Exploring the Variety of Random Documents with Different Content

Teak, 257

Tecklenborg, Messrs. J. C., 275

Telescopes, 193

Terry’s, Captain C. E., model of the SantaMaria, 182

Thompson, Messrs. J., & Co., 267, 271

Timbers, diagonal, 257

Tonnage measurement, 231

Topgallant sail, 175

Topmasts, 173, 195

Topsails, 83, 284

Trading vessels. SeeMerchant ships

Trafalgar, 254, 262; mistake in signals, 252

Trinity House Corporation, 193; pictures, 227

Tromp, Admiral van, 285

Trondhjem Fjord, ships found on shores of, 114

Trumpeting on ancient ships, 149

Tudor colours, the, 191

Tudor period, development of ships during the, 221

Tuke, Mr. H. S., 5

“Tumblehome,” 168, 244

Tune Viking ship, 117

Tunis, excavations near, 84

Turkish pirates, vessels of, 218

Turner, J. M. W., R.A., pictures by, 5, 259, 285, 289, 300, 323

Tyre and Sidon, kings of, 49

Union flag, the, 241, 242

Union Jack, the, 254

United Service Museum. SeeRoyal United Service Museum

United States coasting trade, 296

Ursula, St., the pilgrimage of, 4, 162

Valdermoor Marsh, Schleswig-Holstein, boat found at, 95

Vasco da Gama, 51, 184

Velde, Willem Van der, 5, 229, 285, 287, 289

Velleius Paterculus, 102

Veneti, ships of the, 90, 93, 105, 106

Venetian warship (thirteenth century), 142

Venetians, English ships purchased from, 190

Venice, St. Mark’s, mosaics in, 130, 144

Venice, ships of, 153, 170

Victoria and Albert Museum. SeeSouth Kensington Museum

Victoria, Queen, 260

Viking ships, 10, 13, 14, 90, 110; arrangements of, 122, 125, 127; sails, 122-124; steering, 156; navigation, 126; the Phœnicians and, 92; connection between and the Mediterranean galleys, 91; discovery of remains of ships, 115-122

Vikings, the, influence of on ships, 156, 285;

harass England and France, 130; burial in ship-shape graves, 113-115

Virginia, 246

Voss, Captain J. C., 302

Vroom, Hendrik C., pictures by, 207, 220

Wanhill, Thomas, of Poole, 324, 326

War-galleys, Greek, 60

Warships and warfare, Norse, 124-125

Watson, Mr. G. L., 328

Waymouth, Mr., 271

West Countrymen, temp. Elizabeth, 202

West Indiaman, 259

West Indies, 214, 258, 259

Whale-boats, 14

Whitby, 303

White Brothers, Messrs., 331

White Ensign, the, 254, 255

White, Mr. H. W., 331

Whitstable, 290

William the Conqueror, 17, 134

Willoughby, Sir Hugh, 191

Wilton, Earl of, 324

Winchelsea, seal of, 149

Winches, 179

Winchester Cathedral, font, 129, 136

Wool trade, Flemish, 154

Woolwich, 227, 246, 250, 321

Wyllie, Mr. W. L., R.A., 5

Wynter, Sir William, 201

Xerxes, 48, 56

Yacht, first, in England, 289; modification of yacht design, 328; sterns of Dutch yachts, 243; the word “yacht,” 320

