Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

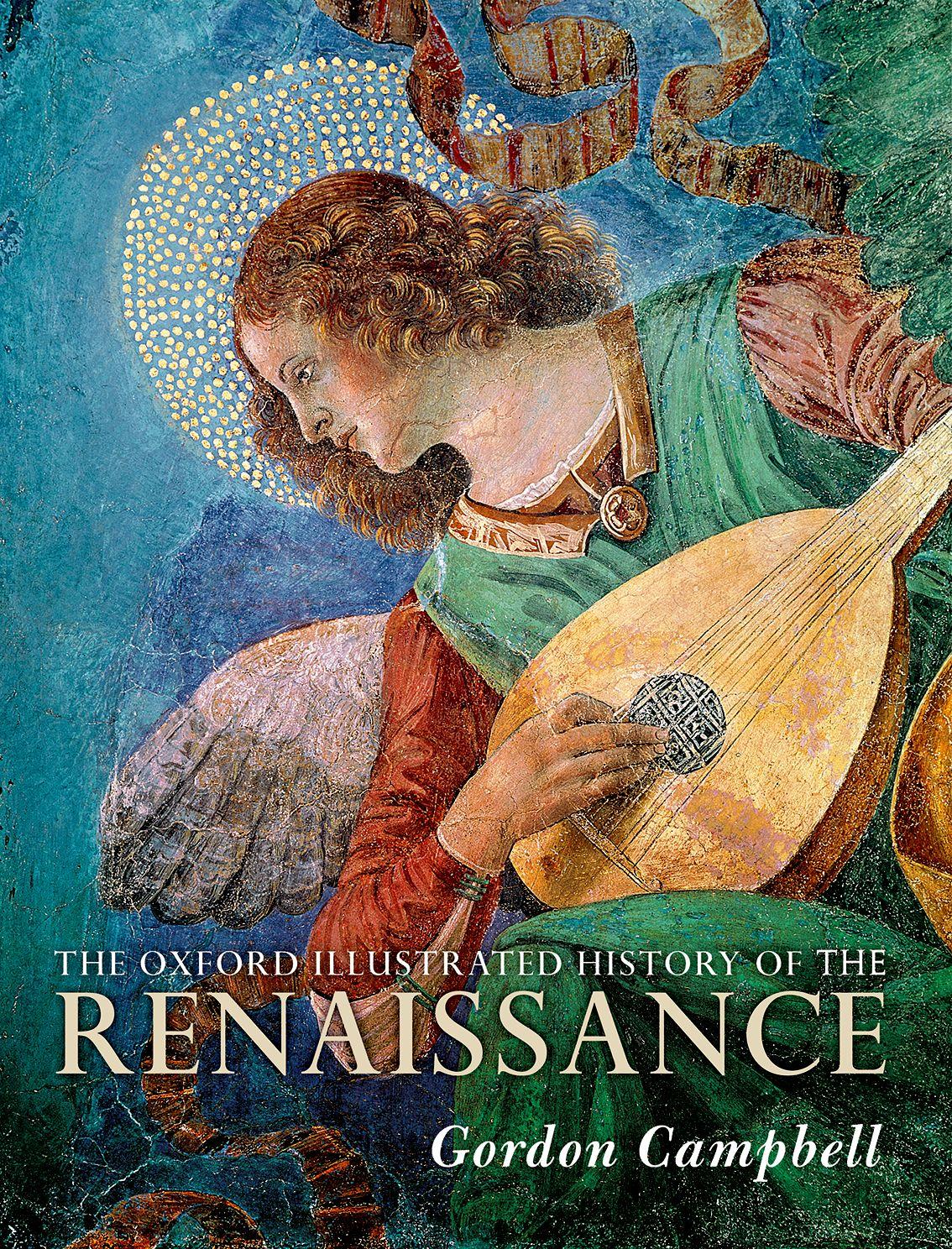

The Oxford Illustrated History of the Renaissance 1st Edition Gordon Campbell

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-illustrated-history-of-therenaissance-1st-edition-gordon-campbell/ ebookmass.com

The Oxford History of the Renaissance Gordon Campbell

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-history-of-the-renaissancegordon-campbell/

ebookmass.com

The Oxford Illustrated History Of The Book James Raven

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-oxford-illustrated-history-of-thebook-james-raven/ ebookmass.com

Run and Hide: A Novel Pankaj Mishra

https://ebookmass.com/product/run-and-hide-a-novel-pankaj-mishra/ ebookmass.com

The Joy of Cannabis: 75 Ways to Amplify Your Life Through the Science and

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-joy-of-cannabis-75-ways-to-amplifyyour-life-through-the-science-and-magic-of-cannabis-melanie-abrams/

ebookmass.com

The Obsession Sutanto

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-obsession-sutanto/

ebookmass.com

Savage Lovers: The Caraksay Brotherhood. Book 4 Ashe Barker

https://ebookmass.com/product/savage-lovers-the-caraksay-brotherhoodbook-4-ashe-barker/

ebookmass.com

Vice & Virtue: Part One: A Prohibition Era Mafia Romance Gray

https://ebookmass.com/product/vice-virtue-part-one-a-prohibition-eramafia-romance-gray/

ebookmass.com

Natural Law Republicanism: Cicero's Liberal Legacy Michael C. Hawley

https://ebookmass.com/product/natural-law-republicanism-cicerosliberal-legacy-michael-c-hawley/

ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/handbook-of-microbial-nanotechnologychaudhery-mustansar-hussain/

ebookmass.com

THEOXFORDILLUSTRATEDHISTORYOF

THERENAISSANCE

Thehistorianswhocontributedto TheOxfordIllustratedHistoryoftheRenaissance areall distinguishedauthoritiesintheir field.Theyare:

FRANCISAMES-LEWIS Birkbeck,UniversityofLondon

WARRENBOUTCHER QueenMaryUniversityofLondon

PETERBURKE UniversityofCambridge

GORDONCAMPBELL UniversityofLeicester

FELIPEFERNÀNDEZ-ARMESTO UniversityofNotreDame

PAULAFINDLEN StanfordUniversity

STELLAFLETCHER UniversityofWarwick

PAMELAO.LONG Independentscholar

MARGARETM.M GOWAN UniversityofSussex

PETERMACK UniversityofWarwick

ANDREWMORRALL BardGraduateCenter

PAULANUTTALL VictoriaandAlbertMuseum

DAVIDPARROTT UniversityofOxford

FRANÇOISQUIVIGER TheWarburgInstitute

RICHARDWILLIAMS RoyalCollectionTrust

TheeditorandcontributorswishtodedicatethisvolumetoMatthewCotton.

THEOXFORDILLUSTRATEDHISTORYOF

THE RENAISSANCE

Editedby GORDONCAMPBELL

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford, , UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©OxfordUniversityPress Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted FirstEditionpublishedin Impression:

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY ,UnitedStatesofAmerica BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:

PrintedinItalyby L.E.G.O.S.p.A.Lavis(TN)

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Introduction

GordonCampbell

CONTENTS

.HumanismandtheClassicalTradition

PeterMack

.WarandtheState, c.

