Acknowledgments

Each page of this book is marked by an insurmountable debt, not least of which is owed to my advisers at the University of Chicago, where I began this project as a dissertation. First and foremost, I wish to thank Dan Morgan. Working with Dan has proven to be an irreplaceable part of my development as a scholar. It is only with the aid of his intellectual generosity, his curiosity, and his confidence in my intuitions that this book could have even been conceived. At the same time, his insistence on clarity and argumentative rigor taught me the value of checking my intuitions, stepping outside of myself, and considering my reader. Put simply, any intellectual development I’ve had as a scholar I owe to Dan’s devoted guidance. David Rodowick, meanwhile, kept me afloat with his unwavering enthusiasm and good spirit; so much of this project’s development was fostered by his reliable encouragement and attention to detail. To Tom Gunning I owe a model for endless intellectual curiosity and a way of seeing the wonder in the everyday; conversations with him always reminded me of what drew me to film studies in the first place. From Noa Steimatsky I learned to always question my assumptions and trust my instincts that things are often more complex than they seem; her commitment to maintaining the integrity of her aesthetic experiences has provided a valuable model for my own writing. I could not have asked for a more thoughtful, generous, and inspiring group of people to have worked with. Moreover, I cannot think of a group of scholars whose work I admire more. This book in many ways has emerged directly from their ideas and ways of thinking about moving images; it merely continues a conversation that they have started.

The book has been profoundly shaped by conversations with numerous colleagues I’ve had the fortune of working with and learning from over many years, and whom I feel lucky to have as friends. Mikki Kressbach has read every page of this book and has offered generous feedback at every stage of writing; she reminds me to never take myself (or academia) too seriously. Ryan Pierson has guided my intellectual development through his personal encouragement and through the model provided by his own work. Conversations with him never fail to inspire me, and he’s been a generous reader of the manuscript since its earliest stages. Ellen McCallum has become a sharp critical reader of the book in the later stages of the writing and revision process. She reminded me of the joys of theory at a time when I really needed it. Hoi Lun Law has been a wonderful interlocutor about films and aesthetic theory, and a generous reader of the manuscript. Dave Burnham has proved a reliably stimulating intellectual companion about all topics; conversations with him almost always clarify my thinking. Hannah Frank provided invaluable guidance and inspiration, especially at the earliest stages of the book; I hope the pages that follow evidence at least a fraction of how much I’ve learned from her.

Acknowledgments

I am also immensely grateful to colleagues and faculty I met as a graduate student at the University of Chicago. Richard Neer has proved time and again to be a tremendous wellspring of ideas and an enthusiastic interlocutor, and Salomé Skvirsky has generously offered a keen and critical eye to drafts of my work and has made innumerable insights in workshops and in conversation. The book has also benefited from conversations with Robert Bird, Dominique Bluher, Allyson Nadia Field, Patrick Jagoda, James Lastra, Takuya Tsunoda, and Jennifer Wild. Most significantly, I owe a special debt to a peer writing group founded and organized by Mikki Kressbach, and its longest-lasting members, Nicole Morse and Will Carroll; they’re three of the best readers one could ask for. Over a period of many years (and still going strong), the writing group quickly became much more than a forum to share and critique work in progress; it became a space of intellectual community, a haven of mutual encouragement, and at times a much needed venue for blowing off steam. This book has also been shaped by all of the colleagues who have participated in this group throughout the years: Hannah Frank, Matt Hubbell, Ian Jones, Tyler Schroeder, and Ling Zhang. I am also indebted to the University of Chicago’s workshop system, particularly the Mass Culture Workshop. I wish to thank the many graduate student participants for their generous and insightful feedback, especially Chris Carloy, Matt Hauske, Zain Jamshaid, Katerina Korola, Amy Skjerseth, Nova Smith, Pao-Chen Tang, Artemis Willis, Panpan Yang, and Tien-Tien Zhang. I am especially indebted to Nicholas Baer, Ian Jones, Noa Merkin, Sabrina Negri, James Rosenow, Aurore Spiers, and Shannon Tarbell, who’ve lent numerous insights to the book over the years and whose friendships I value dearly.

At the University of Pittsburgh, my early graduate school education was shaped by seminars with a range of faculty in the Film Studies program. Jane Feuer, Randal Halle, Marcia Landy, Adam Lowenstein, Neepa Majumdar, and David Pettersen deserve special mention. Much of the enthusiasm that marked my first two years of graduate school and which propelled me throughout the remaining years I owe to them. The graduate student community at Pitt, especially, left an indelible impression. In many ways, I was brought up as a scholar in the halls of the Cathedral of Learning and huddled on the second floor of “The Cage.” I am especially thankful to Katie Bird, Jedd Hakimi, Jeff Heinzl, Ryan Pierson, John Rhym, and Kuhu Tanvir.

