The Orator Demades

Classical Greece Reimagined through Rhetoric

SVIATOSLAV DMITRIEV

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dmitriev, Sviatoslav, author.

Title: The orator Demades : classical Greece reimagined through rhetoric / Sviatoslav Dmitriev.

Description: New York, NY, United States of America : Oxford University Press, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020030316 (print) | LCCN 2020030317 (ebook) | ISBN 9780197517826 (hardback) | ISBN 9780197517840 (epub) | ISBN 9780197517833 (updf) | ISBN 9780197517857 (online)

Subjects: LCSH: Demades, approximately 380 B.C.–319 B.C. | Rhetoric, Ancient. | Oratory, Ancient. | Orators— Greece—Athens—Biography. | Politicians— Greece—Athens—Biography.

Classification: LCC PA3948.D35 D55 2021 (print) | LCC PA3948.D35 (ebook) | DDC 885/.01—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030316

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020030317

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197517826.001.0001

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Integrated Books International, United States of America

matri optimae in memoriam patri carissimi

Preface

The roots of this book go back to June 2010, when an unexpected e-mail arrived, conveying an invitation for me to participate in Brill’s New Jacoby project and offering a choice from a list of personalities. Among my picks was Demades, a politician from classical Athens, because I remembered him from classes on Plutarch at Moscow University (who presented Demades as an arrogant and immoral enemy of Demosthenes), and because of my old interest in classical rhetoric, for which there never had been enough time. The task seemed easy. Demades was a marginal figure who received limited attention from ancient authors: Jacoby’s less-than-one-page entry (FGrH 227) comprised only two texts—the Suda, δ 414 and a later commentary on Hesiod’s Theogony 914—and made references to two works allegedly by Demades: the History of Delos and the Record (Rendered) to Olympias on His Twelve Years. My new, more-than-400-pages-long entry on Demades included almost 280 texts, divided about evenly into testimonia and fragmenta.

Even more important, this evidence revealed a difference between the historical Demades, of whom we know very little, and the rhetorical Demades, a product of the Roman and Byzantine periods that generated most of the available information we have about him. Explaining how and why this later Demades emerged centuries after his historical prototype was possible only by contextualizing him within the rhetorical culture of those periods. This task required a separate project. It grew naturally into an examination of educational and literary practices that were inseparably connected with the development of rhetoric as a professional field, and the ways in which the figure of Demades and other historical characters were molded to accommodate later intellectual, social, and literary conventions. The project finally took the shape of a book when such evidence about Demades was used as one facet of a larger picture of later rhetors and sophists fabricating a distorted image of

Preface

classical Greece, which continues to dominate modern scholarship and popular culture.

It was a pleasure to work once again with Stefan Vranka and his amazing team of collaborators at Oxford University Press. This book is dedicated to my mother, Galina N. Dmitrieva, in memory of my father, Victor N. Dmitriev (1939–2016).

Introduction

Approximating the historical Demades

For what gives more courage to men who are afraid than the spoken word?

Dio Chrysostom 18.2

Unlike Alexander the Great and Demosthenes, his contemporaries, and acquaintances, Demades has never been an average household name. He is known, however, as the only Athenian who always managed to stay on good terms with both the irascible and impulsive Alexander III (the Great) and his more cunning and self-controlled father, King Philip II of Macedonia. Demades far outstrips all of his contemporaries in the number of surviving inscriptions with decrees adopted in the Athenian assembly from his proposals (see Chapter 1). His quick wit, powerful extemporaneous speeches, and outstanding diplomatic skills were praised centuries later. Relying on ancient accounts, modern studies agree that after Philip and Alexander decisively defeated Athens and her allies in the battle of Chaeronea in 338 b.c. with a thousand Athenians dead, two thousand captured, and scores fleeing the city in fear of her impending siege and destruction—Demades’s skilful oratory persuaded Philip to restore the Athenian dead and prisoners of war free of charge, and helped to arrange a peace treaty that was unexpectedly favorable to Athens. Ancient authors also tell how, when Philip died in 336, Demades kept the Athenians from joining the revolt by the city of Thebes against the young Alexander, thus saving them from the fate of the besieged Thebans. A furious Alexander had the remaining Theban men killed, women and children sold as slaves, and the city razed to the ground. He then demanded that the Athenians surrender several anti-Macedonian politicians, including Demosthenes, and threatened Athens with destruction if its citizens resisted. We read that, unlike some who refused to interfere in this conflict, fearing for