DavidParrott

.Religion

StellaFletcher

.TheCivilizationoftheRenaissance

FrançoisQuiviger

.ArtandArchitectureinItalyandBeyond

FrancisAmes-Lewis

.ArtandArchitectureinFlandersandBeyond

PaulaNuttallandRichardWilliams

.ThePerformingArts:Festival,Music,Drama,Dance

MargaretM.McGowan

.VernacularLiterature

WarrenBoutcher

.CraftandTechnologyinRenaissanceEurope

PamelaO.LongandAndrewMorrall

.TheRenaissanceofScience

PaulaFindlen

FelipeFernández-ArmestoandPeterBurke

FurtherReading

PictureAcknowledgements

Index

Introduction

T Renaissanceisamodelofculturaldescentinwhichthecultureof fifteenth-and sixteenth-centuryEuropeisrepresentedasarepudiationofamedievalworldindecline infavouroftherevivalofthecultureofancientGreeceandRome.Theparallel religiousmodelistheReformation,inwhichthechurchisrepresentedasturningits backoncorruptionanddeclineinfavourofarenewalofthepurityoftheearlychurch. Inbothmodels,therehadtobeaninterveningmiddleperiodbetweenthegloriouspast anditsrevival.TheideaoftheMiddleAges(mediumaevum)wasintroducedtoEuropean historiographybytheRomanhistorianFlavioBiondoin ,andquicklybecamea commonplace.ThereafterEuropeanhistorywasconventionallydividedintothree periods:classicalantiquity,theMiddleAges,andthemodernperiod.Thebiblical metaphorofrebirthwas firstappliedtoartbyGiorgioVasari,whousedthetermto denotetheperiodfromCimabueandGiottotohisowntime.Itwascertainlyan inordinatelyslowbirth.

Thebroadeningoftheterm ‘renaissance’ toencompassaperiodandacultural modelisaproductofthenineteenthcentury,albeitwithrootsintheFrench Enlightenment.ThatiswhyweusetheFrenchform(renaissance)ratherthanthe Italian(rinascità)todenotethisrebirth.In theFrenchhistorianJulesMichelet usedtheterm ‘Renaissance ’ asthetitleofavolumeonsixteenth-centuryFrance.Five yearslaterJacobBurckhardtpublished DieCulturderRenaissanceinItalien (The CivilizationoftheRenaissanceinItaly),inwhichheidenti fiedtheideaofaRenaissancewithasetofculturalconcepts,suchasindividualismandtheideaofthe universalman.Vasari ’sdesignationofamovementinarthadbecomethetermfor anepochinhistoryassociatedwithaparticularsetofculturalvalues.Theseissues areexploredindetailinFrançoisQuiviger ’schapteron ‘ TheCivilizationofthe Renaissance’ ,whichexplorestheafterlifeofBurckhardt ’sconceptofindividuality inmorerecentnotionsofself-fashioningandgender fl uidity,andinthecomplex notionofthe ‘self ’ .

ThemodeloftheRenaissancehasevolvedovertime.Anoldergenerationof historianshadapredilectionforprecision:theMiddleAgesweredeemedtohave

begunin withthefalloftheRomanEmpireintheWestandconcludedwiththefall ofConstantinoplein ,whenGreekscholars fledtoItalywithclassicalmanuscripts undertheirarms.Thisbooksubvertsthoseeasyassumptionsateveryturn,butthe contributorsnonethelessassumethatthemodelofaculturalRenaissanceremainsa usefulprismthroughwhichtheperiodcanbeexamined.Thatmodelhasbeen challengedbythosewhoprefertothinkofthe fifteenthandsixteenthcenturiespurely intermsofatemporalperiodcalledtheEarlyModernperiod.Thisideais,ofcourse,as fraughtwithideologicalbaggageasisthetermRenaissance,andembodiesnarrow assumptionsaboutculturaloriginsthatmaybedeemedinappropriateinamulticulturalEuropeandaglobalizedworld.

ThisisabookabouttheculturalmodelofaRenaissanceratherthanaperiod.That said,itmustbeacknowledgedthatwhilethismodelremainsserviceable,italsohas limitations.TheideaofaRenaissanceisofconsiderableusewhenreferringtothe scholarly,courtly,andevenmilitaryculturesofthe fifteenthandsixteenthcenturies, becausemembersofthoseeliteswereconsciouslyemulatingclassicalantiquity,butit isoflittlevalueasamodelforpopularcultureandtheeverydaylifeofmostEuropeans. Theideaofhistoricalperiods,whichisemphasizedbytheuseofcenturiesorrulersas boundaries,isparticularlyproblematicalinthecaseoftheRenaissance,becausea modelthatassumestherepudiationoftheimmediatepastisinsufficientlyattentiveto culturalcontinuities.

Suchcontinuitiesaresometimesnotreadilyapparent,becausetheyareoccludedby Renaissanceconventions.Shakespeareisacaseinpoint.Hewasinmanywaysthe inheritorofthetraditionsofmedievalEnglishdrama,andheaccordinglydividedhis playsintoscenes.Printedconventions,however,hadbeeninfluencedbytheclassical conventionsinRenaissanceprintingculture.Horacehadsaidthatplaysshouldconsist ofneithermorenorlessthan fiveacts(‘Neueminorneusitquintoproductioractu fabula’ , ArsPoetica ).Shakespeare’splayswerethereforeprintedin fiveacts,andso wereappropriatedintotheclassicaltradition.In ,threeyearsafterBurckhardt hadpublishedhisbookontheRenaissance,theGermanplaywrightGustavFreytag publishedanessayondrama(DieTechnikdesDramas)inwhichheadvancedthethesis thata five-actstructure(exposition,risingaction,climax,fallingaction,denouement) canbediscernedinbothancientGreekdramaandintheplaysofShakespeare.The modeloftheRenaissancewastherebyimposedonthestructureofShakespeare’splays (andoftheplaysoftheancientGreekplaywrights).Thisin fluencemayalsobeseenin theearlyquartosofShakespeare’splays.Theinclusionofclassicizinggenres(comedy andtragedy)onthetitle-pages(suchas APleasantConceitedComedycalledLove’sLabour’ s Lost and TheMostExcellentandLamentableTragedyofRomeoandJuliet)wouldseemtobe thepromotionalworkofthepublisher,nottheauthor.WhenShakespeare’scolleagues decidedtoassembleaposthumouscollectionofhisplays,theychosetopublishthem inafolioformat,whichwastheformnormallyassociatedwiththepublicationof classicaltexts.Withinthisfamousfolio,theplayswereorganizedinthreegenres: comedy,tragedy,andhistory,thelastofwhichwasborrowedfromanancientnon-

dramaticgenre.BysuchmeanspublishersobscuredtherootsofShakespeare’splaysin vernacularEnglishdrama,andsoappropriatedhisworktothemodeloftheRenaissance.Theplaysdoreflectinnovativeclassicalinfluencesaswellasculturalcontinuities withtheMiddleAges.Manyofthechaptersinthisbookaddresstheblendof continuityandinnovationinthecultureoftheperiod.

ThemodeloftheRenaissancestillaffectstheEuropeansenseofitspast.InEngland, forexample,secondaryschoolsdonotteachthelanguageofEngland’spast AngloSaxon becauseourlineofculturaldescentisdeemedtooriginateinancientGreece andRome;traditionalschoolsthereforeteachclassicalLatin,andsometimesancient Greek.ThehumanistsoftheRenaissancebelievedthatclassicalLatinwaspureand medievalLatincorrupt,andsotaughtclassicalLatin;wedothesametoday.Inthecase ofGreek,wearemuchmoreprecise.WedonotteachHomericGreekorByzantine GreekormodernGreek,butrathertheGreekofAthensinthe fifthcentury .Inthis sense,weareinheritorsoftheRenaissance.

RenaissancehumanistsarethesubjectofPeterMack’schapter,whichtracesthe contoursofhumanismfromitsoriginsinItaly(especiallyPadua)andtheseminal figureofPetrarchbeforeturningtothehumanistscholarsof fifteenth-centuryItalyand theslightlylaterhumanistsofnorthernEuropeandSpain.Thehumanistmovement representedbythesescholarshadatransformativeimpactontheeducationalinitiativesoftheRenaissance,andalsoleftitsmarkonacademicdisciplinessuchas philosophy,history,andclassicalscholarship.