Yachting, 244, 321 etseq.; international yachting rules, 332

Yarborough, Earl of, 323

Yards, 181

Yarmouth, 129, 304, 307, 315

Yonkers, 225

York Museum, ancient boat in, 100

Yorkshire cobble, 60

Zarebas, 22

Zuyder Zee, 282

PLANS

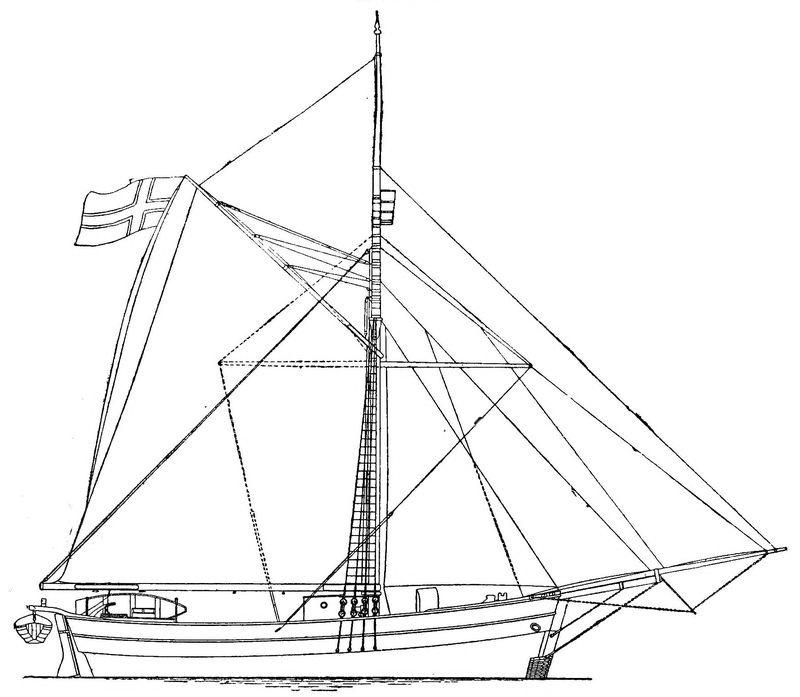

PLAN 1. THE GJOA: SAIL AND RIGGING PLAN.

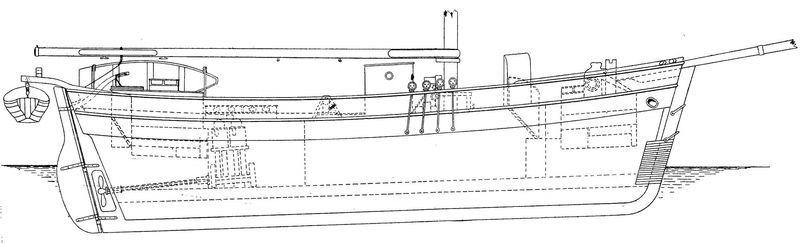

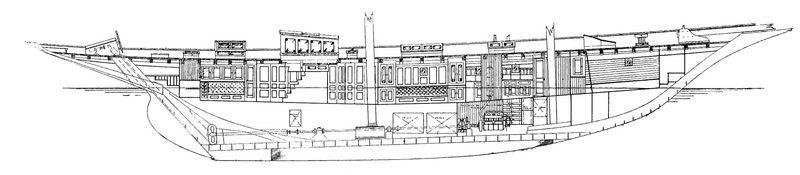

PLAN 2. THE GJOA: LONGITUDINAL SECTION.

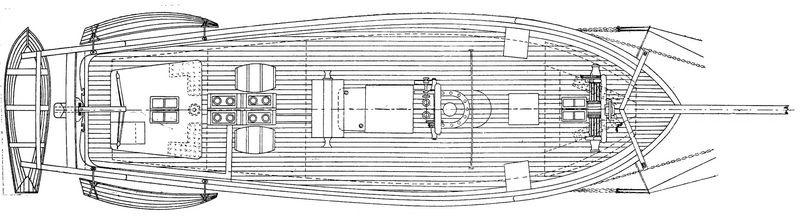

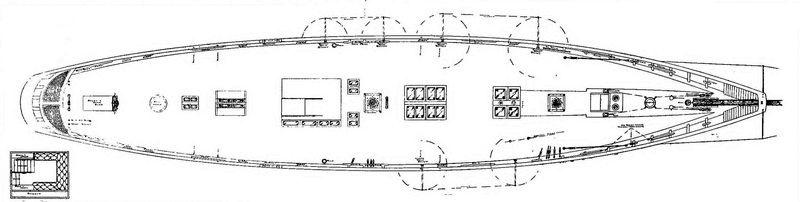

PLAN 3. THE GJOA: DECK PLAN.

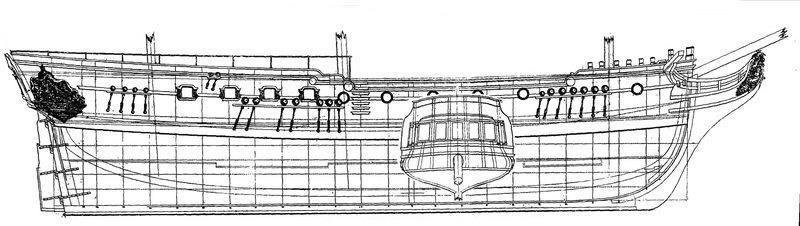

PLAN 4. THE ROYALSOVEREIGN, GEORGE III’S YACHT.

