The Last Great War of Antiquity

JAMES HOWARD- JOHNSTON

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

© James Howard-Johnston 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021932105

ISBN 978–0–19–883019–1

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198830191.001.0001

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

East-West conflict has been of perennial interest to historians, from the westernmost thrust of Persian power in the fifth century bc , when Xerxes attempted to conquer Greece, to the Cold War and the current rivalry between the old Western and the rising Eastern great power. All but one of the episodes of open warfare have had their historians, operating in the manner of Herodotus, but normally without his omnivorous curiosity. Politics being the prime subject matter of history in the classical period and violent action by discrete political entities its most intense manifestation, contemporary and near-contemporary historians gave plenty of space in their works to the many wars fought by Romans against the loose-knit Parthian empire and its more militarized Sasanian successor. The roll call of historians runs from Tacitus in the heyday of the Principate and Ammianus Marcellinus in the fourth century to Procopius and his three successors (Agathias, Menander Protector, and Theophylact Simocatta), who, between them, covered the four wars fought in the sixth century. Then, after a gap which this book is designed to fill, came the earliest Islamic historians, who, from the eighth century, pieced together narratives out of antecedent material about the Arab conquests, beginning with a victory over Roman forces not far from Gaza in 634. Their successors and their Christian counterparts covered the confrontations of Islam with Byzantium and Latin Christendom and the outward drive of the Ottomans.

The gap extends from 602 to 630. The grisly end of the Emperor Maurice and five of his six sons in November 602, after a military coup mounted by the Balkan field army and its new commander Phocas, provided the Sasanian king Khusro II with the pretext he needed to go to war to reassert the traditional parity of Persians with Romans. For Maurice was Khusro’s benefactor, having restored him to the Sasanian throne, but he had demanded large, damaging territorial concessions. The war broke out in spring 603 and was only brought to an end two years after the overthrow and execution of Khusro, when a durable peace was negotiated by his daughter Boran with Phocas’ nemesis and successor Heraclius in summer 630.

There is evidence about the war, but it is fragmentary and scattered across different types of source in different languages. It is a painstaking and timeconsuming process to extract, vet, and piece together the bits of information into some sort of coherent story. That may partly explain why there is no full, solidly founded critical history of the last war between the two established great powers of western Eurasia at the end of antiquity. Learned articles have been written on

individual episodes and on ideological aspects of the conflict. Many widerranging works, from Gibbon’s Decline and Fall to that recent worldwide sensation, Peter Frankopan’s Silk Roads, include outline accounts of the fighting, but they view it primarily as a precursor to the rise of Islam. Only two connected accounts of the whole war have been published, neither of which is grounded in comprehensive critical analysis of the primary material. One, the first volume of Andreas Stratos’s Byzantium in the Seventh Century, simply recycles what is chronicled by the sources, while the other, Walter Kaegi’s Heraclius Emperor of Byzantium, covers the fighting but is primarily concerned with the feats of one important participant.

A great deal of time has been consumed in research for this book. A prophecy of my wife’s, that it would take as long to write as the events took to unfold, has, I fear, come true. Serious work began in autumn 1990, when I started a year’s sabbatical leave. I am topping and tailing the eleven chapters, none very skimpy, into which it is divided, nearly twenty-seven years later and deep into defunctitude (aka retirement from university teaching, dubbed The Twilight of the Scholar by the young graduate students who enliven my existence). It is, I must confess, even worse than that. For the original inception of the project dates back to the early 1980s and took the form of a skeleton chronology handed out to undergraduate takers of an optional course in sixth- and seventh-century Middle Eastern history at Oxford. So what faces the reader is the product of nearly forty years’ work at the coal face of knowledge. That (as well as convenience) explains the old-fashioned terminology (Monophysite and Nestorian) used for non-Chalcedonian confessions (Miaphysite and Church of the East are now preferred). There were, I am glad to say, some by-products—learned papers delivered at conferences (cited in the bibliography) and a book, Witnesses to a World Crisis, which laid down the historiographical foundations. The structure which rises from those foundations has acquired considerable bulk, despite unrelenting effort to keep footnotes short and to limit references to primary sources and a necessary minimum of secondary works. I hope that the bulk will not be too off-putting.

I have benefited from scholarly company of all sorts over these forty years, above all from my undergraduate pupils with whom I discussed the last great war of antiquity in tutorials from the 1980s to 2009. They have been replaced since 2009 by a small number of young scholars with whom I have been meeting weekly in term to read texts in Ethiopic, Arabic, and Syriac. I am immensely grateful to Phil Booth, Marek Jankowiak, Ed Zychovicz-Coghill (a fine Arabist whom I cannot help but call Professor), and Simon Ford, not merely for helping me to plug shameful gaps in linguistic competence but also for innumerable discussions of historical issues. There are many, many other debts—to Faculty and College colleagues, to the graduate students with whom I like to hobnob in these declining days, to participants in several conferences on Sasanian history and archaeology held since the 1990s, to the conference on the reign of the

Emperor Heraclius organized by Gerrit Reinink and Bernard Stolte at Gröningen in 2001, to the Seventh-Century Syrian Numismatic Round Table, which meets at intervals of two to three years, and to travelling companions on journeys to Iran, Tunisia, Armenia, and Algeria over the last two decades (for the ideas and banter exchanged).