Humanismwasalsoimportantfornationalliteratures.Theburgeoningofvernacularliterature,acceleratedbythetechnologyofprint,producedadistinguishedcorpus ofliteratureinmanylanguages.Thisliterature,muchofwhichisindebtedtoclassical models,isthesubjectofthechapterbyWarrenBoutcher.Latinwasthelanguageof educateddiscourse,butthroughoutthisperioditfacedafast-growingrivalinvernacularwriting,whichcreatednewliteraryculturesamongstaplethoraoflaypublics.In somecasesclassicalgenreswereretainedforwritinginvernaculars,sotheperiodis repletewithexamplesofepicsandtragedieswritteninnationallanguages.The languageoftheinternationalrepublicofletterswasLatin,butthehegemonyofLatin asthelearnedlanguageofEuropewasincreasinglychallengedbyFrench,thelanguage thatalsoproducedwhatmightbeclaimedasEurope’smostdistinguishedbodyof vernacularliterature.

TheideaoftheRenaissancehasslowlyevolvedsincethenineteenthcentury.There wasanassumption(nowanembarrassment)thatEuropewasthecentreofthe world,thatEuropeanshaddiscoveredotherpartsoftheworldandbroughtcivilizationtotheuncivilized.Nowwespeakofculturalencounters,andacknowledgethat therewerecomplexculturalexchanges.Theseissuesareexploredinthechapteron theglobalRenaissancebyPeterBurkeandFelipeFernandez-Armesto,whodescribe theinterfacesbetweentheEuropeanRenaissanceandtheculturesoftheByzantine Empire,theIslamicworld,Asia,theAmeri cas,andAfrica.Travellers,including missionaries,disseminatedEuropeanideasandinturnwerein fl uencedbythe

GordonCampbell

culturesinwhichtheyfoundthemselves.Printenabledwordsandimagestobecome vehiclesofculture,andtravellersbroughtartefactsbacktoEurope.Therehadbeen manyrenaissancesinvariouspartsofth eworld,buttheEuropeanRenaissancewas the fi rstglobalRenaissance.

WithinEurope,informssuchasarchitecture,thetraditionalmodelofacultural movementbeginninginItalyandFlandersstillhasmuchtocommenditself,aslongas linesarenotdrawnrigidly.ItalianRenaissancearchitecturespreadwellbeyondItaly: theBelvedereinthegardenoftheHradcanyinPragueisawhollyItalianatebuilding,as arethePalaceofCharlesVintheAlhambra,theBoimiChapelinLviv(nowinUkraine), andthereconstructedroyalpalaceinVisegrád(Hungary).Therearealsostriking examplesofculturalhybridity,suchasthearcadedgalleries(withlocalandVenetian elements)aroundthesquaresinZamosc(Poland),theOrthodoxdecorationofthe interiorofthePalaceofFacetsintheMoscowKremlin,andtheIslamicstrainin SpanisharchitectureaftertheReconquista.NorareRenaissancebuildingsconfined toEurope.ThedebttoItalyinthearchitectureofJuandeHerreraisreadilyapparentin theEscorial,butItalianformsandHerreranmonumentalseverityalsocharacterizethe earlycathedralsintheSpanishEmpire,notablyMexicoCity,Puebla,andLima.

)inthegardenoftheHradcanyinPraguewas designedbyPaoloStella,anItalianarchitectandsculptor.Thesandstonereliefsonthebuildingare theworkofItalianmasons.TheBelvedereistheearliestwhollyItalianatebuildingtohavebeen builtnorthoftheAlps.

,Peru (

),wasdesignedbytheSpanisharchitectFranciscoBecerra,whohadpreviously designedPuebloCathedralinMexico().ThetwotowersshowtheinfluenceofJuande Herrera’sEscorial,nearMadrid.TheinterioraislesareRenaissanceinstyle.

Inthetwenty-firstcentury,themodeloftheRenaissanceischaracterizedbyits breadth,butalsotheelasticityofitstemporalboundaries.Italianistscharacteristically regardthedeathofRaphaelin andtheSackofRomein asmarkingtheendof theHighRenaissance.StudentsoftheSpanishGoldenAge,ontheotherhand,seethe periodofSpain’sartisticandliteraryzenithasbeginninginthe s(theReconquista concludedin )andextendingtotheearlyseventeenthcentury,withthedeathof LopedeVegain .TheadvantageoftreatingtheRenaissanceprimarilyasacultural phenomenonratherthanaperiodisthatsuchtemporaldiscrepanciesareeasily accommodated.Thechaptersinthisvolumewillthereforedescribethehistory(especiallytheculturalhistory)ofalongRenaissance,andonewithpermeableboundaries. ThestudyoftheRenaissanceisdominatedbythehistoryofartandarchitecture. Twochaptersinthisvolumeattendtotheseminalcentresofartandarchitecture,andto theirinfluence.FrancisAmes-Lewis’schapteriscentredonItalyandbeyond,andPaula NuttallandRichardWilliamsdiscusstheartandarchitectureoftheNorthernRenaissanceinFlandersandbeyond.FrancisAmes-LewisconsiderstheaccessthatItalian Renaissanceartistsandarchitectshadtotheartandarchitectureofclassicalantiquity, andhowtheyinterpretedthosemodelsforcontemporaryclients.Burckhardt’svisionof theRenaissanceascentredonmanratherthanGodisusedasthestartingpointofthe

discussionofthehumanforminRenaissancesculptureandportraiture.Italian Renaissancepaintingwasindebtedtosurvivalsfromclassicalantiquity,butperhaps moreimportantly,drewontheclassicalnotionofmimesis,theimitationofnature. Thecontemporarymodelsthatwereexaminedthroughtheprismofmimesis includedtheworkofNorthEuropeanartists,notablyinFlanders.

ThechapterontheartandarchitectureofnorthernEurope,byPaulaNuttalland RichardWilliams,focusesontheeffectonlocaltraditionsoftheideasoftheRenaissance.The fifteenthandsixteenthcenturiesaretreatedseparately,becausetheleaky watershedof marksashiftintherelationshipbetweennorthernandsouthernart. Inthe fifteenthcentury,theartofnorthernEuropewasinsmallmeasureinfluenced bydevelopmentsinItaly,butthedominantchangewasaseriesofinnovationsinthe norththatparalleledorprecededcomparableshiftsinItalianart.Inthesixteenth centurytherelationshipchanged,astheburgeoninghumanistmovementinthenorth begantofacilitatedirectItalianinfluenceontheartofthenorth,whichincreasingly reflectedtheclassicalidealsoftheItalianRenaissance.Thesedivisionsbetweennorth andsoutharenotalwayssharp,partlybecauseartistsandarchitectsweremobile,so therewereFlemishartistsworkinginRomeandItalianartistsworkinginnorthernand centralEurope,andartisticrelationsbetweencentressuchasVeniceandNuremberg facilitatedconstantexchanges.

Fromatwenty-first-centuryperspective,the fifteenthandsixteenthcenturiesseem tobedominatedbywarsandreligion andbywarsarisingoutofconfessional differences.Itwouldbeamistake,however,tothinkofreligionandwarfareinterms ofourownexperience.Religionprovidedalanguagenotonlyforarticulatingbeliefin God,butformanymattersforwhichwewouldnowusethelanguageofpoliticsor humanemotion.TheartisticimageoftheMadonnaandChild,forexample,wasa centuries-olddevotionalimagewithpaganrootsinthedepictionofIsisandHorus,but atthehandsofRenaissance(initiallyVenetian)artists,itbecameanintenselyhuman imageofamotherandherinfantson.

