Thoracic Anesthesia Procedures

Edited by

Alan D. Kaye, MD, PhD, DABA, DABPM, DABIPP, FASA

Vice-Chancellor of Academic Affairs, Chief

Academic Officer, and Provost

Tenured Professor of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Neurosciences

LSU School of Medicine

Shreveport, LA, USA

Richard D. Urman, MD, MBA, FASA

Associate Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

Perioperative and Pain Medicine

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, MA, USA

3

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kaye, Alan D., editor. | Urman, Richard D., editor.

Title: Thoracic anesthesia procedures / Alan D. Kaye and Richard D. Urman.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020047807 (print) | LCCN 2020047808 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197506127 (paperback) | ISBN 9780197506141 (epub) | ISBN 9780197506158 (online)

Subjects: MESH: Thoracic Surgical Procedures | Anesthesia Classification: LCC RD536 (print) | LCC RD536 (ebook) | NLM WF 980 | DDC 617.9/6754—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020047807

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020047808 DOI: 10.1093/med/9780197506127.001.0001

This material is not intended to be, and should not be considered, a substitute for medical or other professional advice. Treatment for the conditions described in this material is highly dependent on the individual circumstances. And, while this material is designed to offer accurate information with respect to the subject matter covered and to be current as of the time it was written, research and knowledge about medical and health issues is constantly evolving and dose schedules for medications are being revised continually, with new side effects recognized and accounted for regularly. Readers must therefore always check the product information and clinical procedures with the most up-to-date published product information and data sheets provided by the manufacturers and the most recent codes of conduct and safety regulation. The publisher and the authors make no representations or warranties to readers, express or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of this material. Without limiting the foregoing, the publisher and the authors make no representations or warranties as to the accuracy or efficacy of the drug dosages mentioned in the material. The authors and the publisher do not accept, and expressly disclaim, any responsibility for any liability, loss, or risk that may be claimed or incurred as a consequence of the use and/or application of any of the contents of this material.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Marquis, Canada

To my wife Dr. Kim Kaye and my children, Aaron and Rachel Kaye, for being the best family a man could ask for in his life.

To my mother Florence Feldman who made me the man I am today.

Thank you to all my patients that I have had the honor to take care of over the past 30 plus years.

I am grateful to my mentors, friends, brother Adam, sister Sheree, and other family members for your support throughout my life.

—Alan D. Kaye, MD, PhD, DABA, DABPM, DABIPP, FASA

To my patients who inspired me to write this book to help other practitioners improve their care

To my mentors for their encouragement and support

To my students and trainees so that they can use this guide to better prepare to take care of their patients

To my family: my wife Dr. Zina Matlyuk-Urman, MD, my daughters Abigail and Isabelle who make it all possible and worth it, every day.

And finally, to my parents, Tanya and Dennis Urman.

—Richard D. Urman, MD, MBA, FASA

1. Normal Respiratory Physiology: Basic Concepts for the Clinician 1

Jordan S. Renschler, George M. Jeha, and Alan D. Kaye

2. Thoracic Radiology: Thoracic Anesthesia Procedures 17

Parker D. Freels, Gregory C. Wynn, Travis Meyer, and Giuseppe Giuratrabocchetta

3. Physiology of One-Lung Ventilation

Geetha Shanmugam and Raymond Pla

4. Bronchoscopic Anatomy

Geoffrey D. Panjeton, W. Kirk Fowler, Hess Panjeton, Yi Deng, and Jeffrey D. White

