Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements are due to The Robert Frost Review, The Yearbook of English Studies, and CounterText, in which extracts from three chapters have previously appeared. The Sonnet has been a long time in the making, and I owe a great debt of thanks to friends and colleagues who have offered help and guidance along the way. I am especially grateful to Ted Chamberlin and Lorna Goodison for their unwavering support and enthusiasm, and to Terry Eagleton for many years of friendship and encouragement. Ewan Fernie, Bernard O’Donoghue, and Ron Schleifer all generously took time to read and comment on parts of the book, and I am hugely thankful for their many helpful suggestions and illuminating insights. For various acts of kindness and advice, I am deeply indebted to Sue Asbee, Chris Bissell, Tom Bristow, Lars Burman, John Davison, Maura Dooley, Rachel Falconer, Deanna Fernie, Helen Habibi, Hugh Haughton, David Johnson, Laura McKenzie, Michael Parker, Jahan Ramazani, Stephen Reimer, Nicholas Roe, Dan Ross, Kiernan Ryan, Yasmine Shamma, Alison Shell, Katherine Skaris, Terence Spencer, and Colm Tóibín.The preparation of the book was overseen with great care and thoughtfulness by Aimee Wright at OUP. I am grateful to Timothy Beck for his excellent copy-editing and Kate Legon for her meticulous indexing. I have been blessed with the best and most patient of editors in Jacqueline Norton. I should like to thank my colleagues at Durham University for their constant support and good will. It has been a great pleasure to work closely with Michael O’Neill, whose studies of poetry and poetic form have been an inspiration. I have learned a good deal along the way from Paul Batchelor, Robert Carver, Stefano Cracolici, David Fuller, Jason Harding, Barbara Ravelhofer, Gareth Reeves, Barry Sheils, and Patricia Waugh. Financial assistance for permissions and artwork was kindly provided by the research committees of the Department of English Studies and the Faculty of Arts and Humanities at Durham University, and I am grateful for the advice and support of successive directors of research: John Nash, Fiona Robertson, Corinne Saunders, and Sarah Wootton. I wish to thank the Department of

English at Harvard University for granting me a research fellowship to work on the book, along with many opportunities for stimulating discussion. In particular, I should like to record my gratitude to Helen Vendler for her illustrious work on Shakespeare and Keats, as well as many other poets, and to Stephanie Burt, whose critical studies of the sonnet have been invigorating and enlightening.

The book draws on conversations and correspondence with several of the poets whose work appears in its pages, and I should like to express my thanks to Ciaran Carson, Wendy Cope, Douglas Dunn, Alan Gillis, Robert Hampson, Tony Harrison, Seamus Heaney, Andrew McNeillie, Andrew Motion, Paul Muldoon, Don Paterson, Tom Pickard, and Anne Stevenson. I wish to record my heartfelt thanks to Derek Walcott, with whom I spent many happy hours in St Lucia, reading sonnets aloud and from memory against the gentle hush of the Caribbean Sea . . . ‘words which love had hoped to use | Erased with the surf’s pages’.

* * *

Every effort has been made to trace and contact copyright holders prior to publication. If notified, the publisher will be pleased to rectify any errors or omissions at the earliest opportunity. I am grateful for permission to reproduce the following excerpts:

• Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus, and Giroux: ‘Sonnet’ [1979] from The Complete Poems 1927–1979 by Elizabeth Bishop. © 1979, 1983 by Alice Helen Methfessel. ‘X’ from ‘Glanmore Sonnets’ from Opened Ground: Selected Poems 1966–1996 by Seamus Heaney. © 1998 by Seamus Heaney. Excerpts from ‘Inauguration Day: January 1953’, ‘Night Sweat’, and ‘The Dolphin’ from Collected Poems by Robert Lowell. © 2003 by Harriet Lowell and Sheridan Lowell. ‘Lull’ from Poems: 1968–1998 by Paul Muldoon. © 2001 by Paul Muldoon. ‘Quoof’ and ‘Why Brownlee Left’ from Selected Poems 1968–2014 by Paul Muldoon. © 2016 by Paul Muldoon.

• ‘Lay Your Sleeping Head, My Love’, and ‘Brussels in Winter’, © 1940 and renewed 1968 by W. H. Auden; ‘The Secret Agent’, © 1934 and renewed 1962 by W. H. Auden; ‘Sonnets from China XXI: To E. M. Forster’, © 1945 by W. H. Auden, renewed 1973 by The Estate of W. H. Auden; and ‘In Time of War’ from W. H. Auden Collected Poems by W. H. Auden,

© 1976 by Edward Mendelson,William Meredith, and Monroe K. Spears, Executors of the Estate of W. H. Auden. Used by permission of Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

• Edmund Blunden, ‘Vlamertinghe: Passing the Chateau’ from Undertones of War, Penguin Books.

