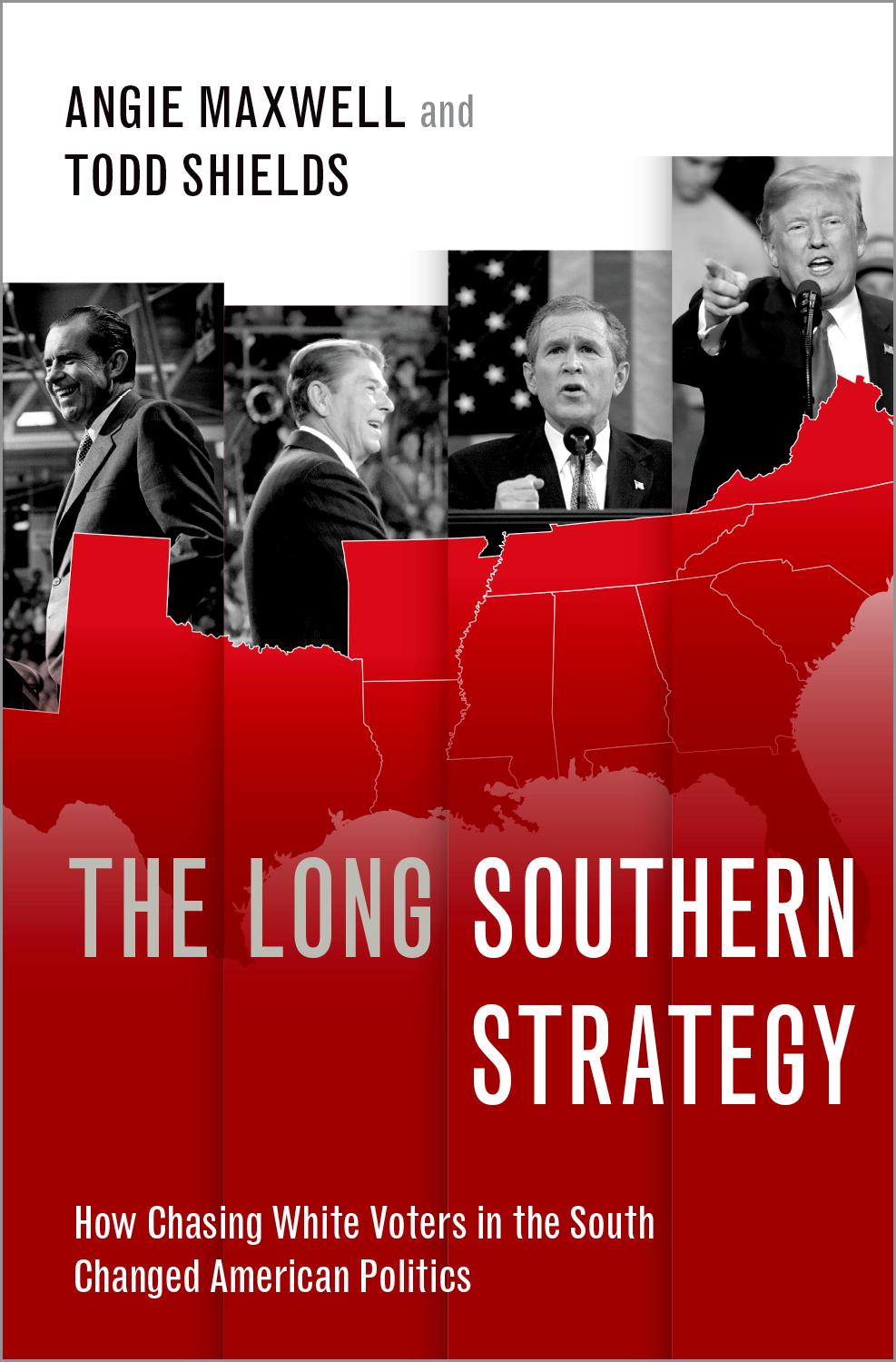

The Long Southern Strategy

How Chasing White Voters in the South Changed American Politics

ANGIE MAXWELL

TODD SHIELDS

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress ISBN 978–0–19–026596–0

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For Sidney, who is always there when it rains, and for Elizabeth, my sunshine.

