ListofFigures

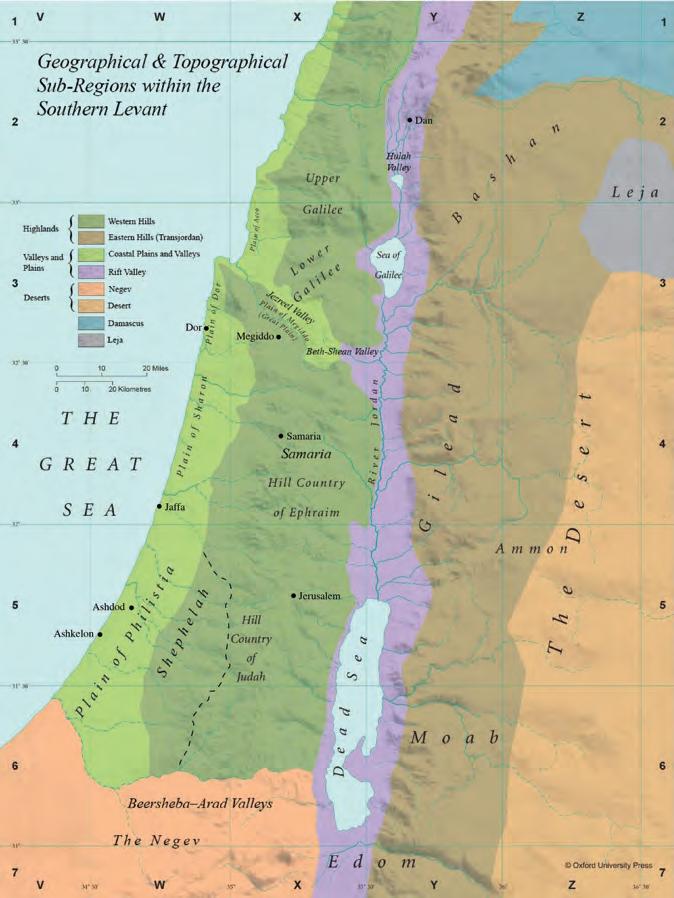

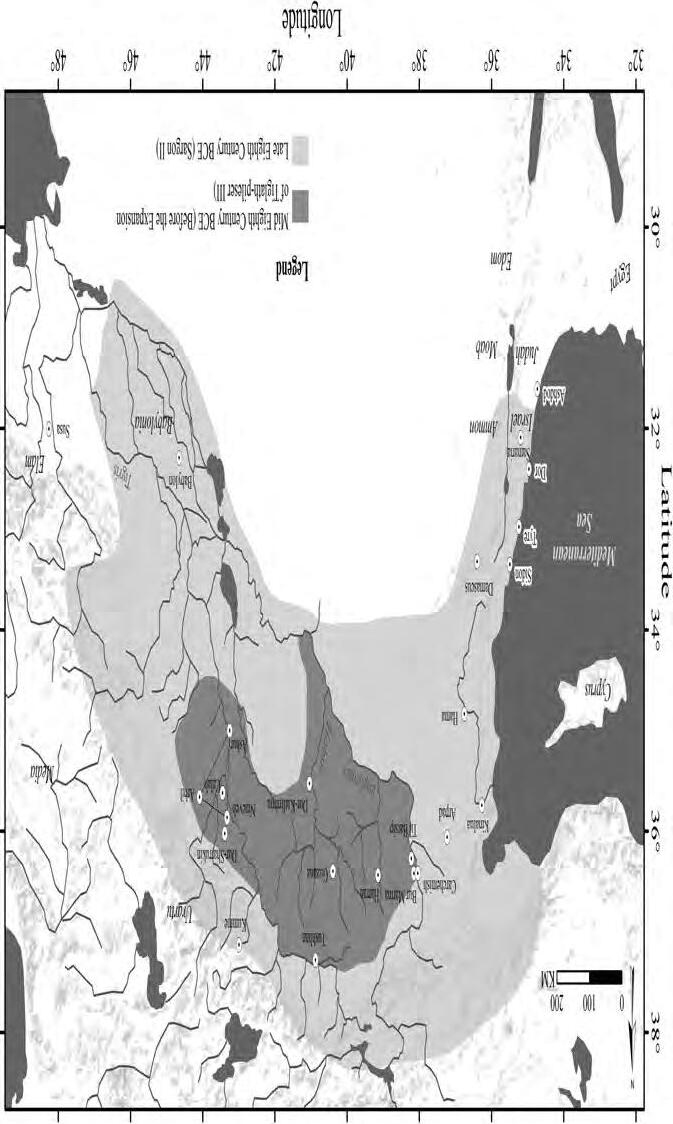

1.1MapoftheSouthernLevant,withthemainthegeographicalsub-units7

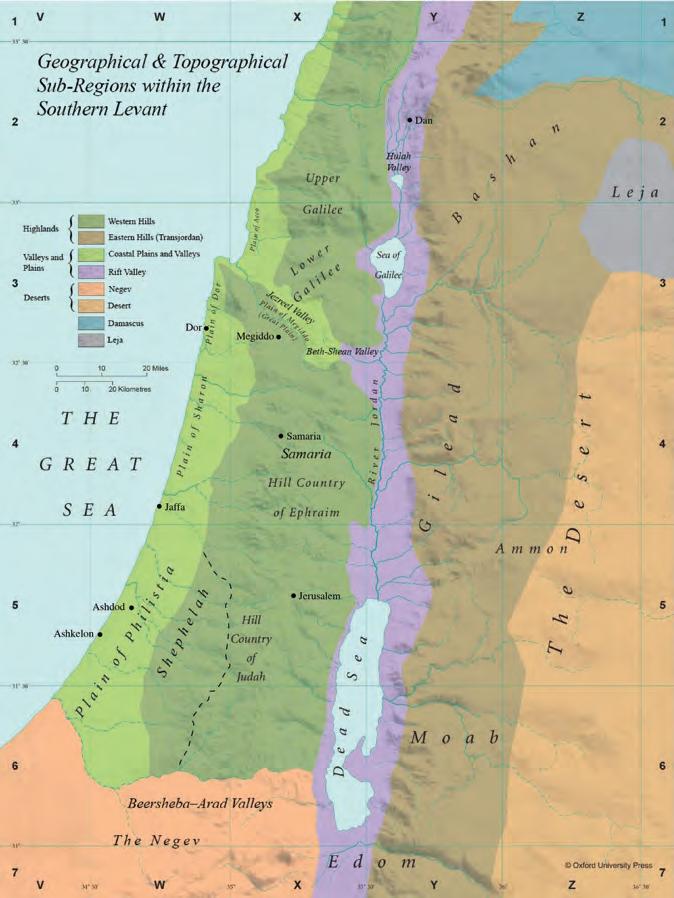

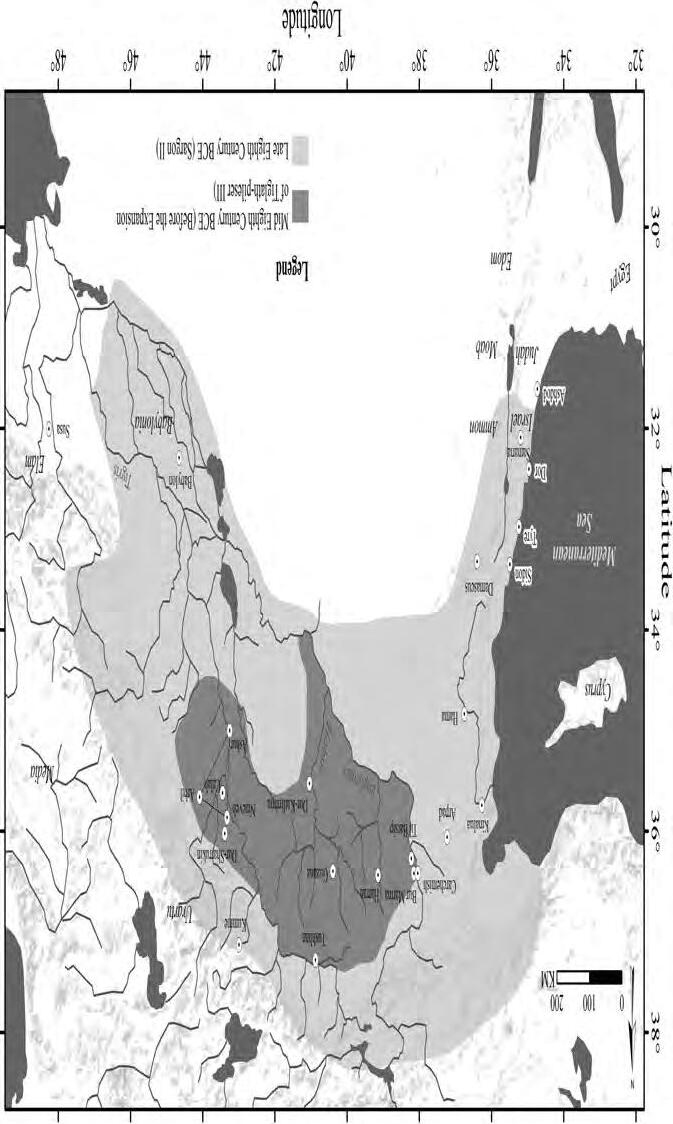

1.2MapoftheAssyrianEmpire,noting ‘theAssyriantriangle’,and highlightingtheextentoftheempireinthemiddleoftheeighth century ,andtheareasconqueredinthesecondhalfofthiscentury (mostlybyTiglath-pileserIII)9

2.1MapofsitesmentionedinChapter239

2.2SettlementhierarchyinthekingdomsofIsraelandJudah52

2.3SocioeconomicstratificationinthekingdomofJudah57

2.4SocioeconomicstratificationinthekingdomofIsrael57

3.1SchematicmapdetailingtheAssyrianexpansionintheSouthernLevant66

3.2AnAssyriandestruction:aphotodepictingthedestructioninoneof theroomsinbuilding101(room101D),atTel ‘Eton68

4.1MapofsitesmentionedinChapter474

4.2Acomparisonofeighth-andseventh-century settlement hierarchiesintheterritoriesofthekingdomofIsrael104

5.1SchematicmapoutliningtheproductionzonesinthelandofIsrael intheseventhcentury 120

5.2Schematicchartofthedistributionofoliveoilsurplusesproduction centresintimeandspace(roundeddates)137

6.1Mapshowingthemainsitesmentionedinthetext142

6.2PlansofvariousstructuresthatwereinterpretedasAssyrianresidencies intheSouthernLevant:(a) ʾAyyeletha-Šahar;(b)Hazor,building3002; (c)Megiddo,structures1052,1369152