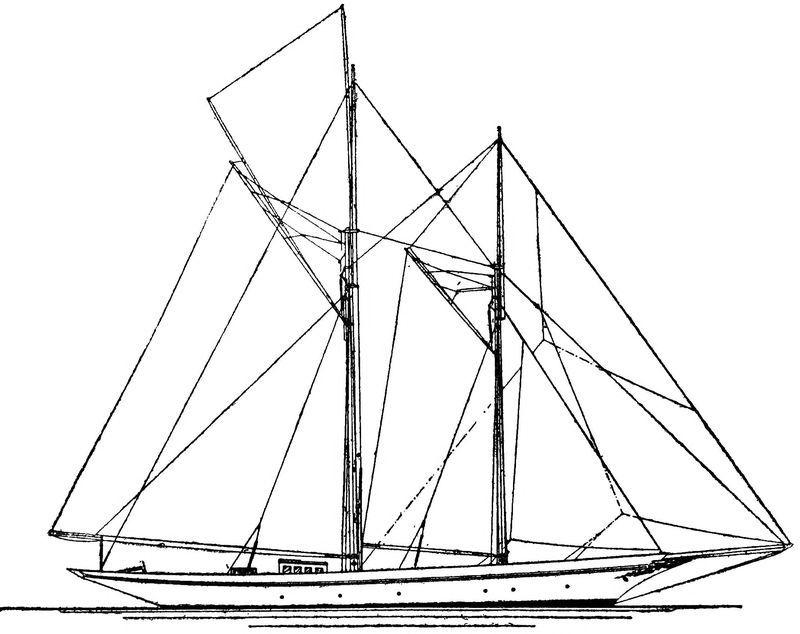

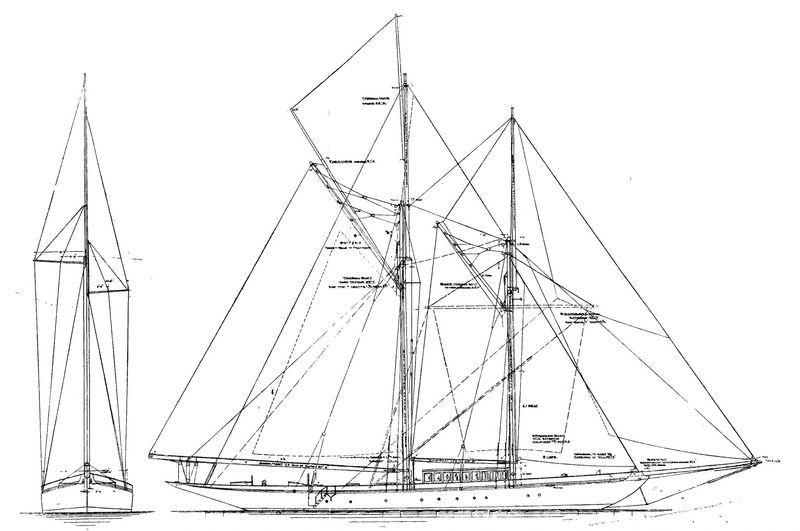

PLAN 5. SCHOONER ELIZABETH: SAIL PLAN.

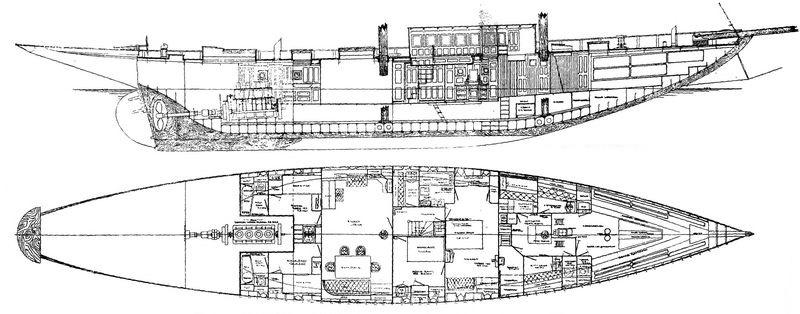

PLAN 6. SCHOONER ELIZABETH: DECK PLAN.

PLAN 7. SCHOONER ELIZABETH: LONGITUDINAL SECTION.

LAN

P

8. SCHOONER PAMPAS: SAIL AND RIGGING PLAN.

PLAN 9. SCHOONER PAMPAS: LONGITUDINAL AND HORIZONTAL SECTIONS.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] “Gizeh and Rifeh,” by W. M. Flinders Petrie, London, 1907. (Double volume.)

[2] “A Guide to the Third and Fourth Egyptian Rooms, British Museum,” London, 1904.

[3] “The Jesup North Pacific Expedition,” vol. vi. part ii., “The Koryak”; see pp. 534-538. By W. Jochelson, New York, 1908.

