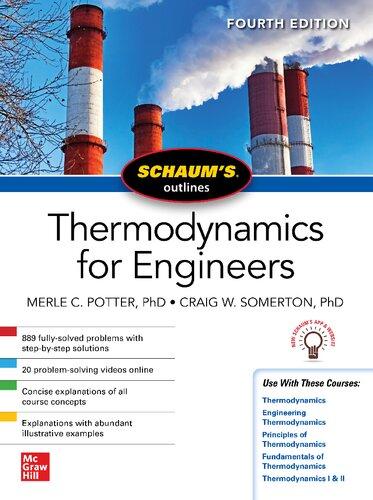

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

John Cage and Avant- Garde Film

Richard H. Brown

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Brown, Richard H., 1982– author.

Title: Through the looking glass : John Cage and avant-garde film / Richard H. Brown.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, 2019. |

Series: The Oxford music/media series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018015150 (print) | LCCN 2018021953 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190628093 (updf) | ISBN 9780190628109 (epub) | ISBN 9780190628116 (Oxford Scholarship Online) | ISBN 9780190628079 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190628086 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Cage, John— Criticism and interpretation. | Music—20th century—History and criticism. | Experimental films—History and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML410.C24 (ebook) | LCC ML410.C24 B76 2018 (print) | DDC 780.92—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018015150

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback printed by WebCom, Inc., Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

This volume is published with the generous support of the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

What is a course of history or philosophy, or poetry, no matter how well selected, or the best society, or the most admirable routine of life, compared with the discipline of looking always at what is to be seen? Will you be a reader, a student merely, or a seer? Read your fate, see what is before you, and walk on into futurity.

Henry Davi D THoreau, “Sounds,” from Walden; or, Life in the Woods, 1854

1. The Spirit Inside Each Object: Oskar Fischinger, Sound Phonography, and the “Inner Eye”

2. “Dreams That Money Can Buy”: Trance, Myth, and Expression, 1941–1948

3. Losing the Ground: Chance, Transparency, and Cinematic Space, 1948–1958

4. “Cinema Delimina”: Post- Cagean Aesthetics, Medium Specificity, and Expanded Cinema

Conclusion: “Through the Looking Glass”: Poetics and Chance in John Cage’s One11

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

That is finished now. It was a pleasure. And now this is a pleasure.

This study would not have come about were it not for the generous support and encouragement from scholars, artists, and family. First and foremost, I would like to thank Joanna Demers for running with the topic from day one and pushing me along at every step of the way with brilliant editorial critiques and kind words of encouragement; David James, for sparking my interest in experimental film, thus fueling the trajectory of this topic; and Bryan Simms, for his guidance in the process of writing and researching about 20th-century music. In addition, I owe a great debt to Robert Moore’s keen analytic insight and for his unwavering advocacy for all things Zen, as well as George Wilson for his guidance with the history of film philosophy, and finally Brian Head for taking time out from our many private guitar lessons over the years to discuss the esoteric world of John Cage, cathode-ray tubes, and anything else that hid the obvious fact that I had spent the week researching and not rehearsing.

This study would not have taken its current shape without the guidance of many archivists, most notably the encouragement and zeal of Laura Kuhn at the John Cage Trust, Cindy Keefer and Barbara Fischinger at the Center for Visual Music, and Augusto Morselli at the Richard Lippold Foundation. Many other archivists have aided this research along the way, including Nancy Perloff at the Getty Research Institute, Jonathan Hiam and Bob Kosovsky at the New York Public Library, Music Division, D. J. Hoek and Jennifer Ward at Northwestern University Music Library, Jennifer Hadley at the Wesleyan University Special Collections Library, David Vaughan at the Merce Cunningham Dance Company Archives, Robert Haller and Andrew Lampert at Anthology Film Archives, Marisa Bourgoin at the Archives of American Art, Bill O’Hanlon at the Stanford University Special Collections, Charles Silver at the Museum of Modern Art Film Study Center, and Tom Norris at the Norton Simon Museum.

In addition, this research has benefited from the many detailed comments and critiques of scholars within the world of Cage Studies, and I would like to extend a special note of thanks to all who were willing to guide my thoughts through the process of writing and revising: Gordon Mumma, Kenneth Silverman, James Pritchett, David Bernstein, David Nicholls, David Patterson, Christopher

• Acknowledgments

Shultis, Leta Miller, Suzanne Robinson, John Holzapfel, Mark Swed, Mina Yang, Benjamin Piekut, Olivia Mattis, Joseph Hyde, Josh Kun, Brian Kane, Tim Page, Douglas Kahn, Paul Cox, James Tobias, Emile Wennekes, Tobias Plebuch, and Margaret Leng Tan.