• ‘Prayer’ from Mean Time by Carol Ann Duffy. Published by Picador, 2013. © Carol Ann Duffy. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd, 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN.

• ‘1798’ from The Alexandrine Plan (1998) and ‘Au Cabaret-Vert’, Collected Poems (2008) by Ciaran Carson, by kind permission of the author and The Gallery Press, Loughcrew, Oldcastle, County Meath, Ireland.

• Ken Edwards, ‘Darkly Slow’ and ‘His Last Gasp (2)’, eight + six (2003), by permission of the author.

• Robert Hampson, from ‘Reworked Disasters or: Next Checking Out the Chapmans’ Goyas’, The Reality Street Book of Sonnets, ed. Jeff Hilson (London: Reality Street, 2008), by permission of the author and the publisher.

• Landing Light by Don Paterson. Published by Faber and Faber Ltd, 2003. © Don Paterson. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd, 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN and Faber and Faber Ltd.

• ‘The Kaleidoscope’ and ‘Sandra’s Mobile’ by Douglas Dunn from Elegies (© Douglas Dunn, 1982) are printed by permission of United Agents <www.unitedagents.co.uk> on behalf of Douglas Dunn.

• ‘Why Brownlee Left’, ‘Lull’, ‘Quoof’ from New Selected Poems by Paul Muldoon, by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

• Seamus Heaney,‘Glanmore Sonnets’ from Field Work (1979), and ‘Fosterling’ from Seeing Things (1991), by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

• ‘Autumn Refrain’ from The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens by Wallace Stevens, © 1954 by Wallace Stevens and copyright renewed 1982 by Holly Stevens. Used by permissions of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. All rights reserved and by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd.

• Wendy Cope, ‘Faint Praise’ and ‘The Sitter’ from Two Cures for Love: Selected Poems 1979–2006 (2008) by permission of the author and Faber and Faber Ltd.

• Wendy Cope, ‘Strugnell’s Bargain’, by permission of the author.

• The poems of Patrick Kavanagh are reprinted from Collected Poems, edited by Antoinette Quinn (Allen Lane, 2004), by kind permission of the Trustees of the Estate of the late Katherine B. Kavanagh, through the Jonathan Williams Literary Agency.

• Eleanor Brown, Sonnets 3 and 33 in Maiden Speech (Bloodaxe, 1996), by permission of the publisher.

• Anne Stevenson, ‘Sonnets for Five Seasons’ from Poems 1955–2005 (Bloodaxe, 2004) by permission of the publisher.

• Elizabeth Jennings, ‘A Sense of Place’ and ‘Sources of Light’ from The Collected Poems, Carcanet Press.

• Michael Longley, ‘Ceasefire’, ‘The Vision of Theoclymenus’, and ‘The Beech Tree’ from Collected Poems, © Michael Longley 2006.

• ‘Heroic’. © 1998 by Eavan Boland, ‘Yeats in Civil War’, from New Collected Poems by Eavan Boland. Copyright © 2005, 2001, 1998, 1994, 1990, 1987, 1980, 1975, 1967, 1962 by Eavan Boland. Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

• ‘next to of course god america I’. © 1926, 1954, © 1991 by the Trustees for the E. E. Cummings Trust. © 1985 by George James Firmage, from Complete Poems: 1904–1962 by E. E. Cummings, edited by George J. Firmage. Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation.

• ‘Exequy’ (from the Italian of Petrarch) translated by Derek Mahon from Echo’s Grove (2013) by kind permission of the author and The Gallery Press, Loughcrew, Oldcastle, County Meath, Ireland.

• ‘The Mayflower’, ‘Sonnet to Eva’, and ‘Aftermath’ from The Collected Poems of Sylvia Plath, edited by Ted Hughes. © 1960, 1965, 1971, 1981 by the Estate of Sylvia Plath. Editorial material © 1981 by Ted Hughes. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

• Edwin Morgan, ‘Glasgow Sonnets’, Collected Poems, by permission of Carcanet Press Limited.

• Andrew McNeillie,‘Glyn Dwr Sonnets’, Slower, by permission of Carcanet Press Limited.

• Siegfried Sassoon, ‘Remorse’, ‘Two Hundred Years After’, ‘Trench Duty’, ‘A Subaltern’. © Siegfried Sassoon by kind permission of the Estate of George Sassoon.