More recently, at Michigan State University, I wish to thank Joshua Yumibe and Justus Nieland for their guidance, Lily Woodruff for her friendship, and Mashya Boon for her intellectual enthusiasm and encouragement. At the Scholarship in Sound & Image at Middlebury College, warmly known as “video camp” to its participants, I received valuable feedback on a videographic version of Chapter 4 from Christian Keathley, Jason Mittell, Catherine Grant, Liz Greene, and Corey Creekmur. I am deeply thankful for their mentorship. At conferences I’ve received valuable feedback and encouragement from Philippe Bédard and Scott Richmond, whose work has and continues to be crucial for this book. And at Oxford University Press, I am thankful for the guidance of editor Norm Hirschy, and for the two anonymous readers; their

sharp attention to details of argument and their insightful suggestions have improved my own thinking in important ways.

To my family I owe a special gratitude. My parents, Caryl and Terry Schonig, have demonstrated unflagging devotion to my academic career. Their love and support have fueled everything I’ve accomplished as a scholar. My brother, Jared Schonig, has always been enthusiastic and supportive. He’s also served as a companion movie lover from before I can remember. I credit him (as he insistently credits himself) with first turning me on to movies. This book informally began, and will indeed persist, simply through the ritual of going to the movies with my family. Finally, I want to thank Ilana Fischer, who has provided a spark of love and laughter and support during the final stages of the writing process. Her love sustains me in all things.

Chapter 1 is a revised and expanded version of “Contingent Motion: Rethinking the ‘Wind in the Trees’ in Early Cinema and CGI,” Discourse 40, no. 1 (2018): 30–61.

Parts of Chapter 4 appear in “Seeing Aspects of the Moving Camera: On the Twofoldness of the Mobile Frame,” Synoptique 5, no. 2 (2017): 57, and “Locomotive Views: Lateral Movement and the Flatness of the Moving Image,” in Deep Mediations: Thinking Space in Cinema and Digital Cultures, ed. Karen Redrobe and Jeff Scheible (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021).

Chapter 5 is a revised version of “The Chained Camera: On the Ethics and Politics of the Follow-Shot Aesthetic,” New Review of Film and Television Studies 16, no. 3 (2018): 264–294, and a videographic version of the chapter was published as “The Follow Shot: A Tale of Two Elephants,” [in]Transition: Journal of Videographic Film and Moving Image Studies 5, no. 1 (2018).

Parts of the Conclusion appear in “The Haecceity Effect: On the Aesthetics of Cinephiliac Moments,” Screen 61, no. 2 (2020): 255–271.