As John Cage once said, “an error is simply a failure to adjust immediately from a preconception to an actuality,” and thus, all errors that remain in this study, whether a potentiality or an actuality, are wholly my own. To my many roommates and friends in the Los Angeles entertainment industry that puzzled over my strange, foreign, and oftentimes hermetic academic life, while still generously providing some firsthand observations on the realities of filmmaking that a scholar could never anticipate; to my cousins Maria Dyer and Christine Troshynski for providing free couch space in Chicago and New York for my many extended archival visits, and finally, a special note of gratitude to my sister Vanessa, who ran alongside me in our race to the finish line for our doctorates (she won by a year . . .), and to my mother, Bonnie.

INTRODUCTION

a u D iovisu(ali T y)(ology)

It’s not a physical landscape. It’s a term reserved for the new technologies. It’s a landscape in the future. It’s as though you used technology to take you off the ground and go like Alice through the looking glass.

Jo H n Cage, 1989

Cage has laid down the greatest aesthetic net of this century. Only those who honestly encounter it and manage to survive it will be the artists of our contemporary present.

sT an Brak H age, 1962

On one quiet evening in 1960, viewers who tuned in to the popular game show “I’ve Got a Secret” laughed at music in a new way. The premise of the show was simple: A blind celebrity panel aimed to guess the contestant’s quirky secret through a cross-examination that typically culminated in a calculated imbroglio. The February 22 show began with Zsa Zsa Gabor, who revealed that she was donning a dress made out of a potato sack, followed by John Cage, whose secret was to perform a composition consisting of an electric mixer, mechanical fish, five radios, tape recorder, and various other soundproducing devices. Eclectic musical performances on the show were not uncommon, such as a rendition of orchestral literature on soda pop bottles by members of the New Orleans Philharmonic, or duet for violin and chimpanzee by Canadian singer Gisèle MacKenzie. The host, Gary Moore, endeavored to legitimize Cage’s performance as “serious music” by quoting several major newspaper reviews, and eventually abandoned the panel to allow time for the performance of Water Walk (1959), which, as Cage explained with a deadpan stare, earned its title, “because it contains water, and I walk during its performance.” Moore ended the introduction with a caveat: “He takes it seriously, I think it’s interesting; if you are amused you may laugh, if you like it you may buy the recording.”

Water Walk featured a typically atypical Cage, layered between levels of mediation (although the radios remained silent because of a union dispute) and beaming with optimism under the veil of his

famous sunny disposition. After his introduction he noted to Moore that he would “prefer laughter over tears” in response to his variation of a typical performance. Within contemporary music circles today, Water Walk holds a place of reverence that rarely provokes laughter or tears, and it recently found a new life on the Internet. As of this writing, it’s the most-viewed John Cage video on the popular user-generated content website, YouTube. The clip exists within its own phantasmagoric shadow, reflecting a tumultuous time in American history, when in the same year John F. Kennedy outperformed his perspiring opponent Richard Nixon in the first televised presidential debate, and when Cage finalized perhaps the most influential publication by a composer in the 20th century, Silence. Each time I revisit the clip, I’m struck by the medium itself: the flickering frame and muted grays give it an artifice that simultaneously reaffirms its concrete identity as historical evidence while gleaming with an artificiality as haunting as a television left to sputter forth late into the night long after its viewer has fallen asleep (Figure I.1).

Broadcasting from CBS Studio 59 on West 47th Street in New York City, Cage’s “I’ve Got a Secret” performance occurred at a time when media boundaries became subject to the same ontological scrutiny as traditional forms of artistic expression, reflecting a tension within late capitalist consumption habits best echoed in Raymond Williams’s classic study on mediation and identity, Television: Technology and Cultural Form (1974). Avant-garde filmmakers and the industry surrounding their endeavors were adept at articulating seismic shifts in the media landscape, chiefly those working within the fringes of a new media economy. Just down the street from Studio 59 in lower Manhattan, Lithuanian artist Jonas Mekas was setting the foundation for the Film-Makers’ Cooperative while simultaneously editing the influential avant-garde film journal, Film Culture. Meanwhile, impresario Amos Vogel’s Cinema 16 series was at its height, showcasing avant-garde and experimental films to a captive audience of curious young New Yorkers. These minor cinemas were more than just an opposition to the hegemony of industrial forms of narrative cinema. Their ethical stance of what David James describes as “becoming-minoritan” reflected a living, organic network that spread throughout the variegated artistic enclaves of major American cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, channeling out to the “I-80 avant-garde” of midwestern town-and-gown outposts such as Ann Arbor, Michigan.