5. Preoperative Evaluation and Optimization

Alexandra L. Belfar, Kevin Duong, Yi Deng, and Melissa Nikolaidis

6. Lung Isolation Techniques

William Johnson, Melissa Nikolaidis, and Nahel Saied

7. Airway Devices for Thoracic Anesthesia and Ventilatory Techniques

Neeraj Kumar, Priya Gupta, and Indranil Chakraborty

8. Patient Positioning and Surgical Considerations

Phi Ho, Yi Deng, and Melissa Nikolaidis

9. Anesthetic Management Techniques in Thoracic Surgery

Henry Liu, Xiangdong Chen, Alan D. Kaye, and Richard D. Urman

10. Bronchoscopy and Mediastinoscopy Procedures

Justin W. Wilson

11. Anterior Mediastinal Masses

Kevin Sidoran, Hanan Tafesse, Tiffany D. Perry, and Tricia Desvarieux

12. Pneumonectomy

Lacey Wood and Antony Tharian

13. Anesthesia for Pleural Space Procedures

Harendra Arora and Alan Smeltz

14. Surgical Airway Management

Zipei Feng, Mengjie Wu, Melissa Nikolaidis, and Yi Deng

15. Bronchopleural Fistula

Jose C. Humanez, Saurin Shah, Thimothy Graham, Kishan Patel, and Paul Mongan

16. Esophagectomy

Tiffany D. Perry, Tricia Desvarieux, and Kevin Sidoran

17. Lung Transplantation

Loren Francis and Jared McKinnon

18. Postoperative Management and Complications in Thoracic Surgery

Daniel Demos and Edward McGough

19. Pulmonary Pathophysiology in Anesthesia Practice

Gary R. Haynes and Brian P. McClure

20. Anesthetic Management Techniques (Regional Anesthesia) 273

Tyler Kabes, Rene Przkora, and Juan C. Mora

21. Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery 299

Joseph Capone and Antony Tharian

22. Enhanced Recovery in Thoracic Surgery 315 Manxu Zhao, Zhongyuan Xia, and Henry Liu

Foreword

Historically, injury or disease within the chest was considered in most instances to be fatal. It would take hundreds of years to understand human anatomy and physiology for doctors and scientists to develop surgical techniques to provide surgeons and anesthesiologists the understanding and skills to work in a small space to treat diseases of the thorax.

Today, technological advances have paved the way for miraculous cures for infection, anatomical disorders, vascular abnormalities, malignant tumors, benign masses, and other thorax pathologies. These treatments promote healing for a wide variety of clinical conditions, and the evoluation of anesthesia techniques has allowed for less postoperative pain and improved outcomes.

We hope that our book, Thoracic Anesthesia Procedures, provides an inspiration for lessons in thorax surgery and anesthesia for medical students, residents, fellows, and attending staff. We have worked methodically to recruit experts from numerous medical fields and professional disciplines. The result is an easy to read and very visual book sharing expertise and knowledge in the field of thoracic surgery. We welcome your comments and hope you enjoy our book focused on thoracic disease and treatment.

Contributors

Harendra Arora, MD, FASA, MBA Professor

Department of Anesthesiology University of North Carolina School of Medicine

Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Alexandra L. Belfar, MD Assistant Professor Department of Anesthesiology

Michael E. DeBakey Veterans Affairs Medical Center Department of Anesthesiology

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX, USA

Joseph Capone, DO Resident Department of Anesthesiology

Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago, IL, USA

Indranil Chakraborty, MBBS, MD, DNB

Professor Department of Anesthesiology College of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Little Rock, AR, USA

Xiangdong Chen, MD, PhD Chairman and Professor Department of Anesthesiology

Tongji Medical College Wuhan Union Hospital Huazhong University of Science & Technology Wuhan, China

Daniel Demos, MD

Assistant Professor of Surgery Division of Thoracic and Cardiac Surgery Department of Surgery

University of Florida College of Medicine Gainesville, FL, USA

Yi Deng, MD

Assistant Professor of Cardiothoracic

Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine

Associate Director of Cardiothoracic

Anesthesiology at Ben Taub Hospital

Department of Anesthesiology

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX, USA

Tricia Desvarieux, MD

Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine

George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences Washington, DC, USA

Kevin Duong, MD

Resident Physician Department of Anesthesiology

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX, USA

Zipei Feng, MD, PhD

Resident Physician Department of Otolaryngology

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX, USA

Loren Francis, MD

Cardiothoracic Anesthesiologist

Department of Anesthesia and Perioperative Medicine

Medical University of South Carolina Charleston, SC, USA

Parker D. Freels, MD Physician

Department of Radiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Jacksonville, FL, USA

Giuseppe Giuratrabocchetta, MD

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Jacksonville, FL, USA

Thimothy Graham, MD

Department of Radiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Jacksonville, FL, USA

Priya Gupta, MD

Associate Professor Department of Anesthesiology

College of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Little Rock, AR, USA

Gary R. Haynes, MD, MS, PhD, FASA

Professor and the Merryl and Sam Israel Chair in Anesthesiology

Department of Anesthesiology

Tulane University School of Medicine

New Orleans, LA, USA

Phi Ho, MD

Resident Physician

Department of Anesthesiology

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, TX, USA

Jose C. Humanez, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Jacksonville, FL, USA

George M. Jeha

Medical Student

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center

New Orleans, LA, USA

William Johnson, MD

Resident Physician

Department of Anesthesiology

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, TX, USA

Tyler Kabes, MD

Resident Physician

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Gainesville, FL, USA

Alan D. Kaye, MD, PhD, DABA, DABPM, DABIPP, FASA

Vice-Chancellor of Academic Affairs, Chief Academic Officer, and Provost Tenured Professor of Anesthesiology, Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Neurosciences