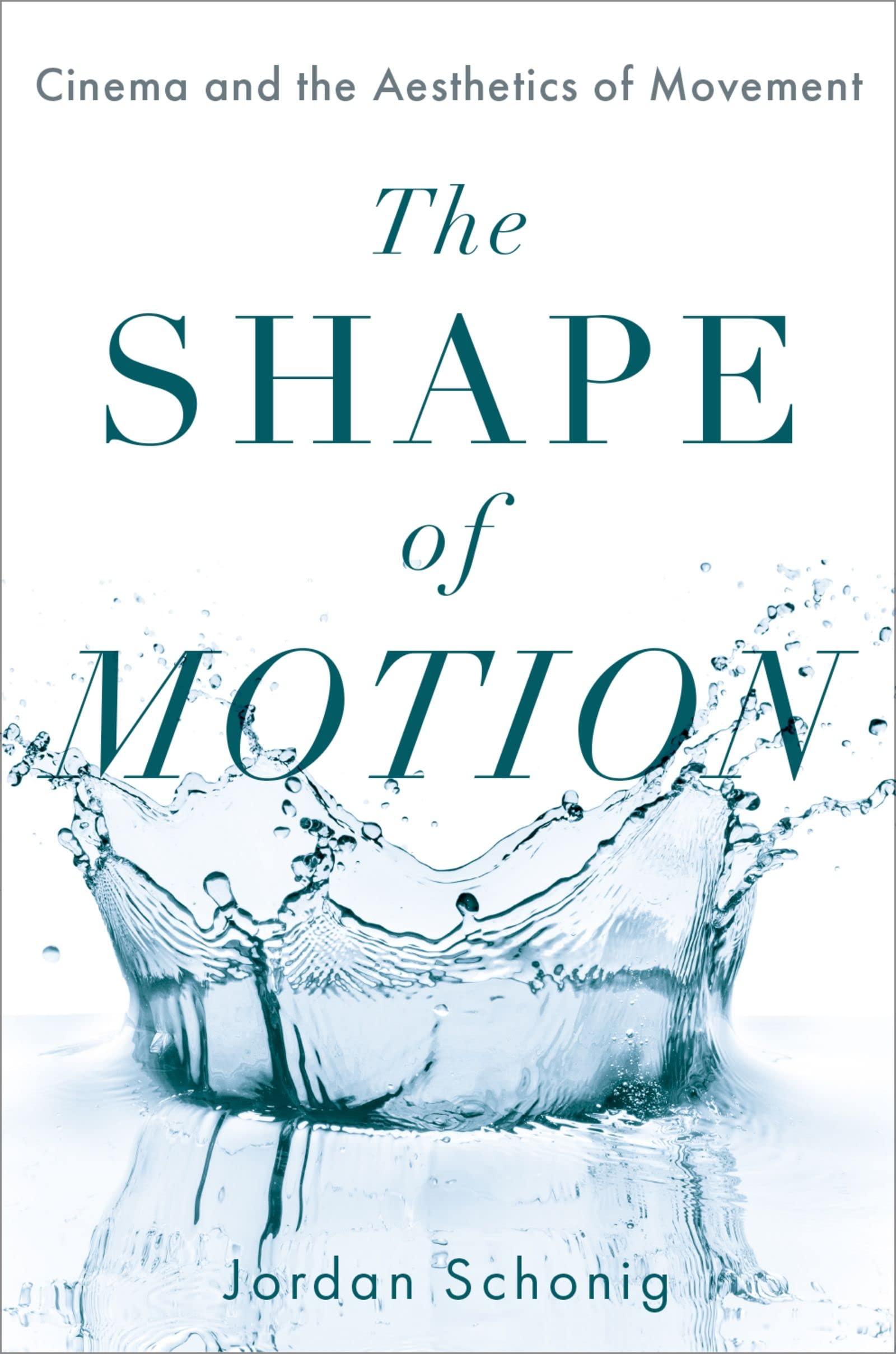

Moving toward Form

The Problem of “Movement”

We speak of change, but we do not think about it. We say that change exists, that everything changes, that change is the very law of things: yes, we say it and we repeat it; but those are only words, and we reason and philosophise as though change did not exist.

Henri Bergson1

That movies move is one of the most basic facts about the medium. Moving images involve movement; motion pictures involve motion; cinema involves kinesis. Yet, it is difficult to account for particular achievements of cinematic motion without simply invoking the power of “movement” itself. One doesn’t have to go far to find examples. David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson invoke Star Wars: Attack of the Clones’s “futuristic landscapes teeming with dynamic movement”;2 Timothy Corrigan and Patricia White note the “breathtaking visual movements” of Avatar and describe the carnival ride scene in 400 Blows as a “celebration of movement.”3 Maya Deren claims that her A Study in Choreography for Camera was “an effort to isolate and celebrate the principle of the power of movement.”4 And writing on Bela Tarr’s Damnation, Daniel Frampton notes that a link between character and setting is made “through the movement of film and the movement of our memory.”5

Utterances of this type invoke “movement” in order to characterize all matter of cinematic phenomena. Like aesthetic judgments, they indicate the presence of a feeling or the quality of an experience but find it difficult to put into words. In their ubiquity, such utterances seem to insist that the “movement” of people, things, and cameras should not be subsumed under a vocabulary of representation or narrative content, that the very movements that constitute the world on screen must be isolated for analysis, as with light or color or sound. And yet, they run up against movement’s ineffability, pointing to movement itself, despite knowing very well that everything on the screen moves. If, as Tom Gunning has suggested, cinematic motion is “the Freudian repressed subject of film theory,” these utterances might be considered slips of the tongue, film studies’s parapraxes.6 We accept them and pay them no notice, but they testify to an invisible problem. When it comes to discussing or describing or

analyzing the movement on screen in a moving image, it is difficult to do more than point to the screen and exclaim the power of movement in general.

The recent spate of interest in cinematic stillness is a case in point. An opposition between stillness and motion in cinema is often presumed, and is indeed an attractive heuristic for encouraging deserved attention to a pervasive cinematic aesthetic, but it’s a false dichotomy.7 When speaking of a moving image, stillness is not opposed to movement, but rather is a kind of movement. It is because of this distinction that you can point to stillness in a scene, in the composition of a frame, in an actor’s posture. But you can’t point to “movement” on screen in the same way. Pointing to movement in general is only a meaningful gesture in very particular circumstances, such as at the Salon Indien du Grand Cafe in 1895, where animated movement itself was miraculously breathed into a projected image before a stunned audience, or during a film like Chris Marker’s La Jetee (1962), composed of a series of static images that astonishes us with the sudden appearance of movement. In most of the objects we call moving images, however, what would be the purpose of pointing to movement itself, other than to reiterate a self-evident condition of the moving image?

Nevertheless, film theorists and critics persistently declare movement, celebrate movement, and reflect on the nature of movement. From the French and German theorist-practitioners of the 1920s who celebrate movement as the essence of the cinematic medium,8 to Christian Metz’s claim that motion itself is responsible for cinema’s “impression of reality,”9 to Vivian Sobchack’s analogy between cinematic motion and the “essential motility” of our embodied subjectivity,10 film theorists have often sought to identify the essential significance of the movement of the moving image. More recently, the prevalence of accounts of “becoming,” “emergence,” and “mobility”—filtered through the increasing influence of process-oriented philosophers like Henri Bergson, Gilles Deleuze, and A. N. Whitehead—has paved new avenues for valuing cinematic motion without analyzing cinematic motion.11 Cinematic motion is celebrated as an emblem of openness, change, and fluidity, without a commensurate attention to the specificity of movement on screen.