By 1960, the 48-year-old John Cage was primed to stand as a type of metaphor for this transition period, and his “I’ve Got a Secret” appearance inaugurated his near-mythological position as a sort of father figure to the movement. Beaming forth on the television screen, Cage presented a host of ideological contradictions that inspired reverence, opposition, and, above all, an outpouring of theory and discourse on the ontology of the musical artwork in an interconnected audiovisual

environment.1 Like the cathode ray beaming through shimmering glass, avantgarde cinema challenged artists to climb the mantel and peer into the mirror reflectivity of this new media landscape of the future, and Cage’s “aesthetic net” caught many well-known filmmakers. Pointing to that nexus, this book begins with a simple goal: to survey John Cage’s interactions and collaborations with avant-garde and experimental filmmakers, and in turn seek out the implications of the audiovisual experience for the overall aesthetic surrounding Cage’s career. I choose key moments in Cage’s career during which cinema either informed or transformed his position on the nature of sound, music, expression, and the ontology of the musical artwork. This is not an exhaustive history of Cage’s influence

Figure I.1 John Cage performs Water Walk (1959) on “I’ve Got A Secret,” February 23, 1960.

on filmmakers’ approaches to filmmaking, nor is it a complete history of Cage’s work with filmmakers. The examples I highlight coincide with moments of rupture within Cage’s own consideration of the musical artwork, and I argue that these instances have a significant and heretofore unacknowledged role in Cage’s notion of the audiovisual experience and the medium-specific ontology of a work of art. In turn, I argue for a reframing of Cage’s artistic program around media and perception.

The emerging field of audiovisual studies informs many aspects of this survey. Recent research has attempted to map this terrain of inquiry, and this study clarifies Cage’s role in establishing just what it means to speak of audiovisual aesthetics.2 One distinction I consider important for the purposes here is that between an audiovisual event, in which both sound and image are paramount to the experience of an artwork, and audiovisuality, in which a concept or artwork elucidates or expands upon the phenomenological present, thus opening up one’s eyes to the very notion of existence. Defenders of Cage’s artistic program contend his goal was simply that: to create a situation that, as Richard Fleming describes, “stirs what surrounds us, is already before us, that in the midst of which we find ourselves.”3 I wholeheartedly agree. I can recall many times when I left a concert of Cage’s music and felt such an awareness, and if anything, this study supports the foundation of Cage’s paradoxical intention of nonintention. Coming to terms with such a situation is one of the most rewarding aspects of exploring Cage’s music, life and art, and a more enlightened soul would be content at leaving it at that. However, having climbed the mantel, I find myself subject to the same incorrigible fate as Cage, and thus I will now proceed, as Cage once explained to his mentor Arnold Schoenberg, to beat my head against the wall and, in the process, poke my finger through the mirror.

To this I turn to audiovisuology. Combining qualitative, historical, systematic, and theoretical approaches, audiovisuology pivots from metaphorical uses of language to describe music toward the aesthetic experience of both listening and seeing. This shift from the notion of music in absolute terms is more in line with audiovisuality and the foundations of intermedia aesthetics, in which no single medium is held above another.4 I find this methodology helpful for approaching a topic that combines elements of historical musicological approaches to style analysis, avant-garde film studies in identity politics, medium, and defamiliarization, contemporary art theory on ontology and objecthood, and traditional film music scholarship on the relationship among sound, music, and image. Methodological tussles between competing ideological and departmental boundaries reflect the dramatic pressure placed on humanities academics to provide conceptual bridges between their work in the service of a 21st-century-contingent labor market. Yet this new academic economy is more diverse and interconnected than anything beyond, or perhaps perfectly in line with, Cage’s most prescient dreams, and it is

to this challenge that I consider Cage Studies paramount, as any line of inquiry into his career is inherently interdisciplinary.

I am not concerned with the arguments for or against Cage’s destabilization of a culturally specific form of musical discourse; I focus rather on the implications of the audiovisual experience and its concomitant role in 20th- and 21st-century modes of listening. Following the narrative of audiovisuology studies, I argue that the cinematographic experience, from its earliest incarnations in sound film and visual music animation to interactive media in the 1960s, gradually engendered a greater framework for understanding sound and listening than the relationship between notation and the sonic event. I use the term “cinematographic” here in the greater sense: the entire audiovisual filmic experience as well as the theoretical and philosophical investigation into the nature of the cinematic experience as it relates to reality and philosophy. Avant-garde, experimental, and expanded cinema practices provide both a theoretical and a practical framework for outlining such an audiovisual aesthetics. Writing the history of this movement in the United States was and continues to be a form of political ideology, where the minor–majority ethical stance of classic histories such as P. Adams Sitney’s Visionary Film, David James’s Allegories of Cinema, and more recent volumes such as Paul Arthur’s A Line of Sight, literally and figuratively beam forth with a poetic optimism. Classic volumes by A. L. Rees and numerous source reading documents from journals such as Film Culture established a historical narrative of American avant-garde film. Such narratives typically begin with trance filmmakers such as Maya Deren and Stan Brakhage, followed by Underground, Structural, and Expanded cinema practices in the 1960s, and this book adheres to accepted boundaries in its scope, noting moments during which Cage’s evolving positions coincided with practitioners and participants in new media culture.5