LSU School of Medicine

Shreveport, LA, USA

W. Kirk Fowler, MD Physician

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Gainesville, FL, USA

Neeraj Kumar, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Anesthesiology College of Medicine, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Little Rock, AR, USA

Henry Liu, MD, MS, FASA Professor of Anesthesiology Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine

Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Hershey, PA, USA

Brian P. McClure, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

Tulane University School of Medicine

New Orleans, LA

Edward McGough, MD

Associate Professor of Anesthesia Divisions of Critical Care Medicine and Cardiac Anesthesia

Program Director

Cardiothoracic Anesthesia Fellowship Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Gainesville, FL, USA

Jared McKinnon, MD

Assistance Professor

Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine

Medical University of South Carolina Charleston, SC, USA

Travis Meyer, MD Physician

Department of Radiology

University of Florida Health, Clinical Center Jacksonville, FL, USA

Paul Mongan, MD Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville, FL, USA

Juan C. Mora, MD

Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine Gainesville, FL, USA

Melissa Nikolaidis, MD

Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology Department of Anesthesiology

Director of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology at Ben Taub Hospital

Baylor College of Medicine Houston, TX, USA

Geoffrey D. Panjeton, MD Fellow

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Gainesville, FL, USA

Hess Panjeton, MD

Northside Anesthesiology Consultants Atlanta, GA, USA

Kishan Patel, MD Physician

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville, FL, USA

Tiffany D. Perry

Raymond Pla, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care

George Washington University School of Medicine Washington, DC, USA

Rene Przkora, MD, PhD

Professor of Anesthesiology and Chief, Pain Medicine Division Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine

Gainesville, FL, USA

Jordan S. Renschler

Medical Student

Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center

New Orleans, LA, USA

Nahel Saied, MD

Professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care

University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Little Rock, AR, USA

Saurin Shah, MD Department of Anesthesiology

University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville, FL, USA

Geetha Shanmugam, MD

Assistant Professor of Medicine

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care

George Washington University School of Medicine

Washington, DC, USA

Kevin Sidoran, MD

Resident Physician

Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care

George Washington University Hospital Washington, DC, USA

Alan Smeltz, MD

Assistant Professor Department of Anesthesiology

University of North Carolina School of Medicine

Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Hanan Tafesse, MD

Anesthesia Resident Department of Anesthesiology

The George Washington University Hospital Washington, DC, USA

Antony Tharian, MD

Program Director

Department of Anesthesiology

Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago, IL, USA

Richard D. Urman, MD, MBA, FASA

Associate Professor

Department of Anesthesiology

Perioperative and Pain Medicine Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, MA, USA

Jeffrey D. White, MD Clinical Associate

Department of Anesthesiology University of Florida College of Medicine Gainesville, FL, USA

Justin W. Wilson, MD

Associate Professor of Anesthesiology and Director

Division of Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology

Department of Anesthesiology

University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio San Antonio, TX, USA

Lacey Wood, DO

Resident Department of Anesthesiology

Advocate Illinois Masonic Medical Center Chicago, IL, USA

Mengjie Wu, MD Resident Physician

Department of Anesthesiology UT Houston Houston, TX, USA

Gregory C. Wynn, MD Associate Professor

Department of Radiology University of Florida College of Medicine Jacksonville, FL, USA

Zhongyuan Xia, MD, PhD Professor and Chairman Department of Anesthesiology Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Hubei General Hospital Wuhan, China

Manxu Zhao, MD, MS Director

Department of Anesthesiology

Cedar Sinai Medical Center Los Angeles, CA, USA

1 Normal Respiratory Physiology

Basic Concepts for the Clinician

Jordan S. Renschler, George M. Jeha, and Alan D. Kaye

Physiological and Anatomical Consideration of Patient Positioning

Introduction

Patient positioning should optimize exposure for surgery while minimizing potential harm to the patient. Concerns for patient positioning include interfering with respiration or circulation, compressing peripheral nerves of skin, and causing musculoskeletal discomfort. Factors that should be considered when choosing optimal patient positioning include procedure length, the surgeon’s preference, the type of anesthesia administered, and patient specific risk factors, including age and weight.1

Supine

Supine is the most used surgical position and poses the lowest risk to patient2 (Figure 1.1). In the supine position the patient is placed on their back with the spinal column in alignment and legs extended parallel to the bed. Changing a person from upright to the supine position results in a fall of about 0.8 to 1 L in functional residual capacity (FRC).2,3 After induction of anesthesia, the FRC decreases another 0.4 to 0.5 L due to relaxation of the intercostal muscles and diaphragm. This drop in FRC contributes to small airway collapse and a decrease in oxygenation.