• Geoffrey Hill, from ‘Requiem for the Plantagenet Kings’, ‘Funeral Music’, ‘Lachrimae’, and ‘An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture in England’ from Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952–2012, edited by Kenneth Haynes, by kind permission of the Estate of Geoffrey Hill.

• Tony Harrison, ‘On Not Being Milton’, ‘Book Ends’, ‘Continuous’, and ‘Marked with D’ from Selected Poems, by kind permission of the author.

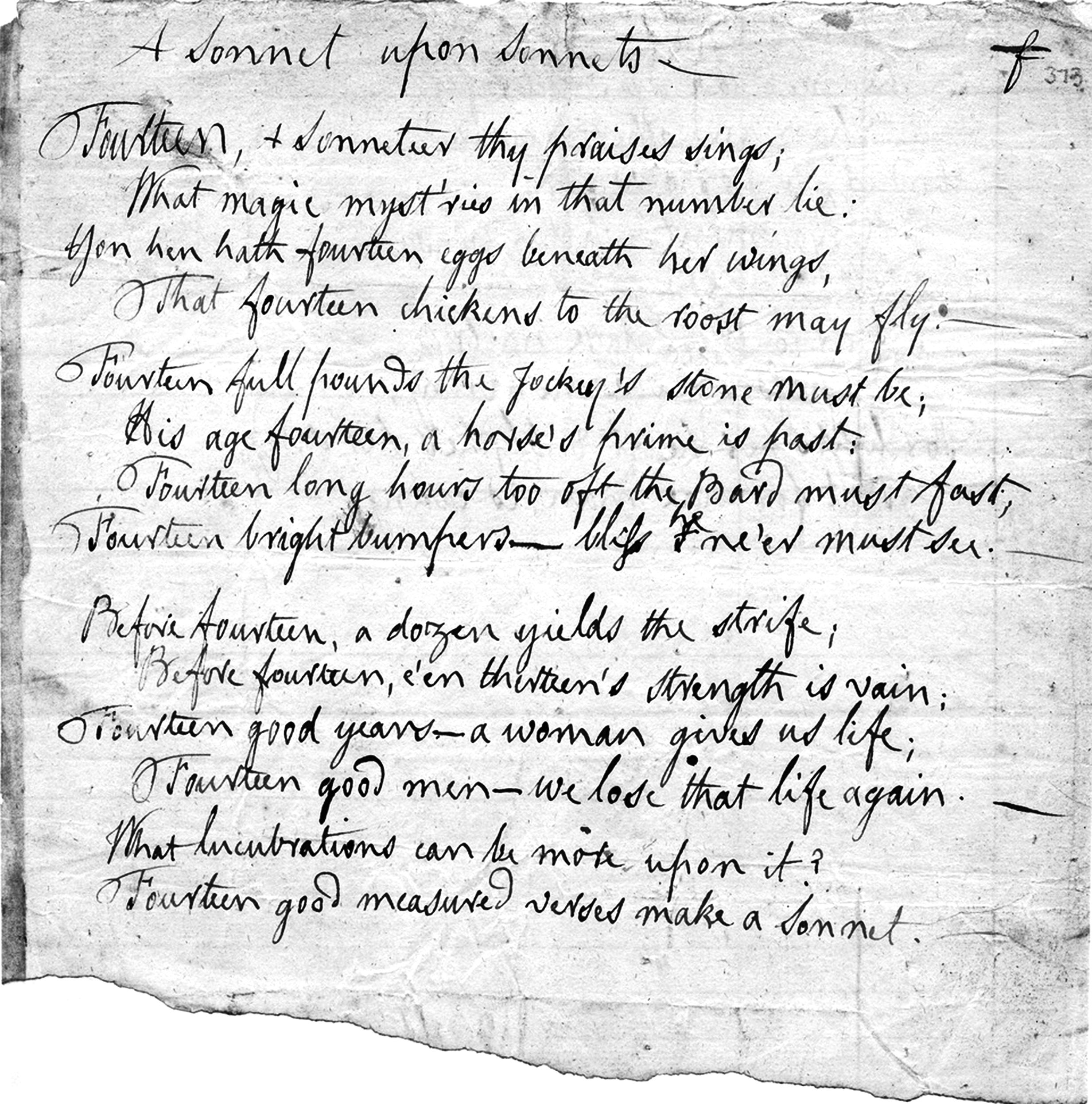

Figure 1 Robert Burns, ‘A Sonnet upon Sonnets’, by kind permission of the National Trust for Scotland.