To place Cage at the center of this transformation in audiovisual culture would steer this study toward a familiar hagiography that has long beleaguered Cage Studies. Cage Studies, whether with a capital “S” or in quotes, in many ways mirrors the reception history of Cage’s life and music. The first wave, beginning with James Pritchett’s The Music of John Cage (1993), inaugurated an intellectual trend that sought to legitimize Cage’s music through traditional musicological methodology. Pritchett’s effort at proving that Cage was first and foremost a composer by presenting a style history through musical analysis remained a calling card for those hoping to cement his place within the discourse and history books of 20th-century Western European Art Music. And yet, such positivistic approaches were already waning in the face of critical musicology, which sought to destabilize the patriarchal Eurocentric tone of the discipline, and the second wave of scholarship beginning in the early 2000s quickly expanded to critique Cage’s artistic platform. Most recently, theoretical discussions stemming from art history, primarily through the work of Branden Joseph, Julia Robinson,

and others, have situated Cage’s aesthetic within the postwar American NeoAvant- Garde of visual artists such as Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. Joseph’s work in particular argues that artists within Cage’s circle moved beyond the European strategies of shock and negation that distanced art from the shackles of capitalism, as famously articulated by Peter Bürger’s classic Theory of the Avant-Garde. The postwar Neo turn instead affirmed difference through a strategy of passivity that acknowledged the totalizing force of late capitalism, and Joseph connects Cage’s critique of representation according to philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s notion of immanence. Perhaps the most refreshing recent theoretical model within musicology is that of Benjamin Piekut, who adopts anthropologist Bruno Latour’s “Actor-Network-Theory” to characterize the competing and interconnected ideological discourses of 1960s experimentalism in New York. Many since have penned nuanced insight into many of the contradictory elements of Cage’s stances on race, politics, and identity, elements that I agree are in need of greater scrutiny if Cage Studies is to progress as a discipline.6 In the midst of these ideological tussles, I find myself somewhat of a centrist. I respect the advice and guidance that many of the first- generation Cage scholars gave to this project, and I strove to find a balance between historical documentation of Cage’s work with filmmakers and the myriad of theoretical angles available to explain it.

Cage’s uncanny ability to present circuitous ideological stances on listening and sound during his career sparked a range of interpretations that moved far beyond the scientific speculations he espoused in his writings. His calculated use of a variety of South Asian and Eastern heuristics to demonstrate his conception of listening further problematized any straightforward reading of his artistic program. Cage’s colorful and creative prose veiled rather traditional observations among expression and the musical object, musical time, and the scientific structure of soundwaves.7 To say that Cage even advocated a specific aesthetic in the traditional sense would be an overstatement. He at times advocated a radical bohemianism that sought to usurp the power structures of corporate and political economies of music and at others retreated into a transcendental metaphysics. However, his fundamental notion of sound empirically categorized according to scientific observations regarding soundwave structure, duration, and audition remained consistent throughout his career. Relying on such a strict epistemology allowed Cage to withdraw any links between subjectivity and experience, despite the fact that his many observations on the relationship between audition and recording point directly to such a link. This is often read as a pacifism reflective of the homosexual subculture of artists and intellectuals living through the McCarthy era in the United States, as many have posited following the lead of Moira Roth’s classic essay, “The Aesthetics of Indifference,” or alternately as a retreat into the purely metaphysical relationship between idea and object.8

Following the work of David Paul on the reception history of Charles Ives, I situate Cage’s interaction and collaborations with filmmakers within a changing landscape of American intellectual history, expanding beyond Cold War politics to include West Coast Bohemianism, Modern Gnosticism, and the American Technological Sublime.9 These shifts coincide not only with those of Cage’s ideology, they mirror the philosophical investigations of form and medium in cinema as a type of political critique. Cage’s compositions often contained critiques of technological change in the 20th century, and his empirical categorization of sound came about through a number of interactions with scientists and engineers, the most notable being his father, John Cage Sr. Unbeknownst to many, Cage Sr.’s research focused on infrared-vision and sonar technologies, cathode-ray tubes for television, and, later in life, particle propulsion systems for interstellar travel. Cage Jr. demonstrated a surprising understanding of the specific mathematics and scientific application of his father’s research, and I pay special attention to Cage’s Imaginary Landscape compositions as nodal points for each of his intellectual and compositional breakthroughs. These works coincide quite closely with key junctures in Cage’s ever-changing and eclectic blend of scientific and spiritual metaphors to describe his ontology of music and modes of listening.