Lateral Decubitus: Closed Chest

The lateral decubitus position is often used in surgeries of the hip, retroperitoneum, and thorax (Figure 1.2). To achieve this position, patients are anesthetized supine then turned so the nonoperative side is in contact with the bed. The shoulders and hips should be turned simultaneously to prevent torsion of the spine and great vessels. The lower leg is flexed at hip, and the upper leg is completely extended. There is a decrease in FRC and total volumes of both lungs due to the patient being in a supine position. In lateral decubitus, the dependent

lung is better perfused due to gravity but has a decreased compliance to the increased intraabdominal pressure and pressure from the mediastinum.2 This leads to better ventilation of the poorly perfused, nondependent lung. These alterations result in significant ventilationperfusion mismatch.

Figure 1.1 Supine position.

Figure 1.2 Lateral decubitus position.

Open Chest

Opening the chest in lateral decubitus poses additional physiologic effects. Opening a large section of the thoracic cavity removes some constraint of the chest wall on the nondependent lung. This increases ventilation of the lung, which worsens the ventilation-perfusion mismatch.4 Because the intact hemithorax is generating negative pressures, the mediastinum can shift toward the closed section, changing hemodynamics in a potentially dangerous way. The closed hemithorax can also pull air from the open hemithorax, resulting in paradoxical breathing.5

Lung Isolation Techniques

Introduction

Lung isolation may be desired in surgery to optimize surgical access. By collapsing a single lung, the surgeon has greater access to the thorax and prevents puncturing the lung. Singlelung ventilation can also prevent contamination of healthy lung tissue by a diseased lung in cases of severe infection or bleeding. This section discusses methods of lung isolation including double-lumen tubes and bronchial blockers.

Anatomical Landmarks

The trachea is the entrance to the respiratory system and is kept patent by C-shaped cartilaginous rings. These rings maintain the structure of the trachea and are incomplete on the posterior aspect of the trachea. The trachea splits into the right and left mainstem bronchus at the carina (Figure 1.3). Notice the right bronchus lies in a more vertical plane and is typically shorter and wider. The right bronchus supplies the right lung, which has three lobes—the superior, middle, and inferior lobes—whereas the left lung consists of only the superior and

Figure 1.3 The trachea splits into the right and left mainstem bronchus at the carina.

(A)

(B)

inferior lobes and is supplied by the left bronchus. Each lobe is supplied by a secondary bronchus, coming from the respective mainstem bronchus. Secondary bronchi split further into bronchioles.