The Orator Demades. Sviatoslav Dmitriev, Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197517826.003.0001

their lives, Demades eagerly volunteered to go to Macedonia and succeeded in persuading Alexander to drop his demand. He thus once again saved his fellow citizens and the city. Our sources tell us that, in addition to issuing a special decree in his honor, the people of Athens rewarded Demades with a bronze statue in the marketplace and the right to a daily free meal (along with the city councilors on duty) for himself and his descendants. He is thought to have been the first of the Athenians to receive all of these exceptional privileges—during his lifetime—and did so long before Demosthenes, who obtained such honors only posthumously.1 When Alexander departed on his campaign to the east, Demades is said to have forestalled any military cooperation between Athens and the Spartan king Agis III, whose revolt against Macedonian rule in 331–330 ended in his defeat, his eventual death, and the final demise of Sparta. And, according to ancient texts, when Athens revolted over the news of Alexander’s death in 323, only to be defeated and humiliated by his general Antipater, Demades again stepped in and saved his city. After Phocion, famed as the people’s advocate, bluntly refused to travel for risky negotiations with Antipater, the Athenians once more turned to Demades. He readily agreed to undertake this mission, defended the interests of Athens before Antipater with dignity and force, and paid with the price of his life, and that of his son, for the sake of his city in 319. Together with the death of Alexander the Great and the suicide of Demosthenes in the following year, the execution of Demades marked the end of classical Greece.

It is puzzling, then, that despite Demades’s many valuable services to Athens, and all of Greece, he received predominantly negative treatment by ancient authors. Their disapproving attitude survived into modern works, beginning in the nineteenth century—when Demades first attracted the attention of scholars, who saw him as a “man without character or principle” and “accessible to bribes from whatever quarter they came, ever ready to betray his country and his own party”—and into our times.2 Several recent studies

1. Demades: Din. 1.100–101; Long. Inv. (544.21–545.11); Aps. 10.6; Lib. Or. 15.42, with Kralli 1999–2000, 136–138, 142–143, 147; see Chapter 9. The earlier honors of either a statue or the sitesis, which is the right to meals at public expense: Cleon (Aristoph. Equ. 167, 575, 709, 766, 1404), Conon and his son Timotheus (GHI 128: c. 375 b.c.; Dem. 20.70; Schol. Dem. 21.62 [200]), and Iphicrates (Dem. 23.130, 136; Schol. Dem. 21.62 [200]). See also Osborne 1981, 159 for Diphilus (“330s”; with a question mark), referring to Din. 1.43 and Dionys. Din. 11. Demosthenes: ps.-Plut. X Or. 847d and 850f–851c = Marasco 1984, 151–152, with MacDowell 2009, 424–426 and Canevaro 2018a, 73. Ps.-Plut. X Or. 843c, while claiming that Lycurgus received such honors during his lifetime, dated them to the much later archonship of Anaxicrates.

2. For example, Schmitz 1844, 957 (the quotations); Glotz 1936, 363: “he saw only his interest in politics”; Harding 2015, 59: “Demades cared about nothing but himself.”

have tried to reconsider the image of Demades, pointing to the many benefits of his policies for Athens.3 While this evidence is well known, however, such studies have failed to explain Demades’s mostly negative posthumous image; in fact, they have hardly ever raised this question. Another question that no one has ever asked is why more than one image of Demades has survived: ancient texts give divergent, and sometimes contradictory, descriptions of his looks, character, and oratorical style. A pot-bellied fellow for some, he was good-looking for others. Accusations of Demades as a dishonest politician and self-indulgent bon vivant coexisted with references to him as the author of philosophical and moralistic maxims. Some ancient accounts censured his oratory as flattery, while others commended him as an outspoken truthteller.4 Attempts to create a balanced view of Demades have failed to reconcile such disagreements in the sources. Although more recent reassessments of Demades have done their best to avoid some of the most odious clichés and grotesque epithets typically applied to him, problems still remain.

