The Trials of Allegiance

Treason, Juries, and the American Revolution z

CARLTON F.W. LARSON

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Carlton F.W. Larson 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–093274–9

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

To my parents, Carl and Esther Larson

1. Treason in Colonial Pennsylvania 11

The Adoption of English Treason Law 13

Pennsylvania’s Earliest Treason Cases 18

The Outbreak of War 19

The Disputes with Virginia and Connecticut 23

2. Resistance and Treason, 1765–1775 30

Justifying Resistance 31

A Jury of One’s Peers 34

Identifying the Real Traitors 37

3. Treason against America, 1775–1776 42

The War’s First Treason Charges 45

The Second Round of Treason Charges 49 County Committees of Safety 51

Denunciation of Enemies 55

The British Legal Response to the Rebels 57 Independence 58

4. From Independence to Invasion, 1776–1778 61

The Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention and the Treason Ordinance 62

The Council of Safety and the County Committees 65 Enactment of a Treason Statute 69

The Case of James Molesworth and the Scope of Military Jurisdiction 73

The Test Act 75

Reopening the Courts 76

The Exiles to Virginia 78

The Fall of Philadelphia and Military Trials 85

5. The Winding Path to the Courthouse, 1778 91

Prosecutions in the County Courts 92

The Attainder Statute and Property Forfeitures 96

Chief Justice Thomas McKean and the Reopening of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court 100

The Special Commission for Bedford County 107

The Return to Philadelphia 108

Hiring Prosecutors and Court Employees 113

Trial by Jury in Chester County 117

6. The Philadelphia Treason Trials, 1778–1779: Forming the Jury 122

The Grand Jurors 124

Trial-Juror Selection: The Panel and Challenges 130

Trial-Juror Demographics 135

Trial-Juror Political Activity 146

7. The Philadelphia Treason Trials, 1778–1779: Trial and Deliberation 150

Defendant Demographics and Political Activity 152

Defense Counsel 156

Charges and Defenses 157

Trial Witnesses 160

Evidentiary Objections 162

Jury Deliberations 163

The Death Penalty 165

8. Resentment and Betrayal, 1779–1781 177

The Newspaper Debates over the Franks Trial 177

The Trial of Samuel Rowland Fisher 181

Fort Wilson 185

Modifications to Pennsylvania’s Treason Law 189

The Battle over Detentions 192

Misprision of Treason Cases before the Justices of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court 194

Benedict Arnold 197

The Aftermath: The Executions of David Dawson and Ralph Morden 201

The Berks County Tax Revolt 206

The Trials of Justin McCarty and Samuel Chapman 208

9. Peace, the Constitution, and Rebellion, 1781–1800 214

Treason Prosecutions after Yorktown 215

Treason Cases: Summary Data 217

The Escaping-Prisoners Cases 220

The Returning Loyalists 223

The Continuing Threat of Internal Dismemberment 226

Treason and the United States Constitution 229

The Status of State Treason Law 233

The Whiskey Rebellion 235

Fries’s Rebellion 243

Appendix 1: Juror Assignments: Philadelphia Treason Trials, 1778–1779

Appendix 2: Jury Trials for High Treason in Pennsylvania during the American Revolution

Appendix 3: Jury Trials for High Treason, United States Circuit Court for the District of Pennsylvania, 1795–1800, Held at City Hall in Philadelphia

Acknowledgments

This project originated in the mid-1990s, as my undergraduate thesis at Harvard College. I have accumulated numerous debts along the way, which I am grateful finally to acknowledge.

At Harvard, David J. Hancock, now of the University of Michigan, introduced me to the intellectual dimensions of the American Revolution and helped craft my initial thesis proposal. Mark Peterson, now of Yale University, graciously took me on as an orphan advisee when Professor Hancock departed for Michigan, and carefully guided my writing over the course of a year. A research grant from the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History supported my visits to archives and courthouses throughout Pennsylvania. Bernard Bailyn provided valuable encouragement along the way. Paul Mapp and the late Mark Kishlansky were incisive readers. I am also grateful to Charles Donahue for a splendid introduction to the field of English legal history.