6.3PlanofAssyrianMegiddo155

6.4PhotosoftheAssyrianpalaceatAdHalom,nearAshdod156

6.5PlatewithAssyrianPalaceWares160

7.1Schematicmapofthesouthwesternprovinces,indicatingareasofactual Assyrianactivity183

7.2Thewedged-impressedbowls189

7.3(left)Ageneralmapofthecountry(withthelocationofthedetailedmap indicatedonit);(right)DetailedmapoftheApehk-Gezerarea196

10.1AschematicmapdescribingtheadvanceoftheAssyrianarmyin theSouthernLevant,andthedevastationofmanyregions,especially thoseannexedbytheempire265

Acknowledgements

Thisbookwasalongtimeinthemaking.MyinterestintheAssyrianempire grewoutofmyworkontheIronAgeII,butmy firstexplicitdiscussionofthe AssyrianpoliciesinthesouthwestgrewfrommyjointresearchwithEhud Weissontheeconomyofthe7th century(FaustandWeiss2005,later developedintoFaustandWeiss2011).Thisresearchwas,unintentionally, initiatedin2002whenwewerebothcarryingoutpostdoctoralresearch(on completelydifferenttopics)atHarvard.Webeganourcollaborationinan attempttounderstandthebotanical findsat7th centuryAshkelon,butwe quicklyrealizedthatthecitywasembeddedwithinamuchlargereconomic systemandcouldnotbestudiedinisolation.Understandingthelargereconomyofthe7th centuryexposedamajordiscrepancybetweenthecommon scholarlyperceptionoftheAssyrianinvolvementintheSouthernLevantand theactualevidence “ontheground”

MylaterworkontheperiodofNeo-Babylonianruleintheregion,culminatinginthebook JudahintheNeo-BabylonianPeriod:TheArchaeologyof Desolation (Faust2012b)didnotdirectlydiscusstheperiodofAssyrianrule, butitforcedmetostudythiserawhichservedasbackgroundtothechanges createdbytheBabylonianconquests.ThemoreIstudiedthe7th centurydata intheareasannexedbytheNeo-Assyrianempire,themoreitappearedthat thedifferencebetweenthepoliciesofthetwoempireswasnotasgreatasthey wereoftendescribed.Comparingthe6th andthe7th centuriesBCE(i.e.the periodsofNeo-BabylonianandNeo-Assyriancontrol)forcedmetoseethat therealityinthe7th century,whentheregionwassupposedtohaveprospered, wasmorecomplex,andwhiletheclients flourishedtheAssyrianprovinces weredevastated.Thisresultedwithafewmorearticles(suchasFaust2011a; Faust2015a,andmore).

Bythattimeitwascleartomethattheeconomicanddemographicreality underNeo-Assyrianrule,atleastthewayIunderstoodit,wasverydifferent frommostcommoninterpretations(notall).Isummarisedsomeofthedatain afewlargearticles(suchasFaust2018c;2018d),and(withShawnAster) organisedaninternationalworkshoponthistopicwhichresultedwithan editedvolume.Irealised,however,thatamuchmoredetailedandsystematic treatmentwasneeded atreatmentthatwouldnotonlyexpandthediscussion

oftheevidencefromtheSouthernLevant,butwouldalsoputitwithinthe contextoftheNeo-Assyrianempireatlargeandevenwithinabroadstudyof ancientempires.

Inthesummerof2016IwasgrantedaSummerVisitingFellowshipat St.John’sCollegeattheUniversityofOxfordwiththeexplicitaimofbeginningabookprojectonthistopic.WhilestayinginOxfordIcarriedoutsome ofthebasicresearchforthisstudy,outlineditsstructure,andwrotethebook proposalwhichIsubmittedtoOxfordUniversityPress.

Whileworkingonthebookeversince,mostoftheresearchandwritingwas carriedoutduringfoursubsequentacademicbreakswhichIspentabroad.The firstofthesewasintheOrientalInstitute(OI)intheUniversityofChicago(in February2018),andtheotherthreewereinOxford.

IamgratefultoSt.John’sCollegeforgrantingmetheFellowshipthat initiatedtheresearch,toProf.DavidSchloenforinvitingmetothe UniversityofChicago,totheOIforprovidingmewithlibraryservicesand officespace,toOxfordlibraries(especiallytheSacklerandtheBodleian),and toBar-Ilan’slibraries.

Thanksarealsoduetothemanycolleaguesandfriendswhoovertheyears discussedmanyoftheissuesaddressedinthisbookwithme,suppliedadvice andreferences,andhelpedinotherways,includingDavidSchloen(University ofChicago),DanielMaster(WheatonCollege),ShawnZeligAster,Joshua Schwartz,ZeevSafrai,EhudWeiss,EyalBaruch(Bar-IlanUniversity),Peter Machinist,JasonUr,(thelate)LarryStager(HarvardUniversity),Shlomo Bunimovitz,ZviLederman(Tel-AvivUniversity),JanJoosten(Oxford University),PeterDubovský(PontificalBibleInstitute),ChaimBen-David, HayahKatz(KinneretCollege),BaruchBrandl(IsraelAntiquitiesAuthority), GunnarLehmann(Ben-GurionUniveristy),SandraJacobs(King’sCollege London),andPeterZilberg(theHebrewUniversityofJerusalem).Special thanksareduetomyformerstudentsGiladItachandYairSapirwhose workonrelatedtopicsarequotedinthisbook.