Although it may be invidious to single them out and there is always the danger that someone who should be mentioned may be omitted, let me thank in particular the following for their contributions of information and ideas: (1) on the Sasanians, Richard Payne, the late Zeev Rubin, and Josef Wiesehöfer: (2) on preIslamic Arabia, Michael Macdonald; (3) on numismatics, Tony Goodwin, Rika Gyselen, Cécile Morrisson, and Susan Tyler-Smith; (4) on archaeology, the late Judith Mackenzie, Jodi Magness, the late Boris Marshak, Eberhard Sauer, St.John Simpson, and Alan Walmsley; and (5) on texts, Michael Jackson Bonner, Tim Greenwood, David Gyllenhaal, the late Cyril Mango, and Mary Whitby. Finally there are three scholars to whom I owe a particularly large debt: Phil Booth, with whom I have analysed the text of John of Nikiu and who has read and helped to improve several chapters; Marek Jankowiak, first leader of our Arabic reading group, with whom I have been wrestling over certain historical cruxes since we first met ten years ago; and Constantin Zuckerman, Marek’s former supervisor, whom I regard as a peerless scholar of this period and a formidable antagonist when we disagree (as we do from time to time).

In addition, I am most grateful to the Oxford University Committee for Byzantine Studies for allowing me to keep an office in the Ioannou Centre for Classical and Byzantine Studies, for all these years of defunctitude.

JH-J

Temple House, Temple End, Harbury

November 2017

Postscript. Three and a half years have passed by since I wrote about the magnificent deformation of history in Corneille’s Héraclius at the end of this book. Scholars of Late Antiquity and Byzantium have been as active as ever in adding to knowledge and understanding. I have cited a few recent publications of particular importance, none more so than T.B. Mitford, East of Asia Minor: Rome’s Hidden Frontier, 2 vols. (Oxford, 2018), a gripping exploration of the Euphrates limes. Otherwise the text is unchanged. Finally, I am indebted to Callan Meynell for adding that vital component of any work of history, the index.

Brighton

February 2021

5.

6.

8.

9.

10.

9.4

List of Abbreviations

Periodicals and Series

AMI Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran

An. Boll. Analecta Bollandiana

AT Antiquité tardive

BAR British Archaeological Reports

BASOR Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research

BMGS Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies

BSOAS Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies

Byz. Byzantion

BZ Byzantinische Zeitschrift

CAH Cambridge Ancient History

CFHB Corpus Fontium Historiae Byzantinae

CRAI Comptes rendus de l’Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres

CSCO Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium

CSHB Corpus Scriptorum Historiae Byzantinae

DOP Dumbarton Oaks Papers

EHR English Historical Review

EIr Encyclopaedia Iranica

GRBS Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies

Ist.Mitt. Istanbuler Mitteilungen

JA Journal asiatique

JHS Journal of Hellenic Studies

JÖB Jahrbuch der Österreichischen Byzantinistik

JRA Journal of Roman Archaeology

JRAS Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society

JRS Journal of Roman Studies

JTS Journal of Theological Studies

MGH Monumenta Germanicae Historiae

NC Numismatic Chronicle

ODB Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, 3 vols. (New York, 1991)

PG Patrologia Graeca

PL Patrologia Latina

PO Patrologia Orientalis

REB Revue des études byzantines

RN Revue numismatique

SNS Sylloge Nummorum Sasanidarum

TIB Tabula Imperii Byzantini

TM Travaux et mémoires

TTH Translated Texts for Historians

VV Vizantiskij Vremmenik

Agap.

Primary sources

A. A. Vasiliev, ed. and trans., Kitab al-’Unvan, histoire universelle écrite par Agapius (Mahboub) de Menbidj, PO 7.4 and 8.3

Bal. al-Baladhuri, Kitab futuh al-buldan, ed. M.J. de Goeje, Liber expugnationis regionum (Leiden, 1866), trans. P. K. Hitti, The Origins of the Islamic State (New York, 1916) and F.C. Murgotten, The Origins of the Islamic State, Part II (New York, 1924)

Chron.1234

Chron.724

Chron.Pasch.

Geo.Pis.

HNov

H.Patr.Alex.

JA (John of Antioch)

JN (John of Nikiu)

Khuz.Chron.