At Yale Law School, Akhil Reed Amar encouraged my research into treason, juries, and the remarkable career of James Wilson. The late Morris Cohen provided me with a solid grounding in research methods in American legal history, and John Langbein taught me the intricacies of eighteenth-century criminal procedure.

At UC Davis, I have benefitted from the assistance of talented and diligent research assistants, including Amber Dodge, Rachel Thyre Anderson, and Jasmine Tzeng. Mark Ramzy applied his quantitative skills to a statistical analysis of the Philadelphia tax records. Faculty support assistants Jennifer Angeles, Linda Cooper, and Liliana Moore helped with numerous administrative tasks. Neil Willits of the UC Davis Statistical Laboratory helped me make sense of the juror records. The staff of the Mabie Law Library at the UC Davis School of Law, especially Peg Durkin, have tracked down endless requests for obscure sources. In the dean’s office, the late Rex Perschbacher, Kevin Johnson, Vikram Amar, Madhavi Sunder, and Afra Afsharipour have supported this project with summer research funding and have been patient when my overly optimistic estimates of its completion date failed to materialize. I am also indebted to the Office of Research at UC Davis, which provided funding

Acknowledgments

for many of my archival visits, access to databases, and permissions for the book’s illustrations.

The archival staffs at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Pennsylvania State Archives, the American Philosophical Society, the Philadelphia City Archives, and the Friends Historical Library at Swarthmore College were especially helpful for this project. Stephen Corson and Bradley Kerr provided significant information relating to their ancestors, who participated in the treason trials.

Several of the chapters were initially presented at faculty workshops at the Dedman School of Law at Southern Methodist University, at William & Mary Law School, and at the annual meetings of the American Society for Legal History in Ottawa and Miami and the Law & Society Association in Montreal and Honolulu.

An early version of Chapters 6 and 7 was published as “The Revolutionary American Jury: A Case Study of the 1778–1779 Philadelphia Treason Trials,” SMU L. Rev. 61 (2008): 1441–1524. Occasional paragraphs are drawn from “The Forgotten Constitutional Law of Treason and the Enemy Combatant Problem,” U. Penn. L. Rev. 154 (2006): 863–926. Fragments of Chapters 5 and 7 also appeared in “The 1778–1779 Chester and Philadelphia Treason Trials: The Supreme Court as Trial Court,” in The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania: Life and Law in the Commonwealth, 1684–2017, ed. John J. Hare (University Park: Penn. St. Univ. Press, 2018), 315–324.

I am especially grateful to Gordon Wood, who encouraged me to turn the material in the SMU Law Review article into a book.

Mark Box, the late Floyd Feeney, Sally Hadden, Margaret Johns, David Konig, Peter Lee, Donna Shestowsky, Robert Spoo, Bruce Smith, and William Wiecek provided helpful comments on drafts of individual chapters. Gerard Magliocca, Carl Larson, Esther Larson, and Elaine Lau read the entire manuscript and saved me from numerous errors. Amanda Tyler and Daniel Sharfstein provided insights into the publishing world. Judge Michael Daly Hawkins of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, for whom I had the honor to serve as a law clerk, has been a consistent source of encouragement. We share an admiration of James Wilson, whose footprints can be found throughout this book.

At the Strothman Agency, Wendy Strothman helped me sharpen my arguments and found a good home for the manuscript with Oxford University Press. Lauren MacLeod assisted with numerous details. I am also deeply grateful to my Oxford University Press editor, David McBride, editorial assistant Holly Mitchell, the Press’s anonymous reviewers, and copyeditor Leslie Safford.