[4] See “The Egypt Exploration Fund: Archæological Report, 1906-1907.”

[5] “The Tomb of Hatshopsitu,” p. 30, by Edouard Naville, London, 1906.

[6] “Egypt Exploration Fund: The Temple of Deir-el-Bahari,” by Edouard Naville.

[7] “The Fleet of an Egyptian Queen,” by Dr. Johannes Duemichen. Leipzig, 1868.

[8] “Egypt Exploration Fund: The Temple of Deir-el-Bahari,” p. 16.

[9] “The Dawn of Civilisation Egypt,” by Professor Maspero, London, 1894.

[10] For some valuable matter regarding Greek and Roman ships I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to the following, especially the first two of these:

“Ancient Ships,” by Cecil Torr, Cambridge, 1894.

“Dictionnaire des Antiquités Grecques et Romanes,” by Ch. Daremberg (article under “Navis,” by Cecil Torr), Paris, 1905.

“A Companion to Greek Studies,” by L. Whibley, Cambridge, 1905.

(See article on “Ships,” by A. B. Cook, p. 475 etseq.)

[11] “The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation,” by Richard Hakluyt. Preface to

the second edition.

[12] Even still more wonderful and more to the point, as having sailed to the entrance of the Mediterranean, is the passage of the Columbia II., a tiny ship only 19 feet long with 6 feet beam. Navigated solely by Capt. Eisenbram, she sailed from Boston, U.S.A., to Gibraltar, encountering severe weather on the way, in 100 days. (See the Times newspaper of November 21, 1903.)

[13] An illustration of this will be found in “Pompeji in Leben und Kunst,” by August Mau, Leipzig, 1908.

[14] A model of this ship is to be seen in the Louvre. See “Musée Rétrospectif de la Classe 33. Matériel de la Navigation de Commerce à l’Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900, à Paris. Rapport du Comité d’Installation.”

[15] “Ancient Ships,” by Cecil Torr, Cambridge, 1894.

[16] “Lazari Bayfii annotationes ... de re navali.” Paris, 1536.

[17] See “Caligula’s Galleys in the Lake of Nemi,” by St. Clair Baddeley, article in the Nineteenth Century and After, March, 1909; also “Le Navi Romane del Lago di Nemi,” by V. Malfatti, Rome, 1905, which gives an interesting account, with illustrations, of the finding of these galleys, as well as an excellent plan of one of the ships of Caligula as far as she has been explored. She has a rounded stern and pointed bow. An ingenious pictorial effort is made to reconstruct the galley afresh. The book contains photographs of the floats, showing the shape of the boat, and of some of the chief relics recovered in 1895.

[18] “Life of Caligula,” xxxvii.

[19] See p. 245.

[20] Acts xxvii.

[21] “Un Catalogue Figuré de la Batellerie Gréco-Romaine La Mosaïque d’Althiburus,” par P. Gauckler, in “Monuments et Mémoires.” Tome douzième, Paris, 1905.

[22] “De Bello Civili,” iii. 29.

[23] Sagas—or “says,” narratives—are records of the leading events of the lives of great Norsemen and their families. Hundreds of these records exist, though many of them are purely mythical. They date from a period not earlier than the sixth century of our era, but the downward limit cannot be exactly fixed. Not unnaturally, in such national epics as centre round the

kings of Sweden, Norway and Denmark, we find references to sailing ships both frequent and detailed.

[24] “This northern civilisation,” says Du Chaillu, in his account of these people (“The Viking Age,” vol. i. p. 4, London, 1889) “was peculiar to itself, having nothing in common with the Roman world, Rome knew nothing of these people till they began to frequent the coasts of her North Sea provinces, in the days of Tacitus, and after his time, the Mediterranean.... The manly civilisation the Northmen possessed was their own ... it seems to have advanced north from about the shores of the Black Sea, and ... many northern customs were like those of the ancient Greeks.”

[25] Cæsar, “De Bello Gallico,” iii. chap. 13: “Pro loci natura, pro vi tempestatum, illis essent aptiora et accommodatoria.”

[26] “Notes on Shipbuilding and Nautical Terms of Old in the North,” a paper read before the Viking Society for Northern Research by Eiríkr Magnússon. London, 1906.

[27] It was presented to the Hull Museum while this book was in the press, June 1909.

[28] “A Prehistoric Boat,” a lecture by Rev. D. Cary-Elwes. Northampton, 1903.

[29] Tacitus, “Hist.” v. 23.