Iwouldalsoliketothanktheparticipantsoftheworkshop “TheAssyrian PeriodintheSouthernLevant”,whichtookplaceinYadBen-ZviInstitutein JerusaleminNovember11-122005,fortheirinsightfulpapersandcomments duringthemeeting.

Thebookcontainsavastamountofinformation,andnotallofitis published(or,intheleast,wasnotpublishedwhenitwassuppliedtome), andIamverythankfultomanycolleagueswhosuppliedmewiththis information,includingHagitTorge(IAA),GiladItach(BIUandIAA),Amit Shadman(IAA),RonTueg(IAA),ZviLederman(TAU),JimmyHardin

(MSU),ChaimBen-David(KinneretCollege),andHayahKatz(Kinneret College).

Permissiontouse figureswasgrantedbytheIsraelExplorationSociety,The IsraelAntiquitiesAuthority,theIsraelGeologicalSurvey,RonnyReich(Haifa University),andZe’evHerzog(TelAvivUniveristy).

TamarRoth-FensterandAsnatLauferhelpedinthepreparationofthe bibliographyandofsomeofthe figures.TidharKaroproducedtwoofthe maps,andthreeotherswereproducedbyJanetJacksonandCharlesWilson. SupportwasalsoprovidedbytheIngeborgRennertCenter.

SpecialthanksareduetoDanielaDueckandespeciallyShawnZeligAster (bothfromBar-IlanUniversity)whoreadpartsofthebook.Shawn’shelpwas extremelyvaluableinmanyrespects,andIwishtothankhimforhishelpand forhisextremegenerositywithhistime.

Iamgratefulforallthosementionedabove,andapologisetoallthosewhose contributionandhelpIfailedtomention.Naturally,whileallthesegreatly helpedinimprovingthebook,theresponsibilityforalltheerrorsandomissionsthatremainisminealone.

FinallyIwouldliketothankmyfamilyandespeciallymywifeIrisforthe supportandunderstanding,andforallowingmetodevotesomuchtimeto thisbook.

Introduction

DevelopingfromasmallcoreareainwhatistodaynorthernIraq,the Neo-Assyrianempire(tenth–seventhcenturies )wasthe firstlargeempire oftheancientworld,andsomehaveevendefineditasthe firstworldempire (Bagg2013;Radner2015:1).Itshistoricalimportancecannotbeoverestimated,asitinitiatedwhatissometimescalledthe ‘AgeofEmpires’ (Altaweel andSquitieri2018),i.e.asequenceofempiresthatruledtheNearEast(and beyond)intightsuccessionuntilthetwentiethcentury.ThedetaileddescriptionsoftheAssyrianempireanditsactionsintheHebrewBible,followedby thespectaculardiscoveriesofimperialpalaces,royalinscriptions,andother impressiveremains,hadcapturedthepublicimagination,andresultedina largenumberofstudiesthatweredevotedtothisempire,itshistory,and structure.

TheSouthernLevant thelandsoftheBible formedthesouthwestern marginsoftheempire,andboththeempireandtheregionhavereceivedafair amountofresearch.Onlyafew,however,haveuntilrecentlyexaminedthe empirewithinalarge-scalecomparative,oranthropologicallyorientedperspective,perhapsasaresultofthestronghistoricalbiasoftheregion’ s archaeology(e.g.Moorey1991;Bunimovitz1995;BunimovitzandFaust 2010;Flannery1998;Davis2004).Whilethisisgraduallychanging(seee.g. Bagg2011;MacGinnisetal.2016;TysonandRimmerHerrman2018;Altaweel andSquitieri2018),thepotentialoftheempiretocontributetothestudyof empiresandimperialismisgreatlyunderutilized.

TheSouthernLevant,moreover,hasanumberofadvantagesforthestudy ofbothAssyrianimperialism,andevenempiresatlarge.(i)Theavailability ofaverylargearchaeologicaldataset probablythelargestintheworld: whiletheareaisquitesmallingeographicalterms,hundredsofplanned excavationshavebeencarriedoutinitovertheyears,alongwiththousands ofsalvageexcavationsanddetailedsurveys.Hundredsoftheseexcavations revealedremainsfromtheperiodsdiscussedinthisbook,providingscholars withanunparalleledarchaeologicaldataset.Thiswealthisaugmentedby (ii)arelativelylargenumberofancienttextsthatrelatetotheperiodunder discussion,unearthedbothintheregionitselfandinMesopotamia.These

include(cuneiform)royalinscriptionsandadministrativedocumentsand correspondencerelatingtotheregion(andeventhesethatrelatetothe Assyrianempireatlargecanteachusagreatdealaboutitsoperation),as wellasalphabeticostracafromthearea.Moreover,(iii)thebiblicaltextsalso providedetailedinformationonthisperiod.Whilethedifferentsourcesall havebiases,takentogether,thericharchaeologicaldata,theAssyrian(and local)documentaryinformation,andthebiblicaltextualdataprovideexceptionallydetailedevidenceontheperiodinquestion,enablingustostudythe natureofAssyrianruleintheareaingreatdetail,andallowingittoserveas anexcellenttestcaseinwhichtostudyboththeempireanditssubjects. Finally(iv),thestudiedregion,despiteitslimitedsize,isquitevaried,and includesbothprovincesandclientkingdoms,aswellasdiverseecological niches,fromhighlandsthroughfertilevalleystodeserts.Thus,theunique combinationofrichdataondifferentpoliticalunitsandecologicalzones enablesadetailedcomparativeresearchthatcancompareboththedifferent units(includingprovincesversusclients)andregionstoeachother,aswell astherealitybeforeandaftertheincorporationoftheareawithinthe Assyrianempire.Notably,theuniquelyrichdataatourdisposable,including textsthatwerewrittenbytheconquered,illuminatesnotonlytheimperial actionsandtheiroutcomes,butalsothelocalresponsestoimperialactivity, bothintheprovincesandintheclientkingdoms.