Moving beyond Cage Studies, I turn to a wide variety of fields under the general banner of audiovisuology. The most helpful thread of discourse traces sound artist and theorist Michel Chion’s critique of the traditional separation of the soundtrack as a distinct entity within the experience of the sound film. Chion’s “audiovisual contract” remains a foundation for those studying sound in film, and his categorization of listening modes into casual, semantic, and reduced are useful starting points. For the third category, Chion builds on the notion of the acousmatic, a term coined by Cage colleague, sound engineer, and theorist Pierre Schaeffer, whereby one focuses on the primary attributes of sound devoid of their visual context or origin. This model of what Schaeffer titled “reduced listening” has many parallels to Cage’s own efforts at “letting sounds be sounds,” although Cage himself expressed reservations with Schaeffer’s specific formulation.10 However, the reduced-listening model does bring to light a key theoretical and cognitive element of audiovisuality that Cage often noted: Although we can choose to look away, divert, or even close our eyes, even in deafness we never truly close off our bodies to the vibratory sensations of sound. Cage’s experience in an anechoic chamber, where soundwaves are reduced to nearly inaudible levels, led not only to his signature phrase, “there is no such thing as silence,” it also upset the traditional hierarchy of media.11

Following Cage, sound art theorists argue that modern Western civilization gives primacy to the visible as the measure for the general ontology of experience, while relegating the audible to hearsay, a form of communication and evidence

prone to subjectivity and falsity. Scientific measurement relies on the concreteness of visual examples, and although theories of the mathematical ratios between musical overtones provide a general consideration of musical form and structure, their varied applications in tuning systems throughout history and the inherent subjectivity of individual methods of the structuring of the octave make this system an unreliable method of measurement or scientific proof. Cage’s effort at reversing this media hierarchy gave the term “music” primacy in his model of audiovisuality. Through his desire to legitimize his artistic platform within the narrative of Western tonality, from Monteverdi to Schoenberg, Cage held onto the term “music” too strongly; perhaps a better term would simply be “audition” or the experience of audition. In any case, Cage’s formulation provides a fitting starting point for exploring a methodology for audiovisual studies, moving toward the “ology” necessary for any research agenda wishing to elucidate meaningful conclusions beyond the traditional models of counterpoint and parallelism familiar to those studying narrative film music.

The standard theoretical discussions of sound in film argue that sound temporalizes the cinematic experience, grounding it in a reality in sync with the temporal audiovisual experience, and thus point to the necessity of sound in the cinematographic experience. Sound spatializes the two-dimensionality of cinema by projecting the emotive, narrative, and cinematographic content into space, providing a moment of empathy and identification with the artificial celluloid imagery on the screen. Sound projects vibrations into the cinematic space that reverberates within the cavity of the audience member, allowing for a nuanced and emotive connection to the distant and fantastical imagery in front of them. This points to the deficiencies of any single medium to fully generate a sense of reality independently and to the importance of considering the cinematographic experience as a whole when discussing general ontologies of cinema.12

Traditional media pairings sought to find ways in which sound and music augment or shape narrative or visual elements of the cinematographic experience, and as Cage expressed in his own writings, this media hierarchy was anathema to his model of audition as the primary attribute. This theoretical pressure point remains an arena of contention within audiovisuology, and I find Nicholas Cook’s rather cumbersome yet enlightening classic study, Analysing Musical Multimedia, a helpful starting point for establishing a methodology that upsets the familiar ways one characterizes simultaneously seeing and hearing an audiovisual event.

Cook’s laudable effort at challenging the model of visual primacy in analyzing multimedia is predicated on the notion that meaning is an emergent attribute that occurs within what he describes as synchronic “Instances of Multimedia” (IMM) brought about through the logic of metaphor. Within any such IMM, Cook applies two tests. The first asks whether any similarity is consistent or coherent, and consistence leads to a second category of various levels of

conformance: dyadic, when one medium corresponds directly to the other; unitary, when one medium predominates and the other conforms; and triadic, when, following Roland Barthes, the two mediums are linked indirectly through a “third meaning” with consistency.13 Cook argues that most IMMs fail the conformance test (an assertion that has broad implications for the notion of “visual music” discussed in Chapter 1) and his second test, that of difference, is the most helpful for my purposes. With this test one looks for either contrariety, in which the media pairing undergoes undifferentiated difference, or contradiction, in which the pairing is in competition or contest for meaning. Following the observations of James Buhler, however, it seems clear that Cook fell prey to a similar problem Cage encountered when drafting his early theoretical essays on the relationship between music and dance. Here Cage grappled with the assumption that music itself is only form, not content, and music is prone to enter into a meaningful relationship that gives primacy to the other, leaving it with the default status of a secondary attribute.14