My wife, Elaine Lau, in addition to providing helpful insights on the manuscript, has been an endless source of inspiration and encouragement. My children,

Acknowledgments

Carina and Elliot, although too young to understand the issues in this book, have taught me much about loyalty and allegiance. Their happy shouts of “Daddy!” when I come home from the office are the greatest joys of my life.

Finally, I am grateful to my parents, Carl and Esther Larson, who have fostered my love of history from an early age. Our house in western North Dakota was filled with thousands of books of history, ranging from the ancient world to the history of the automobile. When I was six years old, our family spent the summer in Massachusetts. Seeing landmarks such as Faneuil Hall, the Freedom Trail, and the Concord Bridge left an indelible impression and a fascination with the American Revolution that has endured to this day. Through their own work, my parents demonstrated the importance of doing “hard research” and getting the story exactly right. This book is dedicated to them, with affection and love.

Introduction

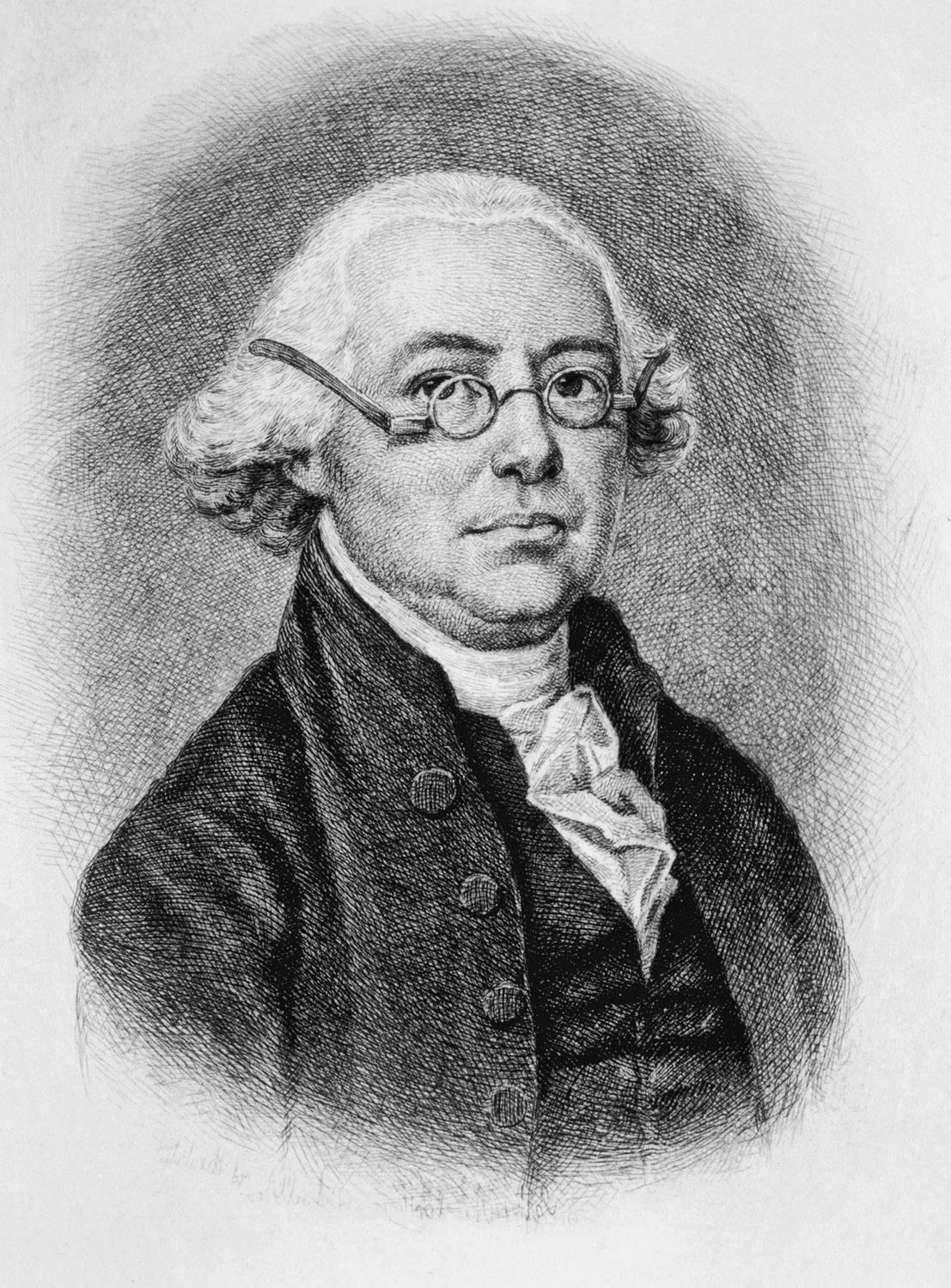

When dawn broke on the morning of October 4, 1779, in the fifth year of the American War for Independence, James Wilson of Philadelphia was not expecting to face combat. If he had stood on ceremony, he could have called himself Colonel Wilson (he was formally a colonel in the Cumberland County militia), but his countrymen would probably have rolled their eyes. A scholarly, bespectacled lawyer with no obvious martial abilities, Wilson had yet to draw his sword in battle (Figure I.1).

But he had contributed notably to the cause of American independence with an even more powerful weapon—his pen. After emigrating from his native Scotland in his twenties, Wilson had become a leader of the Pennsylvania bar and the author of an influential pamphlet advocating the cause of the American colonies.1 Elected as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress, Wilson had proudly signed the Declaration of Independence at the Pennsylvania State House, the building that future generations would enshrine as Independence Hall.

Wilson’s conduct had thus made him one of the most prominent American traitors to Great Britain and a rich prize for any British military unit that managed to capture him. When Wilson heard the beat of the drums on October 4, 1779, he suspected that the armed men marching through the streets of Philadelphia might be on his trail. Hunkered down in his elegant brick mansion at the corner of Third and Walnut Streets, just a few blocks from where he had signed the Declaration of Independence, Wilson and a group of wealthy friends were prepared to resist, to the death if necessary.

