchwork quilt of loosely connected or cantankerous faiths kept from each other’s throats ultimately by the gun barrels of the state.

The India Story tells how the legal requirement to reserve spaces in the national and state legislatures, and in public sector employment and educational institutions, first for SCs and STs and then for the middle castes, clumped together as ‘Other Backward Castes’ (or, OBCs), had democratizing consequences, especially in the field of elections. The reforms stimulated a new kind of democratic class struggle driven by lower-caste assertion of regional caste-based political parties headed by iridescent leaders. Among them was Mayawati, the first woman to become chief minister of the most populous state of Uttar Pradesh, a leader who delivered thumping speeches about the importance of creating an ‘egalitarian society’ freed from discrimination based on caste or creed; and the former chief minister and political boss of Bihar, Lalu Prasad Yadav, who portrayed himself as the ‘messiah’ of the backward castes, Muslims and Dalits. Bearing names like the RJD (Rashtriya Janata Dal), the SP (Samajwadi Party), and the largest Dalit-based party, the BSP (Bahujan Samaj Party), these parties

intensified political competition, both in the states and at the federal level in Delhi. A record thirty-one different parties, many of them defending a one-point programme and most of them elected from the regions, filled the Parliament following the 1996 general elections. Despite repeated splits, these splinter parties pushed the young Asian democracy to the point where, from the mid-1990s, no government in Delhi was formed without their help.

The India Story stresses that the political empowerment of the powerless was perhaps Indian democracy’s greatest achievement. Unlike any other democracy on the face of our planet, the Indian poor—despite multiple obstacles and in the absence of compulsory voting—turn out at election time in proportionately greater numbers than the affluent middle and upper classes.5 In the United States, the motivation to vote is lowest among the poorest (in the 2008 elections, when overall voter turnout was 57.1 per cent, it was 41.3 per cent; among the wealthiest it was 78.1 per cent). In India, the pattern is just the opposite. In the first two general elections in India, overall voter turnout was under 50 per cent. In the 1977 elections, the figure reached around 60 per cent, where it has consistently remained, the increase due largely to the growing political involvement of the poor, women, and young people. In the 2019 national election that returned Narendra Modi to power with a thumping majority, the turnout reached a record 67 per cent. The trend, says the India Story, is living proof that a big majority of India’s citizens have grown convinced that the ballot box is a means of earthly redemption—that elections are uniquely democratic moments when citizens display their dignity as equals and express their differences as members of particular communities.

The India Story undoubtedly captures the important ways in which the country has experimented with democratic self-government. The long and interesting list of achievements doesn’t just include a robust written constitution, a three-tier system of government driven by stronger local self-government and a quasi-federal division of powers between states and central government, and the introduction of compulsory quotas for marginalized groups. Fiercely fought student

elections, popular protests, and creative instruments such as public interest litigation that enable public-spirited individuals or courts to take up the cause of victims of arbitrary power, have also provided traction to the India Story. According to one Indian political scientist, ‘the new political community of democracy is being forged and in the process there is a democracy of communities emerging.’ Describing India as a democracy engaged in the process of democratizing itself, the interpretation quietly supposes that history is on its side, and that Indian democracy, for the sake of overcoming imperfections, now needs further reforms.

After seven decades the Indian democratic system has, by and large, acquired . . . the legitimacy that it requires for its smooth and proper functioning Because it has done so, and stabilised, we have the luxury to analytically move to the next historical stage of intellectual inquiry of identifying its blemishes and expressing our discontent with its limitations.6

Along similarly sanguine lines, another leading Indian scholar notes that democracy is ‘a raw, exciting, necessary and in the end ultimately disappointing form of politics.’ It ‘encourages people to refuse to be ruled by those who deny them recognition’. He goes on to observe that while in India ‘the idea of democracy has released prodigious energies of creation and destruction’, its promise is widely believed and now serves as a material force shaping the lives of many millions of citizens. ‘Democracy . . . has irreversibly entered the Indian political imagination’, he concludes. ‘A return to the old order of castes, or of rule by empire, is inconceivable: the principle of authority in society has been transformed.’7

Darling of the West

Apart from gradual democratization and a robust history of elections and institutional innovation, there’s a second and rather unexpected reason for the credibility of the India Story, to do with outside

reinforcement. It may sound odd to put things this way, but in a curious twist of fate, an upside-down species of Orientalist prejudice has nourished the India Story. In recent decades, especially among American speechwriters and politicians and their political allies, outsiders have come to speak effusively of India as an important global partner whose commitment to commonly shared values such as ‘liberal democracy’ augur well for a close relationship in matters of trade and technology, diplomacy, and military strategy.