Chronicon ad annum Christi 1234 pertinens, ed. J. B. Chabot, CSCO, Scriptores Syri, 3.ser., 14 (Paris, 1920), partial trans. A. Palmer, The Seventh Century in the West-Syrian Chronicles, TTH 15 (Liverpool, 1993), 111–221

Chronicon miscellaneum ad annum Domini 724 pertinens, ed. E. W. Brooks, CSCO, Scriptores Syri 3, Chronica Minora II (Louvain, 1960), 77–154, partial trans. Palmer, Seventh Century, 13–23

Chronicon Paschale, ed. L. Dindorf, CSHB (Bonn, 1832), partial trans. M. and M. Whitby, Chronicon Paschale 284-628 ad, TTH 7 (Liverpool, 1989)

Georgius Pisides: A. Pertusi, ed. and trans., Giorgio di Pisidia poemi: I panegirici epici (Ettal, 1959); L. Tartaglia, ed. and trans., Carmi di Giorgio di Pisidia (Turin, 1998)

J. Konidaris, ed. and trans., Die Novellen des Kaisers Herakleios, Fontes Minores 5.3 (Frankfurt, 1982)

History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria (St. Mark to Benjamin I), ed. and trans. B. Evetts, PO 1.2 and 4, 5.1, 10.5

Ioannes Antiochenus: U. Roberto, ed. and trans., Ioannis Antiocheni fragmenta ex historia chronica, Berlin-Brandenburgische Ak. Wiss., Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur 154 (Berlin, 2005)

H. Zotenberg, ed. and trans., Chronique de Jean, évêque de Nikiou (Paris, 1883)

(Khuzistan Chronicle) Chronicon anonymum, ed. I. Guidi, CSCO, Scriptores Syri 1, Chronica Minora I (Paris, 1903), 15–39, trans. T. Nöldeke, ‘Die von Guidi herausgegebene syrische Chronik übersetzt und commentiert’, Sitzungsberichte der kais. Ak. Wiss., Phil.-hist. Cl., 128 (Vienna, 1893), partial trans. Greatrex and Lieu, Roman Eastern Frontier, 229–37

MD Movses Daskhurants‘i (or Kałankatuats‘i), ed. V. Arak‘eljan, Movses Kałankatuats‘i: Patmut‘iwn Ałuanits‘ (Erevan, 1983), trans. C. J. F. Dowsett,

List of a bbreviations xiii

Moses Dasxuranc‘i’s History of the Caucasian Albanians (London, 1961)

Mich.Syr. (Michael the Syrian) J. B. Chabot, ed. and trans., Chronique de Michel le Syrien, Patriarche Jacobite d’Antioche (1166–1199), 5 vols. (Paris, 1899–1924)

Mir.Dem. (Miracula S. Demetrii) P. Lemerle, Les Plus Anciens Recueils des miracles de saint Démétrius, I Le Texte (Paris, 1979), II Commentaire (Paris, 1981)

Nic. Nicephorus, Breviarium, ed. and trans. C. Mango, Nikephoros Patriarch of Constantinople, Short History, CFHB 13 (Washington DC, 1990)

Paul D (Paul the Deacon)

ps.S (ps.Sebeos)

Seert Chron.

Pauli historia Langobardorum, ed. L. Bethmann and G. Waitz (Hanover, 1878), trans. W. D Foulke, Paul the Deacon, History of the Lombards (Philadelphia, PA, 1907), trans. F. Bougard, Paul Diacre, Histoire des Lombards (Turnhout, 1994)

Patmut‘iwn Sebeosi, ed. G. V. Abgaryan (Erevan, 1979), trans. R. W. Thomson in R. W. Thomson and J. Howard-Johnston, The Armenian History Attributed to Sebeos, TTH 31, 2 vols. (Liverpool, 1999), I Translation and Notes, II Historical Commentary

Seert Chronicle: ed. A. Scher, trans. A. Scher, R. Griveau, et al., Histoire nestorienne (Chronique de Séert), PO 4.3, 5.2, 7.2, 13.4

Sim. Theophylactus Simocatta, Historiae, ed. C. de Boor, rev. P. Wirth (Stuttgart, 1972), trans. Michael and Mary Whitby, The History of Theophylact Simocatta (Oxford, 1986)

Strategicon Mauricius, Strategicon, ed. G. T. Dennis and trans. (German) E. Gamillscheg, CFHB 17 (Vienna, 1981), trans. (English) G. T. Dennis, Maurice’s Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy (Philadelphia, PA, 1984)

TA T‘ovma Artsruni Patmut‘iwn Tann Artsruneats‘, ed. K. Patkanean (St Petersburg, 1887), 2.3 (89.20–1), trans. R. W. Thomson, Thomas Artsruni: History of the House of the Artsrunik‘ (Detroit, MI, 1985)