A. M.

In memory of Diane D. Blair. Her success in teaching, research, service, and activism continues to motivate and inspire. I couldn’t have asked for a better role model and mentor.

T. S.

Figures and Tables

Figures

I.1 Percent Vote for Democratic Candidate in Presidential General Election, Among Whites Who Live in the South, 1964–2012

25

I.2 Percent Party Identification as Democrat, Among Whites Who Live in the South, 1964–2016 26

I.3A Mean Party Identification, Among White Men Who Live in the South, 1964–2016

29

I.3B Mean Party Identification, Among White Women Who Live in the South, 1964–2016 30

1.1A Mean Feeling Thermometer Evaluation of Whites, Among Whites, 2010–2012 50

1.1B Mean Racial Stereotype Scores Toward Whites, Among Whites, 2012 51

1.2A Percent Responses to: “How Strongly Do You Think of Yourself as White?” Among Non-southern Whites, 2012 52

1.2B Percent Responses to: “How Strongly Do You Think of Yourself as White?” Among Southern Whites, 2012 52

1.3 Mean Feeling Thermometer Evaluations of Whites, African Americans, and Latinos, Among Whites, 2010–2012

57

1.4A Mean Ethnocentrism Scores (Feeling Thermometer Measure), Among Whites, 2010–2012 58

1.4B Mean Ethnocentrism Scores (Racial Stereotype Measure), Among Whites, 2010–2012 59

Figures and Tables

1.5 Percent Attitudes Toward “Tougher Immigration Laws Like in Arizona,” Among Whites, 2010–2012 64

1.6 Mean Feeling Thermometer Evaluation of Whites and Percent “Strongly” or “Very Strongly” Claiming White Identity, Among Whites, 2010–2016 66

1.7 Mean Feeling Thermometer Evaluations of Black Lives Matter and Police, Among Whites, 2016 67

1.8 Percent Responses to: “A Wall Should Be Built Along the Entire Border with Mexico,” Among Whites, 2016 68

2.1 Percent Reporting That the Future Will Be “Somewhat” or “Much Worse,” for the Following, Among Whites, 2010 81

2.2 Percent Reporting “Some” or “A Lot” of Competition with African Americans and Latinos, Among Whites, 2012 85

2.3 Percent Reporting Experience with the Following Types of Reverse Racial Discrimination, Among Whites, 2012 89

2.4 Percent Prospective Views of Respondents’ Personal Economic Situation, Among Whites, 2010–2016 90

2.5 Percent Reporting “Some” or “A Lot” of Competition with Latinos and African Americans, Among Whites, 2010–2016 91

3.1 Percent Responses to: “Is There Too Much, the Right Amount, or Too Little Attention Paid to Race These Days?” Among Whites, 2010–2012 103

3.2A Mean Racial Resentment (Toward African Americans) Scores, Among Whites, 2010–2012 107

3.2B Mean Racial Resentment (Toward Latinos) Scores, Among Whites, 2012 107

3.3A Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Racial Resentment (Toward African Americans) Scale, Among Whites, 2010–2012 109

3.3B Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Racial Resentment (Toward Latinos) Scale, Among Whites, 2012 109

3.4A Percent of Racial Resentment Responses (Toward African Americans) by Individual Questions, Among Whites, 2010 112

3.4B Percent of Racial Resentment Responses (Toward African Americans) by Individual Questions, Among Whites, 2012 112

3.4C Percent of Racial Resentment Responses (Toward Latinos) by Individual Questions, Among Whites, 2012 113

3.5 Percent Attitudes Toward “Employers and Colleges Making an Extra Effort to Find and Recruit Qualified Minorities,” Among Whites, 2010–2012 115

3.6 Percent Responses to: “Do You Think African Americans Have More Opportunity, About the Same, or Less Opportunity Than Whites?” Among Whites, 2010 116

3.7 Percent Reporting “Too Much” Attention Is Paid to Race and Who “Oppose” or “Strongly Oppose” Affirmative Action, Among Whites, 2010–2016 117

3.8A Mean Racial Resentment (Toward African Americans) Scores, Among Whites, 2010–2016 118