The diplomatic love affair of Western powers with democratic India is comparatively recent. Things weren’t always so rosy, especially during the early decades after Indian independence, when Nehru personally dominated the making and unmaking of Indian foreign policy. Democracy stopped at India’s borders; Nehru’s foreign policies were India’s. The results were distinctive. Whole continents (Africa and Latin America) and policy areas like trade and commerce were virtually ignored. Nehru had little affection for the time-tested rule that democracies always fare better when they band together, under a tent of multilateral, publicly accountable, cross-border institutions. His suspicion that the United States was plotting to become the region’s next imperial power, combined with his general disdain for global Big Power Politics, led him to forge an alliance with Tito’s neo-Stalinist Yugoslavia, and did so in the name of the doctrine for which he achieved global fame: ‘non-alignment’. Nehru liked to defend it by referring to the Five Principles ( Panch Sheel ) of world order, which included non- aggression; peaceful coexistence; respect for the principle of the sovereignty of states; non-interference in their domestic affairs; and equality among the world’s states and peoples. The mix contained incompatibles; and democratic virtues like respect for equal civil and political freedoms inside states went missing, which helped Nehru turn a blind eye to the violation of the same principles, for instance in his long-standing support for the Soviet Union and its imperialist, anti-democratic command over the ‘captive nations’ of central- eastern Europe. After the death of Stalin in 1953, relations grew especially warm with the

Soviet Union, which provided capital and technical assistance for India’s state-led industrialization.

The blinkered foreign policy produced mixed results. Indian energy was put into cultivating relations with the totalitarian People’s Republic of China (though the disastrous 1962 war with China and the failure to resolve bellicose tensions over the Tibet border dogged Nehru until his death in office). Nationalist statesmen like Gamal Abdel Nasser praised Nehru as the voice of human conscience. Yet there were smouldering tensions with the United States, captured by the perhaps apocryphal but telling anecdote that has Secretary of State John Foster Dulles demanding to know whether India was for or against the United States, to which Nehru replied: ‘Yes.’

The anti-American tone set by Nehru’s foreign policy hardened in post-Nehru India. When in the early 1970s Pakistan was plunged into civil war and a war with India that ended with the creation of Bangladesh, the United States sided with Pakistan, its partner in the rapprochement with China. In that same period, India scrapped its non-alignment policy by signing a twenty-year Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union. ‘By 1971’, Henry Kissinger later wrote,‘our relations with India had achieved a state of exasperatedly strained cordiality, like a couple that can neither separate nor get along.’8 Tensions with the United States festered after India exploded its first nuclear device (in May 1974), in an operation code-named Smiling Buddha. It was not only the first country to do so outside the United Nations Security Council. India also blocked calls by the United States to allow outside inspection of its nuclear facilities.

The turning point in India’s relation to the West, and to the United States in particular, came after the collapse of the Soviet Empire in 1989–91. India was plunged into confusion about how the country might behave in a unipolar world dominated by the United States. Further disagreement between the two states about nuclear weapons erupted; a period of stand-off followed the 1998 nuclear test by India and the decision of the Clinton administration (in May 1998) to recall its ambassador and impose economic sanctions on India. Yet despite

this friction, the United States, looking for allies against China, began to regard India as a geopolitical prize. Rich in resources, blessed with a giant domestic market, strategically well positioned, prone to antagonism with China, and blessed with the title of the world’s largest democracy, India came to be regarded as a potential major partner in consolidating US power in the region and beyond as part of a coalition to contain the next rising global power, China. According to this geopolitical reasoning, the goal of American foreign policy was to consolidate a partnership between two polities that would in the end come to resemble each other, and to see eye to eye on most major foreign policy matters.

And so, an American charm offensive was launched. It began with President Clinton’s visit to India (March 2000). It yielded a jointly signed vision statement that set out a charter for future political engagement between the two countries, backed by an agreed programme of ‘institutional dialogue’ about bilateral deals. Despite anti-imperialist rumblings at home about dealing with the Americans, India’s diplomats negotiated a full lifting of sanctions. US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and her officials presented to Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh (March 2005) an outline of a ‘decisively broader strategic relationship’ laced with talk of helping India ‘become a major world power in the 21st century’. Agreements covering cooperation in maritime security, humanitarian assistance, disaster relief, and counterterrorism, the lifting of a three-decade moratorium on nuclear trade with India and naval exercises prepared the way for a visit (March 2006) by President George W. Bush. ‘I’m honoured to bring the good wishes and the respect of the world’s oldest democracy to the world’s largest democracy’, he said, to warm applause. ‘The partnership between the United States and India has deep and sturdy roots in the values we share. In both our countries, democracy is more than a form of government, it is the central promise of our national character.’