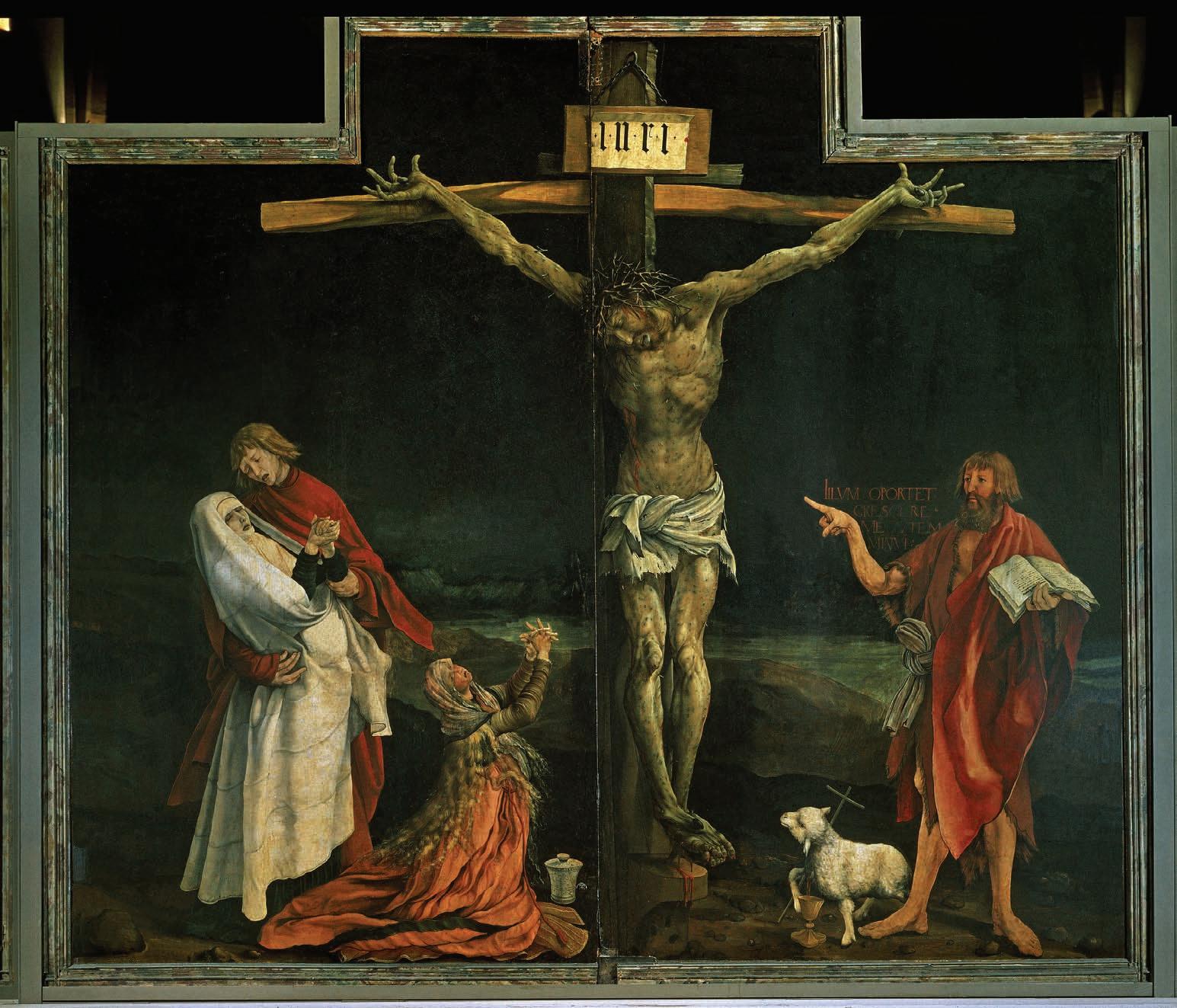

Conversely,theartoftheperiodcanreflectstrandsofspiritualityintheRenaissance. ThecrucifixionpanelinGrünewald’sIsenheimAltarpiecedepictsthetorturedbodyof Jesusonthecross,hisskincoveredwithsores,hishandstwistedwiththepainofthe nails,andhisfeetcontortedbythesinglenaildriventhoughthem.Thepaintingwas originallyhunginamonastichospitalthatcaredforthedying,andpatientswhogazed atthebodyofJesuswouldnothavethoughtofitintheologicalterms(seeing,for example,thethreenailsasanimageoftheHolyTrinity),butasareflectionoftheirown afflictions,andpossiblyasanaffirmationthatgracecansurvivethedestructionofthe body.StellaFletcher’schapteronreligionisanaccountofthespiritualitiesthat characterizesuchbelief,andoftherefractionsofthosespiritualitiesintheartofthe Renaissance.

Europewascontinuouslyatwarintheyearscoveredbythisvolume,buttherewas neitherlarge-scaledestructionnorvastnumbersofcasualtiesbycomparisonwiththe warsofthetwentiethcentury.InRenaissanceEurope,manymorepeoplediedof

),centralpaneloftheIsenheimAltarpiece(

). OnthelefttheVirginMaryisheldbyStJohntheEvangelist,andMaryMagdalenekneelsin prayer.OntherightJohntheBaptistpointstoJesus,holdingascrollthatreads(inLatin) ‘hemust increasebutImustdecrease’ (John :).

plague,andofchildbirth,thanwerekilledinbattle.Warcouldbebrutal,butitwasalso regardedasanart,asubjectexploredinDavidParrott’schapteron ‘WarandtheState’ . Machiavellistoodattheheadofalongsuccessionoftheorists,manyofwhomsawwar throughtheprismofthewarsofclassicalantiquity.Warwasdrivenbyaggrievedrulers whoweremotivatedbyconsiderationsofhonour,reputation,andvindication.The natureofwarfareevolvedconstantlythroughouttheperiod,partlybecauseofdevelopmentsinweaponryandfortifications,butalsobecauseofthechangingnatureof armiesandnavies.

ThestudyoftheartsintheRenaissancehastraditionallybeenfocusedonwhat aretraditionallyknownasthe finearts:painting,sculpture,architecture,music(i.e. composition),andpoetry.TheseareallspheresinwhichartistsoftheRenaissance producedsomeofthe finestcreationsofEuropeancivilization.Thispreoccupation

GordonCampbell

withthe fineartsinsubsequentcenturieshas,however,oftenplayeddownthe importanceofotherareasofcreativeendeavour.Thedistinctionbetweenthe fine artsandthedecorativeartsthat firstemergedinthemid-eighteenthcentury,for example,establishedahierarchyoftaste:the fineartswereintendedtogivepleasure, whilethedecorativearts(thenknownasthemechanicalarts)weredeemedtobe merelyuseful.Easelpaintingwasa fineart,butthepaintingof figuresonpotterywas decorative;theexteriorsofbuildings(includingtheirgardens)weretheproductofthe fineartofarchitecture,buttheinteriors(includinglayoutaswellas fittingsand furnishings)weredecorativeart;sculptinginmarblewasa fineart,butivory-carving andwood-carvingwerecrafts.Suchdistinctionspersistinmodernattitudes,and unhappilysuppresspopularawarenessofsomemagnificentworksofart,suchas BenvenutoCellini’ssaltcellar,nowintheKunsthistorischesMuseuminVienna.The virtuosocraftsmanshipofthissmallpiece,whichwascommissionedbyKingFrancisI ofFrance,meldsdecorativeelementsfromtheFontainebleauSchoolwithsculpted figuresintheidiomofItalianMannerism.Suchworksofarthavenotcapturedthe

,goldandenamelsaltcellar(–).Thefemale figureofTellusrepresents earth;thetemplebesideherheldpepper.Themale figureofNeptunerepresentsthesea;the shipbesidehimheldsalt.The figuresinthebaserepresentthewinds,thetimesoftheday,and humanactivities.

publicimaginationbecausetheyarenotclassifiedas fineart.DuringtheRenaissance, however,artistsweremembersofcraftguilds,andinmanylanguagestheterms ‘artist’ and ‘artisan’ wereusedinterchangeably.