Usingabottom-upapproach,thisbookutilizestheunparalleledinformationavailablefromtheregiontoreconstructitsdemographyandeconomy beforetheAssyriancampaigns,andafterthem.Comparingthesetwosnapshotsforcesustoappreciatethetransformationstheimperialtakeover broughtinitswake,andtorethinksomeacceptedwisdomonthenatureof Assyriancontrol.ThisisfollowedwithananalysisoftheactualAssyrian activitiesintheregion,andtherealityinthesouthwestisthencomparedto thatinotherregions.Thiscomparison,onceagain,forcesustoaccountfor thedifferencesencountered,resultinginabetterappreciationoffactors in fluencingimperialexpansion,theconsiderationsleadingtoannexation, andtheimperialmethodsofcontrol,challengingsomeoldconventions aboutthedevelopmentoftheAssyrianempireanditsrule.Thisleadsto anexaminationoftheAssyrianempireincomparisontootherancientNear Easternempires,analysingthewayancientempirescontrolledremoteprovinces.Reviewingthedevelopmentofancientempiresexposesnotonlythe natureofAssyriandomination,butalsooneofthemajorchangesinthe natureofimperialcontrolinantiquity,andtowhatwecalltheAchaemenid revolution.

Thebook’sstructureisoutlinedingreaterdetailsin ‘TheStructureofthe Book’ below,but firstweshouldpresentbackgroundinformationofthestudy ofempiresatlarge,ontheAssyrianempireanditsruleinthesouthwest,and onthesourcesofinformationforthisstudy.

Background

EmpiresandtheStudyofEmpires

Empireshavereceivedagreatdealofstudy,¹andthisbriefintroductionisonly intendedtopresentsomeofthebasicconcepts.

Theword ‘empire’ isderivedfromtheLatinterm imperium,originally meaning ‘tocommand,order,power,rule,orsovereignty’.Theterm,initially usedtodescribe ‘thepowersofruleandconquestgrantedtoaRomanconsul’ , developedtodenotetherelevantterritory,evenifthenatureofthecontrolwas notalwaysclearlydefined(ClineandGraham2011:3–4;seealsoHowe 2002:13).

Theliteratureonempiresisvast,andalthoughdefinitionsvaryslightlyin emphasis,²mosthavesimilarvariables.Sinopoli(1994:159),forexample, notedthat ‘Empiresaregeographicallyandpoliticallyexpansivepolities, composedofadiversityoflocalizedcommunitiesandethnicgroups.’ Stark andChance(2012:194)offeredasimilardefinition,emphasizingthelargesize ofempires,andstatingthatempiresare ‘expansioniststatesthatincorporate diversesocietieswellbeyondimmediateneighbors’ (seealsoSchreiber1992:3).

Altaweel(2008:16)alsonotesthatoneofthecharacteristicsofempiresis controloverforeignregionsandpopulationthatwerenotoriginallypartofit (alsoClineandGraham2011:3–7).Howe(2002:15)suggestedthat ‘Empires, then,mustbydefinitionbebig,andtheymustbecompositeentities,formedout ofpreviouslyseparateunits.Diversity ethnic,national,cultural,often religious istheiressence.’ Howe,however,addedthat ‘inmanyobservers’ understanding,thatcannotbeadiversityofequals’.Indeed,manyhavestressed thatthenatureoftheinteractionispartofthedefinitionofanempire(below).

Sinopoli(1994:160)summarizedthatmanyde finitions ‘shareincommon aviewofempireasaterritoriallyexpansiveandincorporativekindofstate,

¹E.g.Doyle1986;Sinopoli1994;ClineandGraham2011;Alcocketal.2001;Parsons2010;Howe 2002;MorrisandScheidel2009;Smith2012.

²E.g.Sinopoli1994:159–60;Doyle1986:12;Liverani2017:1;StarkandChance2012:194;Cline andGraham2011:3–7;Howe2002:13–15;AltaweelandSquitieri2018:4,andmore.

involvingrelationshipsinwhichonestateexercisescontroloverother socio-politicalentities(e.g.states,chiefdoms,non-stratifiedsocieties)’,and Howe(2002:30)concludedthat ‘Anempireisalarge,composite,multi-ethnic ormultinationalpoliticalunit,usuallycreatedbyconquest,anddividedbetween adominantcentreandsubordinate,sometimesfardistant,peripheries.’

Duringtheirexpansion,however,theoriginalpolitiesdidnotonlybecome larger,butwerealsotransformedintosomethingdifferent.Theresultwasthe emergenceofanewtypeofsocialorganization,witha ‘newculturallogicanda newconfigurationofpower’ (Woolf1997:347).Itisnotonlythatthecentre that,byexpandingtosurroundingareas,changesthestructureofitsweaker neighbours,butalsoanewsocialandpoliticalentityisformedbytheprocess.