Double-Lumen Tubes

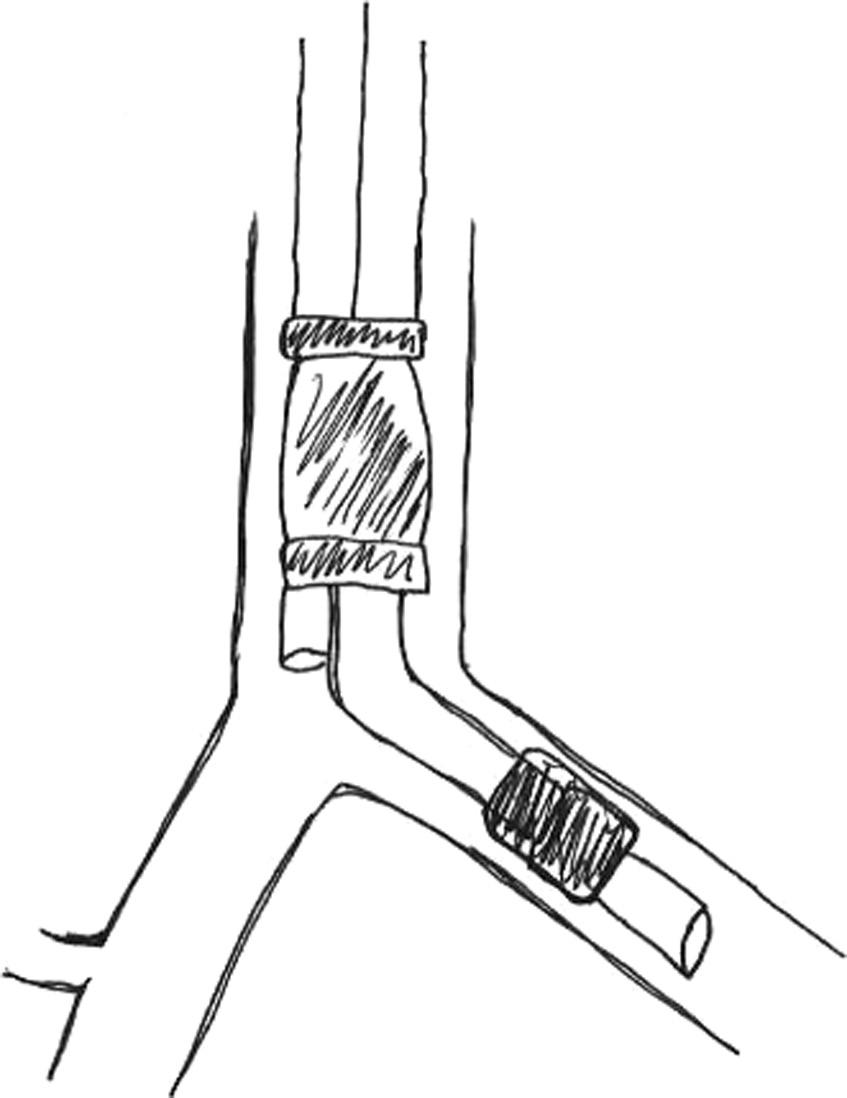

Double-lumen tubes are the main method of anatomical and physiologic lung isolation in most thoracic surgery cases. Double-lumen tubes are composed of two unequal length endotracheal tubes molded together. The longer tube has a blue cuff and is designed to sit in the primary bronchus, while the shorter tube has a clear cuff and is placed in the trachea (Figure 1.4). By inflating the tracheal cuff and deflating the bronchial cuff, ventilation of both lungs is achieved. Lung isolation is achieved when the bronchial cuff is inflated.6

• Double-lumen tubes come in right and left models. Adult double-lumen tubes are available in different sizes: 25 Fr, 28 Fr, 32 Fr, 35 Fr, 37 Fr, 39 Fr, and 41 Fr. 39 Fr and 41 Fr are commonly used in adult males, and 35 Fr and 37 Fr are used for adult females.7 Size choice should prevent trauma or ischemia to the airway from a tube too large, but it must be large enough to adequately isolate the lung when inflated. The tubes should pass without resistance during insertion. Smaller tubes are more likely to be displaced and are more difficult to suction and ventilate through. Double-lumen tubes are also commercially available

Figure 1.4 A 39 Fr double lumen tube demonstrating the tracheal limb, bronchial limb, oropharyngeal curve, tracheal cuff, and bronchial cuff (A). An enlarged image displaying the bronchial and tracheal limbs (B).

for patients with tracheostomy and are shorter and curved between the intratracheal and extratracheal components.

• Components of double-lumen tube package:

• Double-lumen tube

• Adaptor for ventilation of both ports

• Extension for each port

• Stylet

• Suction catheter

• Apparatus to deliver continuous positive pressure airway to the nonventilated lung (variable depending on manufacturer)

• Additional equipment:

• Laryngoscope blade

• Fiberoptic bronchoscope

• Stethoscope

• Hemostat to clamp the tube extension on the nonventilated side

• Blind placement7:

• Preparation: Prior to the case, prepare and assemble the supplies to prevent delays later. Lubricate the stylet and place it into the double-lumen tube. Connect the adaptor to both port extension.

• Intubating the patient: Visualize the vocal cords by direct laryngoscopy. Advance the double-lumen tube with the bronchial tip oriented so the concave curve faces anteriorly through the vocal cords until the bronchial cuff passes the cords. Rotate the tube 90o to the left when using a left-sided tube or to the right if using a right-side tube. Then advance the tube until there is resistance, while having another clinician remove the stylet. Attach the adaptor/extension piece. Following adequate positioning, inflate the tracheal cuff. Confirm both lungs are being ventilated by visualized chest rise and auscultation. Next verify ventilation from the bronchial lumen by inflating the bronchial cuff 1 mL at a time until leak stops. Stop gas flow through the tracheal lumen, then open the tracheal sealing cap to air. Clamp off gas flow through the bronchial lumen to confirm isolation of the other lung through the tracheal lumen. Connect the double-lumen tube to the ventilator circuit using the connector provided in the packaging. End-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2) confirms placement in the trachea. Oxygenate the patient fully with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 100%.

• Confirmation of placement: Confirm correct placement of the tube using a fiberoptic bronchoscope through the endotracheal lumen (gold standard), by auscultation, and/or with lung ultrasound.