Introduction

The form of the sonnet

The sonnet is one of the oldest poetic forms and also one of the most widely travelled. Over several centuries it has come to be associated with intense imaginative life, and with an intimate exploration of thought and feeling. Although it has a well-established place in English poetic tradition, the sonnet is also a resilient and versatile form that continually invites experimentation and renewal. Some of the best-known poems in English are sonnets—among them ‘Ozymandias’, ‘The Windhover’, and ‘Leda and the Swan’—and the most accomplished sonnets are poems, like these, that capture some profound and far-reaching vision, a powerful revelation, or a startling insight, in the space of just fourteen lines.1 The challenge of finding an appropriate voice or capturing an impression within that circumscribed space continues to give the sonnet a special appeal among writers and readers alike. Primarily a love poem, the sonnet has extended its remit over the centuries, to become not only the pre-eminent form for the poetry of sexual desire and disillusionment, but also a form ideally suited to religious devotion, elegiac mourning, political protest, philosophical reflection, and topographical description. What distinguishes the sonnet over the course of its development, however, is not so much its variety of subject matter as its powerfully condensed expression of ideas and emotions, and its elaborate use of rhyme and rhythm for eloquent, persuasive speech.

The sonnet is a lyric poem, and like other kinds of lyric poetry it appeals to its readers through those special qualities peculiar to the genre: brevity,

1. Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Major Works, ed. Zachary Leader and Michael O’Neill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 198. Gerard Manley Hopkins, The Major Works, ed. Catherine Phillips (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 132;W. B. Yeats, The Major Works, ed. Edward Larrissy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 112.

musicality, and intimacy. At the same time, the sonnet acquires its special distinctiveness by accommodating the rhythms and stresses of the speaking voice within its prescribed form.The brevity of the sonnet is one of its chief hallmarks, aptly summed up by the great Scots poet, Robert Burns, in the fourteenth line of his ‘Sonnet upon Sonnets’: ‘Fourteen good measur’d verses make a sonnet’.2 Even when the sonnet form is playfully curtailed to eleven or twelve lines (as it is by Gerard Manley Hopkins and W. B. Yeats) or willfully extended to sixteen lines (as it is by George Meredith and Tony Harrison), the experiment is measured against that time-honoured requirement of fourteen lines. Most practitioners of the sonnet, however, would probably claim that a little more elaboration is needed by way of definition. What gives the sonnet its structural identity, as we will see, is not just the number but also the deployment of its lines. The sonnet is a dynamic form, and its energy and momentum are generated through the articulation of carefully weighted structural components. The traditional division of the sonnet’s fourteen lines into units of eight and six (an octave and a sestet) opens up considerable intellectual and emotional possibilities in terms of playing off one kind of statement or expression against another. The further division of fourteen lines into units of four and three (quatrains and tercets) multiplies these possibilities, encouraging a close correlation between intricate form and complex thought.

Burns speaks of measured lines, suggesting metre and musicality, and traditionally the measure associated with the sonnet written in English has been the staple line of iambic pentameter, a ten-syllable line with alternating stresses, as with this opening line from Shakespeare’s Sonnet 104: ‘To me, fair friend, you never can be old’.3 Some of the most imposing effects in sonnet writing, however, have come from poets varying the stress patterns, either by crossing these with other modulations found in the speaking voice or by introducing different metrical patterns that disrupt the basic iambic rhythm. Burns himself ironically evades the good measured verse associated with the English sonnet, and lets his syllables spill over in a casually relaxed imitation of actual speech: ‘Fourteen good measur’d verses make a sonnet’. Musicality in the sonnet is also produced by rhyme, and once again there is considerable room for variation and experimentation in the space of just

2. Robert Burns, Poems and Songs, ed. James Kinsley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971), p. 357.

3. William Shakespeare, The Complete Sonnets and Poems, ed. Colin Burrow (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p. 589.

fourteen lines, with the octave-sestet and quatrain-tercet divisions encouraging patterns that can be adhered to or denied, in keeping with the subject matter and the function of each individual sonnet.

Just as important to the lyric appeal of the sonnet as its brevity and musicality is its intimacy. Though usually less obvious than its other qualities, the intimacy or ‘interiority’ of the sonnet is a vital part of its repertoire of effects. As Helen Vendler reminds us, lyric poems are principally poems of self-definition and self-declaration, and they avail themselves of a wide range of speech acts or utterances, including apology, celebration, command, consolation, debate, declaration, description, explanation, invitation, invocation, lament, meditation, narration, prayer, reproach, surmise, warning, and yearning. What characterizes the lyric poem above all else is its ‘active process of thinking’, and the sonnet arguably exemplifies this quality of lyric thinking, of ‘thought made visible’, more powerfully and persistently than any other poetic form. What Vendler memorably describes as ‘the performance of the mind in solitary speech’ in Shakespeare’s sonnets holds good for many sonnets written earlier and later, encouraging us to appreciate the sonnet form as an intense kind of verse soliloquy.4