The ‘processofcreatingandmaintainingempires’ isoftencalled imperialism (Sinopoli1994:160),andthetermisalsousedtodescribethe ‘actionsand attitudeswhichcreateorupholdsuchbigpoliticalunits’ (Howe2002:30). Indeed,asecondmeaningstressesthenatureoftherelationshipbetweenthe centreandtheconqueredareas,andHowe(2002:13)notedthatthetermis usedtodenoteanyformofinteractionbetweenamoredominantgroupor polityandweakerones,embracingallformsofcontrol(Howe2002:30).

Empiresandimperialismaretherefore,bydefinition,abouthierarchyand inequality.Doyle(1986:12),forexample,referredtoasystemofinteraction betweentwopolities,inwhichthedominant(‘metropole’),exercisessome controloverboththeinternalandexternalpoliciesoftheweaker,addingthat inordertounderstandtheserelationswemustfathomthecausesforthe weaknessoftheinferiorpolity,justaswemustappreciatethereasonsforthe strengthandthemotivesofthemorepowerfulone.Thenatureoftheimperial relationsarein fluencedbyanumberoffactors,andDoyle(1986:46) notedthat:

fourinteractingsourcesaccountfortheimperialrelationship:themetropolitanregime,itscapacitiesandinterests;theperipheralpoliticalsociety,its interestsandweakness;thetransnationalsystemanditsneeds;andthe internationalcontextandtheincentivesitcreates.

Inordertounderstandthenatureofimperialdynamicsandtheforcesthat shapethem,manyscholarsadoptMann’s(1986:2)viewofthesourcesof socialpower,i.e.ideology,economics,themilitary,andpolitics(orIEMP)(e.g. ClineandGraham2011:5;Bagg2013:121),withdifferentscholarsstressing theimportanceofdifferenttypesofpowerandcontrolaccordingtocircumstances.Somevieweconomicstrategyasthemostimportantone(Berdanand

Smith1996),whileothersstressespoliticalcontrol(Altaweel2008:16–17),or theideologicalcomponent,i.e.thatproperempiresuseideology(ofteninthe formofreligion)tojustifytheirexpansionandconquest.Sinopoli(1994:167), forexample,notedthatideologymotivatesaction,especiallyimperialexpansion,andis ‘providinglegitimationforandexplanationsofextantandemerginginequalities’.Indeed,attimesitistheappropriateideologythatenables empirestoexpand(Liverani2017:8),andHowe(2002:83)notedthat ‘The rulersofeverymajorempireatleastsincetheRomans ...offeredarguments andjustificationsforwhattheydid.’ This,ofcourse,appliestotheAssyrian empire(e.g.Howe2002:36;Grayson1995:966;Liverani2017).

EmpiresusetheirpowerindifferentwaysandBerdanandSmith(1996),for example,articulatedanumberofstrategiesthattheAztecempireusedto furtheritsinterests,includingpoliticalstrategy,economicstrategy,frontier strategy,andelitestrategy.Thesewereusedtomaintaintheimperialcontrol (seealsoStarkandChance2012:197–9;seealsoChapter10).

Whilecontrolofthecentreovertheperipheryisanessentialpartofbeing anempire,³thenatureofimperialcontrol,orintegration,variesgreatly,and thereisacontinuumbetween ‘weaklyintegratedtomorehighlycentralized polities’ (Sinopoli1994:160).Indeed,empiresalwaysemploysomecombinationofboth,directandindirectcontrol(Howe2002:15;alsoAltaweel2008: 16).Variousscholarsusedifferenttermstorefertothedegreeofintegrationof theperipheralareasintotheempire,orthelevelofcentralizationexercised overremoteterritories.Thus,manyrefertoamoredirectcontrolasterritorial, whereasanindirectcontrolisseenashegemonic(e.g.Luttwak1976),and othersuse ‘formal’ versus ‘informalempire’ inwhatforourpurposescanbe usedinasomewhatsimilarway(Doyle1986).Nomatterwhich ‘binary’ system(asnoted,thepolesarepartofacontinuum)weprefertouse,itis importanttostressthatdifferentmethodsofcontroloftenoperatesimultaneouslyindifferentpartsoftheempire,andthatimperialpoliciesvariedacross timeandspace,inaccordancewiththedifferent,andchanging,circumstances (e.g.Sinopoli1994:163–4;Howe2002,andseeChapters10–11).Inmany imperialcontexts,theareasthatwereruleddirectlybytheempirearereferred toasprovinces,whereastheterritoriesthatwereruledindirectlyareviewedas clientorvassalkingdoms.

Inmostcases,empiresinitiallypreferredindirectcontrol,sincetheconquestsrequiredtoobtaindirectcontrolarecostly,andnecessitatespending

³Sinopoli1994:161notedtheinfluenceoftheworldsystemperspectiveonthestudyofempires (andseealsoChapter5).

resourcesandlives,oftenleadingtomajordestructionsandupheavalsthat minimizetheproductioncapabilitiesintheconqueredterritories.Theconquest,moreover,requiresinvestinginadministrationandmilitaryinorderto ruletheseterritories.Diplomacy,evengun-boatdiplomacy i.e.thethreatof power isthereforeusuallypreferred(Sinopoli1994:162–3,167;Luttwak 1976).Conquestordestructionmightresultfromtheneedtodecimatea powerfulenemy(Sinopoli1994:162–3),butinmostcasesthetransitionto directrulewasaresultofcontinuousrevolts.