Soon the armed men reached Wilson’s house, and the battle, one of the war’s rare instances of urban combat, erupted in full. The attackers began shooting at the windows of the house and attempting to force open the front door. From the second floor, Wilson and his friends returned fire. The battle might have continued much longer, but a Pennsylvania cavalry force arrived and quickly ended

Credit: Shutterstock.

the fighting. The battle of “Fort Wilson,” as it later came to be called, claimed at least six lives and injured many more. Wilson proved to be one of the lucky ones; he survived and later became a primary architect of the United States Constitution and one of President George Washington’s first appointees to the United States Supreme Court.

The armed and bitterly angry men attacking the house detested James Wilson for his political beliefs and for his actions at the Pennsylvania State House. But despite what one might expect, they were not British soldiers. Quite the opposite— the attackers were Wilson’s fellow Americans, Pennsylvania militiamen who were convinced that Wilson was insufficiently committed to the American cause. Wilson’s primary offense was the deployment of his legal talents in a cause that the militiamen found inexplicable—he had represented men accused of treason against the state of Pennsylvania for aiding the British army during the detested British occupation of Philadelphia. Just two days before the attack, in the grand courtroom at the State House, Wilson had won another acquittal for a man

Figure I.1 Attorney James Wilson, one of only six men who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.

accused of treason. But many of Wilson’s fellow citizens were utterly perplexed. Why was a signer of the Declaration of Independence representing men accused of undermining the very Revolution to which he had pledged his life, his fortune, and his sacred honor? When the militiamen later sought to justify their conduct, they pointed to the “exceeding lenity which has been shown to persons notoriously disaffected to the Independence of the United States” as one of the reasons for the attack on Wilson’s house.2

As the Fort Wilson incident vividly demonstrated, the American Revolution ripped the fabric of American society in half. Although sometimes portrayed as a genteel, intellectual rebellion, it was in fact a violent and bloody civil war, in which brothers fought against brothers and fathers fought against sons.3 An astute Frenchman living in America noted the changes with disbelief: “The rage of civil discord hath advanced among us with astonishing rapidity. Every opinion is changed, every prejudice subverted, every ancient principle annihilated, every mode of organization which linked us before as men and citizens is now altered.”4 It was, in the words of a popular seventeenth-century song, a “world turned upside down.”

