Contributors

Adrian Alsmith, PhD

Lecturer in Philosophy (Mind and Psychology)

Department of Philosophy

King’s College London London, UK

Tommaso Bertoni, PhD Student

Lemanic Neuroscience Doctoral Program

UNIL Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Department of Radiology University Hospital and University of Lausanne Lausanne, Switzerland

Elvio Blini, PhD

Postdoc Fellow

Department of General Psychology University of Padova Padova, Italy

Claudio Brozzoli, PhD Researcher

Integrative Multisensory Perception Action & Cognition Team (ImpAct)

INSERM, CNRS, and Lyon Neuroscience Center Lyon, France

R.J. Bufacchi, PhD

Postdoc

Department of Neuroscience, Physiology and Pharmacology

Centre for Mathematics and Physics in the Life Sciences and Experimental Biology (CoMPLEX) University College London London, UK

Michela Candini, PhD

Postdoctoral Researcher Department of Psychology University of Bologna Bologna, Italy

Justine Cléry, PhD

Post-Doctoral Associate

Robarts Research Institute and BrainsCAN University of Western Ontario London, ON, Canada

Yann Coello, PhD Professor of Cognitive Psychology and Neuropsychology University of Lille Lille, France

Frédérique de Vignemont, PhD Director of Research Institut Jean Nicod Department of cognitive studies

ENS, EHESS, CNRS, PSL University Paris, France

H.C. Dijkerman, DPhil Professor of Neuropsychology

Helmholtz Institute, Experimental Psychology Utrecht University Utrecht, The Netherlands

Alessandro Farnè, PhD Director of Research

Integrative Multisensory Perception Action & Cognition Team (ImpAct)

INSERM, CNRS, and Lyon Neuroscience Center Lyon, France

Francesca Frassinetti, MD, PhD Full Professor Department of Psychology University of Bologna Bologna, Italy

Matthew Fulkerson, PhD Associate Professor Department of Philosophy

UC San Diego La Jolla, CA, USA

Michael S.A. Graziano, PhD Professor

Psychology and Neuroscience Princeton University Princeton, NJ, USA

Fadila Hadj-Bouziane, PhD Researcher

Integrative Multisensory Perception Action & Cognition Team (ImpAct)

INSERM, CNRS, and Lyon Neuroscience Center Lyon, France

Suliann Ben Hamed, PhD

Director of the Neural Basis of Spatial Cognition and Action Group Institut des Sciences Cognitives Marc Jeannerod (ISCMJ) Lyon, France

Tina Iachini, PhD Professor

Department of Psychology University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli Caserta, Italy

G.D. Iannetti, MD, PhD Professor

Ianettilab, UCL London, UK

Colin Klein, PhD

Associate Professor School of Philosophy

The Australian National University Canberra, ACT, Australia

Alisa Mandrigin, PhD

Anniversary Fellow Division of Law and Philosophy University of Stirling Stirling, UK

Mohan Matthen, PhD Professor Philosophy University of Toronto Toronto, ON, Canada

W.P. Medendorp, PhD Principal Investigator

Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour

Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands

Anders Pape Møller, PhD

CNRS Senior Researcher

Ecologie Systematique Evolution PARIS, France

Jean-Paul Noel, PhD Post-Doctoral Associate Center for Neural Science

New York University New York City, NY, USA

Matthew Nudds, PhD Professor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Warwick Coventry, UK

George D. Park, PhD

Senior Human Factors Engineer Systems Technology, Inc. Hawthorne, CA, USA

Giuseppe di Pellegrino, MD, PhD Full Professor Department of Psychology University of Bologna Bologna, Italy

Catherine L. Reed, PhD Professor of Psychological Science and Neuroscience

Claremont McKenna College Claremont, CA, USA

Andrea Serino, PhD Professor and Head of Myspace Lab CHUV, University Hospital and University of Lausanne Lausanne, Switzerland

Hong Yu Wong, PhD Professor and Chair of Philosophy of Mind and Cognitive Science University of Tübingen Tübingen, Germany

Wayne Wu, PhD Associate Professor Department of Philosophy and Neuroscience Institute

Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Peripersonal space

A special way of representing space

Frédérique de Vignemont, Andrea Serino, Hong Yu Wong, and Alessandro Farnè

1.1 Introduction

It is easy to believe that our representation of the world is structured under a binary mode: there is the self and then there is the rest of the world. However, one can question this conception in light of recent evidence on the existence of what is known as ‘peripersonal space’, which we may think of as something like a buffer zone between the self and the world. As a provisional definition, we can say that peripersonal space corresponds to the immediate surroundings of one’s body. Nonetheless, it should be noted, even at this early stage, that the notion of peripersonal space does not refer to a well-delineated region of the external world with sharp and stable boundaries. Instead it refers to a special way of representing objects and events located in relative proximity to what one takes to be one’s body. Indeed, as we shall see at length in this volume, peripersonal processing displays highly specific multisensory and motor features, distinct from those that characterize the processing of bodily space and the processing of far space. Depending on the context, the same area of physical space can be processed as peripersonal or not. This does not entail that any location in space can be perceived as peripersonal, but only that there is some degree of flexibility. Now, when some area of space is perceived as peripersonal, it is endowed with an immediate significance for the subject. Objects in one’s surroundings are directly relevant to the body, because of their potential for contact. With spatial proximity comes temporal proximity, which gives rise to specific constraints on the relationship between perception and action. There is no time for deliberation when a snake appears next to you. Missing it can directly endanger you. You just need to act.