[30] “Annual Report of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution: Prehistoric Naval Architecture of the North of Europe,” by George H. Boehmer. Washington, 1892. (See p. 527.)

[31] Cæsar, “De Bello Civili,” book i. chap. 54: “Imperat militibus Cæsar, ut naves faciant, cujus generis eum superioribus annis usus Britanniæ docuerat. Carinæ primum ac statumina ex levi materia fiebant: reliquum corpus navium viminibus contextum, coriis integebatur.”

[32] Cæsar, “De Bello Gallico,” III. xiii.: “Namque ipsorum naves ad hunc modum factæ armatæque erant: carinæ aliquanto planiores quam nostrarum navium, quo facilius vada ac decessum æstus excipere possent: proræ admodum erectæ atque item puppes ad magnitudinem fluctuum tempestatumque accommodatæ; naves totæ factæ ex robore ad quamvis vim et contumeliam perferendam: transtra pedalibus in altitudinem trabibus confixa clavis ferreis digiti pollicis crassitudine; ancoræ pro funibus ferreis catenis revinctæ; pelles pro velis alutæque tenuiter confectæ, [hæc] sive propter lini inopiam atque ejus

usus inscientiam, sive eo, quod est magis verisimile, quod tantas tempestates Oceani tantosque impetus ventorum sustineri ac tanta onera navium regi velis non satis commode posse arbitrabantur.”

Mr. St. George Stock in his edition (Cæsar, “De Bello Gallico,” books i.-vii., edited by St. George Stock, Oxford, 1898) understands “transtra” not to mean the rowing benches but crossbeams or decks.

[33] The Veneti lived in the extreme north-west corner of France, and have left behind the name of the town Vannes, facing the Bay of Biscay, and opposite Belle Isle.

The Greeks and Romans having learned their seamanship on the practically tideless waters of the Mediterranean must have been appalled by the ebb and flow of the Northern Seas. Cæsar was ignorant of the moon’s relation to tides until taught by bitter experience. He was taught only by the damage done to his ships in Britain. (“De Bello Gallico,” iv. 29). The Veneti, however, understood all these things, for Cæsar remarks, “quod et naves habent Veneti plurimas, quibus in Britanniam navigare consuerunt, et scientia atque usu nauticarum rerum reliquos antecedunt.” Further on he refers to the Bay of Biscay as the great, boisterous, open sea, “in magno impetu maris atque aperto.” (“De Bello Gallico,” book iii. chap. 8). It is to Pytheas (referred to previously) that Plutarch gives the credit of having detected the influence of the moon on tides.

The reader wishing to pursue the subject is referred to “Cæsar’s Conquest of Gaul,” by T. Rice Holmes. London, 1899.

[34] Tacitus’ “Annals,” ii. 23 and 6. “Mille naves sufficere visæ properatæque, aliæ breves, angusta puppi proraque et lato utero, quo facilius fluctus tolerarent, quædam planæ carinis ut sine noxa siderent: plures adpositis utrimque gubernaculis, converso ut repente remigio hinc vel illinc adpellerent: multæ pontibus stratæ, super quas tormenta veherentur ... velis habiles, citæ remis augebantur alacritate militum in speciem ac terrorem” (ii. 6).

Mr. Henry Furneaux in his edition of the “Annals” (Oxford 1896), commenting on “pontibus,” thinks these formed a partial deck across the midships which would have the appearance of a bridge when viewed from bow or stern.

[35] Roman ships were sometimes built in 60 days, while there is a record of 220 having been built in 45 days.

[36] Du Chaillu points out the interesting fact that it was not until after the Danes and Norwegians had succeeded in planting themselves in this country that the inhabitants of our land exhibited that love of the sea and ships which has been our greatest national characteristic for so many centuries. Certainly when the Romans invaded Britain our forefathers had no fleet with which to oppose them.

[37] Tacitus, “De situ, moribus et populis Germaniæ libellus,” chap. 44: “Suionum hinc civitates, ipsæ in Oceano, præter viros armaque classibus valent. Forma navium eo differt quod utrinque prora paratam semper appulsui frontem agit: nec velis ministrantur, nec remos in ordinem lateribus adjungunt: solutum, ut in quibusdam fluminum, et mutabile, ut res poscit, hinc vel illinc remigium.”

[38] “Norges Oldtid,” by Gabriel Gustafson. Kristiania, 1906.

[39] “Notes on Shipbuilding and Nautical Terms of Old in the North,” by Eiríkr Magnússon. A paper read before the Viking Club for Northern Research. London, 1906.