The most discordant of them is that any study of Demades necessitates interpreting the same evidence—about 280 texts that range from one line to several pages long—that largely postdates his death by three or more centuries. Some have accepted each text at face value, trying to connect it with a certain moment in his life, even though many of the texts contradict one another, dissolving the figure of Demades into irreconcilable images. Others have advocated a selective approach, sometimes interpreting references to Demades or his alleged quotations as genuine, while at other times discarding them as inauthentic. Treves, for example, rejected the genuineness of the fragment: “After Demades moved an illegal proposal and was censured by Lycurgus, someone asked him whether he looked in the laws when moving the proposal. ‘No, I did not,’ he said, ‘for they were in the shade of the Macedonian arms,’ ” while De Falco and Marzi accepted it as rendering Demades’s own words.5 This situation, which is characteristic of studies about 3. Williams 1989, 19–30; Marzi 1991, 70–83; Marzi 1995, 615–616, 619 n. 104; Brun 2000, 15, 39–40, 171–172; Squillace 2003, 751–752; Cawkwell 2012, 429.

4. Pot-belly: Athenae. 2, 44ef; Demad., no. 8 (112) = Sternbach 1963, 94, no. 242. Dishonesty: Diod. 10.9.1. Self-indulgence: Athenae. 2, 44ef; Plut. De cup. div. 526a. Flattery: Plut. Dem. 31.4–6; ps.-Max. Planud. Comm. Herm. (214.25–215.1); P.Berol. 13045.67–68. Good looks: Tzetz. Chil. 5.342–349. Moral behavior and sayings: Emp. Math. 1.295. Flattery and truth-telling: Chapter 5.

5. Demad., no. 1 (108) = De Falco 1954, 21, no. V = Sternbach 1963, 92, no. 235 = Marzi 1995, 640, no. V. Treves 1933a, 109–110; De Falco 1954, 25; Marzi 1995, 640, 645.

Demades, poses a question about what criteria might serve for authenticating the available evidence.

Two approaches for identifying genuine information about Demades have been suggested. The authors of the most comprehensive collections of evidence about Demades for their times, De Falco (1954, 38) and Marzi (1995, 665), proposed disqualifying those texts that were paralleled by descriptions of the same episodes involving other characters or the same quotations ascribed to different personalities. They thus rejected the authenticity of Demades’s proposal to count Philip II among Olympian deities, as mentioned in the Art of Rhetoric by Apsines (third century a.d.), since ps.-Maximus Planudes (the fourteenth century or later?) attributed a similar proposal to Demades’s fellow politician, the orator Aeschines.6 Although this method has obvious merits (without necessarily solving all the problems), the authors themselves have not applied it consistently. De Falco accepted references by such late authors as Tzetzes (c. 1110–1185) and ps.-Maximus Planudes to Demades leaving his son, still a youth, alone at the court of Philip, thereby catering to the king’s lustful advances, although these references replicated Demosthenes’s insinuations against Phrynon, a relatively distinguished contemporary Athenian political figure, also mentioned by Sopatros at a later date.7 De Falco and Marzi similarly acknowledged the above-mentioned reference to Demades’s words about the laws being shaded by the Macedonian arms as authentic, although the same phrase was also ascribed to Hyperides, one of Demades’s fellow politicians.8 De Falco and Marzi were likewise eager to consider an excerpt from one of Plutarch’s essays—“Phocion also, when Demades shrieked, ‘The Athenians if they grow mad, will kill you,’ elegantly replied, ‘And you, if they come to their senses’ ”—as referring to a certain disagreement between Phocion and Demades on clauses of the peace treaty between Athens and Macedonia, without identifying this treaty. Here, though, they are treading on dangerous grounds because elsewhere Plutarch described a similar altercation between Phocion and Demosthenes. While De Falco and Marzi were thus sidestepping their own method for identifying authentic evidence about Demades, Treves had already rejected the authenticity of this

6. De Falco 1954, 47, no. LXXXI; ps.-Max. Planud. Comm. Herm. (367.23–25). Demad., no. 1 (108) = De Falco 1954, 21, no. V = Sternbach 1963, 92, no. 235 = Marzi 1995, 640, no. V.

7. Tzetz. Epit. rhet. (677.12–14), and Chil. 6.16–17; ps.-Max. Planud. Comm. Herm. (377.12–14). Dem. 19.230. Sopatr. Comm. Herm. Stas. (631.29–632.1). De Falco 1954, 45. For this story, see Chapter 6.