3.8B Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Racial Resentment (Toward African Americans) Scale, Among Whites, 2010–2016 119

3.8C Percent of Racial Resentment Responses (Toward African Americans) by Individual Questions, Among Whites, 2016 120

4.1A Mean Modern Sexism Scores, Among Whites, 2012 143

4.1B Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Modern Sexism Scale, Among Whites, 2012 143

4.2 Percent of Modern Sexist Responses by Individual Questions, Among Whites, 2012 144

4.3A Mean Modern Sexism Scores, Among White Women, 2012 145

4.3B Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Modern Sexism Scale, Among White Women, 2012 146

4.4 Percent of Modern Sexist Responses by Individual Questions, Among White Women, 2012 147

4.5A Mean Modern Sexism Scores, Among White Women, 2012–2016 153

4.5B Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Modern Sexism Scale, Among White Women, 2012–2016 154

4.6 Percent of Modern Sexist Responses by Individual Questions, Among White Women, 2016 155

4.7 Percent Reporting That Getting Married and Having Children Is “Very Important” or “Important” to Them, Among White Women, 2016 155

5.1 Percent Reporting Experience with the Following Types of Reverse Racial Discrimination, Among Whites, by Gender, 2012 166

5.2 Percent Attitudes Toward “Tougher Immigration Laws Like in Arizona,” Among Whites, 2010–2012 170

5.3A Mean Modern Sexism Scores, Among White Men, 2012 173

5.3B Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Modern Sexism Scale, Among White Men, 2012 173

5.4 Percent of Modern Sexist Responses by Individual Questions, Among White Men, 2012 174

5.5 Percent Agreement Regarding Gender Roles, Among White Men and Women Who Identify as Southern, 1994 179

5.6A Mean Modern Sexism Scores, Among White Men, 2012–2016 181

5.6B Percent Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Modern Sexism Scale, Among White Men, 2012–2016 182

5.7 Percent of Modern Sexist Responses by Individual Questions, Among White Men, 2016 183

5.8A Percent Who “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” with the Following Types of Gun Control, Among White Men, 2016 184

5.8B Percent Who “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” with the Following Types of Gun Control, Among White Women, 2016 184

5.9 Percent Reporting Experience with the Following Types of Reverse Racial Discrimination, Among Whites, by Gender, 2016 185

5.10 Net Change in Percent Reporting Experiences of Reverse Racial Discrimination, Among Whites, by Gender, 2012–2016 186

6.1A Percent Reporting Abortion Should “Rarely” or “Never” Be Legal, Among Whites, by Gender, 2012 196

6.1B Percent Who “Oppose” or “Strongly Oppose” Gay Marriage, Among Whites, by Gender, 2012 197

6.2 Percent Gender Gaps (Women Minus Men) in Opposition to Abortion and Gay Marriage, Among Whites, 2012 197

6.3 Percent Who Do Not Expect to See a Female President in Their Lifetime, Among Whites, by Gender, 2012 205

6.4 Predicted Probability of Believing in a Future Female President, Among Whites, Across Modern Sexism Scale, 2012 207

6.5A Percent Vote for Presidential Primary Candidates, Among Whites, 2016 209

6.5B Percent Gender Gap (Women Minus Men) in Presidential Primary Supporters by Candidate, Among Whites, 2016 210

6.6A Percent Vote for General Election Candidates, Among Whites, 2016 211

6.6B Percent Vote for General Election Presidential Candidates, Among Whites, by Gender, 2016 212

6.6C Percent Gender Gap (Women Minus Men) in General Election Voters by Candidate, Among Whites, 2016 213

6.6D Percent Vote for Trump and Clinton, Among Whites, with Mean Modern Sexism Scores for Those Voters, 2016 214

6.7 Mean Modern Sexism Score by Candidate Gender Gap (Percent Vote for Male Candidates Minus Percent Vote for Female Candidates), Among Whites, by Gender, 2016 215

6.8 Percent Vote for General Election Candidates, Among White Women, by Marital Status with Mean Modern Sexism Scores, 2016 216

7.1 Mean Racial Resentment, Ethnocentrism, and Modern Sexism Scores, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), 2012 251

7.2A Percent Responses to: “How Strongly Do You Think of Yourself as a Christian Fundamentalist?” Among Non-southern Whites, 2016 253