It may then seem tempting to reduce the notion of peripersonal space to the notion of behavioural space, a space of actions, but this definition is both too wide and too narrow. It is too wide because the space of action goes beyond peripersonal space. Actions can unfold at a relatively long distance: for instance, I can reach for the book at the top of the shelf despite it being relatively distant from my current location at the writing desk. On the other hand, the definition is too narrow because the space that surrounds us is represented in a specific way no matter whether we plan to act on it or not. There is thus something quite unique about peripersonal space, which requires us to explore it in depth.

Despite the intuitive importance of peripersonal space, it is only recently that the significance of the immediate surroundings of one’s body has been recognized by cognitive science. The initial discovery that parietal neurons respond to stimuli ‘close to the body’ was made by Leinonen and Nyman (1979), but it was Rizzolatti and his colleagues who described the properties of premotor neurons specifically tuned to this region of space in 1981 and named

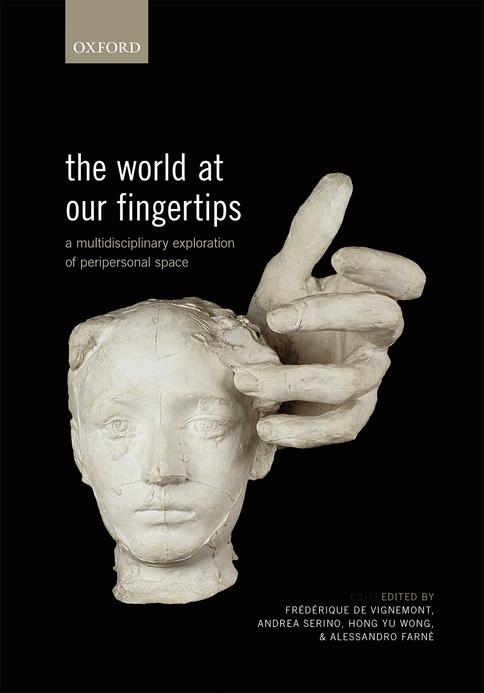

Frédérique de Vignemont, Andrea Serino, Hong Yu Wong, and Alessandro Farnè, Peripersonal space In: The World at Our Fingertips. Edited by Frédérique de Vignemont, Andrea Serino, Hong Yu Wong, and Alessandro Farnè, Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198851738.003.0001.

it ‘peripersonal space’ (Rizzolatti et al., 1981). Detailed neurophysiological exploration of this still unknown territory had to wait until the late 1990s, in monkeys (e.g. Graziano and Gross, 1993) and in human patients (e.g. di Pellegrino et al., 1997). Since then, there has been a blooming of research on peripersonal space in healthy human participants with the help of new experimental paradigms (such as the cross-modal congruency effect, hereafter ‘CCE’, Spence et al., 2004) and new tools (such as virtual reality, Maselli and Slater, 2014). For the first time, leading experts on peripersonal space in cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, neuroscience, and ethology are gathered in this volume to describe the vast number of fascinating discoveries about this special way of representing closeness to one’s body along with their ongoing research. For the first time too, these empirical results and approaches are brought into dialogue with philosophy.

Our aim in this introduction is not to summarize the 18 chapters that this volume includes. Instead, we offer an overview of the key notions in the field and the way they have been operationalized. We then consider some of the implications of peripersonal space for fundamental issues in the philosophy of perception and for self-awareness.

1.2 Theoretical and methological challenges

What is peripersonal space? Surprisingly, perhaps, this is one of the most difficult questions that the field has had to face these past 30 years. To better understand the notion of peripersonal space, it is helpful to contrast it with notions that may be more familiar in the literature and that are closely related. In particular, we shall target the notions of personal space, reaching space and egocentric space. We shall then turn to the different experimental paradigms and the questions they leave open.

1.2.1 Personal space

Historically, the idea that space around the subject is not represented uniformly was first described in ethology and in social psychology. On this approach, the boundaries are defined exclusively in social terms and vary depending on the type of social interactions, whether negative or positive. The Swiss biologist Heini Hediger (1950), director of the Zurich zoo, first described how animals react in specific ways depending on the proximity of approaching predators. Each of the distances between the prey and the predator (flight, defence, and critical) is defined in terms of the specific range of actions that it induces. Animals also react differently to conspecifics depending on their proximity. Hediger, for instance, distinguishes between personal distance (the distance at which the presence of other animals is tolerable) and social distance (the distance at which one needs to be to belong to the group). Later, the social psychologist Hall (1966) introduces more distinctions: intimate space, in which we can feel the warmth of another person’s body (up to 45 cm); personal space, in which we can directly interact with the other (up to 1.2 m); social space, in which we can work or meet together (up to 3.6 m); and public space, in which we have no involvement with other people. He concludes: ‘Each animal is surrounded by a series of bubbles or irregularly shaped balloons that serve to maintain proper spacing between individuals’ (Hall, 1966, p. 10). Hall’s work linked these distinctions to key features of human societies and described how they shape social interactions, how they vary between cultures (e.g. European vs Asian), and how they influence the design of architectural spaces (e.g. houses, workplaces).