The lyrical qualities of brevity, musicality, and intimacy brought to fruition in the sonnet form can be readily observed in a poem written by John Keats in January 1818:

When I have fears that I may cease to be Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain, Before high-piled books in charactery, Hold like rich garners the full ripen’d grain; When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face, Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance, And think that I may never live to trace Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance: And when I feel, fair creature of an hour, That I shall never look upon thee more, Never have relish in the faery power Of unreflecting love;—then on the Shore Of the wide world I stand alone, and think Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.5

4. Helen Vendler, Poets Thinking: Pope, Whitman, Dickinson, Yeats (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), p. 6. The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1997), p. 2.

5. John Keats, Poetical Works, ed. H. W. Garrod (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970), p. 366.

The sonnet is movingly candid in declaring its fears of premature death and its anxious hopes of fulfilment in love and literary fame. What is most striking, though, is the way in which these fourteen lines vividly convey the subtle processes of thought and feeling. There is an articulate energy here, shaping the linguistic contours of the poem in a way that resembles the play of mind.The opening line is starkly and intimately in keeping with the brief duration of the sonnet itself, and the idea of imminent demise is carried through in the emphatic ‘Before’ and the repeated temporal clauses, ‘When I behold’ and ‘when I feel’. Each ‘when’ marks the beginning of a quatrain, corresponding to a new phase of thought, and the third ‘when’ (line 9) also initiates a movement or turning from ‘think’ in the octave to ‘feel’ in the sestet, and from the speculative ‘never live’ to the more immediate ‘never look’.We return to ‘think’ at the precarious end of the penultimate line, where the sonnet dramatically depicts the solitary mind in communion with itself. Keats shows us how the sonnet form is perfectly suited to an exploration of troubling, painful contraries, and how its tightly compressed shape paradoxically enables imaginative vistas of sublime intensity.

Keats’s ‘wide world’ recalls the opening lines of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 107 (‘Not mine own fears, nor the prophetic soul | Of the wide world dreaming on things to come . . . ’), and there is much that looks back to Shakespeare in this poem, including its temporal phrasing, its quatrain divisions, and its rhyme scheme.6 This was, in fact, the first sonnet in which Keats fully attempted the Shakespearean form, with its alternating rhymes and closing couplet. Like many sonnets, including those of Shakespeare, it reveals a strong preoccupation not just with love and death, but with writing and reading, and with the value of poetry itself in a world overshadowed by ultimate ‘nothingness’. At the same time, we can find in Keats’s sonnet those qualities that perhaps belong more obviously to Romantic poetry, including its emphasis on what it is to ‘feel’ as well as think. We can also note those stylistic flourishes that are peculiarly Keats’s own, including the strong caesura in line 12 and the fluent enjambment that follows, both of which allow for a subtle modulation of rhythm in the closing lines, and so avoid too neat a concluding statement in the couplet. In reading sonnets, we need to be alert both to convention (what is clearly tried and tested) and to innovation (what is generally untried and untested), and so it helps to be acquainted with the history and development of the form. Even when they

6. The Complete Sonnets and Poems, ed. Burrow, p. 595.

appear to be radically transgressive and disruptive, sonnets are often shaped by ideas and techniques that are already part of tradition.

The origins of the sonnet

The sonnet originated in Italy as early as 1230, acquiring its basic form in the writings of a small group of poets working at the court of Emperor Frederick II of Sicily. The poetic template of fourteen lines with an intricate rhyme scheme has been attributed to Giacomo da Lentino, the emperor’s notary and legal assistant, who composed twenty-five sonnets with distinctive patterns of rhyme, either abab abab cde cde or abab abab ccd ccd 7 The repetition and variation of rhyme, indicated here by the spacing, suggests that, from the outset, the sonnet was designed as a form with a dynamic internal structure: an octave (eight lines) and a sestet (six lines), which can be further divided into two quatrains (four lines) and two tercets (three lines). Literary historians refer to the ‘invention’ of the sonnet, rightly crediting its earliest practitioners with a degree of ingenuity, but in subject matter, at least, it was very likely inspired by the yearning love lyrics of the eleventhcentury Provençal troubadour poets. Technically, the octave of the sonnet resembles the eight-line Sicilian peasant song known as the strambotto, and the sestet might well have been adapted from the existing canzone, another song-like form with stanzas of seven to twenty lines. In any case, the addition of the sestet to the octave, with a clearly marked turn or volta between them, creates a form more akin to speech than song, a discursive structure encouraging the progression of thought in meditation, reflection, and intellectual debate.