7.2B Percent Responses to: “How Strongly Do You Think of Yourself as a Christian Fundamentalist?” Among Southern Whites, 2016 253

7.3 Percent Responses to: “How Important Is It to You Personally to Live a Religious Life?” Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Selfidentified), 2016 255

7.4 Mean Racial Resentment, Ethnocentrism, and Modern Sexism Scores, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Selfidentified), 2016 256

8.1 Percent Republican by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), Among Whites, 2012 263

8.2 Percent Reporting Experiences with the Following Types of Reverse Racial Discrimination, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), 2012 269

8.3A Percent Attitudes Toward Gay Marriage, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), 2012 277

8.3B Percent Attitudes Toward Abortion, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), 2012 278

8.4 Percent Reporting Experience with the Following Types of Reverse Racial Discrimination, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Self-identified), 2016 279

8.5A Percent Attitudes Toward Abortion, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Selfidentified), 2016 280

8.5B Percent Who Believe Abortion Should “Never” Be Legal and Percent Vote for GOP Presidential Nominee, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism in 2012 and Biblical Literalism and/or Self-identified in 2016), 2012–2016 282

8.6 Percent Republican by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Self-identified), Among Whites, 2016 283

9.1A Percent Responses to: “Do You Believe Mitt Romney Is a Christian?” by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), Among Whites, 2012 294

9.1B Percent Responses to: “Do You Happen to Know What Religion Barack Obama Belongs to?” Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), 2010 295

9.2 Percent Attitudes Toward Health Care Reform, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), 2012 304

9.3 Percent Responses to: “Do You Think It Is Important to Be Christian to Be Fully American?” Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), 2012 307

9.4 Percent Responses to: “The Earth Is Warming Because of Human Activity,” Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Selfidentified), 2016 312

9.5 Percent Responses to: “A Wall Should Be Built Along the Entire Border with Mexico,” Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Self-identified), 2016 313

9.6 Percent Attitudes Toward Banning Automatic Weapons, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Self-identified), 2016 314

9.7 Percent Attitudes Toward Sending Ground Troops to Fight ISIS in Iraq and Syria, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Selfidentified), 2016 315

9.8 Percent Responses to: “Do You Believe Donald Trump Is a Christian?” Among Whites, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Selfidentified), 2016 316

9.9 Percent Who Believe It Is Important to Be Christian to Be American and Percent Vote for Nominee, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism in 2012 and Biblical Literalism and/or Self-identified in 2016), 2012–2016 317

C.1A Percent Above the Racial Resentment, Christian Fundamentalism, and Modern Sexism Scales, All Combinations, Among Non-southern Whites, 2016 324

Figures

and Tables

C.1B Percent Above the Racial Resentment, Christian Fundamentalism, and Modern Sexism Scales, All Combinations, Among Southern Whites, 2016 325

C.2 Mean Party Identification of Respondents Who Score Above and Below the Midpoints of the Christian Fundamentalism, Modern Sexism, and Racial Resentment Scales, Among Whites, 2016 327

C.3 Mean LSS Scores, Among Whites, 2016 333

Tables

2.1 Percent “Concerned” or “Very Concerned” That Proposed Health Care Reforms May Lead to the Following Consequences, Among Whites, 2010 78

3.1 Percent Reporting That Providing the Following Is Not the Responsibility of the Federal Government, Among Whites, 2010–2012 101

3.2A Predicting Racial Resentment (Toward African Americans), Among Whites, 2012 110

3.2B Predicting Racial Resentment (Toward Latinos), Among Whites, 2012 111

4.1 Percent Reporting “Southern Women” Are “More,” “Less,” or “No Different” from American Women on the Following Traits, Among White Women Who Live in the Geographic South, 1992 139

4.2 Predicting Modern Sexism, Among White Women, 2012 151

5.1 Predicting Modern Sexism, Among White Men, 2012 175

6.1 Predicting Belief in a Future Female President, Among Whites, 2012 206

7.1 Percent Reporting Their Current Place of Worship “Strongly Discourages” or “Forbids” the Following Activities, Among Whites, 2007 230