Tab. (al-Tabari)

ed. M. J. de Goeje et al., Annales quos scripsit Abu Djafar Mohammed ibn Djarir at-Tabari, 15 vols. (Leiden, 1879–1901), partial trans. C. E. Bosworth, The Sasanids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen: The History of al-Tabari V (pp. 813–1072), K. Y. Blankinship, The Challenge to the Empires, H of Tab. XI (pp. 2016–212), and Y. Friedmann, The Battle of al-Qadisiyyah and the Conquest of Syria and Palestine, H of Tab. XII (pp. 2212–418) (Albany, NY, 1999, 1993, 1992)

Theod.Sync., Hom. I

Theod.Sync., Hom. II

Theodorus Syncellus, Homily I, ed. L. Sternbach, Analecta Avarica, Rozprawy Akademii Umiejętności, Wydział Filologiczny, ser.2, 15 (Kraków, 1900), 298–320

Theodorus Syncellus, Homily II, ed. C Loparev, ‘Staroe svidetelstvo o polozhenii rizy Bogorodnitsy vo Vlakherniakh . . . ’, VV 2 (1895), 581–628, at 592–612, trans. Averil Cameron, ‘The Virgin’s Robe: An Episode in the History of Early Seventh-Century Constantinople’, Byz. 49 (1979), 42–56, repr. in Cameron, Continuity and Change in Sixth-Century Byzantium (London, 1981), no. XVII

Theoph. Theophanes, Chronographia, ed. C. de Boor, 2 vols. (Leipzig, 1883–5), trans. C. Mango and R. Scott, The Chronicle of Theophanes Confessor: Byzantine and Near Eastern History ad 284–813 (Oxford, 1997)

V.Anast. (Vita S. Anastasii) Vita S. Anastasii, ed. and trans. B. Flusin, Saint Anastase le Perse et l’histoire de la Palestine au début du VIIe siècle, I Les Textes (Paris, 1992)

V.Georg. (Vita S. Georgii) ed. C. Houze, ‘Vita S. Georgii Chozebitae . . . ’, An. Boll. 7 (1888), 97–144, 336–70

V.Ioannis (epit.) ed. E. Lappa-Zizicas, ‘Un Épitomé de la Vie de S. Jean l’Aumônier par Jean et Sophronios’, An.Boll. 88 (1970), 265–78

V.Theod. (Vita S. Theodori) A.-J. Festugière, ed. and trans., Vie de Théodore de Sykéôn, 2 vols (Brussels, 1970)