TheStudyArea

Inmodernterms,thesouthwesternperipheryoftheAssyrianempireincorporatesthesoutherntipofLebanon,aswellasmuchofIsrael,thePalestinian authority,andthewesternpartofJordan.Theareaisnotlarge,andcovers some25,000squarekm somethinglikeMarylandintheUS.Therearemany designationstothisareainthescholarlyliterature,forexample,theLandof Israel,Palestine,theHolyLand,thelandsoftheBible,ortheSouthernLevant. IntheIronAgetheregionincorporatedthekingdomsofIsrael,Judah, Ammon,Moab,Edom,andthePhilistinecitystates,aswellaspartsofthe kingdomsofTyreandAramDamascus.Largepartsoftheregionwereturned intoAssyrianprovincesinthelaterpartoftheeighthcentury

Geographically,thissmallareaincorporatesdiversetopographicaland ecologicalniches(Figure1.1).TheMediterraneancoastalplainwasofgreat economicsignificance,asitsportsandanchoragessuppliedtheareawith accesstothelucrativemaritimetrade,anditsinnerpartscontrolledthe internationalhighway,connectingEgyptandSyria–Mesopotamia.Thecentral highlandridge,composedofthehillsofJudea,Samaria,andfarthernorthalso theGalilee,althoughlessaccessible,couldproducesurplusesofwineandolive oil.ThefertilenorthernvalleysofmodernIsraelcutthishighlandridge,and providedeasyeast–westaccess,thushostinganimportantsystemofroads, includingafewbranchesoftheinternationalhighway.Thesevalleysalso servedasthegrainbasketoftheregion.Furthereast,theregionincludedthe JordanValley veryfertileinthenorth,whereitwaspartoftheso-called northernvalleys,andaridinthesouth andtheTransjordanianhighlands. Theimportant ‘King’sHighway’,connectingArabiaandSyria,passedthrough thelatter.Finally,theregionincorporatedthesemi-aridandaridNegevinthe south,andtheroutesconnectingthe ‘King’sHighway’ andtheMediterranean portsofGazaandAshkelon.

Figure1.1 MapoftheSouthernLevant,withthemainthegeographicalsub-units

Source:AfterA.Curtis(2009)OxfordBibleAtlas,4thedn,courtesyofOxfordUniversityPress; additionsmadebyCharlesWilson).

Sinceprecipitationdeclinesasonemovessouthward,andcombinedwiththe existenceoflargefertilevalleysinthenorth,thelatterhadamuchgreater agriculturalpotential.Thefactthatthemajorroadscrossedthenorth,aswell asthelatter’sproximitytoTyre,madeitseconomicpotentialbyfargreater

thanthatofthesouthernparts,andindeed,throughouthistorythenorthwas politicallyandeconomicallymoreimportantthanthesouth.

TheAssyrianEmpire

TheNeo-AssyrianEmpire:BriefSummaryofIts DevelopmentandBasicPeriodization

ThecoreoftheAssyrianempireinnorthernMesopotamiaisatriangle betweenAssurinthesouth,Nineveh(Mosul)inthenorth,andArbilu (Erbil)intheeast(Radner2014:102;Hunt2015:20).Thiswasafertilearea, withgoodclimaticconditions,anditwaseasilyaccessibleviarivers,leading tohigheconomicpotentialforbothagriculturalproductionandtrade (Figure1.2).

Inthefourteenthcentury Assyriagrewfromacity-state,dominatedby Mittani,toanindependentterritorialstate.Initiallyencompassingthecitiesof Nineveh,Kalhu,Kilizu,andArbilu,itlateralsoincorporatedtheremainsof theMittani,extendingtotheEuphrates.Thisera(1400–1200 )issometimesregardedastheperiodof ‘creationandoriginalexpansion’ ofthe Assyrianstate.Subsequently,Assyriaenteredaperiodofrecessionthatlasted intothetenthorevenearlyninthcentury (e.g.Postgate1992:257;Radner 2014:102).

There-establishmentoftheAssyrianstate theNeo-Assyriankingdom wasalongprocessinwhichtheAssyriankingsgraduallyregainedtheirformer territory.Aftertheexpansionofthelatetenthandearlyninthcenturiescamea phaseofimperialconsolidation.The firststepinconsolidatingitscontrolover conqueredterritorieswastodismantlethelocaldynastiesinthenewly acquiredregions,andreplacethemwithgovernorsfromthecorearea,who wereappointedbythekingandwereloyaltohim.Theempirealsodeveloped roads,whichenabledspeedyconnectionsbetweenthekingandthegovernors ofthemoreremoteprovinces,andthekingbuilt ‘royalcities’ withpalaces throughouttheempire,whichheusedfromtimetotime(Radner2014:105). Assyria’snominalextentwasstillrelativelylimited,similartothatofthe thirteenth–twelfthcenturies ,i.e.limitedbytheEuphratesinthewest.Its role,however,changedconsiderablyanditexertedmuchinfluenceoverits neighbours,manyofwhichbecameclients(Radner2014:103).Radnerdefined thechangesthattookplaceinthecourseoftheninthcenturyasatransformationfromaregionalpowertoanhegemonicempire(seealsoYamada2000).

Figure1.2 MapoftheAssyrianempire,noting ‘theAssyriantriangle ’,andhighlightingtheextentoftheempireinthemiddleofthe eighthcentury ,andtheareasconqueredinthesecondhalfofthiscentury(mostlybyTiglath-pileserIII)

Source:PreparedbyYairSapirandTamarRoth-Fenster;courtesyoftheTel ‘Etonexpedition.