7.2A Percent Agreement with the Following Statements Regarding Religious Beliefs, Among Whites, 2007, 2010 234

7.2B Percent Reporting to Have Had the Following Religious Experiences, Among Whites, 2007 235

7.3 Percent Participation in Religious or Faith-Based Activities, Among Whites, 2007, 2010 239

7.4 Percent Religious Identification, Among Whites, 2007, 2010, 2012 242

8.1 Percent Party Identification and Vote for Romney, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism), Among Whites, 2012 273

8.2 Percent Party Identification and Vote for Trump, by Fundamentalism (Biblical Literalism and/or Selfidentified), Among Whites, 2016 284

9.1 Percent Responses to the Following Secular Statements/Questions, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism, 2007, 2010 302

9.2 Percent Responses to the Following Foreign Policy/ Nationalism Statements/Questions, Among Whites, by Fundamentalism, 2007, 2010 310

C.1 Percent (with Running Totals) Above, At, and Below the Midpoint of the Modern Sexism, Racial Resentment, and Christian Fundamentalism Scales, Among Whites, 2016 332

C.2 Predicting General Election Vote for Trump, Among Whites, 2016 335

Notes on Data and Appendices

2010, 2012, and 2016 Blair Center Polls

The Diane D. Blair Center of Southern Politics and Society at the University of Arkansas ( https://blaircenter.uark.edu) conducted national surveys following the 2010 midterm elections as well as the 2012 and 2016 presidential elections. These surveys are the primary data sets used throughout the analysis. The 2010 Blair Center Poll was administered by Knowledge Networks (www. knowledgenetworks.com), while the 2012 and 2016 surveys were conducted by GfK (www.gfk.com), a market research firm that acquired Knowledge Networks in 2011. The GfK proprietary database includes a representative sample of adults living in the United States, including the growing number of individuals living in cell phone–only households. Participants in this database are recruited through address-based sampling. GfK’s probability-based recruiting methodology improves the degree to which samples accurately represent the US population and increases the participation of otherwise difficult-to-reach groups, such as individuals living in rural areas, the elderly, or minority groups. Importantly, participants who do not have access to the Internet are provided with a webenabled device and free Internet service in exchange for participation in the online panel.

The 2010 Blair Center Poll included a total sample of 3,406 individuals aged 18 years or older including 932 Latinos(as), 825 African Americans, and 1,649 nonHispanic white respondents. Similarly, the 2012 Blair Center Poll included a total sample of 3,606 participants including 1,110 Latinos(as), 843 African Americans, and 1,653 non-Hispanic white respondents. Finally, the 2016 Blair Center Poll included a total of 3,668 participants including 1,021 Latinos(as), 915 African Americans, and 1,732 non-Hispanic white respondents. Each survey included representative samples of respondents living in the geographic South, defined as the 11 states of the former Confederacy. The 2010 Blair Center Poll included 1,717

respondents from the Non-South and 1,689 respondents living in the South. The 2012 Blair Center Poll included 1,814 respondents living in the Non-South and 1,792 respondents living in the South. The 2016 Blair Center Poll included 1,840 participants living in the Non-South and 1,828 respondents living in the South. The margin of error for each survey is approximately +/−2.4. Throughout the analyses that follow, the data were weighted to reflect national demographics and improve the representativeness of the sample.

2007 and 2010 Baylor Religion Surveys

The Institute for Studies of Religion and the Department of Sociology at Baylor University conducted national surveys exploring religious attitudes, behaviors, and experiences. The 2007 Baylor Religion Survey was a 16-page self-administered mail questionnaire. Partnering with the Gallup Organization, researchers employed a mixed-mode sampling design, using both telephone and self-administered mailed surveys. Initially, the Gallup Organization conducted 1,000 random telephone interviews with a representative sample of adults living in the continental United States. Respondents were informed that the Gallup Organization was conducting an important study about Americans’ values and beliefs and were offered a $5.00 incentive to complete a self-administered questionnaire. In addition to the telephone calls, the Gallup Organization mailed 1,836 questionnaires to preselected individuals in Gallup’s national database. A total of 2,460 questionnaires were mailed to adults agreeing to participate in the survey. Ultimately, 1,648 respondents completed and returned the questionnaire. Similarly, the 2010 Baylor Religion Survey was conducted in collaboration with the Gallup Organization and was a self-administered 16-page questionnaire. As before, the Gallup Organization used a mixed-mode sampling design using both telephone calls and self-administered mailed surveys to recruit participants. Ultimately, 1,714 individuals completed and returned the questionnaire. For both the 2007 and the 2010 survey, weights are provided to improve the representativeness of the samples. Additional information about the data collection for the Baylor Religion Surveys may be found at https://www.baylor.edu/ BaylorReligionSurvey.