ThechapterbyPamelaLongandAndrewMorralloncraftandtechnologysetsaside moderndistinctionsbetweenartandcraft,andindeedilluminatestheconvergenceof artisanalandlearnedculturesduringtheRenaissance.The figuresonCellini’ssalt cellarareclassicalgodsdrawnfromthelearnedtradition.Thisdetailisindicativeof animportantphenomenon,whichistheintegrationoftheclassicalrenewalthatliesat theheartoftheRenaissanceintothedesignofcrafts.Aristocraticpatronagefacilitated thetransitionofclassicalthemesfromthelearnedworldtocraftedobjectsranging fromtapestriestotableware.Thetradesthatproducedthecraftandtechnologyofthe periodwereofteninnovativein fieldssuchasagriculture,shipbuilding,military technology,andfortification.

TraditionalnarrativesofthescientificrevolutiontendtorunfromCopernicus (aheliocentriccosmology)toNewton(auniversegovernedbyscientificlaws).Justas theRenaissancewasdeemedtobeginin withthefallofConstantinople,sothe scientificrevolutionthatheraldedthebirthofmodernsciencewasdeemedtobegin in ,theyearinwhichCopernicus’ Derevolutionibusorbiumcoelestium (Onthe RevolutionsoftheHeavenlySpheres),Vesalius’ Dehumanicorporisfabrica (Onthefabric ofthehumanbody),andtheGermantranslationofLeonhartFuchs’s Dehistoriastirpium (OntheHistoryofPlants)werepublished.PaulaFindlen’schapteron ‘TheRenaissance ofScience’ presentstheseaccomplishmentsastheculminationofdevelopmentsin scienceandmedicineinthecourseoftheRenaissance.Thehumanistre-examinationof thescienceandmedicineofclassicalantiquitypromoteddebatesabouthowbestto explainthenatureoftheuniverse,theplaceofhumanbeingswithinit,andthe physiologyofthehumanbody.

TheaspectsoftheculturallifeoftheRenaissancethataremostdifficulttorecover includetheperformingarts,whichcomealiveatthemomentofperformancebutleave littleevidenceoftheexperienceofthosewhowitnessthem.Someperformancespaces survive,suchastheTeatroOlimpicoinVicenza,asdowrittenaccounts, financial records,musicalscores,pictorialrepresentations,andarangeofartefacts,andperformancescaninsomemeasurebereconstructedfromsuchmaterials.Margaret McGowan’schapterontheperformingartsfocusesonfestival,music,drama,and dance,andshowshowtheseformsareshapedbytheknowledgeofclassicalantiquity promotedbythehumanistscholarsoftheRenaissance.Thisisathemethatanimates andconnectsallthechaptersinthisvolume.

( –)wasdesignedbyAndreaPalladioandVincenzo Scamozzi.Thestageandsemi-circularseatingwereinspiredbythedescriptionofanancient theatreinVitruvius’ OnArchitecture.TheperspectivalscenerywasaRenaissanceinnovationbased ontheworkofSebastianoSerlio.Thetheatreisstillusedforplaysandconcerts.

HumanismandtheClassical Tradition

humanismwasascholarlymovementwhichprofoundlychanged Europeansocietyandintellectuallife.Bytheendofthesixteenthcenturytheeducationalreformsinstigatedbythehumanistshadalteredthelivesandwaysofthinking ofelitesthroughoutEuropeandtheNewWorldofAmerica.Eventodayourideasof proportionandbeautyinbuildingsandliteraryworksaredeeplyinfluencedby classicalidealsrevivedandtransformedintheRenaissance.

Humanistsoccupiedthemselveswitharangeofstudiescentredoncuriosityabout theworldofclassicalantiquity.TheyaspiredtowriteLatinproselikeCicero,tostudy andinterpretLatinliterature,tocollectmanuscriptsofancientwritersandtousethose manuscriptstoimprovetheirtexts,tolearnGreek,tounderstandancientGreekpoetry andphilosophy,andtowritepoetryandhistorywhichfollowedclassicalmodels.They werehungryforfactsaboutthehistory,customs,andbeliefsoftheancientworld,and theytriedtousetheirknowledgetoguideconductintheirowntime.Theysoughtto maketheirdiscoveriesaboutpaganclassicalliteratureandthoughtcompatiblewiththeir Christianbeliefs.Abovealltheirgoalwastobecome,andtoenableotherstobecome betterpeople,throughtheirunderstandingofthegreatnessoftheclassicalpast.

Renaissancehumanismsponsoredarevolutionineducation.InthehistorianPaul Kristeller’sinfluentialdefinition,humanisticstudies(studiahumanitatis)bythemidfifteenthcentury ‘cametostandforawell-definedcycleofstudies’,whichincluded grammar,literarystudies,rhetoric,poetics,history,andmoralphilosophy.Butthiswas thecoreratherthanthelimit.Scholarstrainedinhumanisticsubjectsturnedtheir attentiontoimprovingtextsandtranslationsoftheBible,topoliticaltheory,toother fieldsofphilosophy,includingcosmologyandthenatureofthesoul,andtotheology. TheFlorentineMarsilioFicino(–)wasasmuchahumanistinhisattemptto makePlatonicphilosophypartofChristianityashewasinhistranslationsfromGreek intoLatinforCosimode’ Medici.ThetheoristsandsupportersoftheReformationand

theCounter-Reformationweretrainedbyhumanistsandintheirturnencouragedthe growthofhumanisticeducation.

Renaissancehumanismreliedheavilyontheworkofmedievalscribesandscholars. IftheCarolingianscribeshadnotcopiedclassicalmanuscriptsintheninthandtenth centuriestherewouldhavebeenveryfewoldLatinmanuscriptsforhumanistscholars to ‘discover’ anddisseminate.IfLatinhadnotbeenrevivedintheninthcenturyand thencontinuedtobetaughtasthelearnedlanguageofEuropethroughoutthelater MiddleAgestherewouldhavebeennobasisfromwhichhumanistscouldurgea returntothestandardsofclassicalLatinity.Medievalscholarsandrulerscreatedthe universitiesandtheEurope-widenetworkoflearningwhichRenaissancehumanists lateradorned.Althoughhumanistscholarstriedtoenhancetheirsignificanceby denigratingtheprecedingMiddleorDarkAges,modernscholarsacknowledgecontinuitiesbetweenmedievalandRenaissancelearning.Weneedtoinsistthattherewas changebutthatinmanycasesitbegangradually.Thetextsandteachingmethodsof early fifteenth-centuryhumanistgrammarschoolsdifferedonlyinsomeemphases frommedievalschools,butbythemiddleofthesixteenthcenturythedifferencehad becomemuchgreater.WriterslikeMachiavelliandMontaigneareunthinkableinthe MiddleAgesandarethedirectproductsofhumanistapproachestotheancientworld.

AlthoughtheoriginsofRenaissancehumanismlaywithPaduanteachersofletterwritingandindependentscholarslikePetrarch(–),thecrucialsupportforthe earlydevelopmentofhumanismcamefromnobleandcivicpatronage.Owninga libraryofclassicaltextsoremployinganambassadorwhocoulddeliveracompetent neo-classicalLatinorationbecameamatterofprestigeforItaliancitiesandcourts, whichweresoonimitatedinthatregardbythemagnatesandkingsofotherEuropean countries.Thesuccessofhumanistsinpersuading firstthecivilservantsandthenthe rulersofFlorenceandRomeoftheexternalpublicityvalueofclassicallearningwas essentialtothediffusionofthehumanistmovement.Humanistsoccupiedimportant administrativeanddiplomaticposts.Theybecamechancellorsofcitiesandstates; someevenbecamepopes.Theysometimessucceededindisplacingthehereditary nobilitytobecomethetrustedcounsellorsofrulers.