[40] Du Chaillu (“The Viking Age,” vide supra) attributes these ship-form graves to the Iron Age, and remarks that similar monuments have been found in England and Scotland. “One of the most interesting,” he adds, “is that where the rowers’ seats are marked, and even a stone placed in the position of the mast” (p. 309, vol. i.). This is reproduced in Fig. 27.

[41] For further details as to the Viking mode of burial, the reader is referred to vol. i. chap. xix. of Du Chaillu’s “The Viking Age.”

[42] See “The Old Northern Runic Monuments of Scandinavia and England,” vol. i., by George Stephens, F.S.A., London, 1866.

[43] “Ancient and Modern Ships,” part i., “Wooden Sailing Ships,” p. 60, by Sir George C. V. Holmes, K.C.V.O., C.B., London, 1900.

[44] Magnússon’s “Notes on Shipbuilding,” &c., utsupra, p. 50.

[45] Reproduced on p. 126, fig. 536, of Prof. Gustafson’s “Norges Oldtid.”

[46] Evidently the early Europeans did not merely make rash voyages, trusting entirely to good luck to reach their port. It is quite clear that they had given serious study to seamanship by the early part of the fifth century, for when Lupus and German, two Gallic prelates, crossed the Channel to Britain in the year 429

A.D., they encountered very bad weather, and Constantius adds that St. German poured oil on the waves. The latter’s earlier days having been spent in Gaul, in Rome and as duke over a wide district, he had evidently picked up this item of seamanship from the mariners of the southern shores. (See Canon Bright’s “Chapters of Early English Church History,” Oxford, 1897, p. 19 and notes.)

[47] “Navi Venete da codici Marini e dipinti,” by Cesare Augusto Levi, Venice, 1892.

[48] See the ship in the seal of Dam, Fig. 40.

[49] “Social England,” edited by H. D. Traill, D.C.L., and J. S. Mann, M.A., London, 1901. See article by W. Laird Clowes, vol. i. p. 589.

[50] See “Handbook to the Coins of Great Britain and Ireland in the British Museum,” London, 1899.

The Edward III. coin will be found to be reproduced on all the publications of the Navy Records Society.

[51] Ballingers were long, low vessels for oars and sails, introduced in the fourteenth century by Biscayan builders.

[52] See “Gentile da Fabriano,” p. 134, by Arduino Colasanti, Bergamo 1909.

[53] See Fig. 37 in “Navi Venete.”

[54] See “The Life and Works of Vittorio Carpaccio,” by Pompeo Molmenti and Gustav Ludwig, London, 1907.

[55] “Hans Memling,” p. 46, by W. H. James Weale, London, 1901.

[56] Reproduced in “Navi Venete,” Fig. 96.

[57] See “Musée Rétrospectif de la Classe 33,” &c.

[58] This MS. has been carefully reproduced in “Monuments et Mémoires,” par Georges Perrot and Robert de la Steyrie. Tome onzième. See article on “Un Manuscrit de la Bibliothèque de Philippe le bon à Saint-Pétersbourg,” Paris, 1904.

[59] See “Ancient and Modern Ships,” p. 74, by Sir G. C. V. Holmes, London, 1900.

[60] “Naval Accounts and Inventories of the Reign of Henry VII.,” edited by M. Oppenheim, Navy Records Society, 1896. I wish to

acknowledge my indebtedness to this valuable volume for much information in connection with Henry VII.’s ships.

[61] In the Middle Ages it was the custom to refer to the masts of a ship possessing four in the manner as above. The aftermost was the bonaventure.

[62] “On the Spanish Main,” by John Masefield, London, 1906. See chap, xvi., on “Ships and Rigs.”

[63] See article by W. Laird Clowes in vol. ii. of Traill and Mann’s “Social England,” London, 1901.

[64] See “Christopher Columbus and the New World of his Discovery,” by Filson Young, London, 1906. The reader is especially advised to study an admirable article in vol. ii. of this work on “The Navigation of Columbus’s First Voyage,” by the Earl of Dunraven.

[65] See “Ancient and Modern Ships,” by Sir G. C. V. Holmes.

[66] London, 1830.

[67] “Navi Venete.”

[68] See “Letters and Papers relating to the War with France, 1512-1513,” by Alfred Spont, Navy Records Society, 1897.

[69] “A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy and of Merchant Shipping in Relation to the Navy,” vol. i., 1509-1660, by M. Oppenheim, London, 1896.