There’s a long-standing problem here. Though invocations of movement in film criticism, phenomenologies of movement in film theory, and Deleuzian film philosophy testify to the significance of movement in our experience of the moving image, they all confront the dead end of generality. Cinema’s property of movement—like the screen’s two-dimensionality or the photochemical aspects of celluloid—does not determine a singular form of aesthetic experience. The possibilities of movement on screen are incommensurate with the abstraction of movement as such. To be sure, any serious critical engagement with the aesthetic effects and significations of a film emerges from the particularities of cinematic movement; film analysis by definition describes the products of movement on screen. But the continued insistence on abstracting motion for theoretical study shouldn’t go ignored. What we need, then, is a vocabulary for theorizing the movement of the moving image without resorting to the mere invocation or theorization of movement in general and, conversely, without subsuming movement under the purely representational language of “actions” and

“events.”12 In short, what we need is a means of talking about the myriad ways in which movements move.

The Shape of Motion proposes a method for analyzing movement according to the forms that movement takes on screen. By “form,” I simply mean the spatiotemporal arrangement of phenomena, that is, the general organizedness of things as they appear to our senses.13 What I call “motion forms,” by extension, are generic structures or patterns of motion—in a word, shapes of motion—perceptual wholes mentally stitched together through time. In everyday life, we ordinarily (and unconsciously) use motion forms to simply identify things in the world, such as when we notice a friend from behind by the familiarity of their gait.14 Likewise, in the cinema, motion forms can be gestural idiosyncrasies unique to a single actor, like Charlie Chaplin’s signature walk or the way Humphrey Bogart smokes a cigarette. Motion forms also include the characteristic onrush of space that produces the impression of moving into the depth on screen (produced with or without a moving camera). Motion forms are at work when we discern and distinguish post-production techniques like dissolves, fades, and wipes, or in-camera effects like dolly zooms or rack focus. They can be analogically recorded, like the recognizable quaking of tree leaves in the wind, or digitally generated, like the “morph” effect or “bullet time.”15 And they can even be sustained across an entire moving-image technology, as with what’s been called the “soap-opera effect” shared by high-frame-rate (HFR) projection and motion-smoothing digital televisions.16 In all such cases, a motion form is any perceptual unity constituted from a succession of visual sensations. While previous attempts to taxonomize types of cinematic motion have resulted in categories defined by the kinds of objects that move— the movement of people, the movement of the camera, the movement of the camera’s lens (i.e., zooms), and the movement created by editing17 motion forms are determined by perceptual structures rather than ontological ones. They constitute a perceptible way of moving—a pattern, a structure, a shape, a whole—synthesized within a visual field of moving phenomena.

Importantly, motion forms denote both the sense of unity synthesized across a single continuous instance of movement and, more crucially, the sense of unity perceived across distinct instances of movement that bear a formal similarity. This very activity of grouping seemingly disparate on-screen moving phenomena into patterns, shapes, and structures, i.e., forms, is both the method and subject of my investigation of the phenomenology of cinematic motion. Thus, instead of constituting a definitive theory of cinematic motion, motion forms function as a heuristic for theorizing phenomenologies of cinematic motion without lapsing into essentialism. In fact, insofar as there is something called “the phenomenology of cinematic motion,” I claim that such a phenomenology can only be understood according to the inexhaustibly various forms through which cinematic motion manifests itself.

Just as Stanley Cavell in The World Viewed argues that the “ontology” of any artistic medium, such as film, cannot be understood prior to engaging with particular instances of that medium, the “phenomenology” of cinematic motion cannot be understood prior to an engagement with the particular forms that it takes.18 The aesthetic

possibilities of cinema’s forms of motion just are the phenomenological properties of cinematic motion. And by extension, such possibilities just are the properties of what many film theorists in the age of digital cinema are now more than ever referring to as “the moving image.” This phenomenological way of thinking pushes against the flurry of ontological arguments about cinema made in the wake of the digital turn, which perpetuate a basic problem fundamental to much classical and contemporary film theory: taking the aesthetic properties of the movies as a direct function of the physical properties of their media.19 In fact, a good deal of film theory’s interest in cinematic motion attends not to the movement on screen but to the physical apparatus creating the “illusion” of motion from the rapid succession of still images.20 But as the study of “film” is becoming supplanted by the study of “moving images,” and the technological apparatuses responsible for cinematic motion are becoming more diverse and mechanically illegible, the task of accounting for the array of experiences afforded by cinematic motion takes on a new theoretical urgency. Instead of another definitive ontology of the material medium or an ontology of movement-in-general, I argue that the moving image demands phenomenological accounts of what has always been on the screen but nevertheless eludes us: the many forms of movement we apprehend with our senses.

The central aim of this book, then, is to demonstrate how a phenomenological orientation toward forms of cinematic motion occasions a significant rethinking of some of film theory’s most persistent assumptions about the nature of cinematic experience. Theories of cinema oriented around the ontology of photography (Andre Bazin, Siegfried Kracauer), the metaphysics of temporality (Gilles Deleuze), the phenomenology of embodied subjectivity (Vivian Sobchack, Jennifer Barker), and the ontology of digital technology (Lev Manovich, David Rodowick) have provided influential explanations for many aspects of cinematic experience, from early spectators’ attraction to the wind in the trees to the experience of duration in postwar realist art cinema.21 But such explanations have relied on severely restricted accounts of cinematic motion. In these accounts, motion remains either an unchanging variable (a mere vestigial appendage) or conversely a grand hypostatized entity (a central but inflexible essence). Without robust concepts for the particular forms of motion experienced across various milieu, some of our most basic certainties about cinematic experience fall prey to a number of theoretical dead ends and aporias.

In order to not only unearth those aporias but also produce new theoretical models in their place, each chapter conceptualizes a single motion form: contingent motion (the chaotic movements of formless objects like water, dust, and smoke captured on screen); habitual gestures (everyday bodily movements like walking or reaching that display the pre-reflective autonomy of the body); durational metamorphoses (slow, incremental changes that result in profound transformations, such as the movements of clouds or the darkening sky); spatial unfurling (an effect produced by certain camera movements, such as lateral tracking shots, that suppress the illusion of bodily movement); trajective locomotion (an effect produced by camera movements that follow characters on foot from behind); and bleeding pixels (an effect produced

by digital compression artifacts, used expressively in a glitch art technique known as datamoshing). Each motion form under consideration takes on phenomenological significance at particular moments in cinema’s history, telling an untold story of cinematic experience. Making a case for the formal generality and phenomenological uniqueness of each motion form can lead us to question the assumptions of some of film theory’s most persistent intuitions.

Only by giving form to movements—attributing a particular shape, a character, a quality—can we begin to see movements in their formal specificity. And only by seeing particular movements in this way can the “phenomenology of cinematic motion” become available to theoretical and critical discourse. Only when we see that fluttering leaves, rippling waves, and swirling dust share a sense of chaotic formlessness can we begin to rethink the assumptions about photography and contingency that have explained why early spectators were attracted to such phenomena. And only when we see the similarity shared by the rushing landscape in a passenger window, the lateral camera movements in Leos Carax’s Mauvais Sang, and the gyroscopic spins of Michael Snow’s La région centrale can we begin to question the intuition that a moving camera virtually moves the spectator through a film’s world. Bridging motion forms across such disparate examples—from different kinds of represented phenomena, to different genres and modes of cinema, to even different media (analog and digital)—allows us to see ways of moving where we only saw representations, to see glimpses of repetition where we only saw difference.

This kind of seeing, which apprehends not just movement but inexhaustible kinds of movements, encourages a different mode of theorizing cinematic experience than most film theoretical models offer. Bringing form and movement together, we discover that “movement” is more than a mere property of the “moving” image. Movement is whatever form that it takes. Taking this as a guiding principle, film theory becomes considerably less secure in its object of study, forgoing long held intuitions about what the photographic moving image is. But what it offers in return is an occasion to incorporate the undeniable wonder, astonishment, and pleasure of beholding movement of all kinds—a pleasure that precedes the cinema and persists outside of it—into the very activity of doing film theory.

Perceiving Form

Movement is the result of a feeling in one thing of strong difference from other things. Movement is always one thing moving away from other things—not toward. And the result of movement is to be distinct from other things: the result of movement is form.

—Len Lye22

So far, I have cast the project of bringing “movement” and “form” together as a means of addressing a range of problems surrounding the theorization of cinematic motion.

But how did movement and form come to be separated in the first place? Though the terms “form” and “formalism” are by no means strangers to film studies, there remains a deep intuition that form is a spatial (and static) rather than a temporal (and mobile) concept. In an insightful footnote from her essay “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag laments such an intuition: “One of the difficulties is that our idea of form is spatial (the Greek metaphors for form are all derived from notions of space). This is why we have a more ready vocabulary of forms for the spatial than for the temporal arts.”23 We can trace the logic of Sontag’s observation back to Henri Bergson’s conceptual opposition between movement and form: “In reality, the body is changing form at every moment; or rather, there is no form, since form is immobile and the reality is movement. What is real is the change of form: form is only a snapshot view of a transition.”24

Film studies has inherited the philosophical intuition that form is primarily spatial—e.g., the arrangement of objects in the frame—or that it necessitates the spatialization of temporal experience—e.g., the ordering of shots in a montage sequence, the structure of narrative events. Two of the leading formalists in film studies, David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, for example, often examine audiovisual forms as strategies for guiding spectators through the narrative logics of actions and events, causes and effects. As with the analysis of narrative form, studying form in film generally requires that we halt its temporal flow: “formal” analysis conjures notions of mapping plot events, segmenting sequences by shots, or freezing stills to analyze the composition of the frame.25 In short, an attention to form suppresses the immediate temporal engagement with the flow of moving images to create spatialized units of analysis.26 What’s more, an attention to form almost always entails analysis in the etymological sense of the word breaking things apart, distinguishing the constituent elements, extracting pieces from immediate experience. Rarely does an attention to form entail an accretive activity—building, bridging, synthesizing forms across a field of perception.

A phenomenological approach to form, however, offers a different conception of the relation between form and movement.27 For Maurice Merleau-Ponty, for example, perception relies on a gestalt structure, configuring the manifold of sensible stimuli into coherent forms. Drawing on Gestalt psychology, Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology of perception opposes classical psychological models, as well as empiricist philosophical models of perception that view the perceptual field as an undifferentiated mosaic of atomistic sensations.28 For Merleau-Ponty, the phenomena of the world are themselves “pregnant” with “form.”29 On this view, we don’t analytically decipher a round object from the buzzing confusion of “red” sensations; we simply see a red ball. The form stands out against its background immediately and spontaneously. Beyond such simple tangible objects, however, forms can also manifest as any number of complex groupings of phenomena in space and, more importantly, in time

Temporal gestalts are unified forms constituted by their separate parts that unfold in time; the experience of a melody, for example, does not reside in the sum of its discrete

tones but in the experience of the sequence itself as a temporal whole. 30 When temporal gestalts are of a visual rather than an auditory nature, they name those forms or wholes that are synthesized from a visual array of moving phenomena. It would be a great mistake, Merleau-Ponty writes, to conceive of “the movement of visible objects” as “the mere transference from place to place of coloured patches which, in the visual field, correspond to those objects.”31 “In the jerk of the twig from which a bird has just flown,” he continues, “we read its flexibility or elasticity, and it is thus that a branch of an apple-tree or a birch are immediately distinguishable.”32 In this fleeting moment, a unified shape or character of movement simply comes together and is seized upon in an unreflective perceptual judgment; that what I see is an apple tree rather than a birch is here wholly determined by the ephemeral form of a movement rather than a texture, shape, or color.33

Merleau-Ponty illustrates this general principle further, and more radically, in his account of the research of experimental phenomenologist Albert Michotte:

Albert Michotte from Louvain demonstrated that, if lines of light move in certain ways on a screen, they evoke in us, without fail, an impression of living movement. If, for example, two parallel vertical lines are moving further apart and one continues on its course while the other changes direction and returns to its starting position, we cannot help but feel we are witnessing a crawling movement, even though the figure before our eyes looks nothing like a caterpillar and could not have recalled the memory of one. In this instance it is the very structure of the movement that may be interpreted as a “living” movement. At every moment, the observed movement of the lines appears to be part of the sequence of actions by which one particular being, whose ghost we see on the screen, effects travel through space in furtherance of its own ends.34

In this example, form might name the emergence of a perceptual unity—a “living movement,” a “crawling movement,” a “ghost”—from mere lines of light on a screen. In Merleau-Ponty’s words, “it is the very structure of the movement”—what I am calling the form of the movement—“that may be interpreted as a ‘living’ movement.” Form and movement here are not opposed; rather, motion forms emerge from and within the perception of movement. What’s more, these motion forms are demonstrably distinct from and unrelated to the spatial forms—here, lines of light—that move. What, then, would it look like to perform a traditionally conceived formal analysis of the experiment Michotte set up for his subjects? An attempt, for instance, to map or segment screenshots within a spatial juxtaposition, or to analyze the composition of the lines as they relate to each other in a spatial configuration, would destroy the experience of form. Form is not only a product of analysis or reflection, something that must be deliberately excavated from beneath the immediacy of “content.”35 Form is also an intrinsic part of the flow of temporal experience. “The perception of forms,” Merleau-Ponty writes, “understood very broadly as structure, grouping, or configuration should be considered our spontaneous way of seeing.”36 Constantly emerging

and dissipating, coming together and breaking apart, forms organize our experience of movement both in the world and in a moving image. Just as for Immanuel Kant “intuitions without concepts are blind,”37 for Merleau-Ponty the perception of movement without the unreflective immediacy of forms is not perception at all.

What I call motion forms, then, in the most ordinary sense of the term, are not new to the study of film—or, for that matter, to everyday life. As in MerleauPonty’s example, a motion form is what allows us to unconsciously distinguish a birch tree from an apple tree simply by the movement of its branch. Likewise, in a film studies classroom, we might use the same basic perceptual faculty to teach students how to distinguish between a zoom and a tracking shot. Or, when watching a film, motion forms inconspicuously guide our comprehension of what we’re seeing, as when a seemingly abstract shape on screen becomes recognizable only when it begins to move, or when the movements of a photorealistic figure reveal that it is computer generated. Motion forms are as much already an integral part of the field of perception—both cinematic and ordinary—as they are extracted from “formal analysis.”

It may seem like the perceptual definition of form I’m adopting is simply a different concept than what is often meant by “form” in film studies. But this is not precisely the case. In both usages, form names the spatiotemporal arrangement of phenomena.38 The use of “form” in film studies, however, has become saddled by assumptions inherited from a range of philosophical traditions. Much of the limitations on what counts as “form” in film studies can be attributed to not only the false intuition that it is a spatial rather than a temporal concept, but also that the contemplation of form is restricted to the domain of artistic choice.39 In most of the fine arts, such as painting, sculpture, music, and literature, the work of “form”—the spatiotemporal arrangement of the artwork is generally attributed to the hand of the artist (or group of authorial agencies) that does the arranging.40

In the photographic moving image, however, as with photography more generally, the location of form as authored or deliberately shaped is always at issue. As a result, theorists and critics of cinema tend to restrict their identification of form to the kinds of cinematic movements that seem deliberately shaped by an authorial force. The movements between shots (i.e., editing) or the movements of the camera are unambiguously formal characteristics of the image because they are discernibly shaped, just as in sculpture the form of a human body is chiseled out of the matter of clay.41 But what of the involuntary micro-gestures of actors or the wind in the trees? This is where difficult distinctions arise. Considered “unplanned” by the filmmaker, such movements are condemned to the critical purgatory of photographic “contingency” and cinephilic “excess” where aesthetic form is nowhere to be found.42 The movements of the environment and the micro-gestures of actors may in fact present difficulties for intuitions about formal meaning inherited from philosophies of art, but they are precisely the kinds of phenomena that can be reconsidered as perceptual forms of motion (as I do in Chapters 1 and 2) that offer their own logics of visual pleasure.43 Considered as such, the excesses endemic to cinematographic motion

become more than mere tokens of the medium; they become available to the principle of perceptual organization, i.e., form, that is always at work between spectator and screen. Therefore, in Chapter 1, I argue that early spectators’ fascination with the wind in the trees can be understood as an aesthetic encounter with a particular form of motion whose pleasures can be explained neither solely as a function of cinema’s technological novelty nor as a function of authorial choices. Rather, many of its pleasures are consistent with a history of aesthetic experience that long precedes the moving image, that is, a history of aesthetically engaging with forms of motion in the natural world. Though authorial agents are of course largely responsible for cinematic form, cinema’s indiscriminate registration of the world in motion can manifest forms that exceed the choices of filmmakers and provoke their own kinds of significance. Indeed, everything that is captured on screen, regardless of how it is captured or generated, has the potential to be grouped, patterned, and structured into forms in our perception.

Part of my strategy for isolating such forms of motion within reservoirs of cinematic excess is to juxtapose narrative films with non-narrative and experimental films and videos, especially works in which perceptual forms are explicitly under visual investigation. The phenomenological significance of the flatness and rhythm of a lateral tracking shot in Carax’s Mauvais Sang, for example, becomes newly legible in light of the overt two-dimensional abstractions in Snow’s La région centrale and Ken Jacobs’s Georgetown Loop, films in which the perceptual conditions of camera movement are under explicit investigation The film theoretical significance of gestural micromovements in Robert Bresson’s Mouchette becomes clear in light of Martin Arnold’s pièce touchée, which quite literally breaks down a single continuous gesture into tiny intervals of stuttering movement. And the forms of motion embedded in the visual chaos of everyday compression glitches become graspable in light of works of datamoshing glitch art, which occasion the aesthetic contemplation of these generally overlooked malfunctions. Operating outside the structuring logics of narrative cinema, such experimental films and videos model modes of spectatorship that attend to patterns and structures of movement and the medium-specific questions generated by them, thereby priming the eye to shift its aspectual attention to the forms of motion that suffuse all moving images, narrative and otherwise.

Following the tradition of thinkers like Merleau-Ponty, Ludwig Wittgenstein, the Gestalt psychologists, and Immanuel Kant, I take form to be as much a perceptual concept as it is an artistic one, as much a temporal concept as it is a spatial one. Untethered by rules or criteria, forms can strike us anywhere and across many phenomena. They can be found within static objects, and they can emerge from fields of movement. Indeed, by bringing form and movement together, we have to forgo some of the charms of celebrating movement as the essence of cinema—its ontological relation to openness and becoming, flux and fluidity. Motion forms, by definition, limit, constrain, and bind. They create boundaries. But they also allow us to do things. Motion forms, like forms more generally, are tools for thinking. This book aims to use this ordinary faculty of human perception as a tool for giving movement its proper

place in film theory. Linked to form, movement becomes less ephemeral but newly legible.

The Strangeness of Cinematic Motion

[The] film’s movement transforms everything.