This common empirical philosophical observation, that music is the “grin without the Cheshire cat,” points to a methodological tussle that musicologists have battled for nearly a century, namely the effort at establishing methods of legitimizing 19th-century notions of musical autonomy through style analysis and music theory. Ironically, as Buhler also notes, film studies fell prey to the same fate, but in reverse. Classic academic studies relied on psychoanalytical and semiotic models of structural interpretation and “close-reading” analyses of test case films to demonstrate highly specific theories of film. However, in the 1990s the so-called Wisconsin School adopted a neoformalist cognitive approach to demonstrate concrete visual relationships of continuity editing. Scholars such as David Bordwell and Noël Carroll have surprisingly turned to musical–theoretical models of harmony and counterpoint to give meaning to their close readings of editing and framing of the visual field. Around the same time, musicological scholarship was just beginning to turn away from its positivistic past, and Cook’s final assertion in Analysing Musical Multimedia, that one must “dispense with the ethics of autonomy, and with the Romantic conception of authorship which underwrites it,” reflects a radical approach to multimedia analysis. Such an approach is in no small way influenced by Cage’s disruptive ontology as it strives to, as Cook pleads, “analyse the way in which contest deconstructs media identities, fracturing the familiar hierarchies of music and the other arts into disjointed or associative chains.”15

Cage’s struggles with 19th- century notions of autonomy, musical form, and the general ontology of music emerged during a period of sweeping changes in media and technology, and the title of this book and opening quote of this Introduction provide a fitting metaphor for the underlying issue of media and perception in Cage’s various ontologies of music. To this I turn to one

last helpful theorization, the notion of the cinesonic and the materiality of sound. Borrowing from Philip Brophy’s poignant neologism, Andy Birtwistle argues for a return to the materiality of sound as a temporal event in which, following the tenets of an audiovisuology, a cinesonic approach to the audiovisual reaffirms the material. Invoking the foundational semiotic approaches to film studies, Birtwistle notes that Saussurian linguistics ignores concrete speech acts, or parole, in favor of synchronic, static states of language [ états de langue] that identify speech acts differentiated in negative terms from others. By relegating sounds to a secondary status, linguistics brackets what Birtwistle describes as the “concrete particularity” of sound. Drawing on Schaeffer’s acousmatic model of listening, he argues for an undifferentiated sense of perception that allows for a fluid and dynamic approach to audiovisual events.16 Although Birtwistle’s goals are geared toward discovering and negotiating relationships between sound and image, his conceptual critique reflects the influence of Cage’s own model of undifferentiated perception within audiovisual studies in particular and sound studies in general. This collision point between studying sonic events on their own versus their audiovisual context is precisely the terrain I tread throughout this study. One has to look at only a few recent volumes in sound studies by Seth Kim- Cohen, Frances Dyson, Salomé Vougelin, and Brandon LaBelle to note the centrality of Cage in the study of sound. Few, however, negotiate the nexus of the audiovisual, and few consider the differentiation I make between audiovisuality from a Cagean perspective, where the sonic event opens up a perceptual awareness, and the study of the audiovisual, which negotiates realms of fluid, emergent meaning within any multimedia event.17

Organization and Scope

This book is organized around two principles and their convergence: sound on film, sound in film, and intermedia. Each of these concepts corresponds to what I consider the three key conceptual shifts in Cage’s artistic platform. I begin with his move away from the tutelage of Arnold Schoenberg after a brief apprenticeship with German abstract animator Oskar Fischinger in the 1930s. This encounter led to his first explorations of the total sonic landscape in his early percussion pieces and was followed by his exploration of the poetics of dance, theories of mythopoetics, and interaction with Maya Deren and Hans Richter in the 1940s. Second, I turn to his move toward chance and indeterminacy in the early 1950s, which coincided with his concern for transparency in relationship to cinematic space. Last, I converge in the 1960s, when Cage moved toward a sound-system model of unencoded transduction of sound through electronics, dance, and film in his “Variations” series. In the interim I review a number of Cage’s theoretical

writings under the lens of media and perception, noting a largely unacknowledged thread of continuity in his writings that looks to the concrete particularity of sound, and its relationship to audiovisual events and, ultimately, to a model of audiovisuality that points to the undifferentiated act of perception itself.