8. See n. 5 above. Hyper. fr. 27–28 = ps.-Plut. X Or. 849a. De Falco 1954, 25; Marzi 1995, 640.

reference, interpreting it as an example of wordplay, precisely because Plutarch also mentioned a similar argument between Phocion and Demosthenes. Plutarch’s use of different characters undermines any attempts to associate this episode with some specific event.9 In what looks like a similar situation, Treves rejected the genuineness of Stobaeus’s words that “Demades compared the Athenians to flutes: if one takes away their tongues, there will be nothing left,” by pointing out that Aeschines used the same phrase. Even while noting this fact, De Falco and Marzi still accepted Stobaeus’s words as a genuine quotation from Demades.10

De Falco and Marzi justified their approach to the evidence by holding these doublets as phrases that Dinarchus, Aeschines, Demosthenes, and other Athenian orators originally voiced and Demades recycled.11 However, such justifications neither overturn the selective treatment of the surviving sources nor offer a good reason that Demades—counted among the best orators of the time—needed to recycle the statements of his contemporaries. Others, like Treves (1933a, 108 n. 1), chose to reject ascribing such references to Demades. The fallibility of establishing the authenticity of Demades’s expressions on the basis of their (alleged) use by other people is also revealed by occasional disagreements between De Falco, who accepted the above-mentioned story of Demades leaving his young son alone at the court of Philip as genuine, and Marzi, who left this account out of his collection of evidence about Demades specifically because Demosthenes made a similar accusation against Phrynon. In the end, this approach amounts to no more than personal choices. Additionally, it neither can nor does offer any help when we have more than one version of the same episode involving Demades, such as the case of three very different stories about Demades’s address to King Philip after the battle of Chaeronea. While De Falco, followed by Marzi, rejected the authenticity of the story by Sextus Empiricus because it included the same phrase that the philosopher Xenocrates allegedly uttered to Antipater at a later time, De

9. Plut. Praec. ger. reip. 811a; De Falco 1954, 33; Marzi 1995, 658. Plut. Phoc. 9.8, with Pelling 1980 on Plutarch’s reusing the same stories in his different works. Treves 1933a, 117 n. 3.

10. Stobae. 3.4.67 = Sternbach 1893, 159, no. 245 = ps.-Max. Conf. 54.22/23 (859). Treves 1933a, 108 n. 1. Aeschin. 3.229. De Falco 1954, 36; Marzi 1995, 663.

11. Dinarchus: Demad., no. 2 (109) = De Falco 1954, 24, no. XI = Marzi 1995, 644, no. XI. Aeschines: Stobae. 3.4.67 (see previous note). De Falco 1954, 36, no. LVII = Marzi 1995, 662, no. LVII. Demosthenes: Plut. Praec. ger. reip. 811a = De Falco 1954, 33, no. XLVII = Marzi 1995, 658, no. XLVII; Plut. Phoc. 9.8.

Falco acknowledged very different accounts of Demades’s address to Philip, by Diodorus and Stobaeus, as genuine.12

Lamenting the lack of a definitive criterion for determining authentic evidence about Demades, Treves (1933a, 121) pessimistically observed that, except for Demades’s famed witticisms, we do not see the man behind a “few incomplete fragments.” His words pointed to the other method used for identifying authentic passages by Demades—his oratorical style: references to his witticisms, aphorisms, metaphors, and concise sayings allowed ancient and modern authors to speak of Demades’s special style of oratory.13 As with the first method, however, relying on this style as the criterion for authenticity of the evidence about him has similarly produced diverse opinions. The genuineness of Demades’s humorous reference to his insatiable belly and privy parts was rejected by De Falco but accepted by Marzi as conforming to the style of Demades’s oratory.14 Conversely, while De Falco saw certain passages in the later text On the Twelve Years (see the Appendix) as originally belonging to one of Demades’s speeches, although he was unable to identify that speech, Marzi rejected the authenticity of those passages as not displaying features characteristic of Demades’s oratory.15 Such disagreements cast doubts on whether references to Demades’s style or his alleged quotations can prove their authenticity. Most importantly, style cannot serve as an authentication criterion, since not one of the six surviving literary texts mentioning Demades, which (allegedly) belonged to his lifetime, mentions his oratorical style,16 while, as ancient authorities acknowledged, Demades’s speeches were not available in writing.17 The only evidence of Demades’s style of oratory is therefore from much later sources, the earliest of which emerged three centuries after his death. One of them, ps.-Demetrius’s On Style, generally dated to the first or second century a.d., attributed the force of Demades’s speeches to

12. Diod. 16.87.1–2; Emp. Math. 1.295; Stobae. 4.14.47 (see Chapter 5). De Falco 1954, 33–34 and 38; Marzi 1995, 665–666. Xenocrates: Diog. Laert. 4.2.9 = Xenocr. fr. 109 = Isnardi Parente 2012, 45–52, Test. 2.