1992 and 1994 Southern Focus Polls

The Southern Focus Polls were conducted by the Odum Institute for Research in Social Science at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. These telephone surveys were conducted from 1992 through 2001. The target population for each survey included adults living in households with telephones across the

United States. The surveys also oversampled residents living in the 11 states of the former Confederacy. The Fall 1992 South survey included 795 respondents, the Fall 1994 South survey included 938 respondents, and the 1999 combined South and Non-South survey included 1,365 respondents. The data sets for the South and Non-South samples are generally saved separately and weights are provided to improve the representativeness of the samples. Additional information about the data collection for the Southern Focus Polls may be found at http://www. thearda.com/Archive/Sfocus.asp.

American National Election Studies

The American National Election Studies (ANES) are national surveys conducted immediately following each presidential and midterm election since 1948. The “ANES 1964 Time Series Study,” the “ANES Time Series Cumulative Data File (1948–2012),” and the “ANES 2016 Time Series Study” are utilized in this book. Additional information about the ANES surveys can be found at http://www. electionstudies.org/index.html.

Appendices

Appendix A presents the questions and responses for each of the variables used throughout the book. Appendix A also presents the coding of response categories, how scales were created, and the corresponding alpha levels of those scales. Appendix B presents the sample sizes for each figure and table, and appendix C presents the significance tests for each figure and table in the study. Throughout the analyses, unless explicitly stated otherwise, the data and findings are weighted to improve the representativeness of the survey samples. Throughout the analyses, difference of means tests were conducted when the dependent variable contained five or more response categories, chi-square tests were conducted when the dependent variable contained three or four response categories, and logistic regressions were conducted when the dependent variable contained two response categories. Since the direction of the relationships between the independent and dependent variables are predicted, the significance levels reported in appendix C, as well as in the models presented in Tables 3.2A, 3.2B, 4.2, 5.1, 6.1, and C.2, are based on one-tailed tests. Sources for each figure and table are included in both appendix B and appendix C.

Introduction

The Long Southern Strategy Explained

[T]he South did not become Republican so much as the Republican Party became southern.

1

Glenn Feldman

There is, indeed, an art of the deal. Sometimes only a prescient few can describe it. Such was the case in the wake of the 1948 southern white revolt from a Democratic Party that was beginning to question Jim Crow. This time, southern secession took the form of a third-party, segregationist bid for the White House, by which these aptly named Dixiecrats intended to prove just how indispensable they were to a Democratic Party victory. The rebellion would bring Democrats to their knees begging for reconciliation with their southern base, thus halting the party’s march toward racial equality in its tracks—or so the Dixiecrats hoped. However, the Democratic presidential nominee, incumbent Harry Truman, won without them. The Dixiecrats had gambled and lost. In the election postmortem that followed, two seemingly unrelated books appeared, both of which exposed that wager for what it was: a modern expression of an old tribal arrangement. Neither the prescient authors nor their disciplines could have been more different, and yet both books, each as relevant now as then, dissected an ailing South, stripping the region to its political bones and laying bare the mechanisms by which this Democratic stronghold would turn Republican red.

In her part memoir, part polemic Killers of the Dream, Lillian Smith, a southern, white, privileged intellectual, describes—as only a former insiderturned-outsider can—the politics of fear that was paralyzing the region at midcentury. At the base of that fear was what Smith calls the “grand bargain” of white supremacy, buttressed by paternalism and evangelicalism, whereby the southern white masses relinquished political power to the few in exchange for maintaining their social status as better than the black man. It was a bargain that required no paperwork or signatures. This deal was silent, embedded so deeply in southern white culture that it functioned as a political institution in and of itself, checking