I begin first with the question of sound on film, that is, the optical imprint of sound in the recording mechanism of the sound film in Chapter 1, which examines early theories of audiovisuology within the realm of visual music studies. The conceptual critique of visual music vastly expanded in the 2010s as composers and sound artists have explored the predecessors of digital signal processing and audiovisual software, looking back to the earliest technologies that unveiled the nature of sound through the diachronic representation of soundwave structure on the optical soundtrack. The history of visual music is a scattered and contested ground in this theoretical debate, and I begin by clarifying the historical and chronological details of one of the most cited interactions in the history of visual music studies between John Cage and German animator Oskar Fischinger in the 1930s and 1940s. In interviews Cage repeated a phrase he attributed to Fischinger describing the “spirit inside each object” as the breakthrough for his own move beyond tonally structured composition toward a “Music of the Future” that would encompass all sounds. Further examination of this connection reveals an important technological foundation to Cage’s call for the expansion of musical resources. Fischinger’s theories and experiments in film phonography (the manipulation of the optical portion of sound film to synthesize sounds) mirrored contemporaneous refinements in recording and synthesis technology of electronbeam tubes for film and television.

New documentation on Cage’s early career in Los Angeles, including research Cage conducted for his father John Cage Sr.’s patents, explains his interest in these technologies. Concurrent with his studies with Schoenberg, Cage fostered an impressive knowledge of the technological foundations of television and radio entertainment industries centered in Los Angeles. Adopting the term “organized sound” from Edgard Varèse, Cage compared many of his organizational principles for percussion music to film-editing techniques. As Cage proclaimed in his 1940 essay “The Future of Music: Credo,” advancements in technology not only allowed for an expansion of musical resources and compositional techniques, they also demanded that music itself be redefined. Film phonography and, later, magnetic tape provided the conceptual foundation for many of Cage’s aesthetic views, including the inclusion of all sounds, the necessity for temporal structuring, and the elimination of boundaries between the composer and the consumer. These two origin moments in the Cage narrative point to the primacy of the audiovisual in Cage’s ontology of the musical artwork, and cinema as a medium embodied this concept both through the physical observation of soundwave structure and through the audiovisual experience of temporally animated sound and image.

I spend time at the end of Chapter 1 addressing Cage’s original formulation of his “The Future of Music: Credo,” essay, noting that it likely was a historical afterthought assembled in 1960 for his publication of Silence. This assertion has many implications for our conceptual understanding of the term “organized sound” as well as the traditional Cage/Varèse dichotomy on the nature of the term espoused by the journal Organized Sound.

Temporality was paramount for Cage’s ontology of music, and duration remained central to Cage’s notion of musical form throughout his career. Chapter 2 examines the transformation of Cage’s temporal–mathematical compositional strategies in light of the audiovisual experience of the accompanied dance and its relationship to early theories of cinematographic reality in American avant-garde cinema. I note here a shift toward the European strategies of irony and difference in Cage’s rhetoric and compositions, particularly in the tone of his “Landscape” pieces from the period. I begin with Cage’s interaction with Hungarian polyartist László Moholy-Nagy at the newly established School of Design in Chicago. Like Fischinger, Moholy-Nagy advocated a tactile, interactive approach to the audiovisual experience, and his theories on the figure–ground relationship among photography, film, and kinetic sculpture were predicated on the notion of a “space-time accentuated visual art” that projected cinematic light into three-dimensional space in an effort to replicate the auditory experience of delineating spatial proximity and distance. During his tenure in Chicago, Cage developed a theory of sound effect in his “Landscape” series of compositions that played on the mimetic reflections of visuality in radio, epitomized by his commission for the Columbia Workshop production of The City Wears a Slouch Hat (1942). I examine this production in light of the issue of temporality in radio narrative, in which the lack of visual stimuli detemporalizes the narrative flow of Kenneth Patchen’s surrealist noir script. This interplay within temporalized and detemporalized narrative spaces became a central focus for filmmaker Maya Deren.

Maya Deren’s pioneering silent films from the 1940s detemporalized the cinematic experience by removing the sonic bond of an audio track and replaced this reality with an aesthetic of cinematic space based on theories of poetry and dance. As I argue, this approach was part of a larger dialogue among artists and intellectuals within the artistic enclave of Greenwich Village in New York. Cage was enmeshed with this community starting in 1942, and his interaction with Deren was largely facilitated through comparative mythologist Joseph Campbell. I outline a debate on the concept of “Significant Form” in the journal Dance Observer from 1944 to 1945, which culminated in Cage’s first theoretical essay on form as it relates to bodily articulation of space, “Grace and Clarity,” (1944) and its implications for Deren’s influential 1944 film At Land, in which Cage played a supporting actor role. Finally, this chapter culminates with an examination of

German filmmaker Hans Richter’s feature-length avant-garde film, Dreams That Money Can Buy (1947). Cage’s music for a section of the film, conceived and shot by Marcel Duchamp, presents a configuration of the audiovisual experience that projects timbral alterations in the prepared piano set against Duchamp’s rotoreliefs.