During the next two decades, American leaders repeated the melody. The serenading of India as a democratic partner hit a new high as

the Obama administration announced a ‘pivot’ to Asia. ‘India and the United States are not just natural partners. I believe America can be India’s best partner’, said President Obama during his second visit to India (2015), drawing applause from his invited Delhi audience. ‘The world will be a safer and a more just place when our two democracies— the world’s largest democracy and the world’s oldest democracy— stand together.’ Spiced rhetoric of this kind flavoured the ‘Namaste Trump’ mass rally in February 2020, in the world’s largest cricket stadium (since renamed Narendra Modi Stadium) in Ahmedabad. ‘America loves India. America respects India’, said the American president. ‘And America will always be faithful and loyal friends to the Indian people.’ Never mind that more than one-third of the estimated 125,000 people who had turned out to see him left before the end of his nearly thirty-minute speech, or that another third had turned their backs by the time Mr Modi spoke after the American president. The important thing was that in Ahmedabad and several cities, giant billboards trumpeted the old trope of the ‘world’s oldest democracy’ meeting the ‘world’s largest democracy’ (Figure 3). Modi’s efforts to

Figure 3. The world’s ‘oldest democracy’ and ‘largest democracy’

use his stadium hosting of Trump to turn geopolitics into a heavily advertised spectator sport broke with his predecessors’ careful attempts to strike a balance between the United States and China. Under Modi, India has hedged against neighbouring China by openly courting the distant US. India has signed a joint strategic vision statement for the Asia- Pacific and the Indian Ocean region, a Defence Framework Agreement, and a landmark defence logistics pact with the United States, giving each side access to the other’s military facilities. Together with Japan, the United States and Australia, India is party to the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, the ‘Quad’ initiative designed to promote multilateral dialogue and an ‘Asian arc of democracy’. Defence, intelligence, and trade ties with the United States have reached new highs in recent years. There’s also been much eulogizing by Modi about the need for India, the ‘world’s largest democracy’, to ‘overcome the hesitations of history’ by forging tighter links with its ‘liberal democratic’ American partner.

Emergency Rule

Apart from the Western validation of Indian democracy and India’s own institutional evolution, there’s a third—less obvious—reason why the India Story has enjoyed a long life. It is, ironically, an egregious attempt to destroy India’s democracy that reinforced faith in its democracy. This happened under the watch of Indira Gandhi, during a stormy period now known as the Emergency. The tempest was unleashed by the lacklustre showing of Mrs Gandhi’s Congress party in the 1967 general elections, which it managed to win, but with a reduced majority and loss of control over eight state legislatures. Indira Gandhi responded by resorting to the old populist tactic of appealing over the heads of her party apparatus, directly to voters, especially to its millions of poor. The aim was to strengthen her hand and build a new-style Congress government by disrupting the so-called ‘vote banks’ system, through which local party

barons (known as the Syndicate) organized whole groups of voters through patronage networks, in return for which they received perks and privileges from the central Congress leadership. Through posters, loudhailers, and television and radio sets, the slogan ‘Abolish Poverty’ (Garibi Hatao) was plastered everywhere. Constitutional protection for the privileges of the regional royalties was abolished; banks were nationalized; and Prime Minister Gandhi surprised millions by calling a general election one year early.

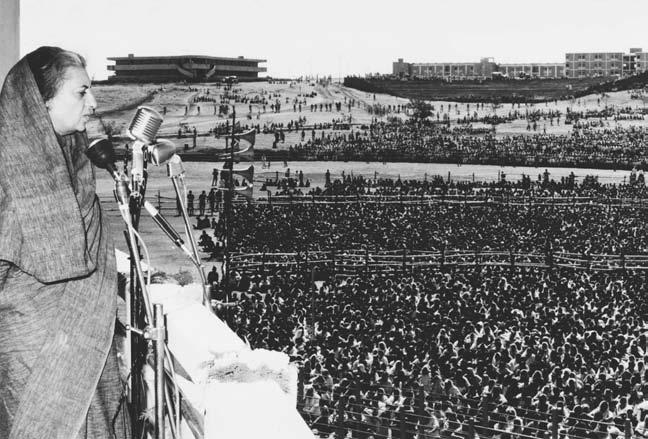

In that general election (1971), Mrs Gandhi’s move to nationalize Indian politics by distracting attention from regional and local concerns was richly rewarded—with a handsome landslide victory. Then military conflict with Pakistan erupted. Mrs Gandhi’s swift, iron-fisted approach resulted in both victory and the secession of Bangladesh and (in the 1972 regional elections) another round of political success.The way was now open to shrink democracy into elections and rebuild Congress into an election-winning machine that resembled a large, lumbering elephant with Mrs Gandhi in the saddle, garlanded with flowers, under a parasol, looking down imperially on intrigued and admiring crowds (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Indira Gandhi addressing a public rally in Maharashtra (1972)