[70] “On the Spanish Main,” by John Masefield, chap. xvi., on “Ships and Rigs.”

[71] Reprinted in “The Naval Miscellany,” edited by Professor Sir J. K. Laughton, M.A., R.N., vol. i., Navy Records Society, 1902.

[72] This was the Missa Sicca (Messe Sèche), the “Messe Navale,” or “Missa Nautica,” in which no consecration took place.

[73] See “Companion to English History (Middle Ages),” edited by F. P. Barnard, M.A., F.S.A., Oxford, 1902; article on “Shipping,” by M. Oppenheim.

[74] Manwayring, who fought in the English Fleet against the Armada, states that a “cross-sail” (square-rigged) ship in a sea cannot sail nearer than six points, unless there be tide or current setting her to windward.

[75] See chap. iii. p. 78. This revival in Edward VI.’s time of lead sheathing was copied from the contemporary custom among Spanish ships.

[76] P. 16.

[77] “Judicious and Select Essayes,” p. 33.

[78] See article on “Public Health,” by Charles Creighton, on p. 763, vol. i., of Traill and Mann’s “Social England.”

[79] “Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson,” edited by M. Oppenheim, Navy Records Society. See vol. ii. p. 235.

[80] Edited by Professor Sir J. K. Laughton, M.A., R.N., Navy Records Society, 1894.

[81] Given on p. 274 of “State Papers relating to the Defeat of the Spanish Armada,” vide supra.

[82] Ibid. p. 82.

[83] See “The British Mercantile Marine: a Short Historical Review,” by Edward Blackmore, London, 1897.

[84] “Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson,” edited by M. Oppenheim, Navy Records Society, 1902. See vol. ii. p. 328.

[85] “Papers relating to the Navy during the Spanish War, 15851587,” edited by J. S. Corbett, LL.M., Navy Records Society, 1898. I wish to express my indebtedness to this volume, and to Mr. Oppenheim’s “Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson,” for much matter in regard to the different types of Elizabethan ships.

[86] The reader who desires fuller information on the subject is referred to an interesting article “The Lost Tapestries of the House of Lords,” in Harper’s Monthly Magazine, April, 1907, from the pen of Mr. Edmund Gosse.

[87] These nettings were at first made of metal chain, but in the time of Elizabeth they were of rope.

[88] The illustration is taken from a print in the British Museum made by an artist who was born in 1620.

[89] It is interesting to note that in the year 1903 some Armada relics, consisting of a bronze breach loader, found fully charged, and a pair of bronze compasses were recovered from the wreck of the Spanish galleon Florencia, in Tobermory Bay, Isle of Mull. She had formed one of the Spanish fleet which fled up the North Sea from the English Channel, round the north of Scotland to the

west coast, where in August of 1588 this 900-ton ship was blown up.

[90] See “Naval Tracts of Sir William Monson,” vol. ii. p. 318 et seq.

[91] See vol. x., p. 158, of Maclehose’s edition of 1903.

[92] This map will be found reproduced at p. 171, vol. ii., of Maclehose’s edition of Hakluyt, published in 1903.

[93] That is to say he not merely covers with the canvas-cloth the whole length of the deck to prevent boarding, but the nettings would also be drawn over the waist to catch the falling wreckage of spars. (See Fig. 53.)

[94] Dexterous.

[95] “Boord and boord”—i.e., when two ships touch each other.

Manwayring advises against boarding the enemy at the quarter, which is the worst place, because it is high. The best place for entering was at the bows, but the best point for the play of the guns was to come up to her “athwart her hawes” i.e., across her bows. By this means you could then bring all your broadside to play upon her, while all the time the enemy could only use her chase and prow pieces.

[96] I am far from convinced, however, that the drawing is in this respect correct. Edward Hayward in his book on “The Sizes and Lengths of Riggings for all His Majesties Ships and Frigates,” printed in London in 1660, only twenty-three years after the Sovereign of the Seas was launched, makes no mention whatever of either her royals or of any mast or spar above topgallant, although he mentions in detail the masts and yards and rigging and sails other than royals. He does mention, however, that the Sovereign carried a bonnet to be laced on to her spritsail. It is possible, however, that the royals were added in 1684, when she was rebuilt.

[97] See Appendix II. of “Ancient and Modern Ships,” by Sir G. C. V. Holmes.

[98] See “A History of the Administration of the Royal Navy and of Merchant Shipping in Relation to the Navy,” &c., by M. Oppenheim, p. 268.

[99] Edited by J. R. Tanner, M.A., Navy Records Society, 1896, from the MSS. in the Pepysian Library.