• Relative contraindications: Placement of a double-lumen tube is difficult due to the larger size and design; therefore, relative contraindications include a difficult airway, limited jaw mobility, a tracheal constriction, and a pre-existing trachea or stoma. In these cases, a single lumen tube with a bronchial blocker is an advisable alternative.

• Considerations:

• Left-sided double-lumen tubes have a higher margin of safety because the left primary bronchus is longer than the right.

• The proximity of the right-upper lobe bronchus to the carina poses an additional challenge in placing a right-sided double-lumen tube.8

• Reviewing prior lung imaging may aid in locating the right upper lobe position relative to the right primary bronchus.

Bronchial Blocker

Bronchial blockers are another method used for selective ventilation of an individual lung. The blocker is a catheter with a balloon at the tip that is inflated to occlude the lung of the bronchus it is placed in. Open-tipped bronchial blockers offer the ability to apply continuous positive pressure and to suction the airway, making them more useful than the alternative close-tipped bronchial blockers.6 The smallest size is a 2 French, which may be used in a 3.5 or 4.0 mm endotracheal tube. Proper placement of bronchial blockers is especially difficult in smaller children. To assure proper placement of the bronchial blocker, one must visualize key anatomical structures during placement. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is a reliable method to confirm proper placement of the bronchial blocker.

Advantages of bronchial blockers compared to double-lumen tubes include bronchial blockers utility in airway trauma, ability to be placed through an existing endotracheal tube, and ability to selectively block a lung lobe.9,10 Disadvantages include being especially difficult to place, particularly in the right upper lobe, as well as being more likely to be dislodged.

• Placement of bronchial blocker

• Preparation: Prior to intubation, verify that the bronchial blocker attached to the fiberoptic scope fits through the endotracheal tube.

• Intubation: Using a single-lumen tube, intubate the trachea. Confirm endotracheal tube intubation with end-tidal CO2 and auscultation. Fully ventilate the patient with a fraction of inspired oxygen of 100% prior to placing the bronchial blocker.

• Placement of the bronchial blocker: Attach the blocker to the very distal tip of the fiberoptic bronchoscope using the loop/lariat of the blocker. Advance the attached bronchial blocker into the endotracheal tube. Use the fiberoptic bronchoscope to visualize the airway, guiding the blocker into the selected primary bronchus. Place the bronchial blocker by releasing the loop/lariat that connect the blocker to the fiberoptic bronchoscope. Withdraw the bronchoscope to slightly above the carina and visualize the primary bronchi. While observing from this view, inflate the balloon with air or saline as instructed by the manufacturer. Remove the fiberoptic bronchoscope and auscultate to confirm positioning of blocker. Confirm that peak airway pressures are appropriate and not excessive.

• Risks: Bronchial blockers may cause local trauma to the tracheal mucosa during placement. Additionally, using a bronchial blocker or overinflation of the balloon that is too large can damage the mucosa of the airway. If the bronchial block is inflated within the trachea ventilation of both lungs is blocked.

Bronchoscopy

Bronchoscopy allows for visualization of the airways and has utility in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. There are two main types of bronchoscopes, rigid and flexible. The rigid bronchoscope is a metal tube with a beveled tip. The flexible bronchoscope has several variations. Traditionally, they have a long flexible tube encircling a fiberoptic system with a light source. The handle of the scope has an eyepiece, control lever for tip movement, suction button, and access to the suction channel.11 Indications for rigid and flexible bronchoscopes overlap, but flexible bronchoscopes are preferred in confirmation of double-lumen tube and bronchial blocker placement.12

Indications for Bronchoscopy

Diagnostic Therapeutic

Tracheoesophageal fistula, hemoptysis

management, chronic cough, stridor, nodal staging of lung cancer, hilar lymphadenopathy tracheomalacia, posttransplant surveillance, pulmonary infiltrates

Lung resection, hemoptysis management, foreign body removal, airway dilatation and stent placement, lavage, tumor debulking, thermoplasty for asthma13

When using a double-lumen tube or bronchial blocker, fiberoptic bronchoscopy is a reliable method to confirm tube placement and lung isolation.14 Auscultation is less reliable for determining adequate ventilation of the selected lung. Mispositioning of the double-lumen tube can result in hypoventilation, hypoxia, atelectasis, and respiratory collapse.15

When using fiberoptic bronchoscopy to confirm the position of a blindly inserted tube, it is advanced through the tracheal lumen to confirm11:

• The bronchial portion is in the correct bronchus.

• The bronchial cuff does not cover the carina.

• The bronchial rings are anterior and longitudinal fibers are posterior.