Thespreadanddevelopmentofhumanismdependedonschools.ItisacharacteristicofnorthernEuropeanhumanism,whichinmanywayssurpassedItalianhumanismafterabout ,thatthemostimportanthumanistsdevotedthemselvestothe reformofschoolsandtowritingnewtextbooks.Secularandreligiousprinceswereina positiontofoundnewschoolsandcolleges,andtoreformthesyllabusofexisting institutionsoflearning.TheRenaissanceismarkedbywidespreadwritingabout educationalreformandbytheelaborationofnewprogrammesformanyschools whichinthesixteenthcenturyhadmanysharedfeatures,bothacrossthenewly developingnation-statesandacrossEuropeasawhole.Theseeducationalreforms werethemostfar-reaching,enduring,andinfluentiallegacyofhumanism.

Afurthercrucialmotorforthedevelopmentofhumanismwasprovidedbythe inventionanddiffusionofprinting.Althoughmanuscriptsremainedmorebeautiful

andmoreprestigiousintermsofaristocraticcollectingwellintothesixteenthcentury, theadventofprintmadeitpossibletocirculateanewlydiscoveredornewlyimproved textrapidlyanduniformlythroughoutEurope.Thereductioninthepriceofbooks madeitpossibleforscholarsandstudentstoownseveraltextsonthesamesubject wherepreviouslytheymighthavebeencontentwithone.TheEurope-widedistributionachievedbyprintersinthemajorcentreslikeVenice,Paris,Basel,andFrankfurt gaveauthorsofnewLatinscholarlyworkstheincentiveofknowingthattheirideas couldbespreadveryrapidlythroughoutEurope.

Asthenation-statesbecamemorepowerful,theeducatedelite,includingscholars, operatedinaseriesofbilingualworlds,inwhichLatinwastheinternationallanguage ofpoliticalandscholarlycommunicationbutthelocalvernacularwasthelanguageof thecourtsandofpoliticalpower.ThemaleelitewaseducatedinLatinbutthey increasinglyexpressedthemselvespubliclyinItalian,French,German,Spanish,and English.AnElizabethanbishopwouldwriteagainstthecontinentalRomanCatholics inLatinandagainstthelocalpuritansinEnglish.ImportantandinfluentialthoughneoLatininstructionalworkswere,theenduringlegacyofhumanismliesinvernacular literature,treatises,andBibletranslations.

OriginsofhumanismandPetrarch

LatinlearningandclassicalLatinliteraturecouldhardlyhavesurvivedinWestern EuropewithouttheactivitiesofIrishandEnglishmonksinthesixthtoeighth centuries.TheycultivatedLatingrammar,collected,read,andcopiedclassicalLatin texts,andeventuallyre-exportedLatinlearningtotheEuropeancontinentinthetime ofCharlemagne(–).Thetowering figuresherewereBede(–),whowrote Biblecommentaries,grammartextbooks,andworksonchronologyaswellashisLatin EcclesiasticalHistoryoftheEnglishPeople ( ),andAlcuin(c.–),whowascalled fromthecentreoflearningatYorktohelpCharlemagneestablishnewmonastic schoolsinhisempire,inFrance,Germany,andnorthernItaly.Intheninthcentury themonasteriesfoundedbyAnglo-Saxonmissionariesproducedcopiesofmostofthe classicalLatintextswhichhavesurvived,manyofthemwritteninthenewCaroline minusculescript,whichlaterhumanistsmisidentifiedastheancientRomanhandwriting,andreproducedintheitalicandromantypefaceswestillusetoday.Formanyof theclassicalLatintextswhichwereadtoday,asinglecopyhadsurvivedintotheninth century,whenmostofthemwererecopiedinsufficientquantitiestoincreasetheir chancesofrecovery.LupusofFerrières(c.–)collected,copied,andcollated manuscripts,encouraginghisfriendsandpupilstodolikewise.Whatwasrecovered intheninthcenturywasnevertrulylostagain;whilesometextslanguishedsafebut uncopiedinmonasticlibraries,otherswererecopied,especiallyinthegreatBenedictinemonasteryofMontecassinointheeleventhandearlytwelfthcenturies.Fromthe monasteriesLatinspreadtocourtsanduniversities,becomingtheinternationallanguageoflearningandhigh-levelchurchcommunication.ButthisformofLatinwas

stillalivinglanguage,muchinfluencedbythelocalvernacularsandinmanyways unlikethecarefulartisticLatinproseofclassicalwriterslikeCicero.

Asecondcrucialfactorintherevivalofancientlearningwasthepoliticallifeof Italiancity-statesinthethirteenthandfourteenthcenturies.By citieslikePadua, Florence,Venice,andSienahadestablishedrepublicansystemsofgovernmentin whichpoliticalspeech-makingwasanimportantpartofthefabricofcitylife.Atthe sametimeastheessentialfoundationsofmodernaccountancyandinternational bankingwerebeinglaid,manymerchantsinthesecitieswerewealthyenoughto demandaroleinpoliticalactivities.WhilehewasinexileinFrance,BrunettoLatini (c.–), firstChancelloroftheFlorentinerepublicandteacherofDante,wrotean ItaliantranslationofpartofCicero’srhetoricaltextbook, Deinventione,withacommentarywhichmadeconnectionstotheartofletter-writing.Atalmostthesametime RhetoricaadHerennium wastranslatedintoLatinbyGuidottodaBologna.Latinivalued whatCiceroandotherclassicalwriterscouldteachbut,inspiteofhisownLatin learning,hebelievedthatCicero’steachingsshouldbemadeavailabletoreadersof thevernacular.

Inthetwelfthcentury,interestinclassicalrhetorichadtakenadifferentturnwith thecompilationofartsofletter-writingwhichcombinedinstructionsforwriting varioustypesofofficialletterinLatinwithobservationsbasedonclassicalLatin rhetoric.Fromthelateeleventhtothelatefourteenthcenturydozensofletter-writing manuals(artesdictaminis)werecomposedandtheteachingofLatinletter-writing flourishedaspartofapracticaltrainingforofficialsandnotariesatthemarginsof medievaluniversities,notablyBologna.Accordingtooneschoolofthoughtthe earliesthumanistsweretheheirsofthewritersof artesdictaminis.Anotherschoolof thought,incontrast,seestheearlyhumanistsasassertingthevalueofclassicalmodels inanageofanti-classicism.Thecontextherewouldbetheanti-classicalpolemicsof theBologneseprofessorof dictamen,BoncompagnodaSigna(–).