13. Ps.-Demetr. 282, with Chiron 2001, 304–305. For example, Gärtner 1964, 1456; Williams 1989, 20 n. 9. Discussions: Brun 2000, 22, 28–31.

14. Demades. no. 8 (112) = Sternbach 1963, 94, no. 242; Marzi 1995, 668, no. LXXI; De Falco 1954, 40, no. LXXI.

15. Ps.-Demad. Dod. 1–3; De Falco 1954, 28–29; Marzi 1995, 650, 669–670 (with n. 1).

16. Arist. Rhet. 2.24.8, 1401b.29; Dem. 18.285; Hyper. 1.25 and fr. 76; Din. 1 and 2.

17. Cic. Brut. 36; Quint. 2.17.13, 12.10.49.

“allusions, the employment of allegorical element, and hyperbole.”18 But what served as the foundation of these much later observations? It is not at all unreasonable to guess that they were derived from On the Twelve Years and other texts that circulated in the form of Demades’s speeches and sayings in later centuries. Attributing such evidence to Demades on the basis of his oratorical style and then using this material to illustrate that style creates a circular argument.

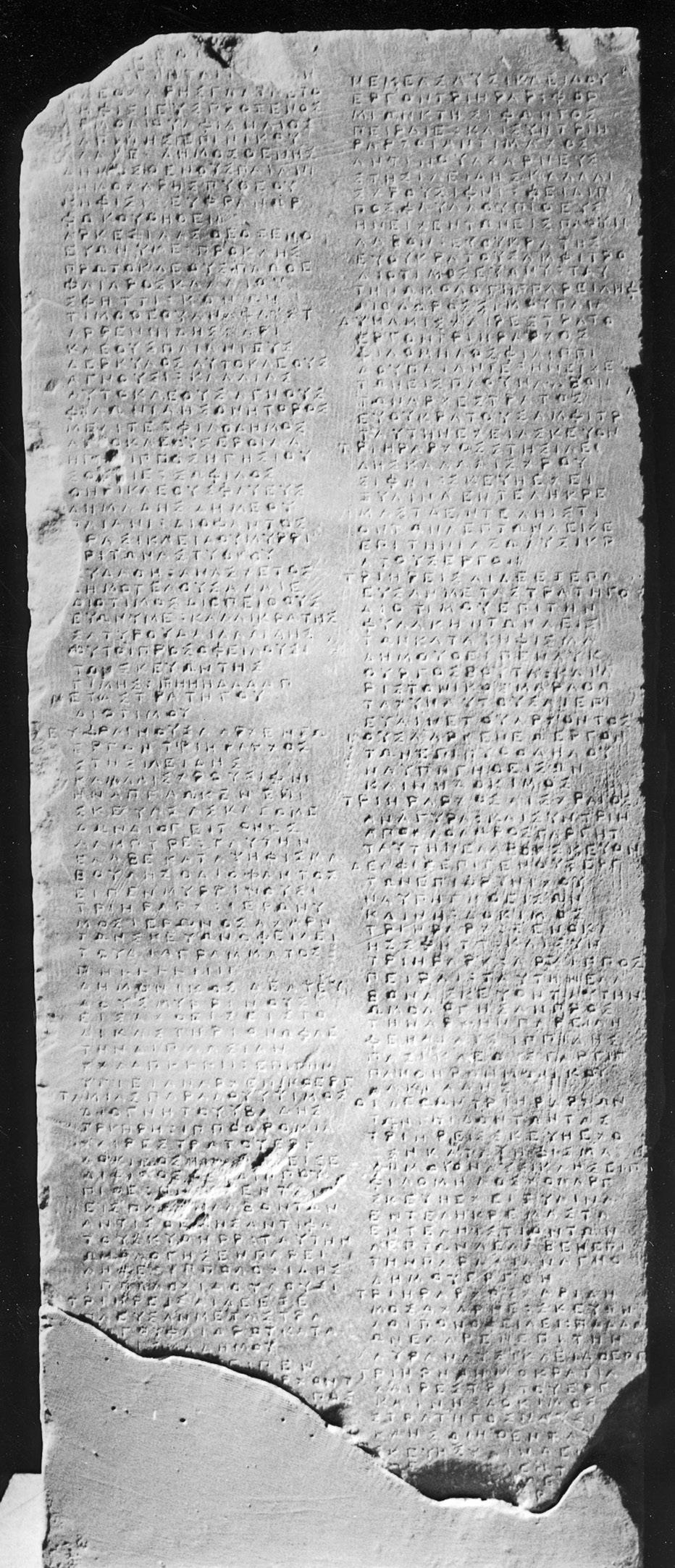

No viable method therefore exists for establishing the authenticity of the evidence derived from later texts. With the system’s justification built into the system, literary sources offer no solid foundation for reconstructing the historical Demades. This situation prompted Patrice Brun to seek an objective portrayal of Demades by focusing on evidence from his lifetime, most of which comprises a handful of inscriptions in the form of decrees, accounts, and honorific texts. As public documents, they were available for all to see and, although this accessibility does not guarantee that such texts necessarily provide objective information, they still appear to be more reliable than later literary works. Such an approach, however, can hardly achieve Brun’s declared aim. These few public inscriptions include only standard laconic formulas pertaining to certain aspects of Athenian administration and politics.19 They tell us nothing about Demades’s life, personality, and oratory. As insufficient sources of information, scarce bits of inscriptional evidence from Demades’s lifetime are traditionally rationalized by being woven into a consecutive narrative fabric together with later literary texts, which, as we have seen, offer contradictory references. Consequently, inscriptional evidence, too, receives diverse interpretations. Finally, limiting a study of Demades to the evidence from his lifetime does not solve—nor does it address—the problem of his many and diverse images in later texts.

The figure of Demades receives a different treatment in this book. Its basic premise is to distinguish between the actual person who lived in the fourth century b.c. and the fictional Demades, whose image acquired a life, or lives, of its own after the historical prototype passed away. The view of Demades as an influential politician who enjoyed his life to the full and who was always eager to crack a joke, and to rise and speak on the spur of the moment with