The most serious—and frightening—implications of the new upside-down quality of American life related to the law of treason. When the troubles with England began, colonial Americans repeatedly denounced acts of Parliament, but stoutly insisted on their devotion to their English king. Betraying the king was not just a matter of political disloyalty—it was high treason, the most significant offense known to English law.

By the time the War for Independence erupted, the duty of allegiance had been fundamentally transformed. Loyalty to the king was no longer a duty, but a crime—high treason against the nascent American nation. As the British and American armies rampaged across the continent, the duty of allegiance imposed by law shifted with them. In Philadelphia, for example, this duty shifted from George III to the United States, then back to George III during the British occupation of Philadelphia, and finally back to the United States when the British army departed. As the late Robert Ferguson put it, “Nothing conveys the utter fluidity in Revolutionary American Culture more dramatically than the concept of treason.”5

Although Benedict Arnold remains the Revolution’s most famous traitor, the charge of treason could potentially be leveled against every American. Loyalty to the United States was treason against Great Britain, and loyalty to Great Britain was treason against the United States. Even those who tried to remain neutral were criticized on the ground that anyone who was not an active supporter was an enemy. The “Trials of Allegiance” referred to in this book’s title are thus not

only court trials, but also the broader trials that the war and societal disruption posed to everyone living in British North America.

This book is an invitation to view the American Revolution from a new perspective—that of the law of treason. We have numerous accounts of the Revolution rooted in military, diplomatic, social, economic, political, and constitutional history. By contrast, the Revolution’s interaction with the law of treason has remained largely unwritten. But in at least six key areas, treason played a fundamental role in the Revolution and in the lives of ordinary Americans.

First, in the years before the war broke out, American resistance leaders sought to justify the actions they were taking against British measures. These writers repeatedly distinguished legitimate resistance to tyranny, which was permissible, from outright treason, which was criminal. Although the arguments grew more and more distant from British law as the resistance activities increased, they provided much of the intellectual justification for the open defiance of British policies. Similarly, when British leaders threatened to try Americans for treason in England, American leaders responded with vigorous defenses of their right to a trial by a jury of their peers.

Second, although American resistance leaders insisted that they were innocent of treason, they did not hesitate to accuse others of the same offense. Prior to the Declaration of Independence, accusations of treason multiplied, generating rhetoric that was increasingly nationalistic in scope. Opponents of resistance activities were denounced as traitors against America and traitors against liberty. This rhetoric was soon converted into action and individuals accused of treason against America were tried before committees of safety and the military. These trials, scarcely noticed in much of the literature of the Revolution, demonstrated that American sovereignty was a functional reality well before independence was declared. As a practical matter, Americans no longer owed allegiance to the king of Great Britain, but to the individual colonies, to the nascent American state, or even to broad abstractions such as liberty itself.

Third, the Declaration of Independence was itself partially motivated by concerns over treason law. So long as the American colonies remained technically united with Great Britain, the adherents of the king could be indefinitely detained by extra-legal entities, but they could not formally be tried by a jury in a court of law or executed. The Declaration of Independence permitted the full force of the criminal law to be brought upon the Loyalists, and many proponents of the Declaration justified it for precisely that reason.