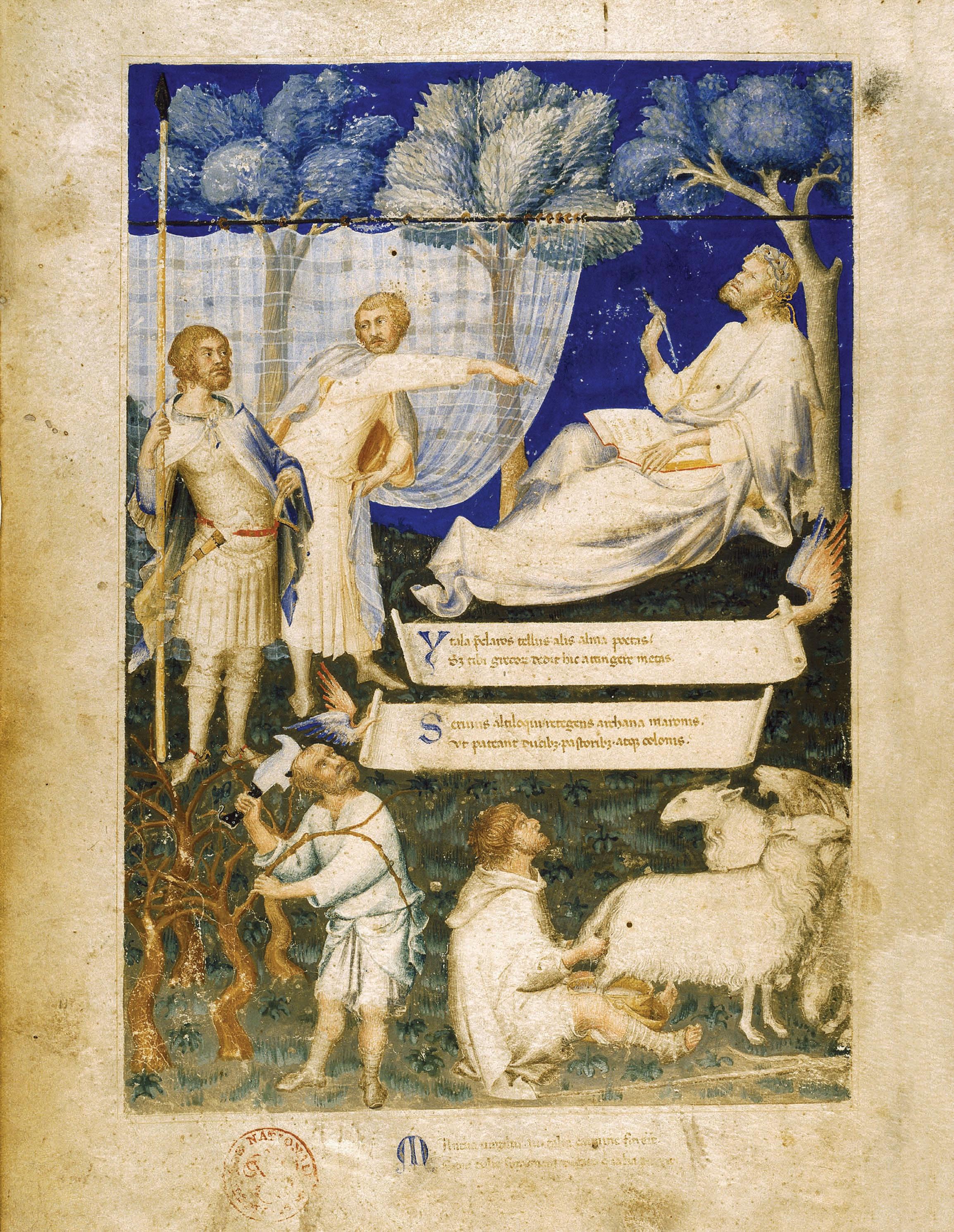

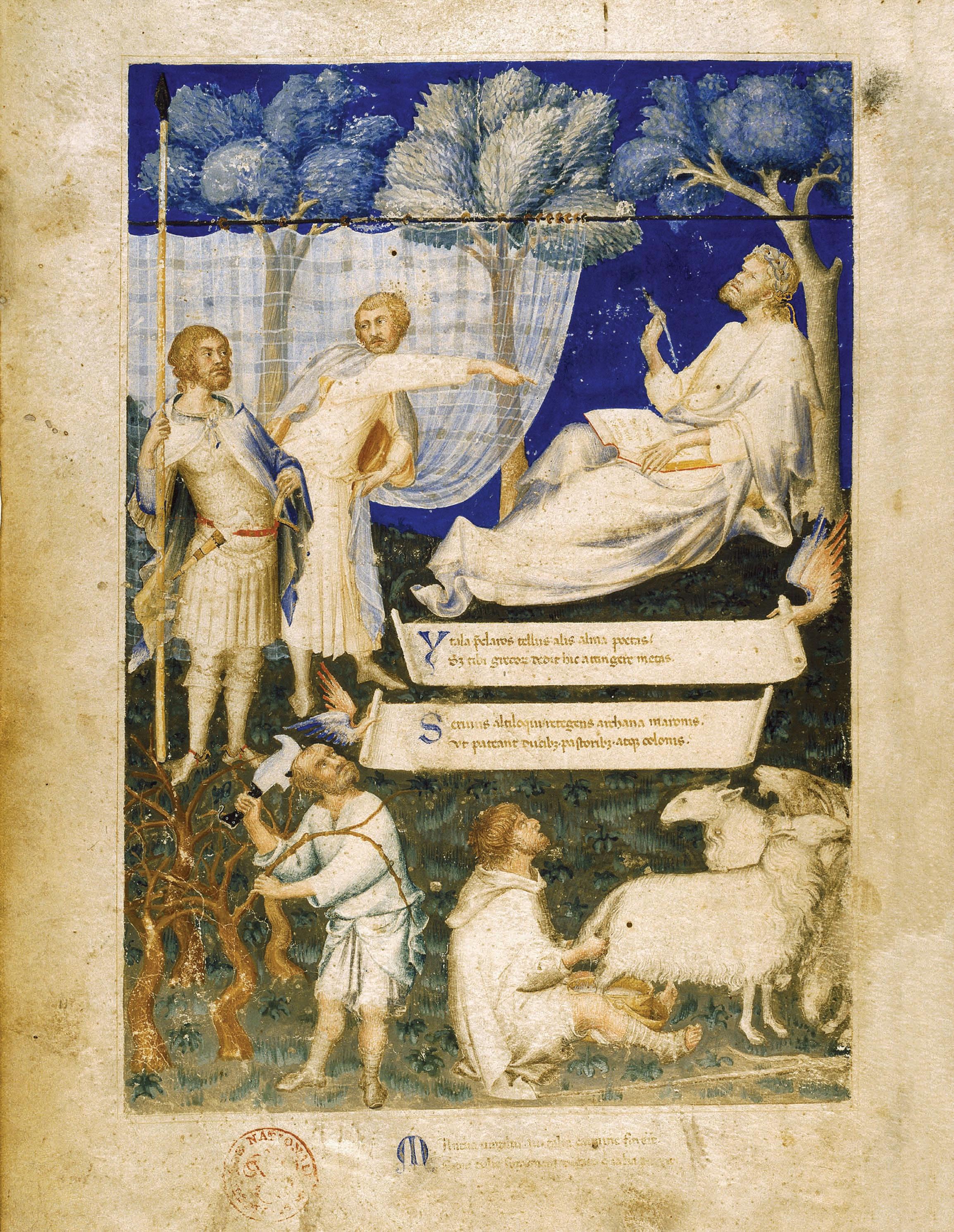

The firstofthehumanistswasthePaduannotaryLovatoLovati(–),who readwidelyinclassicallyricpoetryandcomposedLatinverseepistles,atreatiseon classicalLatinpoeticmetre,andashortcommentaryonSeneca’stragedies.Lovati’s pupil,thePaduannotaryanddiplomatAlbertinoMussato(–)wroteinLatina defenceofpoetry,ahistorymodelledonLivy,andaversetragedy, Ecerinis,modelledon Seneca’stragedies,whichwarnedhisfellowcitizensagainsttyranny.ThesePaduan earlyhumanistsexhibitedanenthusiasmforclassicalliterature,awishtounderstandit better,andadesiretoimitateLatinliteratureintheirownprivateandliterarywritings. Intheirpublicletterstheycontinuedtofollowthemodelsofthemedieval arsdictaminis. Opposite: ,FrontispiecetoPetrarch’sVergil.Petrarchcommissionedthis frontispiecefromthegreatSienesepainterSimoneMartiniinAvignonaround forhis manuscriptofVergil’sworks.ThefrontispieceshowsVergilwriting,thecommentatorServius openingthecurtain,andthree figuresrepresentingVergil’sthreegreatpoems,the Aeneid,the Georgics,andthe Eclogues.