18. Ps.-Demetr. 282, 286, followed by Chiron 2013, 47.

19. Brun 2000, 33–34, with Brun 2013, 92 (distinguishing not so much between contemporary and later sources as between official documents and moralizing or partisan texts). For a critique of this limited approach, see Squillace 2003, 752–754, who, however, arrived (764) at essentially the same conclusion as Brun.

a ready tongue and a quick wit, made an attractive picaresque hero for many among the ancient scholars and even some from our times. A commoner with no written legacy, he had neither education nor edification, and the vulgarity of his oratory and character provided an instructive contrast to the professional training and polished morals of refined literati, who controlled intellectual life and education in later centuries. These images of Demades emerged during the Republican period, continued throughout the Roman Empire into late antiquity, survived until the fall of Byzantium in the midfifteenth century, and, eventually, found a safe place in modern works.

The book’s subtitle, Classical Greece Reimagined through Rhetoric, reflects the core of its argument: later authors reinterpreted the figure of Demades by their current educational and social norms, just as they retrospectively molded the vision of classical Greece. Multiplying, diversifying, and selfperpetuating, later images of Demades eventually concealed, obscured, and effectively replaced their historical prototype. While this chronological and geographical expanse embraced several historical periods with different social and political realities, it maintained a great deal of cultural continuity insofar as intellectual life and the system of education were rooted in the same material from classical antiquity. When examined within this cultural and intellectual context, evidence about Demades elicits several observations. Not all of this evidence was or had to be historically reliable: since many later accounts about what he did and said were only images created for a purpose, it is not necessary to connect every known reference to Demades with an actual historical event or to interpret it as his genuine words. Nor is it correct to indiscriminately use all available sources about him. This book therefore does not strive to assemble every known such reference—although almost all of them will be examined—conceding that the task to reconstruct the historical Demades is unattainable. The following pages aim to both delineate the emergence and rationalize the coexistence of his many diverse, and often contradictory, later images (which is virtually all that we have about him) within their social, intellectual, and educational context. Examining the origins and purpose of the demadeia, or the later fictitious rhetorical sources about Demades, exemplifies how and why later authors refurbished the overall appearance of classical Greece, creating a significantly distorted vision that still dominates academic scholarship and popular views.