The name ‘sonnet’ comes from the Italian sonetto, a diminutive version of suono, meaning ‘sound’, and the idea of the sonnet as a small space or echo chamber for the sounding voice has inspired many of its finest achievements. The sound of the human voice, with all its various nuances and inflections, has informed and shaped the sonnet from the beginning. In court circles throughout Europe, eloquence was equated with power, an opportunity for the courtier to establish a position of respect and influence through elaborate and persuasive speech. Sonnets came to be associated with pleading and

7. Michael R. G. Spiller, The Development of the Sonnet: An Introduction (London: Routledge, 1992), p. 13.

bargaining, the eloquent speech of the lover functioning as an intimate enactment of larger power relations in court society. One of the persistent features of the sonnet is the assertion of a dramatized self or persona, a speaking voice that appeals to an imagined listener through a carefully staged set of arguments and explanations. Among a narrow social elite trained in law and philosophy, the sonnet functioned as an exercise in rhetorical persuasion and as an intellectual game or pastime. Sonnets were exchanged and circulated in a spirit of dialogue and competition, initially among small literary coteries in southern Italy, and then throughout Britain, France, Spain, and other parts of Europe.

The perfection of the Italian sonnet is generally associated with the work of its two greatest exponents, Dante Alighieri and Francis Petrarch (Francesco Petrarco), though the form was well established by the time they came to use it. Dante and Petrarch succeeded in elevating the sonnet as a form dedicated to the sorrows and sacred mysteries of love, and their influence on the so-called ‘amatory tradition’ lasted throughout the Renaissance and well into the nineteenth century. Shelley, in his inspiring ‘Defence of Poetry’ (1821), acknowledged Petrarch’s poems as ‘spells, which unseal the inmost enchanted fountains of the delight which is in the grief of love’, and claimed that ‘Dante understood the secret things of love even more than Petrarch’.8 What Dante and Petrarch also established in the history of the form is the idea of the sonnet as part of a series or sequence that allows for narrative expansion and makes possible what we might now see as psychological exploration or emotional autobiography.

Dante’s Vita Nuova (c.1292) incorporates twenty-five sonnets and a small number of other poems within an autobiographical and critical prose narrative recording the poet’s childhood encounter with Beatrice and his flourishing love for her throughout his adult life. The apotheosis of Beatrice, the donna angelicata of the later Divine Comedy, instils the sonnets with an unprecedented emotional intensity and visionary beauty. The skills of rhetoric and verbal articulation associated with the early Italian sonnet are given a new lucidity and brilliance characteristic of the dolce stil nuovo (‘sweet new style’) of Dante’s generation of poets. By the time Petrarch started writing sonnets in the 1330s, the sonnet form was already a century old and highly sophisticated as a poetic instrument of reasoning and argumentation. His Rime Sparse

8. Percy Bysshe Shelley, The Major Works, ed. Zachary Leader and Michael O’Neill (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 674.

(‘Scattered Verses’), also known as the Canzoniere, is a collection of 317 sonnets set alongside other poetic forms, including madrigals and ballads. Ostensibly addressed to Laura de Sade, who was born in Avignon and died there of the Black Plague in 1348, the sonnets have an extraordinary power to convey the pleasures and torments of love, and they do so with an intense and sensitive understanding of the divided self that would strike many readers as paradigmatically modern. Without the spiritual resolution of Dante’s Vita Nuova, Petrarch’s sonnets confront the fierce tensions and contraries endured by the self in its quest for beauty and love. In candidly depicting the painful suffering of love, as well as its glorious pleasures and desires, and in fashioning a speaker sometimes on the edge of incoherence and breakdown, Petrarch provided the most powerful inspiration for the love poetry of Renaissance Europe.

What came to be known as the Petrarchan sonnet consists of an octave in enclosed or envelope rhymes rather than in open or alternating rhymes (abbaabba rather than abababab) and a sestet typically rhymed cdecde or cdcdcd (occasionally with another variation such as cdedce or cdeced).The open octave (abbaabba) was already being used by Guittone d’Arezzo and other poets of the stilnovisti well before the end of the thirteenth century, but Petrarch is generally credited with having consolidated the Italian form, bringing it to a new standard of technical expertise in his Rime. As John Fuller points out, ‘The essence of the sonnet’s form is the unequal relationship between octave and sestet’, and that structural relationship has enormous semantic potential in terms of how a sonnet might progress and open up multiple perspectives and interpretive possibilities.9 The bipartite structure of octave and sestet allows for a number of possible intellectual and emotional developments, including observation and conclusion, and statement and counterstatement, with the turn between the eighth line and the ninth line signalling a shift in mood or opinion, or else an intensification or reaffirmation of an existing idea or feeling.