Chapter 3 centers on the relationships between acoustic projection and cinematic space, starting with Cage’s turn to chance and indeterminacy in the 1950s. I start with Cage’s rhetoric on the medium of magnetic tape as the second transformation of sound materiality, which moved away from the indexical print of sound phonography toward a virtual coding of information indeterminate to the naked eye yet determinate in duration. Building on art historian Julia Robinson’s notion of “symbolic investiture,” I survey the divided interpretations of Cage’s platform among musicologists that decode his music according to style analysis that established a compositional logic for his move to indeterminacy and the larger debate among art historians on the split between Neo-Avant- Garde and Abstract Expressionist aesthetics. I argue that Cage’s interaction with film and filmmakers provides a meeting ground for these debates within cinematic space in two films: Cage’s score for the Herbert Matter documentary on sculptor Alexander Calder in 1950, and colleague Morton Feldman’s score for the Hans Namuth and Paul Falkenberg documentary on Abstract Expressionist painter Jackson Pollock the following year. Both artists saw these commissions as opportunities to formalize connections between their compositional approaches to sound and the visual approach to space, kinetic movement, and ground revealed in the time-based poetics of the moving image.

In the final section of Chapter 3, I examine a film collaboration I discovered with the sculptor Richard Lippold that documented his monumental wire sculpture, The Sun, (1956) where Cage and Lippold applied chance procedures to the editing process. Following the principles of Russian Constructivist theories of kinetic light and rhythm, Lippold’s approach to his self-described “open sculptures” focused on themes of transparency and space rather than on mass and dimension by seamlessly integrating intricate constructions of bundled polished wire and tubing into the surrounding architecture. Cage’s and Lippold’s mutual concern for geometric abstraction, elaborate mathematical structures, and an open-ended spiritual discourse on the nature of the work of art sparked an important dialogue leading to the period of Cage’s most dramatic artistic gestures in the early 1950s. Lippold’s freestanding sculptures delicately articulated three-dimensional space, and the kinetic energy of their complex lattice arrangements mirrored Cage’s compositions for the prepared piano. Cage’s dislocation of the harmonic–nodal structure of the piano in turn projected acoustic simulacra with the same metallic shimmer of Lippold’s wire formations. Lippold’s commission came about as a result of his split with the so-called Irascible 18 collective of New York artists, and

the history of its commission and reception reflect both an ideological divide on the materiality of sculpture and larger postwar McCarthy-era politics of passivity and resistance.

Chapter 4 converges on the sound-in-film/sound-on-film dichotomy, when Cage revised his aesthetic stance on multimedia sound-system assemblages in the 1960s. Framed around a conference panel in 1967 at the University of Cincinnati, Cinema Now, in which Cage discussed the current state of Underground Cinema in the United States, Chapter 4 outlines Cage’s interaction with the “two Stans,” Stan Brakhage and Stan VanDerBeek, culminating in a detailed critique of Cage’s 1965 immersive interactive multimedia work, Variations V. I first begin with a detailed reading of the fundamental tenets of Cage’s negative aesthetic set forth in his seminal publication Silence (1961), exploring its implications for multimedia and intermedia theories in the 1960s. Two competing poles of interpretation of Cage’s theories surrounding chance and indeterminacy emerged from the first post- Cage generation. The first sought out a reduction of the artwork to its base materials in an act of contraction, whereas the second reached for the opposite, a total expansion of individual medium-specific artworks in a monumental Gesamtkunstwerk, epitomized by Stan VanDerBeek’s theories of expanded cinema and intermedia.

Although Cage’s interaction with filmmakers continued into the following decades, most notably with artists such as Peter Greenaway, Elliot Caplan, and Emile De Antonio, I choose to conclude in the 1960s, as this moment demarcates the boundary between Cage’s “heroic” period of influence and the emergence of the first of many post- Cagean generations that either worked in conjunction with or in direct opposition to Cage’s ideas and compositional techniques. A study of these additional documentaries on Cage and their effect on the cultural assimilation of Cagean notions of indeterminacy fall outside the parameters of the specific concerns of this study, namely the audiovisual relationships that the cinematographic experience might engender within the context of Cage’s artistic platform. 1969 also marked a significant moment of retreat from Cage’s Wagnerian multimedia extravaganzas and a move toward a late period of composition that explored themes of American transcendentalism. Although concise in terms of examples, this study aims to position each of Cage’s interactions with avant-garde filmmakers within the larger narrative of audiovisual studies in an effort to reorient our perspective of Cage away from the pure ontological model of listening, as it is only through the lens of audiovisuology that we can effectively characterize a Cagean notion of audiovisuality by looking both outward and within.