This objective determined the structure of the book, which, unlike most previous studies that tried to weave every known bit of evidence about Demades into a narrative of his life, does not organize the surviving material chronologically. Instead, the book is structured thematically, around major

themes of social life, political activities, and educational practices across many centuries after his death. Part I centers on the world of real people, beginning with a critical overview of the available evidence about Demades; moving to the rise of rhetoric as the staple of education for members of the social and political élite—who perpetuated their cultural and social norms by shaping historical evidence through rhetorical exercises and declamations, or fictitious judicial and deliberative speeches; and, consequently, rationalizing images of Demades as reflections of the realities and mentalities of the educated class in later centuries. The other two parts look at how later authors developed and applied specific images of Demades. Part II studies the ways and methods with which exponents and students of rhetoric promoted their professional interests, using the figure of Demades to demonstrate the importance of rhetorical training that refined and accentuated political roles of the educated élite under the Roman Empire, including its interaction with outside authorities. Part III examines the uses of Demades in retrospective perceptions of the classical past, which have formed what has been termed “rhetorical history.” Its three chapters focus on how images of Demades helped later authors to develop and elaborate on their vision of famous events, like the Trojan War and the struggle of the Greeks against Persian invasions, the history of classical Greece and the campaigns of Alexander the Great, and, finally, Athens’ relations with other Greek city-states and with Macedonian leaders, from Philip II to Antipater and Cassander.

Making sense of the evidence

Orators prefer to live in a democracy, the worst form of government.

Philod. Rhet . (1 , 375: col. xcvii.3–8).

Philodemus characterized the régime of popular political representation and participation as someone who ended his life in observing the last convulsions of the Roman republic. Many intellectuals who lived both before and after him held the opinion that democracy—the rule of the people, regardless of their learning and social propriety—led to turbulence and instability. However, it was only in a democracy, in which the citizens made political and legal decisions after being persuaded by the speeches of their leaders, that oratory had real power.1 Limiting his reference to orators, Philodemus retrospectively reflected the reality of the classical period, when a politician had to be an orator, and it is in this sense that orators were juxtaposed with private citizens in classical Athens.2 It is also in this sense that Plato (Gorg. 503bc) and Demades’s contemporary Aeschines (1.25) labeled the famous fifth-century Athenian political leaders Pericles, Themistocles, and Aristides “orators,” whereas Demosthenes (18.242) lambasted Aeschines, his perennial political foe, as being, among other things, a “counterfeit orator.” The power, and potential danger, of orators were reflected by the procedure of scrutinizing orators (dokimasia ton rhetoron), which verified whether they were socially, legally, economically, and morally qualified to advise the People

1. On rhetoric developing out of democratic polis: Schofield 2006, 63–74; Bearzot 2008, 77–78; Erskine 2010, 272.

2. For example, Pl. Gorg. 513b. Wohl 2009, 163: “by the fourth century a ‘career politician’ was referred to simply as a rhetor” (and n. 5 with further bibliography). This juxtaposition: Dem. 10.70, 24.66; Aeschin. 1.165; Lyc. 1.31.

The Orator Demades. Sviatoslav Dmitriev, Oxford University Press (2021). © Oxford University Press. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197517826.003.0002

on matters of public policy,3 and by specifically distinguishing a legal action against orators, rhetorike graphe, from a general graphe paranomon, the suit for bringing an illegal proposal, in later texts.4

Orators did not merely prefer to live in a democracy. They were a necessary feature of a democratic state that made all decisions through argument and persuasion. The power of persuasion gave oratory, and orators, an integral and oftentimes decisive place in public life.5 Characterizing democracy as being inherently connected with public speaking, Thucydides’s Cleon (3.38.5–7) castigated late fifth-century Athenians, saying, that

what each of you particularly wants is to be able to make a speech himself, and, if not, to contest with those who can speak in this way by not appearing to lag behind an argument, by praising an argument before it had been completed, and by being as quick at seeing how a point will be made as you are slow at foreseeing what it will lead to. Searching for something other, so to speak, than the circumstances in which we live, you do not think about the reality of present circumstances. You are simply slaves to the delight of listening, and more like spectators of a sophist than men deliberating on the affairs of the state.