Fourth, the law of treason loomed large over the daily lives of ordinary people. Allegiances shifted with changes in military occupation, and that allegiance was now enforced through criminal penalties. Thousands of Americans played a role in the criminal justice system, whether as defendants, as witnesses, as bondsmen,

or as jurors. Through the jury system, ordinary Americans would be forced to confront the reality that other ordinary Americans may well have sided with the enemy. But the juries did something extraordinary—they consistently refused to send the defendants to the gallows. In case after case in Pennsylvania, the subject of this study, grand juries refused to indict and trial juries refused to convict. Even in the few cases in which they convicted, juries sought clemency for the defendant. The jury system would prove far more lenient to accused traitors than the two primary alternatives, military trials and trials by committees of safety.

Fifth, confiscation of Loyalists’ property became a major issue during the Paris peace negotiations. Although the states contended that the confiscations were justified under state treason laws, British officials viewed them as illegal and sought compensation. Ultimately, the reintegration of former Loyalists into American society would produce heated denunciations, yet most Loyalists who returned found the path relatively smooth. Reconciliation, not vengeance, would be the order of the day.

Finally, the issue of treason became an early issue testing the strength of the new national government under the Constitution. Two rebellions in Pennsylvania, the Whiskey Rebellion and Fries’s Rebellion, raised difficult questions about the application of English treason law in the new American republic. Should the law apply in the same manner, or had the Revolution limited its bounds, permitting even forceful resistance to particular laws, so long as the participants retained their underlying loyalty to the United States?

This book explores these issues in the course of answering a fundamental question: How did revolutionary Americans apply the law of treason, forged over many centuries in an island monarchy three thousand miles away, to instances of criminal disloyalty in their new republic? This question raises several subsidiary questions. How was the seeming tension between liberty and security resolved? To what extent did the law deviate from English patterns? To which legal entities was allegiance owed? How did patterns of prosecution change during the Revolution itself? And, perhaps most importantly, did institutions make a difference? What can one learn from the differing experiences of the military, committees of safety, and courts?

To be clear, my subject is not the general phenomenon of Loyalism or the motivations that drove people to one side or the other. It is not concerned with the details of treasonable plots or the frequency with which treasonable acts might have been committed. These topics, although fascinating, are beyond the scope of this work and have been well examined by other scholars.6 My purpose is different—to understand how the law of treason was understood and applied in the context of a convulsive, divisive civil war in which few people were free of the imprecation of treason.7 Many of the legal questions that American leaders

confronted during the war were not easy, and they continue to be debated even to this day—whether to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, whether to detain suspected traitors without trial, whether to exercise military jurisdiction over American civilians suspected of aiding the enemy, and whether to permit judicial review of executive detentions.

The book tells the story through the experience of Pennsylvania, as it was here that the issues raised by treason took on their greatest national significance. Pennsylvania was central to the Revolution from the very beginning. Its capital, Philadelphia, was the seat of the Continental Congress and the effective national capital, as well as America’s largest city and busiest port.8 Philadelphia was the “political, economic, and cultural center of the colonies and the new nation.”9 What happened there had nationwide implications. The cast of characters includes some of the most significant figures of the revolutionary era. A series of treason trials in Philadelphia, for example, were presided over by one signer of the Declaration of Independence, defended by two other signers, and involved participants who played a major role in the creation of the United States Constitution. In the early trials, both the presiding judge, Thomas McKean, and the principal prosecuting attorney, Joseph Reed, were simultaneously serving as members of the Continental Congress. Pennsylvania also generated the war’s most intense controversy over treason trials, resulting in extensive newspaper discussions about the proper role of juries and, ultimately, in the violent confrontation and bloodshed of the Fort Wilson incident.

One should not necessarily extrapolate the experience of Pennsylvania without qualification to the other American states. Although I have been researching this issue in Pennsylvania off and on for over twenty years, I have not devoted similar efforts to other jurisdictions, and therefore can offer only a limited comparative perspective.10 Certain factors rendered the Pennsylvania experience distinctive. The patterns of war were different from those in any other state. Although the British occupied New York from 1776 to 1783, they occupied Philadelphia for only nine months in 1778 and 1779. Pennsylvania escaped the early years of the war, which focused on New England, as well as the later years, which focused on the South. Moreover, the large population of Quakers, religiously opposed to bearing arms, presented peculiar problems that were less salient in other states. Pennsylvania’s unusual and controversial 1776 constitution, with its unicameral legislature and plural executive, further rendered Pennsylvania distinctive among the states. Nonetheless, certain broad themes were consistent across jurisdictions, including the pre-Revolution debate about the nature of treason, the role of committees of safety, and the general question of the harshness to be meted out to Loyalists, even though the details may have differed from state to state.