FrancescoPetrarca(Petrarch)wastheoutstandingscholarandwriterofhisgeneration.ThesonofanexiledFlorentinenotary,hesoonabandonedhisownlegalstudies andtookadvantageoftheaccumulationofFrenchandItalianmanuscriptsofLatin textsaroundthepapalcourtinAvignon.Hecollectedandcopiedmanuscripts,putting togetherthemostcompleteversionofLivy’shistoryavailableinhisdayandpersonally correctingitbycomparingitwithothermanuscripts.HisLivyisthefamousBritish LibraryHarleymanuscript ,laterownedandcorrectedbyLorenzoValla.In Avignon,PetrarchcommissionedfromSimoneMartinithefrontispieceforhisVergil, showingVergil,Aeneas,andtheancientcommentatorServiusatthetop,withscenes illustratingthesubjectsofthe Eclogues and Georgics below.Healsofoundmanuscriptsof Cicero(theoration ProArchia andthe LetterstoAtticus)andPropertius.Hisownlistofhis favouritebooksincludesCicero,Seneca(MoralEpistles and Tragedies),ValeriusMaximus, Livy,Macrobius,AulusGellius,Vergil,Lucan,Statius,Horace(especiallythe Odes), Juvenal,StAugustine,Boethius,andaLatintranslationofAristotle’s Ethics.Heowneda manuscriptofHomer’s Iliad butheneversucceededinlearningenoughGreektoread it.InLatinPetrarchwroteletters(inproseandverse),philosophicaltreatises,pastoral poems,andanunfinishedepic, Africa,onthelifeoftheRomangeneralScipio Africanus.HestrovetoupholdclassicalstandardsofLatinexpressionandwrotebiting critiquesofthemisguidedthinkingandpooruseofLatinbyscholasticphilosophers andBritishlogicians.Hewasthe firstpost-classicalauthortopublishcollectionsofhis letters.Petrarch’snamelivestodaybecauseofhisItalianpoetryandparticularlyforhis Canzoniere,thecollectionofpoemscelebratinghisloveforLaura,whichwasmuch imitatedby fifteenth-andsixteenth-centuryItalian,French,andEnglishpoets.

TothefollowinggenerationofhumanistsPetrarchservedasanimportantmodelin severaldifferentways:forthebreadthofhiscuriosityabouttheancientworld;forhis wideknowledgeofLatinliteratureandhisattempttorelatethisknowledgetohisown experience;forhisdiscoveryofnewmanuscriptsandnewtextsandhisattemptsto improvethetextsofworksheknew;forhisattemptstowriteLatinpoemsandletters worthyofcomparisonwithclassicalLatin;forhiscritiqueofscholasticLatinity;and forhisambitiontolearnGreek.

Italianhumanismofthe fifteenthcentury

ColuccioSalutati(–),ChancellorofFlorenceforthirtyyears,wasamong Petrarch’scorrespondents.LikePetrarchhesoughttoimprovethetextsofLatin authorsandbuiltupalargelibrary,unitingforthe firsttimeforcenturiesCicero’s LetterstoAtticus withthenewlydiscovered LetterstohisFriends,aCarolingianmanuscript foundinthecathedrallibraryofVercelliin .Healsoownedtheoldestcomplete manuscriptofthepoetTibullusandoneofthethreeprimarymanuscriptsofCatullus. HisprivatelettersimitatedCicero’s.HeestablishedGreekteachinginFlorencewhenhe persuadedManuelChrysoloras(–)tolectureattheuniversitybetween and .ChrysolorastaughtGreektothenextgenerationofFlorentinehumanists

andencouragedthemtomaketranslationsfromGreekintoLatin,notaccordingto theoldwordbywordmethodbutattemptingtoformulatetheideasexpressedinthe GreektextingoodLatinsentences.Hecomposedagrammar(Erotemata)fortheuse ofWesternEuropeanstudents,whichbecamethe firstGreekgrammartobeprinted (in )andwasusedbyErasmusandReuchlin.SalutatialsoengagedGiovanni Malpaghini(–)toteachrhetoricinFlorence.Accordingtothehistorian RonaldWitt,thiswasthedecisivepointatwhichpublicletter-writingbegantoprefer classicalmodelsofLatinepistolographyoverthemedieval arsdictaminis. AmongChrysoloras’spupilswasLeonardoBruni(–),whotranslatedAristotle’s Politics and Ethics intoaLatinwhich fittedwithhumanisttheoriesoftranslation andideasofLatinstyle.HealsotranslatednineofPlutarch’s Lives andseveralofPlato’s dialogues,including Phaedo,Apology,and Gorgias intoLatin.HeusedGreekhistorians suchasPolybiusandXenophonforhisLatinhistoricalcompilations OntheFirstPunic War,OntheItalianWar,and CommentariesonGreekMatters.BrunilaterbecameChancellor ofFlorenceandwroteinLatina PraiseoftheCityofFlorence ()anda Historyofthe FlorentinePeopleinTwelveBooks (–).HewroteItalianbiographiesofPetrarchand Dante.BruniorganizedaprogrammeofItaliantranslationsofhisLatinworks.His On theFirstPunicWar wasthesubjectof fiveseparateItaliantranslationsinthe fifteenth centuryandsurvivesin vernacularmanuscripts.Itwasprintedtwelvetimesin Italianbefore ,asagainst fiveLatineditions.Evidentlytherewasagreatdemand forRomanhistoryinthevernacular.AlthoughBruni’sscholarshipandhistorywere firmlybasedonhisknowledgeofGreekandhiscommitmenttoagoodclassicalLatin style,hebelievedinusingthevernaculartospreadthebenefitsofhumanistlearning. AnotherpupilofChrysoloraswasthegreateducatorGuarinoGuarini(–), whofollowedhismasterbacktoConstantinople(–)inordertoperfecthisGreek andtoacquiremanuscriptsofGreektexts.GuariniranaprivateschoolinVerona (–) andthenestablishedacourtschoolinFerrara(–).Theemphasisofhis teachingwasongivingpupilsknowledgeaboutallaspectsoftheancientworld, teachingthemGreek,andhelpingthemtoacquireaLatinwritingstylewhichapproximatedtoclassicalstandardsofexpression.Hismethodofreadingfocusedonstyle,and onteachinghispupilstocollectvocabulary,maxims,andliteraryexamplesofthe employmentof figuresofrhetoricforuseintheirowncompositions.Healsoput considerableemphasisonteachinghispupilstheprinciplesofclassicalrhetoric,theart ofcomposingspeechesandothertexts.Hewroteanewcommentaryontheanonymous RhetoricaadHerennium,whichmostpeopleuptothemiddleofthesixteenth centurybelievedtohavebeentheworkofCicero,andwhichhadbeenthemost important firstprimerofrhetoricsincetheMiddleAgesandcontinuedtobeso.His commentaryfocusedontheliteralteachingofthetext,commentedindetailonits languageandstyle,providedcontextualinformationfromancienthistory,andgave examplesfromCicero’sorations,especially ProMilone,whichshowedtheuseofthe doctrines.HemakesmanyreferencestoCicero’srhetoricalworksandtothe firstcenturyRomanrhetoricianQuintilian.Hismethodofgrammarschoolteachingwas