Thelatterpartoftheninthand firsthalfoftheeighthcenturiesdidnotseea significantexpansion,andAssyriawas(amongotherthings)confrontedby largepowers(e.g.Urartu),whichsometimesevendefeateditandthreatened theloyaltyofitsclients(Radner2014:103–4;foradifferentviewofAdadnīrārī III’srule,seeSiddal2013).TheunrestfollowingthedefeatofAshurnīrārī VbyUrartuledtoTiglath-pileserIII(747 )seizingthethrone,and soonafterheembarkedoncampaignsinallfronts,greatlyincreasingthe empire’sholdings.AsHunt(2015:29)noted,inonlytwenty-twoyears, ‘the Neo-Assyrianempiredoubleditsterritorialholdingsandsphereofinfluence ’ .

NotonlydidTiglath-pileserIIIsignificantlyexpandedtheempire,but healsomadesomesubstantialadministrativechanges,aimingtoweakenthe powerofthegovernorsandtostrengthenthatoftheking.Thus,inadditionto creatingnewprovincesintheconqueredterritories,hereorganizedtheolder provinces,replacingthemwithsmallerones,andhenceincreasingtheir numberfromtwelvetotwenty-five(e.g.Radner2014:108–9).Similarly,he dividedsomeofthemainmilitaryandadministrativepositions,andtwo individualssharedtheresponsibility,whichhadbeenheretoforeheldbyone. Theinstitutionofeunuchsinsomepositionsalsosupportedtheseefforts,asit decreasedthechancesofofficialsestablishingpowerandpassingittotheir sons(VandeMieroop2007:248;seealsoPerčírková1987:173).

Thisperiodisregardedasoneofexpansion(despitethecrisisatthetimeof ShalmaneserV),lastinguntilthedeathofSargonIIin705 .Mostofthe clientkingdoms,aswellasadditionalareas,wereconqueredandturnedinto provinces,andthiswasfollowedbyanotherphaseofconsolidation(beginning afterSennacheribre-establishedimperialrule).Intheperiodcoveringmainly theseventhcentury,theempirewasattheheightofitspower,andasParker (2012:867)noted,it ‘claimeddominionoveralmosttheentireMiddleEast, fromthePersianGulftotheTaurusmountainsandfromtheZagrosmountainstotheMediterraneanSea.Forashortperiodduringthe7thcentury , theAssyriansevencapturedEgypt’ (seealsoVandeMieroop2007:247).Most oftheconqueredareaswereturnedintoprovinces,andwereregardedaspart ofAssyria.Theterritorialconsolidationwasaccompaniedbypoliticalchanges. Sennacherib’sgreatinvestmentinNineveh,andthemassiveresettlementof deporteesinthisarea(Radner2014:109;cf.Oded1979:28,andseemorein thesection ‘TheAssyrianDeportationPolicy:CausesandConsequences’ below)ledtoadditionalchanges,asitshiftedthedistributionofpower betweentheroyalfamilyandcourtontheonehand,andtheofficialsinthe provincesontheother.ThisstrategywascontinuedbySennacherib’ ssuccessors.Essarhadontwiceorderedmassexecutionsofstateofficials,andthefact thatduringthereignofAssurbanipal(andonwards)courtiersandpalace

officialsreceiveddistinctionsandprivileges(ratherthanstateofficials)is anotherindicationofthecontinueddecreaseinthepowerofthoseoutside thepalace(e.g.Radner2014:109,111).Thekingsspentmostoftheirtimein thepalacewiththeircourtiers,ratherthaninthearmy,orevenmakingpublic appearances(Radner2014:109).Duringthesecondhalfoftheseventh century,theAssyrianempireweakened,asaresultofvariousprocessesand decisions,andwaseventuallyoverthrownbytheBabylonians(e.g.Liverani 2001;Kahn2015).

Thislongperiodoftime between1400and650/600 hasbeen subdivideddifferentlybyvariousscholars,suchasPostgate(1992),Bedford (2009: 39),andLiverani(2014:481,485).Combiningtheseworks,wewill usethefollowing,simplisticsub-division,whichshouldbesufficientforour purposes:

1.theperiodofinitialcreation(1400–1200 );

2.aperiodofrecession(1200–934 ).Thesetwophasesareusually regardedasprecedingthetimeoftheNeo-Assyrianempire.Theywere followedby:

3.theperiodofinitialAssyrianexpansion,regainingtheformerboundariesofAshur,andevenextendingbeyondthat(934–824 );

4.aperiodofcrisis(823–745 );

5.aperiodofrapidexpansion(744–705 );

6.thepeakoftheAssyrianempire,sometimesreferredtoastheeraof ‘Assyrianpeace’ (althoughthetermprobablycouldnotbeappliedtothe firstyearsofSennacherib)(705–630 );

7.thedeclineoftheAssyrianempire(630–609 ;regardlessoftheexact dating,whichisdebated,e.g.Malamat1973:270–2;Eph’al1979:281–2; Kahn2015).

Phases1–2,aswellas7,arenotofconcernhere,andwillberarelymentioned. TheearlierphasesofAssyrianexpansionandrule(phases3–4)willbe addressedinvariouspartsofthebook,mainlyforcomparativepurposes,but thebookmainlyfocusesonphases5and6.

TheAssyrianEmpire:FormsofControl

Atitspeak,theempirewasanenormouspolity,controllingareasfrom modernIrantotheMediterranean,andfromtheZagrostothePersianGulf, theArabiandesert,andEgypt.