Similarly marking the rising popular interest in the beauty and adornment of public speaking at the expense of its practical content and societal orientation, Plato reflected on the importance of public oratory when he identified politicians as orators (Gorg. 513bc), arguing that oratory had to be moral and oriented toward the public good (502d–518e), and blamed Pericles for having made Athenians talkative and idle (515e). Regardless of whether such criticisms were justified, they highlighted the importance of public oratory to Athenian democracy and its continued appreciation in much later times: Plutarch noted the reference by Stesimbrotus from the fifth century b.c. to the power and readiness of speech as characteristic of Attic dwellers, while, in the first century b.c., Diodorus rationalized Demades’s persuasiveness by referring to

3. Dem. 22.21–23; Aeschin. 1.28, 32, 186, 196; Din. 1.71; Lyc. fr. 5.1a (= Harp. δ 74), b (= Schol. Aeschin. 1.195 [387]); Borowski 1975, 82–103; MacDowell 2005, 80–81; Feyel 2009, 198–207; Todd 2010, 77–78, 102, 105. Solon’s alleged regulation on the order of speakers in the Assembly: Aeschin. 3.2–3 with Leão and Rhodes 2015, 137–138.

4. This interpretation of the rhetorike graphe: Harp. ρ 3; Phot. Lex. ρ 107 (321); the Suda, ρ 151.

5. The role of orators: Ober 1989, 314–324 (and 165–177 on the dangers of oratory); Mossé 1995, 136–153.

the “Attic charm” of his speaking.6 Other régimes needed no political oratory. By the late fourth century, after the classical Athenian democracy came to an end, public speaking turned into the refined art of rhetoric. Its initiates curried the admiration of educated élites and impressed Roman officials, including emperors. Few of them, however, were active in politics, and none was a politician in the same sense as in classical Athens. Nor was their audience a mass of deliberating citizens who made decisions by themselves and for themselves.

During Demades’s lifetime, which covered a larger part of the fourth century, the primary political concern of the Athenians was their relations with the Macedonian kingdom.7 Long relegated to the margins of Greek political life, Macedonia experienced a spectacular rise to political stability, military might, and territorial expansion under the rule of Philip II (c. 360–336). Not lacking in personal charm, he unleashed a whirlwind campaign of bribery, diplomacy, and military action to establish control over a large part of the Greek world, eventually forcing other Greeks to put aside their disagreements and join forces against him. Athens played a singular role in the Greeks’ attempts to stop Philip’s push for domination, with Demosthenes as the most vocal of the anti-Macedonian politicians in Greece. In addition to Philippics, his famous speeches against Philip, Demosthenes served on diplomatic missions, forging alliances, collecting money, and shoring up support for Greek citystates that were being attacked or threatened by Philip. In 340, after the breakdown of the shaky peace of Philocrates that had been established between Philip and Athens in 346 and amended twice, the Athenians found themselves at war against Philip. He decisively defeated the Greek army, led by Athens and Thebes, in the battle of Chaeronea in 338, in which the Athenians suffered a thousand dead and two thousand captives.8 According to ancient and most modern authors, the battle that sealed the fate of Greece also proved to be a watershed event for Demades, marking a sudden beginning to his political career. He orchestrated a peace treaty that gave the Athenians safety and security for the next fifteen years—although their relations with Philip

6. Plut. Cim. 4.4; Diod. 16.87.3. For the discussion of this evidence, see Chapter 5.

7. While the death of Demades is universally put in 319, his birth is dated to either c. 390 (Osborne and Byrne 1994, 103 [4]; Harding 2015, 58) or the early 380s (Gärtner 1964, 1456; Davies 1971, 100; Weissenberger 1997, 415; Brun 2000, 12 n. 5) or the period between 388 and 380: Marzi 1991, 71 and 1995, 623; Squillace 2013, 1988–1989.

8. Treves 1933a, 113; De Falco 1954, 93–94; Williams 1989, 21. The peace of Philocrates: Dmitriev 2011b, 67–73.