When advancing the bronchoscope through the endobronchial lumen:

• For left-sided tubes, visualize the origins of the left upper and lower bronchi to assure the endobronchial tip is not occluding a bronchi.

• For the right-sided tube, because of the alternate size and angle, ensure the alignment between the opening of the endobronchial lumen and the opening of the right upper lobe bronchus is optimal. Visualize the middle and lower bronchus as patent and ventilated.

Bronchoscopy may be used to aid in placing the double-lumen tube by placing the bronchoscope through the bronchial lumen and positioning the double-lumen tube over the scope.

• Complications: Potential complications of bronchoscopy include laryngospasm, bronchospasm, hypoxemia, mucosal damage resulting in bleeding, pneumothorax, cardiac arrhythmias, and exacerbation of hypoxia. The benefits of bronchoscopy must outweigh the risks.

Pulmonary Function Changes During Thoracic Anesthesia Introduction

During thoracic anesthesia, a significant reduction in pulmonary function occurs, with a decrease of up to 50% in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity, and FRC.16 Anesthetic agents themselves, particularly the volatile anesthetics, lead to hypercarbia and hypoxia. Depression of reflexes, increased secretions, changes in hemodynamics, and alterations in rib cage movement during thoracic anesthesia further alter pulmonary function. These alterations lead to a high risk of hypoxia and atelectasis, resulting in respiratory complications comprising most perioperative causes of morbidity and mortality.

Lung Mechanics and Pulmonary Function

The lungs’ primary function is to maintain oxygenation and remove CO2 from the blood, thus allowing for respiration at the cellular level to occur. Arterial CO2 is detected by chemoreceptors of the carotid body and medulla and is the primary driver of respiration. Patent alveoli and capillaries within the lung are the site of gas diffusion. Alveolar ventilation (Va) refers to the gas exchange occurring between the alveoli and external environment, while perfusion (Q) is the blood flow the lung receives. Perfusion of the lung tissue is heavily dependent on gravity, so patient positioning alters which areas of the lung are most perfused.17 Different methods of thoracic anesthesia and positioning of the patient alter Va and Q. Thoracic anesthesia causes a dose-dependent decrease in minute ventilation, or the total volume the lung receives in 1 minute.18 The additional decrease in FRC and FEV1 leads to alveolar collapse and an increase of shunting within the lungs. Some of this loss of lung function can be overcome with positive end-expiratory pressure and alveolar recruitment maneuvers, improving overall patient outcomes. Mechanical ventilation improves the Va/Q ratio by increasing the volume of air the lung receives and limiting atelectasis.19

Predictive Postoperative Pulmonary Lung Function

FEV1 and the diffusion capacity of CO2 are quantitative preoperative assessment values of thoracic anesthesia patients undergoing partial lung resection. FEV1 is a measure of the respiratory mechanics whereas diffusing capacity for CO2 (DLCO) measures the lung parenchymal function. Reduction in FEV1 and DLCO are associated with increased respiratory morbidity and mortality rates.20 In the setting of a normal FEV1, DLCO should still be measured because of its utility in predicting morbidity in patients with no airflow limitations.21,22

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second

ppoFEV1% = preoperative FEV1% × (1 %functional lung tissue removed/100)

A predicted postoperative FEV1 percentage (ppoFEV1%) above 40% is low risk for postoperative respiratory complication, while less than 30% is considered high risk.23 Following the surgery, the remaining lung will compensate and eventually FEV1 will increase slightly.24

Diffusion Capacity of CO2

ppoDLCO = preoperative DLCO × (1 %functional lung tissue removed/100)

Diffusion capacity is a measure of gases ability to cross the alveolar-capillary membranes. A predicted postoperative DLCO percentage (ppoDLCO) less than 40% is correlated with increased postoperative cardiopulmonary complications.21 DLCO is the strongest predictor for morbidity and mortality after lung resection and predicts cardiopulmonary complications in the setting of a normal FEV1. The DLCO value has also been associated with postoperative quality of life and long-term survival.22 Guidelines recommend DLCO measurement prior to lung resection in all cases.

One-Lung Ventilation

Introduction

In most circumstances, the lungs of patients undergoing mechanical ventilation are inflated and deflated in unison. In some instances, however, it is beneficial to mechanically separate the two lungs to ventilate only one lung while the other is deflated. This is termed one-lung ventilation (OLV). OLV is commonly used to provide exposure to the surgical field during thoracic surgery or to anatomically isolate one lung from pathologic processes related to the other lung.