Within this larger structural framework, however, the quatrain and tercet subdivisions encourage a more complex and complicated set of relationships. The first quatrain, for instance, might ask a question or propose an idea that the second quatrain then answers or elaborates upon. The first tercet then proceeds to prove the point or test its veracity, while the second tercet moves towards resolution and conclusion. The logical procedures of the

9. John Fuller, The Sonnet (London: Methuen, 1972), p. 2.

sonnet are reinforced by prosody, in that the eight lines of closed rhyme in the octave have a steady movement induced by repetition, while the sestet is likely to appear unpredictable, as well as more intense and urgent, with three rhymes in six lines coming quickly after two rhymes in eight. Within the compressed space of the sonnet, the distribution of pauses induced by mid-line punctuation and the pace resulting from the alternation of run-on lines and end-stopped lines are all the more effective in channelling and controlling the flow of thought and meaning. What the sonnet demonstrates very clearly and decisively is the dynamic relationship between form and subject matter.

It was not until the early sixteenth century that the sonnet became established in the vernacular languages of Britain, France, and Spain. The Petrarchan sonnet enjoyed a new lease of life in courtly circles, often introduced by diplomats travelling between Italy and other European countries. The first sonnets in English were written by Sir Thomas Wyatt and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, both closely associated with the court of Henry VIII. Some of these sonnets are rough translations and versions of Petrarch’s Rime, but in their concern with decorum, conduct, and eloquence they articulate the values and attitudes of English court life. The courtly discourse of these early English sonnets, brimming with dedications and compliments, reveals a strong commitment to ideals of honour and service, but it also brings with it an underlying anxiety about position and status, and (especially in Wyatt’s writings) a deep sense of political insecurity.

Wyatt not only imported the Petrarchan sonnet into Britain but also introduced a major structural change, reorganizing the sestet so that it functioned effectively as a third quatrain with a closing couplet: abba abba cddc ee (as the spacing here suggests). This innovation subtly alters the dynamics of the sonnet, giving it force and progression as an instrument of reasoning and disputation, with the couplet sometimes serving as a witty apophthegm or proverbial maxim, an opportunity for the display of courtly wisdom and worldliness. Where the couplet coincides with a sense unit or stands as an independent syntactical entity, its clinching effect is all the more emphatic and decisive. Michael Spiller sees Wyatt’s technical handling of the sonnet in relation to ‘a secular world of practical courtly reality’, with the couplet helping to shape a preoccupation with ‘the practical wisdoms of secular humanist court life’.10

10. Michael Spiller, Early Modern Sonneteers: From Wyatt to Milton (Tavistock: Northcote House, 2001), p. 20.

Surrey further amended the structure of the nascent English sonnet by adopting alternating rhymes in the octave, and by introducing a greater variety of rhyme words than the Italian sonnet possessed, so facilitating the challenge of rhyming in English: abab cdcd efef gg. This is the form that came to be known as the English or Shakespearean sonnet, even though it would be another half century or so before Shakespeare widely popularized the form and employed it with an unprecedented stylistic brilliance in his Sonnets (1609). Wyatt and Surrey never saw their sonnets in print, but their poems were collected and published by Richard Tottel in a volume titled Songes and Sonettes, written by the right honorable Lorde Henry Haward late Earle of Surrey, and other (1557), later referred to simply as Tottel’s Miscellany.

The history of the sonnet in Britain in the later part of the sixteenth century, from Wyatt and Surrey to Shakespeare, is dominated by the huge success and popularity of the sonnet sequence.The holy sonnets in A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner (1560) by Anne Lok (also spelled Locke) constitute the first sequence in English, but the tradition of passionate, erotic sonnets in a narrative or autobiographical sequence is prompted by Thomas Watson’s eighteen-line (sonnet-like) love poems in Hekatompathia (1582). The final decade of the sixteenth century witnessed some of the most prolific and inventive sonnet writing of the Elizabethan period, with Sir Philip Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella (1591) and Edmund Spenser’s Amoretti (1595) among its notable achievements. Samuel Daniel’s Delia (1592) and Michael Drayton’s Ideas Mirrour (1595), later retitled Idea, went through numerous editions and reprints in the late 1590s and early 1600s, testifying to the growing readership and popular interest that the sonnet attracted at the time.

For all the imaginative ambitiousness and dramatic potential invested in the sonnet sequence, it is invariably the local stylistic effects of individual sonnets that readers respond to and recall. One of the most frequently anthologized sonnets from Drayton’s Idea shows how well a single love sonnet can make an impact, even when abstracted from its sequence:

Since there’s no help, come let us kiss and part.