The subsidiary theme of this book is the role of juries. The colonists’ insistence on their right to a jury of their peers was a primary grievance in the years prior to the outbreak of the war. Yet when the fighting started, and internal enemies needed to be detected and subdued, colonial Americans did not resort to juries. Instead, investigatory and detention powers rested in committees of safety or the military, both of which acted without juries, a pattern that continued after independence. When jury trial was finally operational for treason trials, Pennsylvania juries proved exceptionally lenient and this leniency persisted through the rebellions of the 1790s.

The subject of jury service in eighteenth-century America has not been well explored by scholars. In 1975, historians Harold Hyman and Catherine Tarrant lamented the “very thin body of American legal history concerning juries,” and argued that “[f]ew areas of legal history need attention more.”11 In 1984, John Murrin observed that the history of the American jury “has almost completely eluded sustained scholarly attention.”12 Jury trials have received some attention in the intervening years, but it is safe to say that we still know very little about how criminal juries actually functioned in late eighteenth-century America.13 It has been relatively straightforward to document what learned contemporaries said about juries, but it is much harder to determine what juries actually did. This lack of information is regrettable, because as historian J.R. Pole pointed out in 1993, trial by jury “is of the highest importance for understanding the character of American history in its colonial period and beyond.”14

Chapters 6 and 7, the heart of this book, consider twenty-three jury trials prosecuted in Philadelphia in the fall of 1778 and the spring of 1779. These trials were aggressively prosecuted by the state in an atmosphere of widespread popular hostility to opponents of the American Revolution. The juries, however, convicted only four of these men, a low conviction rate even in an age of widespread jury lenity; moreover, in three of these four cases, the juries petitioned Pennsylvania’s executive authority for clemency. What explains this lenity?

To answer this question we need to know more about the jurors themselves. Although the jury is often described as a black box, it can be illuminated, even after the passage of several hundred years. This book provides the most thorough analysis yet undertaken of a group of eighteenth-century American jurors. On the basis of extensive research in demographic records, I have reconstructed the Philadelphia jury box and identified not only the social status of the jurors, but also the intricate network of connections linking the grand jurors, the trial jurors, and the defendants. This study reveals, for the first time, how eighteenth-century American defense counsel creatively used peremptory challenges, deployed on the bases of religion, age, ethnicity, wealth, occupation, and political beliefs, to create juries more favorable to the defense. Jurors were also heavily influenced by

the death penalty, effectively nullifying Pennsylvania’s treason laws rather than risk exposing accused persons to the hangman’s noose.

But the jury verdicts did not go unchallenged. Significant popular opposition to the jurors’ decisions led in 1779 to widespread condemnation in newspapers, to direct interference with a jury trial, and eventually to the armed attack on James Wilson’s house. After Fort Wilson, attacks on juries diminished dramatically, and the jury recaptured its central role as a bulwark of popular liberty.

Recovering the world of treason and the American Revolution requires immersion in a much broader array of sources than the few accounts of American treason law have traditionally employed. Prior work has tended to emphasize statutes and the tiny handful of reported cases. Statutes are an important part of the story, but as legal historian Bruce Mann has emphasized, “The best evidence for the presence or absence of legal change lies not in what people said but in what they did. For that, one must consult court records in tedious, preferably quantitative, detail.”15 The court records of Pennsylvania are not located in one place, and I have had to piece together information on court proceedings from a variety of archival and other sources. This material is presented in quantitative, although I hope not especially tedious, detail.