Although of great interest, the analysis of most of these bubbles remains purely descriptive. There is both the risk of unwarranted proliferation and that of undue conflation across concepts and terminology. Moreover, space is only considered in its social dimension. The definition of peripersonal space, by contrast, includes not only the proximity of individuals but of objects too. It would thus be a category mistake to confuse personal space and peripersonal space. Indeed, some studies point to dissociations between the two (Patané et al., 2017). Clearly marking the distinction between the two notions, however, should not prevent us from exploring their relationship.

1.2.2 Reaching space

Another notion that is often discussed together with peripersonal space is the notion of reaching space. It is functionally defined as the distance at which an object can be reached by the subject’s hand without moving her trunk. The two notions are sometimes reduced one to the other, but we believe that they should be carefully distinguished. To start with, reaching space is typically larger than peripersonal space although they can spatially overlap. A second difference between the two notions is that reaching space refers to a unique representation that is shoulder-centred. By contrast, there are several distinct representations of peripersonal space, which are centred respectively on the hand, the head, the torso, and the feet. A third difference is at the neural level. Both the representations of reaching space and of peripersonal space involve fronto-parietal circuits but they include different brain areas. Reaching representation is associated with the dorsal premotor cortex, primary motor cortex, supplementary motor area (SMA), and parietal areas 5 and 7. On the other hand, peripersonal representation is associated with the ventral and dorsal premotor cortex, ventral intraparietal area, intraparietal sulcus (IPS), and putamen.

The final major difference concerns the functional role of these two representations. Most research in cognitive neuroscience has restricted their investigation to bodily movements such as reaching, grasping, or pointing. These movements allow us to act on the world, to explore it, and to manipulate objects. From an evolutionary point of view, these are the movements whose ultimate function is to find food and to eat. Reaching space is exclusively concerned by this type of movement. But there is another class of movements, possibly even more important, whose function concerns a different dimension of survival—namely, selfdefence. These movements are sometimes summarized by the famous ‘3 Fs’: freeze, fight, flight. One should not think, however, that we engage in protective behaviour only when there are predators. In everyday life, we avoid obstacles in our path, we retract our hand when coming too close to the fire, we tilt our shoulder when walking through a door, and so forth. Unlike the representation of reaching space, the representation of peripersonal space plays this dual role: to engage with the world but also to protect oneself from the world (de Vignemont, 2018).

1.2.3 Egocentric space

Standard accounts of perception acknowledge the importance of the spatial relation between the subject and the perceived object: objects are seen on the left or right, as up or down, and even as close or far from the subject’s body. These egocentric coordinates are especially important for action planning. One might then wonder what is so special about

peripersonal perception. For some, there is actually no difference between egocentric space and peripersonal space. They are both body-centred and have tight links to action (Briscoe, 2009; Ferretti, 2016). However, it is important to clearly distinguish the frame of reference that is exploited by peripersonal perception from the egocentric frame of perception in general. Egocentric location of objects is encoded in external space, and not in bodily space. Although body parts, such as the eyes, the head, and the torso, are used to anchor the axes on which the egocentric location is computed, the egocentric location is not on those body parts themselves. By contrast, the perceptual system anticipates objects seen or heard in peripersonal space to be in contact with one part or another of the body. Hence, although the objects are still located in external space, they are also anticipated to be in bodily space. The reference frame of peripersonal perception is thus similar to the somatotopic frame used by touch and pain (also called ‘skin-based’ or ‘bodily’ frame). To illustrate the difference from the egocentric frame, consider the following example:

There is a rock next to my right foot (somatotopic coordinates) on my right (egocentric coordinates). I then cross my legs. In environmental space, the egocentric coordinates do not change (I still see the rock on my right) but the rock is now close to my left foot, and the somatotopic coordinates thus change.

An interesting hypothesis is that the multisensory-motor mechanism underlying peripersonal processing contributes to egocentric processing by linking multisensory processing about the relationship between bodily cues and environmental cues (computed by posterior parietal and premotor areas) with visual and vestibular information about the orientation of oneself in the environment (computed in the temporo-parietal junction). This proposal might provide insight into how egocentric space processing is computed, which is less studied and less well understood compared with allocentric space processing, which is computed by place and grid cells in medio-temporal regions (Moser et al., 2008).

1.2.4 Probing peripersonal space

We saw that one of the main challenges in the field is to offer a satisfactory definition of peripersonal space that is specific enough to account for its peculiar spatial, multisensory, and motor properties. There have been a multitude of proposals but they remain largely controversial and have given rise to much confusion. Another source of confusion can be found in the multiplicity of methods used to experimentally investigate peripersonal space. Using diverse experimental tasks, different studies have highlighted specific measures and functions of peripersonal space (see Table 1.1).