List of Maps

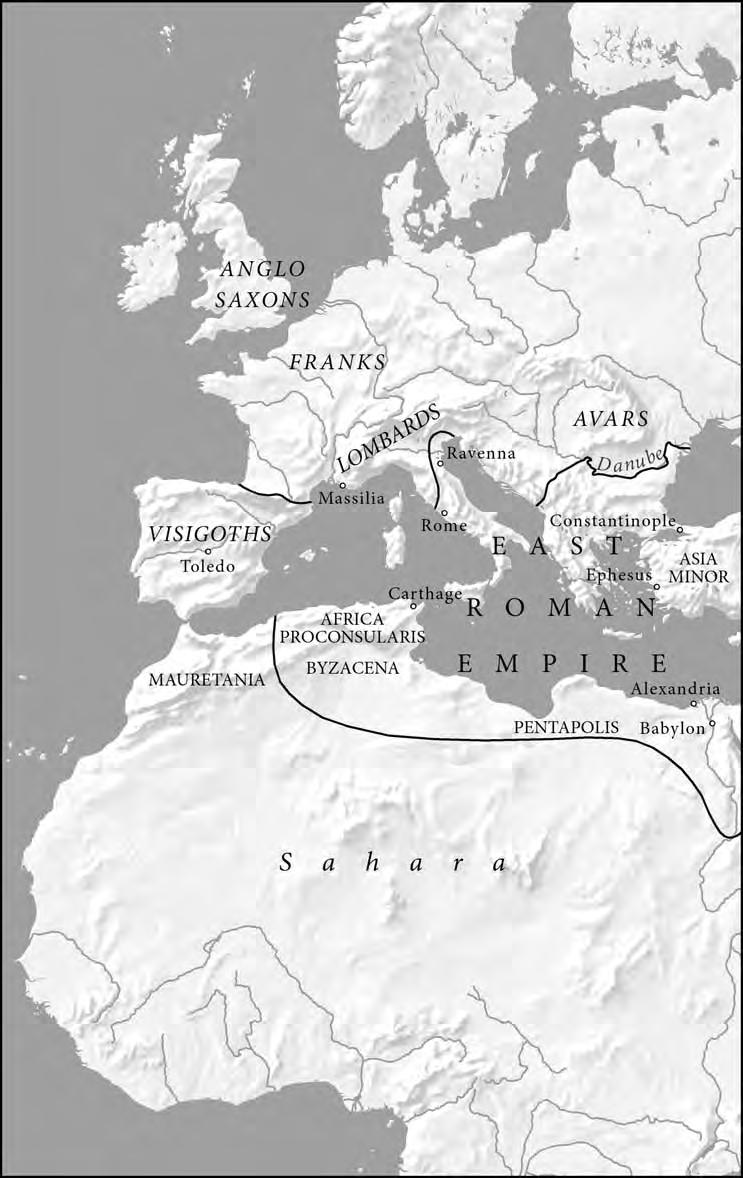

1. Western Eurasia xx

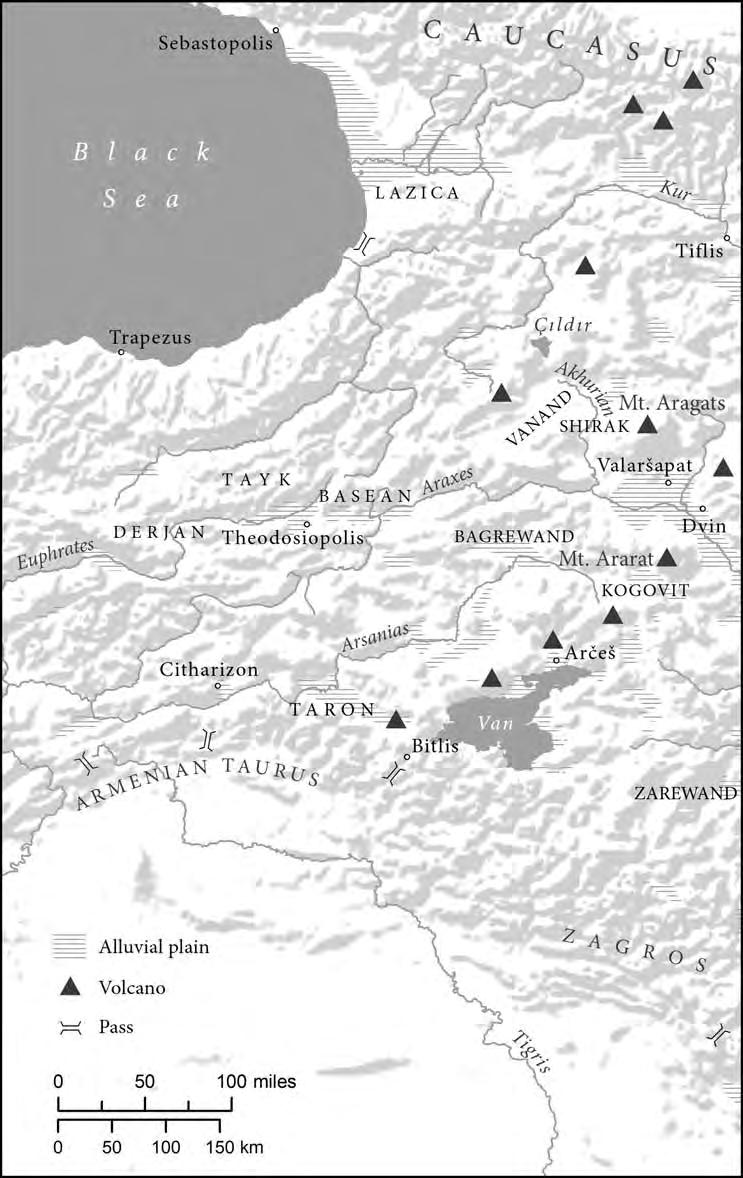

2. Armenia and neighbouring lands xxii

3. Fertile Crescent xxiv

4. Sasanian empire xxvi

5. Egypt xxvii

6. Alexandria and its hinterland xxviii

7. Constantinople and environs xxix

8. Asia Minor xxx

9. Balkans xxxii

List of Figures

1. Constantinople (a) land walls (b) gate

2. Royal palace at Ctesiphon (Taq-i Kisra): façade

3. Royal palace at Ctesiphon (Taq-i Kisra): side view

4. Taq-i Kisra: ground plan

5. Coins of Heraclius: silver hexagram (615–38)

6. Seal of Wistaxm, Ērān-spāhbed of the West (under Khusro I [531–79])

7. Coins of Khusro II: ceremonial dinar of year 33

8. Coins of Khusro II: ceremonial dinar of year 21

9. Taq-i Bustan: lake

10. Taq-i Bustan: grotto

11. Taq-i Bustan: investiture of Khusro II

12. Taq-i Bustan: Khusro’s fravashi

13. Taq-i Bustan: boar hunt

14. Taq-i Bustan: deer hunt

15. Bisutun: blank screen prepared for Khusro II monumental relief

16. Naqsh-i Rustam: general view

17. Naqsh-i Rustam: blank screen

18. Constantinople: St. Sophia

19. Takht-i Sulaiman: defences

20. Takht-i Sulaiman: lake

21. David Plates: David’s first audience with Saul

22. David Plates: David and Goliath

23. Mren, relief over north portal: Heraclius, dismounted, outside Jerusalem

24. Jerusalem: Golden Gate

25. Joshua Roll (folio VII): two spies report back to Joshua—the Israelites are repulsed from the city of Ai

26. Joshua Roll (folio X): Joshua is promised that Ai will fall; denuded of defenders, lured out by a feigned retreat, Ai is taken and fired (above right); the men of Ai are slaughtered in a pincer attack (below right)

27. Joshua Roll (folio XII): Joshua receives the submission of the Gibeonites

28. Joshua Roll (folio XIII): the Amorites are routed and their five kings take refuge in a cave

29. Jerusalem: Dome of the Rock

30. Coins of Heraclius: solidus (629–31)

31. Rostock, Klosterkirche ‘Zu den Heiligen Kreuz’, Nonnenaltar: thirteenth-century cycle of scenes from the Legenda Aurea: Khusro II captures the True Cross; Heraclius restores the True Cross

32. Battle of Nineveh, by Piero della Francesca

Table of Events

591 restoration of Khusro II

594/5–601/2 rebellion of Bistam

602 mutiny of Balkan field army, election of Phocas as leader, march on Constantinople, coronation of Phocas (23 November), and entry into the city (25 November) 602–3 winter: rebellion of Narses, commander of Roman forces in the south-east

603 Persian victory south of the Armenian Taurus, Persian reverse in Armenia

604 fall of Dara, victorious Persian campaign in Armenia

605 Persian victory in Bagrewand, and advance to the Araxes-Euphrates watershed

606 pause in Persian military operations

607 Persian victory in Armenia, dispatch of raiding forays west and south-west, capitulation of Theodosiopolis, siege of Cepha

608 victory of Shahen in Armenia

rebellion of Heraclius Exarch of North Africa fall of Cepha (on the eve of winter)

609 fall of Mardin, Persian occupation of Tur Abdin (spring) invasion of Egypt by Heraclian forces, entry into Alexandria (spring–summer)

capitulation of Edessa, Amida, Theodosiopolis (Resaena), and Constantia (summer)

Bonosus’ attack on Alexandria repulsed (23 November)

610 Persian crossing of the Euphrates and capture of Zenobia (7 August) arrival of rebel fleet at Constantinople (3 October) coronation of Heraclius (5 October) fall of Antioch (8 October), Apamea (15 October), Emesa (a few days later in October)

611 Shahen’s invasion of Asia Minor and occupation of Caesarea victory of Nicetas outside Emesa

612 Shahen’s breakout from Caesarea

613 Persian defeat of Heraclius near Antioch, and subsequent capture of Damascus

614 pogrom in Jerusalem, Persian siege, fall of the city (17 May)

615 Persian advance to Chalcedon diversionary campaign of Philippicus into Armenia

Roman Senate’s letter to Khusro Turkish invasion of Iran

616 victorious campaign of Smbat Bagratuni in the north-east occupation of Palestine

617 raiding expeditions of Shahrbaraz and Shahen into Asia Minor

619 fall of Alexandria (June)

620 Slav attack on Thessalonica

622 blockade of cities in or near the Pontic region by Persians Heraclius’ army exercises in Bithynia (spring), and victory over shadowing Persian army (summer)

thirty-three-day Avar-Slav siege of Thessalonica

emigration (hijra) of Muhammad and followers from Mecca to Medina

623 surprise Avar attack before scheduled summit meeting (5 June)

624 dispatch of Roman ambassador to Turks

HERACLIUS’ FIRST COUNTEROFFENSIVE

assembly of Roman expeditionary army at Caesarea (Cappadocia), march across Armenia, invasion of Atropatene, flight of Khusro from Ganzak (April–July)

destruction of fire-temple at Thebarmais, devastation of Media and west Atropatene (summer)

withdrawal north to winter near P‘artaw in Caucasian Albania

625 march south, victories over three pursuing Persian armies, devastation of eastern Atropatene, withdrawal north towards Caucasus arrival of Turkish embassy (autumn) departure of Laz and Abasgian contingents, march south-west to winter near Lake Van midwinter raid on Shahrbaraz’s headquarters

626 Heraclius’ withdrawal and Persian pursuit, through northern Syria and Cilicia (spring)

arrival of Shahrbaraz at Chalcedon (June) crossing of Long Wall by Avar vanguard (29 June) Avar siege of Constantinople (29 July–7 August) defeat of Shahen in northern Asia Minor (autumn)

Turkish attack across the Caucasus, exchange of diplomatic notes between the shad and Khusro

627 Turkish invasion in force across the Caucasus, fall of Derbend (guarding Caspian Gates) and P‘artaw (summer)

HERACLIUS’ SECOND COUNTEROFFENSIVE

Roman invasion of Lazica (summer) invasion of Iberia from east and west, summit meeting of Heraclius and the yabghu khagan outside Tiflis, joint Roman-Turkish siege of Tiflis (autumn)

Heraclius’ march across the Zagros range to the Great Zab river (16 October–1 December)

627 victory over scratch Persian force commanded by Rahzadh near Nineveh (Saturday 12 December), followed by victorious advance south flight of Khusro from palace at Dastagerd to Ctesiphon (23 December)

628 arrival of Roman army at Nahrawan canal (10 January) devastation of Shahrazur region (February)

628 overthrow of Khusro II (24 February)

629

coronation of Kavad Shiroe (25 February)

execution of Khusro II (28 February)

Turkish occupation of Albania, formal submission of Albania by delegation headed by Catholicos Viroy

Turkish victory over Arab force in Armenia

Persian evacuation of Alexandria (June)

summit meeting between Heraclius and Shahrbaraz (July)

crisis in central Asia and Turkish withdrawal

630 ceremonial restoration of True Cross in Jerusalem (21 March)

conclusion of peace between Persians and Romans

Muslim takeover of Mecca

632 death of Muhammad

Map 1 Western Eurasia

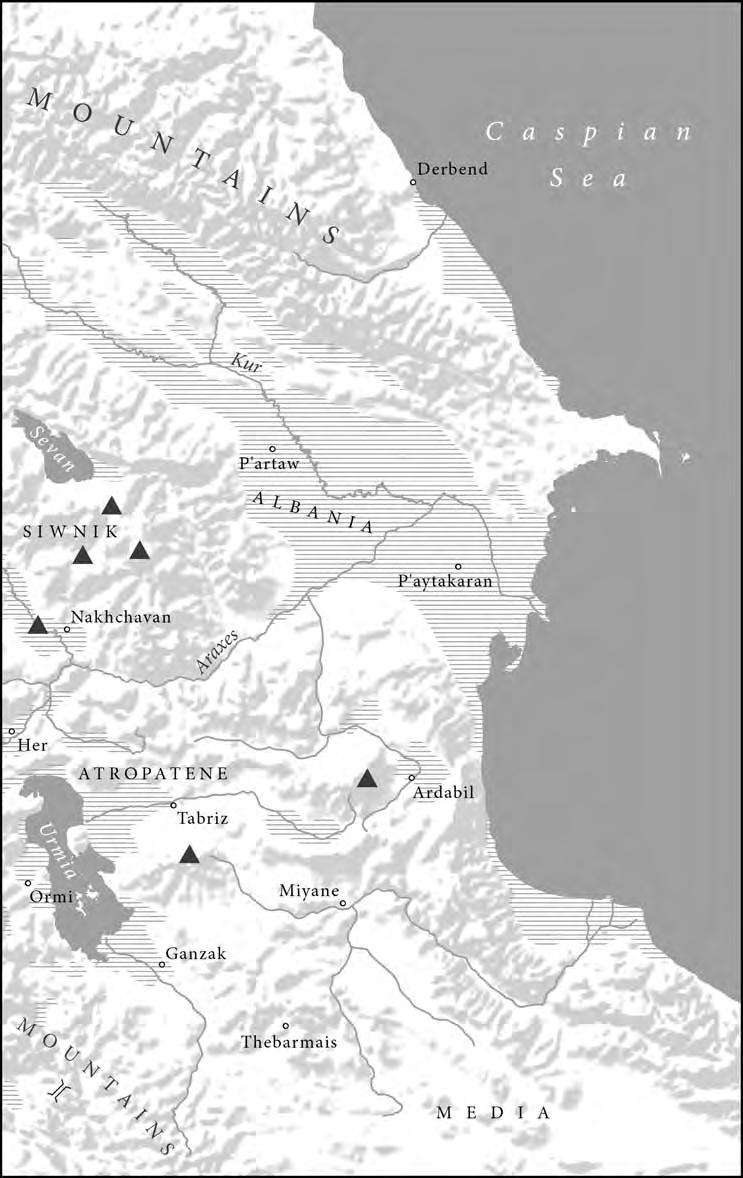

Map 2 Armenia and neighbouring lands

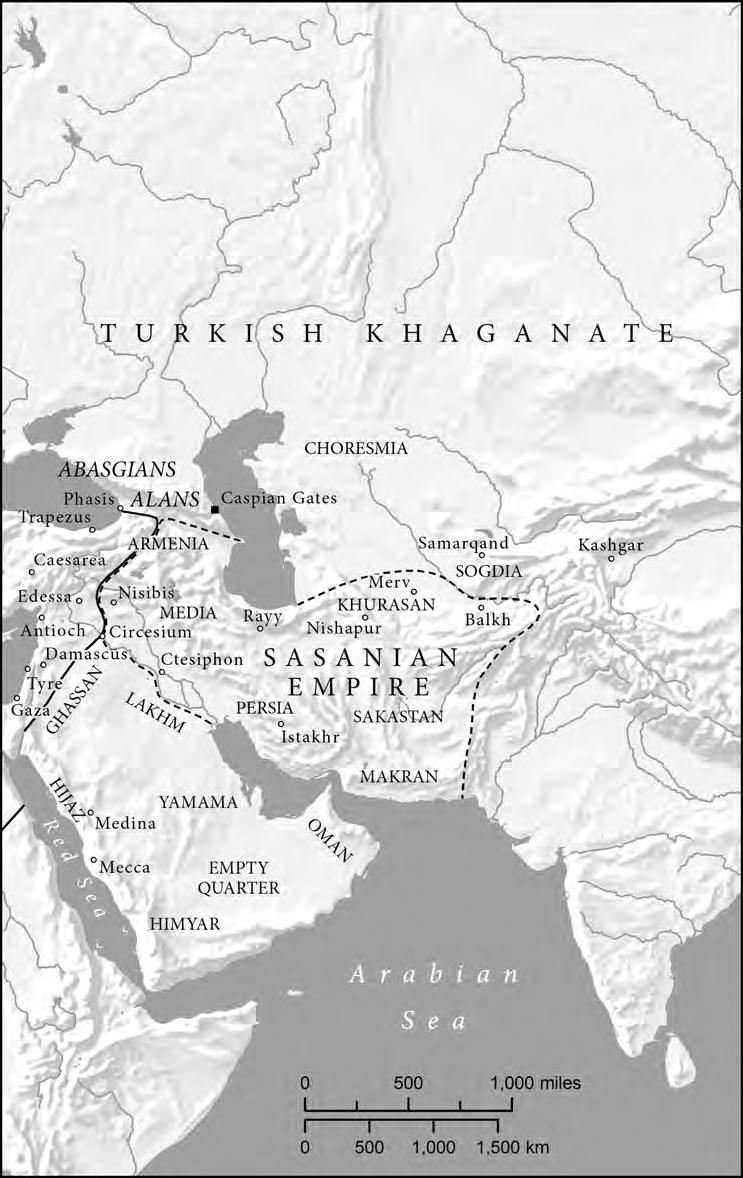

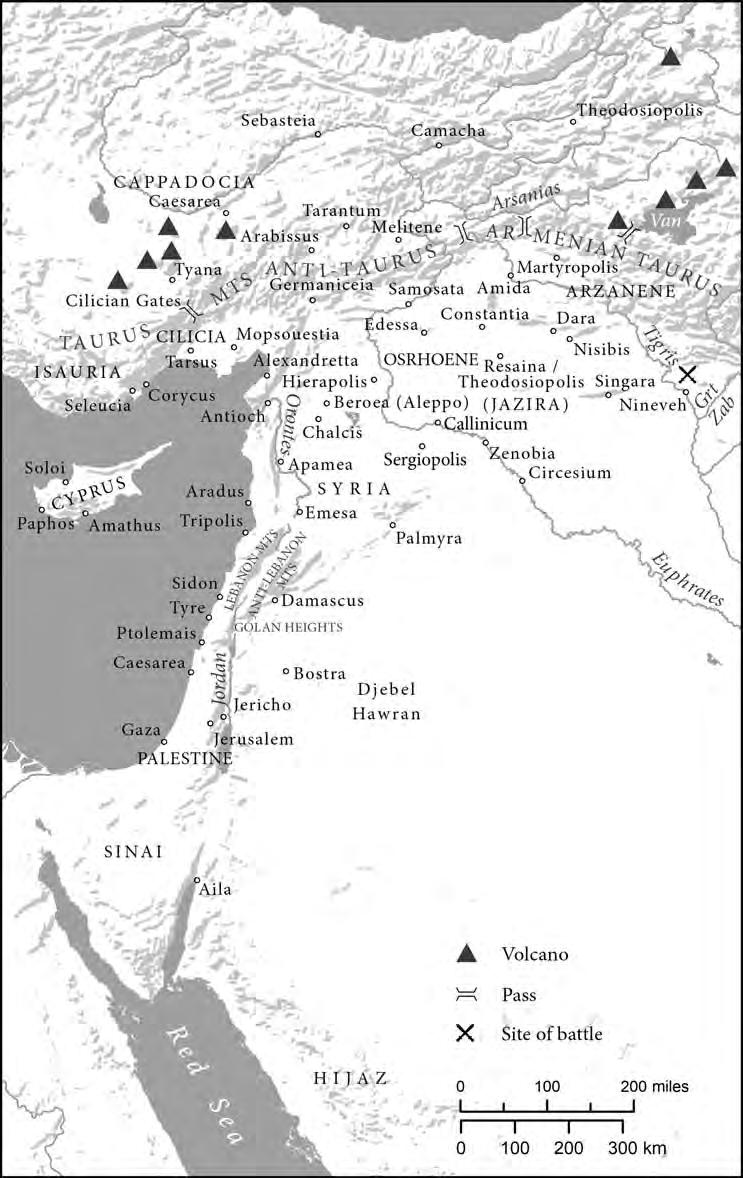

Map 3 Fertile Crescent