Many years ago, James Willard Hurst argued that

even a brief canvass of the variety of historical sources of potential help in explaining the policy background of the Constitution’s treason clause suggests the complex wealth of material which such an approach may add to the case-trained lawyer’s familiar tools of decision and opinion. But, likewise, it suggests that since the historical approach seeks nothing less than to comprehend the whole pattern of causes which shape a given policy, it requires of the advocate an imaginative readiness to forego the abstract logic of doctrine for the living logic of events.16

To fulfill Hurst’s vision, I have also examined what Steven Wilf calls “extraofficial legal actions—what might be called law out-of-doors, vernacular legal storytelling, the bric-a-brac of criminal trials, and, above all, the explosion of law talk with a volatile mix of law and politics.”17 These materials are supplemented with newspaper sources, pamphlets, and manuscript collections of letters and diaries, all of which provide a rich description of law on the ground, as it actually played out in the lives of ordinary and not-so-ordinary Pennsylvanians.

For the convenience of other researchers, I have cited published versions of eighteenth-century sources when possible, although in many cases I have examined the originals myself. Obviously, some editions are more reliable than others, and there are particular problems with the Colonial Records and

Pennsylvania Archives series, including the bowdlerization typical of nineteenthcentury editors.18

In some cases, I have modernized punctuation and capitalization for the ease of the reader, although I have tried to do so with a light touch. I have tried to retain the terminology of the eighteenth-century sources as much as possible, although this task presents occasional difficulties. There is no perfect term for the opponents of the Revolution. They were described as “Tories” by the Revolution’s supporters, but this wasn’t a term they embraced themselves. The term “Loyalist” wasn’t coined until later in the conflict. Some historians have used the term “disaffected” to describe persons alienated from the revolutionary governments for a wide variety of reasons, many of which had nothing to do with loyalty to Great Britain, but this doesn’t always capture the spirit of the contemporary sources.19 I have tried to use terms that are appropriate in context, but there is no perfect solution to this problem.

Another troublesome term is “prisoner.” In the late eighteenth century, before the introduction of the modern American prison, the term was used to describe any person held in captivity, including persons awaiting trial. Modern usage tends to define “prisoner” as a person sentenced to a term of imprisonment in prison after a trial. Using “prisoner” in its eighteenth-century sense is therefore more likely to be confusing than helpful to a modern reader. Accordingly, I use the admittedly anachronistic term “detainee” to describe persons who have been detained, but not formally sentenced in a court of law. Although the term was not used in the eighteenth century in this context, I can think of no other way of precisely describing the legal situation of these individuals to a modern reader.

A brief overview by way of orientation: Chapter 1 explores the background of treason in colonial Pennsylvania, including the adoption of British treason law and the legal complexities that led to a general failure of the state to prosecute individuals for treason. Chapter 2 turns to the bitter debates between 1765 and 1775, when Americans defended themselves against charges of treason, while simultaneously hurling the same charge at British officials, and even at the king himself. Chapter 3 addresses the period between the outbreak of the war and the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, focusing primarily on the treason trials conducted by committees of safety. The tumultuous period between formal independence and the reopening of the courts is the subject of Chapter 4, including the controversial suspension of habeas corpus in the wake of the British invasion. The difficulties of reopening the courts, the issuance of attainder proclamations, and the wave of cases generated by the British invasion are considered in Chapter 5. Chapters 6 and 7 provide an extensive analysis of the Philadelphia treason trials of 1778 and 1779, the most significant treason trials of the American Revolution. Chapter 8 evaluates the aftermath of the trials,

including the turbulent year of 1779, the repercussions of Benedict Arnold’s treason in 1780, and disputes over the scope of executive detention powers.

Chapter 9 deals with the aftermath of the war, the adoption of the Treason Clause of the United States Constitution, and the first federal treason trials, those arising out of the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794 and Fries’s Rebellion of 1799.