[100] I am indebted for many important details of this reign to “A Descriptive Catalogue of the Naval MSS. in the Pepysian Library at Magdalene, Cambridge,” edited by Dr. J. R. Tanner, Navy Records Society, 1903.

[101] “Judicious and Select Essayes and Observations,” p. 29.

[102] But see Chapter IX. of this volume.

[103] “Ancient and Modern Ships,” pp. 111, 112.

[104] “The Royal Navy,” by W. Laird Clowes, London, 1898. See p. 25, vol. ii.

[105] “Life of Captain Stephen Martin, 1666-1740,” edited by Clement R. Markham, C.B., F.R.S., Navy Records Society, 1895. See p. 24.

[106] “Old Sea Wings, Ways and Words in the Days of Oak and Hemp,” by Robert C. Leslie, London, 1890.

[107] For the purpose of not showing too prominently the blood shed in casualties.

[108] For further matter regarding the American frigates, the reader is referred to “American Merchant Ships and Sailors,” by William J. Abbot, New York, 1902.

[109] See pp. 36-37.

[110] For some of the facts in connection with this period I am indebted to articles by the late Sir W. Laird Clowes in his monumental history of “The Royal Navy,” and in Traill and Mann’s “Social England.”

[111] “The Navy Sixty Years Ago,” by Admiral Moresby, in the NationalReview of December 1908.

[112] See an interesting article by Mr. Frank T. Bullen on “DeepSea Sailing” in the Yachting Monthly of August 1907, to which I am indebted for some details of information.

[113] See “La Navigation Commerciale au XIXe Siècle,” by Ambroise Colin, Paris, 1901.

[114] “Ancient and Modern Ships,” part ii., “The Era of Steam, Iron and Steel,” p. 24, by Sir George C. V. Holmes, K.C.V.O., C.B., London, 1906.

[115] “The British Mercantile Marine,” by Edward Blackmore, London, 1897.

[116] In connection with this chapter, I wish to acknowledge my indebtedness to certain matter contained in the following:

“Architectura Navalis Mercatoria,” by F. H. Chapman, Holmiæ, 1768; “The History of Yachting,” by Arthur H. Clark, New York, 1904; “Yachting,” by Sir Edward Sullivan, Bart., Lord Brassey, &c., 2 vols., London, 1894-95; “Mast and Sail in Europe and Asia,” by H. Warington Smyth, London, 1906; “Lloyd’s Almanac”; “Lloyd’s Yacht Register,” &c.; the Yachtsman; the Yachting World; the Yachting Monthly.

[117] “Architectura Navalis Mercatoria,” by F. H. Chapman, Holmiæ, 1768.

[118] This vessel was until recently in Portsmouth Harbour.

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The page number in the caption of Plate illustrations, a typesetter indicator, has been removed. These Plates are indicated by the words ‘to face’ in the List of Illustrations.

Many illustrations have been moved to be closer to the related text.

All occurrences of ‘Memlinc’ have been changed to ‘Memling’.

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

Some hyphens in words have been silently removed, some added, when a predominant preference was found in the original book.

Except for those changes noted below, all misspellings in the text, and inconsistent or archaic usage, have been retained.

Pg 37: ‘again been stretched’ replaced by ‘again being stretched’.

Pg 94: ‘ancient Northener’ replaced by ‘ancient Northerner’.

Pg 94: ‘found that be could’ replaced by ‘found that he could’.

Pg 201: ‘and at at any rate’ replaced by ‘and at any rate’.

Pg 276: ‘on the i en a single’ replaced by ‘on the mizzen a single’.

Pg 276: ‘continu till they’ replaced by ‘continued till they’.

Pg 328: ‘nas been made’ replaced by ‘has been made’.

Pg 339: ‘postliminis reversis’ replaced by ‘postliminio reversis’.

Pg 340: ‘Darenburg, Ch.’ replaced by ‘Daremberg, Ch.’.

Pg 347: ‘Capelle, Jan’ replaced by ‘Cappelle, Jan’.

Pg 352: ‘Mainwayring, Sir’ replaced by ‘Manwayring, Sir’.

Pg 358: ‘Vahalla’ replaced by ‘Valhalla’.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SAILING SHIPS ***

Updated editions will replace the previous one—the old editions will be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG™ concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for an eBook, except by following the terms of the trademark license, including paying royalties for use of the Project Gutenberg trademark. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the trademark license is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. Project Gutenberg eBooks may be modified and printed and given away—you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE