ForIsabelandJay

Preface

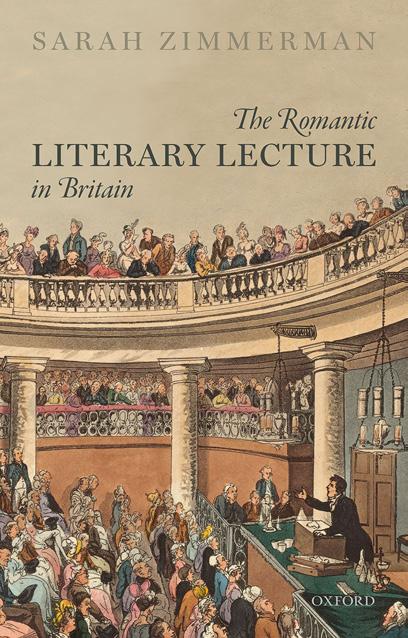

Thisbookbeganinthelectureroom.Oneofmy firstteachingassignments was “IntroductiontoLiterature,” acoursethatoftenenrolledhundreds ofstudentspersection.Isoonlearnedthatlecturesareatwo-waystreet. Mystudents’ presencewashighlycommunicative,notonlywhenthey askedquestionsandtooknotes,butalsoastheyshiftedintheirseats, gazedoutthewindow,orshuffledpapersasthehourtickedtoaclose. Ilearnedtoimprovise,workingfromdetailedoutlinesthatallowedmeto leaveapointwhenIwaslosingthemortoelaboratewhenittookhold. Icametorealizehowmuchthephysicalspacemattered howtheroom’ s atmospherewassetbyitssize,thekindoflightitreceived,whetherits seatswerebanked,andifamicrophonewasnecessary.Idiscoveredthat whilenoamountofplanningcouldguaranteeasuccessfullecture,Ifared bestbypreparingwithmystudents’ collectivecharacteristicsclearlyin mindandlaterrevisinginlightofwhereIhadthemandwhenIlostthem. Theirpresencechangedneitherthefactsofliteraryhistorynortheway thatIreadtexts,butwhathappenedinthosehallsinformedmycritical argumentsandtheversionofliteraryhistorythattheyheardfromme. LearningtolecturetaughtmesomethingelseasaRomanticist:thatwe werefailingtograspthefullimportofsomeoftheperiod’smostinfluentialliterarycriticism SamuelTaylorColeridge’slecturesonShakespeare andWilliamHazlitt’ s LecturesontheEnglishPoets (1818) byconsidering themsolelyasprintedtextsratherthanasoralargumentspitchedtolive audiences.RobertDarntonmakesthecasethattheperiod’sprintworks areinflectedbytheirparticipationina “communicationscircuitthatruns fromtheauthortothepublisher(ifthebooksellerdoesnotassumethat role),theprinter,theshipper,thebookseller,andthereader.” Thereader playsacrucialrole:that figure “completesthecircuitbecauseheinfluences theauthorbothbeforeandaftertheactofcomposition,” astheauthor “addressesimplicitreadersandhearsfromexplicitreviewers.”¹Inthe lectureroom,thecircuitofaffectistighterandquicker,andthecritical argumentsfarmoreimmediatelysusceptibletoinflectionbyresponsive auditors.Theperiod’spubliclecturesmakeespeciallyclearhowitsliterary culturewasshapednotonlybytheself-appointedarbitersofliterarytaste, butalsobythosewholistenedandread.

¹Darnton, KissofLamourette,111.

Lecturerspursuedtheirowncriticalagendas,buttheyneededtoengage theauditorswhocoulddetermineaseries’ fate.Independentseriescould collapsemidwayiftheystayedhome,andthescientificandliterary institutionsthatsponsoredtheseeventswouldnotinvitealackluster speakertoreturn.Successfullecturersthereforecouchedtheirarguments withparticularaudiencesinmind(sincedemographicsvariedbyvenue andurbanlocation),retooledargumentsinretrospect,andsometimes reactedinthemoment.Eventhosewhoeschewedextemporaneityand readaloudfromfullscriptshadtobeabletoimprovise.Lecturersdidnot fieldquestions,butauditorsclearlycommunicatedtheirpleasureordisapprobationin “[b]oosandcheers, ‘hear-hears,’‘ aye-ayes, ’ sniffsand yawns. ”²Whilelecturersaimedtoshapelisteners’ readinghabits,establish aliterarycanon,andburnishtheirownpublicprofiles,listenerswielded theirownconsiderableinfluence,notonlyinthelectureroom,butalsoat theprivategatheringsthatsometimesfollowed,wheretheycompared notesonthelecturers’ argumentsandperformances.Theconversations continuedinsolitudeandsilenceinauditors’ ownrooms,astheywrote lettersandautobiographicalaccountsrecordingwhattheyhadheardand whattheythought.Thuslecturers’ criticalargumentsreachedtheauditors gatheredaroundthem firstbeforeradiatingoutwardfromthatintimate exchangeinconversationscarriedonbydispersingcrowds,travelingin lettersnearandfar,resurfacinginnewspapernotices,lodginginprintand manuscriptsforfuturereaders.³

Auditors’ accountscontributetoa “historyoflistening” initiatedby musichistoriansandalsorespondtoMaureenMcLane’scallfor “afull literary-historicalaccountoftheuseandabuseoforality,oralcultures,and oralityeffectsbyandinwhatweconventionallycallBritishRomantic poetry.”⁴ TheRomantic-erapubliclectureonliteratureisavitalpartof thesehistories.Intracingthecareerofthisstillunderstudiedmedium,this bookhastwomainaims.Oneismethodological:addressinghowtotreat theselecturesashistoricalperformancesratherthansimplyaslinguistic texts,andconsideringtheconsequencesofdoingsoforunderstandingthe criticalargumentsmadeasfullyaspossible.Theotherishistorical:elaboratingtheparticularcaseofthepubliclectureonliteratureatthetimeand

²Forgan, “Context,ImageandFunction,” 102.

³TomWrighttakesupthisissueinregardtolyceumculture,observingthatthiskindof oratory “workedupondualaudiences:aprimarycrowdofliveauditorsandavastpotential secondaryreadershipforaccountsandtranscriptionsofspeeches” (LecturingtheAtlantic,20).

⁴ McLane, “BalladsandBards,” 426.SeeLeonBotstein’ s “TowardaHistoryof Listening” andDavidCavicchi’scallforahistoryof “[t]hereceptionofperformancesand works,thehistoryofmusicconsumption,thedevelopmentofaudiencepractices” (Listening andLonging,4).

placeofitsdecisiveemergenceasapopularmediuminearlynineteenthcenturyEngland.

Iundertakethe firsttaskinthe firstchapter,whichaimstoconsolidate thelessonsofabroadinterdisciplinarydiscussionthatconceptualizesthe problemof,andrecommendsbestpracticesfor,treatinghistoricalspeakingperformances.Biographers,editors,andscholarsinanarrayofdisciplines(thehistoryofscience,theaterhistoryandperformancestudies, literarystudies,musichistory,arthistory,mediastudies)havecometoa workingagreementthatthisnecessarilyspeculativeworkrequiresgatheringsurvivingdocumentsfrombothspeakersandlisteners,andsituating theseeventsintheirspecifictimesandplaces.Mynextfourchaptersadopt thatapproachintreatingthehistoricalperformancesoftheperiod’sfour mostprominentliterarylecturers:SamuelTaylorColeridge,JohnThelwall, WilliamHazlitt,andThomasCampbell.Iclosewithtwochaptersontheir auditors(includingJohnKeats,MaryRussellMitford,LadyCharlotte Bury,andCatherineMariaFanshawe)thatconsidertheirinfluenceon lecturers’ criticalargumentsbutfocusmorefullyontheirowncreative responsestowhattheyheardintheirpoems,letters,andotherwritings.

My first,methodological,aiminformsmysecond,oftreatingthe decisiveemergenceofliterarylecturingasapopularculturalmediumin earlynineteenth-centuryEngland,mostvisiblyinLondon.Thepublic lectureonliteraturecaughtthepopularimaginationand flourishedfor overtwodecadesintheinterlockingcareersoftheperiod’smostprominentlecturers.WhenThelwallventuredontotheprovincialcircuitinlate 1801asanelocutionlecturerheusedpoetryandproseindemonstrations ofreadingaloudandrecitation.AttheLondonschoolheestablishedin 1806hesoondevelopedseparateliteraryseries,includingoneonthe “EnglishClassics.” In1808Coleridgefollowedinhisfootsteps,launching alecturingcareeratLondon’sRoyalInstitutionthatwouldspanmore thanadecade.CampbellinturnfollowedColeridge’slead,debutingatthe RoyalInstitutionin1812andendingtherein1820afteracareerthat includedseriesinLiverpoolandBirmingham.HazlittlecturedonphilosophyattheRussellInstitutionin1812,buthewasalatecomeronthe literarylecturescene,offeringhis firstseriesattheSurreyInstitutionin early1818.By1820,allfouroftheperiod’sbest-knownliterarylecturershad retiredfromthemainstageofpubliclecturing.OnlyThelwallwouldreturn aftertemporarilyclosinghisschooltoresumefull-timepoliticalwork.⁵

⁵ HazlittgavetwolecturesinGlasgowatwhatwasthencalledtheAndersonian InstitutiononMay6and13,1822,the firstonShakespeareandMiltonandthesecond onThomsonandBurns.Theyweredrawnfromhisalreadytwice-deliveredandpublished LecturesontheEnglishPoets (1818).SeeJones, “HazlittasLecturer.”

Approachingtheliterarylectureasadistinctivemediumservestwo mainends.First,wemaymorefullygraspthecriticalargumentslecturers madebytreatingthemontheirownterms.Contemporariestookfor grantedthatlecturerstailoredthemforspecificaudiences.Forinstance, evenaquickglanceatnewspaperadvertisementsandreportsofColeridge’slecturesonShakespeareindicatesthathechosesometopics—“on LOVE andthe FEMALECHARACTER,asdisplayedbyShakespear” [sic] with particularlistenersinmind,inthiscasethewomenwhoseapprobation wasrequiredforaseriestobeconsideredfashionable(LecturesonLiterature,1:300).Acorrespondentfor TheTraveller applaudedColeridgefor “takingeffectualmeanstorender[hislectures]delightfultothoseofhis auditorswhomwepresumehimpeculiarlyanxioustoplease theFair” (LecturesonLiterature,1:320).Theinfluenceofthewished-forwomen extendedwellbeyondadvertisingtothedevelopmentofcriticalideas: acrossseverallecturesColeridgeelaboratedanaccountof “afeeling,adeep emotionofthemind” thatheeventuallydubbed “lovemomentaneous, ” a coinagethatisatonceadefenseofRomeo’ sapparent ficklenessand Coleridge’sowntakeonthenotionofloveat firstsight(Lectureson Literature,1:327–8).Thustheattempttoattractthewomenauditors whoseapprobationwasnecessaryforaseriestosucceedelicitedfromhima shrewdlycalibratedcriticalinventiveness.

Thesecondmainendservedbytreatingtheperiod’slecturesasoral argumentscouchedforliveaudiencesistheuniqueviewtheyprovideofits literaryculture.Wewouldexpectto findColeridgeandHazlittfeatured prominentlybutnot,perhaps,thattheywereeasilyrivaledbyThelwall andCampbell.Thelwallwasuntilrecentlyknownprimarilyasaradical political figure,whileCampbellhaslingeredattheedgesofliteraryhistory asaminorpoetandfriendofLordByron.Intheirownday,however, auditorslistenedeagerlytoallfourlecturersarguingoftenconflicting criticalagendas.Directingsustainedattentiontopubliclecturingalso bringsintosharperfocusthelastingimpactofThelwallandCampbell onthemodern fieldofliterarystudies.Aslecturers,theypartedcompany withColeridgeandHazlittintwosignificantwaysthatdistinguishtheir literarycriticalperspectives.First,theyopenlywelcomedwomenauditors, andthuswillinglyacknowledgedtheirincreasingimportanceascultural arbiters.ThelwalltaughtfemalestudentsathisLondonschoolalongside his firstwifeand,afterherdeath,hissecond.Fromthebeginninghe includedtheworksofwomenwritersonhissyllabi,includingAnnaLetitia Barbauld,whomColeridgeandHazlittdisparagedintheirlectures. Campbellfranklycourtedfemaleauditorswhomherecognizedasinfluentialpatronswhocouldadvancehisprofessionalandsocialambitions. Second,ThelwallandCampbellagreedthat,asapedagogicalmedium,

lecturescouldbeameansofexpandingtheeducationalfranchise,aviable meansofsocialreformincounter-revolutionaryandwartimeBritain. Bothputtheseviewsintoactionbyparticipatingintheinstitutionalizationofaliteraryeducationorganizedaroundlectures.Thelwallopenedthe doorsofhisLondonschooltothepublicin1806andembracedthe Mechanics’ Institutesmovementintheearly1820s.In1825Campbell initiatedapubliccampaignforwhatwouldbecomeUniversityCollege London.Itwouldmakehighereducationmoreaccessibletomiddle-class menandeventuallybecomethe firstuniversityinEnglandtogrant degreestowomen.Itwouldalsoestablishthe firstchairinEnglish literatureandlanguageinEngland.⁶ Alloftheseinnovationsdemonstrate theimportanceofRomantic-eralecturecultureinthedisciplinaryhistory ofliterarystudiesandthelastingimpactoflesser-known figuressuchas ThelwallandCampbellonthe field.

ViewingRomanticliteraryculturethroughthelensofitspubliclectures alsorevealsanarrayofculturalrolesplayedbyauditorsusingvarious media.Someoftheera’savidlecture-goerswerealsoauthors,including KeatsandMitford.TheywerejoinedbyotherssuchasBuryand Fanshawe whoseliteraryprofileshavefadedbutwhowerewellknownonthe Regencyliteraryscene.Asaculturalarena,publiclecturinghaditsown genderedrestrictions,includingmostobviouslytheexclusionofwomen fromthemainspeakingpart.Itneverthelessprovidedwomenwithother influentialliteraryrolesinanerawhentheystillfacedsignificantlimitationsinprintculture.Somelectureauditorsactedaspatrons,andthey wieldedinfluenceashostsandguestsattheconversationparties,dinners, andotherprivategatheringsthataccompaniedpubliclectures.They pursuedtheseculturalactivitiesinanumberofmediathathaveonly recentlybeguntoreceivesignificantattentioninliterarystudies.Public lectureculturedependeduponthemediumofprintforadvertisements, prospectuses,newspapernotices,andsometimespublicationofthelecturesthemselves.Itwas,however,alsooralcultureandmanuscriptculture.Theperiod’slectureroomsputondisplayarichconcentrationof media,includingpublicoratory,intimateconversation,andmyriad manuscripts,fromlecturers’ speakingscriptstoauditors’ responsesin letters,poems,journals,anddiaries.⁷

⁶ UniversityCollegeLondon’sEnglishDepartmentscrupulouslyqualifiesitsownhistoricalclaims:<http://www.ucl.ac.uk/english/department/history-of-the-english-department>. ⁷ Indiscussingpopularlecturinginthenineteenth-centuryUnitedStates,Wright convincinglysuggeststhatthis “bafflingheterogeneity” ofmediamayhavecontributedto “thephenomenon’ssurprisingscholarlyneglect” (CosmopolitanLyceum,4).

Together,theperiod’sliterarylecturersandtheirauditorsengagedina sustainedculturaldebatethatincludedwhataliteraryeducationshould consistof,whoshouldreceiveone,andforwhatends.Itsintensitywas fosteredbythe “Londonlecturingempire” beingasmallworldinwhich lecturersandauditorswereacutelyawareof,andsometimespersonally acquaintedwith,oneanother.⁸ PeterManningmakesanastuteobservationaboutthesalienceofpubliclecturesatthishistoricalmoment: “If,as JonKlancherandothershaveargued,thereadingaudienceofearly nineteenth-centuryEnglandwasnotsinglebutmultiple,leavingauthors atapuzzlingdistancefromadiversereadershipthattheycouldnotknow, thelecturesofferedafarmoreknowablecommunity,formedbythe combiningcircumstancesofsite,admissionprice,andtheticketsatthe lecturer’sdisposal,whichtosomedegreeenabledhimtopaperthehouse.”⁹ Lecturersrespondedtooneanother’sarguments,spoketoauditorsafter performances,andsocializedwiththematrelatedprivateparties.Auditors suchasMitford,HenryCrabbRobinson,andJamesMontgomeryattended enoughpubliclecturestobeabletocomparelecturers’ performancesand criticalclaims.Thesurvivingdocumentsofallpartiesdemonstratehow commonconcerns,questions,andthemesemergedinwhatformeda sustained,ifdiscontinuousdebateaboutliteraryculturegeneratedinthe period’slecturerooms.Thesixchaptersonlecturersandtheirauditorsaim tocapturesomethingofthatvibrant,animateddiscussion.Theargument isorganizedasfollows.

My first,introductorychapter(Chapter1)sketchestheliterarylecture’ s debtstoestablishedspeakingtraditionsandconsolidatesthelessonsof aninterdisciplinaryconversationabouthowtotreathistoricalspeaking performances.IthenturntoColeridge(eventhoughasalecturerhe followedinThelwall’sfootsteps)fortworeasons(Chapter2).First,he helpedestablishtheRomanticliterarylectureasapopularmediuminhis ownday.Second,hiseffortstonegotiatehisacuteambivalenceabout lecturingreflecttwoconflictsthatwouldcometodefinetheperiod’ s literarylectures:themediumwashauntedbya1790scultureofradical speakinganditalsoseemedtosomealltooenmeshedinacommercialized culturalmarketplace.Inthelectureroom,Coleridgedevelopedhiskey criticalnotionofthe “willingsuspensionofdisbelief” aspartofhiseffortto imaginehimselfasthe “Poet-philosopher” hewishedtoberatherthanthe politicalspeakerhehadbeenorthe “Lecture-monger” hefearedhehad become,inwhatIcallhis “disappearingact.”¹⁰ Duringhis1808

⁸ Hays, “LondonLecturingEmpire,” 91.

⁹ Manning, “ManufacturingtheRomanticImage,” 234.

¹⁰ Coleridge, CollectedLetters,2:668;4:855.

apprenticeshipattheRoyalInstitutionandinhiscelebrated1811–12 seriesonShakespeareandMilton,Coleridgedevelopedinterpretationsof Hamlet and RomeoandJuliet thataccrueanadditionallayerofmeaningas partofthis “disappearingact.” InHamlet,he findsa figureofambivalent identificationwhobyhesitatingtoactfailstodohis “duty,” justas Coleridgefearedhehimselfwasdoingbylecturingratherthancompleting his “greatphilosophicalwork” (CollectedLetters,4:892–3).Self-castas Hamlet,however,Coleridgewasagloriousfailure,acompelling figureof meditativeextemporaneitydespitethevagariesofhisliterarycareer.Inhis lectureson RomeoandJuliet,heattemptstoeaseanotherpersistentanxiety aboutwomen ’sincreasingculturalagency.Inhisreadingoftheplaythe in fluencewomenhaveovermenwhoareinsomewaydependenton them ashewasonfemaleauditors reinforcesmasculineautonomy ratherthandisablingit.

UnlikeColeridge,Thelwallhadnohopeofbanishingtheghostsof hisradicalpast,becausehisroleinthe1794TreasonTrialsrenderedhis publicprofileasapoliticalspeakerindelible(Chapter3).Inreinventing himselfasateacherofelocutionandpractitionerofanearlyformofspeech therapy,Thelwalldidnotsomuchabandonhispoliticalidealsasreshape thenatureofhisdemocraticcommitment.Attheschoolheestablishedin Londonin1806,Thelwallofferedmaleandfemaleauditorsofallagesan educationin “oraleloquence,” andtherebytranslatedthelostcauseof universalsuffrageintoapedagogythathelpedauditorsspeakforthemselves.¹¹Poetrywasacoresubjectinhiscurriculum,andinteachingithe developedadistinctiveandalmostentirelyoverlookedRomanticliterary criticismthattreatspoetryasanoral,performative,sociablegenre.Ioffera portraitofThelwallasaliterarycriticwhointerpretspoemsbyrecitingor readingthemaloud,andjudgesthembyhowwelltheylendthemselves tothesepractices.Thepubliclecturewastheperfectmediumforhis approachtopoetryasacommunicativegenre.Byestablishinghisown school,Thelwallmanagedtoinstitutionalizethisaudibleliterarycriticism, eventhoughhiscommitmenttospokenlanguagealsoworkedtoobscure itslegacy,sincehepreferredextemporaneity,andasaresultrelativelylittle evidenceofhisliterarylecturesseemstohavesurvived.

OneofthepoetswhoseverseThelwallrecitedwasCampbellwho,like Thelwall,authoredadistinctiveliterarycriticismthathasbeenvirtually

¹¹Thelwall, Prospectus,3.Heusestheterm “oraleloquence” inanumberofpublications.In IntroductoryDiscourse hedefinesitas “theArtofcommunicating,bythe immediateactionofthevocalandexpressiveOrgans,topopular,ortoselectassemblies, thedictatesofourReason,orourWill,andtheworkingsofourPassions,orFeelingsand ourImaginations” (2).

losttoRomanticstudies(Chapter4).AnémigréScotwhobecamea central figureontheRegencyliteraryscene,Campbellsoughttorender hislessonsasappealingandreadilyconsumableaspossible.Thisattitude sethiminoppositiontoColeridgeandHazlitt,wholikedtostressthe difficultyofacquiringaestheticjudgment.Thesecanonicallecturersheld upCampbell’ s PleasuresofHope (1799) twobooksofbright,polished coupletslacedwithliterary,andparticularlyclassical,allusions asasignal exampleofeverythingwrongwithmodernpoetry.Theyaccusedhimof panderingtoanexpandingliterarymarketplaceincreasinglyinfluencedby womenreadersandperiodicalcritics.Campbellmostlyshruggedoffsuch attacks,contenttocapitalizeonhispopularitywhenhebegangivinghis ownlecturesin1812atLondon’sRoyalInstitution.Initscelebrated theater,herepeatedthewinningformulationof Pleasures byoffering auditorsaliteraryeducationinhighlypolishedprose,withaparticular emphasisonancientpoetryin(translated)Greek,Latin,andHebrew.Asa lecturer,Campbelltookequalcaretopresenthimselfappealinglyby payingscrupulousattentiontohisowngrooming,dress,anddelivery. Heopenlycourtedauditors,especiallythewomen,correctlyassumingthat theycouldfurtherhissocialandprofessionalambitions.Hewasinturn willingtosharewiththemtheclassicaleducationthathadsponsoredhis ownmobilityandthatwasespeciallydifficultforthemtoacquire.Campbell’scarefullyscriptedperformanceswere,however,alsounderwrittenby aseriousagendaofeducationalreformthatculminatedinhispublic campaignfora “MetropolitanUniversity” thatwouldnotdiscriminate onthebasisofrankorreligion.Campbellestablishedavitallinkbetween Romantic-eraliterarylecturesandtheinstitutionalizationofmodern literarystudieswhenheproposedauniversityorganizedaroundlectures (ratherthanOxbridgetutorials)inalettertotheLondon Times. BythetimeHazlittbeganlecturingonliterature,hisrivalsThelwall, Coleridge,andCampbellwerealreadypopularspeakers.Inhis firstseries, LecturesontheEnglishPoets (1818),Hazlittentersintoanintensive engagementwiththeperiod’soralcultures(Chapter5).Iarguethathe negotiatesadeeplyambivalentrelationshiptothosecultures,which extendedfromtheradicalspeakingofthe1790stotheglitteringRegency lecturescenethathejoined.InparticularColeridge’svoiceasaDissenting preacherandpoetof LyricalBallads hadcarriedHazlitt’spoliticaland aesthetichopes.By1818,thatearlyoptimismhadbeendisappointed,but Hazlittwasdeterminedtogleanforhisowncriticalprosetheappealing qualitiesthathadenchantedandinspiredhimintheoralculturesofhis youth.Ireadhis firstliteraryseriesasatourdeforceperformanceinwhich heconsolidatestheincreasingly fluidprosehehadhonedasajournalist intotheconversational “familiarstyle” thatwouldbecomehissignatureas

acritic.Atthesametime,Hazlittresistedwhatheviewedasthedangersof publicspeaking,choosinginsteadtoactlikeanauthor,performingthe qualitiesofintellectualindependenceandinterioritythatheassociated with “writing” inhisessay “OntheDifferenceBetweenWritingand Speaking” (1820).In Lectures Hazlittalsopubliclystakeshiscriticalclaims byreadingthehistoryofEnglishpoetryasadeclinefromitsbrightearly promisetoapresentmoment,representedbythelectureroomitself,in whichanincreasinglycommercialized,feminizedliterarymarketplace discouragedthepatientpursuitof “truefame.” Ipayparticularattention totheseries’ well-knownendingonthe “livingpoets,” inwhichHazlitt mournsthelossofhishopesintheearlyColeridgeandclaimshisformer mentor ’sroleasaleadingpoliticalandculturalcriticinhisownpreferred mediumofprint.

TheverseofJohnKeats,Hazlitt’sbest-knownauditor,demonstrates howtheperiod’sliterarylecturesimpacteditspoetry(Chapter6).Weare usedtothinkingofKeatsasamuseum-goer(“OnSeeingtheElgin Marbles”)andreader(“OnSittingDowntoReadKingLearOnce Again”),buthisroleaslectureauditorinfluencedhispoetryinways thatwehaveyettoappreciatefully.AttheSurreyInstitutionKeatslearned notonlyfromwhatHazlittsaid,butalsofromhowhesaidit:thelecturer’ s famouslyaggressive,theatricaldeliveryhelpedKeatsbettertounderstand thetremendousimpactthatahumanvoicecouldhaveonthelistener. Keatshadalreadybeentrainedasanauditorintheperiod’sEnlightenment sciencecultureatEnfieldAcademyandGuy’sHospital.Inaddition, shortlybeforeHazlitt’sseries,KeatsreviewedseveralplaysontheLondon stageandbecamefascinatedbyEdmundKean’ s fierce “eloquence.” Keats recognizedasimilarqualityinHazlitt’slectures,andattemptedtocapture itforhisverse.Inhisunderstudiedsonnet, “Othouwhosefacehathfelt thewinter’swind,” Keatsoffersarare,unrhymedpoemofpurehearing, featuringaspeakerwhodoesn’tsayaword.Thelessonsinthedramaof listeningthatKeatsabsorbedattheSurreyInstitutionresurfacestrikingly inlaterpoems,including “OdetoaNightingale” and “TheFallof Hyperion.” ScholarshaverecognizedthedramaticqualityofKeats’ matureverse,andIarguethathisexperienceasHazlitt’sauditorhelped tocrystallizeit.Inthesepoemsandinthelettersthathewroteduringand aftertheseriesinwhichheengagedwithHazlitt’sarguments,Keats’ responsesasalistenerconstituteliteraryworksintheirownright. InthelectureroomKeatssatalongsidethewomenreadersaboutwhom hewasfamouslyambivalentasanaspiringpoet(Chapter7).Thatspace servesasastageforthediverserangeofactiverolesthatwomenplayedin Romanticliteraryculturebeyondthatofauthor.Theinfluenceofthe French salonnières andtheBritishBluestockingsiswidelyrecognized,but

wehaveonlybeguntoacknowledgetheactivitiesoftheirRomantic-era counterparts.Theperiod’spubliclecturesandtheprivatepartiesthat sometimesfollowedareimportantforunderstandingwomen’scultural impactasauditors,convivialhostsandguests,andpatrons,aswellas authors.Theypursuedtheirownaimsinavarietyofculturalmedia includingsomethathavebeenreceivingincreasingattentioninliterary studies,suchasconversationandworksinmanuscript.Fewwomenhada significantpresenceinthelectureroomasauthorswhoseworkswere treated,buta figureasprominentasBarbauldcouldnotbeignoredif lecturerswishedtospeaktothemoment.ColeridgeandHazlitttriedto delimitwomen’sinfluenceinliteraryculturepartlybydisparagingherand byadmonishingauditorsnottofollowliteraryfashionsassociatedwith womenwriters(especiallynovelreading).AuditorslikeMitfordignored suchstrictureswhileavidlypursuingtheirownliterarycareers,treatingthe lectureroomasaschoolroom.Mitford’sapprenticeshipinvolvedpenning epistolaryresponsestowhatsheheard,includingirreverentaccountsof Coleridge’s,Campbell’s,andHazlitt’sperformances.BythetimeLady CharlotteBurysatinCampbell’slectures,shewasanauthorinherown right.Shepublishedmostofher “silverfork” novelsanonymously,inpart toprotectherpositionaslady-in-waitingtothePrincessofWales(afterwardQueenCaroline),aroleshesubsequentlyexploitedintheanonymous(butswiftlysurmised)publicationof DiaryIllustrativeoftheTimesof GeorgeIV (1838).AttheRoyalInstitutionBuryidentifiedCampbellasa poettopatronize,invitinghimintotheroyalhouseholdandthereby advancinghissocialandliteraryambitions.InSydneySmith’slectures onmoralphilosophyattheRoyalInstitution,thepoetandartistCatherineMariaFanshawefoundarichsourceofinspirationforan “Ode” that challengedcontemporaneoussatiresonwomen’sprominenceinlecture audiences.Fanshawedidnotattempttopublishherworks,preferringto circulateherpoetryinmanuscriptinliterarycirclesthatincludedfellow lectureauditors.Shefrequentlytookashersubjectthesociableoral culturesinwhichsheparticipatedasavaluedguest,includingliterary conversationsheldathousepartiesandprivatedinners.Inthesedomestic settingsandinlecturerooms,womenfoundspaces filledwithpossibility fortheirownliteraryactivities.Itis fittingthatlistenershavethelastword inthisbook,astheysooftendidinlife.

Acknowledgments

Thisbookhasbeenalongroad,andIwasfortunatetohavealotofhelp onit.Travelforresearchandtimetowritewasgenerouslysupportedby FordhamUniversity,andtheACLSprovidedtheboonofanentireyear thatenabledmetolaytheproject’sfoundations.SusanWolfson,Peter Manning,andAlanBewellofferedencouragementandsupportfromthe beginning.Idiscoveredthatspeakingaboutoralcultureaddedalevelof intensitytoconferencesandothertalks,andtheresponsesIreceivedat theseeventsprovedtobeaparticularlyrichsourceofinsightandenergy. Forhelpfulexchangesandinvitationstopresentwork-in-progressIam especiallygratefultothelatePaulMagnuson,OrrinWang,Michael Macovski,Anne-LiseFrançois,JonKlancher,ElizabethDenlinger,Nick Roe,CharlesMahoney,JacobRisinger,JeffreyCox,JillHeydt-Stevenson, SeanFranzel,KurtisHessel,KevisGoodman,andDannyO’Quinn.

Ihavereceivedvitalassistanceinpiecingtogetheraccountsof Romantic-erapubliclecturesandtheinstitutionsthatsponsoredthem frommanyarchives,collections,andlibraries.IamindebtedtoFrank JamesoftheRoyalInstitutionofGreatBritainforhelpingmetounderstandtheseevents,includingtheopportunitytoattendalecturethere myself.Sincerethanksgotothemembersofstaffwhohaveanswered questionsandmadeusefulsuggestionsattheBritishLibrary;theNational ArtLibraryattheVictoriaandAlbertMuseum;theWellcomeCollection; theGuildhallLibrary;theLondonMetropolitanArchives;theUniversity ofLondonArchive,SenateHouseLibrary;theRoyalInstituteofBritish ArchitectsLibraryandCollections;theResearchLibraryandArchiveat SirJohnSoane’sMuseum;theNationalLibraryofScotland;theMitchell Library,Glasgow;ArchivesandSpecialCollectionsattheUniversityof Strathclyde;theDundeeUniversityArchives;theCarlH.Pforzheimer Collection;theHenryW.andAlbertA.BergCollectionofEnglishand AmericanLiterature;theRareBooksDivisionoftheNewYorkPublic Library;theBeineckeRareBookandManuscriptLibrary;andtheRare BooksandSpecialCollectionsatPrincetonUniversity.

Anumberofscholarsgraciouslyrespondedtoquerieswithinsightand information,includingMichaelScrivener,R.A.Foakes,GeoffreyCarnall, GregoryClaeys,RichardHolmes,andDuncanWu.Ihavebeenfortunate inhavingeditorsforearlierversionsofseveralchapterswhoadvancedand sharpenedmythinking,includingAngelaEsterhammer,AlexDick,Charles Mahoney,andRobertDeMaria.SamanthaSabalis,DavidQuerusio,and SeanSpillaneprovidedexcellentresearchassistance.Iamindebtedto

everyoneIhaveworkedwithatOxfordUniversityPressincludingtwo anonymousreaderswhogavewonderfullythorough,perceptivecritiques.

Anumberofreaderscontributedastutecommentarythatfueled thoughtandrevisionincludingSusanDavidBernstein,AniruddhoBiswas, LennyCassuto,AnneFernald,KevinGilmartin,WolfgangMann,and ManyaSteinkoler.JudithThompsonreaddraftsandsharedresearchand anenthusiasmthatrejuvenatedminewhenitwas flagging.DavidDuff offeredguidanceandgoodreadingatacrucialmomentinconcludingthe project.AlongthewayJohnBuggwasinfinitelygenerousinoffering adviceandsuggestingingeniouswaysoutofcornersintowhichIhad writtenmyself.AstheprojecttookshapeStuartShermangraciously discusseditall,inconversations filledwithhilarityandkindness.This bookispartlyabouttheartoflistening,aboutwhichIlearnedtomesfrom MarvinGeller.ItsaddensmethatKristinGagerisnotheretocelebrate thecompletionofthisproject,especiallysinceherfriendshipextendedto lendingitherastuteeditorialeye.

Mymostpersonaldebtsaretothosewhokeptmegoing,keptme laughing,keptmedivertedwhenIneededit,andconvincedmeto finish already,includingMosheSluhovsky,GingerStrand,andWolfgang Mann.AniruddhoBiswassawmethroughtotheend.Myfamilyhas beenasustainingforce,andIamhappythatcompletingthisprojectwill leavemoretimetospendwithJay,Julie,Kate,andJacob.Myparentswere my firstandbestteachers.Byreadingwhatseemedanentirechildren’ s librarytomeincludingDr.Seuss, TheStoryofFerdinand,andRobert LouisStevenson’spoems,mymothertaughtmetolovestories,animals, andthesoundsofwords.Myfatherwasmylast,bestreaderofthisbook, whoconsideredeveryword,morethanonce,withawriter’searanda structuralgeologist’skeeneye.ItisdedicatedtoIsabelandJaywithlove. Earlierversionsofseveralchaptersappearedinthefollowingpublications,andIamgratefulforpermissiontoreprintthismaterial.Aversionof Chapter2appearedas “ColeridgetheLecturer,aDisappearingAct,” in SpheresofAction:SpeechandPerformanceinRomanticCulture,editedby AngelaEsterhammerandAlexanderDick.©UniversityofTorontoPress, 2009.46–72.Reprintedwithpermissionofthepublisher.Aversionof Chapter6appearedas “BritishRomanticWomenWriters,Lecturers,and theLastWord,” in TheBlackwellCompaniontoBritishLiterature.Vol.4: TheLongEighteenthCentury,1660–1837,editedbyRobertDeMaria,Jr., HeesokChang,andSamanthaZacher.Malden,MA:Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.380–95.©JohnWiley&Sons,Ltd.AversionofChapter7 appearedas “TheThrushintheTheater:KeatsandHazlittattheSurrey Institution,” in ACompaniontoRomanticPoetry,editedbyCharles Mahoney.Malden,MA:Wiley-Blackwell,2011.217–33.©JohnWiley &Sons,Ltd.

2.ColeridgetheLecturer,ADisappearingAct