Emphasis can be put either on perception or on action, on impact prediction or on defence preparation. A prominent category of studies employed tactile detection or discrimination tasks, using multisensory stimulation to probe perceptual processes. One of these approaches (the CCE and its variants) consists in the presentation of looming audio-visual stimuli combined with tactile ones. It has consistently revealed the fairly limited extension of the proximal space for which approaching stimuli can facilitate tactile detection. It has also been used to show the plasticity of the representation of peripersonal space after manipulations such as the rubber hand illusion, full body illusion, and tool use. Other paradigms focus on bodily capacities. For instance, the reachability judgement task probes the effect of perceived distance on the participants’ estimate of their potential for action. The

Table 1.1 Experimental measures of peripersonal space

Stimulus Modality

Visual & Tactile (V-T)

Auditory & Tactile (A-T)

V & A task irrelevant

T target modality

Visual & Tactile (V-T)

V task irrelevant

T target modality

Visual V target modality

Visual V target modality

Strong tactile or nociceptive

No task

Visual & Tactile (V-T)

V task irrelevant

T target modality

Stimulus Position

Visual and auditory at various distances or looming

Touch on the hand, head, or trunk

Visual at various distances

Touch on index or thumb

Visual at various distances

Visual at various distances

Response

Peripersonal Effect

Tactile detection Better accuracy and/ or faster reaction times with V closer to the body

Tactile discrimination (index or thumb)

Visual object detection or discrimination

Judgement if reachable by the hand or not (without moving)

Touch at the hand, kept at various distances from the face

Visual object far from hand

Touch on index or thumb of the grasping hand

Hand-blink reflex (HBR; motor-evoked response recorded from the face)

Tactile discrimination (index or thumb)

Slower reaction times with V closer to the body

Faster reaction times with V closer to the body

Slower reaction times and accuracy at chance level (50%, i.e. threshold) when V presented at around arm length

HBR increases at shorter hand–face distances

Slower reaction times when planning to move or moving toward object

extent of peripersonal space and its dynamic features have also been tackled by joining perceptual multisensory and action tasks concurrently. Finally, in probing the defensive function of peripersonal space, the relative proximity to the head of nociceptive or startling tactile stimuli has been shown to modulate physiological responses (e.g. the hand blink reflex).

As can be seen from inspection of the (non-exhaustive) Table 1.1, a variety of methods have been proposed to study the representation of peripersonal space, which likely tap into diverse physiological and psychological mechanisms. There is a risk of losing the homogeneity of the notion of peripersonal space within this multiplicity of methods. Ideally, one should design experimental paradigms for them to best investigate the notion to study. However, in the absence of a robust definition, the tasks may come first and the notion is constantly redefined on the basis of their results. If there is more than one method, this may give rise to a multiplicity of notions. We believe that it will be beneficial to use multiple tasks to address the same question, especially for the purposes of determining whether there are different notions of peripersonal representation. Beyond the methodological value of such an effort, this route holds the potential to provide more operationally defined and testable definitions of peripersonal space, with the promise of strengthening the theoretical foundations of the notion.

In addition to the central issue of ‘which test for which peripersonal space?’, we want to introduce some of the many questions for future research to consider from both an empirical and a theoretical perspective.

Outstanding questions:

1. Can we distinguish purely peripersonal space processes from attentional ones? Do we even need the concept ‘attention’ for near stimuli, if we characterize peripersonal space as a peculiar way of processing stimuli occurring near the body? And, conversely, do we need the concept ‘peripersonal space’ if it is only a matter of attention?

2. Is peripersonal space a matter of temporal immediacy in addition to spatial immediacy? How do the spatial and temporal factors interact?

3. Can there be cognitive penetration of peripersonal perception? At what stage does threat evaluation intervene?

4. Can there be a global whole-body peripersonal representation in addition to local body part-based peripersonal representations? If so, how is it built? What is its relation to egocentric space?

5. To what extent does peripersonal space representation, as a minimal form of the representation of the self in space for interaction, relate to allocentric representation of space for navigation?

6. Did peripersonal space evolve as a tool for survival? What was peripersonal space for? What is it for today? What will it be for tomorrow? Do we still need peripersonal space in a future in which brain–machine interfaces feature heavily?

7. Are there selective deficits of peripersonal space or are they always associated with other spatial deficits? What impact do they have on other abilities?

8. What are the effects of environmental and social factors, known to be relevant to personal space, on peripersonal space?

9. What are the effects of peripersonal space on social interactions? For instance, is emotional contagion or joint action facilitated when the other is within one’s peripersonal space?

10. How are fear and pain related to the defensive function of peripersonal perception?

1.2 Philosophical implications

The computational specificities of the processing of peripersonal space are such that one can legitimately wonder whether peripersonal processing constitutes a sui generis psychological kind of perception. Whether it is the case or not, one can ask whether the general laws of perception, as characterized by our philosophical theories, apply to the special case of the perception of peripersonal space. More specifically, one needs to reassess the relationship between perception, action, emotion, and self-awareness in the highly special context of the immediate surroundings of one’s body. Here we briefly describe the overall directions that some of these discussions might take.

1.2.1 Self-location and body ownership

Where do we locate ourselves? Intuitively, we locate ourselves where our bodies are, and this is also the place that anchors our egocentric space and our peripersonal space. Discussions

on egocentric experiences have emphasized the importance of self-location for perspectival experiences. One might even argue that one cannot be aware of an object as being on the left or the right if one is not aware of one’s own location. Being aware of the object in egocentric terms involves as much information about the perceived object as about the subject that perceives it. It has thus been suggested that the two terms of the relation (the perceived object and the self) are both experienced: when I see the door on the right, my visual content represents that it is on my right (Schwenkler, 2014; Peacocke, 2000). Many, however, have rejected this view (Evans, 1982; Campbell, 2002; Perry, 1993; Schnellenberg, 2007). They argue that there is no need to represent the self, which can remain implicit or unarticulated. A similar question can be raised concerning peripersonal space. Spatial proximity, which plays a key role in the definition of peripersonal space, is a relational property. One may then ask questions about the terms of the relation: are objects perceived close to the self, or only to the body? And is the self, or the body, represented in our peripersonal experiences? Another way to think about this is to ask: does peripersonal perception require some components of selfawareness? Or is it rather the other way around: can peripersonal perception ground some components of self-awareness?

Interestingly, it has been proposed that multisensory integration within peripersonal space is at the basis of body ownership and that this can be altered by manipulating specific features of sensory inputs (Makin et al., 2008; Serino, 2019). For instance, in the rubber hand illusion, tactile stimulation on the participant’s hand synchronously coupled with stimulation of a rubber hand induces an illusionary feeling that the rubber hand is one’s own (see the enfacement illusion, the full body illusion, or the body swap illusion for analagous manipulations related to the face or the whole body). The hypothesis here is that the body that feels as being one’s own is the body that is surrounded by the space processed as being peripersonal. On this view, peripersonal space representation plays a key role in self-consciousness. A crucial question is how such low-level multisensory-motor mechanisms relate to the subjective experience of body owership. A further question is how self-location, body location and the ‘zero point’ from which we perceive the world normally converge. A fruitful path to investigate their mutual relationship is to examine ‘autoscopic phenomena’, such as out-of-body experiences and heautoscopic experiences in patients (Blanke and Arzy, 2005), and in full body illusions (Lenggenhager et al., 2007; Ehrsson, 2007). In these cases, subjects tend to locate themselves toward the location of the body that they experience as owning. Likewise, the extent and shape of peripersonal space are altered along with the induction of illusory ownership toward the location of the illusory body (Serino et al., 2015). This suggests that peripersonal space is tied to self-location and body ownership—that peripersonal space goes with self-location, and that the latter goes with body ownership. This raises interesting questions about cases of heautoscopic patients who have illusions of a second body, which they own, and who report feeling located in both bodies. What does their peripersonal space look like? Measuring peripersonal space appears to provide us with an empirical and conceptual tool for thinking about self-location.

1.2.2 Sensorimotor theories of perception

In what manner does perceptual experience contribute to action? And, conversely, in what manner does action contribute to perceptual experience? The relationship between perceptual experience and action has given rise to many philosophical and empirical debates, which have become more complex since the discovery of dissociations between perception and

action (Milner and Goodale, 1995). For instance, in the ‘hollow face’ illusion, a concave (or hollow) mask of a face appears as a normal convex (or protruding) face, but, if experimental subjects are asked to quickly flick a magnet off the nose (as if it were a small insect), they direct their finger movements to the actual location of the nose in the hollow face. In other words, the content of the illusory visual experience of the face does not correspond to the visually guided movements directed toward the face (Króliczak et al., 2006). Although not without controversy, results such as these have been taken as evidence against sensorimotor theories of perception that claim that action is constitutive of perceptual experience (Noë, 2004; O’Regan, 2011). They can also be taken as an argument against what Clark (2001) calls the assumption of experience-based control, according to which perceptual experience is what guides action. Here we claim that empirical findings on peripersonal space can shed a new light on this debate and, more specifically, that they can challenge a strict functional distinction between perception and action in one’s immediate surroundings.

No matter how complex actions can be and how many sub-goals they can have, all bodily movements unfold in peripersonal space. Typically, while walking, the step that I make is made in the peripersonal space of my foot and, while I move forward, my peripersonal space follows—or, better, it anticipates my body’s future position. Action guidance thus depends on the constant fine-grained monitoring and remapping of peripersonal space while the movement is planned and performed. It is no surprise, then, that peripersonal space is mainly represented in brain regions that are dedicated to action guidance. In addition, the practical knowledge of one’s motor abilities determines whether objects and events are processed as being peripersonal or not. Consider first the case of tool use. One can act on farther objects with a tool than without. This increased motor ability leads to a modification of perceptual processing of the objects that are next to the tool. After tool use, these objects are processed as being peripersonal (e.g. Iriki et al., 1996; Farnè and Làdavas, 2000). Consider now cases in which the motor abilities are reduced. It has been shown that, after ten hours of right arm immobilization, there is a contraction of peripersonal space such that the distance at which an auditory stimulus is able to affect the processing of a tactile stimulus is closer to the body than before (Bassolino et al., 2015). It may thus seem that the relationship between perception and action goes both ways in peripersonal space: peripersonal perception is needed for motor control whereas motor capacities influence peripersonal perception. Can one then defend a peripersonal version of the sensorimotor theory of perception? And, if so, what shape should it take? Although all researchers working on peripersonal space agree on the central role of action, little has been done to precisely articulate this role (for discussion, see de Vignemont, forthcoming).

A first version is to simply describe peripersonal perception exclusively in terms of unconscious sensorimotor processing subserved by the dorsal visual stream. Interestingly, in the hollow face illusion, the face was displayed at fewer than 30 cm from the participants. Hence, even in the space close to us, the content of visual experiences (e.g. convex face) does not guide fine-grained control of action-oriented vision (e.g. hollow face). On this view, there is nothing really special about peripersonal space. We know that there is visuomotor processing, and this is true whether what one sees is close or far. This does not challenge the standard functional distinction between perception and action.

However, this account does not seem to cover the purely perceptual dimension of peripersonal processing. As described earlier, most multisensory tasks, which have become classic measures of peripersonal space, do not involve action at all. Participants are simply asked to either judge or detect a tactile stimulus, while seeing or hearing a stimulus closer or farther from the body. In addition, visual shape recognition is improved in peripersonal

space (Blini et al., 2018). This seems to indicate that there is something special about perceptual experiences in peripersonal space. And because motor abilities influence these perceptual effects, as in the case of tool use, these peripersonal experiences must bear a close relationship to action. One may then propose to apply the classic perception-action model to the perception of peripersonal space. At the unconscious sensorimotor level, peripersonal processing provides the exact parameters about the immediate surroundings required for performing the planned movements. But at the perceptual level, peripersonal experiences also play a role. One may propose, for instance, that peripersonal experiences directly contribute in selecting at the motor level the type of movement to perform, such as arm withdrawal when an obstacle appears next to us.

Here one may reply that there is still nothing unique to peripersonal space. Since Gibson (1979), many have defended the view that we can perceive what have been called ‘affordances’—that is, dispositions or invitations to act, and we can perceive them everywhere (e.g. Chemero, 2003). The notion of affordance, however, is famously ambiguous. One may then use instead Koffka’s (1935) notion of demand character, which actually inspired Gibson. For instance, Koffka describes that you feel that you have to insert the letter in the letterbox when you encounter one. One may assume that you do not experience the pull of such an attractive force when the letterbox is far. In brief, the perception of close space normally presents the subject with actions that she needs to respond to. But again, is this true only of peripersonal space? When I see my friend entering the bar, I can feel that I have to go to greet her. The difference between peripersonal space and far space in their respective relation to action may then be just a matter of degree. One may claim, for instance, that one is more likely to experience demand characters in peripersonal space than in far space. This gradient hypothesis has probably some truth in it, but the direction of the gradient remains to be understood: why is the force more powerful when the object is seen as close? Bufacchi and Iannetti (2018) have recently proposed an interesting conceptualization of peripersonal space as an ‘action field’ or, more properly, as a ‘value field’—that is, as a map of valence for potential actions. Why and how such a field is referenced and develops around the body, and how it is related to attention, remain to be explained.

1.2.3 Affective perception

If there is a clear case in which the objects of one’s experiences have demand characters, then seeing a snake next to one’s foot is such a case. One feels that one has to withdraw one’s foot. But then it raises the question of the relationship between peripersonal perception and evaluation, and about the admissible contents of perception. Can danger be perceptually represented? More specifically, does one visually experience the snake close to one’s foot as being dangerous?

A conservative approach to perception would most probably reply that danger is represented only at a post-perceptual stage. On this view, one visually experiences the shape and the colour of the snake, on the basis of which one forms the belief that there is a snake, which then induces fear, which then motivates protective behaviour. Danger awareness is manifested only later, in cognitive and conative attitudes that are formed on the basis of visual experiences. However, a more liberal approach to perception has recently challenged the conservative approach and argued that the content of visual experiences can also include higher-level properties (Siegel, 2011). On this view, for example, one can visually experience causation. Interestingly, discussions on the admissible contents of perception have been

even more recently generalized to evaluative properties, but so far they have focused on aesthetic and moral properties (Bergqvist and Cowan, 2018). Can one see the gracefulness of a ballet? Can one see the wrongness of a murder? The difficulty in these examples is that assessing such aesthetic and moral properties requires sophisticated evaluative capacities that are grounded in other more or less complex abilities and knowledge. Danger, on the other hand, is a more basic evaluative property, possibly the most basic one from an evolutionary standpoint. To be able to detect danger is the first—although not the only—objective to meet for an organism to survive. Because of the primacy of danger detection, one can easily conceive that it needs to occur very early on, that it does not require many conceptual resources, and that it needs to be in direct connection with action. This provides some intuitive plausibility to the hypothesis that danger can be visually experienced.

This hypothesis seems to find empirical support in the existence of peripersonal perception. For many indeed, peripersonal space is conceived of as a margin of safety, which is encoded in a specific way to elicit protective behaviours as quickly as possible if necessary. Graziano (2009), for instance, claims that prolonged stimulation of regions containing peripersonal neurons in monkeys triggers a range of defensive responses such as eye closure, facial grimacing, head withdrawal, elevation of the shoulder, and movements of the hand to the space beside the head or shoulder. Disinhibition of these same regions (by bicuculline) leads the monkeys to react vividly even for non-threatening stimuli (when seeing a finger gently moving toward the face, for instance), whereas their temporary inhibition (by muscimol) has the opposite effect: monkeys no longer blink or flinch when their body is under real threat. In humans, just presenting stimuli close by (Makin et al., 2009; Serino et al., 2009) or as approaching (Finisguerra et al., 2015) results in the hand modulating the excitability of the cortico-spinal tract so as to implicitly prepare a potential reaction. When fake hands, for which subjects have an illusory sense of ownership, are similarly approached, the corticospinal modulation occurs as rapidly as within 70 milliseconds from vision of the approaching stimulus. What is more interesting is that this time delay is sufficient for the peripersonal processing to distinguish between right and left hands (Makin et al., 2015). This is precisely the kind of fast processing one would need to decide which hand of one’s body is in danger and needs to be withdrawn. In short, having a dedicated sensory mechanism that is specifically tuned to the immediate surroundings of the body, and directly related to the motor system, is a good solution for detecting close threats and for self-defence.

There are, however, many ways that one can interpret how one perceives danger in peripersonal space. We shall here briefly sketch three possible accounts:

1. Sensory account: the sensory content includes the property of danger.

2. Attentional account: attentional priority is given to some low-level properties of the sensory content.

3. Affective account: the sensory content is combined with an affective content.

The first interpretation is simply that the perceptual content includes the property of danger along the properties of shape, colour, movement, and so forth. One way to make sense of this liberal hypothesis is that danger is conceived here as a natural kind. On this view, when you see a snake next to your foot, you visually experience not only the snake but also the danger. The difficulty with such an account, however, is that too many things can be dangerous. Although there are many different kinds of snakes, there is still something like a prototypical sensory look of snakes. By contrast, there is no obvious sensory look of danger.

In brief, there is a multidimensional combination of perceptual features (e.g. shapes, colours, sounds . . .) characterizing threats and it is impossible to find a prototype. Furthermore, what is perceived as dangerous depends on one’s appraisal of the context. Unlike natural kinds, danger is an evaluative property.

One may then be tempted by a more deflationary interpretation in attentional terms. It has been suggested that we have an attentional control system that is similar in many respects to bottom-up attention but that is specifically sensitive to stimuli with affective valence (Vuilleumier, 2015). It occurs at an early sensory stage, as early as 50–80 milliseconds after stimulus presentation. Consequently, it can shape perceptual content by highlighting specific information. This attentional account is fully compatible with a conservative approach to perception. Indeed, giving attentional priority to some elements of the perceptual content is not the same as having perceptual content representing danger as such. However, one may wonder whether this deflationary account suffices to account for our phenomenology. There is a sense indeed in which we can experience danger. In addition, attention can possibly help in prioritizing tasks, but would attention help in interpreting the affective valence within such a short delay?

A possibility then is to propose that we experience danger not at the level of the perceptual content, but at the level of an associated affective content. On this last interpretation, perception can have a dual content, both sensory and affective. One may then talk of affective colouring of perception (Fulkerson, 2020) but this remains relatively metaphorical. A better way to approach this hypothesis might be by considering the case of pain. It is generally accepted that pain has two components, a sensory component that represents the location and the intensity of the noxious event, and an affective component that expresses its unpleasantness. One way to account for this duality in representational terms is known as ‘evaluativism’ (Bain, 2013): pain consists in a somatosensory content that represents bodily damage and that content also represents the damage as being bad. One may then propose a similar model of understanding for the visual experience of the snake next to one’s foot: danger perception consists in visual content that represents a snake and that content also represents the snake as being bad.

We believe that a careful analysis of the results on peripersonal space and its link to selfdefence should shed light on this debate, and, more generally, raise new questions about the admissible contents of perception.

The series of chapters included in the present volume directly or indirectly tap into these (and other) open questions about the nature of our interactions with the environment, for which peripersonal space is a key interface. Without aiming to be exhaustive, we hope that the contributions collected here will provide an updated sketch of the state of the art and provide new insights for future research.

References

Bain, D. (2013). What makes pains unpleasant? Philosophical Studies, 166, S69–S89. Bassolino, M., Finisguerra, A., Canzoneri, E., Serino, A., & Pozzo, T. (2015). Dissociating effect of upper limb non-use and overuse on space and body representations. Neuropsychologia, 70, 385–392.

Bergqvist, A., & Cowan, R. (eds) (2018). Evaluative perception. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Blanke, O., & Arzy, S. (2005). The out-of-body experience: disturbed self-processing at the temporoparietal junction. Neuroscientist, 11(1), 16–24.

Blini, E., Desoche, C., Salemme, R., Kabil, A., Hadj-Bouziane, F., & Farnè, A. (2018). Mind the depth: visual perception of shapes is better in peripersonal space. Psychological Science, 29(11), 1868–1877.

Briscoe, R. (2009). Egocentric spatial representation in action and perception. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 79, 423–460.

Bufacchi, R. J., & Iannetti, G. D. (2018). An action field theory of peripersonal space. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(12), 1076–1090.

Campbell, J. (2002). Reference and consciousness. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chemero, A. (2003). An outline of a theory of affordances. Ecological Psychology, 15(2), 181–195.

Clark, A. (2001). Visual experience and motor action: are the bonds too tight? Philosophical Review, 110(4), 495–519.

de Vignemont, F. (2018). Mind the body: an exploration of bodily self-awareness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. de Vignemont, F. (forthcoming). Peripersonal perception in action. Synthese. di Pellegrino, G., Làdavas, E., & Farnè, A. (1997). Seeing where your hands are. Nature, 388, 730.

Ehrsson, H. H. (2007). The experimental induction of out-of-body experiences. Science, 317(5841), 1048.

Evans, G. (1982). The varieties of reference. Edited by John McDowell. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Farnè, A., & Làdavas, E. (2000). Dynamic size-change of hand peripersonal space following tool use. Neuroreport, 11(8), 1645–1649.

Ferretti, G. (2016). Visual feeling of presence. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 99, 112–136.

Finisguerra, A., Canzoneri, E., Serino, A., Pozzo, T., & Bassolino, M. (2015). Moving sounds within the peripersonal space modulate the motor system. Neuropsychologia, 70, 421–428.

Fulkerson, M. (2020). Emotional perception. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 98(1), 16–30.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston: Boston Mifflin.

Graziano, M. (2009). The intelligent movement machine: an ethological perspective on the primate motor system. New York: Oxford University Press.

Graziano, M. S., & Gross, C. G. (1993). A bimodal map of space: somatosensory receptive fields in the macaque putamen with corresponding visual receptive fields. Experimental Brain Research, 97(1), 96–109.

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. New York: Doubleday & Co.

Hediger, H. (1950). Wild animals in captivity. London: Butterworths Scientific Publications.

Iriki, A., Tanaka, M., & Iwamura, Y. (1996). Coding of modified body schema during tool use by macaque postcentral neurones. Neuroreport, 7(14), 2325–2330.

Koffka, K. (1935). Principles of Gestalt psychology. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Króliczak, G., Heard, P., Goodale, M. A., & Gregory, R. L. (2006). Dissociation of perception and action unmasked by the hollow-face illusion. Brain Research, 1080(1), 9–16.

Leinonen L., & Nyman G. (1979). II. Functional properties of cells in anterolateral part of area 7 associative face area of awake monkeys. Experimental Brain Research, 34, 321–333.

Lenggenhager, B., Tadi, T., Metzinger, T., & Blanke, O. (2007). Video ergo sum: manipulating bodily self-consciousness. Science, 317(5841), 1096–1099.

Makin, T. R., Brozzoli, C., Cardinali, L., Holmes, N. P., & Farnè, A. (2015). Left or right? Rapid visuomotor coding of hand laterality during motor decisions. Cortex, 64, 289–292.

Makin, T. R., Holmes, N. P., Brozzoli, C., Rossetti, Y., & Farnè, A. (2009). Coding of visual space during motor preparation: approaching objects rapidly modulate corticospinal excitability in hand-centered coordinates. Journal of Neuroscience, 29(38), 11841–11851.

Makin, T. R., Holmes, N. P., & Ehrsson, H. H. (2008). On the other hand: dummy hands and peripersonal space. Behavioural Brain Research, 191(1), 1–10.

Maselli, A., & Slater, M. (2014). Sliding perspectives: dissociating ownership from self-location during full body illusions in virtual reality. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 693.

Milner, A. D., & Goodale, M. A. (1995). The visual brain in action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moser, E. I., Kropff, E., & Moser, M.-B. (2008). Place cells, grid cells, and the brain’s spatial representation system. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 31, 69–89.

Noë, A. (2004). Action in perception. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

O’Regan, J. K. (2011). Why red doesn’t sound like a bell: understanding the feel of consciousness. New York: Oxford University Press.

Patané, I., Farnè, A., & Frassinetti, F. (2017). Cooperative tool-use reveals peripersonal and interpersonal spaces are dissociable. Cognition, 166, 13–22.

Peacocke, C. (2000). Being known. New York: Oxford University Press.

Perry, J. (1993). Thought without representation. In his The problem of the essential indexical and other essays, 205–226. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rizzolatti, G., Scandolara, C., Matelli, M., & Gentilucci, M. (1981). Afferent properties of periarcuate neurons in macaque monkeys. II. Visual responses. Behavioural Brain Research, 2(2), 147–163.

Schnellenberg, S. (2007). Action and self-location in perception. Mind, 116, 603–631.

Schwenkler, J. (2014). Vision, self‐location, and the phenomenology of the ‘point of view’. Noûs, 48(1), 137–155.

Serino, A. (2019). Peripersonal space (PPS) as a multisensory interface between the individual and the environment, defining the space of the self. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 99, 138–159.

Serino, A., Annella, L., & Avenanti, A. (2009). Motor properties of peripersonal space in humans. PloS ONE, 4(8), e6582.

Serino, A., Noel, J. P., Galli, G., Canzoneri, E., Marmaroli, P., Lissek, H., & Blanke, O. (2015). Body part-centered and full body-centered peripersonal space representations. Scientific Reports, 5, 18603.

Siegel, S. (2011). The contents of visual experience. New York: Oxford University Press.

Spence, C., Pavani, F., & Driver, J. (2004). Spatial constraints on visual-tactile cross-modal distractor congruency effects. Cognitive, Affective, and Behavioral Neuroscience, 4(2), 148–169.

Vuilleumier, P. (2015). Affective and motivational control of vision. Current opinion in neurology, 28(1), 29–35.