Indications for One-Lung Ventilation

OLV is routinely utilized to enhance exposure of the surgical field in a variety of surgical procedures, including:

• Pulmonary resection (including pneumonectomy, lobectomy, and wedge resection).

• Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (including wedge resection, biopsy, and pleurodesis).

• Mediastinal surgery.

• Esophageal surgery.

• Thoracic vascular surgery.

• Thoracic spine surgery.

• Minimally invasive cardiac valve surgery.

The nonsurgical indications for OLV include6:

• Protective isolation of one lung from pathologic processes occurring in the contralateral lung, such as:

• Pulmonary hemorrhage.

• Infection or purulent secretions.

• Control of ventilation in circumstances such as:

• Tracheobronchial trauma.

• Broncho-pleural or broncho-cutaneous fistula.

Methods of Lung Separation

There are three methods used to isolate a lung:

1. Single-lumen endobronchial tube: The single-lumen endobronchial tube differs from normal endotracheal tube in that the former has a smaller external diameter, smaller external cuff, and longer length. The single-lumen endobronchial tube is utilized far less frequently than the double-lumen endobronchial tube for achieving lung isolation but may be useful in emergency situations in select patients with abnormal tracheobronchial anatomy or in cases involving small children.8,9 Placement of a single-lumen endobronchial tube within the right or left mainstem bronchus allows for ventilation of only the intubated lung, while the contralateral lung is allowed to spontaneously collapse.

2. Double-lumen endobronchial tube: Since its introduction in the 1930s, the double-lumen endobronchial tube has been the most commonly utilized method of lung isolation. Its design consists of two separate lumens: a bronchial lumen and a tracheal lumen. This allows for isolation, selective ventilation, and intermittent suctioning of either lung.6,8,9

3. Endobronchial blockers: Endobronchial blockers are inflatable balloon-tipped stylets which may be placed within the mainstem bronchus, resulting in collapse of lung distal to the blocker.9,25,26

Physiology

By inhibiting the ventilation of one lung, single-lung ventilation alters normal respiratory physiology. Disruption of normal respiratory physiology is often followed by the development of hypoxemia. Hypoxemia in the context of one lung ventilation may be attributable to several factors, including reduced oxygen stores, lung compression, dissociation of oxygen from hemoglobin, and matching of ventilation and perfusion.8,27,28

• Reduced oxygen stores: Because one lung is collapsed during OLV, the FRC is reduced. Accordingly, there is a decrease in the body’s stores of oxygen. Additionally, the disease process at play within the thorax may contribute to decreased oxygen stores.

• Lung compression: Compression of the ventilated lung may contribute to hypoxemia. During OLV, the ventilated lung may be compressed by the weight of the mediastinum. After diaphragmatic paralysis, the weights of the abdominal contents may also contribute to compression of the ventilated lung.6,28,29

• Oxygen dissociation from hemoglobin: During OLV, the absence of ventilation to one lung reduces the surface area available for gas exchange by approximately one half, leading to a reduction in arterial partial pressure of oxygen and increased CO2 levels. The result is more rapid dissociation of oxygen from hemoglobin. This phenomenon is known as the Bohr effect.8,28,30

• Ventilation and perfusion matching: Under normal circumstances, ventilation and perfusion are anatomically well-matched. However, during OLV, ventilation is interrupted to one of the lungs while its perfusion remains unaffected. This wasted perfusion leads to the development of a right-to-left intrapulmonary shunt and relative hypoxemia. In practice, however, the shunt fraction is actually lower than expected. The reasons for this are as follows6,8:

• Manipulation of the nonventilated lung leads to partial obstruction of its blood supply.

• By positioning the patient in the lateral position, gravity causes an increase in perfusion to the ventilated lung.

• Blood flow to hypoxic and poorly ventilated regions of the lung is diverted to more ventilated segments via the mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction.

Optimum Driving Pressure

Driving pressure (ΔP) is calculated as the difference between airway pressure at the end of inspiration (plateau pressure, Pplat) and positive end-expiratory airway pressure (PEEP). Two pressures comprise the driving pressure: the transpulmonary pressure (ΔPL) and the pressure applied to the chest wall (ΔPcw). By rearranging the standard respiratory compliance (CRS) equation, it is demonstrated that driving pressure equals the tidal volume (VT) divided by CRS. Consequently, driving pressure can be interpreted as the tidal volume corrected for the patient’s CRS and thus related to global lung strain. When adjusting the tidal volume, driving pressure may be used as a safety limit to minimize lung strain in intubated patients. Although optimal driving pressure is the subject of ongoing research, it is currently generally accepted that safe driving pressures lie between 14 and 18 cm H2O.31–33