Nay, I have done: you get no more of me,

And I am glad, yea glad with all my heart

That thus so cleanly I myself can free.

Shake hands for ever, cancel all our vows,

And when we meet at any time again,

Be it not seen in either of our brows

That we one jot of former love retain.

Now at the last gasp of love’s latest breath,

When, his pulse failing, passion speechless lies, When faith is kneeling by his bed of death And innocence is closing up his eyes, Now, if thou would’st, when all have given him over, From death to life thou might’st him yet recover.11

What Drayton captures so well here, in a style that we also find in the sonnets of Sir Philip Sidney and John Donne, is the impression of a passionate, personal outburst and dramatic confrontation. The lively colloquial tenor is maintained through repeated imperatives and associated gestures (‘Come let us kiss . . . Shake hands for ever . . . ’), as well as through the short, impassioned exclamations, ‘Nay’ and ‘yea’. The sonnet vividly contrasts the torments of an enslaving love with its miraculous recovery, just as it shows us both the speaker’s proud disdain and his desperate hopes. There is obvious wit in the shape and direction of the sonnet, in the way that it begins with a strong sense of closure—‘You get no more of me’—and closes with a possible new beginning. There is a touch of comic farce, as well, in the scuttling personifications of love, passion, faith, and innocence. All of these stylistic effects, however, are carefully orchestrated within the overriding formal structure provided by the octave-sestet division and the quatrain-couplet sub-division. The first quatrain (abab) issues a strong declaration of parting, and the second quatrain (cdcd ) reiterates and intensifies it. The turn between octave and sestet is clearly indicated by the temporal marker,‘Now’, repeated emphatically at the beginning of the closing couplet. The third quatrain (efef ) moves towards the final extinction of love, but dramatically suspends the process through the repeated conjunction ‘When’, allowing the couplet (here syntactically connected rather than independent) to effect a further turn and assert the possibility of recovery.

Before the 1590s, the term ‘sonnet’ appears to have been used very loosely in England to describe any short lyric poem. It was also conveniently grouped with ‘songs’, as in the title of John Donne’s Songs and Sonnets (1633), a book which, strictly speaking, contains no sonnets at all. The Elizabethan poet George Gascoine was clearly alert to the possible confusion regarding the English sonnet, helpfully offering one of the earliest definitions of the form in 1575:

Then have you sonnets: some think that all poems (being short) may be called sonnets, as in deed it is a diminutive word derived of sonare, but yet I can best

11. The Oxford Book of Sonnets, ed. John Fuller (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), p. 35.

allow to call those sonnets which are of fourteen lines, every line containing ten syllables. The first twelve do rhyme in staves of four lines by cross metre, and the last two rhyming together do conclude the whole.12

What Gascoine confirms here, and what is clearly borne out in the work of Drayton and Shakespeare and others, is that the sonnet gradually becomes established in England as a form with particular structural characteristics: not just a short poem of fourteen lines, but one with strong internal dynamics, deriving from strictly observed line length and rhyme scheme, and from the interplay of its constituent parts. To appreciate the special appeal of the sonnet most fully, and to measure its ambitions and achievements, we need to regard it both synchronically (identifying common and persistent structural features) and diachronically (observing how it evolves under changing social conditions).The fascination of the sonnet for readers and writers alike is that it calls for discipline and constraint while simultaneously inviting endless permutation and innovation.

The politics of the sonnet

The aim of this book is to provide the first comprehensive study of the sonnet in English from the Renaissance to the present, both attending to the distinctive structural qualities of the sonnet as demonstrated in specific examples by notable poets, and exploring the ways in which the sonnet form registers the clashes and collisions of history, from the English Civil War and the revolutionary politics of the Romantic period to the First World War and the violent conflicts of the modern world. It considers the sonnet in terms of attitude, address, and adaptability. It asks in relation to attitude what kind of structural identity the sonnet has. What ways of thought and feeling are characteristic of the form? What can it do that the limerick or the villanelle, for instance, might not be able to accomplish? The book further explores, in terms of address, how the sonnet approaches its subject matter. How does it speak about particular kinds of experience, and how does it appeal to its listeners? The principal concern of the book is with the adaptability of the sonnet, with its prolonged use and persistence over several centuries, and with its transmission as a poetic form across geographical, as

12. George Gascoine, ‘Certain Notes of Instruction’, Elizabethan Critical Essays, ed. Gregory Smith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1904), vol. 1, p. 55. Spelling has been modernized.