Albert Laffay44

While motion forms are integral to both cinematic and natural perception, movements on the screen and movements in the world, this book is committed to exploring motion forms that bear out the phenomenological uniqueness and strangeness of the photographic moving image. Such a strangeness was indeed most apparent in the years of early cinema, when spectators were astonished by the very technological novelty of an animated photograph—its uncanny blurring of presence and absence, life and death, reality and illusion—but this book is committed to the principle that such strangeness transcends its mere technological novelty. Such a strangeness, to borrow Gunning’s term, can be “re-newed”; as he reminds us, “the cycle from wonder to habit need not run only one way.”45

What this entails is a major aim of this book: to challenge the intuition that the photographic moving image automatically reproduces the natural perception of motion.46 This intuition undergirds many basic ideas throughout film theory, from claims about the inherent realism of the cinematic image, to analogies between the moving camera and human locomotion, to the impetus to locate cinema’s artistic potential in montage. Such an intuition even lurks in places we might least expect, such as in the work of Deleuze, who otherwise devotes his entire twovolume study of cinema to the medium’s capacity to produce new forms of perception and thought. In the beginning of Cinema 1, for instance, Deleuze intentionally excludes the cinematic movement “of people and things” from his concept of the “movement-image.”47 Identifying the birth of cinema proper with the emergence of editing and camera movement (and by extension, narrative), Deleuze asks, “Is not cinema at the outset forced to imitate natural perception?”48 Deleuze’s exclusion is not a mere historical oversight, but is rather symptomatic of an intuition about the location of aesthetic form in cinema, about what makes “cinema” as an art distinct from cinematographic recording as a technology.49 By this familiar logic, cinematographic recording merely transposes movement from the world in front of the camera to the screen, while “cinema” proper begins when that recording is discernibly manipulated.

What Deleuze overlooks—or what he brackets for the sake of argument—is the phenomenological strangeness of the moving image embedded within its very effortless perceptual realism. In other words, cinematographic recording does not merely transpose the movements of the world in front of the camera; it transforms them. The motion forms I examine, and the phenomenological reflection they demand, are

intended to revive this sense of transformation, to instill a sense of wonder at cinematic motion where habits of seeing have dulled the senses.

By this I do not mean that the motion forms I examine present phenomena that can move in strange and unearthly ways, defying the laws of physics and the bounds of the imagination. The cinema is now more than ever capable of picturing impossible forms of movement and time: from “bullet time,” to virtual cameras that move through walls, to gravity-defying creatures of computer-generated imagery (CGI). In fact, cinema has always been capable of extraordinary modulations of movement, from George Méliès’s tricks films to J. C. Mol’s mesmerizing time-lapse films, and early theories of film certainly took notice. Beginning in the silent era, though decades after cinema’s inception, what Malcolm Turvey has dubbed the “revelationist” tradition of classical film theory rightly celebrated cinema’s capacity to defamiliarize and transform objects on screen by attending to its extraordinary manipulations of movement, time, and space, from Jean Epstein and Siegfried Kracauer’s interest in slow motion, to Dziga Vertov’s interest in reverse motion, to Bela Balazs’s enthusiasm for the close-up.50 Indeed, the extraordinary motion forms therein are worthy of study. But we must avoid conflating cinema’s capacity for wondrous representations with the wonder of cinematic representation. Foregrounding these extraordinary techniques as the emblems of cinematic motion’s otherness risks perpetuating the fallacy that “ordinary” cinematographic recording simply reproduces the natural perception of motion. To flat out identify the uniqueness of cinematic motion with such techniques risks diluting the fundamental strangeness of the photographic moving image.

The kinds of objects that photographic moving images are—at once a lifelike world of movement and a detached image—are strange, category-blurring things in and of themselves, even before the development of special effects, temporal manipulations, and narrative techniques. It is in this spirit that I draw on those elements of the revelationist tradition that strive to articulate cinematic motion’s fundamental transformation of what it records, which we can find in aspects of Epstein’s notion of photogenie, Balazs’s interest in moving bodies on screen, Kracauer’s fascination with fluttering leaves and swirling dust, and Bazin’s writing on the uncanniness of cinema’s temporal repeatability. It is in these writings of the classical film theorists, among others, that the fact of a moving image remains a source of wonder and always an unsettled question. For example, when Epstein writes that “crowd scenes in the cinema produce a rhythmic, poetic, photogenic effect” because “the cinema can pick this cadence up better than the human eye,” he seems to suggest that it is not cinema’s capacity to augment or manipulate the crowd’s motion, but to recontextualize it and extract it from the world, that grants us access to that movement’s formal qualities.51 Or, when Balazs writes that cinema is capable of “registering [the body’s] slightest motion,” and Kracauer writes that cinema is “uniquely equipped to render . . street crowds, involuntary gestures, and other fleeting impressions,” both suggest that the very fact of cinematographic recording is capable of a kind of detailed perception of moving phenomena, even without the augmentation of the close-up.52 And when Bazin condemns the documentation of death on film as an obscenity because “cinema has the